The genus Rumex (Polygonaceae): an ethnobotanical, phytochemical and pharmacological review

Abstract

Rumex L., a genus in Polygonaceae family with about 200 species, is growing widely around the world. Some Rumex species, called "sorrel" or "dock", have been used as food application and treatment of skin diseases and hemostasis after trauma by the local people of its growing areas for centuries. To date, 29 Rumex species have been studied to contain about 268 substances, including anthraquinones, flavonoids, naphthalenes, stilbenes, diterpene alkaloids, terpenes, lignans, and tannins. Crude extract of Rumex spp. and the pure isolates displayed various bioactivities, such as antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, antioxidant, cardiovascular protection and antiaging activities. Rumex species have important potential to become a clinical medicinal source in future. This review covers research articles from 1900 to 2022, fetched from SciFinder, Web of Science, ResearchGate, CNKI and Google Scholar, using "Rumex" as a search term ("all fields") with no specific time frame set for the search. Thirty-five Rumex species were selected and summarized on their geographical distribution, edible parts, traditional uses, chemical research and pharmacological properties.Keywords

Polygonaceae Rumex L. Anthraquinones Phenolics Pharmacological properties1 Introduction

Rumex L., the second largest genus in the family Polygonaceae, with more than 200 species, is mainly distributed in the northern temperate zone [1]. It is mostly perennial herbs with sturdy roots, paniculate inflorescences, and triangular fruits that are enveloped in the enlarged inner perianth. The name "Rumex" originated from the Greek word–"dart" or "spear", alluding to the shape of leaves [2]. The other explanation from Rome–"rums" alludes to the function that the leaves could be sucked to alleviate thirst [3]. R. acetosa, a typical vegetable and medicinal plant, whose name 'acetosa' originated from the Latin word "acetum", described the taste of the plant as vinegar. Currently, many oxalic acids have been reported from Rumex, verifying its sour tastes [4].

Rumex species have had a valued place as global folk medicine, e.g., in Southern Africa, America, India, China, and Turkey. The earliest medicinal record of Rumex spp. in China was in "Shennong's Herbal Classic", in which Rumex was recorded for the treatment of headed, scabies, fever, and gynecological diseases. Roots of Rumex, also called dock root, have been reported for its therapeutic capacity of bacterial infections, inflammatory, tumor and cardiovascular diseases [5, 6]. Recently, pharmacological study showed that Rumex species displayed apparent antibacterial and antifungal effects [7], and were employed in the management of skin scabies and inflammation [8, 9]. The processed Rumex exhibited different chemical profiles and bioactivities [10, 11]. Leaves, flowers and seeds of some Rumex plants are edible as vegetables, while in some regions, the Rumex plants are regarded as noxious weeds because oxalic acid makes them difficult to be digested [12].

To date, 268 components from 29 Rumex species have been reported. Anthraquinones, flavonoids, tannins, stilbenes, naphthalenes, diterpene alkaloids, terpenes, and lignans were as the main chemical components, with a broad spectrum of pharmacological activities, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacteria, antitumor, and antidiabetic activities [13-17]. In addition to important role of Rumex in the traditional applications, researchers also regard Rumex as a potential effective medicine of many diseases. This article has reviewed a comprehensive knowledge on the distribution, traditional uses, chemistry and bioactivity progress of Rumex, and their therapeutic applications and utilizations were provided.

2 Geographical distributions, local names, parts used and traditional uses

The genus Rumex with more than 200 species, is distributed widely in the world and has been used traditionally in many regions, e.g., Asia, America, Europe and other continents. Many of them known as "sorrel" or "dock" have a long history of food application and medicinal uses for the treatment of skin diseases, and hemostasis after trauma by the local people of its growing areas. For example, R. acetosa is commonly used medicinally for diuretics around the world [4]. R. maritimus and R. nepalensis, used as laxatives, have long-term medicinal applications in India as substitutes for Rheum palmatum (Polygonaceae), which is usually used to regulate the whole digestive system. Moreover, Indians have also recorded nine Rumex plants as astringent agents, including R. acetosa, R. acetosella, R. crispus, R. dentatus, R. hastatus, R. maritimus, R. nepalensis, R. scutatus, and R. vesicarius [18]. All seven species included R. acetosa, R. trisetifer, R. patientia, R. crispus, R. japonicus, R. dentatus and R. nepalensis, called "jinbuhuan", have been used for hemostasis remediation in China [19]. R. thyrsiflorus, rich in nutrition, has been used as food by Europeans in history and as folk medicine due to its obvious anti-inflammatory activity [20]. R. lunaria has been used to treat diabetes by Canarian medicine [16]. The leaves of more than 14 Rumex spp., such as R. acetosa, R. hastatus, R. thyrsiflorus, R. aquaticus, R. crispus, R. gmelini, R. patientia, R. vesicarius, R. ecklonianus, R. abyssinicus, R. confertus, R. hymenosepalus, R. alpinus and R. sanguineus (Table 1) could be eaten freshly or cooked as vegetables in the folk of many places [5, 6]. In Table 1, the geographical distributions, local names, parts used and traditional uses of 35 Rumex species are summarized.

Traditional uses of Rumex plants

3 Chemical constituents

To date, 268 compounds including 56 quinones (1–56), 57 flavonoids (57–113), 25 tannins (114–138), 6 stilbenes (139–144), 22 naphthalenes (145–166), 6 terpenes (167–172), 3 diterpene alkaloids (173–175), 14 lignans (176–189) and 79 other types of components (190–268) were isolated and reported from 29 Rumex species (Table 2).

The summary of compounds in Rumex

3.1 Quinones

Quinones are widely found in Rumex, particularly accumulated in the roots. 56 quinones (Fig. 1) including anthraquinones, anthranones, and seco-anthraquinones and their glycosides and dimers were isolated and identified from more than 17 Rumex species (Table 2). Among them, anthraquinone O- and C- glycosides with glucose, galactose, rhamnose, and 6-hydroxyacetylated glucose as commonly existing sugar moieties, were normally found in Rumex. Three anthraquinones, chrysophanol (1), emodin (8) and physcion (18) are commonly used indicators to evaluate the quality of Rumex plants [22]. Some new molecules were also reported. For example, xanthorin-5-methylether (30) was isolated from R. patientia for the first time [23, 24], and two new antioxidant anthraquinones, obtusifolate A (45) and B (46) were isolated from R. obtusifolius [25].

Structures of quinones (1–56)

The anthranones often existed in pairs of enantiomers, whose meso-position is commonly connected with a C-glycosyl moiety. The enantiomers, rumejaposides A (21) and B (22), E (25) and F (26), G (27) and H (28) were reported from R. dentatus, R. japonicus, R. nepalensis and R. patientia [26-28]. Three hydroxyanthrones, chrysophanol anthrone (7), emodin anthrone (17), physcion anthrone (20), whose C-10 were reduced as an alphatic methylene, were isolated from the roots of R. acetosa for the first time [29], while a new anthrone, rumexone (31) was reported from the roots of R. crispus [30]. Two anthranones, 10-hydroxyaloins A (39) and B (40) were reported from Rumex for the first time [31]. A new 8-ionized hydroxylated 9, 10-anthraquinone namely, rumpictusoide A (56) was isolated from the whole plant of R. pictus [183]. Moreover, two new oxanthrone C-glucosides 6-methoxyl-10-hydroxyaloins A (41) and B (42) were isolated from the roots of R. gmelini [32].

Seco-anthraquinones are oxidized anthraquinones with a loop opened at C-10, resulting in the fixed planar structure of anthraquinone destroyed and causing of a steric hindrance between the two left benzene rings. So far, only two seco-anthraquinone glucosides, nepalensides A (49) and B (50) were reported from the roots of R. nepalensis [33].

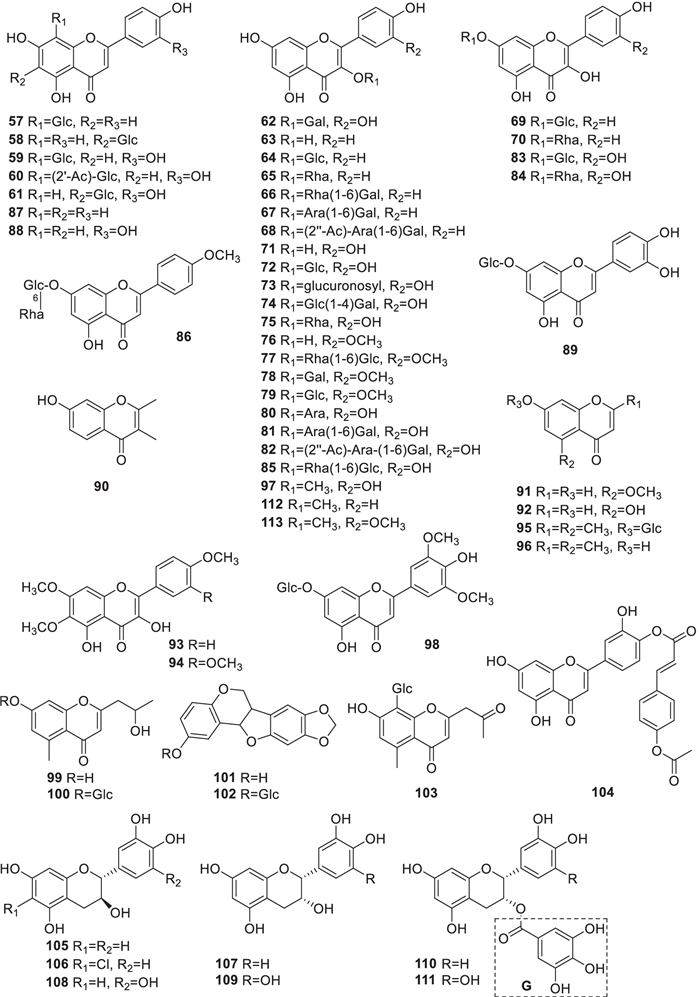

3.2 Flavonoids

Flavonoids are one of the most important bioactive components existing widely in plant kingdom. To date, 57 flavonoids (57–113) including flavones, flavanols, chromones and their

glycosides were reported from Rumex (Fig. 2, Table 2). They are mostly derived from kaempferol (63) and quercetin (71) connecting with glucosyl, rhamnosyl, galactosyl and arabinosyl moieties at different positions. For example, kaempferol (63) together with seven glycosides, -3-O-β-D-glucoside (64), -3-O-α-L-rhamnoside (65), -3-O-α-L-rhamnosyl-(1 → 6)-β-D-galactoside(66), -3-O-α-L-arabinosyl-(1 → 6)-β-D-galactoside (67), -3-O-(2''-O-acetyl-α-L-arabinosyl)-(1 → 6)-β-D-galactoside (68), -7-O-β-D-glucoside (69) and -7-O-α-L-rhamnoside (70) [14, 23, 34-42], and quercetin (71) together with 11 derivatives, -3-O-β-D-glucoside (72), -3-O-β-D-glucuronide (73), -3-O-β-D-glucosyl(1 → 4)-β-D-galactoside (74), -3-O-α-L-rhamnoside (75), -3-O-α-L-arabinoside (80), -3-O-α-L-arabinosyl-(1 → 6)-β-D-galactoside (81), -3-O-[2''-O-acetyl-α-L-arabinosyl]-(1 → 6)-β-D-galactoside (82), -7-O-β-D-glucoside (83), -7-O-α-L-rhamnoside (84), 3-O-methyl quercetin (97) and -3, 3'-dimethylether (113) [14, 23, 27, 35, 37, 38, 40-50, 148], were reported from several Rumex plants.

