Advancement in nanocarrier-mediated delivery of herbal bioactives: from bench to beside

Abstract

The resurgence of interest in traditional herbal remedies stems from an increasing appreciation for their complex phytochemical profiles and potential for synergistic therapeutic effects. However, the therapeutic potential of plant extracts is often limited by poor absorption and potential toxicity related to conventional delivery methods. This review explores the application of nanocarrier-mediated delivery systems, such as nanoparticles (NPs), liposomes, and nanoemulsions, to address these challenges. These biocompatible carriers offer enhanced stability and targeted delivery of herbal compounds, improving their efficacy and reducing unwanted side effects. By enabling precise distribution, nanotechnology optimizes the potency of herbal medicine across diverse applications, including regenerative medicine, wound healing, anticancer, and infection treatment. This review provides a systematic description of successful applications of nano-delivery technologies, nanoparticles, liposomes, nanoemulsions, and hybrid carriers, for the targeted delivery of some well-characterized herbal bioactives (curcumin, allicin, berberine, resveratrol etc.) and the enhanced therapeutic performance of herbal bioactives across a variety of preclinical models.Graphical Abstract

Keywords

Nano-delivery systems Herbal compounds Wound healing Tissue engineering Bioavailability1 Introduction

Medical remedies with botanical components have been used for more than five thousand years. Observations of animals consuming specific plants while sick most certainly inspired this behavior [1–4]. Although synthetic treatments accompany a wide spectrum of negative side effects, their creation helped mankind to evolve [5]. From somewhat minor issues like headaches or dizziness to more severe repercussions like cancer, cardiac arrest, or even death, these can range from rather minor worries [6]. Given this, traditional medicine has seen a comeback in its search for safer substitutes based on the great knowledge of herbal medicine gathered over years [7]. Many times seen as natural and risk-free options are herbal treatments [8]. Problems not immediately endangering a person's life are being treated with herbal therapy nowadays [9]. Among these ailments in men and women include cardiovascular disease, inflammation, depression, and problems of the reproductive system. Their potential usefulness, however, beyond the therapy and prevention of such diseases; herbal chemicals have showed promise as antibacterial agents as well as in the regeneration of tissue and the healing of wounds [10–12].

However, the therapeutic potential of plant extracts is often severely limited by significant pharmacokinetic challenges associated with conventional dosage forms like oral tablets and decoctions. These limitations are not merely theoretical but are quantifiably stark. For instance, regarding poor absorption and low bioavailability of curcumin, it should be noted that it is infamous for its extremely low oral bioavailability, often cited as less than 1% due to poor absorption, rapid metabolism, and systemic elimination [13, 14]. Similarly, the oral bioavailability of resveratrol is considerably less than 1% [15], and that of free genistein is 6.8% [16]. Decoctions, while traditional, suffer from inconsistent compound extraction, degradation of thermolabile compounds, and similarly poor gastrointestinal absorption.

Hence, the high doses required to overcome poor bioavailability often lead to unwanted side effects and organ toxicity. For example, high doses of free curcumin have been associated with hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity in preclinical models [17–19], while high concentrations of garlic-derived allicin can cause erythrocyte hemolysis and gastrointestinal irritation [20, 21]. Nanocarrier-mediated delivery systems directly address these quantified limitations, offering a demonstrable and superior alternative.

Moreover, nano-encapsulation drastically improves the absorption and bioavailability of herbal bioactives. For example, curcumin-loaded liposomes have shown a ninefold increase in oral bioavailability compared to curcumin suspended in water [22]. Piperine-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) demonstrated a 2.5-fold increase in bioavailability over a piperine solution [23]. A resveratrol-loaded nanoemulsion achieved an 3.2-fold higher relative bioavailability compared to a unformulated resveratrol suspension [24].

Additionally, by improving solubility and enabling targeted delivery, nano-systems allow for a lower effective dose, thereby reducing systemic toxicity. Berberine-loaded nanoparticles have been shown to significantly reduce cardiac and hepatic toxicity markers in animal models compared to free berberine at an equivalent dose [25, 26]. Furthermore, functionalized nanocarriers can facilitate active targeting, minimize off-site effects and enhance accumulation at the disease site (e.g., tumors, inflamed tissues) [27]. Furthermore, nano-encapsulation protects sensitive compounds from degradation in the harsh gastrointestinal environment [28] and enables controlled, sustained release, maintaining therapeutic drug levels for prolonged periods and improving patient compliance [29].

Concerns regarding the development of antibiotic resistance have focused attention on the direction toward natural drugs as replacements for manufactured antibiotics. Especially for disorders brought on by strains resistant to antibiotics, the research by Enioutina [30] emphasizes the effectiveness of molecules originating from plants in treating a spectrum of ailments. A lot of research has indicated that traditional treatments such garlic, honey, ginger, turmeric, and oregano have antibacterial properties.

In his research, Bussmann [31] have discovered that several plant species used in folk medicine for disease management actually exhibit antibacterial properties. Albaridi [32] highlights the usefulness of honey in combating bacteria. It has been stressed by Tayel [33] and Combarros-Fuertes [34] that culinary botanicals like oregano demonstrate efficacy against antibiotic-resistant bacteria and foodborne pathogens. Chemicals that are generated from medicinal herbs and nutritious plants have shown a great deal of promise in the management and prevention of cancer. The reason for this can be ascribed to the several pharmacological properties that they possess, which include anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative, and antioxidant properties [35, 36]. Strong anticancer properties have been shown for many herbal constituents including turmeric, resveratrol, genistein, and others. these elements stop the spread of cancer cells, cause programmed cell death, and slow down tumor growth [37–39].

