2. 江苏省家禽遗传育种重点实验室, 扬州 225125

2. Key Laboratory for Poultry Genetics and Breeding of Jiangsu Province, Yangzhou 225125, China

弯曲菌(Campylobacter spp.)是胃肠炎的主要病原,其临床表现为腹泻、发热、腹绞痛等临床症状,每年全球有4亿~5亿腹泻病例[1]。国内研究报道显示,腹泻患者中空肠弯曲菌(Campylobacter jejuni, C. jejuni)检测的阳性率为7.1%,已超过志贺菌(5.7%),并有逐渐增加的趋势[2]。除肠炎外,弯曲菌还能引起格林-巴利综合征(Guillain-Barre syndrome, GBS),这是一种以急性进行性神经肌肉麻痹为特征的自身免疫性疾病[3]。

弯曲菌感染通常为自限性,无需抗菌药物治疗,但对于免疫力低下及重症患者,抗菌药物的治疗是必要的。在人医临床上,环丙沙星和红霉素是治疗弯曲菌感染的首选药物[4],其他抗菌药如庆大霉素、四环素和阿奇霉素被列为治疗全身性弯曲菌感染的替代药物[5]。近年来,从人、食品源动物分离的弯曲菌耐药性显著增加[6-7],其主要原因之一是过度使用抗菌药物[8-9]。耐药菌株特别是多重耐药株的出现使得抗菌药物的治疗效果减弱,治疗负担增加,严重威胁到人类的身体健康。弯曲菌已被证明拥有自然转化的遗传结合机制,如果弯曲菌获得了抗菌药物耐药(antimicrobial resistance,AMR)基因,这种特性会使耐药基因在动物和人之间迅速传播从而转移给人类[10]。因此,弯曲菌的耐药性问题已引起人们的广泛关注,成为科学研究的热点。

弯曲菌定植于多种食品源动物肠道,而家禽被认为是弯曲菌的主要宿主[11]。50%~80%的人弯曲菌病是由鸡引起,其致病机制仍不明确,但研究证实毒力基因是主要的致病因素。cadF基因编码外膜蛋白与纤连蛋白结合,介导弯曲菌与宿主肠上皮细胞相互作用[12]。cdtB基因编码细胞溶胀毒素,参与细胞毒素的产生[13]。cgtB和wlaN基因参与β-1,3半乳糖转移酶的生产和生物合成,与格林-巴利综合征中胶质苷类蛋白的表达有关[8]。Cst-Ⅱ基因编码唾液酸转移酶,与格林-巴利综合征相关。crsA基因编码转录调控因子,对黏附肠道细胞、氧化应激具有重要调控作用。clpP基因编码的是一种热应激蛋白[14],在病原微生物中,高温和氧化应激等条件下clpP的表达增强,clpP与clp-ATP酶亚基结合增强细菌酪蛋白水解酶的活性[15]。htrB基因编码一种有助于脂质A合成的酰基转移酶[16-17],这种酶的合成能调节机体环境变化的反应[17]。

为加强江苏省动物源弯曲菌耐药性监测,促进养殖环节科学合理用药,保障动物源性食品和公共卫生安全。本研究对江苏省部分猪鸡养殖场进行弯曲菌的分离,测定分离株对多种抗菌药物的耐药谱,并对其与致病机制相关的8种毒力基因进行检测,为今后临床合理用药、有效防控弯曲菌感染提供依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料1.1.1 样品来源样 品来源于江苏省徐州、盐城、南通、宿迁、淮安、常州等畜禽主产区的15个养鸡场和10个养猪场。鸡源样品采集泄殖腔棉拭子,猪源样品采集动物新鲜粪便,每个养殖场采集样品10份,样品共250份。所有样品采集后于24 h内4 ℃送至实验室处理(详见“1.2.1”)。

1.1.2 主要试剂 CCDA培养基和哥伦比亚培养基购自英国OXOID公司;ExTaq premix和DL 2 000 bp DNA Marker购自宝生物工程(大连)有限公司;脱纤维绵羊血购自青岛海博生物技术有限公司;厌氧罐购自日本MGC公司;混合气(5% O2、10% CO2和85% N2)购自南京特种气体厂有限公司;弯曲菌耐药性药敏检测板购自青岛中创生物科技有限公司。

