Chalasoergodimers A–E, heterodimers with multiple polymerization modes from a marine-derived Chaetomium sp. fungus

Abstract

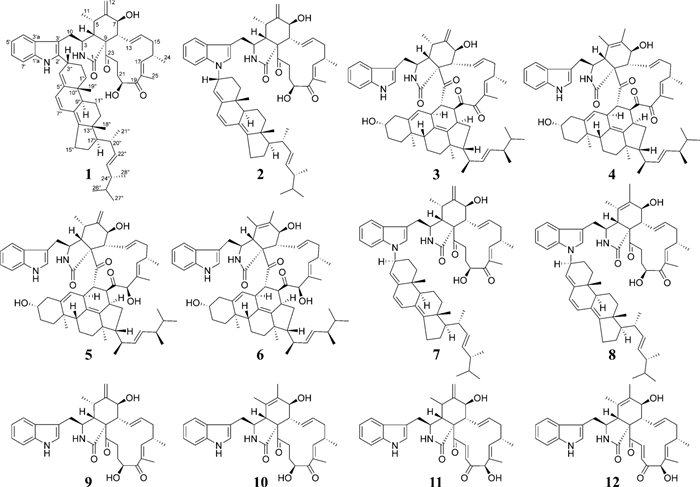

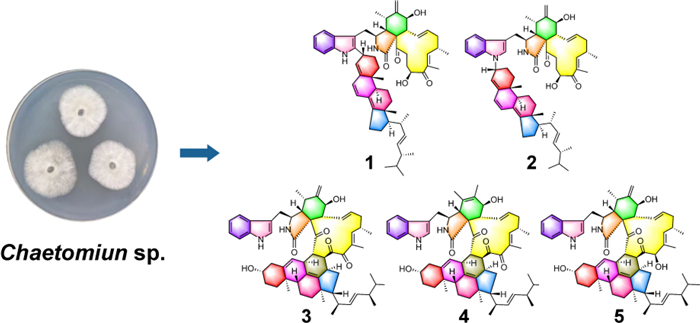

Five new heterodimers, chalasoergodimers A–E (1–5), and three known heterodimers (6–8), along with four chaetoglobosin monomers (9–12), were isolated from a marine-derived Chaetomium sp. fungus. The structures of new compounds 1–5 were elucidated by HRESIMS, NMR, chemical calculated 13C NMR and ECD methods. Among them, compound 1 was derived from C-2′ substitution of chaetoglobosin Fex (9) with ergosta-4, 6, 8(14), 22-tetraen-3β-ol, representing a new dimerization mode among chaetoglobosin-ergosterol derivative hybrids. Compound 2 featured substitution at NH-1′ and constituted the first example of this dimeric type bearing an R-configuration at C-3′′. Compounds 3–5 were formed via a Diels–Alder cycloaddition between chaetoglobosins and 14-dehydroergosterol. Furthermore, it was revealed that compound 9–12 exhibited the significant cytotoxic activity against the human non-small cell lung cancer cell (A549), with compound 12 showing the most potent effect at an IC50 of 5.14 μM.Graphical Abstract

Keywords

Marine-derived fungus Chaetomium sp. Chaetoglobosin Cytotoxic activity1 Introduction

Complex biosynthetic mechanisms underlay the structural diversity and complexity of natural products (NPs) [1]. Extensive exploration of NPs resources contributed to the identification of candidates with promising pharmacological activity, facilitating the discovery of lead compounds with high target specificity and potent biological efficacy [2–4]. The discovery of NPs with new scaffolds and exceptional bioactivities continued to captivate chemists and biologists [5]. In organisms, enzymatic reactions constituted the foundation of NPs biosynthesis: primary metabolites underwent enzymatic transformations into intermediates, which were further processed into final products by multi-enzyme complexes and tailoring enzymes [6, 7]. Additionally, non-enzymatic pathways, which was driven by chemical reactivity, evolutionary pressure, and the acidic or basic nature of the medium, functioned independently of enzymes and complemented enzymatic routes in contributing to NP biosynthesis [8].

Guided by their structural chemical properties, natural products underwent dimerization of secondary metabolites into homodimers or heterodimers through enzymatic and non-enzymatic polymerization reactions [9]. Reported dimeric NPs included coumarins [10], terpenoids [11], flavonoids [12], alkaloids [13], and others. Enzymatic dimerization typically involved cyclases and condensing enzymes [14]. Cyclases catalyzed cyclization reactions between monomers to form dimers. For instance, the FAD-dependent enzyme MaDA was identified as a monofunctional enzyme that catalyzed Diels–Alder reactions [15]. Condensing enzymes catalyze monomer condensation to form dimers. For example, AsuC3 and AsuC4 catalyzed condensation reactions to form polyketide side chains, which were critical biosynthetic steps for dimer formation [16]. In addition, certain oxidases catalyzed radical generation to participate in dimer formation [17]. Non-enzymatic reactions, guided by chemical properties, also occurred through spontaneous cycloaddition or condensation processes under physiological conditions [18].

Polymerization of two monomers altered the structural framework, enabling certain dimers to exhibit enhanced or even novel bioactivities compared to monomers [19]. Dibohemamine B, a methylene‑bridged dimer of two bohemamine monomers, demonstrated potent anti-non-small cell (A549) activity, whereas the bohemamine monomer was inactive [20]. Similarly, the terpene-nonadride heterodimer bipoterpride B showed notably enhanced biological activity compared to its monomers [21]. Enhanced bioactivity may arise from structural and conformational changes following dimerization that improved target binding [22]. Alternatively, modifications in chemical properties, such as increased structural stability and altered polarity, boosted bioavailability and efficacy in vivo [23, 24]. Overall, the identification of dimers with novel skeletons significantly advanced our comprehension of the polymerization mechanisms of natural product monomers and facilitated the screening of lead compounds exhibiting promising bioactivities.

The fungi of Chaetomium species were reported to be capable of producing a variety of heterodimeric compounds [25, 26]. In this work, a marine-derived fungus Chaetomium sp. was chosen as the research subject. As a result, five new heterodimeric compounds (1–5), three known heterodimers, including ergochaeglobosin A (6) [27], ergochaeglobosin E (7) [27], ergochaeglobosin D (8) [27], and four known chaetoglobosin monomers, including chaetoglobosin Fex (9) [28], chaetoglobosin E (10) [29], chaetoglobosin D (11) [29], and chaetoglobosin B (12) [29], were obtained from this fungal strain (Fig. 1). Notably, the polymerization pattern of chaetoglobosin and ergosterol derivative in 1 marked the first report of this specific dimer type. Subsequently, the cytotoxicities of these compounds were also assessed.

