Synthesis and biological activity study of tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salt derivatives

Abstract

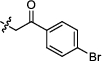

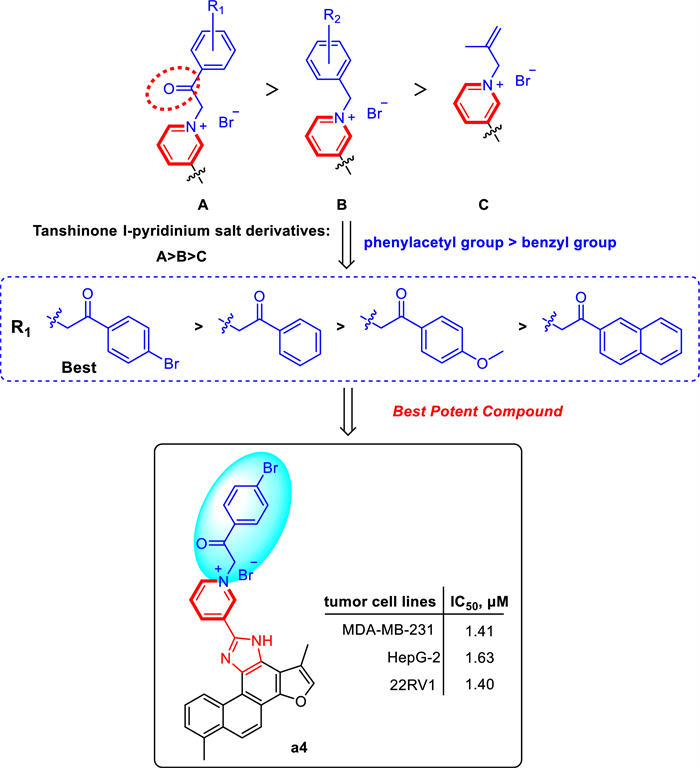

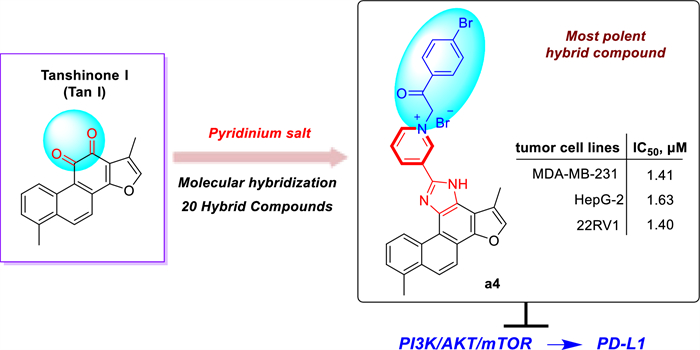

Natural product tanshinone Ⅰ exhibits weak potency and poor drug-like properties, which have restricted its clinical development as an anticancer agent. Herein, twenty novel tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salt derivatives and a pyridinium salt precursor were designed and synthesized, and their antitumor activities were evaluated. Among these tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salts, compound a4, bearing a 4-bromobenzoylmethyl substituent at the N-1 position of the pyridine ring, showed the most potent cytotoxicity against breast cancer (MDA-MB-231), hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), and prostate cancer (22RV1) cell lines, with IC50 values of 1.40–1.63 μM. Preliminary mechanistic studies suggest that a4 targets PI3Kα with the IC50 of 9.24 ± 0.20 μM and exerts effective inhibition of the phosphorylation of key PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling proteins. Besides, a4 significantly downregulates the expression of the immune checkpoint protein PD-L1, indicating its potential to activate tumor immunity. These findings demonstrate that tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salt derivative a4 is a novel PI3Kα inhibitor, providing a solid foundation for further development of antitumor agents.Graphical Abstract

Keywords

Tanshinone Ⅰ Pyridinium salts Structural modification Antitumor activity Structure–activity relationship1 Introduction

Cancer is a complex genomic disorder characterized by significant heterogeneity and drug resistance, greatly complicating its treatment [1]. Although current therapeutic strategies, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, have improved patient survival to some extent, their clinical effectiveness remains limited by poor selectivity, significant toxicity, and acquired drug resistance [2]. Thus, developing novel anticancer agents with high selectivity and low toxicity remains in great demand for current medicinal chemistry research [3, 4].

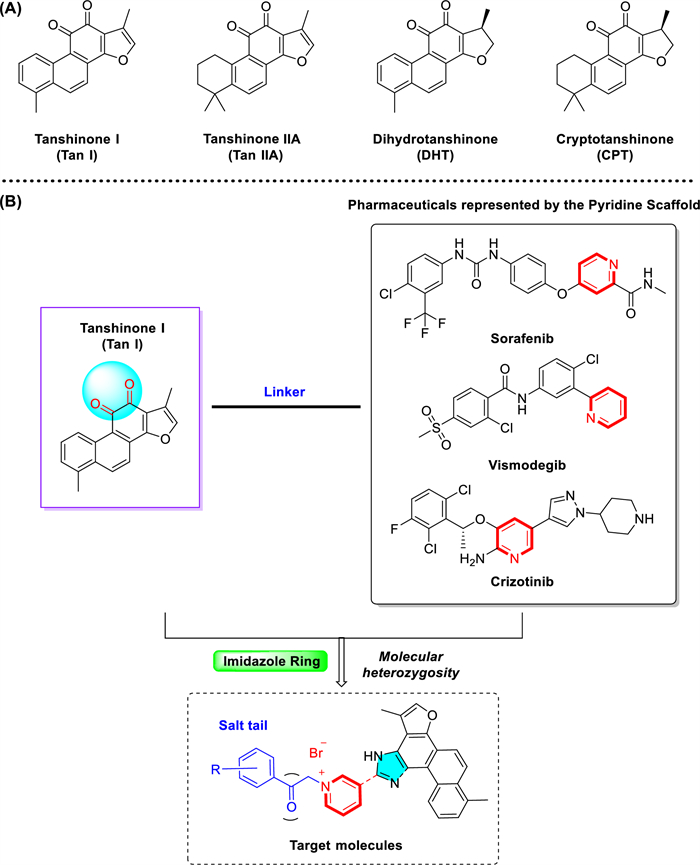

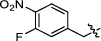

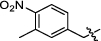

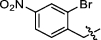

Natural products, particularly those derived from traditional Chinese medicines, have long served as valuable sources for anticancer drug discovery due to their structural diversity and multi-targeted effects [5, 6]. Salvia miltiorrhiza, a widely-used traditional Chinese medicinal herb for cardiovascular diseases, contains bioactive constituents known as tanshinones that have exhibited potential anticancer activity [7]. Tanshinones, such as tanshinone Ⅰ (Tan Ⅰ), tanshinone ⅡA (Tan ⅡA), dihydrotanshinone (DHT) and cryptotanshinone (CPT), exhibit multiple anticancer mechanisms, including anti-proliferative effects, apoptosis induction, immune modulation, and angiogenesis inhibition [8-14] (Fig. 1A). Among these, tanshinone Ⅰ (T1), despite its relatively low abundance and limited research, has demonstrated prominent inhibitory effects against various cancers, including breast, liver, and prostate cancer [15-18]. However, the clinical application of tanshinone Ⅰ has been restricted by its low aqueous solubility, poor bioavailability, and unfavorable pharmacokinetic properties [19-21].

