Review on NMR spectroscopic data and recent analytical methods of aristolochic acids and derivatives in Aristolochia herbs

Abstract

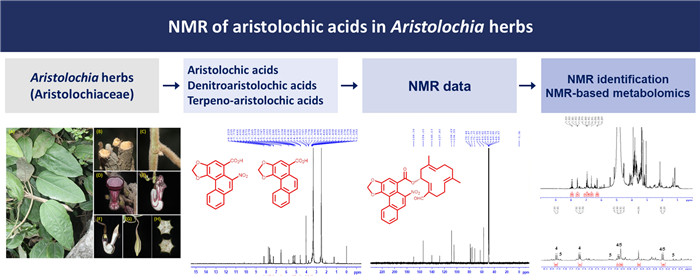

Aristolochic acids (AAs) are an important group of secondary metabolites in the genus Aristolochia. The presence of aristolochic acids infers the potency of many Aristolochia herbs used for ages in traditional medicine of China, Europe, Central America, India, and some other countries. Although being moderately cytotoxic, intake of AAs is associated with serious health problems, such as nephrotoxicity and carcinogenicity. Analyzing AAs in Aristolochia herbs is crucial for regulating their efficacy and toxicity because phytochemistry works have shown the occurrence of AAs in almost all Aristolochia herbs studied. Using two-dimensional parameters, chemical shifts and coupling constants, NMR spectroscopy is a modern, accurate, and reliable method in the analysis of secondary metabolites. Comparing experimental spectroscopic data with those of known and related compounds helps simplify the structural identification of secondary metabolites. The compilation of an NMR database of AAs from scattered sources would also be useful in NMR-based metabolomics. The present review provides updated information on sources and NMR spectroscopic data of 54 aristolochic acid derivatives, including AAs and their methyl esters, denitroaristolochic acids and their derivatives, and sesqui- and diterpene esters of AAs. The report also covers the newest development of analytical and preparative methods used in separation, identification, and quantification of AAs in Aristolochia herbal samples.Graphical Abstract

Keywords

Aristolochia Aristolochiaceae Aristolochic acid (AA) Denitroaristolochic acid LC analysis NMR data1 Introduction

The genus Aristolochia comprises more than 500 plant species that grow in wide areas, from tropics to temperate zones. For a long time, members of the genus have been in records for medicinal use in Europe, Asia, Africa, and Central America [1, 2]. Certain Aristolochia species have a long tradition to be used in China as popular medicaments in obstetrics, in the treatment of festering wounds, asthma, inflammation, and tumors, and as anodynes, expectorants, and tonics [1, 3–11]. A thorough review published in 2004 lists traditional/folkore medicinal uses of 35 Aristolochia species [12]. More than sixty species of Aristolochia species have been the subjects of phytochemical and pharmacological studies over the past 70 years [12]. Various types of compounds have been reported from the isolation works, and aristolochic acids (AAs), aristolactams, alkaloids (aporphines, tetrahydroisoquinolines, benzylisoquinolines, and bisbenzyliso-quinolines), terpenoids, lignoids, flavonoids (flavones, dihydroflavonols, isoflavonols, biflavones, chalcone-flavones, and tetraflavonoids), coumarins, and quinones are the most common types of compounds [12, 13].

Aristolochic acids are naturally occurring nitrophenanthrenic compounds in Aristolochia species of the family Aristolochiaceae, with aristolochic acids Ⅰ and Ⅱ usually being the most abundant. In 2014, the chemistry, biosynthesis, and pharmacology of AAs were reviewed [14]. The only source of these substances is the plant itself, and there is currently no large-scale method to efficiently synthesize AAs [15]. The interest in AAs is linked with their possible development into immunostimulants and anticancer agents [16]. Aristolochic acids have been experimentally and clinically demonstrated to be one of the most bioactive constituents of Aristolochia herbs, however, the toxicity of these compounds must be understood. Aristolochic acids Ⅰ and Ⅱ are the main risk factors for nephropathy and mutagenicity during chronic use of Aristolochia herbs for the treatment of rheumatism, diuretics, and analgesics [17]. Intracellular depletion of GSH by aristolochic acid Ⅰ and long metabolism of aristolochic acids into active intermediates during the detoxification process are the postulated mechanisms for the toxicity [14, 18–20]. In vivo, AAs contribute to the formation of adducts with DNA that result in DNA mutations, leading to the promotion of cancer [14, 20, 21]. In addition, they are the precursors to be metabolized to toxic aristolactams, which may be responsible for the secondary toxicity of Aristolochia herbs. Aristolochic acids are also the hypothetical precursors of naturally occurring tariacuripyrones (5-nitro-benzo[h]chromen-2-ones) from A. brevipes [22, 23] and aristchamics A and B from A. championii [24], whose biological activities and toxicity are not fully understood. Despite being warned on the risks associated with herbal products containing aristolochic acids by reputable official organizations such as the FDA (USA Food and Drug Administration), the WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer, and the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), many websites continue to recommend Aristolochia herbal products [25]. Before new regulations to control the safety of these health botanical products may be implemented, more research is needed to ascertain the presence and amounts of AAs in Aristolochia plants and to investigate the structure–activity/toxicity relationship between structures of AAs and their curative as well as toxic effects. Several studies pointed out the nitro group as a structural requirement for cytotoxicity of AAs, and the presence or absence of methoxy or hydroxyl groups may mediate cytotoxicicty [14, 26]. It is consistent with the emphasized role of the nitro group in metabolic conversion into harmful intermediates. Moreover, the toxicity rises with the increased number of methoxy groups [14].

Most of the reviews on NMR data of AAs were published prior to 1990. In 1982, 1984, and 1989, the 1H-NMR spectroscopic data of AA Ⅰa, AA Ⅰ (AA A, aristolochic acid), and AA D (AA Ⅳa) [27] and 13C-NMR spectroscopic data of some natural (AA Ⅰ, AA Ⅰa, AA Ⅱ, AA Ⅲ, AA Ⅲa, AA Ⅳ, AA Ⅳa, AA Ⅴa, aristolic acid and its methyl ester) and synthetic phenanthrene derivatives have been reviewed [27–29]. The 13C-NMR data of ent-kauranyl aristlochates, aristolin, aristolin Ⅰ from A. elegans, and aristolin Ⅱ from A. pubescens were reported [13]. Recently, more AA derivatives have been isolated and assigned with 1H- and 13C-NMR techniques, but their spectroscopic data are scattered in the literature. The application of NMR is still valid in the identification of AAs in Aristolochia and other plant species, either by isolation or by using NMR-based metabolomics techniques [30]. The aim of the present review is to compile an up-to-date list of NMR spectroscopic data of AAs and their derivatives. In addition, published LC and NMR analytical approaches in the analysis of AAs have been reviewed from the current literature.