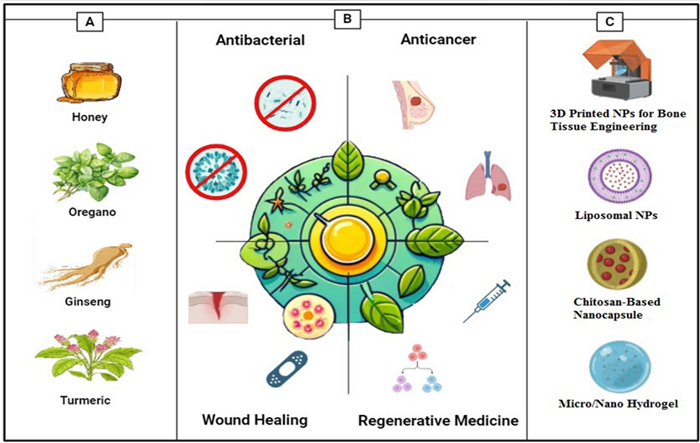

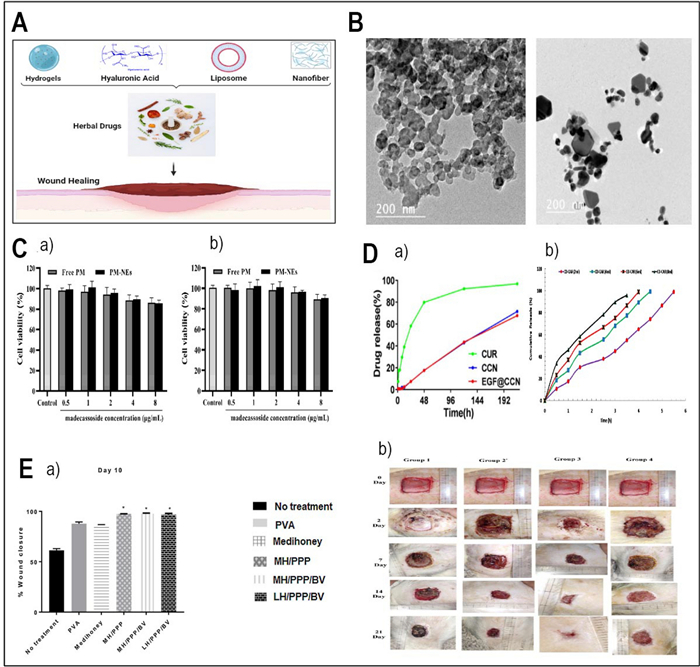

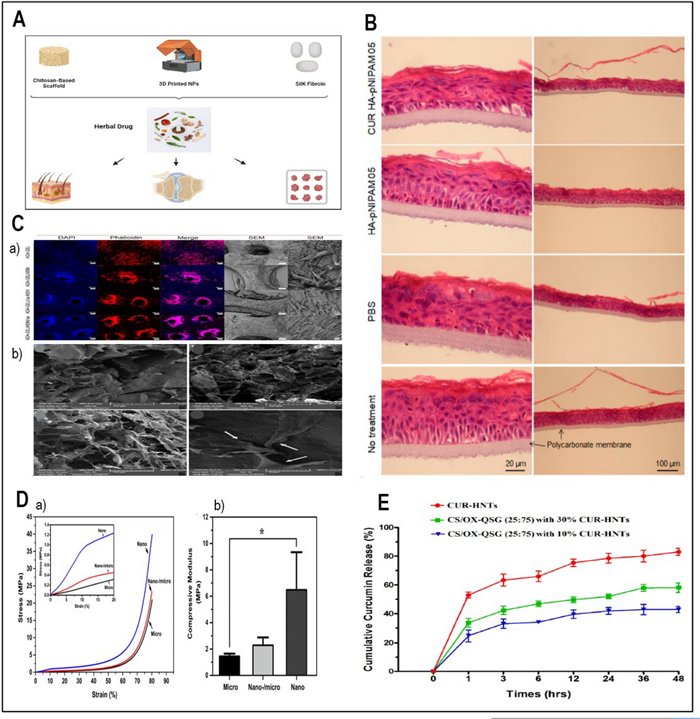

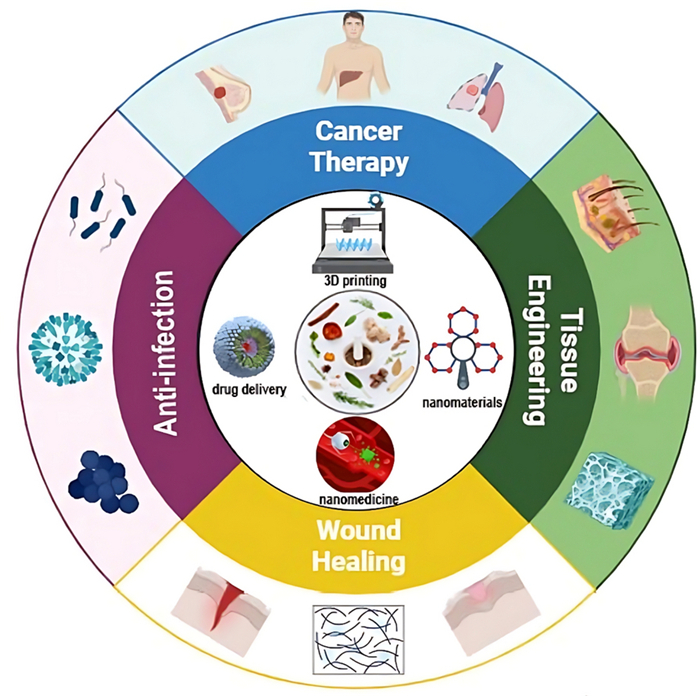

When it comes to medical therapy, wound healing is of the utmost importance, not only for the purpose of physical recovery but also for the purpose of psychological well-being [40, 41]. It is essential to provide appropriate wound care in order to avoid problems such as infections, deformed scars, and prolonged hospitalization from occurring [42]. Phenolic compounds, alkaloids, saponins, and flavonoids among the drugs demonstrated to boost collagen generation also cell proliferation and angiogenesis [43]. Especially remarkable is the evidence showing Allium sativum, Aloe vera (AV), Centella asiatica, and Hippophae rhamnoides greatly increases burn injury repair [44]. It has been demonstrated that herbal medicines that are used topically have the potential to be effective in treating burn wounds; however, additional research is required to evaluate the possibility of harmful consequences [45]. Moreover, herbal compounds have demonstrated potential in the field of tissue engineering (TE) and regeneration. Li's study found that polysaccharides produced from Chinese medicinal herbs help wounds heal and tissue damage be repaired [46]. It is commonly accepted that Chinese herbal medicines have the potential to promote adult stem cells in the process of tissue regeneration [47]. There is considerable research being undertaken on the potential applications of plant-derived biomaterials for tissue engineering [48]. Apart from motivating bone regeneration, phytochemical compounds including flavonoids, tannins, and polyphenols can be integrated into nanostructured scaffolds with the purpose of bone tissue engineering [49]. On the other hand, poor digestion and absorption lowers the efficacy of herbal remedies by insufficient active components reaching their intended purpose. Moreover, at appropriate dosages, herbs could be allergenic or poisonous, thereby impairing organs or causing nausea or vomiting [50, 51]. Bettering delivery methods will help to make herbal medicines safe and efficient for life-threatening diseases. Using nanodelivery technologies more focused and less side effects treatment solutions are accessible [52]. NPs based on proteins, lipids, or polysaccharides can show antimicrobial effect; regardless of their basis [53]. This is accomplished by creating osmotic stress in microbial cells, which increase membrane permeability [51]. Including NPs into various carriers, including hydrogels, increases their adhesion to the surfaces of tissues, so enabling highly concentrated treatment to be more realistic [54, 55]. While albumin-based nanocarriers enhance drug absorption in the body due to their widespread presence in humans and excellent biocompatibility, cellulose-based NPs improve the morphology of delivery vesicles and enhance their high cytocompatibility [56, 57]. It is possible to preserve herbal compounds against degradation using nano-delivery carriers such as nanoemulsions and liposomes, which also ensure great bioavailability and biocompatibility [58]. Figure 1 offers a schematic representation of the report's content. Panel A illustrates commonly used plants and natural compounds with bioactive properties. Panel B outlines the main applications, spanning antibacterial, anticancer, wound healing, and regenerative medicine. Panel C highlights the main delivery systems employed in herbal medicine research.

Overall view of this report. A The commonly used plants and natural compounds and their bioactive compound [Honey–Turmeric–Ginseng–Oregano] B Main applications [Antibacterial–anticancer–wound healing–regenerative medicine] C Main delivery systems

The aim of this review is to thoroughly examine the characteristics of active substances derived from plants and their prospective uses in treating human ailments, focusing specifically on their antibacterial effect, anticancer effect, wound healing properties, and their role in tissue engineering. This work further explores the application of nano-carriers, including nanoparticles, liposomes, and nanoemulsions, to enhance the delivery efficiency of herbal medicines. The emergence of groundbreaking developments in herbal medicine has facilitated the creation of safer and more efficacious therapies for numerous ailments. Through a rigorous analysis of these advancements, this review seeks to elucidate their transformative potential for medical care.

2 Antibacterial applications

The emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has motivated study on innovative approaches to fight bacterial diseases. Including herbal components into nanodrug delivery systems helps fight antibacterial agents holistically and ecologically friendly [59]. By increasing drug absorption and lowering therapy and side effect resistance, stimulus-responsive drug delivery and therapeutic nanoparticles can help to improve these systems [60]. In these systems, nanocarriers can improve the stability, precise transportation, and bioavailability of herbal substances [61]. Furthermore, studies have shown that, particularly in terms of targeted delivery, environmentally sensitive transportation, and combinatorial administration, nanoparticle drug delivery methods can increase the therapeutic efficacy of present antibiotics [62].

Hence, in the current section, we selected herbal compounds based on certain scientific and translational criteria. We selected evidence-based natural products like allicin, honey products, gingerol, curcumin, and carvacrol, generally recognized for effectiveness against a variety of microbial species supported by pharmacological studies [63, 64]. These bioactives have been incorporated in different types of nano-delivery systems and researched both in vitro and in vivo, resulting in a good representation of compounds for demonstrations of enhancing antimicrobial effects through nanocarrier-mediated techniques [65]. The selections also provide some structural diversity within specific phytochemical classes, which allows for discussion on how the delivery systems may differentiate chemical properties.

This section explores the potential of herbal compounds wide range of phytochemical classes (i.e., polyphenol, flavonoid, alkaloid, organosulfur compounds, terpenoids) as antibacterial agents within nanodrug delivery systems to revolutionize infection treatment.

2.1 Antimicrobial herbal compounds

2.1.1 Garlic

Garlic, formally known as Allium sativum Linn, has been valued for millennia for its remarkable medicinal properties including great antibacterial action [51]. Key in garlic's antibacterial action is allicin (AC), a bioactive molecule first discovered in 1944 by Cavallito and Bailey [66].

Against both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, garlic-derived AC shows a broad-ranging antibiotic arsenal [67]. Moreover, AC has showed antiviral and antifungal action against Candida albicans as well as antiparasitic properties against human intestinal protozoan parasites like Giardia lamblia and Entamoeba histolytica [67]. The importance of allicin in the antibacterial properties of garlic cannot be overstated. Indeed, garlic's antibacterial effects are lowered in the absence of AC or when alliinase, the enzyme in charge of allicin synthesis, is suppressed [68, 69]. Allicin's inhibitory effects on bacterial growth are comparable, if not better than several conventional antibiotic such as penicillin, tetracycline [70], and kanamycin [71, 72]. Especially, allicin's inhibitory properties cover a broad spectrum of microorganisms including bacteria, yeasts, fungus, and parasites [73, 74]. AC's multifarious and strong antimicrobial action makes it a desirable choice for nano-delivery systems to improve antimicrobial efficacy. Hasemy and coworkers used chitosan (CS)-lecithin nanoparticles modified with polyethylene glycol (PEG) and folic acid (FA) to deliver AC to colon cancer cells. Their study revealed that treatment with these nanoparticles reduced the viability of colon cancer cells. Also, in this study the human foreskin fibroblast was used as normal cells [75]. Allicin makes quite flexible use of its antimicrobial qualities. It can therefore affect the vital bacterial activities, where it reduces previously present walls and hinders cell wall formation. Moreover, it disturbs metabolism in bacteria and inhibits ribosome and enzyme activities, therefore upsetting protein synthesis and DNA replication. Especially, allicin's mode of action has led to the hypothesis that establishing resistance against it may be notably 1000-fold more difficult compared to beta-lactam antibiotics [76]. Studies have found that AC mostly targets RNA synthesis and somewhat reduces DNA and protein synthesis. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by this complex interference with microbial operations finally cause damage to DNA and proteins and culminate in microbial cell death [51].

