2. 山东第一医科大学(山东省医学科学院)附属省立医院, 山东 济南 250021

2. Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan 250021 China

先天性心脏病是心脏及大血管在胚胎发育期发育异常或形成障碍,或本应在出生后自动关闭的通道未闭合,少数类型可自然恢复,大多数需要及时行外科手术或介入诊疗[1]。介入治疗因其创伤小、恢复快、风险小、并发症少等优点,逐渐代替外科手术成为当前医治先心病的主要手段,但在先心病介入诊疗过程中,透视时间要长于普通X射线诊断,患者受到的辐射剂量往往也比较高[2-3]。儿童的组织对辐射的敏感性约比成人强2~10倍,更容易受到直接的组织损伤和诱发生物化学损伤[4-6],且儿童体型小、体重低、预期生存时间长,发生恶性肿瘤等随机性效应的风险更高[7-8],有研究表明10 岁以内儿童辐射风险增加更明显[9],在保证诊疗需求的前提下合理降低儿童的辐射剂量,是当前亟需解决的重要问题。

本研究回顾性分析了2021年6月—2022年9月期间,在济南市某三甲医院接受儿童先心病介入手术治疗的94例患者的个人资料和辐射剂量,并探讨了不同介入手术之间的差异性和影响剂量大小的相关因素,为评估儿童先心病介入手术所致的辐射剂量提供参考依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 临床材料纳入2021年6月—2022年9月在济南市某三甲医接受儿童先天性心脏病介入手术治疗的94例患儿,经胸片、彩色多普勒超声心动图等检查确诊为室间隔缺损(ventricular septal defect ,VSD)、动脉导管未闭(patent ductus arteriosus,PDA)、房间隔缺损(atrial septal defect,ASD)的患儿分别为48、29、17例,其中男41例,女53例。所有患儿均符合先天性心脏病经导管介入治疗的手术条件,自愿接受介入治疗手术且无禁忌证。

1.2 介入手术类型介入手术类型包括室间隔缺损(VSD)封堵术、动脉导管未闭(PDA)封堵术、房间隔缺损(ASD)封堵术。所有患儿仅接受上述先心病介入手术中的一种。

1.3 DSA设备所有手术采用数字减影血管造影机(digital subtraction angiography,DSA),设备型号为德国西门子Artis zee floor。

1.4 资料收集记录每例手术中患儿的年龄、性别、身高、体重、手术类型等基本资料,收集术后剂量报告,报告中的内容包括透视时间、剂量面积乘积(Air Kerma Area Product,KAP)、累积剂量(Cumulative Air Kerma,CAK)、曝光条件等。

1.5 统计分析采用 Microsoft Excel 整理归纳、SPSS 21.0.0.0统计软件进行统计分析。计数资料用例数、百分数表示,计量资料以M(P25,P75)表示。运用描述性统计、非参数Kruskal-Wallis H检验和多元线性回归分析等方法,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果 2.1 基本资料患者基本资料见表1。

|

|

表 1 患者基本资料 Table 1 Basic information of patients |

管电压(67.8~89.4 kV)、脉冲时间(3.1~13 ms)、帧速率(10~15 F/s)、铜过滤厚度(0~0.3 mm)、视野大小(20~25 cm)。透视时间、管电流、减影图像数、辐射剂量及非参数检验结果见表2。3组间的透视时间、减影图像数(CI)、CAK值、KAP值和KAP·kg−1存在统计学差异(P<0.05),管电流的差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。两两比较结果显示,VSD组透视时间、减影图像数、CAK值、KAP值、KAP·kg−1均显著高于PDA组和ASD组(P<0.05),PDA组减影图像数显著高于ASD组(P<0.05)。

|

|

表 2 不同先心病介入手术曝光参数及辐射剂量 Table 2 Exposure parameters and radiation dose of different interventional procedures for congenital heart disease |

