| 强化敏感性人格特质对两性亲密关系的影响:成人依恋类型的中介作用 |

相互依赖理论认为,通过计算伴侣间提供给对方的奖励与惩罚,能有效评估关系现状及预测关系未来发展,即人际奖惩能影响亲密关系质量(Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Rusbult, Arriaga, & Agnew, 2001)。研究者们发现,彼此提供奖励较多(或惩罚较少)的伴侣比那些彼此提供奖励较少(或惩罚较多)的伴侣更能长相厮守(Le, Dove, Agnew, Korn, & Mutso, 2010)。然而,个体对奖惩信息的敏感性不同,则体现了对亲密关系质量评价高低的个体差异性,奖励敏感性高的个体易于接受奖励性信息,从而促进其关系的发展,反之,惩罚敏感性高的个体易于接受惩罚性信息,从而阻碍其关系的发展。Gray(1987)从神经生理学的角度提出了强化敏感性人格理论,认为个体间存在对奖惩信息敏感性不同的人格差异,这种差异源于脑内两个独立的脑系统:行为抑制系统(Behavioral Inhibition System, BIS)和行为趋近系统(Behavioral Approach System, BAS)。其中,BIS系统对惩罚信号或撤销奖励信号做出反应,让个体体验到更多的消极情绪并表现出更多的抑制行为;BAS系统对奖励性信息敏感,表现出更多的趋近行为。研究者们假设BAS系统的神经调节源于脑内奖赏系统的多巴胺通路(Revelle, 2008)。目前,功能性磁共振成像(functional magnetic resonance imaging, fMRI)研究证明了多巴胺通路能调控爱情相关脑区的激活状态,从而提升两性亲密关系中的吸引力,使人们形成稳定的配偶联系(Acevedo, Aron, Fisher, & Brown, 2012; Aron et al., 2008)。强化敏感性理论自提出以来,研究者们进行了大量的实证研究,如成瘾行为、人力资源管理及心理障碍和精神疾病的预测性研究等(Becker et al., 2013; van Hemel-Ruiter, de Jong, Ostafin, & Wiers, 2015; Schreurs, Guenter, Hülsheger, & van Emmerik, 2014)。然而,强化敏感性人格特质影响两性亲密关系的研究则较少被涉及。

爱情作为两性亲密关系中至关重要的构成部分,与关系满意度及稳定性高度相关(Acevedo & Aron, 2009)。爱情三角理论认为,和谐完整的爱情由亲密、激情和承诺三个成分构成(Sternberg, 2006)。本文所讨论的两性亲密关系指两性间的婚恋关系,并以爱情的三成分作为两性亲密关系的评价指标。亲密指感情成分,表现为热情、理解、交流、支持及分享等特点;激情指动机成分,常表现为对性的渴望以及从伴侣处获得满足的强烈情感需求;承诺指认知成分,表现为自己投身于一份感情的决定及维持感情的努力(Miller, 2014; Sternberg, 2006)。目前研究已证明成人依恋类型对亲密关系质量的显著影响(Honari & Saremi, 2015; Ináncsi, Láng, & Bereczkei, 2015)。Feeney和Noller(1990)进一步探讨了成人依恋类型与爱情成分之间的关系,发现安全型依恋个体更易维持稳定的恋爱关系,焦虑型依恋个体表现出对承诺的需求更强烈,而回避依恋个体则更多地表现出对恋人的不信任。Madey和Rodgers(2009)的研究显示,承诺和亲密在安全型依恋和关系满意度之间起到完全中介作用,而激情则起到部分中介作用。此外,自我报告及脑机制研究结果均呈现出不同依恋类型个体对正负性情绪的反应程度有所差异(Chavis & Kisley, 2012; Rognoni, Galati, Costa, & Crini, 2008)。这可能与回避依恋和焦虑依恋个体对正负情绪的刺激敏感度的差异性相关。强化敏感性理论认为,惩罚敏感性高的个体易激活BIS系统而表现出更多的抑制行为和负性情绪。Sheynin, Moustafa, Beck, Servatius和Myers(2015)的研究证明,抑制型个体所表现出的高回避率与惩罚敏感性密切相关。Chavis和Kisley(2012)的研究也显示,回避依恋型个体会更关注消极刺激,从而表现出负性偏向。因此,我们假设惩罚敏感性高个体在亲密关系中所表现出的回避性行为与其回避依恋特质相关,进而影响其亲密关系质量。另一方面,焦虑依恋型个体因采用自动加工情绪的信息加工方式而表现出其控制力低和冲动性高的特点(张晓露, 陈旭, 2014; Donges et al., 2012; Nisenbaum & Lopez, 2015),这与强化敏感理论中对奖励性信息敏感的BAS系统所表现出的低抑制和趋近性特点相一致。此外,焦虑依恋个体不仅对正性刺激敏感,也会有较强的负性情绪反应,这是因为他们在亲密关系中对负性刺激的威胁性归因所致(Nisenbaum & Lopez, 2015)。研究证明,焦虑依恋型个体对消极和积极刺激都会表现出警觉过度(Dykas & Cassidy, 2011; Vrtička, Andersson, Grandjean, Sander, & Vuilleumier, 2008)。郭少聃、何金莲和张利燕(2009)在强化敏感性理论综述中指出,易受惩罚性信息影响的BIS系统激活时,由于抑制了冲突中本来占优势的行为而会伴随产生焦虑情绪。上述研究表明焦虑依恋个体不仅受奖励敏感性影响,与惩罚敏感性也相关。因此,我们假设亲密关系中,奖励敏感性人格所表现出的趋近行为和惩罚敏感性人格所表现的焦虑性情绪都与焦虑依恋特质相关,从而影响其亲密关系质量。