Chemical structures of compounds 1–12

2 Results and discussion

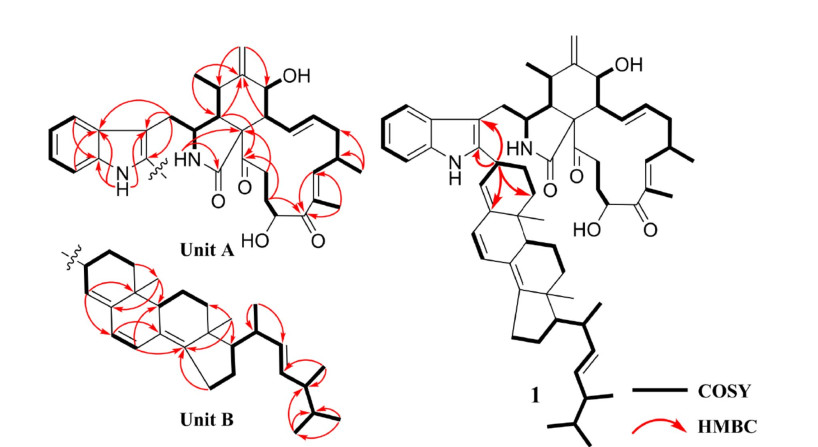

Chalasoergodimer A (1) was isolated as a brown powder. Its molecular formula was determined to be C60H78N2O5, indicating 23 degrees of unsaturation, based on the HRESIMS ion peak at m/z 929.5818 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C₆₀H₇₈N₂O₅Na+, 929.5808). The 1H NMR and HSQC spectra (Table 1 and Fig. S7) revealed the presence of an indolyl moiety, characterized by four coupled aromatic protons at δH 7.40 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.28 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.14 (dd, 1H, J = 7.8, 7.8 Hz), and 7.11 (dd, 1H, J = 7.8, 7.8 Hz). Eight non-terminal olefinic protons were observed at δH 6.31 (dd, 1H, J = 13.8, 9.6 Hz), 6.26 (d, 1H, J = 9.6 Hz), 6.19 (d, 1H, J = 9.6 Hz), 5.98 (d, 1H, J = 9.6 Hz), 5.51 (d, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 5.39 (ddd, 1H, J = 14.4, 10.8, 2.4 Hz), and two signals at δH 5.24 (dd, 1H, J = 15.6, 7.2 Hz). Two terminal olefinic protons appeared at δH 5.32 (s, 1H) and 5.13 (s, 1H). Nine methyl groups were detected at δH 1.87 (s, 3H), 1.10 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz), 1.06 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz), 1.06 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz), 0.96 (s, 3H), 0.95 (s, 3H), 0.94 (d, 3H, J = 7.8 Hz), 0.85 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz), and 0.84 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz). The 13C NMR (Table 1) and HSQC spectra displayed 60 carbon signals, including two ketone carbonyls (δC 208.0 and 203.7), one amide carbonyl (δC 173.6), 22 olefinic carbons, two oxygenated carbons (δC 71.5 and 70.2), and 33 aliphatic carbons. The planar structure of 1 was further confirmed by analysis of 1H-1H COSY and HMBC spectra (Fig. 2). The 1H-1H COSY correlations of H-4′/H-5′/H-6′/H-7′, together with HMBC correlations from NH-1′ to C-1′a, C-3′, C-3′a, from H-4′ to C-1′a, and from H-7′ to C-3′a, suggested that the indole moiety contained only five hydrogen atoms. The 1H-1H COSY correlations of H-2/H-3/H-4/H-5/H-11, H-7/H-8/H-13/H-14/H-15/H-16/H-17, and H-20/H-21/H-22, along with the HMBC correlations from NH-2 to C-1, C-9, from H-4 to C-6, C-23, from H-12 to C-5, C-7, from H-17 to C-19, C-25, and from H-21 to C-19, C-23, further established unit A as the C-2′ dehydrogenated derivative of chaetoglobosin Fex (9). The characteristic structure included amide group at C-1, carbonyl groups at C-19 and C-23, a terminal alkene at C-12, and a hydroxyl group at C-20. In the structure of unit B, 1H-1H COSY correlations of H-1′′/H-2′′/H-3′′/H-4′′, H-6′′/H-7′′, H-9′′/H-11′′/H-12′′, H-15′′/H-16′′/H-17′′/H-20′′/H-22′′/H-23′′/H-24′′/H-25′′/H-26′′, together with HMBC correlations from H-3′′ to C-5′′, from H-4′′ to C-6′′, C-10′′, from H-6′′ to C-8′′, from H-7′′ to C-9′′, C-14′′, and from H-18′′ to C-12′′, C-14′′, C-17′′, indicated that unit B possessed a ergosta-4, 6, 8(14), 22-tetraen-3β-ol skeleton [30] substituted at C-3′′. Moreover, the key HMBC correlations from H-3′′ to C-2′, C-3′, along with the absence of a proton signal at C-2′ in the HSQC spectrum, suggested that the planar structure of 1 consisted of chaetoglobosin Fex and ergosta-4, 6, 8(14), 22-tetraen-3β-ol moiety, connected through a C–C single bond between C-2′ and C-3′′, with the hydroxyl group at C-3′′ eliminated.

1H (600 MHz) and 13C (150 MHz) NMR data of compounds 1 and 2 in CDCl3

The 1H-1H COSY and key HMBC correlations of 1

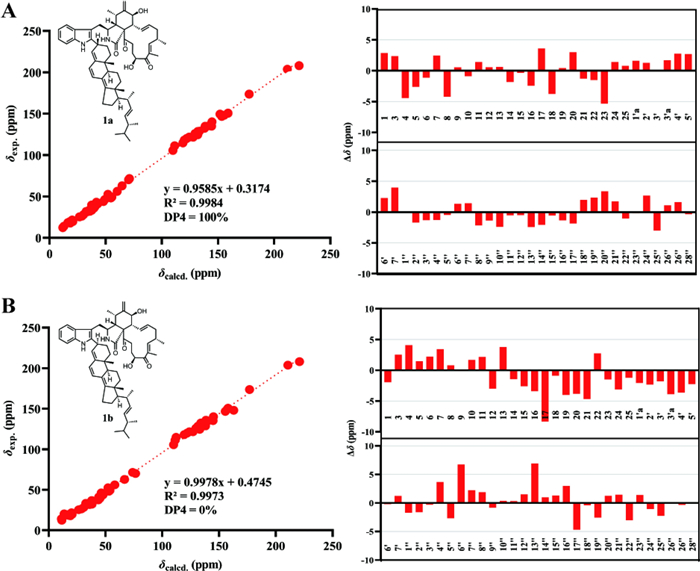

To further evaluate the rationality of the planar structure of 1, gauge-independent atomic orbital (GIAO) calculations were performed to predict the 13C NMR chemical shifts of a model featuring a linkage between C-2′ of chaetoglobosin Fex and C-3′′ of ergosta-4, 6, 8(14), 22-tetraen-3β-ol. As C-3′′ was a stereogenic center, two configurations were considered, and the 13C NMR chemical shifts of both were calculated. Linear regression analysis of the calculated versus experimental 13C chemical shifts, together with deviation analysis (Fig. 3), indicated that the C-2′/C-3′′ linkage pattern determined by 1D and 2D NMR data was reasonable. In this mode, the calculated 13C NMR data showed good agreement with the experimental results. For 1a, the correlation coefficient (R2) was 0.9984, and all absolute deviations (|∆δ|) were within 5.40 ppm. Moreover, the key positions C-2′ and C-3′′ exhibited minimal deviations, with |∆δ| values below 1.30 ppm, suggesting that 1 was more likely to adopt the 1a structure.

