2. 上海中药标准化研究中心, 上海 201203

2. Shanghai R & D Center for Standardization of Chinese Medicines, Shanghai 201203, China

三七为五加科人参属植物Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F. H. Chen的干燥根及根茎, 主产于中国云南文山[1]。作为传统的珍稀药材, 三七有着悠久的延用历史。在清朝著作《本草纲目拾遗》中记载: “人参补气第一, 三七补血第一, 味同而功亦等, 故称人参三七, 为中药之最珍贵者”[2]。现代研究表明, 三七外用可散瘀止血、消肿止痛, 内服可抗肿瘤、抗抑郁、改善心脑血管功能等[3-6]。相比于新鲜三七, 有文献报道经高温高压蒸制的蒸三七对心血管功能障碍、肿瘤等疾病表现出更加积极的治疗效果[7, 8]。近年来, 对三七的化学组成已有较多的研究, 其主要含氨基酸、黄酮、三萜皂苷等成分, 其中三萜皂苷为三七主要的药效成分, 含量约为12%[9]。

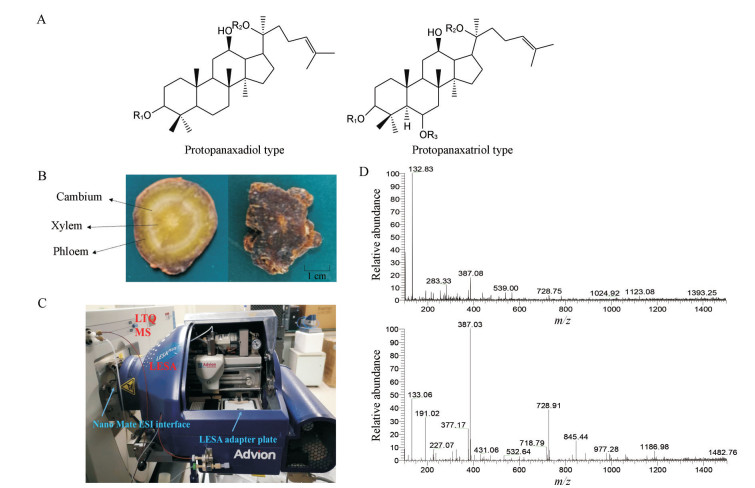

三七中的皂苷成分主要为达玛烷型三萜皂苷。根据其糖基连接点在C-3位和C-6位的区别, 达玛烷型皂苷可以分为原人参二醇型(protopanaxadiol, PPD)和原人参三醇型(protopanaxatriol, PPT) (图 1A)。人参皂苷Rg1、Rb1、Rd、Re为三七中含量较高的PPD型皂苷, 而PPT型的主要有人参皂苷Rg1和三七皂苷R1[10]。当三七药材被蒸制后, 所含极性较大的皂苷成分会在高温高压下经过脱糖、脱水、羟基化等形式转化成极性较小的皂苷[11]。目前针对三七、人参等植物药材的成分分析和质量标准研究大多需要繁琐的预处理过程, 例如对药材的清洗、粉碎、提取等。这些步骤不仅耗时费力, 而且消耗大量有机溶剂, 不符合绿色环保的发展理念[12]。同时, 前处理过程中可能会损失部分活性成分, 对珍贵的三七药材资源造成过多的浪费[13, 14]。

|

图 1 Graphical of experimental. A: PPD type and PPT type of dammarane saponins; B: Fresh P. notoginseng root slice (left) and steamed root slice (right); C: Liquid extraction surface analysis (LESA) device coupled with LTQ MS; D: Mass spectrum of steamed slice in phloem (upper) and mass spectrum of fresh slices in xylem (bottom) |

本研究采用液滴萃取表面分析-质谱方法(liquid extraction surface analysis-mass spectrometry, LESA-MS)首次对三七根药材中的皂苷成分进行快速表征。该敞开式的方法结合了在线表面萃取与芯片多通道纳喷技术, 无需繁琐冗长的样品前处理, 即可对中药材切片实现直接、快速、灵敏及高通量的分析[15]。通过利用LESA-MS方法对新鲜三七根切片和在125 ℃下蒸制2 h的三七根切片样品进行直接分析, 并初步探究新鲜与蒸制三七根木质部、韧皮部、形成层中皂苷成分的差异, 以期为新鲜三七和蒸制三七根切片的药效差异提供初步的理论与物质基础。