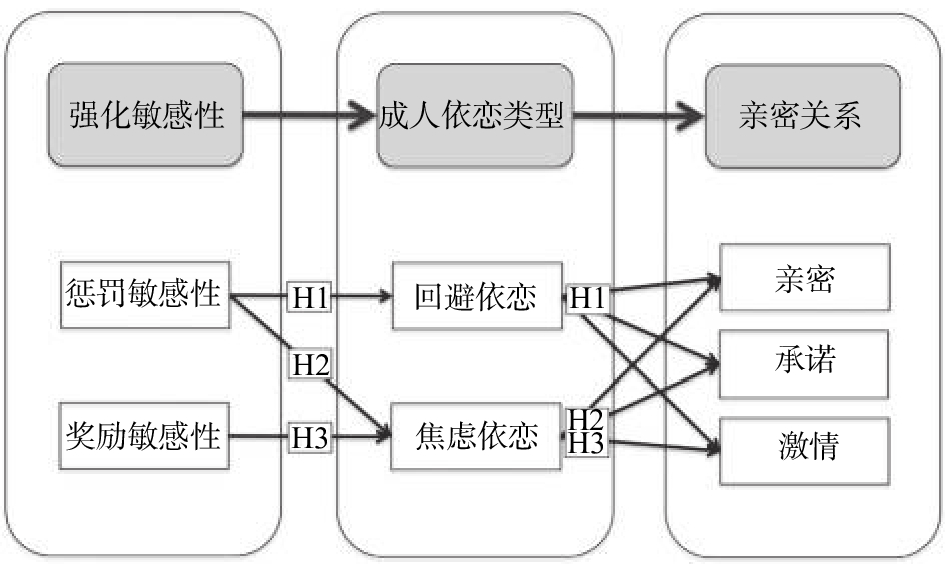

综上所述,本研究拟考察成人依恋在强化敏感性人格特质和两性亲密关系中是否起到中介作用。提出以下假设:H1: 回避依恋在惩罚敏感性和爱情三成分的关系中起到中介作用;H2: 焦虑依恋在惩罚敏感性和爱情三成分的关系中起到中介作用;H3: 焦虑依恋在奖励敏感性和爱情三成分的关系中起到中介作用。如图 1。

|

| 图 1 中介效应假设模型 |

2 研究方法 2.1 被试

选取了812名正处于恋爱中的大学生做问卷调查,收回问卷558份(男263名; 女295名),年龄在18-25岁间(M=19.79, SD=1.57)。恋爱时长在1-36个月间(M=16.68, SD=15.94)。