2.1.2 Honey

The bees feed on flower nectar or blossoms that can later on is made into honey, which contains water, and a high number of sugars, such as glucose or fructose (~ 80% of its weight), however, it also has present compounds that can help treat bacterial infection. It contains vitamins, amino acids, enzymes, and a few vital minerals, but the main antibacterial component of the honey is hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and bee defensin-1. The composition of the honey's active compounds varies, depending on the plant and its part it has been collected from. For example, pure honey will have different antimicrobial properties, compared to multifloral honey [77]. Additionally, its high osmolarity and acidic pH create a mixture that has been used to treat bacterial infections [78]. H2O2 is produced through the oxidation of glucose, which is catalysed with glucose oxidase from bees, which is damaging to the bacterial cells by oxidation of the membrane and genetic material, and together with acidic pH, it prevents bacterial growth. This substance is widely used for disinfection purposes, not only at home but also in high concentrations (0.8-8M) can be used in medical settings (Stan et al., 2021). H2O2 has been proven to work against a few of the most common bacterial genera and their species, such as Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Bacillus spp., and more medically significant microbes. Furthermore, some types of honey contain methylglyoxal (MGO), which reduces the motility of some bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, through deflagellation, however it can also disrupt fimbriae in other bacteria species [79]. MGO was reported to successfully retard the expansion of various bacteria, both, gram-positive and negative, by reducing its adhering capabilities through alternation of their structure [80, 81]. Moreover, in another study, researchers assessed the antibacterial effects of Black Forest honeydew and manuka honey UMF 20 + against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus epidermidis, identifying inhibitory activity at 10–30 v/v% concentrations and higher gluconic acid content in manuka honey. Manuka honey was incorporated into polycaprolactone nanofiber scaffolds via pressurized gyration, producing fibres averaging 437–815 nm. These scaffolds exhibited over 90% bacterial reduction against S. epidermidis, demonstrating strong antibacterial efficacy. The findings suggest that honey-based composite nanofibers have significant potential as natural therapeutic agents, particularly in wound healing [82].

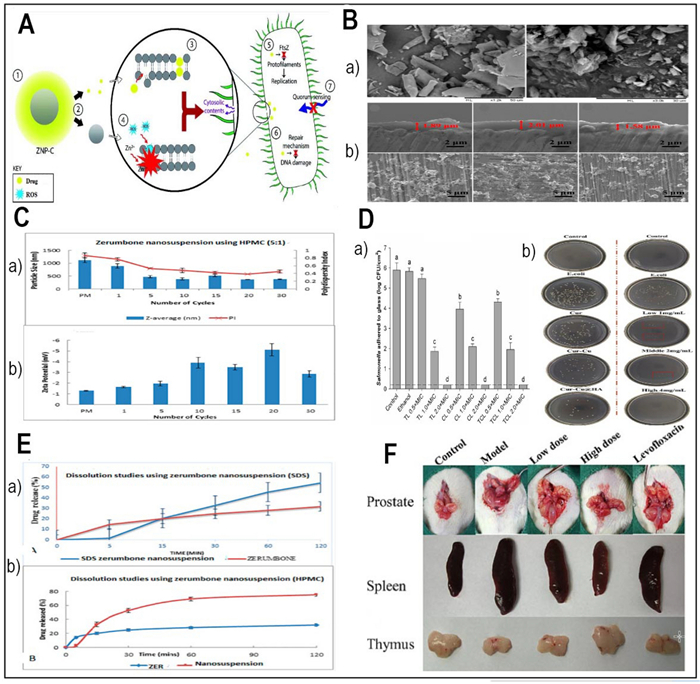

2.1.3 Ginger

Renowned for its many culinary and medicinal uses, ginger has a strong toolkit of antibacterial properties awaiting for nano-delivery systems (NDS). The bioactive chemical gingerol, which has great potential to fight infections especially in the oral cavity, is central in ginger's antibacterial effectiveness. The antibacterial mechanism of gingerol goes beyond accepted wisdom. Crucially important bacterial activities including adhesion, biofilm development, and quorum sensing—all of which contribute significantly to bacterial virulence—are stopped here. By upsetting these systems, gingerol shows promise as a creative antibacterial agent [83]. Furthermore, zerumbone, a less well-known component of ginger originally taken from wild ginger, shows a broad spectrum of therapeutic effects including anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiplatelet, antifungal, cytotoxic, and chemopreventive qualities [84]. However, zerumbone has always struggled with low water solubility, poor absorption, limited bioavailability, and difficulties getting the molecule to target tissues. The relevance of zerumbone has changed with the invention of nano-delivery techniques. Several investigations including those by Foong et al. and Md et al. have showed notable increases in the oral bioavailability and medicinal efficacy of zerumbone by means of NDS [85, 86] (Table 1). Md and colleagues developed a nanosuspension form of zerumbone in 2018 in order to boost solubility of it. In high-pressure homogenizing process, stabilizers were sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (HPMC).. Aggregation was absent in the zerumbone nanosuspensions stabilized by SDS presumably because of their strong zeta potential. Still, while looking at zerumbone nanosuspensions stabilized by HPMC, they discovered aggregated crystals most likely from low zeta potential. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images revealed particle agglomeration in both nanosuspension formulations resulting from water removal [86]. Emphasized in Fig. 2C, notable variations in the mean particle size and zeta potential of zerumbone nanosuspensions stabilized by SDS and HPMC showed themselves. Specifically, the mean particle size of the nanosuspension stabilized by SDS was 211 ± 27 nm and the zeta potential was about − 30.9 mV, whereas those stabilized by HPMC showed a mean particle size of almost 400 nm and a zeta potential of −3.37 mV. As shown in Fig. 2E, the dissolving properties of the untreated zerumbone were evaluated against those of the zerumbone nanosuspensions produced with SDS or HPMC stabilizers. Using SDS, the drug release from nanosuspensions was much higher than that of its equivalent (54.6% ± 7.3 vs. 31.9% ± 1.2). Comparatively to the crude zerumbone (75% ± 2.2 vs. 31.9% ± 1.2), the nanosuspensions of zerumbone, generated using HPMC, showed a clearly higher drug release percentage. The results show that nanosizing has enhanced zerumbone's solubility properties [86]. These difficulties of solubility, absorption, and targeted distribution have been essentially overcome by encapsulating zerumbone into nano-carriers, therefore opening new options for the use of ginger's antibacterial treasure store in the fight against microbial diseases.

Summary of studies in the existing literature utilizing nano-delivery systems for herbal compounds for antibacterial application

A The synergistic impact of the nanocarrier-drug combination on bacteria (Redesigned from reference [89] with permission). B SEM images of freeze-dried nanosuspensions containing SDS-zerumbone (Left) HPMC-zerumbone (Right) (Redesigned from reference [86] with permission). C The particle size and size distribution (measured as polydispersity index (PI) (a) and the zeta potential (b) of zerumbone nanosuspensions stabilized by HPMC decrease with increasing homogenization cycles (Redesigned from reference [86] with permission). D Effects of encapsulated antimicrobials, after a 1-min contact with Salmonella adhered to glass surface (a) (Redesigned from reference [95] with permission), The plate colony images of ALL@CS incubating with E. coli for about 4 h (b) (Redesigned from reference [101] with permission). E The dissolution profiles of (a) a freeze-dried nanosuspension stabilized by SDS and (b) a freeze-dried nanosuspension stabilized by HPMC were evaluated in a phosphate buffer solution at pH 7.4 and a temperature of 37 ℃ [86]. F The therapeutic efficacy of Cur-Cu@HA for prostatitis in rats. Images of the prostate, spleen, and thymus in various categories.(Redesigned from reference [101] with permission). (p-value = p, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001)

2.1.4 Turmeric

Renowned for both its vivid colour and many medical benefits, turmeric contains curcumin (Cur), a naturally occurring polyphenol antioxidant with a β-diketone [87]. With great ramifications for antibacterial treatment, curcumin's several antibacterial processes have attracted much study attention. Antimicrobial repertory of curcumin spans several groups of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungus, and parasites [88]. Its potency results from its capacity to alter gene expression, affect energy metabolism, and damage bacterial membranes. Though it has great potential, curcumin struggles with low stability, high metabolism, poor water solubility, and quick elimination. Researchers have developed several nano-delivery systems aiming at curcumin's solubility, targeting, and antibacterial action to overcome these challenges. While zinc oxide nanoparticles can increase its antibacterial activity [89], liposome nanocarriers can improve curcumin's transdermal distribution and sustained release [88] (Table 1). Recent research [89] has revealed a new delivery method, Cur-Cu@Hyaluronic acid (HA), which mixes curcumin with copper ions and hyaluronic acid, efficiently treats bacterial prostatitis, a painful and incapacitating illness brought on by an E. coli infection. These findings highlight the significant possibilities of curcumin-based nano-delivery technologies for the fight against bacterial diseases.

2.1.5 Oregano

Popular for its aromatic essential oils, oregano has strong antiseptic and antibacterial qualities [90]. Among its array of bioactive chemicals, two very well-known ingredients—carvacrol and thymol—have attracted a lot of interest for their antibacterial properties and several modes of action. A main component of oregano oil, carvacrol targets bacterial cell walls and membranes to mostly show antibiotic activities [91, 92]. It compromises the integrity of the outer and inner membranes, therefore lowering the oxidative stress tolerance in bacteria and compromising enzyme activity. Furthermore, carvacrol positions itself within lipid chains by modifying the flexibility and penetrability of the cell membrane, therefore proving its efficiency. This impairment of cell homeostasis causes a drop in membrane potential and intracellular pH. Moreover, phytochemical substances including carveol, carvone, citronellol, and citronellal can elicit cell lysis by delocalizing electrons and generating the continuous release of K+ ions outside the membrane, therefore resulting in bacterial cell death [93].

Another well-known component of oregano, thymol shows antibacterial action by encapsulating in different nano-sized delivery vehicles [94] (Table 1). In a study undertaken by Caroline Heckler and colleagues in 2020, the antimicrobial activities of nanoliposome-encapsulated thymol, carvacrol, and a combination of thymol/carvacrol (1:1) were evaluated against a pool of Salmonella bacteria. Promising features of the encapsulated antimicrobial agents were excellent encapsulation efficiencies (~ 99%) and nanoliposomes with sizes between 230 and 270 nm. For both free and encapsulated antibiotics, Fig. 2D part a shows the notable declines in adherent Salmonella populations at the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). While ethanol indicates the surviving Salmonella bacteria following one minute of contact to a 20% ethanol solution, control is the population of Salmonella bacteria adhered to the glass surface. Every bar in the figures shows the three separate, unconnected standard deviation of three different experiments. Different letters stand for statistically significant variations (p < 0.05). The dotted line shows 0.2 log of colony-forming units per square centimeter, the detection limit of this technique. As shown in Fig. 2D part a, encapsulated antibiotics totally eradicated adhering Salmonella at a concentration 2.0 times the MIC. With no clear variation across the liposomal preparations, MIC showed considerable declines (3.79–4.03 log CFU/cm2; p < 0.05) [95].

