Bones are a central dynamic element in skeletal tissues that is continuously remodeled to maintain healthy structures in vertebrates. The strength and structural integrity of bone are tightly regulated by bone formation through osteoblasts and bone resorption through osteoclasts (Min et al., 2018). Postmenopausal osteoporosis reflects an imbalance in bone remodeling in which osteoclastic bone resorption exceeds osteoblastic bone formation due to estrogen deficiency (Eastell et al., 2016). Low bone mass and weakened microarchitecture due to osteoporosis increase a patient's vulnerability to fractures and cause debilitating bone pain in the elderly population (Sontag and Krege, 2010). In both developing and developed countries, the number of elderly people is increasing, and, consequently, osteoporosis is becoming a major public health problem (Eastell et al., 2016).

Osteoclasts are multinucleated giant cells derived from hematopoietic progenitors through a differentiation process in the presence of macrophage colony-stimulating factor and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL) (Wada et al., 2006). Binding of RANKL to its receptor RANK leads to the recruitment of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) to the cytoplasmic domain of RANK, which ultimately leads to activation of TRAF6 (Galibert et al., 1998; Darnay et al., 1999). Activation of TRAF6 then triggers multifarious downstream signaling pathways, including those of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and three mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), namely, c-jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and p38. Activation of these pathways up-regulates the expression of cFos and nuclear factor of the activated T cell c1 (NFATc1) (Boyle et al., 2003; Lee and Kim, 2003). NFATc1 is a key regulator of RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation, fusion, and activation (Zhao et al., 2010). Activations of the above signaling pathways directly regulate the expressions of osteoclastogenesis-related marker genes, such as tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9), and cathepsin K (Cath-K), which play important roles in degrading the bone matrix (Logar et al., 2007). Therefore, targeting the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways may be a more effective strategy to treat bone degenerative diseases than existing therapeutic treatments.

Current therapeutic methods for osteoporosis can be divided into two mechanistic classes: anti-resorptive agents and bone-forming agents. Anti-resorptives, including bisphosphonates (Alvarez et al., 2016), estrogens, hormone replacement therapy, and selective estrogen receptor modulators, can slow the progression of resorption by directly inhibiting osteoclast activity. Bone-forming (osteogenic) agents, such as parathyroid hormone, can stimulate new bone formation by effectively promoting osteoblastic activity (Brar et al., 2010). These therapies show some efficacy in humans for managing osteoporosis, but each approach also presents negative side effects, including increased risk of jaw necrosis, endometrial and breast cancer, hypercalcemia, and vaginal bleeding (Morley et al., 2001; Dannemann et al., 2007). Therefore, developing natural products or synthetic substances that can improve osteoporosis with few negative side effects is important.

As an economically and ecologically important marine species, the Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) is in great demand for human consumption (Kjesbu et al., 2006; Rise et al., 2015). However, many by-products of processing of this fish are abandoned, and the high-value utilization of the species has not been achieved. Considering the potential benefits of fish by-products, research on conversion of these products into profitable materials is both meaningful and desirable. Fish eggs, an important G. morhua by-product, act as energy storage for embryonic development because they contain abundant bioactive constituents, including phosphatidylcholine, polyunsaturated fatty acid, and glycoprotein (Olsen et al., 2014). Sialoglycoproteins, which are characterized by high sialic acid and carbohydrate contents, are found in both chicken and fish eggs. Sialoglycoproteins have been associated with embryogenesis, but little is known about their biological activities (Taguchi et al., 1994). Previous studies in our laboratory have demonstrated that sialoglycoproteins isolated from the eggs of Carassius auratus present antiosteoporotic properties that effectively regulate osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis (Xia et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016). Here, for the first time, we isolated sialoglycoproteins from the eggs of G. morhua (Gm-SGP) and explored their inhibitory effect on bone loss in the ovariectomized (OVX) rat model. To understand the mechanisms underlying this action, the MAPK and NF-κB pathways were further investigated.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 MaterialsEggs of G. morhua were purchased from Shandong Oriental Ocean Group Co., Ltd. (Yantai, China). Alendronate (ALN) was obtained from CSPC Ouyi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Shijiazhuang, China). ELISA assay kits for estradiol (E2), osteocalcin (OCN), deoxypyridinoline (DPD), Cath-K, MMP-9, osteoprotegerin (OPG), and RANKL were purchased from R & D Systems China Ltd., Co. (Shanghai, China). Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and TRAP were purchased from Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). Trizol reagent and Maxima SYBR Green qRT-PCR Master Mix were obtained from Invitrogen (CA, USA). RNase-free water, dNTPs, Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (MMLV), and random primers were obtained from TaKaRa Bio Inc. (Otsu, Shiga, Japan). The primers of OPG, RANKL, TRAF6, NF-κB, JNK, ERK, p38, c-Fos, NFATc1, and β-actin were synthesized by ShengGong Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Rabbit anti-rat OPG, RANKL, TRAF6, NF-κB p65, p-NF-κB p65, JNK, p-JNK, ERK, p-ERK, p38, p-p38, c-Fos, NFATc1, β-actin, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from CST (Boston, MA, USA).