1.1.3 主要仪器 生化培养箱(HPS-150,太仓市华美生化仪器厂);PCR仪(eppendorf,德国);电泳仪(DYY-12型,北京市六一仪器厂);凝胶成像系统(GBOX,基因有限公司)。

1.1.4 引物 本研究中所用的主要毒力基因引物序列及扩增片段大小见表 1,引物由上海生物工程有限公司合成。

|

|

表 1 弯曲菌毒力基因引物序列及片段大小 Table 1 Primer sequences, amplicon sizes of virulence-associated genes of Campylobacter |

1.2.1 细菌分离与纯化 泄殖腔棉拭子置于含500 μL灭菌PBS(磷酸盐缓冲液,pH 7.2)的Eppendorf管中,充分浸泡20 min,间隔振荡数次,取出棉拭子,取100 μL涂布CCDA平板;新鲜粪便样品取适量用PBS进行稀释,取100 μL涂布CCDA平板,微需氧条件42 ℃培养36 h。挑取CCDA平板上灰白色的可疑菌落,进行PCR鉴定。具体鉴定方法见文献[21]。

1.2.2 药敏试验 采用96孔板琼脂稀释法进行药敏试验,包括对兽医及人医临床常用抗感染的喹诺酮类(萘啶酸和环丙沙星)、大环内酯类(红霉素、阿奇霉素和泰利霉素)、氨基糖苷类(庆大霉素)、四环素类(四环素)、林可胺类(克林霉素)和酰胺醇类(氟苯尼考)共6类9种抗菌药物。以空肠弯曲菌(ATCC33560)作为质控菌株,药敏试验操作步骤按照说明书进行。最小抑菌浓度(minimum inhibitory concentration,MIC)值为24 h后在平板上完全抑制细菌生长的最低药物浓度,根据美国临床实验室标准化协会(Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute,CLSI,2018)和NARMS-2014 (https://www.cdc.gov/narms/antibiotics-tested.html)推荐标准进行耐药判定。

1.2.3 毒力基因检测 常规煮沸法制备菌株DNA模板,PCR扩增毒力基因。其反应体系为25 μL,包括ExTaq premix 12.5 μL,上、下游引物两对(10 μmol·L-1)各1 μL,模板DNA 1 μL,无菌去离子水9.5 μL。PCR循环条件:94 ℃预变性1 min;94 ℃变性30 s,根据不同引物选择相应的退火温度,72 ℃延伸1 min,共30个循环;72 ℃延伸10 min。PCR产物经10 g·L-1琼脂糖凝胶电泳成像,选取PCR扩增产物送至上海生工生物工程有限公司测序,并在GenBank Blast比对验证。

2 结果 2.1 弯曲菌分离鉴定情况采集250份样品,共分离鉴定得到93株弯曲菌,总分离率为37.20%(93/250),其中空肠弯曲菌45株,均为鸡源的,结肠弯曲菌48株:鸡源结肠弯曲菌25株,猪源结肠弯曲菌23株。具体结果见表 2。

|

|

表 2 江苏省畜禽源弯曲菌的分离情况 Table 2 Prevalence of food animal Campylobacter strains isolated from Jiangsu province |

93株弯曲菌的药敏详细结果见表 3。受测弯曲菌对9种抗菌药物均存在不同程度的耐药。空肠弯曲菌耐抗菌药物按严重程度依次为萘啶酸(80.0%)、四环素(71.1%)、环丙沙星(66.7%)、红霉素(62.2%)、克林霉素(62.2%)、阿奇霉素(60.0%)、泰利霉素(42.2%)、庆大霉素(31.1%)和氟苯尼考(6.7%)。与空肠弯曲菌相比,结肠弯曲菌耐药种类略有差异,结肠弯曲菌对红霉素(87.5%)产生较强的耐药性,其次为萘啶酸(79.2%)、阿奇霉素(72.9%)和四环素(66.7%)。而猪源和鸡源的结肠弯曲菌,对部分抗菌药物的耐药率也存在差异,猪源结肠弯曲菌对大环内酯类的红霉素、阿奇霉素和泰利霉素的耐药率显著高于鸡源结肠弯曲菌;而对环丙沙星和萘啶酸的耐药率显著低于鸡源结肠弯曲菌。

|

|

表 3 畜禽源弯曲菌耐药结果 Table 3 Resistance results of food animal Campylobacter strains against 9 antimicrobial agents |