2 Occurrence of aristolochic acids and their derivatives

According to their structural features, compounds discussed in this review form three characteristic groups: AA derivatives, denitroaristolochic acid derivatives, and sesqui- and diterpene esters of AAs.

2.1 Aristolochic acids, their sodium salts, and their methyl esters

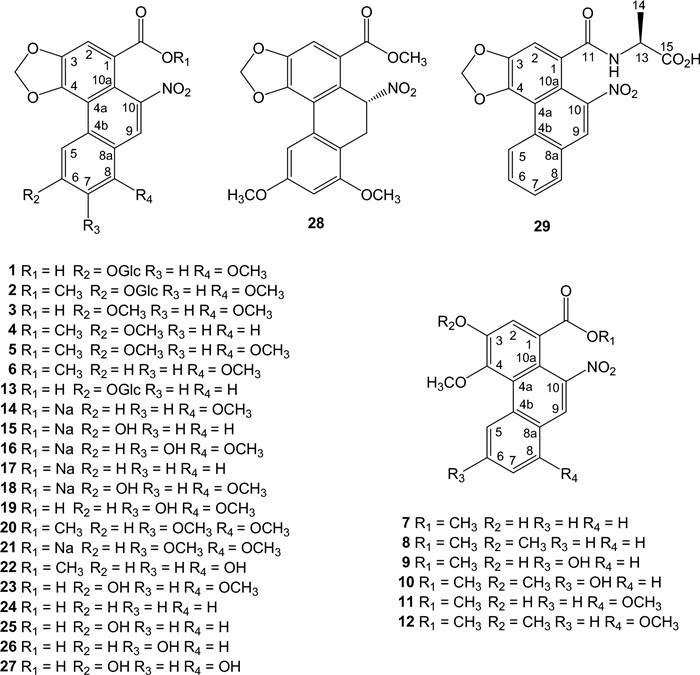

Aristolochic acid derivatives isolated from Aristolochia species are listed in chronological order (Fig. 1). Aristoloside (1) was isolated from the stems of A. manshuriensis [31] and its semisynthetic methyl ester (2), AA Ⅲ, AA Ⅳ (3), and AA Ⅲ methyl ester (4) from the root of A. longa [32] and from the root and stems of A. cucurbitifolia [33]; AA Ⅳ methyl ester (5) was synthesized from 3 using diazomethane in excess [32], methyl aristolochate (6) from the root of A. indica [34], 3-hydroxy-4-methoxy-10-nitrophenanthrene-1-carboxylic acid methyl ester (methyl ester of 3-hydroxy-4-methoxy equivalent of AA Ⅱ) (7) from the stems of A. liukiuensis (syn. A. kaempferi) [35] and the root of A. auricularia [16], ariskanins A-E (8-12) from the root and stems of A. kankauensis [36], AA Ⅲa 6-O-β-D-glucoside (13) from the root of A. cinnabarina [37], sodium aristolochate-Ⅰ (14), sodium aristolochate-C (sodium aristolochate Ⅲa) (15), and sodium 7-hydroxyaristolochate A (16) from the leaves of A. foveolata [38], sodium aristolochate Ⅰ (14), sodium aristolochate Ⅱ (17), sodium aristolochate Ⅲa (15), sodium aristolochate Ⅳa (18), and AA Ⅶa (19) from the tubercula of A. pubescens [39], aristolochic acid-Ⅶ methyl ester (20) from the fresh leaves of A. cucurbitifolia [40], sodium aristolochate (14) and sodium aristolochate-Ⅶ (21) from the root and stems of A. heterophylla [41], AA-Ⅰa methyl ester (22) from the root and stems of A. kaempferi [42], AA-D (AA Ⅳa) (23) from the leaves and stems of A. bracteolata [43], AAs B, C, F, and G (24-27) from the root of A. fangchi [17], aristchamic A (28) from the rhizomes of A. championii [24], AA Ⅱ (24) and AA Ⅶa (19) from the roots of A. contorta [18], and AA Ⅱ alanine amide (29) from the whole plant of A. maurorum [44].

Structures of aristolochic acid derivatives

The substitution of aromatic carbons from C-5 to C-8 of the C-ring of the phenanthrene nucleus may greatly influence the cytotoxicity of AAs. The most cytotoxic is aristolochic acid Ⅰ with an 8-OMe substituent, followed by aristolochic acid Ⅱ (unsubstituted), whereas aristolochic acid Ⅲ (6-OMe) is nontoxic [19]. The cytotoxic potency of AA Ⅰ is significantly reduced when the 9-hydroxy group is introduced [26]. A reducing trend of cytotoxicity is also observed with 6-hydroxy, 7-hydroxy, and 6,8-dihydroxy substitution [17, 18].

2.2 Denitroaristolochic acids, their sodium salts, and their methyl esters

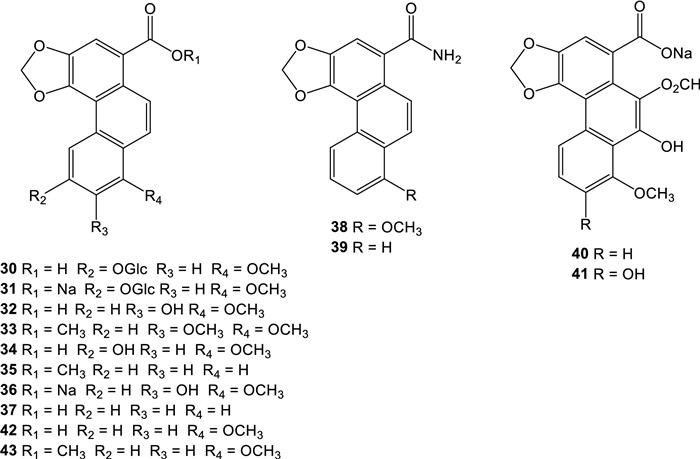

Aristofolin-A (30) were isolated from the flower of A. kaempferi [45], sodium aristofolin-A (31), aristofolins B, C, and D (32-34) from the leaves of A. cucurbitifolia [46], aristofolin-E (35) from the stem and root of A. kaempferi [42], and sodium 7-hydroxy-8-methoxyaristolate (36) from the root and stem of A. cucurbitifolia [33], demethylaristofolin E (37) from the stem of A. manshuriensis [47], aristolamide (38) from the roots of A. indica [48] and aristolamide Ⅱ (39) from the stem of A. manshuriensis [49], sodium 9-hydroxy-10-formyloxy aristolochate Ⅰ (40) and sodium 7,9-dihydroxy-10-formyloxy aristolochate Ⅰ (41) from the roots of A. contorta [18] (Fig. 2). We have updated the 1H-NMR spectroscopic data of aristolic acid (42) and its methyl ester (43), using the experimental data of the corresponding compounds isolated from the Taiwanese butterfly Pachliopta aristolochiae interpositus, which exclusively feeds on A. cucurbitifolia [50] and the synthetic products [19, 51]. Biogenetically, the nitro group of aristolochic acids can be replaced by hydrogen in a reaction called hydrogenolysis. Experimentally, Priestap et al. showed evidence for a conversion of aristolochic acid Ⅰ into aristolic acid on treatment with cysteine or GSH (glutathione) under physiological conditions [19]. Hydrogenolysis may involve the direct transfer of a hydride ion from the thiol group to eliminate the nitro group at C-10 of aristolochic acid Ⅰ, leading to the denitro derivative.