材料与方法实验仪器 LESA液滴萃取表面分析系统(美国Advion公司), 包括芯片多通道纳喷离子源, nano-ESI芯片(5 μm), LESA适配板。ThermoFisher Scientific LTQ XL线性离子阱质谱(美国ThermoFisher Scientific公司)。高压灭菌锅(日本ALP公司)。

试剂 实验用水由Milli-Q超纯水系统(美国Millipore公司)制得, 乙腈(色谱纯, 美国Fisher公司), 甲酸(色谱纯, 德国Merck公司)。

三七药材 三七根药材采于中国云南省文山市种植基地, 药材经上海中医药大学吴立宏教授鉴定为五加科植物三七Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F. H. Chen的干燥根及根茎。蒸制三七采用高压灭菌锅在125 ℃下蒸制2 h。

LESA方法 新鲜三七根和蒸制三七根切成表面平整的3~5 mm厚度的圆切片(图 1B), 放置于通用的LESA适配板。采用负离子模式, 气压(gas pressure): 0.5 psi, 应用电压(voltage to apply): 1.70 kV。萃取溶剂为含0.1%甲酸的乙腈-水(80:20), 每次吸头吸取的溶剂体积为2.0 μL, 萃取溶剂在切片表面停留10 s, 再通过带电枪头吸取后经nano-ESI芯片进行自动化的纳升级电喷雾进样。

MS方法 采用负离子全扫描模式, m/z扫描范围: 100~1 500, 毛细管温度为190 ℃。LESA-MS装置如图 1C所示。

数据处理 采用质谱数据处理软件Xcalibur 2.2导出色谱峰的响应值。采用多元统计分析软件SIMCA 14.0进行最小正交偏最小二乘法判别分析(orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis, OPLS-DA)。

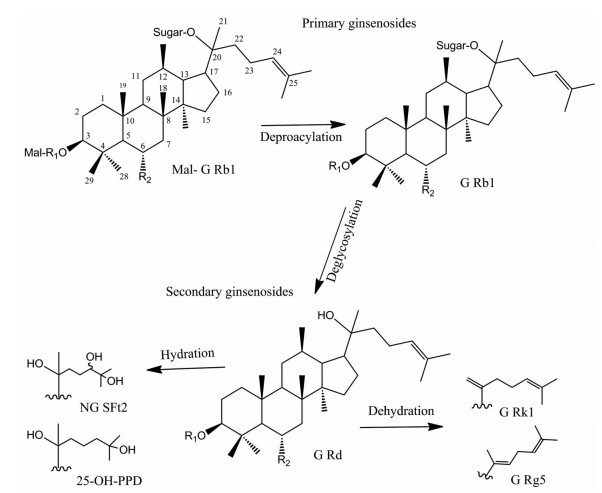

结果 1 新鲜与蒸制三七根切片所含皂苷成分的对比分析采用质谱数据处理软件提取图谱中的化合物峰(图 1D), 根据文献所报道的分子量、质荷比及其来源, 共推测到49个化合物。其中皂苷类化合物有45个, 非皂苷类化合物有4个。以人参皂苷Rg1鉴定为例, 负离子模式下, 在质谱图中检测到m/z 799.5 [M-H]-峰和m/z 845.5 [M+HCOO]-峰, 推断出其分子式为C42H72O14, 猜测为人参皂苷Rg1或人参皂苷Rf。且在三七根中, 人参皂苷Rg1的含量远高于人参皂苷Rf。因此, 根据峰的质谱信号强度, 可进一步推断出该化合物峰为人参皂苷Rg1。在三七根中, 人参皂苷Rg1是含量最高的皂苷, 且响应信号容易确定。因此本实验以新鲜三七根木质部中的人参皂苷Rg1的信号响应为基准值, 其含量定义为1, 鲜三七与蒸三七根切片各部位所含化合物的相对含量见表 1[16-53]。表 1的结果表明, 新鲜三七根切片中的皂苷成分和相对含量与蒸制三七根切片有明显差异。新鲜三七根切片中的不同部位皂苷的种类无明显差异, 其中木质部的含量最高, 韧皮部次之。而在蒸制三七根切片中, 韧皮部的皂苷含量最高, 木质部和形成层含量均较低。在新鲜三七根切片中, 人参皂苷Rg1、Re、Rd、Rb1及其丙二酰基形式, 以及三七皂苷R1相对于其他皂苷成分含量较高。对于蒸制三七根切片, 丙二酰人参皂苷Rg1、Rd和Re含量相对较低, 一些小极性皂苷化合物含量较高, 如三七皂苷R10。相较新鲜三七, 蒸制三七中还可测到新出现的弱极性皂苷成分, 例如人参皂苷Rg5、Rk1、Rs3、Rs7和三七皂苷SFt3、SFt4。根据不同皂苷分子结构及文献检索推测(图 2), 当三七经过高温高压蒸制时, 大极性的皂苷成分会经过C20位脱糖转化为次生皂苷, 再经过水合作用或脱水作用在C17位侧链形成羟基化或双键, 从而转化为弱极性的皂苷化合物。