Research have effectively captured important phytochemicals, including thymol, in liposomes showing synergistic antibacterial action against several bacteria [96]. Characteristic of effective trapping of active chemicals, the liposomal systems had tiny diameters of roughly 144 nm and negative zeta potentials of roughly − 30 mV. Moreover, great encapsulation efficiency and sustained release characteristics have been described by means of the encapsulation of thymol inside cyclodextrins and its derivatives [93]. Concurrent with this development of corona-modified NDS using bovine serum albumin (BSA) on a CS core, carvacrol has found its niche in nano-delivery systems (Table 1) [97]. These NDS provide a forum for the continuous release of the respected natural antibacterial agent carvacrol into the intestine. With exact control and targeted distribution, this creative strategy provides means to maximize the antibacterial power of carvacrol. A notable study investigated the antibacterial efficacy of previously synthesized and characterized chitosan nanoparticles loaded with carvacrol, assessing their synergistic effects with Topoisomerase Ⅱ inhibitors—ciprofloxacin and doxorubicin—against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella typhi. The findings demonstrated that combining carvacrol nanoparticles with these antibiotics significantly lowered the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) compared to the drugs alone. Specifically, ciprofloxacin exhibited MIC50 values of 35.8 µg/mL, 48.74 µg/mL, and 35.57 µg/mL, while doxorubicin showed MIC50 values of 20.79 µg/mL, 34.35 µg/mL, and 25.32 µg/mL against S. aureus, E. coli, and S. typhi, respectively, highlighting enhanced antibacterial activity through nanoparticle-mediated synergy. This study revealed that herbal loaded nanoparticles can also, help as a subsidiary treatment for traditional antibiotics [98].

2.2 Delivery of antibacterial herbal compounds

Because they could be efficient substitutes or complements for conventional antibiotic treatment, antibacterial plant substances have attracted major interest in recent years. Conventional approaches of delivering herbal medications, such oral supplements, have restrictions in terms of attaining localized and effective distribution to target sites [80]. As suggested by Stan et al., a potential method to get above these constraints is the exact delivery of bioactive substances made possible by nanocarriers. The several nanoparticle formulations utilized for the transport of antibacterial herbal components are covered in this part together with their ingredients and possible uses. Figure 2A shows how the nanocarrier-drug combination acts in concert to kill bacteria.

2.2.1 Nanoparticulate systems for antibacterial drug delivery

Nanoparticulate systems offer a versatile framework for the delivery of herbal medications having antibacterial action. Various materials can be used in engineering these nanocarriers to satisfy particular therapeutic goals. Key characteristics of nanoparticles, including their form, size, and surface charge, can be precisely modified by changing material types, contents, and manufacturing procedures, thus optimizing drug release kinetics and obtaining exact organ or cell targeting [111]. For example, garlic's phytoconstituents, among others, have shown promise in antimicrobial uses; issues with solubility, stability, and bioavailability have hampered their practical relevance. By means of nanocarriers like NPs, liposomes, carbon nanotubes, quantum dots, and hydrogels, nanotechnology has become a way to solve these problems (Prajapati et al., 2021). These nanocarriers not only increase solubility and stability but also target capacity of phytoconstituents, hence enhancing therapeutic results and lowering the needed dosage. Typically researched for antibiotic treatments are inorganic metal nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, lipid-based nanoparticles, micellar nanoparticles, silica nanoparticles, and cell membrane-coated nanoparticles [112, 113].

2.2.1.1 Chitosan

Considered a good source of pH-responsive nanocapsules, cationic natural polysaccharide chitosan has intrinsic antibacterial effect. Protonation and deprotonation of the amino groups generates this in chitosan. Hao et al., (2022) investigated the prospect of chitosan-based nanocapsules as carriers for antibacterial herbal components, therefore offering a twofold advantage of natural antibacterial action and regulated drug release. Figure 2D part b shows the effectiveness of the antibacterial properties against E. coli varies depending on the pH settings. The data demonstrate that the colonies exhibit a greater abundance when exposed to solutions with pH levels of 8 and 7, as opposed to solutions with pH levels of 6 and 5. Furthermore, the number of colonies is at its minimum when the solid medium is incubated in pH 5 phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) settings. The results indicate that the acid-allicin@chitosan (ALL@CS) nanocapsules demonstrate enhanced antibacterial efficacy in acidic conditions [99] (Table 1).

2.2.1.2 Hyaluronic acid

Because of its main sodium salt form, hyaluronic acid (HA), a big glycosaminoglycan molecule found abundantly in the human body, offers excellent biocompatibility and high water-solubility [114]. As the CD44 receptor, which shows large expression levels in inflammatory areas and participates in inflammation, hyaluronic acid is the ideal ligand for focused medication distribution [115, 116]. Hyaluronic acid-based nanocarriers have showed great promise in delivering antibacterial herbal components to particular locations of illness according to many research [117, 118]. This method minimizes off-target effects, hence improving drug accumulation at the intended site [101] (Table 1). In 2023, Gao and colleagues developed a targeted drug delivery system by grafting a curcumin-copper complex onto hyaluronic acid (HA). Targeting ability, antibacterial activity, and carrier solubility were among the aspects where the planned delivery system most certainly enhanced. Grafting hyaluronic acid enhanced water solubility and gave the carrier amazing CD44 receptor targeting ability. Additionally, the complexation of copper ions with the carrier significantly improved its antibacterial properties, particularly its inhibitory effect on E. coli. (Fig. 2D part B). In vivo study of the anti-prostatitis effects showed that by lowering inflammation, the Cur-Cu@HA delivery method effectively promoted recovery. Figure 2F shows the variations in the prostate circumstances among the experimental groups. The prostate in the experimental cohort was clearly enlarged and had a denser texture than in the normal group, suggesting effective modeling. Prostate of the two groups treated with Cur-Cu@HA, particularly at high dosages, Cur-Cu@HA shown better therapeutic efficacy than levofloxacin [101]. The Cur-Cu@HA administration method showed good possibilities for treating bacterial prostatitis. Combining focused administration, improved solubility, and strong antibacterial action, its multifarious approach points to it as a possible treatment choice for this illness [101].

2.2.2 Impact of physicochemical properties of nanocarriers on antibacterial efficacy

The antibacterial efficacy of nano-delivery systems depends not only on the encapsulated bioactive compound but is also significantly affected by the nanocarrier's physicochemical properties, such as particle size, surface charge (zeta potential), and polydispersity index (PDI) [119, 120]. These factors influence nanoparticle stability, bacterial interaction, biofilm penetration, and release behavior. Smaller nanoparticles, typically under 100 nm, demonstrate improved cellular uptake and deeper biofilm penetration, which aids in combating persistent infections [121]. For example, a zerumbone nanosuspension stabilized by SDS with an average size of 211 nm exhibited better drug release and efficacy than larger aggregates, highlighting how size reduction can enhance solubility and bioavailability [86]. Size also affects cellular internalization mechanisms, with smaller particles often entering cells via energy-dependent pathways more effectively [122]. Zeta potential plays a crucial role in colloidal stability and electrostatic interactions with negatively charged bacterial membranes; positively charged (cationic) surfaces enhance adhesion, disrupting membranes and promoting payload internalization, as seen with chitosan-based carriers like alginate-chitosan (ALL@CS), which increase positive charge in acidic conditions due to protonation of amino groups [123]. A high absolute zeta potential value ( > |30| mV) usually indicates good physical stability by preventing aggregation through electrostatic repulsion, demonstrated by the stable SDS-zerumbone system (− 30.9 mV) in contrast to the unstable HPMC-stabilized formulation (− 3.37 mV) [124]. The PDI reflects size distribution homogeneity, where values below 0.3 indicate a monodisperse nanoparticle population essential for consistent pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy, whereas higher values indicate size heterogeneity associated with variable biological responses and diminished effectiveness. Thus, the strategic design of nano-delivery systems for herbal antibacterials requires meticulous optimization of these physicochemical parameters to enhance targeting, uptake, and antimicrobial activity [125].

2.3 In vitro and in vivo results

Described in Table 1, the use of nano delivery strategies for herbal medicines has achieved fascinating results given several in vitro and in vivo experiments to evaluate their antibacterial activity. Showing the antibacterial properties of these medications, zone of inhibition assay and MIC assessments are the most widely used methods of evaluation. Allicin from garlic, delivered via nanoparticle carriers (chitosan-lecithin and polydopamine/tannic acid-allicin@chitosan), and Honey Bee Propolis Extract (HBP) in a biodegradable hydrogel, both demonstrated broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against gram-positive, gram-negative, fungal, and yeast species.

Present as a nanosuspension, zerumbone from ginger displayed considerable antibacterial effect against S. choleraesuis. Delivered in many forms, curcumin demonstrated strong antibacterial effect against several gram-positive bacteria as well as against a gram-negative strain, E. coli. Broad-ranging antibacterial action of oregano-derived compounds, thymol and carvacrol, exhibited significant antibacterial capacity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Delivered in numerous forms, carvacrol demonstrated amazing antibacterial action against several strains; co-delivery of other compounds through different nanocarriers enhanced their antibacterial properties. Aiming at a broad spectrum of bacterial strains, the complete in vitro data collectively show the efficacy of herbal components provided via nanocarriers to be potent antibacterial agents. Still, more in vivo study using repeated cell lines and testing is needed to confirm these positive in vitro results and so provide a more whole knowledge of their antibacterial characteristics.