Tanshinone molecular heterozygous design of tanshinone Ⅰ. A Representative tanshinones extracted from Salvia miltiorrhiza. B Molecular heterozygous design of the natural product tanshinone Ⅰ with pyridinium salt for drug discovery

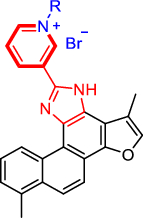

To enhance its solubility, bioavailability, anticancer activity, and selectivity, structural modification of tanshinone through molecular hybridization by incorporating pharmacophores such as pyridinium salt has been performed in the study [22-25]. Pyridine moieties are widely present in numerous FDA-approved anticancer drugs due to their favorable electronic properties and hydrogen bond acceptor capabilities, which can enhance pharmacokinetic profiles and molecular interactions [26-28]. It has been reported that over 20% of small-molecule anticancer agents contain a pyridine ring or its derivatives. Representative examples include Sorafenib, Vismodegib, and Crizotinib (Fig. 1B). Based on this rationale, we introduced an imidazole linker into ring C of Tan I and synthesized a series of novel tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salt derivatives, whose anticancer activities and preliminary mechanisms were systematically investigated [29, 30]. This study not only expands structural diversity and biological applications of tanshinone derivatives but also provides new directions for the development of novel anticancer agents.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Chemistry

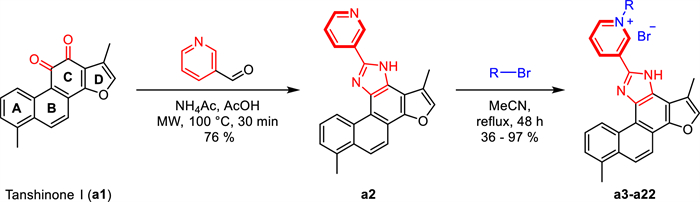

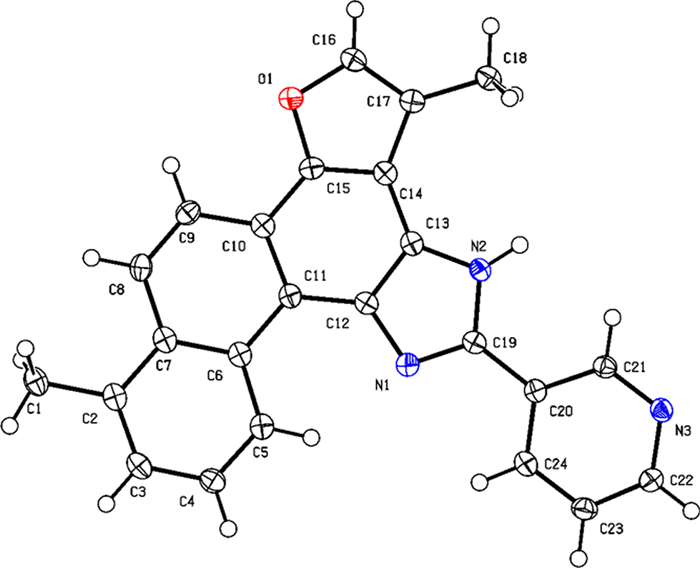

As shown in Scheme 1, tanshinone Ⅰ (a1) is structurally characterized by a naphthalene ring A/B, an ortho-quinone ring C, and a furan ring D. To enhance aqueous solubility and molecular stability, structural modification of tanshinone Ⅰ was performed by introducing an imidazole moiety as a linker onto ring C and a pyridine ring to form the salt, using commercially available tanshinone Ⅰ (a1) as the starting material. Specifically, pyridine derivative a2 was synthesized via the Debus-Radziszewski reaction of a1 with 3-pyridinecarboxaldehyde in acetic acid and ammonium acetate under microwave irradiation (100 ℃). Single crystals of compound a2 were obtained by solvent crystallization, and the structure of a2 was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis (CCDC 2447458, Fig. 2). Subsequent quaternization of pyridine derivative a2 with various alkyl bromides in acetonitrile afforded a series of tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salts (a3-a22) in yields ranging from 36 to 97%. To summarize, the structures and yields of all new tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salts derivatives were shown in Table 1.

Synthesis of tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salts Derivatives a3-a22

X-ray crystal structure of compound a2

Structures and yields of tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salts Derivatives a3-a22

2.2 Biological evaluation and structure–activity relationship analysis

2.2.1 Biological assay procedures and results

Twenty synthesized tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salt derivatives (a3-a22), together with tanshinone Ⅰ (a1) and pyridine derivative (a2), were evaluated in vitro for their cytotoxic activity against three human cancer cell lines, including breast cancer (MDA-MB-231), hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), and prostate cancer (22RV1), by using the MTS assay. Cisplatin (DDP) and paclitaxel were chosen as positive controls. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Cytotoxic activities of tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salts Derivatives a3-a22 in vitrob (IC50, µMa)

2.2.2 Aqueous solubility analysis

The aqueous solubility of selected analogues exhibiting enhanced antitumor activity (a2, a4, and a16) was evaluated by a previously reported ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectrophotometric method [31]. As anticipated, the conversion of these derivatives into their corresponding pyridinium salts significantly improved their aqueous solubility compared to the parent compound a1. Specifically, the pyridinium salts a4 and a16 demonstrated notably higher solubilities (85 ± 4 μg/mL and 86 ± 5 μg/mL, respectively) relative to their non-salt precursor a2 (32 ± 5 μg/mL). These findings highlight the beneficial impact of pyridinium salt formation on enhancing the aqueous solubility of the synthesized compounds. By comparison, the aqueous solubility of compound a1 was too low to be accurately determined by this method (literature-reported solubility < 0.1 μg/mL [21]).

2.2.3 Structure–activity relationship analysis

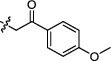

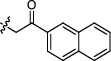

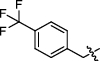

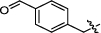

As presented in Table 2, the majority of tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salt derivatives showed the potential inhibitory activity. A series of newly synthesized tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salt derivatives displayed markedly higher in vitro cytotoxic activity than the unmodified parent compound (a1), indicating that incorporation of a pyridinium moiety is critical for enhancing the anticancer activity of tanshinone Ⅰ. Specifically, the nature of the substituent at the N-1 position of the pyridine ring profoundly influenced antitumor potency. Pyridinium salts bearing an acyl-linked substituent at N-1 (e.g., a benzoylmethyl group) were significantly more potent than those with benzyl or alkyl linkers. Notably, the pyridinium salt derivative with a 4-bromobenzoylmethyl substituent (a4) exhibited the best potent cytotoxic activity (IC50 = 1.40–1.63 µM). Moreover, the electron-withdrawing 4-bromobenzoylmethyl group (a4) conferred greater potency than the electron-donating 4-methoxybenzoylmethyl substituent (a5), demonstrating that electron-withdrawing substituent was more favorable for cytotoxic activity. In addition, compounds with a single aromatic-ring substituent generally showed higher activity than those with disubstituted rings, and the substituent’s position had a pronounced effect. For example, the 2-bromobenzyl derivative (a9) exhibited higher potency than the 2-bromo-4-nitrobenzyl derivative (a19). Furthermore, the meta-substituted analog (a7) was significantly more active than the ortho-substituted counterpart (a15), this highlights the importance of substituent position. Additionally, naphthalene analogs featuring an acylmethyl linker were more active than those lacking this moiety, further highlighting the key influence of linker structure on cytotoxic potency. Conversely, an aliphatic substituent (isobutenyl in a22) yielded much lower activity than aromatic substituents, indicating that such chain substituents provide limited benefit for antitumor potency.

In summary, SAR analysis demonstrates that introducing a pyridinium fragment is pivotal for boosting the activity of tanshinone Ⅰ derivatives. The linkage mode of the N-1 substituent, the electronic nature and position of aromatic substituents significantly impact in vitro cytotoxic activity. These results offer an important theoretical basis for further structural optimization. The preliminary structure activity relationships (SARs) of the pyridinium salt derivatives were summarized in Scheme 2.

