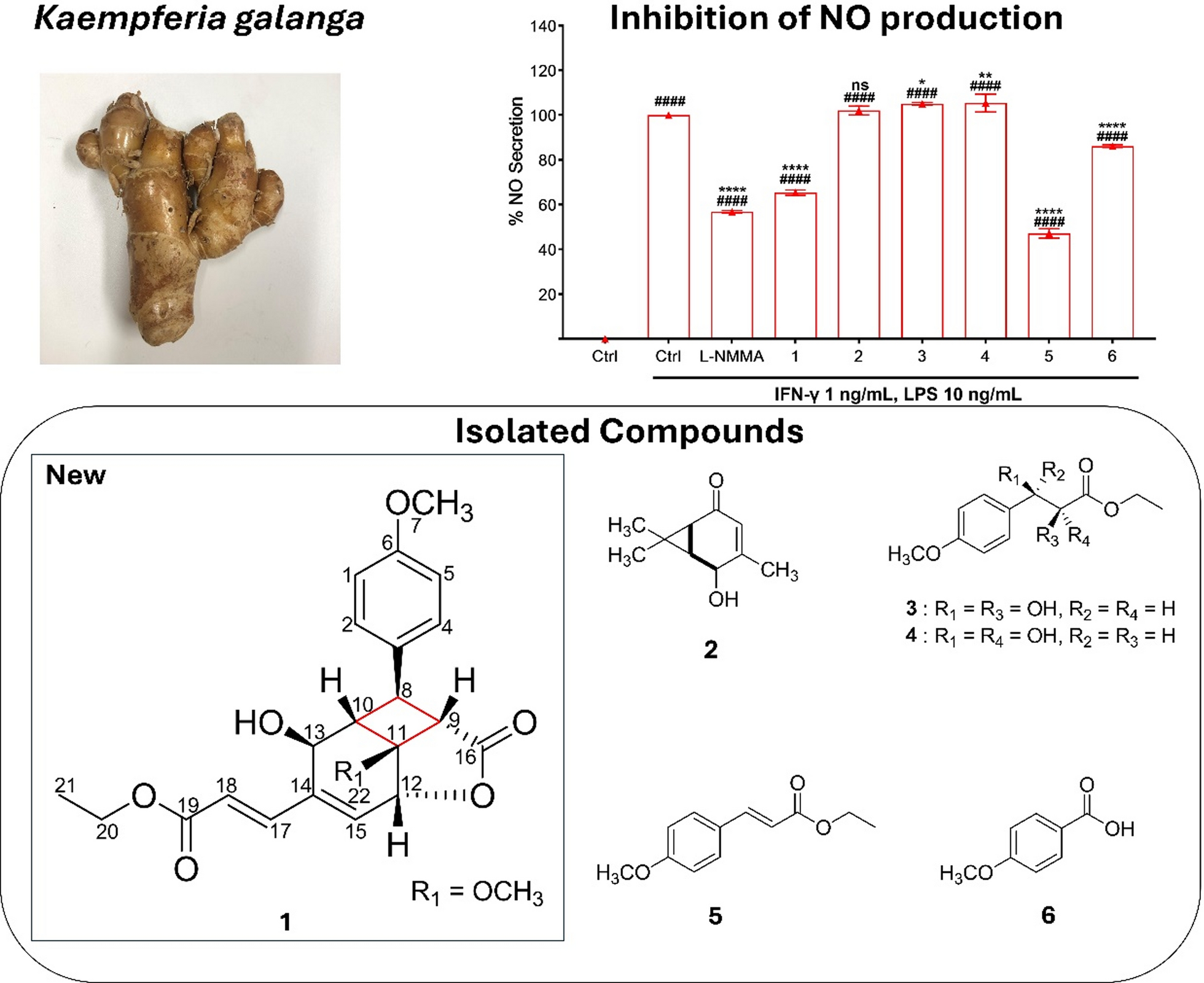

Kaemphenolide: a cyclobutane-bearing phenylpropanoid from Kaempferia galanga L. with nitric oxide inhibitory activity