Structures of denitroaristolochic acid derivatives

Not much information is available about the cytotoxicity of derivatives of aritolic acids. In a few cases when the cytotoxicity of aristolic acid Ⅱ and aristolic acid is correlated with that of the corresponding AAs, the loss of the nitro group significantly reduces the cytotoxicity of the denitro derivatives of AAs [14].

2.3 Sesqui- and diterpene esters of aristolochic acids

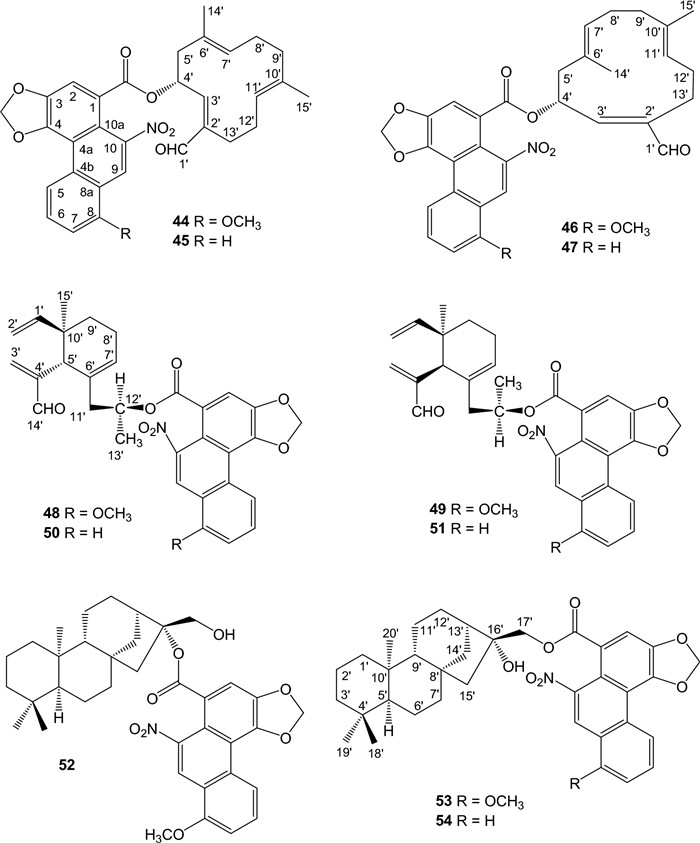

Hybrid structures of sesquiterpene ester of AAs, including aristoloterpenates Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, and Ⅳ (44-47) [52] and aristophyllides A, B, C, and D (48-51) [53], were isolated from the root and stem of A. heterophylla. ent-Kaurane diterpene esters of aristolochic acids, aristolin (52) and aristoloins Ⅰ (16α-hydroxy-ent-17-kauranyl aristolochate Ⅰ) (53) and Ⅱ (16α-hydroxy-ent-17-kauranyl aristolochate Ⅱ) (54), were isolated from the root and stem of A. elegans [54] and the tubercula of A. pubescens [39], respectively (Fig. 3).

Structures of sesqui- and diterpene esters of aristolochic acids

3 Analytical and preparative separation of aristolochic acids

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with a photodiode array (PDA) detector is considered one of the most reliable techniques for the analysis of substances with small quantities in biological samples. As the causative agents of nephropathy, analytical HPLC methods have been developed for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of AAs Ⅰ and Ⅱ in Aristolochia herbs. The analysis of other AAs and aristolactams based on comparison of HPLC retention time often encounters the shortage problem of reference compounds. PDA detectors are often used with the UV detection wavelength set at 250, 254, or 260 nm. Quantification (w/w) was based on calibration curves, which were constructed by plotting area vs. concentration. In general, simple, rapid, and accurate HPLC methods were developed to enable the simultaneous identification of AAs. Aristolochic acids have been found in almost all the Aristolochia samples analyzed in these HPLC studies, and the content of aristolochic acid Ⅰ is usually higher than that of aristolochic acid Ⅱ. To our surprise, hardly over twenty Aristolochia species have been found to contain AAs, making the development and validation of the HPLC analytical methods practically crucial [1].

Hashimoto et al. used HPLC with a Waters ODS column and MeOH-1% acetic acid (50:50, v/v) elution to examine AAs Ⅰ and Ⅱ in A. debilis, A. fangchi, and A. manshuriensis. The quantitative results showed the levels of AAs Ⅰ and Ⅱ in A. manshuriensis were higher than the non-toxic effect level established at 0.2 mg/kg [55]. The amounts of AAs Ⅰ and Ⅱ in the different parts (root, stem, leaves, fruit) of A. clematitis were quantified by Bartha et al. [56]. AAs Ⅰ and Ⅱ were found to have the highest contents in the herb's root. Using a non-acidic methanol–water (60:40) solvent system and an ODS Hypersil C18 column, Li et al. observed a reasonable separation of AAs Ⅰ and Ⅱ in A. fangchi [57]. Many factors, such as collection region, cultivation methods, and parts of the plants, can affect the contents of AAs. Alali et al. used a HPLC LichroCART® 125–4 column and a MeOH-1% acetic acid (60:40, v/v) solvent system to identify AAs Ⅰ and Ⅱ in root, stem, and leaves of A. maurorum [58]. The analytical samples were extracted in these experiments using a mixture of 80% MeOH and 20% formic acid in water. Because the parent substances contained both a carboxyl group and a nitro group, the acidic condition was considered favorable to extract AAs from plant materials. Root was found to be the main storage of the two AAs during the flowering stage. Using a C18 HPLC method with a Zobrax SB-C18 clumn, acetonitrile and 3.7 mM phosphoric acid buffer gradient elution, Zhang et al. successfully separated five AAs (aristolochic acid Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅳa, Va, and 9-hydroxyaristolochic acid-1) and two aristolactams (aristolactams Ⅰ and 2) from the fruit of A. contorta (traditional drug name in the Pharmacopoiea of the People's Republic of China: Madouling), root of A. contorta (Bei-madouling-gen), herbs of A. contorta and A. debilis (Tianxianteng), root of A. debilis (Quingmuxiang), stem of A. manshuriensis (Guanmutong), and root of A. fangchi (Guangfangji) [59]. After examining 60 samples, only AAs Ⅰ and Ⅱ were detected in the root and herbs of A. debilis, while AAs Ⅰ, Ⅱ, and Ⅳa were identified in the root of A. fangchi and the stem of A. manshuriensis. All seven compounds were found in the fruit and herbs of A. contorta, with the exception of aristolactam-Ⅱ, which was absent from the herbs of A. contorta. Furthermore, the findings demonstrated that the majority of Aristolochia herbs in China and Japan had a significantly higher amount of aristolochic acid Ⅰ than aristolochic acid Ⅱ. Using an HPLC method with a Waters C-18 HPLC column, MeOH-1% acetic acid (60:40, v/v), and UV detection at 250 nm, Abdelgadir et al. quantified the amounts of AAs Ⅰ and Ⅱ in the whole plant of A. bracteata collected in Sudan as 12.98 g/kg and 49.03 g/kg, respectively [60]. This is the first report on the higher amount of aristochic acid Ⅱ than that of aristolochic acid Ⅰ; this could be due to geographic or biological diversity of the Aristolochia species studied [60]. Using an InertSustain C18 column and an isocratic solvent mixture of 0.1% acetic acid in the ratio acetonitrile–water (50:50), Araya et al. analyzed AAs Ⅰ and Ⅱ in the leaves of A. chilensis [61]. To confirm the identification of AAs, each HPLC signal was collected and directly injected into an Orbitrap mass detector; the resulting mass spectra were compared with those of the commercial samples. Rodríguez et al. used ethyl acetate to extract AAs from leaves and stems of A. sprucei. They used a Supelco™ LC18 column with a photodiode array detector monitored at 254 nm and a solvent gradient of 10–66% MeOH in water for the first 32 min, followed by 66–10% MeOH for the next 32–35 min, and 100% MeOH for the time left, to analyze the crude extracts [62]. Aristolochic acid Ⅰ was identified in the stem extract, but not in the leaf extract of A. sprucei. The chromatographic condition showed the distinct separation of aristolochic acid Ⅰ from the other compounds in the extracts.

