2. Department of Epidemiology, Tongliao Center for Disease Prevention and Control, Tongliao 028005, Inner Mongolia, China ;

3. Department of Neurology, Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University, Nantong 226001, Jiangsu, China

Objective We aimed to investigate the cumulative effect of high CRP level and apolipoprotein B-to-apolipoprotein A-1 (ApoB/ApoA-1) ratio on the incidence of ischemic stroke (IS) or coronary heart disease (CHD) in a Mongolian population in China.

Methods From June 2003 to July 2012, 2589 Mongolian participants were followed up for IS and CHD events based on baseline investigation. All the participants were divided into four subgroups according to C-reactive protein (CRP) level and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the IS and CHD events in all the subgroups.

Results The HRs (95% CI) for IS and CHD were 1.33 (0.84-2.12), 1.14 (0.69-1.88), and 1.91 (1.17-3.11) in the nlow CRP level with high ApoB/ApoA-1o, nhigh CRP level with low ApoB/ApoA-1o, and nhigh CRP level with high ApoB/ApoA-1o subgroups, respectively, in comparison with the nlow CRP level with low ApoB/ApoA-1o subgroup. The risks of IS and CHD events was highest in the nhigh CRP level with high ApoB/ApoA-1o subgroup, with statistical significance.

Conclusion High CRP level with high ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio was associated with the highest risks of IS and CHD in the Mongolian population. This study suggests that the combination of high CRP and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio may improve the assessment of future risk of developing IS and CHD in the general population.

In China, 3.14 million deaths were attributed to cardiovascular disease (CVD) in 2010 alone, with coronary heart disease (CHD) and ischemic stroke (IS) accounting for 30.25% and 19.44% of CVD deaths, respectively[1]. Both IS and CHD are ischemic vascular disorders, while atherosclerosis is the main pathological basis of IS and CHD.

Both inflammation and hyperlipidemia play major roles in atherothrombosis[2]. C-reactive protein (CRP) is an easily measurable and reliable biomarker of inflammatory status. Previous studies[3], but not all[4-6], have shown that increased CRP level significantly increases the risk of IS and CHD. Meanwhile, several studies have shown that the lipid-associated proteins, particularly the apolipoprotein B-to-apolipoprotein A-1 (ApoB/ApoA-1) ratio, which indicates the balance between atherogenic and anti-atherosclerotic particles, are more effective predictors of cardiovascular risk than the other cholesterol[7-9]. High ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio has been demonstrated to increase the risk of IS and CHD[10-12].

Recently, a few studies found an indication of the synergistic effects of inflammation and dyslipidemia on the risk of developing CVD[13-14]. Hence, we hypothesized a co-effect between the inflammatory biomarkers CRP and dyslipidemia, especially high ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio, on the incidences of IS and CHD. However, the relationship of high CRP and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio to the risk of developing IS and CHD in Mongolians has not been reported yet. We therefore examined the cumulative effect of high CRP and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio on the risk of developing IS and CHD in a Mongolian population from Inner Mongolia, China.

METHODS Study SubjectsThis prospective cohort study was conducted from June 2003 to July 2012 in Inner Mongolia, an autonomous region in Northern China. The participant selection and data collection were based on previously reported methods[15]. The study participants were recruited from 32 villages in Kezuohou Banner (county) and Naiman Banner in Inner Mongolia, China. Most of the local residents were Mongolians who had lived in their villages for many generations and maintained their traditional diet and lifestyle. Among 3457 Mongolian residents aged≥20 years who were living in these villages, 2589 were selected to participate in this study. None of the participants had chronic kidney disease, malignant tumor, thyroid disease or adrenalopathy, or acute infectious disease. This study was approved by the Soochow University Ethics Committee in China. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Data CollectionBaseline information on demographic characteristics, lifestyle-related risk factors, history of disease, and family history of CVD was collected by trained investigators by using a standardized questionnaire. Alcohol consumption was defined as consuming an average of 25 g of alcohol per day for≥1 year during the past years, from any type of alcoholic beverage. Height, body weight, and waist circumference were measured by using the standard methods. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured on the right arm by using a mercury sphygmomanometer, according to a standard protocol in the sitting position[16]. The first and fifth Korotkoff sounds were recorded as SBP and DBP, respectively. The mean of three BP measurements was calculated for the data analysis. Hypertension was defined as a SBP of≥140 mm Hg and/or a DBP of≥90 mm Hg, and/or use of antihypertensive medication within the previous 2 weeks.

