Neuroprotective effects of chemical constituents from Nicotiana tabacum L. in Parkinson’s disease

Abstract

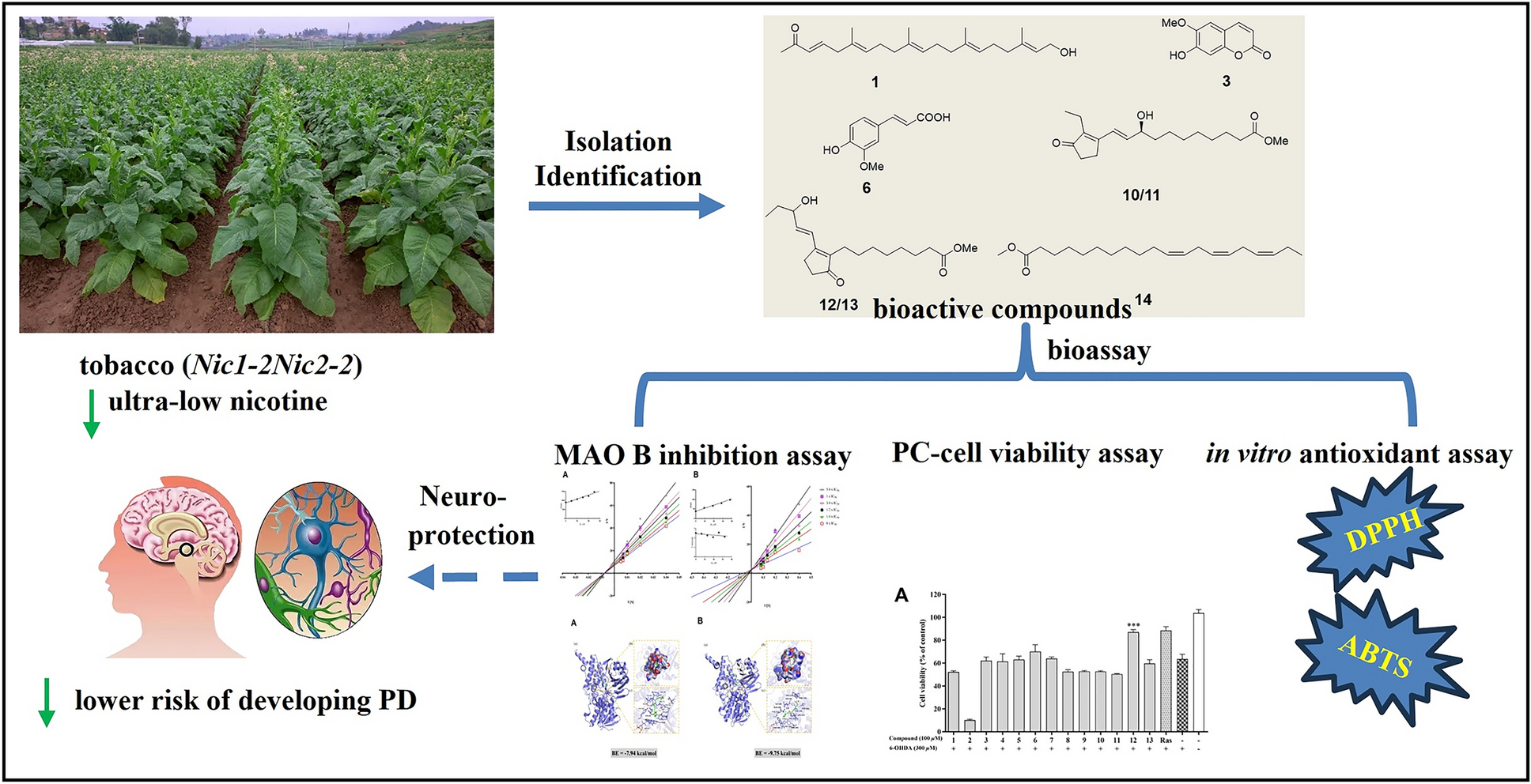

Parkinson’s disease (PD), the second most common neurodegenerative disorder globally, arises from selective dopaminergic neuron degeneration. While current therapies address symptoms, disease-modifying agents remain an unmet need. Herein, we investigated Nicotiana tabacum L. (Solanaceae), a plant linked epidemiologically to reduced PD risk, as a source of multi-target neuroprotective compounds. From ultra-low nicotine (< 0.04%) tobacco leaves, we isolated 22 molecules, including a novel 21-norsesterterpenoid (Nicotiazanorpenoid A) and eight previously unreported compounds. Systematic evaluation revealed three synergistic neuroprotective mechanisms: (1) Antioxidant activity: Scopoletin (3) and isoferulic acid (6) showed significant radical scavenging capacity (ABTS assay; IC50 = 27.74, and 18.13 μM, respectively); (2) Neuronal protection: cis-11,14,17-Eicosatrienoic acid methyl ester (14) enhanced survival (93.94% vs. control) in 6-OHDA-induced PC12 cells, surpassing rasagiline (88.36% at equivalent concentrations); (3) MAO-B inhibition: five compounds displayed selective inhibition, with scopoletin (3) exhibiting highest potency (Ki = 20.7 μM). Notably, plant prostaglandins (10/11) were identified as competitive MAO-B inhibitors first time through molecular docking and 100-ns MD simulations, revealing stable binding at the FAD site (ΔG = − 10.42, and − 9.75 kcal/mol, respectively).Graphical Abstract

Keywords

Parkinson's disease neuroprotective effects Nicotiana tabacum L 21-norditerpenoid1 Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD), a progressive neurodegenerative disorder affecting > 1% of individuals aged over 60 years worldwide [1], is characterized by the selective degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta. Notably, approximately 30% of neurons and 50–60% of axonal terminals are already lost at clinical diagnosis [2]. While current therapies (e.g., L-DOPA) provide symptomatic relief, no disease-modifying interventions exist to halt neurodegeneration [3]. This unmet need has driven extensive research into neuroprotective agents targeting PD’s multifactorial pathogenesis, including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and protein aggregation [4].

Intriguingly, epidemiological studies consistently report a reduced PD risk among tobacco users [5, 6], suggesting that Nicotiana tabacum L. (Solanaceae) may harbor bioactive compounds with neuroprotective properties. Although nicotine—the most studied tobacco alkaloid—failed to demonstrate clinical efficacy [7], the plant contains > 2500 identified metabolites [8], including terpenes, flavonoids, and cembranoid diterpenoids, some of which exhibit neuroprotective effects in vitro [9, 10]. These findings underscore the potential of non-nicotine constituents as novel therapeutic candidates.