2.2 研究工具 2.2.1 奖惩敏感性人格量表惩罚和奖励敏感性问卷(The Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire, SPSRQ)是目前常用的强化敏感性自陈问卷(郭少聃等, 2009)。该量表由Torrubia等人于2001年编制,共48个项目,由惩罚敏感性(sensitivity to punishment, SP)和奖励敏感性(sensitivity to reward, SR)两个分量表构成。编制者提供的两个分量表的内部一致性系数分别为0.83和0.76,间隔三个月的再测信度分别为0.81和0.87(Torrubia, Á vila, Moltó, & Caseras, 2001)。本研究中惩罚敏感性分量表和奖励敏感性分量表的内部一致性系数分别为0.84和0.77。

2.2.2 亲密关系的成分量表采用《爱情三角理论量表》(The Triangular Love Scale, TLS)测量亲密关系,该量表共45个项目,由亲密、激情和承诺三个分量表构成,编制者提供的三个分量表的内部一致性系数分别为0.91,0.94和0.94(Sternberg, 1997)。已被证明在反映亲密关系状态上具有良好的信效度(Cassepp-Borges & Pasquali, 2012)。本研究中亲密、激情和承诺分量表的内部一致性系数分别为0.94,0.90和0.94。

2.2.3 成人依恋量表《亲密关系体验量表》(Experiences in Close Relationships Inventory, ECR)广泛应用于测量亲密关系中的成人依恋。该量表共36个项目,由依恋回避和依恋焦虑两个分量表构成,其内部一致性系数接近或超过0.90(Ravitz, Maunder, Hunter, Sthankiya, & Lancee, 2010)。本研究中依恋回避和依恋焦虑分量表的内部一致性系数分别为0.84和0.85。

2.3 程序要求恋人双方分别独立完成以上三种量表,在填写过程中不能进行讨论。承诺提供其个人问卷结果与解释,问卷结果实施严格保密。

2.4 数据处理使用SPSS22.0对研究对象奖惩敏感性、成人依恋和爱情三成分的得分进行描述性统计和相关分析,使用Mplus7.0进行路径分析和中介效应检验。

3 结果与分析 3.1 各变量间的相关分析表 1呈现了本研究人口学变量和主要变量的描述性统计结果和这些变量间的相关分析。结果表明,主要变量中惩罚敏感性与回避依恋(r=0.18, p<0.01)、焦虑依恋(r=0.43, p<0.01)、亲密(r=–0.17, p<0.01)和承诺(r=–0.10, p<0.05)都存在相关,奖励敏感性与焦虑依恋(r=0.27, p<0.01)和激情(r=0.12, p<0.01)都存在相关;回避依恋与亲密(r=–0.61, p<0.01)、激情(r=–0.55, p<0.01)和承诺(r=–0.57, p<0.01)都存在相关,而焦虑依恋与亲密(r=–0.20, p<0.01)和激情(r=0.11, p<0.01)也都存在相关。上述结果为假设检验提供了初步支持(见表 1)。