Structure–activity relationships (SARs) of tanshinone Ⅰ Derivatives

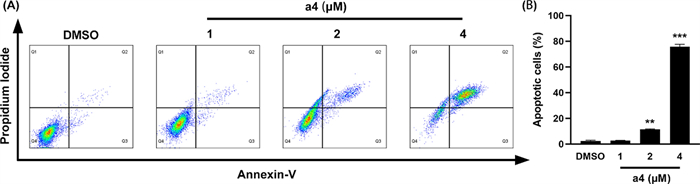

2.3 Compound a4 induces apoptosis and migration

To elucidate the potential mechanism underlying the antiproliferative effect of compound a4, cell cycle progression and apoptosis were analyzed by flow cytometry. Compound a4 induced apoptosis by was assessed using Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining assay. As shown in Fig. 3, treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells with compound a4 at 1, 2, and 4 μM for 48 h significantly increased apoptosis rates to 2.69%, 11.48%, and 75.81%, respectively. These results indicate that compound a4 induced apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose-dependent manner.

Compound a4 induced apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 cells. A Cells were treated with 1, 2 and 4 μM compound a4 for 48 h. Cell apoptosis was determined by Annexin V-FITC/Propidium Iodide staining analysis. B The quantification of apoptotic cells

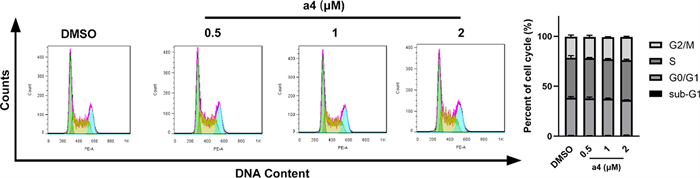

Further, the effect of compound a4 on the cell cycle distribution of MDA-MB-231 cells was investigated at concentrations of 0.5, 1, and 2 μM. Cell cycle analysis by PI staining and flow cytometry revealed that compound a4 caused no significant cell cycle arrest in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 4). Collectively, apoptosis induction rather than cell cycle arrest primarily contributed to its anticancer activity of compound a4.

Compound a4 did not induce significant cell cycle arrest in MDA-MB-231 cells. A Cells were treated with different concentrations of compound a4 (0.5 μM, 1 μM, 2 μM) for 24 h, and cell cycle was determined by cell cytometry with PI staining. B The percentages of cells in different phases were quantified

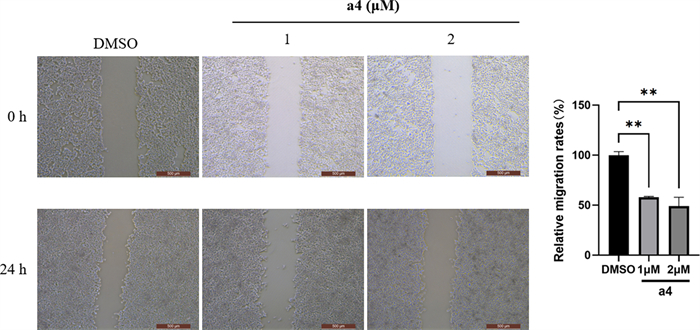

Scratch wound healing assay was conducted to test whether a4 impaired the migration of MDA-MB-231 cells. The migration rates at 24 h of MDA-MB-231 cells decreased with the increasing a4 in Fig. 5.

Compound a4 inhibited migration of MDA-MB-231 cells. MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to a4, and the migration was evaluated with wound healing assay, with the representative images were taken and relative migration rates were calculated respectively. Scale indicates 500 μm

2.4 Compound a4 suppresses PI3K/mTOR and PD-L1

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling ranks one of the most frequently dysregulated signaling pathways in cancer by promoting tumor initiation and progression [32, 33]. Further, abnormal PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway activation resulted PD-L1 increase facilitates the escape of cancer cells from the immunosurveillance of immune system [34]. Thus, the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling components such as PI3K and mTOR are potential therapeutic targets in cancer, and the identification of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling inhibitors have drawn extensive attention. In particular, the PI3K has four subtypes (α/β/γ/δ), while overexpression and mutation resulted abnormal activation of PI3Kα is closely to the progression of solid cancers, therefore, PI3Kα has become a key target for the development of anticancer drugs. To date, alpelisib is the only PI3Kα inhibitor approved for the treatment of breast cancer, and several other PI3Kα inhibitors are under evaluation in clinical trials [35], which give us proposal for the development of novel PI3Kα inhibitors for tumor therapy.

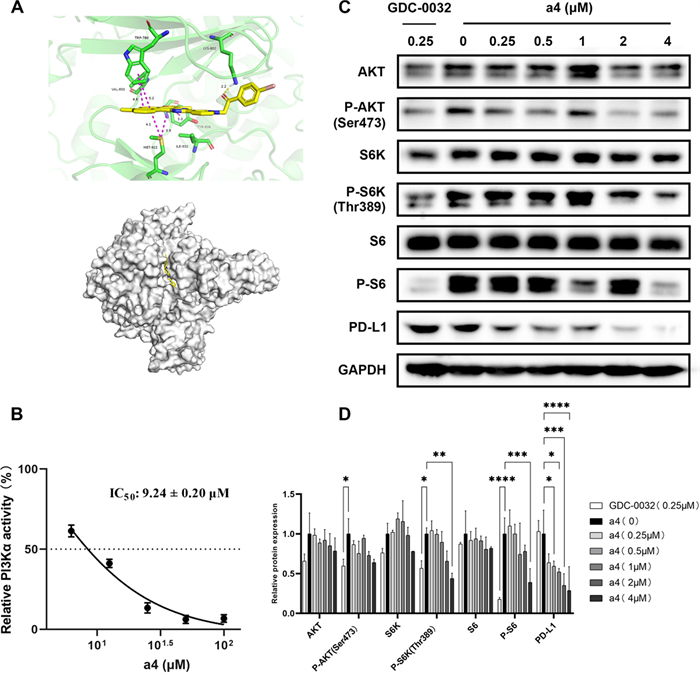

To further elucidate the underlying mechanism of compound a4, molecular docking analysis was performed to identify potential target-proteins and subsequent biological experiments were conducted to confirm the precise target predicted. Molecular docking analysis of compound a4 with putative targets revealed strong binding affinities toward PI3Kα (Fig. 6A). The compound binds within the PI3Kα active site, forming a hydrogen bond (2.2 Å) between its benzoyl oxygen and the LYS802 residue. The conjugated polycyclic framework of compound a4 contributes significantly to binding through multiple π-π stacking interactions: two with the benzene ring of TPR780 (4.8 Å and 5.2 Å) and one with TYR836 involving the compound’s furan ring (5.0 Å). Additionally, hydrophobic π-sulfur interactions are observed between the conjugated system of compound a4 and the sulfur atom of MET922 (4.1 Å and 3.9 Å).

Compound a4 of mechanistic studies. (A) Molecular docking of PI3Kα protein (PDB ID: 4JPS). (B) The compound a4 inhibits the PI3Kα activity. (C) PI3K regulates downstream signaling pathways and PD-L1 protein expression. (D) Statistical analysis of the Western blot experimental section, The asterisk (*) represents a statistically significant difference when compared to indicated sample (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001). Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) of the mean

To further confirm the interaction of a4 and PI3Kα, the PI3Kα inhibitory of a4 was performed. As shown in Fig. 6B, a4 inhibited PI3Kα in a dose dependent manner, with an IC50 of 9.24 ± 0.20 μM, indicating a4 was a novel PI3Kα inhibitor. Subsequent western blot analysis demonstrated that compound a4 exerts dual regulatory effects on the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and tumor immune microenvironment by analyzing key signaling proteins and immune checkpoint molecules (Fig. 6C, D). Using the PI3K inhibitor GDC0032 as a positive control, Western blot results demonstrated that a4, while showing no impact on total protein levels of AKT, S6K, or S6, exerted concentration-dependent inhibition on phospho-AKT (Ser473), phospho-S6K (Thr389), and phospho-S6 (Ser235/236), indicating a4 effectively blocks PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. Notably, a4 exhibited enhanced PD-L1 downregulation. These findings establish a “pathway inhibition-immunoactivation” synergy, offering a novel therapeutic strategy against tumor immune evasion.

