2. 中国农业科学院北京畜牧兽医研究所, 农业部动物遗传育种与繁殖(家禽)重点实验室, 北京 100193

2. Key Laboratory of Animal(Poultry) Genetics, Breeding and Reproduction of Ministry of Agriculture, Institute of Animal Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100193, China

母鸡输卵管的子宫阴道连接部存在一种特殊的管状腺,呈圆形或椭圆形,由单层柱状上皮细胞紧密排列构成,细胞核位于细胞基底部[1-2],由于精子在此贮存而被称为贮精腺、精子腺或阴道腺[3-5]等。贮精腺的主要机能是使精子在输卵管内长期存活,并能长时间保持受精能力[6-7]。贮精腺自被发现以来,众多学者便对其组织形态[8]和分泌物[9]等方面进行了深入研究,发现鸡、鸭、鹅和鹌鹑的子宫阴道连接部贮精腺分布的宽度存在明显差异,其中鸭的最宽,达0. 54 cm,鸡为0.36 cm, 鹌鹑的最窄,仅为0. 20 cm[10]。贮精腺分泌物包含的脂类主要有类固醇激素[11],分泌物还包括一些离子,如钙离子、钠离子和锌离子[12]等,蛋白质主要有抗菌肽β-防御素3[13]和水通道蛋白[14]等。前期研究发现,不同品种以及母鸡个体间的贮精能力存在较大的变异,推测其主要与贮精腺功能有关[15]。母鸡贮精腺功能强弱对于维持持续受精能力至关重要,但关于相关激素及激素受体基因对其调控的研究尚不多。

本试验通过研究贮精能力不同的母鸡在贮精腺形态、相关激素水平及激素受体基因在子宫阴道连接部的表达量差异,以期为揭示贮精腺的贮精机理奠定基础。

1 材料与方法 1.1 试验材料与试验设计试验在中国农业科学院北京畜牧兽医研究所昌平实验基地鸡场进行。选用27周龄健康的白来航母鸡158只和精液品质检测正常的公鸡28只。试验鸡采用单笼饲养,参照中华人民共和国农业行业标准《鸡饲养标准》(NY/T33—2004)饲喂,自由采食和饮水,产蛋期每天光照时长16 h。采用背腹式按摩采精法采集公鸡精液,混合后给母鸡人工输精[16]。每只母鸡输精量控制在40 μL,有效精子数为(3~5) × 107个。连续输精2 d,第3天开始收集种蛋,在蛋壳上标明母鸡个体号和日期,收集前11 d种蛋进行第一批孵化,后10 d收集的种蛋进行第二批孵化。在每次孵化的第9天进行照蛋,记录鸡蛋是否受精。照蛋判定的无精蛋开壳后进一步确认是否为早期死胚,死胚记为受精蛋。根据种蛋收集和孵化结果,统计每只母鸡个体的受精率,挑选产蛋率在85%以上,大小体重相近,无明显病征的高、低受精率极端个体各4只,分别为高、低贮精能力组,其中高贮精能力组的受精率> 80%,低贮精能力组的受精率 < 50%(表 1)。采血,测定血清孕酮、雌激素、睾酮和催乳素浓度,解剖获取其子宫阴道连接部组织,并沿纵向分为两份,一份制作石蜡切片用于观察贮精腺形态,统计黏膜面积、贮精腺数量、贮精腺密度与横截面积,另一份提取RNA,用于检测相应激素受体基因的表达量。

|

|

表 1 高、低贮精能力组母鸡个体产蛋率和受精率 Table 1 Egg production rate and fertility rate of individual in high and low sperm storage ability groups |

1.2.1 贮精能力差异母鸡贮精腺组织切片观察 取高、低贮精能力组母鸡各4只的子宫阴道连接部的HE染色组织切片在显微镜(OlympusCX31,Japan)100倍镜下观察,每个样本随机选取10个黏膜,分别统计贮精腺总数量。用Digimizer软件测定子宫阴道连接部黏膜面积和贮精腺横截面面积,并计算贮精腺密度。石蜡切片制作及染色由北京雪邦科技有限公司完成。

