2. 暨南大学, 中药及天然药物 研究所, 广东 广州 510632;

3. 暨南大学, 广东省中药药效物质基础及创新药物研究重点实验室, 广东 广州 510632

2. Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Natural Products, Jinan University, Guangzhou 510632, China;

3. Guangdong Province Key Laboratory of Pharmacodynamic Constituents of TCM and New Drugs Research, Jinan University, Guangzhou 510632, China

磷脂是组成生物膜的主要成分, 分为甘油磷脂(由甘油构成) 与鞘磷脂(由神经鞘氨醇构成) 两大类, 本文讨论的磷脂均指甘油磷脂, 是一种含有磷酸基团的两亲性脂质分子, 由甘油骨架、脂肪酸和磷酸盐基团组成。脂肪酸与甘油sn-1和sn-2位置的羟基结合形成磷脂的疏水尾部, 磷酸盐基团则位于甘油的sn-3位置, 形成磷脂的亲水头部。哺乳动物细胞中存在上百种磷脂, 根据脂肪酸与甘油骨架sn-1连接的方式分类, 醚键连接的为醚磷脂, 乙烯醚键连接的为缩醛磷脂。根据磷酸盐基团的差异, 可将磷脂分为磷脂酰乙醇胺(phosphatidyl ethanolamine, PE)、磷脂酰胆碱(phosphatidylcholine, PC) 等类别。此外, 脂肪酸长度和饱和度的差异则进一步丰富了磷脂的种类[1, 2]。

一般认为, 细胞中磷脂的代谢依赖于4个过程: 生物合成、重塑、降解和胞内转运[2]。Kennedy[3]在1961年首次阐释了磷脂分子的从头合成途径, 被认为是脂质生物化学的里程碑事件。但磷脂中的脂肪酰基链具有高度的多样化和不对称分布, 而从头合成途径中的酶几乎没有酰基辅酶A (acyl-CoA) 底物的特异性, 该途径产生的磷脂大多sn-1和sn-2位置为饱和/单不饱和脂肪酸[4], 因此这种分布不能完全用从头合成来解释。实际上, 早在1958年, Lands[5]通过14C示踪实验发现合成PC的标记脂肪酸与甘油的比值远远高于甘油三酯中该比值, 之后的研究证明这一现象是由于磷脂中脂肪酸的快速周转[6]。因此, 生物膜的磷脂是具有代谢活性的, 在从头合成之后还存在着脂肪酸链的重塑, 即磷脂sn-2位置上的饱和/单不饱和脂肪酸被多不饱和脂肪酸(polyunsaturated fatty acid, PUFA) 取代, 形成不饱和度更高的新的磷脂。重塑反应包括两个步骤: 磷脂去酰化(deacylation) 水解为溶血磷脂, 后者再酰化(reacylation) 合成新的磷脂, 这个过程也叫做Lands循环[5]。

由于从头合成途径中的酰基转移酶底物特异性差, 因此新合成的磷脂需要经过重塑过程进一步修饰, 才能转变为具有特定活性和功能的成熟磷脂[7]。作为细胞质膜的基本组成成分, 磷脂的脂肪酰链的构成会影响生物膜的物理性质、动力学及膜相关蛋白的完整性, 并影响囊泡转运、信号转导等一系列细胞生物学过程[8, 9]。越来越多的研究显示, 磷脂重塑过程与神经退行性疾病如帕金森病的发生和进展相关。

2009年, 编码与磷脂重塑有关的钙非依赖磷脂酶A2β (calcium independent group VIA phospholipase A2, iPLA2β) 的基因PLA2G6被确定为遗传性帕金森综合症14型的致病基因[10]。PLA2G6突变导致的早发型帕金森病发病时间中位数为23岁, 症状包括运动僵硬、肌张力障碍、共济失调、精神病和智力障碍等[10, 11]。作为磷脂重塑关键酶, iPLA2β缺乏会改变小鼠脂质代谢相关酶表达并重整大脑磷脂脂肪酸[12]。果蝇iPLA2β同源物iPLA2-VIA丢失可通过缩短磷脂乙酰链而促进帕金森病标志物α-突触核蛋白(α-synuclein, α-Syn) 聚集体的形成[13]。除了iPLA2β, 磷脂酶家族的其他成员及具有磷脂酶A2活性的过氧化物酶6 (peroxiredoxin 6, PRDX6) 也被报道通过调节Parkin通路参与帕金森病的疾病进程[14, 15]。另有学者证明了参与心磷脂(cardiolipin, CL) 再酰化反应的酰基辅酶A溶血心磷脂酰基转移酶1 (lysocardiolipin acyltransferase 1, ALCAT1) 影响线粒体以及α-Syn聚集体形成, 因此可以作为新型的帕金森病药物靶标[16]。在鱼藤酮诱导的帕金森模型小鼠脑组织中, 氧化磷脂的堆积也提示磷脂重塑是参与帕金森病发生发展的不可低估的内在分子机制[17]。在此, 本文综述了目前国内外对磷脂重塑可能参与帕金森病发病及进展的各方观点, 深入讨论了在二者关系中涉及的潜在的分子信号和相互作用的机制, 以期为帕金森病的防治策略和靶向药物开发提供全新的思路。