Herein, we investigated the neuroprotective potential of low-nicotine (< 0.04%) N. tabacum extract [11] through a multi-target approach: (1) Inhibition of monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B), a key enzyme in dopamine catabolism; (2) Scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to mitigate oxidative stress; (3) Protection against 6-Hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells, a validated PD model. This study elucidates the phytochemical basis of tobacco’s putative neuroprotection and identifies promising leads for PD drug development.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Compounds from leaves of the N. tabacum.

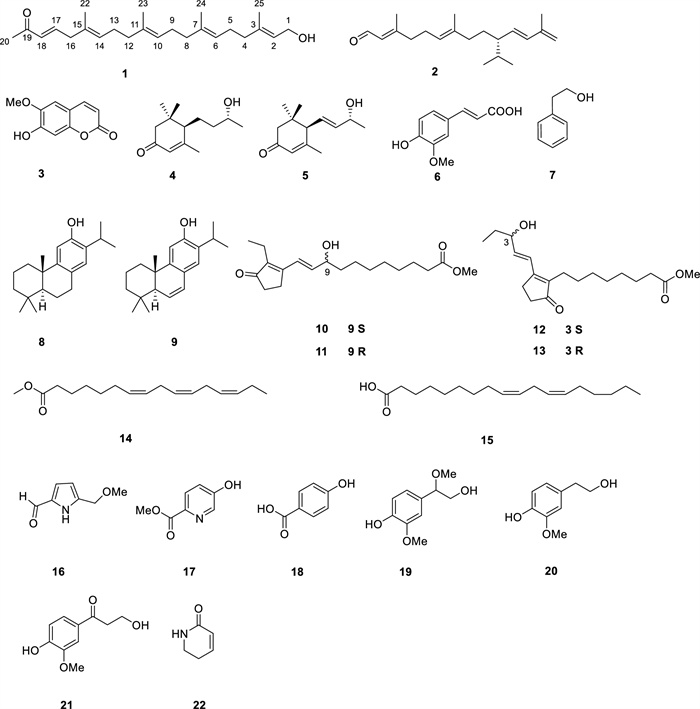

22 compounds (1–22) were isolated from N. tabacum leaves with ultra-low nicotine content, using solvent partitioning and diversified chromatography techniques, including normal, reverse, and molecular exclusion (Fig. 1). Among them, compound 1 is an undescribed 21-norsesterterpenoid, while compounds 8–14, and 19 are reported from N. tabacum for the first time.

Compounds 1–22 from the leaves of N. tabacum

Nicotiazanorpenoid A (1) was acquired as a colorless oil. Its molecular formula of C24H38O2 was deduced by HRESIMS at m/z 381.2768 [M + Na]+ ion (calcd 381.2764), indicating six degrees of unsaturation. Its IR spectrum exhibited clear absorption bands. The one at 3441 cm− 1 indicated the existence of a hydroxyl group, while the band at 1637 cm− 1 suggested an α, β-unsaturated ketone system was present. The 1H-NMR data (Table 3) showed five quaternary methyl groups (δH 1.60 (s, 6H), 1.61 (s, 3H), 1.68 (s, 3H), and 2.25 (s, 3H)), one O-bearing CH2 group (δH 4.16, 2H, J = 6.5 Hz) and six olefinic protons (δH 5.42 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, H-2, 1H), 5.19 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, H-14, 1H), 5.11 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, H-10, 1H), 5.11 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, H-6, 1H), 6.60 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, H-18, 1H), 6.76 (dt, J = 16.0, 7.0 Hz, H-14, 1H). The 13C NMR and DEPT spectra (Table 3) displayed 24 carbon signals, including one carbonyl carbon (δC 198.9), four trisubstituted and one disubstituted C = C bonds (δC 146.7 (d), 139.9 (s), 135.5 (s), 134.8 (s), 132.2 (d), 131.4 (s), 127.6 (d), 124.7 (d), 124.0 (d), and 123.5 (d)), and seven sp3 CH2 (δC 42.7, 39.9, 39.7, 39.6, 26.9, 26.8, and 26.4). Besides the six degrees of unsaturation provided by five double bonds and one carbonyl group, the lack of any extra degrees of unsaturation indicates that compound 1 probably has a linear structure.

MAO-B inhibitory activities of compounds 1–22 and positive control

Antioxidant activities of compounds and positive control

1H (500 MHz) and 13C (125 MHz) NMR data of compound 1 in CDCl3

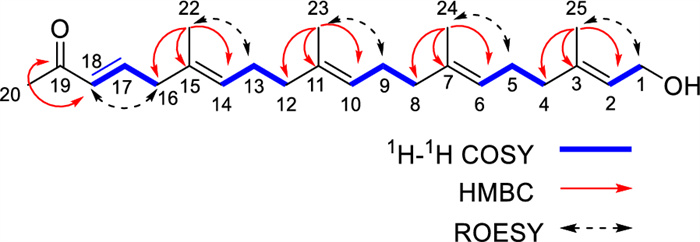

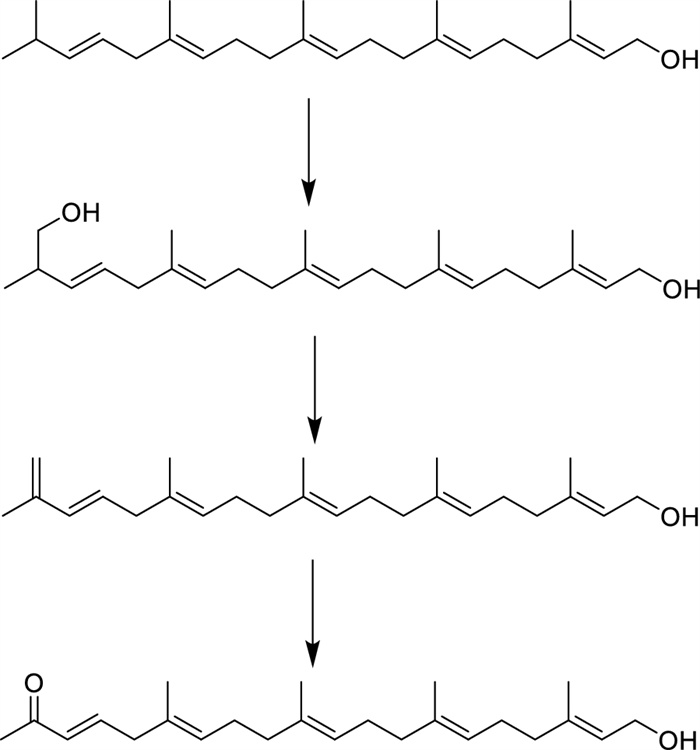

The detailed analysis of the 1H–1H COSY and HMQC correlations revealed five spin systems (C-1–C-2, C-4–C-5–C-6, C-8–C-9–C-10, C-12–C-13–C-14, and C-16–C-17–C-18) in compound 1 as shown in bold in Fig. 2. The key HMBCs from H3-22 to C-14/C-15/C-16, from H3-23 to C-10/C-11/C-12, from H3-24 to C-6/C-7/C-8, from H3-25 to C-2/C-3/C-4, and from H-20 to C-18/C-19, determined the planar structure of 1. The geometries of C = C bonds were established as (3E), (6E), (10E), (14E), and (18E) deduced from the ROESY correlations of H-18/H2-16, H3-22/H2-13, H3-23/H2-12, H3-24/H2-5, and H3-25/H2-1. Structurally, nicotiazanorpenoid A should be a linear 21-norsesterterpenoid. Herein, we propose a putative biogenetic pathway for 1 as shown in Fig. 3.