2.2 Preparation of Gm-SGPMature eggs (500 g) were homogenized in 3 volumes (v/w) of 0.5 mol L-1 NaCl with a squeezer for 5 min and then centrifuged at 2100 × g for 5 min and the residue was removed. The supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of 90% phenol, and the resulting mixture was stirred overnight at 4℃. After centrifuged at 2100 × g for 10 min, the aqueous phase was decanted into dialysis bags with a sectional molecular weight of 3000 Da and dialyzed with tap water for 3 days and then with distilled water for 1 day to remove the phenol. The crude glycoprotein was purified by sequential anion-exchange chromatography on a QFF (2.6 mm × 50 cm). The eluent containing sialoglycoproteins was collected and lyophilized. Liquid chromatography was performed on an Agilent 1100 system (Palo Alto, CA, USA) with a TSK G4000PWXL column (TOSOH BIOSEP) by eluting with 0.2 mol L-1 NaCl. The result revealed the molecular weight of Gm-SGP was 7000 Da and the purity of the product was 87.46%. The hexose (65.86%) and protein (18.32%) contents of the extract were detected by the phenol-sulfuric acid and Lowry methods, respectively. Sialic acid content was determined by HPLC to be 15.7% after the derivation with OPD-HCl using N-acetylneuraminic acid as the standard (Anumula, 1995).

2.3 Animal ExperimentFemale Wistar rats (3 months old) were purchased from Vital River Laboratory Animal Center (Beijing, China; Licensed ID: SCXK2007-0001) and housed with free access to distilled water in 12 h:12 h light:dark conditions at 23℃ ± 1℃. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with internationally valid guidelines, and all experimental protocols were approved by the animal ethics committee (certificate no. SYXK20120014) according to the guidelines of the Standards for Laboratory Animals of China (GB 14922-94, GB 14923-94, and GB/T 14925-94).

The acclimatized animals underwent either bilateral laparotomy (SHAM, n = 8) or bilateral ovariectomy (OVX, n = 32). One month after bilateral OVX was performed, the OVX rats were randomly divided into four groups (n = 8 per group) as follows: OVX model control group (treated with physiological saline), ALN group (treated with alendronate sodium, 1 mg kg-1 body weight), 150Gm-SGP group (treated with Gm-SGP, 150 mg kg-1 body weight), and 450Gm-SGP group (treated with Gm-SGP, 450 mg kg-1 body weight). The SHAM group was treated with physiological saline only. Physiological saline or the respective drugs were given by gavage once a day for 90 days (10 mL kg-1 body weight).

Body weight was recorded every 3 days during the experimental period. Three days before the animals were euthanized, urine was collected for 24 h into metabolic cages and stored at -80℃ for biochemical measurement after centrifugation. After the last drug administration, blood was collected for biochemical determination. The uterus was removed from each rat and weighed immediately. Left femurs were dissected, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and then wrapped in gauze saturated with physiological saline for bone mineral density (BMD), biomechanical quality, and µ-CT analyses. The remaining femurs and tibias were frozen at -80℃ for qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses.

2.4 Micro-Computerized Tomography AnalysisThe μ-CT analysis was conducted using a μ-CT80 scanner (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). Scanning was performed at 55 kV, 145 mA, and 500 ms integration time. Coronal images were collected at a resolution of 9 μm per pixel and reconstructed into 3D images for morphometric analysis. Quantification of trabecular morphometric indices was performed on a defined cancellous bone area which was located 1 mm below the growth plate at the distal end of the femur. Trabecular morphology was described by measuring bone volume fraction (bone volume/tissue volume, BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), connectivity density (Conn.D), and structural model index (SMI).

2.5 Bone Mineral Density and Bone Biomechanical Property AnalysesThe BMD of left femurs was measured using a dualenergy X-ray absorptiometer (DEXA; Lunar Prodigy Advance, GE Healthcare, USA) equipped with a specialized software program (Lunar Software Version 1.46). BMD was calculated using the bone mineral content of the measured area. Bone biomechanical parameters were measured using a YLS-16A bone strength tester (Yiyan, Jinan, China).

2.6 Serum and Urine Biochemistry AssayConcentrations of serum E2, ALP, TRAP, MMP-9, CathK, OPG, RANKL, and urine DPD were determined through testing with the corresponding kits.

2.7 Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction AnalysisThe expression of genes regulating osteoclastogenesis, such as OPG, RANKL, TRAF6, NF-κB, JNK, ERK, p38, c-Fos, and NFATc1, were examined by quantitative realtime polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) as previously described (Xia et al., 2015a). Total RNA was isolated from tibias using Trizol reagent, and its concentration was detected by a spectrophotometer. One microgram (1 mg) of RNA was converted into cDNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase, and qRT-PCR was conducted using the iCycler iQ5 system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). A reaction volume of approximately 25 μL consisting of 12.5 μL of Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix, 10 μmol L-1 primers (0.3 μL each of the forward and reverse primers), 5.9 μL of nuclease-free water, and 6 μL of template was used for the qRT-PCR assay. The thermal procedure included an initial denaturation cycle at 95℃ for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles including denaturation at 95℃ for 15 s, annealing at 60℃ for 20 s, and, an extension at 72℃ for 30 s. Data normalization was conducted using β-actin as the endogenous reference. Gene expression levels were analyzed through relative quantification using the standard curve method. Table 1 describes the sequences of the primers.

|

|

Table 1 Sequence of the primers used in the quantitative real-time PCR |

Femur tissues (0.1 g) were lysed using lysis buffer, centrifuged, separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4℃ and blocked first with primary antibodies against OPG, RANKL, TRAF6, NF-κB p65, p-NF-κB p65, JNK, p-JNK, ERK, p-ERK, p38, p-p38, c-Fos, and NFATc1 and then with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Membranes were visualized with an ECL detection kit (Applygen Technologies Inc., Beijing, China). The results were analyzed by ImageJ software, and data were standardized using β-actin as the control.

2.9 Statistical AnalysisData are presented as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). Data were analyzed statistically by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by LSD tests. Probability values were considered significant when P < 0.05.