| 表 1 Relative contents of compounds in different parts of fresh and steamed P. notoginseng root slices. Relative contents: The signal response of ginsenoside Rg1 in the xylem of fresh P. notoginseng was taken as the reference value, and its content was defined as 1 |

|

图 2 Proposed transformation of saponins in the process of steaming of P. notoginseng (take ginsenoside Rb1 for example). Mal-G Rb1: Malonyl-ginsenoside Rb1; G Rb1: Ginsenoside Rb1; G Rd: Ginsenoside Rd; NG SFt2: Notoginsenoside SFt2; G Rk1: Ginsenoside Rk1; G Rg5: Ginsenoside Rg5 |

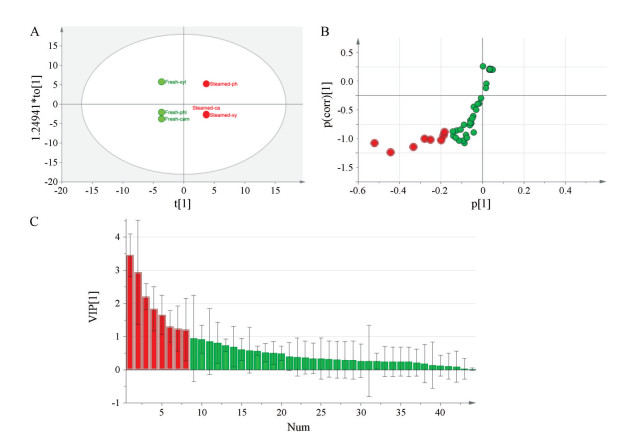

采用有监督OPLS-DA模型对不同切片中皂苷化合物的质谱数据进行分析, 进一步揭示新鲜和蒸制三七根切片的木质部, 韧皮部和形成层中皂苷类成分相对含量的差异。新鲜三七根各部位归为新鲜(fresh)类, 而蒸制则归为蒸制(steamed)类。从OPLS-DA的得分图(图 3A)可知, 新鲜与蒸制三七可显著分离, 其皂苷成分及含量有一定差异。该模型具有良好的解释能力和预测能力(R2X、R2Y和Q2皆为1)。此外, 在新鲜三七根切片中, 韧皮部和形成层皂苷成分和相对含量差异较小, 蒸制三七根切片中, 韧皮部与其他两个部位差异较明显。结合S-Plots和VIP (variable importance on projection)值(图 3B和3C), 进一步筛选出8个新鲜与蒸制三七根中有较大差异的皂苷, 分别为人参皂苷Rg1、Rd/Re、Rg2/F2、Rb1, 丙二酰-人参皂苷Rg1, 三七皂苷R1, 三七皂苷R10和丙二酰-越南参R13。

|

图 3 OPLS-DA results of different parts and saponin compounds in fresh and steamed root slices. A: OPLS-DA score chart; B: OPLS-DA S-Plots loading chart; C: OPLS-DA VIP chart |

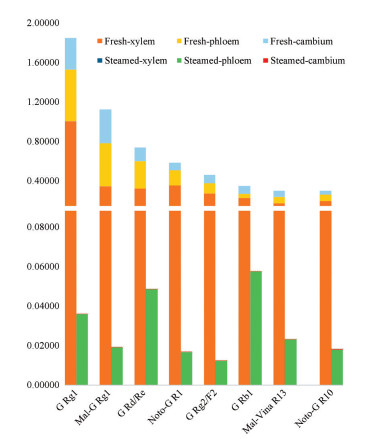

选取上述8个皂苷化合物做堆积图比较新鲜与蒸制三七根主要皂苷的含量差异。图 4结果表明, 新鲜三七根切片中皂苷化合物含量较高, 而蒸制三七根切片中丙二酰类皂苷化合物相对较少, 与直观分析结果相吻合。这些皂苷成分和相对含量的差异均可在一定程度上区别新鲜三七根和蒸制三七根的不同部位。

