Strophioglandins A–C, highly rearranged norditerpenoids with an unusual tricyclo[6.4.1.04, 13]tridecane core from Strophioblachia glandulosa var. cordifolia

Abstract

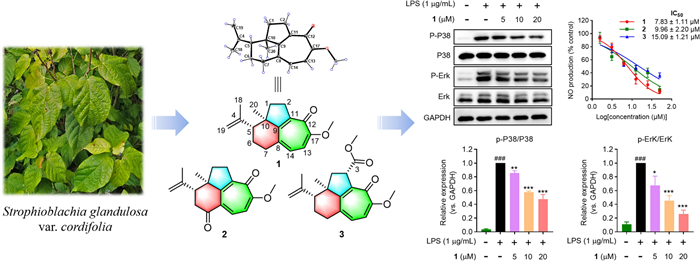

Strophioglandins A−C (1−3), three highly rearranged norditerpenoids featuring an unusual tricyclo[6.4.1.04, 13]tridecane core, were isolated from Strophioblachia glandulosa var. cordifolia. Integrated spectroscopic analyses, X-ray crystallography, and ECD calculations synergistically determined their molecular architectures. Remarkably, all compounds manifested potent anti-inflammatory effects in LPS-activated RAW264.7 cells with IC50 values ranging from 7.83 ± 1.11 to 15.09 ± 1.21 μM. Mechanism study revealed that strophioglandin A (1), the most potent compound, could suppress the expression of multiple inflammatory factors by inhibiting the P38 and Erk1/2 MAPK signaling pathways.Graphical Abstract

Keywords

Strophioblachia glandulosa var. cordifolia Rearranged norditerpenoids Anti-inflammatory effects MAPK signaling pathways1 Introduction

Euphorbiaceae plants are well known for producing structurally intricate macrocyclic and polycyclic diterpenoids with a broad range of bioactivities [1–6]. The pharmacological and chemical significance of these diterpenoids drives sustained research interest, because they not only serve as potential leads in drug discovery but also pose formidable synthetic challenges that inspire novel methodology design in organic chemistry. For instance, ingenol mebutate, an ingenane ester isolated from Euphorbia peplus L., received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2012 as a treatment for actinic keratosis [7]. Its precursor, (+)-ingenol, featuring a 5/7/7/3 tetracyclic architecture, has been elaborately synthesized in only 14 steps using a two-phase strategy [8, 9]. (−)-Pepluanol B, a potassium channel inhibitor with an unusual 5/5/8/3 ring system, has been totally synthesized via an unprecedented bromo-epoxidation maneuver [10].

Strophioblachia glandulosa var. cordifolia is a shrub distributed in southern Yunnan, China. Its chemical constituents have not been investigated to date. Previous phytochemical investigations on other species within Strophioblachia (Euphorbiaceae) have identified a series of structurally unique diterpenoids, some of which exhibited cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory, proliferation inhibition, neuroprotective, and anti-myocardial hypertrophy activities [11–14].

As part of our ongoing quest for bioactive natural products [15–18], three highly rearranged norditerpenoids, strophioglandins A−C (1−3), featuring an unusual tricyclo[6.4.1.04, 13]tridecane core (Fig. 1), were isolated from the twigs and leaves of S. glandulosa var. cordifolia. Their structures, including the absolute configurations, were identified by HRESIMS, spectroscopic methods, X-ray crystallography, and ECD calculations. Herein, we detail their structural characterization, putative biosynthetic pathways, anti-inflammatory effects, and the underlying mechanism.