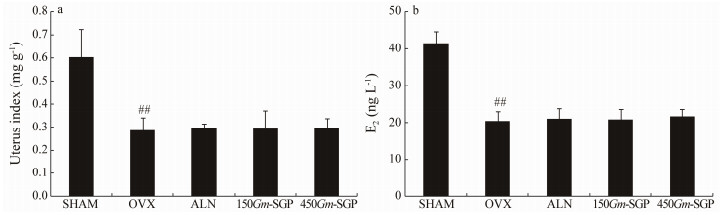

3 Results 3.1 Gm-SGP Did not Elicit Estrogenic EffectsAs shown in Fig. 1, rats in the OVX group showed significant reductions in atrophy of the uterine tissue and E2 levels when compared with rats in the SHAM group (P < 0.01), thereby indicating the success of the surgical procedure. No statistical differences were observed between the OVX and Gm-SGP groups, which means Gm-SGP does not elicit any uterotrophic or estrogenic effect.

|

Fig. 1 Effects of Gm-SGP on the uterine index and estrogen level of OVX-induced osteoporotic model rats. The rats were treated for 90 days, after which uteruses were removed and then weighed immediately to calculate the uterine index (a). Blood was collected to measure estrogen levels (b). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8 per group). Multiple comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA. ## P < 0.01 vs. the SHAM group. |

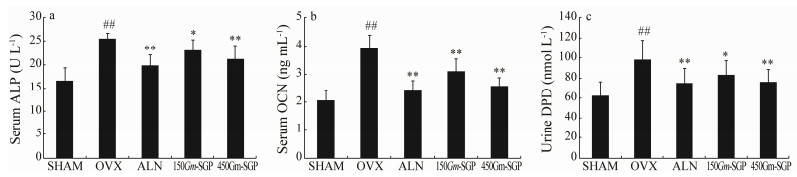

Biomarkers of bone formation and bone resorption provide insights into the systemic skeletal response to Gm-SGP. As shown in Fig. 2, OVX rats revealed increased serum ALP and OCN levels, as well as urine DPD excretion (P < 0.01), when compared with those in the SHAM group. This change was moderated by treatment with Gm-SGP. Serum ALP and OCN and urine DPD levels were significantly down-regulated in 450Gm-SGP rats by 17.14%, 34.52%, and 22.45%, respectively, compared with those in the OVX-alone group.

|

Fig. 2 Effects of Gm-SGP on systemic biomarkers of bone metabolism in OVX-induced osteoporotic model rats. Blood was collected to detect serum indices (a, b), and urine was collected 3 days before euthanization of the rats to detect the urine index (c). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8 per group). Multiple comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA. ## P < 0.01 vs. the SHAM group; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 vs. the OVX group. |

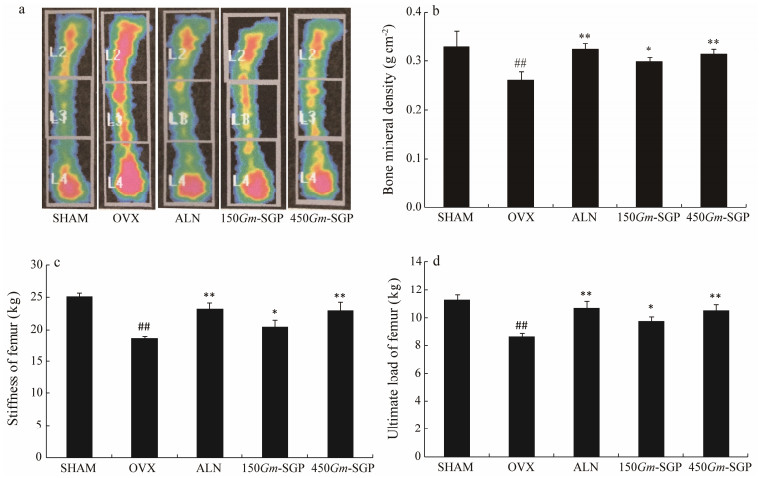

Measurement of BMD by DEXA is considered the gold standard assessment of osteoporosis risk (Richards et al., 2008). As shown in Fig. 3, quantitative analysis indicated that OVX causes a significant reduction in BMD by 20.91% compared with that in the SHAM group. Treatment with low and high doses of Gm-SGP significantly rescued the decrease in BMD by 14.18% and 19.92%, respectively, compared with that of the OVX-alone group.

|

Fig. 3 Effects of Gm-SGP on left femur bone mineral density (BMD), stiffness, and ultimate load in OVX-induced osteoporotic model rats. Femurs were dissected and filled with physiological saline for the measurements of BMD (a, b) and biomechanical quality (c, d). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8 per group). Multiple comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA. ## P < 0.01 vs. the SHAM group; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 vs. the OVX group. |

Bone strength, the measure of bone quality, is determined by multiple factors, including intrinsic properties of bone tissues (Goel et al., 2015). As shown in Fig. 3, both the stiffness and ultimate load of femurs were obviously weakened in OVX rats (P < 0.01). Gm-SGP prevented decreases in these parameters, and a dose of 450 mg kg-1 bw Gm-SGP increased these two parameters by 22.11% and 23.45%, respectively (P < 0.01). These results suggest that Gm-SGP significantly promotes bone strength in osteoporotic rats.