讨论本研究基于新鲜三七与蒸制三七的药效差异对新鲜与蒸制三七进行化学成分的差异性比较。达玛烷型三萜皂苷是三七中主要的化学成分和药效成分, 遂以该类皂苷作新鲜三七与蒸制三七的差异对比。目前, 对三七中药材的基础成分研究大多采用繁琐的化学和液相方法, 该研究首次建立了一种稳健、快速、节约溶剂的三七根切片LESA-MS测定方法, 只需将三七根切成表面平整的切片形式, 只需2.0 μL提取溶剂, 即可在线操作对切片中化合物进行快速灵敏的分析。在整个分析过程中, 不需要破碎、萃取、分离等繁琐的传统工艺, 能够大大节省物力、人力与时间。该过程操作简便, 可以快速的表征新鲜三七根切片和蒸制三七根切片中皂苷的成分, 从而为中药的快速检测和测定提供了一种新的参考方法。本研究所用的仪器为离子阱质谱, 可提供多级碎片离子信息, 今后如将LESA离子源与高分辨质谱技术联用, 可大大提升对于未知化合物结构快速鉴别能力。

|

图 4 Accumulation diagram of relative contents of major saponins in the fresh and steamed roots slices were detected by LESA-MS. G Rg1: Ginsenoside Rg1; Mal-G Rg1: Malonyl-ginsenoside Rg1; G Rd/Re: Ginsenoside Rd/Re; Noto-G R1: Noto-ginsenoside R1; G Rg2/F2: Ginsenoside Rg2/F2; Mal-Vina R13: Malonyl-vinaginsenoside R13; Noto-G R10: Noto-ginsenoside R10 |

本研究通过快速表征皂苷成分, 共鉴定出49个化合物, 其中45个为皂苷类化合物。对比新鲜与蒸制三七根切片中皂苷成分可知, 人参皂苷Rg1为含量最高的皂苷, 在新鲜与蒸制三七的木质部、韧皮部和形成层部位分布广泛。新鲜三七中的丙二酰类皂苷及大极性皂苷类化合物成分较多, 而在蒸制三七中, 弱极性皂苷化合物则有较多显现, 表明新鲜三七与蒸制三七的皂苷成分和含量均具有较大的差异。根据结构式推论, 新鲜三七中强极性成分可能经过高温高压蒸制脱糖脱水而转化成小极性皂苷成分, 与其他文献研究结果一致[54]。同时, 本研究也采用多元统计方法OPLS-DA对新鲜与蒸制三七进行差异性对比, 所得模型为直观分析的结果提供良好的解释能力与贡献能力。因此, 通过直观解析与数理统计学一体化分析可以直接快速的找出具有较大差异性的皂苷化合物, 为新鲜与蒸制三七皂苷成分的差异性提供解释。

本研究采用快速且无需色谱分离的LESA-MS方法, 能够对三七切片中含量低, 难分离的皂苷化合物进行高通量的快速表征, 从而为三七中皂苷成分的鉴定提供更简便、快速的途径。目前, 相较于新鲜三七, 蒸制三七在抗肿瘤、抗心血管系统疾病、抗氧化等方面表现出更加显著的疗效。因此, 对新鲜三七和蒸制三七根的皂苷成分差异进行无损性的快速辨析将为探究三七中药材生熟药效的差异提供物质基础。

致谢: 华质泰科生物技术(北京)有限公司在LESA仪器使用方面给予大力支持!