3 Anticancer applications

Second only to heart disease (Hossen et al., 2019; Prabhu et al., 2015), cancer is a complicated collection of disorders marked by aberrant cell growth and proliferation ranked as one of the main causes of mortality worldwide [126, 127]. Although traditional chemotherapy targets fast dividing cancer cells well, its therapeutic potential is limited and it sometimes lacks specificity, therefore damaging healthy tissues [127, 128]. Effective in treating many cancers, synthetic drugs including cabazitaxel [129], mitomycin c [130], and daunorubicin [131] can have side effects similar to traditional chemotherapy including bone marrow suppression and gastrointestinal disturbances. Given these difficulties, scientists are looking more and more for new anticancer agents in natural therapies and herbal medications.

Such molecules have long been important in traditional medicine and have been thoroughly studied for their anticancer action. Actually, around 60% of pharmaceutical anticancer drugs come from natural sources [132]. Investigating combined effects of herbal substances and nanocarriers in cancer treatment is a growing field of study. Because of their special physicochemical characteristics, nanocarriers present a good basis for targeted drug delivery, hence improving the efficacy and lowering the systemic toxicity of anticancer drugs. We explore in this part the increasing amount of research on the anticancer properties of herbal substances combined with different nanocarriers. We review common herbal medicines and nanocarriers, offering striking illustrations from current studies.

3.1 Anticancer herbal compounds

For anticancer uses, we selected a panel of herbal compounds based on (ⅰ) strong preclinical evidence of antitumor effects observed across several relevant cancer models, (ⅱ) successful incorporation in a nano-based delivery system with evidence of increases in solubility, stability, targeting, or biological activity, and (ⅲ) chemical diversity, including flavonoids (quercetin, baicalein), stilbenes (resveratrol), catechins (EGCG), triterpenoids (ursolic acid), and alkaloids (berberine) [133, 134]. The examples selected allowed the review to discuss how to develop nanoformulations strategies based on distinct compound classes and types of cancers. Furthermore, a number of those agents (example-curcumin, berberine) even have dual antimicrobial and anticancer activity, reinforcing their potential importance to innovating in nano-delivery[135].

3.1.1 Turmeric

A polyphenol derived from the rhizome of turmeric (Curcuma longa), curcumin is a flexible herbal medicine valued for its many therapeutic properties, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer effects. In the field of anticancer research, curcumin shows its amazing power by altering many signalling pathways important in cell growth, death, invasion, metastases, and angiogenesis. Among its molecular targets are STAT3, AKT, MAPK, p53, Bcl-2, COX-2, and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) [136]. The hydrophobic character of curcumin and low solubility in water (11 ng/mL) [137] or physiological fluids combined with its instability in neutral and basic environments have driven the development of strategies to improve its solubility and bioavailability [138] (Table 2).

Summary of studies in the existing literature utilizing nano-delivery systems for herbal compounds for anticancer application

Among these methods, nanoparticulate drug delivery systems have become well-known for their ability to raise the water dispersibility of hydrophobic molecules such as curcumin. Characterized by their nano-size and core–shell structure, one creative technique uses sodium caseinate@CaP (calcium phosphate) (NaCas@CaP) nanodelivery systems (Table 2) [139]. These systems significantly enhance the stability of encapsulated curcumin, offering pH-responsive release in proximity to cancer cells, thereby augmenting its cellular antioxidant and anticancer efficacy.

Another promising avenue employs curcumin-loaded polyvinyl alcohol/cellulose nanocrystals (PVA/CNCs) membranes as localized delivery systems for breast and liver cancer (Table 2) [140]. These membranes are possible anti-infective biomaterials for wound healing in breast and liver cancer cases since they show broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and can thus restrict microbial growth by over 96–99%. Moreover, creative approaches have been used to solve the problem of adaptive treatment tolerance in cancer treatment, a phenomena wherein cancer cells develop resistance to therapeutic medications over time [141] (Table 2). These efforts show great progress in using curcumin's anticancer power in the dynamic terrain of nano-delivery devices.

3.1.2 Resveratrol

Renowned stilbenoid naturally present in grapes, red wine, peanuts, and berries, resveratrol has become a powerful herbal medicine with trifecta of therapeutic effects: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer. Regarding anticancer effects, the several modes of action of resveratrol have attracted much research. By means of CD95 signalling activation and elevation of CD95L expression, resveratrol has the ability to cause death in cancer cells. Targeted cancer treatment may find a bright future in this natural capacity to induce programmed cell death. Resveratrol also shows great ability to stop angiogenesis and tumour formation, mostly because of its modulation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [136]. Resveratrol is a strong enemy against cancer since it reduces the development of new blood vessels and disturbs the milieu necessary for cancer progression. Apart from directly affecting cancer cells and tumour microenvironment (TME), resveratrol shows anti-inflammatory action by preventing the creation of MMPs and pro-inflammatory cytokines [142]. These activities demonstrate resveratrol's multifarious approach in preventing the disease and aid to reduce the inflammatory cascade linked with cancer growth and progression. Resveratrol's flexible modes of action include autophagy induction, death induction, angiogenesis inhibition, metastases inhibition, and cancer cell metabolism reorientation [143]. Such variation in its anticancer properties emphasizes its possible use as a multifarious agent in the battle against several cancer types, including lung cancer and prostate cancer. Furthermore, recent developments have included creative resveratrol delivery techniques like transpapillary distribution for breast cancer treatment [144]. Emphasizing the need of customized delivery systems to maximize the healing capacity of this strong herbal ingredient, inulin-pluronic-stearic acid-based double-folded nanomicelles have also been presented for pH-responsive resveratrol distribution [145] (Table 2).

3.1.3 Genistein

Strong isoflavone naturally present in soybeans and some legumes, genistein has attracted a lot of interest for its several anticancer properties, including anti-inflammatory and antioxidant ones. It is a strong anticancer agent since it shows amazing ability to block tyrosine kinases fundamental in cell growth and survival. Furthermore, genistein affects cancer cells by causing cell cycle arrest in G2/M phase and death, coordinated by control of major actors like cyclin B1, CDK1, p21, p27, Bax, and caspase-3 [136]. Combining all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), which causes cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase and cell death via nuclear retinoic acid receptors, with genistein, a potent tyrosine kinase inhibitor, increases cytotoxic effects and cellular absorption in A549 lung cancer cells. This combination therapy shows promise for lung cancer treatment. For the co-delivery of genistein and ATRA to lung cancer cells, one such new method is the fabrication of inhalable dry powder nanocomposites of dual-targeted hybrid lipid-zein nanoparticles [146] (Table 2). Furthermore, by use of the HSPG receptor, genistein has shown its mastery in receptor-mediated endocytosis in human breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) [147] (Table 2). This concentrated approach holds considerable promise for the focused distribution of genistein to breast cancer cells, therefore enhancing its therapeutic activity. But low oral bioavailability and restricted water solubility of genistein make clinical application difficult. Techniques to overcome these constraints will enable to maximize its biodistribution and absorption in cancer treatment.