Abstract

An undescribed phenylpropanoid dimer featuring a rare cyclobutane ring was isolated from the rhizomes of Kaempferia galanga L., a medicinal plant traditionally used in Southeast Asia for its anti-inflammatory and therapeutic properties. Kaemphenolide (1), along with five known constituents, was obtained by separations of methanolic extract using chromatography. The presence of a cyclobutane ring within the phenylpropanoid scaffold represents an unusual structural motif among natural products and underscores the chemical uniqueness of this molecule. To evaluate its biological relevance, 1 was tested for its ability to inhibit nitric oxide (NO) production in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. The compound exhibited anti-inflammatory activity, with an IC50 value of 23.1 ± 6.40 µM.Graphical Abstract

Keywords

Phenylpropanoid Cyclobutane Kaempferia galanga Anti-inflammation1 Introduction

Kaempferia galanga L. (Zingiberaceae) is a prominent medicinal and culinary plant widely utilized throughout Southeast Asia, notably in Indonesia, China, and Malaysia [1, 2]. Traditionally, it has been employed to address a range of ailments [3], including inflammation [4], hypertension [5], headaches [6], and digestive disorders [7]. The rhizome of KG is also a key ingredient in traditional remedies such as jamu beras kencur in Indonesia [8]. A review by Wang et al. documented the isolation of 97 compounds from K. galanga between 1987 and 2020, underscoring the plant’s significant chemical diversity and its sustained potential as a source of bioactive natural products [9].

Phenylpropanoids represent a structurally and pharmacologically significant class of compounds identified within diverse natural product [10]. A recent study by Zhu et al. (2024) has highlighted the presence of six new phenylpropanoids isolated from K. galanga, including four containing cyclobutane rings formed through [2 + 2] cycloaddition [11]. Interestingly, only one of those compounds exhibited notable anti-inflammatory activity, indicating that structural diversity may contribute to the varied biological profile. Cyclobutane-containing natural products possess a unique structural characteristic due to the inherent ring strain and biosynthetic challenges of forming four-membered carbocycles [12]. Despite their rarity, these frameworks often confer distinct biological activities, positioning them as promising scaffolds in drug discovery [13]. The cyclobutane motif, though relatively rare among natural products, appearing in fewer than 0.1% of known structures due to its high ring strain and biosynthetic complexity [12] remains a valuable scaffold that inspires synthetic efforts, particularly through [2 + 2] cycloaddition strategies [14, 15], to construct or optimize structurally intricate and biologically active compounds. Here, we describe the isolation of six isolated compounds including a cyclobutane-containing phenylpropaoid from K. galanga, along with an evaluation of its anti-inflammatory activity.

2 Results and discussion

A phenylpropanoid bearing cyclobutane ring, compound 1, was isolated as a yellow oil from the ethyl acetate fraction. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis revealed an Rf value of 0.3 in a solvent system of n-hexane:ethyl acetate (1:1), with absorption observed under UV Light at 254 nm. Upon heating post-derivatization with 10% H2SO4, the compound exhibited an orange coloration under 366 nm UV light. High-resolution ESI-Orbitrap-MS in positive ion mode displayed a molecular ion peak at m/z 401.15958 [M + H]+, consistent with a molecular formula of C22H24O7.

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy indicated the presence of a hydroxyl group through a broad absorption band at 3421 cm⁻1 and a carbonyl group at 1714 cm⁻1. The 1H NMR spectrum (Table 1) of compound 1 showed signals attributable to four aromatic protons [δH 7.19 (2H, J = 8.5 Hz), 6.90 (2H, J = 8.5 Hz)], consistent with a 1,4-disubstituted benzene ring; a pair of trans-olefinic protons [δH 7.38, 6.26, each J = 16 Hz]; a single olefinic proton (δH 6.41); two oxymethine protons (δH 5.15, 4.46); two methoxy groups (δH 3.81, 3.40); an oxygenated ethyl moiety (δH 4.26, q, 2H; 1.32, t, 3H); and several other resonances corresponding to methine protons.

