作者贡献:孙洋和朱雨雨制订综述框架, 朱雨雨和宋承霖撰写综述, 孙洋和朱雨雨修改综述, 孙洋全程指导。

利益冲突:作者声明无利益冲突。

银屑病是一种由遗传、免疫及感染等多种因素诱发的慢性自身免疫性皮肤疾病[1], 俗称牛皮癣, 病程较长, 易复发。该病在中国发病率约为0.4%, 在欧美国家发病率更高, 达2%~3%[2], 并呈一定的上升趋势。银屑病患者发病时存在多种细胞因子失衡和细胞内信号转导异常, 并伴有树突状细胞、巨噬细胞、中性粒细胞、T细胞功能失常及角质形成细胞过度增生等, 最终导致表皮组织角化过度、颗粒层消失和表皮微脓肿等表征, 严重情况下甚至引发关节炎、淋巴结发炎、免疫功能紊乱及心血管系统等并发症[1, 3]。

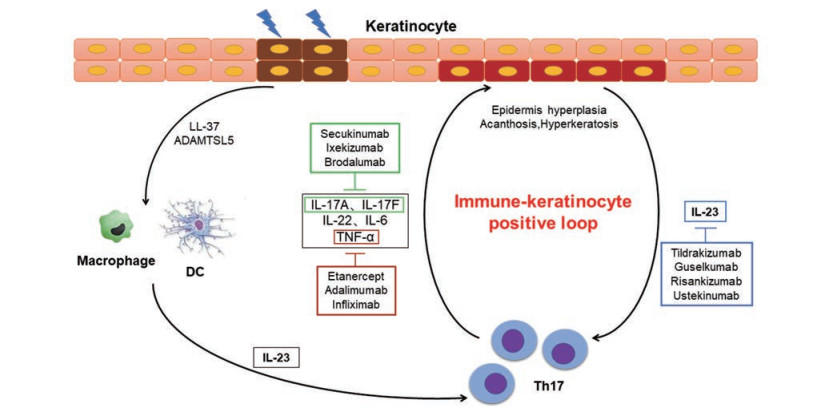

1 发病机制 1.1 银屑病发病机制概述银屑病的病因至今尚不明确, 对银屑病发病机制的探索经历了3个时期, 即角质形成细胞—T细胞—天然免疫[4]。在1970年前后, 人们普遍认为银屑病是一种角质形成细胞生长失调的疾病, 从而限制了治疗银屑病有效策略的发展。直到上个世纪80年代初期, 银屑病的致病机制开始与T淋巴细胞进行关联。临床研究表明, 一系列早期生物免疫拮抗剂能够完全逆转银屑病, 包括抑制异常角质形成细胞的生长。1986年, Valdimarsson等[5]提出银屑病与T淋巴细胞的局部浸润、活化及其诱导的角质形成细胞异常增生密切相关。此后, 随着遗传学、免疫学及分子生物学的日新月异, 大量的研究证实银屑病是一种在多基因遗传背景下T淋巴细胞的表型和功能发生巨大改变、分泌大量炎症细胞因子, 进而诱导表皮角质形成细胞过度增殖, 最终两种细胞交互作用产生一系列慢性炎症反应的自身免疫性皮肤疾病。2007年, Fitch等[6]及Kastelein等[7]在研究自身免疫性疾病时最早发现并提出银屑病发病的“白细胞介素-23/T辅助细胞17 (IL-23/Th17)通路”理论, 近年来人们对IL-23/Th17通路有了更深入的认识和了解。一般认为, 银屑病真皮中的树突状细胞和巨噬细胞产生IL-23, 诱导Th17细胞和γδ T细胞活化[8, 9], 并释放IL-17A、IL-17F、IL-22、IL-6和肿瘤坏死因子-α (TNF-α)等炎性细胞因子。IL-17A、IL-17F及IL-22作用于角质形成细胞, 导致表皮增生、棘层肥厚和角化过度等银屑病典型的病理改变。在皮肤炎症微环境下, 角质形成细胞又可产生更多的IL-23和其他炎性因子、趋化因子, 这样就形成IL-23/Th17正反馈循环[1, 8, 10, 11], 放大并加剧了银屑病慢性炎性病变过程(图 1)。

|

Figure 1 Interleukin-23/T helper17 (IL-23/Th17) cell axis in the pathogenesis of psoriasis |