3.5 Gm-SGP Prevented OVX-Induced OsteolysisTo investigate the effect of Gm-SGP on bone loss in OVX rats, a coronal image of the distal femur was taken by μ-CT. As shown in Fig. 4, deterioration of the microarchitecture and significant negative changes in all trabecular microstructural parameters were induced by OVX. Treatment with Gm-SGP ameliorated these adverse changes. Compared with OVX group, Gm-SGP (450 mg kg-1 bw) increased BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, and Conn.D by 118.18%, 12.5%, 79.75%, and 216.24%, respectively (P < 0.01). This treatment also reduced Tb.Sp and SMI by 47.62% and 42.11%, respectively, compared with those in the OVXalone group (P < 0.01).

|

Fig. 4 Effects of Gm-SGP on femur bone loss in OVX-induced osteoporotic model rats. Three-dimensional images were taken by micro-computerized tomography of the distal left femur. Trabecular microstructural properties, including BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, Conn.D, Tb.Sp, and SMI are shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8 per group). Multiple comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA. ## P < 0.01 vs. the SHAM group; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 vs. the OVX group. |

To ascertain whether Gm-SGP affects bone resorption activity through inhibition of osteoclast differentiation, we assessed the serum expression of osteoclast-specific markers. TRAP is a well-known enzyme that is a histochemical marker of osteoclasts. During osteoclastogenesis, the synthesis and secretion of adhesion molecules and matrix-degrading enzymes, such as Cath-K and MMP-9, are closely related to bone resorption function. Fig. 5 shows that, consistent with previous reports, OVX led to significant up-regulation of TRAP, MMP-9, and Cath-K expressions in serum. Gm-SGP significantly reduced the serum levels of these enzymes, and 450 mg kg-1 bw Gm-SGP decreased the serum levels of these markers by 19.76% (TRAP), 17.85% (MMP-9), and 15.32% (Cath-K) compared with those of the OVX group (P < 0.01). These results suggest that Gm-SGP suppresses the bone resorption function of osteoclasts by inhibiting the production of matrix-degrading enzymes.

|

Fig. 5 Effects of Gm-SGP on serum osteoclastic markers in OVX-induced osteoporotic rats. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8 per group). Multiple comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA. ## P < 0.01 vs. the SHAM group; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 vs. the OVX group. |

The ratio of OPG/RANKL is the key element regulating osteoclastogenesis and osteoclast function. To gain insights into the molecular mechanisms by which Gm-SGP inhibits bone loss caused by OVX, the OPG/ RANKL ratio of the rats was assessed. As shown in Fig. 6, OVX distinctly lowered the OPG/RANKL ratio at the mRNA and secretion levels due to decreases in OPG and increases in RANKL. Gm-SGP alleviated the ratio of OPG/RANKL, and 450 mg kg-1 bw Gm-SGP up-regulated OPG/RANKL expression at the mRNA and secretion levels by 606.45% and 81.03% (P < 0.01), respectively.

|

Fig. 6 Effects of Gm-SGP on the expressions of OPG and RANKL in serum. (a) Serum OPG and RANKL contents and OPG/RANKL ratio. (b) mRNA expressions of OPG and RANKL and OPG/RANKL ratio. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8 per group). Multiple comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA. ## P < 0.01 vs. the SHAM group; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 vs. the OVX group. |

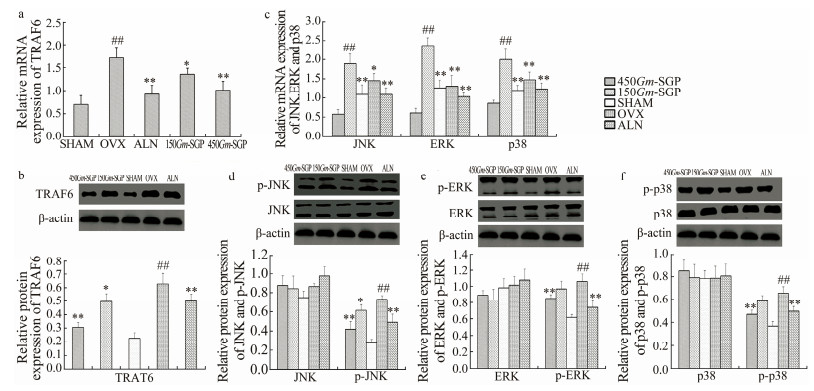

Binding of RANKL to RANK triggers recruitment of TRAF6, which activates downstream signaling molecules, such as MAPKs and NF-κB. Since the expression of RANKL was down-regulated by Gm-SGP, we examined changes in TRAF6. As shown in Figs. 7a and 7b, the mRNA and protein expression levels of TRAF6 obviously increased in the OVX group. Gm-SGP (450 mg kg-1 bw) markedly decreased TRAF6 expression by 40.72% (mRNA level) and 51.17% (protein level) compared with those of the OVX-alone group.

|

Fig. 7 Effects of Gm-SGP on the mRNA and protein expressions of TRAF6 and MAPKs in OVX-induced osteoporotic rats. (a) mRNA expression of TRAF6. (b) Protein expression of TRAF6. (c) mRNA expression of MAPKs. (d-f) Protein expression of MAPKs. Results were normalized by β-actin, and data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8 per group). Multiple comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA. # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 vs. the SHAM group; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 vs. the OVX group. |

JNK, ERK, and p38 are important signaling pathways mediated by TRAF6 that regulate osteoclast differentiation (Qiao et al., 2016; Cong et al., 2017). Thus, we tested whether Gm-SGP affects these pathways. As shown in Fig. 7c, OVX significantly enhanced, while Gm-SGP significantly decreased, the gene expressions of JNK, ERK, and p38. In particular, 450 mg kg-1 bw Gm-SGP decreased the mRNA expression of these kinases by 42.37% (JNK), 56.25% (ERK), and 38.58% (p38). Next, we determined the total protein expression of JNK, ERK, and p38, as well as their phosphorylation levels. As shown in Figs. 7d-7f, the total protein contents of JNK, ERK, and p38 remained unchanged in the SHAM and OVX groups. However, the phosphorylation levels of these kinases significantly increased in OVX rats. Supplementation of Gm-SGP reduced these levels toward normality. Gm-SGP (450 mg kg-1 bw) decreased the phosphorylation levels of JNK by 42.49%, of ERK by 19.71%, and of p38 by 28.17%. These results suggest that Gm-SGP improves bone loss by inhibiting the activation of the signaling pathways of these MAPKs.