1.2.2 贮精能力差异母鸡相关激素的测定 上述8只试验母鸡翅下静脉采血2~3 mL,室温放置2 h,3 000 r·min-1离心5 min,取上层血清-20 ℃冷冻保存,由北京莱博泰瑞科技发展有限公司利用放射免疫分析法,以放射性核素为标记物定量测定血清中孕酮、雌激素、睾酮和催乳素浓度。

1.2.3 qRT-PCR检测激素受体基因表达 上述8只试验母鸡每只取50~100 mg的冻存子宫阴道连接部组织,采用总RNA提取试剂盒(TianGen Biotech公司,北京)提取并纯化RNA。用反转录试剂盒Prime Script RT Reagent Kit(TaKaRa公司,大连)反转录合成cDNA,反转录前先去除基因组DNA,冰上配制反应混合液,反应体系为:DNA Eraser buffer 2.0 μL,g DNA Eraser 1.0 μL,Total RNA总量为1 μg,体积根据RNA浓度而定,加入RNase Free H2O至总体系为10 μL。PCR反应条件:42 ℃ 2 min,4 ℃循环保存,然后将反转录产物在-20 ℃保存待用。

根据NCBI中鸡的雌激素受体α基因(ERα)、雌激素受体β基因(ERβ)、孕酮受体基因(PGR)、睾酮受体基因(AR)、催乳素受体基因(PRLR)以及内参基因β-actin的基因序列,采用NCBI网站设计qPCR引物(表 2),由北京六合华大基因科技股份有限公司合成。

|

|

表 2 荧光定量PCR的引物信息 Table 2 Primer pairs information for qPCR |

以获得的高、低贮精能力个体贮精腺组织的cDNA为模板,采用ABI7500型荧光定量PCR仪对ERα、ERβ、PGR、AR、PRLR及内参基因β-actin的表达量进行分析。qPCR反应体系为10 μL:SYBR Premix Ex Taq II 5 μL,上、下游引物(10 μmol·L-1)各0.5 μL,模板cDNA 1.5 μL,ROX Reference Dye 0.2 μL,ddH2O 2.3 μL。反应条件:95 ℃预变性3 min;95 ℃变性3 s,60 ℃退火34 s,40个循环;熔解曲线收集信号为95 ℃ 15 s,60 ℃ 1 min,95 ℃ 15 s。扩增结束后进行熔解曲线分析,每个样品重复3次,取平均值。

1.3 数据统计与分析原始数据经过Excel初步整理后,采用SAS8.0软件对数据进行单因素方差分析,比较贮精能力高、低组母鸡子宫阴道连接部的黏膜面积、贮精腺数量、密度和横截面面积、相关激素浓度和相应激素受体基因的表达量差异,P < 0.05表示差异显著。

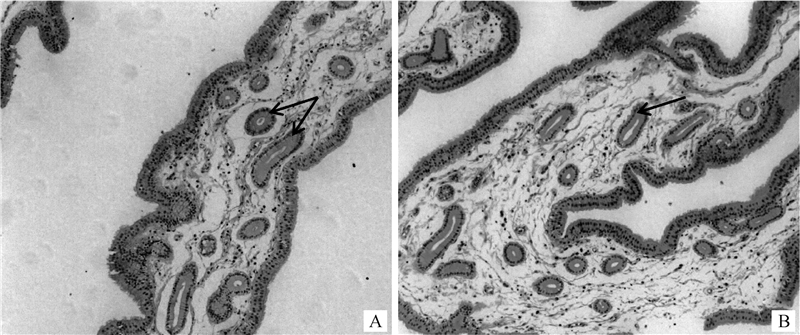

2 结果 2.1 贮精能力差异母鸡的贮精腺组织切片观察如图 1所示,子宫阴道连接处黏膜固有层中圆形和椭圆形的腺体即为贮精腺,为典型的单层柱状上皮细胞围绕而成的单管状腺,大部分单个存在,周围由疏松结缔组织包围。与高贮精能力个体(图 1A)相比,低贮精能力个体(图 1B)的贮精腺无明显病变情况。由表 3可知,高、低贮精能力组的子宫阴道连接部黏膜面积、贮精腺数量和密度均差异不显著(P>0.05),但高贮精能力组母鸡的贮精腺横截面面积显著高于低贮精能力组(P < 0.05)。

|

箭头所指为贮精腺 The arrows point to the sperm storage tubules 图 1 高贮精能力个体(A)和低贮精能力个体(B)子宫阴道连接部贮精腺HE染色切片(100×) Fig. 1 HE staining sections of uterine-vaginal junction of hens in high (A) and low (B) sperm storage ability groups (100×) |

|

|

表 3 高、低贮精能力组子宫阴道连接部和贮精腺组织形态特征 Table 3 Morphology characteristics of uterine-vaginal junction and sperm storage tubules of hens in high and low sperm storage ability groups |