The 1H-1H COSY, HMBC and ROESY correlations of compound 1

The proposed biogenetic pathway of nicotiazanarpenoid A (1)

Through the comparison of their experimental findings with existing literature data, 21 known compounds were recognized as 2,6,11,13-tetradecatetraenal-3,7,13-trimethyl-10-(1-methylethyl) (2) [12], scopoletin (3) [13], blumenol C (4) [14], (6R,9S)-3-oxo-α-ionol (5) [15], isoferulic acid (6) [16], 2-phenylethanol (7) [17], ferruginol (8) [18], 6,7-dehydroferruginol (9) [19], phytoprostanes B1 type Ⅱ (10/11), phytoprostanes B1 type Ⅰ (12/13) [20], Methyl (7Z,10Z,13Z)-7,10,13-hexadecatrienoate (14) [21], linolic acid (15) [21], 5-(methoxymethyl)-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde (16) [22], methyl 5-hydroxypicolinate (17) [23], paraben-acid (18) [24], 4-hydroxy-β,3-dimethoxybenzeneethanol (19), homovanillic alcohol (20) [25], β-hydroxypropiovanillone (21) [26], and 5,6-dihydropyridin-2(1H)-one (22) [27].

2.2 Bioactivity of compounds from the N. tabacum

2.2.1 MAO-B inhibitory activity

Although MAO-B inhibitors, such as safinamide, rasagiline, and selegiline [28], have not been demonstrated to alter PD course [29], MAO-B inhibitors may contribute to reduce PD risk. Therefore, 22 compounds were first selected and tested for their MAO-B inhibitory activity in this work. The preliminary screening results were summarized in Table 1, in which five compounds (3, 6, 10/11, 12/13 and 14) exhibited inhibition rates above 30% at a concentration of 50 μM, with compounds 3 and 10/11 showing the most substantial effect of around 60%. Further, these compounds were tested for their IC50 values against MAO-B through dose–response relationships (Table 1). Compared with the positive control (0.15 ± 0.01 μM), IC50 values of compounds 3 and 10/11 were 40.17 ± 1.21 and 37.70 ± 1.57 μM, respectively, and the others ranged from 141.92 to 201.10 μM. This study represents the initial report on the MAO-B inhibitory activity of compounds 10–13 derived from N. tabacum, which provides a preliminary explanation of the chemical basis of the anti-PD effects of the N. tabacum.

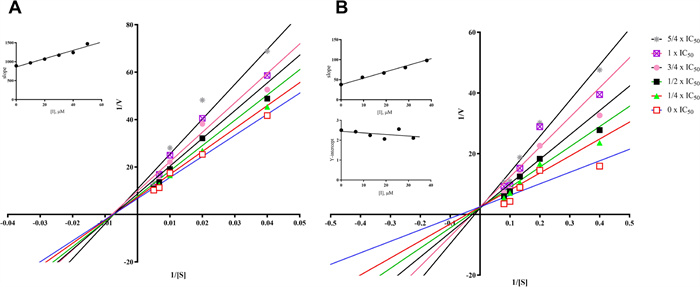

2.2.2 Enzyme kinetic studies

Lineweaver–Burk plots were constructed to explore the inhibition mechanism of compounds 3 and 10/11 against MAO-B, as illustrated in Fig. 4. In Fig. 4a, the Lineweaver–Burk plots presented six straight lines intersecting at the X-axis. This phenomenon implies that compound 3 acts as a non-competitive inhibitor of MAO-B. Its Ki value, signifying the equilibrium dissociation constant for inhibitor-enzyme binding, was measured at 78.75 μM.

Lineweaver–Burk plots of compounds 3 (A) and 10/11 (B) against MAO B. (Insets) Replots of the slope and Y-intercept of the Lineweaver–Burk plots versus the inhibitor concentration

Shifting to Fig. 4b, the Lineweaver–Burk plots for compounds 10/11 showed six straight lines intersecting at the Y-axis. This finding indicates a competitive inhibition mechanism against MAO-B, meaning compounds 10/11 compete with substrates for the enzyme's active sites. The Ki value (equilibrium constant for inhibitor-enzyme binding) for compounds 10/11 was 23.16 μM, while the Kis value (equilibrium constant for inhibitor-substrate-enzyme complex binding) was 310.60 μM. These values suggest that compounds 10/11 have a greater affinity for the free enzyme than for the substrate-enzyme complex.

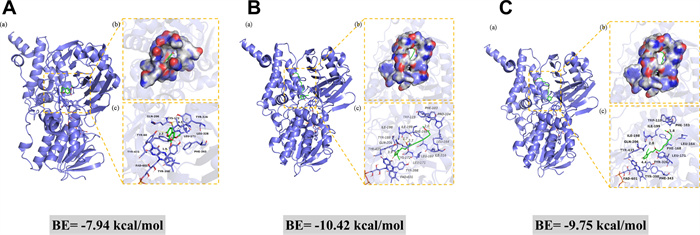

2.2.3 Docking studies

The computational binding modes in 2D and 3D between compounds (3, 10, and 11) and MAO-B are depicted in Fig. 5. As shown in Fig. 5a, compound 3 forms strong hydrogen bonds with the amino acid residues of Tyr-60 and cofactor FAD-601, and Tyr-326 interacts with the benzene ring of compound 3 through π-π interaction. In Fig. 5b, c, compound 10 exhibits strong hydrogen-bonding with the amino acid residues Trp-119, Ile-198, and Gln-206. The measured hydrogen-bond distances are 2.0 Å, 1.7 Å, and 2.7 Å, respectively, all of which are shorter than the typical 3.5 Å for a hydrogen bond. Besides, compound 10 engages in hydrophobic interactions with several amino acid residues, such as Leu-164, Phe-168, Leu-171, Tyr-326, and Phe-343. Compound 11 interacts with the amino acid residues of Tyr-119 and Ile-199 by hydrogen bonds with the hydrogen bond distances of 2.0 Å and 1.8 Å, respectively. Moreover, compound 11 can form hydrophobic interactions with multiple amino acid residues (ie. Leu-164, Leu-167, Phe-168, Leu-171, Tyr-188, and Ile-316). Both compounds 10 and 11 form π-π conjugation with Tyr-435. The lowest binding energies between 3, 10, and 11 to MAO-B were calculated to be − 7.94, − 10.42, and − 9.75 kcal/mol, respectively, which were consistent with their good MAO-B inhibitory activity. The binding energy of 10 is slightly lower than compound 11, revealing the binding effect between compound 10 and MAO-B is more stable, which may be attributed to compound 10 forming more hydrogen bonds with MAO-B, and it is well-established that hydrogen bonds can enhance binding specificity and reduce binding energy [30, 31].