3.10 Gm-SGP Inhibited the Activation of the NF-κB PathwayBesides the MAPK pathways described above, the NF-κB pathway is also involved in the regulation of osteoclastogenesis (Asagiri and Takayanagi, 2007). As one of the most important cytokines in the NF-κB signaling pathway, the mRNA expression of NF-κB p65 was determined. Fig. 8a shows a significant increase in the mRNA expression of NF-κB p65 in the OVX group, and this increase was notably reduced by Gm-SGP. We then determined the total protein expression of NF-κB p65, as well as the level of its phosphorylation. While no statistically significant difference of total protein expression was detected, as shown in Fig. 8b, NF-κB p65 phosphorylation levels were significantly increased in OVX rats compared with those in the SHAM group. Furthermore, Gm-SGP treatment significantly reduced phosphorylation levels of NF-κB p65 compared with that of the OVX group. These results demonstrate that the NF-κB signaling pathway is also involved in the inhibition of bone loss induced by Gm-SGP.

|

Fig. 8 Effects of Gm-SGP on the mRNA and protein expressions of NF-κB, c-Fos, and NFATc1 in OVX-induced osteoporotic rats. (a) mRNA expression of NF-κB. (b) Protein expression of NF-κB. (c) mRNA expression of c-Fos. (d) mRNA expression of NFATc1. (e) Protein expression of NFATc1. Results were normalized by β-actin, and data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8 per group). Multiple comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA. # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 vs. the SHAM group; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 vs. the OVX group. |

Activated MAPKs and NF-κB can translocate to the nucleus and regulate several transcription factors responsible for promoting osteoclastic gene expression, including c-Fos and NFATc1 (Cheng et al., 2012). NFATc1 is considered to be the master regulator of osteoclastogenesis (Takayanagi et al., 2002). To determine whether Gm-SGP influences c-Fos and NFATc1 by inhibiting the MAPK and NF-κB signaling cascades, the expressions of these transcription factors were assessed. As shown in Figs. 8c and 8d, mRNA expression levels of c-Fos and NFATc1 were significantly increased in the OVX group than in the SHAM group. Treatment with Gm-SGP (450 mg kg-1 bw) normalized the expressions of c-Fos by 47.18% and NFATc1 by 40.43% compared with those in the OVX group. The protein expression level of NFATc1 in the OVX group was 1.78 times greater than that in the SHAM group (Fig. 8e). Therefore, Gm-SGP notably down-regulated NFATc1 protein expression.

4 DiscussionIn the present study, we demonstrated that sialoglycoproteins isolated from eggs of G. morhua could inhibit bone resorption in OVX-induced osteoporotic model rats without any harmful side effects on the uterus. We also revealed that the related mechanisms include reduction of the OPG/RANKL ratio and suppression of the MAPK and NF-κB signal pathways.

Bone is an important organ of the human body, and the dynamic equilibrium between formation of new bone by osteoblasts and resorption of old bone by osteoclasts is of vital importance to regulate bone metabolism and maintain a healthy bone mass. ALP, OCN, and DPD have been regarded as the markers associated with postmenopausal osteoporosis (Cundy et al., 2007; Omelon et al., 2009). In the present study, the results revealed that Gm-SGP suppresses OVX-induced increases in bone turnover (both bone formation and resorption). Moreover, the structural response of the bone to Gm-SGP treatment was established by means of bone density scans, biochemical property analyses, and bone microarchitecture scans using DEXA, tensile strength tests, and μCT analysis. Gm-SGP effectively prevented reductions in bone mass and improved biochemical properties and cancellous bone structures in OVX rats. These findings suggest that Gm-SGP can decrease OVX-induced bone loss.

Osteoclasts are tissue-specific multinucleated cells derived from mononuclear macrophage cells in the hematopoietic system of the bone marrow and are primary bone-resorbing cells. TRAP is released by osteoclasts during bone resorption and mediates the degradation of endocytosed matrix products (Zhang et al., 2015). Proteinases, including MMP-9 and Cath-K, are necessary for osteoclastic migration and bone resorption (Delaisse et al., 2000). Gm-SGP inhibited the serum expression levels of all three osteoclastic-specific enzymes in OVX rats, which indicates that the proteins cause substantial suppression of the differentiation, fusion, and resorption of osteoclasts. To detect the underlying mechanism, the gene and protein expressions of intracellular signaling pathways involved in osteoclast differentiation were evaluated.

The OPG/RANKL/RANK system is important for osteoblasts to act on osteoclasts (Ma et al., 2012). RANK, which is located on the surface of osteoclasts (both in the precursor and mature forms), is a common receptor of RANKL and OPG. RANKL, which is released by osteoblasts, is critical for osteoclast precursors to differentiate into mature osteoclasts, and is essential for osteoclast activation and survival. OPG, which acts as a decoy receptor for RANKL, blocks this interaction and inhibits the activation of osteoclasts. The OPG/RANKL ratio is a major determinant of bone mass as this ratio exerts a major effect on osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption (Blair et al., 2006). In this study, we found that OVX downregulated the mRNA and serum levels of OPG, up-regulated the mRNA and serum levels of RANKL, and, therefore, decreased the ratio of OPG/RANKL compared with the corresponding values in SHAM rats. Gm-SGP modulated this course by increasing the ratio of OPG/ RANKL, which indicates its effect on inhibiting bone absorption.

