研究表明,手在病毒传播的过程中充当了直接或间接的载体的角色,洗手对于预防和控制病毒性疾病的流行传播具有重要的意义[1]。目前市场上有许多需要配合洗手过程使用的手卫生产品,都宣称具有除病毒的性能,但是对其效果进行评价的标准方法却非常有限。国内外的相关研究和标准方法,在安全性、可操作性及实用性上都有很大的局限性[2 – 6]。本研究以噬菌体为替代病毒,离体仿真皮为实验载体,设计试验流程,分析并确定关键影响因素的试验条件,建立了离体试验方法,并对其适用性和稳定性进行了验证。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料(1)实验病毒与宿主 根据世界卫生组织手卫生指南[7]中的病原菌替代原则及目标病毒的结构、大小和生物学特性,选取噬菌体 φX174(ATCC13706-B1)、MS2(ATCC15597-B1),φ6((NBRC 105899)作为实验病毒(见表1),上述病毒及其宿主分别购自ATCC(American type culture collection,美国模式培养物集存库)和NBRC(NITE Biological Resource Center日本技术评价研究所生物资源中心),并按照菌种保藏中心推荐的培养基和方法提取噬菌体,按双层平板法[8]进行计数。(2)实验载体:离体仿真皮(vitro-skin,IMS)。(3)洗手产品:市售舒肤佳纯白清香型香皂、舒肤佳清香型洗手液(以下简称香皂、洗手液)。

| 表 1 用作替代病毒的噬菌体 |

1.2 主要试剂与仪器

拍打式均质器(Bag Mixer 400 mL,法国Inter science公司)、移液枪(Eppendorf)、电子天平(常熟双杰测试仪器厂)、摇床(上海智诚分析仪器制造有限公司)、生化培养箱(北京东联哈尔仪器制造有限公司)、水浴锅(重庆四达实验仪器厂),其他小型设备如温度计、量筒、玻璃样品瓶、密封袋(广东环凯生物生物计数有限公司)等;底层培养基:营养琼脂培养基(NA),可使用干粉培养基,琼脂含量一般为1.2 %;上层培养基,采用半固体营养琼脂培养基,琼脂浓度为0.6 %;液体培养基:营养肉汤培养基(NB),通用配方或干粉成品培养基;0.1 %蛋白胨生理盐水:0.1 %蛋白胨 + 0.85 % 生理盐水。多用中和剂(polyvalent universal neutralizer,PUVN):称取吐温80 30.0 g,硫代硫酸钠5.0 g,L-组氨酸1.0 g,蛋白胨1.0 g,氯化钠8.5 g,卵磷脂14.3 g,充分溶解于去离子水中,并定容至1 000 mL;改良李氏肉汤吐温培养基(modified Letheen broth + Tween,MLBT),MLBT:MLB液体培养基 + 1 %吐温80 + 0.93 %卵磷脂;磷酸缓冲液(phosphate buffer saline,PBS):KH2PO4 1.36 g,Na2HPO4 2.84 g,去离子水1 000 mL使充分溶解。(干粉培养基均购自广东环凯生物技术有限公司,化学试剂购自广东化学试剂厂)。上述用具与试剂均灭菌后使用。

1.3 方法 1.3.1 离体实验模型测试洗手或洗手产品去除病毒效果参照ASTM E1174 -13[4]、ASTM E2011-13[5],结合病毒测试的特点,分析实验中可能对结果造成影响的因素,确定了实验的常规参数,并用“合适的”描述不确定参数,初步建立离体实验的实验流程:(1)无菌条件下打开仿真皮包装,参照成人手掌及指尖部分大小,将仿真皮剪成(8 × 10)cm大小,糙面向上备用;使用合适浓度的噬菌体悬液,取0.5 mL噬菌体悬液加到仿真皮表面,涂布棒涂抹均匀至仿真皮表面干燥。(2)风干后立即进行基线取样,测试仿真皮表面污染病毒存活的数量。(3)室温水进行洗涤(水温约在17 ℃~26 ℃左右),调节水流速至4 L/min;轻轻打湿染噬菌体的仿真皮,洗手产品为香皂时,使用香皂搓15 s,整个手掌部分搓洗起泡30 s,后流水冲洗30 s,洗手产品为洗手液时,称取0.45 g样品至仿真皮表面,搓洗30 s后流水冲洗30 s,对清水(即自来水)洗涤,则搓洗30 s,流水冲洗30 s;冲洗完毕,用无菌纸巾轻轻拍干仿真皮表面;选用合适的回收方法回收仿真皮表面的噬菌体,并进行梯度稀释,采用双层平板法进行噬菌体计数。(4)去除率计算 将计数到的噬菌斑换算为对数形式,按照下列公式计算去除率:Log10对数减少 = Log10基线恢复 – Log10洗后恢复。