由表 4可知,高、低贮精能力组母鸡的血清孕酮激素浓度差异显著(P < 0.05),而雌激素、睾酮和催乳素浓度均差异不显著(P>0.05)。

|

|

表 4 高、低贮精能力组母鸡主要性激素浓度 Table 4 Serum hormone concentrations of hens in high and low sperm storage ability groups |

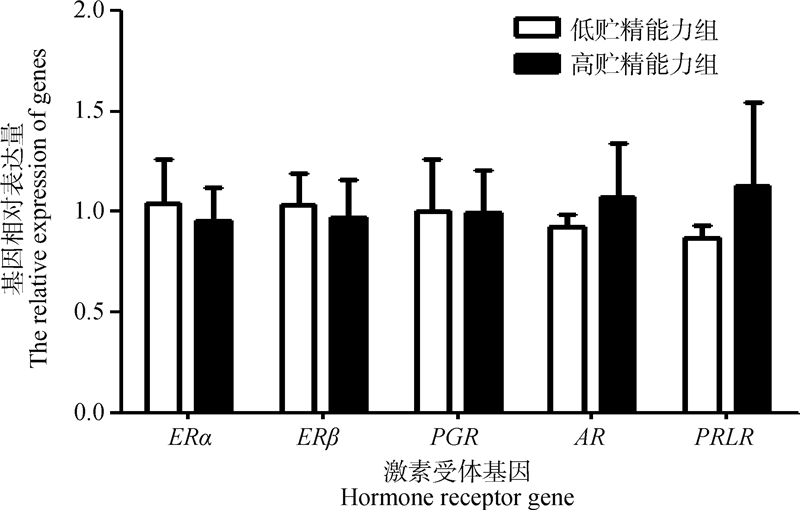

由图 2可知,在子宫阴道连接部均能检测到雌激素受体基因(ERα、ERβ)、孕酮受体基因(PGR)、睾酮受体基因(AR)和催乳素受体基因(PRLR)表达,高贮精能力组相比低贮精能力组,睾酮受体基因和催乳素受体基因表达上调,雌激素α、β受体基因和孕酮受体基因下调,但未达显著水平(P>0.05)。

|

ERα、ERβ、PGR、AR 和 PRLR 分别表示雌激素受体α基因、雌激素受体β基因、孕酮受体基因、睾酮受体基因和催乳素受体基因 ERα, ERβ, PGR, AR, and PRLR stand for estrogen receptor alpha gene, estrogen receptor beta gene, progesterone receptor gene, testosterone receptor gene and prolactin receptor gene, respectively 图 2 高、低贮精能力组激素受体基因相对表达量 Fig. 2 Relative expression of hormone receptor genes in high and low sperm storage ability groups |

在家禽生产和育种中,受精率通常用来衡量公鸡的繁殖力。母鸡的贮精能力对受精率和输精频率的影响往往被忽略[17]。前人研究表明,饲喂方式[18]、肠道微生物[19]、子宫阴道连接部蛋白和脂肪酸[20-21]、免疫抑制能力和酸碱度[22]以及相关基因的表达差异[23-24]均会对母禽贮精能力产生影响。本研究针对同一品种贮精能力差异的母鸡进行了贮精腺数量、横截面面积大小、相关性激素浓度以及对应激素受体基因表达量的测定,为揭示母鸡贮精能力的影响因素和调控机制奠定基础,有助于从根本上提升母鸡受精能力,并进一步提高制种效率和经济效益。