| 表 1 各变量的平均值、标准差和相关系数 |

3.2 路径分析

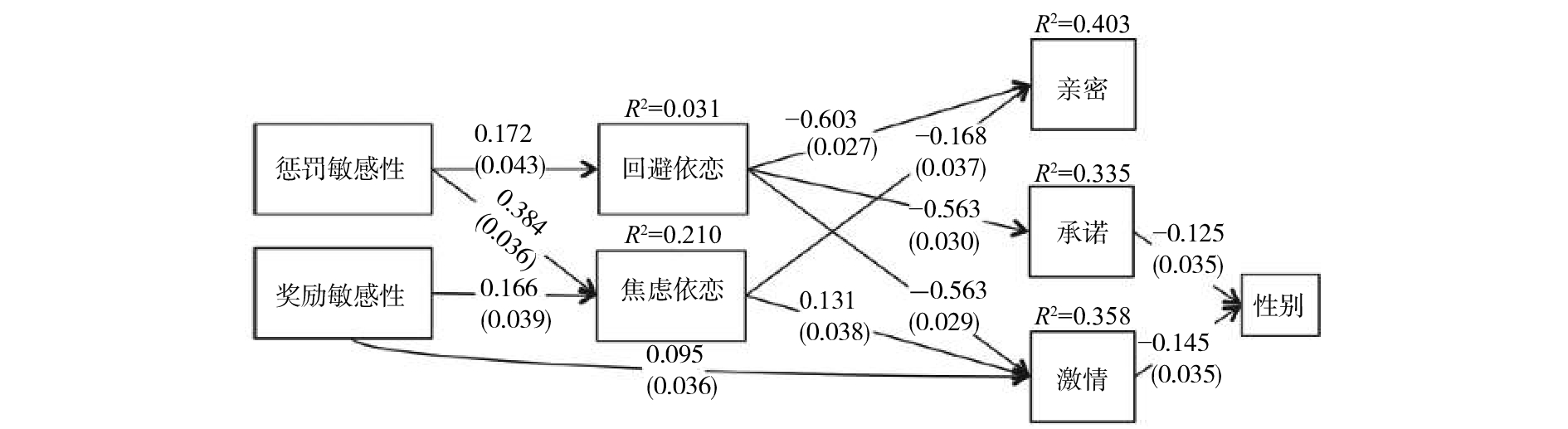

依据相关分析的结果,在最初的路径分析模型中控制了性别、恋爱时长、月均恋爱花销、日均相处时长和日均电子通讯时长等变量,结果发现,除性别外,其他被控制的变量对因变量并无显著预测作用,为简化模型,在后续的分析中只保留了性别控制变量,结果见图 2。

|

| 注:图中路径系数为标准化且显著的路径系数,括号内为标准误。 图 2 成人依恋类型在奖惩敏感性与爱情三元论之间的中介作用 |

图 2检验了成人依恋类型在奖惩敏感性与爱情三元论之间的中介作用,模型拟合度良好(CFI=0.10, TLI=0.96, RMSEA=0.07, 90% CI[0.02,0.13])。由图 2可知,在控制了性别变量后,回避依恋在惩罚敏感性对亲密(β=–0.10, t=–3.96, p<0.001)、激情(β=–0.10, t=–3.90, p<0.001)和承诺(β=–0.10, t=–3.91, p<0.001)的关系中都起到完全中介作用,验证了本研究假设1;焦虑依恋在惩罚敏感性对亲密的关系中起到完全中介作用(β=–0.06, t=–4.15, p<0.001),在惩罚敏感性对激情的关系中也起到了部分中介作用(β=0.05, t=3.24, p=0.001),但在惩罚敏感性对承诺的关系中未发现显著的中介效应(β=0.01, t=0.64, p=0.523),上述结果部分验证了本研究假设2;焦虑依恋在奖励敏感性对亲密的关系中也起到了完全中介作用(β=–0.03, t=–3.11, p=0.002),在奖励敏感性对激情的关系中起到了部分中介作用(β=0.02, t=2.67, p=0.008),但在奖励敏感性对承诺的关系中未发现显著的中介效应(β=0.004, t=0.63, p=0.527),上述结果部分验证了本研究假设3。

4 讨论 4.1 回避依恋是惩罚敏感性(非奖励敏感性)特质影响两性亲密关系的重要中介本研究结果显示,回避依恋类型在惩罚敏感性(而非奖励敏感性)与亲密、激情和承诺之间均起完全中介作用,即惩罚敏感性越高,其回避依恋分值高,则导致亲密关系中对恋人的亲密、激情和承诺感下降。其中,回避依恋影响亲密关系的研究结果支持了以往研究结果。高回避个体通常会怀疑他人,很少和恋人诉说自己的情感和愿望,当恋人请求安慰和支持时其行为更消极,有时甚至会变得恼怒,使得他们对恋人的亲密感降低(Campbell, Simpson, Kashy, & Rholes, 2001; Ein-Dor, Mikulincer, & Shaver, 2011),激情度减少(Mikulincer & Erev, 1991),对伴侣的忠诚度(承诺)降低(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007)。Mikulincer和Shaver(2007)认为回避依恋影响亲密关系的原因是个体采用将积极情绪最小化的回避策略。高回避依恋型个体对社会化积极图片的愉悦度评分更低(Vrtička, Sander, & Vuilleumier, 2012),在积极情绪视频下诱导的脑电唤醒程度也较少(Rognoni et al., 2008),这与回避依恋个体在社会关系中相对缺乏积极行为与经验的感知相关(Cohen & Shaver, 2004)。以上研究结果都说明回避依恋个体对积极社会信息的敏感性较低,从而导致亲密关系质量下降。

