水分子的跨膜转运是生理学上存在已久的一个问题。长期以来, 人们一直认为水分子是以自由扩散的形式进行跨膜转运。有学者曾猜测水分子可能不只有自由扩散一种跨膜转运形式[1]。直到1988年, Agre研究组[2]首次在人的红细胞中发现了水通道蛋白1 (aquaporin 1, AQP1), 确认了水分子跨膜转运的第二种形式, 即水通道蛋白(或称水孔蛋白, aquaporin, AQP)介导的水转运。这种AQP介导的水分子顺浓度梯度的跨膜转运形式, 广泛分布于各界生物之中[3, 4]。目前, 哺乳动物中至少有15种结构不同的AQP被发现, 分别从AQP0命名至AQP14[5, 6]。其中, AQP1、AQP2、AQP4、AQP5和AQP8主要转运水分子, 而AQP3、AQP7、AQP9和AQP10由于其孔道大小(pore size)不同, 还能对甘油和其他溶质进行转运, 因此被称作甘油水通道(aquaglyceroporins, GLPs)[7, 8]。

AQP1是目前人们研究最深入的水通道蛋白。AQP1主要介导水分子的转运, 同时也能跨膜转运部分阳离子[9], 参与细胞迁移过程。人体内, AQP1主要分布于与液体流动相关的组织上皮屏障, 如肾的近曲小管、脉络丛、外周微血管、背根神经节、睫状体上皮及小梁网等部位[10], 参与尿液汇集、房水和脑脊液的产生、唾液分泌、神经信号转导等一系列生理活动[11], 同时还能提高外力变化下细胞的机械顺应性[12], 参与脊神经轴突再生[13]、血管生成[14]、损伤修复及介导胞吐作用[15]等。

近年来, 有很多综述着重阐述了AQP与癌症的关系, 及将AQP抑制剂用于癌症治疗的可行性[16-22]。人们在胆管、膀胱、大脑、乳腺、子宫颈、结肠、肺、鼻咽和前列腺等部位的癌症中都发现了AQP1的过表达现象[23-30]。此外, AQP1的表达与很多癌症预后相关的临床特征联系密切, 如淋巴管浸润和淋巴结转移的组织学分级等[24, 25, 28, 31, 32]。这些都说明AQP1在癌症的发展过程中扮演重要角色, 其在组织器官中的表达情况对肿瘤的临床诊断有帮助, 以AQP1为靶点的药物治疗或许能够抑制肿瘤的扩散, 改善预后。

1 AQP1的结构及功能AQP1是跨膜四聚体, 其单体的分子质量约为28 kDa。每个单体仅由一条单链约270个氨基酸构成, 包含6个倾斜的α-螺旋结构域, 结构域之间由5个环(loop)连接, 其N端和C端均位于细胞内, 形成一个桶状结构[33, 34]。5个loop分为3个胞外环(loop A、C和E)和2个胞内环(loop B和D)。大部分AQP家族成员在胞外的loop E都含有1个半胱氨酸残基Cys189, 氯化汞(HgCl2)、硝酸银(AgNO3)和金(Au)等重金属及其化合物能够与Cys189的巯基结合, 导致AQP构象改变, 从而拮抗其作用[35]。

1.1 AQP1跨膜转运水分子AQP1的loop B和loop E各含有一个高度保守的天冬酰胺-脯氨酸-丙氨酸(NPA)序列, 两个NPA序列折向分子内部并相互配对, 形成水通道[36], 是整个水通道最狭窄的部分, 仅能容纳单个水分子通过, 平均每个水通道中大约含有7个水分子[37]。整个水转运过程是顺浓度梯度, 因此不消耗能量[37, 38]。

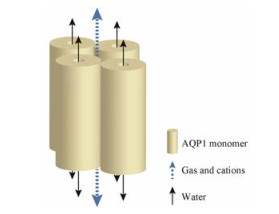

1.2 AQP1跨膜转运部分气体和阳离子4个AQP1单体组装成四聚体, 在四聚体的中间形成一个中央孔道(图 1)。研究发现, AQP1的中央孔道功能由cGMP激活, 并且间接地被cAMP激活[39]。cGMP与AQP1胞内段富含精氨酸的loop D相互作用, 引起相应分子的迁移。因此, 有学者提出, cGMP介导的AQP1胞内段loop D的构象改变或许是控制AQP1中央孔道开放的关键[40]。

|

Figure 1 Homotetramer of aquaporin 1 (AQP1) |

目前认为, 此中央孔道对一些气体分子, 如O2、CO2和NO等[33, 41], 及部分阳离子通透。研究发现, 此中央孔道是cGMP门控的非选择性单价阳离子通道, 对Na+、K+和Cs+等一价阳离子通透, 但是对二价阳离子和H+通透作用不明显。位于AQP1 C端的Tyr253是调控AQP1离子通道活性的关键位点, 处于磷酸化状态的Tyr253能够增强其离子通道活性, 而处于去磷酸化状态则拮抗AQP1对cGMP的应答[42]。

除了AQP1, 在哺乳动物AQP0及AQP6中同样发现了离子通道活性[43]。目前发现很多其他类型的离子通道也具有类似四聚体结构形成的中央孔道[44], 进一步体现其结构与功能的对应关系。

2 AQP1在肿瘤进展中的作用离子通道和转运体(ion channel and transporter, ICT)在肿瘤进展过程中发挥重要作用[45-47]。AQP1作为一种典型的ICT, 能够转运水分子和部分阳离子。AQP1的过表达, 通过改变细胞体积, 调整细胞膜电位[48]及激活一系列下游信号通路[9]等方式, 影响细胞迁移、增殖及血管生成过程, 促进肿瘤的进展。

2.1 细胞迁移癌细胞的迁移和侵袭是癌症进展过程中的关键步骤。细胞迁移可被分为4个主要过程:极化(polarization)、突出(protrusion)、牵拉(traction)和回缩(retraction), 需要对Ca2+浓度、细胞内/外的pH、细胞膜电位、细胞体积及部分ICT的功能进行精确调控[48]。在细胞迁移过程中, 细胞产生极性, ICT在细胞迁移的方向上极性表达, 使得细胞内外渗透压变化, 引起水分子的跨膜流动[49]。关于细胞迁移的具体分子机制可参考更多文献[50-52]。

关于AQP1介导的细胞迁移机制, 目前主要认为, 在细胞迁移方向上, 微丝大量解聚以及一些活性溶质内流引起细胞内渗透压升高[53], 同时AQP1在细胞迁移部位大量表达, 介导水分子大量流入, 引起细胞内流体静压升高, 局部细胞膜扩展, 随后微丝重新聚合以稳定细胞膜突出部分, 完成细胞迁移。