The structures of compounds 1−3

2 Results and discussion

Strophioglandin A (1) was obtained as colorless needle crystals with a molecular formula C18H22O2 as determined by the HRESIMS ion at m/z 293.1518 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C18H22O2Na+, 293.1512), indicating eight indices of hydrogen deficiency (IHDs). The 1H NMR data (Table 1) displayed signals for two methyl groups [(δH 1.02 (s) and 1.84 (s)], a methoxy [δH 3.89 (s)], two cis-olefinic protons [δH 6.65 (1H, d, J = 10.3 Hz) and 6.87 (1H, d, J = 10.3 Hz)], two terminal double bond protons [δH 4.77 (s) and 4.95 (s)], and a series of aliphatic multiplets. The 1D NMR data (Table 1) of 1 showed 18 carbon resonances ascribed to a ketone carbonyl (δC 177.1), four double bonds (δC 162.5, 157.1, 148.7, 146.3, 136.5, 130.8, 113.2, 112.2), a methoxy group (δC 56.1), two methyls, four sp3 methylenes, an sp3 methine, and a quaternary carbon. As five of the eight IHDs were consumed by four double bonds and a ketone carbonyl, the remaining three IHDs were indicative of a tricyclic ring system.

1H (400 MHz) and 13C (100 MHz) NMR data of 1−3 in CDCl3 (δ in ppm, J in Hz)

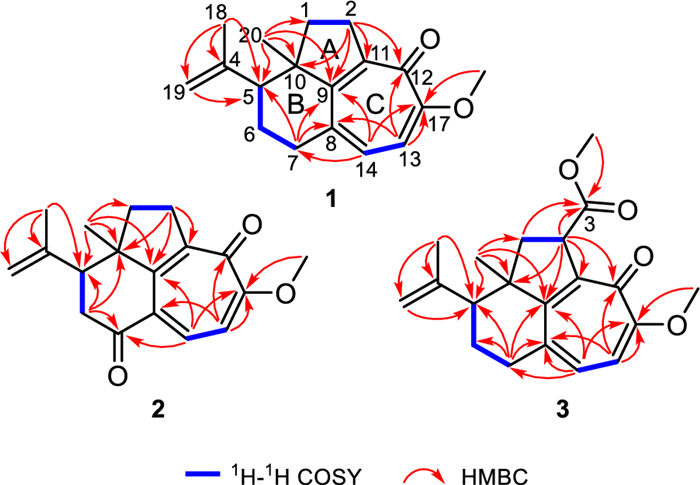

The planar structure of 1 was determined through comprehensive analysis of its 2D NMR data, including HSQC, 1H−1H COSY, and HMBC spectra. The key HMBC correlations from Me-20 to C-1/C-9/C-10 and from H2-2 to C-9/C-10/C-11, along with the 1H−1H COSY correlation of H2-1/H2-2 (Fig. 2), constructed a fragment of five-membered ring A with Me-20 located at C-10. Additionally, 1H−1H COSY spectrum of H-5/H2-6/H2-7, together with the HMBC cross-peaks from Me-20 to C-5/C-9/C-10 and from H2-7 to C-5/C-8/C-9 instructively established a six-membered ring B, which was fused with ring A by sharing C-9 and C-10. A typical isopropenyl group was positioned at C-5 in ring B as elucidated by the HMBC correlations from Me-18 to C-5 and the terminal double bond (δC 113.2 and 146.3), as well as from H2-19 to C-5. The 1H−1H COSY correlation of H-13/H-14 and the HMBC correlations from H2-2 to C-9/C-11/C-12, from H-13 to C-8/C-12/C-17, from H-14 to C-7/C-9/C-17, and from OMe-17 to C-17, led to the confirmation of a tropolone nucleus (ring C) with a ketone carbonyl (δC 177.1) and a methoxy group (δC 56.1 and δH 3.89) assigned at C-12 and C-17, respectively. Hence, the planar structure of 1 was established (Fig. 2), featuring a rare tricyclo[6.4.1.04, 13]tridecane core.