然而,本研究结果显示,回避依恋与奖励敏感性无关,只与惩罚敏感性相关。强化敏感性人格理论认为惩罚敏感性高的个体更容易激活BIS系统,此系统是一种冲突解决系统,趋避冲突会引发更高的回避行为,因此,惩罚敏感性高的个体在趋避冲突下会表现出更高的行为抑制并体验到更多的消极情绪,在人际关系的情绪调节中更易产生回避性行为。这与Lassri, Luyten, Cohen和Shahar(2016)的结果相似,该研究发现,回避依恋在儿童情感虐待与亲密关系满意度之间起完全中介作用。Sheynin等(2015)研究也发现,抑制型个体所表现出的高回避率与惩罚敏感性密切相关。此外,Chavis和Kisley(2012)的研究显示,回避依恋型个体会更关注消极刺激,从而表现出负性偏向。因此,惩罚敏感性高个体因激活BIS系统产生行为抑制,所表现出的回避性行为与其回避依恋特质相关,从而影响其亲密关系。另一方面,回避依恋与奖励敏感性无关的研究结果也得到脑功能成像研究的支持,回避依恋型个体在积极社会刺激下,腹侧纹状体和腹侧被盖区呈现较弱反应(Strathearn, Fonagy, Amico, & Montague, 2009; Vrtička et al., 2008),而这两区域正是参与奖赏与成瘾行为的脑区(Schultz, 2000),这表明回避依恋不易激活与脑内奖赏系统重合的BAS系统,所以与奖励敏感性无关。综上所述,惩罚敏感性高个体因其回避依恋特质更易对亲密关系产生消极影响。

4.2 焦虑依恋既是奖励敏感性也是惩罚敏感性特质影响两性亲密度的重要中介本研究结果显示,焦虑依恋类型在奖惩敏感性与亲密度之间都起完全中介作用,即个体无论惩罚敏感性还是奖励敏感性分值越高,其焦虑依恋分值高,则都会导致对恋人的亲密度下降。以往研究表明,焦虑依恋型个体在处理情绪问题时,表现出怀疑伴侣的安全性及自我价值,并且更多使用过度激活策略,倾向夸大事件的威胁性和加强自身的负性情绪状态(Nisenbaum & Lopez, 2015)。焦虑依恋型个体对焦虑的易感性让他们恐惧关系中的排斥与分离,在亲密关系中表现出非常渴望亲密的同时又担心关系恶化的特征(Tomlinson, Carmichael, Reis, & Aron, 2010)。因此,高焦虑依恋个体通常报告出较低的关系满意度和较低的积极情绪(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003)。这与本研究中焦虑依恋可负向预测两性亲密度的结果相一致。

此外,本研究结果表明奖惩敏感性都能对焦虑依恋正向预测,即无论个体属奖励敏感性或惩罚敏感性其程度均与焦虑依恋程度呈正比。Fraley, Niedenthal, Marks, Brumbaugh和Vicary(2006)的研究证明,高焦虑依恋个体比低焦虑依恋个体对积极和消极两类情绪图片的反应都会更快。脑功能成像(fMRI)研究结果也显示积极和消极刺激都能增加焦虑依恋型个体的脑活动(Vrtička et al., 2012)。这些研究表明高焦虑个体可能会在亲密关系中对积极和消极信息均敏感,对情绪刺激表现出较高唤醒程度的同时也表现出较低的控制性。这也许与焦虑依恋个体对情绪信息采用自动化的加工方式有关(张晓露, 陈旭, 2014)。惩罚敏感性与焦虑依恋间的关系可通过强化敏感性理论解释,当BIS系统被激活时会伴随焦虑情绪的产生,从而抑制在冲突中本来占优势的行为(郭少聃等, 2009),说明惩罚敏感性也可反映个体的焦虑特质,一些研究者认为焦虑依恋个体对消极刺激反应性增强是因为他们对亲密关系中消极刺激的威胁性归因所致(Nisenbaum & Lopez, 2015)。正如一些脑功能成像研究结果显示,焦虑依恋个体对消极社会刺激(如愤怒表情或消极语言刺激)呈现出更多激活杏仁核的反应(Lemche et al., 2006; Vrtička et al., 2008)。奖励敏感性和焦虑依恋间的关系也被一些实证研究所证明,如Mitchell等人(2007)的研究发现,奖励敏感性同愤怒敌意表达存在正相关,而Nisenbaum和Lopez(2015)的研究则证明,焦虑依恋与侵略性的愤怒表达呈正相关,我们可以推测奖励敏感性与焦虑依恋特质密切相关。这是因为代表奖励敏感性的BAS系统表现出的低抑制和趋近特点与依恋焦虑性行为相关。综上所述,个体的奖惩敏感性与焦虑依恋特质的相关性与本研究结果相一致。我们认为,焦虑依恋既是奖励敏感性也是惩罚敏感性与两性关系亲密度的重要中介。