目前许多证据表明, AQP1的过表达或低表达显著影响细胞的迁移能力。在体外培养的小鼠黑色素瘤B16F10细胞系及小鼠乳腺癌4T1细胞系中, AQP1的表达能够加速这些细胞的迁移, 同时在迁移细胞的迁移方向上发现了AQP1的极性表达[54]。Jiang等[55]研究了AQP1在人结肠癌细胞HT20中的表达, 发现AQP1的过表达或者低表达会引起水通透性的改变, 从而对体外培养的人结肠癌细胞HT20的迁移能力产生很大影响。也有研究发现, AQP1的过表达在体外能促进骨髓间充质干细胞(MSC)的迁移, AQP1表达的降低则抑制MSC的迁移; 将绿色荧光蛋白(GFP)标记的AQP1过表达的MSC全身性地注入股骨骨折的大鼠, 发现骨折部位的荧光强度明显高于对照组[56]。这种AQP1与细胞迁移显著的相关性, 提示AQP1可能在癌症转移和侵袭过程中发挥重要作用。AQP1的表达情况或许能够成为判断癌症转移程度的指标之一。

2.2 血管生成肿瘤的血管生成(angiogenesis)是肿瘤进展过程中的另一个关键因素[57]。血管的形成不仅为肿瘤细胞提供更加充足的营养, 同时也能使肿瘤细胞更加容易进入血液循环, 扩散至全身各个部位。随着研究的深入, 人们意识到ICT与血管生成有关。它们能够充当酶、化学/机械传感器、受体和支架蛋白, 在血管生成的过程中发挥作用[58]。

AQP1与肿瘤血管生成的相关性目前得到了许多证据的支持[59]。Saadoun等[60]在AQP1敲除的小鼠模型中, 皮下植入黑色素瘤细胞B16F10, 发现肿瘤的微血管密度明显降低, 小鼠的存活时间明显延长; 同时还认为AQP1可能通过介导血管内皮细胞的迁移而促进血管生成。Nicchia等[14]采用siRNA对小鼠的AQP1进行敲降, 同时皮下植入B16F10黑色素瘤细胞, 发现AQP1表达的抑制能够降低肿瘤微血管密度。Esteva-Font等[26]在小鼠乳腺肿瘤病毒驱动的多瘤病毒中间T癌基因(mouse mammary tumour virus- driven polyoma virus middle T oncogene, MMTV- PyVT)小鼠中同样发现AQP1的缺陷能够降低肿瘤微血管的密度。

血管内皮细胞生长因子(vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF)是促进血管生成的关键分子[61]。至于AQP1促血管生成的作用与VEGF及其下游信号通路是否有关联, 目前研究尚不明确。Pan等[62]研究发现, 在子宫内膜腺癌的进展过程中, AQP1与肿瘤内微血管的密度呈正相关, AQP1与肿瘤内微血管密度的比值与VEGF的表达也呈正相关, 提示AQP1可能与VEGF共同作用于血管生成。Kaneko等[63]在缺氧条件下的视网膜血管内皮细胞中, 发现AQP1的mRNA及蛋白表达均有明显的升高, 用siRNA敲降AQP1的表达和抑制VEGF的信号通路都能有效地抑制血管生成, 然而在抑制VEGF信号通路后, 发现AQP1的表达没有受到影响, 说明AQP1可能与VEGF信号通路无关, AQP1与VEGF各自独立地参与血管生成。这其中的矛盾有待进一步实验验证。

2.3 肿瘤细胞增殖肿瘤细胞增殖同样是肿瘤进展过程的关键因素。尽管存在些许争议[64], 但目前越来越多的证据表明AQP1能够通过多种机制参与肿瘤细胞增殖过程[65]。Hoque等[66]在体外培养的小鼠胚胎成纤维细胞系NIH-3T3中过表达AQP1, 发现对肿瘤细胞增殖有所促进。在大鼠的嗜铬细胞瘤细胞系PC12中也发现了类似的结果[67]。在两个骨肉瘤细胞系U2OS和MG63中使用shRNA下调AQP1的表达后, 发现肿瘤的增殖被明显抑制[68]。Klebe等[69]在胸膜积液中得到的原发性恶性间皮瘤细胞, 采用AQP1抑制剂AqB050或者siRNA敲降处理后, 发现肿瘤细胞的增殖被抑制。由此可见AQP1对肿瘤增殖有显著的促进作用。

AQP1促进肿瘤增殖的机制主要包括三方面, 即调整细胞体积、调控细胞周期及与其他膜蛋白或转录因子相互作用而调控细胞信号转导通路[65]。

细胞增殖与细胞体积变化关系密切。细胞周期进行过程中, 随着蛋白质的合成和DNA的复制, 细胞体积不断增大。研究发现, AQP1过表达能够增加过氧化氢(hydrogen peroxide)的通透性, 调节细胞增殖相关的蛋白表达, 同时其细胞体积大于正常细胞[70], 提示AQP1可能通过增大细胞体积而促进肿瘤增殖。

AQP1对细胞周期的调控可能与抑制细胞凋亡有关[68]。细胞周期的推进伴随着细胞体积的增大, 而细胞凋亡则导致细胞的体积减小[71]。细胞周期蛋白(cyclin) B、D1和E1是推动细胞周期的关键蛋白, 分别在G1期、G1/S转换期及G2/M期发挥作用。AQP1过表达能够升高细胞内cyclin D1和E1的水平, 而对cyclin B的水平无影响[70], 说明AQP1在G1期和G1/S转换期发挥重要作用, 推动细胞周期的进行。

2.4 下游信号通路AQP1除了能改变细胞体积、调整细胞膜电位以外, 还能通过与其他膜蛋白或转录因子相互作用而激活一系列下游信号转导通路, 促进肿瘤的进展。目前, AQP1的下游信号通路仍未完全阐明, 但已有部分研究证实其中一些关键分子在整个过程中发挥重要作用(图 2)。

|

Figure 2 Related signaling pathway of AQP1. +p and +u refer to phosphorylation and ubiquitination respectively |

Wnt通路是一类在进化上高度保守的信号通路, 在胚胎早期发育、生长代谢及组织再生等过程中发挥重要作用[72]。β-Catenin是Wnt信号通路的关键蛋白, Wnt信号可以抑制β-catenin的降解, 稳定胞质内β-catenin水平, 进而调控基因的表达[73]。当Wnt通路未被激活时, 胞质内β-catenin与APC、Axin和GSK3等形成复合物, 并被复合物中的GSK3磷酸化, 磷酸化的β-catenin被E3泛素连接酶β-Trcp识别而被降解, 因此胞质内β-catenin水平很低。Wnt信号出现时, 配体Wnt引起受体Frizzled和LRP5/6交联形成受体复合物, 引发Dishevelled的募集。Dishevelled将LRP5/6磷酸化, 引发Axin的募集, 导致Axin/APC/GSK3/β-catenin复合物的解离, 避免β-catenin被GSK3磷酸化而降解。胞质内的β-catenin转位到细胞核内与TCF/LEF结合, 激活靶基因的转录, 如c-Myc、cyclin D、c-Jun和FRA1 (后两者为AP-1转录因子复合物的组成部分)等, 从而参与细胞周期及细胞增殖、分化和凋亡的调控[74-77]。