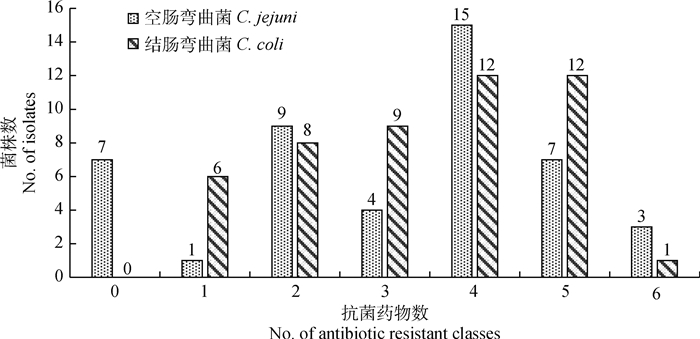

耐药弯曲菌所耐受抗菌药物的数量如图 1所示:在93株弯曲菌中,共有63株弯曲菌对3类或3类以上的抗菌药物耐药,多重耐药率达67.7%。其中空肠弯曲菌29株,结肠弯曲菌34株。其中, 耐4类抗菌药物的菌株数量最多,有27株(29.03%),其次为耐5类抗菌药物的菌株(19株),耐3类抗菌药物(均为13株),耐6类抗菌药物(4株),7株分离株对6类抗菌药物均敏感,且全部为空肠弯曲菌,4株分离株对6类抗菌药物均耐药,其中, 3株为空肠弯曲菌,1株为结肠弯曲菌。

|

图 1 93株弯曲菌分离株的多重耐药情况 Fig. 1 Multidrug resistance of 93 Campylobacter strains |

对93株弯曲菌进行毒力基因的检测,其检测结果如表 4所示。cdtB、cadF基因在空肠和结肠弯曲菌中携带率最高,为100%;其次是htrB毒力基因,在空肠和结肠弯曲菌中均具有较高的携带率,其猪源结肠弯曲菌的携带率为100%,高于鸡源结肠弯曲菌(96.0%);空肠弯曲菌中clpP毒力基因携带率(86.1%)高于结肠弯曲菌(鸡源56.0%和猪源73.9%);csrA毒力基因在空肠弯曲菌携带率为34.8%,而结肠弯曲菌仅1株携带csrA毒力基因;5株空肠弯曲菌检出wlaN毒力基因,而在结肠弯曲菌中未检出;cstⅡ毒力基因在空肠和结肠弯曲菌中携带率均比较低,各1株菌株检出;93株弯曲菌中均未检测到cgtB毒力基因。

|

|

表 4 毒力基因在畜禽源空肠弯曲菌和结肠弯曲菌中的分布 Table 4 Distribution of virulence genes in C. jejuni and C. coli strains isolated from chicken and swine sources |

弯曲菌作为重要的食源性、人畜共患致病菌之一,可引起人的细菌性胃肠炎。弯曲菌宿主来源广泛,能在家禽、猪及野生鸟类的肠道内作为常在菌长期存在,并可以通过食物链广泛传播,引起人类疾病[22]。本研究从江苏省不同地区猪和鸡养殖场收集样本250份,共分离到弯曲菌93株,总分离率37.2%,高于邓凤如[23]报道的宁夏(33.2%)、山东(20.5%)和广东地区(23.3%)的分离率。从分离的猪源弯曲菌的种类来看,23株弯曲菌全部为结肠弯曲菌,与Alter等[24]从15个养猪场分离得到的弯曲菌均为结肠弯曲菌的结果一致。本研究猪源弯曲菌的分离率为23.0%,与国内邓凤如等[23]报道的24.7%接近,远低于法国、英国、美国及加拿大的数据[25],但高于日本的分离率[26]。本研究鸡源弯曲菌分离株中空肠弯曲菌45株,结肠弯曲菌25株,空肠弯曲菌仍然是主导菌种。不同地区鸡源弯曲菌的分离率不同,分离率从2%到100%不等[27]。在国内,不同省份鸡源弯曲菌检出率也存在差异,如邓凤如等[23]研究报道宁夏鸡养殖场分离率为16.5%,而广东为35.5%。本研究江苏省鸡养殖场弯曲菌分离率为46.7%,高于以上报道省份的弯曲菌分离率[23],与张小燕[28]报道的2016年江苏地区鸡养殖场的分离率接近。不同国家不同地区弯曲菌分离率不同,其可能原因是不同地区弯曲菌流行程度不同,也有可能是动物养殖情况、养殖规模、采样的方式、样本数量以及各实验室的分离方法不同造成。