1H- and 13C-NMR spectral data of compounds 1 and 1 a

The 13C NMR spectrum (Table 1) exhibited 20 carbon signals (with two overlapping), including two ester carbonyls (δC 175.1, 166.2), eight sp2 carbons (including overlapping aromatic carbons), and five oxygenated carbons [δC 77.9, 63.2, 60.9; and methoxy carbons at δC 55.4, 51.9]. The HMQC experiment confirmed direct proton-carbon correlations, as listed in Table 1.

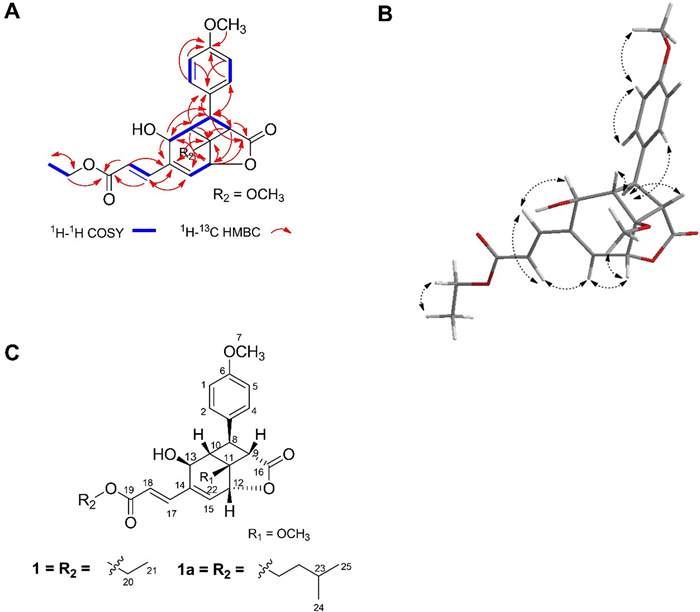

The COSY spectrum demonstrated proton coupling within the aromatic system [H-1/H-5 (δH 6.90), H-2/H-4 (δH 7.19)], between oxymethine protons H-12 (δH 5.15) and H-15 (δH 6.41), between the ethyl protons H-20 (δH 4.26) and H-21 (δH 1.32), as well as between the trans-olefinic protons H-17 (δH 7.38) and H-18 (δH 6.26). Evidence for the presence of a cyclobutane ring was indicated by the deshielded resonances and correlations involving H-8 (δH 2.67), H-10 (δH 3.29), and H-9 (δH 3.22), with further support from HMBC correlations between H-9/C-11 and H-10/C-11 (Fig. 1A). Further HMBC correlations supported the structural connectivity between the cyclobutane ring, a lactone, and a cyclohexane moiety. Specifically, correlations were observed between H-8/C-16, H-9/C-12, H-12/C-16, H-12/C-11, H-12/C-14, H-13/C-8, and H-10/C-12. The first methoxy group [δH 3.81, δC 55.4] was attached to the aromatic ring, evidenced by HMBC correlations between H-7 and C-6. The second methoxy group [δH 3.40, δC 51.9] was linked to the cyclobutane ring, as shown by the HMBC correlation between H-22 and C-11.

Compound 1. A 1H–1H COSY and HMBC correlations; B 1H–1H NOESY correlation; C Comparison of compounds 1 and 1a

The planar structure of compound 1 was elucidated by extensive 2D NMR analysis (Fig. 1A). HMBC correlations between H-8/C-3, H-8/C-4, and H-2/4/C-8 further confirmed the linkage of the cyclobutane to the methoxyphenyl moiety. The ethyl acrylate unit was found to be appended to the cyclohexane ring at its olefinic side, supported by HMBC correlations involving H-18/C-14, H-17/C-19, H-18/C-19, H-17/C-15, and H-20/C-19.