Molecular docking of compounds 3 (A), 10 (B), and 11 (C) with MAO-B. a The 3D structure of the complex. b The electrostatic surface of the protein. c The 3D detail binding mode of the complex. Yellow and gray dash represents hydrogen bond distance or π-stacking

2.2.4 Molecular simulation studies

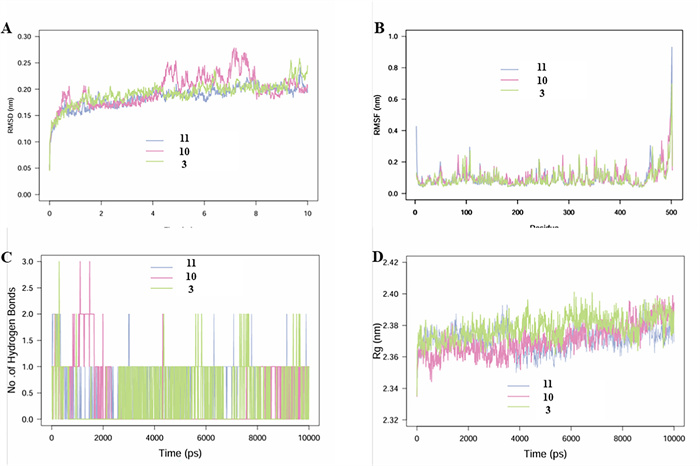

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were primarily conducted to investigate the complexes formed between the MAO-B protein and compounds 3, 10, and 11 (Fig. 6). Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis revealed that the fluctuations in binding between the three compounds and MAO-B were relatively minor, with the catalytic site remaining stable. Root mean square deviation (RMSD) analysis indicated that the complexes of MAO-B with compounds 3 and 11 exhibited more stable RMSD values, suggesting superior binding efficacy. Although hydrogen bond analysis showed that compound 3 occasionally forms three hydrogen bonds during certain intervals (compared to two for compound 11), the cumulative count of hydrogen bonds for compound 11 (738) significantly exceeded that of compound 3 (411). This comprehensive evidence demonstrates that compound 11 exhibits the most stable and effective binding among the three compounds.

MD simulation analysis of 100 ns trajectories of A RMSD of MAO-B bound to ligands CAP. WA. B RMSF of MAO-B bound to ligands compounds 3, 10, and 11. C Formation of hydrogen bonds in of MAO-B bound to ligand compounds 3, 10, and 11. D Rg of MAO-B bound to ligand compounds 3, 10, and 11

2.2.5 Neuroprotective effects of compounds in 6-OHDA-induced PC12 cells

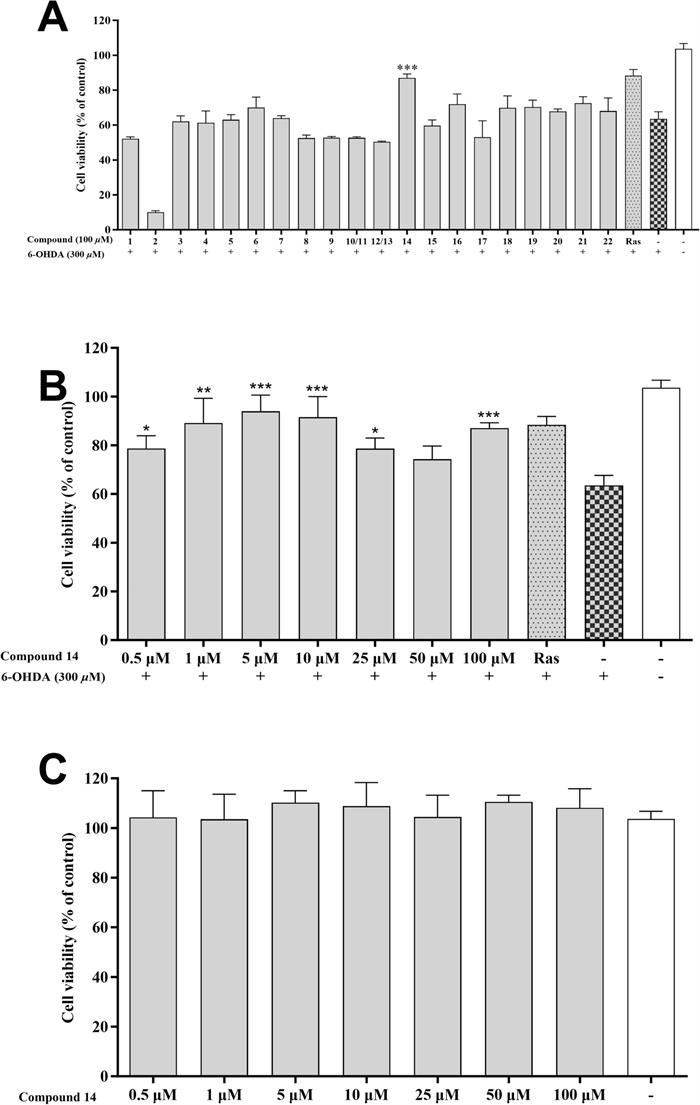

The neuroprotective activities of compounds 1–22 were further assessed in 6-OHDA-induced PC12 cells. The 6-OHDA is a neurotoxin capable of inducing the death of dopaminergic neurons. It has been extensively utilized to explore the mechanisms underlying PD [32]. Rasagiline has demonstrated effectiveness in protecting against various dopaminergic toxins such as 6-OHDA, MPP+, and β-amyloid. Therefore, it is often utilized as a positive control in this cellular model [33, 34]. In the preliminary screen (Fig. 7a), compound 14 at 100 μM exhibited an obvious protective effect with cell viability of 87.08%, compared to 63.58% of the model group. Additionally, various concentrations of compound 14 (0.5–100 μM) were tested. As shown in Fig. 7b, 14 enhanced cell viability across all tested concentrations, except 50 μM, and the best concentration was 5 μM (93.94%) in which the cell viability was even higher than that of the rasagiline (88.36%). Furthermore, in the cytotoxicity experiment (Fig. 7c), compound 14 demonstrated extremely low cytotoxicity at different concentrations (0.5–100 μM).