髓样树突状细胞(myeloid dendritic cells, mDCs)通过激活T细胞, 产生细胞因子和趋化因子, 在银屑病炎症中发挥关键作用[12, 13]。通过检测皮肤中CD11c阳性的DCs, 发现其在银屑病病变中呈上升趋势, 而在成功的治疗患者中呈下降趋势[14]。银屑病患者DCs可强劲刺激T细胞的同种异体混合淋巴细胞反应和诱导同种异体T细胞产生γ-干扰素(IFN-γ)和IL-17[14, 15]。炎性DCs以及产生肿瘤坏死因子和一氧化氮合酶的DCs, 也产生IL-12 p40、IL-23 p19和IL-20[16, 17]。此外, 银屑病病变包含明显增加的完全成熟的DCs, 其特征是表达CD83和DC-LAMP (树突状细胞溶酶体相关膜蛋白)。浆细胞样树突状细胞(plasmacytoid dendritic cells, pDCs)是一种罕见的细胞群, 以浆细胞样形态为特征[18], 参与了银屑病炎症的前馈放大。浆细胞样DCs对病毒和其他微生物感染能迅速而有力地产生Ⅰ型IFN反应, 但通常对自身DNA没有反应。然而有研究表明, 银屑病自身抗原LL-37可以将自身非刺激性蛋白转化, 进而有效触发浆细胞样DCs产生IFN-α, 加剧银屑病进展[19]。Th17细胞产生的细胞因子IL-26可以结合自身DNA促进浆细胞样DCs分泌IFN-α[20], 进而促进周边髓样DCs的成熟[21]。因此, 浆细胞样DCs可能是启动银屑病病变的关键, 这些细胞的早期活化可能与IL-26相关的Th17通路有关[18, 20]。

1.3 巨噬细胞在银屑病发病机制中的作用巨噬细胞是先天免疫的关键细胞之一, 具有吞噬衰老细胞和组织碎片、抗原递呈和杀灭病原微生物的作用[22]。在银屑病患者皮损组织中, 表皮内层巨噬细胞的数目在皮损部位显著增加[23]。这些巨噬细胞沿真皮和表皮交界处分布, 提示这些活化的巨噬细胞可能在银屑病的发病过程中扮演着重要作用。IL-35通过降低M1型/M2型巨噬细胞的比例和巨噬细胞的总数来改善银屑病[24]。ihTNFtg (inducible human TNF transgenic)小鼠与RAG1KO小鼠杂交繁殖的小鼠缺乏成熟T细胞和B细胞, 在这种小鼠上复制咪喹莫特诱导的银屑病样模型, 令人惊讶的是, 小鼠银屑病样的表型竟然没有减轻, 发病反而更加严重[25]。研究人员最后发现在发病小鼠皮损组织中巨噬细胞的浸润明显增加, 体内删除巨噬细胞后小鼠发病症状明显减轻, 以上结果表明巨噬细胞是hTNF介导银屑病发病的主要免疫细胞[25]。近期研究还发现, 当细菌入侵时, 炎性巨噬细胞会产生衣康酸, 而衣康酸能抑制巨噬细胞的功能, 降低IL-17信号通路中关键蛋白IκBζ的水平, 从而减轻炎症反应, 改善银屑病[26]。由此可见, 巨噬细胞作为天然免疫细胞在银屑病的发生发展中发挥着重要作用。

1.4 中性粒细胞在银屑病发病机制中的作用中性粒细胞是先天免疫中数量最多的细胞, 中性粒细胞的主要功能包括促进活性氧(ROS)生成、脱粒(释放颗粒)和中性粒细胞胞外诱捕网的形成[27, 28]。中性粒细胞在炎症部位与抗原递呈细胞和淋巴细胞相互作用, 从而激活适应性免疫。银屑病中的中性粒细胞可引起明显的氧化应激积累, 包括复杂的炎症通路, 从而引起细胞的呼吸爆发。中性粒细胞脱粒过程中释放的蛋白酶, 如髓过氧化物酶(MPO)和中性粒细胞弹性酶(NE)等, 参与了银屑病中ROS的生成、炎症介质的蛋白水解激活及自身抗原的形成[29]。

1.5 T细胞在银屑病发病机制中的作用银屑病患者皮损组织可出现CD3+ T细胞数量的增加。CD4+ T细胞分化的T辅助细胞亚群(Th17、Th22及Th1)分别产生IL-17、IL-22和IFN-γ, CD8+ T细胞也可产生相关细胞因子(Tc17、Tc22及Tc1)[14]。先天淋巴细胞是一种缺乏特异性抗原受体, 但能产生一系列效应细胞因子的免疫细胞, 是银屑病皮肤组织中IL-17的另一种可能来源[30, 31]。来自Th17细胞的IL-17和来自Th22细胞的IL-22均调节角质形成细胞, 但各自调节的通路不同。IL-17是角质形成细胞合成抗菌肽(如S100A7)的强诱导剂, 而IL-22是角质形成细胞增生的强诱导剂[32, 33]。然而, 由于选择性阻断IL-17A或IL-17RA可以逆转80%银屑病患者的临床、组织学和分子特征, 因此Th22亚群在银屑病中的致病功能并不是最关键的[34-37]。Th1细胞在银屑病中的作用可能并不重要, 因为使用IFN-γ中和抗体治疗效果并不显著[38]。相比之下, 选择性阻断IL-23对银屑病的治疗效果反而更佳[39, 40]。调节性T细胞(Treg)是一类控制体内自身免疫反应性的T细胞亚群, 维持抗原特异性的自我耐受, 以防止组织损伤[14]。由于银屑病患者皮肤和血液中CD4+CD25high Treg自身免疫抑制性缺乏, 且与CD4+ T细胞增殖加速有关, 因此认为Treg功能下降可能是银屑病病情进展的关键机制[41-43]。银屑病患者银屑病面积和严重程度指数(PASI)的增加与银屑病皮肤Treg抑制共同受体CTLA4表达降低有关[44]。因此, 免疫抑制功能失调的Treg低水平表达, 可能为骨髓树突状细胞中表达银屑病自身抗原(LL-37和ADAMTSL5)创造了持续激活T细胞的机会。Treg和Th17细胞之间的相互转化, 可能是Treg免疫抑制功能障碍的机制, 转化生长因子-β (TGF-β)在Treg和Th17细胞亚群分化中均起到重要作用, 在银屑病患者免疫系统中很容易分化成产生IL-17A的细胞[45-47]。此外, IL-6在受损的银屑病皮肤中显著升高, 靶向抑制IL-6信号, 通过重平衡Treg/T效应细胞活性, 从而改善银屑病[48]。