A structurally similar compound, 1a, was previously reported by A. Schrader et al. as a photochemical product [16]. The primary structural divergence between 1 and 1 a lies in the nature of their alkyl ester substituents (Fig. 1B). NOESY spectra provided additional stereochemical insight, revealing cross-peaks between H-7 and H-1/5, H-12 and H-22, H-13 and H-18, and H-15 and H-17. However, due to overlapping resonances within the cyclobutane region, a 1D-difference NOE experiment was performed to supplement the configuration assignment.

Upon selective irradiation of H-8 (δH 2.67), enhancements were observed for H-9 (δH 3.22), H-13 (δH 4.46), and H-2/4 (δH 7.19). Comparative 1D-difference NOE data between 1 and 1a are summarized in Table 2. Notably, compound 1 showed reciprocal NOE enhancements between H-8 and H-9, although at low intensities, which may be attributed to differences in NMR instrumentation-compound 1 being measured on a 600 MHz spectrometer, while 1a was analyzed on a 300 MHz system. Consequently, minor signal enhancements may have arisen from interactions with neighboring protons. Overall, the relative stereochemistry of compound 1 mirrors that of compound 1a, as depicted in the complete structural representation (Fig. 1B) and further supported by the three-dimensional conformational model (Fig. 1C).

1D difference NOE data of compounds 1 and 1 a

Several known compounds were also isolated and identified through spectroscopic comparisons with Literature data, including 3-caren-5-one-2-ol (2) [17], ethyl-syn-2,3-dihydroxy-3-(4-methoxyphenyl) propanoate (3) [18], ethyl-anti-2,3-dihydroxy-3-(4-methoxyphenyl) propanoate (4) [18], ethyl-4-methoxycinnamate (5) [19], 4-methoxybenzoic acid (6) [20].

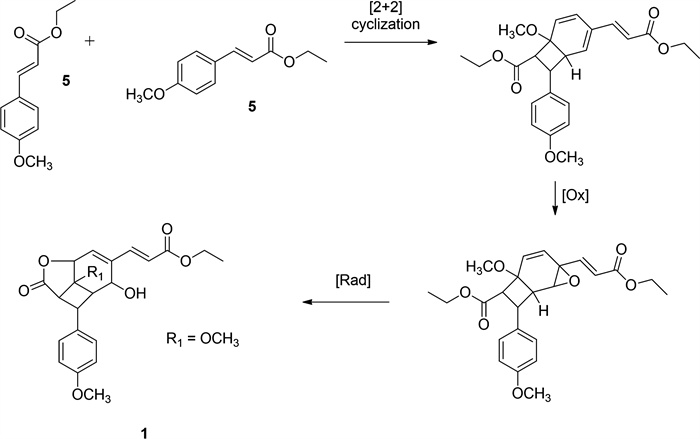

The photochemical generation of 1 a [16] provided a conceptual framework for proposing a plausible biosynthetic pathway for compound 1, a new natural product derived from K. galanga. Given that ethyl 4-methoxycinnamate is a major constituent of K. galanga, it is postulated as the precursor (Fig. 2). Exposure to natural sunlight during plant growth or post-harvest drying processes may facilitate [2 + 2] cycloaddition [21] between the trans double bond of compound 5 and the aromatic ring, followed by epoxidation and subsequent ring opening, ultimately forming the lactone through double bond migration and carboxylate conjugation. Based on its structural features and proposed biosynthesis, compound 1 can be classified as a phenylpropanoid dimer rather than a lignan, since its formation involves photochemical dimerization rather than oxidative coupling of monolignols [22].