Meng等[56]在高表达AQP1的间充质干细胞MSCs中发现了AQP1与β-catenin的免疫共沉淀现象, 并伴有β-catenin表达的上调。用蛋白酶抑制剂MG132处理AQP1基因被沉默的人黑色素瘤细胞WM115后, 发现β-catenin的水平有所恢复, 提示AQP1可能通过抑制β-catenin的降解而增强Wnt通路[78]。Yun等[79]发现, 在肺动脉肌细胞中, β-catenin表达的升高和AQP1含有蛋白结合位点的C端尾部有关。AQP1的C端与β-catenin的结合能够阻碍β-catenin与Axin/ APC/GSK3复合物的结合, 抑制β-catenin的降解[73]。

β-Catenin在细胞黏附过程中同样发挥一定的作用。在上皮-间质转化(epithelial-mesenchymal transition, EMT)的过程中, β-catenin参与细胞膜上钙黏蛋白-连环蛋白复合物(cadherin-catenin complex)的形成[80]。Lin-7是该复合物的另一个成分, 能够与β-catenin的PDZ结构域结合, 并且在人微血管内皮细胞HMEC-1和人黑色素瘤细胞WM115中均发现了Lin-7和AQP1的免疫共沉淀现象。有学者猜测, AQP1能够稳定cadherin/β-catenin/Lin-7/F-actin复合物, 抑制β-catenin的降解, 促进肿瘤细胞的迁移[78]。

然而, 尽管AQP1能够稳定该复合物, 提高β-catenin的水平, 但细胞膜上结合的β-catenin如何进入细胞核发挥作用, 细胞质内β-catenin和细胞膜上结合的β-catenin之间又有怎样的联系?这些细节的研究有利于进一步完善AQP1促进肿瘤进展的机制。

2.4.2 黏着斑激酶(focal adhesion kinase, FAK)及其下游FAK是细胞质内的酪氨酸激酶, 介导生长因子受体及整合素介导的信号转导。FAK能够增强肿瘤细胞的迁移性, 促进EMT, 促进肿瘤血管生成, 从而促进肿瘤进展[81]。VEGF和促血管生成素-1 (angiopoietin-1)通过FAK而激活PI3K/AKT, 进而促进内皮细胞的迁移及血管生成[82]。

Meng等[56]在AQP1过表达的间充质干细胞MSC中发现了FAK与AQP1和β-catenin共沉淀的现象, 提示FAK可能与AQP1、β-catenin及Lin-7等共同形成复合物。同时FAK的敲除减弱了AQP1对MSC细胞迁移的促进作用。AQP1的过表达对FAK的mRNA水平没有影响, 因此认为其FAK表达的上调是发生在翻译后水平的。

RhoA和Rac-1位于FAK通路的下游, 分别属于Rho GTP酶超家族中的Rho亚家族和Rac亚家族, 分别调控间充质运动(mesenchymal movement)和阿米巴样运动(amoeboid movement), 在细胞骨架的重排及细胞迁移、增殖和转化过程中发挥作用, 其调控异常会增强肿瘤的侵袭性, 促进肿瘤细胞迁移[83]。RhoA和Rac-1可以分别通过Rho鸟嘌呤核苷酸交换因子(Rho guanine nucleotide-exchange factor, RHOGEF)和PI3K通路而受到FAK的调控[81]。

Jiang[55]在过表达AQP1的结肠癌细胞HT20中发现, 肌动蛋白在细胞迁移方向上的极性表达升高, 提示这些小G蛋白活性的增强。在U2OS和MG63细胞中, 使用shRNA敲降AQP1后发现RhoA的表达同样有所降低[68]。

2.4.3 基质金属蛋白酶(matrix metalloproteinases, MMP) 2/9MMP是一个内肽酶(endopeptidase)大家族, 需要Ca2+和Zn2+的参与以发挥其组织重构和水解细胞外基质的作用[84]。MMPs对细胞外基质的水解作用能够破坏肿瘤细胞迁移侵袭的组织学屏障, 在肿瘤侵袭和转移过程中发挥关键作用。

在肺癌细胞系LTEP-A2和LLC中, 使用AQP1的siRNA处理细胞能够下调MMP2和MMP9的表达水平[85]。MMP2和MMP9能够降解Ⅳ型胶原(基膜的主要成分)并且激活TGF-β而促进EMT[86]。在很多肿瘤细胞中都能发现MMPs的表达上调, 同时也有研究表明其具有介导肿瘤细胞体外/体内迁移及血管生成的作用[87-89]。

在小鼠成纤维细胞中, FAK能诱导MMP2和MMP9的分泌[90], 在效应T细胞中, Wnt通路也能诱导MMP2和MMP9的表达[91]。因此, AQP1可能通过FAK和Wnt通路增强MMP2和MMP9的活性, 从而促进肿瘤细胞迁移。

2.5 缺氧促进AQP1表达上调由于细胞的迅速增殖, 缺氧是不同种类癌细胞的一个共同特点, 并且会进一步促进肿瘤增殖, 对治疗手段产生耐受[92]。Hayashi等[93]发现, 缺氧环境下的大鼠胶质母细胞瘤细胞的AQP1表达升高, 并且与糖酵解的程度相符, 于是提出缺氧引起的糖酵解能够促进AQP1的表达。

Abreu-Rodrigues等[94]进一步说明了肿瘤细胞中缺氧对AQP1表达的诱导作用。他们认为缺氧能够增强AQP1启动子的活性, 从而促进AQP1的转录, 同时利用生物信息学方法, 发现在鼠类AQP1基因的启动子区域有缺氧诱导转录因子(hypoxia-inducible transcription factor, HIF)的结合位点。在人视网膜血管内皮细胞(human retinal vascular endothelial cell, HRVEC) AQP1基因的启动子区域也发现了HIF结合位点, 并且在缺氧环境下, 同样发现了HRVEC的AQP1启动子活性的增强[95]。Abreu-Rodriguez等[94]将突变的HIF-1α表达于小鼠的内皮细胞系EOMA而阻碍其降解过程, 证明了HIF-1α直接参与缺氧引起的AQP1启动子的活性上调。

