Nitrogen-containing secondary metabolites from Meliaceae Family and their biological activity: a review

Abstract

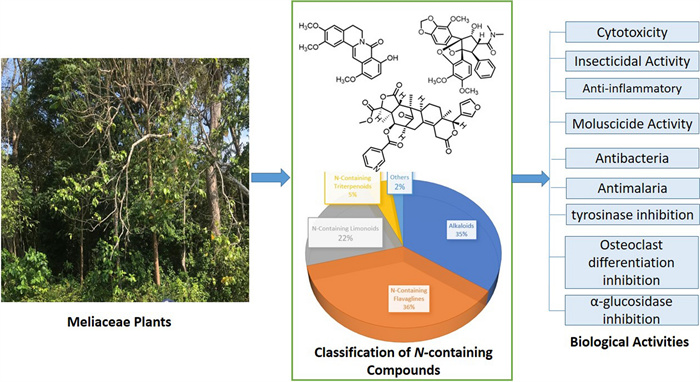

The Meliaceae family, widely distributed in tropical and subtropical regions, has been traditionally used for medicinal purposes, particularly in treating infections and inflammatory diseases. The objective of this study is to provide a comprehensive account of the nitrogen-containing secondary metabolites and their biological activities that have been isolated from the Meliaceae family between the years 1979 and 2024. Studies on nitrogen-containing compounds of the Meliaceae family were collected and analyzed using data from SciFinder, PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus and World Flora Online. Over the course of more than four decades, numerous studies have been conducted on a variety of plant parts, including twigs, stems, barks, roots, fruits, seeds, and leaves. These studies have identified approximately 326 compounds belonging to diverse chemical groups, such as alkaloids, limonoids, triterpenoids, and nitrogen-containing flavaglines being the largest group of natural products, comprising 118 compounds (36.2%). Several compounds have been evaluated for insecticidal, anti-inflammatory, molluscicide, antibacterial, antimalarial, tyrosinase inhibition, osteoclast differentiation inhibition, and α-glucosidase inhibition activity. The systematic classification and analysis of these compounds provide insights into their biosynthesis and bioactivities, paving the way for future drug development.Graphical Abstract

Keywords

Nitrogen-containing Secondary metabolites Meliaceae Biological activity1 Introduction

Natural compounds containing nitrogen, such as alkaloids, peptides, amino acids, nucleic acids, and sphin-gophospholipids, have been extracted from various organisms including plants, animals, fungi, insects, and marine life [1]. These compounds show a wide range of biological effects, including antitumor, antiviral, antibacterial, and immunosuppressive activity. Nitrogen-containing natural products have proved successful as drug leads and chemical probes for research. Some examples include vinblastine, vincristine, morphine, and quinine [2, 3].

The Meliaceae family, widely known for its diverse species like Azadirachta indica A. Juss. (neem) and Aglaia odorata Lour., has been used traditionally across cultures for its medicinal and insecticidal properties. Ancient herbal practices in regions like India, China, and Southeast Asia included remedies derived from Meliaceae for ailments such as infections, fevers, and inflammations. Over centuries, the use of these plants spread as explorers and trade routes carried knowledge and plant samples to new parts of the world. This family, commonly known as the mahogany family, consists of woody plants distributed across tropical and subtropical regions worldwide [4, 5]. Several decades of phytochemical research on the Meliaceae family has led to the identification of a range of secondary metabolites including triterpenoids [6-10], diterpenoids [11-13], sesquiterpenoids [14-16], steroids [17-19], limonoids [20-22], flavonoids [23, 24], lignans [25], flavaglines [26, 27], and alkaloids [28, 29].

The first phytochemical investigation of nitrogen-containing compounds from Meliaceae plant was conducted in 1979. This study led to the isolation of a chromone alkaloid, rohitukine from the leaves of Dysoxylum acutangulum Miq. and two bisamides, roxburghilin and odorinol, from the leaves of Aglaia odorata Lour. [30-32]. By the mid-twentieth century, advances in isolation techniques and bioassays allowed researchers to test these compounds' effects against various pathogens and cancer cells. Early findings inspired more in-depth studies of Meliaceae compounds' structures, mechanisms of action, and potential as pharmaceutical agents. The discovery of highly potent compounds, such as rohitukine and rocaglamide, marked a breakthrough, and their activities inspired further synthetic modifications to enhance efficacy. Flavopiridol, a semi-synthetic derivative of rohitukine, emerged as a promising anticancer agent undergoing clinical trials, exemplifying how traditional knowledge was transformed through modern science into potential therapies. Research conducted over four subsequent decades identified 5 classes of nitrogen-containing compounds. The current research continues this trajectory, assessing cytotoxic activities of various Meliaceae-derived alkaloids and flavaglines against a broad spectrum of cancer cell lines. By building on historical foundations and evolving research methodologies, these studies are crucial in uncovering the pharmacological potential of Meliaceae compounds. This historical perspective highlights the continuity of scientific inquiry and innovation rooted in ancient practices, showcasing the value of Meliaceae plants as a source of anticancer agents. Here we present the first comprehensive review of nitrogen-containing compounds isolated from plants in the Meliaceae family covering a total of 326 compounds. More importantly, these nitrogen-containing compounds, which have diverse structural characteristics, also demonstrate a wide range of pharmacological activities. These include cytotoxic [33-35], insecticidal [36-38], anti-inflammatory [26, 39, 40], molluscicide [41-43], antibacterial [44], and antimalarial agents [45]. Some nitrogen-containing compounds have formed the basis for the development of new drugs, and further research is ongoing to optimize their use in modern medicine.

2 Material and methods

A systematic literature search was conducted using SciFinder, PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, and World Flora Online. Articles published between 1979 and 2024 were selected based on their relevance to nitrogen-containing compounds in Meliaceae. Inclusion criteria encompassed studies that reported structural elucidation, biological activity, and biosynthetic pathways of these metabolites. Duplicate reports and studies lacking detailed characterization were excluded.

3 Plant distribution and habitats

Plants of the Meliaceae family are woody plants belonging to the mahogany group, classified under the order Sapindales and the class Angiospermae. The Meliaceae family is widely distributed across tropical regions in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. In addition, it has a notable presence outside the tropics in areas such as South Africa, New Zealand, central China, northern India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Australia [46].

The Meliaceae family consists of approximately 59 genera, with Aglaia being the largest among them. This family is primarily found in tropical regions but is also present in some temperate areas. Most species inhabit lowland tropical rainforests on dry land, though the family is also found on rocky shores and in mangrove swamps (species of Xylocarpus), freshwater swamp forest in Borneo (Sandoricum borneense Miq. and Chisocheton amabilis Miq.), drier forests, woodlands, and open savannas. They are poorly represented at higher altitudes, although some species of Dysoxylum and Toona sinensis (A.Juss.) M.Roem. are occasionally prominent in lower montane forest in Asia and Ruagea spp. in America. Walsura monophylla Elmer ex Merr. is limited to ultramafic soil in the Philippines. Meliaceae species are commonly found in secondary vegetation (Toona spp.), with some species becoming invasive weeds [46, 47].

4 Phytochemistry

4.1 Overview of nitrogen-containing compounds isolated from Meliaceae Family

Based on scientific articles published from 1979 to 2024, a total of 326 nitrogen-containing compounds were obtained from the leaves, stems, stem barks, bark, roots, twigs, fruits, and seeds of plants in the Meliaceae family. The parts of the plant most frequently reported as source materials for isolation were the leaves followed by stem bark, roots, twigs, seeds, and fruit, with flowers being the least reported. Grouping the compounds according to structural class, nitrogen-containing flavaglines are the largest natural products, with a total of 118 compounds (36.2%), followed by alkaloids (34.6%), limonoids (22.1%), triterpenoids (4.6%), and others (2.5%), see Fig. 1.

The distribution by groups of nitrogen-containing compounds from the Meliaceae family and their majors compounds

4.2 Alkaloids

Alkaloids typically contain one or more nitrogen atoms, usually in the form of primary, secondary, or tertiary amines, although quaternary amines are also present. For example, some alkaloids are essentially neutral, such as those with nitrogen in an amide function [48].

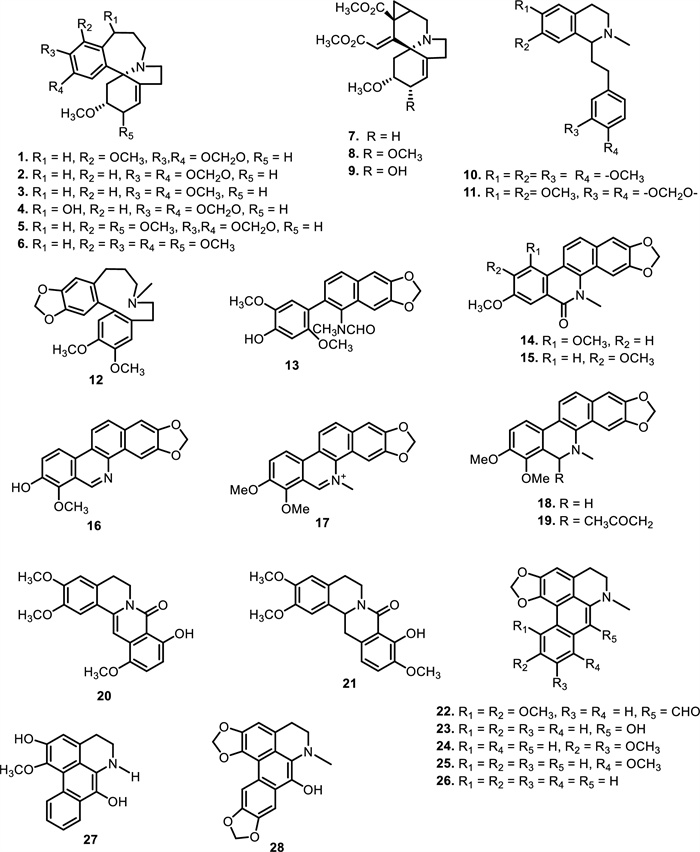

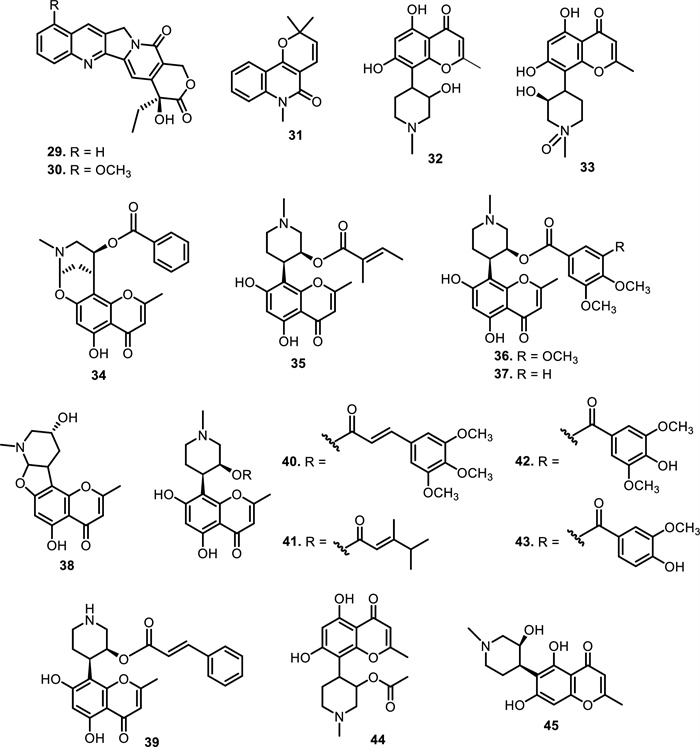

Different classes of alkaloids have been reported from the plants belonging to Meliaceae family. These include isoquinoline, quinoline, chromone, amide, carbazole, pyrrole, piperidine, indole, pyrazine, and β-carboline alkaloids. A summary of the number and types of alkaloids obtained from Meliaceae family is presented in Table 1, while Figs. 2 and 3 show the structures of the compounds.

Alkaloids from Meliaceae family

The chemical structures of compounds 1–28

The chemical structures of compounds 29–45

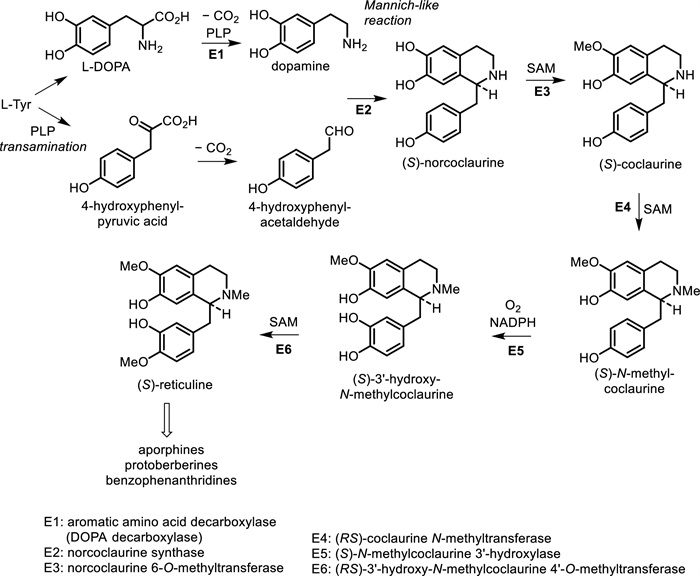

4.2.1 Isoquinoline alkaloids

Isoquinoline alkaloids are derived from tyrosine and phenylalanine. These compounds are synthesized from the precursor 3, 4-dihydroxyphenylethylamine (dopamine) via a reaction with an aldehyde or ketone. The product from the Mannich-like reaction is thus the trihydroxy alkaloid norcoclaurine, formed stereospecifically as the (S)-enantiomer. The tetrahydroxy substitution pattern is built up by further hydroxylation in the benzyl ring, though O-methylation (giving (S)-coclaurine) and N-methylation steps precede this. Eventually, (S)-reticuline, a pivotal intermediate to other alkaloids, is attained by N-methylation [48]. The biosynthetic pathways for several types of isoquinoline alkaloids from the Meliaceae family are shown in Fig. 4. In line with these biosynthetic pathways, a total of 28 isoquinoline alkaloids had been identified from different classes including homoerythrina, phenylethylisoquinoline, dibenz[d, f]azecine, benzophenanthridine, oxoprotoberberine, and aporphine alkaloids.