Fasting blood samples were collected from each participant in the morning. Plasma and serum samples were frozen at-80℃until laboratory testing. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level was measured by using a modified hexokinase enzymatic method[17]. Total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglyceride (TG) levels were measured enzymatically on a Beckman Synchrony CX5 Delta Clinical System (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, California, USA) with commercial reagents[18]. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels were calculated by using the Friedwald equation for participants who had triglyceride levels of < 400 mg/dL[19]. Serum CRP, ApoB, and ApoA-1 levels were determined by using an immunoturbidimetric assay on a Beckman SynchronCX5 Delta Clinical System with commercial reagents.

Follow-up and Outcome AssessmentAll the participants were followed up from June 2003 to July 2012. The incidences of IS and CHD during the follow-up period were the primary study outcomes. Participants who did not experience IS or a CHD, who died from other causes, or who were lost to follow-up were defined as censored. If the participants were interviewed and found to have IS or CHD, the IS and CHD incidence data were defined as the end point data. Data were censored at the time of contact if the participant was reached and was found to have had no IS or CHD and on the day we last contacted the participant if the participant was lost to follow-up. For those who died from other causes, data were censored at the time of death indicated in the medical records. Since 2004, household surveys of all the participants were conducted every 2 years on average to determine the incidences of new IS and CHD events. If the participants were unable to communicate or had died, trained investigators interviewed the participants’relatives. If the participants reported occurrence of IS or CHD during the period since the last survey, the staff reviewed the hospital records, including outpatient or inpatient records and the discharge summary. CHD was diagnosed based on symptoms, electrocardiographic changes, cardiac enzymes, and autopsy findings, according to the criteria of the World Health Organization MONICA project[20]. Stroke was defined as sudden onset of neurological symptoms lasting≥24 h and positive findings on cranial computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging[21]. Participants diagnosed as having IS or CHD at the hospital were considered to have the outcome of interest in this study.

Statistical AnalysesStatistical data on the participants’baseline characteristics were calculated separately for the two groups with and without study outcomes. Mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile ranges) values were used to describe normally distributed or not normally distributed continuous variables, and frequencies were used to describe categorical variables. Differences between the two groups were tested by using t test for normally distributed continuous variables, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for variables that followed a skewed distribution, and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. Serum CRP levels were log transformed because of skewness before the statistical analysis. CRP level was included as 2 categories as follows: low CRP [log CRP < 1.06 mg/L (bottom 3 quartiles)] and high CRP [log CRP≥1.06 mg/L (upper quartile)]. The ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio was entered as a categorical variable with 2 levels [low ApoB/ApoA-1 < 0.505 (bottom 3 quartiles) and high ApoB/ApoA-1≥0.505 (upper quartile)]. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to determine the hazard ratios (HRs) for IS and CHD associated with high CRP level and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio, respectively, adjusting for age, sex, BMI, smoking, drinking, blood glucose level, hypertension, and lipid levels.

Then, the participants were divided into four subgroups as follows: low CRP level with low ApoB/ApoA-1, low CRP with high ApoB/ApoA-1, high CRP with low ApoB/ApoA-1, and high CRP with high ApoB/ApoA-1. The Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate the cumulative incidence of events for the four subgroups, and the cumulative incidences of events were compared among the four groups by using the log-rank test. Furthermore, we used the Cox proportional hazard models to compute HRs for IS and CHD across the four subgroups, adjusting for age, sex, BMI, smoking, drinking, blood glucose level, hypertension, and lipid levels. All P values were two-tailed. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed by using the SAS statistical package version 9.3 (SAS institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTSThe study included 2589 participants who were followed up for a mean period 9.2 years. Six participants were lost to follow up, resulting in a follow-up rate of 99.8%. Among the 2589 participants, 53 were excluded because of lack of data on CRP, ApoB, or ApoA-1 level. Finally, 2536 participants were included in the analysis. After 23, 114 person-years of follow-up, 151 IS or CHD events occurred. The cumulative incidence of IS and CHD events was 5.95%, and the incidence density was 653 per 100, 000 person-years.

