昼夜节律系统是动物机体的内部计时器系统,又被称为“分子钟”,是一个以转录为基础的自动调节反馈环,由一组转录调节因子组成,统称为核心钟基因。在哺乳动物中,钟基因主要包括:脑和肌肉芳亭烃受体核转录因子样蛋白-1(brain and muscle arant-like-1, BMAL1)及其结合基因昼夜运动输出周期kaput(CLOCK),这是一种组蛋白乙酰转移酶,驱动包括阻遏物周期(period,PER)和隐花色素(cryptochrome,CRY)蛋白等的表达[1]。动物的生殖活动与其他生理功能一样,都由生物钟控制。内源性的昼夜节律计时器存在于大多数动物中,由位于下丘脑的视交叉神经上核(suprachiasmatic nucleus, SCN)、非SCN大脑结构和体内的大量细胞振荡器组成[2],能够对日常环境的变化迅速做出反应,使体内的生物钟与外界环境趋于一致。以往的研究表明,昼夜节律系统在哺乳动物的生殖过程中起着关键调节作用[3],昼夜节律可以辅助生物体预测环境的变化,并对其行为和生理的变化规律进行时间规划[4-5]。

哺乳动物雌激素属于类固醇激素,主要由卵巢分泌,在动物的多种行为和多个生理过程中均发挥着重要作用[6]。目前,由于雌激素的负反馈引起动物季节性繁殖的说法被广泛接受,并且雌激素受体(estrogen receptor, ER)在介导雌激素信号促使其特异性靶向某些关键细胞方面发挥作用。例如,在绵羊中,雌激素通过与下丘脑视前区(preoptic area, POA)和视交叉后区(retrochiasmatic area, RCh)的雌激素受体α(estrogen receptor alpha, ERα)结合,进而刺激多巴胺能神经元,被激活的多巴胺能神经细胞末梢投射到下丘脑内侧基底部(mediobasal hypothalamus, MBH),然后释放多巴胺作用于GnRH神经元,促进或抑制GnRH分泌,进而调控发情转变[7-10]。研究表明,昼夜节律中时钟分子在维持哺乳动物内分泌系统的平衡中起着重要作用,驱动GnRH分泌和排卵前促黄体素(luteinizing hormone, LH)激增的雌激素敏感神经回路也对昼夜节律定时系统发挥调节作用[11-12],昼夜节律和内分泌系统相互作用以协调激素产生和分泌的时间,以及相应的生殖生理和行为[13]。本文通过对哺乳动物雌激素分泌和昼夜节律、雌激素和昼夜节律之间的分子联系以及二者对雌性哺乳动物繁殖调控机制等方面的研究进展进行综述,以期为深入探究雌性哺乳动物生殖的节律和激素调控机制提供参考。

1 哺乳动物的昼夜节律和雌激素分泌 1.1 哺乳动物发情周期中的雌激素和昼夜节律变化雌性哺乳动物接受雄性动物交配呈现周期性变化,从前一次接受交配到下一次接受交配的这段时期称为一个发情周期。在发情期或交配接受期,以性激素雌激素升高为标志,随后黄体酮升高,维持动物妊娠[14]。对母牛的发情行为和雌二醇血浆浓度测量时发现,在发情活动高峰期后,发情的明显迹象与血浆雌二醇浓度之间有很强的相关性[15]。随着雌二醇浓度的升高,哺乳动物表现出发情的迹象[16]。同时繁殖是一个高度定时的过程,位于SCN的核心振荡器对于调节雌性动物促性腺激素的发情前激增至关重要。发情期SCN的单侧病变会导致发情周期改变,导致动物不排卵,但在发情期或发情前期SCN的病变则阻断排卵而不改变周期[17]。此外,Everett等[18-19]在大鼠的研究中表明,只有在14:00-16:00时之间进行注射戊巴比妥钠,才会在发情期间即所谓的“关键窗口”,阻断排卵。因此,SCN每天在同一时间产生昼夜节律神经信号,这对于正确调节排卵至关重要。该信号与促性腺激素的排卵前释放有关,同时与发情前期发生的其他神经内分泌事件也有关。

1.2 昼夜节律与雌激素分泌互作SCN是大脑中枢生物钟的节律起搏器,在产生昼夜节律中起着关键的作用[20]。1972年,科研人员通过破坏大鼠的神经组织,发现SCN的病变永久消除了白化大鼠饮酒行为和运动活动中的夜间和昼夜节律。首次证实了SCN在昼夜节律的产生中不可或缺[21]。后来通过神经移植试验发现,移植了外源SCN的哺乳动物,昼夜节律系统得到恢复,表明昼夜节律的基本时期由视交叉上核区域的细胞决定[22-23]。SCN是异质的,分为核区和外壳。腹侧核心区域位于视交叉的正上方,能够直接从表达黑视蛋白4(opsin 4, OPN4)的内在光敏视网膜神经节细胞(intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cell, ipRGCs)接收光输入,其内源性振荡决定了整个动物的行为和生理节律[24-25]。

雌激素在正常条件下受到SCN的分子计时调控,具有昼夜节律[26]。Merklinger-Gruchala等[27]研究发现,睡眠变化与雌激素水平显著相关,不规则的作息会影响内源性雌激素的分泌。由于夜班工作或睡眠时间缩短,可能会抑制褪黑激素的产生,而褪黑激素的产生负反馈增加生殖激素水平。另外,卵巢的功能在不同程度上会被失衡的生物体时钟分子影响,而卵巢功能下降会导致卵泡数量减少,进而对FSH的敏感性减弱,FSH水平升高,促进原始卵泡提前进入生长阶段,进而雌激素水平升高[28]。因此,SCN节律性的丧失可能会影响雌激素的释放。雌二醇也可以直接改变SCN的神经元活性,临床试验发现雌激素影响昼夜节律[29],如雌激素可能影响某些大脑区域的神经元兴奋性和突触传递,例如海马和臂旁核[30-31]。Peterfi等[32-33]在研究中发现,体外雌激素处理会增加SCN腹内侧神经元的自发放电频率和兴奋性突触传递。

