| 视觉空间工作记忆组间差异的神经机制 |

2. 西南大学心理学部,重庆 400715;

3. 中国人民大学信息资源管理学院,北京 100872;

4. 宁波大学外国语学院,宁波 315211

工作记忆(working memory, WM)是大脑临时保持和操作信息的至关重要系统(Baddeley, 1992, 2003a, 2003b),它与执行注意有密切关联(Engle, 2018)。WM能力是WM的重要特征。它指大脑在复杂WM任务中编码、加工和检索信息的能力(Barrett, Tugade, & Engle, 2004; Kane, Bleckley, Conway, & Engle, 2001; Unsworth & Spillers, 2010)。视觉空间WM能力是人类WM能力的一个重要方面。研究者通常采用高干扰任务(被试在记忆目标刺激时,需要排除分心物的干扰)和高执行任务(被试在记忆目标时,需要控制注意和管理资源分配,从而完成对目标的操作)来考察人类的视觉空间WM能力及其特征。

研究发现,视觉空间WM能力具有明显的组间差异。这可能是由于高视觉空间WM能力(高WM能力)组比低视觉空间WM能力(低WM能力)组具有更强的执行注意能力和过滤分心物的能力。在高干扰任务中,高WM能力组比低WM能力组完成得更好;在低干扰任务中,两组成绩无显著差异(Conway & Engle, 1994; Conway, Kane, & Engle, 2003; Kane et al., 2001; Kane & Engle, 2000, 2003; Redick & Engle, 2006; Rosen & Engle, 1997; Unsworth, Schrock, & Engle, 2004)。这可能是由于高WM能力组调用了更强的执行注意(控制注意和管理资源分配的能力)(McNab & Klingberg, 2008; Osaka et al., 2003, 2004)。

高WM能力组在解决冲突和筛选干扰信息方面也更具优势(Engle, 2010; Unsworth & Engle, 2007; Vogel, McCollough, & Machizawa, 2005; Zanto & Gazzaley, 2009),这可能由于高WM能力组能有效调用执行注意阻止分心物干扰。例如,在高干扰任务中,高WM能力组更容易阻止分心物进入记忆保持阶段(Jost, Bryck, Vogel, & Mayr, 2011; Vogel & Machizawa, 2004; Zanto & Gazzaley, 2009)。Vogel等(2005)采用高干扰任务(例如,分心任务)考察了视觉空间WM的组间差异。结果发现,高WM能力组在表征相关项目上更有效率,而低WM能力组无效地编码和维持了无关项目。这表明,高WM能力组可能通过一种神经抑制机制阻止有限的WM容量超载,从而有效地将无关项目排除在记忆之外(Zanto & Gazzaley, 2009)。

然而,现有研究大都采用高干扰任务考察视觉空间WM的组间差异,而在高执行任务(例如,心理旋转任务)中,视觉空间WM的组间差异及其特征还不清楚。本研究记录了高、低WM能力被试完成视觉空间WM维持任务(低执行任务)和操作任务(高执行任务)时的行为和事件相关电位(event−related potentials, ERPs)数据,探讨了视觉空间WM的组间差异及神经机制。由于视觉空间维持(即保持视觉空间信息,以用于进一步的操作和巩固信息)和视觉空间操作(即在最初编码视觉空间信息的基础上操作这些信息)是视觉空间WM系统的两种主要功能(Cohen et al., 1997; Jolles, Kleibeuker, Rombouts, & Crone, 2011; Thakkar & Park, 2012),所以采用这两类任务能考察人类的视觉空间WM能力。

视觉空间WM维持任务是一个延迟再认任务,即当记忆刺激呈现后,被试需要在固定的时间内保持两个项目的形状及其位置。视觉空间WM操作任务是一个心理旋转任务,即当记忆刺激呈现后,在随后的延迟阶段,被试必须在心理顺(或逆)时针旋转刺激的位置144°,使它们处于水平状态。先前研究揭示,完成视觉空间WM操作任务比完成视觉空间WM维持任务需要更多的执行注意参与(D’Esposito, Postle, Ballard, & Lease, 1999; Glahn et al., 2002; Liu, Guo, & Luo, 2010; Morgan et al., 2010; Owen et al., 1999)。

基于先前研究(Beste, Heil, & Konrad, 2010; Gazzaley, Cooney, Rissman, & D’Esposito, 2005),为有效测量WM成绩,本研究首先平均了每名被试在两个任务中的正确率(因为完成两个任务需要共同的WM能力,并且任务类型是组内变量),然后从小到大排序,再采用中位数区分高、低WM组。先前研究也采用了类似策略来划分高、低WM组(Beste et al., 2010; Vogel et al., 2005)。

由于完成视觉空间WM操作任务需要大脑调用很强的执行注意,而高WM能力组比低WM能力组的执行注意能力更具优势,所以本研究预测,在视觉空间WM操作任务中,高WM组比低WM组的成绩显著更好,两组被试的ERPs特征有显著差异。然而,由于完成视觉空间WM维持任务比操作任务所需的执行注意更弱(D’Esposito et al., 1999; Glahn et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2010; Morgan et al., 2010; Owen et al., 1999),那么高、低WM组被试的执行注意能力差异可能对维持任务的完成无显著影响。所以,在维持任务中,两组被试的成绩可能无显著差异。另外,本研究预测操作任务和维持任务引发的ERPs特征有显著差异。

2 方法 2.1 被试28位右利手被试(其中,11位女性;M=20.96岁,SD=1.12岁)有偿参与本研究。视力或矫正视力正常,色觉正常,未参加过类似实验。在实验前均签署知情同意书。西南大学人类研究伦理委员会同意实施本研究。

2.2 器材和设计实验程序用E-Prime 1.0编制并运行,被试在标准QWERTY键盘上做按键反应。所有刺激被呈现在DELL17英寸的液晶显示器屏幕中央,屏幕分辨率为1024×768像素,颜色为真彩色,刷新率为85 Hz,背景颜色为灰色。被试距屏幕的距离约90 cm。记忆、延迟和测试阶段的刺激被呈现在一个黑色圆圈内(视角大约为7.43°)。