Metabolomics techniques based on LC–ESI–MS and 1H-NMR spectroscopy are also used to ascertain the variation of AAs and their derivatives. Michl et al. were able to screen aristolochic acid analogues in 43 medicinally used Aristolochia species using this method [30]. Metabolomics data processing involves AMIX software for the 1H-NMR spectra in the range 0.1–10 ppm and Mzmine 2 for peak extraction, chromatogram deconvolution, and peak alignment in the HR LC–MS data. While most of the compounds were tentatively assigned based on LC–MS accurate mass, retention times, UV maxima, MS/MS fragmentation ions, and 1H-NMR data set some analogues were identified by comparison with known reference standards. Consequently, a AAs Ⅰ and Ⅱ were found to be the most prevalent members, and that carbohydrates and fatty acids are the primary chemical markers that differentiate Aristolochia samples. Based on MS data libraries of Traditional Medicine Zhang et al. developed an UP (Ultra-Performance)LC-QTOF-MS/MS method using a Waters Acquity UPLC-BEH C18 column, a gradient elution of 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution-acetonitrile, and ESI–MS detection with a full scale mode ranged m/z 50–1500 [62]. Compounds were identified in three species of Aristolochia herbs, including A. mollissima, A. debilis, and A. cinnabaria, by comparing chromatographic and MS characteristics with those of four aristolochic acid standards and the published literature. To explain the qualitative and quantitative variations in the three Aristolochia herbs from different origins, the authors employed 19 differential markers of AAs and aristolatams from A. mollissima, 16 differential markers from A. debilis, and 22 differential markers from A. cinnabaria. Compared to the other species of A. mollissima and A. debilis, A. cinnabaria had much higher levels of AAs.

Capillary electrophoresis (CE) offers many advantages, such as high speed, high efficiency, ultra-small sample volume, and low consumption of solvent [63]. Coupling electrochemical detection (ED) with CE can provide high separation efficiency and good sensitivity. Zhou et al. detected AAs Ⅰ and Ⅱ in the fruit, stem, and root of A. debilis using a 33 μm carbon fiber electrode (CFE) as the working electrode for the [64]. An aqueous buffer with 2.0 × 10–2 mol L−1 phosphate buffer solution (PBS) (pH 10.0) was used to accomplish the separation. In accordance with the results of many previous analytical reports, the contents of AAs in the root are higher than those in the fruit, but abnormally, they were not detected in the stem.

The recent emphasis on qualitative and quantitative investigation of AAs in the original plants or formulations was highlighted by Zhang et al. [65]. The works require high-purity reference compounds. When using preparative liquid chromatography, the required purity of the target compounds is achieved if the distance between zones of compounds under separation increases. Using Waters Auto-purification Factory with an oligo (ethylene glycol) (OEG) separation column to cluster compounds with similar structures and preparative PDA-HPLC with a C-18 separation column to purify the target compounds the authors develop a method for selective purification of AAs from Aristolochia plants. A gradient solvent system with 0.2% formic acid water and methanol and 0.2% formic acid water and acetonitrile were used for fraction separation and compound purification, respectively. The detection wavelength was 260 nm. Aristolochic acids from A. manshuriensis were successfully separated and purified using this method. Duan et al. used an advanced counter-current chromatography (CCC) technique, called pH-zone-refining CCC (pH-ZRCCC), in preparative isolation of AAs [66]. A large-scale separation technique for organic acids and bases according to their pH in displacement mode, pH-ZRCCC was introduced in 1991. The method uses a retainer base (or acid) to hold the analytes in the column and a displacer acid (base) to elute the analytes in the decreasing order of pKa and hydrophorbicity. pH-ZRCCC has been shown to be effective in isolating target compounds from the EtOAc extract from the stem of A. manshuriensis with high purity in a single run and is not affected by irreversible adsorption. Petroleum ether-EtOAc–MeOH-water (3:7:3:7, v/v/v/v) was the optimum two-phase solvent system. Triethylamine and trifluoroacetic acid were added to the organic phase. The collection was monitored with a UV detector at 254 nm. The elution order of AAs in the chromatogram (aristolochic acid Ⅲa > aristolochic acid Ⅳa > aristolochic acid Ⅱ > aristolochic acid Ⅰ > aristolic acid Ⅱ > aristolic acid Ⅰ) was in accordance with the hydrophorbic properties of AAs and their acidities.