从江苏省分离的93株动物源弯曲菌的药敏试验结果显示,弯曲菌对氟喹诺酮类、大环内酯类和四环素类耐药率较高,这与国内外报道弯曲菌多重耐药情况一致[4, 29]。而大环内酯类和氟喹诺酮类是治疗弯曲菌感染的首选药物,四环素是替代药物,如果耐药菌感染人,可导致人的治疗失败。不同国家或地区空肠弯曲菌对氟喹诺酮类抗菌药物耐药水平不一,如西班牙空肠弯曲菌对氟喹诺酮类抗菌药物耐药率为94.5%,匈牙利为86.1%,法国为56.9%,而瑞士为40.7%[7]。本研究结果表明, 空肠弯曲菌对氟喹诺酮类药物产生较强的耐药性,其萘啶酸和环丙沙星的耐药率分别为80.0%和66.7%,该结果与我国近年来的报道一致,表明我国空肠弯曲菌对氟喹诺酮类药物的耐药比较严重[30-31]。结肠弯曲菌对大环内酯类红霉素和阿奇霉素的耐药率分别为87.5%和72.9%,其中, 猪源结肠弯曲菌的耐药率分别为100.0%和82.6%,高于Lim等[32]所分离猪源结肠弯曲菌的红霉素耐药率(23.9%)和阿奇霉素耐药率(23.9%)。总体而言,结肠弯曲菌对大环内酯类药物的耐药率高于空肠弯曲菌,猪源结肠弯曲菌耐药率高于鸡源结肠弯曲菌,该结果与以往的文献报道[33]一致。鸡源结肠弯曲菌和猪源结肠弯曲菌对氟喹诺酮类和大环内酯类药物的耐药性也存在差异,其原因可能是氟喹诺酮类的恩诺沙星和大环内酯类的泰乐菌素可分别用于鸡和猪细菌疾病预防和治疗,这种选择性压力导致了耐药弯曲菌的产生,同时也导致了耐药表型的差异。

迄今为止,弯曲菌的致病机制尚未清楚,但研究显示,弯曲菌的致病性与细菌的黏附力、侵袭力和产毒能力有关。93株动物源弯曲菌8种毒力基因携带情况分析结果显示,77%菌株携带至少4种毒力基因,5%的菌株携带有6种毒力基因,其中,cadF和cdtB毒力基因携带率为100%。cadF基因在弯曲菌与宿主细胞的黏附和定植过程中起重要作用[34],Ziprin等[35]报道cadF检出阴性的菌株不能定植在鸡的肠道。cdtB基因参与编码细胞致死性膨胀毒素,这两个基因在弯曲菌中广泛存在,与洪捷等[36]、李博等[37]、Nguyen等[38]和Khoshbakht等[39]国内外报道的结果一致。csrA具有调控多种毒力表型的作用,包括动力、氧压力耐受以及细菌定植。本研究空肠弯曲菌csrA的携带率为34.8%,低于González-hein等[40]报道的87.3%,同时该作者认为csrA基因在空肠弯曲菌应激反应中起着重要的调节作用。

有研究表明, cst-Ⅱ[41]、cgtB和wlaN[8]与格林-巴利综合征的发生相关。Louwen等[42]发现cst-Ⅱ能影响空肠弯曲菌对肠道上皮细胞的侵袭能力,本研究中空肠和结肠弯曲菌cst-Ⅱ毒力基因携带率分别为2.1%和4.0%,均低于洪捷[36]报道的江苏地区鸡源空肠弯曲菌53.8%的携带率。cgtB和wlaN基因产物与-1,3半乳糖基转移酶有关。在本研究中,wlaN仅在空肠弯曲菌中检测到,空肠弯曲菌携带率为10.8%,与Datta等[43]报道的4.7%的携带率接近,远低于Khoshbakht等[39]报道的82.2%。Lapierre等[19]、Andrzejewska[44]等研究报道wlaN在空肠弯曲菌中的流行率高于结肠弯曲菌,在本研究中结肠弯曲菌未检出wlaN基因,与以往的研究结果一致。Khoshbakht等[39]报道从肉鸡粪便中分离的弯曲菌,其cgtB基因携带率为22.22%,同时发现空肠弯曲菌的携带率是结肠弯曲菌的两倍,有15株菌同时检出cgtB基因和wlaN基因,其中,10株为空肠弯曲菌,5株为结肠弯曲菌,在本研究中,空肠和结肠弯曲菌中均未检测到cgtB基因。