采用2×2混合因素设计,任务类型(维持、操作)是被试内因素,WM分组(高、低)是被试间因素。其中,低WM组14人,高WM组14人。

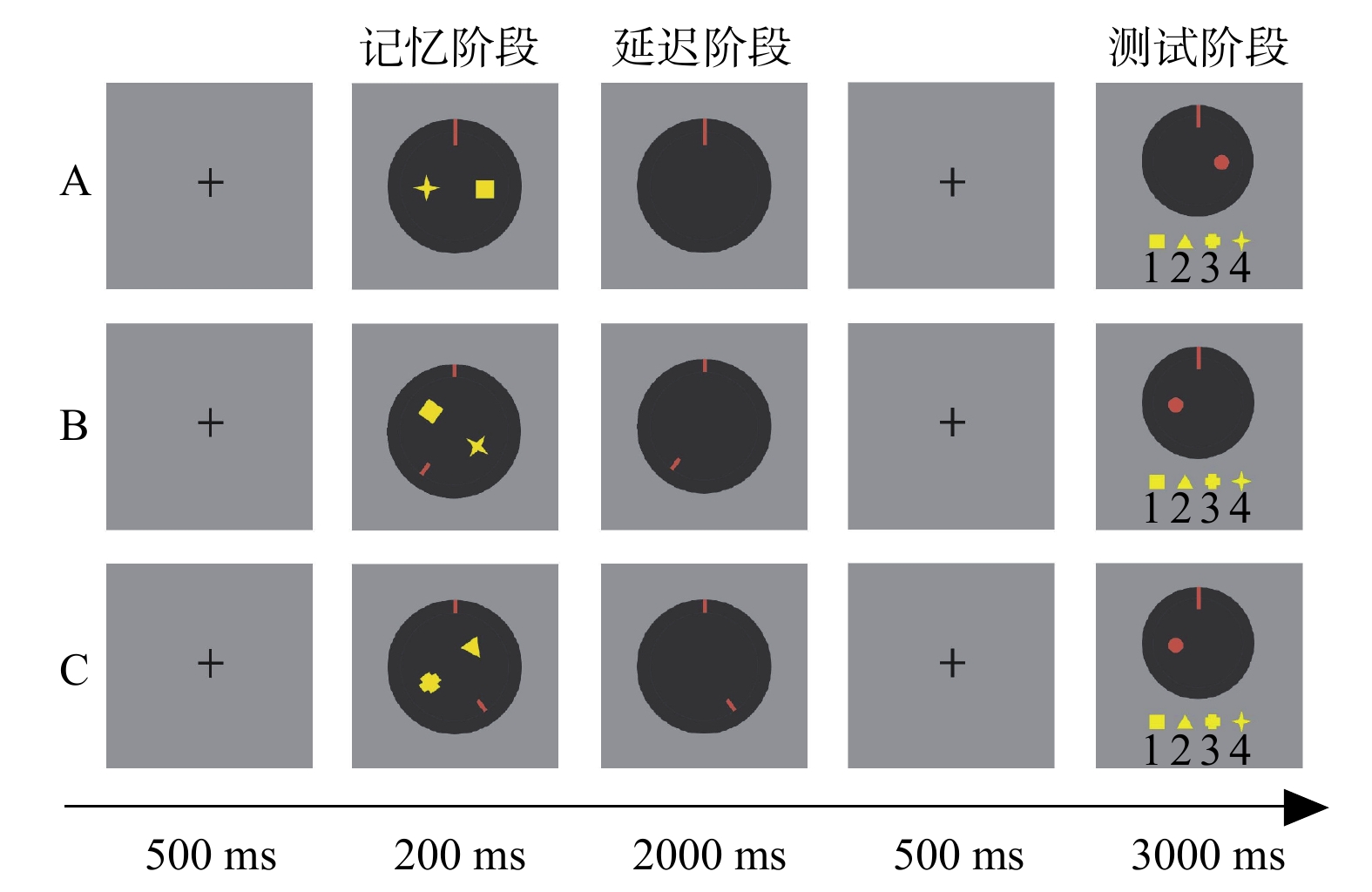

实验包含记忆、延迟和测试三个阶段(参见图1)。在记忆阶段,对于每个试次,同时呈现从四个形状(正方形、等边三角形、宽十字形和四角星形)中随机选择的两个不同形状和短红线,每个形状的视角大约为0.62°×0.62°。被试需要记忆这两个不同的形状及其位置。在延迟阶段,两个形状消失,短红线仍保留在屏幕上,以暗示怎样完成该任务。在延迟阶段,如果只有一条红线垂直呈现在圆圈顶端(参见图1A),当前的任务是维持任务,即保持记忆阶段图像的角度及其位置;如果有两条短红线(参见图1B、图1C),一条垂直呈现在圆圈顶端,另一条呈现在与它大约呈144°的位置,当前的任务是操作任务,即心理旋转记忆阶段图像的角度144°(顺时针或逆时针),把倾斜线以最短的距离旋转成垂直线。在测试阶段中,一个视角大约为0.62°的红色小圆圈或左或右呈现在目标形状的位置上,指示正确的反应。被试需要根据红色小圆圈呈现的位置上所指示的目标形状做出反应。当目标形状分别是正方形、等边三角形、宽十字形和四角星形时,被试分别按“1”、“2”、“3”、“4”键。目标形状和反应键的映射规则始终呈现在屏幕下方。

2.3 程序实验程序见图1。在每个试次中,被试需要在测试阶段又快又准确的做出反应,反应后刺激消失。试次之间的间隔时间固定为是1000 ms。在正式实验前,所有被试完成预备实验,实验程序和正式实验的一致。被试在预备实验中的准确率高于80%时才进入正式实验。正式实验共包含两个block。每个block共80个试次,维持任务和旋转任务各40个试次,这些试次随机呈现。

|

| 图 1 实验程序和任务类型 |

2.4 脑电(electroencephalography, EEG)记录和预处理

EEG记录方法见Tang,Hu,Lei,Li和Chen(2015)。首先采用Vision Analyzer软件对EEG数据做参考,参考电极为双侧乳突,再进行30 Hz的低通滤波,0.1 Hz的高通滤波。然后采用EEGLAB(Delorme & Makeig, 2004)对数据进行分段,分析时程从记忆刺激呈现前200 ms到呈现后2200 ms,采用先于记忆刺激呈现前的时间间隔(−200 ms到0 ms)为基线,并做基线校正。去伪迹方法见Tang等(2015)。最后再做基线校正。