1.3.2 洗手产品冲洗后回收及稀释液的选择对于不含杀菌剂的手卫生产品或清水,直接采用PBS缓冲液(pH = 7.2);对于含杀菌剂的手卫生产品(下文简称为洗手产品),选择PBS(pH = 7.2)、0.1 %蛋白胨生理盐水溶液、MLBT及PVUN 4种溶液,按照下列步骤,进行回收稀释液的选择。(1)根据设计的体外冲洗步骤,结合擦洗及冲洗的时间和水流速等,确定将饱和香皂水溶液和洗手液稀释2 000倍后分别作为香皂和洗手液的回收稀释液选择实验样品。(2)取1 mL噬菌体溶液[104~5 plaque forming unit(pfu)/mL]加到4 mL实验样品中,充分混匀。作用10 min后,分别采用上述的回收稀释液进行梯度稀释,并计算回收到的噬菌体的含量。(3)分析结果,并选择合适的回收稀释液。

1.3.3 病毒回收方式选择制备106 pfu/mL的噬菌体悬液,取0.5 mL噬菌体液加到仿真皮表面,涂布使分散均匀,风干。风干之后采用3种不同的洗出方式(手动剧烈摇动瓶子、摇床200 r/min剧烈振摇、均质器标准强度快速拍打)回收相同时间(2 min),测试回收率。共进行5次测试作为平行实验,确定合适的回收方式。

1.3.4 初始污染浓度选择按照洗手试验正常试验步骤,仅改变初始加样浓度(108、107、106、105 pfu/mL),测试香皂对噬菌体 φX174 的去除率。每个初始浓度做5个平行试验数据,分不同实验日期完成。对数据进行分析,确定合适的初始加样浓度。