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of 1

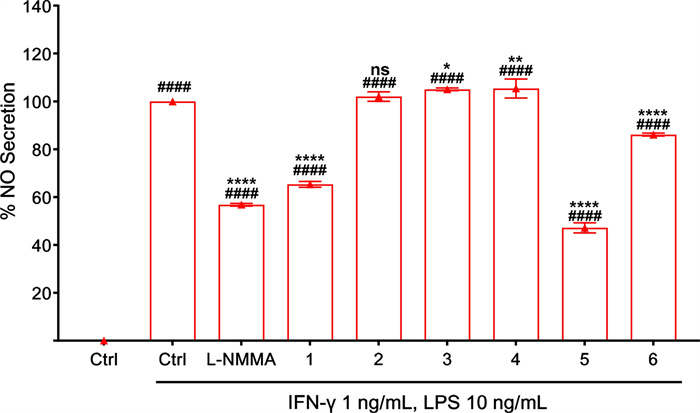

Inflammation is a vital physiological defense mechanism involving intricate networks of cellular and molecular mediators; however, its dysregulation is implicated in the onset and progression of numerous chronic diseases, highlighting the need for safe and effective anti-inflammatory therapies [23]. Among these mediators, nitric oxide (NO) plays a dual role—functioning as an anti-inflammatory agent under normal physiological conditions, but contributing to pathological inflammation when produced in excess [24]. K. galanga demonstrates potent analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects, mediated by its bioactive constituents that suppress inflammatory signaling pathways [25]. Previous studies demonstrated that ethyl 4-methoxycinnamate (5), the principal compound in K. galanga, exhibited dual COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitory activity at 1.12 µM and 0.83 µM, respectively [19]. Moreover, another reported its inhibitory activity on IL-1 and TNF-α with IC50 values of 166.4 µg/mL and 96.84 µg/mL, respectively [26]. In alignment with these reports, compound 5 in this study inhibited NO production with an IC50 of 12.2 ± 4.0 µM (Table 3). Compounds 3–4 and 5 showed notably different anti-inflammatory activities, with compound 5 being the most potent. This enhanced activity is likely due to its conjugated double bond, which may improve interaction with inflammatory targets such as iNOS. Structural features like unsaturation appear to significantly influence anti-inflammatory potency, as supported by this result. Intriguingly, the newly identified phenylpropanoid bearing cyclobutane ring, compound 1, also exhibited significant NO inhibitory activity with an IC50 of 23.1 ± 6.4 µM, suggesting promising anti-inflammatory potential (Fig. 3).

The IC50 values of isolated compounds

Effect of isolated compounds on NO secretion in RAW264.7 cells. Concentration of sample is 40 μM except for L–NMMA (100 μM). All the results are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis was conducted using one way ANOVA (Tukey’s test). Significance difference (#### p < 0.0001) compared with vehicle control group, whereas (**** p < 0.0001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05) compared with LPS treatment group

3 Conclusion

This study reports on the isolation and structural elucidation of kaemphenolide (compound 1), a cyclobutane-containing phenylpropanoid from K. galanga. The compound expands the chemical diversity of this medicinal plant and showed promising anti-inflammatory potential by inhibition of NO production (IC50 23.1 µM), supporting its traditional anti-inflammatory use. Notably, the rigid and conformationally constrained nature of the cyclobutane ring may contribute to its enhanced bioactivity. Its proposed biosynthesis via [2 + 2] cycloaddition highlights the role of photochemical processes in natural product formation. These findings indicate that K. galanga represents a promising natural source for the development of therapeutic agents targeting inflammatory disorders.