母鸡在自然交配或者人工输精后立即检查输卵管,发现输卵管腔中并没有精子,但随着时间的推移,输卵管子宫阴道连接部的精子数量逐渐增加,精子在24 h内即分布于输卵管子宫阴道连接部及伞部,在产蛋或排卵作用下,精子可以重新进入输卵管腔上行完成受精[25]。有研究表明,贮精能力与子宫阴道连接部的贮精腺数量有关[26],Bakst等[27]发现,不同禽类的贮精腺数量有显著差异,如火鸡和肉种鸡分别有30 566和4 893个贮精腺,其对应的持续受精时间至少为45 d[1]和23 d[28]。在同一品种母鸡产蛋休止期的子宫阴道连接部宽度变窄,且腺体数量仅为产蛋期的一半左右[10],Pierson等[26]也发现,不同贮精能力的母鸡贮精腺数量不同,贮精能力高的母鸡贮精腺数量高于贮精能力低的母鸡。因此可以推测,贮精腺的数量与母禽的生理和机能状态也有一定关系,且产蛋期持续受精时间在很大程度上可能与子宫阴道连接部的贮精腺数量有关。在本试验中,虽然高、低贮精能力组贮精腺数量差异不显著,但高贮精能力组有高于低贮精能力组的趋势,而且高贮精能力组贮精腺的横截面面积显著高于低贮精能力组,可贮存精子的空间能力强,这可能是贮精能力高的重要原因之一。

输卵管生长分化和分泌功能主要受性激素的调节[29],贮精腺的发育和功能可能也受到性激素的调控[30]。激素发挥生理作用需要与靶细胞表面的相应激素受体结合,由激素受体介导将信号传入细胞内从而产生一系列生理效应。贮精腺是性激素的靶组织,其性激素受体的存在是必不可少的。本试验在母鸡子宫阴道连接部均检测到孕酮、雌激素、睾酮和催乳素受体基因的表达,说明激素可能影响该组织功能的发挥。前人研究也表明,贮精腺内精子的释放通过膜上孕酮受体调节信号转导而实现[31],本研究中,高贮精能力个体的血清孕酮浓度显著高于低贮精能力母鸡个体,进一步证实孕酮激素可能对诱导贮精腺中精子的激活起重要作用,从而影响母鸡贮精能力和持续受精时间。还有研究发现,雌激素受体和孕酮受体与贮精腺的形成有关[11],雌激素处理可以促进子宫阴道连接部贮精腺生成以及孕酮受体的表达[32]。Das等[33]发现,重复人工授精使子宫阴道连接部雌激素受体α表达量的下降可能导致受精能力下降。激素与激素受体要发挥作用往往还需要一些辅助因子, 这些辅助因子主要包括类固醇受体辅助激活因子等[34]。本研究也检测到雌激素、睾酮和催乳素受体在贮精腺的表达,除孕酮外未发现相应激素和激素受体基因表达在组间存在显著差异,激素及激素受体基因作用间的辅助因子是否间接影响贮精能力有待于进一步研究。

4 结论本研究结果表明,母鸡的贮精能力与贮精腺腺体横截面面积有关;此外,孕酮激素可能对诱导贮精腺中精子的激活起重要作用,从而影响母鸡持续受精能力。

| [1] | LONG E L, SONSTEGARD T S, LONG J A, et al. Serial analysis of gene expression in turkey sperm storage tubules in the presence and absence of resident sperm[J]. Biol Reprod, 2003, 69(2): 469–474. |

| [2] | HOLT W V, FAZELI A. Sperm storage in the female reproductive tract[J]. Annu Rev Anim Biosci, 2016, 4: 291–310. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-animal-021815-111350 |

| [3] | FROMAN D. Deduction of a model for sperm storage in the oviduct of the domestic fowl (Gallus domes-ticus)[J]. Biol Reprod, 2003, 69(1): 248–253. |

| [4] | FREEMAN S L, ENGLAND G C W. Storage and release of spermatozoa from the pre-uterine tube reservoir[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(2): e57006. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057006 |

| [5] | BELL D J, FREEMAN B M. Nonmammals.(Book Reviews:Physiology and biochemistry of the domestic fowl)[J]. Aust Vet J, 2010, 52(2): 63. |