3 Conclusion

In summary, we have successfully designed and synthesized a series of novel tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium salt derivatives. This method enabled the rapid construction of structurally diverse tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium hybrid molecules, and in vitro activity evaluation demonstrated that these derivatives exhibit potential antitumor activity. Notably, SARs revealed that the pyridinium moiety was identified as the critical structural feature responsible for the enhanced in vitro cytotoxic activity of the tanshinone Ⅰ derivatives. Compound a4, featuring a 4-bromobenzoylmethyl substituent at the N-1 position of the pyridine ring, was the most active derivative in the series, with IC50 values of 1.41, 1.63 and 1.40 μM against human cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231, HepG2 and 22RV1, respectively, indicating that a4 exhibited the most potent antitumor activity among all derivatives. Meanwhile, compound a4 demonstrated markedly improved aqueous solubility (85 μg/mL). Furthermore, cell cycle, apoptosis and migration studies indicated that a4 induces cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and migration inhibition in the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line in a markedly dose-dependent manner. Preliminary mechanistic studies suggest that compound a4 is a novel PI3Kα inhibitor and exerts its antitumor effects through a dual mechanism. On one hand, it effectively inhibits the phosphorylation of downstream key proteins in the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway; on the other hand, it significantly downregulates the expression of the immune checkpoint protein PD-L1. These findings not only provide an efficient structural optimization strategy for the development of tanshinone Ⅰ-based anticancer agents, but also suggest that compound a4 is a promising candidate for further antitumor studies.

4 Methods and materials

4.1 Chemistry experimental materials

Melting points were obtained and uncorrected on a Haineng melting-point apparatus. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 and Bruker Avance 600 spectrometers at 400 MHz and 600 MHz. Carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance (13C-NMR) was recorded on Bruker Avance 400 spectrometer at 100 MHz. Carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance (13C-NMR) was recorded on Bruker Avance 600 spectrometer at 150 MHz. Chemical shifts are reported as δ values in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS) for all recorded NMR spectra. High Resolution Mass spectra were taken on Thermo Fisher LC-MSO/TOR mass spectrometer. Silica gel (200–300 mesh) for column chromatography and silica GF254 for TLC were produced by Qingdao Marine Chemical Company (China). All air- or moisture- sensitive reactions were conducted under an argon atmosphere. Starting materials and reagents used in reactions were obtained commercially from TCI, Adamas, Aladdin, Bidepharm and were used without purification, unless otherwise indicated. Purity of all compounds was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using an Agilent instrument.

4.2 Synthesis of compounds a2-a22

4.2.1 Synthesis of compounds a2

Compound a1 (0.10 g, 0.36 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL of analytical-grade acetic acid in a 50 mL microwave tube. Ammonium acetate (0.11 g, 1.45 mmol) was added, followed by the dropwise addition of 3-pyridinecarbaldehyde (0.051 mL, 0.54 mmol) at room temperature. The mixture was stirred for 10 min, then heated to 100 ℃ in a microwave reactor and maintained for 1 h. After cooling to room temperature, the solution was transferred to a 100 mL round-bottom flask and neutralized to pH 7 using saturated aqueous NaOH. The neutralized mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 30 mL), and the aqueous phase was further extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, eluent: dichloromethane/ethyl acetate = 10:1 → 5:1, v/v, containing 1% (v/v) formic acid) to afford a2 as yellow powder in 76% yield. (Experimental findings & Structural elucidation of a2 are included in the Supporting information)

4.2.1.1 1, 6-dimethyl-11-(pyridin-3-yl)-12H-furo[2', 3':1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d] imidazole (a2)

Yield 76%. Yellow powder, m.p. 288–289 ℃. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.74 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 9.58 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.79 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.62 (dd, J = 4.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (dd, J = 8.4, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (dd, J = 8.4, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.70 (s, 3H), 2.60 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 150.0, 149.0, 148.2, 146.8, 146.7, 142.1, 136.7, 134.5, 134.0, 130.6, 130.3, 127.2, 126.8, 126.6, 126.5, 123.9, 122.1, 119.2, 119.0, 115.9, 115.6, 112.9, 20.0, 10.0 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C24H18N3O [M + H]+ 364.1444, found 364.1447. HPLC purity: 98.6%.

4.2.2 Synthesis of compounds a3-a22

Compound a2 (0.05 g, 0.14 mmol) was charged into a 50 mL round-bottom flask and dissolved in ultra-dry acetonitrile (20 mL). The mixture was heated under reflux at 100 ℃ for 12 h until complete dissolution of a2 was achieved. Subsequently, various bromides (5.0 equiv relative to a2) were introduced sequentially, each dissolved in ultra-dry acetonitrile (20 mL per 50 mg substrate). The reaction mixtures were refluxed with stirring for an additional 24–48 h and monitored by TLC. Upon completion, solvents were removed under reduced pressure, and the precipitated solid was collected by filtration, thoroughly washed with ethyl acetate (3 × 60 mL), and dried under vacuum at 60 ℃ to afford tanshinone Ⅰ-pyridinium derivatives a3-a22 as yellow powder in 36–97% yields. (Structural determination for representative derivative a4 is detailed in the Supporting information)

4.2.2.1 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(2-oxo-2-phenylethyl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a3)

Yield 85%. Yellow powder, m.p. 287–288 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3429, 3048, 2959, 1703, 1624, 1449, 1369, 1341, 1319, 1218, 1087, 798, 780, 704, 685, 590. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.67 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 9.96 (s, 1H), 9.49 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.07 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.49 (dd, J = 8.0, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.34 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.20—8.13 (m, 3H), 8.04 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.89—7.82 (m, 1H), 7.75 – 7.66 (m, 3H), 7.51 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 6.71 (s, 2H), 2.76 (s, 3H), 2.61 (s, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 190.8, 149.6, 145.4, 144.4, 142.4, 142.4, 142.3, 136.7, 135.0, 134.1, 133.6 130.6, 130.2, 130.0, 129.2, 128.4, 127.8, 127.3, 126.9, 126.8, 126.7, 122.7, 119.2, 118.8, 116.4, 115.4, 112.5, 66.9, 19.9, 9.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C32H24N3O2 [M]+ 482.1863, found 482.1867. HPLC purity: 97.7%.

4.2.2.2 1-(2-(4-bromophenyl)-2-oxoethyl)-3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2', 3':1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a4)

Yield 76%. Yellow powder, m.p. 268–269 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3429, 3040, 2951, 1702, 1584, 1396, 1336, 1216, 1098, 998, 821, 727, 705, 688, 591. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.48 (s, 1H), 10.68 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.96 (s, 1H), 9.52 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.06 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (dd, J = 8.4, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 8.06 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.69 (dd, J = 8.4, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.69 (s, 2H), 2.77 (s, 3H), 2.63 (s, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 190.2, 149.6, 145.4, 144.4, 142.5, 142.4, 142.4, 136.7, 134.1, 132.7, 132.4, 130.6, 130.4, 130.3, 130.0, 129.0, 127.8, 127.3, 127.0, 126.7, 126.6, 122.7, 119.2, 118.8, 116.4, 115.4, 112.5, 66.8, 19.9, 9.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C32H23O2N3Br [M]+ 560.0968, found 560.0973. HPLC purity: 98.1%.