2 药物调控IL-23是近年来新发现的细胞因子, 是造血细胞因子家族成员, 主要由活化的巨噬细胞和树突状细胞分泌产生[49, 50], 是IL-12 p40和IL-23 p19两个亚基通过二硫键连接形成的异源二聚体, 其位于T细胞上的受体由IL-12Rβ1和IL-23R两个亚基组成[8, 10]。近年来有关IL-23与银屑病皮损的相关性研究较多, 且集中在银屑病皮损处、血清中IL-23表达水平与PASI相关性研究以及IL-23与银屑病动物模型建立的相关研究[51, 52]。研究表明, 与正常皮肤组织和非皮损组织相比, 寻常型银屑病患者皮损组织中IL-23 (p19/p40) mRNA表达明显增高[52]。将IL-23注入大鼠真皮内, 诱导产生TNF-α依赖性级联反应, 导致出现红斑、真皮浸润和表皮增生等一系列变化, 并伴有IL-19和IL-24表达增加[53], 这些与银屑病皮损处微环境部分相似, 提示IL-23参与银屑病的发病过程。一般认为, 初始CD4+ T细胞在TGF-β和IL-6的共同作用下分化成Th17细胞, 同时IL-23R表达上调。而IL-23则作用于分化的Th17细胞, 诱导其产生大量的IL-17A、IL-17F和IL-22等相关细胞因子, 是其存活和扩增所必需的, 在其表型稳定、增强及之后介导的免疫应答中起重要作用[54]。由此, 人们确立了IL-23和Th17细胞与自身免疫病进程之间的正向关系, 称之为“IL-23/Th17细胞轴”。IL-23可通过正反馈上调IL-6、IL-1β、TNF-α的表达, 参与Th17细胞的扩增和维持其存活。而IL-6和IL-23与银屑病的慢性自身免疫性炎症过程相关, 其中IL-6或IL-23可直接诱导Th17细胞产生IL-22, 同时IL-23也可激活信号传导与活化转录因子3 (STAT3)的表达, 然后以IL-22为主并协同IL-23共同介导银屑病发病进程[55, 56]。可见, IL-23/Th17细胞轴在自身免疫性疾病中发挥着至关重要的作用。下面对靶向该细胞轴的一些上市药物做一介绍。

2.1 IL-23 (p19)拮抗剂上市药物古塞库单抗(guselkumab)、替拉曲珠单抗(tildrakizumab)和SKYRIZI (risankizumab)均为IL-23 p19完全人源化的单克隆中和抗体, 已被美国FDA批准用于中度至重度银屑病的治疗。在Ⅲ期临床试验中, 患者第0周和第4周接受古塞库单抗100 mg, 然后每8周1次, 第16周时, 84.1%患者达到IGA (银屑病灶研究者总体评估) 0/1指标, 而接受安慰剂的患者仅为8.5%。此外, 接受古塞库单抗的患者中70.0%实现了PASI 90 (接近完全皮肤清除)评分, 而接受安慰剂的患者为2.4%。在第24周和第48周古塞库单抗的上述疗效优势仍可持续, 而且可转化为患者生活质量改善[57]。在Ⅲ期临床试验中, 第0周和第4周以及每12周给药1次的替拉曲珠单抗, 有74%患者(229人)在3次用药后第28周达到75%皮肤清除率, 84%持续使用替拉曲珠单抗100 mg的患者在第64周能维持PASI 75, 而重新随机分配使用安慰剂的患者只有22%能维持这一效果[58]。在Ⅲ期临床试验中, 患者在第0周和第4周以及每12周接受皮下注射risankizumab 150 mg, 治疗16周后, 接受risankizumab的患者中73%达到了PASI 90, 而接受安慰剂的患者为2%;接受risankizumab的患者中47%达到了PASI 100 (完全皮肤清除), 而接受安慰剂的患者为1%。接受risankizumab的患者中84%达到sPGA (医师整体评估) 0/1, 而安慰剂患者中只有7%达到sPGA 0/1。在第28周达到清除或几乎清除(sPGA 0/1)结果的患者里, 维持组的患者有87%能维持一年sPGA 0/1, 而撤药组患者维持sPGA 0/1的比例为61% (P < 0.001)[59]。以上这些IL-23中和性抗体的临床试验均显示, 中度至重度银屑病患者的临床症状得到了快速和持久的改善, 进一步证实IL-23/Th17细胞轴是银屑病的主要致病机制。