The biosynthetic pathways to several types of isoquinoline alkaloids from Meliaceae family

Among these classes, homoerythrina alkaloids represent a growing class of natural products, predominantly isolated from the Dysoxylum genus. These compounds are characterized by a tetracyclic C17 skeleton, which constitutes a structural expansion of the erythrinan-type alkaloid framework, particularly at the nitrogen-containing ring. The homoerythrina scaffold retains the fused aromatic and nitrogenous ring system common to Erythrina alkaloids but incorporates an additional carbon atom in the core structure, resulting in subtle yet significant differences in molecular flexibility and physicochemical properties. Specifically, the nine alkaloids investigated in this study, namely dyshomerythrine (1), 3-epischelhammericine (2), 2, 7-dihydrohomoerysotrine (3), 3-epi-12-hydroxyschelhammericine (4), 3-epi-18-methoxyschelhammericine (5), 2α-methoxycomosivine (6), lenticellarine (7), 2α-methoxylenticellarine (8), and 2α-hydroxylenticellarine (9), belong to this class and can be categorized into two structural subtypes. Compounds 1–6 share a polycyclic backbone with a fused aromatic ring, a nitrogenous ring, and an oxygenated six-membered ring. Their structural variation arises from different substituents (methoxy, hydroxyl, and methylenedioxy) at positions C-2, C-12, C-16, C-17, and C-18. For instance, compound 1 features a methoxy group at C-18 and a methylenedioxy bridge at C-16 and C-17, whereas compound 2 lacks methoxy groups but retains the bridge. In compound 3, the bridge is replaced by discrete methoxy groups, while compound 4 carries a hydroxyl at C-12. Methoxylation increases in compounds 5 and 6, with compound 6 bearing four methoxy groups on the aromatic ring [42, 49]. In contrast, compounds 7–9 form a distinct subgroup, defined by a bicyclic lactam system, two methyl ester groups, a methoxy substituent at C-3, and variation at the 2α-position. Compound 7 bears a hydrogen, compound 8 a methoxy, and compound 9 a hydroxyl group at this position, altering polarity and hydrogen-bonding capacity. All nine compounds were isolated from Dysoxylum lenticellare Gillespie. Compounds 1–4 and 7 were obtained from the leaves, while 1–3, 5–6, and 7 were also found in the stem. Notably, compounds 8 and 9 were exclusive to the stem, indicating tissue-specific distribution [41, 50, 51].

Beyond the homoerythrina class, the phenethylisoquinoline class includes homolaudanosine (10) and dysoxyline (11), which are biosynthetically derived from the condensation of dopamine and phenylacetaldehyde. These compounds are characterized by a linear framework composed of a 1-benzylisoquinoline core, with a phenethyl side chain attached at the C-1 position of the isoquinoline. This scaffold permits a high degree of substitution, especially with methoxy and methylenedioxy groups, which significantly influence their physicochemical properties and molecular conformation [42, 50]. In addition, dibenz[d, f]azecine alkaloids, such as dysazecine (12), introduce unique rigid frameworks, which may contribute to their distinctive pharmacological profiles [42, 49]. Furthermore, Vardamides et. al. reported the presence of four benzophenanthridine-type alkaloids including turraeanthins A-B (13–14), oxynitidine (15), and decarine (16), which were obtained from the stem bark of Turraeanthus africanus (Welw. ex C.DC.) Pellegr [52]. Compound 13 bears a formyl group (–CHO) attached to the N-methylated nitrogen at position 7. It also features hydroxyl and methoxy substituents at C-10 and C-11, respectively, which enhance hydrogen bonding and electron density. Additionally, the dioxolane ring spanning positions 2 and 3 contributes to conformational rigidity and increased lipophilicity. Compounds 14 and 15 are oxo-derivatives with two methoxy and the methylenedioxy at C-2 and C-3. They are structural isomers differing only in the position of the methoxy groups (C-11 and C-12). These changes may influence resonance stabilization and electron distribution within the aromatic system. Compound 16 is a fully aromatic benzophenanthridine with a hydroxyl at C-10 and a methoxy at C-9. It lacks N-substitution, rendering it more reactive toward electrophilic substitutions or oxidative transformations. Similarly, the root barks of Xylocarpus granatum J.Koenig contained three compounds including, chelerythrine (17), dihydrochelerythrine (18), and acetonyldihydrochelerythrine (19) [53]. Compound 17 represents the quaternary benzophenanthridinium form, where the nitrogen atom is methylated and carries a permanent positive charge. Compound 18 is the parent dihydrobenzophenanthridine with two methoxy groups at C-9 and C-10 and a free secondary nitrogen. Compound 19 is a substituted derivative of compound 18, bearing an acetonyl side chain at the aromatic ring. This side chain increases the molecule's steric bulk and enhances lipophilicity.

Moving on to the oxoprotoberberine class, amocurines A (20) and B (21) are newly characterized alkaloids belonging to the oxoprotoberberine class, featuring a distinctive tetracyclic isoquinoline-derived scaffold. Structurally, these compounds differ in their substitution patterns, particularly in the number and position of methoxy groups on the aromatic rings. Both compounds were isolated from Amoora cucullata Roxb. (syn. Aglaia cucullata (Roxb.) Pellegr.). Moreover, six aporphine alkaloids, namely amocurines C-D (22–23), dehydrodicentrine (24), stephanine (25), roemerine (26), and amocurine E (27), were also isolated from the same plant [28, 44, 45]. These compounds differ by their substitution patterns on the aromatic rings, which modulate physicochemical properties such as polarity, electronic distribution, and lipophilicity. Compound 26 is the simplest analog, lacking any ring substituents, rendering it more hydrophobic. [45] reported the presence of a novel aporphine alkaloid, namely amocurine F (28), from the leaves of Amoora cucullata Roxb., along with five known compounds 22–26. Uniquely, Amocurine F features two methylenedioxy bridges: one on ring A (positions 1 and 2) and another on ring D (positions 9 and 10), creating a more conformationally constrained and electron-rich aromatic system.

4.2.2 Quinoline and quinolone alkaloids

Quinoline and quinolone alkaloids represent a structurally and biologically significant subclass within the Meliaceae family, albeit with a limited number of identified representatives. To date, only two quinoline alkaloids, camptothecin (29) and 9-methoxy camptothecin (30), have been isolated from the ethanolic extract of the bark of Dysoxylum binectariferum Hook.f. ex Bedd. [54]. Camptothecin is a well-known cytotoxic agent that serves as the precursor for clinically approved chemotherapeutic drugs such as topotecan and irinotecan. The occurrence of camptothecin in Dysoxylum binectariferum underscores the chemotaxonomic significance of this species within Meliaceae. Interestingly, this alkaloid has been exclusively found in the stem bark of D. binectariferum, suggesting a highly localized biosynthetic pathway. The presence of a methoxy substituent at C-9 in compound 30 increases its lipophilicity and may alter the electronic distribution across the aromatic system, potentially influencing its chemical reactivity and solubility. In addition, a quinolone alkaloid, N-methylflindersine (31), has been identified in the root bark of Xylocarpus granatum J. Koenig, further expanding the alkaloidal diversity within Meliaceae [53].

4.2.3 Chromone alkaloids

Expanding on the alkaloidal diversity, chromone alkaloids have been reported exclusively from the genus Dysoxylum within the Meliaceae family. A total of 14 chromone alkaloids have been identified, and these compounds exhibit a broad spectrum of bioactivities, underscoring their pharmaceutical potential. The first chromone alkaloid reported from Meliaceae was rohitukine (32), which was isolated in 1979 from the leaves and stem of Amoora rohituka Wight & Arn (syn. Aphanamixis polystachya (Wall.) Parker) [32]. This compound has also been reported in the leaves of Dysoxylum acutangulum Miq [55]. and stem bark of Dysoxylum binectariferum (Roxb.) Hook.f. ex Bedd. [33, 56, 57]. According to subsequent phytochemical studies, rohitukine is a taxonomically significant metabolite predominantly found in a limited number of Meliaceae species, particularly within the genera Amoora and Dysoxylum. This specificity makes rohitukine a valuable chemical marker for the family. [58] reported the presence of compound 32 from the stem bark of Dysoxylum binectariferum (Roxb.) Hook. f. ex Bedd., along with its oxidized analogue, rohitukine N-oxide (33), which features an additional N → O group that increases polarity. Another study reported that the leaves of Dysoxylum acutangulum Miq. yielded four new chromone alkaloids, including chrotacumines A-B (34–35) [55] and chrotacumines E–F (38–39) [59]. Meanwhile, chrotacumines C-D (36–37), isolated from the bark of Dysoxylum acutangulum Miq., feature extended aromatic substitution with methoxy groups that modulate electronic distribution and lipophilicity [55]. [60] isolated four chromone alkaloids chrotacumines G-J (40–43) from the bark of Dysoxylum acutangulum Miq. Adding to this, [39] investigated the fruits of Dysoxylum binectariferum Hook f., which led to the isolation of one novel chromone alkaloid, chrotacumine K (44) with rohitukine (32) and chrotacumine E (38). Dysoline (45) was also isolated from the stem bark, along with rohitukine N-oxide (33) [33].

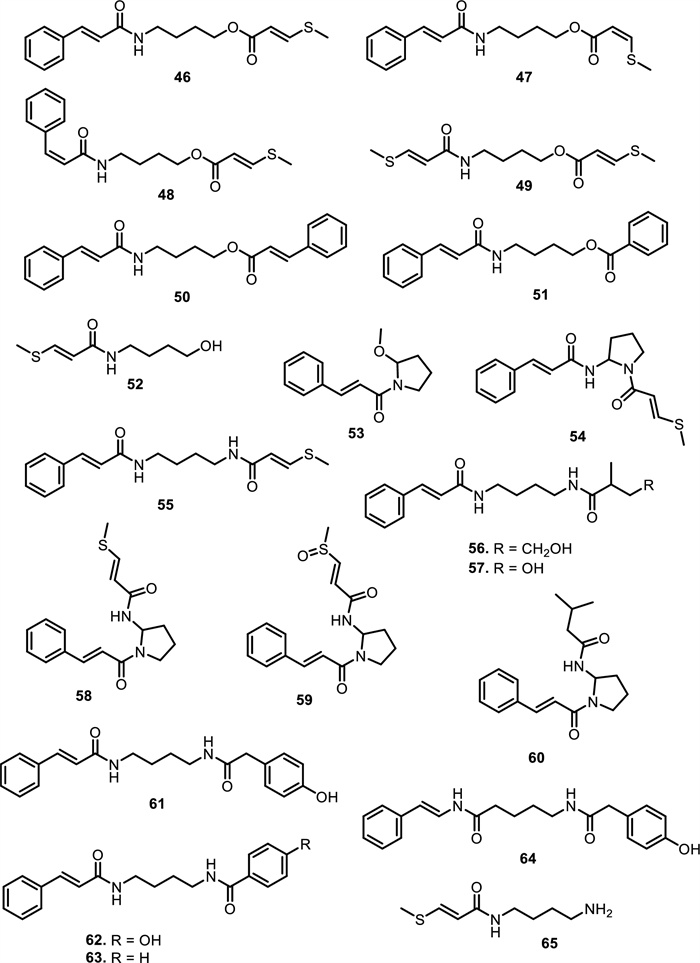

4.2.4 Amide alkaloids

Amide alkaloids constitute another major class within the Meliaceae family, with sulfur-containing and bisamide derivatives being particularly prominent. Aglaia tenuicaulis Hiern has yielded several sulfur-containing monoamide-esters, including tenucaulin A (46), isotenucaulin A (47), tenucaulin B (48), and aglatenin (49). Further exploration of A. tenuicaulis stem bark led to the discovery of two new monoamide-esters: tenaglin (50) and caulitenin (51), which are characterized by phenylacryloyl and aryl ester motifs, respectively, providing greater aromatic character and conjugation. Additionally, the leaf extract yielded one amide alcohol, aglatenol (52). The bisamide class is exemplified by compounds such as pyrrolotenin (54) and secopyrrolotenin (55), also isolated from the leaves of A. tenuicaulis. In a similar context, two structurally distinct bisamides, secoisoodorinol (56) and secoisopiriferinol (57), were identified in Aglaia spectabilis (Miq.) Jain & Bennet [61]. Other compounds found in Aglaia genus such as aglamide D (53), a new monoamide, along with three bisamides, aglamides A–C (58–60), were isolated from the leaves and twigs of Aglaia edulis (Roxb.) Wall. Compounds 58 and 59, obtained from the leaves, are sulfur-containing compounds, with 59 representing the first sulfonyl-bearing alkaloid reported from the genus Aglaia. Compound 60, isolated from the twigs, features an isobutyl group on the amide nitrogen, enhancing hydrophobicity and steric bulk. Structurally, 58 carries a methylthio group, while 59 has a more polar methylsulfonyl substituent on the cinnamoyl moiety [62]. All three compounds possess a conjugated phenyl double bond system, promoting planarity and potential π–π interactions with biological targets.

Expanding on the bisamide diversity, three related compounds such as perviridamide (61), 4-hydroxypyramidatine (62), and pyramidatine (63) are structurally related compounds characterized by their bisamide framework. Compound 61 only differs by one methylene group from the other two compounds. 62 is distinguished from 63 by the presence of a hydroxyl group at fourth position. Compounds 61–63 were isolated from the chloroform extract of the twigs of Aglaia perviridis Hiern [63]. Additionally, compound 62 and 63, along with N-(4-(2-(4-hydroxyphenyl) acetamido) butyl)-cinnamamide (64), were isolated from the leaves of Aglaia perviridis Hiern [64]. Compound 63 was extracted from the leaves of several other Aglaia species, such as Aglaia pyramidata Hance [65] and Aglaia foveolata Pannell [66], Aglaia gracilis A.C.Sm. [67], Aglaia andamanica Hiern [68] and Aglaia forbesii King [69].