1H−1H COSY and key HMBC correlations of 1−3

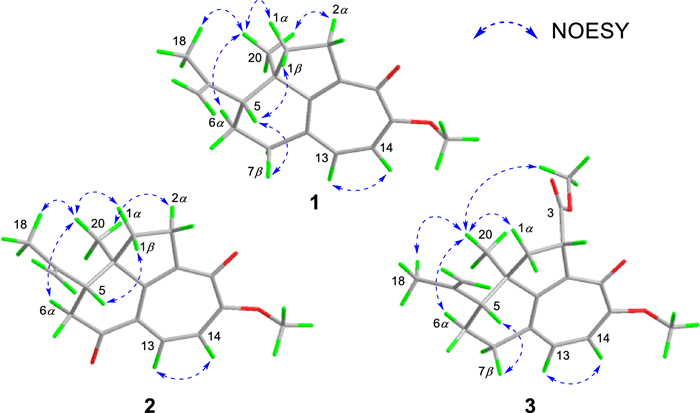

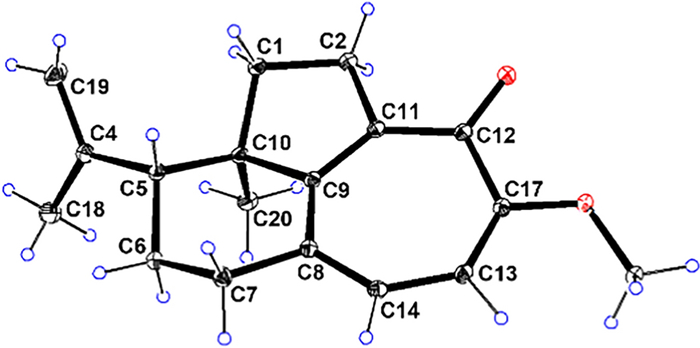

NOESY experiment enabled determination of the relative configuration of compound 1 (Fig. 3). The NOESY spectrum revealed a cross-peak between Me-18 and Me-20, indicating spatial proximity between the isopropenyl group and Me-20. These groups were thus assigned as co-facial and α-oriented. Therefore, the relative stereochemistry 5R*, 10R* was assigned to 1. The 5R, 10R absolute configuration of 1 was establishedby X-ray crystallography [Flack parameter: −0.06(10); CCDC number: 2422939] (Fig. 4).

Key NOESY correlations of 1−3

X-ray ORTEP diagram of 1

The HRESIMS data (m/z 307.1302 [M + Na]+, calcd. for C18H20O3Na+, 307.1305) established the molecular formula of strophioglandin B (2) as C18H20O3, implying nine IHDs. NMR data comparison (Table 1) indicated that 2 shares a core structure with 1, differing only by oxidation of the C-7 methylene (CH2-7) in 1 to the carbonyl group in 2, which was identified by signals from H2-6 to C-5/C-7(δC 198.3)/C-10 and from H-14 to C-7 in its HMBC spectrum, as well as the cross-peak (H-5 and H2-6) in the 1H−1H COSY

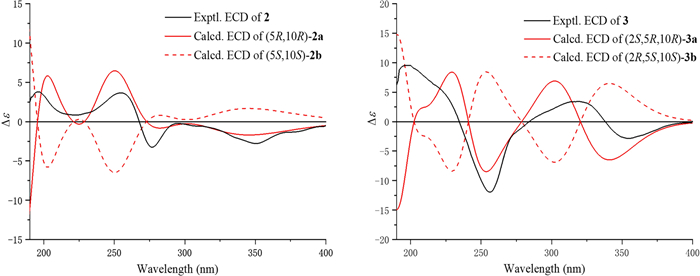

experiment (Fig. 2). Spatial proximity between Me-20 and the isopropenyl moiety was confirmed by NOESY (Fig. 3), establishing their α-configurational assignment. Biosynthetic considerations suggest congruent absolute configuration between 1 and 2, which was further supported by the comparable ECD curves of 2 and (5R, 10R)-2a (Fig. 5).