2.2 TNF-α拮抗剂依那西普(etanercept)、阿达木单抗(adalimumab)及英夫利昔单抗(infliximab)是FDA批准用于治疗中度至重度银屑病的药物。依那西普中和TNF-α后, 可以减少DCs和Th17细胞下游效应分子(CCL20、β-defensin 4、IL17、IL22)的产生[60]。阿达木单抗已证实对IL-23和IL-17相关基因具有快速且强的调控作用[61]。TNF-α抑制剂还能削弱T细胞与DCs的互动, 以及T细胞活化反应, 减少炎性细胞因子的生产[60, 62, 63]。英夫利昔单抗是治疗银屑病的唯一静脉注射药物。然而有高达40%患者对TNF阻断剂治疗不足或无反应, 因此亟需开发新的银屑病治疗药物。

2.3 IL-12/IL-23 p40拮抗剂乌斯泰金单抗(ustekinumab)是IL-12/IL-23 p40的抑制剂, 是FDA批准的治疗中度至重度银屑病的药物。乌斯泰金单抗治疗5年以上显示出持久的有效性, 且没有显著的减弱反应[64]。由于p40是IL-12和IL-23的共同亚单位, 因此乌斯泰金单抗对Th1和Th17亚群都有直接影响[65]。IL-12拮抗剂抑制Th1细胞的发育或应答, IL-23拮抗剂抑制Th17细胞的功能。虽然随着乌斯泰金单抗使用时间的增加, 未观察到剂量相关或累积毒性, 但理论上仍存在一种担忧, 即对Th1细胞的长期影响可能最终损害某些类型的保护性免疫[66]。

2.4 IL-17拮抗剂苏金单抗(secukinumab)和艾克司单抗(ixekizumab)是抗IL-17A单克隆抗体, 是FDA批准的治疗中度至重度银屑病的药物。布罗达单抗(brodalumab)是一种IL-17R抑制剂, 已经完成了治疗中度至重度银屑病的Ⅲ期临床试验。在Ⅲ期临床试验中, 苏金单抗和艾克司单抗均有阻断作用, 临床疗效显著, 组织学上表皮增生迅速减少, 基因组分析中银屑病相关转录组表达明显减少[67-69]。综上所述, 抑制IL-17A或IL-17R可以有效治疗银屑病[34]。

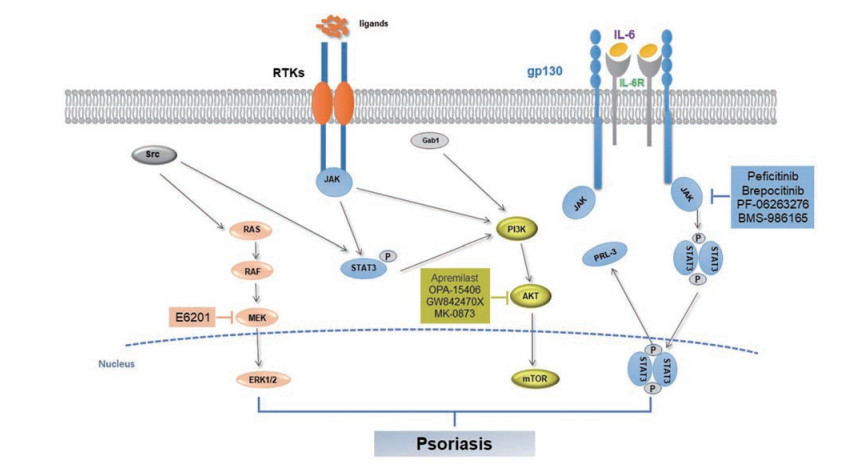

2.5 小分子药物或化合物改善银屑病的最新进展目前, JAK (Janus kinase)作为银屑病干预靶点的研究受到较多的关注[70], JAK-STAT通路上的干预靶点见图 2。托法替尼可有效抑制JAK1和JAK3, 于2012年获美国FDA批准用于治疗类风湿关节炎, 但其申请中重度斑块型银屑病的适应症在2015年被美国FDA否决。鉴于托法替尼在临床银屑病性关节炎患者上取得了较好的疗效, 2017年美国FDA批准其用于银屑病性关节炎的治疗[71]。另外, JAK1特异性抑制剂upadacitinib已获FDA批准用于治疗中度至重度活动性风湿性关节炎, 其在治疗银屑病性关节炎的Ⅲ期临床试验中亦取得优异的疗效[72]。JAK激酶家族成员TYK2选择性抑制剂BMS-986165治疗斑块型银屑病的Ⅱ期临床试验于2018年获得成功[73], 目前正在开展Ⅲ期临床研究[74, 75]。JAK抑制剂PF-06263276外用治疗寻常型银屑病的Ⅰ期临床试验于2017年完成[76]。Pan-JAK抑制剂peficitinib (ASP015K)治疗斑块型银屑病的Ⅱ期临床试验也已完成[77]。此外, 还有一些TYK2抑制剂如PF-06826647和brepocitinib等, 这些药物具有较好的安全性, 目前正在银屑病适应症的临床试验阶段[74]。

|

Figure 2 The Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of tran-ions (JAK-STAT) signaling in the pathogenesis of psoriasis |