4.2.2.3 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-oxoethyl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a5)

Yield 90%. Yellow powder, m.p. 326–327 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3419, 3048, 2943, 1688, 1623, 1598, 1263, 1174, 1022, 838, 704, 678, 593. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.53 (s, 1H), 10.71 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 9.97 (s, 1H), 9.54 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.08 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (dd, J = 7.8, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.37 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 8.08 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.71—7.67 (m, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.65 (s, 2H), 3.93 (s, 3H), 2.78 (s, 3H), 2.64 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 189.0, 164.4, 149.6, 145.5, 144.5, 142.6, 142.5, 142.3, 142.1, 136.7, 134.2, 130.9, 130.6, 130.3, 130.0, 127.8, 127.3, 127.0, 126.8, 126.6, 126.4, 126.4, 122.7, 119.2, 118.8, 116.5, 115.4, 114.5, 112.6, 66.7, 55.9, 19.9, 9.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C33H26N3O3 [M]+ 512.1969, found 512.1965. HPLC purity: 96.1%.

4.2.2.4 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2', 3':1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(2-(naphthalen-2-yl)-2-oxoethyl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a6)

Yield 36%. Yellow powder, m.p. 292–293 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3423, 3051, 2922, 1698, 1624, 1467, 1357, 1316, 1278, 1176, 1146, 866, 821, 705, 677. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.63 (s, 1H), 10.74 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 10.05 (s, 1H), 9.61 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 9.14 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.94 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (dd, J = 8.4, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.40 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 8.14—8.11 (m, 3H), 7.81—7.78 (m, 1H), 7.76—7.73 (m, 1H), 7.68 (dd, J = 8.4, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (s, 2H), 2.78 (s, 3H), 2.68 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 191.1, 150.1, 146.0, 145.1, 143.2, 143.0, 137.3, 136.2, 134.7, 132.5, 131.4, 131.3, 131.1, 130.9, 130.5, 130.3, 130.1, 129.4, 128.5, 128.4, 128.1, 127.8, 127.5, 127.2, 127.0, 123.8, 123.2, 119.7, 119.3, 117.0, 115.9, 113.1, 67.4, 20.3, 10.2 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C36H26N3O2 [M]+ 532.2020, found 532.2020. HPLC purity: 95.9%.

4.2.2.5 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(3-methylbenzyl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a7)

Yield 67%. Yellow powder, m.p. 280–281 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3377, 3006, 1590, 1397, 1302, 1161, 819, 712, 593. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.57 (s, 1H), 10.06 (s, 1H), 9.30 (s, 1H), 9.21 (s, 1H), 8.34 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.96 (s, 1H), 7.67 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (s, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 6.05 (s, 2H), 2.74 (s, 3H), 2.57 (s, 3H), 2.38 (s, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO) δ 149.8, 144.0, 142.9, 142.6, 142.1, 139.2, 136.9, 134.4, 134.4, 131.2, 130.9, 130.6, 130.3, 130.1, 129.7, 128.7, 127.6, 127.0, 126.9, 126.7, 122.8, 119.4, 119.2, 116.7, 115.8, 113.0, 64.0, 21.4, 20.3, 10.3. ppm; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C32H26N3O [M]+ 468.2070, found 468.2074. HPLC purity: 97.6%.

4.2.2.6 1-(2-cyanobenzyl)-3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a8)

Yield 84%. Yellow powder, m.p. 285–286 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3426, 3069, 3028, 2961, 2919, 2854, 2223, 1878, 1624, 1489, 1456, 1314, 1146, 816, 773, 702, 686. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.54 (s, 1H), 10.68 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 10.06 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 9.51 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 9.22 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (dd, J = 7.8, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.07 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (td, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.74—7.67 (m, 3H), 7.55 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.37 (s, 2H), 2.78 (s, 3H), 2.63 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 149.6, 144.2, 143.6, 142.5, 142.4, 142.2, 137.0, 136.7, 134.3, 134.1, 134.0, 130.9, 130.6, 130.2, 130.0, 129.8, 128.7, 127.3, 127.0, 126.7, 126.6, 122.8, 119.1, 118.8, 117.1, 116.5, 115.4, 112.6, 111.5, 61.9, 19.9, 9.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C32H23N4O [M]+ 479.1866, found 479.1870. HPLC purity: 97.9%.

4.2.2.7 1-(2-bromobenzyl)-3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a9)

Yield 69%. Yellow powder, m.p. 260–261 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3423, 3083, 3006, 2933, 2860, 1805, 1627, 1491, 1473, 1371, 1165, 1048, 1027, 812, 757, 679. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.55 (s, 1H), 10.62 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.98 (s, 1H), 9.51 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.19 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.46 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.37 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (s, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.63—7.55 (m, 3H), 7.51 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.19 (s, 2H), 2.79 (s, 3H), 2.64 (s, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 149.6, 144.2, 143.1, 142.5, 142.4, 142.1, 136.7, 134.2, 133.6, 133.1, 131.8, 131.6, 130.7, 130.6, 129.9, 128.9, 128.6, 127.4, 127.0, 126.7, 126.5, 123.6, 122.8, 119.1, 118.8, 116.5, 115.4, 112.6, 63.7, 19.9, 9.7 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C31H23N3OBr [M]+ 532.1019, found 532.1024. HPLC purity: 98.9%.

4.2.2.8 1-(4-bromobenzyl)-3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a10)

Yield 89%. Yellow powder, m.p. 285–286 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3382, 3091, 3037, 2993, 2927, 1904, 1584, 1484, 1442, 1351, 1169, 1071, 838, 814, 649. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.57 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 10.07 (s, 1H), 9.30 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 9.21 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.35 (dd, J = 8.4, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.00—7.94 (m, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.68 (dd, J = 8.8, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 6.09 (s, 2H), 2.74 (s, 3H), 2.56 (s, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 149.5, 143.7, 142.7, 142.2, 141.7, 136.5, 134.0, 133.3, 132.3, 131.6, 130.6, 130.5, 129.9, 128.4, 127.2, 126.7, 126.6, 123.2, 122.5, 119.0, 118.7, 116.3, 115.3, 112.4, 62.8, 19.9, 9.9 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C31H23N3OBr [M]+ 532.1019, found 532.1022. HPLC purity: 98.0%.

4.2.2.9 1-(4-chlorobenzyl)-3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a11)

Yield 92%. Yellow powder, m.p. 261–262 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3422, 3092, 3038, 2923, 2853, 1629, 1594, 1489, 1399, 1283, 1143, 1088, 842, 776, 700, 677. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.59 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 10.08 (s, 1H), 9.32 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.21 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (dd, J = 8.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.83—7.76 (m, 2H), 7.71—7.66 (m, 1H), 7.66—7.62 (m, 2H), 7.50 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 6.11 (s, 2H), 2.75 (s, 3H), 2.58 (s, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 149.5, 143.7, 142.7, 142.3, 141.8, 136.5, 134. 5, 134.0, 132.9, 131.4, 130.6, 130.5, 129.9, 129.4, 128.4, 127.2, 126.8, 126.6, 122.6, 119.0, 118.7, 116.4, 115.3, 112.5, 62.7, 19.9, 9.9 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C31H23ON3Cl [M]+ 488.1524, found 488.1526. HPLC purity: 96.2%.