2.5 ERPs分析基于先前研究(Awh, Anllo-Vento, & Hillyard, 2000; Jha, 2002; Morgan et al., 2010),本研究分析P1、N1和P3b峰值及慢波(slow waves)平均波幅。由于P1和N1在双侧后顶区(P5、P6、P7、P8、PO7和PO8)的活动最强,所以我们在该区域分别测量P1和N1峰值,其峰潜伏期分别为70~120 ms和130~200 ms。在Pz点测量P3b峰值(Boucher et al., 2010),潜伏期为390~470 ms;分别在八个感兴趣区域(regions of interests, ROIs)分析慢波平均波幅(Hsieh, Ekstrom, & Ranganath, 2011):左前额叶( F3、F5和FC3)、中前额叶(Fz和FCz)、右前额叶(F4、F6和FC4)、左侧中顶区(C3、CP3和CP5)、中顶区(Cz和CPz)、右侧中顶区(C4、CP4和CP6)、左侧后顶区(P5、P7和PO7)、右侧后顶区(P6、P8和PO8)。分析时程分别为700~1200 ms、1200~1700 ms和1700~2200 ms。

3 结果错误试次和反应时(response time, RT)超出均值±3个标准差的异常值被剔除(Miyake et al., 2000)。最后,每个任务最少包含48个有效试次。当自由度大于等于2时,采用Mauchly’s test of sphericity矫正p值。如果违反sphericity假设,实施Greenhouse-Geisser矫正。为了控制多重比较问题,采用Bonferroni方法校正p值。

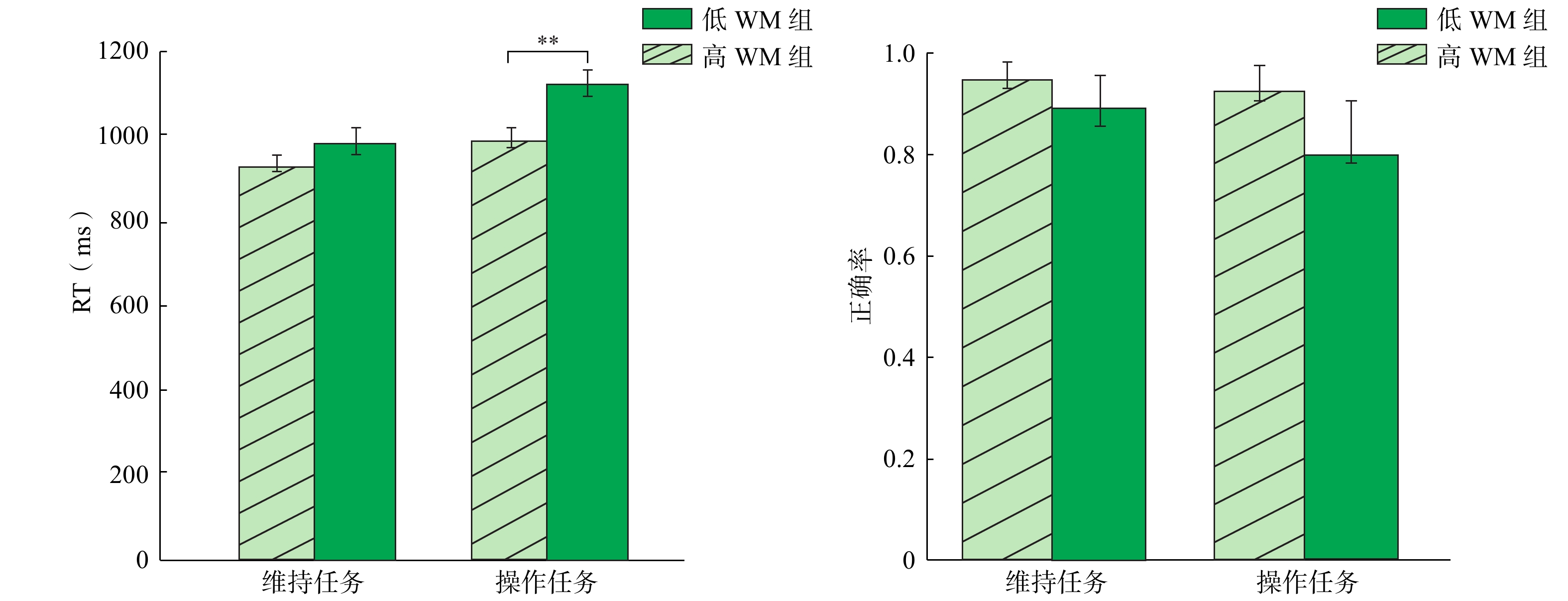

3.1 行为结果图2展示了平均RT(左)和正确率(右)。

|

| 注:**p<0.01,误差线代表±1个标准差,以下同。 图 2 反应时和正确率结果 |

以任务类型(维持、操作)和WM分组(高、低)为自变量,对RT实施两因素混合方差分析(analysis of variance, ANOVA)。结果发现,任务类型和WM分组主效应都显著,所有F(1, 26)>5,p<0.05,η

