2. Department of Anesthesiology, Chiang Mai University Hospital, Thailand;

3. Division of General Surgery, Yasothorn hospital, Yasothorn province

During operation, several factors influence on hemodynamic parameters, such as the depth of anesthesia, blood loss or the intensity of painful surgical stimuli.[1] Perioperative fluid therapy for shock resuscitation guided by only clinical evaluation may lead into the early stage of shock, which is compensated by the change in systemic vascular resistance or cardiac output. However, insufficient or excessive volume administration may disturb microcirculation, [2-3] or increases the risk of anastomotic leakage; delays the return of postoperative bowel function and prolongs duration of hospital stay.[4] Thus, patients undergoing moderate to high risk surgery require high fidelity and more reliable parameter to guide fluid responsiveness. As a result, the trend has been changed into the perioperative goal-directed therapy (PGDT), [5-8] which maintains the specific Frank-Starling curve of each individualized patient by using the flow parameters of cardiac output and dynamic parameters from heart-lung interaction, such as stroke volume variation (SVV), pulse pressure variation (PPV), pleth variability index (PVI), predicting fluid responsiveness during mechanical ventilation.[9-10] Zimmerman et al. showed that non-invasive pleth variability index (PVI) predicts fluid responsiveness as accurately as does the invasive stroke volume variation.[11] In addition, The noninvasive method for estimated continuous cardiac output (esCCO) measurement uses a technique involving determination of the pulse wave transit time (PWTT), which consists of a pre-ejection period, pulse wave transit time through the artery, and pulse wave transit time through the peripheral arteries.[12] Based on the relationship between PWTT and stroke volume, the noninvasive device provides esCCO measurements using the traditional routine non-invasive electrocardiogram (ECG), pulse oximeter wave, and non-invasive blood pressure. Thus, it may be a useful technique for optimizing perioperative treatment.

We hypothesized that the additional use of non-invasive hemodynamic guided perioperative fluid optimization for the prevention of compensated shock might enhance the recovery after surgery in major abdominal surgery. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to compare the return of gastrointestinal function between non-invasive guided perioperative goal-directed therapy and traditional fluid therapy in major abdominal surgery patients, and the secondary objective was to compare the cost of treatment and the length of stay in hospital between the two treatment groups.

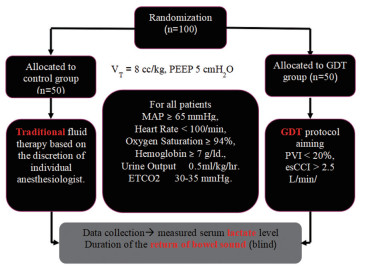

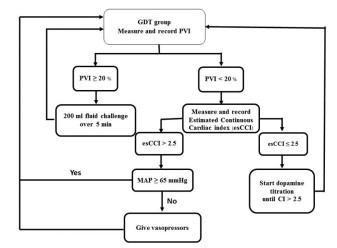

MethodsAfter the study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (Yasothorn Provincial Health Office: IRB No. HE6003 Dated 28 April 2017), and approved for Thai clinical trial registry (TCTR20170515001 Dated 15 May 2017), written informed consent was obtained from each patient enrolled. One hundred elective major abdominal surgery patients were prospectively included in the study. Inclusion criteria were adult patients undergoing elective open major abdominal surgery with estimated blood loss >500 ml, expected operative time >60 min, age more than 18 years. Exclusion criteria were patients underwent gynecological surgery, trauma, sepsis, respiratory failure, acute renal failure, cardiac arrhythmia, heart failure, thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy. Patients were screened for eligibility by a member of the research team. Patients meeting inclusion criteria were randomized and allocated to receive different perioperative hemodynamic management regimens by sequence from Randomization.com (21936). Control group (n=50) received traditional fluid therapy based on the discretion of individual anesthesiologists on the clinical and Holliday-Segar nomogram. PGDT group (n=50) received perioperative goal directed therapy (PGDT) protocol based on non-invasive guided intravenous fluid and inotropic support to maintain pleth variability index (PVI) less than20 % (Root Masimo, USA) and estimated continuous cardiac index (esCCI) > 2.5 L/min/m2 (BSM-9101 Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 1 and 2).

|

Figure 1 Randomization |

|

Figure 2 Goal-directed therapy; GDT) |

Patient characteristics were no significant difference among the groups in any of the variables. The returning of the bowel sound and the starting of soft diet therapy was significantly faster in the PGDT group (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, respectively). The overall cost of treatment was significantly lower (P= 0.023) and the length of stay in the hospital was significantly shorter in the PGDT group (P=0.003). However, the changes in blood lactate level immediately after surgery of both groups were different.

| Table 1 Patient characteristics |

| Table 2 Operative time, perioperative fluid balance and study variable |

Perioperative fluid optimization for the compensated shock prevention using PVI and esCCO enhanced the recovery after surgery in major abdominal surgery patients. This study demonstrated the faster return of gastrointestinal function in the non-invasive guided perioperative goal-directed therapy compare to the traditional fluid therapy in major abdominal surgery patients, and the secondary objective the reduction of the cost of treatment and the length of stay in hospital in the non-invasive guided perioperative goal-directed therapy compared to the traditional fluid therapy.

