2) College of Marine Sciences, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai 201306, China;

3) National Ocean Satellite Shandong Data Application Center, Yantai 264006, China;

4) Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Marine Ecological Restoration, Yantai 264006, China

The Japanese common squid Todarodes pacificus is an economically important squid species for Asia-Pacific countries such as China, Japan, and Korea (Sakurai et al., 2013). This squid has three cohorts with different peak spawning seasons: summer, autumn and winter. At present, the autumn and winter cohorts are largely exploited by international squid fisheries (Sakaguchi and Nakata, 2006). Spawning and fishing grounds for different cohorts of T. pacificus generally distribute with significant geographical difference. For example, for the autumn cohort of T. pacificus, it is widely distributed in the whole waters of the Sea of Japan. Spawning ground mostly occurs in coastal waters of the southern Sea of Japan, particularly in the Tsushima Strait between Japan and Korea. Fishing ground mainly locates in the central waters of the Sea of Japan and western-central coastal waters of Japan (Sakurai et al., 2013) (Fig.1). However, the winter cohort of T. pacificus is extensively distributed in the eastern region of the Sea of Japan, the east coast of Japan and the northwest Pacific Ocean. It commonly spawns in the East China Sea off Kyushu Island south of Japan. In general, fishing operation occurs in the Tsushima Strait and off the eastern coastal waters of Japan (Yu et al., 2018). The autumn cohort of T. pacificus tends to be relatively short and light in weight comparing with the winter cohort. Both are very short-lived with only 1 year lifespan (Song et al., 2012).

|

Fig. 1 Spatial location of distribution range, spawning ground and fishing ground of autumn cohort of Japanese common squid Todarodes pacificus. |

The total catch of T. pacificus remains at a high level with significant interannual variability. Annual catch was maintained at above 300 thousand tons from 1950 to 2010, the highest catch was up to 800 thousand tons (FAO, 2013). Within this period, the catch largely decreased during 1970 – 1990 due to the overexploitation and climate change (Sakurai et al., 2000; Fang et al., 2018). Up to now, the most important fishing countries are Japan and Korea, especially the catch of Japan accounts for the highest proportions among all the fishing countries and regions (Sakurai et al., 2013; Alabia et al., 2016). The East China Sea and Yellow Sea is an important spawning and wintering ground for T. pacificus. Therefore, the Chinese coastal fisheries have also exploited this squid species as bycatch from trawling and purse seining fisheries. In the past, the annual catch of T. pacificus in China was about 48 thousand tons in 1960s, and increased to 60 thousand tons in 1970s and 1980s. In 1990s, the catch from China largely reduced (Fang et al., 2018). However, due to the abundant T. pacificus in the coastal waters of China, it is still the most potentially valuable marine resource for Chinese fisheries.

With regard to T. pacificus, there are increasing studies on its age and growth, spawning and feeding behavior, migration, spatial distribution and other biological characteristics during its different life stages (Choi et al., 2008; Kawabata et al., 2010). However, how T. pacificus responds to climatic and environmental factors at different scales is rarely investigated (Sakurai, 2006). Actually, due to the short life cycle, T. pacificus is similar to other ommastrephidae squid species and extremely sensitive to climate variability and environmental changes at various temporal and spatial scales (Rosa et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2015). For example, Yu et al. (2018) concluded that the El Niño and La Niña events played an important role in regulating the incubating and feeding conditions for T. pacificus during the spawning season and ultimately affected its abundance. Ji et al. (2020) reported that the number of T. pacificus would increase under the future warming scenarios. The main reason was due to the favorable warm conditions to maintain high survival rate of T. pacificus cohorts. Previous studies also demonstrated that the habitat pattern of T. pacificus was driven by the water surface temperature, chlorophyll-a concentration, sea surface height anomaly and other sea surface environmental variables.

Variations in abundance and catch of T. pacificus are largely dependent on the squid recruitment at the early life stage of T. pacificus, which is closely associated with the vertical thermal condition on the spawning ground (Sakurai et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2015). We hypothesized that the catch, biomass and abundance of T. pacificus is determined by the vertical water temperature conditions on the spawning ground and linked with the large-scale climate variability Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). In fact, T. pacificus autumn cohort has high commercial value, it replaced the winter cohort after 1970s and became the main fishing objective for jigging fishing of Japan and Korea (Wang et al., 2005), so exploring the response of the resource abundance of T. pacificus autumn cohort to climate events is significant to the management and utilization of its resources (Wang et al., 2005). Therefore, at the present study, the fluctuations in catch, biomass and abundance of T. pacificus autumn cohort were linked to PDO-related long-term variability of vertical water temperature at depths of 0 – 100 m. The purposes of this study are to 1) investigate the variation in vertical water temperature under positive and negative PDO phase; 2) examine the spatial and temporal correlations between the PDO with the water temperature at depth of 0 – 100 m on the spawning ground; 3) assess the impacts of the PDO regime shift on biomass and catch per unit effort (CPUE) of the autumn cohort of T. pacificus.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Fisheries and Environmental DataJapan carries out annually comprehensive marine species monitoring survey and assessment on economically important fishery species and provides very detailed report on the stock status of a specific species (Yu et al., 2018). In this study, the fisheries data from 1977 to 2015 including annual biomass and CPUE data were obtained from the Japanese annual report of stock assessment for the autumn cohort of T. pacificus (http://abchan.fra.go.jp/digests27/details/2719.pdf). The CPUE data was regarded as a reliable indicator of the squid abundance (Chen et al., 2008).