A Linear Regression analysis, DP4 analysis and subtraction of the experimental and calculated 13C NMR chemical shifts of 1a.

B Linear Regression analysis, DP4 analysis and subtraction of the experimental and calculated 13C NMR chemical shifts of 1b

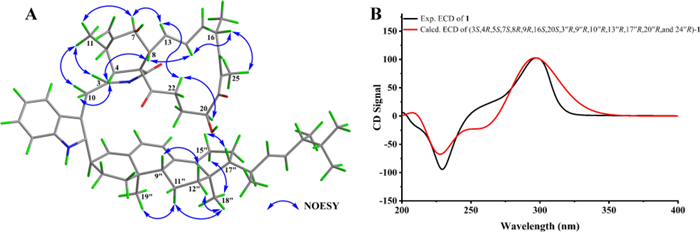

The relative configuration of unit A was comprehensively assessed through coupling constants, NOESY correlations, and chemical shifts. The coupling constant between H-13 and H-14 in unit A exceeded 12 Hz, supporting an E-configuration for the Δ13 double bond. The NOESY correlation between H-8 and H-14 further supported this assignment. The NOESY correlation between H-16 and H3-25 indicated that the Δ17 double bond also adopted an E-configuration. A series of NOESY correlations involving H-3/H3-11, H3-11/H-7, H-7/H-13, H-13/H-22a, and H-22a/H-20 suggested that these protons shared the same spatial orientation. Likewise, NOESY cross-peaks observed between H-4/H-8, H-8/H-14, and H-14/H-16 indicated that these protons also adopted a common orientation. To further assign the relative configuration at C-16 and C-20, the comparison of the NMR data (Table S1) between 1 and 9 revealed that the chemical shifts of H-20, C-16, and C-20 were generally similar (|ΔδH|≤ 0.1 ppm, |ΔδC|≤ 0.3 ppm). Comparison with 7 showed that the chemical shifts of H-16, H-20, C-16, and C-20 in 1 were similar to those in 7 (|ΔδH|≤ 0.06 ppm, |ΔδC|≤ 0.3 ppm). These similar chemical shifts suggested that 1, 7, and 9 shared closely related structures and configurations. Therefore, the relative configuration of unit A was assigned as 3S*, 4R*, 5S*, 7S*, 8R*, 16S*, and 20S*. The configuration of unit B in 1 was assessed based on coupling constant analysis and NOESY data. The large coupling constant between H-22′′ and H-23′′ suggested that the Δ22′′ double bond adopted an E-configuration. NOESY correlations between H-11′′b and both H3-18′′ and H3-19′′ implied that the methyl groups at C-10′′ and C-13′′ were located on the same face. The NOESY correlations of H-9″/H-12″b and H-12″a/H3-18″ indicated that H-9″ and H3-18″ were oriented on opposite faces. The NOESY correlations of H-15″a with H-17″, and H-15″b with H3-18″ indicated that H-17″ and H3-18″ were oriented on opposite faces. Due to the conformational flexibility of the side chain in unit B, the relative configurations at C-20′′ and C-24′′ could not be accurately determined based on NOESY data alone. Due to the lack of key NOESY correlations for C-3″, its relative configuration could not be reliably determined. Except for C-3″, C-20″, and C-24″, the relative configuration of unit B was determined as 9″R*, 10″R*, 13″R*, and 17″R*.

Among the reported chaetoglobosins derived from Chaetomium species [31–34], the configurations at C-3, C-4, C-8, C-9, and C-16 were relatively conserved as 3S, 4R, 8R, 9R, and 16S, respectively. When a methyl group was attached at C-5, it typically exhibited the S-configuration. Similarly, the presence of a hydroxyl group at C-7 was generally associated with the S-configuration. In most cases, the hydroxyl substitution at C-20 displayed an S-configuration. Only a few reports described an R-configuration at C-20, which notably affected the chemical shifts of C-20 and its neighboring atoms.

Based on the relative configuration of 1, as well as the characteristic structural analogy to related compounds derived from Chaetomium species, the absolute configuration of unit A was confirmed as 3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, and 20S. To determine the absolute configuration of unit B, its chemical shifts were compared (Table S2) with those of the monomer ergosta-4, 6, 8(14), 22-tetraen-3β-ol [30]. The side chain from C-20′′ to C-28′′ exhibited closely matching chemical shifts (|ΔδH|≤ 0.1 ppm), indicating that the stereocenters at C-20′′ and C-24′′ likely possessed the same configurations. A similar comparison between 1 and 7 also showed comparable chemical shifts for the side chain in unit B (|ΔδH|≤ 0.1 ppm). Furthermore, a structural feature comparison of ergosterol and its derivatives derived from Chaetomium species revealed that those bearing chemically identical side chains consistently adopted R-configurations at C-20 and C-24, while S-configured analogues have not been widely reported in the literature [31–34]. Thus, both of the absolute configurations at C-20′′ and C-24′′ in unit B were tentatively assigned as R-configuration. Based on the relative configuration of unit B and structural analogies of the chiral centers in ergosterol and its derivatives derived from Chaetomium species, the absolute configuration of unit B, excluding C-3″, was assigned as 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R.

To further evaluate the configuration at C-3′′, DP4 analysis was performed for the two possible isomers. The DP4 results (Fig. 3) indicated that the population of 1a was 100%, whereas that of 1b was 0%, suggesting that the configuration at C-3′′ in 1 was R configuration. Subsequently, density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B3LYP/6–311 + G(d, p) level in methanol were carried out for (3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 20S, 3′′R, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R)-1, and the calculated ECD spectrum was compared with the experimental one. The results (Fig. 4) showed that the calculated and experimental ECD spectra exhibited good agreement. The absolute configuration of 1 was thus assigned as 3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 20S, 3′′R, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R.