1 磷脂重塑的关键步骤磷脂酶脂肪酸首先通过从头合成途径插入磷脂, 之后, 磷脂在磷脂酶A2 (phospholipase A2, PLA2) 的作用下水解生成游离脂肪酸和溶血磷脂, 即去酰化反应, 此时, 另外一个脂肪酸与溶血磷脂在相应酶的催化下生成新的磷脂, 即再酰化反应。这一过程就是磷脂重塑, 也被称为Lands循环[5]。

1.1 去酰化反应在第一步去酰化反应中, 磷脂酶A1 (phospholipase A1, PLA1) 和PLA2分别参与sn-1和sn-2的脂肪酸去酰化, 但有部分PLA2也可参与sn-1的去酰化[18]。在磷脂去酰化生成溶血磷脂的过程中, 由于PLA1和PLA2的作用特点, 使得sn-1和sn-2位置的脂肪酸都可以被更新。分泌型PLA2 (secreted PLA2, sPLA2) 家族成员sPLA2-III被认为参与精子膜磷脂重塑, 后者是精子运动的必要条件[19]。有证据显示, 钙非依赖磷脂酶A2 (Ca2+-independent PLA2, iPLA2) 参与重塑反应, 以iPLA2β和iPLA2γ报道最多[20]。

早在1986年, Chilton等[21]在小鼠淋巴样瘤细胞P388D1中发现, 抑制iPLA2β活性可影响花生四烯酸(arachidonic acid, AA) 而非棕榈酸插入溶血磷脂, 首次论证了iPLA2β在磷脂重塑中的关键角色。iPLA2β可以切除CL中氧化的PUFA, 产生的单溶血心磷脂(monolysocardiolipin, MLCL) 与未被氧化的acyl-CoA反应产生新的CL, 进一步提示iPLA2β可能优先参与不饱和磷脂的重塑过程[22]。此外, iPLA2β缺失会提高磷脂中短链脂肪酸的比例, 增加氧化磷脂水平, 进而降低膜的稳定性[13]。与iPLA2β一样, iPLA2γ通过产生能与acyl-CoA结合的溶血磷脂调控和维持细胞膜磷脂的稳态[23]。iPLA2γ可能参与含AA的PE在细胞过氧化物酶体中的富集, 并负责调节线粒体和过氧化物酶体膜磷脂的重塑过程[23]。

1.2 再酰化反应磷脂重塑第二步是溶血磷脂的再酰化反应, 根据脂肪酸来源和是否依赖CoA, 分为3种类型: 依赖acyl-CoA型、依赖CoA型和不依赖CoA型[24]。

依赖acyl-CoA型反应涉及到酰基辅酶A: 溶血磷脂酰基转移酶(acyl-CoA: lysophospholipid acyltransferases) 选择性将饱和脂肪酸插入2-酰基-溶血磷脂的sn-1位置, 而将PUFA插入1-酰基-溶血磷脂的sn-2位置[25]。值得注意的是, 该重塑反应需要消耗ATP将脂肪酸转化为其活化形式acyl-CoA。此外, 这些酶可能与产生溶血磷脂的磷脂酶A偶联, 共同参与磷脂的更新。

依赖CoA的转酰基反应包括不依赖ATP的脂肪酸acyl-CoA的合成及酰基辅酶A: 溶血磷脂酰基转移酶催化新合成的脂肪酸acyl-CoA插入溶血磷脂受体。该过程没有游离脂肪酸产生, 不消耗ATP, 但需要生理浓度的CoA参与反应。依赖CoA的转酰基反应活性广泛分布于各种组织和细胞的微粒体中, 如肝[26]、巨噬细胞[27]、血小板[28]和脑[29]。

不依赖CoA的转酰基反应催化脂肪酸从二酰基磷脂转移到各种溶血磷脂, 不需要CoA作为辅助因子。不依赖CoA的转酰基反应的活性与含醚键磷脂的分布密切相关, 这种转酰基反应被认为对于PUFA在含醚键磷脂的分布中非常重要[24]。不依赖CoA的转酰基反应活性首先在人血小板中发现, 在包括巨噬细胞[27]、中性粒细胞[21]、脑[30]、心脏[31]在内的哺乳动物组织和细胞的微粒体中也发现了类似的酶活性。

不依赖CoA的转酰基反应活性存在于微粒体中, 是不依赖Ca2+的, 但分子机制尚不明确。Yamashita等[24]认为膜结合和iPLA2可能参与这种转酰化系统。

磷脂重塑的前提是磷脂合成, 磷脂酸(phosphatidic acid, PA) 来源的1, 2-二酰基甘油(diacylglycerol, DAG) 和胞苷二磷酸-二酰基甘油(cytidine diphosphate diacylglycerol, CDP-DAG) 是磷脂合成的基本需要。乙醇胺(ethanolamine) 先活化为胞苷二磷酸乙醇胺(cytidine diphosphate-ethanolamine, CDP-Etn), 继而与DAG缩合, 可形成PE。PC的合成与PE的合成非常相似, 胆碱(choline) 活化成胞苷二磷酸胆碱(cytidine diphosphate-choline, CDP-Cho), 与DAG缩合形成PC。PE三次甲基化也可以形成PC。以PC和PE为底物, 通过极性头交换可形成磷脂酰丝氨酸(phosphatidylserines, PS), 后者脱羧又可转变为PE。磷脂酰肌醇(phosphatidylinositol, PI) 是肌醇(inositol) 缩合到CDP-DAG而形成的。磷脂酰甘油(phosphatidylglycerol, PG) 的合成首先需要CDP-DAG与甘油-3-磷酸(glycerol-3-phosphate, G-3-P) 生成磷脂酰甘油-3-磷酸(phosphatidylglycerol-3-phosphate, PGP), 后者脱磷酸生成PG。CL是线粒体功能所需的关键磷脂, 由CDP-DAG与PG通过心磷脂合酶缩合而成[32-34]。