Structures of flavonoids (57–113)

Moreover, a new chromone glucoside, 2, 5-dimethyl-7-hydroxychromone-7-O-β-D-glucoside (95) was isolated from the root of R. gmelini [31], and five chromones, 7-hydroxy-2, 3-dimethyl-chromone (90), 5-methoxy-7-hydroxy-1(3H)-chromone (91), 5, 7-dihydroxy-1(3H)-chromone (92), 2, 5-dimethyl-7-hydroxychromone-7-O-β-D-glucoside (95) and 2, 5-dimethyl-7-hydroxychromone (96) were reported from R. gmelini, R. nepalensis, R. patientia and R. cristatus [31, 51-53].

Catechin (105) and epicatechin (107) are commonly distributed in R. patientia, the roots of R. rechingerianus, the whole plant of R. crispus, and the leaves of R. acetosa [34, 37, 39, 49, 54, 55]. Moreover, a variety of flavan-3-ols, 105, 107, epicatechin-3-O-gallate (110), epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate (111) were isolated from R. acetosa [49, 56].

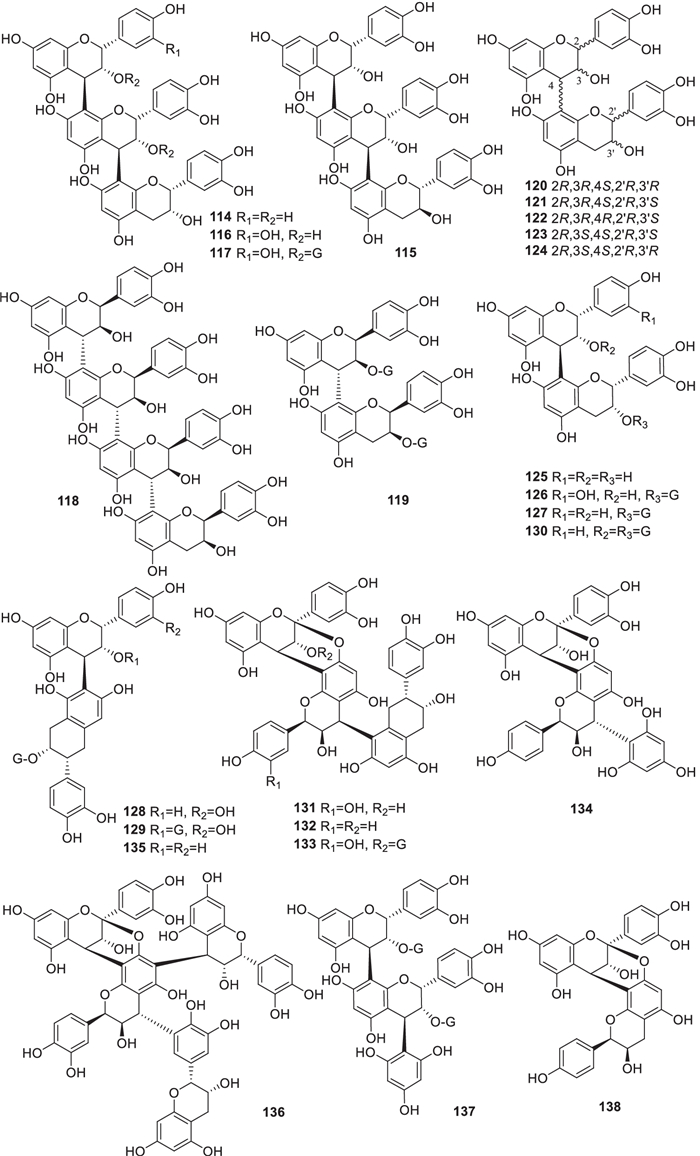

3.3 Tannins

Tannins, which may be involved with the hemostasis activity, are abundant in Rumex plants. So far, 25 condensed tannins (114–138) (Fig. 3, Table 2) were reported from the genus Rumex.

Structures of tannins (114–138)

Chemical investigations on the EtOAc fraction of acetone–water extract of the aerial parts of R. acetosa showed that R. acetosa was rich in tannins. Five new condensed tannin dimers, epiafzelechin-(4β → 8)-epicatechin-3-O-gallate (127), cinnamtannin B1-3-O-gallate (132) and epiafzelechin-(4β → 6)-epicatechin-3-O-gallate (135), and trimers, epiafzelechin-(4β → 8)-epicatechin-(4β → 8)-epicatechin (114), and epicatechin-(2β → 7, 4β → 8)-epiafzelechin-(4α → 8)-epicatechin (132), were reported. In addition, some procyanidins and propelargonidins, epiafzelechin-(4β → 8)-epicatechin-(4β → 8)-epicatechin (114), epicatechin-(4β → 8)-epi-catechin-(4β → 8)-catechin (115), procyanidin C1 (116), epicatechin-(4β → 6)-catechin (121), procyanidin B1-B5 (120, 122–125), and epicatechin-(4β → 8)-epicatechin-3-O-gallate (126), were also isolated [56, 107].

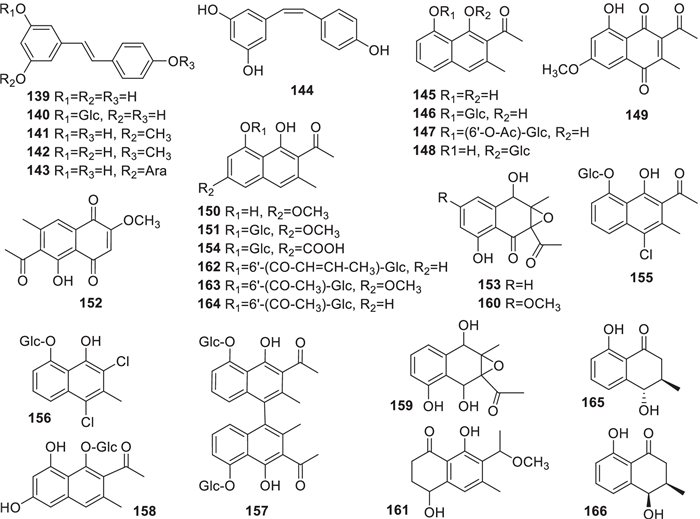

3.4 Stilbenes

So far, 6 stilbenes have been separated from Rumex (139–144) (Fig. 4, Table 2). Resveratrol (139) isolated from R. japonica Houtt was found for the first time from the Polygonaceae family [108]. It has been widely applied in cardiovascular protection and as antioxidation agent [109]. Resveratrol (139), (Z)-resveratrol (140) and polydatin (141) were obtained from Rumex spp. [14, 32, 35, 45, 110, 111]. 5, 4'-Dihydroxy-3-methoxystilbene (142), 3, 5-dihydroxy-4'-methoxystilbene (143) and 5, 4'-dihydroxy-stilbene-3-O-α-arabinoside (144) were separated from the roots of R. bucephalophorus [77].

Structures of stilbenes (139–144) and naphthalenes (145–166)

3.5 Naphthalenes

Naphthalenes are also widely distributed in Rumex. At present, 22 naphthalenes including naphthol, α-naphthoquinones and their derivatives have been identified from Rumex (145–166) (Fig. 4, Table 2). Nepodin (145) and nepodin-8-O-β-D-glucoside (146) are widespread in Rumex [31, 45, 112, 113]. In addition, 145, nepodin-8-O-β-D-(6'-O-acetyl)-glucoside (147), rumexoside (154), 6-hydroxymusizin-8-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (158) and hastatuside B (164) were isolated from R. hastatus [35, 110, 114]. 2-Methoxystypandrone (152) was isolated from R. japonicus and R. maritimus [115, 116]. Notably, some naphthalenes containing Cl, 2-acetyl-4-chloro-1, 8-dihydroxy-3-methylnaphthalene-8-O-β-D-glucoside (155) and patientoside B (156) were isolated from R. patientia [117]. Moreover, 3-acetyl-2-methyl-1, 5-dihydroxyl-2, 3- epoxynaphthoquinol (153), 3-acetyl-2-methyl-1, 4, 5-trihydroxyl-2, 3-epoxy-naphtho-quinol (159) and 3-acetyl-2-methyl-1, 5-dihydroxyl-7-methoxyl-2, 3-epoxynaphthoquinol (160), which contain the ethylene oxide part of the structure, were rarely found in Rumex, and they were reported from R. patientia, R. japonicus and R. nepalensis [51, 65, 118, 119]. 4, 4''-Binaphthalene-8, 8''-O, O-di-β-D-glucoside (157) was isolated from R. patientia [120].

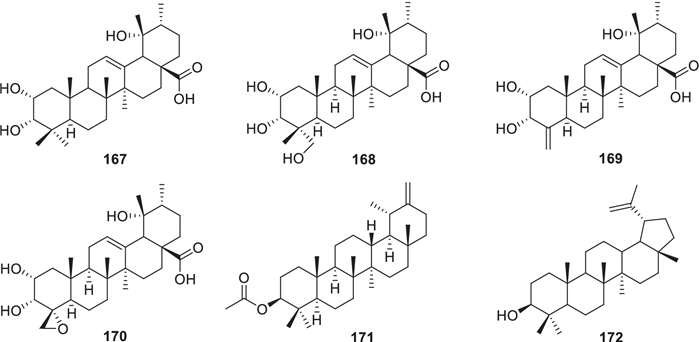

3.6 Terpenes

Until now, only six terpenes have been reported from Rumex (Fig. 5, Table 2). Four pentacyclic triterpenes, i.e., tormentic acid (167), myrianthic acid (168) and 2α, 3α, 19α-trihydroxy-24-norurs-4(23), 12-dien-28-oic acid (169) and (4R)-23-epoxy-2α, 3α, 19α-trihydroxy-24-norurs-12-en-28-oic acid (170) were obtained from the EtOAc fraction of the stems of R. japonicus. Of them, 169 and 170 were two new 24-norursane type triterpenoids, whose C-12 and C-13 were existed as double bonds [121]. A ursane (α-amyrane) type triterpene, taraxasterol acetate (171) was isolated from R. hastatus. [63]. And lupeol (172) was isolated from the roots of R. nepalensis for the first time [122].

Structures of terpenes (167–172)

3.7 Diterpene alkaloids

So far, only three hetisane-type (C-20) diterpene alkaloids, orientinine (7, 11, 14-trihydroxy-2, 13-dioxohetisane, 173), acorientine (6, 13, 15-trihydroxyhetisane, 174) and panicudine (6-hydroxy-11-deoxy-13-dehydrohetisane, 175) were reported from the aerial part of R. pictus. They might be biosynthesized from tetra- or penta-cyclic diterpenes [75] (Fig. 6, Table 2).

Structures of diterpene alkaloids (173–175)

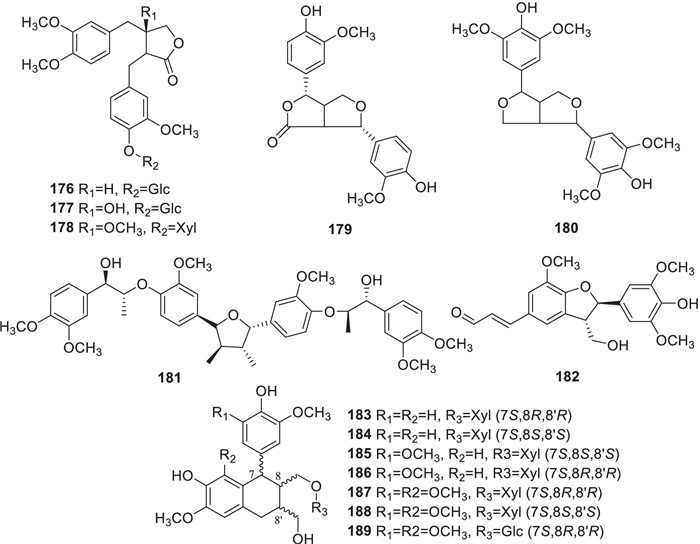

3.8 Lignans

Fourteen lignans (176–189) were summarized from Rumex (Fig. 7, Table 2). A new lignan, 3-methoxyarctiin-4''-O-β-D-xyloside (178), and two known ones, arctiin (176) and 3-hydroxy-arctiin (177), were obtained from R. patientia [23]. Six lignan glycosides, schizandriside (183), (-)-isolariciresinol-9-O-β-D-xylopyranoside (184), (-)-5-methoxyisolariciresinol-9-O-β-D-xylopyranoside (185), (+)-5-methoxyisolariciresinol-9-O-β-D-xylopyranoside (186), (+)-lyoniside (187) and nudiposide (188) were reported from R. hastatus for the first time [111].