A Key NOESY correlations and B experimental versus calculated ECD spectra of 1

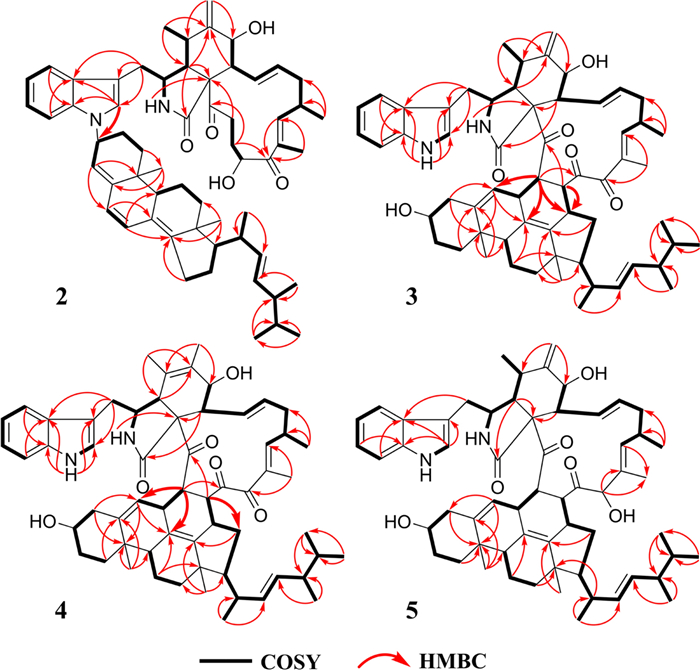

Chalasoergodimer B (2) was isolated as a brown powder. The molecular formula was determined to be C60H78N2O5, indicating 23 degrees of unsaturation, based on the HRESIMS ion peak at m/z 929.5811 [M + Na]+ (C60H78N2O5Na+, calcd. for 929.5808). The NMR data of 2 (Table 1) closely resembled those of 1, except for differences in the indolyl moiety. Other signals, including two carbonyl groups, one amide group, two hydroxyl groups, and seven double bonds (including one terminal double bond), were consistent with those of 1. These findings suggested that 2 was also formed from chaetoglobosin Fex and ergosta-4, 6, 8(14), 22-tetraen-3β-ol, but exhibited a distinct substitution pattern compared to 1. Comparison of the indole proton signals revealed an additional signal at δH 6.98 (s, 1H) in 2, and lacked the proton signal for NH-1′, indicating that the substitution occurred at N-1′ rather than C-2′. This was further supported by the key HMBC correlation from H-2′ to C-3′′ (Fig. 5), which confirmed that the substitution took place at the NH-1′ position of the indolyl unit. Except for the connecting site and its neighboring region, compounds 1 and 2 generally exhibited similar 1D and 2D NMR signals in other regions.

The 1H-1H COSY and key HMBC correlations of 2–5

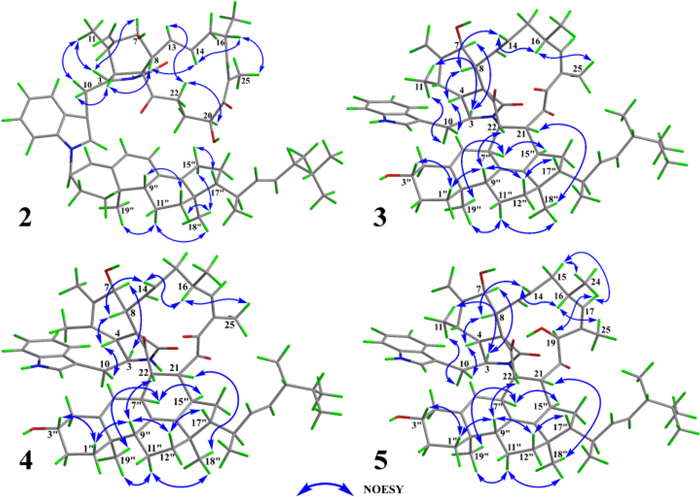

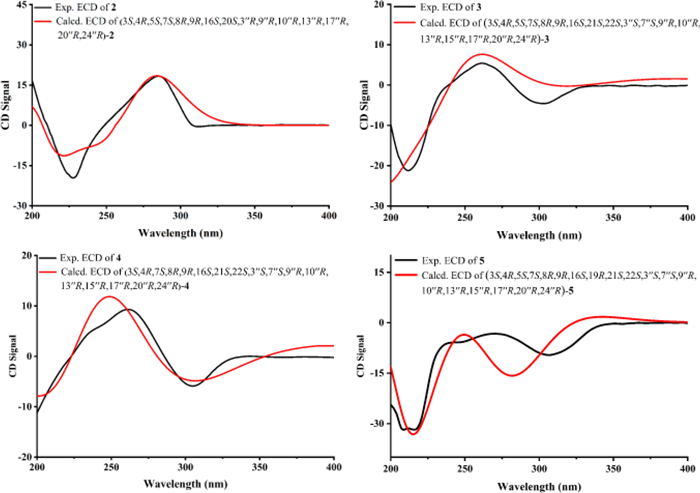

Compound 2 was suggested to possess the same monomeric composition as 1, but with a different dimerization pattern. Given that 2 exhibited several identical NOESY correlations (Fig. 6), closely similar chemical shifts, and comparable coupling constants to those of 1, it was considered reasonable to infer that the difference in dimerization mode did not significantly affect the relative or absolute configurations of the structure, except for C-3″. Therefore, 2 was considered to share the same relative and absolute configurations as 1 except the dimerization sites. The absolute configuration of 2, excluding C-3″, was suggested as 3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 20S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R. The C-3′′ configuration of 2 was determined using the same approach as for 1. DP4 analysis was performed to evaluate the distribution of the two possible configurations at the C-3′′ stereocenter. The results (Fig. S31) indicated that 2 was assigned 100% to the 3′′R configuration and 0% to the 3′′S configuration. Subsequently, theoretical ECD spectra of (3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 20S, 3′′R, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R)-2 was calculated and compared with the experimental ECD spectrum of 2. As shown in Fig. 7, the calculated spectrum of the (3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 20S, 3′′R, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R)-2 showed better agreement with the experimental data, supporting the assignment of the absolute configuration of 2 as 3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 20S, 3′′R, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R.

Key NOESY correlations of 2–5

Experimental versus calculated ECD spectra of 2–5

Chalasoergodimer C (3) was obtained as a white powder. The molecular formula was determined as C60H76N2O6, corresponding to 24 degrees of unsaturation, based on the HRESIMS ion peak at m/z 943.5598 [M + Na]+ (C60H76N2O6Na+, calcd. for 943.5601). The 1H, 13C, and HSQC spectra (Table 2 and Fig. S38) exhibited features characteristic of chaetoglobosin-ergosterol derivative hybrid. The NMR data revealed the presence of two terminal olefinic protons at δH 5.20 (s, 1H) and 5.42 (s, 1H), three carbonyl carbons at δC 198.4, 206.6, and 214.3, one amide carbonyl at δC 172.7. Compared to chaetoglobosin D (11), compound 3 lacked the C-21 double bond and the hydroxyl group at C-19 was replaced by a carbonyl group. Key HMBC correlations from H-21 to C-15′′ and from H-22 to C-6′′, C-8′′, and C-15′′, along with critical 1H-1H COSY cross-peaks between H-21/H-15′′ and H-22/H-7′′ (Fig. 5), supported a dimeric structure comprising chaetoglobosin D and 14-dehydroergosterol [35], connected via C-21 to C-15′′ and C-22 to C-7′′.