2 磷脂重塑酶与帕金森病磷脂重塑通过调节磷脂脂肪链的构成, 影响质膜的生理特性、细胞信号传导及后续的细胞生物学过程。参与重塑过程的酶在细胞和组织中的差异性表达可能是导致不同组织中磷脂种类多样性的原因, 而这些重塑相关酶功能的缺失或异常也可能是不同疾病特征和病理进展的内在因素。最新的证据表明, 磷脂重塑反应参与了帕金森病的发生发展, 研究者通过构建果蝇、小鼠等动物模型提出了磷脂重塑参与帕金森病的多种机制。临床数据显示, 帕金森病患者大脑中壳核钙依赖性的PLA2活性显著上升[35]。脂蛋白相关的PLA2 (lipoprotein-related phospholipase A2, Lp-PLA2) 被报道为帕金森病的重要风险因素之一[36]。去酰化产物AA与磷酸化的胞浆型PLA2 (cytosolic PLA2, cPLA2) 水平的升高与帕金森病小鼠模型的多巴胺能神经元退行有关[37]。不仅如此, 编码iPLA2β的PLA2G6基因突变被确定与早发性帕金森病直接相关[10]。PRDX6被报道具有PLA2和溶血磷脂酰胆碱酰基转移酶(lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase, LPCAT) 活性[38], 但其在帕金森病中的作用仍有争议。

2.1 iPLA2β与帕金森病PLA2G6编码参与细胞磷脂重塑的iPLA2β。PLA2G6突变与婴儿神经轴索营养不良(infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy, INAD)、伴脑铁积累的神经退行性疾病(neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation, NBIA) 以及肌张力障碍-帕金森综合征(dystonia-parkinsonism) 有关, 这些神经退行性疾病统称为磷脂酶A2相关性神经变性病[39, 40]。但PLA2G6突变引发神经退行性疾病的具体分子机制目前仍不明确。

近些年来, 研究者们构建了PLA2G6敲除和多种突变的动物模型来探索其引发帕金森病的内在机制。果蝇模型中人类PLA2G6同源物iPLA2-VIA的丢失不影响脑组织磷脂的组成, 但会损伤逆转录酶的功能, 并导致神经酰胺增加, 影响膜流动性的正反馈回路从而损害神经元, 使得果蝇寿命严重缩短, 同时出现氧化应激易感及神经退行发展等病理表型[41], 行为学方面表现出与年龄相关的攀爬和自主运动的缺陷等运动协调障碍[42]。果蝇模型中PUFA的补充可以缓解iPLA2-VIA缺失所导致的上述病理学和行为学损伤[43], 提示恢复磷脂重塑过程可能保护神经元功能。

在斑马鱼模型中, PLA2G6缺失会导致多巴胺能神经元死亡和α-Syn表达增加等一系列帕金森病样症状[44]。对斑马鱼PLA2G6突变模型进行代谢组学分析的结果显示更高水平的磷脂和更低水平的二十二碳六烯酸(docosahexaenoic acid, DHA), 而外源性补充DHA可以改善运动异常[45]。体内动力学研究表明, 小鼠iPLA2β缺乏会改变脂质代谢相关酶表达并重整大脑磷脂脂肪酸含量[12]。这些证据均表明, 磷脂重塑失调是帕金森病的重要病理因素。

本课题组前期已经发现, 磷脂过氧化是包括帕金森病在内的神经退行性疾病易感的关键因素[46], 最近的一项研究证明PLA2G6突变导致过氧化磷脂的积累, 使细胞对铁死亡易感性增加, 从而引发帕金森病[17]。铁死亡是近10年提出的一种区别于凋亡或坏死的程序性细胞死亡方式, 其典型特征是铁负荷和过氧化磷脂的积累[47]。铁死亡可能是联系PLA2G6失调与帕金森病发病的关键机制, 但仍有待进一步探究。

iPLA2β的磷脂膜修复和重塑的蛋白活性对保护神经元的线粒体等细胞器免受氧化损伤至关重要。功能正常的iPLA2β可阻止线粒体膜电位的丧失和活性氧的产生, 减少细胞色素c和凋亡诱导因子的释放, 维持Ca2+稳态[48]。另一方面, 线粒体内膜含有高比例的不饱和心磷脂, 其富含的双烯丙基碳结构容易受到活性氧攻击, 进而导致包括凋亡在内的下游致病性信号级联反应[39]。这也可以解释为什么PLA2G6突变会引起线粒体功能障碍、内质网应激升高、线粒体自噬功能受损和转录异常等一系列细胞损伤, 并最终导致黑质致密部多巴胺能神经元退行性病变[49]。已有研究证明PLA2G6敲除的小鼠出现线粒体内膜和突触前膜缺陷的表型, 引发神经元树突末端降解和轴突退化, 最终引发帕金森病样行为学和病理学症状[50]。