AQP1表达上调的意义在于, 由于缺氧引起无氧酵解增强, 细胞内乳酸堆积, pH降低, 细胞需要将H+运送至细胞外, 而这个过程和细胞质内碳酸酐酶(carbonic anhydrase)催化下的H+与HCO3-的反应有关, 产生的水分子则由AQP1运送至细胞外, 以避免细胞过度水肿。因此, AQP1与肿瘤的关系在某种程度上可以认为是一种正反馈, 即细胞的迅速增殖导致细胞处于缺氧环境, 缺氧引起的糖酵解和HIF的表达升高使得AQP1的表达上调, AQP1的过表达则通过对细胞形态学的改变及激活一系列下游信号转导通路等方式, 进一步加剧细胞迁移、增殖及血管生成等过程, 促进肿瘤进展。

3 AQP1的抑制剂随着AQP1与肿瘤的关系得到越来越多的实验证实, 近年来有关AQP1抑制剂的研究也越来越多[64, 96-98], 但目前仍缺少与AQP1抑制剂有关的文献综述。AQP1抑制剂的发现不仅能够作为实验工具以进一步探索AQP1与肿瘤的关系, 同时也能为临床药物治疗提供参考。

3.1 重金属及其化合物HgCl2是最早被发现的AQP抑制剂, 它能够和大部分AQP家族成员胞外loop E的半胱氨酸残基(Cys189)结合而抑制水的通透。后来人们又发现AgNO3和Au等重金属及其化合物同样能够与Cys189的巯基结合, 导致AQP构象不可逆改变, 从而拮抗其作用[99, 100]。然而, 这些重金属都有很强的毒性, 因此不具有临床意义。

3.2 四乙胺(tetraethylammonium, TEA)TEA是电压门控钾离子通道、钙离子依赖钾离子通道及烟碱型乙酰胆碱受体的拮抗剂。后来人们发现TEA也能影响AQP1的活性, 但不同的是TEA能可逆地与AQP1结合[101]。Yool等[102]在爪蟾卵母细胞(Xenopus oocytes)中表达人的AQP1, 发现TEA能够作用于AQP1胞外loop E的酪氨酸残基, 从而降低AQP1对水的通透性, 位于loop E的Tyr186是可能的结合位点。之后, 他们在来源于肾脏的MDCK细胞系中同样发现了TEA对AQP1水通透性的抑制作用, 并且证明TEA并不影响AQP1的离子电导, 提示TEA仅抑制AQP1的水通道活性, 而对其离子通道活性没有影响。

作为典型的钾离子通道阻断剂, TEA主要应用于有关肾小管有机阳离子转运(organic cation transport)的相关研究。TEA对AQP1可逆抑制作用的发现或许能对水通道功能相关疾病, 如青光眼、肺水肿和常染色体显性多囊肾等疾病的药物研发设计提供参考[101]。

3.3 乙酰唑胺(acetazolamide, AZA)AZA是唯一一个具有显著利尿作用的碳酸酐酶抑制剂[103], 通过与Zn2+直接结合并形成碳酸酐酶- AZA复合物发挥其抑制作用。Gao等[104]利用表面等离子共振(surface plasmon resonance)技术检测到AZA与AQP1结合, 提示AZA可能是AQP1的抑制剂。Xiang等[105]在2002年首次证实AZA可以抑制肿瘤的转移, 而该作用与抑制AQP1蛋白表达有关。在大鼠肾脏近曲小管上皮细胞中发现, AZA抑制AQP1的基因表达, 并且提出其中可能的内源性机制[106]。Ma等[107]通过爪蟾卵母细胞表达AQP1模型的研究证实, AZA和一个雌激素受体拮抗剂anordiol可以抑制AQP1介导的水转运, 但机制不同, 前者抑制跨膜水转运的功能, 后者抑制AQP1在膜上的密度。之后有研究发现, AZA抑制肿瘤血管生成与其抑制AQP1的表达相关[108]。采用蛋白质组学的方法发现, 对动物肿瘤生长和转移抑制作用的机制与其上调组蛋白H2B片段和Ubc-样蛋白CROC1片段有关[109]。Zhang等[110]的研究发现AZA抑制水跨膜转运的机制可能通过促进肌球蛋白重链与AQP1的相互作用, 使AQP1转运到细胞膜, 最终导致AQP1的泛素化降解。AZA在临床上的应用较为广泛, 主要用于治疗部分水代谢紊乱疾病, 如青光眼、高原脑病和肺水肿等[106]。

3.4 布美他尼(bumetanide)衍生物布美他尼是临床上常用的速效利尿剂。Kourghi等[111]发现布美他尼的部分衍生物能选择性抑制AQP1的活性, 被命名为AqB (aquaporin ligand bumetanide derivative), 其中AqB011是最有效的拮抗剂。AqB011和AqB007能够与AQP1细胞内loop D结构域结合, 抑制AQP1的离子通道活性, 而对水通道活性没有影响, 从而抑制表达AQP1的HT29细胞的迁移。

Dorward等[64]在HT29细胞中发现, 一定浓度的AqB013能够明显抑制其细胞迁移。由于使用AqB013处理小鼠胃窦肌细胞后发现, 细胞的静息膜电位及导电性质并未发生变化[112], 因此推测AqB013通过阻断AQP1的水通道活性而发挥其抑制细胞迁移的作用[64]。

有关布美他尼衍生物的应用主要集中在科研工作方面。AqB011的发现为AQP1离子通道功能作用机制的研究提供了新的研究工具; 其他衍生物, 如AqB050等, 在科研工作中能够代替siRNA实现对AQP1表达下调的效果[69]。

3.5 假马齿苋皂苷(bacopaside)Pei等[98]从药用植物假马齿苋Bacopa monnieri中分离得到的假马齿苋皂苷(bacopaside) Ⅰ和Ⅱ具有AQP1拮抗剂的作用。假马齿苋皂苷Ⅰ抑制AQP1的水通道和离子通道活性(IC50 117 μmol·L-1), 对AQP4没有影响; 假马齿苋皂苷Ⅱ选择性抑制AQP1的水通道活性(IC50 18 μmol·L-1)。分子对接结果显示, AQP1细胞内loop B结构域的Ser71及其相邻跨膜结构域的Tyr97可能与其结合有关。细胞水平实验表明, 假马齿苋皂苷Ⅰ和Ⅱ都能抑制HT29细胞迁移, 并且假马齿苋皂苷Ⅰ比Ⅱ有更显著的细胞迁移抑制效果, 提示同时抑制AQP1水通道和离子通道的活性可能会对细胞迁移有更有效的抑制作用。

然而, 经过验证假马齿苋皂苷Ⅰ和Ⅱ不满足Lipinski五倍率法则[98], 尽管天然产物通常被视为Lipinski五倍率法则的例外, 但假马齿苋皂苷Ⅰ和Ⅱ很可能不是理想的候选药物分子。假马齿苋皂苷或许能够为AQP抑制剂的化学小分子设计提供参考。