Vertical water temperatures at depths of 0 m (Temp_0 m), 50 m (Temp_50 m) and 100 m (Temp_100 m) were included in the analysis (Wang et al., 2005; Sakurai et al., 2013). All the water temperature data were obtained from the Asia Pacific Data Research Center (http://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu/las_ofes/v6/dataset?catitem=71). The spatial and temporal resolution of the data was monthly and 0.25° covering the main spawning ground of T. pacificus between 125° – 137°E and 30° – 37°N. The monthly PDO index data from 1977 to 2015 were from the Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean (http://research.jisao.washington.edu/pdo/PDO.latest).

2.2 Examining the PDO-Related Variations of Vertical Water TemperatureIn order to show how vertical water temperatures respond to PDO regime shift, the interannual variability in water temperatures at depths of 0 m, 50 m and 100 m was examined from 1977 to 2015. The averaged water temperature from 1977 to 1998 during the positive PDO phase and from 1999 to 2015 during the negative PDO phase was further determined and compared. Correspondingly, the spatial distribution of the average water temperature anomaly at each water depth was drawn in each PDO phase. Moreover, temporal and spatial relationships between the PDO index and Temp_0 m, Temp_50 m and Temp_100 m were evaluated during 1977 – 2015 based on the cross-correlation method (Feng et al., 2021). Based on the analysis, the spatio-temporal changes of water temperature at the three critical water depths were examined in relation to PDO.

2.3 Evaluating the Relationship Between the PDO Regime Shift and T. pacificusPrevious studies have concluded that the suitable spawning ground (SSG) for T. pacificus is located in a preferred water temperature range between 19.5℃ and 23℃ based on the observation and experiment (Sakurai et al., 2013). The SSG condition is a vital factor affecting the T. pacificus abundance. Thus, the percentage of SSG range was determined from 1997 to 2015 as well as the averaged SSG percentage from 1977 to 1998 during the positive PDO phase and from 1999 to 2015 during the negative PDO phase. Boxplot approach was further used to show and compare the SSG percentages under different PDO phases. Spatial distribution of the averaged SSD in the Tsushima Strait and East China Sea was further drawn in the positive and negative PDO phase in order to show the changes of SSG range in relation to the PDO regime shift.

With regard to the relationship between the PDO regime shift and the autumn cohort of T. pacificus, the variability trend of the annual PDO index, CPUE and biomass combined with the average CPUE and biomass in different PDO phase were initially examined and compared. In addition, cross-correlation analysis was further applied to evaluate the relationship between the PDO index and the fisheries parameters of squid species. Temporal and spatial relationships between the CPUE (and also biomass) and vertical water temperature including Temp_0 m, Temp_50 m and Temp_100 m were ultimately assessed.

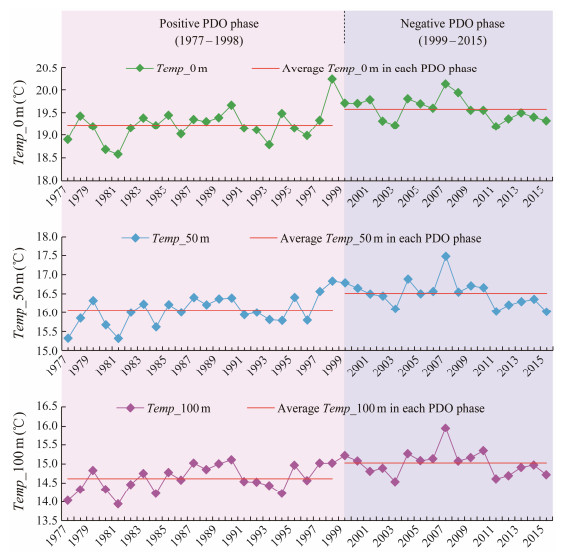

3 Results 3.1 Changes of Vertical Water Temperature During Different PDO PhasesThe vertical water temperature on the spawning ground of the T. pacificus autumn cohort decreased with the water depths, it fluctuated from 18.0℃ to 20.5℃ at the sea surface, from 15.0℃ to 18.0℃ at depth of 50 m, and from 13.5℃ to 16.5℃ at depth of 100 m, respectively (Fig.2). It was clearly shown that Temp_0 m, Temp_50 m and Temp_ 100 m exhibited significantly and similarly interannual variability but with large differences between the positive and negative PDO phases. Relatively lower water temperatures were found over 1977 – 1998 during the positive PDO phase, while higher vertical temperature occurred from 1999 to 2015 in the negative PDO phase.

|

Fig. 2 Annual water temperature at depths of 0 m (Temp_0 m), 50 m (Temp_50 m) and 100 m (Temp_100 m) from September to November during 1977 – 2015 and the average Temp_0 m, Temp_50 m and Temp_100 m in the positive and negative phases of Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). |