4.2.2.10 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(4-fluorobenzyl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a12)

Yield 97%. Yellow powder, m.p. 276–277 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3426, 3009, 2941, 1627, 1591, 1526, 1318, 1228, 1160, 1144, 818, 773, 707, 684. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.63 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 10.08 (s, 1H), 9.38 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.22 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.38 (dd, J = 8.4, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.33 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.04 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.87—7.81 (m, 2H), 7.71 (dd, J = 8.8, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.45—7.39 (m, 2H), 6.09 (s, 2H), 2.77 (s, 3H), 2.63—2.60 (m, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.79 (d, 1JC-F = 244.9 Hz), 149.6, 143.7, 142.7, 142.44, 142.38, 141.8, 136.6, 134.1, 132.0 (d, 3JC-F = 8.5 Hz), 130.6, 130.60, 130.2 (d, 4JC-F = 3.1 Hz), 130.0, 128.4, 127.3, 126.8, 126.6, 122.7, 119.1, 118.8, 116.3 (d, 2JC-F = 21.8 Hz), 115.4, 112.5, 62.8, 19.9, 9.9 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C31H23ON3F [M]+ 472.1820, found 472.1818. HPLC purity: 98.6%.

4.2.2.11 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(4-(trifluoromethyl) benzyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide (a13)

Yield 85%. Yellow powder, m.p. 273–274 ℃. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.55 (s, 1H), 10.70 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 10.16 (s, 1H), 9.48 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.23 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.43 (dd, J = 8.4, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.37 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.95—7.88 (m, 4H), 7.72 (dd, J = 8.4, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (s, 2H), 2.79 (s, 3H), 2.65 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 149.6, 144.1, 143.3, 142.6, 142.5, 142.2, 138.6, 136.7, 134.2, 130.6 (q, 2JC-F = 35.9 Hz), 129.7, 130.0, 129.9, 128.6, 127.4, 126.9, 126.7 (q, 3JC-F = 9.15 Hz), 126.2 (q, 4JC-F = 3.9 Hz), 124.0 (q, 1JC-F = 270.8 Hz), 122.7, 119.2, 118.8, 116.5, 115.4, 112.6, 62.9, 19.9, 9.8 ppm; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C32H23N3OF3 [M]+ 522.1788, found 522.1788. HPLC purity: 97.0%.

4.2.2.12 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(4-formylbenzyl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a14)

Yield 74%. Yellow powder, m.p. 243–244 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3424, 3076, 2926, 2851, 1696, 1624, 1455, 1211, 1170, 814, 778, 702, 682, 594. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.52 (s, 1H), 10.68 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 10.15 (s, 1H), 10.08 (s, 1H), 9.47 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.24 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.43 (dd, J = 8.4, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.09—8.03 (m, 3H), 7.88 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.71 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.23 (s, 2H), 2.78 (s, 3H), 2.68—2.59 (m, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 192.9, 149.6, 144.1, 143.3, 142.5, 142.4, 142.2, 140.2, 136.7, 136.6, 134.2, 130.9, 130.6, 130.3, 130.0, 129.6, 128.6, 127.3, 126.9, 126.7, 126.6, 122.7, 119.6, 118.8, 116.5, 115.4, 112.6, 63.2, 19.9, 9.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C32H24N3O2 [M]+ 482.1863, found 482.1866.

4.2.2.13 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(4-methylbenzyl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a15)

Yield 60%. Yellow powder, m.p. 250–251 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3421, 3011, 2921, 1628, 1589, 1443, 1303, 1143, 1068, 816, 774, 678, 609, 595. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.59 (s, 1H), 10.70 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 10.07 (s, 1H), 9.46 (d, J = 8.4, 1H), 9.19 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.43—8.37 (m, 2H), 8.21 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (dd, J = 8.4, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.61—7.57 (m, 3H), 7.36 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 6.04 (s, 2H), 2.80 (s, 3H), 2.66 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H), 2.35 (s, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 149.6, 143.8, 142.8, 142.7, 142.5, 142.0, 139.2, 136.7, 134.2, 131.0, 130.7, 130.7, 130.0, 129.9, 129.3, 129.2, 128.5, 128.4, 127.4, 127.0, 126. 7, 126.6, 122.8, 119.2, 118.8, 116.5, 115.4, 112.6, 63.6, 20.8, 19.9, 9.7 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C32H26N3O [M]+ 468.2070, found 468.2071. HPLC purity: 95.6%.

4.2.2.14 1-(3, 4-dichlorobenzyl)-3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)pyridin-1-ium bromide (a16)

Yield 79%. Yellow powder, m.p. 297–298 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3427, 3007, 1626, 1587, 1491, 1468, 1397, 1146, 817, 773, 707, 687. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.62 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 10.11 (s, 1H), 9.32 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 9.22 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (dd, J = 8.0, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.72—7.67 (m, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 6.11 (s, 2H), 2.75 (s, 3H), 2.58 (s, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 149.5, 143.7, 143.0, 142.3, 142.3, 141.9, 136.5, 134.7, 134.0, 132.5, 131.9, 131.7, 131.5, 130.7, 130.5, 129.9, 129.9, 128.4, 127.2, 126.7, 126.7, 126.6, 122.6, 119.1, 118.7, 116.4, 115.3, 112.4, 62.1, 19.9, 9.9 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C31H22N3OCl2 [M]+ 522.1134, found 522.1139. HPLC purity: 98.7%.

4.2.2.15 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(3-fluoro-4-nitrobenzyl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a17)

Yield 61%. Yellow powder, m.p. 241–242 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3417, 3015, 2922, 1603, 1528, 1348, 1277, 1090, 841, 818, 746, 711, 677, 538. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.62 (s, 1H), 10.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 10.18 (s, 1H), 9.53 (dt, J = 7.8, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 9.21 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.46 (dd, J = 7.8, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.40 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.32 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (dd, J = 12.0, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.76—7.71 (m, 2H), 7.58 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.23 (s, 2H), 2.80 (s, 3H), 2.68 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 154.6 (d, 1JC-F = 260.9 Hz), 149.6, 144.2, 143.8, 142.7, 142.6, 142.5 (d, 3JC-F = 8.1 Hz), 137.2, 137.2, 136.8, 134.3, 131.9 (d, 2JC-F = 54.7 Hz), 130.0, 128.7, 127.4, 127.1, 127.0, 126.7 (d, 3JC-F = 9.0 Hz), 125.7 (d, 4JC-F = 3.9 Hz), 122.8, 119.2, 119.1, 118.9 (d, 2JC-F = 24.9 Hz), 116.5, 115.4, 112.6, 62.2, 19.9, 9.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C31H22N4O3F [M]+ 517.1670, found 517.1670. HPLC purity: 96.3%.

4.2.2.16 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(3-methyl-4-nitrobenzyl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a18)

Yield 47%. Yellow powder, m.p. 275–276 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3423, 3014, 2926, 1615, 1522, 1345, 1281, 1144, 967, 842, 820, 775, 679, 595. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.60 (s, 1H), 10.74 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 10.16 (s, 1H), 9.51 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.21 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.44 (dd, J = 7.8, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.39 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.76—7.71 (m, 2H), 7.57 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (s, 2H), 2.80 (s, 3H), 2.67 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H), 2.55 (s, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 149.6, 149.3, 144.1, 143.5, 142.6, 142.5, 142.3, 139.1, 136.6, 134.2, 133.5, 133.1, 131.0, 130.7, 130.0, 128.7, 127.8, 127.4, 127.0, 126.7, 126.6, 125.2, 122.8, 119.2, 118.8, 116.5, 115.4, 112.6, 62.7, 19.9, 19.4, 9.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C32H25N4O3 [M]+ 513.1921, found 513.1917. HPLC purity: 96.9%.

4.2.2.17 1-(2-bromo-4-nitrobenzyl)-3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a19)

Yield 40%. Yellow powder, m.p. 266–267 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3423, 3037, 1623, 1587, 1523, 1346, 1146, 1024, 840, 816, 795, 678. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.58 (s, 1H), 10.69 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 10.11 (s, 1H), 9.58 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.19 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.65 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (dd, J = 8.4, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.38 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.34 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (dd, J = 8.4, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.32 (s, 2H). 2.79 (s, 3H), 2.66 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 149.7, 148.4, 144.5, 143.9, 142.6, 142.5, 142.4, 140.5, 136.7, 134.2, 131.2, 131.0, 130.7, 130.0, 128.7, 127.9, 127.4, 127.0, 126.7, 126.5, 123.4, 123.4, 122.8, 119.2, 118.8, 116.5, 115.4, 112.6, 63.3, 19.9, 9.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C31H22N4O3Br [M]+577.0870, found 577.0876. HPLC purity: 96.9%.