| [6] | ADETULA A A, GU L T, NWAFOR C C, et al. Transcriptome sequencing reveals key potential long non-coding RNAs related to duration of fertility trait in the uterovaginal junction of egg-laying hens[J]. Sci Rep, 2018, 8: 13185. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-31301-z |

| [7] | GASPARINI C, DAYMOND E, EVANS J P. Extreme fertilization bias towards freshly inseminated sperm in a species exhibiting prolonged female sperm storage[J]. Roy Soc Open Sci, 2018, 5(3): 172195. DOI: 10.1098/rsos.172195 |

| [8] | MOURA T, SERRA-PEREIRA B, GORDO L S, et al. Sperm storage in males and females of the deep-water shark Portuguese dogfish with notes on oviducal gland microscopic organization[J]. J Zool, 2011, 283(3): 210–219. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00775.x |

| [9] | BAKST M R. Physiology and endocrinology symposium:role of the oviduct in maintaining sustained fertility in hens[J]. J Anim Sci, 2011, 89(5): 1323–1329. DOI: 10.2527/jas.2010-3663 |

| [10] |

崔成都, 鲁京兰, 金清诛, 等. 禽类输卵管精子腺组织学与组织化学研究[J]. 动物医学进展, 2010, 31(10): 58–62.

CUI C D, LU J L, JIN Q Z, et al. Histology and histochemistry studies on sperm-host glands in poultry oviduct[J]. Progress In Veterinary Medicine, 2010, 31(10): 58–62. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-5038.2010.10.014 (in Chinese) |

| [11] | YOSHIMURA Y, KOIKE K, OKAMOTO T. Immunolocalization of progesterone and estrogen receptors in the sperm storage tubules of laying and diethylstilbestrol-injected immature hens[J]. Poult Sci, 2000, 79(1): 94–98. |

| [12] | HOLM L, EKWALL H, WISHART G J, et al. Localization of calcium and zinc in the sperm storage tubules of chicken, quail and turkey using X-ray microanalysis[J]. J Reprod Fertil, 2000, 118(2): 331–336. DOI: 10.1530/jrf.0.1180331 |

| [13] | SHIMIZU M, WATANABE Y, ISOBE N, et al. Expression of avian β-Defensin 3, an antimicrobial peptide, by sperm in the male reproductive organs and oviduct in chickens:an immunohistochemical study[J]. Poult Sci, 2008, 87(12): 2653–2659. DOI: 10.3382/ps.2008-00210 |

| [14] | ZANIBONI L, BAKST M R. Localization of aqua-porins in the sperm storage tubules in the turkey oviduct[J]. Poult Sci, 2004, 83(7): 1209–1212. DOI: 10.1093/ps/83.7.1209 |

| [15] |

范静, 马腾壑, 王攀林, 等. 母鸡持续受精能力的群体变异分析[J]. 畜牧兽医学报, 2019, 50(10): 2013–2021.

FAN J, MA T H, WANG P L, et al. Population variation analysis of sustaining fertilization ability of hens[J]. Acta Veterinaria et Zootechnica Sinica, 2019, 50(10): 2013–2021. DOI: 10.11843/j.issn.0366-6964.2019.10.007 (in Chinese) |

| [16] | TABATABAEI S. The effect of spermatozoa number on fertility rate of chicken in artificial insemination programs[J]. J Anim Vet Adv, 2010, 9(12): 1717–1719. DOI: 10.3923/javaa.2010.1717.1719 |

| [17] | WOLC A, WHITE I M, OLORI V E, et al. Inheri-tance of fertility in broiler chickens[J]. Genet Sel Evol, 2009, 41(1): 47. |

| [18] | GOERZEN P R, JULSRUD W L, ROBINSON F E, et al. Duration of fertility in Ad libitum and feed-restricted caged broiler breeders[J]. Poult Sci, 1996, 75(8): 962–965. DOI: 10.3382/ps.0750962 |

| [19] | ELOKIL A A, ABOUELEZZ K, ADETULA A A, et al. Investigation of the impact of gut microbiotas on fertility of stored sperm by types of hens[J]. Poult Sci, 2020, 99(2): 1174–1184. |