3.6 其他小分子化合物Seeliger等[113]用计算机虚拟筛选的方法找到3个独特的人AQP1抑制剂。这些小分子能够直接结合在人AQP1细胞外的通道入口处, 诱变实验显示其抑制作用与人AQP1的Lys36相关。由于Lys36在hAQP家族中属于非保守位点, 故这些小分子很可能是潜在的hAQP1选择性抑制剂。

4 总结与展望AQP1是单体相对分子质量为28 kDa的跨膜四聚体, 对水分子和部分阳离子均有一定的通透作用。研究表明, 缺氧环境促进AQP1的表达, AQP1表达上调能够改变细胞体积, 调整细胞膜电位并且激活Wnt、FAK等一系列下游信号通路, 从而影响细胞迁移、增殖及血管生成过程, 促进肿瘤的进展。关于AQP1抑制剂也从早期的四乙胺和部分重金属, 发展到近年来的乙酰唑胺、布美他尼衍生物及天然产物假马齿苋皂苷等。

AQP1与肿瘤密切相关提示, AQP1可能是潜在的肿瘤分子标志物, 对癌症的早期诊断、预测及治疗方案效果评估都有一定的临床意义。AQP1同时也是潜在的肿瘤治疗靶点, AQP1抑制剂的进一步研究对于某些过表达AQP1的癌症的治疗有一定的参考价值。

| [1] | Agre P, King LS, Yasui M, et al. Aquaporin water channels--from atomic structure to clinical medicine[J]. J Physiol, 2002, 542: 3–16. DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020818 |

| [2] | Denker BM, Smith BL, Kuhajda FP, et al. Identification, purification, and partial characterization of a novel Mr 28, 000 integral membrane protein from erythrocytes and renal tubules[J]. J Biol Chem, 1988, 263: 15634–15642. |

| [3] | Benga G. Water channel proteins (later called aquaporins) and relatives: past, present, and future[J]. IUBMB Life, 2009, 61: 112–133. DOI:10.1002/iub.v61:2 |

| [4] | Ishibashi K, Morishita Y, Tanaka Y. The evolutionary aspects of aquaporin family[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2017, 969: 35–50. DOI:10.1007/978-94-024-1057-0 |

| [5] | Ishibashi K. New members of mammalian aquaporins: AQP10-AQP12[J]. Handb Exp Pharmacol, 2009, 190: 251–262. DOI:10.1007/978-3-540-79885-9 |

| [6] | Finn RN, Chauvigne F, Hlidberg JB, et al. The lineage-specific evolution of aquaporin gene clusters facilitated tetrapod terrestrial adaptation[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9: e113686. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0113686 |

| [7] | Michalek K. Aquaglyceroporins in the kidney: present state of knowledge and prospects[J]. J Physiol Pharmacol, 2016, 67: 185–193. |

| [8] | Laforenza U, Bottino C, Gastaldi G. Mammalian aquaglyceroporin function in metabolism[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2016, 1858: 1–11. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.10.004 |

| [9] | Tomita Y, Dorward H, Yool AJ, et al. Role of aquaporin 1 signalling in cancer development and progression[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2017, 18: E299. DOI:10.3390/ijms18020299 |

| [10] | Yool AJ. Functional domains of aquaporin-1: keys to physiology, and targets for drug discovery[J]. Curr Pharm Des, 2007, 13: 3212–3221. DOI:10.2174/138161207782341349 |

| [11] | Verkman AS, Anderson MO, Papadopoulos MC. Aquaporins: important but elusive drug targets[J]. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2014, 13: 259–277. DOI:10.1038/nrd4226 |

| [12] | Baetz NW, Hoffman EA, Yool AJ, et al. Role of aquaporin-1 in trabecular meshwork cell homeostasis during mechanical strain[J]. Exp Eye Res, 2009, 89: 95–100. DOI:10.1016/j.exer.2009.02.018 |

| [13] | Zhang H, Verkman AS. Aquaporin-1 water permeability as a novel determinant of axonal regeneration in dorsal root ganglion neurons[J]. Exp Neurol, 2015, 265: 152–159. DOI:10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.01.002 |

| [14] | Nicchia GP, Stigliano C, Sparaneo A, et al. Inhibition of aquaporin-1 dependent angiogenesis impairs tumour growth in a mouse model of melanoma[J]. J Mol Med, 2013, 91: 613–623. DOI:10.1007/s00109-012-0977-x |

| [15] | Arnaoutova I, Cawley NX, Patel N, et al. Aquaporin 1 is important for maintaining secretory granule biogenesis in endocrine cells[J]. Mol Endocrinol, 2008, 22: 1924–1934. DOI:10.1210/me.2007-0434 |

| [16] | Ribatti D, Ranieri G, Annese T, et al. Aquaporins in cancer[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2014, 1840: 1550–1553. DOI:10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.09.025 |

| [17] | Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S. Key roles of aquaporins in tumor biology[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2015, 1848: 2576–2583. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.09.001 |

| [18] | Yool AJ, Brown EA, Flynn GA. Roles for novel pharmacological blockers of aquaporins in the treatment of brain oedema and cancer[J]. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol, 2010, 37: 403–409. DOI:10.1111/cep.2010.37.issue-4 |

| [19] | Nico B, Ribatti D. Role of aquaporins in cell migration and edema formation in human brain tumors[J]. Exp Cell Res, 2011, 317: 2391–2396. DOI:10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.07.006 |

| [20] | Huber VJ, Tsujita M, Nakada T. Aquaporins in drug discovery and pharmacotherapy[J]. Mol Aspects Med, 2012, 33: 691–703. DOI:10.1016/j.mam.2012.01.002 |

| [21] | Mobasheri A, Barrett-Jolley R. Aquaporin water channels in the mammary gland: from physiology to pathophysiology and neoplasia[J]. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia, 2014, 19: 91–102. DOI:10.1007/s10911-013-9312-6 |

| [22] | Nagaraju GP, Basha R, Rajitha B, et al. Aquaporins: their role in gastrointestinal malignancies[J]. Cancer Lett, 2016, 373: 12–18. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.003 |

| [23] | Li Q, Zhang B. Expression of aquaporin-1 in nasopharyngeal cancer tissues[J]. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2010, 39: 511–515. |

| [24] | El Hindy N, Bankfalvi A, Herring A, et al. Correlation of aquaporin-1 water channel protein expression with tumor angiogenesis in human astrocytoma[J]. Anticancer Res, 2013, 33: 609–613. |

| [25] | Chen R, Shi Y, Amiduo R, et al. Expression and prognostic value of aquaporin 1, 3 in cervical carcinoma in women of uygur ethnicity from Xinjiang, China[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9: e98576. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0098576 |

| [26] | Esteva-Font C, Jin BJ, Verkman AS. Aquaporin-1 gene deletion reduces breast tumor growth and lung metastasis in tumor-producing MMTV-PyVT mice[J]. FASEB J, 2014, 28: 1446–1453. DOI:10.1096/fj.13-245621 |