4.3 焦虑依恋既是奖励敏感性也是惩罚敏感性影响两性关系激情度的重要中介从生理学视角上看,激情是一种驱力体现,与亲密和承诺是完全不同的体验。研究者们采用fMRI技术来考察个体观看其爱人与陌生人或朋友照片时的大脑活动,结果发现激情所激活的脑区与爱慕之情、承诺所激活的脑区并不相同(Xu et al., 2011)。爱情的经典分析认为,激情源于两个因素,一是情绪唤醒,二是相信对方是引发情绪唤醒的原因(Miller, 2014)。而情绪唤醒对激情(吸引力)的影响并不依赖于其情绪性质,无论是正性情绪刺激还是负性情绪刺激其唤醒度的增加都会增强被试对异性吸引力的评价(White, 1981)。这些研究结果都可以说明,即便是负性情绪唤醒,肾上腺素也会增强人们有关激情的爱情体验。因此,浪漫爱情的一个方面就是高度唤醒的兴奋性,各种能使我们兴奋的事件都可以增加我们对恋人的爱恋(Miller, 2014)。这与本研究结果相一致,个体焦虑依恋在奖惩敏感性与激情度之间起完全中介作用,但与亲密度不同,无论个体的奖励敏感性还是惩罚敏感性,在焦虑依恋的中介作用下都对激情起促进作用,即奖惩敏感性高的个体,焦虑特质越高激情度越高。一项自评情绪图片唤醒度的研究结果显示,个体焦虑依恋分值越高,无论积极还是消极情绪图片的情绪唤醒度评价都会越高(Vrtička et al., 2012)。因此,无论奖励敏感性还是惩罚敏感性,都可以在焦虑特质的中介下引起个体对恋人的激情唤醒。

5 结论成人依恋类型是个体奖惩敏感性特质影响恋人亲密、承诺和激情的重要中介因素。其中,惩罚敏感性高个体通过其回避依恋特质降低亲密、承诺和激情度三方面;奖励敏感性高个体和惩敏感性高个体都可通过其焦虑依恋特质影响亲密和激情度。因此,在两性亲密关系中,了解个体人格特质,针对非安全型成人依恋个体,调节其奖惩认知,减少对互动关系的负性评价,将有助于其亲密关系的发展。

郭少聃, 何金莲, 张利燕. (2009). 强化敏感性人格理论述评. 心理科学进展, 17(2): 390-395. |

张晓露, 陈旭. (2014). 成人依恋风格在信息加工中表现出差异性的神经机制. 心理科学进展, 22(3): 448-457. |

Acevedo, B. P., & Aron, A. (2009). Does a long-term relationship kill romantic love?. Review of General Psychology, 13(1): 59-65. DOI:10.1037/a0014226 |

Acevedo, B. P., Aron, A., Fisher, H. E., & Brown, L. L. (2012). Neural correlates of long-term intense romantic love. Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience, 7(2): 145-159. |

Aron, A., Fisher, H. E., Strong, G., Acevedo, B., Riela, S., & Tsapelas, I. (2008). Falling in love. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel, & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of relationship initiation (pp. 315–336). New York: Psychology Press.