Neuroprotective effects of the isolated compounds against 6-OHDA-induced injury in PC12 cells. A Neuroprotective effect of the compounds 1–22 at 100 μM. B Neuroprotective effect of compound 14 at various concentrations (0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 μM). C Cytotoxic effect of compound 14 (0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 μM) on PC12 cell. Data were expressed as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 compared with model cells in (A, B) and compared with control cells in (C). Rasagiline (Ras) was used as a positive control

2.2.6 Antioxidative activity

The antioxidative activity of the isolated compounds was gauged through DPPH and ABTS assays, with ascorbic acid serving as the positive control. Table 2 shows that among all the isolated compounds, only compound 6 demonstrated DPPH radical scavenging ability, achieving an IC50 value of 151.65 ± 1.75 μM. In the ABTS assay, compounds 3, 6, 19, 20, and 21 exhibited robust radical scavenging capabilities. Their IC50 values were 27.74 ± 1.20 μM, 18.13 ± 2.49 μM, 84.06 ± 0.76 μM, 60.51 ± 1.18 μM, and 348.3 ± 17.53 μM respectively. For comparison, ascorbic acid had an IC50 of 14.46 ± 0.03 μM in this assay.

These findings indicate that the antioxidative properties of these compounds might be the source of their neuroprotective effects, which warrants further exploration.

3 Discussion

This study reveals the low-polarity chemical profile of nicotine-ultra-low N. tabacum, and its multi-target neuroprotective models by integrating phytochemical and pharmacological approaches. Among the 22 compounds identified, Nictiazanorpenoid A (1) represents the first 21-norsesterterpenoid found in the Solanaceae family, while eight ones were discovered in N. tabacum for the first time. Additionally, five compounds show inhibitory activity against MAO-B, two possess anti-oxidative properties in the ABTS radical scavenging assay, and one performs good neuroprotective activity to PC-12 cells effectively against 6-OHDA-induced cytotoxicity. Notably, we demonstrate for the first time that plant prostaglandins, which were previously recognized solely for their defensive functions [35], exhibit moderate MAO-B inhibition activity. Their activities suggest that these compounds could serve as valuable chemical probes for structure–activity relationship studies. Moreover, their natural origin makes them particularly interesting for investigating plant-derived neuromodulators. The most abundant scopoletin (3), exhibited selective (and reversible) inhibition of human (Ki = 20.7 μM) and murine (Ki = 22 μM) MAO-B, demonstrating approximately 3.5-fold selectivity for MAO-B over MAO-A. In vivo, intraperitoneal administration of scopoletin (3) (80 mg/kg) significantly elevated dopamine levels while reducing the striatal metabolite 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) in treated subjects [36]. Additionally, compound 14 exhibited superior neuroprotective effects, potentially mediated by synergistic activation of the Nrf2/ARE signalling pathway and inhibition of oxidative stress. It was previously reported that some similar compounds (such as DHA) might have similar activities. [37]. Importantly, the anti-PD compounds identified in this study provide a new platform for producing plant-derived multi-target neuroprotectants, potentially solving the single-target MAO-B inhibitory tolerance issue. The synergistic compound system within N. tabacum extracts may achieve sustained therapeutic efficacy.

4 Conclusion

In this study, a systematic separation and identification of the low-polarity chemical components of ultra-low-nicotine N. tabacum was conducted. 22 compounds were isolated and identified, including the first discovery of a new linear 21-norsesterterpenoid. Additionally, through various activity evaluation models, five compounds with MAO-B inhibitory activity, one compound with neuroprotective activity, and two compounds with ABTS radical scavenging activity were discovered in the N. tabacum These findings suggest that N. tabacum harbours multiple neuroprotective activities, including MAO-B inhibition and antioxidative effects, which may contribute to reducing the risk of Parkinson’s disease and potentially other neurodegenerative disorders.

5 Materials and methods

5.1 Plant materials

The ultra-low nicotine N. tabacum was provided by Dr. Xue-Yi Sui [11].

5.2 General experimental procedures

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra, including 1H, 13C, DEPT, 1H-1H COSY, HSQC, HMBC, and ROESY, were recorded using a Bruker Avance Ⅲ 500 spectrometer (Bruker, Zurich, Switzerland), employing tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard. Infrared (IR) measurements were obtained with a Bruker Tensor-27 spectrometer (Bruker, Germany). High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HRESIMS) analyses were conducted on an Agilent Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Agilent, Redwood City, CA, USA). Ultraviolet (UV) data was collected using a thermal multimode microplate reader (Waltham, MA, USA). Column chromatography was carried out using MCI gel (CHP-20P, Mitsubishi Chemical Industries Co., Ltd., Japan), silica gel (200-300 mesh, Qingdao Marine Chemical Plant, Qingdao, China), and reversed-phase C18 silica gel (YMC Group). Analytical high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on Waters 2695 (Waters Associates, Massachusetts, USA) and Shimadzu LC-20 (Shimadzu, Japan) HPLC systems. The MAO-B inhibition assay was conducted by a Thermo Scientific Varioskan Flash (Waltham, MA, USA). The instruments, reagents, and general experimental procedures used in this study were the same as those detailed in our previous reports [38, 39].

5.3 Extraction and isolation

The dried leaves of the N. tabacum were ground into a powder weighing 28 kg. This powder underwent extraction three times with 50 L of methanol at ambient temperature. After extraction, the filtrates from each round were combined and evaporated under reduced pressure, resulting in 10 kg of extract. The extract was processed using silica gel column chromatography (CC) with CH2Cl2/MeOH eluent (1:0, 500:1, 200:1, 50:1, 20:1, 5:1, 0:1, v/v), producing seven distinct fractions (Fr. 1–Fr. 7).

Fr. 3, with a mass of 146.4 g, was further partitioned using MCI gel CC employing a MeOH/H2O eluent (from 3:10 to 1:0, v/v), producing eight subfractions (Fr. 3.1–Fr. 3.8). Sub-fraction Fr. 3.6 (5.6 g) underwent chromatographic separation on Sephadex LH-20 with a mobile phase CH2Cl2/MeOH (1:1) and then purified by semi-preparative HPLC using MeCN/H2O (6:10, v/v, 2 mL/min). This procedure resulted in the isolation of compounds 8 (8.6 mg, tR 23 min), 9 (4.3 mg, tR 28 min), and 22 (12.3 mg, tR 32 min).

Compound 3 was directly crystallized from Fr. 4. The supernatant of Fr. 4, weighing 455.7 g, was further fractionated using MCI gel CC with MeOH/H2O (from 3:10 to 1:0, v/v), giving eight fractions (Fr. 4.1–Fr. 4.8). Sub-fraction Fr. 4.4 was partitioned using Sephadex LH-20 with MeOH and then further purified by semi-preparative HPLC with a solvent system of n-Hexane/isopropanol (1:10, v/v, 2 mL/min), yielding compounds 4 (8.4 mg, tR 18 min) and 5 (5.5 mg, tR 19 min). Subfraction Fr. 4.6 was chromatographed on silica gel CC with CH2Cl2/MeOH (from 200:1 to 0:1, v/v), resulting in eight subfractions (Fr. 4.6.1–Fr. 4.6.8). Fr. 4.6.4 was fractionated on Sephadex LH-20 (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 1:1, v/v) and then purified by semi-preparative HPLC with MeCN/H2O (30:70, v/v, 2 mL/min), yielding compounds 1 (5.6 mg, tR 15 min), 14 (6.5 mg, tR 21 min), and 15 (11.1 mg, tR 8 min).