4.2.2.18 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(naphthalen-1-ylmethyl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a20)

Yield 87%. Yellow powder, m.p. 266–267 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3428, 3192, 3064, 3008, 2931, 2861, 1868, 1626, 1491, 1452, 1398, 1173, 814, 796, 774, 677. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.17 (s, 1H), 10.33 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.85 (s, 1H), 9.23 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 9.19 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.35—8.25 (m, 2H), 8.17—8.10 (m, 2H), 8.06 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (s, 1H), 7.71—7.66 (m, 3H), 7.64—7.54 (m, 2H), 7.42 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.55 (s, 2H), 2.66 (s, 3H), 2.44 (s, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 149.4, 143.7, 142.3, 142.2, 142.0, 141.6, 136.44, 134.0, 133.7, 130.6, 130.5, 130.5, 130.4, 129.8, 129.2, 129.2, 129.0, 128.4, 127.7, 127.2, 126.8, 126.7, 126.5, 126.4, 125.8, 123.1, 122.5, 118.9, 118.7, 116.3, 115.3, 112.3, 61.4, 19.9, 9.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C35H26N3O [M]+ 504.2070, found 504.2074. HPLC purity: 98.0%.

4.2.2.19 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(naphthalen-2-ylmethyl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a21)

Yield 65%. Yellow powder, m.p. 288–289 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3420, 3041, 3004, 2918, 1805, 1589, 1393, 1370, 1282, 1160, 851, 816, 773, 678. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.57 (s, 1H), 10.65 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 10.13 (s, 1H), 9.48 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.27 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.45—8.40 (m, 1H), 8.37 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (s, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.12—8.06 (m, 2H), 8.04—8.00 (m, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.64—7.58 (m, 3H), 7.55 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.27 (s, 2H), 2.78 (s, 3H), 2.65 (s, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 149.6, 144.0, 143.0, 142.6, 142.5, 142.0, 136.7, 134.2, 133.1, 132.8, 131.4, 130.8, 130.6, 129.9, 129.2, 128.9, 128.5, 128.2, 127.8, 127.3, 127.2, 127.0, 126.9, 126.6, 126.5, 126.1, 122.8, 119.1, 118.8, 116.5, 115.4, 112.6, 63.9, 19.9, 9.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C35H26N3O [M]+ 504.2070, found 504.2069. HPLC purity: 96.4%.

4.2.2.20 3-(1, 6-dimethyl-12H-furo[2′, 3′:1, 2]phenanthro[3, 4-d]imidazol-11-yl)-1-(2-methylallyl) pyridin-1-ium bromide (a22)

Yield 73%. Yellow powder, m.p. 290–291 ℃. IR νmax (cm−1): 3421, 2922, 1625, 1490, 1283, 1161, 1104, 1068, 815, 773, 680, 592. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.48 (s, 1H), 10.68 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 9.96 (s, 1H), 9.47 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 9.09 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.41 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.34 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (s, 1H), 7.71 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.47 (s, 2H), 5.26 (s, 1H), 5.00 (s, 1H), 2.77 (s, 3H), 2.63 (s, 3H), 1.86 (s, 3H) ppm (one resonance was not observed due to active N–H of imidazole); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 149.6, 144.0, 142.9, 142.5, 142.4, 142.2, 139.6, 136.7, 134.2, 130.7, 130.6, 130.0, 128.4, 127.3, 126. 9, 126.7, 126.6, 122.7, 119.2, 118.8, 116.6, 116.4, 115.4, 112.6, 65.8, 19.9, 19.7, 9.9 ppm. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z Calcd for C28H24N3O [M]+ 418.1914, found 418.1917.

4.3 Biological

4.3.1 Materials and cell culture

The human cancer cell lines, including breast cancer (MDA-MB-231), hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), and prostate cancer (22RV1) were obtained from Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA). All the cells were incubated at 37 ℃, 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.

4.3.2 Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxic activities were evaluated by the MTS assay. All the compounds tested were absolutely dissolved to 10 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in stock. Cells (5 × 103 cells/well) were plated into 96-well plates and cultured for 12 h before treatment and continuously exposed to 0.032, 0.16, 0.8, 4 and 20 µM test compounds for 48 h. Then MTS reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added to each well, and cells were incubated at 37 ℃ for an additional 1–4 h and the optical density (OD) was measured at 492 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The IC50 values were calculated from dose–response curves.

4.3.3 Cell cycle analysis

For cell cycle analysis, cells were harvested and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then fixed overnight at 4 ℃ in 70% ethanol. After fixation, cells were washed again and incubated with propidium iodide (PI, 50 µg/mL) in the presence of RNase A (50 µg/mL) at room temperature for 30 min. Cell cycle distribution was analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (version 10.9.0).

4.3.4 Apoptosis analysis

Cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry using an Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded into 6-well plates at 3 × 105 cells/well, and treated with indicated concentrations of test compounds for 48 h. Cells were harvested, washed twice with cold PBS, and resuspended in binding buffer containing Annexin V-FITC and PI. Following incubation at room temperature in the dark for 15 min, fluorescence intensity was quantified using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

4.3.5 Scratch wound healing assay

Cell migration rates following 24 h incubation with a4 was quantitatively assessed using ImageJ software by measuring the wound closure area between the opposing edges.

4.3.6 PI3K activity assay

The inhibitory activity of a4 on PI3Kα was evaluated as previously based on the production of PIP3 with the PI3-Kinase Activity ELISA kit (K-1000 s, Echelon) [25].

4.3.7 Western blot analysis

The cells (Breast cancer, MDA-MB-231) were treated with compounds for indicated time and subjected to western blot analysis as previously [25]. The antibodies against AKT (#4691), phosphor-AKT (Ser473) (#9271), S6K (#2708), phosphor-S6K (Thr389) (#9234), S6 (#9202), phospho-S6 (Ser240/244) (#88441) and PD-L1 (#13684) were all from the Cell signaling technology, and the antibody for GAPDH (MAB374) was provided by Sigma.

4.3.8 Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.5 software. Pairwise comparisons among groups were analyzed using Tukey's test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Notes

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32260159, 82360725), the Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202301AS070022), the Major Science and Technology Special Projects of Yunnan Province (202402AA310025), the Yunnan Young & Elite Talents Project (YNWR-QNBJ-2020-084), Yunnan University Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (S202310673202).