4 Experimental section

4.1 General

NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker Ascend 600 (600 MHz), HPLC was performed on a Shimadzu LC-10Advp series (pump; LC-10AD VP, Diode Array Detector (DAD); SPD-M-10A VP, Column oven; CTO-10A) and JASCO-2000 Plus series (pump; PU-2080 Plus, DAD; MD-2018 Plus, Column Oven; CO-2060 Plus). The Mass Spectra were measured by LC/MS Thermo Scientific; LC Dionex Ultimate 3000; LTQ Orbitrap Elite. Recycling preparative HPLC was performed on a Japan Analytical Industry LC-908W. The IR data was collected by FT/IR-460 plus JASCO. Organic solvents (methanol, n-hexane, ethyl acetate, chloroform, n-butanol, and dehydrated-pyridine) were purchased from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation. LC/MS grade solvent (0.1% Formic acid in acetonitrile and 0.1% Formic acid in water) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Silica gel 60 (Spherical) 100-20 μm was purchased from Kanto Chemical Co., Inc. Sephadex LH-20 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC., 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. LTD.

The dried K. galanga was purchased from Nihon Funmatsu Yakuhin Co., Ltd.

4.2 Extraction and isolation

The extraction protocol commenced with 1.48 kg of dried K. galanga rhizome powder subjected to exhaustive methanol extraction under reflux conditions (2 hours × 2 repetitions). The combined filtrates were concentrated under reduced pressure to yield 158.89 g of crude methanol extract. Subsequent fractionation involved suspending the crude extract in water followed by sequential partitioning with n-hexane and ethyl acetate, yielding two distinct fractions: an n-hexane-soluble fraction (KG-H, 94.2 g) and an ethyl acetate-soluble fraction (KG-E, 6.41 g).

The KG-H fraction underwent methanol crystallization, producing compound 5 (19.06 g) as primary crystals. The remaining filtrate (10 g) was fractionated through primary silica gel column chromatography (7 cm i.d.) using a gradient of n-hexane–ethyl acetate (started with ratio of 10% ethyl acetate continued to 100%), yielding nine subfractions (FR-1–1 to FR-1–9). Further purification of these subfractions via secondary silica gel chromatography (5 cm i.d.) with hexane–ethyl acetate gradient (started with ratio 30% of ethyl acetate continued to 60%, 80%, 100% and 30% for over 35 min) yielded FR-2–3 and FR-2–7. Final purification of FR-2–7 by reversed-phase HPLC (Waters XBridge Prep C18 column, 5 μm, 10 × 250 mm; acetonitrile–water gradient at 2.5 mL/min, 40 ℃) afforded compound 2 (0.6 mg).

The KG-E fraction was subjected to comprehensive silica gel chromatography (8 cm i.d.) using n-hexane–ethyl acetate–methanol gradient system (started with ratio of 10% to 100% of ethyl acetate and continued to 1%-10% of methanol), generating 32 fractions. Pooled fractions FR-22 to FR-25 were further resolved through silica gel chromatography (3 cm i.d.) with chloroform–methanol gradient (started from 100 to 50% of chloroform), followed by reversed-phase HPLC purification (identical column parameters with methanol–water mobile phase) to yield FR-3–2, compound 1 (4 mg), and compound 6 (2.5 mg). Final purification of FR-3–2 by normal-phase HPLC (Kanto Chemical) Mightysil Si60 column, 5 μm, 10 × 250 mm; n-hexane–ethyl acetate gradient (started with ratio 30% of ethyl acetate continued to 60%, 80%, 100% and 30% for over 35 min) at 2.5 mL/min, 40 ℃) afforded compounds 3 (47.4 mg) and 4 (4.9 mg).

4.3 Cell assay

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/200 µL per well and incubated for 2 hours at 37 ℃ in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 using SCA-165DRS (Astec Co. Ltd) CO2 Incubator. Subsequently, cells were stimulated with interferon-γ (IFN-γ, 1 ng/mL) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 10 ng/mL) in the presence of test samples dissolved in DMSO at various concentrations. The plates were further incubated for 16 hours under the same conditions. L-NG-monomethyl arginine (L-NMMA), a known inhibitor of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), served as the positive control. Following incubation, 100 µL of the culture supernatant was transferred from each well, to which 50 µL of 1% sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid and 0.1% N-1-naphthyl ethylenediamine dihydrochloride were sequentially added [27]. The mixtures were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature under Light-protected conditions. Absorbance was recorded at 550 nm with a reference wavelength of 655 nm using a xMark microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), and % NO secretion was calculated as described by Miyazawa et al. [28]. Samples exhibiting inhibitory effects on NO production were further evaluated at various concentrations to determine their IC50 values.