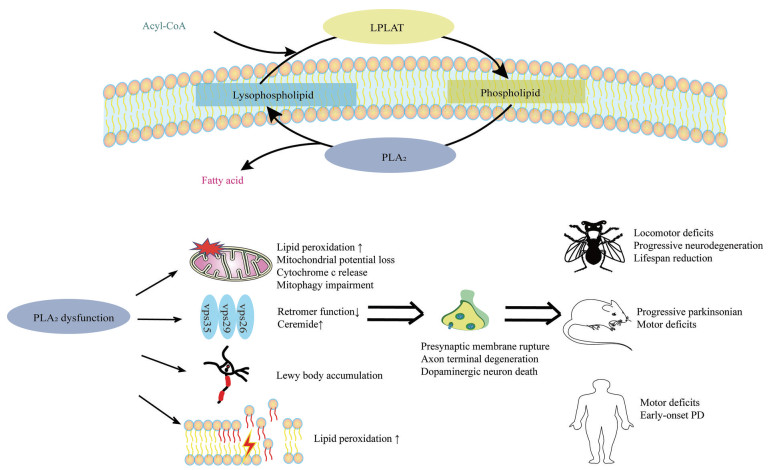

除了通过磷脂重塑障碍损伤神经元细胞膜磷脂, PLA2G6突变致病机制也可能与主要成分为α-Syn的路易小体(Lewy body, LB) 病理形成有关。临床数据显示, 肌张力障碍-帕金森综合征表型相关的PLA2G6突变的帕金森病患者的大脑存在广泛的α-Syn阳性的LB[51]。对果蝇模型的研究显示, iPLA2β的丢失确实会促进α-Syn的聚集[13]。PLA2G6敲除的小鼠神经元中同样存在α-Syn表达水平的升高, 可能是神经元对PLA2G6缺乏的一种适应性反应。该模型出现线粒体膜的降解, 并且α-Syn与受损线粒体膜具有强烈亲和力[52], 除了解释为α-Syn具有神经毒性作用, 也不能排除这是维持线粒体膜稳态的一种存活机制。总之, 现有进展提示PLA2G6与LB病理形成存在必然关联, 但对其扮演的角色及调控的方向目前仍有争议(图 1)。

|

Figure 1 Involvement of phospholipid remodeling in PD. PLA2 acts as a key regulator of phospholipid remodeling by catalyzing the hydrolysis of the sn-2 position of membrane glycerophospholipids to liberate fatty acids. The same reaction also produces lysophosholipids, which may receive a new PUFA through LPLAT closing the Lands' cycle. PLA2 manifests specific roles by expressing a variety of activities at the plasma membrane and mitochondria. When the expression and/or activity are dysregulated, PLA2 can be detrimental and lead to multiple disorders, which develop early-onset PD and PD-like phenotype in the model of Drosophila and mouse. PD: Parkinson's disease; PLA2: Phospholipase A2; PUFA: Polyunsaturated fatty acid; LPLAT: Lysophospholipid acyltransferase |

PRDX6是抗氧化物酶家族中唯一只含单个半胱氨酸残基的成员, 通常利用谷胱甘肽催化氧化还原反应。PRDX6一方面可以水解磷脂的sn-2位置, 该活性类似iPLA2[53, 54]; 另一方面可以利用游离脂肪酸来酰化溶血磷脂酰胆碱, 类似LPCAT的活性[55], 上述两种活性提示PRDX6可能在磷脂重塑过程中发挥双重作用[56], 共同维持磷脂的重塑过程。PRDX6广泛分布于大脑尤其是星形胶质细胞中[57], 提示其在脑生理中充当重要角色。尽管PRDX6早已被报道是阿尔茨海默症[58, 59]、大脑缺血再灌注炎症损伤[60]等疾病的潜在治疗靶点, 然而PRDX6在帕金森病病理进程中的作用并未得到足够明确的描述。

现有研究发现, 帕金森病和路易体痴呆患者大脑神经元出现α-Syn和PRDX6的增加, 并且表达PRDX6的星形胶质细胞也相应增多。由于研究者发现PRDX6的分布定位在LB核心, 因此阐释其神经保护机制可能与结合α-Syn并降低磷脂过氧化物有关[61], 但证据并不充分。另一方面, 在1-甲基-4-苯基-1, 2, 3, 6-四氢吡啶(1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetmhydropyridine, MPTP) 小鼠模型中发现, PRDX6过表达可诱导原代培养星形胶质细胞的活化, 增加促炎细胞因子、4-羟基壬烯醛(4-hydroxynonenal, 4-HNE) 的水平, 导致小鼠多巴胺能神经元丢失与行为障碍的恶化[15]。因此就现有的数据看来, 除了上述两种活性, PRDX6在帕金森病或其他神经退行性疾病中可能发挥其他未知的复杂功能。

与iPLA2β相似, PRDX6可以通过线粒体功能障碍和氧化损伤等机制参与帕金森病病理发展。作为PINK1-Parkin通路的上游, PRDX6对于线粒体清除的起始非常重要[62]。在帕金森病相关基因Parkin敲除的小鼠模型中, 包括黑质在内的中脑腹侧的PRDX6表达显著减少[63]。体外蛋白组学分析也显示了类似的结果[64]。