4 Structure elucidation of aristolochic acids and derivatives

According to the structural features of isolated AAs from the genus Aristolochia they have been grouped into the following groups: ⅰ) AAs, their sodium salts, and their methyl esters; ⅱ) denitroaristolochic acids (derivatives of aristolic acids), their sodium salts, and their methyl esters; and ⅲ) sesqui- and diterpene esters of AAs. Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 list the 1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopic data for AAs, denitroaristolochic acids, and terpene esters of AAs. The nonpolar, aprotic CDCl3 is used for NMR measurements of less polar methyl esters of AAs, denitroaristolochic acids and terpene esters of AAs, whereas the polar, aprotic DMSO-d6 is the common NMR solvent for AAs. On a smaller scale, acetone-d6 is used for methyl esters of AAs and methanol-d4 is used for polar AA derivatives, such as their glucosides or sodium salts. Due to interactions between NMR solvents and compounds, measured chemical shifts may vary for the same compounds as observed for compound 42 in DMSO-d6 and acetone-d6 (Table 8). Since typical structures of AAs are not complex, with most of the signals falling in the downfield region, the resolution of substituted aromatic C-rings from H-5 to H-8 may benefit from high-field NMR techniques. For example, the 1H-NMR data of compound 42 having an 8-methoxy substituent in DMSO-d6 are almost coincident when measured at 60 MHz [51] and 400 MHz [19]. Most of the time, 2D NMR techniques such as HSQC (or HMQC), HMBC, and COSY were used to assign the proton and carbon-13 signals.

Aristolochic acids and derivatives from Aristolochia species

1H- and 13C-NMR characteristic signals of aristolochic acid derivatives (δ in ppm, J in Hz, DMSO-d6)

1H-NMR spectroscopic data of compounds 1–7 (δ in ppm, J in Hz)

1H-NMR spectroscopic data of compounds 8–16 (δ in ppm, J in Hz)

1H-NMR spectroscopic data of compounds 19–28 (δ in ppm, J in Hz)

1H-NMR spectroscopic data of compounds 29–36 (δ in ppm, J in Hz)

13C-NMR spectroscopic data of compounds 13, 15–19, 23–29 (δ in ppm)

1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopic data of compounds 37, 39–43 (δ in ppm, J in Hz)

1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopic data of compounds 44–49 (δ in ppm, J in Hz, CDCl3)

1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopic data of compounds 50–54 (δ in ppm, J in Hz, CDCl3)

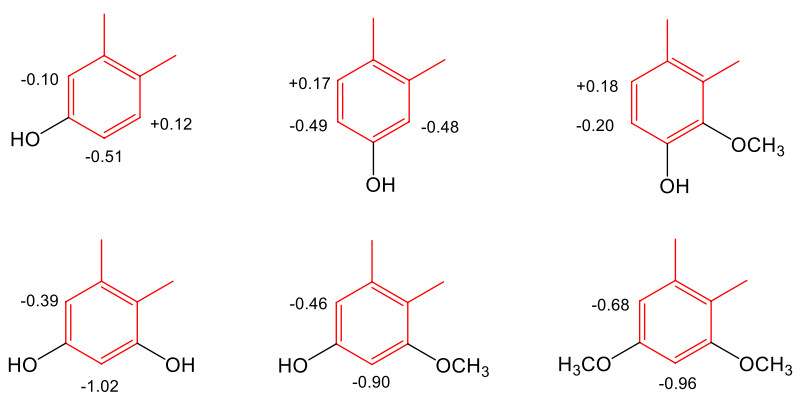

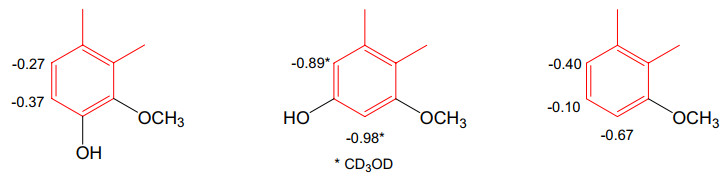

Aristolochic acids all have structures of 10-nitrophenanthrenecarboxylic acid. The majority of AAs have a 3,4-methylenedioxy group (phenanthro[3,4-d]-1,3-dioxole-10-nitro-1-carboxylic acids). In the IR spectra, the presence of the nitro group is indicated at νmax ca. 1525 and 1346 cm-1, whereas the carbonyl group absorbs in the range 1710-1600 cm-1 [38]. At C-6, C-7, or C-8, the C ring of the phenanthrene skeleton is commonly substituted with a hydroxyl or a methoxy group, resulting in monooxygenated, deoxygenated, or trioxygenated phenanthrenecarboxylic acids. To confirm the locations of the hydroxyl or methoxy substituents of the C ring, NOESY experiments can be conducted [36]. In some examples, the C-ring is unsubstituted. Taken together, the following characteristics are visible in the 1H-NMR spectra of most AAs: the singlet signals of aromatic H-2 and H-9 at δH ca 7.70-7.80 and 8.20-8.70, respectively, and the proton spin-spin splitting of aromatic H-5 and H-8 in dependency of the aromatic substitution patterns of H-6, H-7, and H-8. C-5 is unsubstituted in all instances, and the proton signal for H-5 is often shifted downfield at δH ca. 8.20-8.70 because of the shielding effect of the phenanthrene A ring. The methylenedioxy group is indicated by a two-proton singlet signal at δH ca. 6.40, δC ca. 102-104. The common derivatives of AAs are their methyl esters [16, 31–33, 35, 40, 42], which may be inferred from an additional methoxy signal at δH ca. 4.00 in their 1H-NMR spectra. Comparisons of chemical shifts of the phenanthrene C-ring of 3,4-methylenedioxyaristolochic acids can lead to some remarks about substituent effects. Glucosylation at C-6 of AA Ⅰ [17] (compound 1, Table 3) causes upfield shifts of H-5 (-0.26 ppm) and H-7 (-0.20 ppm) in DMSO-d6. The shielding effects observed for 2 are H-5 (-0.16 ppm) and H-7 (-0.34 ppm). Methoxy and hydroxy groups are common substituents of the C-rings of AAs isolated from Aristolochia plants. 6-Oxy, 7-oxy, 6,8-dioxy, and 7,8-dioxy are substitution patterns observed in the current review, and the shielding (upfield shift) or deshielding effect (downfield shift) compared with AAⅡ (24) in DMSO-d6 are summarized in Fig. 4. Occasionally, sodium aristolochates are isolated [38, 41]. Their salt form is indicated by the carboxyl group appears at νmax ca. 1540-1580 cm-1 in the IR spectra [38]. In comparison between 1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopic data of the free AAs and their sodium salts, the chemical shifts the carboxyl groups are at δC ca. 168 and C-1 at δC ca. 121-124, whereas H-9 of the sodium salts shifts upfield to δH ca. 8.15-8.35 (acids: δH ca. 8.45-8.60) [28, 29]. Treatment of the salt form with 5% HCl and the solution is purified on a Sephadex LH-20 column eluted successively with H2O and MeOH affords sodium chloride, which is determined by atomic absorption spectrometry [33, 38, 41]. The MeOH solution affords free acids, whose carbonyl group appears at νmax ca. 1660-1710 cm-1 in the IR spectra [38]. Compared to those of the free acids H-9 of the sodium salts of AAs appeared slightly upfield at δH ca 8.15-8.35 [38].