当弯曲菌高温应激时,可产生包括ATP-依赖的clpP热休克蛋白来保护自身[45-46]。Abu-Madi等[47]研究报道在卡塔尔零售点分离的空肠弯曲菌中,clpP基因携带率为95.9%,作者分析其携带率高的原因可能是clpP基因的表达能帮助弯曲菌在夏季高温条件下存活。而本研究中clpP携带率低于该文献的报道。空肠弯曲菌htrB基因编码脂质A合成的酰基转移酶[16, 48],该酶的合成能调节机体对环境变化的反应,该基因在弯曲菌中相对保守。在本次研究中htrB基因具有高的流行率,表明该基因对宿主体内该细菌生存具有重要的调节作用。

4 结论江苏省畜禽养殖场弯曲菌分离率较高,分离株多重耐药现象严重,毒力基因分布广泛,检出与格林-巴利综合征相关的毒力基因。因此,在畜禽生产上,应谨慎使用抗菌药物,尤其是氟喹诺酮类和大环内酯类药物的使用,同时应加强弯曲菌的耐药及毒力基因监测。

| [1] | RUIZ-PALACIOS G M. The health burden of Campylobacter infection and the impact of antimicrobial resistance:playing chicken[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2007, 44(5): 701–703. |

| [2] | LI Y F, XIE X B, XU X B, et al. Nontyphoidal salmonella infection in children with acute gastroenteritis:prevalence, serotypes, and antimicrobial resistance in Shanghai, China[J]. Foodborne Pathog Dis, 2014, 11(3): 200–206. |

| [3] | FITZGERALD C. Campylobacter[J]. Clin Lab Med, 2015, 35(2): 289–298. |

| [4] | ENGBERG J, AARESTRUP F M, TAYLOR D E, et al. Quinolone and macrolide resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli:resistance mechanisms and trends in human isolates[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2001, 7(1): 24–23. |

| [5] | AARESTRUP F M, ENGBERG J. Antimicrobial resistance of thermophilic Campylobacter[J]. Vet Res, 2001, 32(3-4): 311–321. |

| [6] | GARCÍA-FERNÁNDEZ A, DIONISI A M, ARENA S, et al. Human Campylobacteriosis in Italy:emergence of multi-drug resistance to ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, and erythromycin[J]. Front Microbiol, 2018, 9: 1906. |

| [7] | Eurosurveillance Editorial Team. European union summary report on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food 2012 published[J]. Eurosurveillance, 2014, 19(12): 20748. |

| [8] | RAEISI M, KHOSHBAKHT R, GHAEMI E A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence-associated genes of Campylobacter spp. isolated from raw milk, fish, poultry, and red meat[J]. Microb Drug Resist, 2017, 23(7): 925–933. |

| [9] | KAAKOUSH N O, CASTAÑO-RODRÍGUEZ N, MITCHELL H M, et al. Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2015, 28(3): 687–720. |

| [10] | ACKE E, MCGILL K, QUINN T, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiles and mechanisms of resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolates from pets[J]. Foodborne Pathog Dis, 2009, 6(6): 705–710. |

| [11] | LIN J. Novel approaches for Campylobacter control in poultry[J]. Foodborne Pathog Dis, 2009, 6(7): 755–765. |

| [12] | PATRONE V, CAMPANA R, VALLORANI L, et al. CadF expression in Campylobacter jejuni strains incubated under low-temperature water microcosm conditions which induce the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state[J]. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 2013, 103(5): 979–988. |

| [13] | DEFRAITES R F, SANCHEZ J L, BRANDT C A, et al. An outbreak of Campylobacter enteritis associated with a community water supply on a U. S. military installation[J]. MSMR, 2014, 21(11): 10–15. |

| [14] | FREES D, BRØNDSTED L, INGMER H. Bacterial proteases and virulence[M]//DOUGAN D A. Regulated Proteolysis in Microorganisms. Dordrecht: Springer, 2013: 161-192. |

| [15] | HUGHES R A, CORNBLATH D R. Guillain-Barré syndrome[J]. Lancet, 2005, 366(9497): 1653–1666. |

| [16] | PARKHILL J, WREN B W, MUNGALL K, et al. The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences[J]. Nature, 2000, 403(6770): 665–668. |