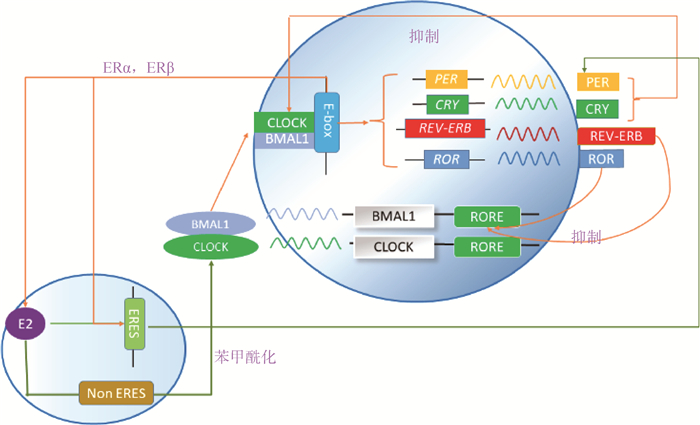

2 昼夜节律和雌激素之间的分子联系 2.1 昼夜节律的分子调控机制哺乳动物中的细胞自主分子生物钟由互锁的转录-翻译反馈回路形成,生物钟蛋白作为生物钟基因节律性转录表达的结果来调节并促使其他相关基因表达,最终通过负反馈作用抑制自身的转录[34-35]。如图 1所示,在主回路中,驱动昼夜节律循环的正元素是转录因子BMAL1和CLOCK的异源二聚体[36],CLOCK-BMAL1激活启动子或增强子区域中含有E/E′-box元件的靶基因(含抑制哺乳动物PER和CRY蛋白家族主要成员的负性元件)的转录,PER-CRY蛋白复合物抑制了CLOCK-BMAL1的活性,从而抑制自身转录。只有当CRY1和CRY2都失活时,昼夜节律性才被取消,而它们的个别丧失分别缩短或延长了昼夜节律周期[37]。在循环的后期,当PER和CRY水平充分下降时,CLOCK-BMAL1介导的转录可以恢复,从而完成循环。除了PER和CRY基因外,CLOCK-BMAL1靶基因还包括孤儿核激素受体REV-ERBα和REV-ERBβ,它们与视黄酸相关孤儿核受体α、β和γ(retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor, RORα/β/γ)共同构成第二环,保证BMAL1的节律性表达(图 1)[38-39]。因此,CLOCK-BMAL1异源二聚体的节律性转录活性也导致数千个基因的节律性表达,这些基因被称为时钟控制基因,是生物钟的输出[13]。

|

图 1 雌激素与昼夜节律基因的相互调节 Fig. 1 Inter-regulation of estrogen and circadian rhythm genes |

促使雌激素特异性靶向某些细胞的是ER[6]。ER是甾体超家族的一员,包括ERα和ERβ[40]。当被雌激素激活时,这些热休克蛋白被释放,使ER二聚化,招募共激活剂/核心加压因子,并与雌激素反应元件(estrogen response element, ERE)序列结合以启动或抑制基因表达(图 1)[41-42]。当核受体ERα或ERβ的二聚体与基因调控区的特定DNA序列结合并组装转录调控复合物时,就发生了基因组雌激素信号转导。当雌激素与膜结合的ERS(包括ERα、ERβ、GPER1、GQ-mer和ER-X)结合时,会出现非基因组的快速信号传导[43]。如图 1所示,ER也可以调控不含ERE基因的转录过程,这主要是通过与靶基因上游转录因子间的相互作用。现阶段研究表明,雌激素通过EREs直接调节昼夜节律基因表达。

2.3 雌激素和昼夜节律之间的相互调节2.3.1 雌激素对节律基因的表达调控 前期研究显示,昼夜节律运动活性和视交叉上核的分子组织方面存在性别差异,暗示雌激素循环可能在其中发挥重要作用[44]。雌激素通过EREs直接调节某些昼夜节律基因的表达,目前已被证实的包括PER2[45-47]和CLOCK[48]基因(图 1)。肖利云[49]在ERα阳性的乳腺癌细胞系MCF-7和T47D中发现,雌激素能诱导细胞内CLOCK蛋白水平的上调,并且验证了ERα能以雌激素依赖的方式结合到CLOCK基因启动子区域上,确定雌激素-ERα信号能正调控CLOCK的转录。Junior等[50]在对乳腺癌上皮核心进行雌激素处理后发现其显著上调了生物钟基因BMAL1的表达,同时雌激素也可作用于ERα,调节另一种核心生物钟基因PER2的表达[47, 51]。雷洛昔芬是一种选择性雌激素受体调节剂,是子宫组织中已知的雌激素拮抗剂,它能减弱雌激素对子宫PER2节律周期的影响。对切除卵巢、敲入PER2::LUC并用雌激素处理的小鼠子宫研究发现,雌激素可缩短PER2::LUC在子宫中的节律性表达,但不改变PER2::LUC在SCN中的表达[47]。可见,雌激素对PER2表达的调节是复杂的,并因组织和物种而异。

2.3.2 昼夜节律系统对雌激素受体基因的表达调控 昼夜节律系统与ER介导的转录途径之间存在密切联系[52]。由图 1可见,CLOCK/BMAL1异源二聚体有节律地与E-box结合[36],并且如果ER在其调节区域中含有E-box,昼夜节律系统就可以直接调节雌激素信号传导。因此,含有E-box的基因通常以每日或昼夜节律表达。研究发现,在维持内部昼夜节律的人类乳腺上皮细胞中,ERα基因的表达也以昼夜节律的方式振荡;但在生物钟破坏的人类乳腺细胞中,ERα表达不具有节律性[50]。ERα的第一内含子中含有一个E-box。因此,ERα可能受到功能失调的CLOCK/BMAL1异源二聚体的潜在影响[53]。ERβ介导和昼夜节律控制的生理过程和疾病已在生殖和非生殖系统中被鉴定出来[54],ERβ mRNA水平在小鼠不同的外周组织中波动,遵循强大的昼夜节律模式,在明暗转变处达到峰值,该转变在正常条件下基本不变,但在时钟不全的BMAL1基因敲除小鼠中这种节律现象就会消失[52]。ERβ表达的昼夜节律控制是通过ERβ启动子区域中的一个保守E-box元件施加的,该元件招募昼夜节律调节因子,并且研究发现小鼠、人、黑猩猩和猕猴的ERβ基因启动子都含有E-box[13]。此外,利用小干扰RNA介导的敲除试验,科研人员发现昼夜节律调节因子的表达水平在细胞水平直接影响雌激素信号传导[52-55]。