Traditional fluid therapy in the present study is perioperative fluid management by using clinical finding and static hemodynamic parameter guided, for example, HR, blood pressure, urine output or CVP. In the PGDT study group, the present study used the heart-lung interaction dynamic parameter as the hemodynamic target for predicting fluid responsiveness using the PVI number 20% because there was no obvious cut off value of PVI guidance (14-20% is the range of gray zone of fluid responders and non-responders). These simplified non-invasive PGDT study protocol in the present study has been demonstrated that whether the type of fluids therapy or blood components were controlled under the decision of individual anesthesiologists or not, the fluid management under this PGDT protocol is able to enhance the recovery after surgery and reduce the cost of treatment and length of stay in hospital after major abdominal surgery.

ConclusionPerioperative fluid optimization for the compensated shock prevention enhanced the recovery of postoperative bowel function and reduced the cost of treatment and length of stay in hospital in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery

| [1] |

Bennett-Guerrero E, Welsby I, Dunn TJ, Young LR, Wahl TA, Diers TL, et al. The use of a postoperative morbidity survey to evaluate patients with prolonged hospitalization after routine, moderate-risk, elective surgery[J]. Anesthesia and analgesia, 1999, 89(2): 514-519. |

| [2] |

Mythen M, Webb A. Perioperative plasma volume expansion reduces the incidence of gut mucosal hypoperfusion during cardiac surgery[J]. Arch Surg, 1995, 130: 423-429. DOI:10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430040085019 |

| [3] |

Cannesson M. Arterial pressure variation and goal-directed fluid therapy[J]. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia, 2010, 24(3): 487-497. DOI:10.1053/j.jvca.2009.10.008 |

| [4] |

Abbas S, Hill A. Systematic review of the literature for the use of oesophageal Doppler monitor for fluid replacement in major abdominal surgery[J]. Anaesthesia, 2008, 63: 44-45. |

| [5] |

Benes J, Chytra I, Altmann P, Hluchy M, Kasal E, Svitak R, et al. Intraoperative fluid optimization using stroke volume variation in high risk surgical patients: results of prospective randomized study[J]. Crit Care, 2010, 14: 118. DOI:10.1186/cc8841 |

| [6] |

Hamilton M, Cecconi M, Rhodes A. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of preemptive hemodynamic intervention to improve postoperative outcomes in moderate and high-risk surgical patients[J]. Anesthesia and analgesia, 2011, 112: 1392-1402. DOI:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181eeaae5 |

| [7] |

Cecconi M, Corredor C, Arulkumaran N, Abuella G, Ball J, Grounds RM, et al. Clinical review: Goal-directed therapy-what is the evidence in surgical patients? The effect on different risk groups[J]. Crit Care, 2013, 17(2): 209. |

| [8] |

Benes J, Giglio M, Brienza N, Michard F. The effects of goal-directed fluid therapy based on dynamic parameters on post-surgical outcome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J]. Crit Care, 2014, 18(5): 584. DOI:10.1186/s13054-014-0584-z |

| [9] |

Hofer C, Senn A, Weibel L, Zollinger A. Assessment of stroke volume variation for prediction of fluid responsiveness using the modified FloTrac and PiCCOplus system[J]. Crit Care, 2008, 12: 82. |

| [10] |

Le Manach Y, Hofer CK, Lehot JJ, Vallet B, Goarin JP, Tavernier B, et al. Can changes in arterial pressure be used to detect changes in cardiac output during volume expansion in the perioperative period[J]. Anesthesiology, 2012, 117(6): 1165-1174. DOI:10.1097/ALN.0b013e318275561d |

| [11] |

Zimmermann M, Feibicke T, Keyl C, Prasser C, Moritz S, Graf BM, Wiesenack C. Accuracy of stroke volume variation compared with pleth variability index to predict fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients undergoing major surgery[J]. Eur J Anaesthesiol, 2010, 27(6): 555-561. |

| [12] |

Sugo Y, Ukawa T, Takeda S, Ishihara H, Kazama T, Takeda J. A novel continuous cardiac output monitor based on pulse wave transit time[J]. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, 2010, 2010(10): 2853-2856. |

2018, Vol. 2

2018, Vol. 2