| [17] | HAUSDORF L, NEUMANN M, BERGMANN I, et al. Occurrence and genetic diversity of Arcobacter spp. in a spinach-processing plant and evaluation of two Arcobacter-specific quantitative PCR assays[J]. Syst Appl Microbiol, 2013, 36(4): 235–243. |

| [18] | OTIGBU A C, CLARKE A M, FRI J, et al. Antibiotic sensitivity profiling and virulence potential of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from estuarine water in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2018, 15(5): 925. |

| [19] | LAPIERRE L, GATICA M A, RIQUELME V, et al. Characterization of antimicrobial susceptibility and its association with virulence genes related to adherence, invasion, and cytotoxicity in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates from animals, meat, and humans[J]. Microb Drug Resist, 2016, 22(5): 432–444. |

| [20] | LINTON D, GILBERT M, HITCHEN P G, et al. Phase variation of a β-1, 3 galactosyltransferase involved in generation of the ganglioside GM1-like lipo-oligosaccharide of Campylobacter jejuni[J]. Mol Microbiol, 2000, 37(3): 501–514. |

| [21] |

唐梦君, 周倩, 张小燕, 等. 肉鸡屠宰加工生产链中弯曲菌污染状况及耐药性分析[J]. 中国人兽共患病学报, 2018, 34(12): 1131–1136.

TANG M J, ZHOU Q, ZHANG X Y, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance analysis of Campylobacter spp. from broiler slaughter and processing chain[J]. Chinese Journal of Zoonoses, 2018, 34(12): 1131–1136. (in Chinese) |

| [22] | GRIFFITHS P L, PARK R W A. Campylobacters associated with human diarrhoeal disease[J]. J Appl Bacteriol, 1990, 69(3): 281–301. |

| [23] |

邓凤如.耐药基因岛在我国部分地区动物源和人源弯曲菌中的流行和传播[D].北京: 中国农业大学, 2016.

DENG F R. Prevalence and dissemination of the resistance genomic islands in Campylobacter isolates from food animals and patients in partial areas of China[D]. Beijing: China Agricultural University, 2016. (in Chinese) http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10019-1016085129.htm |

| [24] | ALTER T, GAULL F, KASIMIR S, et al. Prevalences and transmission routes of Campylobacter spp. strains within multiple pig farms[J]. Vet Microbiol, 2005, 108(3-4): 251–261. |

| [25] | KEMPF I, KEROUANTON A, BOUGEARD S, et al. Campylobacter coli in organic and conventional pig production in France and Sweden:prevalence and antimicrobial resistance[J]. Front Microbiol, 2017, 8: 955. |

| [26] | MILNES A S, STEWART I, CLIFTON-HADLEY F A, et al. Intestinal carriage of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli O157, Salmonella, thermophilic Campylobacter and Yersinia enterocolitica, in cattle, sheep and pigs at slaughter in Great Britain during 2003[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2008, 136(6): 739–751. |

| [27] | SAHIN O, KASSEM I I, SHEN Z Q, et al. Campylobacter in poultry:ecology and potential interventions[J]. Avian Dis, 2015, 59(2): 185–200. |

| [28] |

张小燕, 周倩, 唐梦君, 等. 江苏地区鸡源弯曲杆菌分离鉴定及耐药性研究[J]. 中国家禽, 2017, 39(18): 23–27.

ZHANG X Y, ZHOU Q, TANG M J, et al. Isolation, identification and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Campylobacter isolates from chickens in Jiangsu Province[J]. China Poultry, 2017, 39(18): 23–27. (in Chinese) |

| [29] | BESTER L A, ESSACK S Y. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter isolates from commercial poultry suppliers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2008, 62(6): 1298–1300. |

| [30] | ZHANG M J, LIU X Y, XU X B, et al. Molecular subtyping and antimicrobial susceptibilities of Campylobacter coli isolates from diarrheal patients and food-producing animals in China[J]. Foodborne Pathog Dis, 2014, 11(8): 610–619. |

| [31] | CHEN X, NAREN G W, WU C M, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter isolates in broilers from China[J]. Vet Microbiol, 2010, 144(1-2): 133–139. |

| [32] | LIM S K, MOON D C, CHAE M H, et al. Macrolide resistance mechanisms and virulence factors in erythromycin-resistant Campylobacter species isolated from chicken and swine feces and carcasses[J]. J Vet Med Sci, 2017, 78(12): 1791–1795. |