Table 1 presents a comparison of basic characteristics between the subjects with and those without outcome. The participants who developed IS or CHD during the 9.2 years of follow-up were older, more often male, smokers, and more likely to have a family history of CVD, hypertension, high FPG level, and TC level. In addition, they had significantly higher CRP levels, ApoB levels, and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratios (P < 0.05). However, no significant difference in drinking habits, BMI, TG level, and ApoA-1 level were found between the two groups. Multivariate adjusted HRs for the association of CRP level and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio and risk of developing IS and CHD are shown in Table 2. In crude models, high CRP level and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio were significantly associated with the risk of IS or CHD, respectively. After further adjustment for age, sex, drinking, smoking, hypertension, FPG level, BMI, lipid levels, family history of CVD, CRP level, and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio, CRP level was not significantly associated with the incidences of IS and CHD, regardless of whether it was treated as a continuous or categorical variable. Only high ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio remained marginally significant [HR (95% confidence interval, CI), 1.45 (1.00-2.08)] as a categorical variable.

|

|

Table 1 Characteristics of the Participants Who Developed and Did not Develop IS or CHD |

|

|

Table 2 Hazard Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals of IS and CHD Associated with CRP and ApoB/ApoA-1 Ratio |

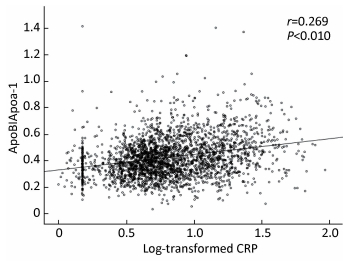

Pearson correlation analysis revealed a significant linear relationship between CRP level and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio. As shown in Figure 1, ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio positively correlated to log-transformed CRP level, with a significant coefficient of 0.269 (P < 0.01).

|

Download:

|

| Figure 1 Scatterplot showing a significant and positive correlation of log-transformed CRP to ApoB/ApoA-1. | |

The participants were further divided into 4 groups according to CRP levels and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio. Figure 2 shows that the cumulative incidences of IS and CHD were 4.30%, 6.56%, 8.00%, and 11.97% in the‘low CRP level with low ApoB/ApoA-1’, ‘high CRP level with low ApoB/ApoA-1’, ‘low CRP level with high ApoB/ApoA-1’, and‘high CRP level with high ApoB/ApoA-1’groups, respectively (P < 0.001). The cumulative incidence of IS and CHD was highest in the‘high CRP level with high ApoB/ApoA-1’group. After 23, 114 person-years of follow-up, 76 IS and 75 CHD events occurred. The multivariate adjusted HRs (95% CI) were 2.04 (0.97-4.27) and 1.93 (1.00-3.70) for IS and CHD, respectively. The participants with high CRP levels and high ApoB/ApoA-1 had marginally significant risk of developing IS or CHD after adjustment for multivariable, compared with those with low CRP levels and low ApoB/ApoA-1. Table 3 shows that the participants with low CRP levels and high ApoB/ApoA-1 (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.84-2.12) or high CRP levels and low ApoB/ApoA-1 (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.69-1.88) had no significant risk of developing IS and CHD after adjustment for multivariable, compared with those with low CRP levels and low ApoB/ApoA-1. However, the participants with high CRP levels and high ApoB/ApoA-1 had a significantly increased risk of developing IS and CHD. The corresponding age/sex-and multivariable-adjusted HRs (95% CI) were 2.03 (1.32-3.12) and 1.91 (1.17-3.11), respectively. The‘high CRP level with high ApoB/ApoA-1’subgroup still had the highest risk of developing IS and CHD. Significant interactions of CRP×ApoB/ApoA-1 on the risk of developing IS and CHD were observed in the multivariate analysis (HR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.10-2.61).

|

Download:

|

| Figure 2 Cumulative incidence curve of IS and CHD according to CRP level with ApoB/apoA-1 level. | |

|

|

Table 3 Adjusted Hazard Ratio for IS and CHD Incidence According to CRP with ApoB/ApoA-1 Lever |

In this cohort study, we found that higher ApoB/ApoA-1 ratios were associated with increased incidence of IS and CHD events among the Inner Mongolian population. Notably, such association remained marginally significant after adjustment for age, sex, drinking, smoking, hypertension, FPG level, BMI, lipid levels, family history of CVD, and CRP. Some studies have shown that high ApoB/ApoA-1 ratios may increase the risk of developing IS and CHD[10-12]. The results of the Apolipoprotein-Related Mortality Risk Study, a large prospective population-based study, indicated that high ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio was strongly and positively related to increased risk of fatal myocardial infarction in both men and women[7]. As we have known, ApoB is the major apolipoprotein in all potentially atherogenic lipoprotein particles and ApoA-1 manifests several anti-atherogenic effects. An elevated ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio reflects an adverse imbalance between atherogenic and anti-atherogenic lipoprotein particles, which may result in enhanced atherosclerotic burden[9, 22]. ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio, as a predictor of CVD risk, was superior to any other conventional lipid index[9, 23-25]. Our findings also suggest that the ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio at baseline may be a predictor of future IS or CHD events.