Experimental and calculated ECD curves of 2 and 3

The ion peak at m/z 329.1751 ([M + H]+, calcd. for C20H25O4+, 329.1747) in the HRESIMS spectrum assigned a molecular formula C20H24O4 to strophioglandin C (3). Comprehensive NMR data analysis established 3 as a structural analogue of 1, differing only by the replacement of one hydrogen at CH2-2 with a methoxycarbonyl group, which was substantiated by correlations from H-2 to C-3/C-9/C-10/C-11/C-12 and from H3-OMe-3 to C-3 (δC 174.7) in the HMBC experiment, coupled with the 1H−1H COSY cross-peak of H2-1/H-2 (Fig. 2). Therefore, we established the planar constitution of 3 as shown in Fig. 2. The NOESY spectrum showed key cross-peaks of Me-18/Me-20 and OMe-3/Me-20, implying they possessed spatial proximity and were arbitrarily defined as α-orientated. The relative stereochemistry 2S*, 5R*, 10R* was thus ascertained for 3. The absolute configuration 2S, 5R, 10R was further given for 3 as supported by the comparable ECD curves of 3 and (2S, 5R, 10R)-3a (Fig. 5).

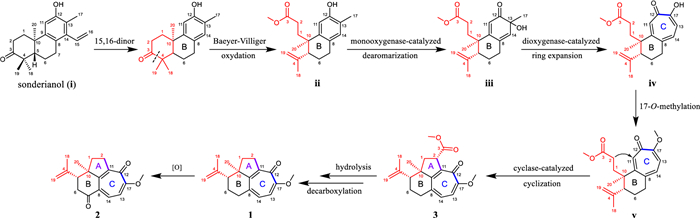

We propose putative biosynthetic pathways for 1−3 to get a better understanding of their structures (Scheme 1). First, sonderianol (ⅰ), a cleistanthane diterpenoid isolated from the same genus, was considered as a biosynthetic precursor, which may undergo carbon degradation and Baeyer–Villiger oxidation to form a 3, 4-seco intermediate (ⅱ). ⅱ was then dearomatized via hydroxylation at C-13 catalyzed by monooxygenase [19]. A key tropolone nucleus (ring C) in ⅳ was generated via dioxygenase-catalyzed ring expansion of ⅲ [19]. The 17-O-methylation of ⅳ afforded ⅴ, followed by the cyclase-catalyzed cyclization (attack from C-2 to C-11) to form compound 3 [20, 21]. Subsequently, 3 underwent hydrolysis and decarboxylation to afford 1, which could further produce 2 by the oxidation at C-7.