Substituent effects on C-ring of 3,4-methylenedioxyaristolochic acids

Aristolochic acids can be converted into denitro compounds by reduction, both chemically [20, 50] and biologically [19], e.g., aristolochic acid Ⅰ is converted to aristolic acid. Similar to the nitro compounds, the occurrence of denitroaristolochic acids as their methyl esters [34] or sodium salts [45] is frequently found in Aristolochia herbs. In one publication [47], primary amide derivatives of aristolic acids were isolated; the amide group was identified by an IR absorption band for a NH2 group at νmax 3182 cm-1 and a carbon-13 signal at δC 170.1. Free carboxylic acids are identified by an IR absorption band for the carboxyl group at νmax 3000 and 1670 cm-1 and a carbon-13 signal at δC ca. 168.0 [46]. The presence of the carboxyl group can be detected by D2O exchange. Al-Barham et al. reported the isolation of a secondary amide of aristolochic acid (29) [44], which has an IR absorption band for the NH group at νmax 3466 cm-1 and an amide carbon-13 signal at δC 174.5. In addition, the NH signal in the 1H-NMR spectrum appears at δC 8.97 (br s). In accordance with the structural change to phenanthrene-1-carboxylic acids, the NMR spectra of the denitro derivatives show signals of a cis-configured C-9/C-10 double bond at δH ca. 8.80 and 7.70 (J ~ 9-10 Hz) and δC ca. 124-127. Glucosylation at C-6 of aristolic acid (42) (compound 31, Table 6) causes upfield shifts of H-5 (-0.35 ppm) and H-7 (-0.28 ppm) in DMSO-d6. The shielding or deshielding effects of 8-oxy, 7,8-dioxy, and 6,8-dioxy substituents in DMSO-d6 compared with aristolic acid (42) are summarized in Fig. 5. Two first formyloxy derivatives of aristolic acids are reported in [18] with C-9 and C-10 substituted with a hydroxyl group and a formyloxy group, respectively. Consequently, the olefinic carbon/proton signals are not observed, instead, the formyloxy group resonances at δH ca. 8.20 and at δC ca. 162. Since the compounds occurred as their sodium salts, the cation portion was confirmed by ICP-MS.

Substituent effects on C-ring of 3,4-methylenedioxyaristolic acids

Species of Aristolochia have been reported to contain elemane, caryophyllane, and humulane [12]. Mandolin R, mandolin L, mandolin M, and arystophyllene [12], which were previously isolated from the root and stem of A. heterophylla, may be related precursors for the sesquiterpene alcohol moieties of aristolochic acid esters from Aristolochia species, however, more research is needed to identify the direct precursor compounds. ent-Kaurane diterpenoids are widely isolated from Aristolochia species, including A. elegans [12]. Epoxide ring-opening of the precursor 16,17-epoxy-ent-kaurane or by an esterification of AAs and ent-kaurane-16,17-diol may produce aristolin (52), aristoloins Ⅰ (53) and Ⅱ (54). These terpeno-aristolochic acid hybrid compounds are identified by 13C-NMR, which revealed 14 carbons for the core phenanthrene moiety, a carboxyl group, and 15 or 20 carbons for the sesqui- or diterpene moiety, respectively. Compounds 52-54 have been included as Aristolochia diterpenes in the review [13]. The HMBC correlations between the α-proton of the terpene alcohol moiety and the carbonyl group of AAs simplify the identification of the ester linkage. The ester itself exhibits an IR absorption band at νmax 1710 cm-1. However, when the ester group is located at tertiary C-16 of the ent-kaurane-16β, 17-diol [12], the upfield shifts of kaurane C-13 and C-17 (δC ca. 43.4 and 63.5 in CDCl3, respectively) are indicative for the ester location. Kaurane C-16 is anticipated to undergo a downfield shift, e.g, the carbon-13 chemical shift was at δC 98.1 for ent-kaurane C-16 of 52 [39]. Compounds 44-47 possess several chiral centers of the ent-elemane moiety. Their absolute stereostructures were determined by using the CD (Circular Dichroism) exciton chirality method [52]. The experimental positive and negative Cotton effects were compared with the chiral exciton couplings between the cyclohexene double bond and the unsaturated aldehyde chromophore (at ca. 220 nm) and between the ring double bond and the 3,4-methylenedioxybenzoate chromophore (at ca. 260 nm). The 13C-NMR of compounds 45 and 47 could not be achieved due to small amounts of the isolated samples [52].

5 Conclusion

More aristolochic acid derivatives have been isolated and reported since the early assessment of a few reviews on NMR spectroscopic data of common Aristolochia phenenthrene derivatives [27–29]. This review provides an update list of NMR spectroscopic data of AAs isolated from Aristolochia herbs. The NMR characteristics of three classes of derivatives, AAs, denitroaristolochic acids, and esters of AAs, are also been briefly discussed. By comparing NMR data, the data would facilitate the identification of the bioactive and toxic AAs in Arisolochia herbs. In addition, the latest development in analytical and preparative separation of AAs in Aristolochia herbs appears for the first time in the current review.

Notes

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) under Grant Number 104.01-2021.09.

Author contributions

PMG designed the study, wrote, and edited of the manuscript. DNP edited parts of the figures and tables. NNV, VTL, NDT, TPL prepared the references. TTTT read and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

-

1.Heinrich M, Chan J, Wanke S, Neinhuis C, Simmonds MSJ. Local uses of Aristolochia species and content of nephrotoxic aristolochic acid 1 and 2 – a global assessment based on bibliographic sources. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;125: 108-44. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

2.Holzbach JC, Lopes LXM. Aristolactams and alkamides of Aristolochia giganta. Molecules. 2010;15: 9462-72. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

3.Shi LS, Kuo PC, Tsai YL, Damu AG, Wu TS. The alkaloids and other constituents from the root and stem of Aristolochia elegans. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12: 439-46. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

4.Wang X, Jin M, Jin C, Sun J, Zhou W, Li G. A new sesquiterpene, a new monoterpene and other constituents with anti-inflammatory activities from the roots of Aristolochia debilis. Nat Prod Res. 2020;34: 351-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

5.Lu JZ, Wei F, Cai Y. A new aristolactam-type from the roots of Aristolochia fangchi. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2012;14: 276-80. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

6.Zhou Z, Luo J, Pan K, Kong L. A new alkaloid glycoside from the rhizomes of Aristolochia fordiana. Nat Prod Res. 2015;28: 1065-9. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

7.Jiménez-Arellanes A, León-Díaz R, Meckes M, Tapia A, Molina-Salinas GM, Luna-Herrera J, Yépez-Mulia L. Antiprotozoal and antimycobacterial activities of pure compounds from Aristolochia elegans rhizomes. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012: 593403. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