2.3.3 雌激素信号和昼夜节律的互作 昼夜节律和雌激素信号之间也存在相互调节,不依赖于EREs或E-box。这些作用涉及昼夜节律和ER蛋白的直接结合以及昼夜节律基因的翻译后修饰。Li等[56]研究发现并证实,雌激素能够增强关键的昼夜节律蛋白CLOCK与ERα的相互作用。苯甲酰化是一种改变蛋白质定位、稳定性或功能的翻译后修饰[57-58],如图 1所示,雌激素能够刺激CLOCK苯甲酰化,进而增强CLOCK的转录活性并且提高ERα的时钟调节转录活性[13]。此外,通过对体外培养的双峰驼卵巢颗粒细胞进行过表达CRY基因,雌二醇含量显著升高;沉默CRY基因则雌二醇含量显著降低,说明CRY影响雌激素的分泌[59]。对雌性大鼠SCN中CRY1和CRY2 mRNA表达的鉴定结果显示,雌激素处理大鼠SCN中CRY2 mRNA的表达显著增加,但雌激素不会影响SCN中的CRY1 mRNA水平。因此,SCN中的CRY1和CRY2 mRNA受雌激素的调控不同[60]。这揭示了主要的昼夜节律蛋白和雌激素依赖性转录因子之间的联系,可能是昼夜节律基因和ER蛋白直接结合的作用所导致的。

3 昼夜节律以及雌激素对哺乳动物的繁殖调控 3.1 雌激素和SCN协同调节哺乳动物繁殖活动3.1.1 SCN与GnRH神经元的信息交流 GnRH神经元是青春期开始和获得生殖功能的多种线索的共同靶点,虽然哺乳动物能周期性分泌GnRH,但其不能直接接受卵巢周期各个阶段GnRH分泌所需的大多数信号[61]。而来自SCN的两个神经元群体存在主时钟,被认为在GnRH/LH激增和排卵中起着至关重要的作用。研究发现,合成血管活性肠肽(vasoactive intestinal peptide, VIP)的SCN神经元以单突触方式投射到GnRH神经元[62],与GnRH神经元进行信号转换,成功产生LH激增和排卵[21]。早期研究发现,VIP可刺激大鼠离体下丘脑释放GnRH[63],后将VIP应用于雌性小鼠的脑片,最后导致GnRH神经元的放电独立于发情周期[64]。同样,SCN合成精氨酸加压素(arginine vasopressin, AVP)的神经元也投射到下丘脑前腹部室旁核(anterior ventral periventricular nucleus, AVPV)区kisspeptin神经元,这些kisspeptin神经元再投射到下丘脑视前区(preoptic area, POA)的GnRH神经元,并使得GnRH激素水平迅速增加[65-67]。研究显示,SCN产生的AVP可能是调节LH释放的昼夜节律信号,但这种信号在CLOCK突变小鼠体中缺失。与野生型小鼠相比,SCN中的AVP在时钟突变小鼠中的表达降低;在脑室内注射(intra-cerebroventricular injection, ICV)AVP给CLOCK突变小鼠,LH会显著增加[68]。在雌性大鼠的发育阶段,SCN通过调节kisspeptin神经元进而作用于GnRH神经元,并且在成年期大鼠中这种作用更为明显[69]。当卵巢切除模型小鼠AVPV区kisspeptin激活时,昼夜节律模式缺失。这些数据表明,SCN能直接或间接地与GnRH神经元的信息交流,进而促进激素分泌。

3.1.2 雌激素和SCN协同调节GnRH分泌、LH峰以及排卵 1978年,Knobil实验室首次证明间歇性的GnRH刺激垂体对LH和FSH的持续分泌至关重要[70],促性腺激素又可以反馈到下丘脑,形成反馈回路调节GnRH的分泌。在大部分哺乳动物的发情周期中,GnRH的释放是脉冲式的[71]。发情期中,随着时间变化产生了间歇性GnRH刺激信号(GnRH在下午释放激增)[72],因此昼夜节律对GnRH的分泌起着关键作用。SCN是大鼠长期维持自发循环排卵所必需的,在雌性大鼠SCN损伤后,黄体酮诱导的促性腺激素激增的幅度与未处理的对照组相比,出现显著变化且经常减弱[73]。SCN损伤消除了大鼠和小鼠LH激增的昼夜节律[74]。在双侧卵巢摘除处理的成熟雌性大鼠中,抑制VIP的表达可以改变LH波的时间,降低LH波的幅度[37]。已有研究表明,促性腺激素的排卵前激增发生在发情前阶段的特定时间[75]。在大鼠和小鼠的4 d周期中进行密集的血液采样显示,LH激增始于发情前的傍晚,在午夜12点左右达到峰值,排卵和交配则发生在几个小时后[73, 76]。以上数据表明,雌激素和SCN在GnRH分泌、LH峰和排卵的时机中起着关键作用。

3.2 雌性哺乳动物HPG轴的昼夜节律及钟基因调控3.2.1 雌性哺乳动物HPG轴的昼夜节律 生殖轴的激素释放模式由下丘脑-垂体-性腺(hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad, HPG)轴的反馈回路调节。HPG轴中激素释放和组织敏感性的时间和节律性由位于下丘脑(视交叉上核,kisspeptin和GnRH神经元)、垂体(促性腺激素)、卵巢(卵泡和颗粒细胞)、睾丸(leydig细胞)以及子宫(子宫内膜和子宫肌层)中的昼夜节律时钟调节。弓状核kisspeptin神经元整合代谢状态信息到HPG轴,是产生脉冲式GnRH释放的关键[77-78]。Kisspeptin神经元在生殖方面的主要作用是刺激GnRH神经元释放GnRH进入下丘脑-门静脉系统,促进垂体促性腺激素FSH和LH释放进入血液[79]。LH和FSH作用于性腺,促进配子发生和性类固醇的产生,性类固醇(睾酮、孕酮和雌激素)负反馈给性腺细胞和下丘脑,从而调节激素释放模式。这些激素释放模式的微调与最佳组织敏感性的结合是通过分子昼夜节律钟获得的,细胞内源性时钟与生殖生理学的各个方面都有联系,包括卵巢类固醇生成、卵泡发育、卵子发育、配子发育、受精着床以及怀孕和分娩[80-81]。