Fr. 5, weighing 137.0 g, was further fractionated into five subfractions (Fr. 5.1–Fr. 5.5) using MCI gel CC with MeOH/H2O (from 6:10 to 1:0, v/v). The subfraction Fr. 5.2, weighing 12.6 g, was first purified by silica gel CC with CH2Cl2/MeOH (20:1, v/v) and then by semi-preparative HPLC with MeCN/H2O (6:10, v/v, 2 mL/min). This purification process led to the isolation of compounds 2 (23.0 mg, tR 45 min), 6 (32.6 mg, tR 26 min), 7 (30.6 mg, tR 18 min), 10/11 (2.6 mg, tR 22 min), 12/13 (2.5 mg, tR 24 min), 16 (8.9 mg, tR 23 min), 17 (5.2 mg, tR 25 min), 18 (3.3 mg, tR 20 min), 19 (12.6 mg, tR 28 min), 20 (15.6 mg, tR 32 min), and 21 (2.0 mg, tR 35 min).

5.3.1 Nicotiazanorpenoid A (1)

Colorless oil; IR (KBr) νmax 3446, 3437, 2959, 2921, 2853, 1637, 1543, 1456, 1435, 1420, 1384, 1316, 1261, 1164, 1095, 1047, 1030, 877, 860, 800, 675, 661, 619, and 421 cm− 1; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 196 (0.50) nm; 1H and 13C NMR (CDCl3) spectra data see Table 3; HRESIMS: m/z 381.2768 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C24H38O2Na, 381.2764).

5.4 MAO-B assays

The MAO-B inhibition assay was performed on 96-well microtiter plates according to the procedure detailed in our prior report [40]. In preparing the microplates, 50 μL of MAO-B (2.5 U/mL) was combined with 100 μL of the test compounds at different concentrations. This mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. DMSO was the negative control, while safinamide was the positive control. Next, 50 μL of kynuramine (0.2 mM) sourced from Macklin in Shanghai, China, was added to the mixture. The resulting mixture was incubated at 37 °C for an additional 30 min. The reaction was halted by adding 80 μL of 2 N NaOH. Ultimately, the enzyme activity was measured using a microplate reader, with the excitation and emission wavelengths set at 310 nm and 400 nm, respectively.

5.5 Kinetic studies of MAO-B inhibition

The kinetic study of MAO-B inhibition was the Lineweaver–Burk plot, which was performed using the Lineweaver–Burk curve method. Compounds 3 and 10/11 with six different concentrations (0, 1/4 × IC50, 1/2 × IC50, 3/4 × IC50, 1 × IC50, and 5/4 × IC50) were added into the assay solution with a series of increasing concentrations of kynuramine. Kinetic characterization of their MAO-B inhibition was recorded 20 min after initiation. Constants Kis and Ki were calculated using the Lineweaver–Burk plots.

5.6 Docking studies

Docking studies were performed to explore the interactions between compounds 3 and 10/11 with MAO-B [41]. Among them, compounds 10 and 11 are a pair of enantiomers. Compounds 3, 10 and 11 were constructed in ChemDraw 4.5, and their three-dimensional (3D) structures were optimized by Chem3D 4.5 for molecular energy minimization using the MM2 force field. Structural data for MAO-B (PDB ID: 6YT2) was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/structure). Molecular docking was conducted using the Glide functionalities within Schrödinger Maestro software.

5.7 Molecular simulation studies

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using Desmond 2020.1 (Schrödinger) to investigate the interactions of compounds 3, 10, and 11 with MAO-B [42]. The OPLS-2005 force field and TIP3P explicit solvent model were applied within a periodic boundary solvation box (10 × 10 × 10 Å). Protein–ligand complexes underwent structural optimization and energy minimization via the Protein Preparation Wizard, followed by system assembly using the System Builder tool. Equilibration involved a 10 ns NVT ensemble phase for conformational stabilization and a subsequent 12 ns NPT ensemble phase for pressure–temperature equilibration, with temperature (300 K) and pressure (1 atm) regulated by the Nose–Hoover thermostat. Long-range electrostatic interactions were computed using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method (9 Å cutoff), while pressure control employed the Martyna-Tuckerman-Klein scheme with a 2-fs timestep. A 100 ns production simulation was conducted, with system stability assessed through root mean square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration (Rg), residue-specific root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), and hydrogen bond occupancy analysis, enabling comprehensive evaluation of ligand binding dynamics and structural integrity.

5.8 Cell viability assays

Two-dimensional (2D) cell culture models were used for performing cell viability assays [38]. Approximately 10,000 PC12 cells (Fenghui, Changsha, China) were seeded into each well of a 96-well plate. The cells underwent pre-treatment with the test compounds for 2 h at 37 °C. After this pre-treatment step, the cells were subjected to 300 μM 6-OHDA (Aladdin, Shanghai, China) for 24 h. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h after adding 10 μL of CCK-8 solution (ProteinTech, Chicago, USA) to each well. Then, each well's optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm using a multimode microplate reader (Waltham, MA, USA).

5.9 Antioxidative activity

The antioxidative capacity of the obtained compounds was carried out through DPPH radical scavenging assays and ABTS assay (Macklin, Shanghai, China) with some modifications, and Vitamin C was used as the positive control [43,44,45]. In the DPPH assay, 60 μL of the isolates at varying concentrations were mixed with 100 μL of 100 μM DPPH solution in ethanol in a 96-well microplate. The mixture was shaken for 10 s and then allowed to sit in darkness at 30 °C for 5 min. Subsequently, the absorbance was determined using a microplate reader at a wavelength of 517 nm. The radical-scavenging activity of the compounds was assessed using the formula RSA (%) = [(AB-AA)/AB] × 100%, where AA was the absorbance of the sample and AB was the absorbance of the blank sample. The IC50 value was calculated with GraphPad Prism 7.0, and all experiments were conducted in triplicate.

In the ABTS+ assay, the ABTS solution was diluted using 95% methanol until it had an absorbance of 0.7 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. Various concentrations of the compounds (60 μL each) were then combined with 150 μL of the diluted ABTS+ solution. The reaction was maintained in the dark at 30 °C for 6 min. Afterwards, the absorbance was determined at 734 nm with a microplate reader. The calculation of ABTS radical scavenging activity followed the same method as for DPPH radical scavenging activity. IC50 values were determined using GraphPad Prism 7.0, and all tests were conducted in triplicate.