与RT的分析相似,对于正确率,任务类型和WM分组的主效应都显著,所有F(1, 26)>5,p<0.05,η

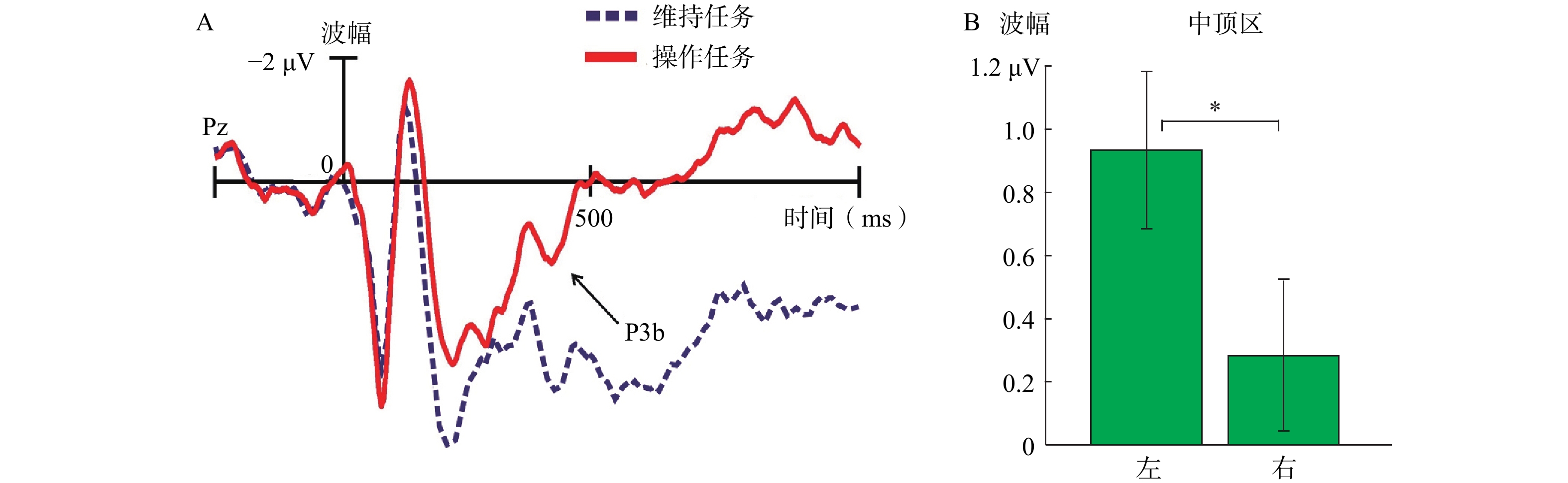

对于N1(130~200 ms)和P1(70~120 ms)峰值,两因素混合方差分析没有发现显著差异,F(1, 26)<1。对于P3b(390~470 ms,Pz)峰值,两因素混合方差分析发现了显著的任务类型主效应,F(1, 26)=16.88,p<0.01,η

|

| 注:*p<0.05,以下同。图A,维持任务和操作任务引发的总平均ERPs;图B,左侧和右侧中顶区的总平均慢波波幅(700~2200 ms)。 图 3 Pz点上的总平均波幅和中顶区慢波波幅 |

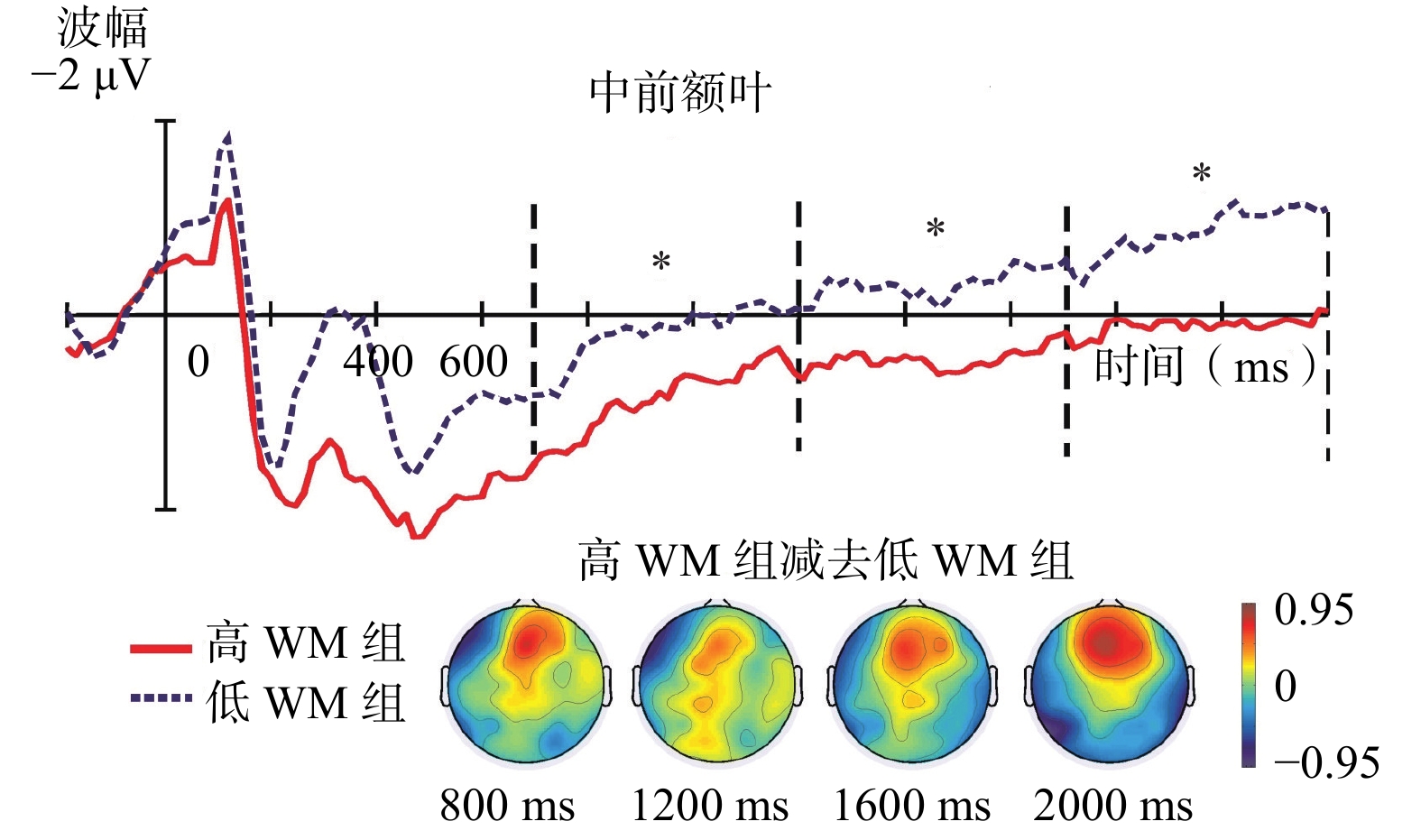

对于左前额叶、右前额叶和中前额叶慢波平均波幅,分别实施三因素混合方差分析。被试内因素是任务类型(维持、操作)和时间窗(700~1200 ms、1200~1700 ms和1700~2200 ms),被试间因素是WM分组(高、低)。在左前额叶,任务类型主效应显著,F(1, 26)=4.78,p<0.05,η

对于中顶区慢波波幅,本研究以任务类型(维持、操作)、时间窗(700~1200 ms、1200~1700 ms和1700~2200 ms)、大脑半球(左、右)和WM分组(高、低)为变量,实施四因素混合方差分析。结果发现,大脑半球主效应显著,F(1, 26)=6.27,p<0.05,η