3.2.2 HPG轴上的钟基因调控 昼夜节律计时系统是一个分层系统,具有通过SCN中的时钟基因转录因子产生的内源性节律性。HPG轴上各级的组织都含有昼夜节律,其他器官系统也表达由SCN直接或间接夹带的相同基因产生的细胞节律性[82]。

下丘脑主要是由SCN、kisspeptin和GnRH神经元中的昼夜节律时钟调节。SCN参与下丘脑中的钟基因调控在“3.1.1”中进行了详述。下丘脑AVPV kisspeptin神经元能够表达PER1,并且AVPV离体后依然显示持续的昼夜节律振荡,在维持自我时钟方面发挥重要作用[83]。在细胞特异性BMAL1 KO’s小鼠中,破坏GnRH和kisspeptin神经元,LH激增的时间则被打乱[84]。垂体促性腺激素细胞昼夜节律在调节促性腺激素对GnRH、性类固醇的时间特异敏感性和在FSHβ和LHβ转录中起明显的核心作用[85],但该细胞群中BMAL1的条件性缺失导致发情前期LH水平的轻微增加,以及发情期间FSH的增加,共同导致发情周期的不规则,但不影响生育能力[86]。说明促性腺激素的分子钟在LH和FSH的产生和分泌方面不起主要作用[13, 81]。卵巢能够节律性地表达核心振荡器基因,异位移植卵巢可以存活数月,并继续产生激素和排卵[87]。大鼠卵巢中BMAL1 mRNA在光开始时表达最高,PER2 mRNA在熄灯时最高[88]。但是研究发现,卵巢和SCN之间有8 h的相位差异,SCN的节律先于卵巢[82]。在颗粒细胞培养物中添加LH或FSH时,可以诱导PER1-LUC节律的相移[89]。以上数据表明,LH和FSH信号可能使卵巢时钟与SCN中的中央起搏器同步。

非编码RNAs(non-coding RNA, ncRNA)在时钟生理学中也同样起着独特的作用,它们参与核心时钟基因和时钟输出基因的调节[1]。同样,ncRNA也受到HPG轴中时钟基因的调节。其中发挥主要作用的ncRNA是参与转录后基因沉默的miRNA。核心时钟基因BMAL1、PER、CRY和SIRT1都均已被证明在HPG轴以及其他组织中被miRNA调节[90]。研究人员对miR-219和miR-132在小鼠大脑中的表达进行了分析,发现其表达量在中午达到最高水平,表明miR-219可能参与SCN中的昼夜节律表达[91]。荧光素酶报告基因系统体外验证miRNAs对CLOCK和BMAL1依赖的PER1转录影响试验中,过度表达miR-132后CLOCK和BMAL1依赖的转录没有改变,但PER1荧光素酶活性的表达水平有明显的增强。因此,miR-219和miR-132是CLOCK和BMAL1依赖的PER1翻译的一个重要的正向调节器[92]。此外,研究人员已经表明lncRNA对哺乳动物的昼夜节律生物学具有广泛的影响,在绵羊中,不同光照下差异表达的lncRNA富集在昼夜节律通路上发挥作用[93-94]。在松果体(大鼠的褪黑激素来源)中含有112种lncRNAs的昼夜差异表达[95]。以上研究表明,ncRNA能够调节钟基因的表达,参与昼夜节律系统。

4 小结与展望综上所述,哺乳动物的生物钟系统与雌激素的交流复杂且存在互作关系,在细胞内信号转导、细胞间的系统协调、生殖激素的生成和分泌以及雌性动物的繁殖调控等过程中发挥着重要作用。虽然国内外对生物钟节律和雌激素信号进行了多年的探索,成果也很显著,但由于光周期-信号传导-基因表达-生殖调控是一个复杂的系统,光周期诱导的生物钟节律和雌激素信号的互作研究还存在许多盲点。这主要由于:1)雌性哺乳动物繁殖活动的外界诱因除光周期外,还受气候、海拔、营养等因素的影响,其中海拔、气候对节律系统以及雌激素的调控也有着关键作用;2)繁殖活动除受到生物钟节律和雌激素的互作调控外,还需要多系统协调作用;3)雌性动物繁殖活动相关神经调节通路中多种神经元的功能还未完全阐述清楚,需要进一步探究。由此可见,昼夜节律与雌激素互作机制的研究仍有问题需要解决,其相关研究对揭示哺乳动物光周期适应性(动物发情的环境诱因)以及季节性周期繁殖分子机制具有十分重要的理论和实践意义。

| [1] |

CHINNAPAIYAN S, DUTTA R K, DEVADOSS D, et al. Role of non-coding RNAs in lung circadian clock related diseases[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21(8): 3013. DOI:10.3390/ijms21083013 |

| [2] |

ROSENWASSER A M, TUREK F W. Neurobiology of circadian rhythm regulation[J]. Sleep Med Clin, 2022, 17(2): 141-150. DOI:10.1016/j.jsmc.2022.02.006 |

| [3] |

ZHANG W X, CHEN S Y, LIU C. Regulation of reproduction by the circadian rhythms[J]. Acta Physiol Sin, 2016, 68(6): 799-808. |

| [4] |

BASS J, LAZAR M A. Circadian time signatures of fitness and disease[J]. Science, 2016, 354(6315): 994-999. DOI:10.1126/science.aah4965 |

| [5] |

PHILPOTT J M, TORGRIMSON M R, HAROLD R L, et al. Biochemical mechanisms of period control within the mammalian circadian clock[J]. Semin Cell Dev Biol, 2022, 126: 71-78. DOI:10.1016/j.semcdb.2021.04.012 |