Structures of lignans (176–189)

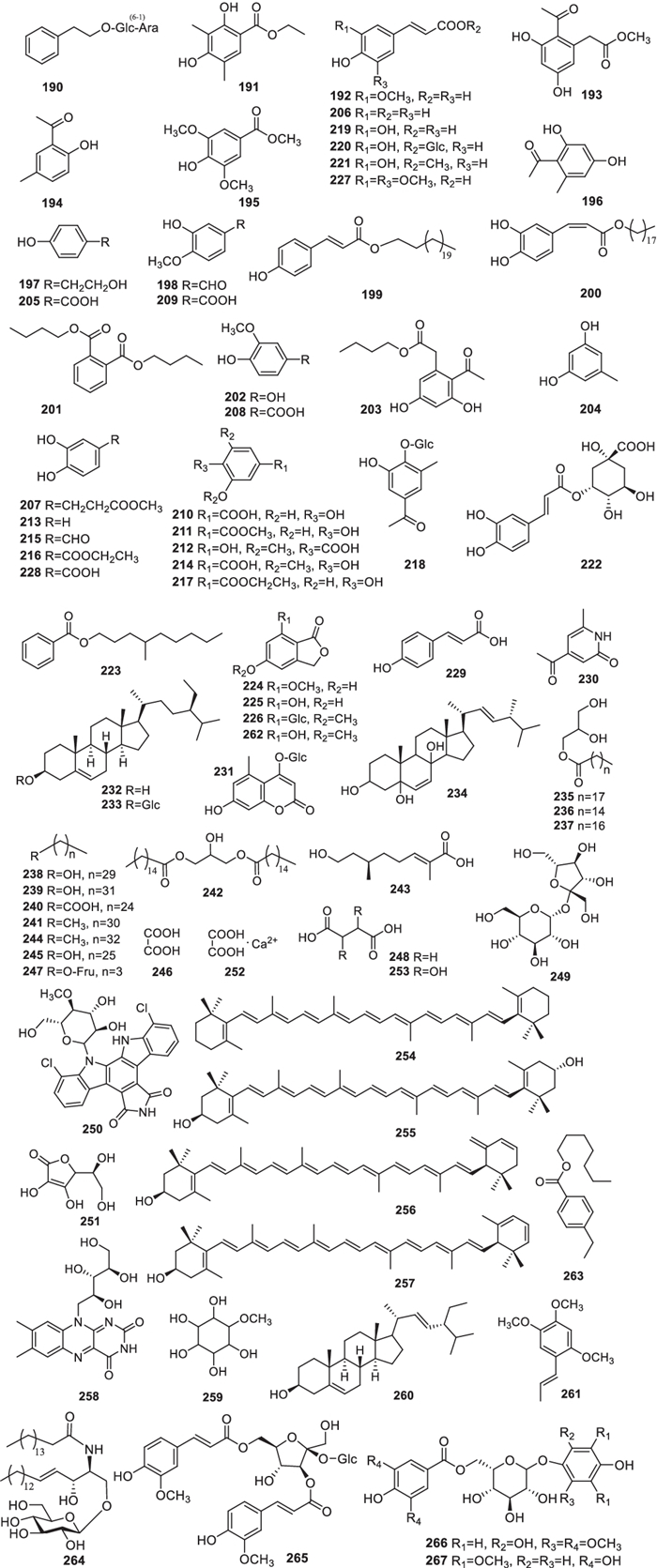

3.9 Other compounds

Up to now, 79 coumarins, sterides, alkaloids, glycosides and polysaccharide were found in Rumex (190–268) (Fig. 8, Table 2). Phenylethyl-O-α-L-arabinopyransy-(1 → 6)-O-β-D-glucoside (190) and 5-methoxyl-1(3H)-benzofuranone-7-glucoside (226) were isolated from R. gmelini for the first time [31]. p-Hydroxybenzoic acid (205), p-coumaric acid (206), methyl 3, 4-dihydrophenylpropionate (207), vanillic acid (208) and isovanillic acid (209) were isolated from the leaves of R. acetosa [39]. β-Sitosterol (232) and daucosterol (233) are commonly distributed in R. acetosa, R. chinensis, R. crispus and R. gmelini [31, 34, 39, 101]. 2, 6-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxyl benzoic acid (212) was isolated from R. japonicus [26]. Moreover, rumexin (218), caffeic acid (219), 1-O-caffeoylglucose (220) and 1-methyl caffeic acid (221) were isolated from the aerial parts of R. aquatica [38]. Recently, one new compound (S)-4′-methylnonyl benzoate (223) was reported from R. dentatus [14]. Ergosta-6, 22-diene-3, 5, 8-triol (234) was isolated from the EtOAc fraction of R. abyssinicus for the first time [123]. Conventional techniques and supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) were compared and the latter yielded great efficiency of phenolics from the roots of R. acetosa [124].

Structures of other compounds (190–268) (Note: 268 not given)

Ceryl alcohol (245) from R. ecklonianus [125], and β-carotene (254) and lutein (255) from R. vesicarius [126] were reported. Moreover, anhydroluteins I (256) and Ⅱ (257) were separated from R. rugosus together with 255 [95]. From the roots of R. dentatus, helonioside A (265) was isolated for the first time [48]. One new phloroglucinol glycoside 1-O-β-D-(2, 4-dihydroxy-6-methoxyphenyl)-6-O-(4-hydroxy-3, 5-dimethoxybenzoyl)-glucoside (266) was isolated from R. acetosa [56]. It was the first time that 1-O-β-D-(3, 5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxyphenol)-(6-O-galloyl)-glucoside (267) was isolated from R. nepalensis [33].

Rumex polysaccharides have rarely been studied, and only one polysaccharide, RA-P (268), which has a 30 kDa molecular weight and consists of D-glucose and D-arabinose, was reported from R. acetosa [127].

4 LC–MS analysis

The chemical compositions of Rumex spp. were also analyzed by LC–MS techniques. Untargeted metabolomic profiling via UHPLC-Q-TOF–MS analysis on the flowers and stems of R. tunetanus resulted in the identification of 60 compounds, 18 of which were reported from the Polygonaceae family for the first time. Quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucuronide (73) was found to be the most abundant phenolic compound in flowers and epicatechin-3-O-gallate (110) in stems [103]. Moreover, 44 bioactive components classified as sugars, flavanols, tannins and phenolics were clarified from the flowers and stems of R. algeriensis based on RP-HPLC–DAD-QTOF-MS and MS–MS [102]. The analysis of sex-related differences in phenolics of R. thyrsiflorus has shown female plants of R. thyrsiflorus contain more bioactive components than males, such as phenolic acids and flavonoids, especially catechin (105) [20].

5 Bioactivity

Rumex has been used as food and medicine in the folk. In addition to important role of Rumex in the traditional application, during the past few decades, it was subjected to scientific investigations of the structure of isolated chemical components and their clinical applications by several research groups. Pharmacological studies on Rumex extracts and its pure components revealed a wide range of bioactivities, involving antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, renal and gastrointestinal protective effects, antioxidant, antitumor and anti-diabetes effects.

5.1 Antimicrobial

Bioassay-guided isolation on the whole plants of R. abyssinicus yielded six antimicrobial quinones, chrysophanol (1) and its 8-O-β-D-glucoside (3), emodin (8), 6-hydroxyemodin (14), physcion (18) and its 8-O-β-D-glucoside (19), with MIC values of 8—256 μg/mL [123].

Proanthocyanidin-enriched extract from the aqueous fraction of the acetone–water (7: 3) extract of the aerial parts of R. acetosa (5 μg/mL—15 μg/mL) could interfered with the adhesion of Porphyromonas gingivalis (ATCC 33, 277) to KB cells (ATCC CCL-17) both in vitro and in situ. In silico docking assay, a main active constituent from R. acetosa, epiafzelechin-3-O-gallate-(4β → 8)-epicatechin-3-O-gallate (130) exhibited the ability to interact with the active side of Arg-gingipain and the hemagglutinin from P. gingivalis [139].

A bacteriostasis experiment of two naphthalenes, torachrysone (150) and 2-methoxy-stypandrone (152) isolated from R. japonicus roots, showed inhibitory effect on both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria [152]. The antibacterial (Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Moraxella catarrhalis, etc.) potential of the n-hexane, chloroform, aqueous fractions of 14 Rumex from Carpathian Basin (R. acetosella, R. acetosa, R. alpinus, R. aquaticus, R. crispus, R. patientia, R. pulcher, R. conglomeratus, R. thyrsiflorus, etc.) were investigated by the disc diffusion method. It showed that the n-hexane and chloroform fractions of roots of R. acetosa, R. alpinus, R. aquaticus, R. conglomeratus and R. patientia exhibited stronger activity against bacteria (inhibition zones > 15 mm). Naphthalenes (145, 146, 151, 152) exhibited antibacterial capacity against several bacterial strains (MIC = 48—57.8 μM, in case of M. catarrhalis; MIC = 96—529.1 μM, in case of B. subtilis) than anthraquinones (1, 3, 8, 12, 14, 18), flavonoids (62, 71, 80, 105, 112, 113), stilbenes (139, 141) and 1-stearoylglycerol (237), etc., which were isolated from R. aquaticus [148].

Antimicrobial study demonstrated that R. crispus and R. sanguineus have the potential for wound healing due to their anti-Acinetobacter baumannii activities (MIC = 1.0—2.0 mg/mL, R. crispus; 1.0—2.8 mg/mL, aerial parts of R. sanguineus; 1.4—4.0 mg/mL, roots of R. sanguineus) [106].

5.2 Anti-inflammatory

The potential effects of anti-inflammatory of AST2017-01 composing of processed R. crispus and Cordyceps militaris which was widely used in folk medicines in Korea, as well as chrysophanol (1) on the treatment of ovalbumin-induced allergic rhinitis (AR) rats were investigated. The serum and tissue nasal mucosa levels of IgE, histamine, TSLP, TNF-α, IL-1, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 were both decreased by treatment with AST2017-01 and 1 (positive control: dexamethasone), indicating that R. crispus and 1 has the ability to prevent and treat AR [153]. The aqueous extract of roots of R. patientia has anti-inflammatory action in vivo. The higher dose of extract (150 mg/kg) showed inhibition (41.7%) of edema in rats compared with the positive control, indomethacin (10 mg/kg, 36.6%) [21]. Methanolic extracts of the roots and stems of R. roseus exhibited anti-inflammatory functions in intestinal epithelial cells, reducing TNF-α-induced gene expression of IL-6 and IL-8 [154].

The ethanol extract of the roots of R. japonicus could be a therapeutic agent for atopic dermatitis. Skin inflammation in Balb/c mice was alleviated with the extract in vivo. Moreover, an in vitro experiment showed that the extract of R. japonicus decreased the phosphorylation of MAPK and stimulated NF-κB in TNF-α in HaCaT cells [155]. The methanolic extract of R. japonicus inhibited dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in C57BL/6 N mice by protecting tight junction connections in the colonic tissue. It was observed that R. japonicus has the potential to treat colitis [156]. Ethyl acetate extract of the roots of R. crispus showed anti-inflammatory activity in inhibiting NO production and decreasing the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines [157].

5.3 Antivirus

1, 4-Naphthoquinone and naphthalenes from R. aquaticus presented antiviral activity against herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) replication infected Vero cells. In which, musizin (145) showed dose dependent inhibitory property, causing a 2.00 log10 reduction in HSV-2 at 6.25 μM, on a traditional virus yield reduction test and qPCR assay. It suggested that R. aquaticus had the potential to treat HSV-2 infected patients [158].