| [1] |

Yang Z, Zhu J, Zhang H, et al. Investigating chemical features of Panax notoginseng based on integrating HPLC fingerprinting and determination of multiconstituents by single reference standard[J]. J Ginseng Res, 2018, 42: 334-342. DOI:10.1016/j.jgr.2017.04.005 |

| [2] |

Wang C, McEntee E, Wicks S, et al. Phytochemical and analytical studies of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F.H. Chen[J]. J Nat Med, 2006, 60: 97-106. DOI:10.1007/s11418-005-0027-x |

| [3] |

Sun S, Wang C, Tong R, et al. Effects of steaming the root of Panax notoginseng on chemical composition and anticancer activities[J]. Food Chem, 2010, 118: 307-314. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.04.122 |

| [4] |

Ng TB. Pharmacological activity of sanchi ginseng (Panax notoginseng)[J]. J Pharm Pharmacol, 2006, 58: 1007-1019. DOI:10.1211/jpp.58.8.0001 |

| [5] |

Liu J, Wang Y, Qiu L, et al. Saponins of Panax notoginseng:chemistry, cellular targets and therapeutic opportunities in cardiovascular diseases[J]. Expert Opin Inv Drug, 2014, 23: 523-539. DOI:10.1517/13543784.2014.892582 |

| [6] |

Yang PF, Song XY, Chen MH. Advances in pharmacological studies of Panax notoginseng saponins on brain ischemia-reperfusion injury[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2016, 51: 1039-1046. |

| [7] |

Wang T, Guo R, Zhou G, et al. Traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F.H. Chen:a review[J]. J Ethnopharmacol, 2016, 188: 234-258. DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2016.05.005 |

| [8] |

Ma MM, Wan XQ. Effect of different steaming time on total saponins content of Panax notoginseng[J]. Zhejiang J Tradit Chin Med (浙江中医杂志), 2019, 54: 220-221. |

| [9] |

Guo ZJ, Huang RQ. Content determination of total saponins in Panax notoginseng[J]. China Pharm (中国药业), 2007, 16: 13-14. |

| [10] |

Wang J, Yau L, Gao W, et al. Quantitative comparison and metabolite profiling of saponins in different parts of the root of Panax notoginseng[J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2014, 62: 9024-9034. DOI:10.1021/jf502214x |

| [11] |

Wang D, Liao P, Zhu H, et al. The processing of Panax notoginseng and the transformation of its saponin components[J]. Food Chem, 2012, 132: 1808-1813. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.12.010 |

| [12] |

Tang QY, Chen G, Lu YC, et al. Determination of 4 saponins in the different parts of Panax notoginseng by HPLC[J]. Chin J trop Agr (热带农业科学), 2018, 38: 91-95. |

| [13] |

Liu LM, Zhang XQ, Wang H, et al. Minor saponins constituents from Panax Notoginseng tap root[J]. J Chin Pharm Univ (中国药科大学学报), 2011, 42: 115-118. |

| [14] |

Zhang H, Liu D, Zhang D, et al. Quality assessment of Panax notoginseng from different regions through the analysis of marker chemicals, biological potency and ecological factors[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11: e164384. |

| [15] |

Griffiths RL, Simmonds AL, Swales JG, et al. LESA MS imaging of heat-preserved and frozen tissue:benefits of multistep static FAIMS[J]. Anal Chem, 2018, 90: 13306-13314. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02739 |

| [16] |

Tong JH, Pang XC, Wang W, et al. Comparison on homoisoflavones extracted from Ophiopogon japonicus in Sichuan and Zhejiang and their anti-oxidative activity[J]. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs (中草药), 2015, 46: 3091-3095. |

| [17] |

Hang J, Wang H, Yang XF, et al. Isolation and identification of flavonoids from buds of Panax notoginseng[J]. Nat Prod Res Dev (天然产物研究与开发), 2012, 24: 1060-1062. |

| [18] |

Shibata S, Tanaka O, Soma K, et al. Studies on saponins and sapogenins of ginseng. The structure of panaxatriol[J]. Tetrahedron Lett, 1965, 42: 207-213. |

| [19] |

Yuan W, Guo J, Wang X, et al. Non-protein amino acid derivatives of 25-methoxylprotopanaxadiol/25-hydroxyprotopanaxadioland their anti-tumour activity evaluation[J]. Steroids, 2018, 129: 1-8. DOI:10.1016/j.steroids.2017.11.003 |

| [20] |

Li HZ, Teng RW, Yang CR. A novel hexanordammarane glycoside from the roots of Panax notoginseng[J]. Chinese Chem Lett, 2001, 12: 59-62. |

| [21] |

Kitagawa I, Yoshikawa M, Yoshihara M, et al. Chemical studies of crude drugs (1). Constituents of Ginseng Radix Rubra[J]. Yakugaku Zasshi, 1983, 103: 612-622. DOI:10.1248/yakushi1947.103.6_612 |