Proposed biosynthetic pathways for 1−3

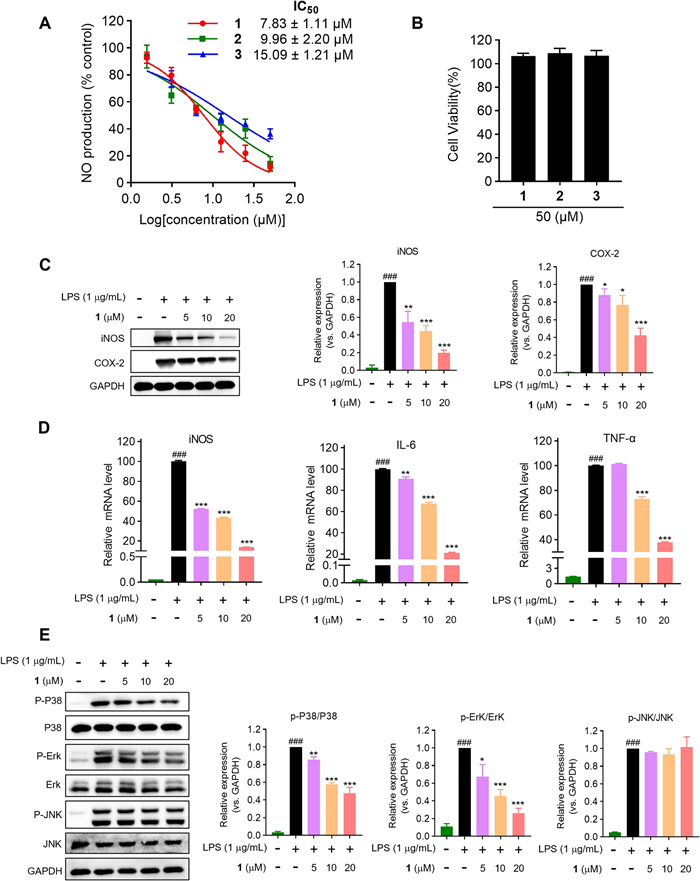

The suppression of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced nitric oxide (NO) production in Raw264.7 macrophages by all isolates was measured to evaluate their anti-inflammatory effects. Preliminary screening suggested that 1−3 had potent inhibitory activities (IC50s = 7.83−15.09 μM) (Fig. 6A) compared with the recognized NO inhibitor, quercetin (IC50 = 14.55 μM) [22, 23]. Meanwhile, the non-cytotoxicities of 1−3 to Raw264.7 cells at 50 μM indicated that their inhibitory activities did not result from cytotoxic effect. (Fig. 6B). Pro-inflammatory mediators generated by macrophages are potential biomarkers in the process of inflammation, such as PGE2, NO, IL-6, and TNF-α [22]. Subsequently, the effects of the most potent compound, strophioglandin A (1), on mRNA and the proteins levels were investigated in Raw264.7 macrophages. Pretreatment of 1 could dose-responsively suppress the LPS-triggered iNOS/COX-2 overexpression (Fig. 6C). Additionally, dose-responsive suppression of iNOS/IL-6/TNF-α transcription by 1 at concentrations of 5, 10, and 20 μM was evidenced as shown in Fig. 6D. The experiments mentioned above demonstrated that 1 could suppress the up-regulation of multiple inflammation-associated factors in LPS-triggered murine macrophages.

The anti-inflammatory effects of 1−3 in Raw264.7 cells. A Inhibitory effects of 1−3 on NO production. B The cytotoxicities of 1−3 measured by CCK-8 reagent. C Inhibitory effects of 1 on the expression of COX-2 and iNOS. D Inhibitory effects of 1 on mRNA levels by qRT-PCR analysis. E Immunoblot analysis of MAPK pathway proteins. The data were presented as the mean ± SD of at least three experiments. ### P < 0.001 vs control group; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 vs LPS group

Mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling transduced by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) governs inflammatory effector expression in LPS-activated macrophages [24]. Consequently, Western blotting was employed to determine whether 1 could suppress the activated MAPK signaling pathways, specifically P38, Erk1/2, and JNK. As demonstrated in Fig. 6E, the pretreatment of 1 could dose-responsively constrain the P38 and Erk1/2 phosphorylation after brief (10 min) LPS-stimulation, while being ineffective against the JNK phosphorylation. These experiments verified that compound 1 could selectively curtail P38 and Erk1/2 phosphorylation (JNK unaffected), attenuating key inflammatory effectors expression.

3 Experimental section

3.1 General experimental procedures

These are provided in the Supporting Information.

3.2 Plant material

We collected the twigs and leaves of S. glandulosa var. cordifolia from Yuanjiang County, Yunnan Province in August 2023. The plant was then identified by G.-H. Tang.

3.3 Extraction and isolation

Twigs and leaves of S. glandulosa var. cordifolia (14.5 kg, dry weight) were powdered and extracted, under ambient conditions, thrice with 95% ethanol (3 × 75 L), generating a crude extract Weighing 1.2 kg. An aqueous suspension of the crude extract was subjected to liquid–liquid partition against petroleum ether (PE), followed by ethyl acetate (EtOAc), and then n-butanol (n-BuOH). Fractionation of the EtOAc extract (280.0 g) on D101 macroporous resin chromatographic column (CC), using MeOH/H2O (3:1 → 1:0, v/v), yielded two fractions (Fr. I and Fr. II). Fr. I (86.2 g) was subjected to a silica gel column using CH2Cl2/MeOH (1:0 → 0:1, v/v), yielding eight subfractions (Fr. IA−Fr. IH). Among these, subfraction Fr. IB (10.0 g) was further subjected to silica gel chromatography using a PE/EtOAc gradient (8:1 → 0:1, v/v), affording nine fractions (Fr. IB1−Fr. IB9). Fr. IB8 (1.5 g) was further subjected to Sephadex LH-20 CC (MeOH), affording compounds 1 (20.5 mg, tR = 18.2 min), 2 (3.2 mg, tR = 19.3 min), and 3 (16.8 mg, tR = 15.6 min) followed by semi-preparative HPLC refinement (MeCN/H2O, 48:52, v/v; 3.0 mL/min).