| [6] |

HEWITT S C, KORACH K S. Estrogen receptors: new directions in the new millennium[J]. Endocr Rev, 2018, 39(5): 664-675. DOI:10.1210/er.2018-00087 |

| [7] |

包莹莹. 甘加型藏羊发情周期血浆E2动态变化规律及ERS在HPOA中的表达与分布[D]. 兰州: 甘肃农业大学, 2021. BAO Y Y. The dynamic variation of E2 in plasma and the distribution and expression of ERs in HPOA of Ganjia Tibetan sheep during estrus cycle[D]. Lanzhou: Gansu Agricultural University, 2021. (in Chinese) |

| [8] |

贺小云, 狄冉, 胡文萍, 等. 绵羊季节性繁殖的神经内分泌研究进展[J]. 畜牧兽医学报, 2018, 49(1): 18-25. HE X Y, DI R, HU W P, et al. Research progress on neuroendocrinology controlling sheep seasonal reproduction[J]. Acta Veterinaria et Zootechnica Sinica, 2018, 49(1): 18-25. (in Chinese) |

| [9] |

WEEMS P W, GOODMAN R L, LEHMAN M N. Neural mechanisms controlling seasonal reproduction: principles derived from the sheep model and its comparison with hamsters[J]. Front Neuroendocrinol, 2015, 37: 43-51. DOI:10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.12.002 |

| [10] |

DARDENTE H, SIMONNEAUX V. GnRH and the photoperiodic control of seasonal reproduction: delegating the task to kisspeptin and RFRP-3[J]. J Neuroendocrinol, 2022, 34(5): e13124. |

| [11] |

WILLIAMS III W P, KRIEGSFELD L J. Circadian control of neuroendocrine circuits regulating female reproductive function[J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2012, 3: 60. |

| [12] |

WALTON J C, BUMGARNER J R, NELSON R J. Sex differences in circadian rhythms[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2022, 14(7): a039107. DOI:10.1101/cshperspect.a039107 |

| [13] |

ALVORD V M, KANTRA E J, PENDERGAST J S. Estrogens and the circadian system[J]. Semin Cell Dev Biol, 2022, 126: 56-65. DOI:10.1016/j.semcdb.2021.04.010 |

| [14] |

CLEMENS A M, LENSCHOW C, BEED P, et al. Estrus-cycle regulation of cortical inhibition[J]. Curr Biol, 2019, 29(4): 605-615. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2019.01.045 |

| [15] |

KUMRO F G, SMITH F M, YALLOP M J, et al. Short communication: simultaneous measurements of estrus behavior and plasma concentrations of estradiol during estrus in lactating and nonlactating dairy cows[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2021, 104(2): 2445-2454. DOI:10.3168/jds.2020-19029 |

| [16] |

LASSER J, MATZHOLD C, EGGER-DANNER C, et al. Integrating diverse data sources to predict disease risk in dairy cattle-a machine learning approach[J]. J Anim Sci, 2021, 99(11): skab294. DOI:10.1093/jas/skab294 |

| [17] |

SILVA C C, CORTÉS G D, JAVIER C Y, et al. A neural circadian signal essential for ovulation is generated in the suprachiasmatic nucleus during each stage of the oestrous cycle[J]. Exp Physiol, 2020, 105(2): 258-269. DOI:10.1113/EP087942 |

| [18] |

EVERETT J W, SAWYER C H. A 24-hour periodicity in the "LH-release apparatus" of female rats, disclosed by barbiturate sedation[J]. Endocrinology, 1950, 47(3): 198-218. DOI:10.1210/endo-47-3-198 |

| [19] |

STETSON M H, WATSON-WHITMYRE M, DIPINTO M N, et al. Daily luteinizing hormone release in ovariectomized hamsters: effect of barbiturate blockade[J]. Biol Reprod, 1981, 24(1): 139-144. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod24.1.139 |

| [20] |

HASTINGS M H, MAYWOOD E S, BRANCACCIO M. Generation of circadian rhythms in the suprachiasmatic nucleus[J]. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2018, 19(8): 453-469. DOI:10.1038/s41583-018-0026-z |

| [21] |

STEPHAN F K, ZUCKER I. Circadian rhythms in drinking behavior and locomotor activity of rats are eliminated by hypothalamic lesions[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1972, 69(6): 1583-1586. DOI:10.1073/pnas.69.6.1583 |

| [22] |

RALPH M R, FOSTER R G, DAVIS F C, et al. Transplanted suprachiasmatic nucleus determines circadian period[J]. Science, 1990, 247(4945): 975-978. DOI:10.1126/science.2305266 |

| [23] |

程满, 余爽, 李娟, 等. 视交叉上核在昼夜节律中的作用[J]. 生命科学, 2015, 27(11): 1380-1385. CHENG M, YU S, LI J, et al. The role of the suprachiasmatic nucleus in circadian rhythm generation[J]. Chinese Bulletin of Life Sciences, 2015, 27(11): 1380-1385. DOI:10.13376/j.cbls/2015191 (in Chinese) |

| [24] |

BEGEMANN K, NEUMANN A M, OSTER H. Regulation and function of extra-SCN circadian oscillators in the brain[J]. Acta Physiol (Oxf), 2020, 229(1): e13446. |

| [25] |

ABDALLA O H M H, MASCARENHAS B, CHENG H Y M. Death of a protein: the role of E3 ubiquitin ligases in circadian rhythms of mice and flies[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 23(18): 10569. DOI:10.3390/ijms231810569 |

| [26] |

SCIARRA F, FRANCESCHINI E, CAMPOLO F, et al. Disruption of circadian rhythms: a crucial factor in the etiology of infertility[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21(11): 3943. DOI:10.3390/ijms21113943 |

| [27] |

MERKLINGER-GRUCHALA A, ELLISON P T, LIPSON S F, et al. Low estradiol levels in women of reproductive age having low sleep variation[J]. Eur J Cancer Prev, 2008, 17(5): 467-472. DOI:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75f67 |