2.3 其他磷脂重塑相关酶与帕金森病iPLA2γ与iPLA2β同属iPLA2家族。研究显示, 大鼠iPLA2γ功能降低导致多巴胺及其代谢物水平降低并出现帕金森病样症状, 对鱼藤酮诱导的氧化应激也更加敏感。iPLA2γ活性的降低可能引起脂质过氧化和线粒体膜缺陷, 造成细胞色素c的释放, 最终导致神经细胞凋亡和神经退行[14]。在人神经纤维母瘤细胞上过表达α-Syn会诱导iPLA2和cPLA2的激活, 增加对游离脂肪酸的水解, 进而参与包含甘油三酯在内的脂滴的形成, 这种脂质调节机制可以解释为一种抗α-Syn毒性的细胞保护作用[65]。

相较于催化磷脂去酰化的iPLA2, 有关溶血磷脂的再酰化反应酶与帕金森病的关系报道很少。近期有一项研究报道了ALCAT1参与线粒体标志性磷脂心磷脂的重塑, 该研究认为ALCAT1基因学或药理学的抑制可能通过改善线粒体功能或促进线粒体自噬而缓解MPTP诱导的神经细胞毒性和运动能力损伤。此外, MPTP和α-Syn病理会导致ALCAT1的上调, 而敲除ALCAT1可以抑制α-Syn的寡聚和磷酸化[16]。

3 总结与展望大脑黑质致密部多巴胺能神经元退行性病变是帕金森病最显著的特征, 许多证据提出, 氧化应激损伤可能是关键的病理过程, 体现在帕金森病患者黑质中脂质和DNA氧化产物水平升高、谷胱甘肽水平降低等多个方面。早在2001年, 即有学者提出PLA2通过与氧化磷脂的高度亲和性定位去除有毒的氧化磷脂, 而PLA2活性的降低可能削弱神经元对氧化损伤的有效处理能力, 也是帕金森病中神经元对氧化损伤敏感的原因之一[35]。心磷脂是线粒体特征性磷脂, 为膜结构、呼吸动力学和线粒体自噬所必需[66]。磷脂重塑相关酶如iPLA2γ、iPLA2β及ALCAT1等, 可能通过调节心磷脂稳态, 从而保护神经元线粒体免受氧化应激损伤。许多研究以此为基础来解释线粒体功能障碍在帕金森病中的分子机制, 包括线粒体膜受损、呼吸链抑制、酶活性降低、能量代谢障碍等。此外, 帕金森病LB学说里也涉及磷脂重塑过程间接参与帕金森病进程的潜在机制。一方面, 磷脂重塑过程中动态变化的脂肪酸与磷脂可直接与α-Syn相互结合, 调节蛋白的低聚化和LB的形成[67]; 另一方面, α-Syn过表达可激活iPLA2和cPLA2的蛋白活性以抵抗α-Syn的毒性, 引起游离脂肪酸水平的升高, 以及甘油三酯和胆固醇合成的增加, 并最终导致脂滴积累[65]。

iPLA2β是维持细胞磷脂重塑功能的必需蛋白之一, 与帕金森病关系最密切, 虽然大量研究报道干预iPLA2β介导的磷脂重塑是治疗帕金森病的重要策略, 但至今仍未有靶向iPLA2β的药物上市, 迄今开发的一些以(S)-BEL和FKGK18为代表的iPLA2β抑制剂也只是作为疾病机制研究的工具药物。其临床应用受阻的原因主要是PLA2家族亚型众多, 几种不同的亚型具有相似催化活性, iPLA2β特异性参与帕金森病的根本性机制仍然需要进一步研究。

就目前的进展来看, 磷脂重塑相关蛋白具备开发为帕金森病治疗的新型靶点的潜力, 阐明磷脂重塑过程在帕金森病发病机制中的角色可能为帕金森病治疗药物的研发提供重要的理论依据。

作者贡献: 王萌完成文献的查阅和整理、起草文稿; 段文君完善内容和修改稿件; 李怡芳和栗原博提供了改进建议; 段文君和何蓉蓉为文章提供总指导和思路。

利益冲突: 所有作者均声明无利益冲突。

| [1] |

Robichaud PP, Boulay K, Munganyiki JE, et al. Fatty acid remodeling in cellular glycerophospholipids following the activation of human T cells[J]. J Lipid Res, 2013, 54: 2665-2677. DOI:10.1194/jlr.M037044 |

| [2] |

Hermansson M, Hokynar K, Somerharju P. Mechanisms of glycerophospholipid homeostasis in mammalian cells[J]. Prog Lipid Res, 2011, 50: 240-257. DOI:10.1016/j.plipres.2011.02.004 |

| [3] |

Kennedy EP. Biosynthesis of complex lipids[J]. Fed Proc, 1961, 20: 934-940. |

| [4] |

Yamashita A, Hayashi Y, Matsumoto N, et al. Coenzyme-A-independent transacylation system; possible involvement of phospholipase A2 in transacylation[J]. Biology (Basel), 2017, 6: 23. |

| [5] |

Lands WE. Metabolism of glycerolipides; a comparison of lecithin and triglyceride synthesis[J]. J Biol Chem, 1958, 231: 883-888. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)70453-5 |

| [6] |

Wang LP, Shen WY, Kazachkov M, et al. Metabolic interactions between the Lands cycle and the Kennedy pathway of glycerolipid synthesis in arabidopsis developing seeds[J]. Plant Cell, 2012, 24: 4652-4669. DOI:10.1105/tpc.112.104604 |