| [27] | Liu J, Zhang WY, Ding DG. Expression of aquaporin 1 in bladder uroepithelial cell carcinoma and its relevance to recurrence[J]. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2015, 16: 3973–3976. DOI:10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.9.3973 |

| [28] | Kang BW, Kim JG, Lee SJ, et al. Expression of aquaporin-1, aquaporin-3, and aquaporin-5 correlates with nodal metastasis in colon cancer[J]. Oncology, 2015, 88: 369–376. DOI:10.1159/000369073 |

| [29] | Park JY, Yoon G. Overexpression of aquaporin-1 is a prognostic factor for biochemical recurrence in prostate adenocarcinoma[J]. Pathol Oncol Res, 2017, 23: 189–196. DOI:10.1007/s12253-016-0145-7 |

| [30] | Li C, Li X, Wu L, et al. Elevated AQP1 expression is associated with unfavorable oncologic outcome in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma[J]. Technol Cancer Res Treat, 2017, 16: 421–427. DOI:10.1177/1533034616646288 |

| [31] | Otterbach F, Callies R, Adamzik M, et al. Aquaporin 1 (AQP1) expression is a novel characteristic feature of a particularly aggressive subgroup of basal-like breast carcinomas[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2010, 120: 67–76. DOI:10.1007/s10549-009-0370-9 |

| [32] | Yoshida T, Hojo S, Sekine S, et al. Expression of aquaporin-1 is a poor prognostic factor for stage Ⅱ and Ⅲ colon cancer[J]. Mol Clin Oncol, 2013, 1: 953–958. DOI:10.3892/mco.2013.165 |

| [33] | Wang J, Feng L, Zhu Z, et al. Aquaporins as diagnostic and therapeutic targets in cancer: how far we are?[J]. J Transl Med, 2015, 13: 96. DOI:10.1186/s12967-015-0439-7 |

| [34] | Agre P, Preston GM, Smith BL, et al. Aquaporin chip - the archetypal molecular water channel[J]. Am J Physiol, 1993, 265: F463–F476. |

| [35] | Wan XC, Steudle E, Hartung W. Gating of water channels (aquaporins) in cortical cells of young corn roots by mechanical stimuli (pressure pulses): effects of ABA and of HgCl2[J]. J Exp Bot, 2004, 55: 411–422. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erh051 |

| [36] | Fujiyoshi Y, Mitsuoka K, De Groot BL, et al. Structure and function of water channels[J]. Curr Opin Struct Biol, 2002, 12: 509–515. DOI:10.1016/S0959-440X(02)00355-X |

| [37] | Jensen MO, Tajkhorshid E, Schulten K. Electrostatic tuning of permeation and selectivity in aquaporin water channels[J]. Biophys J, 2003, 85: 2884–2899. DOI:10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74711-0 |

| [38] | Sales AD, Lobo CH, Carvalho AA, et al. Structure, function, and localization of aquaporins: their possible implications on gamete cryopreservation[J]. Genet Mol Res, 2013, 12: 6718–6732. DOI:10.4238/2013.December.13.5 |

| [39] | Boassa D, Yool AJ. Single amino acids in the carboxyl terminal domain of aquaporin-1 contribute to cGMP-dependent ion channel activation[J]. BMC Physiol, 2003, 3: 12. DOI:10.1186/1472-6793-3-12 |

| [40] | Yu J, Yool AJ, Schulten K, et al. Mechanism of gating and ion conductivity of a possible tetrameric pore in aquaporin-1[J]. Structure, 2006, 14: 1411–1423. DOI:10.1016/j.str.2006.07.006 |

| [41] | Herrera M, Garvin JL. Aquaporins as gas channels[J]. Pflugers Arch, 2011, 462: 623–630. DOI:10.1007/s00424-011-1002-x |

| [42] | Campbell EM, Birdsell DN, Yool AJ. The activity of human aquaporin 1 as a cGMP-gated cation channel is regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation in the carboxyl-terminal domain[J]. Mol Pharmacol, 2012, 81: 97–105. DOI:10.1124/mol.111.073692 |

| [43] | Kourghi M, Pei JV, De Ieso ML, et al. Fundamental structural and functional properties of aquaporin ion channels found across the kingdoms of life[J]. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol, 2017. DOI:10.1111/1440-1681.12900 |

| [44] | Yool AJ, Weinstein AM. New roles for old holes: ion channel function in aquaporin-1[J]. News Physiol Sci, 2002, 17: 68–72. |

| [45] | Andersen AP, Moreira JM, Pedersen SF. Interactions of ion transporters and channels with cancer cell metabolism and the tumour microenvironment[J]. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2014, 369: 20130098. DOI:10.1098/rstb.2013.0098 |

| [46] | Xia J, Wang H, Li S, et al. Ion channels or aquaporins as novel molecular targets in gastric cancer[J]. Mol Cancer, 2017, 16: 54. DOI:10.1186/s12943-017-0622-y |

| [47] | Azimi I, Monteith GR. Plasma membrane ion channels and epithelial to mesenchymal transition in cancer cells[J]. Endocr Relat Cancer, 2016, 23: R517–R525. |

| [48] | Schwab A, Fabian A, Hanley PJ, et al. Role of ion channels and transporters in cell migration[J]. Physiol Rev, 2012, 92: 1865–1913. DOI:10.1152/physrev.00018.2011 |

| [49] | Huttenlocher A. Cell polarization mechanisms during directed cell migration[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 2005, 7: 336–337. DOI:10.1038/ncb0405-336 |

| [50] | Michaelis UR. Mechanisms of endothelial cell migration[J]. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2014, 71: 4131–4148. DOI:10.1007/s00018-014-1678-0 |

| [51] | Kamath K, Smiyun G, Wilson L, et al. Mechanisms of inhibition of endothelial cell migration by taxanes[J]. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken), 2014, 71: 46–60. DOI:10.1002/cm.v71.1 |

| [52] | Hamm MJ, Kirchmaier BC, Herzog W. Sema3d controls collective endothelial cell migration by distinct mechanisms via Nrp1 and PlxnD1[J]. J Cell Biol, 2016, 215: 415–430. DOI:10.1083/jcb.201603100 |

| [53] | Papadopoulos MC, Verkman AS. Aquaporin water channels in the nervous system[J]. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2013, 14: 265–277. DOI:10.1038/nrn3468 |

| [54] | Hu J, Verkman AS. Increased migration and metastatic potential of tumor cells expressing aquaporin water channels[J]. FASEB J, 2006, 20: 1892–1894. DOI:10.1096/fj.06-5930fje |