4.4 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10. Methods and representative symbols are described in the legends of the figures. Symbols mean significant differences from mean values of indicated numbers of independent experiments. A one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was used to compare multiple different variables between two experimental groups, respectively. For all analyses, p-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant and were indicated in the legends of the figures.

Notes

Acknowledgement

This research was generously supported by the INPEX Scholarship Foundation. The work was carried out at the Research Center for Medicinal Plant Resources, National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition (NIBN), Japan. The author sincerely thanks the supervisors, collaborators, and all staff at NIBN for their invaluable guidance, technical assistance, and support throughout the study.

Author contributions

Syarifatul Mufidah: Conceptualization, writing–review and editing, writing–original draft, Investigation, formal analysis. Yusaku Miyamae: Conceptualization, writing–review and editing. Hiroyuki Fuchino: Investigation, methodology, elucidation. Nobuo Kawahara: Resources, formal analysis.

Funding

This research was supported by INPEX Scholarship Foundation.

Data availability

Not applicable

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

-

1.Kumar A. Phytochemistry, pharmacological activities and uses of traditional medicinal plant Kaempferia galanga L.—an overview. J Ethnopharmacol 2020;253: 112667. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

2.Hashiguchi A, San M, Duangsodsri TT, Kusano Kazuo M, Watanabe N. Biofunctional properties and plant physiology of Kaempferia spp: status and trends. J Funct Foods 2022;92: 105029. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

3.Khairullah Aswin R, Sholikhah TI, Ansori ANM, Hanisia RH, Puspitarani GA, Fadholly A, et al. Medicinal importance of Kaempferia galanga L. (Zingiberaceae): a comprehensive review. J Herbmed Pharmacol 2021;10(3): 281-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

4.Sulaiman MR, Zakaria ZA, Daud IA, Ng FN, Ng YC, Hidayat MT. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of the aqueous extract of Kaempferia galanga leaves in animal models. J Nat Med 2008;62(2): 221-7. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

5.Srivastava N, Mishra S, Iqbal H, Chanda D, Shanker K. Standardization of Kaempferia galanga L. rhizome and vasorelaxation effect of its key metabolite ethyl p-methoxycinnamate. J Ethnopharmacol 2021;271: 113911. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

6.Ridtitid W, Sae-wong C, Reanmongkol W, Wongnawa M. Antinociceptive activity of the methanolic extract of Kaempferia galanga Linn. in experimental animals. J Ethnopharmacol 2008;118(2): 225-30. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

7.Liu H, Chen Y, Hu Y, Zhang W, Zhang H. Protective effects of an alcoholic extract of Kaempferia galanga L. rhizome on ethanol-induced gastric ulcer in mice. J Ethnopharmacol 2024;325: 117845. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

8.Surya R, Romulo A, Nurkolis F, Kumalawati DA . Natural products in beverages. Cham: Springer, 2025: 307-39. PubMed Google Scholar

-

9.Wang SY, Zhao H, Xu H, Han X, Wu Y. Kaempferia galanga L.: Progresses in phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicology and ethnomedicinal uses. Front Pharmacol 2021;12: 675350. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

10.Ferrer JL, Austin MB, Stewart C, Noel JP. Structure and function of enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of phenylpropanoids. Plant Physiol Biochem 2008;46(3): 356-70. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

11.Zhu Y, Chen L, Zeng J, Xu J, Hu H, He X, et al. Six new phenylpropanoids from Kaempferia galanga L. and their anti-inflammatory activity. Fitoterapia 2024;176: 106028. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