磷酸二酯酶(PDE)具有水解细胞内第二信使环磷酸腺苷(cAMP)的作用。PDE有8个家族, 其中PDE-4是炎性细胞中的主要PDE。PDE-4抑制剂可特异性作用于cAMP, 增加细胞内cAMP水平; 同时, 可抑制T细胞分泌TNF-α和IFN-γ, 抑制外周单核细胞和淋巴细胞分泌IL-2, 并产生抗炎因子IL-10[78], 其在斑块型银屑病和银屑病关节炎的治疗中有较好的有效性和安全性[79]。至今全球已上市的PDE-4抑制剂口服药有阿普斯特, 该药用于治疗中、重度斑块型银屑病。目前有多个PDE-4抑制剂处于研发阶段, 如OPA-15406、GW842470X、DRM02和MK-0873[80]。

蛋白激酶C (PKC)抑制剂在信号级联反应和适应性免疫系统中起着重要的作用。PKC调节免疫过程中淋巴细胞、巨噬细胞和树突状细胞的形成、分化和激活。PKC抑制剂sotrastaurin可抑制T细胞的早期活化和IL-2的产生, 拮抗IL-17和IFN-γ。临床研究表明, sotrastaurin可改善银屑病的临床症状, 耐受性良好[81]。

MEK为细胞外信号调节蛋白激酶(ERK)信号传导通路的第2级, 具有磷酸化丝氨酸/苏氨酸和酪氨酸残基的功能, 可参与调控细胞增殖、分化、转化及凋亡等。E6201作为抑制和治疗皮炎及增生疾病(如银屑病)的外用药物, 正处于临床试验阶段[82]。

3 展望银屑病是一种常见的慢性炎症性皮肤病。银屑病患者的免疫系统紊乱与中性粒细胞、树突状细胞、T细胞和角质形成细胞等过度活化有关[83, 84]。本文主要综述了银屑病中IL-23/Th17细胞轴(图 1)和JAK-STAT通路(图 2)上的干预靶点, 以及治疗药物。通过研发针对IL-23/Th17通路中白介素家族因子的多种单克隆抗体, 阻断信号向下游传递, 进而减轻炎症反应, 是目前治疗银屑病的主要策略。抗体类药物同时也存在一些不足, 如价格昂贵、注射带来的不适以及引发感染等, 因此亟需开发治疗银屑病的口服小分子药物。总之, 随着新药开发策略的日益丰富及安全有效小分子抑制剂的不断开发, 相信会有更多靶向IL-23/Th17细胞轴通路的药物进入临床, 发挥治疗作用。

| [1] |

Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis[J]. Lancet, 2015, 386: 983-994. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61909-7 |

| [2] |

Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2014, 70: 512-516. DOI:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013 |

| [3] |

Ciccia F, Triolo G, Rizzo A. Psoriatic arthritis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 376: 2094-2095. DOI:10.1056/NEJMc1704342 |

| [4] |

Sabat R, Sterry W, Philipp S, et al. Three decades of psoriasis research: where has it led us[J]. Clin Dermatol, 2007, 25: 504-509. DOI:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.08.002 |

| [5] |

Valdimarsson H, Bake BS, Jónsdótdr I, et al. Psoriasis: a disease of abnormal keratinocyte proliferation induced by T lymphocytes[J]. Immunol Today, 1986, 7: 256-259. DOI:10.1016/0167-5699(86)90005-8 |

| [6] |

Fitch E, Harper E, Skorcheva I, et al. Pathophysiology of psoriasis: recent advances on IL-23 and Th17 cytokines[J]. Curr Rheumatol Rep, 2007, 9: 461-467. DOI:10.1007/s11926-007-0075-1 |

| [7] |

Kastelein RA, Hunter CA, Cua DJ. Discovery and biology of IL-23 and IL-27: related but functionally distinct regulators of inflammation[J]. Ann Rev Immunol, 2007, 25: 221-242. DOI:10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104758 |

| [8] |

Duvallet E, Semerano L, Assier E, et al. Interleukin-23: a key cytokine in inflammatory diseases[J]. Ann Med, 2011, 43: 503-511. DOI:10.3109/07853890.2011.577093 |

| [9] |

Ganguly D, Haak S, Sisirak V, et al. The role of dendritic cells in autoimmunity[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2013, 13: 566-577. DOI:10.1038/nri3477 |

| [10] |

Konya V, Czarnewski P, Forkel M, et al. Vitamin D downregulates the IL-23 receptor pathway in human mucosal ILC3[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2018, 141: 279-292. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.01.045 |

| [11] |

Shabgah AG, Navashenaq JG, Shabgah OG, et al. Interleukin-22 in human inflammatory diseases and viral infections[J]. Autoimmu Rev, 2017, 16: 1209-1218. DOI:10.1016/j.autrev.2017.10.004 |

| [12] |

Zaba LC, Fuentes-Duculan J, Eungdamrong NJ, et al. Psoriasis is characterized by accumulation of immunostimulatory and Th1/Th17 cell-polarizing myeloid dendritic cells[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2009, 129: 79-88. DOI:10.1038/jid.2008.194 |