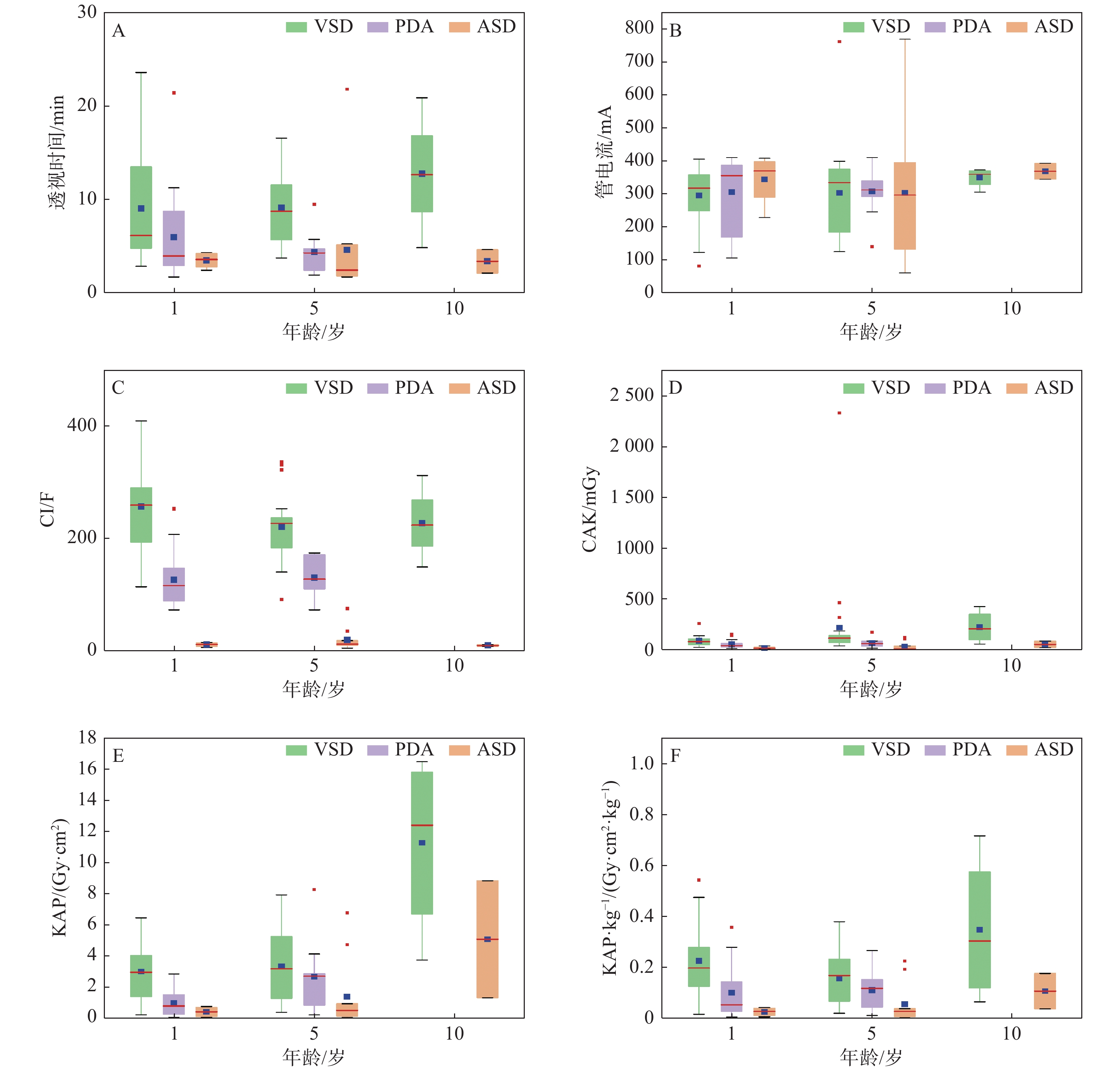

依据ICRP 135号报告[10]对94例数据进行了年龄分层(图1)。各手术透视时间、CI、CAK、KAP、KAP·kg−1的中位数在3个年龄组中呈现的趋势基本一致,1、5岁年龄组均为VSD组>PDA组>ASD组,10岁组均为VSD组>ASD组,说明透视时间、CI与辐射剂量具有相关性。各手术的KAP中位数均有随年龄的增大而上升的趋势,说明年龄可能是影响KAP值的相关因素。

|

图 1 1、5、10岁患者在不同先心病介入手术中的曝光参数及辐射剂量 Figure 1 Exposure parameters and radiation doses in patients aged 1, 5, and 10 years with different interventional procedures for congenital heart disease 注:A.透视时间(min);B.管电流(mA) C.CI(F);D.CAK(mGy);E.KAP(Gy·cm2);F.KAP·kg−1(Gy·cm2·kg−1)。 |