| [28] |

王子昕, 宋佳怡, 夏天. 昼夜节律紊乱对女性卵巢功能的影响[J]. 国际生殖健康/计划生育杂志, 2022, 41(4): 317-321. WANG Z X, SONG J Y, XIA T. Effect of circadian rhythm disorder on ovarian function[J]. Journal of International Reproductive Health/Family Planning, 2022, 41(4): 317-321. (in Chinese) |

| [29] |

ASTIZ M, HEYDE I, OSTER H. Mechanisms of communication in the mammalian circadian timing system[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(2): 343. DOI:10.3390/ijms20020343 |

| [30] |

BOS N P A, MIRMIRAN M. Circadian rhythms in spontaneous neuronal discharges of the cultured suprachiasmatic nucleus[J]. Brain Res, 1990, 511(1): 158-162. DOI:10.1016/0006-8993(90)90235-4 |

| [31] |

FATEHI M, ZIDICHOUSKI J A, KOMBIAN S B, et al. 17β-estradiol attenuates excitatory neuro-transmission and enhances the excitability of rat parabrachial neurons in vitro[J]. J Neurosci Res, 2006, 84(3): 666-674. DOI:10.1002/jnr.20959 |

| [32] |

PETERFI Z, CHURCHILL L, HAJDU I, et al. Fos-immunoreactivity in the hypothalamus: dependency on the diurnal rhythm, sleep, gender, and estrogen[J]. Neuroscience, 2004, 124(3): 695-707. DOI:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.10.047 |

| [33] |

FATEHI M, FATEHI-HASSANABAD Z. Effects of 17β-estradiol on neuronal cell excitability and neurotransmission in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of rat[J]. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2008, 33(6): 1354-1364. DOI:10.1038/sj.npp.1301523 |

| [34] |

肖义军, 钟磊发. 哺乳动物昼夜节律的调控及其分子机制[J]. 生物学通报, 2018, 53(5): 2-4. XIAO Y J, ZHONG L F. The regulation of the circadian rhythm of mammals and their molecular mechanisms[J]. Bulletin of Biology, 2018, 53(5): 2-4. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0006-3193.2018.05.002 (in Chinese) |

| [35] |

MIRSKY H P, LIU A C, WELSH D K, et al. A model of the cell-autonomous mammalian circadian clock[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009, 106(27): 11107-11112. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0904837106 |

| [36] |

PATKE A, YOUNG M W, AXELROD S. Molecular mechanisms and physiological importance of circadian rhythms[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2020, 21(2): 67-84. DOI:10.1038/s41580-019-0179-2 |

| [37] |

VAN DER HORST G T J, MUIJTJENS M, KOBAYASHI K, et al. Mammalian Cry1 and Cry2 are essential for maintenance of circadian rhythms[J]. Nature, 1999, 398(6728): 627-630. DOI:10.1038/19323 |

| [38] |

PREITNER N, DAMIOLA F, LUIS-LOPEZ-MOLINA, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBα controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator[J]. Cell, 2002, 110(2): 251-260. DOI:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00825-5 |

| [39] |

SATO T K, PANDA S, MIRAGLIA L J, et al. A functional genomics strategy reveals rora as a component of the mammalian circadian clock[J]. Neuron, 2004, 43(4): 527-537. DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.018 |

| [40] |

钮嘉辉, 王小伟, 尤启冬. 选择性雌激素受体下调剂研究进展[J]. 药学进展, 2019, 43(4): 282-292. NIU J H, WANG X W, YOU Q D, et al. Advances in the development of selective estrogen receptor down-regulators[J]. Progress in Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2019, 43(4): 282-292. (in Chinese) |

| [41] |

O'LONE R, FRITH M C, KARLSSON E K, et al. Genomic targets of nuclear estrogen receptors[J]. Mol Endocrinol, 2004, 18(8): 1859-1875. DOI:10.1210/me.2003-0044 |

| [42] |

HELDRING N, PIKE A, ANDERSSON S, et al. Estrogen receptors: how do they signal and what are their targets[J]. Physiol Rev, 2007, 87(3): 905-931. DOI:10.1152/physrev.00026.2006 |

| [43] |

SANTOLLO J, DANIELS D. Multiple estrogen receptor subtypes influence ingestive behavior in female rodents[J]. Physiol Behav, 2015, 152: 431-437. DOI:10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.05.032 |

| [44] |

HATCHER K M, ROYSTON S E, MAHONEY M M. Modulation of circadian rhythms through estrogen receptor signaling[J]. Eur J Neurosci, 2020, 51(1): 217-228. DOI:10.1111/ejn.14184 |

| [45] |

GERY S, VIRK R K, CHUMAKOV K, et al. The clock gene Per2 links the circadian system to the estrogen receptor[J]. Oncogene, 2007, 26(57): 7916-7920. DOI:10.1038/sj.onc.1210585 |

| [46] |

DAS M, WEBSTER N J G. Obesity, cancer risk, and time-restricted eating[J]. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2022, 41(3): 697-717. DOI:10.1007/s10555-022-10061-3 |

| [47] |

NAKAMURA T J, SELLIX M T, MENAKER M, et al. Estrogen directly modulates circadian rhythms of PER2 expression in the uterus[J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2008, 295(5): E1025-E1031. DOI:10.1152/ajpendo.90392.2008 |

| [48] |

XIAO L Y, CHANG A K, ZANG M X, et al. Induction of the CLOCK gene by E2-ERα signaling promotes the proliferation of breast cancer cells[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(5): e95878. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0095878 |

| [49] |

肖利云. 雌激素-雌激素受体α信号调控CLOCK表达的机理[D]. 大连: 大连理工大学, 2014. XIAO L Y. The mechanism of E2-ERα signal regulating the expression of CLOCK[D]. Dalian: Dalian University of Technology, 2014. (in Chinese) |

| [50] |

JUNIOR R P, DE ALMEIDA CHUFFA L G, SIMÃO V A, et al. Melatonin regulates the daily levels of plasma amino acids, acylcarnitines, biogenic amines, sphingomyelins, and hexoses in a xenograft model of triple negative breast cancer[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 23(16): 9105. DOI:10.3390/ijms23169105 |