|

Becker, S. P., Fite, P. J., Garner, A. A., Greening, L., Stoppelbein, L., & Luebbe, A. M. (2013). Reward and punishment sensitivity are differentially associated with ADHD and sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms in children. Journal of Research in Personality, 47(6): 719-727. DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2013.07.001 |

Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Kashy, D. A., & Rholes, W. S. (2001). Attachment orientations, dependence, and behavior in a stressful situation: An application of the actor-partner interdependence model. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships, 18(6): 821-843. |

Cassepp-Borges, V., & Pasquali, L. (2012). Sternberg’s triangular love scale national study of psychometric attributes. Paidéia, 22(51): 21-31. DOI:10.1590/S0103-863X2012000100004 |

Chavis, J. M., & Kisley, M. A. (2012). Adult attachment and motivated attention to social images: Attachment-based differences in event-related brain potentials to emotional images. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(1): 55-62. DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2011.12.004 |

Cohen, M., & Shaver, P. (2004). Avoidant attachment and hemispheric lateralisation of the processing of attachment- and emotion-related words. Cognition & Emotion, 18(6): 799-813. |

Donges, U. S., Kugel, H., Stuhrmann, A., Grotegerd, D., Redlich, R., Lichev, V., … Dannlowski, U. (2012). Adult attachment anxiety is associated with enhanced automatic neural response to positive facial expression. Neuroscience, 220: 149-157. DOI:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.06.036 |

Dykas, M. J., & Cassidy, J. (2011). Attachment and the processing of social information across the life span: Theory and evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1): 19-46. DOI:10.1037/a0021367 |

Ein-Dor, T., Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2011). Attachment insecurities and the processing of threat-related information: Studying the schemas involved in insecure people's coping strategies. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 101(1): 78-93. |

Feeney, J. A., & Noller, P. (1990). Attachment style as a predictor of adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 58(2): 281-291. |

Fraley, R. C., Niedenthal, P. M., Marks, M., Brumbaugh, C., & Vicary, A. (2006). Adult attachment and the perception of emotional expressions: Probing the hyperactivating strategies underlying anxious attachment. Journal of Personality, 74(4): 1163-1190. DOI:10.1111/jopy.2006.74.issue-4 |

Gray, J. A. (1987). Perspectives on anxiety and impulsivity: A commentary. Journal of Research in Personality, 21(4): 493-509. DOI:10.1016/0092-6566(87)90036-5 |

Honari, B., & Saremi, A. A. (2015). The study of relationship between attachment styles and obsessive love style. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 165: 152-159. DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.617 |

Ináncsi, T., Láng, A., & Bereczkei, T. (2015). Machiavellianism and adult attachment in general interpersonal relationships and close relationships. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 11(1): 139-154. DOI:10.5964/ejop.v11i1.801 |

Kelley, H. H., & Thibaut, J. W. (1978). Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. New York: Wiley.

|

Lassri, D., Luyten, P., Cohen, G., & Shahar, G. (2016). The effect of childhood emotional maltreatment on romantic relationships in young adulthood: A double mediation model involving self-criticism and attachment. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 8(4): 504-511. |

Le, B., Dove, N. L., Agnew, C. R., Korn, M. S., & Mutso, A. A. (2010). Predicting nonmarital romantic relationship dissolution: A meta-analytic synthesis. Personal Relationships, 17(3): 377-390. DOI:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01285.x |

Lemche, E., Giampietro, V. P., Surguladze, S. A., Amaro, E. J., Andrew, C. M., Williams, S. C. R., … Phillips, M. L. (2006). Human attachment security is mediated by the amygdala: Evidence from combined fMRI and psychophysiological measures. Human Brain Mapping, 27(8): 623-635. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0193 |

Madey, S. F., & Rodgers, L. (2009). The effect of attachment and Sternberg's triangular theory of love on relationship satisfaction. Individual Differences Research, 7(2): 76-84. |

Mikulincer, M., & Erev, I. (1991). Attachment style and the structure of romantic love. British Journal of Social Psychology, 30(4): 273-291. DOI:10.1111/bjso.1991.30.issue-4 |

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2003). The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 35: 53-152. DOI:10.1016/S0065-2601(03)01002-5 |

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: The Guilford Press.