采用多元线性回归分析年龄、身高、体重、透视时间、管电流、减影图像数6种因素对KAP值的影响。从表3中可以看出,年龄(B=52.445,P<0.05)、体重(B=13.077,P<0.05)、透视时间(B=0.425,P<0.05)、管电流(B=0.872,P<0.05)、减影图像数(B=0.660,P<0.05)和KAP值具有相关性,即KAP值会随着年龄、体重、透视时间、管电流、减影图像数的增加而增大,身高和KAP值之间无相关性(P>0.05)。

|

|

表 3 影响KAP值的多元线性回归分析 Table 3 Multiple linear regression analysis of factors affecting KAP |

先天性心脏病是最常见的先天畸形,给社会和患者家庭带来沉重负担。介入治疗是当前治疗先心病的重要手段,但患者在接受介入诊疗时一般会受到较高的辐射剂量[11],有研究显示儿童先心病介入手术中患者的有效剂量约是常规X线检查的几十倍[12]。儿童的组织细胞比成年人对X射线的敏感性更高,更易诱发肿瘤等随机效应,尤其以10岁内患儿更加明显[9]。因此应当重视先心病介入手术对患儿造成的辐射剂量问题,尽可能控制并减少辐射暴露。

在本研究中,不同个体之间的曝光条件和辐射剂量存在较大差异。94例患者的透视时间范围为1.7~23.5 min,减影图像数范围为6~409 F,CAK值范围为2.1~2327.4 mGy,KAP值范围为0.068~16.45 Gy·cm2,KAP·kg−1范围为0.003~0.715 Gy·cm2·kg−1,其中各指标的最大值均来自VSD组。组间比较的结果显示,VSD组的CAK值和KAP值显著高于ASD组和PDA组,与相关研究结果相似[13-14]。除此之外,本研究还发现VSD组的透视时间、减影图像数、KAP·kg−1也显著高于PDA组和ASD组。在按年龄分组后,1、5岁患者的透视时间、CI、CAK,KAP、KAP·kg−1 几项指标均为VSD组>PDA组>ASD组,10岁患者均为VSD组>ASD组,这可能与手术的复杂性和术者的熟练程度有关。VSD封堵术相较于ASD封堵术和PDA封堵术更为复杂,轨道导丝通过缺损较困难,若封堵器放置后影响三尖瓣或主动脉瓣,则需要在透视条件下重新调整[13],对操作者的技术水平要求较高,且术中需要进行2次造影,这些因素可能会导致透视时间延长和辐射剂量增大。

影响辐射剂量的因素大致可分为以下3种:一是患者因素。患者的病变部位、介入手术类型、自身血管状态均会对患者的受照剂量产生影响。另外在本次研究中患者的年龄和体重与KAP值呈正相关性,这与既往研究一致[15-16]。二是术者因素,例如术者对手术的熟练程度、对辐射的防护意识。术者对手术的熟练度在一定程度上会对透视时间长短和减影图像数量产生影响,有研究表明降低透视时间和减影图像数可降低辐射剂量[16],本研究也得到了类似结果。目前我国尚未制定先心病介入治疗的诊断参考水平国家标准[17],国内针对先心病介入治疗一般更关注手术疗效及术后并发症,对术中的剂量控制和防护意识较为淡薄,需加强医护人员辐射安全知识培训,提升防护技能[18-19]。此外,术中是否对患者应用屏蔽防护装置也会影响辐射剂量,刘晓晗等[20]的研究中,在使用滤过板、三角巾等防护装置后,患者的受照剂量得到了显著降低。三是设备因素。本研究发现管电流对KAP有正向影响,说明在保证手术需求的前提下降低管电流能有效降低患儿辐射剂量。另外,在一些其他研究中[21-24],帧速率、患者与影像接收器的距离、介入系统的升级或设备的优化等也是辐射剂量的影响因素。