| [22] |

Wei JX, Wang JF. Studies on the flavonoids from the leaves of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F.H. Chen[J]. Bull Chin Mater Med (中药通报), 1987, 12: 33-35. |

| [23] |

Teng RW, Li HZ, Wang DZ, et al. Hydrolytic reaction of plant extracts to generate molecular diversity:new dammarane glycosides from the mild acid hydrolysate of root saponins of Panax notoginseng[J]. Helv Chim Acta, 2004, 87: 1270-1278. DOI:10.1002/hlca.200490116 |

| [24] |

Liao P, Wang D, Zhang Y, et al. Dammarane-type glycosides from steamed notoginseng[J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2008, 56: 1751-1756. DOI:10.1021/jf073000s |

| [25] |

Komakine N, Okasaka M, Takaishi Y, et al. New dammarane-type saponin from roots of Panax notoginseng[J]. J Nat Med, 2006, 60: 135-137. DOI:10.1007/s11418-005-0016-0 |

| [26] |

Liu Q, Lv J, Xu M, et al. Dammarane-type saponins from steamed leaves of Panax Notoginseng[J]. Nat Prod Bioprospect, 2011, 1: 124-128. DOI:10.1007/s13659-011-0036-2 |

| [27] |

Park IH, Han SB, Kim JM, et al. Four new acetylated ginsenosides from processed ginseng (sun ginseng)[J]. Arch Pharm Res, 2002, 25: 837-841. DOI:10.1007/BF02977001 |

| [28] |

Qiu L, Jiao Y, Huang G, et al. New dammarane-type saponins from the roots of Panax notoginseng[J]. Helv Chim Acta, 2014, 97: 102-111. DOI:10.1002/hlca.201300155 |

| [29] |

Hasegawa H. Proof of the mysterious efficacy of ginseng:basic and clinical trials:metabolic activation of ginsenoside:deglycosylation by intestinal bacteria and esterification with fatty acid[J]. J Pharmacol Sci, 2004, 95: 153-157. DOI:10.1254/jphs.FMJ04001X4 |

| [30] |

Chen YG, Zhan EY, Chen HF, et al. Saponins with low sugar from the leaves of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F.H. Chen[J]. Chin Med Mat (中药材), 2002, 176-178. |

| [31] |

Li K, Yao C, Yang X. Four new dammarane-type triterpene saponins from the stems and leaves of Panax ginseng and their cytotoxicity on HL-60 cells[J]. Planta Med, 2012, 78: 189-192. DOI:10.1055/s-0031-1280320 |

| [32] |

Park IH, Kim NY, Han SB, et al. Three new dammarane glycosides from heat processed ginseng[J]. Arch Pharm Res, 2002, 25: 428-432. DOI:10.1007/BF02976595 |

| [33] |

Song JP, Zeng J, Cui XM, et al. Studies on chemical constituents from Rhizomes of Panax Notoginseng (Ⅱ)[J]. J Yunnan Univ, 2007, 29: 287-290. |

| [34] |

Baek NI, Kim JM, Park JH, et al. Ginsenoside Rs(3), a genuine dammarane-glycoside from Korean red ginseng[J]. Arch Pharm Res, 1997, 20: 280-282. DOI:10.1007/BF02976158 |

| [35] |

Li WY, Zhang ZD, Hou YB, et al. Separation and identification of malonyl-ginsenosides in stem and leave of Panax ginseng using HPLC-MS[J]. Spec Wild Econ Anim Plant Res (特产研究), 2013, 35: 50-54. |

| [36] |

Liu Q, Lv J, Xu M, et al. Dammarane-type saponins from steamed leaves of Panax Notoginseng[J]. Nat Prod Bioprospect, 2011, 1: 124-128. DOI:10.1007/s13659-011-0036-2 |

| [37] |

Kim D, Chang Y, Zedk U, et al. Dammarane saponins from Panax ginseng[J]. Phytochemistry, 1995, 40: 1493-1497. DOI:10.1016/0031-9422(95)00218-V |

| [38] |

Pei Y, Du Q, Liao P, et al. Notoginsenoside ST-4 inhibits virus penetration of herpes simplex virus in vitro[J]. J Asian Nat Prod Res, 2011, 13: 498-504. DOI:10.1080/10286020.2011.571645 |