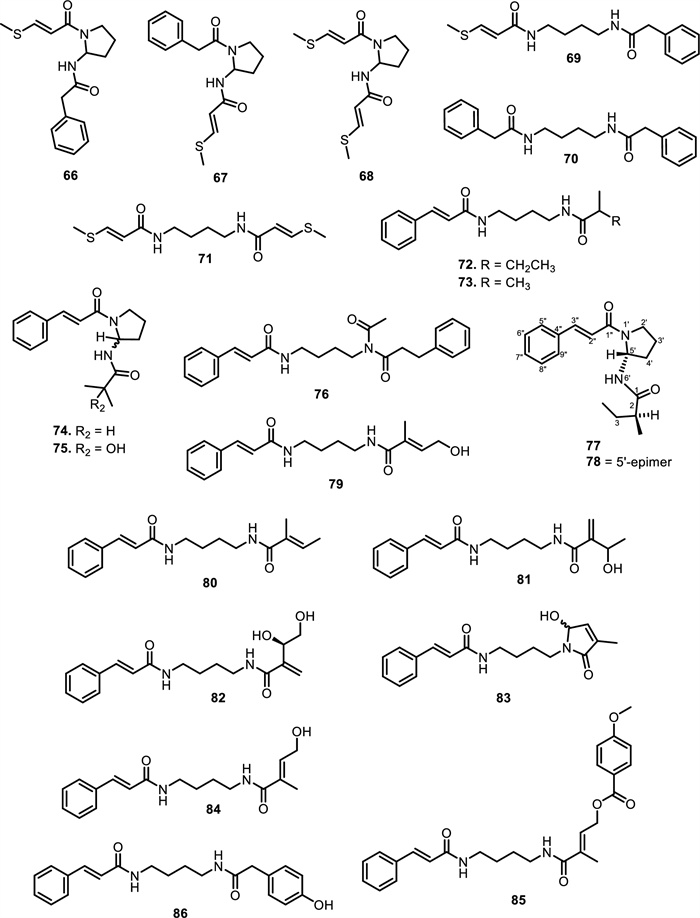

Another six new amides have been isolated from the leaves and stem barks of Aglaia leptantha Miq., namely hemileptaglin (65), agleptin (66), isoagleptin (67), leptanthin (68), leptagline (69), and aglanthine (70). Specifically, compound 69 was identical to aglaithioduline, while compound 70 was structurally related to aglaiduline. These two compounds, along with aglaidithioduline (71), were isolated from the leaves of Aglaia edulis (Roxb.) Wall. [70]. Closely related analogs such as secoodorine (72), secopiriferine (73), and piriferine (74) were extracted from the leaves of Aglaia gracilis A.C.Sm. [67]. Additionally, compound 74 was also found in Aglaia pyramidata Hance [65], Aglaia pirifera Hance (syn. Aglaia edulis (Roxb.) Wall.) [71], Aglaia elliptifolia Merr. [72], Aglaia testicularis C.Y.Wu (syn. Aglaia edulis (Roxb.) Wall.) [73], and Aglaia odorata Lour. [29]. Aglaia elaeagnoidea Benth. leaves contained two new bisamide derivatives, namely piriferinol (75) and edulimide (76) [74]. Odorine (77) was found in several other Aglaia species, such as Aglaia odorata Lour. [29, 40, 75], Aglaia roxburghiana Miq. [30], Aglaia pirifera Hance [71], Aglaia pyramidata Hance [65], Aglaia argentea Blume [76], Aglaia laxiflora Miq. [77], Aglaia elliptica Blume [78], Aglaia gracilis A.C.Sm. [67], and Aglaia oligophylla Miq. [79]. Compound 75 is a hydroxylated analog of 74, whereas 77 and 5'-epi-odorine (78) were epimers. The aglairubine (79) is a bisamide bearing a hydroxyl group at the terminus, which has been isolated from leaves of Aglaia spectabilis (Miq.) [61, 80] and Aglaia rubiginosa (Hiern) Pannel [81].

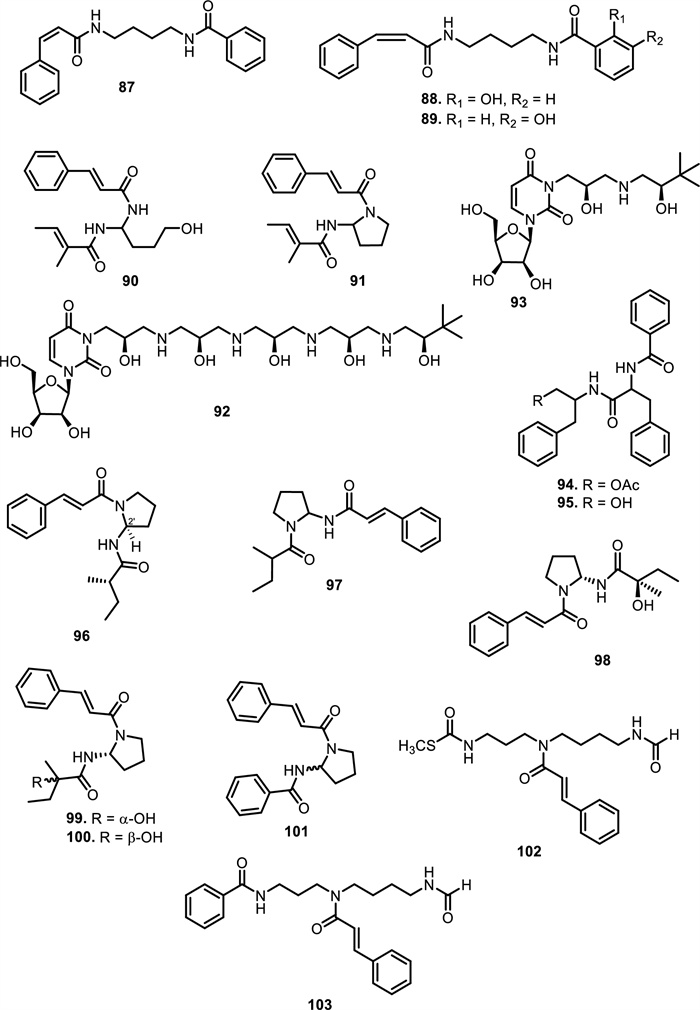

Furthermore, two putrescine bisamides, grandiamides B-C (80–81) were obtained from the leaves of Aglaia grandis Korth. [82], while grandiamide D (82), gigantamide A (83), and dasyclamide (84) were isolated from the leaves of Aglaia gigantea Pellegr. [83]. The leaves, twigs, and fruits of Aglaia perviridis Hiern also yielded compound 83 [27], while the leaves of Aglaia dasyclada F.C.How & T.C.Chen [84] and Amoora cucullata Roxb. yielded compound 84 [85, 86]. Additionally, one new bisamide derivative has been isolated and elucidated as cucullamide (85) [86]. The aglaianine (86) has been isolated from the leaves of Aglaia abbreviata C.Y.Wu, while aglaiamide A (87), aglaiamide O (88), and aglaiamide P (89) were obtained from the leaves of Aglaia perviridis Hiern [26]. Furthermore, two bisamides, namely elliptinol (90) and dehydroodorin (91) were derived from the leaves of Aglaia elliptifolia Merr. [72]. [87] also obtained 91 from the leaves of Aglaia formosana Hayata. [88] reported two novel bisamides, eximiamides A-B (92–93) from the leaves of Aglaia eximia Miq. Moreover, Amoora genus has been shown to produce bisamide compounds such as those isolated from Amoora ouangliensis (H.Lev.) C.Y.Wu barks, including aurantiamide acetate (94) and benzenepropanamide (95) [89]. Aglaia oligophylla Miq. leaves yielded 2'-epi-odorine (96) [79], while roxburghilin (97) and odorinol (98) were the first bisamides to be isolated from Meliaceae species [30, 75]. Compound 98 was also reported from Aglaia odorata Lour. leaves and twigs [29, 40, 90], Aglaia laxiflora Miq [77]. and Aglaia testicularis C.Y.Wu leaves [73]. A recent paper by [29] reported four bisamides, compound 98, agladorin A (99), (−) odorinal (100), and agladorin B (101) from the leaves and twigs of Aglaia odorata Lour.

The leaves of Chisocheton weinlandii Harms were found to contain two polyamide alkaloids, chisitines 1 and 2 (102–103). These two compounds were elucidated by mass spectrometry in combination with tandem-mass spectrometry (MS–MS) and then chemically isolated. The chemical structures of compounds 102 and 103 share a common polyamide backbone but differ in the nature of their side chains and functional groups. Chisitine 1 (102) features a side chain with a methylthio group attached to the amide, which introduces both steric and electronic effects that may influence the compound's solubility and reactivity. In contrast, chisitine 2 (103) has a similar polyamide core but lacks the methylthio group, instead incorporating a phenyl group attached to the amide nitrogen, which may alter its hydrophobicity and interaction with biological targets. Both compounds maintain an aromatic ring linked to the amide group, which likely contributes to their structural stability and potential bioactivity [91].

4.2.5 Carbazole alkaloids

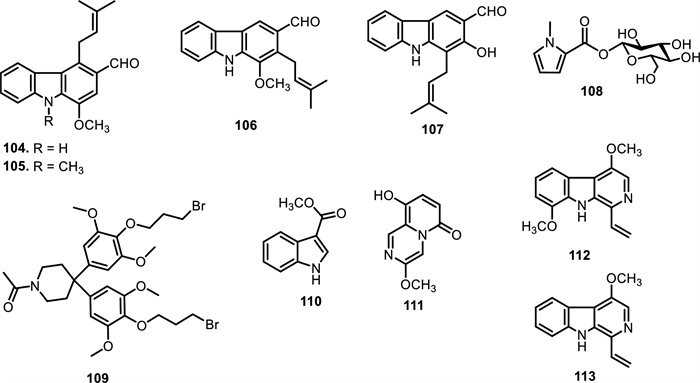

Carbazole alkaloids are a distinct class of naturally occurring compounds characterized by a fused tricyclic system consisting of two benzene rings joined on either side of a pyrrole ring. These alkaloids exhibit significant biological activities, including cytotoxic, antimicrobial, and antioxidant properties, making them valuable in pharmacological research. To date, only four carbazole alkaloids have been identified within the Meliaceae family, all originating from the genus Ekebergia. These include ekeberginine (104), n-methylekeberginine (105), indizoline (106), and heptaphylline (107). The main structural difference between compounds 104 and 105 is the N-substitution, with 105 having a methyl group on the nitrogen atom, whereas 104 remains unsubstituted. Compound 106 also attaches methoxy and prenyl substituents but is distinguished by the position of its functional groups. Compound 107, in contrast, incorporates a hydroxyl group at C-2 and an aldehyde at C-3, along with a prenyl side chain, further diversifying the substitution pattern of this class [92].

4.2.6 Pyrrole, piperidine, indole, pyrazine, and β-carboline alkaloid

Beyond amides, several other nitrogen-containing alkaloid classes, including pyrrole, piperidine, indole, pyrazine, and β-carboline alkaloids, have also been identified in various species of the Meliaceae family, reflecting the structural diversity within this plant group. Among these, the pyrrole alkaloid β-D-glucopyranos-1-yl-N-methylpyrrole-2-carboxylate (108) was isolated from the roots of Aglaia odorata Lour. [93], representing a rare sugar-conjugated derivative in the family. In contrast, a structurally more complex piperidine alkaloid, 1-acetyl-4, 4-bis[4-(3-bromopropoxy)-3, 5-dimethoxyphenyl]piperidine (109), was obtained from the methanolic extract of Swietenia mahagoni (L.) Jacq. Leaves [94], showcasing a substituted piperidine scaffold bearing brominated side chains. Among the limited indole-derived metabolites reported in the Meliaceae family, methyl indole-3-carboxylate (110) has been isolated from the leaves of Melia azedarach L. [95]. Another pyrazine alkaloid, xylogranatinin (111) was found for the first time in the fruits of Xylocarpus granatum J.Koenig [96], and later detected in the leaves and twigs of Amoora ouangliensis (H.Lev.) C.Y.Wu [93]. This compound marks one of the few pyrazine representatives in the family and may hold ecological or defensive roles. Among the most biologically intriguing are the β-carboline alkaloids, a class known for their neuropharmacological and cytotoxic properties, have also been reported from Meliaceae species. Notably, 4, 8-dimethoxy-1-vinyl-β-carboline (112) and 4-methoxy-1-vinyl-β-carboline (113) have been reported by [97] from the cortex of Melia azedarach L. The structural difference between compounds 112 and 113 lies solely in the substituent at C-8, with compound 112 bearing a methoxy group, whereas compound 113 is unsubstituted at this position.

The biosynthesis of β-carboline alkaloids involves the condensation of tryptamine with a compound containing an aldehyde carbonyl group, resulting in an imine structure. Cyclization of the amine with the double bond on the indole forms a heterocyclic three-ring structure, which yields β-carboline through oxidation (Fig. 5) and the compound structures (Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9).

The biosynthetic pathways of β-carboline alkaloids

The chemical structures of compounds 46–65

The chemical structures of compounds 66–86

The chemical structures of compounds 87–103

The chemical structures of compounds 104–113

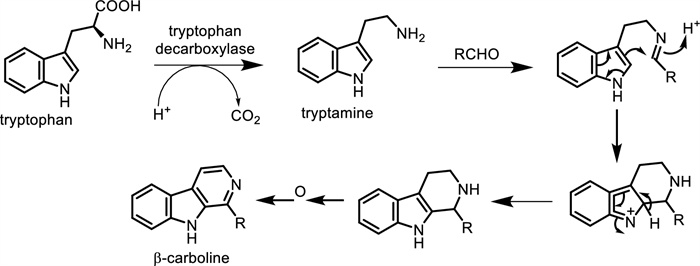

4.3 Nitrogen-containing flavaglines

Flavaglines have garnered significant interest due to their ability to inhibit translation initiation by targeting eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A (eIF4A). This mechanism has been shown to disrupt cancer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis, making flavaglines promising leads for anticancer drug development. Rocaglamide and its analogs have exhibited potent activity against hematologic malignancies, pancreatic cancer, and neuroblastoma in preclinical studies. Additionally, flavaglines demonstrate anti-inflammatory effects by modulating NF-κB signaling, a key pathway involved in immune responses and inflammation. Moreover, flavaglines such as aglaroxin derivatives have been investigated for their neuroprotective properties, showing potential in treating neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Some derivatives have also displayed antiviral activity, particularly against RNA viruses, highlighting their broad-spectrum therapeutic potential [98, 99].