综上所述,加强术者的业务培训,提高术者的业务水平,应用合适的辐射防护装置,在保证手术安全性和有效性的前提下使用最优化的DSA参数,及时升级和优化DSA设备,对降低患儿所受辐射剂量具有重要意义。

| [1] |

刘伟宾, 马晓海, 吴文辉, 等. 先心病患者在介入诊疗中辐射剂量控制分析[J]. 介入放射学杂志, 2021, 30(8): 837-841. Liu WB, Ma XH, Wu WH, et al. Analysis of radiation dose control in patients with congenital heart disease during interventional procedure[J]. J Intervent Radiol, 2021, 30(8): 837-841. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1008-794X.2021.08.019 |

| [2] |

Lyons AB, Harvey VM, Gusev J. Fluoroscopy-induced chronic radiation dermatitis (FICRD) after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm endoleak repair[J]. JAAD Case Rep, 2015, 1(6): 403-405. DOI:10.1016/j.jdcr.2015.09.022 |

| [3] |

程景林, 万俊, 王爱玲. 介入诊疗对心血管病患者外周淋巴细胞dna的损伤[J]. 介入放射学杂志, 2012, 21(7): 551-553. Cheng JL, Wan J, Wang AL. Acute chromosomal DNA damage of human lymphocytes caused by radiation exposure produced in performing interventional cardiovascular procedures[J]. J Intervent Radiol, 2012, 21(7): 551-553. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1008-794X.2012.07.005 |

| [4] |

Walsh MA, Noga M, Rutledge J. Cumulative radiation exposure in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease[J]. Pediatr Cardiol, 2015, 36(2): 289-294. DOI:10.1007/s00246-014-0999-y |

| [5] |

Schueler BA, Julsrud PR, Gray JE, et al. Radiation exposure and efficacy of exposure-reduction techniques during cardiac catheterization in children[J]. Am J Roentgenol, 1994, 162(1): 173-177. DOI:10.2214/ajr.162.1.8273659 |

| [6] |

Andreassi MG, Ait-Ali L, Botto N, et al. Cardiac catheterization and long-term chromosomal damage in children with congenital heart disease[J]. Eur Heart J, 2006, 27(22): 2703-2708. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl014 |

| [7] |

白家瑢, 王凤, 吴琳, 等. 先天性心脏病患儿介入治疗的辐射剂量[J]. 中国介入心脏病学杂志, 2019, 27(8): 447-451. Bai JR, Wang F, Wu L, et al. Radiation dose in pediatric interventional therapy for congenital heart diseases[J]. Chin J Intervent Cardiol, 2019, 27(8): 447-451. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1004-8812.2019.08.005 |

| [8] |

王凤, 陆颖, 袁超, 等. 低剂量影像策略在儿童室上性心动过速射频消融术中的辐射防护作用分析[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2017, 55(4): 272-276. Wang F, Lu Y, Yuan C, et al. Evaluation of a low dose imaging protocol on radiation exposure reduction in pediatric supraventricular tachycardia ablation procedure[J]. Chin J Pediatr, 2017, 55(4): 272-276. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2017.04.008 |

| [9] |

Chodick G, Ronckers CM, Shalev V, et al. Excess lifetime cancer mortality risk attributable to radiation exposure from computed tomography examinations in children[J]. Israel Med Assoc J, 2007, 9(8): 584-587. |

| [10] |

Vañó E, Miller DL, Martin CJ, et al. ICRP publication 135: Diagnostic reference levels in medical imaging[J]. Ann ICRP, 2017, 46(1): 1-144. DOI:10.1177/0146645317717209 |

| [11] |

孔令海, 张良安, 姜恩海, 等. 心血管病介入操作时患者受照剂量估算[J]. 国际放射医学核医学杂志, 2010, 34(3): 183-185. Kong LH, Zhang LA, Jiang EH, et al. Estimating the radiation dose of patient in cardiovascular disease interventional procedures[J]. Int J Radiat Med Nucl Med, 2010, 34(3): 183-185. |

| [12] |

白家瑢, 吴琳. 儿童先天性心脏病介入治疗中的辐射防护[J]. 中华儿科杂志, 2017, 55(10): 796-799. Bai JR, Wu L. Radiation protection in pediatric interventional procedures of congenital heart diseases[J]. Chin J Pediatr, 2017, 55(10): 796-799. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2017.10.018 |

| [13] |

冯俊, 程景林, 郭杰, 等. 小儿先天性心脏病介入治疗中辐射剂量的评价[J]. 安徽医药, 2012, 16(2): 184-186. Feng J, Cheng JL, Guo J, et al. Radiation dosage accepted by children during interventional treatment for congenital heart disease[J]. Anhui Med Pharmaceut J, 2012, 16(2): 184-186. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1009-6469.2012.02.018 |