Although RANKL lacks intrinsic enzymatic activity in its intracellular domain, it transduces signaling by recruiting adaptor molecules, such as the proteins of the TRAF family, which are membrane-proximal adaptor molecules. Specifically, genetic experiments show that TRAF6 is required for osteoclast formation and activation (Lomaga et al., 1999). Binding of RANKL to its receptor RANK recruits TRAF6 and subsequently initiates a kinase cascade. QRT-PCR and Western blot analyses showed that Gm-SGP reduces the mRNA and protein expressions of TRAF6, which indicates that Gm-SGP inhibits osteoclastogenesis by down-regulating the expression of TRAF6.

Three major subfamilies of MAPKs (JNK, ERK, and p38) located downstream of TRAF6 have been implicated as key regulators of various intracellular responses and play important roles in the development of osteoclasts. NF-κB is believed to be a major mediator of RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis, and a previous study demonstrated that osteoclastogenesis is blocked by selective inhibition of NF-κB (Jimi et al., 2004). In the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway, activation of NF-κB is linked to a sequential cascade, including IKK-dependent IκBα phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and proteolytic degradation, as well as translocation of cytosolic p65/p50 heterodimers to the nucleus, to exert transcriptional activity (Boyce et al., 2015). In fact, phosphorylation of NF-κB-p65 is also involved in the activation of NF-κB signaling pathway (Doyle et al., 2005). After treatment with Gm-SGP, the gene expression and phosphorylation levels of MAPKs (JNK, ERK, p38) and NF-κB-p65 decreased in OVX rats. These changes indicate that Gm-SGP inhibits osteoclastogenesis through the MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways.

Following the activation of the MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways, various osteoclastogenic transcription factors are induced to mediate osteoclast maturity. Among these factors, c-Fos and NFATc1 play critical roles in regulating osteoclast differentiation, fusion, and activation and are required for bone degradation (Wang et al., 1992; Huang et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2010). NFATc1deficient embryonic stem cells cannot differentiate into osteoclasts. Ectopic expression of NFATc1 causes precursor cells to undergo efficient osteoclast differentiation in the absence of RANKL (Sharma et al., 2007). Mice with c-Fos knockout develop serious osteopetrosis due to failure of osteoclast formation (Wang et al., 1992). Cells lacking c-Fos but containing NFATc1 can differentiate into osteoclasts, which indicates that NFATc1 is located downstream of c-Fos. In this study, Gm-SGP dramatically suppressed the expression of both c-Fos and NFATc1, thereby confirming the inhibitory effect of Gm-SGP on osteoclastogenesis and bone loss.

In summary, our present data demonstrate that Gm-SGP significantly improves osteoporosis in OVX rats and the MAPK and NF-κB pathways are involved in this process. Our research establishes the basis for the novel application of G. morhua eggs as a functional food to inhibit bone resorption and improve osteoporosis.

AcknowledgementThis study is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31371876).

Alvarez, M. J. M., Neyro, J. L. and Castaneda, S., 2016. Therapeutic holidays in osteoporosis: Long-term strategy of treatment with bisphosphonates. Medicina Clinica, 146(1): 24-29. DOI:10.1016/j.medcli.2015.03.017 (  0) 0) |

Anumula, K. R., 1995. Rapid quantitative-determination of sialic acids in glycoproteins by high-performance liquid-chromatography with a sensitive fluorescence detection. Analytical Biochemistry, 230(1): 24-30. DOI:10.1006/abio.1995.1432 (  0) 0) |

Asagiri, M. and Takayanagi, H., 2007. The molecular understanding of osteoclast differentiation. Bone, 40(2): 251-264. DOI:10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.023 (  0) 0) |

Blair, J. M., Zhou, H., Seibel, M. J. and Dunstan, C. R., 2006. Mechanisms of disease: Roles of OPG, RANKL and RANK in the pathophysiology of skeletal metastasis. Nature Clinical Practice Oncology, 3(1): 41-49. DOI:10.1038/ncponc0381 (  0) 0) |

Boyce, B. F., Xiu, Y., Li, J., Xing, L. and Yao, Z., 2015. NF-κB-mediated regulation of osteoclastogenesis. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 30(1): 35-44. DOI:10.3803/EnM.2015.30.1.35 (  0) 0) |

Boyle, W. J., Simonet, W. S. and Lacey, D. L., 2003. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature, 423(6937): 337-342. DOI:10.1038/nature01658 (  0) 0) |

Brar, K. S., 2010. Prevalent and emerging therapies for osteoporosis. Medical Journal Armed Forces India, 66(3): 249-254. DOI:10.1016/S0377-1237(10)80050-4 (  0) 0) |

Cheng, B., Li, J., Du, J., Lv, X., Weng, L. and Ling, C., 2012. Ginsenoside Rb1 inhibits osteoclastogenesis by modulating NF-kappaB and MAPKs pathways. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 50(5): 1610-1615. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.019 (  0) 0) |

Cong, Q., Jia, H., Li, P., Qiu, S., Yeh, J., Wang, Y., Zhang, Z., Ao, J., Li, B. and Liu, H., 2017. p38α MAPK regulates proliferation and differentiation of osteoclast progenitors and bone remodeling in an aging-dependent manner. Scientific Reports, 7: 45964. DOI:10.1038/srep45964 (  0) 0) |

Cundy, T., Horne, A., Bolland, M., Gamble, G. and Davidson, J., 2007. Bone formation markers in adults with mild osteogenesis imperfecta. Clinical Chemistry, 53(6): 1109-1114. DOI:10.1373/clinchem.2006.083055 (  0) 0) |

Dannemann, C., Gratz, K. W., Riener, M. O. and Zwahlen, R. A., 2007. Jaw osteonecrosis related to bisphosphonate therapy: A severe secondary disorder. Bone, 40(4): 828-834. DOI:10.1016/j.bone.2006.11.023 (  0) 0) |