3.4 Spectroscopic data of the compounds

3.4.1 Strophioglandin A (1)

Colorless crystal; [α]D20−160 (c 0.1, MeCN); UV (MeCN) λmax (log ε) 253 (4.42), 333 (3.90) nm; ECD (c 7.40 × 10−4, MeCN) λmax (Δε) 232 (+ 1.70), 354 (−3.07) nm; IR (neat) νmax 2948, 2857, 1584, 1559, 1455, 1256, 1190, 1060, 1018, 890 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 293.1518 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C18H22O2Na+, 293.1512).

3.4.2 Strophioglandin B (2)

Yellowish oil; [α]D20−103 (c 0.1, MeCN); UV (MeCN) λmax (log ε) 240 (4.16), 269 (4.31), 355 (3.89) nm; ECD (c 3.52 × 10−4, MeCN) λmax (Δε) 196 (+ 3.80), 255 (+ 3.67), 277 (−3.26), 350 (−2.78) nm; IR (neat) νmax 2960, 2925, 2853, 1683, 1585, 1456, 1261, 1187, 1055, 1007, 896 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 307.1302 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C18H20O3Na+, 307.1305).

3.4.3 Strophioglandin C (3)

Yellowish oil; [α]D20−55 (c 0.1, MeCN); UV (MeCN) λmax (log ε) 251 (4.45), 330 (4.00) nm; ECD (c 3.05 × 10−4, MeCN) λmax (Δε) 256 (−11.97), 319 (+ 3.43) nm; IR (neat) νmax 2948, 1732, 1568, 1454, 1343, 1259, 1180, 1073, 1003, 894, 845 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 329.1751 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C20H25O4+, 329.1747).

3.5 Crystallographic data for 1

C18H22O2 (M = 270.35 g/mol): orthorhombic, space group P 21 21 21 (no. 19), a = 6.19478(9) Å, b = 6.86349(9) Å, c = 34.2241(4) Å, α = 90°, β = 90°, γ = 90°, V = 1455.14(3) Å3, Z = 4, T = 100 K, μ (Cu Kα) = 0.616 mm−1, Dcalc = 1.234 g/cm−3, 14 428 reflections measured (5.164° ≤ 2θ ≤ 157.466°), 3052 unique (Rint = 0.0449, Rsigma = 0.0436), which were used in all calculations. The final R1 was 0.0436 (I > 2σ(I)) and wR2 was 0.1176 (all data). Flack parameter: −0.06(10). CCDC number: 2422939.

3.6 ECD calculations

These are provided in the Supporting Information for 2 and 3.

3.7 Cell culture

Cell culture was performed according to the established protocol [25].

3.8 Cytotoxicity assay

Raw264.7 cells (5 × 104 cells/well), prior to compounds treatment for 24 h, were allowed to adhere in 96-well plates. Following 24 h incubation at 37 ℃, cell viability was assessed by using CCK-8 reagent (Dojindo, Japan) with 10 μL reagent added per well. Absorbance was finally recorded by means of a multifunction microplate reader at 450 nm.

3.9 Analysis of NO production

Following a 24-h incubation period after plating Raw264.7 macrophages (5 × 104 cells/well) in 96-well plates, compounds were added at increasing concentrations (5, 10, and 20 μM) and incubated, with or without LPS (1 μg/mL), for 24 h in media. NO concentration in the culture medium was quantified using a Griess reagent kit, following the manufacturer's protocol. For the assay, 50 μL of Griess reagent was mixed with an equal volume of cell culture supernatant. With quercetin serving as the positive control, the absorbance at 540 nm, by means of a multifunction microplate reader, was measured.

3.10 qRT-PCR analysis

This was performed according to the established protocol [25].

3.11 Western blotting analysis

This was performed according to the established protocol [25].

3.12 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis followed the approach of reference [25].