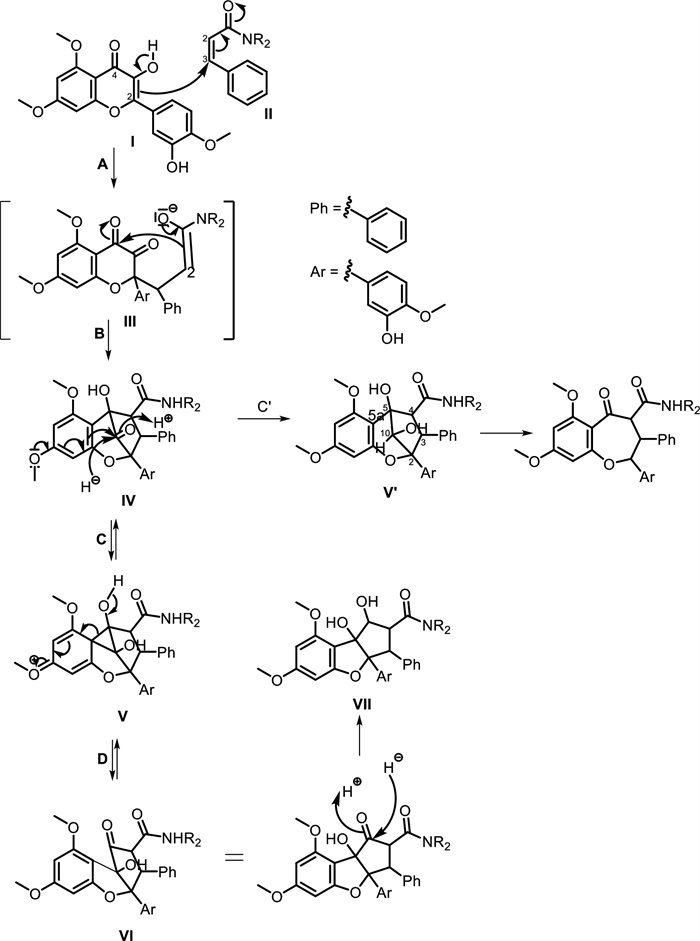

Despite their promising bioactivities, flavaglines face challenges related to bioavailability and synthetic accessibility. Ongoing research focuses on optimizing their pharmacokinetic properties and developing synthetic analogs with improved solubility and stability. High-throughput screening, computational modeling, and synthetic biology approaches are being employed to enhance flavagline-based drug discovery. Flavaglines have been identified as the only class of natural products peculiar to the genus Aglaia (Meliaceae). Due to their structural uniqueness and restricted taxonomic distribution, flavaglines are widely recognized as reliable chemical markers for species of this genus. The genus Aglaia remains an invaluable source of novel flavaglines, and further exploration of its chemical diversity is warranted. These nitrogen-bearing derivatives are relatively rare and exhibit significantly more complex molecular architectures, incorporating functionalities such as carboxamides, diamides, and nitrogen-containing heterocycles, which are uncommon in typical flavagline scaffolds. According to [100], the flavaglines can be divided into three subtypes namely, cyclopenta[b]benzofuran, cyclopenta[bc]benzopyran, and benzo[b]oxepines (see proposed biosynthetic pathway presented in Fig. 10). The enolate subunit I is believed to be incorporated into the α, β-unsaturated amide Ⅱ through a Michael 1, 4-type mechanism in the initial C, C linking step (step A), which occurred between C-2 of flavonoid I and C-3 of cinnamonate amide Ⅱ. The preceding flavonoid's C-4, which was a strongly active carbonyl group, could be attacked by the C-2 atom of the enolate Ⅲ, creating a 5-membered ring that produced Ⅳ (step B). The formation of Ⅳ represented an essential metabolic step, serving as a precursor to derivatives of rocaglamide and aglain. Moreover, Ⅳ was a dehydroaglain derivative, and the equivalent aglain derivative V' (step C') could be obtained by a straightforward reduction step with H potentially representing NADPH or the associated nucleophile H. The intramolecular migration of electron-rich substituted aromatic rings of the phloroglucinol type was capable of being rearranged by migrating from the original C-4 to C-3 in the flavonoid. This reduction yielded derivative V to stabilize the strained molecule Ⅳ. The use of the cyclopropyl derivative V as an s-complex (steps C and D) allowed for a mechanistic understanding of this process as an electrophilic aromatic substitution. This process transformed the hydroxyketone Ⅳ into the isomeric hydroxyketone Ⅵ, which was a derivative of dehydrorocaglamide. A final stabilizing reduction (step E) yielded the derivative rocaglamide Ⅶ, confirming the potentially reversible mechanism [38, 101]. The cyclopenta[bc] benzopyran skeleton could be formally divided into the benzo[b]oxepine by oxidative cleavage at the methylene bridge connecting C-5 and C-10 [102].

Proposed biosynthetic pathways of flavaglines

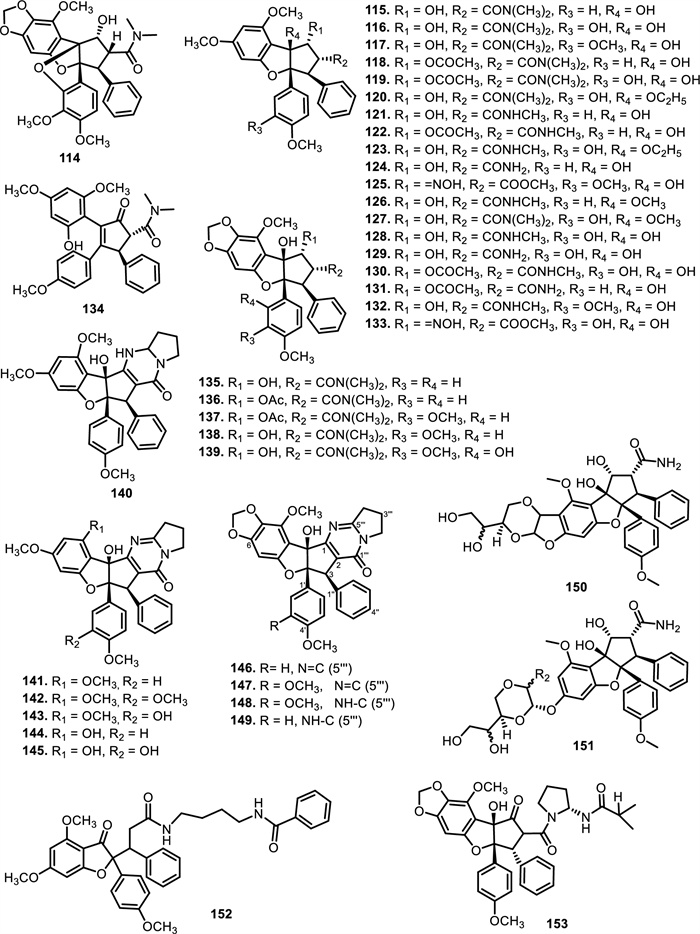

Cyclorocaglamide (114) was isolated from the twigs of Aglaia oligophylla Miq. [103], while rocaglamide (115) has been isolated from Aglaia elliptifolia Merr. (syn. Aglaia rimosa (Blanco) Merr.), Aglaia odorata Lour. and Aglaia formosana Hayata (syn. Aglaia elaeagnoidea Benth.). Rocaglammides D (116), AB (118), I (119), Q (121), W (122), AY (125), and aglaroxin E (117) have also been successfully isolated from the twigs, flowers, bark, and roots of Aglaia odorata Lour., Aglaia duperreana Pierre, and Aglaia roxburghiana Miq. [36-38, 103-107]. Structurally, most of these compounds preserve the cyclopenta[b]benzofuran or [bc]benzopyran core, but are further elaborated with nitrogen-containing moieties that often include amide linkages at C-2 or C-8b. These modifications result in increased molecular weight, additional hydrogen-bonding capacity, and altered polarity compared to their non-nitrogenous counterparts. Notable examples include 3'-hydroxy-8b-ethoxy-rocaglamide (120), 3'-hydroxy-8b-ethoxy-desmethylrocaglamide (123), aglaroxin A (135), and the highly modified compounds 150 and 151, which feature multi-substituted diamide side chains fused to complex oxygenated skeletons. Compounds 120 and 123 were successfully purified by [106] from the flowers of Aglaia duperreana Pierre, in which the hydroxyl group at C-8b was substituted with an ethoxy group. Additionally, two known compounds have been isolated and elucidated, 130 and 131. Didesmethylrocaglamide (124) was isolated from seeds of Aglaia argentea Blume [76] and leaves, twigs, and fruits of Aglaia perviridis Hiern [27]. A total of four rocaglamide derivatives were purified from Aglaia odorata Lour. twigs, where two new compounds were elucidated as 8b-methoxy-desmethylrocaglamide (126) and 3'-hydroxy-8b-methoxy-rocaglamide (127). Meanwhile, two known compounds were designated as 3'-hydroxy-desmethylrocaglamide (128), and 3'-hydroxydidesmethyl rocaglamide (129) [38, 107].

The compound 3'-methoxy-N-demethylrocaglamide (132) has been isolated from twigs and leaves of Aglaia odorata Lour. [35], while 134 was obtained from roots and stems of Aglaia elliptifolia Merr. [108]. In addition to 117, aglaroxin A (135) was found in Aglaia roxburghiana Miq., Aglaia oligophylla Miq., and Aglaia edulis A.Gray bark, including 136 and (137) [62]. Aglaroxin B (138), F (139), D (140), C (146), G (147), H (148), I (149), J (169), 14 (170), 15 (171), and 16 (172) were obtained from Aglaia roxburghiana Miq. stem barks [37]. Additionally, 140 was found in Aglaia odorata Lour. leaves [109] and Aglaia duperreana Pierre twigs [110]. Dehydroaglaiastatin (141) was identified as a compound present in the entire tree of the species Aglaia odorata Lour., Aglaia formosana Hayata, and Aglaia duperreana Pierre. Aglaiformosanin (142), and a new cytotoxic cyclopenta[b]benzofuran derivative, was identified in the stem bark of Aglaia formosana Hayata. Furthermore, compound 3'-hydroxyaglaroxin C (143) was obtained from Aglaia formosana Hayata flowers and Aglaia odorata Lour. twigs and leaves [34, 105]. The roots of Aglaia gracilis A.C.Sm. contained new compounds namely, marikarin (144) and 3'-hydroxymarikarin (145). [111] reported the following new compounds, (1R, 2R, 3S, 3aR, 8bS, -1‴S, 2‴R, 4‴R)-4‴-[(R)-1, 2-dihydroxy ethyl]-1, 8b-dihydroxy-8-methoxy-3a-(4-methoxy phenyl)-3-phenyl-1, 2, 3a, 8b, 1‴, 2‴, 3‴, 4‴-octa hydro-8H-cyclopenta [4, 5] furo[3, 2-f] [1, 4] dioxino [2, 3-b]benzo furan-2-carboxamide (150) and (1R, 2R, 3S, 3aR, 8bS)-4‴-{[(2‴R, 4‴R)-4‴-[(S)-1, 2-dihydroxyethyl]-3-hydroxy-1, 4-dioxan-2-yl] oxy}-1, 8b-dihydroxy-8-methoxy-3a-(4-methoxy phenyl)-3-phenyl-2, 3, 3a, 8b-tetrahydro-1H-cyclopenta [b]benzofuran-2-carboxamide (151), which have been isolated from roots of Aglaia perviridis Hiern. Meanwhile, from the leaves of Aglaia perviridis Hiern and twigs of Aglaia oligophylla Miq., (±) aglapernin (152) and isothapsakone A (153) have been isolated. The compound ponapensin (154) was reported by [112] in the stems and leaves of Aglaia ponapensis Kaneh.

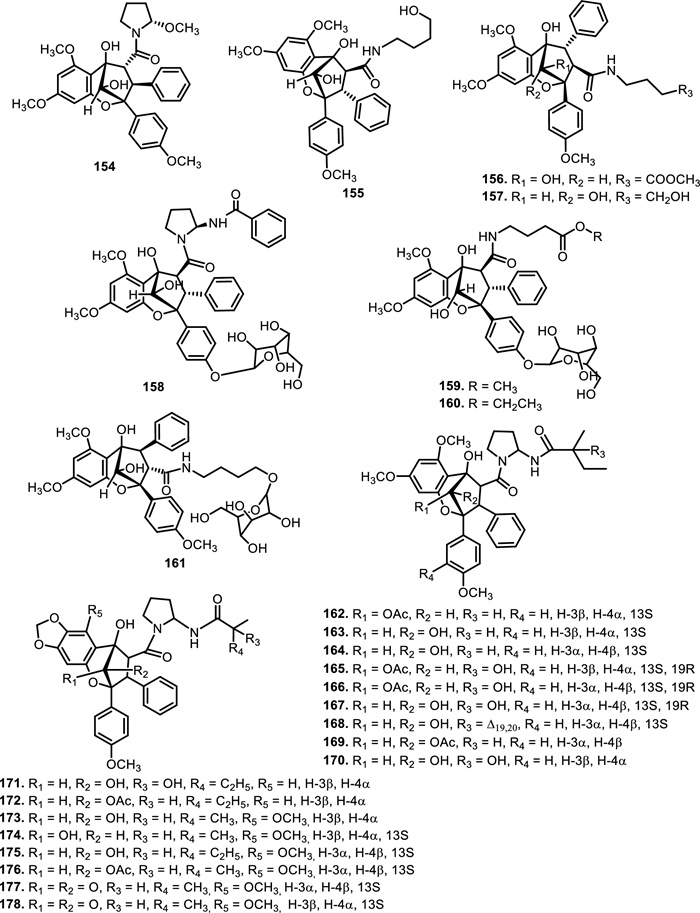

This type of N-functionalization introduces significant conformational rigidity and new intermolecular interaction opportunities, especially through hydrogen bonding and dipole interactions, which are highly relevant in biological target binding. For example, in compound 129, the nitrogen moiety contributes to enhanced cytotoxic activity through increased solubility and potential interaction with ribosomal eIF4A, a validated target of flavaglines. Similarly, compound 150, which possesses an additional amide bridge and hydroxylated aliphatic side chain, may exhibit a unique three-dimensional pharmacophore capable of engaging in multivalent interactions with biological macromolecules. Interestingly, the presence of nitrogen at critical positions such as C-2 or C-8b also affects the electronic properties of the flavagline core, potentially modulating π-stacking and cation–π interactions involved in protein recognition. Furthermore, the substitution pattern, such as ethoxy groups (as in 120) or fused 1, 4-dioxino rings—could influence the molecule's metabolic stability and resistance to enzymatic degradation, factors which are crucial for drug development [113]. succeeded in isolating eight derivatives of 2, 3, 4, 5-tetrahydro-2, 5-methanobenzo[b]oxepine, aglaodoratins A-G, and H (189–195, and 155), and tetrahydrocyclopenta[b]benzofuran derivatives, aglaodoratin I (133), from the leaves of Aglaia odorata Lour. Research conducted by [114] also reported the existence of eight new rocaglate biosynthesis precursors. These included aglapervirisins B-G (213–218) and H-I (156–157), which are found in Aglaia perviridis Hiern leaves. Subsequently [26], reported that aglapervirisin J-M (158–161) had been discovered in the same species and plant parts.