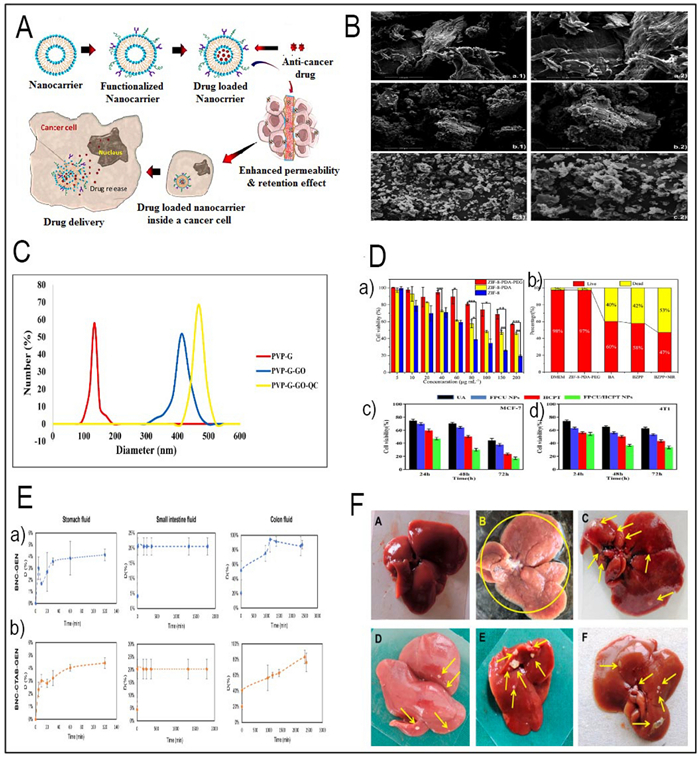

3.1.4 Baicalein

Baicalein is a flavonoid derived from the root of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, a Chinese herb with diverse medicinal benefits, such as antibacterial, antioxidant, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory effects. Among its many virtues, baicalein's anticancer activity is especially remarkable, as it can modulate the cell cycle, scavenge oxidative free radicals, induce apoptosis, and suppress tumor infiltration and spread. By releasing cytochrome c into the cytoplasm and activating caspase-9, Baicalein causes death in cancer cells, therefore triggering a planned biological response against malignancy [136]. Baicalein thus shows promise as a possible future osteosarcoma candidate. Moreover, baicalein's anticancer ability reaches the domain of angiogenesis control by downregulating important elements including matrix metalloproteinase-9 [148]. Stressing cancer cell survival as well as the building of new blood vessels required for tumor progression, this dual-action approach highlights its possible anticancer activity. Gao et al., (2021) coupled chemotherapy with photothermal therapy using nanocomposites based on ZIF-8 to produce a pH-responsive drug delivery system known baicalein @zeolite imidazolate frameworks-8 (ZIF-8)-polydopamine (PDA) (BZPP) [149]. MTT test evaluations of drug carrier cytotoxicity Fig. 3D (a clearly indicates a dose-dependent relationship whereby the viability of A549 cells lowers gradually with increasing nanocarrier concentration. In the framework of cancer treatment, the challenge usually goes beyond the eradication of tumor tissue following surgery. The cell survival rates of the ZIF-8-PDA-PEG (Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8, Polydopamine, and Polyethylene Glycol), BZPP (Buffer Zone Protection Program), and BZPP + near-infrared (NIR) groups displayed in Fig. 3D part b [149]. Clinically, remaining cancer cells and the required means of rebuilding damaged bone structure after surgery raise challenging concerns. Functional biomaterial scaffolds provide promising responses linking damaged tissues and stopping cancer recurrence [148]. Using electrospinning, researchers recently explored the possibility of baicalein to mix it with a hyaluronic acid-polyethylene oxide-transforming growth factor beta-2-polyvinyl alcohol nanofiber scaffold (Table 2) [150]. Since it showed that baicalein-loaded nanofiber scaffolds may sufficiently prevent local recurrence of bone cancers, this new approach underlined the tremendous adaptability of these materials as biomedical tools in the fight against cancer.

A Illustration of nanocarrier targeting, binding, internalization, and drug release in cancer therapy (Redesigned from reference [127] with permission). B SEM images of PEC, PEC-CUR and PEC-T-CUR. Scale bars of 100 μm (images in the left, magnification ×1000) and 50 μm (images in the right, magnification ×2000) (Redesigned from reference [138] with permission). C DLS analysis and the size distribution of PVP-G, PVP-G-O and PVP-GGO-QC nanocomposite (Redesigned from reference [151] with permission). D (a) Cell viability of ZIF-8, ZIF-8-PDA, ZIF-8-PDA-PEG and A549 cells after incubation for 24 h (Redesigned from reference [149] with permission). (b) Survival area of A549 cells treated with DMEM, ZIF-8-PDAPEG, free BA, BZPP, BZPP + NIR for 24 h (BA concentration: 20 μgmL−1) (Redesigned from reference [149] with permission). (c) Cell viability of MCF-7 and (d) 4T1 cells dealt with different groups was detected by CCK-8 assay (Redesigned from reference [197] with permission). E (a, b) The release profile of genistein within gastrointestinal fluids (Redesigned from reference [185] with permission). F Representative illustrations of rat liver specimens: A the typical group of liver tissue exhibits a normal appearance, showing no macroscopically detectable pathological alterations. B The disease control group's liver tissues exhibited notable alterations in terms of hue, texture, and consistency. The tissue displayed a pallid pink coloration along with enlarged dimensions and a wrinkled surface adorned with numerous visible nodules (indicated by yellow arrows). C Prophylactic RS treated group demonstrated very few nodules (yellow arrows) and lesions. D Prophylactic RL5 treated group in rats showed marked reduction in the number of nodules and damaged caused by NDEA. E, F Therapeutic RS and RL5 treated groups in rats showed reduction in the number of nodules (Redesigned from reference [165] with permission). (p-value = p, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001)

3.1.5 Quercetin

Quercetin, a flavonoid abundantly found in various fruits and vegetables, possesses a versatile repertoire of healing attributes, encompassing antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects. Among its remarkable anticancer attributes, quercetin's ability to induce apoptosis in cancer cells takes centre stage. It does so by orchestrating a complex interplay involving intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, featuring key players like Bcl-2 family proteins, cytochrome c, caspases, FasL, and TRAIL. Additionally, quercetin exerts control over cell growth by regulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling cascade, further bolstering its anticancer potential [136]. In a separate study, Najafabadi et al., employed nanocarriers consisting of gelatin (G)-polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) coated graphene oxide (GO) for the first time. These nanocarriers were loaded with the drug quercetin (QC), and a dual nanoemulsion water/oil/water system with bitter almond oil was developed as a membrane to regulate the release of the drug. The size distribution of the nanocarriers was ascertained using dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis. The results are displayed in Fig. 3C. The study's findings indicate that PVP-G-GO-QC holds promise as a potentially innovative approach for cancer treatment [151].

3.1.6 Ursolic acid

Ursolic acid (UA), also known as urson, prunol, or malol, is a pentacyclic triterpenoid compound widely found in nature. This leads to DNA damage and cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase. This immune-boosting aspect not only strengthens the body's natural defences but also complements the herb's anticancer arsenal [136]. Ursolic acid (UA), a compound widely distributed in various dietary plants such as Oldenlandia diffusa, has emerged as a promising anticancer agent. UA's anticancer effects span across various aspects of cancer biology, making it a potent weapon against the disease [152] (Table 2). It modulates various cellular factors that regulate cell proliferation, metastasis, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and autophagy. Liver cancer, among other cancer types, has been a focal point of UA's anticancer activities [153]. UA exerts its effects through diverse mechanisms, such as affecting NF-κB factors and apoptosis signalling pathways in tumor cells. However, UA's hydrophobic nature has posed challenges to its clinical application [154, 155]. To overcome these limitations, an innovative method entails development of a polymeric drug delivery system known as poly (ursolic acid) (PUA), which is synthesized through the polycondensation of UA. PUA can self-assemble into nanoparticles (PUA-NPs), offering a dual benefit [156] (Table 2). It not only serves as a drug carrier but also introduces an additional therapeutic dimension. This approach unveils thrilling prospects for improved drug delivery and therapeutic effectiveness.

3.1.7 Epigallocatechin gallate

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a potent catechin in green tea, has remarkable anticancer properties. Green tea is one of the most widely consumed drinks globally and has many health advantages, mainly due to EGCG. EGCG has a multifaceted approach to combating cancer. This natural phenolic compound can target various cancer types by inducing cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, autophagy, and oxidative stress in tumor cells. These are key processes that EGCG can modulate to inhibit cancer growth [136]. EGCG also affects tumor progression and metastasis by targeting molecular factors such as VEGF, MMPs, and NF-κB. By doing so, EGCG can curb tumor angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis, making it a comprehensive anticancer agent. However, EGCG has poor bioavailability, limiting its clinical. To address this challenge, nano formulations of EGCG are arising as a promising alternative. These nano chemo preventive approaches include various types of EGCG nanoparticles, such as lipid-based, polymer-based, carbohydrate-based, protein-based, and metal-based nanoparticles [157]. In a study conducted by Saha et al., an amphiphilic PEG-polycaprolactone (PCL) diblock copolymer was utilized. This copolymer was co-encapsulated with epigallocatechin-3-gallate and rutin nanorods, which had dimensions of approximately 110 nm in length and 26 nm in width. The purpose of this combination therapy was to synergistically combine the anticancer and antibacterial properties. The spectrophotometric approach was used to evaluate the release kinetics of EGCG and rutin from co-encapsulated nanorods. The experiments were conducted at 37 ℃ in PBS with varying pH levels (7.4 and 5.0), as depicted in Fig. 4C part B. The study found that the release of rutin from co-encapsulated nanorods followed a slow and persistent pattern at various pH levels. Additionally, there were no noticeable variations in the release rates at different pH values (Fig. 4C part a [158]. This field holds the potential to unlock the full therapeutic power of EGCG and enhance its clinical utility. EGCG's journey from a humble tea leaf to a potent anticancer agent shows the importance of exploring natural compounds in the fight against cancer. Innovative nanotechnological approaches are poised to revolutionize its clinical impact.