| [51] |

潘霄汝, 赵玉磊, 杨玉花, 等. 雌激素对体外培养人毛乳头细胞生物钟基因表达的影响[J]. 临床皮肤科杂志, 2019, 48(9): 539-544. PAN X R, ZHAO Y L, YANG Y H, et al. Effect of estrogen on expression of circadian clock genes in human dermal papilla cells in vitro[J]. Journal of Clinical Dermatology, 2019, 48(9): 539-544. DOI:10.16761/j.cnki.1000-4963.2019.09.005 (in Chinese) |

| [52] |

CAI W, RAMBAUD J, TEBOUL M, et al. Expression levels of estrogen receptor β are modulated by components of the molecular clock[J]. Mol Cell Biol, 2008, 28(2): 784-793. DOI:10.1128/MCB.00233-07 |

| [53] |

HOFFMAN A E, YI C H, ZHENG T Z, et al. CLOCK in breast tumorigenesis: genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptional profiling analyses[J]. Cancer Res, 2010, 70(4): 1459-1468. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3798 |

| [54] |

SRINIVASAN V, SMITS M, SPENCE W, et al. Melatonin in mood disorders[J]. World J Biol Psychiatry, 2006, 7(3): 138-151. DOI:10.1080/15622970600571822 |

| [55] |

WIIK A, GLENMARK B, EKMAN M, et al. Oestrogen receptor β is expressed in adult human skeletal muscle both at the mRNA and protein level[J]. Acta Physiol Scand, 2003, 179(4): 381-387. DOI:10.1046/j.0001-6772.2003.01186.x |

| [56] |

LI S, WANG M, AO X, et al. CLOCK is a substrate of SUMO and sumoylation of CLOCK upregulates the transcriptional activity of estrogen receptor-α[J]. Oncogene, 2013, 32(41): 4883-4891. DOI:10.1038/onc.2012.518 |

| [57] |

HAN Z J, FENG Y H, GU B H, et al. The post-translational modification, SUMOylation, and cancer (review)[J]. Int J Oncol, 2018, 52(4): 1081-1094. |

| [58] |

DAI W, XIE S Q, CHEN C Y, et al. Ras sumoylation in cell signaling and transformation[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2021, 76: 301-309. DOI:10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.03.033 |

| [59] |

赵淑琴. 褪黑素介导的生物钟基因Cry对双峰驼雌二醇分泌的影响[D]. 兰州: 甘肃农业大学, 2020. ZHAO S Q. Effect of melatonin-mediated circadian clock genes Cry on estradiol secretion of Bactrian camel[D]. Lanzhou: Gansu Agricultural University, 2020. (in Chinese) |

| [60] |

NAKAMURA T J, SHINOHARA K, FUNABASHI T, et al. Effect of estrogen on the expression of Cry1 and Cry2 mRNAs in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of female rats[J]. Neurosci Res, 2001, 41(3): 251-255. DOI:10.1016/S0168-0102(01)00285-1 |

| [61] |

张森, 谭建华. 大鼠发情周期中主要生殖激素的变化[J]. 动物医学进展, 2005, 26(12): 1-6. ZHANG S, TAN J H. Change of reproductive hormones at oestrous cycle stage in rat[J]. Progress in Veterinary Medicine, 2005, 26(12): 1-6. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-5038.2005.12.001 (in Chinese) |

| [62] |

KRIEGSFELD L J, SILVER R, GORE A C, et al. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide contacts on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurones increase following puberty in female rats[J]. J Neuroendocrinol, 2002, 14(9): 685-690. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2826.2002.00818.x |

| [63] |

方溪. VIP刺激大鼠离体下丘脑释放GnRH[J]. 国外医学妇产科学分册, 1988(5): 304. FANG X. VIP stimulates GnRH release from isolated hypothalamus of rats[J]. Journal of International Obstetrics and Gynecology, 1988(5): 304. (in Chinese) |

| [64] |

PIET R, DUNCKLEY H, LEE K, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide excites GnRH neurons in male and female mice[J]. Endocrinology, 2016, 157(9): 3621-3630. DOI:10.1210/en.2016-1399 |

| [65] |

WILLIAMS III W P, JARJISIAN S G, MIKKELSEN J D, et al. Circadian control of kisspeptin and a gated GnRH response mediate the preovulatory luteinizing hormone surge[J]. Endocrinology, 2011, 152(2): 595-606. DOI:10.1210/en.2010-0943 |

| [66] |

STEVENSON H, BARTRAM S, CHARALAMBIDES M M, et al. Kisspeptin-neuron control of LH pulsatility and ovulation[J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2022, 13: 951938. DOI:10.3389/fendo.2022.951938 |

| [67] |

GU G B, SIMERLY R B. Projections of the sexually dimorphic anteroventral periventricular nucleus in the female rat[J]. J Comp Neurol, 1997, 384(1): 142-164. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19970721)384:1<142::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-1 |

| [68] |

MILLER B H, OLSON S L, LEVINE J E, et al. Vasopressin regulation of the proestrous luteinizing hormone surge in wild-type and Clock mutant mice[J]. Biol Reprod, 2006, 75(5): 778-784. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod.106.052845 |

| [69] |

骆倩倩. 下丘脑弓状核kisspeptin/kiss1r系统对生殖发育及青春期启动的作用[D]. 滨州: 滨州医学院, 2016. LUO Q Q. The role of kisspeptin/kiss1r system on reproductive development and puberty onset expressed in the arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus[D]. Binzhou: Binzhou Medical University, 2016. (in Chinese) |

| [70] |

BELCHETZ P E, PLANT T M, NAKAI Y, et al. Hypophysial responses to continuous and intermittent delivery of hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone[J]. Science, 1978, 202(4368): 631-633. DOI:10.1126/science.100883 |

| [71] |

PLANT T M. 60 YEARS OF NEUROENDOCRINOLOGY: the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis[J]. J Endocrinol, 2015, 226(2): T41-T54. DOI:10.1530/JOE-15-0113 |

| [72] |

EIDEN L E, HERNÁNDEZ V S, JIANG S Z, et al. Neuropeptides and small-molecule amine transmitters: cooperative signaling in the nervous system[J]. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2022, 79(9): 492. DOI:10.1007/s00018-022-04451-7 |