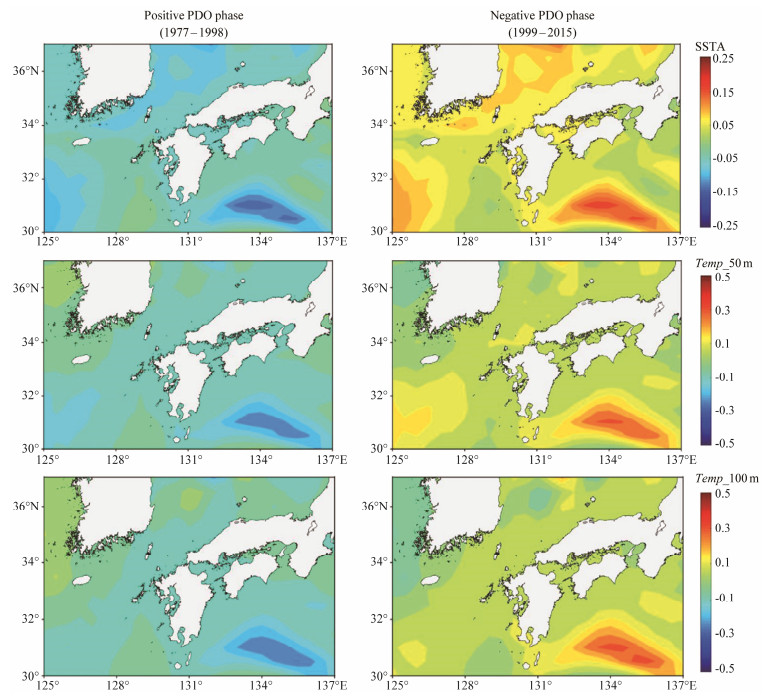

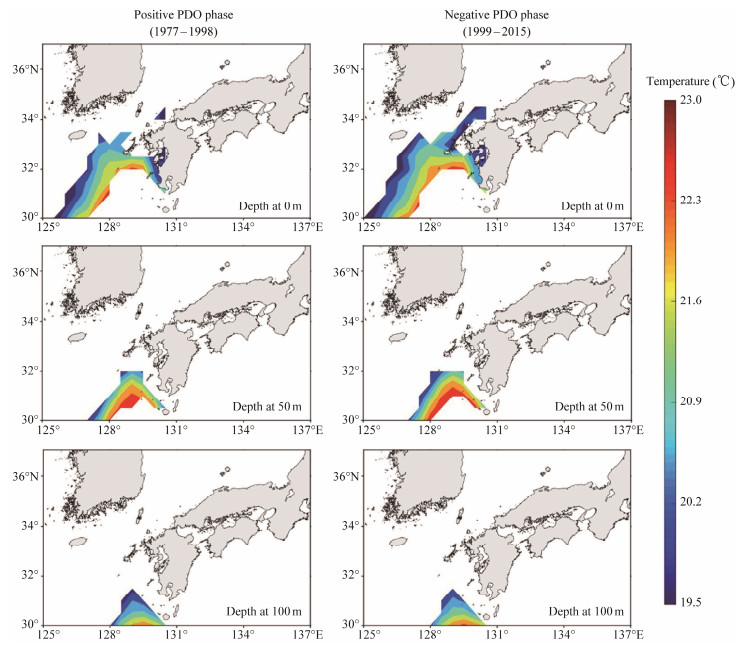

In terms of spatial distribution of the vertical water temperature at the three critical water layers for T. pacificus, it also showed significant differences with the PDO regime shift (Fig.3). During the positive PDO phase, the spawning ground of T. pacificus was almost occupied by the negative water temperature anomalies. Particularly, three subareas especially at the sea surface were accompanied with much lower cool waters in the southwestern waters of the spawning ground in the East China Sea, southeastern waters in the western Pacific Ocean, and the waters within the Tsushima Strait and southern area of the Japan Sea. On the contrary, it was observed that warm waters mostly occurred in the negative PDO phase on the spawning ground especially in the corresponding three subareas.

|

Fig. 3 Spatial distribution of water temperature anomalies at depths of 0 m (Temp_0 m), 50 m (Temp_50 m) and 100 m (Temp_100 m) in the positive and negative phases of Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). |

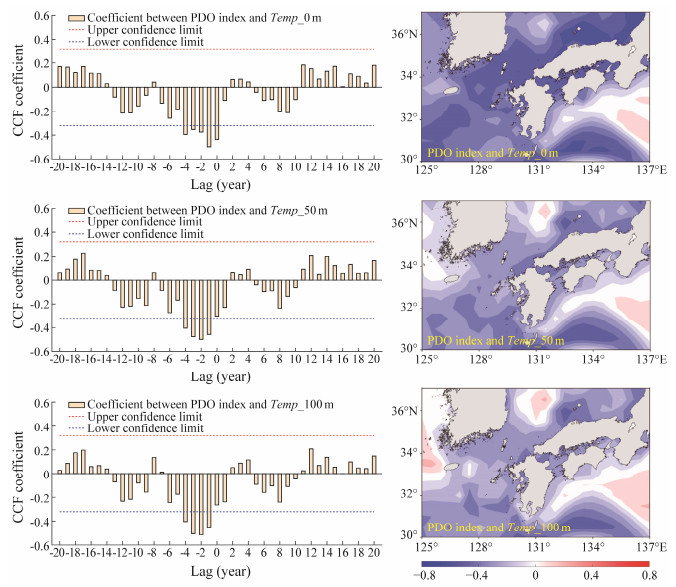

Cross-correlation analysis revealed that the PDO index exhibited a significantly negative relationship with the vertical water temperatures at different depths with time lag at −4 – 0 months at Temp_0 m, −4 – (−1) months at Temp_50 m, and −4 – (−1) months at Temp_100 m, respectively (Fig.4). It implied that the water temperature on the spawning ground of T. pacificus responded to the PDO variability quickly, and positive PDO would yield cool waters and negative PDO would yield warm waters within the study area. Spatial correlation method also showed that the spawning ground was mainly occupied by the negative correlation coefficients between the PDO index and vertical water temperatures. The relationship showed positive only within a very limited area in the western waters of the study area.

|

Fig. 4 Temporal (left panel) and spatial (right panel) relationship between the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) index and water temperature at depths of 0 m (Temp_0 m), 50 m (Temp_50 m) and 100 m (Temp_100 m) during 1977 – 2015. The red and blue broken lines on the lagged time series plots represented the upper and lower confidence limit at the 95% significance level, respectively. CCF, cross correlation function. |