| [39] |

Yoshikawa M, Murakami T, Ueno T, et al. Bioactive saponins and glycosides. Notoginseng:new dammarane-type triterpene oligoglycosides, notoginsenoside-A, -B, -C, -D, from the dried root of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F. H. Chen[J]. Chem Pharm Bull, 1997, 45: 1039-1045. DOI:10.1248/cpb.45.1039 |

| [40] |

Chen J, Li H, Wang D, et al. New dammarane monodesmosides from the acidic deglycosylation of notoginseng-leaf saponins[J]. Helv Chim Acta, 2006, 89: 1442-1448. DOI:10.1002/hlca.200690144 |

| [41] |

Lee SM. Thermal conversion pathways of ginsenosides in red ginseng processing[J]. Nat Prod Sci, 2014, 20: 119-125. |

| [42] |

Yoshikawa M, Morikawa T, Yashiro K, et al. Bioactive saponins and glycosides. XIX. notoginseng (3):immunological adjuvant activity of notoginsenosides and related roots of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F. H. Chen[J]. Chem Pharm Bull, 2001, 49: 1452-1456. DOI:10.1248/cpb.49.1452 |

| [43] |

Kitagawa I, Taniyama T, Teruaki H, et al. Malonyl-ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rc, and Rd, four new malonylated dammarane-type triterpene olgoglycosides from ginseng radix[J]. Chem Pharm Bull, 1983, 9: 3353-3356. |

| [44] |

Duc NM, Kasai R, Ohtani K, et al. Saponins from vietnamese ginseng, Panax vietnamensis Ha et Grushv. Collected in central Vietnam Ⅲ[J]. Chem Pharm Bull, 1994, 42: 634-640. DOI:10.1248/cpb.42.634 |

| [45] |

Yoshikawa M, Morikawa T, Kashima Y, et al. Structures of new dammarane-type triterpene saponins from the flower buds of Panax notoginseng and hepatoprotective effects of principal ginseng saponins[J]. J Nat Prod, 2003, 66: 922-927. DOI:10.1021/np030015l |

| [46] |

Zou K, Zhu S, Meselhy MR, et al. Dammarane-type saponins from Panax japonicus and their neurite outgrowth activity in SK-N-SH cells[J]. J Nat Prod, 2002, 65: 1288-1292. DOI:10.1021/np0201117 |

| [47] |

Kasai R, Besso H, Tanaka O, et al. Saponins of red ginseng[J]. Chem Pharm Bull, 1983, 31: 2120-2125. DOI:10.1248/cpb.31.2120 |

| [48] |

Besso H, Kasai R, Saruwatari Y, et al. Ginsenoside-Ra1 and ginsenoside-Ra2, new dammarane-saponins of Ginseng roots[J]. Chem Pharm Bull, 1982, 30: 2380-2385. DOI:10.1248/cpb.30.2380 |

| [49] |

Matsuura H, Kasai R, Tanaka O, et al. Further studies on dammarane-saponins of sanchi-ginseng[J]. Chem Pharm Bull, 1983, 31: 2281-2287. DOI:10.1248/cpb.31.2281 |

| [50] |

Zhu GY, Li YW, Hau DK, et al. Acylated protopanaxadiol-type ginsenosides from the root of Panax ginseng[J]. Chem Biodivers, 2011, 8: 1853-1863. DOI:10.1002/cbdv.201000196 |

| [51] |

Dai Y, Zhang Y, Zhao X, et al. Identification and evaluation of a panel of ginsenosides from different red ginseng extracts with nootropic effect[J]. Chem Res Chin Univ, 2018, 34: 375-381. DOI:10.1007/s40242-018-7422-9 |

| [52] |

Liu P, Yu H, Zhang L, et al. A rapid method for chemical fingerprint analysis of Panax notoginseng powders by ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry[J]. Chin J Nat Med, 2015, 13: 471-480. |

| [53] |

Sun GZ, Li XG, Liu Z, et al. Isolation and structure characterization of malonyl-notoginsenoside-R4 from the root of Panax ginseng[J]. Chem J Chin Univ (高等学校化学学报), 2007, 28: 1316-1318. |

| [54] |

Peng M, Yi YX, Zhang T, et al. Stereoisomers of saponins in Panax notoginseng (Sanqi):a review[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2018, 9: 188. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2018.00188 |

2020, Vol. 55

2020, Vol. 55