Author contributions

HZ and YW contributed equally to this work. YF conceived and designed the experiments chemistry experiments. LK and YL conceived and designed the pharmacological experiments; HZ, YW, ZL, LL, JX, XY and ZZ performed the experiments; HZ, YW, ZL and JX analyzed the data; and HZ, YF and LK wrote the article.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China, 32260159, Yan Li, 82360725, Lingmei Kong, Applied Basic Research Foundation of Yunnan Province, 202301AS070022, Yan Li, Major Science and Technology Projects in Yunnan Province, 202402AA310025, Yan Li, Yunan Ten Thousand Talents Plan Young and Elite Talents Project, YNWR-QNBJ-2020-084, Lingmei Kong

Data availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

-

1.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74(3): 229-63. PubMed Google Scholar

-

2.Bergholz JS, Wang Q, Kabraji S, Zhao JJ. Integrating immunotherapy and targeted therapy in cancer treatment: mechanistic insights and clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26(21): 5557-66. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

3.Boshuizen J, Peeper DS. Rational cancer treatment combinations: an urgent clinical need. Mol Cell 2020;78(6): 1002-18. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

4.Zhong L, Li Y, Xiong L, Wang W, Wu M, Yuan T, et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. STTT 2021;6(1): 201. PubMed Google Scholar

-

5.Luo Z, Yin F, Wang X, Kong L. Progress in approved drugs from natural product resources. Chin J Nat Med 2024;22(3): 195-211. PubMed Google Scholar

-

6.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J Nat Prod 2020;83(3): 770-803. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

7.Tian XH, Wu JH. Tanshinone derivatives: a patent review (January 2006 - September 2012). Expert Opin Ther Pat 2013;23(1): 19-29. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

8.Dong Y, Morris-Natschke SL, Lee KH. Biosynthesis, total syntheses, and antitumor activity of tanshinones and their analogs as potential therapeutic agents. Nat Prod Rep 2011;28(3): 529-42. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

9.Gao H, Liu X, Sun W, Kang N, Liu Y, Yang S, et al. Total tanshinones exhibits anti-inflammatory effects through blocking TLR4 dimerization via the MyD88 pathway. Cell Death Dis 2017;8(8): e3004. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

10.Shi M, Luo X, Ju G, Li L, Huang S, Zhang T, et al. Enhanced diterpene tanshinone accumulation and bioactivity of transgenic Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots by pathway engineering. J Agric Food Chem 2016;64(12): 2523-30. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

11.Zhou W, Huang Q, Wu X, Zhou Z, Ding M, Shi M, et al. Comprehensive transcriptome profiling of Salvia miltiorrhiza for discovery of genes associated with the biosynthesis of tanshinones and phenolic acids. Sci Rep 2017;7(1): 10554. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

12.Wu Q, Zheng K, Huang X, Li L, Mei W. Tanshinone-IIA-based analogues of imidazole alkaloid act as potent inhibitors to block breast cancer invasion and metastasis in vivo. J Med Chem 2018;61(23): 10488-501. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

13.Xue Z, Li CY, Zhu GH, Song LL, Zhao YW, Ma YH, et al. Discovery of tetrahydro tanshinone Ⅰ as a naturally occurring covalent pan-inhibitor against gut microbial bile salt hydrolases. J Agric Food Chem 2024;72(42): 23233-45. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

14.Zhu W, Bao X, Yang Y, Xing M, Xiong S, Chen S, et al. Peripheral evolution of tanshinone ⅠIA and cryptotanshinone for discovery of a potent and specific NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor. J Med Chem 2025;68(3): 3460-79. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

15.Ding C, Tian Q, Li J, Jiao M, Song S, Wang Y, et al. Structural modification of natural product Tanshinone Ⅰ leading to discovery of novel nitrogen-enriched derivatives with enhanced anticancer profile and improved drug-like properties. J Med Chem 2018;61(3): 760-76. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

16.Wang W, Li J, Ding Z, Li Y, Wang J, Chen S, et al. Tanshinone Ⅰ inhibits the growth and metastasis of osteosarcoma via suppressing JAK/STAT3 signalling pathway. J Cell Mol Med 2019;23(9): 6454-65. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

17.Zhou J, Jiang YY, Chen H, Wu YC, Zhang L. Tanshinone Ⅰ attenuates the malignant biological properties of ovarian cancer by inducing apoptosis and autophagy via the inactivation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Cell Prolif 2020;53(2): e12739. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

18.Huang X, Jin L, Deng H, Wu D, Shen QK, Quan ZS, et al. Research and development of natural product tanshinone Ⅰ: pharmacology, total synthesis, and structure modifications. Front Pharmacol 2022;13: 920411. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

19.Liu Y, Li X, Li Y, Wang L, Xue M. Simultaneous determination of danshensu, rosmarinic acid, cryptotanshinone, tanshinone ⅠIA, tanshinone Ⅰ and dihydrotanshinone Ⅰ by liquid chromatographic-mass spectrometry and the application to pharmacokinetics in rats. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2010;53(3): 698-704. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

20.Park EJ, Ji HY, Kim NJ, Song WY, Kim YH, Kim YC, et al. Simultaneous determination of tanshinone Ⅰ, dihydrotanshinone Ⅰ, tanshinone ⅠIA and cryptotanshinone in rat plasma by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: application to a pharmacokinetic study of a standardized fraction of Salvia miltiorrhiza, PF2401-SF. Biomed Chromatogr 2008;22(5): 548-55. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

21.Yu H, Subedi RK, Nepal PR, Kim YG, Choi HK. Enhancement of solubility and dissolution rate of cryptotanshinone, tanshinone Ⅰ and tanshinone ⅠIA extracted from Salvia miltiorrhiza. Arch Pharm Res 2012;35(8): 1457-64. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

22.Deng G, Zhou B, Wang J, Chen Z, Gong L, Gong Y, et al. Synthesis and antitumor activity of novel steroidal imidazolium salt derivatives. Eur J Med Chem 2019;168: 232-52. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

23.Liu Z, Zhang Y, Dong J, Fang Y, Jiang Y, Yang X, et al. Synthesis and antitumor activity of novel hybrid compounds between 1,4-benzodioxane and imidazolium salts. Arch Pharm 2022;355(10): e2200109. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

24.Yin M, Fang Y, Sun X, Xue M, Zhang C, Zhu Z, et al. Synthesis and anticancer activity of podophyllotoxin derivatives with nitrogen-containing heterocycles. Front Chem 2023;11: 1191498. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

25.Zhou H, Yu C, Kong L, Xu X, Yan J, Li Y, et al. B591, a novel specific pan-PI3K inhibitor, preferentially targets cancer stem cells. Oncogene 2019;38(18): 3371-86. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

26.Dwivedi AR, Jaiswal S, Kukkar D, Kumar R, Singh TG, Singh MP, et al. A decade of pyridine-containing heterocycles in US FDA approved drugs: a medicinal chemistry-based analysis. RSC Med Chem 2024;16(1): 12-36. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

27.Vitaku E, Smith DT, Njardarson JT. Analysis of the structural diversity, substitution patterns, and frequency of nitrogen heterocycles among U.S. FDA approved pharmaceuticals. J Med Chem 2014;57(24): 10257-74. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

28.Albratty M, Alhazmi HA. Novel pyridine and pyrimidine derivatives as promising anticancer agents: a review. Arab J Chem 2022;15(6): 103846. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

29.Xu T, Xue Z, Li X, Zhang M, Yang R, Qin S, et al. Development of membrane-targeting osthole derivatives containing pyridinium quaternary ammonium moieties with potent anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus properties. J Med Chem 2025;68(7): 7459-75. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

30.Mishra T, Gupta S, Rai P, Khandelwal N, Chourasiya M, Kushwaha V, et al. Anti-adipogenic action of a novel oxazole derivative through activation of AMPK pathway. Eur J Med Chem 2023;262: 115895. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

31.Varma MV, Kaushal AM, Garg S. Rapid and selective UV spectrophotometric and RP-HPLC methods for dissolution studies of oxybutynin immediate-release and controlled-release formulations. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2004;36(3): 669-74. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

32.Fruman DA, Chiu H, Hopkins BD, Bagrodia S, Cantley LC, Abraham RT. The PI3K Pathway in human disease. Cell 2017;170(4): 605-35. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

33.Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet 2006;7(8): 606-19. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

34.Quan Z, Yang Y, Zheng H, Zhan Y, Luo J, Ning Y, et al. Clinical implications of the interaction between PD-1/PD-L1 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in progression and treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer 2022;13(13): 3434-43. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

35.Jia WQ, Luo SY, Guo H, Kong D. Development of PI3Kα inhibitors for tumor therapy. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2023;41(17): 8587-604. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© The Author(s) 2025

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.