Acetone–water extract (R2, which contains oligomeric, polymeric proanthocyanidins and flavonoids) from the aerial parts of R. acetosa showed obvious antiviral activities via plaque reduction test and MTT assay on Vero cells. R2 was 100% against herpes simplex virus type-1 at concentrations > 1 μg/mL (IC50 = 0.8 ± 0.04 μg/mL). At concentrations > 25 μg/mL (CC50 = 78.6 ± 12.7 μg/mL), cell vitality was more than 100% reduced by R2 [107].

5.4 The function in kidney and gastrointestinal tract

It is noted that quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucoside (72, QGC) from R. aquaticus could alleviate the modle that indomethacin (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) induced gastric damage of rats and ethanol extract of R. aquaticus had a protective effect on the inflammation of gastric epithelial cells caused by Helicobacter pylori. In vivo research suggested that QGC pretreatment could decrease gastric damage by increasing mucus secretion, downregulating the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and decreasing the activity of myeloperoxidase. The in vitro test found that flavonoids including QGC could inhibit proinflammatory cytokine expression and inhibit the proliferation of an adenocarcinoma gastric cell line (AGS) [159, 160]. The cytoprotective effect of QGC against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress was noticed in AGS [161]. Moreover, QGC also showed protective efficiency in a rat reflux esophagitis model in a dose-dependent manner (1—30 mg/kg) [162].

Ten anthraquinones chrysophanol (1), chrysophanol-8-O-β-D-glucoside (3), 6'-acetyl-chrysophanol-8-O-β-D-glucoside (6), emodin (8), emodin-8-O-β-D-glucoside (12), physcion (18), aloe-emodin (13), rumexpatientosides A (47) and B (48) and nepalenside A (49) from R. patientia, R. nepalensis, R. hastatus not only inhibited the secretion of IL-6, but also decreased collagen Ⅳ and fibronectin production at a concentration of 10 µM in vitro. On which concentration, they were nontoxic to cells [133]. It suggested that anthraquinones have great potential to treat kidney disease.

5.5 Antioxidant properties

An extraction technology to obtain the total phenolics of R. acetosa was optimized and the antioxidant activity of different plant parts of R. acetosa was well investigated. It was found that the 80% methanol extract of the roots (IC50 = 118.8 μM) showed higher scavenging activity to DPPH free radicals than the other parts (leaves: IC50 = 201.6 μM, flowers and fruits: IC50 = 230.1 μM, stems: IC50 = 411.2 μM) [163]. The roots of R. thyrsiflorus [164], ethanol extracts of R. obtusifolius and R. crispus showed antioxidant ability on DPPH, ABTS+ and FRAP assays [165]. Moreover, R. tingitanus leaves, R. dentatus, R. rothschildianus leaves, R. roseus and R. vesicarius also showed antioxidant activity on DPPH assay [13, 78, 105, 154, 166, 167]. Phenolics isolated from R. tunetanus flowers and stems displayed antioxidant properties on DPPH and FRAP assays [103]. DPPH, ABTS+, NO2− radical scavenging and phosphomolybdate antioxidant assays verified that R. acetosella has antioxidant properties [168]. Phenolic constitutions from R. maderensis dispalyed antioxidant activity after the gastrointestinal digestion process. These components are known as dietary polyphenols and have the potential to be developed as functional products [99].

Moreover, the total antioxidant capacities of R. crispus were found to be 49.4%—86.4% on DPPH, ABTS+, NO, phosphomolybdate and SPF assays, which provided the basis to develop R. crispus as antioxidant, antiaging and skin care products [169]. Later on, the ripe fruits of R. crispus were studied and the aqueous extract showed antioxidant activity in vitro [170]. Dichloromethane and ethyl acetate extracts of R. crispus exhibited stronger antioxidant activity, which were associated with the concentration of polyphenols and flavonoids [157]. The antioxidant activities of chrysophanol (1), 1, 3, 7-trihydroxy-6-methylanthraquinone (54), przewalskinone B (55) and p-coumaric acid (206) isolated from R. hastatus were investigated on a nitric oxide radical scavenging assay, whose IC50 values were 0.39, 0.47, 0.45, and 0.45 mM, respectively [134].

5.6 Antitumor properties

MTT assays on HeLa (human cervical carcinoma), A431 (skin epidermoid carcinoma) and MCF7 (human breast adenocarcinoma) cell lines showed that R. acetosa and R. thyrsiflorus could inhibit the tumor cell proliferation [171]. The fruit of R. crispus showed cytotoxicity on HeLa, MCF7 and HT-29 (colon adenocarcinoma) cells in vitro [170]. The methanolic extract of R. vesicarius was assessed for hepatoprotective effects in vitro. CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity was observed at 100 mg/kg bw and 200 mg/kg bw. The plant also has cytotoxicity in HepG2 (human hepatoma cancer) cell lines [172]. Dichloromethane extract of R. crispus roots inhibited the growth and induced cellular apoptosis of HepG2 cells [157]. The hexane fraction of R. rothschildianus leaves showed 98.9% and 97.4% inhibition of HeLa cells and MCF7 cells at a concentration of 4 mg/mL [105].

Different plant parts (stems, roots, flowers and leaves) of R. vesicarius were screened for their cytotoxicity by the MTS method on MCF7, Lovo and Caco-2 (human colon cancer), and HepG2 cell lines. The stems displayed stronger cytotoxicity in vitro and with nontoxicity on zebrafish development, with IC50 values of 33.45—62.56 μM. At a concentration of 30 µg/mL, the chloroform extract of the stems inhibited the formation of ≥ 70% of intersegmental blood vessels and 100% of subintestinal vein blood vessels when treated zebrafish embryos, indicating the chloroform extract of R. vesicarius stems has apparent antitumor potential [15].

2-Methoxystypandrone (152) from R. japonicus exhibited antiproliferative effect on Jurkat cells and the potential to treat leukemia, by reducing the mitochondrial membrane potential and increasing the accumulation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen, as shown by flow cytometry [116]. The phenolic extract from the flower parts of R. acetosa exhibited in vitro antiproliferative effects on HaCaT cells. When increasing of the extract concentration from 25 μg/mL to 100 μg/mL, the proliferation ability on HaCaT cells gradually decreased [147].

5.7 Antidiabetes activities

Chrysophanol (1) and physcion (18) from the roots of R. crispus showed inhibition on α-glucosidase, with IC50 values of 20.1 and 18.9 μM, respectively [180]. The alcohol extract of R. acetosella displayed stronger inhibitory activity on α-glucosidase (roots, IC50 = 12.3 μM; aerial parts, IC50 < 10 μM), compared to the positive control, acarbose (IC50 = 605 μM, p < 0.05), revealing R. acetosella could be developed as an antidiabetic agent [168]. Moreover, the methanolic extract of R. lunaria leaves displayed remarkable kinetic of -α-glucosidase activity from the concentration of 3 μM by comparison with blank control [16], and the acetone fraction of R. rothschildianus leaves showed inhibitory activity against α-amylase and α-glucosidase (IC50 = 19.1 ± 0.7 μM and 54.9 ± 0.3 μM, respectively) compared to acarbose (IC50 = 28.8, 37.1 ± 0.3 μM, respectively) [105].

The hypoglycemic effects of oral administration of ethanol extract of R. obtusifolius seeds (treatment group) were compared to the control group (rabbits with hyperglycemia). The treatment group could decrease fasting glucose levels (57.3%, p < 0.05), improve glucose tolerance and increase the content of liver glycogen (1.5-fold, p < 0.01). It also not only reduced the total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and liver enzyme levels, but increased the high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. The results showed that R. obtusifolius has great potential to treat diabetes [173]. In addition, phenolic components of R. dentatus showed the ability to ameliorate hyperglycemia by modulating carbohydrate metabolism in the liver and oxidative stress levels and upregulating PPARγ in diabetic rats [14].

5.8 Other biological activities

The vasorelaxant antihypertensive mechanism of R. acetosa was investigated in vivo and in vitro. Intravenous injection (50 mg/kg) of the methanol extract of R. acetosa (Ra.Cr) leaves caused a mean arterial pressure (MAP) (40 mmHg) in normotensive rats with a decrease of 27.88 ± 4.55% and a MAP (70 mmHg) in hypertensive rats with a decrease of 48.40 ± 4.93%. In endothelium intact rat aortic rings precontracted with phenylephrine (1 μM), Ra.Cr induced endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation with EC50 = 0.32 mg/mL (0.21—0.42), while in denuded endothelial rat aortic rings, EC50 = 4.22 mg/mL (3.2—5.42), which was partially blocked with L-NAME (10 μM), indomethacin (1 μM) and atropine (1 μM). In isolated rabbit aortic rings precontracted with phenylephrine (1 μM) and K+ (80 mM), Ra.Cr induces vasorelaxation and the movement of Ca2+ [174].

The acetone extract of R. japonicus showed protective activity against myocardial apoptosis, through the regulation of oxidative stress levels in cardiomyocytes (LDH, MDA, CK, SOD) and the suppression of the expression of apoptosis proteins (caspase-3, Bax, Bcl-2) on in vitro H2O2-induced myocardial H9c2 cell apoptosis [175].

The antiplatelet activity of R. acetosa and the protective mechanism on cardiovascular system were investigated yet. The extract of R. acetosa showed inhibition of the collagen-induced platelet aggregation by modulating the phosphorylation of MAPK, PI3K/Akt, and Src family kinases and inhibited the ATP release in a dose dependent manner (25—200 μg/mL) [176]. The absorption of fexofenadine was inhibited by the ethanol extract of R. acetosa to decrease the aqueous solubility of fexofenadine [177]. The hepatoprotective effect of R. tingitanus was investigated by an in vivo experiment, in which the ethanol extract protected effectively the CCl4-damaged rats by enhancing the activity of liver antioxidant enzymes. Moreover, the extract could reduce the immobility time of mice, comparable of the positive drug, clomipramine. The results indicated that R. tingitanus has antidepressant-like effects [78].

Stimulating the ERK/Runx2 signaling pathway and related transcription factors could induce the differentiation of osteoblasts. Fortunately, chrysophanol (1), emodin (8) and physcion (18) from the aqueous extract of R. crispus could suppress the RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation by suppressing the MAPK/NF-κB/NFATc1 signaling axis and increas the inhibitory factors of NFATc1 [178].

Moreover, the ethanol extract of R. crispus could reduce the degradation of collagen by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-13), indicating that R. crispus exhibited the antiaging function [169].

The anti-Alzheimer effect of helminthosporin (51) from R. abyssinicus was investigated in PAMPA-BBB permeability research, showing that 51 inhibited obviously AChE and BChE with IC50 values < 3 μM. Compound 51 could not only cross the BBB with high BBB permeability, but also bind with the peripheral anion part of the cholinesterase activity site by molecular docking [80].

It is noted, R. crispus, a traditional medicinal herb in the folk with rich retinol, ascorbic acid and α-tocopherol in the leaves, could be used as a complementary diet [179]. Moreover, chrysophanol (1) and physcion (18) from R. crispus roots showed obvious inhibitory activity on xanthine oxidase (IC50 = 36.4, 45.0 μg/mL, respectively) [180].

Inhibition of human pancreatic lipase could reduce the hydrolysis of triacylglycerol into monoacylglycerol and free fatty acids [181]. Chrysophanol (1) and physcion (18) from R. nepalensis with good inhibitory activity on pancreatic lipase (Pearson's r = 0.801 and 0.755, respectively) showed the obvious potential to treat obesity [182].