| [13] |

Jin K, Luo Z, Zhang B, et al. Biomimetic nanoparticles for inflammation targeting[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2018, 8: 23-33. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2017.12.002 |

| [14] |

Lowes MA, Suárez-Fariñas M, Krueger JG. Immunology of psoriasis[J]. Ann Rev Immunol, 2014, 32: 227-255. DOI:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120225 |

| [15] |

Hyder LA, Gonzalez J, Harden JL, et al. TREM-1 as a potential therapeutic target in psoriasis[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2013, 133: 1742-1751. DOI:10.1038/jid.2013.68 |

| [16] |

Zaba LC, Fuentes-Duculan J, Eungdamrong NJ, et al. Identification of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand and other molecules that distinguish inflammatory from resident dendritic cells in patients with psoriasis[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2010, 125: 1261-1268. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.018 |

| [17] |

Lowes MA, Chamian F, Abello MV, et al. Increase in TNF- and inducible nitric oxide synthase-expressing dendritic cells in psoriasis and reduction with efalizumab (anti-CD11a)[J]. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A, 2005, 102: 19057-19062. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0509736102 |

| [18] |

Nestle FO, Conrad C, Tun-Kyi A, et al. Plasmacytoid predendritic cells initiate psoriasis through interferon-alpha production[J]. J Exp Med, 2005, 202: 135-143. DOI:10.1084/jem.20050500 |

| [19] |

Lande R, Gregorio J, Facchinetti V, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide[J]. Nature, 2007, 449: 564-569. DOI:10.1038/nature06116 |

| [20] |

Donnelly RP, Sheikh F, Dickensheets H, et al. Interleukin-26: an IL-10-related cytokine produced by Th17 cells[J]. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2010, 21: 393-401. DOI:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.09.001 |

| [21] |

Blanco P, Palucka AK, Gill M, et al. Induction of dendritic cell differentiation by IFN-alpha in systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Science, 2001, 294: 1540-1543. DOI:10.1126/science.1064890 |

| [22] |

Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease[J]. Nature, 2013, 496: 445-455. DOI:10.1038/nature12034 |

| [23] |

Brunner PM, Koszik F, Reininger B, et al. Infliximab induces downregulation of the IL-12/IL-23 axis in 6-sulfo-LacNac (slan)+ dendritic cells and macrophages[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2013, 132: 1184-1193. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.036 |

| [24] |

Zhang JF, Lin Y, Li CL, et al. IL-35 decelerates the inflammatory process by regulating inflammatory cytokine secretion and M1/M2 macrophage ratio in psoriasis[J]. J Immunol, 2016, 197: 2131-2144. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1600446 |

| [25] |

Dantas RL, Masemann D, Schied T, et al. Macrophage-mediated psoriasis can be suppressed by regulatory T lymphocytes[J]. J Pathol, 2016, 240: 366-377. DOI:10.1002/path.4786 |

| [26] |

Bambouskova M, Gorvel L, Lampropoulou V, et al. Electrophilic properties of itaconate and derivatives regulate the IκBζ-ATF3 inflammatory axis[J]. Nature, 2018, 556: 501-504. DOI:10.1038/s41586-018-0052-z |

| [27] |

Tecchio C, Cassatella MA. Neutrophil-derived chemokines on the road to immunity[J]. Semin Immunol, 2016, 28: 119-128. DOI:10.1016/j.smim.2016.04.003 |

| [28] |

Nauseef, William M, Borregaard, et al. Neutrophils at work[J]. Nat Immunol, 2014, 15: 602-611. DOI:10.1038/ni.2921 |

| [29] |

Singh TP, Zhang HH, Borek I, et al. Monocyte-derived inflammatory Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells mediate psoriasis-like inflammation[J]. Nat Commun, 2016, 7: 13581. DOI:10.1038/ncomms13581 |

| [30] |

Spits H, Cupedo T. Innate lymphoid cells: emerging insights in development, lineage relationships, and function[J]. Ann Rev Immunol, 2012, 30: 647-675. DOI:10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075053 |

| [31] |

Villanova F, Flutter B, Tosi I, et al. Characterization of innate lymphoid cells in human skin and blood demonstrates increase of NKp44+ ILC3 in psoriasis[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2014, 134: 984-991. DOI:10.1038/jid.2013.477 |

| [32] |

Nograles KE, Zaba LC, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Th17 cytokines interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-22 modulate distinct inflammatory and keratinocyte-response pathways[J]. Br J Dermatol, 2008, 159: 1092-1102. |

| [33] |

Eyerich S, Eyerich K, Pennino D, et al. Th22 cells represent a distinct human T cell subset involved in epidermal immunity and remodeling[J]. J Clin Invest, 2009, 119: 3573-3585. |

| [34] |

Krueger JG, Fretzin S, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. IL-17A is essential for cell activation and inflammatory gene circuits in subjects with psoriasis[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2012, 130: 145-154. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.024 |

| [35] |

Papp KA, Leonardi C, Menter A, et al. Brodalumab, an anti-interleukin-17-receptor antibody for psoriasis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 366: 1181-1189. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1109017 |