Inflammation has been shown to be the primary key to the time course of atherosclerosis. CRP expression has been found to activate a number of processes involved in inflammatory reactions[26-27]. Large population-based studies suggested that CRP plays a role in predicting cardiovascular events[28-31]. For example, in the study of Cushman et al.[29], the relative risk (RR) (95% CI) of CHD with increased CRP level was 1.45 (1.14-1.86) in the elderly population. The Framingham Heart Study[28] showed that the HR for total CVD with log (CRP) was 1.26 (1.12-1.40) and the HR for CHD was 1.34 (1.14-1.58). However, in the Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) study[32], the RR of stroke or CHD associated with the top-tertile CRP levels was 1.20 (0.83-1.75) compared with the bottom-tertile CRP levels. In the Rotterdam study[6], HR was 1.38 (0.98-1.94), showing a relatively weak association. In our study, the HR for IS or CHD with high CRP levels was 1.23 (0.84-1.80) among the Mongolian population. Although we observed a weak association between high CRP level and the incidence of IS or CHD, we found that the participants with both high CRP level and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio had the highest cumulative incidence of IS and CHD. These participants also had the highest risk of developing IS and CHD among the various groups, with statistical significance and independent of other classic risk factors.

Both inflammation and hyperlipidemia play major roles in atherothrombosis[2]. In our study, the results of the Spearman correlation analysis demonstrated that ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio was significantly related to CRP level (P < 0.01), which was similar to the results in the study of Xu et al.[33] Several studies have shown that hyperlipidemia seem to promote inflammation and then aggravate the progression of ischemic lesions[34]. Meanwhile, treatment with statins was reported to possibly prevent coronary events among individuals with relatively low lipid levels and high CRP levels[35]. Inflammation, as assessed based on hs-CRP level, and hyperlipidemia appear to play key roles in the development of cerebrovascular atherosclerosis and IS, consistent with their well-known roles in the pathophysiological mechanisms of coronary atherosclerosis and CHD[36]. Holme et al suggested indications, but without clear evidence, that inflammation and dyslipidemia act synergistically on the risk of developing major cardiovascular events[13]. Our findings seem to indicate a cumulative effect of high CRP level and high ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio on incidences of IS and CHD. Our finding was similar to that of Hrira et al.[14], which suggested that the synergistic effects between ApoB and CRP levels might increase the risk of developing IS and CHD. The mechanisms underlying this phenomenon may be that the coexistence of increased CRP level with high ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio may accelerate the atherosclerotic process, which increases the risks of IS and CHD incidence in the future. Our study findings suggest that combined use of the two indexes-high CRP level and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio-may improve the assessment of risks of IS and CHD in the general population in the future. Therefore, examination for CRP level and ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio at the same time and combined use of these two indexes may be considered as good screening methods for people at high risk of developing CVDs, including IS and CHD.

Our study has several strengths worth mentioning. The study participants were homogeneous regarding their genetic background and environmental exposures, and the study data were collected with rigid quality control. In addition, important covariables were measured and controlled in the analysis. The relatively long observation period and high follow-up rate enabled us to identify a less biased association between exposure variables and outcome events. The limitations of our study included the following: First, the ApoA-1 and ApoB and CRP levels were measured only once at baseline; therefore, intraindividual variation during the follow-up could not be assessed. Second, we did not collect data on the use of certain kinds of drugs that can lower CRP levels, such as statins. However, as well known, people from relatively isolated areas who have high lipid levels almost always do not use these medications because they have a low knowledge rate about hyperlipidemia. Third, about 25% of the baseline population did not participate in the study, which might have introduced some selection bias. However, this bias is minimal because it is unlikely that the participants decided not to participate because of their CRP levels or ApoB/ApoA-1 ratios.