1H (600 MHz) and 13C (150 MHz) NMR data of compounds 3 and 4 in CDCl3

Based on the coupling constant between H-13 and H-14 and the NOESY correlation between H-8 and H-14, the double bond at C-13 was assigned as E-configuration. The NOESY correlation between H-16 and the methyl group H3-25 indicated that the double bond at C-16 was also E-configuration. The NOESY spectrum of 3 (Fig. 6) revealed key correlations, including H-3/H-7 and H-3/H-11, indicating that protons H-3, H-7, and H-11 were co-facial. Similarly, correlations of H-4/H-8, H-8/H-14, and H-14/H-16 supported the same orientation for protons H-4, H-8, and H-16. NOESY cross-peaks of H-1′′a/H-3′′, H-1′′a/H-9′′, H-22/H-9′′, H-9′′/H-12′′b, and H-12′′b/H-17′′ suggested that H-22, H-3′′, H-9′′, and H-17′′ shared the same spatial orientation. Additional correlations of H-7′′/H-15′′, H-7′′/H-19′′, H-11′′b/H-19′′, H-11′′b/H-18′′, and H-21/H-18′′ indicated that the protons at H-21, H-7′′, H-15′′, H-18′′, and H-19′′ were positioned on the same side. The coupling constants and NOESY correlations both indicated that 3 and 6 shared a highly similar configuration. Based on the established NOESY correlations and the similar chemical characteristics between 3 and 6, the relative configuration of 3 was assigned as 3S*, 4R*, 5S*, 7S*, 8R*, 9R*, 16S*, 21S*, 22S*, 3′′S*, 7′′S*, 9′′R*, 10′′R*, 13′′R*, 15′′R*, 17′′R*, 20′′R*, and 24′′R*.

Based on the relative configurations, and in combination with structural feature comparisons of chaetoglobosins and ergosterol derivatives derived from Chaetomium species, the absolute configuration of 3 was determined as 3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 21S, 22S, 3′′S, 7′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 15′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R. Subsequently, ECD calculations were performed on (3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 21S, 22S, 3′′S, 7′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 15′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R)-3, and the results were compared with the experimental ECD spectrum of 3. The comparison (Fig. 7) showed good agreement between the calculated and experimental data, supporting the assignment of the absolute configuration of 3 as 3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 21S, 22S, 3′′S, 7′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 15′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R.

Chalasoergodimer D (4) was isolated as a white powder. The molecular formula was determined as C60H76N2O6, corresponding to 24 degrees of unsaturation, based on the HRESIMS ion peak at m/z 943.5579 [M + Na]+ (C60H76N2O6Na+, calcd. for 943.5601). The 1H and 13C NMR signals (Table 2) of 4 were similar to 3. By comparison, the structure of 4 lacked the terminal alkene signal but displayed an additional methyl resonance at δH 1.74 (s, 3H). Key HMBC correlations from H-11 to C-4, C-5, and C-6, and from H-12 to C-5, C-6, and C-7 (Fig. 5), supported the presence of a double bond between C-5 and C-6, each substituted with a methyl group. Given the absence of significant differences in other structural elements, the planar structure of 4 was determined accordingly. Compound 4 exhibited highly similar NOESY correlations and coupling constants to those of 3. Since they shared the similar planar structure and chemical shifts overall, this suggested that they possessed similar configurations. Therefore, except for C-5, compound 4 was assigned the same relative configuration as 3. Based on the relative configurations, and in combination with structural feature comparisons of chaetoglobosins and ergosterol derivatives derived from Chaetomium species, the absolute configuration of 4 was suggested as 3S, 4R, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 21S, 22S, 3′′S, 7′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 15′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R. Moreover, the excellent agreement between the calculated and experimental ECD spectra (Fig. 7) supported the assignment of the absolute configuration of 4 as 3S, 4R, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 21S, 22S, 3′′S, 7′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 15′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R.

Chalasoergodimer E (5) was isolated as a white powder. The molecular formula was determined as C60H78N2O6, corresponding to 23 degrees of unsaturation, based on the HRESIMS ion peak at m/z 945.5745 [M + Na]+ (C60H78N2O6Na+, calcd. for 945.5758). Analysis of the 1D (Table 3) and 2D NMR data of 5 (Fig. 5), in comparison with 3, revealed that 5 and 3 shared highly similar structures, with the only difference being that 5 bore a hydroxyl group at C-19. Comparing of NOESY correlations (Fig. 6) and coupling constants confirmed that, except for C-19, the relative configuration of 5 was identical to that of 3. The NOESY correlations of H-19 with H-17, H-17 with H-15b, and H-15b with H3-24 indicated that H-19 and H3-24 were oriented on same side. In addition, the similar chemical shifts of H-19 in 5 and 6 suggested comparable chemical environments, which further supported the evaluation that the relative configuration of C-19 was likely the same in 5 and 6. Based on the relative configurations, and in combination with structural feature comparisons of chaetoglobosins and ergosterol derivatives derived from Chaetomium species, the absolute configuration of 5 was determined as 3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 19S, 21S, 22S, 3′′S, 7′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 15′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R. Moreover, the calculated ECD spectrum (Fig. 7) of (3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 19R, 21S, 22S, 3′′S, 7′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 15′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R)-5 exhibited good agreement with the experimental data of 5, thereby confirmed its absolute configuration as 3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 19R, 21S, 22S, 3′′S, 7′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 15′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R.

1H (600 MHz) and 13C (150 MHz) NMR data of compound 5 in CDCl3

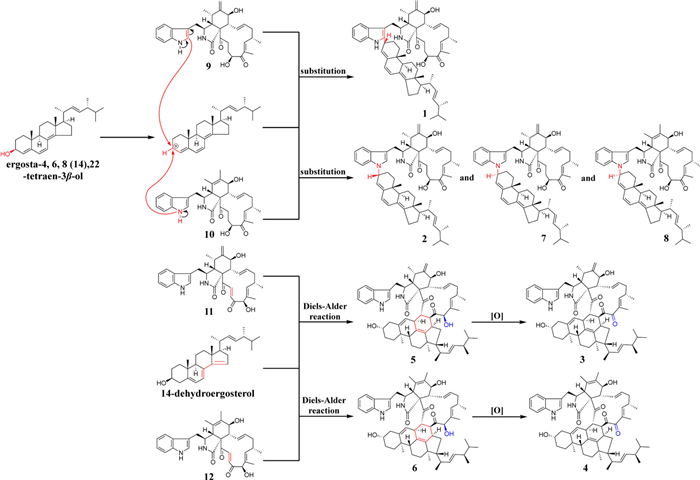

Based on the structures of compounds 1–12 and the currently reported studies on chaetoglobosin heterodimers [27, 36, 37], a possible biosynthetic pathway was proposed (Scheme 1). Compound 1 was likely formed via a substitution reaction between chaetoglobosin Fex (9) and ergosta-4, 6, 8(14), 22-tetraen-3β-ol. The electron-rich C-2′ position of the indole ring rendered it particularly susceptible to nucleophilic substitution by electron-deficient species. Compounds 2 and 7 were presumably generated through substitution at the HN-1′ position of the indole moiety. Notably, compounds 1 and 2, as well as 7, exhibited opposite configurations at C-3′, suggesting a possible unimolecular nucleophilic substitution mechanism. Given the structural similarity between 7 and 8, their dimerization was assumed to proceed via similar mechanisms. Compounds 5 and 6 likely arose from Diels–Alder cycloaddition reactions at C-21 and C-22 between chaetoglobosin D or B and 14-dehydroergosterol. In contrast, compounds 3 and 4 may originate from post-cyclization oxidation of 5 and 6.