6 Conclusion

The genus Rumex distributing widely in the world with more than 200 species has a long history of food and medicinal application in the folk. These plants with rich secondary metabolites, e.g., quinones, flavonoids, tannins, stilbenes, naphthalenes, terpenes, diterpene alkaloids, lignans and other type of components, showed various pharmacological activities, such as antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, renal and gastrointestinal protective effects, antioxidant, antitumor and anti-diabetes effects. Particularly, quinones as the major components in Rumex showed stronger antibacterial activities and exerted the potential to treat kidney disease. However, detailed phytochemical studies are needed for many Rumex species, in order to clarify their bioactive components. Further studies and application may focus on the antitumor, anti-diabetes, anti-microbial, hepatoprotective, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal protective effects. Moreover, the toxicity or side effects for Rumex plants and their chemical constituents should be evaluated, in order to make the uses of Rumex more safety.

Notes

Abbreviations

AChE: Acetylcholinesterase; AGS: Adenocarcinoma gastric cell line; AR: Allergic rhinitis; BBB: Blood-brain barrier; BChE: Butyrylcholinesterase; EtOAc: Ethyl acetate; HPLC: High performance liquid chromatograph; IL: Interleukin; UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS: Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-quad- rupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry; MAPK: Mitogen-activated protein kinase; MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration; MS: Mass Spectrometry; MTT: 3-(4, 5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide; NF-κB: Nuclear factor-kappa B; QGC: Quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucoside; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, China (2021YFE0103600) for International Scientific and Technological Innovative Cooperation between Governments.

Author contributions

J-J L, Y-X L, H-T Z, DW collected the related references; J-J L worte the manu- script; NL and Y-J Z reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

-

1.http://www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/APweb/. Accessed 22 Jan 2021. PubMed Google Scholar

-

2.Liddell HG, Scott R, Jones HS, McKenzie R. A Greek-English lexicon. In: Fontaine D, editor. 9th edn. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1940. p. 442. https://areopage.net/PDF/LSJ.pdf. PubMed Google Scholar

-

3.Saleh NAM, Elhadidi N, Arafa RFM. Flavonoids and anthraquinones of some egyptian Rumex species (Polygonaceae)[J]. Biochem Syst Ecol 21, 301-3 (1993) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

4.Korpelainen H, Pietiläinen M. Sorrel (Rumex acetosa L.): not only a weed but a promising vegetable and medicinal plant[J]. Bot Rev 86, 234-46 (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

5.Martin AC, Zim HS, Nelson AL. American wildlife and plants: a guide to wildlife food habits. (New York: Dover Publications, 1951). PubMed Google Scholar

-

6.

-

7.Magdalena W, Kosikowska U, Malm A, Smolarz H. Antimicrobial activity of the extracts from fruits of Rumex L. species[J]. Cent Eur J Biol 6, 1036-43 (2011) PubMed Google Scholar

-

8.Guo CH, Yang SL. TCM name combing and specification suggestions in Rumex[J]. China Pharm 28, 3597-600 (2017) PubMed Google Scholar

-

9.Zhang GQ, Zhao HP, Wang ZY, Cheng JR, Tang XM. Recent advances in the study of chemical constituents and bioactivity of Rumex L[J]. World Sci Technol Mod Tradit Chin Med Mater Med 10, 86-93 (2008) PubMed Google Scholar

-

10.Meng QQ, Zhao L, Qin L, Qu S, Zhang SL, Cai GZ. Determination of contents of emodin and chrysophanol in Rumex patiential var. callosus processing with rice vinegar by HPLC[J]. Ginseng Res 29, 40-2 (2017) PubMed Google Scholar

-

11.Pan Y, Zhao X, Kim SH, Kang SA, Kim YG, Park KY. Anti-inflammatory effects of Beopje curly dock (Rumex crispus L.) in LPS-induced RAW 2647 cells and its active compounds[J]. J Food Biochem 44, e13291 (2020) PubMed Google Scholar

-

12.Siener R, Honow R, Seidler A, Voss S, Hesse A. Oxalate contents of species of the Polygonaceae, Amaranthaceae and Chenopodiaceae families[J]. Food Chem 98, 220-4 (2006) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

13.Chelly M, Chelly S, Salah HB, Athmouni K, Bitto A, Sellami H, Kallel C, Allouche N, Gdoura R, Bouaziz-Ketata H. Characterization, antioxidant and protective effects of edible Rumex roseus on erythrocyte oxidative damage induced by methomyl[J]. J Food Meas Charact 14, 229-43 (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

14.Elsayed RH, Kamel EM, Mahmoud AM, El-Bassuony AA, Bin-Jumah M, Lamsabhi AM, Ahmed SA. Rumex dentatus L. phenolics ameliorate hyperglycemia by modulating hepatic key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism, oxidative stress and PPARγ in diabetic rats[J]. Food Chem Toxicol 138, 111202 (2020) PubMed Google Scholar

-

15.Farooq M, Abutaha N, Mahboob S, Baabbad A, Almoutiri ND, Wadaan MAAM. Investigating the antiangiogenic potential of Rumex vesicarius (humeidh), anticancer activity in cancer cell lines and assessment of developmental toxicity in zebrafish embryos[J]. Saudi J Biol Sci 27, 611-22 (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

16.Guglielmina F, Diana LG, Francesca R, Margherita G, Stefania S, Stefano DA, Candelaria CSM. α-Glucosidase and glycation inhibitory activities of Rumex lunaria leaf extract: a promising plant against hyperglycaemia-related damage[J]. Nat Prod Res 34(23), 3418-22 (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

17.Quradha MM, Khan R, Mujeeb-ur-Rehman, Abohajeb A. Chemical composition and in vitro anticancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of essential oil and methanol extract from Rumex nervosus[J]. Nat Prod Res 33, 2554-2559 (2019) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

18.Khare CP. Indian medicinal plants. An illustrated Dictionary. (New York: Springer-Verlag, 2007). PubMed Google Scholar

-

19.An C, Chen M, Yang CZ, Meng J, Zhuang YX. The textual research and the name of ′′Jinbuhuan′′[J]. J Chin Med Mater 42, 2449-52 (2019) PubMed Google Scholar

-

20.Dziedzic K, Szopa A, Waligorski P, Ekiert H, Slesak H. Sex-related differences in the dioecious species Rumex Thyrsiflorus Fingerh.—analysis of the content of phenolic constituents in leaf extracts[J]. Acta Biol Cracov Bot 62, 43-50 (2020) PubMed Google Scholar

-

21.Süleyman H, Demirezer LÖ, Kuruüzüm A, Banoglu ZN, Gepdiremen A. Anti-inflammatory effect of the aqueous extract from Rumex patientia L[J]. roots. J Ethnopharmacol 65, 141-8 (1999) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

22.Wang JF, Wang JX, Teng Y, Zhang SS, Liu Y. Determination of anthraquinones in Rumex acetosa L[J]. J Southwest Univ 39, 199-204 (2017) PubMed Google Scholar

-

23.Gao LM, Wei XM, Zheng SZ, Shen XW, Su YZ. Studies on chemical constituents of Rumex patientia[J]. Chin Tradit Herbal Drugs 33, 207-9 (2002) PubMed Google Scholar

-

24.Su YZ, Gao LM, Zheng XD, Zheng SZ, Shen XW. Anthraquinones from Polygonum Rumex patientia L[J]. J Northwest China Norm Univ 36, 47-9 (2000) PubMed Google Scholar

-

25.Khabir A, Khan F, Haq ZU, Khan Z, Khan S. Two new antioxidant anthraquinones namely Obtusifolate A and B from Rumex obtusifolius[J]. Int J Biosci 10, 49-57 (2017) PubMed Google Scholar

-

26.Jiang LL, Zhang SW, Xuan LJ. Oxanthrone C-glycosides and epoxynaphthoquinol from the roots of Rumex japonicus[J]. Phytochemistry 68, 2444-9 (2007) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

27.Wang S, Zhang X. Studies on chemical constituents of ethyl acetate extracted from leaves of Rumex patientia Linn[J]. Acta Chin Med Pharmacol 47, 60-8 (2019) PubMed Google Scholar

-

28.Zhu JJ, Zhang CF, Zhang M, Bligh SWA, Yang L, Wang ZM, Wang ZT. Separation and identification of three epimeric pairs of new C-glucosyl anthrones from Rumex dentatus by on-line high performance liquid chromatography-circular dichroism analysis[J]. J Chromatogr A 1217, 5384-8 (2010) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

29.Michiko T, Jugo K. Isolation of hydroxyanthrones from the roots of Rumex acetosa Linn[J]. Agr Biol Chem Tokyo 46, 1913-4 (1982) PubMed Google Scholar

-

30.Gunaydin K, Topcu G, Ion RM. 1, 5-Dihydroxyanthraquinones and an anthrone from roots of Rumex crispus[J]. Nat Prod Lett 16, 65-70 (2002) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

31.Wang ZY, Cheng JR, Li RM, Wang ZQ. New chromone glucoside from roots of Rumex gmelini[J]. Nat Prod Res Dev 21, 189-91 (2009) PubMed Google Scholar

-

32.Wang ZY, Zhao HP, Zuo YM, Wang ZQ, Tang XM. Two new C-glucoside oxanthrones from Rumex gmelini[J]. Chin Chem Lett 20, 839-41 (2009) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

33.Mei RQ, Liang HX, Wang J, Zeng LH, Lu Q, Cheng YX. New seco-anthraquinone glucosides from Rumex nepalensis[J]. Planta Med 75, 1162-4 (2009) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

34.Fan JP, Zhang ZL. Studies on the chemical constituents from Rumex crispus L. (Ⅱ)[J]. J Guangdong Pharm Coll 25, 585-7 (2009) PubMed Google Scholar

-

35.Zhang LS, Cheng YX, Liu GM. Chemical constituents of the ethyl acetate extract from Rumex hastatus D[J]. Don. Chin Tradit Pat Med 34, 892-5 (2012) PubMed Google Scholar

-

36.Hawas UW, Ahmed EF, Abdelkader AF, Taie HAA. Biological activity of flavonol glycosides from Rumex dentatus plant, an Egyptian xerophyte[J]. J Med Plants Res 5, 4239-43 (2011) PubMed Google Scholar

-

37.Su YZ, Gao LM, Zheng XD, Zheng SZ, Shen XW. Flavonoids from Polygonum Rumex patientia L[J]. J Northwest China Norm Univ 36, 50-2 (2000) PubMed Google Scholar

-

38.Yoon H, Park J, Oh M, Kim K, Han J, Whang WK. A new acetophenone of aerial parts from Rumex aquatica[J]. Nat Prod Sci 11, 75-8 (2005) PubMed Google Scholar

-

39.Chen WS, Hu XH, Yuan WP. Chemical constituents in the leaves of Rumex acetosa L[J]. China J Tradit Chin Med Pharm 34, 3769-71 (2019) PubMed Google Scholar

-

40.Hasan A, Ahmed I, Jay M, Voirin B. Flavonoid glycosides and an anthraquinone from Rumex Chalepensis[J]. Phytochemistry 39, 1211-3 (1995) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

41.Salama HMH. Flavonoid glycosides from Rumex pictus[J]. Egypt J Bot 39, 41-52 (2000) PubMed Google Scholar

-

42.El-Fattah HA, Gohar A, El-Dahmy S, Hubaishi A. Phytochemical investigation of Rumex luminiastrum[J]. Acta pharm Hung 64, 83-5 (1994) PubMed Google Scholar

-

43.Orban-Gyapai O, Raghavan A, Vasas A, Forgo P, Hohmann J, Shah ZA. Flavonoids isolated from Rumex aquaticus exhibit neuroprotective and neurorestorative properties by enhancing neurite outgrowth and synaptophysin[J]. CNS Neurol Disord Drud Targets 13, 1458-64 (2014) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

44.Yang B, Wang HY, Zhao P, Shen DF. Studies on the constituents of anthraquinoe and flavonoid in the seed of Rumex patientia L[J]. Heilongjiang Med Pharm 38, 63-4 (2015) PubMed Google Scholar