In conclusion, our study indicated that high ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio was an independent risk factor of IS and CHD, and high CRP level with high ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio conferred the highest risks of IS and CHD in the Mongolian population. This study suggests that combined use of high CRP level and high ApoB/ApoA-1 ratio may improve the assessment of the risks of IS and CHD in the general population in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the study participants, the Kezuohou Banner Center for Disease Prevention and Control and the Naiman Banner Center for Disease Prevention and Control for their support and assistance.

| 1. | Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y, et al. Rapid health transition in China:1990-2010:findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010[J]. Lancet , 2013, 381 :1987–2015. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61097-1 |

| 2. | Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis[J]. Nature , 2002, 420 :868–74. doi:10.1038/nature01323 |

| 3. | Buckley DI, Fu R, Freeman M, et al. C-reactive protein as a risk factor for coronary heart disease:a systematic review and meta-analyses for the U.S[J]. Preventive Services Task Force.Ann Intern Med , 2009, 151 :483–95. |

| 4. | Rost NS, Wolf PA, Kase CS, et al. Plasma concentration of C-reactive protein and risk of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack The Framingham Study[J]. Stroke , 2001, 32 :2575–9. doi:10.1161/hs1101.098151 |

| 5. | Luna JM, Moon YP, Liu KM, et al. High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein and Interleukin-6-Dominant Inflammation and Ischemic Stroke Risk The Northern Manhattan Study[J]. Stroke , 2014, 45 :979–87. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002289 |

| 6. | Bos MJ, Schipper CM, Koudstaal PJ, et al. High serum C-reactive protein level is not an independent predictor for stroke:the Rotterdam Study[J]. Circulation , 2006, 114 :1591–8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.619833 |

| 7. | Walldius G, Jungner I, Holme I, et al. High apolipoprotein B, low apolipoprotein A-I, and improvement in the prediction of fatal myocardial infarction (AMORIS study):a prospective study[J]. Lancet , 2001, 358 :2026–33. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07098-2 |

| 8. | Walldius G, Jungner I. Apolipoprotein B and apolipoprotein A-I:risk indicators of coronary heart disease and targets for lipid-modifying therapy[J]. J Intern Med , 2004, 255 :188–205. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01276.x |

| 9. | Sniderman AD, Furberg CD, Keech A, et al. Apolipoproteins versus lipids as indices of coronary risk and as targets for statin treatment[J]. Lancet , 2003, 361 :777–80. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12663-3 |

| 10. | Thompson A, Danesh J. Associations between apolipoprotein B, apolipoprotein AI, the apolipoprotein B/AI ratio and coronary heart disease:a literature-based meta-analysis of prospective studies[J]. J Intern Med , 2006, 259 :481–92. doi:10.1111/jim.2006.259.issue-5 |

| 11. | Bhatia M, Howard SC, Clark TG, et al. Apolipoproteins as predictors of ischaemic stroke in patients with a previous transient ischaemic attack[J]. Cerebrovasc Dis , 2006, 21 :323–8. doi:10.1159/000091537 |

| 12. | Walldius G, Aastveit AH, Jungner I. Stroke mortality and the apoB/apoA-I ratio:results of the AMORIS prospective study[J]. J Intern Med , 2006, 259 :259–66. doi:10.1111/jim.2006.259.issue-3 |

| 13. | Holme I, Aastveit AH, Hammar N, et al. Inflammatory markers, lipoprotein components and risk of major cardiovascular events in 65, 005 men and women in the Apolipoprotein MOrtality RISk study (AMORIS)[J]. Atherosclerosis , 2010, 213 :299–305. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.08.049 |

| 14. | Hrira MY, Kerkeni M, Hamda BK, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I, apolipoprotein B, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and severity of coronary artery disease in Tunisian population[J]. Cardiovasc Pathol , 2012, 21 :455–60. doi:10.1016/j.carpath.2012.02.009 |

| 15. | Li H, Xu T, Tong W, et al. Comparison of cardiovascular risk factors between prehypertension and hypertension in a Mongolian population, Inner Mongolia, China[J]. Circ J , 2008, 72 :1666–73. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-08-0138 |

| 16. | Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure[J]. Hypertension , 2003, 42 :1206–52. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2 |

| 17. | Sitzmann FC, Eschler P. Enzymatic determination of blood glucose with a modified hexokinase method[J]. Med Klin , 1970, 65 :1178–83. |