Darnay, B. G., Ni, J., Moore, P. A. and Aggarwal, B. B., 1999. Activation of NF-kappa B by RANK requires tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 6 and NF-kappa B-inducing kinase-Identification of a novel TRAF6 interaction motif. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 274(12): 7724-7731. DOI:10.1074/jbc.274.12.7724 (  0) 0) |

Delaisse, J. M., Engsig, M. T., Everts, V., Ovejero, M. D., Ferreras, M., Lund, L., Vu, T. H., Werb, Z., Winding, B., Lochter, A., Karsdal, M. A., Troen, T., Kirkegaard, T., Lenhard, T., Heegaard, A. M., Neff, L., Baron, R. and Foged, N. T., 2000. Proteinases in bone resorption: Obvious and less obvious roles. Clinica Chimica Acta, 291(2): 223-234. DOI:10.1016/S0009-8981(99)00230-2 (  0) 0) |

Doyle, S. L., Jefferies, C. A. and O'Neill, L. A., 2005. Bruton's tyrosine kinase is involved in p65-mediated transactivation and phosphorylation of p65 on serine 536 during NF-kappa B activation by LPS. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 280(25): 23496-23501. DOI:10.1074/jbc.C500053200 (  0) 0) |

Eastell, R., O'Neill, T. W., Hofbauer, L. C., Langdahl, B., Reid, I. R., Gold, D. T. and Cummings, S. R., 2016. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2. DOI:10.1038/Nrdp.2016.69 (  0) 0) |

Galibert, L., Tometsko, M. E., Anderson, D. M., Cosman, D. and Dougall, W. C., 1998. The involvement of multiple tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-associated factors in the signaling mechanisms of receptor activator of NF-kappaB, a member of the TNFR superfamily. Journal of Biological of Chemistry, 273(51): 34120-34127. DOI:10.1074/jbc.273.51.34120 (  0) 0) |

Goel, A., Raghuvanshi, A., Kumar, A., Gautam, A., Srivastava, K., Kureel, J. and Singh, D., 2015. 9-Demethoxy-medicarpin promotes peak bone mass achievement and has bone conserving effect in ovariectomized mice: Positively regulates osteoblast functions and suppresses osteoclastogenesis. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 411: 155-166. DOI:10.1016/j.mce.2015.04.023 (  0) 0) |

Huang, H., Ryu, J., Ha, J., Chang, E. J., Kim, H. J., Kim, H. M., Kitamura, T., Lee, Z. H. and Kim, H. H., 2006. Osteoclast differentiation requires TAK1 and MKK6 for NFATc1 induction and NF-κB transactivation by RANKL. Cell Death and Differentiation, 13: 1879. DOI:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401882 (  0) 0) |

Jimi, E., Aoki, K., Saito, H., D'Acquisto, F., May, M. J., Nakamura, I., Sudo, T., Kojima, T., Okamoto, F., Fukushima, H., Okabe, K., Ohya, K. and Ghosh, S., 2004. Selective inhibition of NF-kappa B blocks osteoclastogenesis and prevents inflammatory bone destruction in vivo. Nature Medicine, 10(6): 617-624. DOI:10.1038/nm1054 (  0) 0) |

Kjesbu, O. S., Taranger, G. L. and Trippel, E. A., 2006. Gadoid mariculture: Development and future challenges-Introduction. Ices Journal of Marine Science, 63(2): 187-191. DOI:10.1016/j.icesjms.2005.12.003 (  0) 0) |

Lee, Z. H. and Kim, H. H., 2003. Signal transduction by receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B in osteoclasts. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 305(2): 211-214. DOI:10.1016/S0006-291x(03)00695-8 (  0) 0) |

Logar, D. B., Komadina, R., Prezelj, J., Ostanek, B., Trost, Z. and Marc, J., 2007. Expression of bone resorption genes in osteoarthritis and in osteoporosis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism, 25(4): 219-225. DOI:10.1007/s00774-007-0753-0 (  0) 0) |

Lomaga, M. A., Yeh, W. C., Sarosi, I., Duncan, G. S., Furlonger, C., Ho, A., Morony, S., Capparelli, C., Van, G., Kaufman, S., van der Heiden, A., Itie, A., Wakeham, A., Khoo, W., Sasaki, T., Cao, Z., Penninger, J. M., Paige, C. J., Lacey, D. L., Dunstan, C. R., Boyle, W. J., Goeddel, D. V. and Mak, T. W., 1999. TRAF6 deficiency results in osteopetrosis and defective interleukin-1, CD40, and LPS signaling. Genes & Development, 13(8): 1015-1024. (  0) 0) |

Ma, B., Zhang, Q., Wu, D., Wang, Y. L., Hu, Y. Y., Cheng, Y. P., Yang, Z. D., Zheng, Y. Y. and Ying, H. J., 2012. Strontium fructose 1, 6-diphosphate prevents bone loss in a rat model of postmenopausal osteoporosis via the OPG/RANKL/RANK pathway. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, 33(4): 479-489. DOI:10.1038/aps.2011.177 (  0) 0) |

Min, S. K., Kang, H. K., Jung, S. Y., Jang, D. H. and Min, B. M., 2018. A vitronectin-derived peptide reverses ovariectomy-induced bone loss via regulation of osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation. Cell Death and Differentiation, 25(2): 268-281. DOI:10.1038/cdd.2017.153 (  0) 0) |

Morley, P., Whitfield, J. F. and Willick, G. E., 2001. Parathyroid hormone: An anabolic treatment for osteoporosis. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 7(8): 671-687. DOI:10.2174/1381612013397780 (  0) 0) |