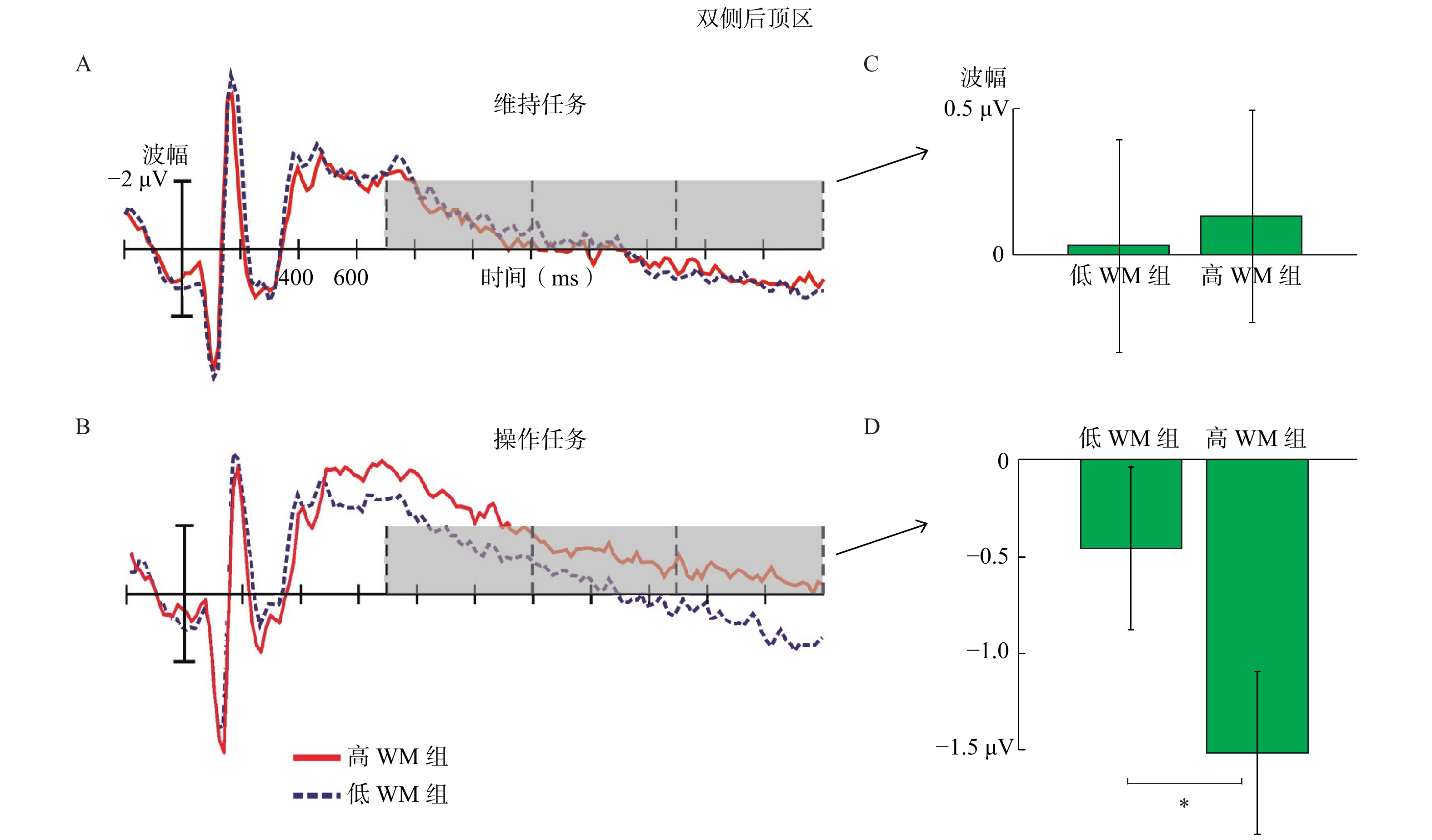

后顶区慢波波幅的分析方法和中顶区的类似。结果发现,任务类型主效应显著,F(1, 26)=14.38,p<0.01,η

|

| 图 4 中前额叶总平均ERPs波形和高、低WM组的差异波地形图 |

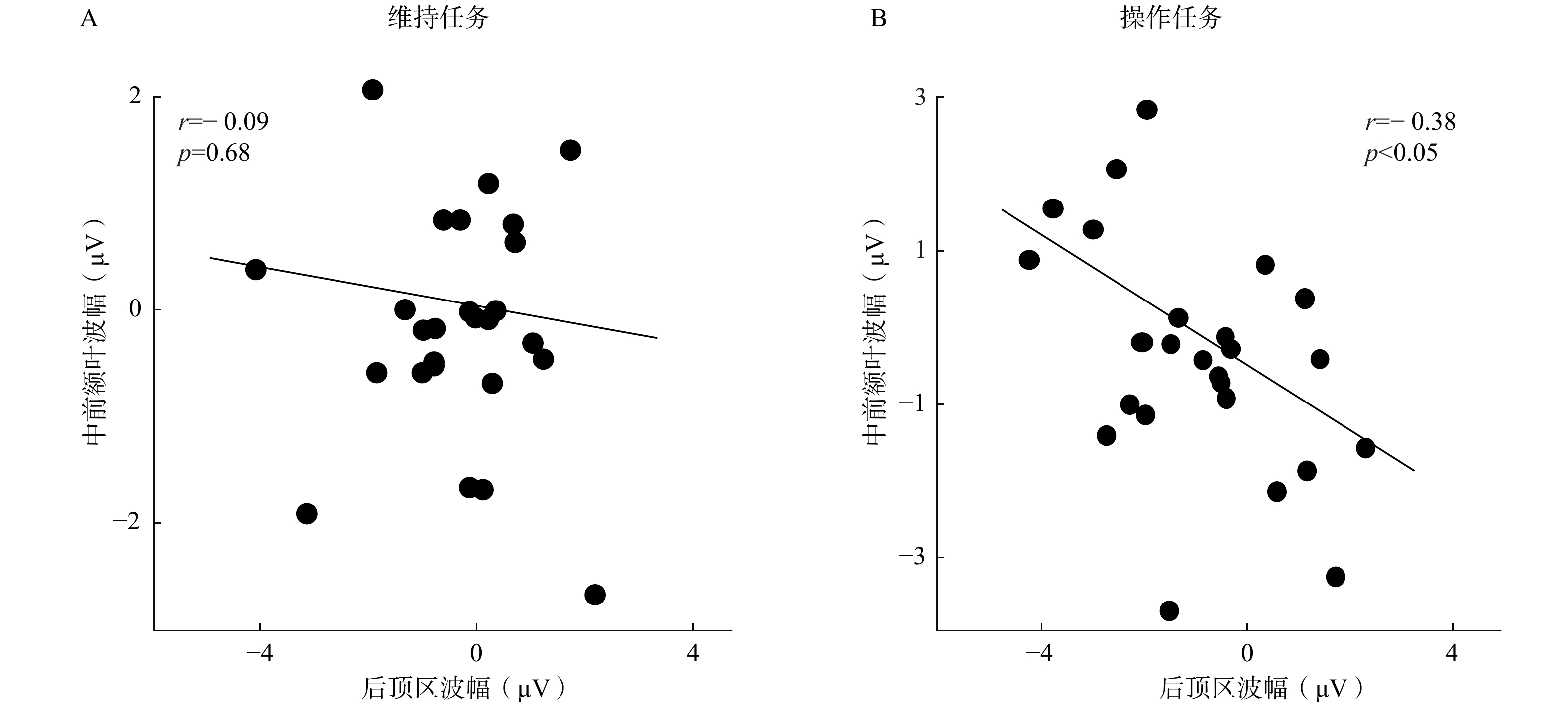

为考察中前额叶活动和后顶区活动之间的关系,本研究分别对维持任务和操作任务中的慢波波幅(700~2200 ms)实施皮尔逊相关分析。对于高WM组,在维持任务中,中前额叶波幅和后顶区波幅无显著相关,r=−0.09,p=0.68(参见图6A);在操作任务中,中前额叶波幅和后顶区波幅显著负相关,r=−0.38,p<0.05(参见图6B)。对于低WM组,在维持任务和操作任务中,所有相关关系都不显著,所有r<−0.13,p>0.49。

|

| 图 5 维持任务和操作任务中的波形图和平均波幅 |

|

| 图 6 高WM组波幅的相关分析结果 |

4 讨论

本研究考察了视觉空间WM维持和操作的组间差异及其神经机制。RT结果显示,在操作任务中,高WM组比低WM组反应更快;在维持任务中,两者无显著差异(参见图2)。这些结果与本研究的预期一致,即与低WM组相比,高WM组能显著更好地完成操作任务;但在维持任务中,两组成绩无显著差异。ERPs结果进一步阐明了其神经机制。

研究发现,WM任务和心理旋转任务能引发P3b成分(Heil & Rolke, 2002; Kok, 2001; Morgan, Klein, Boehm, Shapiro, & Linden, 2008)。在心理旋转任务中,P3b波幅随旋转角度增加而减小(Heil, 2002; Wijers, Otten, Feenstra, Mulder, & Mulder, 1989)。心理旋转需要WM加工,并消耗注意和认知资源;旋转角度越大,消耗的加工资源越多,P3b波幅越小(Polich, 2007)。本研究发现,维持任务(旋转0°)中的P3b波幅(390~470 ms)显著大于操作任务中的波幅(旋转144°)(参见图3A),这与先前研究一致。可能完成操作任务需要辨别旋转目标的方位和角度,因此需要更多的注意和WM加工。

大脑顶区的负走向慢波与WM加工有关,其波幅越大,WM加工越强(Bosch, Mecklinger, & Friederici, 2001; Mecklinger & Pfeifer, 1996; Rösler, Heil, & Röder, 1997; Vogel & Machizawa, 2004)。另外,左顶区可能负责语言信息的储存和处理(Jonides et al., 1998; Rama, Sala, Gillen, Pekar, & Courtney, 2001; Smith, Jonides, & Koeppe, 1996; Vallar, Di Betta, & Silveri, 1997),右顶区可能负责处理视觉空间信息(Baddeley, 2003b; Corballis, 2003; Smith & Jonides, 1997; Smith et al., 1996)。本研究发现,右侧中顶区的负慢波波幅(700~2200 ms)显著更大(参见图3B)。这表明,完成维持任务和操作任务可能更需要右侧中顶区参与。