| [20] | HUANG A, ISOBE N, OBITSU T, et al. Expression of lipases and lipid receptors in sperm storage tubules and possible role of fatty acids in sperm survival in the hen oviduct[J]. Theriogenology, 2016, 85(7): 1334–1342. DOI: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2015.12.020 |

| [21] | TALBOT N C, KRASNEC K V, GARRETT W M, et al. Finite cell lines of turkey sperm storage tubule cells:ultrastructure and protein analysis[J]. Poult Sci, 2018, 97(10): 3698–3708. DOI: 10.3382/ps/pey208 |

| [22] | ATIKUZZAMAN M, ALVAREZ-RODRIGUEZ M, VICENTE-CARRILLO A, et al. Conserved gene expression in sperm reservoirs between birds and mammals in response to mating[J]. BMC Genomics, 2017, 18(1): 98. DOI: 10.1186/s12864-017-3488-x |

| [23] | YANG L B, ZHENG X T, MO C H, et al. Transcriptome analysis and identification of genes associated with chicken sperm storage duration[J]. Poult Sci, 2020, 99(2): 1199–1208. |

| [24] | HAN J L, AHMAD H I, JIANG X P, et al. Role of genome-wide mRNA-seq profiling in understanding the long-term sperm maintenance in the storage tubules of laying hens[J]. Trop Anim Health Prod, 2019, 51(6): 1441–1447. DOI: 10.1007/s11250-019-01821-5 |

| [25] |

聂彬, 刘桂琼. 禽类贮精腺的研究进展[J]. 畜牧与兽医, 2014, 46(10): 106–109.

NIE B, LIU G Q. Advances in the study of sperm storage tubules in poultry[J]. Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Medicine, 2014, 46(10): 106–109. (in Chinese) |

| [26] | PIERSON E E M, MCDANIEL G R, KRISTA L M. Relationship between fertility duration and in vivo sperm storage in broiler breeder hens[J]. Br Poult Sci, 1988, 29(2): 199–203. DOI: 10.1080/00071668808417044 |

| [27] | BAKST M R, DONOGHUE A M, YOHO D E, et al. Comparisons of sperm storage tubule distribution and number in 4 strains of mature broiler breeders and in turkey hens before and after the onset of photostimulation[J]. Poult Sci, 2010, 89(5): 986–992. DOI: 10.3382/ps.2009-00481 |

| [28] | BAKST M R, BAUCHAN G. Lectin staining of the uterovaginal junction and sperm-storage tubule epithelia in broiler hens[J]. Poult Sci, 2016, 95(4): 948–955. |

| [29] | OKA T, SCHIMKE R T. Interaction of estrogen and progesterone in chick oviduct development:I.Antagonistic effect of progesterone on estrogen-induced proliferation and differentiation of tubular gland cells[J]. J Cell Biol, 1969, 41(3): 816–831. DOI: 10.1083/jcb.41.3.816 |

| [30] | SAH N, MISHRA B. Regulation of egg formation in the oviduct of laying hen[J]. World Poult Sci J, 2018, 74(3): 509–522. DOI: 10.1017/S0043933918000442 |

| [31] | ITO T, YOSHIZAKI N, TOKUMOTO T, et al. Progesterone is a sperm-releasing factor from the sperm-storage tubules in birds[J]. Endocrinology, 2011, 152(10): 3952–3962. DOI: 10.1210/en.2011-0237 |

| [32] | YOSHIMURA Y, OKAMOTO T, TAMURA T. Enhancement of progesterone receptor mRNA expression by estrogen in the shell gland of hens[J]. Jpn Poult Sci, 1994, 31(2): 137–142. DOI: 10.2141/jpsa.31.137 |

| [33] | DAS S C, NAGASAKA N, YOSHIMURA Y. Changes in the expression of estrogen receptor mRNA in the utero-vaginal junction containing sperm storage tubules in laying hens after repeated artificial insemination[J]. Theriogenology, 2006, 65(4): 893–900. DOI: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.07.004 |

| [34] |

迟毓婧, 杨增明. 孕酮调节途径在着床过程中的作用[J]. 生理科学进展, 2008, 39(3): 275–278.

CHI Y J, YANG Z M. Roles of progesterone-regulated genes in embryo implantation[J]. Progress in Physiological Sciences, 2008, 39(3): 275–278. (in Chinese) |