| [14] |

闵楠, 牛菲, 刘乾, 等. 50名CHD患儿的介入诊疗的参数和受照剂量调查[J]. 中国辐射卫生, 2019, 28(2): 152-154. Min N, Niu F, Liu Q, et al. The investigation on parameters and doses of CHD children during interventional diagnosis and treatment[J]. Chin J Radiol Health, 2019, 28(2): 152-154. DOI:10.13491/j.issn.1004-714X.2019.02.010 |

| [15] |

Cevallos PC, Armstrong AK, Glatz AC, et al. Radiation dose benchmarks in pediatric cardiac catheterization: A prospective multi-center C3PO-QI study[J]. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv, 2017, 90(2): 269-280. DOI:10.1002/ccd.26911 |

| [16] |

Mbewe J, Mjenxane T. Local diagnostic reference levels in diagnostic and therapeutic pediatric cardiology at a specialist pediatric hospital in South Africa[J]. Polish Journal of Medical Physics and Engineering, 2022, 28(4): 180-187. DOI:10.2478/pjmpe-2022-0021 |

| [17] |

王建利. 先天性心脏病患儿介入治疗过程所受辐射剂量及其影响因素分析[J]. 实用医学影像杂志, 2018, 19(6): 481-483. Wang JL. Analysis of radiation dose and its influencing factors on interventional treatment of congenital heart disease[J]. J Pract Med Imag, 2018, 19(6): 481-483. DOI:10.16106/j.cnki.cn14-1281/r.2018.06.006 |

| [18] |

薛茹, 鞠金欣, 陈尔东. 医疗照射防护中有关放射诊断的放射卫生标准现状分析[J]. 中国辐射卫生, 2019, 28(3): 262-266. Xue R, Ju JX, Chen ED. Status analysis of radiological health standards about medical radiation protection for radiological diagnosis[J]. Chin J Radiol Health, 2019, 28(3): 262-266. DOI:10.13491/j.issn.1004-714X.2019.03.012 |

| [19] |

丁宏梅, 李媛. 临床医护人员电离辐射安全和防护知识知晓率调查[J]. 中国辐射卫生, 2022, 31(5): 620-625. Ding HM, Li Y. Awareness of ionizing radiation safety and protection knowledge among clinical healthcare professionals[J]. Chin J Radiol Health, 2022, 31(5): 620-625. DOI:10.13491/j.issn.1004-714X.2022.05.019 |

| [20] |

刘晓晗, 王子军. 数字减影血管造影低剂量技术在儿童介入诊疗中的应用[J]. 中国医学装备, 2015, 12(4): 71-73. Liu XH, Wang ZJ. Low-dose technology in the diagnosis and treatment of children interventional applications[J]. China Med Equip, 2015, 12(4): 71-73. DOI:10.3969/J.ISSN.1672-8270.2015.04.023 |

| [21] |

Hirshfeld JW Jr, Balter S, Brinker JA, et al. ACCF/AHA/HRS/SCAI clinical competence statement on physician knowledge to optimize patient safety and image quality in fluoroscopically guided invasive cardiovascular procedures. A report of the American college of cardiology foundation/American heart association/American college of physicians task force on clinical competence and training[J]. J Am College Cardiol, 2004, 44(11): 2259-2282. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.014 |

| [22] |

Buytaert D, Eloot L, Mauti M, et al. Evaluation of patient and staff exposure with state of the art X-ray technology in cardiac catheterization: A randomized controlled trial[J]. J Interv Cardiol, 2018, 31(6): 807-814. DOI:10.1111/joic.12553 |

| [23] |

Covi SH, Whiteside W, Yu S, et al. Pulse fluoroscopy radiation reduction in a pediatric cardiac catheterization laboratory[J]. Congenit Heart Dis, 2015, 10(2): E43-E47. DOI:10.1111/chd.12197 |

| [24] |

Borik S, Devadas S, Mroczek D, et al. Achievable radiation reduction during pediatric cardiac catheterization: How low can we go?[J]. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv, 2015, 86(5): 841-848. DOI:10.1002/ccd.26024 |