The proposed biosynthetic pathways of 1–12

The possibility of an artificial reaction between chaetoglobosins and ergosterol analogues was evaluated. In these model experiments, cholesterol, which shared a similar structure with ergosta-4, 6, 8(14), 22-tetraen-3β-ol, and chaetoglobosin Fex were used. Equimolar mixtures of the two compounds were stirred at 55 ℃ for 12 h in methanol: dichloromethane solvents (1:0, 1:1, and 0:1, v/v). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis of the resulting mixtures revealed no significant formation of new products. Due to the lack of available ergosterol derivatives structurally similar to 14-dehydroergosterol, further experimental evaluation of the Diels–Alder cycloaddition pathway could not be conducted. Given the rarity of enzymatic nucleophilic substitution involving alcohols at the C-1′ or C-2′ positions of indole rings, compounds 1, 2, 7 and 8 were more likely biosynthesized through non-enzymatic pathways. Although the Diels–Alder cycloaddition represents a well-known class of natural product cyclizations, only a limited number of enzymes capable of catalyzing this reaction have been identified. Thus, the formation of 3, 4, 5, and 6 were also presumed to proceed via non-enzymatic mechanisms.

Chaetoglobosins have been reported to exhibit antitumor activity [38]. Accordingly, the cytotoxic activities of 1–12 against A549 cells were evaluated (Table S10). Compounds 9–12 showed notable inhibitory effects, with IC50 values of 9.26, 9.14, 14.89, and 5.14 μM. Cisplatin was selected as a positive control, with the IC₅₀ of 2.39 μM, slightly lower than that of compound 12. In contrast, compounds 1–8 displayed no significant cytotoxicity, possibly due to the increased molecular weight and reduced polarity resulting from polymerization with ergosterol derivatives, which may have hindered their membrane permeability and subsequent bioactivity.

3 Conclusion

New dimeric compounds with distinct polymerization patterns were identified, offering structure for active compound screening and advancing the understanding of potential dimerization modes between monomers. In this study, five new heterodimers (1–5), three known heterodimers (6–8), and four known chaetoglobosins (9–12) were isolated from the marine-derived fungus Chaetomium sp. Compound 1 featured a previously unreported polymerization mode between chaetoglobosin and ergosterol derivative, expanding the dimerization strategies of chaetoglobosin. Compound 2 possessed an R-configuration at the polymerization site, a structural feature not documented in related dimers. Cytotoxicity assays revealed that compounds 9–12 exhibited marked antitumor activity, with compound 12 showing the highest potency (IC50 = 5.14 μM).

4 Materials and methods

4.1 General experimental procedures

The OR results were measured using a JASCO P-2000 polarimeter. The ECD data were obtained with a MOS-450/SFM 300 instrument. The 1D and 2D NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance-Ⅲ 600 MHz spectrometer. The HRESIMS spectra were acquired using a Thermo Scientific LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer. The analysis and preparation of compounds were carried out using a Shimadzu LC-60AD semi-preparative HPLC, connected to an SPD-20A photodiode array detector and a Waters C18 column (10 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm). Other column chromatographies included silica gel columns (200–300 mesh) and Sephadex LH-20 (18–110 μm).

4.2 Fungal material and cultivation

The fungal strain used in this research was isolated from marine sediments of the Bohai Sea, China. It was identified as Chaetomium sp. based on ITS region amplification and sequencing (GenBank accession no. OR429403), and was preserved at Hebei University, China. The strain was initially cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium at 28℃ for 5 days. Subsequently, the fungal mycelia were cut into small pieces and transferred into sterilized 1L Erlenmeyer flasks, each containing 200 g of rice and 170 mL of water, and further incubated at 28 ℃ for 30 days. A total of 255 fungal fermentation batches were successfully obtained through screening and statistical analysis.

4.3 Isolation and purification

The fermentation product was extracted with a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of dichloromethane and methanol, yielding 2, 491 g of crude extract. The extract was partitioned between ethyl acetate and water (1:1, v/v), and the organic phase was collected. The ethyl acetate phase was concentrated and dried to yield 1, 259 g of crude extract. The ethyl acetate phase underwent silica gel column chromatography (CC), eluted stepwise with petroleum ether–ethyl acetate (80:20, 65:35, and 30:60, v/v), affording three primary fractions (Fr.1–Fr.3). Fraction 2 (Fr.2) was further purified over Sephadex LH-20 using petroleum ether–dichloromethane–methanol (2:1:1, v/v/v) to give subfractions Fr.2.1–Fr.2.4. Subfraction Fr.2.1 was subjected to silica gel CC and then semi-preparative HPLC on a Waters C18 column (100% MeOH) to afford compounds 1 (7.4 mg, 20.3 min), 2 (3.6 mg, 32.4 min), 7 (13.5 mg, 27.0 min), and 8 (9.1mg, 25.2 min). Subfraction Fr.2.2 was purified by Sephadex LH-20, followed by semi-preparative HPLC (100% MeOH) to yield compounds 3 (4.1 mg, 11.8 min), 4 (6.6 mg, 10.5 min), 5 (4.2 mg, 10.3 min), and 6 (5.4 mg, 12.5 min). Fraction 3 (Fr.3) was subjected to Sephadex LH-20 chromatography using a methanol–dichloromethane solvent system (1:1, v/v) to afford five subfractions (Fr.3.1–Fr.3.5). Subfraction Fr.3.2 was further purified by semi-preparative HPLC (55% MeCN/H2O) to yield compounds 9 (41.4 mg, 11.2 min) and 10 (31.9 mg, 12.9 min). Subfraction Fr.3.3 was purified by semi-preparative HPLC (50% MeCN/H2O) to afford compounds 11 (25.4 mg, 19.1 min) and 12 (35.3 mg, 20.5 min).

Chalasoergodimer A (1): brown power; [α]D25 + 269.9 (c 0.05, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 226 (4.60), 291 (4.46) nm; ECD (0.55 mM, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 229 (− 48.64), 297 (52.93) nm; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 929.5818 [M + Na]+ (C60H78N2O5Na+, calcd. for 929.5808).

Chalasoergodimer B (2): brown power; [α]D25 + 64.6 (c 0.10, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 226 (4.48), 291 (4.40) nm; ECD (0.55 mM, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 227 (− 10.76), 285 (10.08) nm; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 929.5811 [M + Na]+ (C60H78N2O5Na+, calcd. for 929.5808).

Chalasoergodimer C (3): white power; [α]D25 + 40.8 (c 0.10, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 219 (4.56), 261 (3.91) nm; ECD (0.27 mM, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 212 (− 21.21), 261 (5.41), 303 (− 4.60) nm; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 2; HRESIMS m/z 943.5598 [M + Na]+ (C60H76N2O6Na+, calcd. for 943.5601).

Chalasoergodimer D (4): white power; [α]D25 + 104.06 (c 0.10, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 220 (4.68), 260 (4.00) nm; ECD (0.27 mg/mL, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 260 (10.46), 305 (− 6.73) nm; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 2; HRESIMS m/z 943.5579 [M + Na]+ (C60H76N2O6Na+, calcd. for 943.5601).