|

Miller, R. (2014). Intimate relationships (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

|

Mitchell, J. T., Kimbrel, N. A., Hundt, N. E., Cobb, A. R., Nelson-Gray, R. O., & Lootens, C. M. (2007). An analysis of reinforcement sensitivity theory and the five-factor model. European Journal of Personality, 21(7): 869-887. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-0984 |

Nisenbaum, M. G., & Lopez, F. G. (2015). Adult attachment orientations and anger expression in romantic relationships: A dyadic analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(1): 63-72. DOI:10.1037/cou0000047 |

Ravitz, P., Maunder, R., Hunter, J., Sthankiya, B., & Lancee, W. (2010). Adult attachment measures: A 25-year review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(4): 419-432. DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.08.006 |

Revelle, W. (2008). The contribution of reinforcement sensitivity theory to personality theory. In P. J. Corr (Ed.), The reinforcement sensitivity theory of personality (pp. 508–527). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

|

Rognoni, E., Galati, D., Costa, T., & Crini, M. (2008). Relationship between adult attachment patterns, emotional experience and EEG frontal asymmetry. Personality & Individual Differences, 44(4): 909-920. |

Rusbult, C. E., Arriaga, X. B., & Agnew, C. R. (2001). Interdependence in close relationships. In G. J. O. Fletcher & M. S. Clark (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Interpersonal processes (pp. 359–387). Oxford: Blackwell.

|

Schreurs, B., Guenter, H., Hülsheger, U., & van Emmerik, E. (2014). The role of punishment and reward sensitivity in the emotional labor process: A within-person perspective. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(1): 108-121. DOI:10.1037/a0035067 |

Schultz, W. (2000). Multiple reward signals in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 1(3): 199-208. DOI:10.1038/35044563 |

Sheynin, J., Moustafa, A. A., Beck, K. D., Servatius, R. J., & Myers, C. E. (2015). Testing the role of reward and punishment sensitivity in avoidance behavior: A computational modeling approach. Behavioural Brain Research, 283: 121-138. DOI:10.1016/j.bbr.2015.01.033 |

Sternberg, R. J. (1997). Construct validation of a triangular love scale. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27(3): 313-335. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-0992 |

Sternberg, R. J. (2006). A duplex theory of love. In R. J. Sternberg & K. Weis (Eds.), The new psychology of love (pp. 184–199). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

|

Strathearn, L., Fonagy, P., Amico, J., & Montague, P. R. (2009). Adult attachment predicts maternal brain and oxytocin response to infant cues. Neuropsychopharmacology, 34(13): 2655-2666. DOI:10.1038/npp.2009.103 |

Tomlinson, J. M., Carmichael, C. L., Reis, H. T., & Aron, A. (2010). Affective forecasting and individual differences: Accuracy for relational events and anxious attachment. Emotion, 10(3): 447-453. DOI:10.1037/a0018701 |

Torrubia, R., Ávila, C., Moltó, J., & Caseras, X. (2001). The sensitivity to punishment and sensitivity to reward questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray's anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Personality & Individual Differences, 31(6): 837-862. |

van Hemel-Ruiter, M. E., de Jong, P. J., Ostafin, B. D., & Wiers, R. W. (2015). Reward sensitivity, attentional bias, and executive control in early adolescent alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors, 40: 84-90. DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.004 |

Vrtička, P., Andersson, F., Grandjean, D., Sander, D., & Vuilleumier, P. (2008). Individual attachment style modulates human amygdala and striatum activation during social appraisal. PLoS One, 3(8): e2868. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0002868 |

Vrtička, P., Sander, D., & Vuilleumier, P. (2012). Influence of adult attachment style on the perception of social and non-social emotional scenes. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships, 29(4): 530-544. |

White, G. L. (1981). Some correlates of romantic jealousy. Journal of Personality, 49(2): 129-145. DOI:10.1111/jopy.1981.49.issue-2 |

Xu, X. M., Aron, A., Brown, L., Cao, G. K., Feng, T. Y., & Weng, X. C. (2011). Reward and motivation systems: A brain mapping study of early-stage intense romantic love in Chinese participants. Human Brain Mapping, 32(2): 249-257. DOI:10.1002/hbm.21017 |

2018, Vol. 16

2018, Vol. 16