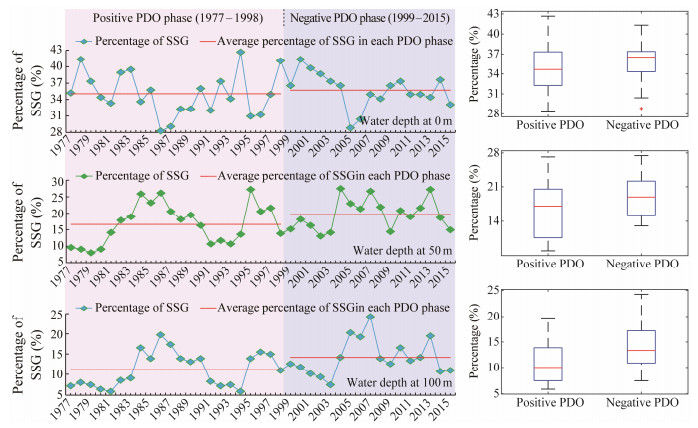

Percentage of SSG fluctuated from year to year during 1977 – 2015 with significant difference at the three critical water depths and under different PDO phase (Fig.5). It ranged from 25% to 45% at the surface waters; from 5% to 30% at depth of 50 m; and from 4% to 28% at depth of 100 m, respectively, showing a decreasing trend from sea surface to the deep waters. In addition, the SSG range greatly changed with the PDO regime shift. Based on the average percentage of SSG in each PDO phase and the boxplot analysis of the annually SSG, it showed that the SSG dramatically enlarged in the negative PDO phase and contracted in the positive PDO phase, suggesting that the negative PDO phase was favorable for yielding a better spawning condition. Furthermore, spatial distribution of the average SSG with water temperature between 19.5℃ and 23.0℃ revealed a relatively larger range in the negative PDO phase relative to the positive PDO phase (Fig.6). The averaged SSG area tended to move from northwestward to southeastward within the study region.

|

Fig. 5 Annual percentage of suitable spawning ground (SSG) at depths of 0 m, 50 m and 100 m from September to November during 1977 – 2015 and the average SSG in the positive and negative phases of Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) (left panel). The right panel shows the boxplot of SSG in the positive and negative PDO phases, respectively, at depths of 0 m, 50 m and 100 m. |

|

Fig. 6 Spatial distribution of the average suitable spawning ground (SSG) with water temperature between 19.5℃ and 23.0℃ in the positive and negative phases of Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). |

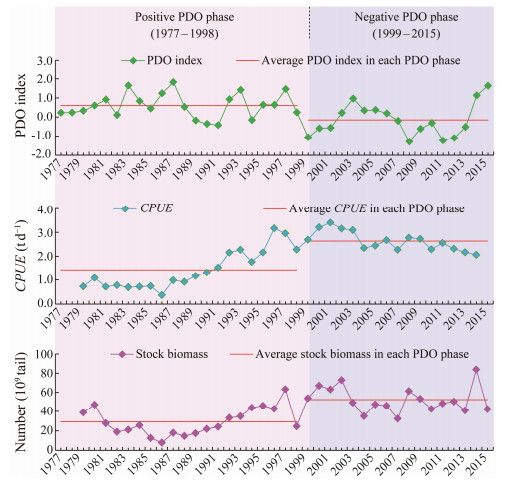

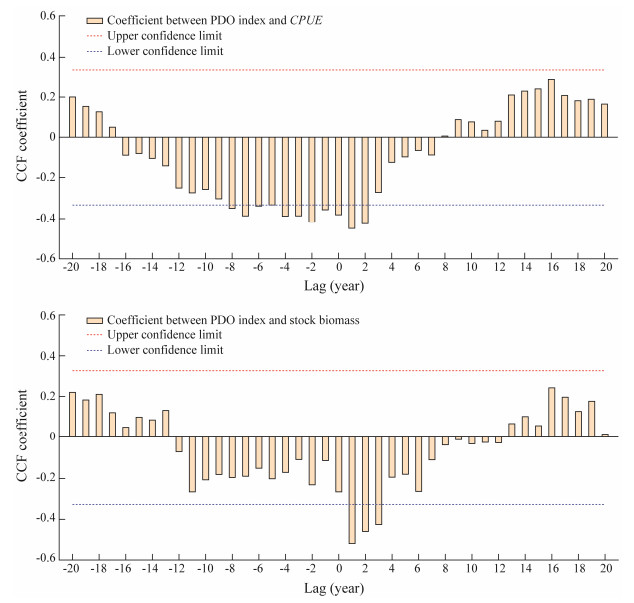

Fig.7 showed the annual PDO index, CPUE and stock biomass (estimated number of squid individuals) during 1977 – 2015 in both the positive and negative PDO phases. The PDO index was high in the positive PDO phase with most of the values higher than 0, and low in the negative PDO phase with most of the values lower than 0. The CPUE exhibited an increasing trend from 1977 to 2015, varying from 0.2 t d−1 to 4.0 t d−1. Comparing the CPUE in the positive and negative PDO phases, we can observe that it was relatively low in the positive PDO phase and high in the negative PDO phase. For the stock biomass, it was basically similar to the variation of the CPUE. The biomass gradually increased from the positive PDO phase to the negative PDO phase (Fig.7). Cross-correlation analysis revealed that the PDO index exhibited a significantly negative relationship with the CPUE and stock biomass of the autumn cohort of T. pacificus, with time lag at −8 – 2 months and 1 – 3 months, respectively (Fig.8). The highest correlation coefficient occurred at the time lag of 1 month, implying that the quick response of CPUE and biomass of T. pacificus to the PDO.

|

Fig. 7 Annual Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) index, catch per unit effort (CPUE) and stock biomass (estimated number of squid individuals) during 1977 – 2015 and the average PDO index, CPUE and stock biomass in the positive and negative PDO phases. |

|

Fig. 8 Cross-correlation between the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) index and annual catch per unit effort (CPUE) and stock biomass (estimated number of squid individuals) during 1977 – 2015. CCF, cross correlation function. |