本研究发现,在操作任务中,高WM组比低WM组的中前额叶正慢波波幅(700~2200 ms)显著更大(参见图4)。基于先前研究,执行注意的作用在于管理和监测认知资源的分配,主要涉及到前额叶参与(D’Esposito et al., 1995; Serino et al., 2006)。并且,前额叶正慢波波幅越大,执行注意越强(Liu et al., 2010; Mecklinger & Pfeifer, 1996)。所以,本研究可能表明,在操作任务中,高WM组比低WM组能调用更强的执行注意来有效管理和监测认知资源的分配,这使得高WM组能更有效完成操作任务。另外,在左前额叶,操作任务比维持任务引发了更大的正慢波。这可能表明,完成操作任务需要更多执行注意加工的参与。

在操作任务中,在双侧后顶区,高WM组比低WM组的负慢波波幅(700~2200 ms)显著更大(参见图5)。由于双侧后顶区负慢波可能反映了WM中视觉(物体)表征和存储加工,并且视觉空间操作任务高度依赖于视觉空间表征(Hyun & Luck, 2007; Prime & Jolicoeur, 2010),所以负慢波波幅越大意味着大脑运用越多的WM存储和表征视觉图像(Bosch et al., 2001; Prime & Jolicoeur, 2010; Rösler et al., 1997; Vogel & Machizawa, 2004)。因此,在视觉物体加工阶段,高WM组可能通过调用更多的WM加工资源(Emrich, Lockhart, & Al-Aidroos, 2017)来存储和表征视觉信息,从而能更有效完成心理旋转任务。

在操作任务中,高WM组的中前额叶活动和后顶区活动显著负相关(参见图6)。由于中前额叶慢波与后顶区慢波的极性相反,负相关说明中前额叶正慢波波幅越大,后顶区负慢波波幅越大。这可能表明,中前额叶调用越多的执行注意监测管理心理旋转过程,同时后顶区调用越多的视觉WM资源表征视觉物体(Tseng, Iu, & Juan, 2018),所以完成操作任务需要两者共同参与。

5 结论高WM组可能通过有效分配加工资源来加强目标的视觉表征,从而促进目标的识别。

Awh, E., Anllo-Vento, L., & Hillyard, S. A. (2000). The role of spatial selective attention in working memory for locations: Evidence from event-related potentials. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 12(5): 840-847. DOI:10.1162/089892900562444 |

Baddeley, A. (1992). Working memory. Science, 255(5044): 556-559. DOI:10.1126/science.1736359 |

Baddeley, A. (2003a). Working memory and language: An overview. Journal of Communication Disorders, 36(3): 189-208. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9924(03)00019-4 |

Baddeley, A. (2003b). Working memory: Looking back and looking forward. Nature Review Neuroscience, 4(10): 829-839. DOI:10.1038/nrn1201 |