| [36] |

Papp KA, Reid C, Foley P, et al. Anti-IL-17 receptor antibody AMG 827 leads to rapid clinical response in subjects with moderate to severe psoriasis: results from a phase I, randomized, placebo-controlled trial[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2012, 132: 2466-2469. DOI:10.1038/jid.2012.163 |

| [37] |

Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, et al. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 367: 1190-1199. |

| [38] |

Harden JL, Johnson-Huang LM, Chamian MF, et al. Humanized anti-IFN-γ (HuZAF) in the treatment of psoriasis[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2015, 135: 553-556. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.046 |

| [39] |

Krueger JG, Ferris LK, Menter A, et al. Anti-IL-23A mAb BI 655066 for treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biomarker results of a single-rising-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2015, 136: 116-124. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.018 |

| [40] |

Sofen H, Smith S, Matheson RT, et al. Guselkumab (an IL-23-specific mAb) demonstrates clinical and molecular response in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2014, 133: 1032-1040. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.025 |

| [41] |

Sugiyama H, Gyulai R, Toichi E, et al. Dysfunctional blood and target tissue. CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells in psoriasis: mechanism underlying unrestrained pathogenic effector T cell proliferation[J]. J Immunol, 2005, 174: 164-173. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.164 |

| [42] |

Chen L, Shen Z, Wang G, et al. Dynamic frequency of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells in psoriasis vulgaris[J]. J Dermatol Sci, 2008, 51: 200-203. DOI:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.04.015 |

| [43] |

Kagen MH, Mccormick TS, Cooper KD. Regulatory T cells in psoriasis[J]. Ernst Schering Res Found Workshop, 2006, 56: 193-209. |

| [44] |

Kim J, Oh CH, Jeon J, et al. Molecular phenotyping small (Asian) versus large (Western) plaque psoriasis shows common activation of IL-17 pathway genes but different regulatory gene sets[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2016, 136: 161-172. DOI:10.1038/JID.2015.378 |

| [45] |

Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells[J]. Nature, 2006, 441: 235-238. DOI:10.1038/nature04753 |

| [46] |

Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, et al. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells[J]. Immunity, 2006, 24: 179-189. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001 |

| [47] |

Bovenschen HJ, van de Kerkhof PC, van Erp PE, et al. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells of psoriasis patients easily differentiate into IL-17A-producing cells and are found in lesional skin[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2011, 131: 1853-1860. DOI:10.1038/jid.2011.139 |

| [48] |

Goodman WA, Levine AD, Massari JV, et al. IL-6 signaling in psoriasis prevents immune suppression by regulatory T cells[J]. J Immunol, 2009, 183: 3170-3176. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.0803721 |

| [49] |

Krause P, Morris V, Greenbaum JA, et al. IL-10-producing intestinal macrophages prevent excessive antibacterial innate immunity by limiting IL-23 synthesis[J]. Nat Commun, 2015, 6: 7055. |

| [50] |

Ebbo M, Crinier A, Vély, et al. Innate lymphoid cells: major players in inflammatory diseases[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2017, 17: 665-678. DOI:10.1038/nri.2017.86 |

| [51] |

Kim J, Krueger JG. Highly effective new treatments for psoriasis target the IL-23/type 17 T cell autoimmune axis[J]. Ann Rev Med, 2017, 68: 255-269. DOI:10.1146/annurev-med-042915-103905 |

| [52] |

Chan JR, Blumenschein W, Murphy E, et al. IL-23 stimulates epidermal hyperplasia via TNF and IL-20R2-dependent mechanisms with implications for psoriasis pathogenesis[J]. J Exp Med, 2006, 203: 2577-2587. DOI:10.1084/jem.20060244 |

| [53] |

El-Behi M, Ciric B, Dai H, et al. The encephalitogenicity of TH17 cells is dependent on IL-1- and IL-23-induced production of the cytokine GM-CSF[J]. Nat Immunol, 2011, 12: 568-575. DOI:10.1038/ni.2031 |

| [54] |

Hawkes JE, Chan TC, Krueger JG. Psoriasis pathogenesis and the development of novel targeted immune therapies[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2017, 140: 645-653. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.004 |

| [55] |

Lowes MA, Suárez-Fariñas M, Krueger JG. Immunology of psoriasis[J]. Ann Rev Immunol, 2014, 32: 227-255. DOI:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120225 |

| [56] |

Papp K, Thaci D, Reich K, et al. Tildrakizumab (MK-3222), an anti-interleukin-23p19 monoclonal antibody, improves psoriasis in a phase Ⅱb randomized placebo-controlled trial[J]. Br J Dermatol, 2015, 173: 930-939. DOI:10.1111/bjd.13932 |

| [57] |

Al-Salama ZT, Scott LJ. Guselkumab: a review in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis[J]. Am J Clin Dermatol, 2018, 19: 907-918. DOI:10.1007/s40257-018-0406-1 |

| [58] |

Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Tildrakizumab versus placebo or etanercept for chronic plaquepsoriasis (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2): results from two randomised controlled, phase 3 trials[J]. Lancet, 2017, 390: 276-288. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31279-5 |

| [59] |

Reich K, Gooderham M, Thaci D, et al. Risankizumab compared with adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (IMMvent): a randomised, double-blind, active-comparator-controlled phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394: 576-586. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30952-3 |