8.Desai DC, Jacob J, Almeida A, Kshirsagar R, Manju SL. Isolation, structural elucidation and anti-inflammatory activity of astragalin, (-)-hinokinin, aristolactam Ⅰ and aristolochic acids (Ⅰ & Ⅱ) from Aristolochia indica. Nat Prod Res. 2014;28: 141301417. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

9.Chen YG, Yu LL, Huang R, Liu JC, Lu YP, Zhao Y. 3″-Hydroxyamentofla-vone ant its 7-O-methyl ether, two new bioflavonoids from Aristolochia contorta. Arch Pharm Res. 2005;2025: 1233-5. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

10.Zhang G, Shimokawa S, Mochizuki M, Kumamoto T, Nakanishi W, Watanabe T, Ishikawa T, Matsumoto K, Tashima K, Horie S, Higuchi Y, Dominguez OP. Chemical constituents of Aristolochia constricta: anti-plasmodic effects of its constituents in Guinea-pig ileum and isolation of a diterpeno-lignan hybrid. J Nat Prod. 2008;71: 1167-72. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

11.Lerma-Herrera MA, Beiza-Granados L, Ochoa-Zarzosa A, López-Meza JE, Navarro-Santos P, Herrera-Bucio R, Avirna-Verduzco J, Gariciá-Gutiérrez HA. Biological activities of organic extracts of the genus Aristolochia: a review from 2005 to 2021. Molecules. 2022;27: 3937. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

12.Wu TS, Damu AG, Su CR, Kuo PC. Terpenoids of Aristolochia and their biological activities. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21: 594-624. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

13.Pacheco AG, de Oliveira PM, Piló-Veloso D, Alcântara AFC. 13C-NMR data of diterpenes isolated from Aristolochia species. Molecules. 2009;14: 1245-62. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

14.Michl J, Ingrouille MJ, Simmonds MSJ, Heinrich M. Naturally occurring aristolochic acid analogues and their toxicities. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31: 676-93. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

15.Attaluri S, Iden CR, Bonala RR, Johnson F. Total synthesis of aristolochic acids, their major metabolites, and related compounds. Chem Res Toxicol. 2014;27: 1236-42. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

16.Houghton PJ, Ogutveren M. Aristolochic acids and aristolactams from Aristolochia auricularia. Phytochemistry. 1991;30: 253-4. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

17.Cai Y, Cai TG. Two new aristolochic acid derivatives from the roots of Aristolochia fangchi and their cytotoxicities. Chem Pharm Bull. 2010;58: 1093-5. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

18.Ji HJ, Li JY, Wu SF, Wu WY, Yao CL, Yao S, Zhang JQ, Guo DA. Two new aristolochic acid analogues from the roots of Aristolochia contorta with significant cytotoxic activity. Molecules. 2021;26: 44. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

19.Priestap HA, Barbieri MA. Conversion of aristolochic acid Ⅰ into aristolic acid by reaction with cysteine and glutathione: biological implications. J Nat Prod. 2013;76: 965-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

20.Priestap HA, de Santos C, Quirke JM. Identification of a reduction product of aristolochic acid: implication for the metabolic activation of carcinogenic aristolochic acid. J Nat Prod. 2010;73: 1979-86. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

21.Krell D, Stebbing J. Aristolochia: the malignant truth. Lancet. 2013;14: 25-6. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

22.Achenbach H, Waibel R, Zwanzger M. 9-Methoxy- and 7,9-dimethoxy-tariacuripyrone, natural nitro-compounds with a new basic skeleton from Aristolochia brevipes. J Nat Prod. 1992;55: 918-22. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

23.Schimmer O, Drewello U. 9-Methoxytariacuripyrone, a naturally occurring nitro-aromatic compound with strong mutagenicity in Salmonella typhimurium. Mutagenesis. 1994;9: 547-51. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

24.Wang X, Shi GR, Liu YF, Li L, Chen RY, Yu DQ. Aristolochic acid derivatives from the rhizome of Aristolochia championii. Fitoterapia. 2017;118: 63-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

25.Maggini V, Menniti-Ippolito F, Firenzuoli F. Aristolochia, a nephrotoxic herb, still surfs on the Web, 15 years later. Intern Emerg Med. 2018. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

26.Wen YJ, Su T, Tang JW, Zhang CY, Wang X, Cai SQ, Li XM. Cytotoxicity of phenanthrenes extracted from Aristolochia contorta in human proximal tubular epithelial cell line. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2006;103: e95. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

27.Mix DB, Guinaudeau H, Shamma M. The aristolochic acids and aristolactams. J Nat Prod. 1982;45: 657-66. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

28.Achari B, Bandyopadhyay S, Chakravarty AK, Pakrashi SC. Carbon 13C NMR spectra of some phenanthrene derivatives from Aristolochia indica and their analogues. Org Magn Reson. 1984;22: 741-6. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

29.Priestap HA. 13C NMR spectroscopy of aristolochic acids and aristololactams. Mag Res Chem. 1989;27: 460-9. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

30.Michl J, Kite GC, Wanke S, Zierau O, Vollmer G, Neinhuis C, Simmonds MSJ, Heinrich M. LC-MS- and 1H NMR-based metabolomic analysis and in vitro toxicological assessment of 43 Aristolochia species. J Nat Prod. 2016;9: 30-7. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

31.Nakanishi T, Iwasaki K, Nasu M, Miura I, Yoneda K. Aristoloside, an aristolochic acid derivative from stems of Aristolochia manshuriensis. Phytochemistry. 1981;21: 1759-62. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

32.De P, Teresa J, Urones JG, Fernandez A. An aristolochic acid derivative from Aristolochia longa. Phytochemistry. 1983;22: 2745-7. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

33.Wu TS, Chan YY, Leu YL. The constituents of the root and stem of Aristolochia cucurbitifolia Hayata and their biological activity. Chem Pharm Bull. 2000;48: 1006-9. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

34.Che CT, Ahmed MS, Kang SS, Waller DP, Bingel AS, Martin A, Rajamahendran P, Bunyapraphatsara N, Lankin DC, Cordell GA, Soejarto DD, Wijesekera ROB, Fong HHS. Studies on Aristolochia Ⅲ Isolation and biological evaluation of constituents of Aristolochia indica roots for fertility-regulating activity. J Nat Prod. 1984;47: 331-41. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

35.Mizuno M, Oka M, Iinuma M, Tanaka T. An aristolochic acid derivative of Aristolochica liukiuensis. J Nat Prod. 1990;53: 179-81. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

36.Wu TS, Ou LF, Teng CM. Aristolochic acids, aristolactam alkaloids and amides from Aristolochia kankauensis. Phytochemistry. 1994;36: 1063-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

37.Hong L, Sakagami Y, Marumo S, Xinmin C. Eleven aristolochic acid derivatives from Aristolochia cinnabarina. Phytochemistry. 1994;37: 237-9. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