| [55] | Jiang Y. Aquaporin-1 activity of plasma membrane affects HT20 colon cancer cell migration[J]. IUBMB Life, 2009, 61: 1001–1009. DOI:10.1002/iub.v61:10 |

| [56] | Meng FB, Rui YF, Xu LL, et al. Aqp1 enhances migration of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells through regulation of FAK and beta-catenin[J]. Stem Cells Dev, 2014, 23: 66–75. |

| [57] | Wang Z, Dabrosin C, Yin X, et al. Broad targeting of angiogenesis for cancer prevention and therapy[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2015, 35: S224–S243. DOI:10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.01.001 |

| [58] | Munaron L. Systems biology of ion channels and transporters in tumor angiogenesis: an omics view[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2015, 1848: 2647–2656. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.10.031 |

| [59] | Nico B, Ribatti D. Aquaporins in tumor growth and angiogenesis[J]. Cancer Lett, 2010, 294: 135–138. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2010.02.005 |

| [60] | Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC, Hara-Chikuma M, et al. Impairment of angiogenesis and cell migration by targeted aquaporin-1 gene disruption[J]. Nature, 2005, 434: 786–792. DOI:10.1038/nature03460 |

| [61] | Moens S, Goveia J, Stapor PC, et al. The multifaceted activity of VEGF in angiogenesis - implications for therapy responses[J]. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2014, 25: 473–482. DOI:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.07.009 |

| [62] | Pan H, Sun CC, Zhou CY, et al. Expression of aquaporin-1 in normal, hyperplasic, and carcinomatous endometria[J]. Int J Gynecol Obstet, 2008, 101: 239–244. DOI:10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.12.006 |

| [63] | Kaneko K, Yagui K, Tanaka A, et al. Aquaporin 1 is required for hypoxia-inducible angiogenesis in human retinal vascular endothelial cells[J]. Microvasc Res, 2008, 75: 297–301. DOI:10.1016/j.mvr.2007.12.003 |

| [64] | Dorward HS, Du A, Bruhn MA, et al. Pharmacological blockade of aquaporin-1 water channel by AqB013 restricts migration and invasiveness of colon cancer cells and prevents endothelial tube formation in vitro[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2016, 35: 36. DOI:10.1186/s13046-016-0310-6 |

| [65] | Galan-Cobo A, Ramirez-Lorca R, Echevarria M. Role of aquaporins in cell proliferation: what else beyond water permeability?[J]. Channels, 2016, 10: 185–201. DOI:10.1080/19336950.2016.1139250 |

| [66] | Hoque MO, Soria JC, Woo JH, et al. Aquaporin 1 is overexpressed in lung cancer and stimulates NIH-3T3 cell proliferation and anchorage-independent growth[J]. Am J Pathol, 2006, 168: 1345–1353. DOI:10.2353/ajpath.2006.050596 |

| [67] | Galan-Cobo A, Sanchez-Silva R, Serna A, et al. Cellular overexpression of aquaporins slows down the natural HIF-2 alpha degradation during prolonged hypoxia[J]. Gene, 2013, 522: 18–26. DOI:10.1016/j.gene.2013.03.075 |

| [68] | Wu Z, Li S, Liu J, et al. RNAi-mediated silencing of AQP1 expression inhibited the proliferation, invasion and tumorigenesis of osteosarcoma cells[J]. Cancer Biol Ther, 2015, 16: 1332–1340. DOI:10.1080/15384047.2015.1070983 |

| [69] | Klebe S, Griggs K, Cheng Y, et al. Blockade of aquaporin 1 inhibits proliferation, motility, and metastatic potential of mesothelioma in vitro but not in an in vivo model[J]. Dis Markers, 2015, 2015: 286719. |

| [70] | Galan-Cobo A, Ramirez-Lorca R, Toledo-Aral JJ, et al. Aquaporin-1 plays important role in proliferation by affecting cell cycle progression[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2016, 231: 243–256. DOI:10.1002/jcp.v231.1 |

| [71] | Pedersen SF, Hoffmann EK, Novak I. Cell volume regulation in epithelial physiology and cancer[J]. Front Physiol, 2013, 4: 233. |

| [72] | Lerner UH, Ohlsson C. The WNT system: background and its role in bone[J]. J Intern Med, 2015, 277: 630–649. DOI:10.1111/joim.12368 |

| [73] | Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease[J]. Cell, 2012, 149: 1192–1205. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012 |

| [74] | Baarsma HA, Konigshoff M, Gosens R. The WNT signaling pathway from ligand secretion to gene transcription: molecular mechanisms and pharmacological targets[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2013, 138: 66–83. DOI:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.01.002 |

| [75] | Matthijs Blankesteijn W, Hermans KC. Wnt signaling in atherosclerosis[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2015, 763: 122–130. DOI:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.05.023 |

| [76] | Mccubrey JA, Rakus D, Gizak A, et al. Effects of mutations in Wnt/beta-catenin, hedgehog, Notch and PI3K pathways on GSK-3 activity-diverse effects on cell growth, metabolism and cancer[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2016, 1863: 2942–2976. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.004 |

| [77] | Koziński K, Dobrzyń A. Wnt signaling pathway--its role in regulation of cell metabolism[J]. Postepy Hig Med Dosw, 2013, 67: 1098–1108. DOI:10.5604/17322693.1077719 |

| [78] | Monzani E, Bazzotti R, Perego C, et al. AQP1 is not only a water channel: it contributes to cell migration through Lin7/ beta-catenin[J]. PLoS One, 2009, 4: e6167. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0006167 |

| [79] | Yun X, Jiang H, Lai N, et al. The C-terminal tail of aquaporin 1 modulates beta-catenin expression in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells[J]. FASEB J, 2014, 28: 1175.2. |

| [80] | Polette M, Mestdagt M, Bindels S, et al. β-Catenin and ZO-1: shuttle molecules involved in tumor invasion-associated epithelial-mesenchymal transition processes[J]. Cells Tissues Organs, 2007, 185: 61–65. DOI:10.1159/000101304 |

| [81] | Sulzmaier FJ, Jean C, Schlaepfer DD. FAK in cancer: mechanistic findings and clinical applications[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2014, 14: 598–610. DOI:10.1038/nrc3792 |

| [82] | Tai YL, Chen LC, Shen TL. Emerging roles of focal adhesion kinase in cancer[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2015, 2015: 690690. |

| [83] | Parri M, Chiarugi P. Rac and Rho GTPases in cancer cell motility control[J]. Cell Commun Signal, 2010, 8: 23. DOI:10.1186/1478-811X-8-23 |

| [84] | Singh D, Srivastava SK, Chaudhuri TK, et al. Multifaceted role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)[J]. Front Mol Biosci, 2015, 2: 19. |

| [85] | Wei X, Dong J. Aquaporin 1 promotes the proliferation and migration of lung cancer cell in vitro[J]. Oncol Rep, 2015, 34: 1440–1448. DOI:10.3892/or.2015.4107 |