Chalasoergodimer E (5): white power; [α]D25 − 126.37 (c 0.10, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 220 (4.64), 282 (3.84) nm; ECD (0.17 mM, MeOH) λmax (Δε) 209 (− 31.83), 216 (− 31.81), 307 (− 9.61) nm; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 3; HRESIMS m/z 945.5745 [M + Na]+ (C60H78N2O6Na+, calcd. for 945.5758).

4.4 Chemical calculations

The stereostructures of (3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 20S, 3′′R, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R)-1, (3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 20S, 3′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R)-1, (3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 20S, 3′′R, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R)-2, (3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 20S, 3′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R)-2, (3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 21S, 22S, 3′′S, 7′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 15′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R)-3, (3S, 4R, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 21S, 22S, 3′′S, 7′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 15′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R)-4, and (3S, 4R, 5S, 7S, 8R, 9R, 16S, 19R, 21S, 22S, 3′′S, 7′′S, 9′′R, 10′′R, 13′′R, 15′′R, 17′′R, 20′′R, and 24′′R)-5 were constructed using GaussView software. Conformational searches were constructed with the MMFF94s force field in Compute VOA software, and conformers with relative energies within 5.0 kcal/mol were selected. Geometry optimizations were performed at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level in Gaussian 09 [39]. Subsequently, ECD spectra and 13C NMR chemical shifts were calculated at the B3LYP/6-311 + G(d, p) level. The calculated results were averaged using Boltzmann-weighted populations and visualized with SpecDis 164 software [40].

4.5 Biological activity evaluation

The cytotoxicity of compounds 1–12 against A549 cells was evaluated using the MTT assay [41]. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/mL and incubated for 24 h. The test compounds were then added at various concentrations according to the experimental conditions, followed by further incubation. After 48 h, 10 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL, Biyotime, China) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37 ℃. After an additional 4 h, the culture medium was removed, and 100 μL of DMSO was added to each well. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a Multiskan FC microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Notes

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciated the financial support from the Yanzhao Golden Platform Talent Gathering Plan of Hebei Province (No. B2024005016), the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province of China (No. H2020201298), the Hebei University Research and Innovation Team (No. IT2023C1), the Excellent Youth Research Innovation Team of Hebei University (No. QNTD202406), the High Performance Computer Center of Hebei University.

Author contributions

CF and ZYH were responsible for designing the research concept. LZH, STT, and DHF conducted the experiments and processed the data. WX verified the structure elucidation. LS carried out the pharmacological activity assays. SHW, HLY, and YLK provided partial experimental conditions and suggestions. LZH wrote the manuscript, and CF and LDQ revised it. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript

Funding

This work was funded by the Yanzhao Golden Platform Talent Gathering Plan of Hebei Province (No. B2024005016), the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province of China (No. H2020201298), the Hebei University Research and Innovation Team (No. IT2023C1), the Excellent Youth Research Innovation Team of Hebei University (No. QNTD202406), the High Performance Computer Center of Hebei University.

Data availability

The data generated in this study were included in the article and its supplementary materials. The NMR data of compounds 1–5 have been deposited in the Natural Products Magnetic Resonance Database (NP-MRD; www.np-mrd.org) and can be found at NP0351258 (Chalasoergodimer A), NP0351259 (Chalasoergodimer B), NP0351260 (Chalasoergodimer C), NP0351261 (Chalasoergodimer D), NP0351262 (Chalasoergodimer E).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interest in this study.

References

-

1.Seshadri K, Abad AND, Nagasawa KK, Yost KM, Johnson CW, Dror MJ, Tang Y. Synthetic biology in natural product biosynthesis. Chem Rev 2025;125: 3814-931. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

2.Zou G, Yang WC, Chen T, Liu ZM, Chen Y, Li TB, Said G, Sun B, Wang B, She ZG. Griseofulvin enantiomers and bromine-containing griseofulvin derivatives with antifungal activity produced by the mangrove endophytic fungus Nigrospora sp. QQYB1. Mar Life Sci Technol 2024;6: 102-14. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

3.Ouranj ZD, Hosseini S, Alipour A, Homaeigohar S, Azari S, Ghazizadeh L, Shokrgozar M, Thomas S, Irian S, Shahsavarani H. The potent osteo-inductive capacity of bioinspired brown seaweed-derived carbohydrate nanofibrous three-dimensional scaffolds. Mar Life Sci Technol 2024;6: 515-34. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

4.Atanasov AG, Zotchev SB, Dirsch VM, Supuran CT. Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021;20: 200-16. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

5.Carter GT. Natural products and pharma 2011: strategic changes spur new opportunities. Nat Prod Rep 2011;28: 1783-9. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

6.Greule A, Stok JE, De Voss JJ, Cryle MJ. Unrivalled diversity: the many roles and reactions of bacterial cytochromes P450 in secondary metabolism. Nat Prod Rep 2018;35: 757-91. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

7.Zhang XW, Guo JW, Cheng FY, Li SY. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in fungal natural product biosynthesis. Nat Prod Rep 2021;38: 1072-99. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

8.Bouthillette LM, Aniebok V, Colosimo DA, Brumley D, Macmillan JB. Nonenzymatic reactions in natural product formation. Chem Rev 2022;122: 14815-41. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

9.Fan YQ, Shen JJ, Liu Z, Xia KY, Zhu WM, Fu P. Methylene-bridged dimeric natural products involving one-carbon unit in biosynthesis. Nat Prod Rep 2022;39: 1305-24. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

10.Quan KT, Park HB, Yuk H, Lee SJ, Na M. Paratrimerins j-y, dimeric coumarins isolated from the stems of Paramignya trimera. J Nat Prod 2021;84: 310-26. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

11.Nahar L, Sarker SD. A review on steroid dimers: 2011–2019. Steroids 2020;164: 108736. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

12.Wezeman T, Bräse S, Masters KS. Xanthone dimers: a compound family which is both common and privileged. Nat Prod Rep 2015;32: 6-28. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

13.Ma CT, Wang WX, Zhang KJ, Zhang FL, Chang YM, Sun CX, Che Q, Zhu TJ, Zhang GJ, Li DH. Exploring the diverse landscape of fungal cytochrome P450-catalyzed regio- and stereoselective dimerization of diketopiperazines. Adv Sci 2024;11: 2310018. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

14.Liu JW, Liu AA, Hu YC. Enzymatic dimerization in the biosynthetic pathway of microbial natural products. Nat Prod Rep 2021;38: 1469-505. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

15.Gao L, Su C, Du X, Wang R, Chen S, Zhou Y, Liu C, Liu X, Tian R, Zhang L, Xie K, Chen S, Guo Q, Guo L, Hano Y, Shimazaki M, Minami A, Oikawa H, Huang N, Houk KN, Huang L, Dai J, Lei X. FAD-dependent enzyme-catalysed intermolecular 4+2 cycloaddition in natural product biosynthesis. Nat Chem 2020;12: 620-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