5.10 Chromatographic and mass spectrometric conditions

The dried leaves of the flue-cured Yunyan 87 and Nic1-2Nic2-2 were freeze-dried and subjected to ultra-fine grinding. 10.0 g aliquot of the N. tabacum leaf powder was accurately weighed, and methanol solvent was added at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:5 (w/v). Ultrasonic-assisted extraction was performed for 30 min per cycle. After filtration through a membrane filter, the extraction process was repeated three times. The three extracts were combined and concentrated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator to obtain the methanolic extract paste.

The chromatographic column was Luna Omega 3 μm Polar C18 100 Å 100 × 2.1 mm. The flow rate was 0.3 ml/min, the column temperature was 25 °C, the injection volume was 1 μL, the mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid water, and the mobile phase B was acetonitrile. The gradient elution conditions were as follows: 0–15 min (5–95% B), 15–20 min (95% B), 20–25 min (95–5% B), 25–30 min (5% B).

The mass spectrometry conditions were as follows: electrospray ionization source (ESI) positive ion mode, de-custering potential (DP): 80 V; collision energy (CE): 40 ± 10 eV; curtain gas (CUR): 35 psi; ion source gas 1 (GS1): 55 psi; ion source gas 2 (GS2): 55 psi; ion source temperature: 500 °C; ion spray voltage floating (SVF): 5500; primary scan mode: Full MS; scan range: 100–2000 m/z; secondary scan mode: Full MS/dd-MS2; scan range: 50–2000 m/z.

5.11 Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate statistical significance, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test, and data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software. The levels of significance are represented as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, and ***p < 0.0001.

Notes

Acknowledgement

We thank the analytical group of the State Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Plant Resources in West China, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for all spectroscopic analyses.

Author contributions

Hao-Jing Zang: Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Visualization. Xiao-Lin Bai: Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Visualization. Xue-Yi Sui: Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Methodology. Xiao-Rui Zhai: Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation. Yong-Cui Wang: Validation, Investigation. Zhong-Quan Xin: Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. Qiu-Yuan Ying Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing, Methodology. Xiao-Jiang Hao Supervision, Conceptualization, writing—review and editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Yue-Hu Wang Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing. Xun Liao: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing, Project administration. Ying-Tong Di: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This work was supported by the Project of YATAS (2022530000241012), Yunnan Characteristic Plant Screening and R&D Service CXO Platform (2022YKZY001), Key Research and Development Project of Yunnan Prov- ince (202203AC100009), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82293683), and the Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department (202003AD150012 to Xiao-Jiang Hao, 202201AS070040 and 202302AA310035 to Ying-Tong Di).

Data availability

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online supporting information.

Declarations

Institutional review board statement

Not applicable.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

-

1.Cramb KM, Beccano KD, Cragg SJ, Wade-Martins R. Impaired dopamine release in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2023;146(8): 3117-32. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

2.Cheng HC, Ulane CM, Burke RE. Clinical progression in Parkinson disease and the neurobiology of axons. Ann Neurol 2010;67(6): 715-25. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

3.Bonam SR, Tranchant C, Muller S. Autophagy-lysosomal pathway as potential therapeutic target in Parkinson’s disease. Cells 2021;10(12): 3547. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

4.Teleanu DM, Niculescu AG, Lungu II, Radu CI, Vladâcenco O, Roza E, Costăchescu B, Grumezescu AM, Teleanu RI. An overview of oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23(11): 5938. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

5.Hernán MA, Takkouche B, Caamaño-Isorna F, Gestal-Otero JJ. A meta-analysis of coffee drinking, cigarette smoking, and the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 2002;52(3): 276-84. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

6.Ritz B, Ascherio A, Checkoway H, Marder KS, Nelson LM, Rocca WA, Ross GW, Strickland D, Van Den Eeden SK, Gorell J. Pooled analysis of tobacco use and risk of Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 2007;64(7): 990-7. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

7.Wittenberg RE, Wolfman SL, De Biasi M, Dani JA. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotine addiction: a brief introduction. Neuropharmacology 2020;177: 108256. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

8.Gui Z, Yuan X, Yang J, Du Y, Zhang P. An updated review on chemical constituents from Nicotiana tabacum L.: chemical diversity and pharmacological properties. Ind Crops Prod 2024;214: 118497. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

9.Gallo V, Vineis P, Cancellieri M, Chiodini P, Barker RA, Brayne C, Pearce N, Vermeulen R, Panico S, Bueno-de-Mesquita B. Exploring causality of the association between smoking and Parkinson’s disease. Int J Epidemiol 2019;48(3): 912-25. PubMed Google Scholar

-

10.Yan N, Du Y, Liu X, Zhang H, Liu Y, Zhang Z. A review on bioactivities of tobacco cembranoid diterpenes. Biomolecules 2019;9(1): 30. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

11.Song Z, Wang R, Zhang H, Tong Z, Yuan C, Li Y, Huang C, Zhao L, Wang Y, Di Y. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals nicotine metabolism is a critical component for enhancing stress response intensity of innate immunity system in tobacco. Front Plant Sci 2024;15: 1338169. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

12.Courtney J, McDonald S. A new C20 α, β-unsaturated aldehyde (3, 7, 13-trimethyl-10-isopropyl-2, 6, 11, 13-tetradecatetraen-1-al)(Ⅰ) from tobacco. Tetrahedron Lett 1967;8(5): 459-66. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

13.Cai X, Yang J, Zhou J, Lu W, Hu C, Gu Z, Huo J, Wang X, Cao P. Synthesis and biological evaluation of scopoletin derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem 2013;21(1): 84-92. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

14.Matsunami K, Otsuka H, Takeda Y. Structural revisions of blumenol C glucoside and byzantionoside B. Chem Pharm Bull 2010;58(3): 438-41. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

15.Habib-Ur-Rehman, Arfan M, Atta-Ur-Rahman, Choudhary M, Khan A. Chemical constituents of Taxus wallichiana Zucc. J Chem Soc Pak 2003;25(4): 337-40. PubMed Google Scholar

-

16.Prachayasittikul S, Suphapong S, Worachartcheewan A, Lawung R, Ruchirawat S, Prachayasittikul V. Bioactive metabolites from Spilanthes acmella Murr. Molecules 2009;14(2): 850-67. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

17.De Almeida RN, Motta SC, de Brito Faturi C, Catallani B, Leite JR. Anxiolytic-like effects of rose oil inhalation on the elevated plus-maze test in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2004;77(2): 361-4. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

18.Ryu YB, Jeong HJ, Kim JH, Kim YM, Park J-Y, Kim D, Naguyen TTH, Park S-J, Chang JS, Park KH. Biflavonoids from Torreya nucifera displaying SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibition. Bioorg Med Chem 2010;18(22): 7940-7. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

19.Bredenberg JB-S. Ferruginol and Δ9-dehydroferruginol. Acta Chem Scand 1957;11: 932-5. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