1.3.5 实验方法确定及验证使用洗手液及清水洗手测试对 φX174的去除率,测试方法对不同产品的适用性;使用MS2、φ6噬菌体验证方法对不同病毒的适用性。

1.4 统计分析将噬菌体平板计数的结果转化为对数形式。用

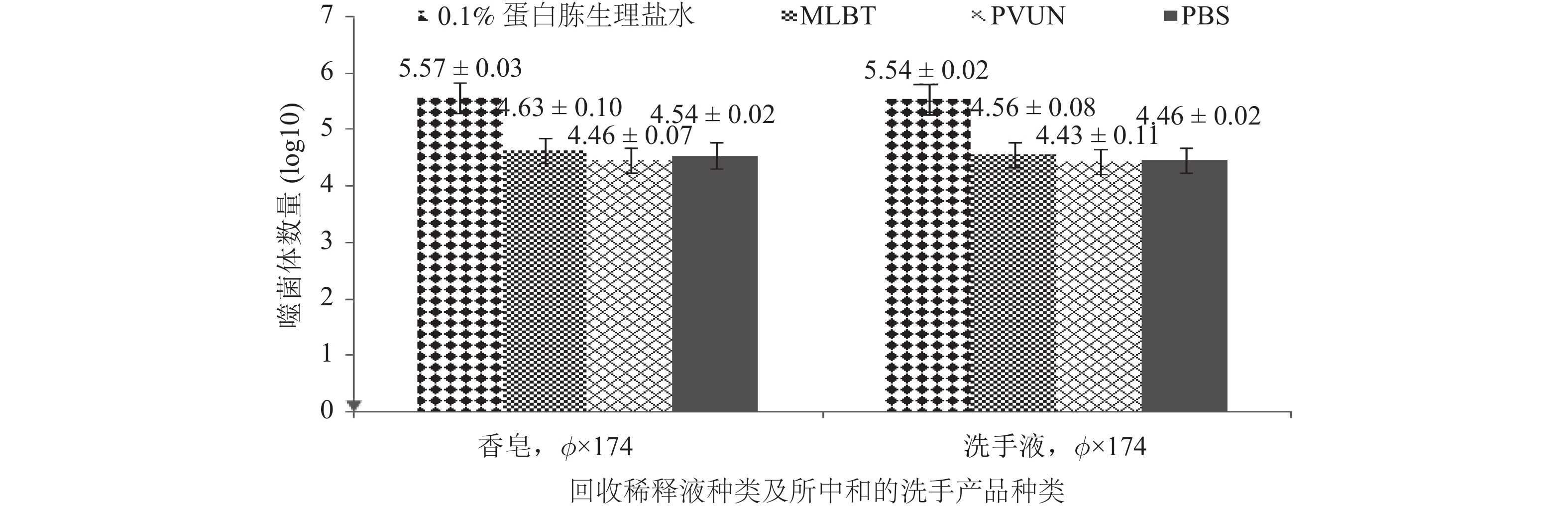

4种回收稀释液选择实验结果如图1。当使用0.1 %蛋白胨生理盐水作为回收稀释液时,噬菌体回收对数值分别为5.57和5.54(数值对应顺序为香皂、洗手液,下同),使用MLBT时,其回收对数值分别为4.63和4.56,PVUN时为4.46和4.43,当回收稀释液为PBS(pH = 7.2)时,其回收对数值则分别为4.54和4.46。除去0.1 %蛋白胨生理盐水,其他3种回收液的回收值均 < 5.00。

|

图 1 不同回收稀释液对噬菌体 φX174的中和回收效果 |

2.2 回收方式的选择(表2)

实验按照3种(A、B、C)不同的回收方式对相同加样量的仿真皮样品上的噬菌体进行回收。分别计算3种回收方式的回收值,每种回收方式各平行数据之间的全距和CV。由表2可知,均质器拍打回收时的CV最小,为0.74 %,其全距最窄(R = 0.10)。对3组回收所得数据进行单因素方差分析,其P0.05 = 0.72。

| 表 2 不同回收方式下回收得到的噬菌体数量及其稳定性 |

2.3 初始浓度的选择(表3)

| 表 3 不同初始加样浓度情况下洗手实验的效果及分析 |

在参与筛选试验中的4个初始加样浓度中,当加样量 < 10 6 pfu/mL时(样本C、D),基线恢复得到的噬菌斑数量在平皿上可以计数到的噬菌体对数值 < 4.00,不符合初始设计的实验浓度。对符合实验设计的A、B样品进行等方差双样本的 t检验,其P0.05 = 0.003。分别计算各初始加样浓度下5组平行实验的全距和CV,其中在108 pfu/mL时,CV最小,为2.85 %。

2.4 洗手产品及洗手对噬菌体的去除效果实验方法验证(表4)| 表 4 不同洗手产品对噬菌体 φX174及噬菌体MS2的去除效果 |

采用上述试验流程,评价使用不同洗手产品洗手时对噬菌体的去除效果(以Log10减少表示),评估方法的稳定性及适用性。结果显示,使用洗手液、香皂、清水分别对噬菌体 φX174、MS2及 φ6进行去除效果评价时,其CV(%)分别为1.56、2.85、10.55、9.24、13.27、5.32、5.00、5.00和8.00,CV均 < 15 %。

3 讨 论预防医学及流行病学研究表明,接触传播是病毒性疾病传播的重要方式,病毒可以通过手 – 人直接接触传播,也可以通过食物、水、排泄物、呕吐物或空气等介质传播。一旦病毒污染环境表面,或形成的污染物被人手触摸,即可形成再次播散,后经口、鼻或眼粘膜等对人体进行间接感染 [25 – 26]。环境表面或污染物表面的病毒粒子,由于水或有机质的存在,可以在很长时间内保持感染能力,甚至在人的手上也可以长时间保持侵染活性[27]。一项鼻病毒的研究显示,鼻病毒在人手上可以存活7 d甚至更长时间[28],研究中有一半的受试者触摸污染物后又触摸到了眼、鼻及口腔黏膜[29]。尽管不同研究人员采用的病毒种类、浓度、实验条件等有所不同,研究的病毒的存活能力也有差异,但即使是物体表面有少量的病毒传递到人体后,仍可保持感染力[30]。因此,作为一种经济、便捷、有效的手卫生的控制方式,洗手对于预防和控制病毒性疾病的流行传播具有重要的意义。

目前市场对具有去除病毒效果的洗手产品需求迫切,且许多产品也宣称其具有去除病毒的效果,但真正对其效果进行评价的标准方法仍非常有限。国内外现已发表的研究文献和正式发布的标准方法,主要是对手部常驻菌、暂居菌及常见病毒的去除效果的研究和评价[2 – 5]。这些程序方法均具有一定的局限性,特别是除病毒的试验研究,均采用的是动物病毒或人病毒作为试验毒株进行在体试验研究,在安全性、可操作性及实用性上都有很大的局限[6],且试验成本高、时间长、传染风险高。因此,使用替代病毒和体外试验模型具有十分显著的优势。以猪皮和人造仿真皮作为离体去除细菌试验模型的底物时,与在体皮肤试验的结果相近[31]。同时,噬菌体作为一种安全的微生物病毒,也逐渐作为替代病毒被用于传播规律的研究(表1)。因此,建立一个以噬菌体为测试病毒的体外试验方法是十分必要且可行的。