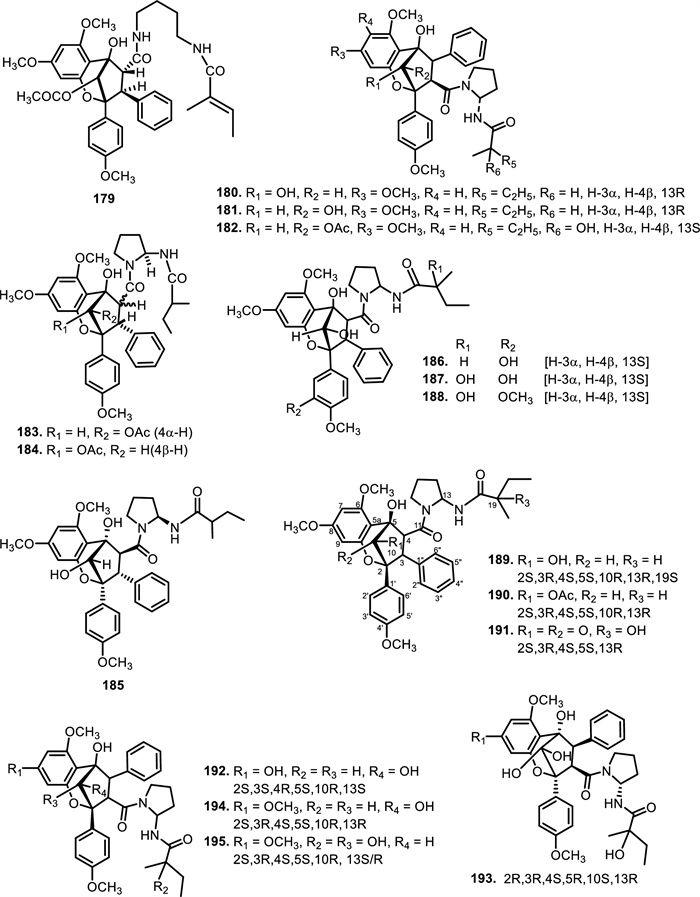

The diversity in structural motifs among nitrogen-containing flavaglines reflects divergent biosynthetic strategies likely driven by ecological or evolutionary pressures. While many canonical flavaglines arise from polyketide–terpenoid hybridization followed by oxidative cyclization, these N-containing derivatives seem to follow more elaborate biosynthetic tailoring, possibly through non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS)-like enzymes or transaminase-mediated modifications. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that some of the most complex members (e.g., 150 and 151) harbor multiple oxygen and nitrogen atoms within extended ring systems that cannot be easily rationalized by typical type Ⅰ PKS/terpene biosynthesis alone. Further study showed that several new compounds, aglains A (162), B (163), and C (164) have been isolated from Aglaia argentea Blume leaves and possess a cyclopentatetrahydrobenzopyran type structure. Aglaia forbesii King barks and Aglaia elliptica Blume leaves yielded 162 [76, 78]. The leaves of Aglaia laxiflora Miq. yielded aglaxiflorin A (165), B (166), C (182), and D (167). Moreover, 167 was found in Aglaia laxiflora Miq., Aglaia testicularis C.Y.Wu leaves [73], Aglaia odorata Lour. leaves [34, 40], Aglaia roxburghiana Miq. stembarks [37], while 168 was purified from Aglaia elliptifolia Merr. leaves. [115] succeeded in isolating new flavagline compounds from Aglaia edulis (Roxb.) Wall. rootbarks, as derivatives of cyclopenta[bc]benzopyrans (173–178) and benzo[b]oxepines (226–228). Other new cyclopentatetrahydrobenzopyran compounds were obtained from Aglaia forbesii King bark, namely aglaforbesiin A (180) and B (181) [76].

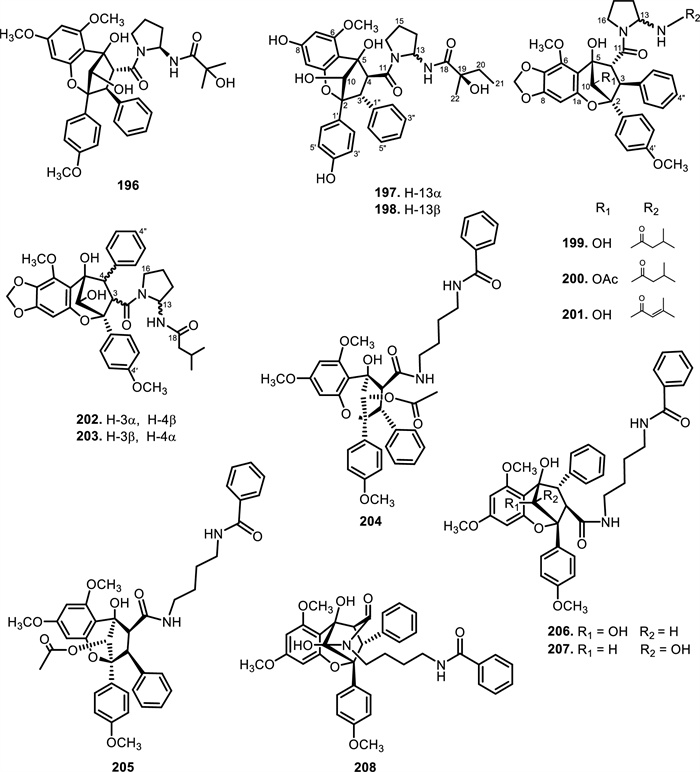

The genus Aglaia is very rich in flavagline compounds, containing diamide as a derivative. Moreover, two new diamide compounds have been discovered from the stems and leaves of Aglaia elliptica Blume, namely 10-O-acetylaglain B (183) and 4-epiaglain A (184) [78]. [67] explored Aglaia gracilis A.C.Sm. leaves and reported the presence of desacetylaglain. Aglain derivatives were isolated and elucidated with C-3'-hydroxyaglain C (186), C-19, C-3'-dihydroxyaglain C (187), and C-19-hydroxy, C-3'-methoxyaglain C (188) [38]. Recently, other compounds of aglains were found in Aglaia odorata Lour. twigs and leaves as well as agldorate A (196), B (197), and C (198) [34].

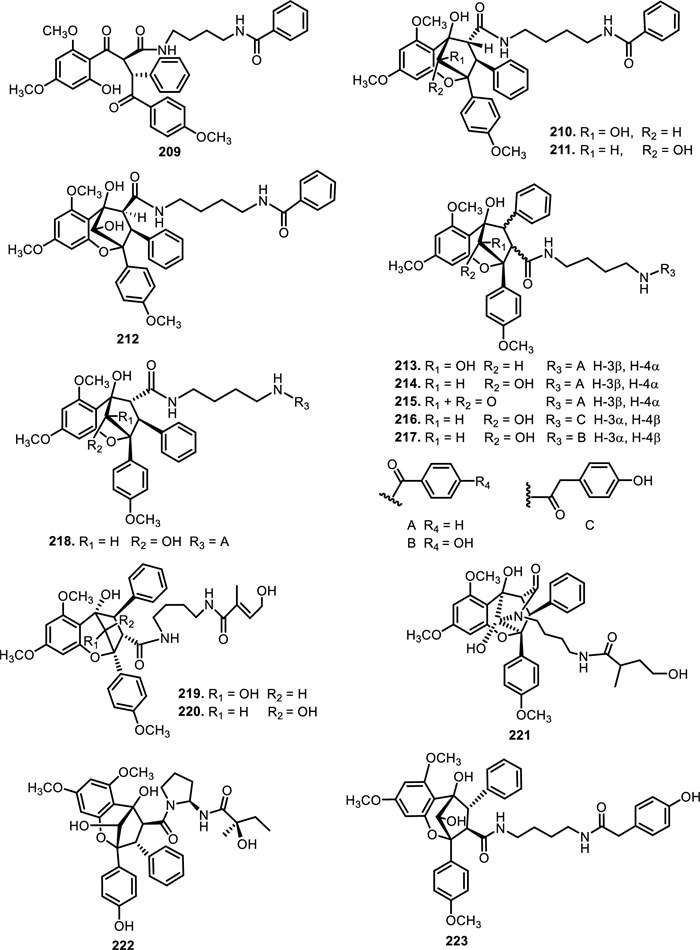

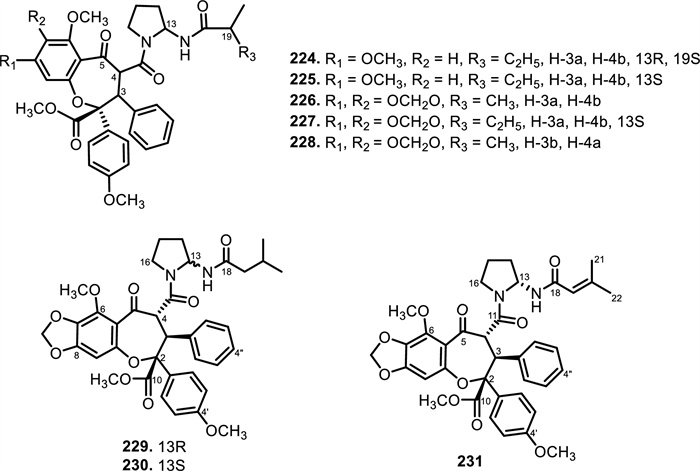

Cyclopenta[bc]benzopyrans are derivatives of flavagline, which is commonly found in Aglaia. A total of five new compounds have been found in the bark of Aglaia edulis (Roxb.) Wall., namely edulirin A (199), edulirin A-10-O-acetate (200), 19, 20-dehydroedulirin A (201), isoedulirin A (202) and edulirin B (203) [62]. Two other compounds derived in the leaves of Aglaia andamanica Hiern, were pyramidaglain A (204) and B (205). The structure of compounds 204 and 205 is similar to foveoglin A (206), isolated from Aglaia foveolata Pannell leaves, with the exception of substituents placed at positions 3 and 4. Meanwhile, the C-10 epimer of compound 206 is referred to as foveoglin B (207). The presence of an acetyl group on C-10 led to isofoveoglin (212), which was also found in Aglaia forbesii King leaves. Compounds 208 and 209 are also new compounds from Aglaia foveolata Pannell leaves, with 209 having a cleaved oxepine ring. Compounds 210 and 211 were separated from the leaves of Aglaia forbesii King [66, 69]. From the leaves, twigs, and fruits of Aglaia perviridis Hiern derivatives of benzopyrans, perviridisin A (219) and B (220) were isolated. Interestingly, structurally distinct flavagline-related metabolites were also found in other species. Hydroxytigloyl-1, 4-butanediamidecyclofoveoglin (221) was isolated from Amoora cucullata Roxb. leaves, 4′-O-demethyl-deacetylaglaxiflorin A (222) from Aglaia odorata, and Aglaiamide B (223) from Aglaia perviridis [27, 35, 64, 85] indicating convergent biosynthetic routes among Meliaceous genera. Additional benzooxepine derivatives have been discovered from Aglaia species, including forbaglin A (224) and B (225) from A. forbesii bark [76]. Likewise, edulisone A (229), edulisone B (230), and 19, 20-dehydroedulisone A (231) were isolated from the bark of A. edulis (Table 2, Figs. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16), expanding the chemical repertoire with oxygen-bridged ring systems that may contribute to their unique biological behavior. Taken together, these findings illustrate not only the rich chemodiversity of Aglaia but also highlight the frequent occurrence of structural motifs such as epimerization, acetylation, hydroxylation, and nitrogen incorporation. Such variations can profoundly influence the physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of these molecules, and continued phytochemical exploration of this genus holds promise for identifying novel bioactive compounds [62, 116].

N-containing flavaglines on Meliaceae family

The chemical structures of compounds 114–153

The chemical structures of compounds 154–178

The chemical structures of compounds 179–195

The chemical structures of compounds 196–208

The chemical structures of compounds 209–223

The chemical structures of compounds 224–231

4.4 Nitrogen-containing limonoids

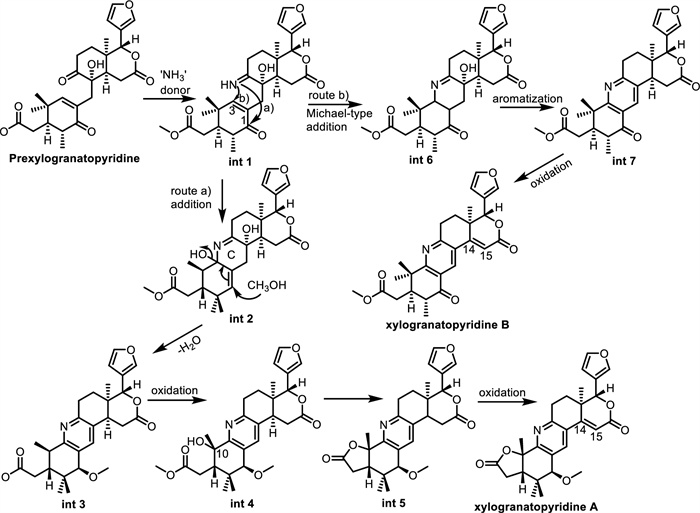

Limonoids, a major class of highly oxygenated triterpenoids in the Meliaceae family, are typically rich in oxygen atoms. However, the rare occurrence of nitrogen-containing limonoids represents a significant structural deviation, introducing unique features that often correlate with enhanced or diversified biological activities. This uncommon modification has drawn considerable interest for its potential in natural product chemistry and drug development. Figure 17 presents the proposed biosynthetic pathway leading to nitrogen-containing limonoids, using xylogranatopyridines A and B as examples. Prexylogranatopyridine is proposed as a common biosynthetic precursor for both xylogranatopyridines A and B. This compound may undergo a formal Schiff base reaction with ammonia to yield the key intermediate, int 1, which can proceed via two alternative pathways: a nucleophilic addition at the C-1 position (route a) forming int 2, or an intramolecular Michael addition at C-3 (route b) leading to int 6. In route a, int 2 may then undergo aromatization of ring C to form a pyridine ring, followed by oxidation at C-10 and γ-lactonization, ultimately resulting in the formation of the Δ14(15) double bond and production of xylogranatopyridine A. In route b, aromatization of int 6 could yield intermediate int 7, which upon oxidation may lead to the formation of xylogranatopyridine B [117].

Proposed biosynthetic pathway to nitrogen-containing limonoids

Among Meliaceae genera, Xylocarpus is notably prolific in nitrogenous limonoids, with granatoine (232) [118], from the seeds, twigs, and leaves of Xylocarpus granatum J.Koenig, xylogranatine F (234), xylogranatopyridines A (237) and B (238) [117, 119]. Meanwhile, hainangranatumin G (233), xylogranatine G (235), H (236), and xylomexicanin E (239) were only found in the seeds of Xylocarpus granatum J.Koenig [119-121]. Compounds 232–238 are aromatic B-ring limonoids that feature a pyridine ring with variations in the substitutions at the C-3 position. Compound 232 contains a hydroxyl group at the β-position, while compound 236 has a hydroxyl group at the α-position. Compound 233 is substituted with an ethoxy group, 234 has a hydrogen atom, and 235 features an acetyl group. Compound 237 contains a methoxy group, while 238 is characterized by a carbonyl group. Thaixylomolin B (240) and C (241) were isolated for the first time from seeds of Xylocarpus moluccensis M.Roem. that contain a unique pentasubstituted pyridine scaffold [122].