4 Conclusion

In summary, three highly rearranged cleistanthane norditerpenoids (1−3) featuring an unusual tricyclo[6.4.1.04, 13]tridecane carbon core, were isolated from S. glandulosa var. cordifolia. Compounds 1 and 2 are the first reported trinorditerpenoids with a highly fused 5/7/6-tricyclic skeleton. Notably, bioactivity evaluation demonstrated that all isolates exhibited remarkable anti-inflammatory effects. Strophioglandin A (1), the most potent compound, attenuated LPS-induced secretion of key pro-inflammatory cytokines (iNOS, IL-6, and TNF-α) in murine macrophages via blockade of MAPK signaling (P38 and Erk1/2 phosphorylation). This study deepens the chemical investigation of the genus Strophioblachia, and suggests potential application of the norditerpenoids as novel anti-inflammatory agents for inflammatory disease treatment.

Notes

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82273804, 82304322, 82404454, and 22407144), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (No. 2024B03J1322), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, China (No. 2023A1111120025), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (No. GZC20242113), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2024M753800), and Jiangxi "Double Thousand Plan" (No. JXSQ2023102240).

Author contributions

JKX carried out the experiment of isolation and structural elucidation and the writing—original draft; LMW screened the biological activities; WYW, DH, SQW, and YJZ analysed the results and did validation; FYY and LL did the ECD calculations and visualization; TY, XC, and GHT carried out the methodology and the writing—review and editing. JLH and SY supervised the whole study, designed and checked the whole manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82273804, 82304322, 82404454, and 22407144), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (No. 2024B03J1322), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, China (No. 2023A1111120025), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (No. GZC20242113), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2024M753800), and Jiangxi "Double Thousand Plan" (No. JXSQ2023102240).

Data availability

The experimental data supporting this work are accessible within the article and its Additional file 1.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests pertaining to this work.

References

-

1.Zhan ZJ, Li S, Chu W, Yin S. Euphorbia diterpenoids: isolation, structure, bioactivity, biosynthesis, and synthesis (2013–2021). Nat Prod Rep 2022;39: 2132-74. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

2.Chen YN, Ding X, Li DM, Lu QY, Liu S, Li YY, et al. Jatrophane diterpenoids from the seeds of Euphorbia peplus with potential bioactivities in lysosomal-autophagy pathway. Nat Prod Bioprospect 2021;11: 375-464. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

3.Li CL, Ma MH, Liu X, Hu Y, Feng ZG, Zhang RX, et al. Natural diterpenoids in dermatology: multifunctional roles and therapeutic potential for skin diseases. Phytomedicine. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156842. PubMed Google Scholar

-

4.Vasas A, Hohmann J. Euphorbia diterpenes: isolation, structure, biological activity, and synthesis (2008–2012). Chem Rev 2014;114: 8579-612. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

5.Tan CJ, Li SF, Huang N, Zhang Y, Di YT, Zheng YT, et al. Daphnane diterpenoids from Trigonostemon lii and inhibition activities against HIV-1. Nat Prod Bioprospect 2020;10: 37-44. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

6.Lin BD, Zhou B, Dong L, Wu Y, Yue JM. Formosins A-F: diterpenoids with anti-microbial activities from Excoecaria formosana. Nat Prod Bioprospect 2016;6: 57-61. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

7.Gupta AK, Paquet M. Ingenol mebutate: a promising treatment for actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers. J Membr Sci 2013;17: 173-9. PubMed Google Scholar

-

8.McKerrall SJ, Jorgensen L, Kuttruff CA, Ungeheuer F, Baran PS. Development of a concise synthesis of (+)-ingenol. J Am Chem Soc 2014;136: 5799-810. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

9.Jorgensen L, McKerrall SJ, Kuttruff CA, Ungeheuer F, Felding J, Baran PS. 14-step synthesis of (+)-ingenol from (+)-3-carene. Science 2013;341: 878-82. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

10.Zhang J, Liu M, Wu CH, Zhao GY, Chen PQ, Zhou L, et al. Total synthesis of (−)-pepluanol B: conformational control of the eight-membered ring system. Angew Chem Int Ed 2020;59: 3966-70. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