-

45.Xu MY, Wang QB, Wei LM, Guo SL, Ding CH, Wang ZY. Chemical constituents of ethyl acetate extract from Rumex gmelini fruit[J]. Inf Tradit Chin Med 34, 22-6 (2017) PubMed Google Scholar

-

46.Zeng Y, Luo JJ, Li C. Chemical constituents from aerial part of Rumex patientia[J]. J Chin Med Mater 36, 57-60 (2013) PubMed Google Scholar

-

47.Zhao P, Dissertation, Jiamusi Univ, 2007. PubMed Google Scholar

-

48.Zhu JJ, Zhang CF, Zhang M, Wang ZT. Studies on chemical constituents in roots of Rumex dentatus[J]. China J Chin Mater Med 31, 1691-3 (2006) PubMed Google Scholar

-

49.Chumbalov TK, Kuznetsova LK, Taraskina KV. Catechins and flavonols of the roots of Rumex Rechingerianus[J]. Chem Nat Compd 5, 155-6 (1969) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

50.Zhao YL, Dong HQ, Zhang LS. Chemical constituents from the ethyl acetate portion of Rumex japonicus[J]. J Dali Univ 5, 27-30 (2020) PubMed Google Scholar

-

51.Deng LN, Li BR, Wang GW, Zhang JM, Ge JQ, Wang H, Liao ZH, Chen M. Chemical constituents from roots of Rumex nepalensis[J]. Chin Tradit Herbal Drugs 47, 2095-9 (2016) PubMed Google Scholar

-

52.Erturk S, Ozbas M, Imre S. Anthraquinone pigments from Rumex cristatus[J]. Acta pharm Turcica 43, 21-2 (2001) PubMed Google Scholar

-

53.Yuan Y, Chen WS, Zheng SQ, Yang GY, Zhang WD, Zhang HM. Studies on chemical constituents in root of Rumex patientia L[J]. China J Chin Mater Med 26, 40-2 (2001) PubMed Google Scholar

-

54.Ömür LD, Ayse KU, Bergere I, Schiewe HJ, Zeeck A. The structures of antioxidant and cytotoxic agents from natural source: anthraquinones and tannins from roots of Rumex patientia[J]. Phytochemistry 58, 1213-7 (2001) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

55.Stöggl WM, Huck CW, Bonn GK. Structural elucidation of catechin and epicat echin in sorrel leaf extracts using liquid chromatography coupled to diode array-, fluorescence and mass spectrometric detection[J]. J Sep Sci 27, 524-8 (2004) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

56.Bicker J, Petereit F, Hensel A. Proanthocyanidins and a phloroglucinol derivative from Rumex acetosa L[J]. Fitoterapia 80, 483-95 (2009) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

57.Kato T, Morita Y. C-glyxosylflavones with acetyl substitution from Rumex acetosa L[J]. Chem Pharm Bull 38, 2277-80 (1990) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

58.Sahreen S, Khan MR, Khan RA. Comprehensive assessment of phenolics and antiradical potential of Rumex hastatus D. Don. roots[J]. Bmc Complem Altern M 14, 1-11 (2014) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

59.https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/116820. Accessed 31 Dec 2021. PubMed Google Scholar

-

60.Jiang Y, Jiang ZB, Shao GJ, Guo DC, Tian Y, Song JJ, Lin YY. The extraction of main chemical compositions in Rumex root[J]. Adv Mater Res Switz 382, 372-4 (2012) PubMed Google Scholar

-

61.http://www.theplantlist.org. Accessed 31 Dec 2021. PubMed Google Scholar

-

62.Royer F, Dickinson R. Weeds of the Northern U.S. and Canada. (Canada: University of Alberta Press, 1999). PubMed Google Scholar

-

63.Zhang H, Guo ZJ, Wu N, Xu WM, Han L, Li N, Han YX. Two novel naphthalene glucosides and an anthraquinone isolated from Rumex dentatus and their antiproliferation activities in four cell lines[J]. Molecules 17, 843-50 (2012) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

64.Kang YH, Wang ZY, Li JK, Liu LM. Isolation and identification of two anthraquinones from Rumex gmelini Turcz[J]. China J Chin Mater Med 21, 741-2 (1996) PubMed Google Scholar

-

65.Zee OP, Kim DK, Kwon HC, Lee KR. A new epoxynaphthoquinol from Rumex japonicus[J]. Arch Pharm Res 21, 485-6 (1998) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

66.Rouf ASS, Islam MS, Rahman MT. Evaluation of antidiarrhoeal activity Rumex maritimus root[J]. J Ethnopharmacol 84, 307-10 (2003) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

67.Watt JM, Breyer-Brandwijk MG. The medicinal and poisonous plants of Southern Africa. (Edinburgh: Livingston, 1932). PubMed Google Scholar

-

68.Gairola S, Sharma J, Bedi YS. A cross-cultural analysis of Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh (India) medicinal plant use[J]. J Ethnopharmacol 155, 925-86 (2014) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

69.Akeroyd JR. Docks and knotweed of Britain and Ireland, vol. 3. (London: BSBI Handbook, 2015). PubMed Google Scholar

-

70.Akeroyd JR, Webb DA. Morphological variation in Rumex cristatus DC[J]. Bot J Linn Soc 106, 103-4 (1991) PubMed Google Scholar

-

71.Mosyakin SL. Rumex Flora of North America, vol. 5. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005). PubMed Google Scholar

-

72.El-Hawary SA, Sokkar NM, Ali ZY, Yehia MM. A profile of bioactive compounds of Rumex vesicarius L[J]. J Food Sci 76, C1195-202 (2011) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

73.Khan TH, Ganaie MA, Siddiqui NA, Alam A, Ansari MN. Antioxidant potential of Rumex vesicarius L.: in vitro approach[J]. Asian Pac J Trop Bio 4, 538-44 (2014) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

74.Salama HMH. Two crystalline compounds from Rumex pictus Forssk[J]. Egypt J Bot 36, 235-44 (1996) PubMed Google Scholar

-

75.Salama HMH. Diterpenoid alkaloids from Rumex pictus Forssk[J]. Egypt J Bot 37, 85-92 (1997) PubMed Google Scholar

-

76.http://flora.org.il/en/plants/. Accessed 31 Dec 2021. PubMed Google Scholar

-

77.Kerem Z, Regev SG, Flaishman MA, Sivan L. Resveratrol and two monomethylated stilbenes from Israeli Rumex bucephalophorus and their antioxidant potential[J]. J Nat Prod 66, 1270-2 (2003) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

78.Mhalla D, Bouassida KZ, Chawech R, Bouaziz A, Makni S, Jlaiel L, Tounsi S, Jarraya RM, Trigui M. Antioxidant, hepatoprotective, and antidepression effects of Rumex tingitanus extracts and identification of a novel bioactive compound[J]. Biomed Res Int (2018) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

79.Jimoh FO, Adedapo AA, Aliero AA, Afolayan AJ. Polyphenolic contents and biological activities of Rumex ecklonianus[J]. Pharm Biol 46, 333-40 (2008) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

80.Augustin N, Nuthakki VK, Abdullaha M, Hassan QP, Gandhi SG, Bharate SB. Discovery of helminthosporin, an anthraquinone isolated from Rumex abyssinicus Jacq as a dual cholinesterase inhibitor[J]. ACS Omega 5, 1616-24 (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

81.Jehlik V, Sádlo J, Dostálek J, Jarolimová V, Klimeŝ L. Chorology and ecology of Rumex confertus Willd. in the Czech Republic[J]. Bot Lith 7, 235-344 (2001) PubMed Google Scholar

-

82.http://www.bonap.org/. Accessed 31 Dec 2021. PubMed Google Scholar

-

83.Kołodziejek J, Patykowski J. Effect of environmental factors on germination and emergence of invasive Rumex confertus in central Europe[J]. Sci World J 2015, 1-10 (2015) PubMed Google Scholar

-

84.http://www.luontoportti.com/suomi/en/kukkakasvit/asiatic-dock. Accessed 31 Dec 2021. PubMed Google Scholar

-

85.Misiewicz J, Stosik T. Rumex confertus- an expansive weed found in the Fordon Valley[J]. Akademia Techniczno-Rolnicza 226, 77-84 (2000) PubMed Google Scholar

-

86.Piesik D, Wenda-Piesik A. Gastroidea viridula Deg. potential to control mossy sorrel (Rumex confertus Willd. )[J]. J Plant Protect Res 45, 63-72 (2005) PubMed Google Scholar

-

87.Raycheva T. Rumex confertus (Polygonaceae) in the Bulgarian flora[J]. Bot Serb 35, 55-9 (2011) PubMed Google Scholar

-

88.Stace C. New flora of the British Isles, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010). PubMed Google Scholar

-

89.Tokarska-Guzik B. The establishment and spread of alien plant species (Kenophytes) in the flora of Poland. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego; 2005. PubMed Google Scholar

-

90.https://npgsweb.arsgrin.gov/gringlobal/taxonomydetail.aspx?id=32527. Accessed 31 Dec 2021. PubMed Google Scholar

-

91.Wallentinus I. Introduced marine algae and vascular plants in European aquatic environments. (Dordrecht: Springer, 2002). PubMed Google Scholar

-

92.Charles WK. Applied medical botany. https://medivetus.com/botanic/rumex-hymenosepalus-wild-rhubarb-edible-and-medicinal-uses/. Accessed 31 Dec 2021. PubMed Google Scholar

-

93.Hillis WE. The isolation of chrysophanic acid and physcion from Rumex hymenosepalus Torr[J]. Aust J Chem 8, 290-2 (1955) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

94.Launert E. Edible and medicinal plants. (London: Hamlyn, 1981). PubMed Google Scholar

-

95.Molnár P, Ősz E, Zsila F, Deli J. Isolation and structure elucidation of anhydroluteins from cooked sorrel (Rumex rugosus Campd.)[J]. Chem Biodiv 2, 928-35 (2005) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

96.Rechinger KH. The North American species of Rumex. (Vorarbeiten zueiner monographie der gattung Rumex 5. Field Mus[J]. Nat Hist Bot Ser 17, 1-151 (1937) PubMed Google Scholar

-

97.Getie M, Gebre-Mariam T, Rietz R, Höhne C, Huschka C, Schmidtke M, Abate A, Neubert RHH. Evaluation of the anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory activities of the medicinal plants Dodonaea viscosa Rumex nervosus and Rumex abyssinicus[J]. Fitoterapia 74, 139-43 (2003) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

98.Sheikha AE. Rumex nervosus: an overview[J]. Int J Innov Hortic 4, 87-95 (2015) PubMed Google Scholar

-

99.Spinola V, Llorent-Martinez EJ, Castilho PC. Antioxidant polyphenols of madeira sorrel (Rumex maderensis): how do they survive to in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion[J]. Food Chem 259, 105-12 (2018) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

100.Spinola V, Llorent-Martinez EJ, Castilho PC. Inhibition of alpha-amylase, alpha-glucosidase and pancreatic lipase by phenolic compounds of Rumex maderensis (Madeira sorrel). Influence of simulated gastrointestinal digestion on hyperglycaemia-related damage linked with aldose reductase activity and protein glycation[J]. LWT Food Sci Technol (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

101.Pham DQ, Han JW, Dao NT, Kim J-C, Pham HT, Nguyen TH, Nguyen NT, Choi GJ, Vu HD, Dang QL. In vitro and in vivo antimicrobial potential against various phytopathogens and chemical constituents of the aerial part of Rumex chinensis Campd[J]. S Afr J Bot 133, 73-82 (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

102.Ammar S, Abidi J, Luca SV, Boumendjel M, Skalicka-Wozniak K, Bouaziz M. Untargeted metabolite profiling and phytochemical analysis based on RP-HPLC-DAD-QTOF-MS and MS/MS for discovering new bioactive compounds in Rumex algeriensis flowers and stems[J]. Phytochem Analysis 31, 616-35 (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