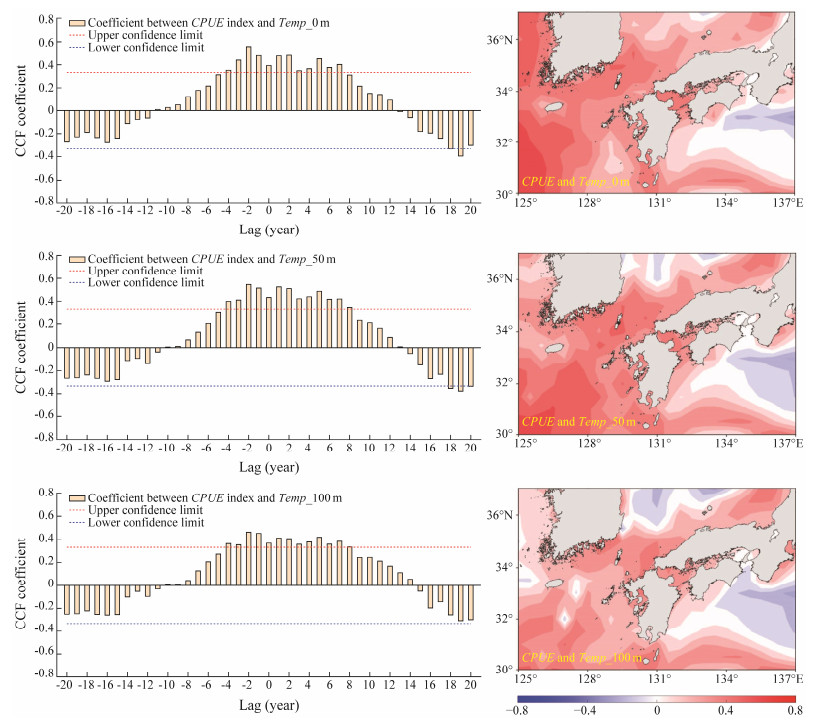

Fig.9 showed the temporal and spatial relationship between the CPUE and water temperature at depths of 0 m, 50 m and 100 m during 1977 – 2015. It suggested that the CPUE was significantly and positively associated with the vertical water temperatures at the three water depths with time lag at −4 – 7 months at Temp_0 m, −4 – 8 months at Temp_50 m, and −4 – 8 months at Temp_100 m, respectively (Fig.9). High water temperature tended to yield high CPUE of the autumn cohort of T. pacificus. Spatial correlation results also showed that the spawning ground was mainly occupied by the positive correlation coefficients between the CPUE and the vertical water temperatures. In the western waters of the study area, only a very small area was occupied with negative correlation coefficients.

|

Fig. 9 Temporal (left panel) and spatial (right panel) relationship between catch per unit effort (CPUE) and water temperature at depths of 0 m (Temp_0 m), 50 m (Temp_50 m) and 100 m (Temp_100 m) during 1977 – 2015. The red and blue broken lines on the lagged time series plots represented the upper and lower confidence limits at the 95% significance level, respectively. CCF, cross correlation function. |

For short-lived marine species, the environmental variability on the spawning ground during the early life stage can largely affect the recruitment and consequently play an important role in regulating the abundance and biomass during their adult stage (Cao et al., 2009). Suitable spawning ground conditions can be favorable for yielding a large species population. On the contrary, adverse environmental conditions may result in a dramatic decrease in the population (Yu et al., 2015). Therefore, examining the environmental changes on the spawning ground and the relevant spawning conditions can help understand how the abundance and biomass of marine species change with the environments. For example, Yatsu et al. (2010) reported that the driftnet fishery and water surface temperature from hatching to recruitment could be used to explain stock abundance and growth of neon flying squid Ommastrephes bartramii. This finding was also proved by Chen et al. (2007). They proposed that the El Niño and La Niña events would lead to an increase and a decrease in the recruitment of O. bartramii, respectively, through changing the water temperature during the spawning period and affect the squid abundance during the feeding period. Li et al. (2018) indicated that the water temperature and current velocity in April on the spawning ground of chub mackerel Scomber japonicus strongly influences the recruitment in the East China Sea and drove the interannual variability of S. japonicus.

Based the large amounts of the studies in Japan, it is well known that the early life stage of T. pacificus stock, especially its spawning behaviors during the tank experiments and in situ observation (Bower and Sakurai, 1996; Goto, 2002; Kim et al., 2011). Both the winter and autumn T. pacificus stocks generally lay spherical, neutrally buoyant egg masses above/near the pycnocline in the oceans (Sakurai et al., 2000). The suitable temperature range in the early life stage of T. pacificus varies with squid development. Embryonic development begins within the temperature between 15℃ and 23℃ (Bower, 1997). After 4 – 6 days, the paralarvae start to hatch, the suitable water temperature is from 18℃ and 19℃ (Bower and Sakurai, 1996). Studies suggested that the favorable hatchings of T. pacificus mainly occur at sea water temperature range 17 – 23℃, and the most preferred temperature is between 19.5 and 23℃ (Sakurai et al., 2013). The early life stage of T. pacificus also shows vertical distribution on the spawning ground. Egg mass is generally distributed in the sea surface, paralarvae then perform vertical movement, gradually descending with the water column (Yamamoto et al., 2007). Older paralarvae mainly occupy the waters within the depth range 20 – 80 m (Kim et al., 2011, 2014). Combined all the information together, in this study, the thermal condition and suitable spawning ground with water temperature between 19.5 and 23℃ were selected and examined and further linked to the PDO regime shift and variations in abundance and biomass of T. pacificus.