| [33] | ZHAO S, YOUNG S R, TONG E, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter isolates from retail meat in the United States between 2002 and 2007[J]. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2010, 76(24): 7949–7956. |

| [34] | MONTEVILLE M R, YOON J E, KONKEL M E. Maximal adherence and invasion of INT 407 cells by Campylobacter jejuni requires the CadF outer-membrane protein and microfilament reorganization[J]. Microbiology, 2003, 149(1): 153–165. |

| [35] | ZIPRIN R L, YOUNG C R, STANKER L H, et al. The absence of cecal colonization of chicks by a mutant of Campylobacter jejuni not expressing bacterial fibronectin-binding protein[J]. Avian Dis, 1999, 43(3): 586–589. |

| [36] |

洪捷, 马恺, 谈忠鸣. 江苏地区不同来源空肠弯曲菌菌株毒力基因分布[J]. 江苏预防医学, 2015, 26(1): 13–15.

HONG J, MA K, TAN Z M. Prevalence of virulence genes in strains of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from different origins in Jiangsu Province[J]. Jiangsu Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2015, 26(1): 13–15. (in Chinese) |

| [37] |

李博, 陈辉, 鞠长燕, 等. 深圳地区不同来源空肠弯曲菌毒力基因分布及分子分型研究[J]. 现代检验医学杂志, 2016, 31(5): 107–109, 112.

LI B, CHEN H, JU C Y, et al. Study on the differences of virulence genes and molecular typing in Campylobacter jejuni isolates from poultry products and diarrhea patients in Shenzhen[J]. Journal of Modern Laboratory Medicine, 2016, 31(5): 107–109, 112. (in Chinese) |

| [38] | NGUYEN T N M, HOTZEL H, EL-ADAWY H, et al. Genotyping and antibiotic resistance of thermophilic Campylobacter isolated from chicken and pig meat in Vietnam[J]. Gut Pathog, 2016, 8: 19. |

| [39] | KHOSHBAKHT R, TABATABAEI M, HOSSEINZADEH S, et al. Distribution of nine virulence-associated genes in Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli isolated from broiler feces in Shiraz, Southern Iran[J]. Foodborne Pathog Dis, 2013, 10(9): 764–770. |

| [40] | GONZÁLEZ-HEIN G, HUARACÁN B, GARCÍA P, et al. Prevalence of virulence genes in strains of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from human, bovine and broiler[J]. Braz J Microbiol, 2013, 44(4): 1223–1229. |

| [41] | PARKER C T, HORN S T, GILBERT M, et al. Comparison of Campylobacter jejuni lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis loci from a variety of sources[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2005, 43(6): 2771–2781. |

| [42] | LOUWEN R, HEIKEMA A, VAN BELKUM A, et al. The sialylated lipooligosaccharide outer core in Campylobacter jejuni is an important determinant for epithelial cell invasion[J]. Infect Immun, 2008, 76(10): 4431–4438. |

| [43] | DATTA S, NIWA H, ITOH K. Prevalence of 11 pathogenic genes of Campylobacter jejuni by PCR in strains isolated from humans, poultry meat and broiler and bovine faeces[J]. J Med Microbiol, 2003, 52(4): 345–348. |

| [44] | ANDRZEJEWSKA M, SZCZEPAŃSKA B, ŚPICA D, et al. Prevalence, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter spp. in raw milk, beef, and pork meat in Northern Poland[J]. Foods, 2019, 8(9): 420. |

| [45] | KONKEL M E, KIM B J, KLENA J D, et al. Characterization of the thermal stress response of Campylobacter jejuni[J]. Infect Immun, 1998, 66(8): 3666–3672. |

| [46] | STINTZI A. Gene expression profile of Campylobacter jejuni in response to growth temperature variation[J]. J Bacteriol, 2003, 185(6): 2009–2016. |

| [47] | ABU-MADI M, BEHNKE J M, SHARMA A, et al. Prevalence of virulence/stress genes in Campylobacter jejuni from chicken meat sold in Qatari retail outlets[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(6): e0156938. |

| [48] | GILBERT M, KARWASKI M F, BERNATCHEZ S, et al. The genetic bases for the variation in the lipo-oligosaccharide of the mucosal pathogen, Campylobacter jejuni:biosynthesis of sialylated ganglioside mimics in the core oligosaccharide[J]. J Biol Chem, 2002, 277(1): 327–337. |