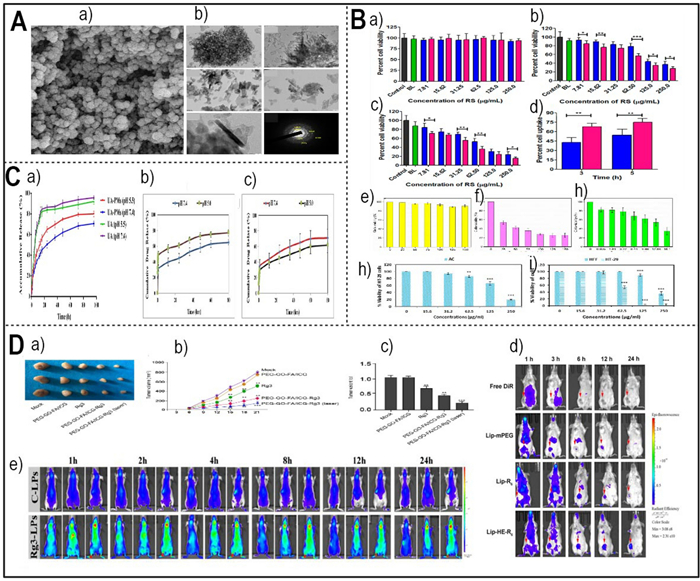

A a) FE-SEM images of Cur–Art NioNPs (Redesigned from reference [164] with permission). (b) TEM photos show the magnification levels of ×40000, ×40000X, ×80000, ×80000, ×200000, and a SAED pattern (Redesigned from reference [175] with permission). B (a) The cytocompatibility of RS and RL5 was assessed by measuring their cytotoxicity against normal mouse fibroblast cell lines (L929) using the colorimetric MTT test (Redesigned from reference [165] with permission). (b, c) The cytotoxicity of BL, RS, and RL5 on HepG2 cell lines was assessed over 24 and 48 h. Cell viability was measured using the MTT test at various drug doses (Redesigned from reference [165] with permission). (d) A bar graph illustrating the quantitative cell internalization of RS and RL5 in HepG2 cancer cells. The evaluation was conducted at 3 and 5 h time intervals using HPLC (Redesigned from reference [165] with permission). An in vitro cytotoxicity analysis of the BSA NPs (e), pure BER (f), and BER–BSA NPs (g) against the LN229 cell line following 24 h incubation (Redesigned from reference [160] with permission). (h) MTT assay. A Decreased HT-29 cell viability in AC treatment (Redesigned from reference [75] with permission). (i) MTT assay. comparison of growth inhibition of HT-29 cancer cells compared to HFF in AC-PLCF-NPs treatment (Redesigned from reference [75] with permission). C (a) The in vitro cumulative release profile of ursolic acid (UA) from polymeric micelles loaded with UA (UA-PMs) in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution at pH 7.4 or pH 5.5, and at a temperature of 37 ℃, is compared to the release profile of free UA (Redesigned from reference [152] with permission). Drug release kinetics of (b) EGCG and (c) Rutin (Redesigned from reference [158] with permission). D (a) Representative images of dissected tumors from nude mice are presented (Redesigned from reference [174] with permission). (b) The average tumor volume is calculated and shown (Redesigned from reference [174] with permission). (c) The average tumor weight is calculated and shown (Redesigned from reference [174] with permission). (d) The in vivo imaging of 4 T1 tumor bearing mice after intravenous injection of free DiR, DiR loaded Lip-mPEG, Lip-R6, and Lip-HE-R6 (Redesigned from reference [167] with permission). (e) In vivo fluorescence imaging of C6 orthotopic glioma bearing nude mice treated with DiR-loaded Rg3-LPs at different time points (Redesigned from reference [169] with permission). (p-value = p, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001)

3.1.8 Berberine

Berberine, a potent isoquinoline alkaloid from the roots of medicinal plants such as goldenseal, barberry, and Oregon grape, has remarkable anticancer properties. Berberine has multiple mechanisms that target critical signalling pathways in cancer cells. Berberine can modulate key cellular factors, such as activated protein kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinases, and NF-κB. Berberine can intervene at multiple stages of tumorigenesis in cancerous cells [159]. These actions make berberine a versatile anticancer agent. In a separate study, scientists sought to create EDC-crosslinked BSA NPs as a method of delivering drugs by enclosing berberine (BER). The objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of the medication discharge in treating human glioblastoma LN229 cells. An MTT experiment was conducted to assess the cytotoxic effects (Fig. 4B part e, f, and g [160]. Researchers have also explored innovative delivery methods to optimize berberine's therapeutic impact. One example is nanotechnology, where berberine is combined with nanosized carbon nanoparticles, such as C60 fullerene (C60) [161] (Table 2). This method enhances the delivery of berberine into leukemic cells, offering improved efficacy and precision in cancer treatment. Berberine's evolution from botanical origins to a multifaceted anticancer agent shows the potential of nature's pharmacopeia in the fight against cancer. Novel delivery methods may expand the clinical impact of berberine in cancer therapy.

3.1.9 Artemisinin

The plant Artemisia annua contains the sesquiterpene lactone artemisinin, which has antitumor characteristics. By producing ROS and stimulating the mitochondrial pathway, it has the ability to trigger both autophagy and apoptosis in cancerous cells [162]. Artemisinin also inhibits tumor angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis by suppressing the expression of factors like VEGF and MMPs. These factors facilitate cancer's growth and dissemination [163]. Researchers have developed novel strategies to optimize artemisinin's anticancer effects. In another study, Amandi et al., employed curcumin–artemisinin (ART) co-loaded niosomal NPs (Cur–ART Nio NPs) as a therapeutic agent against colorectal cancer cells. The topography and shape of the generated Nio NPs were examined using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM), as shown in Fig. 4A. The high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) measurement of the cell extract after 5 h revealed that Resveratrol (RS) and optimized liposomes formulation (RL5) had cellular internalization rates of 54.2% and 74.98%, respectively (Fig. 4A part a) [164, 165]. Another example is folate-modified erythrocyte membrane-camouflaged nanoparticles (Table 2) [166]. These nanoparticles enhance the delivery and impact of artemisinin in cancer therapy. They have components such as perfluorohexane, magnetic Fe3O4, and artemisinin that offer precision cancer treatment. As an additional illustration, Yu and colleagues employed a reversibly activatable cell-penetrating peptide to design liposomes loaded with artemisinin known as ART-Lip-HER6. The purpose was to target tumors, and the performance of these modified liposomes was examined both in vitro and in vivo. The targeting of different formulations to tumors was assessed in Balb/C mice with 4 T1 tumors. Figure 4D part d displays the distribution of DiR-loaded liposomes in animals at different periods [167]. Artemisinin's transformation from a traditional remedy for malaria to a potent anticancer agent shows the potential of natural compounds in the fight against cancer. Innovative delivery methods may enhance its clinical impact.

3.1.10 Ginsenoside Rg3

Ginsenoside Rg3, a saponin from ginseng roots, has anticancer properties. It can inhibit cell proliferation, induce apoptosis, and stimulate autophagy in cancer cells. These are key processes that Ginsenoside Rg3 can modulate to suppress cancer growth [168]. Ginsenoside Rg3 also reverses multidrug resistance, a major challenge in cancer treatment. It restores the effectiveness of therapeutic drugs by blocking the mechanisms that make cancer cells resistant [169]. Ginsenoside Rg3 affects the tumor TME as well. It reduces angiogenesis, inflammation, and immune evasion, creating a less favourable environment for cancer to thrive. Moreover, Ginsenoside Rg3 inhibits cancer metastasis and recurrence, two factors that increase cancer's lethality. It prevents the spread and resurgence of cancer, making it a formidable anticancer agent [170–173]. Furthermore, various types of nanoparticles were employed to transport Ginsenoside Rg3 to cancer cells. The nanoparticles were synthesized by Lu et al., (2021) utilizing GO connected to a photosensitizer called indocyanine green. FA and PEG were also incorporated into the nanoparticles, which were then embedded with Rg3. The researchers investigated the impact of the formulation with photodynamic therapy for the management of osteosarcoma. The study revealed that the advancement of tumor was significantly inhibited by Rg3. Furthermore, the formulation treatment and NIR laser showed an even stronger suppressive effect on tumor growth in nude mice. Figure 4D part a, b, and c indicate that this impact was detected in the system [174]. In another study, Zhu and colleagues created a versatile liposomal system based on ginsenoside Rg3, known as Rg3-LPs. The active glioma selectivity and intratumoral dispersion capacities of Rg3-LPs were significantly enhanced in vivo. Due to the fact that the C6 glioma cell line was derived from adult rats, there is a possibility that implanting C6 cells into balb/c mice of different strains could elicit an immunological response and perhaps impact the outcomes of immune regulation. Thus, a rat model with a C6 brain tumor was created to validate the pharmacodynamics of the liposomes (Fig. 4D part e) [169]. Ginsenoside Rg3's transformation from ginseng roots to a promising anticancer agent shows the ability of natural substances in the fight against tumor. Research may reveal more of its mechanisms and impact.

3.2 Delivery of herbal compounds in anticancer application

The delivery of anticancer herbal compounds is a burgeoning field with promising implications for cancer treatment and therapy. Novel techniques in nanoscale have been investigated as potential solutions to the problems caused by these chemicals' poor absorption, stability, and dispersion. This section delves into various nanocarriers and strategies used for the efficient delivery of anticancer herbal formulations, with a focus on their advantages and applications. Figure 3A illustrates the mechanism of action of a nanocarrier-based drug delivery system in cancer treatment.

3.2.1 Hydroxyapatite

Hydroxyapatite (HAp), a vital biological molecule found in bones, has emerged as a versatile material with a multitude of clinical applications. Sebastiammal et al., (2020) highlight its significance in significantly improving the bioactivity and compatibility of synthetic molecules. A comprehensive structural investigation of pure HAp was conducted. The Fig. 4A part b illustrates the various magnifications of pure surfactant-free HAp NPs, providing a global view. In the context of anticancer therapy, HAp has shown promise in serving as a carrier for herbal compounds, offering enhanced bioavailability and controlled release, thereby improving the therapeutic efficacy (Table 2) [175].

3.2.2 Hydrogels

Using hydrogel—a 3D structure made up of hydrophilic polymers—in conjunction with antitumor herbal compounds such as curcumin (CUR), presents an innovative approach to drug delivery. This strategy holds the potential to provide superior functionality to composite materials, particularly in medication transportation and nanomedicine applications. nanohydrogels offer benefit of protection of loaded drugs and controlled release through stimuli-responsive mechanisms or biodegradable bonds [118, 138].

Chondroitin sulfate (CS), natural polysaccharides, have garnered interest in the medical field due to their unique characteristics. When combined with CUR, they can form physical polyelectrolyte complex hydrogels that provide a good level of drug dispersion. This approach, as highlighted by Caldas et al. (2021), offers a potential platform for the controlled discharge of anticancer herbal formulations, ameliorating their curative capacity [138]. In their study, Caldas and colleagues synthesized CS and chondroitin sulfate hydrogels loaded with CUR. The hydrogels were then tested for their ability to induce apoptosis in cancerous cells. Figure 3B displays SEM images, revealing a noticeable reduction in particle dimension when compared [138].