| 18. | Allain CC, Poon LS, Chan CS, et al. Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol[J]. Clin Chem , 1974, 20 :470–5. |

| 19. | Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge[J]. Clin Chem , 1972, 18 :499–502. |

| 20. | Tuomilehto J, Kuulasmaa K. WHO MONICA Project:assessing CHD mortality and morbidity[J]. Int J Epidemiol , 1989, 18 :S38–45. |

| 21. | World Health Organization. Stroke-1989.Recommendations on stroke prevention, diagnosis, and therapy.Report of the WHO Task Force on Stroke and other Cerebrovascular Disorders[J]. Stroke , 1989, 20 :1407–31. doi:10.1161/01.STR.20.10.1407 |

| 22. | Jungner I, Walldius G, Holme I, et al. Apolipoprotein B and A-I in relation to serum cholesterol and triglycerides in 43, 000 Swedish males and females[J]. Int J Clin Lab Res , 1992, 21 :247–55. doi:10.1007/BF02591655 |

| 23. | Barter PJ, Rye KA. The rationale for using apoA-I as a clinical marker of cardiovascular risk[J]. J Intern Med , 2006, 259 :447–54. doi:10.1111/jim.2006.259.issue-5 |

| 24. | Sniderman AD, Jungner I, Holme I, et al. Errors that result from using the TC/HDL C ratio rather than the apoB/apoA-I ratio to identify the lipoprotein-related risk of vascular disease[J]. J Intern Med , 2006, 259 :455–61. doi:10.1111/jim.2006.259.issue-5 |

| 25. | Walldius G, Jungner I, Aastveit AH, et al. The apoB/apoA-I ratio is better than the cholesterol ratios to estimate the balance between plasma proatherogenic and antiatherogenic lipoproteins and to predict coronary risk[J]. Clin Chem Lab Med , 2004, 42 :1355–63. |

| 26. | Spence JD, Norris J. Infection, inflammation, and atherosclerosis[J]. Stroke , 2003, 34 :333–4. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000054049.65350.EA |

| 27. | Corrado E, Novo S. Role of inflammation and infection in vascular disease[J]. Acta Chir Belg , 2005, 105 :567–79. doi:10.1080/00015458.2005.11679782 |

| 28. | Wilson PW, Pencina M, Jacques P, et al. C-reactive protein and reclassification of cardiovascular risk in the Framingham Heart Study[J]. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes , 2008, 1 :92–7. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.831198 |

| 29. | Cushman M, Arnold AM, Psaty BM, et al. C-reactive protein and the 10-year incidence of coronary heart disease in older men and women:the cardiovascular health study[J]. Circulation , 2005, 112 :25–31. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.504159 |

| 30. | Folsom AR, Aleksic N, Catellier D, et al. C-reactive protein and incident coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study[J]. Am Heart J , 2002, 144 :233–8. doi:10.1067/mhj.2002.124054 |

| 31. | Rost NS, Wolf PA, Kase CS, et al. Plasma concentration of C-reactive protein and risk of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack:the Framingham study[J]. Stroke , 2001, 32 :2575–9. doi:10.1161/hs1101.098151 |

| 32. | Cesari M, Penninx BW, Newman AB, et al. Inflammatory markers and onset of cardiovascular events:results from the Health ABC study[J]. Circulation , 2003, 108 :2317–22. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000097109.90783.FC |

| 33. | Xu W, Li R, Zhang S, et al. The relationship between high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and ApoB, ApoB/ApoA1 ratio in general population of China[J]. Endocrine , 2012, 42 :132–8. doi:10.1007/s12020-012-9599-x |

| 34. | Faraj M, Messier L, Bastard JP, et al. Apolipoprotein B:a predictor of inflammatory status in postmenopausal overweight and obese women[J]. Diabetologia , 2006, 49 :1637–46. doi:10.1007/s00125-006-0259-7 |

| 35. | Munford RS. Statins and the acute-phase response[J]. N Engl J Med , 2001, 344 :2016–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM200106283442609 |

| 36. | Everett BM, Kurth T, Buring JE, et al. The relative strength of C-reactive protein and lipid levels as determinants of ischemic stroke compared with coronary heart disease in women[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol , 2006, 48 :2235–42. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.030 |

2016, Vol. 29

2016, Vol. 29