Olsen, R. L., Toppe, J. and Karunasagar, L., 2014. Challenges and realistic opportunities in the use of by-products from processing of fish and shellfish. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 36(2): 144-151. DOI:10.1016/j.tifs.2014.01.007 (  0) 0) |

Omelon, S., Georgiou, J., Henneman, Z. J., Wise, L. M., Sukhu, B., Hunt, T., Wynnyckyj, C., Holmyard, D., Bielecki, R. and Grynpas, M. D., 2009. Control of vertebrate skeletal mineralization by polyphosphates. PLoS One, 4(5): e5634. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0005634 (  0) 0) |

Qiao, H., Wang, T. Y., Yu, Z. F., Han, X. G., Liu, X. Q., Wang, Y. G., Fan, Q. M., Qin, A. and Tang, T. T., 2016. Structural simulation of adenosine phosphate via plumbagin and zoledronic acid competitively targets JNK/Erk to synergistically attenuate osteoclastogenesis in a breast cancer model. Cell Death & Disease, 7: e2094. DOI:10.1038/Cddis.2016.11 (  0) 0) |

Richards, J. B., Rivadeneira, F., Inouye, M., Pastinen, T. M., Soranzo, N., Wilson, S. G., Andrew, T., Falchi, M., Gwilliam, R., Ahmadi, K. R., Valdes, A. M., Arp, P., Whittaker, P., Verlaan, D. J., Jhamai, M., Kumanduri, V., Moorhouse, M., van Meurs, J. B., Hofman, A., Pols, H. A. P., Hart, D., Zhai, G., Kato, B. S., Mullin, B. H., Zhang, F., Deloukas, P., Uitterlinden, A. G. and Spector, T. D., 2008. Bone mineral density, osteoporosis, and osteoporotic fractures: A genome-wide association study. Lancet, 371(9623): 1505-1512. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60599-1 (  0) 0) |

Rise, M. L., Hall, J. R., Nash, G. W., Xue, X., Booman, M., Katan, T. and Gamperl, A. K., 2015. Transcriptome profiling reveals that feeding wild zooplankton to larval Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) influences suites of genes involved in oxidation-reduction, mitosis, and selenium homeostasis. Bmc Genomics, 16. DOI:10.1186/S12864-015-2120-1 (  0) 0) |

Sharma, S. M., Bronisz, A., Hu, R., Patel, K., Mansky, K. C., Sif, S. and Ostrowski, M. C., 2007. MITF and PU.1 recruit p38 MAPK and NFATc1 to target genes during osteoclast differentiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 282(21): 15921-15929. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M609723200 (  0) 0) |

Sontag, A. and Krege, J. H., 2010. First fractures among postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism, 28(4): 485-488. DOI:10.1007/s00774-009-0144-9 (  0) 0) |

Taguchi, T., Seko, A., Kitajima, K., Muto, Y., Inoue, S., Khoo, K. H., Morris, H. R., Dell, A. and Inoue, Y., 1994. Structural studies of a novel type of pentaantennary large glycan unit in the fertilization-associated carbohydrate-rich glycopeptide isolated from the fertilized eggs of Oryzias latipes. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 269(12): 8762-8771. (  0) 0) |

Takayanagi, H., Kim, S., Koga, T., Nishina, H., Isshiki, M., Yoshida, H., Saiura, A., Isobe, M., Yokochi, T., Inoue, J., Wagner, E. F., Mak, T. W., Kodama, T. and Taniguchi, T., 2002. Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Developmental Cell, 3(6): 889-901. DOI:10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00369-6 (  0) 0) |

Wada, T., Nakashima, T., Hiroshi, N. and Penninger, J. M., 2006. RANKL-RANK signaling in osteoclastogenesis and bone disease. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 12(1): 17-25. DOI:10.1016/j.molmed.2005.11.007 (  0) 0) |

Wang, F., Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Zhan, Q., Yu, P., Wang, J. and Xue, C., 2016. Sialoglycoprotein isolated from eggs of Carassius auratus ameliorates osteoporosis: An effect associated with regulation of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in rodents. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 64(14): 2875-2882. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b06132 (  0) 0) |

Wang, Z. Q., Ovitt, C., Grigoriadis, A. E., Möhle-Steinlein, U., Rüther, U. and Wagner, E. F., 1992. Bone and haematopoietic defects in mice lacking c-fos. Nature, 360(6406): 741-745. DOI:10.1038/360741a0 (  0) 0) |

Xia, G. H., Wang, S. S., He, M., Zhou, X. C., Zhao, Y. L., Wang, J. F. and Xue, C. H., 2015. Anti-osteoporotic activity of sialoglycoproteins isolated from the eggs of Carassius auratus by promoting osteogenesis and increasing OPG/RANKL ratio. Journal of Functional Foods, 15: 137-150. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2015.03.021 (  0) 0) |

Xia, G. H., Yu, Z., Zhao, Y. L., Wang, Y. M., Wang, S. S., He, M., Wang, J. F. and Xue, C. H., 2015. Sialoglycoproteins isolated from the eggs of Carassius auratus prevents osteoporosis by suppressing the activation of osteoclastogenesis related NF-κB and MAPK pathways. Journal of Functional Foods, 17: 491-503. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2015.05.036 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Y., Guan, H. F., Li, J., Fang, Z., Chen, W. J. and Li, F., 2015. Amlexanox suppresses osteoclastogenesis and prevents ovariectomy-induced bone loss. Scientific Reports, 5. DOI:10.1038/Srep13575 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, Q., Wang, X., Liu, Y., He, A. and Jia, R., 2010. NFATc1: Functions in osteoclasts. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 42(5): 576-579. DOI:10.1016/j.biocel.2009.12.018 (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 18

2019, Vol. 18