The PDO is a long-lived El Niño-like pattern of Pacific climate variability (Miller et al., 2004). It is first detected by the fisheries scientist Steven Hare when he studied the connections between Alaska salmon production cycles and Pacific climate in 1996 (Mantua et al., 1997). There are two climate oscillations (positive PDO and negative PDO) with distinct spatial and temporal characteristics of North Pacific sea surface temperature variability. In the past century, two full PDO cycles occurred with negative PDO phase prevailed during 1890 – 1924 and again during 1947 – 1976, with positive PDO phase dominated from 1925 – 1946 and again from 1977 – mid – 1990s (Mantua and Hare, 2002). In the 21st century, studies have reported that the negative PDO phase dominated in recent decade from 1999. These previous results are basically similar to this study (Wen et al., 2020a, 2020b). Based on the PDO index, the PDO cycle from 1977 to 2015 was divided into two phases from 1977 to 1998 (positive) and from 1999 to 2015 (negative). The PDO not only directly impacts the biological and physical environments in the North Pacific Ocean, but also affects the environments in the adjacent waters even in the whole global ocean. For example, biophysical environment on the fishing ground of jumbo flying squid Dosidicus gigas off Peru, spiny lobster Panulirus interruptus and market squid Doryteuthis opalescens in the Southern California Bright is closely related to the PDO climate (Koslow and Allen, 2011; Koslow et al., 2012; Wen, et al., 2020a). In this study, positive PDO phase was consistent with cool water temperature while negative PDO phase was in accordance with warm water temperature from the sea surface to deep waters within the spawning ground of T. pacificus. Our findings indicated that the PDO was a critical factor in driving the decadal variability of thermal conditions on the spawning ground of T. pacificus.

An increasing number of studies have proved that the PDO has yielded profound impacts on regional oceanographic conditions, marine ecosystem, and also strongly affected the fisheries (Mantua and Hare, 2002; Noguchi-Aita et al., 2018). In the Southeast Pacific Ocean, the habitat pattern of D. gigas and T. murphyi were sensitive to the PDO regime shift. Suitable habitat distribution and range of these two species showed opposite variability pattern in each PDO phase (Yu et al., 2021). In the western Pacific Ocean, a linkage was found between the abundance and distribution of O. bartramii and Pacific saury Cololabis saira within the Kuroshio and Oyashio Current System and the PDO variability (Tian et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2016). With respect to the autumn cohort of T. pacificus, it was also vulnerable to the regime shift of the PDO phase. On the basis of all the results, the mechanism of the PDO regulating the T. pacificus dynamics was detected. First, the vertical water temperature on the spawning ground was strongly affected by the PDO. Cool waters occurring in the positive PDO phase was unfavorable for squid development; while the warm waters in the negative PDO phase was suitable for squid growth and survival (Sakurai et al., 1996). Then, the changing water temperature with the PDO regimes subsequently affected the preferred spawning range of the T. pacificus cohort. It yielded enlarged suitable spawning areas in the negative PDO phase and contracted spawning ground in the positive PDO phase. With the impacts of changing vertical water temperature and SSG, consequently, the PDO variability caused the significant changes of squid abundance and biomass.

In conclusion, this study examined the relationship between PDO-related environmental variability on the spawning ground and the abundance and biomass of T. pacificus in a long-term time scale. The PDO regime shift strongly affected the thermal condition and spawning ground range of the autumn cohort of T. pacificus. Comparing to what happened in the negative PDO, the waters from the surface to the deep became cool in the positive PDO phase, correspondingly, the area of SSG largely contracted at different depths. Consequently, the CPUE and stock biomass of T. pacificus profoundly decreased. Therefore, the PDO regime shift-driven changes in vertical thermal condition and SSG ranges yielded substantial impacts on T. pacificus abundance. In addition to the thermal condition considered in this study, the early life stage of T. pacificus was also influenced by feeding availability (Yu et al., 2018), sea surface salinity (Furukawa and Sakurai, 2008), current, etc. However, sea temperature only represents the thermal conditions of the habitat of T. pacificus. As a cephalopod vulnerable to marine environmental changes and climate events, its growth, reproduction, migration and other processes not only rely on thermal support, but also the bait richness and marine physical conditions in the habitat waters. These conditions will have a certain impact on its resource abundance or supplement. Thus, future studies will consider more environmental variables such as chlorophyll-a concentration into the analysis or adding some species distribution model (SDM) to analyze its response to climate change.

AcknowledgementsThis study was financially supported by the Shanghai Talent Development Funding for the Project (No. 2021078), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41-906073), the Construction and Application Demonstration of Natural Resources Satellite Remote Sensing Technology System (No. 202101003).

Alabia I. D., Dehara M., Saitoh S. I., Hirawake T.. 2016. Seasonal habitat patterns of Japanese common squid (Todarodes pacificus) inferred from satellite-based species distribution models. Remote Sensing, 8(11): 921. DOI:10.3390/rs8110921 (  0) 0) |

Bower, J. R., 1997. A biological study egg masses and paralarvae of the squid Todarodes pacificus. PhD thesis. Hokkaido Uni versity.

(  0) 0) |

Bower, J. R., and Sakurai, Y., 1996. Laboratory observations on Todarodes pacificus (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae) egg masses. American Malacological Bulletin, 13 (1-2): 65-71, http://hdl.handle.net/2115/35242.