11.Jiang HL, Zhang YY, Mao HY, Zhang Y, Cao YX, Yu HY, et al. Strophiofimbrins A and B: two rearranged norditerpenoids with novel tricyclic carbon skeletons from Strophioblachia fimbricalyx. J Org Chem 2023;88: 5936-43. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

12.Yang CS, Jiang HL, Mao HY, Zhang Y, Zhang YY, Dong XY. Strophioblin, a novel rearranged dinor-diterpenoid from Strophioblachia fimbricalyx. Tetrahedron 2023;135: 133331. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

13.Qiu X, Huang YX, Yuan J, Zu XD, Zhou YL, Li R, et al. Strophioblachins A−K, structurally intriguing diterpenoids from Strophioblachia fimbricalyx with potential anticardiac hypertrophic inhibitory activity. J Nat Prod 2023;86: 1211-21. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

14.Wu XW, Wang BB, Qin Y, Huang YX, Zeb MA, Cheng B, et al. Diterpenoids with unexpected 5/6/6-fused ring system and its dimer from Strophioblachia glandulosa. Chin Chem Lett 2024;29: 110584. PubMed Google Scholar

-

15.Huang JL, Yan XL, Li W, Fan RZ, Li S, Chen JH, et al. Discovery of highly potent daphnane diterpenoids uncovers importin-β1 as a druggable vulnerability in castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Am Chem Soc 2022;144: 17522-32. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

16.Gan L, Jiang QW, Huang D, Wu XJ, Zhu XY, Wang L, et al. A natural small molecule alleviates liver fibrosis by targeting apolipoprotein L2. Nat Chem Biol 2025;21: 80-90. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

17.Wei X, Huang JL, Gao HH, Yuan FY, Tang GH, Yin S. New halimane and clerodane diterpenoids from Croton cnidophyllus. Nat Prod Bioprospect 2023;13: 21. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

18.Wu WY, Wei X, Liao Q, Fu YF, Wu LM, Li L, et al. Structurally diverse polyketides and alkaloids produced by a plant-derived fungus Penicillium canescens L1. Nat Prod Bioprospect 2025;15: 22. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

19.Davison J, Aal F, Cai MH, Song ZS, Yehia SY, Lazarus CM, et al. Genetic, molecular, and biochemical basis of fungal tropolone biosynthesis. PNAS 2012;109: 7642-7. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

20.Rudolf JD, Chang CY. Terpene synthases in disguise: enzymology, structure, and opportunities of non-canonical terpene synthases. Nat Prod Rep 2020;37: 425-63. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

21.Tang MC, Shen C, Deng ZX, Ohashi M, Tang Y. Combinatorial biosynthesis of terpenoids through mixing-and-matching sesquiterpene cyclase and cytochrome P450 pairs. Org Lett 2022;24: 4783-7. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

22.Huang JL, Fan RZ, Zou YH, Zhang L, Yin S, Tang GH. Salviplenoid A from Salvia plebeia attenuates acute lung inflammation via modulating NF-κB and Nrf2 signaling pathways. Phytother Res 2020;35: 1559-71. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

23.Zou YH, Zhao L, Xu YK, Bao JM, Liu X, Zhang JS, et al. Anti-inflammatory sesquiterpenoids from the traditional Chinese medicine Salvia plebeia: regulates pro-inflammatory mediators through inhibition of NF-κB and Erk1/2 signaling pathways in LPS-induced raw264.7 cells. J Ethnopharmacol 2018;210: 95-106. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

24.Gantke T, Sriskantharajah S, Sadowski M, Ley SC. IκB kinase regulation of the TPL-2⁄ERK MAPK pathway. Immunol Rev 2012;246: 168-82. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

25.Lu QR, Li L, Cui QY, Liao Q, Malik N, Wu LM, et al. Sclerotiorin-type azaphilones isolated from a marine-derived fungus Microsphaeropsis arundinis P1B. J Nat Prod 2025;88: 1075-84. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© The Author(s) 2025

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.