本研究设计模拟洗手的试验流程,先后确定了冲洗后回收及稀释液种类、初始加样浓度及回收方式并验证了方法的稳定性和适用性。结果显示,实验采用的4种回收稀释液中,使用0.1 % 蛋白胨生理盐水时,对噬菌体的回收效果最好,其他3种略差。其主要原因在于:一方面,当使用洗手产品完成洗手过程后,残留在仿真皮表面的杀菌物质含量已经非常少,中和剂的作用不明显,且采用PVUN或者MLBT作为中和剂时,比较容易产生气泡,对最终计数的准确性有一定影响;另一方面,少量存在的有机物,保护了噬菌体的活性。对3种不同回收方式在相同加样量的仿真皮样品上会受到的噬菌体进行单因素方差分析,其P0.05 > 0.05,表明3种回收方式之间没有显著差异;当使用均质器拍打时,其变异系数( CV = 0.74 %)最小,全距最窄(R = 0.10),表明使用均质器进行拍打,每次回收得到的回收数据最稳定。因此,在进行本方法时,可以根据实验室条件选用任意的回收方式,但为得到稳定的实验数据,建议使用均质器拍打的方式进行回收。初始加样浓度筛选中,首先根据设计需要,排除掉了低于107 pfu/mL的2个浓度。对符合设计要求的2个加样浓度进行等方差双样本t检验,其P0.05 < 0.01,表明2者的去除率有显著差异;对2种加样量的回收数据进行分析,发现在10 8 pfu/mL时,去除效率高,符合理想假设,同时重复实验的变异系数最小(CV = 2.85 %),表明数据最稳定,重复性好。因此,实验认为108 pfu/mL是比较合适的初始加样浓度。

使用洗手液、清水分别对噬菌体 φX174进行去除效果评价,其变异系数小于15 %,表明采用该方法适用于各种形态的洗手产品。使用MS2或 φ6作为污染病毒,也可以得到较为稳定的实验数据(CV < 15 %),表明该方法同样适用于其它的实验病毒。上述实验结果表明,方法的可重复性和适用性良好。

综上所述,作为一种安全、简便、省时、可操作性强、人员和设备要求低的实验流程,该方法具有较好的应用价值,有助于推动洗手产品除病毒效果评价标准化的进程。

| [1] | Tuladhar E, Hazeleger WC, Koopmans M, et al. Reducing viral contamination from finger pads: hand washing is more effective than alcohol-based hand disinfectants[J]. Journal of Hospital Infection, 2015, 90(3): 226–234. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.02.019 |

| [2] | American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM E2870-13, standard test method for evaluating relative effectiveness of antimicrobial handwashing formulations using the palmar surface and mechanical hand sampling[S]. United States: American Society for Testing and Materials International, 2013. |

| [3] | American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM E1838-10, standard test method for determining the virus-eliminating effectiveness of hygienic handwash and handrub agents using the fingerpads of adults[S]. United States: American Society for Testing and Materials International, 2010. |

| [4] | American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM E1174-13, standard test method for evaluation of the effectiveness of health care personnel handwash formulations[S]. United States: American Society for Testing and Materials International, 2013. |

| [5] | American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM E2011-13, standard test method for evaluation of hygienic handwash and handrub formulations for virus-eliminating activity using the entire hand[S]. United States: American Society for Testing and Materials International, 2013. |

| [6] | Rotter M, Sattar S, Dharan S, et al. Methods to evaluate the microbicidal activities of hand-rub and hand-wash agents[J]. Journal of Hospital Infection, 2009, 73(3): 191–199. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2009.06.024 |

| [7] | World Health Organization. Guidelines on hand hygiene in health care [S]. World Health Organization, 2009, Part 1: 3. |

| [8] | Adams MH. Bacteriophages[N]. Interscience Publishers INC, New York, 1959. |

| [9] | Tamimi AH, Carlino S, Edmonds S, et al. Impact of an alcohol-based hand sanitizer intervention on the spread of viruses in homes[J]. Food and Environmental Virology, 2014, 6(2): 140–144. DOI:10.1007/s12560-014-9141-9 |

| [10] | Casteel MJ, Schmidt CE, Sobsey MD. Chlorine disinfection of produce to inactivate hepatitis A virus and coliphage MS2[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2008, 125(3): 267–273. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.04.015 |

| [11] | Shirasaki N, Matsushita T, Matsui Y, et al. Investigation of enteric adenovirus and poliovirus removal by coagulation processes and suitability of bacteriophages MS2 and φX174 as surrogates for those viruses[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 563-564: 29–39. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.04.090 |