16.Yan X, Zhang J, Tan H, Liu Z, Jiang K, Tian W, Zheng M, Lin Z, Deng Z, Qu X. A pair of atypical KAS Ⅲ homologues with initiation and elongation functions program the polyketide biosynthesis in asukamycin. Angew Chem Int Ed 2022;61: e202200879. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

17.Zhao S, Wu L, Xu Y, Nie Y. Fe(Ⅱ) and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases for natural product synthesis: molecular insights into reaction diversity. Nat Prod Rep 2025;42: 67-92. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

18.Mevers E, Saurí J, Helfrich EJN, Henke M, Barns KJ, Bugni TS, Andes D, Currie CR, Clardy J. Pyonitrins A-D: chimeric natural products produced by Pseudomonas protegens. J Am Chem Soc 2019;141: 17098-101. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

19.Du HF, Li L, Zhang YH, Wang X, Zhou CY, Zhu HJ, Pittman CU, Shou JW, Cao F. The first dimeric indole-diterpenoids from a marine-derived Penicillium sp. fungus and their potential for anti-obesity drugs. Mar Life Sci Technol 2025;7: 120-31. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

20.Fu P, Legako A, La S, Macmillan JB. Discovery, characterization, and analogue synthesis of bohemamine dimers generated by non-enzymatic biosynthesis. Chem Eur J 2016;22: 3491-5. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

21.Feng L, Wang X, Guo X, Shi L, Su S, Li X, Wang J, Tan N, Ma Y, Wang Z. Identification of novel target DCTPP1 for colorectal cancer therapy with the natural small-molecule inhibitors regulating metabolic reprogramming. Angew Chem Int Ed 2024;63: e202402543. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

22.Lv C, Huang Y, Wang Q, Wang C, Hu H, Zhang H, Lu D, Jiang H, Shen R, Zhang W, Liu S. Ainsliadimer a induces ROS-mediated apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells via directly targeting peroxiredoxin 1 and 2. Cell Chem Biol 2023;30: 295-307. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

23.Liu JY, Jiang YY, Li PJ, Yao B, Song YJ, Gao JX, Said G, Gao Y, Lai JY, Shao CL. Discovery of a potential bladder cancer inhibitor CHNQD-01281 by regulating EGFR and promoting infiltration of cytotoxic T cells. Mar Life Sci Technol 2024;6: 502-14. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

24.Li LX, Liu T, Zuo SY, Li YQ, Zhao ER, Lu Q, Wang DP, Sun YX, He ZG, Sun BJ, Sun J. Satellite-type sulfur atom distribution in trithiocarbonate bond-bridged dimeric prodrug nanoassemblies: achieving both stability and activatability. Adv Mater 2024;36: 2310633. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

25.Liu YF, Du HF, Zhang YH, Liu ZQ, Qi XQ, Luo DQ, Cao F. Chaeglobol A, an unusual octocyclic sterol with antifungal activity from the marine-derived fungus Chaetomium globosum HBU-45. Chin Chem Lett 2025;36: 109858. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

26.Yang MY, Wang YX, Chang QH, Li LF, Liu YF, Cao F. Cytochalasans and azaphilones: suitable chemotaxonomic markers for the Chaetomium species. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2021;105: 8139-55. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

27.Peng XG, Liu JJ, Qin CL, Wu Q, Li WP, Mohammadipanah F, Ruan HL. Ergochaeglobosins A-E, unprecedented heterodimers of cytochalasan and ergosterol from Chaeglobosin globosum P2-2-2. Chin J Chem 2022;40: 1909-16. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

28.Cui CM, Li XM, Li CS, Proksch P, Wang BG. Cytoglobosins a-g, cytochalasans from a marine-derived endophytic fungus, Chaetomium globosum QEN-14. J Nat Prod 2010;73: 729-33. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

29.Jiang T, Wang MH, Li L, Si JG, Song B, Zhou C, Yu M, Wang XW, Zhang YG, Ding G, Zou ZM. Overexpression of the global regulator LaeA in Chaetomium globosum leads to the biosynthesis of chaetoglobosin Z. J Nat Prod 2016;79: 2487-94. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

30.Pang Z, Sterner O. The isolation of ergosta-4, 6, 8(14), 22-tetraen-3β-ol from injured fruit bodies of Marasmius oreades. Nat Prod Lett 1993;3: 193-6. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

31.Rao QR, Rao JB, Zhao M. Chemical diversity and biological activities of specialized metabolites from the genus Chaetomium: 2013–2022. Phytochemistry 2023;210: 113653. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

32.Tian Y, Li YL. A review on bioactive compounds from marine-derived Chaetomium species. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2022;32: 541-50. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

33.Zhang Q, Li HQ, Zong SC, Gao JM, Zhang AL. Chemical and bioactive diversities of the genus Chaetomium secondary metabolites. Mini-Rev Med Chem 2012;12: 127-48. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

34.Fatima N, Muhammad SA, Khan I, Qazi MA, Shahzadi I, Mumtaz A, Hashmi MA, Khan AK, Ismail T. Chaetomium endophytes: a repository of pharmacologically active metabolites. Acta Physiol Plant 2016;38: 136. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

35.Ano Y, Ikado K, Shindo K, Koizumi H, Fujiwara D. Identification of 14-dehydroergosterol as a novel anti-inflammatory compound inducing tolerogenic dendritic cells. Sci Rep 2017;7: 14114. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

36.Peng XG, Duan FF, He YZ, Gao Y, Chen J, Chang JL, Ruan HL. Ergocytochalasin A, a polycyclic merocytochalasan from an endophytic fungus Phoma multirostrata XJ-2-1. Org Biomol Chem 2020;18: 4056-62. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

37.Li PK, Meng J, Zhang XT, Zhang XP, Ye YH, Zhao YP, Huang XN, Zha Z, Guan ZH, Lai ST, Chen Z, Luo ZW, Wang JP, Chen CM, Liu JJ, Gu LH, Sun YH, Li SM, Zhu HC, Ye Y, Zhou Y, Zhang YH. Cooperative redox reactions encoded by two gene clusters enable intermolecular cycloaddition cascade for the formation of meroaspochalasins. Angew Chem Int Ed 2025;64: e202502766. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

38.Li B, Gao Y, Rankin GO, Rojanasakul Y, Cutler SJ, Tu YY, Chen YC. Chaetoglobosin k induces apoptosis and G2 cell cycle arrest through p53-dependent pathway in cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Lett 2015;356: 418-33. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

39.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, et al. Gaussian 09. Wallingford, CT, USA: Gaussian Inc.; 2009. PubMed Google Scholar

-

40.Bruhn T, Schaumlöffel A, Hemberger Y, Bringmann G. Specdis: quantifying the comparison of calculated and experimental electronic circular dichroism spectra. Chirality 2013;25: 243-9. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

41.Han MQ, Zhao YJ, Pang S, Zhu HJ, Luo DQ, Liu YF, Yang K, Cao F. Modulating culture method promotes the production of disulfide-linked resorcylic acid lactone dimers with anti-proliferative activity. Bioorg Chem 2025;159: 108418. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© The Author(s) 2025

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.