| [86] | Friedl P, Wolf K. Tumour-cell invasion and migration: diversity and escape mechanisms[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2003, 3: 362–374. DOI:10.1038/nrc1075 |

| [87] | Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Tumor angiogenesis: MMP-mediated induction of intravasation- and metastasis-sustaining neovasculature[J]. Matrix Biol, 2015, 44-46: 94–112. DOI:10.1016/j.matbio.2015.04.004 |

| [88] | Shay G, Lynch CC, Fingleton B. Moving targets: emerging roles for MMPs in cancer progression and metastasis[J]. Matrix Biol, 2015, 44-46: 200–206. DOI:10.1016/j.matbio.2015.01.019 |

| [89] | Candido S, Abrams SL, Steelman LS, et al. Roles of NGAL and MMP-9 in the tumor microenvironment and sensitivity to targeted therapy[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2016, 1863: 438–448. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.08.010 |

| [90] | Sein TT, Thant AA, Hiraiwa Y, et al. A role for FAK in the concanavalin A-dependent secretion of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and-9[J]. Oncogene, 2000, 19: 5539–5542. DOI:10.1038/sj.onc.1203932 |

| [91] | Wu B, Crampton SP, Hughes CCW. Wnt signaling induces matrix metalloproteinase expression and regulates T cell transmigration[J]. Immunity, 2007, 26: 227–239. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2006.12.007 |

| [92] | Wilson WR, Hay MP. Targeting hypoxia in cancer therapy[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2011, 11: 393–410. DOI:10.1038/nrc3064 |

| [93] | Hayashi Y, Edwards NA, Proescholdt MA, et al. Regulation and function of aquaporin-1 in glioma cells[J]. Neoplasia, 2007, 9: 777–787. DOI:10.1593/neo.07454 |

| [94] | Abreu-Rodriguez I, Sanchez Silva R, Martins AP, et al. Functional and transcriptional induction of aquaporin-1 gene by hypoxia; analysis of promoter and role of Hif-1 alpha[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6: e28385. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0028385 |

| [95] | Tanaka A, Sakurai K, Kaneko K, et al. The role of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 binding site in the induction of aquaporin-1 mRNA expression by hypoxia[J]. DNA Cell Biol, 2011, 30: 539–544. DOI:10.1089/dna.2009.1014 |

| [96] | Nave M, Castro RE, Rodrigues CM, et al. Nanoformulations of a potent copper-based aquaporin inhibitor with cytotoxic effect against cancer cells[J]. Nanomedicine (Lond), 2016, 11: 1817–1830. DOI:10.2217/nnm-2016-0086 |

| [97] | Yool AJ, Morelle J, Cnops Y, et al. AqF026 is a pharmacologic agonist of the water channel aquaporin-1[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2013, 24: 1045–1052. DOI:10.1681/ASN.2012080869 |

| [98] | Pei JV, Kourghi M, De Ieso ML, et al. Differential inhibition of water and ion channel activities of mammalian aquaporin-1 by two structurally related bacopaside compounds derived from the medicinal plant bacopa monnieri[J]. Mol Pharmacol, 2016, 90: 496–507. DOI:10.1124/mol.116.105882 |

| [99] | Niemietz CM, Tyerman SD. New potent inhibitors of aquaporins: silver and gold compounds inhibit aquaporins of plant and human origin[J]. FEBS Lett, 2002, 531: 443–447. DOI:10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03581-0 |

| [100] | Preston GM, Jung JS, Guggino WB, et al. The mercury-sensitive residue at cysteine-189 in the chip28 water channel[J]. J Biol Chem, 1993, 268: 17–20. |

| [101] | Brooks HL, Regan JW, Yool AJ. Inhibition of aquaporin-1 water permeability by tetraethylammonium: involvement of the loop E pore region[J]. Mol Pharmacol, 2000, 57: 1021–1026. |

| [102] | Yool AJ, Brokl OH, Pannabecker TI, et al. Tetraethylammonium block of water flux in aquaporin-Ⅰ channels expressed in kidney thin limbs of Henle's loop and a kidney-derived cell line[J]. BMC Physiol, 2002, 2: 1–8. DOI:10.1186/1472-6793-2-1 |

| [103] | Kassamali R, Sica DA. Acetazolamide: a forgotten diuretic agent[J]. Cardiol Rev, 2011, 19: 276–278. DOI:10.1097/CRD.0b013e31822b4939 |

| [104] | Gao J, Wang X, Chang Y, et al. Acetazolamide inhibits osmotic water permeability by interaction with aquaporin-1[J]. Anal Biochem, 2006, 350: 165–170. DOI:10.1016/j.ab.2006.01.003 |

| [105] | Xiang Y, Ma B, Li T, et al. Acetazolamide suppresses tumor metastasis and related protein expression in mice bearing Lewis lung carcinoma[J]. Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2002, 23: 745–751. |

| [106] | Mu SM, Ji XH, Ma B, et al. Differential protein analysis in rat renal proximal tubule epithelial cells in response to acetazolamide and its relation with the inhibition of AQP1[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2003, 38: 169–172. |

| [107] | Ma B, Xiang Y, Mu SM, et al. Effects of acetazolamide and anordiol on osmotic water permeability in AQP1-cRNA injected Xenopus oocyte[J]. Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2004, 25: 90–97. |

| [108] | Xiang Y, Ma B, Li T, et al. Acetazolamide inhibits aquaporin-1 protein expression and angiogenesis[J]. Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2004, 25: 812–816. |

| [109] | Xiang Y, Ma B, Yu HM, et al. The protein profile of acetazolamide-treated sera in mice bearing Lewis neoplasm[J]. Life Sci, 2004, 75: 1277–1285. DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2003.12.032 |

| [110] | Zhang J, An Y, Gao J, et al. Aquaporin-1 translocation and degradation mediates the water transportation mechanism of acetazolamide[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7: e45976. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0045976 |

| [111] | Kourghi M, Pei JV, De Ieso ML, et al. Bumetanide derivatives AqB007 and AqB011 selectively block the aquaporin-1 ion channel conductance and slow cancer cell migration[J]. Mol Pharmacol, 2016, 89: 133–140. |

| [112] | Migliati E, Meurice N, Dubois P, et al. Inhibition of aquaporin-1 and aquaporin-4 water permeability by a derivative of the loop diuretic bumetanide acting at an internal pore-occluding binding site[J]. Mol Pharmacol, 2009, 76: 105–112. DOI:10.1124/mol.108.053744 |

| [113] | Seeliger D, Zapater C, Krenc D, et al. Discovery of novel human aquaporin-1 blockers[J]. ACS Chem Biol, 2013, 8: 249–256. DOI:10.1021/cb300153z |

2018, Vol. 53

2018, Vol. 53