103.Abidi J, Ammar S, Ben Brahim S, Skalicka-Wozniak K, Ghrabi-Gammar Z, Bouaziz M. Use of ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry system as valuable tool for an untargeted metabolomic profiling of Rumex tunetanus flowers and stems and contribution to the antioxidant activity[J]. J Pharm Biomed 162, 66-81 (2019) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

104.Abidi J, Occhiuto C, Cimino F, Speciale A, Ruberto G, Siracusa L, Bouaziz M, Boumendjel M, Muscarà C, Saija A, Cristani M. Phytochemical and biological characterization of methanolic extracts from Rumex algeriensis and Rumex tunetanus[J]. Chem Biodivers (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

105.Jaradat N, Hawash M, Dass G. Phytochemical analysis, in-vitro anti-proliferative, anti-oxidant, anti-diabetic, and anti-obesity activities of Rumex rothschildianus Aarons. extracts[J]. BMC Complement Med 21, 107 (2021) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

106.Sabo VA, Svircev E, Mimica-Dukic N, Orcic D, Narancic J, Knezevic P. Anti-Acinetobacter baumannii activity of Rumex crispus L. and Rumex sanguineus L. extracts[J]. Asian Pac J Trop Bio 10, 172-82 (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

107.Gescher K, Hensel A, Hafezi W, Derksen A, Kühn J. Oligomeric proanthocyanidins from Rumex acetosa L. inhibit the attachment of herpes simplex virus type-1[J]. Antivir Res 89, 9-18 (2011) PubMed Google Scholar

-

108.Liu SX, Cheng LY. Exploitation actuality and expectation of Polygonum cuspidatum's effective ingredients[J]. Food Sci Tech 2, 96-8 (2004) PubMed Google Scholar

-

109.Ahmadi R, Ebrahimzadeh MA. Resveratrol-a comprehensive review of recent advances in anticancer drug design and development[J]. Eur J Med Chem (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

110.Li J, Zhang LS. Chemical constituents of n-butyl alcohol extract from Rumex hastatus roots[J]. Chin J Exp Tradit Med Formulae 21, 46-9 (2015) PubMed Google Scholar

-

111.Li YJ, Lu Y, Hou SQ, Ruan RS. A study of the lignan glycosides from Rumex hastatus[J]. J Yunnan Natl Univ 26, 438-42 (2017) PubMed Google Scholar

-

112.Chen JM, Dissertation, Heilongjiang Univ Chin Med, 2008. PubMed Google Scholar

-

113.Wang ZY, Zuo YM, Kang YH, Cong Y, Song XL. Study on the chemical constituents of the Rumex gmelini Turcz.(ÌⅠ)[J]. Chin Tradit Herbal Drugs 36, 1626-7 (2005) PubMed Google Scholar

-

114.Zhang LS, Li Z, Mei RQ, Liu GM, Long CL, Wang YH, Cheng YX. Hastatusides A and B: two new phenolic glucosides from Rumex hastatus[J]. Helv Chim Acta 92, 774-8 (2009) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

115.Islam MS, Iwasaki A, Suenaga K, Kato-Noguchi H. 2-Methoxystypandrone, a potent phytotoxic substance in Rumex maritimus L[J]. Theor Exp Plant Physiol 29, 195-202 (2017) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

116.Qiu YD, Li AD, Lee J, Lee JE, Lee EW, Cho N, Yoo HM. Inhibition of Jurkat T cell proliferation by active components of Rumex japonicus roots via induced mitochondrial damage and apoptosis promotion[J]. J Microbiol Biotechn 30, 1885-95 (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

117.Kuruuzum A, Demirezer LO, Bergere I, Zeeck A. Two new chlorinated naphthalene glycosides from Rumex patientia[J]. J Nat Prod 64, 688-90 (2001) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

118.Nishina A, Suzuki H. Naphthoquinone derivative of Rumex japonicus and Rheum as microbicide for foods[J]. Jpn Kokai Tokkyo Koho 4, 17 (1993) PubMed Google Scholar

-

119.Wei W, Dissertation, Hunan Univ Chin Med, 2012. PubMed Google Scholar

-

120.Demirezer O, Kuruuzum A, Bergere I, Schiewe HJ, Zeeck A. Five naphthalene glycosides from the roots of Rumex patientia[J]. Phytochemistry 56, 399-402 (2001) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

121.Jang DS, Kim JM, Kim JH, Kim JS. 24-Nor-ursane type triterpenoids from the stems of Rumex japonicus[J]. Chem Pharm Bull 53, 1594-6 (2005) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

122.Khetwal KS, Manral K. Pathak RP (1987) Constituents of the aerial parts of Rumex nepalensis Spreng[J]. Indian Drugs 24, 328-9 (1987) PubMed Google Scholar

-

123.Kengne IC, Feugap LDT, Njouendou AJ, Ngnokam CDJ, Djamalladine MD, Ngnokam D, Voutquenne-Nazabadioko L, Tamokou J-D-D. Antibacterial, antifungal and antioxidant activities of whole plant chemical constituents of Rumex abyssinicus[J]. BMC Complement Med Ther 21, 164 (2021) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

124.Santos ÊRM, Oliveira HNM, Oliveira EJ, Azevedo SHG, Jesus AA, Medeiros AM, Dariva C, Sousa EMBD. Supercritical fluid extraction of Rumex Acetosa L roots: yield, composition, kinetics, bioactive evaluation and comparison with conventional techniques[J]. J Supercrit Fluids 122, 1-9 (2017) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

125.Tutin F, Clewer WB. The constituents of Rumex Ecklonianus[J]. J Chem Soc 97, 1-11 (1910) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

126.Bélanger J, Balakrishna M, Latha P, Katumalla S, Johns T. Contribution of selected wild and cultivated leafy vegetables from South India to lutein and β-carotene intake[J]. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 19, 417-24 (2010) PubMed Google Scholar

-

127.Ito H. Effects of the antitumor agents from various natural sources on drug metabolizing system, phagocytic activity and complement system in Sarcoma 180-bearing mice[J]. Jpn J Pharm 40, 435-43 (1986) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

128.Taraskina KV, Chumbalov TK, Kuznetsova LK. Anthraquinone pigments of Rumex rechingerianus[J]. Chem Nat Compd 4, 162-3 (1968) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

129.Yuan Y, Chen WS, Yang YJ, Li L, Zhang HM. Anthraquinone components in Rumex patientia L[J]. Chin Tradit Herbal Drugs 31, 12-4 (2000) PubMed Google Scholar

-

130.Liu J, Xia ZT, Zhou GR, Zhang LL, Kong LY. Study on the chemical constituents of Rumex patientia[J]. J Chin Med Mater 34, 893-5 (2011) PubMed Google Scholar

-

131.Hasan A, Ahmed I, Khan MA. A new anthraquinone glycoside from Rumex chalepensis[J]. Fitoterapia 68, 140-2 (1997) PubMed Google Scholar

-

132.Wang HL, Wang L, Zhong GY, Liang WJ, Li X, Jiang K. Chemical constituents of Rumex nepalensis (Ⅱ)[J]. J Chin Med Mater 43, 1129-31 (2020) PubMed Google Scholar

-

133.Yang Y, Yan YM, Wei W, Jie L, Zhang LS, Zhou XJ, Wang PC, Yang YX, Cheng YX. Anthraquinone derivatives from Rumex plants and endophytic Aspergillus fumigatus and their effects on diabetic nephropathy[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 23, 3905-9 (2013) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

134.Shafiq N, Noreen S, Rafiq N, Ali B, Parveen S, Mahmood A, Sajid A, Akhtar N, Bilal M. Isolation of bioactive compounds from Rumex hastatus extract and their biological evaluation and docking study as potential anti-oxidant and anti-urease agents[J]. J Food Biochem (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

135.Bello OM, Fasinu PS, Bello OE, Ogbesejana A, Oguntoye OS. Wild vegetable Rumex acetosa Linn. : its ethnobotany, pharmacology and phytochemistry- a review[J]. S Afr J Bot 125, 149-60 (2019) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

136.Varma PN, Lohar DR, Satsangi AK. Phytochemical study of Rumex acetosa Linn[J]. J Indian Chem Soc 61, 171-2 (1984) PubMed Google Scholar

-

137.Zhang L, Dissertation, Xinjiang Univ, 2006. PubMed Google Scholar

-

138.Wang XL, Hu M, Wang S, Cheng YX. Phenolic compounds and steroids from Rumex patientia[J]. Chem Nat Compd 50, 311-3 (2014) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

139.Schmuch J, Beckert S, Brandt S, Lohr G, Hermann F, Schmidt TJ, Beikler T, Hensel A. Extract from Rumex acetosa L. for prophylaxis of periodontitis: inhibition of bacterial in vitro adhesion and of gingipains of Porphyromonas gingivalis by epicatechin-3-O-(4β→8)-epicatechin-3-O-gallate (procyanidin-B2-di-gallate)[J]. PLoS ONE (2015) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

140.Van den Berg AJJ, Labadie RP. The production of acetate derived hydroxyanthraquinones, -dianthrones, -naphthalenes and -benzenes in tissue cultures from Rumex alpinus[J]. Planta Med 41, 169-73 (1981) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

141.Zhou RH. Chemical taxonomy of medicinal plants. (Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Press, 1988). PubMed Google Scholar

-

142.Deng LN, Li BR, Wang R, Wang GW, Dong ZY, Liao ZH, Chen M. New napthalenone from roots of Rumex nepalensis[J]. China J Chin Mater Med 42, 3143-5 (2017) PubMed Google Scholar

-

143.Liang HX, Dai HQ, Fu HA, Dong XP, Adebayo AH, Zhang LX, Cheng YX. Bioactive compounds from Rumex plants[J]. Phytochem Lett 3, 181-4 (2010) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

144.Schwartner C, Wagner H, Christoffel V. Chemical and pharmacological investigations on Rumex acetosa L. Germany: The Second International Congress on Phytomedicine; 1996. PubMed Google Scholar

-

145.Elzaawely AA, Xuan TD, Tawata S. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Rumex japonicus Houtt. aerial parts[J]. Biol Pharm Bull 28, 2225-30 (2005) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

146.Tavares L, Carrilho D, Tyagi M, Barata D, Serra AT, Duarte CMM, Duarte RO, Feliciano RP, Bronze MR, Chicau P, Espírito-Santo MD, Ferreira RB, Santos CND. Antioxidant capacity of Macaronesian traditional medicinal plants[J]. Molecules 15, 2576-92 (2010) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

147.Kucekova Z, Mlcek J, Humpolicek P, Rop O, Valasek P. Phenolic compounds from Allium schoenoprasum, Tragopogon pratensis and Rumex acetosa and their antiproliferative effects[J]. Molecules 16, 9207-17 (2011) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

148.Orbán-Gyapai O, Liktor-Busa E, Kúsz N, Stefkó D, Urbán E, Hohmanna J, Vasasa A. Antibacterial screening of Rumex species native to the carpathian basin and bioactivity-guided isolation of compounds from Rumex aquaticus[J]. Fitoterapia 118, 101-6 (2017) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

149.Yang B, Zhao P, Xu CH, Ji Y. Study on non-anthraquinone chemical constituents of Rumex patientia seed[J]. Chin Tradit Patent Med 30, 262-3 (2008) PubMed Google Scholar

-

150.Gashaw N. Isolation, characterization and structural elucidation of the roots of Rumex nervosus[J]. J Trop Pharm Chem (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

151.Watanabe M, Miyagi A, Nagano M, Kawai-Yamada M, Imai H. Imai Characterization of glucosylceramides in the Polygonaceae, Rumex obtusifolius L[J]. injurious weed. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 75, 877-81 (2011) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

152.Nishina A, Kubota K, Osawa T. Antimicrobial components, trachrysone and 2-methoxystypandrone, in Rumex Japonicus Houtt[J]. J Agr Food Chem 41, 1772-5 (1993) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