(  0) 0) |

Cao J., Chen X. J., Chen Y.. 2009. Influence of surface oceanographic variability on abundance of the western winter-spring cohort of neon flying squid Ommastrephes bartramii in the NW Pacific Ocean. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 381: 119-127. DOI:10.3354/meps07969 (  0) 0) |

Chen X. J., Chen Y., Tian S. Q., Liu B. L., Qian W. G.. 2008. An assessment of the west winter-spring cohort of neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii) in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. Fisheries Research, 92(2-3): 221-230. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2008.01.011 (  0) 0) |

Chen X. J., Zhao X. H., Chen Y.. 2007. Influence of El Niño/La Niña on the western winter–spring cohort of neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii) in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 64(6): 1152-1160. DOI:10.1093/icesjms/fsm103 (  0) 0) |

Choi K., Lee C. I., Hwang K., Kim S. W., Park J. H., Gong Y.. 2008. Distribution and migration of Japanese common squid, Todarodes pacificus, in the southwestern part of the East (Japan) Sea. Fisheries Research, 91(2-3): 281-290. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2007.12.009 (  0) 0) |

Fang Z., Chen X. J.. 2018. Review on fishery of Japanese flying squid Todarodes pacificus. Marine Fisheries, 40(1): 102-116. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1004-2490.2018.01.012 (  0) 0) |

FAO, 2013. Fish Stat Plus (for fisheries statistical time series). http://www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/software/fishstat.

(  0) 0) |

Feng Z. P., Zhang Y. J., Yu W., Chen X. J.. 2021. Differences in habitat pattern response to various ENSO events in Trachurus murphyi and Dosidicus gigas located outside the exclusive economic zones of Chile. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 28(9): 1195-1207. DOI:10.12264/JFSC2020-0533 (  0) 0) |

Furukawa H., Sakurai Y.. 2008. Effect of low salinity on the survival and development of Japanese common squid Todarodes pacificus hatchling. Fisheries Science, 74(2): 458-460. DOI:10.1111/j.1444-2906.2008.01546.x (  0) 0) |

Goto T.. 2002. Paralarval distribution of the ommastrephid squid Todarodes pacificus during fall in the southern Sea of Japan, and its implication for locating spawning grounds. Bulletin of Marine Science, 71(1): 299-312. DOI:10.1016/S0025-3227(02)00178-0 (  0) 0) |

Ji F., Guo X., Wang Y., Takayama K.. 2020. Response of the Japanese flying squid (Todarodes pacificus) in the Japan Sea to future climate warming scenarios. Climatic Change, 159(4): 601-618. DOI:10.1007/s10584-020-02689-3 (  0) 0) |

Kawabata A., Yatsu A., Ueno Y., Suyama S., Kurita Y.. 2010. Spatial distribution of the Japanese common squid, Todarodes pacificus, during its northward migration in the western North Pacific Ocean. Fisheries Oceanography, 15(2): 113-124. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2419.2006.00356.x (  0) 0) |

Kim J. J., Kim C., Lee J., Kim S.. 2014. Seasonal characteristics of Todarodes pacificus paralarval distribution in the northern East China Sea. Korean Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 47(1): 59-71. DOI:10.5657/KFAS.2014.0059 (  0) 0) |

Kim J. J., Lee H. H., Kim S., Park C.. 2011. Distribution of larvae of the common squid Todarodes pacificus in the northern East China Sea. Korean Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 44(3): 267-275. DOI:10.5657/KFAS.2011.0267 (  0) 0) |

Kim J. J., Stockhausen W., Kim S., Cho Y. K., Seo G. H., Lee J. S.. 2015. Understanding interannual variability in the distribution of, and transport processes affecting, the early life stages of Todarodes pacificus using behavioral-hydrodynamic modeling approaches. Progress in Oceanography, 138: 571-583. DOI:10.1016/j.pocean.2015.04.003 (  0) 0) |

Koslow, J. A., and Allen, C., 2011. The influence of the ocean environment on the abundance of market squid, Doryteuthis (Loligo) opalescens, paralarvae in the Southern California Bight. California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations Report, 52: 205-213, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285577966.

(  0) 0) |

Koslow, J. A., Rogers-Bennett, L., and Neilson, D. J., 2012. A time series of California spiny lobster (Panulirus interruptus) phyllosoma from 1951 to 2008 links abundance to warm oceanographic conditions in southern California. California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations Report, 53: 132-139, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287896671.

(  0) 0) |

Li Y. S., Pan L. Z., Guan W. J., Jiao J. P.. 2018. Simulation study of individual-based model on interannual fluctuation of Chub mackerel's (Scomber japonicus) recruitment in the East China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 40(1): 87-95. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0253-4193.2018.01.010 (  0) 0) |

Mantua N. J., Hare S. R.. 2002. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation. Journal of Oceanography, 58(1): 35-44. DOI:10.1023/A:1015820616384 (  0) 0) |

Mantua N. J., Hare S. R., Zhang Y., Wallace J. M., Francis R. C.. 1997. A Pacific interdecadal climate oscillation with impacts on salmon production. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 78(6): 1069-1080. DOI:10.1175/1520-0477(1997)078<1069:APICOW>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Miller A. J., Chai F., Chiba S., Moisan J. R., Neilson D. J.. 2004. Decadal-scale climate and ecosystem interactions in the North Pacific Ocean. Journal of Oceanography, 60(1): 163-188. DOI:10.1023/B:JOCE.0000038325.36306.95 (  0) 0) |

Noguchi-Aita M., Chiba S., Tadokoro K.. 2018. Response of lower trophic level ecosystems to decadal scale variation of climate system in the North Pacific Ocean. Oceanography in Japan, 27(1): 43-57. DOI:10.5928/kaiyou.27.1_43 (  0) 0) |

Rosa A. L., Yamamoto J., Sakurai Y.. 2011. Effects of environmental variability on the spawning areas, catch, and recruitment of the Japanese common squid, Todarodes pacificus (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae), from the 1970s to the 2000s. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 68(6): 1114-1121. DOI:10.1093/icesjms/fsr037 (  0) 0) |

Sakaguchi, K., and Nakata, J., 2006. Age and population structure of Japanese common squid, Todarodes pacificus, off northern Hokkaido[Japan] during 2001. Bulletin of the Japanese Society of Fisheries Oceanography, 70: 16-22, http://www.jsfo.jp/contents/pdf/70-1-16.pdf.