| [60] |

Goldminz AM, Suárez-Fariñas M, Wang AC, et al. CCL20 and IL22 messenger RNA expression after adalimumab vs methotrexate treatment of psoriasis: a randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA Dermatol, 2015, 151: 837-846. DOI:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0452 |

| [61] |

Lowes MA, Russell CB, Martin DA, et al. The IL-23/T17 pathogenic axis in psoriasis is amplified by keratinocyte responses[J]. Trends Immunol, 2013, 34: 174-181. DOI:10.1016/j.it.2012.11.005 |

| [62] |

Deluca LS, Gommerman JL. Fine-tuning of dendritic cell biology by the TNF superfamily[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2012, 12: 614-619. |

| [63] |

Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase Ⅲ trial[J]. Lancet, 2006, 367: 29-35. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67763-X |

| [64] |

Chiricozzi A, Krueger JG. IL-17 targeted therapies for psoriasis[J]. Exp Opin Invest Drugs, 2013, 22: 993-1005. DOI:10.1517/13543784.2013.806483 |

| [65] |

Papp KA, Griffiths CE, Gordon K, et al. Long-term safety of ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: final results from 5 years of follow-up[J]. Br J Dermatol, 2013, 168: 844-854. DOI:10.1111/bjd.12214 |

| [66] |

Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis - results of two phase 3 trials[J]. N Engl J Med, 2014, 371: 326-338. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1314258 |

| [67] |

Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M, et al. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials[J]. Lancet, 2015, 386: 541-551. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60125-8 |

| [68] |

Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373: 1318-1328. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1503824 |

| [69] |

Ly K, Smith MP, Thibodeaux Q, et al. Anti-IL-17 in psoriasis[J]. Exp Rev Clin Immunol, 2019, 15: 1185-1194. DOI:10.1080/1744666X.2020.1679625 |

| [70] |

Tang XN, Zhang HJ, Wang WJ, et al. Research progress of small-molecule drugs targeting JAK in autoimmune diseases[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2018, 53: 1591-1597. |

| [71] |

Aletaha D, Kerschbaumer A, Smolen JS. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 378: 775. DOI:10.1056/NEJMc1715189 |

| [72] |

Olivera P, Lasa J, Bonovas S, et al. Safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases or other immune-mediated diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2020, 158: 1554-1573. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.001 |

| [73] |

Papp K, Gordon K, Thaçi D. Phase 2 trial of selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibition in psoriasis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 379: 1313-1321. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1806382 |

| [74] |

Nogueira M, Puig L, Torres T. JAK inhibitors for treatment of psoriasis: focus on selective TYK2 inhibitors[J]. Drugs, 2020, 80: 341-352. DOI:10.1007/s40265-020-01261-8 |

| [75] |

Wrobleski ST, Moslin R, Lin S. Highly selective inhibition of tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) for the treatment of autoimmune diseases: discovery of the allosteric inhibitor BMS-986165[J]. J Med Chem, 2019, 62: 8973-8995. |

| [76] |

Jones P, Storer RI, Sabnis YA. Design and synthesis of a Pan-Janus kinase inhibitor clinical candidate (PF-06263276) suitable for inhaled and topical delivery for the treatment of inflammatory diseases of the lungs and skin[J]. J Med Chem, 2017, 60: 767-786. |

| [77] |

Papp K, Pariser D, Catlin M, et al. A phase 2a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, sequential dose-escalation study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ASP015K, a novel Janus kinase inhibitor, in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis[J]. Br J Dermatol, 2015, 173: 767-776. DOI:10.1111/bjd.13745 |

| [78] |

Schafer PH, Parton A, Gandhi AK, et al. Apremilast, a cAMP phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, demonstrates anti-inflammatory activity in vitro and in a model of psoriasis[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2010, 159: 842-855. DOI:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00559.x |

| [79] |

Schett G, Wollenhaupt J, Papp K, et al. Oral apremilast in the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study[J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2012, 64: 3156-3167. DOI:10.1002/art.34627 |

| [80] |

Ahluwalia J, Udkoff J, Waldman A, et al. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor therapies for atopic dermatitis: progress and outlook[J]. Drugs, 2017, 77: 1389-1397. DOI:10.1007/s40265-017-0784-3 |

| [81] |

He X, Koenen HJPM, Smeets RL, et al. Targeting PKC in human T cells using sotrastaurin (AEB071) preserves regulatory T cells and prevents IL-17 production[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2014, 134: 975-983. DOI:10.1038/jid.2013.459 |

| [82] |

Muramoto K, Goto M, Inoue Y, et al. E6201, a novel kinase inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase kinase-1: in vivo effects on cutaneous inflammatory responses by topical administration[J]. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2010, 335: 23-31. DOI:10.1124/jpet.110.168583 |

| [83] |

Andrea C, Paolo R, Elisabetta V, et al. Scanning the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2018, 19: 179. DOI:10.3390/ijms19010179 |

| [84] |

Hwang ST, Nijsten T, Elder JT. Recent highlights in psoriasis research[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2017, 137: 550-556. DOI:10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.007 |

2020, Vol. 55

2020, Vol. 55