| [73] |

WIEGAND S J, TERASAWA E, BRIDSON W E, et al. Effects of discrete lesions of preoptic and suprachiasmatic structures in the female rat.Alterations in the feedback regulation of gonadotropin secretion[J]. Neuroendocrinology, 1980, 31(2): 147-157. DOI:10.1159/000123066 |

| [74] |

GRAY G D, SÖDERSTEN P, TALLENTIRE D, et al. Effects of lesions in various structures of the suprachiasmatic-preoptic region on LH regulation and sexual behavior in female rats[J]. Neuroendocrinology, 1978, 25(3): 174-191. DOI:10.1159/000122739 |

| [75] |

ROBERTSON J L, CLIFTON D K, DE LA IGLESIA H O, et al. Circadian regulation of Kiss1 neurons: implications for timing the preovulatory gonadotropin-releasing hormone/luteinizing hormone surge[J]. Endocrinology, 2009, 150(8): 3664-3671. DOI:10.1210/en.2009-0247 |

| [76] |

MURR S M, GESCHWIND I I, BRADFORD G E. Plasma LH and FSH during different oestrous cycle conditions in mice[J]. J Reprod Fertil, 1973, 32(2): 221-230. DOI:10.1530/jrf.0.0320221 |

| [77] |

PADILLA S L, PEREZ J G, BEN-HAMO M, et al. Kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus orchestrate circadian rhythms and metabolism[J]. Curr Biol, 2019, 29(4): 592-604. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2019.01.022 |

| [78] |

MCQUILLAN H J, HAN S Y, CHEONG I, et al. GnRF pulse generator activity across the estrous cycle of female mice[J]. Endocrinology, 2019, 160(6): 1480-1491. DOI:10.1210/en.2019-00193 |

| [79] |

IRWIG M S, FRALEY G S, SMITH J T, et al. Kisspeptin activation of gonadotropin releasing hormone neurons and regulation of KISS-1 mRNA in the male rat[J]. Neuroendocrinology, 2004, 80(4): 264-272. DOI:10.1159/000083140 |

| [80] |

MERENESS A L, MURPHY Z C, SELLIX M T. Developmental programming by androgen affects the circadian timing system in female mice[J]. Biol Reprod, 2015, 92(4): 88. |

| [81] |

SEN A, HOFFMANN H M. Role of core circadian clock genes in hormone release and target tissue sensitivity in the reproductive axis[J]. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2020, 501: 110655. DOI:10.1016/j.mce.2019.110655 |

| [82] |

KENNAWAY D J, BODEN M J, VARCOE T J. Circadian rhythms and fertility[J]. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2012, 349(1): 56-61. DOI:10.1016/j.mce.2011.08.013 |

| [83] |

CHASSARD D, BUR I, POIREL V J, et al. Evidence for a putative circadian kiss-clock in the hypothalamic AVPV in female mice[J]. Endocrinology, 2015, 156(8): 2999-3011. DOI:10.1210/en.2014-1769 |

| [84] |

BITTMAN E L. Circadian function in multiple cell types is necessary for proper timing of the preovulatory LH surge[J]. J Biol Rhythms, 2019, 34(6): 622-633. DOI:10.1177/0748730419873511 |

| [85] |

TSUTSUMI R, WEBSTER N J G. GnRH pulsatility, the pituitary response and reproductive dysfunction[J]. Endocr J, 2009, 56(6): 729-737. DOI:10.1507/endocrj.K09E-185 |

| [86] |

CHU A, ZHU L, BLUM I D, et al. Global but not gonadotrope-specific disruption of Bmal1 abolishes the luteinizing hormone surge without affecting ovulation[J]. Endocrinology, 2013, 154(8): 2924-2935. DOI:10.1210/en.2013-1080 |

| [87] |

CALLEJO J, JÁUREGUI M T, VALLS C, et al. Heterotopic ovarian transplantation without vascular pedicle in syngeneic lewis rats: six-month control of estradiol and follicle-stimulating hormone concentrations after intraperitoneal and subcutaneous implants[J]. Fertil Steril, 1999, 72(3): 513-517. DOI:10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00287-3 |

| [88] |

FAHRENKRUG J, GEORG B, HANNIBAL J, et al. Diurnal rhythmicity of the clock genes Per1 and Per2 in the rat ovary[J]. Endocrinology, 2006, 147(8): 3769-3776. DOI:10.1210/en.2006-0305 |

| [89] |

YOSHIKAWA T, SELLIX M, PEZUK P, et al. Timing of the ovarian circadian clock is regulated by gonadotropins[J]. Endocrinology, 2009, 150(9): 4338-4347. DOI:10.1210/en.2008-1280 |

| [90] |

DUTTA R K, CHINNAPAIYAN S, RASMUSSEN L, et al. A neutralizing aptamer to TGFBR2 and miR-145 antagonism rescue cigarette smoke-and TGF-β-mediated CFTR expression[J]. Mol Ther, 2019, 27(2): 442-455. DOI:10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.11.017 |

| [91] |

SUN E, SHI Y H. MicroRNAs: small molecules with big roles in neurodevelopment and diseases[J]. Exp Neurol, 2015, 268: 46-53. DOI:10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.08.005 |

| [92] |

CHENG H Y, PAPP J W, VARLAMOVA O, et al. Microrna modulation of circadian-clock period and entrainment[J]. Neuron, 2007, 54(5): 813-829. DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.017 |

| [93] |

WANG W, HE X Y, DI R, et al. Transcriptome analysis revealed long non-coding RNAs associated with mRNAs in sheep thyroid gland under different photoperiods[J]. Genes (Basel), 2022, 13(4): 606. DOI:10.3390/genes13040606 |

| [94] |

HE X Y, DI R, GUO X F, et al. Transcriptomic changes of photoperiodic response in the hypothalamus were identified in ovariectomized and estradiol-treated sheep[J]. Front Mol Biosci, 2022, 9: 848144. DOI:10.3389/fmolb.2022.848144 |

| [95] |

COON S L, MUNSON P J, CHERUKURI P F, et al. Circadian changes in long noncoding RNAs in the pineal gland[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012, 109(33): 13319-13324. |

(编辑 郭云雁)