| [7] |

Wang B, Tontonoz P. Phospholipid remodeling in physiology and disease[J]. Annu Rev Physiol, 2019, 81: 165-188. DOI:10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114444 |

| [8] |

Holthuis JC, Menon AK. Lipid landscapes and pipelines in membrane homeostasis[J]. Nature, 2014, 510: 48-57. DOI:10.1038/nature13474 |

| [9] |

Antonny B, Vanni S, Shindou H, et al. From zero to six double bonds: phospholipid unsaturation and organelle function[J]. Trends Cell Biol, 2015, 25: 427-436. DOI:10.1016/j.tcb.2015.03.004 |

| [10] |

Paisan-Ruiz C, Bhatia KP, Li A, et al. Characterization of PLA2G6 as a locus for dystonia-parkinsonism[J]. Ann Neurol, 2009, 65: 19-23. DOI:10.1002/ana.21656 |

| [11] |

Magrinelli F, Mehta S, Di Lazzaro G, et al. Dissecting the phenotype and genotype of PLA2G6-related parkinsonism[J]. Mov Disord, 2022, 37: 148-161. DOI:10.1002/mds.28807 |

| [12] |

Cheon Y, Kim HW, Igarashi M, et al. Disturbed brain phospholipid and docosahexaenoic acid metabolism in calcium-independent phospholipase A2-VIA (iPLA2β)-knockout mice[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2012, 1821: 1278-1286. DOI:10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.02.003 |

| [13] |

Mori A, Hatano T, Inoshita T, et al. Parkinson's disease-associated iPLA2-VIA/PLA2G6 regulates neuronal functions and alpha-synuclein stability through membrane remodeling[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2019, 116: 20689-20699. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1902958116 |

| [14] |

Chao H, Liu Y, Fu X, et al. Lowered iPLA2γ activity causes increased mitochondrial lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction in a rotenone-induced model of Parkinson's disease[J]. Exp Neurol, 2018, 300: 74-86. DOI:10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.10.031 |

| [15] |

Yun HM, Choi DY, Oh KW, et al. PRDX6 exacerbates dopaminergic neurodegeneration in a MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease[J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2015, 52: 422-431. DOI:10.1007/s12035-014-8885-4 |

| [16] |

Song C, Zhang J, Qi S, et al. Cardiolipin remodeling by ALCAT1 links mitochondrial dysfunction to Parkinson's diseases[J]. Aging Cell, 2019, 18: e12941. DOI:10.1111/acel.12941 |

| [17] |

Sun WY, Tyurin VA, Mikulska-Ruminska K, et al. Phospholipase iPLA2β averts ferroptosis by eliminating a redox lipid death signal[J]. Nat Chem Biol, 2021, 17: 465-476. DOI:10.1038/s41589-020-00734-x |

| [18] |

Ramanadham S, Ali T, Ashley JW, et al. Calcium-independent phospholipases A2 and their roles in biological processes and diseases[J]. J Lipid Res, 2015, 56: 1643-1668. DOI:10.1194/jlr.R058701 |

| [19] |

Sato H, Taketomi Y, Isogai Y, et al. Group Ⅲ secreted phospholipase A2 regulates epididymal sperm maturation and fertility in mice[J]. J Clin Invest, 2010, 120: 1400-1414. DOI:10.1172/JCI40493 |

| [20] |

Murakami M. Lipoquality control by phospholipase A2 enzymes[J]. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci, 2017, 93: 677-702. DOI:10.2183/pjab.93.043 |

| [21] |

Chilton FH, Murphy RC. Remodeling of arachidonate-containing phosphoglycerides within the human neutrophil[J]. J Biol Chem, 1986, 261: 7771-7777. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)57467-1 |

| [22] |

Song Y, Wilkins P, Hu W, et al. Inhibition of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 suppresses proliferation and tumorigenicity of ovarian carcinoma cells[J]. Biochem J, 2007, 406: 427-436. DOI:10.1042/BJ20070631 |

| [23] |

Hara S, Yoda E, Sasaki Y, et al. Calcium-independent phospholipase A2γ (iPLA2γ) and its roles in cellular functions and diseases[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids, 2019, 1864: 861-868. |

| [24] |

Yamashita A, Hayashi Y, Nemoto-Sasaki Y, et al. Acyltransferases and transacylases that determine the fatty acid composition of glycerolipids and the metabolism of bioactive lipid mediators in mammalian cells and model organisms[J]. Prog Lipid Res, 2014, 53: 18-81. DOI:10.1016/j.plipres.2013.10.001 |

| [25] |

Lands WE, Hart P. Metabolism of glycerolipids. VI. Specificities of acyl coenzyme A: phospholipid acyltransferases[J]. J Biol Chem, 1965, 240: 1905-1911. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)97403-X |

| [26] |

Sugiura T, Masuzawa Y, Waku K. Coenzyme A-dependent transacylation system in rabbit liver microsomes[J]. J Biol Chem, 1988, 263: 17490-17498. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)77862-4 |

| [27] |

Sugiura T, Masuzawa Y, Nakagawa Y, et al. Transacylation of lyso platelet-activating factor and other lysophospholipids by macrophage microsomes. Distinct donor and acceptor selectivities[J]. J Biol Chem, 1987, 262: 1199-1205. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)75771-8 |