Beyond Xylocarpus, nitrogen-containing limonoids have been identified in Azadirachta indica A. Juss. seeds, including azadiramide A (242) and B (243) [123, 124]. Azadirachta indica A. Juss. leaves were found to contain compounds 244 and 247 [125, 126], while Salannolactam-(21) (245) and Salannolactam-(23) (246) have been obtained from Azadirachta indica A. Juss. seed kernels [127]. Another Meliaceae genus that yielded nitrogen-containing limonoids was Entandrophragma. From Entandrophragma angolense C.DC. stem barks, the compound entangolensin K (248) was isolated was isolated [128]. Entanutilin B (249), a mexicanolide-type limonoid with 1, 8-ketals was obtained from the stem bark of Entandrophragma utile Sprague. [129, 130] also isolated 249 with other new limonoid compounds of the highly oxygenated and rearranged phragmalin type. These included entanutilin C (250), entanutilin J (251), 12α-acetoxyphragmalin-3 nicotinate-30-isobutyrate (14) (252), entanutilin P (253), and entanutilin Q (254). Compounds 250, 252, and 253 have a characteristic orthoester bridge spanning C-1, C-8, and C-9. These compounds exhibit extensive structural modifications, including multiple nicotinyl ester, isobutyryl, and acetyl groups at C-3, C-12, and C-30, respectively. A fused δ-lactone ring at C-19 and the presence of a substituted furan moiety further distinguish these molecules).

Extensive structural diversity has also been reported from Amoora tsangii (Merr.) X.M.Chen, which yielded twelve nitrogenous limonoids, amooramides A–L (255–266). These compounds are characterized by a highly oxygenated tetranortriterpenoid skeleton bearing a fused ε-lactone ring and diverse lactam side chains at C-17. Compounds 255–266 exhibit structural diversity, primarily variations including acetoxy, formyloxy, benzoyloxy, acyloxy, and 2-methylbutanoyloxy group at C-11 and C-12, and different acyl or alkyl groups attached to the lactam side chain at C-17 [131]. Similarly, Munronia species such as Munronia henryi Harms and Munronia pinnata (Wall.) W.Theob. yielded munroniamide (267), munronin D (268), and prieurianin-type limonoids muropin A (269) and B (270) characterized by α, β-unsaturated γ-lactam motifs [132, 133]. Subsequently, it was revealed the Turraea genus produced nitrogen-containing limonoids, namely turraparvin D (271) from Turraea parvifolia Deflers. seeds and turrapubesin B (272) from Turraea pubescens Hell. twigs and leaves [134-136].

Further investigations into Meliaceae alkaloids have highlighted the presence of azadirone- and gedunin-type limonoids. Toonasinemine A–G (273–279), five of which contain modified furan ring (275–279), were isolated from the root bark of Toona sinensis (A.Juss.) M.Roem. [137]. Other limonoids with a rare lactam E ring, toonasins A–C (280–282), were identified in the bark of the same species [138]. Meanwhile, [139] examined Toona ciliata M.Roem. twigs and observed that toonaolide I (283), R (284), X (285) in 2020, toonaone I (290), and ciliatones C-F (291–294) in 2021 were present [140]. Compounds 291–294 exhibit variability at positions C-4 and C-6, with substituents including methyl, acetoxy, and formyl groups. Specifically, ciliatone C (291) bears a methyl group at C-4 and no substitution at C-6, while ciliatone D (292) features an additional acetoxy group at C-6. Ciliatone E (293) presents a formyl group at C-4 and an acetoxy group at C-6, and ciliatone F (294) lacks substitution at C-4 but contains an acetoxy group at C-6. Complementing this, Toononoid B, D, H, and Toonanoronoid H (286–289) were isolated from leaves and twigs Toona ciliata var. yunnanensis [141].

Compared to Toona sinensis (A.Juss.) M.Roem., Trichilia sinensis Bentv. was reported to produce new compounds namely trichinenlide A (295), F (296), G (297), and trichiliasinenoid D (298), from leaves and twigs [142, 143]. Meanwhile, Trichilia connaroides (Wight & Arn.) Bentv. from the leaves and twigs were discovered to make triconoid A (299) and B (300) [142-144]. These compounds are limonoid derivatives featuring a mexicanolide skeleton, which have β-substituted furan ring and multiple ester substitutions. Notably, 297 contains an additional acetoxy substituent compared to 296, while 300 differs from 299 by the presence of a hydroxyl group at a previously unsubstituted position. Other nitrogen-containing limonoid derivatives included 6α, 7α-diacetoxy-3-oxo-24, 25, 26, 27-tetranorapotirucalla-1, 14, 20(22)-trien-21, 23-lactam (301) from Chisocheton paniculatus Hiernfruit, walsunoid I (302) from Walsura Robusta Roxb.leaves, and aphanalide M (303) in Aphanamixis grandifolia Blume fruit [145-147], further underscoring the structural breadth and ecological significance of nitrogenous limonoids in the Meliaceae family (Table 3, Figs. 18, 19, 20, 21).