153.Kim HY, Jee H, Yeom JH, Jeong HJ, Kim HM. The ameliorative effect of AST2017-01 in an ovalbumin-induced allergic rhinitis animal model[J]. Inflamm Res 68, 387-95 (2019) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

154.Chelly M, Chelly S, Occhiuto C, Cimino F, Cristani M, Saija A, Muscarà C, Ruberto G, Speciale A, Bouaziz-Ketata H, Siracusa L. Comparison of phytochemical profile and bioproperties of methanolic extracts from different parts of Tunisian Rumex roseus[J]. Chem Biodivers (2021) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

155.Yang HR, Lee H, Kim JH, Hong IH, Hwang DH, Rho IR, Kim GS, Kim E, Kang C. Therapeutic effect of Rumex japonicus Houtt. on DNCB-induced atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in balb/c mice and human keratinocyte HaCaT cells[J]. Nutrients 11, 573 (2019) PubMed Google Scholar

-

156.Kim HY, Jeon H, Bae CH, Lee Y, Kim H, Kim S. Rumex japonicus Houtt. alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by protecting tight junctions in mice[J]. Integr Med Res (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

157.Eom T, Kim E, Kim JS. In vitro antioxidant, antiinflammation, and anticancer activities and anthraquinone content from Rumex crispus root extract and fractions[J]. Antioxidants (Basel) (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

158.Dóra R, Kúsz N, Rafai T, Bogdanov A, Burián K, Csorba A, Mándi A, Kurtán T, Vasas A, Hohmann J. 14-Noreudesmanes and a phenylpropane heterodimer from sea buckthorn berry inhibit Herpes simplex type 2 virus replication[J]. Tetrahedron 75, 1364-70 (2019) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

159.Han JH, Khin PP, Sohn UD. Effect of Rumex aquaticus herba extract against helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation in gastric epithelial cells[J]. J Med Food 19, 31-7 (2016) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

160.Min YS, Lee SE, Hong ST, Kim HS, Choi BC, Sim SS, Whang WK, Sohn UD. The inhibitory effect of quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucuronopyranoside on gastritis and reflux esophagitis in rats[J]. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 13, 295-300 (2009) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

161.Cho EJ, Um SI, Han JH, Kim B, Han SB, Jeong JH, Kim HR, Kim I, Whang WK, Lee E, Sohn UD. The cytoprotective effect of Rumex aquaticus Herba extract against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in AGS cells[J]. Arch Pharm Res 39, 1739-47 (2016) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

162.Jang HS, Han JH, Jeong JY, Sohn UD. Protective effect of ECQ on rat reflux esophagitis model[J]. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 16, 455-62 (2012) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

163.Wang JF, Wang JX, Xu YZ, Zhao XY, Liu Y. Extraction technology of total phenols from Rumex acetosa L. and its scavenging activity to DPPH free radicals[J]. Medicinal Plant 6, 51-5 (2015) PubMed Google Scholar

-

164.Litvinenko YA, Muzychkina RA. New antioxidant phytopreparation from Rumex thyrsiflorus roots Ⅲ[J]. Chem Nat Compd 44, 239-40 (2008) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

165.Feduraev P, Chupakhina G, Maslennikov P, Tacenko N, Skrypnik L. Variation in phenolic compounds content and antioxidant activity of different plant organs from Rumex crispus L. and Rumex obtusifolius L. at different growth stages[J]. Antioxidants (Basel) (2019) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

166.Nisa H, Kamili AN, Bandh SA, Shajrul A, Lone BA, Parray JA. Phytochemical screening, antimicrobial and antioxidant efficacy of different extracts of Rumex dentatus L. —a locally used medicinal herb of Kashmir Himalaya[J]. Asian Pac J Trop Dis 3, 434-40 (2013) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

167.Younes KM, Romeilah RM, El-Beltagi HS, El Moll H, Rajendrasozhan S, El-Shemy HA, Shalaby EA. In-vitro evaluation of antioxidant and antiradical potential of successive extracts, semi-purified fractions and biosynthesized silver nanoparticles of Rumex vesicarius[J]. Not Bot Horti Agrobo (2021) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

168.Ozenver N, Guvenalp Z, Kuruuzum-Uz A, Demirezer LO. Inhibitory potential on key enzymes relevant to type Ⅱ diabetes mellitus and antioxidant properties of the various extracts and phytochemical constituents from Rumex acetosella L[J]. J Food Biochem (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

169.Uzun M, Demirezer LO. Anti-aging power of Rumex crispus L. : matrixmetalloproteinases inhibitor, sun protective and antioxidant[J]. S Afr J Bot 124, 364-71 (2019) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

170.Cebovic T, Jakovljevic D, Maksimovic Z, Djordjevic S, Jakovljevic S, Cetojevic-Simin D. Antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of curly dock (Rumex crispus L., Polygonaceae) fruit extract[J]. Vojnosanit Pregl 77, 308-16 (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

171.Lajter I, Zupkó I, Molnár J, Jakab G, Balogh L, Vasas A, Hohmann J. Antiproliferative activity of Polygonaceae species from the Carpathian Basin against human cancer cell lines[J]. Phytother Res 27, 77-85 (2013) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

172.Tukappa NKA, Londonkar RL, Nayaka HB, Kumar CBS. Cytotoxicity and hepatoprotective attributes of methanolic extract of Rumex vesicarius L[J]. Biol Res 48, 19 (2015) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

173.Aghajanyan A, Nikoyan A, Trchounian A. Biochemical activity and hypoglycemic effects of Rumex obtusifolius L. seeds used in Armenian traditional medicine[J]. Biomed Res Int (2018) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

174.Qamar HM, Qayyum R, Salma U, Khan S, Khan T, Shah AJ. Vascular mechanisms underlying the hypotensive effect of Rumex acetosa[J]. Pharm Biol 56, 225-34 (2018) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

175.Zhou XB, Cao KW, Song LK, Kou SQ, Qu SC, Wang C, Yu Y, Liu Y, Li PY, Lu RP. Effect of acetone extract of Rumex japonicas Houtt on hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis in rat myocardial cells[J]. Trop J Pharm Res 16, 135-40 (2017) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

176.Jeong D, Irfan M, Lee DH, Hong SB, Oh JW, Rhee MH. Rumex acetosa modulates platelet function and inhibits thrombus formation in rats[J]. BMC Complement Med Ther (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

177.Ahn JH, Kim J, Rehman NU, Kim HJ, Ahn MJ, Chung HJ. Effect of Rumex acetosa extract, a herbal drug, on the absorption of fexofenadine[J]. Pharmaceutics (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

178.Shim KS, Lee B, Ma JY. Water extract of Rumex crispus prevents bone loss by inhibiting osteoclastogenesis and inducing osteoblast mineralization[J]. BMC Complement Altern Med 17, 483 (2017) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

179.Idris OA, Wintola OA, Afolayan AJ. Comparison of the proximate composition, vitamins (ascorbic acid, alpha-tocopherol and retinol), anti-nutrients (phytate and oxalate) and the GC-MS analysis of the essential oil of the root and leaf of Rumex crispus L. Plants. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8030051 PubMed Google Scholar

-

180.Minh TN, Van TM, Andriana Y, Vinh LT, Hau DV, Duyen DH, de Guzman-Gelani C. Antioxidant, xanthine oxidase, alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activities of bioactive compounds from Rumex crispus L. root. Molecules. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24213899 PubMed Google Scholar

-

181.Colon-Gonzalez F, Kim GW, Lin JE, Valentino MA, Waldman SA. Obesity pharmacotherapy: what is next[J]. Mol Aspects Med 34, 71-83 (2013) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

182.George G, Sengupta P, Paul AT. Optimisation of an extraction conditions for Rumex nepalensis anthraquinones and its correlation with pancreatic lipase inhibitory activity. J Food Compos Anal. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2020.103575 PubMed Google Scholar

-

183.El-Kashak WA, Elshamy AI, Mohamed TA, El Gendy AE-NG, Saleh IA, Umeyama A. Rumpictuside A: unusual 9, 10-anthraquinone glucoside from Rumex pictus Forssk[J]. Carbohydr Res 448, 74-8 (2017) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

184.Tiwari RD, Sinha KS. Chemical examination of Rumex hastatus D. Don[J]. Indian J Chem 19B, 531-2 (1980) PubMed Google Scholar

-

185.Halim AF, Fattah HA, EI-Gamal AA. Anthraquinones and flavonoids of Rumex vesicarius. Annual Conference of the Arab Society of Medicinal Plants Research, National Research Centre, Cairo; 1989. PubMed Google Scholar

-

186.Mhalla D, Bouaziz A, Ennouri K, Chawech R, Smaoui S, Jarraya R, Tounsi S, Trigui M. Antimicrobial activity and bioguided fractionation of Rumex tingitanus extracts for meat preservation[J]. Meat Sci 125, 22-9 (2017) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

187.Choe SG, Hwang BY, Kim MS, Oh G-J, Lee KS, Ro JS. Chemical components of Rumex acetosella L[J]. Saengyak Hakhoechi 29(3), 209-16 (1998) PubMed Google Scholar

-

188.Zaghloul MG, El-Fattah HA. Anthraquinones and flavonoids from Rumex tingitanus growing in Libya[J]. Zagazig J Pharm Sci 8(2), 54-8 (1999) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

189.Khetwal KS, Manral K, Pathak RP. Constituents of the aerial parts of Rumex nepalensis Spreng[J]. Indian Drugs 24, 328-9 (1987) PubMed Google Scholar

-

190.Wang ZY, Cai XQ, Kang YH, Wei F. Structure of two compounds from the root of Rumex gmelini[J]. Chin Tradit Herbal Drugs 27(12), 714-6 (1996) PubMed Google Scholar

-

191.Verma KK, Gautam RK, Choudhary A, Gupta GD, Singla S, Goyal S. A review on ethnobotany, phytochemistry and pharmacology on Rumex hastatus[J]. Res J Pharm and Tech 13(8), 3969-76 (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

192.Nedelcheva A. An ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Bulgaria[J]. EurAsia J Biosci 7, 77-94 (2013) PubMed Google Scholar

-

193.Harshaw D, Nahar L, Vadla B, Saif-E-Naser GM, Sarker SD. Bioactivity of Rumex obtusifolius (Polygonaceae)[J]. Arch Biol Sci 62, 387-92 (2010) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

194.Duke J. Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases. http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/duke/ethnobot.pl?ethnobot.taxon=Rumex%20.obtusifolius. Accessed 20 Mar 2022. PubMed Google Scholar

-

195.Paniagua-Zambrana NY, Bussmann RW, Echeverria J. Rumex acetosella L. Rumex crispus L. Rumex cuneifolius Campd. Polygonaceae. Ethnobot Andes. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77093-2_255-1 PubMed Google Scholar

-

196.Dabe NE, Kefale AT, Dadi TL. Evaluation of abortifacient effect of Rumex nepalensis Spreng among pregnant swiss albino rats: laboratory-based study[J]. J Exp Pharm 12, 255-65 (2020) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

197.Pareek A, Kumar A. Rumex crispus L. A plant of traditional value[J]. Drug Discov 9(20), 20-3 (2014) PubMed Google Scholar

-

198.Sõukand R, Pieroni A. The importance of a border: Medical, veterinary, and wild food ethnobotany of the Hutsuls living on the Romanian and Ukrainian sides of Bukovina[J]. J Ethnopharmacol 185, 17-40 (2016) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

199.Yang J, Luo JF, Gan QL, Ke LY, Zhang FM, Guo HR, Zhao FW, Wang TH. An ethnobotanical study of forage plants in Zhuxi County in the Qinba mountainous area of central China[J]. Plant Divers 43(3), 239-47 (2021) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-

200.Svanberg I. The use of wild plants as food in pre-industrial Sweden[J]. Acta Soc Bot Pol 81(4), 317-27 (2012) CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

-