| [28] |

Kramer RM, Pritzker CR, Deykin D. Coenzyme A-mediated arachidonic acid transacylation in human platelets[J]. J Biol Chem, 1984, 259: 2403-2406. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)43366-7 |

| [29] |

Ojima A, Nakagawa Y, Sugiura T, et al. Selective transacylation of 1-O-alkylglycerophosphoethanolamine by docosahexaenoate and arachidonate in rat brain microsomes[J]. J Neurochem, 1987, 48: 1403-1410. DOI:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb05678.x |

| [30] |

Cao J, Liu Y, Lockwood J, et al. A novel cardiolipin-remodeling pathway revealed by a gene encoding an endoplasmic reticulum-associated acyl-CoA: lysocardiolipin acyltransferase (ALCAT1) in mouse[J]. J Biol Chem, 2004, 279: 31727-31734. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M402930200 |

| [31] |

Reddy PV, Schmid HH. Selectivity of acyl transfer between phospholipids: arachidonoyl transacylase in dog heart membranes[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1985, 129: 381-388. DOI:10.1016/0006-291X(85)90162-7 |

| [32] |

Vance JE. Phospholipid synthesis and transport in mammalian cells[J]. Traffic, 2015, 16: 1-18. DOI:10.1111/tra.12230 |

| [33] |

Benjamins JA, Murphy EJ, Seyfried TN. Chapter 5 - Lipids [M]//Brady ST, Siegel GJ. Albers RW, et al. Basic Neurochemistry (Eighth Edition). New York: Academic Press, 2012: 81-100.

|

| [34] |

Kent C. Eukaryotic phospholipid biosynthesis[J]. Annu Rev Biochem, 1995, 64: 315-343. DOI:10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.001531 |

| [35] |

Ross BM, Mamalias N, Moszczynska A, et al. Elevated activity of phospholipid biosynthetic enzymes in substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson's disease[J]. Neuroscience, 2001, 102: 899-904. DOI:10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00501-7 |

| [36] |

Wu Z, Wu S, Liang T, et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 is a risk factor for patients with Parkinson's disease[J]. Front Neurosci, 2021, 15: 633022. DOI:10.3389/fnins.2021.633022 |

| [37] |

Chalimoniuk M, Stolecka A, Zieminska E, et al. Involvement of multiple protein kinases in cPLA2 phosphorylation, arachidonic acid release, and cell death in in vivo and in vitro models of 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced parkinsonism-the possible key role of PKG[J]. J Neurochem, 2009, 110: 307-317. DOI:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06147.x |

| [38] |

López Grueso MJ, Tarradas Valero RM, Carmona-Hidalgo B, et al. Peroxiredoxin 6 down-regulation induces metabolic remodeling and cell cycle arrest in HepG2 cells[J]. Antioxidants (Basel), 2019, 8: 505. DOI:10.3390/antiox8110505 |

| [39] |

Kinghorn KJ, Castillo-Quan JI. Mitochondrial dysfunction and defects in lipid homeostasis as therapeutic targets in neurodegene-ration with brain iron accumulation[J]. Rare Dis, 2016, 4: e1128616. DOI:10.1080/21675511.2015.1128616 |

| [40] |

Illingworth MA, Meyer E, Chong WK, et al. PLA2G6-associated neurodegeneration (PLAN): further expansion of the clinical, radiological and mutation spectrum associated with infantile and atypical childhood-onset disease[J]. Mol Genet Metab, 2014, 112: 183-189. DOI:10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.03.008 |

| [41] |

Lin G, Lee PT, Chen K, et al. Phospholipase PLA2G6, a parkinsonism-associated gene, affects Vps26 and Vps35, retromer function, and ceramide levels, similar to alpha-synuclein gain[J]. Cell Metab, 2018, 28: 605-618.e6. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.019 |

| [42] |

Iliadi KG, Gluscencova OB, Iliadi N, et al. Mutations in the Drosophila homolog of human PLA2G6 give rise to age-dependent loss of psychomotor activity and neurodegeneration[J]. Sci Rep, 2018, 8: 2939. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-21343-8 |

| [43] |

Kinghorn KJ, Castillo-Quan JI, Bartolome F, et al. Loss of PLA2G6 leads to elevated mitochondrial lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction[J]. Brain, 2015, 138: 1801-1816. DOI:10.1093/brain/awv132 |

| [44] |

Sanchez E, Azcona LJ, Paisan-Ruiz C. PLA2G6 deficiency in zebrafish leads to dopaminergic cell death, axonal degeneration, increased beta-synuclein expression, and defects in brain functions and pathways[J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2018, 55: 6734-6754. DOI:10.1007/s12035-017-0846-2 |

| [45] |

Yeh TH, Liu HF, Chiu CC, et al. PLA2G6 mutations cause motor dysfunction phenotypes of young-onset dystonia-parkinsonism type 14 and can be relieved by DHA treatment in animal models[J]. Exp Neurol, 2021, 346: 113863. DOI:10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113863 |

| [46] |

Lin XM, Sun WY, Duan WJ, et al. Phospholipid peroxidation: a key factor in "susceptibility" to neurodegenerative diseases[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2021, 56: 2154-2163. |

| [47] |

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death[J]. Cell, 2012, 149: 1060-1072. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042 |