12.Yang P, Jia Q, Song S, Huang X. [2 + 2]-Cycloaddition-derived cyclobutane natural products: structural diversity, sources, bioactivities, and biomimetic syntheses. Nat Prod Rep 2023;40(6): 1094-129. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

13.Van der Kolk MR, Janssen MACH, Rutjes FPJT, Blanco-Ania D. Cyclobutanes in small-molecule drug candidates. Chem Med Chem 2022;17(9): 20. PubMed Google Scholar

-

14.Li J, Gao K, Bian M, Ding H. Recent advances in the total synthesis of cyclobutane-containing natural products. Org Chem Front 2019;7(1): 136-54. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

15.Namyslo JC, Kaufmann DE. The application of cyclobutane derivatives in organic synthesis. Chem Rev 2003;103(4): 1485-538. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

16.Schrader A, Jakupovic J, Baltes W. Photochemical reaction products of 4-methoxycinnamic acid-3′-methylbutyl ester. Tetrahedron Lett 1994;35(8): 1169-72. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

17.Yang XW, Li YL, Li SM, Shen YH, Tian JM, Zhu ZJ, et al. Mono- and sesquiterpenoids, flavonoids, lignans, and other miscellaneous compounds of Abies georgei . Planta Med 2010;77: 742-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

18.Boruwa J, Borah JC, Kalita B, Barua NC. Highly regioselective ring opening of epoxides using NaN3: a short and efficient synthesis of (−)-cytoxazone. Tetrahedron Lett 2004;45(39): 7355-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

19.Umar MI, Asmawi MZ, Sadikun A, Atangwho I, Yam M, Altaf R, et al. Bioactivity-guided isolation of ethyl-p-methoxycinnamate, an anti-inflammatory constituent, from Kaempferia galanga L. extracts. Molecules 2012;17(7): 7. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

20.Gadgoli C, Mishra SH. Antihepatotoxic activity of p-methoxy benzoic acid from Capparis spinosa . J Ethnopharmacol 1999;66(2): 187-92. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

21.Wang JS, Wu K, Yin C, Li K, Huang Y, Ruan J, et al. Cage-confined photocatalysis for wide-scope unusually selective [2 + 2] cycloaddition through visible-light triplet sensitization. Nat Commun 2020;11(1): 4675. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

22.Tiz DB, Tofani G, Vicente FA, Likozar B. Chemical synthesis of monolignols: traditional methods, recent advances, and future challenges in sustainable processes. Antioxidants 2024;13(11): 1387. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

23.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 2008;454: 7203. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

24.Bogdan C. Nitric oxide and the immune response. Nat Immunol 2001;2(10): 907-16. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

25.Othman R, Ibrahim H, Mohd MA, Awang K, Gilani AH, Mustafa MR. Vasorelaxant effects of ethyl cinnamate isolated from Kaempferia galanga on smooth muscles of the rat aorta. Planta Med 2002;68: 655-7. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

26.Umar MI, Asmawi MZ, Sadikun A, Majid AMS, Alsuede FS, Hassan LEA, et al. Ethyl-p-methoxycinnamate isolated from Kaempferia galanga inhibits inflammation by suppressing interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-α, and angiogenesis by blocking endothelial functions. Clinics 2014;69(2): 134-44. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

27.Fuchino H, Fukui N, Iida O, Wada H, Kawahara N. Inhibitory effect of black ginger (Kaempferia parviflora) constituents on nitric oxide production. J Food Chem Safety 2018;25: 152-9. PubMed Google Scholar

-

28.Miyazawa S, Sakai M, Omae Y, Ogawa Y, Shigemori H, Miyamae Y. Anti-inflammatory effect of covalent PPARγ ligands that have a hybrid structure of GW9662 and a food-derived cinnamic acid derivative. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2024;88(10): 1136-43. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© The Author(s) 2025

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.