Barrett, L. F., Tugade, M. M., & Engle, R. W. (2004). Individual differences in working memory capacity and dual-process theories of the mind. Psychological Bulletin, 130(4): 553-573. DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.553 |

Beste, C., Heil, M., & Konrad, C. (2010). Individual differences in ERPs during mental rotation of characters: Lateralization, and performance level. Brain & Cognition, 72(2): 238-243. DOI:10.1016/j.bandc.2009.09.005 |

Bosch, V., Mecklinger, A., & Friederici, A. D. (2001). Slow cortical potentials during retention of object, spatial, and verbal information. Cognitive Brain Research, 10(3): 219-237. DOI:10.1016/S0926-6410(00)00040-9 |

Boucher, O., Bastien, C. H., Muckle, G., Saint-Amour, D., Jacobson, S. W., & Jacobson, J. L. (2010). Behavioural correlates of the P3b event-related potential in school-age children. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 76(3): 148-157. DOI:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2010.03.005 |

Cohen, J. D., Perlstein, W. M., Braver, T. S., Nystrom, L. E., Noll, D. C., Jonides, J., & Smith, E. E. (1997). Temporal dynamics of brain activation during a working memory task. Nature, 386(6625): 604-608. DOI:10.1038/386604a0 |

Conway, A. R. A., & Engle, R. W. (1994). Working memory and retrieval: A resource-dependent inhibition model. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 123(4): 354-373. DOI:10.1037/0096-3445.123.4.354 |

Conway, A. R. A., Kane, M. J., & Engle, R. W. (2003). Working memory capacity and its relation to general intelligence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(12): 547-552. DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2003.10.005 |

Corballis, P. M. (2003). Visuospatial processing and the right-hemisphere interpreter. Brain and Cognition, 53(2): 171-176. DOI:10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00103-9 |

Delorme, A., & Makeig, S. (2004). EEGLAB: An open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 134(1): 9-21. DOI:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009 |

D’Esposito, M., Detre, J. A., Alsop, D. C., Shin, R. K., Atlas, S., & Grossman, M. (1995). The neural basis of the central executive system of working memory. Nature, 378(6554): 279-281. DOI:10.1038/378279a0 |

D’Esposito, M., Postle, B. R., Ballard, D., & Lease, J. (1999). Maintenance versus manipulation of information held in working memory: An event-related fMRI study. Brain and Cognition, 41(1): 66-86. DOI:10.1006/brcg.1999.1096 |

Emrich, S. M, Lockhart H. A., & Al-Aidroos, N. (2017). Attention mediates the flexible allocation of visual working memory resources. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance, 43(7): 1454-1465. DOI:10.1037/xhp0000398 |

Engle, R. W. (2010). Role of working-memory capacity in cognitive control. Current Anthropology, 51(S1): S17-S26. DOI:10.1086/650572 |

Engle, R. W. (2018). Working memory and executive attention: A revisit. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2): 190-193. DOI:10.1177/1745691617720478 |

Gazzaley, A., Cooney, J. W., Rissman, J., & D’Esposito, M. (2005). Top-down suppression deficit underlies working memory impairment in normal aging. Nature Neuroscience, 8(10): 1298-1300. DOI:10.1038/nn1543 |

Glahn, D. C., Kim, J., Cohen, M. S., Poutanen, V. P., Therman, S., Bava, S.,... Cannon, T. D. (2002). Maintenance and manipulation in spatial working memory: Dissociations in the prefrontal cortex. NeuroImage, 17(1): 201-213. DOI:10.1006/nimg.2002.1161 |

Heil, M. (2002). The functional significance of ERP effects during mental rotation. Psychophysiology, 39(5): 535-545. DOI:10.1111/1469-8986.3950535 |

Heil, M., & Rolke, B. (2002). Toward a chronopsychophysiology of mental rotation. Psychophysiology, 39(4): 414-422. DOI:10.1111/1469-8986.3940414 |

Hsieh, L. T., Ekstrom, A. D., & Ranganath, C. (2011). Neural oscillations associated with item and temporal order maintenance in working memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 31(30): 10803-10810. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0828-11.2011 |

Hyun, J. S., & Luck, S. J. (2007). Visual working memory as the substrate for mental rotation. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14(1): 154-158. |

Jha, A. P. (2002). Tracking the time-course of attentional involvement in spatial working memory: An event-related potential investigation. Cognitive Brain Research, 15(1): 61-69. DOI:10.1016/S0926-6410(02)00216-1 |

Jolles, D. D., Kleibeuker, S. W., Rombouts, S. A. R. B., & Crone, E. A. (2011). Developmental differences in prefrontal activation during working memory maintenance and manipulation for different memory loads. Developmental Science, 14(4): 713-724. DOI:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01016.x |

Jonides, J., Schumacher, E. H., Smith, E. E., Koeppe, R. A., Awh, E., Reuter-Lorenz, P. A.,... Willis, C. R. (1998). The role of parietal cortex in verbal working memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 18(13): 5026-5034. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-05026.1998 |

Jost, K., Bryck, R. L., Vogel, E. K., & Mayr, U. (2011). Are old adults just like low working memory young adults? Filtering efficiency and age differences in visual working memory. Cerebral Cortex, 21(5): 1147-1154. DOI:10.1093/cercor/bhq185 |

Kane, M. J., Bleckley, M. K., Conway, A. R. A., & Engle, R. W. (2001). A controlled-attention view of working-memory capacity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(2): 169-183. DOI:10.1037/0096-3445.130.2.169 |

Kane, M. J., & Engle, R. W. (2000). Working-memory capacity, proactive interference, and divided attention: Limits on long-term memory retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 26(2): 336-358. DOI:10.1037/0278-7393.26.2.336 |

Kane, M. J., & Engle, R. W. (2003). Working-memory capacity and the control of attention: The contributions of goal neglect, response competition, and task set to Stroop interference. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 132(1): 47-70. DOI:10.1037/0096-3445.132.1.47 |

Kok, A. (2001). On the utility of P3 amplitude as a measure of processing capacity. Psychophysiology, 38(3): 557-577. DOI:10.1017/S0048577201990559 |

Liu, D., Guo, C. Y., & Luo, J. (2010). An electrophysiological analysis of maintenance and manipulation in working memory. Neuroscience Letters, 482(2): 123-127. DOI:10.1016/j.neulet.2010.07.015 |

McNab, F., & Klingberg, T. (2008). Prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia control access to working memory. Nature Neuroscience, 11(1): 103-107. DOI:10.1038/nn2024 |