N-containing limonoids on Meliaceae family

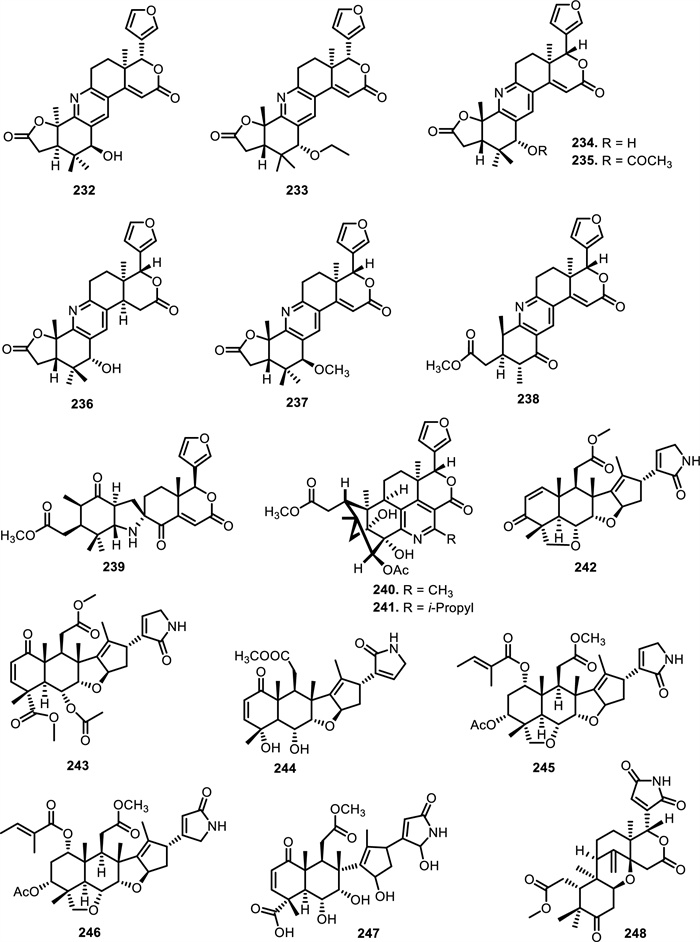

The chemical structures of compounds 232–248

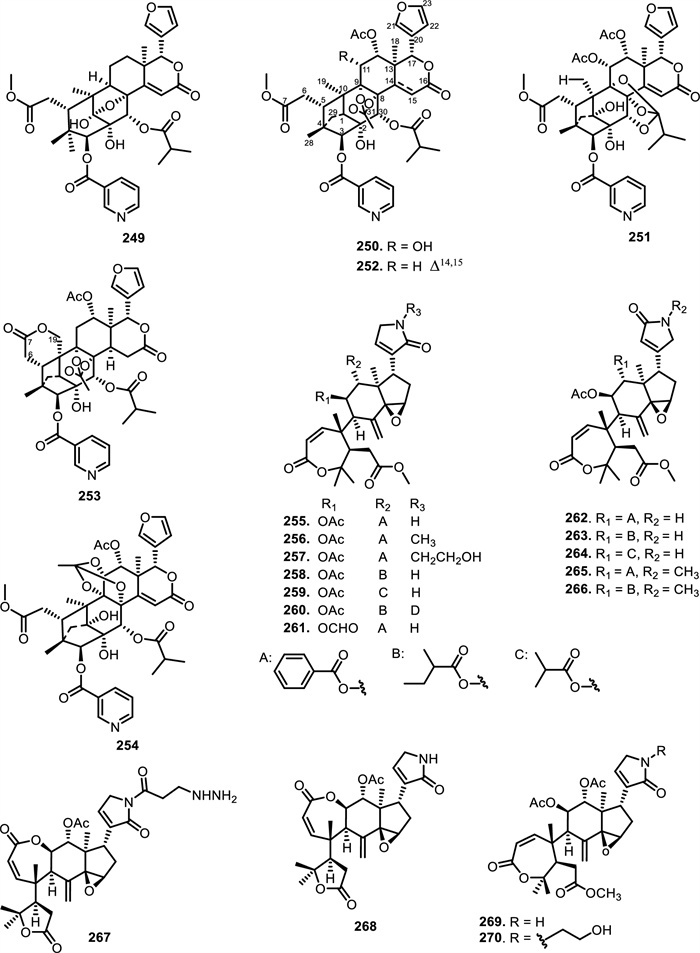

The chemical structures of compounds 249–270

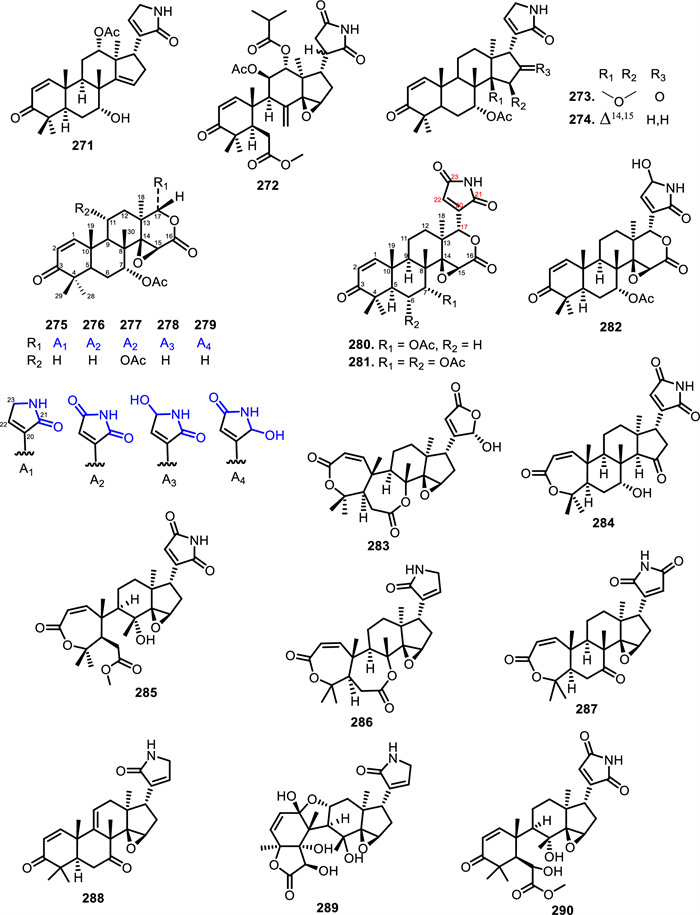

The chemical structures of compounds 271–290

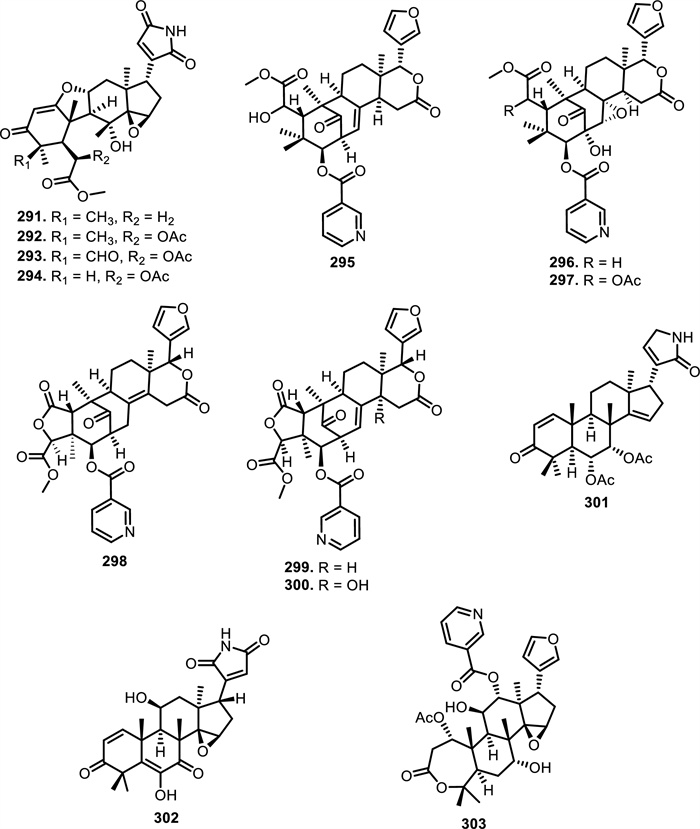

The chemical structures of compounds 291–303

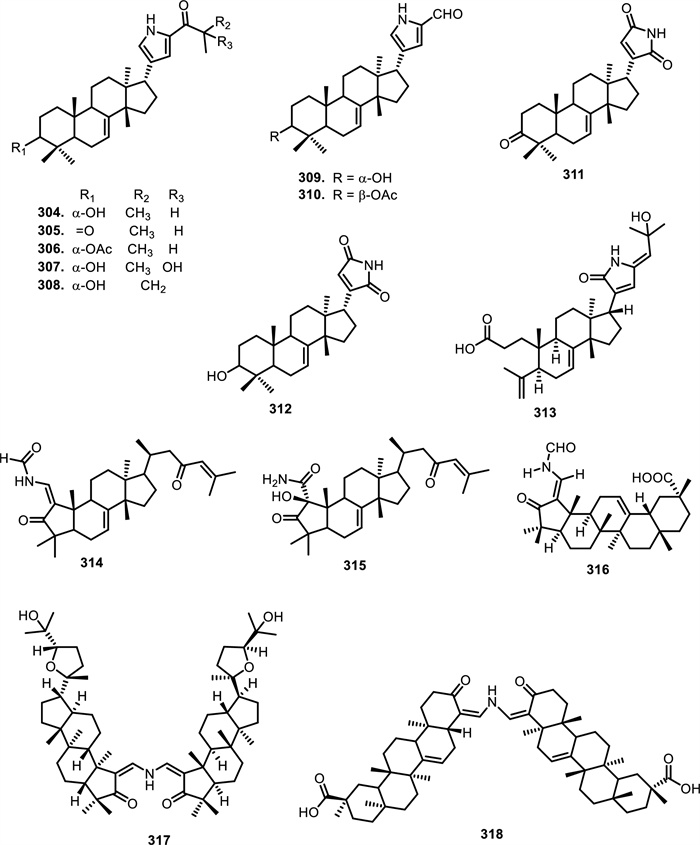

4.5 Nitrogen-containing triterpenoids

According to [148], eight tirucallane-type alkaloids, namely laxiracemosin A-H (304–311) were isolated from the bark of Dysoxylum laxiracemosum C.Y.Wu et H.Li. Additionally, compounds 304 and 311 were found in the stem bark of Aphanamixis grandifolia Blume [149]. Compound 311 was also reported in the leaves and twigs of Dysoxylum lenticellatum C.Y.Wu [150]. In compound 304, the structure is defined by a hydroxyl group at the α-position (C-3), a methyl group at C-26, and a hydrogen atom at C-25. Compound 305 has a carbonyl group at the C-3 instead of the hydroxyl group, while 306 contains an acetoxy group at C-3. Compounds 307 and 308 retain the hydroxyl group at C-3, but with variations in the substitutions at C-25, 307 has a hydroxyl group, while 308 has a methylene group. Compound 309 still carries a hydroxyl group at the α-position (C-3), but 310 has a β-acetoxy group instead of the hydroxyl group. Finally, compound 311 features a carbonyl group at the C-3, with a carbonyl groups at C-21 and C-23. Another chemical analysis of the leaves and twigs Dysoxylum lenticellatum C.Y.Wu produced dysolenticin J (312), which has a similar structure to 311. Compound 312 has a hydroxyl group at the C-3 instead of the carbonyl group [150]. [151] isolated congoensin A (313) from the bark of Entandrophragma congoense A.Chev. The phytochemical investigation of the stem of Aphanamixis grandifolia Blume resulted in the isolation of two tirucallane-type compounds, namely aphanamgrandin E (314) and F (315) [152]. An oleanane-type, which was dysoxyhainanin A (316), was isolated from the twigs and leaves of Dysoxylum hainanense Merr. [153]. Furthermore, two dimeric triterpenoids, namely silvaglenamin (317) were found in the root bark of Aglaia silvestris (M.Roem.) Merr. [154] and turraenine (318) was isolated from the leaves of Turraea sp (Table 4, Fig. 22).

N-containing triterpenoids on Meliaceae family

The chemical structures of compounds 304–318

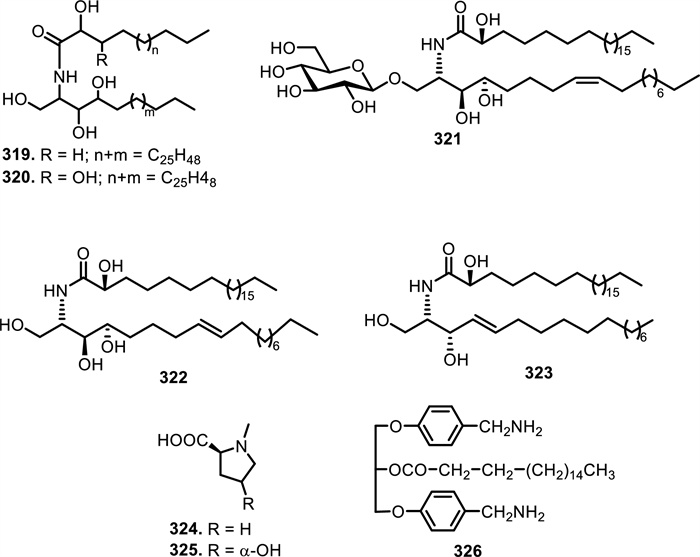

4.6 Others

Research has identified five ceramides isolated from Meliaceae plant species. Ceramides A (319) and B (320) were isolated from the twigs of Guarea mayombensis Pellegr. [155]. Other ceramides, including 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(2S, 3S, 4R, 8Z)-2-N-(2′-hydroxytetra cosanoyl)heptadecasphinga-8-ene (321), (2S, 3S, 4R, 8E)-2-N-(2′-hydroxy tetra cosanoyl)-hepta decasphinga-8-ene (322), and (2S, 3R, 4E)-2-N-(2′-hydroxytetracosanoyl)-heptadecasphinga-4-ene (323) were isolated from the whole bodies of Munronia henryi Harms [132]. Moreover, nitrogen-containing compounds featuring a proline backbone were produced by the leaves of Trichilia claussenii C.DC. N-methylproline (324) has a nitrogen atom bonded to a methyl group, which is the defining feature of this compound, differentiating it from regular proline. In 4-hydroxy-N-methylproline (325), a hydroxyl group is attached at C-4 on the pyrrolidine ring in addition to the methylated nitrogen. This modification introduces polarity, which may affect the compound's solubility and interactions in biological systems. The presence of the carboxyl group at the 2-position remains unchanged in both compounds, preserving their acidic properties. In addition, 1, 3-di-benzene carbon amine-2-octadecylic acid-glyceride (326) was isolated from the twigs of Carapa guianensis Aubl. [156, 157] (Table 5, Fig. 23).

N-containing others on Meliaceae family

The chemical structures of compounds 319–326

5 Biological activities

The presence of nitrogen in bioactive natural products significantly influences their pharmacological properties. Nitrogen-containing compounds (N-compounds) often exhibit enhanced bioactivity due to their ability to participate in hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, and molecular recognition processes with biological targets [158]. Nitrogen-containing functional groups, such as amines, amides, pyridines, and indoles, enhance molecular recognition by interacting with proteins, enzymes, and nucleic acids through hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions. This property is particularly evident in alkaloids, which frequently act on neurotransmitter receptors, ion channels, and enzymes. For example, β-carboline alkaloids interact with GABA receptors, contributing to their anxiolytic and sedative effects [159]. Similarly, nitrogen-containing flavaglines, such as rocaglamide, inhibit eukaryotic initiation factor 4A (eIF4A), thereby suppressing cancer cell proliferation. The ability of nitrogen-containing flavaglines to interfere with cellular translation makes them valuable anticancer leads.

Although Meliaceae family produces numerous nitrogen-containing compounds, there is no comprehensive discussion of their biological activities in the phytochemical literature. These compounds have a wide range of bioactivities, including cytotoxic effects against different cancer cell lines, insecticidal, anti-inflammatory, molluscicide, antibacterial, antimalarial, tyrosinase inhibition, osteoclast differentiation inhibition, and α-glucosidase inhibition activity. The diverse bioactivities underscore their importance in medicinal research and potential for developing new therapeutic agents.

5.1 Cytotoxic effects

Numerous alkaloids that have been isolated from Meliaceae family have been evaluated for cytotoxicity with human cancer cell lines. These compounds included amocurine A (20), B (21), and C (22), which showed significant antiproliferative activity against various cancer cells using the MTT assay. Cells were incubated with compounds for 72 h, and IC50 values were determined from three independent experiments. Compounds were dissolved in DMSO, with a final DMSO concentration not exceeding 0.5%. In alkaloids 20, 21, 25, and 26 were inactive against KB, and MCF-7, while 22 had significant activity against KB (IC50 = 3.5 ± 0.6 µM), and MCF-7 (IC50 = 4.2 ± 1.4 µM), as compared to the positive control doxorubicin with IC50 value of 0.5 ± 0.1 and 6.8 ± 0.1 μM, respectively. These alkaloids showed potential as antiproliferative agents targeting different cancer cell lines and suggest that the aporphine alkaloid's aromatic ring system (C6a = C7 bond), 1, 2-methylenedioxy ring, and the structure's planarity significantly influence antiproliferative activity. Amocurine C (IC50 = 6.7 µM) exhibited notable cytotoxicity against NCI-H187 cells, while amocurine B showed slightly lower potency (IC50 = 40.2 µM). This activity was appreciable, though not as strong as the positive controls (doxorubicin and ellipticine) with IC50 values of 0.7 ± 0.2 µM and 1.7 ± 0.1 µM, respectively. The findings highlight the potential of structural elements, such as the aporphine alkaloid's aromatic ring system and methylenedioxy ring, in enhancing cytotoxic properties [28, 45].

Compound 24 showed antiproliferative effects against KB cells (IC50 = 9.3 ± 0.8 µM), MCF-7 (IC50 = 10.1 ± 0.2 µM), and NCI-H187 (IC50 = 8.5 ± 0.5 µM) cancer cells, while 25 and 26 showed more modest activity against NCI-H187 cancer cells (IC50 = 30.4 ± 1.1 and 25.2 ± 0.8 µM). Alkaloids isolated from Amoora cucullata Roxb. could have potential as cancer drug leads [28, 45].

Transitioning to chromone alkaloids, rohitukine (32), isolated from Dysoxylum binectariferum, has garnered attention as the natural precursor of flavopiridol, a synthetic CDK inhibitor currently in Phase Ⅲ clinical trials. Rohitukine demonstrated moderate cytotoxicity against HL-60 (leukemia), HCT-116 (colon cancer), SKOV3 (ovarian cancer), and MCF-7 cells, with IC50 values ranging from 7.5 to 20 µM. These values were obtained using both sulforhodamine B (SRB) and MTT assays after 48 or 72 h of incubation. Although its potency is lower than flavopiridol, rohitukine remains a key lead compound for developing CDK-targeted therapies [55, 56]. Further expanding the diversity of active compounds, dysoline (45), also from D. binectariferum, displayed selective and potent cytotoxicity against HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells, with an IC50 value of 0.21 µM as determined via the MTT assay. Interestingly this compound appeared to show selectivity being apparently inactive on Colo205, HCT116, NCIH322, A549, MOLT-4, and HL60 cells at concentrations greater than 10 μM. Dysoline did not show activity against various kinases such as PKB-β, CDK2/A, CDK9/T1, Aurora A, Aurora B, AMPK (hum), CK12, CK1, DYRK1A, IGF-1R, IR, and VEGFR1 therefore its mechanism of action remains to be elucidated [33].

Among the most studied cytotoxic agents in this family are flavaglines, a unique group of cyclopenta[b]benzofurans primarily isolated from Aglaia species. For instance, rocaglamide (115) exhibited strong antiproliferative effects across KB, A549 (lung carcinoma), and HL-60 cells, with IC50 values typically in the nanomolar range (e.g., 0.01–0.08 µM), as determined via MTT assays conducted over 48–72 h. Aglapervirisin I (157) has been shown to have significant cytotoxic activity against various cancer cell lines, making it a promising candidate for further research in cancer treatment. IC50 values were reported to be 27.7 μM against HepG2 liver cancer cells, 29.4 μM against HL-60 leukaemia cells, 36.0 μM against MCF-7 breast cancer cells, and 23.1 μM against HT-29 colon cancer cells. Meanwhile, compounds 157 and 115 [26, 93, 160].

Based on the results, 3'-hydroxy-desmethylrocaglamide (128) showed higher activity against the K562 cell line with IC50 value of 4.5 μg/mL, compared to desmethylrocaglamide (121), which had IC50 value of 9.5 μg/mL. Compounds 126 and 127 were inactive on K562 cancer cell [107]. Didesmethylrocaglamide (124) showed significant activity against HT-29 (ED50 = 0.021 μM) [27]. Compound 132 showed cytotoxic effects against HeLa (IC50 = 0.32 μM), SGC7901 (IC50 = 0.12 μM), and A549 (IC50 = 0.25 μM) cancer cells [35]. These findings suggest that the presence of the OH group at C-8b is essential for enhancing the cytotoxic activity of the compound [27, 107].

Furthermore, aglaroxin A (135) is derivative featuring a cyclopentatetrahydrobenzofuran core, which is characteristic of rocaglamides from the Aglaia genus. It has a methylenedioxy group at C-6 and C-7 instead of the more common C-6 methoxy unit, influencing its biological activity and derivative, aglaroxin A 1-O-acetate (136), showed significant cytotoxic activity against various cancer cell lines. Compound 135 showed cytotoxic effects with ED50 values of 0.04 μg/mL against Lu1 lung cancer cells, 0.02 μg/mL against LNCaP prostate cancer cells, 0.06 μg/mL against MCF-7 breast cancer cells, and 0.1 μg/mL against HUVEC endothelial cells. In comparison, 136 showed greater potency with ED50 values of 0.001 μg/mL against Lu1, 0.01 μg/mL against LNCaP, 0.02 μg/mL against MCF-7, and 0.5 μg/mL against HUVEC cell line. These results showed the increased efficacy of the acetate derivative in inhibiting cancer cell growth [62]. Meanwhile, dehydroaglaiastatin (141) showed significant cytotoxic activity across a wide range of cancer cell lines, such as A549, HL-60, HT-29, KB, and P-388 (ED50 = 0.0012, 0.0010, 0.0015, 0.01, 0.0018 µM, successively) cancer cell lines, as compared to the positive control mithramycin with ED50 values of 0.08, 0.07, 0.09, 0.07, and 0.06 μg/mL, respectively. The presence of a cyclopentapyrimidinone subunit in the structure of compound 141 makes this compound highly cytotoxic against HepG2 cancer cells (IC50 = 0.69 ± 0.06 μM). Compound 141 also showed cytotoxic activity against HEL (IC50 = 0.03 ± 0.001 μM) and MDA-231 (IC50 = 1.06 ± 0.27 μM) cancer cells, as compared to the positive control adriamycin with IC50 values of 0.17 ± 0.02 and 0.54 ± 0.08 μM, respectively. However, 3'-hydroxyaglaroxin C (143) showed lower cytotoxic activity compared to 141, specifically against HEL cancer cells, with an IC50 value of 0.17 ± 0.06 μM. These results indicate that the addition of an OH group on the phenyl ring could decrease its cytotoxic activity against HEL cells [34, 161, 162].