| [12] | Kosel J, Gutiérrez-Aguirre I, Rački N, et al. Efficient inactivation of MS-2 virus in water by hydrodynamic cavitation[J]. Water Research, 2017, 124: 465–471. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2017.07.077 |

| [13] | Elving J, Emmoth E, Albihn A, et al. Composting for avian influenza virus elimination[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 78(9): 3280–3285. DOI:10.1128/AEM.07947-11 |

| [14] | International Standards Organization. International Standards Organization 107050. Water quality-detection and enumeration of bacteriophages. Part 1[S]. Switzerland, 1995. |

| [15] | Turgeon N, Toulouse MJ, Martel B, et al. Comparison of five bacteriophages as models for viral aerosol studies[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(14): 4242–4250. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00767-14 |

| [16] | Rheinbaben FV, Schünemann S, Gross T, et al. Transmission of viruses via contact in a household setting: experiments using bacteriophage fX174 as a model virus[J]. Journal of Hospital Infection, 2000, 46(1): 61–66. DOI:10.1053/jhin.2000.0794 |

| [17] | Verreault D, Rousseau GM, Gendron L, et al. Comparison of polycarbonate and poly tetrafluoroethylene filters for sampling of airborne bacteriophages[J]. Aerosol Science and Technology, 2010, 44(3): 197–201. DOI:10.1080/02786820903518899 |

| [18] | American Society for Testing and Materials. F1671/F1671M, standard test method for resistance of materials used in protective clothing to penetration by blood-borne pathogens using Phi-X174 bacteriophage penetration as a test system[S]. United States: American Society for Testing and Materials International, 2013. |

| [19] | Wu B, Wang R, Fane AG. The roles of bacteriophages in membrane-based water and wastewater treatment processes: a review[J]. Water Research, 2017, 110: 120–132. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2016.12.004 |

| [20] | Vidaver AK, Koski RK, Van Etten JL. Bacteriophage Phi 6: a lipid-containing virus of Pseudomonas phaseolicola [J]. Journal of Virology, 1973, 11(5): 799–805. |

| [21] | Aranha-Creado H, Peterson J, Huang PY. Clearance of murine leukaemia virus from monoclonal antibody solution by a hydrophilic PVDF microporous membrane filter[J]. Biologicals, 1998, 26(2): 167–172. DOI:10.1006/biol.1998.0130 |

| [22] | Lytle CD, Tondreau SC, Truscott W, et al. Filtration sizes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and surrogate viruses used to test barrier materials[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1992, 58(2): 747–749. |

| [23] | Phillpotts RJ, Thomas RJ, Beedham RJ, et al. The Cystovirus, phi6 as a simulant for Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus[J]. Aerobiologia, 2010, 26(4): 301–309. DOI:10.1007/s10453-010-9166-y |

| [24] | Sassi HP, Ikner LA, Abd-Elmaksoud S, et al. Comparative survival of viruses during thermophilic and mesophilic anaerobic digestion[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 615: 15–19. |

| [25] | Otter JA, Donskey C, Yezli S, et al. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: the possible role of dry surface contamination[J]. Journal of Hospital Infection, 2016, 92(3): 235–250. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.027 |

| [26] | Sassi HP, Sifuentes LY, Koenig DW, et al. Control of the spread of viruses in a long-term care facility using hygiene protocols[J]. American Journal of Infection Control, 2015, 43(7): 702–706. DOI:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.03.012 |

| [27] | Oxford J, Berezin EN, Courvalin P, et al. The survival of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus on 4 household surfaces[J]. American Journal of Infection Control, 2014, 42(4): 423–425. DOI:10.1016/j.ajic.2013.10.016 |

| [28] | L'Huillier AG, Tapparel C, Turin L, et al. Survival of rhinoviruses on human fingers[J]. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 2015, 21(4): 381–385. DOI:10.1016/j.cmi.2014.12.002 |

| [29] | Jr GJ, Hendley JO. Transmission of experimental rhinovirus infection by contaminated surfaces[J]. American Journal of Epidemiology, 1982, 16(5): 828–833. |

| [30] | Thomas Y, Boquetesuter P, Koch D, et al. Survival of influenza virus on human fingers[J]. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 2013, 20(1): O58–O64. |

| [31] | 谢小保, 李彩玲, 李素娟, 等. 离体和在体消毒方法相关性的初步研究[J]. 中国卫生检验杂志, 2011, 21(8): 1942–1946. |

2019, Vol. 35

2019, Vol. 35