| [48] |

Seleznev K, Zhao C, Zhang XH, et al. Calcium-independent phospholipase A2 localizes in and protects mitochondria during apoptotic induction by staurosporine[J]. J Biol Chem, 2006, 281: 22275-22288. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M604330200 |

| [49] |

Chiu CC, Lu CS, Weng YH, et al. PARK14 (D331Y) PLA2G6 causes early-onset degeneration of substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons by inducing mitochondrial dysfunction, ER stress, mitophagy impairment and transcriptional dysregulation in a knockin mouse model[J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2019, 56: 3835-3853. DOI:10.1007/s12035-018-1118-5 |

| [50] |

Sumi-Akamaru H, Beck G, Kato S, et al. Neuroaxonal dystrophy in PLA2G6 knockout mice[J]. Neuropathology, 2015, 35: 289-302. DOI:10.1111/neup.12202 |

| [51] |

Paisan-Ruiz C, Li A, Schneider SA, et al. Widespread lewy body and tau accumulation in childhood and adult onset dystonia-parkinsonism cases with PLA2G6 mutations[J]. Neurobiol Aging, 2012, 33: 814-823. DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.009 |

| [52] |

Sumi-Akamaru H, Beck G, Shinzawa K, et al. High expression of alpha-synuclein in damaged mitochondria with PLA2G6 dysfunction[J]. Acta Neuropathol Commun, 2016, 4: 27. DOI:10.1186/s40478-016-0298-3 |

| [53] |

Fisher AB. Peroxiredoxin 6: a bifunctional enzyme with glutathione peroxidase and phospholipase A2 activities[J]. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2011, 15: 831-844. DOI:10.1089/ars.2010.3412 |

| [54] |

Chen JW, Dodia C, Feinstein SI, et al. 1-Cys peroxiredoxin, a bifunctional enzyme with glutathione peroxidase and phospholipase A2 activities[J]. J Biol Chem, 2000, 275: 28421-28427. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M005073200 |

| [55] |

Fisher AB. Peroxiredoxin 6 in the repair of peroxidized cell membranes and cell signaling[J]. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2017, 617: 68-83. DOI:10.1016/j.abb.2016.12.003 |

| [56] |

Fisher AB, Dodia C, Sorokina EM, et al. A novel lysophosphatidylcholine acyl transferase activity is expressed by peroxiredoxin 6[J]. J Lipid Res, 2016, 57: 587-596. DOI:10.1194/jlr.M064758 |

| [57] |

Goemaere J, Knoops B. Peroxiredoxin distribution in the mouse brain with emphasis on neuronal populations affected in neurodegenerative disorders[J]. J Comp Neurol, 2012, 520: 258-280. DOI:10.1002/cne.22689 |

| [58] |

Pankiewicz JE, Diaz JR, Marta-Ariza M, et al. Peroxiredoxin 6 mediates protective function of astrocytes in Aβ proteostasis[J]. Mol Neurodegener, 2020, 15: 50. DOI:10.1186/s13024-020-00401-8 |

| [59] |

Yun HM, Jin P, Han JY, et al. Acceleration of the development of Alzheimer's disease in amyloid β-infused peroxiredoxin 6 overexpression transgenic mice[J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2013, 48: 941-951. DOI:10.1007/s12035-013-8479-6 |

| [60] |

Shanshan Y, Beibei J, Li T, et al. Phospholipase A2 of peroxiredoxin 6 plays a critical role in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion inflammatory injury[J]. Front Cell Neurosci, 2017, 11: 99. |

| [61] |

Power JH, Shannon JM, Blumbergs PC, et al. Nonselenium glutathione peroxidase in human brain: elevated levels in Parkinson's disease and dementia with lewy bodies[J]. Am J Pathol, 2002, 161: 885-894. DOI:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64249-6 |

| [62] |

Ma S, Zhang X, Zheng L, et al. Peroxiredoxin 6 is a crucial factor in the initial step of mitochondrial clearance and is upstream of the PINK1-Parkin pathway[J]. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2016, 24: 486-501. DOI:10.1089/ars.2015.6336 |

| [63] |

Palacino JJ, Sagi D, Goldberg MS, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in parkin-deficient mice[J]. J Biol Chem, 2004, 279: 18614-18622. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M401135200 |

| [64] |

Davison EJ, Pennington K, Hung CC, et al. Proteomic analysis of increased Parkin expression and its interactants provides evidence for a role in modulation of mitochondrial function[J]. Proteomics, 2009, 9: 4284-4297. DOI:10.1002/pmic.200900126 |

| [65] |

Alza NP, Conde MA, Scodelaro-Bilbao PG, et al. Neutral lipids as early biomarkers of cellular fate: the case of alpha-synuclein overexpression[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2021, 12: 52. DOI:10.1038/s41419-020-03254-7 |

| [66] |

Li XX, Tsoi B, Li YF, et al. Cardiolipin and its different properties in mitophagy and apoptosis[J]. J Histochem Cytochem, 2015, 63: 301-311. DOI:10.1369/0022155415574818 |

| [67] |

Shamoto-Nagai M, Hisaka S, Naoi M, et al. Modification of alpha-synuclein by lipid peroxidation products derived from polyunsaturated fatty acids promotes toxic oligomerization: its relevance to Parkinson disease[J]. J Clin Biochem Nutr, 2018, 62: 207-212. DOI:10.3164/jcbn.18-25 |

2022, Vol. 57

2022, Vol. 57