Compounds 142 and 168 were evaluated using in vitro assays against A549 (lung), HL-60 (leukemia), HT-29 (colon), KB (nasopharyngeal), and P-388 (murine leukemia) cell lines. Compound 142 exhibited strong cytotoxicity with ED50 values of 0.014 μg/mL (A549), 0.012 μg/mL (HL-60), 0.011 μg/mL (HT-29), 0.025 μg/mL (KB), and 0.012 μg/mL (P-388). In comparison, the reference drug mithramycin displayed ED50 values of 0.08, 0.07, 0.09, 0.07, and 0.06 μg/mL, respectively, across the same cell lines. However, compound 168 showed markedly lower activity and was inactive against HL-60, HT-29, and KB cells under similar test conditions [34, 72, 161].

In a separate study, compound 151 demonstrated potent cytotoxicity against HT-29 (colon) and PC-3 (prostate) cancer cell lines, with IC50 values of 2.3 μM for both, as measured by the MTT assay after 72 h of exposure [111]. Additionally, several compounds including 142, 90, 91, 168, 92, and 93 were assessed for activity against the P-388 cell line. Among these, compound 142 again showed superior potency (ED50 = 0.012 μg/mL), while compounds 90, 91, and 168 yielded ED50 values of 3.62, 3.86, and 3.41 μg/mL, respectively. Compounds 92 and 93 exhibited moderate cytotoxicity with IC50 values of 7.6 and 8.5 μg/mL [65, 72, 88]. The result of compound 74 test against KB-V1 had ED50 10 μg/mL. Gigantamide A (83) was highly promising to HT-29 (ED50 = 0.021 μM), when 167 was inactive to P-388 and MOLT-4 but active to HEL (IC50 = 6.25 ± 0.26 μM) and MDA-231 (IC50 = 12.51 ± 0.31 μM) cancer cells, as compared to the positive control adriamycin with IC50 values of 0.17 ± 0.02 and 0.54 ± 0.08 μM, respectively [27, 34, 65, 77].

The difference in cytotoxic activity between nitrogen-containing and non-nitrogen-containing compounds in the study can be attributed to structural variations that influence their biological interactions. Rocagloic acid, which does not contain nitrogen, exhibited significantly higher cytotoxicity across multiple cancer cell lines, with ED50 values in the nanogram range. In contrast, the nitrogen-containing compounds, 168 and 90, showed much weaker activity, often exceeding 50 µg/mL in most cell lines. This difference is likely due to the presence of nitrogen-based functional groups, such as amides and heterocyclic rings, which can alter the compound's electronic distribution, molecular conformation, and ability to interact with biological targets. Additionally, the nitrogen groups may increase hydrophilicity, affecting the compound's ability to permeate cell membranes and reach intracellular targets effectively. Furthermore, rocagloic acid's rigid and planar structure may enhance its interaction with biological macromolecules, whereas the flexibility introduced by nitrogen-containing moieties in elliptifoline and elliptinol could reduce their binding affinity. These factors together contribute to the observed differences in cytotoxic potency, as supported by the study conducted by [72].

Aglaxiflorin C (182) has no activity on P-388 and MOLT-4 cell lines, indicating its limited anticancer potential under the tested conditions [77]. Similiarly, aglaodoratin A (189), B (190), and F (194), isolated from the leaves of Aglaia odorata Lour., were found to be inactive against MG-63, HT-29, and SMMC-7721 cancer cells, with IC50 values greater than 10 μM. However, aglaodoratins C-E (191–193) showed selective cytotoxicity against cancer cells. Notably, compound 191 exhibits a significant cytotoxic activity against MG-63 (IC50 = 1.2 μM) and HT-29 (IC50 = 0.097 μM) cancer cells, as compared to the positive control taxol with IC50 values of 0.832 and 0.002 μM, respectively but was inactive against SMMC-7721 (IC50 > 10 μM). Aglaodoratin D (192) showed cytotoxic activity specifically against MG-63 cancer cells (IC50 = 0.75 μM) but was inactive against HT-29 and SMMC-7721 cells (IC50 > 10 μM). Aglaodoratin E (193) showed cytotoxic activity against SMMC-7721 cancer cells (IC50 = 6.25 μM), as compared to the positive control taxol with IC50 value of 3.1 μM but was inactive against MG-63 and HT-29 (IC50 > 10 μM) [113]. Compound 90 was tested on the HL-60 cell lines with an ED50 of 32.1 μg/mL but was inactive against A549, HT-29, and KB cell lines. Compounds 74, 77, and 78 were very promising against KB-V1* cells (resistant in 1 μg/mL vinblastine) with ED50 values of 8.5, 6.4, and 4.2 μg/mL, respectively [65, 72].

Further investigations into compounds 196–198 showed varied cytotoxic activity against different cancer cell lines. Compound 196 showed cytotoxic activity against HEL cancer cells (IC50 = 8.40 ± 0.85 μM), as compared to the positive control adriamycin with IC50 value of 0.17 ± 0.02 μM but was inactive against MDA-231 cells (IC50 > 20 μM). Compounds 197 and 198 were inactive against both HEL and MDA-231 cells (IC50 > 20 μM) suggesting that the presence of two OH groups on the benzene ring may reduce cytotoxic activity. Compound 222 was inactive against HeLa, SGC7901, and A549 cancer cells [34, 35]. Compared to the research by [62], compounds 199–203 and 231 were inactive on Lu1, LNCaP, MCF-7, and HUVEC cancer cells (ED50 > 5 μg/ mL).

Compounds 206–209 and 212 showed varying degrees of cytotoxic activity against Lu1, LNCaP, and MCF-7 cancer cells. Specifically, compound 206 showed cytotoxic activity with ED50 values of 1.8 μM for Lu1, 1.4 μM for LNCaP, and 1.8 μM for MCF-7 cancer cells, as compared to the positive control paclitaxel with ED50 values of 0.0023, 0.0047, and 0.0007 μM, respectively. Compound 212 was moderate with ED50 values of 17.5 μM for Lu1, 21 μM for LNCaP, and 16.1 μM for MCF-7. Compound 208 also showed moderate activity with ED50 values of 18.1 μM for Lu1, 16.0 μM for LNCaP, and 13.5 μM for MCF-7. Meanwhile, compounds 207 and 209 were inactive against all three cell lines (ED50 > 20 μM). This study has demonstrated that certain derivatives of cyclopenta[b]benzopyran may exhibit cytotoxic properties, influenced by the positions of substituents at C-3 and C-4, type of the amide moiety, and the orientation of the OH-10 [66].

Similar to 209, compounds 213, 214, 215, and 218 have no activity against HepG2, HL-60, MCF-7, and HT-29 cancer cells, with IC50 values greater than 50 μM. However, compound 216 showed significant cytotoxic activity against HepG2 (IC50 = 10.9 μM), HL-60 (IC50 = 2.2 μM), MCF-7 (IC50 = 8.5 μM), as compared to the positive control cis-platinum with IC50 values of 8.2, 2.5, and 6.4 μM, respectively. This compound was also found to show cytotoxicity against HT-29 cells (IC50 = 1.4 μM), as compared to the positive control taxol with IC50 value of 0.002 μM [114]. Compound 219 had no potential against HT-29 cancer cells (ED50 > 10 μM), while its C-10 epimer 220 showed significant activity (ED50 = 0.46 μM) [27]. Compound 239 denoted inactive against A549, RERF, PC-3, PC-6. QG-56, and QG-90 cell lines (IC50 > 100 µM) (Wu et al., 2014). 248 was non-active on HepG2 and MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 > 50 μM [128].

Compounds 242 and 243 showed cytotoxic activity against MDA-MB-231 cancer cells with IC50 values of 2.70 ± 0.63 μM and 15.73 ± 6.07 μM, respectively, as compared to the positive control cisplatin with IC50 value of 1.70 ± 0.43 μM [124, 125]. Meanwhile, compounds 249–254 have been tested for MDR reversal ability on MCF-7/DOX cells, showing inactive results and were unable to overcome multidrug resistance in breast cancer cells [129, 130].

Based on the analysis, compounds 269 and 270 were inactive against Hela and A549 cancer cells. Compound 273 showed cytotoxic activity against HepG-2 cancer cells with an IC50 of 40.67 ± 3.23 μM and was inactive on MCF-7 as well as U2OS cancer cells (IC50 > 50 μM). Compound 274, 275, and 277–279 were inactive on HepG-2, MCF-7, and U2OS cancer cells (IC50 > 50 μM). Meanwhile, compound 276 showed activity against HepG-2 (IC50 = 11.63 ± 1.02 μM) and MCF-7 (IC50 = 36.77 ± 2.79 μM) cancer cells, as compared to the positive control doxorubicin with IC50 values of 3.25 ± 0.29 and 1.93 ± 0.15 μM, respectively but was inactive on U2OS. Compound 282 showed significant cytotoxic activity against a range of cancer cell lines. The IC50 values for HL-60, SMMC-7721, A549, MCF-7, and SW480 were 18.61 ± 0.14, 19.55 ± 0.19, 15.07 ± 0.13, 17.79 ± 0.15, and 12.47 ± 0.11 μM, respectively. This showed that compound 282 has considerable potential as an anticancer agent, showing the highest activity against the SW480 cell line. Other compounds, including 286, 287, 288, and 289, isolated from Toona ciliata M.Roem. leaves and twigs, did not show cytotoxic activity against cancer cell lines HL-60, MCF-7, SW-480, SMMC-7721, and A549, respectively. This showed that the compounds lacked potential as anticancer agents [141].

Cytotoxic activity was shown by compounds 304–309 against several cancer cell types. Specifically, compounds 304 and 308 showed efficacy against A549, MCF-7, HL-60, SMMC-7721, and SW480. Compound 305 showed activity against A549, HL-60, and SMMC-7721. In comparison to HL-60, compound 307 was effective, while 309 showed efficacy in combating HL-60 and SMMC-7721. Against every cell line tested, compounds 310, 311, 312, and 108 showed no cytotoxic effect [148, 150, 151]. The Meliaceae family provides a diverse range of bioactive alkaloids and flavaglines with significant cytotoxic effects across various cancer cell lines. The SAR insights gained highlight specific structural features essential for maximizing anticancer activity, making these compounds prime candidates for further development as therapeutic agents.

5.2 Insecticidal activity

Numerous compounds from the Meliaceae family, particularly rocaglamide and its analogues, have been investigated for insecticidal properties against agriculturally significant pests. The larvicidal and growth-inhibitory activities were evaluated primarily through contact or ingestion bioassays, with effective concentration (EC50), lethal concentration (LC50), and lethal dose (LD50) reported as outcome measures. Initial screening of piriferinol (75), edulimide (76), and cyclorocaglamide (114) against Spodoptera littoralis showed no activity, with LC50 and EC50 values exceeding 250 µg/g fresh weight [74, 163]. The efficacy of rocaglamide (115) and aglaroxins A (135), B (138), F (139), D (140), E (118), C (146), G (147), H (148), I (149), K (163), L (167), J (169) was evaluated against four insect species, namely Heliothis virescens, Spodoptera littoralis, Plutella xylostella, and Diabrotica balteata. The rocaglamide compound 115 showed high efficacy with an effective dose of 3 mg/L against all species. However, there was the exception of Heliothis virescens at the L3 larval stage, where the effective dose was 12.5 mg/L. This compound also showed significant insecticidal activity in Peridroma saucia (EC50 = 0.91 ppm; LD50 = 0.28 ppm) [36].

Among the aglaroxins, aglaroxin A (135) stood out, with effective doses of 0.8 mg/L against early and late instar H. virescens, and 3 mg/L against S. littoralis, P. xylostella, and D. balteata. For H. virescens and S. littoralis at the L3 stage, 12.5 mg/L was required. Aglaroxin B (138) displayed moderate efficacy: 3 mg/L was effective against H. virescens (e/l and L1 stages), and 12.5 mg/L was needed against S. littoralis (L3 stage). However, minimal effect was seen against P. xylostella (12.5 mg/L) and no activity against D. balteata even at > 100 mg/L [37].

Aglaroxin E (117) showed comparable activity to aglaroxin B (138) against Heliothis virescens and Spodoptera littoralis but had enhanced efficacy against Plutella xylostella. There was no significant effect against Diabrotica balteata at doses exceeding 100 mg/L. Notably, compounds 117 and 135 showed insecticidal activity against Spodoptera littoralis (LC50 = 1.0 ± 0.35 ppm; EC50 = 0.09 ± 0.03 ppm). In contrast, aglaroxin F (139) required higher doses (25–50 mg/L) for efficacy against H. virescens, S. littoralis, and P. xylostella, but was more potent against D. balteata (12.5 mg/L). Aglaroxin C (146) was moderately active (3 mg/L) against H. virescens at early stages, with reduced efficacy at later stages and poor activity (> 100 mg/L) against S. littoralis (L3). Activity against P. xylostella was moderate (12.5 mg/L), with no significant effect on D. balteata. Further screening of aglaroxins D (140), G (147), H (148), I (149), J (169), K (163), and L (167) showed minimal activity or were ineffective at doses exceeding 100 mg/L. These compounds were found to be effective against almost all species and larval stages tested. Compound 147 showed efficacy against Diabrotica balteata at a dose of 50 mg/L and 149 was active at 12.5 mg/L [37].

Rocaglamide D (116) had less insecticidal activity against Spodoptera littoralis with LC50 1.5 ± 0.65, EC50 0.21 ± 0.08 ppm than 117 (LC50 = 1.0 ± 0.35; EC50 = 0.09 ± 0.03 ppm), as compared to the positive control azadirachtin with LC50 and EC50 value of 0.9 ± 035 and 0.04 ± 038 ppm, respectively [38], while 120 and 123 were nonactive [105]. Compound 121 was active against Peridroma saucia (LD50 = 1.06 ppm; EC50 = 2.01 ppm) [36] and Spodoptera littoralis (LC50 = 1.3 ppm; EC50 = 0.27 ppm) [104]. When Spodoptera littoralis was evaluated with compounds 118, 119, and 122, the results showed LC50 values of 7.1, 8.0, and 8.1 ppm, respectively [104, 110]. The decrease in insecticidal activity can be attributed to the presence of an OCOCH3 group at C-1, with similar results also demonstrated in studies of other rocaglamide derivatives isolated from Aglaia elliptica [103, 110]. Further structure–activity insights emerged with compounds 129, 131, and 141 were evaluated against Spodoptera littoralis, showing good activity with LC50 = 1.6 ± 0.55, 1.97, and 1.6 ppm, EC50 = 0.21 ± 0.07, 0.14, and 0.4 ppm [38, 105]. Compared to the three previous compounds, 153 against Spodoptera littoralis showed a smaller LC50 value of 6.52 ppm [164].