20.El Fangour S, Guy A, Vidal J-P, Rossi J-C, Durand T. A flexible synthesis of the phytoprostanes B1 type Ⅰ and Ⅱ. J Org Chem 2005;70(3): 989-97. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

21.Gunstone F, Pollard M, Scrimgeour C, Vedanayagam H. Fatty acids. Part 50. 13C nuclear magnetic resonance studies of olefinic fatty acids and esters. Chem Phys Lipids 1977;18(1): 115-29. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

22.Don M, Shen C, Lin Y, Syu W, Ding Y, Sun C. Nitrogen-containing compounds from Salvia m iltiorrhiza. J Nat Prod 2005;68(7): 1066-70. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

23.Wu B, Lin W, Gao H. Antibacterial constituents of Senecio cannabifolius (Ⅱ). Chin Tradit Herb Drugs 2005;36(10): 1447. PubMed Google Scholar

-

24.Zheng Y, Chen B, Ye P, Feng K, Wang W, Meng Q, Wu L, Tung C. Photocatalytic hydrogen-evolution cross-couplings: benzene C-H amination and hydroxylation. J Am Chem Soc 2016;138(32): 10080-3. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

25.Deffieux D, Gossart P, Quideau S. Facile and sustainable synthesis of the natural antioxidant hydroxytyrosol. Tetrahedron Lett 2014;55(15): 2455-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

26.Lancefield CS, Ojo OS, Tran F, Westwood NJ. Isolation of functionalized phenolic monomers through selective oxidation and C∙ O bond cleavage of the β-O-4 linkages in lignin. Angew Chem 2015;127(1): 260-4. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

27.Barcelos RC, Pastre JC, Vendramini-Costa DB, Caixeta V, Longato GB, Monteiro PA, de Carvalho JE, Pilli RA. Design and synthesis of N-acylated Aza-goniothalamin derivatives and evaluation of their in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity. ChemMedChem 2014;9(12): 2725-43. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

28.Yeung AWK, Georgieva MG, Atanasov AG, Tzvetkov NT. Monoamine oxidases (MAOs) as privileged molecular targets in neuroscience: research literature analysis. Front Mol Neurosci 2019;12: 143. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

29.Zuzuárregui JRP, During EH. Sleep issues in Parkinson’s disease and their management. Neurotherapeutics 2020;17(4): 1480-94. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

30.Zhang H, Lin X, Wei Y, Zhang H, Liao L, Wu H, Pan Y, Wu X. Validation of deep learning-based DFCNN in extremely large-scale virtual screening and application in trypsin I protease inhibitor discovery. Front Mol Biosci 2022;9: 872086. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

31.Dain Md Opo F, Alsaiari AA, Rahman Molla MH, Ahmed Sumon MA, Yaghmour KA, Ahammad F, Mohammad F, Simal-Gandara J. Identification of novel natural drug candidates against BRAF mutated carcinoma; an integrative in-silico structure-based pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening process. Front Chem 2022;10: 986376. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

32.Przedborski S, Ischiropoulos H. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: weapons of neuronal destruction in models of Parkinson’s disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2005;7(5–6): 685-93. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

33.Tiffany-Castiglioni E, Saneto RP, Proctor PH, Perez-Polo JR. Participation of active oxygen species in 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity to a human neuroblastoma cell line. Biochem Pharmacol 1982;31(2): 181-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

34.Anastassova N, Aluani D, Hristova-Avakumova N, Tzankova V, Kondeva-Burdina M, Rangelov M, Todorova N, Yancheva D. Study on the neuroprotective, radical-scavenging and MAO-B inhibiting properties of new benzimidazole arylhydrazones as potential multi-target drugs for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Antioxidants 2022;11(5): 884. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

35.Loeffler C, Berger S, Guy A, Durand T, Bringmann G, Dreyer M, von Rad U, Durner JR, Mueller MJ. B1-phytoprostanes trigger plant defense and detoxification responses. Plant Physiol 2005;137(1): 328-40. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

36.Basu M, Mayana K, Xavier S, Balachandran S, Mishra N. Effect of scopoletin on monoamine oxidases and brain amines. Neurochem Int 2016;93: 113-7. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

37.Bie N, Feng X, Li C, Meng M, Wang C. The protective effect of docosahexaenoic acid on PC12 cells in oxidative stress induced by H2O2 through the TrkB-Erk1/2-CREB pathway. ACS Chem Neurosci 2021;12(18): 3433-44. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

38.Cai M, Bai X, Zang H, Tang X, Yan Y, Wan J, Peng M, Liang H, Liu L, Guo F. Quassinoids from twigs of Harrisonia perforata (Blanco) Merr and their anti-Parkinson’s disease effect. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24(22): 16196. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

39.Liu S, Xu W, Di Y, Tang M, Chen D, Cao M, Chang Y, Tang H, Yuan C, Yang J. Deciphering fungal metabolon coupling tandem inverse-electron-demand Diels-alder reaction and semipinacol rearrangement for the biosynthesis of spiro polycyclic alkaloids. Sci China Chem 2025;68(1): 288-96. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

40.Jiang X, Yuan Y, Chen L, Liu Y, Xiao M, Hu Y, Chun Z, Liao X. Monoamine oxidase B immobilized on magnetic nanoparticles for screening of the enzyme’s inhibitors from herbal extracts. Microchem J 2019;146: 1181-9. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

41.Xu G, Gong X, Zhu Y, Yao X, Peng L, Sun G, Yang J, Mao L. Novel 1, 2, 3-triazole erlotinib derivatives as potent IDO1 inhibitors: design, drug-target interactions prediction, synthesis, biological evaluation, molecular docking and ADME properties studies. Front Pharmacol 2022;13: 854965. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

42.Srinivasan M, Gangurde A, Chandane AY, Tagalpallewar A, Pawar A, Baheti AM. Integrating network pharmacology and in silico analysis deciphers Withaferin-A’s anti-breast cancer potential via hedgehog pathway and target network interplay. Brief Bioinform. 2024. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

43.Adilah ZM, Jamilah B, Hanani ZN. Functional and antioxidant properties of protein-based films incorporated with mango kernel extract for active packaging. Food Hydrocolloids 2018;74: 207-18. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

44.Tao Y, Li D, Chai WS, Show PL, Yang X, Manickam S, Xie G, Han Y. Comparison between airborne ultrasound and contact ultrasound to intensify air drying of blackberry: heat and mass transfer simulation, energy consumption and quality evaluation. Ultrason Sonochem 2021;72: 105410. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

45.Hu YK, Bai XL, Shi GY, Zhang YM, Liao X. Polyphenolic glycosides with unusual four-membered ring possessing anti-Parkinson’s disease potential from black wolfberry. Phytochemistry 2023;213: 113775. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© The Author(s) 2025

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.