(  0) 0) |

Sakurai Y.. 2006. How climate change might impact squid populations and ecosystems: A case study of the Japanese common squid, Todarodes pacificus. Globec Report, 24: 33-34. (  0) 0) |

Sakurai, Y., Bower, J. R., Nakamura, Y., Yamamoto, S., and Watanabe, K., 1996. Effects of temperature on development and survival of Todarodes pacificus embryos and paralarvae. American Malacological Bulletin, 13 (1/2): 89-95, http://hdl.Handle.net/2115/35244.

(  0) 0) |

Sakurai, Y., Kidokoro, H., Yamashita, N., Yamamoto, J., Uchikawa, K., and Takahara, H., 2013. Todarodes pacificus, Japanese common squid. Advances in Squid Biology, Ecology and Fisheries, Part Ⅱ – Oegopsid Squids. Nova Biomedical, New York, 249-272, https://www.novapublishers.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/978-1-62808-333-0_ch9.pdf.

(  0) 0) |

Sakurai Y., Kiyofuji H., Saitoh S. I., Yamamoto J., Goto T., Mori K., et al. 2002. Stock fluctuations of the Japanese common squid, Todarodes pacificus, related to recent climate changes. Fisheries Science, 68(sup1): 226-229. DOI:10.2331/fishsci.68.sup1_226 (  0) 0) |

Sakurai Y., Kiyofuji H., Saitoh S., Goto T., Hiyama Y.. 2000. Changes in inferred spawning areas of Todarodes pacificus (Cephalopoa: Ommastrephidae) due to changing environmental conditions. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 57(1): 24-30. DOI:10.1006/jmsc.2000.0667 (  0) 0) |

Song H., Yamashita N., Kidokoro H., Sakurai Y.. 2012. Comparison of growth histories of immature Japanese common squid Todarodes pacificus between the autumn and winter spawning cohorts based on statolith and gladius analyses. Fisheries Science, 78(4): 85-790. DOI:10.1007/s12562-012-0503-7 (  0) 0) |

Tang F. H., Shi Y. R., Zhu J. X., Wu Z. L., Wu Y. M., Cui X. S.. 2015. Influence of marine environment factors on temporal and spatial distribution of Japanese common squid fishing grounds in the Sea of Japan. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 22(5): 1036-1043. DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1118. 2015.14516 (  0) 0) |

Tian Y. J., Ueno Y., Suda M., Akamine T.. 2004. Decadal variability in the abundance of Pacific saury and its response to climatic/oceanic regime shifts in the northwestern subtropical Pacific during the last half century. Journal of Marine Systems, 52(1-4): 235-257. DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2004. 04.004 (  0) 0) |

Wang G. Y., Chen X. J.. 2005. Marine Economic Ommastrephidae Resources and Fisheries in the World. Ocean Press, Beijing, 160-186.

(  0) 0) |

Wen J., Lu X. Y., Yu W., Chen X. J., Liu B. L.. 2020a. Decadal variations in habitat suitability of Dosidicus gigas in the Southeast Pacific Ocean off Peru. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 42(6): 36-43. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0253-4193.2020. 06.005 (  0) 0) |

Wen J., Yu W., Chen X. J.. 2020b. Seasonal habitat variation of jumbo flying squid Dosidicus gigas off Peru under different climate conditions. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 27(12): 1464-1476. DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1118.2020.20 162 (  0) 0) |

Yamamoto J., Shimura T., Uji R., Masuda S., Watanabe S., Sakurai Y.. 2007. Vertical distribution of Todarodes pacificus (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae) paralarvae near the Oki Island, southwestern Sea of Japan. Marine Biology, 153(1): 7-13. DOI:10.1007/s00227-007-0775-0 (  0) 0) |

Yatsu A., Watanabe T., Mori J., Nagasawa K., Ishida Y., Meguro T., et al. 2010. Interannual variability in stock abundance of the neon flying squid, Ommastrephes bartramii, in the North Pacific Ocean during 1979 – 1998: Impact of driftnet fishing and oceanographic conditions. Fisheries Oceanography, 9(2): 163-170. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2419.2000.00130.x (  0) 0) |

Yu W., Chen X. J., Chen Y., Yi Q., Zhang Y.. 2015. Effects of environmental variations on the abundance of western winter-spring cohort of neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii) in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 34(8): 43-51. DOI:10.1007/s13131-015-0707-7 (  0) 0) |

Yu W., Chen X. J., Yi Q., Chen Y.. 2016. Influence of oceanic climate variability on stock level of western winter-spring cohort of Ommastrephes bartramii in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 37(17): 3974-3994. DOI:10.1080/01431161.2016.1204477 (  0) 0) |

Yu W., Wen J., Chen X. J., Gong Y., Liu B. L.. 2021. Trans-Pacific multidecadal changes of habitat patterns of two squid species. Fisheries Research, 233: 105762. DOI:10.1016/j.fishres.2020.105762 (  0) 0) |

Yu W., Zhang Y., Chen X. J., Yi Q., Qian W. G.. 2018. Response of winter cohort abundance of Japanese common squid Todarodes pacificus to the ENSO events. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 37(6): 61-71. DOI:10.1007/s13131-018-1186-4 (  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22