3.2.3 Liposomes

Liposomes, among various nanoparticle formulations, have proven to be highly effective in delivering therapeutic drugs and imaging agents. Their structural properties closely mimic natural cellular biomembranes, offering advantages such as biocompatibility, enhanced stability, sustained drug release, biodegradability, safety, and scalability [165]. Cell viability was assessed using the MTT test at several doses of the medication (Fig. 4B part a–d). when resveratrol (RS) loaded cationic liposomes exhibited comparable cell viability, indicating their cytocompatibility. Two mice from the unaffected group who had the illness were taken apart after the ninth week of the trial, and histology was used to examine the specimens to confirm that malignancy had successfully developed. The liver specimens' morphology was evaluated for all groups, as shown in Fig. 3D part a–f. When RS and RL5 were given to rats with hepatocellular carcinoma, there were significantly fewer liver nodules when contrasted with the group of animals that had the condition [165]. emphasize the success of liposomal nanoscale formulations in anticancer drug delivery, underscoring their potential in improving treatment outcomes (Table 2) [165].

3.2.4 Bacterial nanocellulose

Bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) is a nontoxic substance with distinct structural characteristics, making it suitable for various medical applications. Castaño and colleagues (2022) examined the use of BNC and BNC that has been combined with cetyltrimethylammonium (BNC-CTAB) in order to assess their effectiveness as carriers for genistein, with the goal of achieving controlled release for cancer chemoprevention [185]. They discussed the potential of BNC in drug delivery systems. Furthermore, the percentage of genistein (GEN) dispersed from dehydrated films comprising BNC-GEN and BNC-CTAB-GEN was evaluated and is illustrated in Fig. 3E part a, b. BNC's three-dimensional network of nanoribbons, high surface area, open porosity, and tensile strength make it a promising candidate for encapsulating anticancer herbal compounds, offering controlled drug release and targeted therapy (Table 2) [185].

3.2.5 Polymer micelles

Polymer micelles (PMs), formed from amphiphilic block copolymers, have gained recognition as nano-sized medication formulation. Zhou et al., (2019) highlight their capacity to dissolve in water insoluble anticancer compounds within their hydrophobic inner core. The release kinetics of UA-PMs were assessed in vitro at a temperature of 37 ℃. The releasing media used was PBS, and the pH settings tested were 7.4 and 5.5 (Fig. 4C part a). PMs offer a novel approach to enhance drug solubility and improve the delivery of herbal compounds, thereby augmenting their anticancer activity [152].

3.2.6 Carboxymethyl chitosan

Carboxymethyl chitosan (CMCS), characterized by its water solubility, biocompatibility, and biodegradability, functions well as a carrier for sustained medication transportation. Jing et al. (2021) emphasize the potential of CMCS in delivering anticancer herbal compounds, offering a controlled and sustained release, thereby enhancing the therapeutic effectiveness (Table 2) [197]. An optimal nano-drug carrier should exhibit unique responses to intricate biological surroundings, in addition to demonstrating high biocompatibility and minimal cytotoxicity. The survival rates of NPs following exposure to breast cancerous cells for durations of 24, 48, and 72 h, shown in Fig. 3D part c, d [197].

In conclusion, the delivery of anticancer herbal compounds through nanotechnology-based approaches offers exciting possibilities for improving cancer treatment. These innovative delivery systems, including hydroxyapatite, micro/nano-hydrogel, chitosan, liposomal nanoparticles, and bacterial nanocellulose, among others, hold the ability to improve the availability, stability, and targeting of herbal substances, ultimately contributing to more effective cancer therapy.

3.3 In vitro and in vivo results

The utilization of nano delivery systems for herbal compounds has yielded encouraging outcomes in various assays. Among the methods reviewed in Table 2, in vitro tests (such as MTT and cell toxicity assays) were commonly applied to evaluate the effectiveness of nano-delivered herbal substances on different cell lines. Additionally, assays related to cytotoxicity, apoptosis, and antioxidant capacity were frequently conducted. Notably, the most frequently employed cell lines included cancer cell lines, such as HT-29, Saos2, MCF7, HeLa, A549, and more, reflecting the potential of these nano-formulations in cancer therapy. In vivo studies showcased the effectiveness of nano-delivered herbal compounds on tumor-bearing animal models. These experiments included assessing antitumor effects, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics. Importantly, repeated cell lines such as 4T1 and MCF-7 were used in in vivo studies, indicating the translational potential of these nanoformulations in preclinical research. The overall results demonstrated the significant potential of nano transportation strategies for herbal conjugation in enhancing their bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy. These systems exhibited cytotoxic impressions on different cancerous cells, showing their ability as anticancer agents. Moreover, the in vivo evaluation supported the translational value of these formulations, showing promising antitumor effects and favorable biodistribution. In the context of treatment for cancer along with various disorders, our results highlight the relevance of nano delivery systems in using the curative abilities of herbal medicines.

3.4 Advanced nanocarrier strategies for enhanced herbal anticancer therapy

3.4.1 Advanced targeting mechanisms for herbal anticancer delivery

The therapeutic potential of anticancer herbal bioactives is often limited by their inherent pharmacokinetic limitations and nonspecific distribution; however, these challenges can be addressed by engineering advanced nanocarriers with sophisticated "smart" functionalities for targeted, spatiotemporally controlled drug release [119]. These approaches are broadly categorized as passive and active targeting, which are frequently combined with stimuli-responsive systems for precision therapy. Passive targeting exploits the distinctive pathophysiology of solid tumors, notably the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, wherein the disorganized, hyperpermeable vasculature (with fenestrations ranging from 100 to 2 μm) and compromised lymphatic drainage allow nanocarriers of an optimal size (10–200 nm) to extravasate and accumulate selectively within the tumor interstitium [213]. Surface properties are crucial, as coatings like polyethylene glycol (PEG) confer a stealth characteristic by minimizing opsonization and recognition by the mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS), thereby prolonging circulation time and enhancing tumor accumulation via the EPR effect [214]. To further improve specificity and cellular uptake, active targeting strategies functionalize nanocarrier surfaces with ligands that bind to receptors overexpressed on cancer cells, such as folic acid for the folate receptor (FR-α) [215] or transferrin for the transferrin receptor (TfR1) [216], promoting receptor-mediated endocytosis. This was exemplified by the significantly enhanced cytotoxicity and cellular uptake achieved through the co-delivery of genistein and doxorubicin via targeted lipo-polymeric nanoconstructs in MDA-MB-231 cells [217, 218].

3.4.2 Tumor microenvironment-responsive (smart) carriers

The tumor microenvironment (TME) exhibits biochemical properties distinct from those of healthy tissues, a feature exploited by smart nanocarriers designed to remain inert in circulation yet undergo triggered structural changes or degradation for precise drug release at the tumor site [219–221]. One key strategy leverages the acidic extracellular pH of tumors (~ 6.5–6.8), a consequence of aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect), and the even lower pH of endo/lysosomal compartments (~ 5.0–6.0). pH-responsive systems incorporate ionizable groups or acid-labile bonds that destabilize under these conditions; for instance, pH-sensitive liposomes composed of lipids like DOPE transition from a lamellar to a hexagonal phase at low pH, facilitating content release [222]. Conversely, redox-responsive carriers capitalize on the dramatically elevated intracellular concentrations of glutathione (GSH) in cancer cells. These systems are engineered with disulfide (–S–S–) bonds that remain stable extracellularly but are cleaved by the high cytosolic GSH levels, resulting in carrier disintegration and cytoplasmic drug release [223]. Furthermore, enzyme-responsive nanocarriers are designed with substrates for tumor-overexpressed enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) or hyaluronidases. Enzymatic cleavage of these substrates, for example the degradation of a hyaluronic acid-based shell by hyaluronidase, compromises the carrier's integrity and triggers drug release, often while simultaneously enabling receptor targeting [224]. Lastly, to address the severely hypoxic regions common in solid tumors, hypoxia-responsive systems incorporate groups like nitroimidazole or azobenzene, which are reduced under low oxygen tension, becoming hydrophilic and causing carrier breakdown for targeted drug release in these resistant areas [225, 226].

3.4.3 The necessity of nanocarriers for herbal anticancer applications

The transition to advanced nanocarrier systems represents a crucial step for the successful clinical translation of herbal bioactives in oncology, as their inherent limitations—including poor aqueous solubility, chemical instability, rapid clearance, and non-specific toxicity—severely diminish their efficacy as free agents. Nanocarriers directly counter these challenges through several mechanisms: they enhance solubilization and stability by encapsulating hydrophobic compounds like curcumin or artemisinin within liposomes or polymeric nanoparticles, thereby protecting them from degradation [227–229]; they improve bioavailability and extend circulation times via nano-sizing and surface modifications like PEGylation, which reduce renal filtration and mononuclear phagocyte system uptake, promoting tumor accumulation through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect; and they enable targeted delivery and reduced toxicity by utilizing ligands for active targeting and stimuli-responsive release within the tumor microenvironment (TME), which concentrates the drug at the disease site while sparing healthy tissues. Furthermore, nanocarriers can overcome multidrug resistance (MDR) by evading efflux pumps such as P-glycoprotein and allow for the co-delivery of chemotherapeutic agents with chemo-sensitizing herbal compounds like ginsenoside Rg3 for synergistic therapy [230]. Consequently, the progression from simple encapsulation to intelligently engineered, multifunctional nanocarriers is fundamental to realizing the full potential of herbal medicines, transforming them into viable, effective, and safe anticancer therapeutics [231].

4 Wound healing applications

Preparations from traditional medicinal plants have long been utilized for wound healing purposes, addressing a diverse array of skin-related diseases. Herbal treatments in wound healing encompass a multifaceted approach involving disinfection, debridement, and the provision of a conducive condition to assist the natural healing process [1].