Mecklinger, A., & Pfeifer, E. (1996). Event-related potentials reveal topographical and temporal distinct neuronal activation patterns for spatial and object working memory. Cognitive Brain Research, 4(3): 211-224. DOI:10.1016/S0926-6410(96)00034-1 |

Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1): 49-100. DOI:10.1006/cogp.1999.0734 |

Morgan, H. M., Jackson, M. C., Klein, C., Mohr, H., Shapiro, K. L., & Linden, D. E. J. (2010). Neural signatures of stimulus features in visual working memory—a spatiotemporal approach. Cerebral Cortex, 20(1): 187-197. DOI:10.1093/cercor/bhp094 |

Morgan, H. M., Klein, C., Boehm, S. G., Shapiro, K. L., & Linden, D. E. J. (2008). Working memory load for faces modulates P300, N170, and N250r. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20(6): 989-1002. DOI:10.1162/jocn.2008.20072 |

Osaka, M., Osaka, N., Kondo, H., Morishita, M., Fukuyama, H., Aso, T., & Shibasaki, H. (2003). The neural basis of individual differences in working memory capacity: An fMRI study. NeuroImage, 18(3): 789-797. DOI:10.1016/S1053-8119(02)00032-0 |

Osaka, N., Osaka, M., Kondo, H., Morishita, M., Fukuyama, H., & Shibasaki, H. (2004). The neural basis of executive function in working memory: An fMRI study based on individual differences. NeuroImage, 21(2): 623-631. DOI:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.069 |

Owen, A. M., Herrod, N. J., Menon, D. K., Clark, J. C., Downey, S. P. M. J., Carpenter, T. A.,... Pickard, J. D. (1999). Redefining the functional organization of working memory processes within human lateral prefrontal cortex. European Journal of Neuroscience, 11(2): 567-574. DOI:10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00449.x |

Polich, J. (2007). Updating P300: An integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clinical Neurophysiology, 118(10): 2128-2148. DOI:10.1016/j.clinph.2007.04.019 |

Prime, D. J., & Jolicoeur, P. (2010). Mental rotation requires visual short-term memory: Evidence from human electric cortical activity. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(11): 2437-2446. DOI:10.1162/jocn.2009.21337 |

Rama, P., Sala, J. B., Gillen, J. S., Pekar, J. J., & Courtney, S. M. (2001). Dissociation of the neural systems for working memory maintenance of verbal and nonspatial visual information. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 1(2): 161-171. DOI:10.3758/CABN.1.2.161 |

Redick, T. R., & Engle, R. W. (2006). Working memory capacity and attention network test performance. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20(5): 713-721. DOI:10.1002/acp.1224 |

Rosen, V. M., & Engle, R. W. (1997). The role of working memory capacity in retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 126(3): 211-227. DOI:10.1037/0096-3445.126.3.211 |

Rösler, F., Heil, M., & Röder, B. (1997). Slow negative brain potentials as reflections of specific modular resources of cognition. Biological Psychology, 45(1-3): 109-141. DOI:10.1016/S0301-0511(96)05225-8 |

Serino, A., Ciaramelli, E., Di Santantonio, A., Malagù, S., Servadei, F., & Làdavas, E. (2006). Central executive system impairment in traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 20(1): 23-32. DOI:10.1080/02699050500309627 |

Smith, E. E., & Jonides, J. (1997). Working memory: A view from neuroimaging. Cognitive Psychology, 33(1): 5-42. DOI:10.1006/cogp.1997.0658 |

Smith, E. E., Jonides, J., & Koeppe, R. A. (1996). Dissociating verbal and spatial working memory using PET. Cerebral Cortex, 6(1): 11-20. DOI:10.1093/cercor/6.1.11 |

Tang, D. D., Hu, L., Lei, Y., Li, H., & Chen, A. T. (2015). Frontal and occipital-parietal alpha oscillations distinguish between stimulus conflict and response conflict. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9: 433. DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00433 |

Thakkar, K. N., & Park, S. (2012). Impaired passive maintenance and spared manipulation of internal representations in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38(4): 787-795. DOI:10.1093/schbul/sbq159 |

Tseng, P., Iu, K. C., & Juan, C. H. (2018). The critical role of phase difference in theta oscillation between bilateral parietal cortices for visuospatial working memory. Scientific Reports, 8: 349. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-18449-w |

Unsworth, N., & Engle, R. W. (2007). The nature of individual differences in working memory capacity: Active maintenance in primary memory and controlled search from secondary memory. Psychological Review, 114(1): 104-132. DOI:10.1037/0033-295X.114.1.104 |

Unsworth, N., Schrock, J. C., & Engle, R. W. (2004). Working memory capacity and the antisaccade task: Individual differences in voluntary saccade control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 30(6): 1302-1321. DOI:10.1037/0278-7393.30.6.1302 |

Unsworth, N., & Spillers, G. J. (2010). Working memory capacity: Attention control, secondary memory, or both? A direct test of the dual-component model. Journal of Memory and Language, 62(4): 392-406. DOI:10.1016/j.jml.2010.02.001 |

Vallar, G., Di Betta, A. M., & Silveri, M. C. (1997). The phonological short-term store-rehearsal system: Patterns of impairment and neural correlates. Neuropsychologia, 35(6): 795-812. DOI:10.1016/S0028-3932(96)00127-3 |

Vogel, E. K., & Machizawa, M. G. (2004). Neural activity predicts individual differences in visual working memory capacity. Nature, 428(6984): 748-751. DOI:10.1038/nature02447 |

Vogel, E. K., McCollough, A. W., & Machizawa, M. G. (2005). Neural measures reveal individual differences in controlling access to working memory. Nature, 438(7067): 500-503. DOI:10.1038/nature04171 |

Wijers, A. A., Otten, L. J., Feenstra, S., Mulder, G., & Mulder, L. J. M. (1989). Brain potentials during selective attention, memory search, and mental rotation. Psychophysiology, 26(4): 452-467. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1989.tb01951.x |

Zanto, T. P., & Gazzaley, A. (2009). Neural suppression of irrelevant information underlies optimal working memory performance. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(10): 3059-3066. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4621-08.2009 |

2. Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University, Chongqing 400715;

3. School of Information Resource Management, Renmin University of China, Beijing 100872;

4. Faculty of Foreign Languages, Ningbo University, Ningbo 315211

2020, Vol. 18

2020, Vol. 18