38.Leu YL, Chan YY, Wu TS. Sodium aristolochate derivatives from leaves of Aristolochia foveolata. Phytochemistry. 1998;48: 743-5. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

39.Nascimento IR, Lopes LMX. Diterpene etsers of aristolochic acids from Aristolochia pubescens. Phytochemistry. 2003;63: 953-7. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

40.Wu TS, Leu YL, Chan YY. Constituents of the fresh leaves of Aristolochia cucurbitifolia. Chem Pharm Bull. 1999;47: 571-3. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

41.Wu TS, Chan YY, Leu YL. The constituents of the root and stem of Aristolochia heterophylla Hemsl. Chem Pharm Bull. 2000;48: 357-61. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

42.Wu TS, Leu YL, Chan YY. Constituents from the stem and root of Aristolochia kaempferi. Biol Pharm Bull. 2000;23: 1216-9. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

43.Al-Busafi S, Al-Harthi M, Al-Sabahi B. Isolation of aristolochic acids from Aristolochia bracteolata and studies of their antioxidant activities. SQU J Sci. 2004;9: 19-23. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

44.Al-Barham MB, Al-Jaber HI, Al-Qudah MA, Abu Zarga MH. New aristolochic acid and other chemical constituents of Aristolochia maurorum growing wild in Jordan. Nat Prod Res. 2017;31: 245-52. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

45.Wu TS, Leu YL, Chan YY. Aristofolin-A, a denitro-aristolochic acid glycoside and other constituents form Aristolochia kaempferi. Phytochemistry. 1998;49: 2509-10. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

46.Wu TS, Leu YL, Chan YY. Denitroaristolochic acids from the leaves of Aristolochia cucurbitifolia. Chem Pharm Bull. 1998;46: 1301-2. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

47.Wu PL, Su GC, Wu TS. Constituents from the stems of Aristolochia manshuriensis. J Nat Prod. 2003;66: 996-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

48.Pakrashi SC, Ghosh-Dastidar P, Basu S, Achari B. New phenanthrene derivatives from Aristolochia indica. Phytochemistry. 1977;16: 1103-4. PubMed Google Scholar

-

49.Chung YM, Chang FR, Tseng TF, Hwang TL, Chen LC, Wu SF, Lee CL, Lin ZY, Chuang LY, Su JH, Wu YC. A novel alkaloid, aristopyridinone A and anti-inflammatory phenanthrenes isolated from Aristolochia manshuriensis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21: 1792-4. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

50.Wu TS, Leu YL, Chan YY. Aristolochic acids as a defentive substance for the Aristolochiaceous plant-feeding swallowtail butterfly, Pachliopta aristolochiae interpositus. J Chin Chem Soc. 2000;47: 221-6. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

51.Mukhopadhyay S, Funayama S, Cordell GA, Fong HHS. Studies on Aristolochia, I. Conversion of aristolochic acid-Ⅰ to aristolic acid-one step removal of a nitro group. J Nat Prod. 1983;46: 507-9. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

52.Wu TS, Chan YY, Leu YL, Chen ZT. Sesquiterpene esters of aristolochic acid from the root and stem of Aristolochia heterophylla. J Nat Prod. 1999;62: 415-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

53.Wu TS, Chan YY, Leu YL, Wu PL, Li CY, Mori Y. Four aristolochic acid ester of rearranged ent-elemane sesquiterpenes from Aristolochia heterophylla. J Nat Prod. 1999;6: 348-51. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

54.Wu TS, Tsai YL, Damu AG, Kuo PC, Wu PL. Constituents form the root and stem of Aristolochia elegans. J Nat Prod. 2002;65: 1522-5. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

55.Hashimoto K, Higuchi M, Makino B, Sakakibara I, Kubo M, Komatsu Y, Maruno M, Okada M. Quantitative analysis of aristolochic acids, toxic compounds, contained in some medicinal plants. J Ethnopharm. 1999;64: 185-9. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

56.Bartha GS, Tóth G, Horváth P, Kiss E, Papp N, Kerényi M. Analysis of aristolochic acids and evaluation of antibacterial activity of Aristolochia clematitis L. Biol Futura. 2019;70: 323-9. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

57.Li W, Li R, Bo T, Liu H, Feng X, Hu S. Rapid determination of aristolochic acids Ⅰ and Ⅱ in some medicinal plants by high-perfomance liquid chromatography. Chromatographia. 2004;59: 233-6. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

58.Alali FO, Tawaha K, Shehadeh MB, Telfah S. Phytochemical and biological investigation of Aristolochia maurorum L. Z Naturforsch. 2006;2006: 685-91. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

59.Zhang C, Wang X, Shang M, Yu J, Xu Y, Li Z, Lei L, Li X, Cai S, Namba T. Simultaneous determination of five aristolochic acids and two aristolactmas in Aristolochia plants by high-perfomance liquid chromatography. Biomed Chromatogr. 2006;20: 309-18. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

60.Abdelgadir AA, Ahmed EM, Eltohami MS. Isolation, characterization and quality determination of aritolochic acids, toxic compounds in Aristolochia bracteolata L. Environ Health Insights. 2011;5: 1-8. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

61.Araya M, García S, Gonzaslez-Teuber M. Rapid identification and simultaneous quantification of aristolochic acids by HPLC-DAD and confirmation by MS in Aristolochia chilensis using a limited biomass. J Anal Methods Chem. 2018;2018: 5036542. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

62.Rodríguez ⅡG, Francisco AF, Moreira-Drill LS, Quintero A, Guimarães CLS, Fernandes CAH, Takeda AAS, Zanchi FB, Caldeira CAS, Pereira PS, Fontes MRM, Zuliani JP, Soares AM. Isolation and structural characterization of bioactive compound from Aristolochia spruce aqueous extract with anti-myotic activity. Toxicon: X. 2020;2020: 100049. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

63.Zhang SH, Wang Y, Yang J, Zhang DD, Wang YL, Li SH, Pan YN, Zhang HM, Sun Y. Comparative analysis of aristolochic acids in Aristolochia medicinal herbs and evaluation of their toxicities. Toxins. 2022;14: 879. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

64.Zhou X, Zheng C, Sun J, You T. Analysis of nephroloxic and carcinogenic aristolochic acids in Aristolochia plants by capillary electrophoresis with electrochemical detection at a carbon fiber microdisk electrode. J Chromatg A. 2006;1109: 152-9. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

65.Zhang J, Xiao Y, Feng J, Wu SL, Xue X, Zhang X, Liang X. Selective preparative purification of aristolochic acids and aristolactams from Aristolochia plants. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2010;52: 446-51. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

66.Duan W, Li Y, Dong H, Yang G, Wang W, Wang X. Isolation and purification of six aristolochic acids with similar structures from Aristolochia manshuriensis Kom stems by pH-zone-refining counter-current chromatography. J Chromatog A. 2020;1613: 460657. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© The Author(s) 2025

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.