| 肠道菌群及饮食对IBD的影响 |

IBD包括溃疡性结肠炎(Ulcerative Colitis, UC)、克罗恩病(Crohn’s disease, CD)和一些不同于以上两种类型的未定型结肠炎(Indeterminate colitis, IC)。UC由弥漫性粘膜炎症和嗜中性粒细胞组成, 通常限制在结肠组织中, 且主要发病部位在固有层和隐窝中[1-2]。与UC相比CD是可以累及胃和肠道任何部位的炎症, CD的优先累及区域是小肠, 尤其是回肠末端和结肠。多项研究表明, 肠道菌群在IBD患者结肠炎发病和治疗过程中起着关键作用[3]。

饮食是潜在的可影响IBD炎症严重程度的环境风险因素。饮食促使肠道菌群的组成和功能改变(被称为营养不良)已成为IBD的重要致病因素。IBD患者的营养不良可以导致所有主要的致病因素, 例如上皮屏障功能受损, 细菌识别缺陷, 抗原递呈和自噬, T细胞反应失调导致先天性免疫反应异常[1-4]。研究表明, IBD患者往往在炎症初期时就已患有不同程度的营养不良, 患者营养不良会加重IBD的病情, 而IBD炎症的发展、药物或手术治疗则会进一步加重营养不良, 两者相互影响, 因此, 在IBD的治疗中, 饮食有着举足轻重的地位[5]。国内外的很多研究结果表明, 特殊饮食支持有助于疾病缓解、促进肠胃黏膜愈合, 减少不良反应的发生, 合适的饮食不仅能纠正IBD患者的营养不良, 还能缓解其临床症状, 修复肠道损伤和保持病情稳定, 甚至可以取代药物或手术成为一种极其重要的治疗手段[6]。因此, 特殊饮食可能会被纳入IBD的治疗策略。

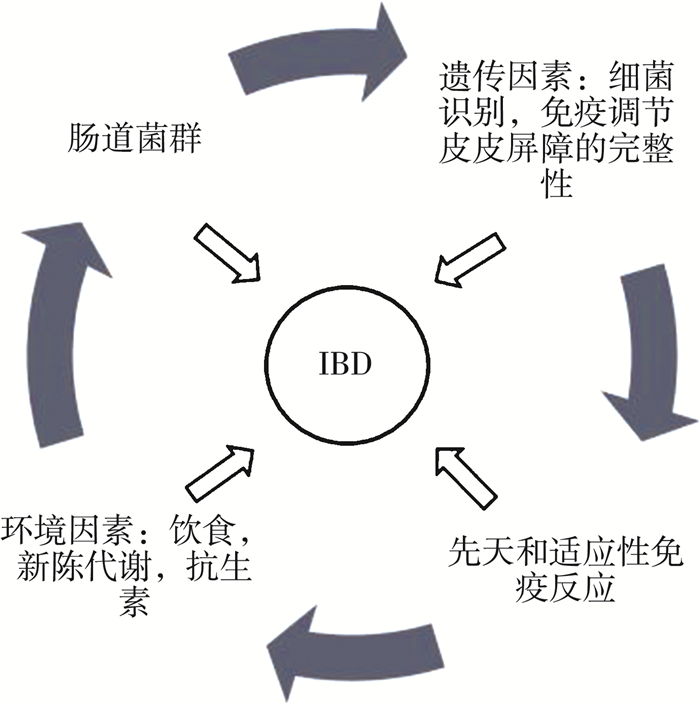

1 肠道菌群对炎症性肠炎的影响 1.1 肠道菌群的组成和功能人体肠道内存在着复杂的微生物群落, 包括真菌, 寄生虫, 病毒, 古细菌和细菌, 统称为肠道微生物群[7-8]。人类肠道微生物宏基因组计划(Metagenomics of the Human Intestinal Tract, MetaHIT)通过代谢组学研究发现人类粪便标本中共有330万个不同种类微生物基因[9]。但肠道微生物主要只分布在四个门中, 即硬壁菌门, 拟杆菌门, 放线菌门和变形菌门[10]。肠道上皮和肠道的微生物生态系统接触, 并建立了互惠互利动态关系。肠道菌群显示出重要的代谢, 免疫和肠道保护功能(图 1)。微生物通过代谢来发酵碳水化合物和难消化的低聚糖, 并合成短链脂肪酸(乙酸盐, 丙酸和丁酸等), 而短链脂肪酸是肠上皮细胞的主要能量来源[11]。此外, 肠道菌群还可以合成维生素B和K, 烟酸, 生物素和叶酸, 并完成胆汁酸的肠肝循环[12]。在免疫学上, 肠道菌群通过产生微生物相关的分子模式(Microbial-Associated Molecular Patterns, MAMPS)来促进肠道免疫调节与先天和适应性免疫系统的相互作用, 这种模式能被肠道免疫细胞的特定受体识别[13]。而且肠道菌群通过产生抗菌因子并阻止病原菌的定殖来限制潜在病原菌的营养从而阻止其生长, 通过所有这些功能, 肠道菌群在维护肠上皮的完整性, 影响肠上皮细胞更新, 凋亡以及紧密连接蛋白的表达和功能方面发挥着关键作用。大量研究表明, 肠道菌群产生的信号因子可以控制肠道上皮细胞的凋亡, 增殖和分化, 从而导致动物肠道上皮的形态和结构发生改变[14-15]。

|

| 图 1 影响IBD的因素 |

1.2 肠道菌群在IBD发病机制中的作用

益生菌及其共生细菌对紧密连接(Tight Junctions, TJs)屏障具有积极作用, 增强了肠上皮对病原菌的抗性, 并降低了可能引起炎症的抗原细胞通透性[16]。在葡聚糖硫酸钠(Dextran Sulfate Sodium, DSS)诱导的实验性结肠炎动物模型中, 益生菌通过恢复TJs蛋白的表达来防止上皮屏障功能障碍和肠道上皮通透性增加[17]。此外, 体外研究表明, 肠道菌群的发酵产物短链脂肪酸(Short-Chain Fatty Acids, SCFA)通过单磷酸腺苷(Adenosine 5′-monophosphate, AMP)激活的蛋白激酶途径调节TJs的装配, 增加了肠道上皮单层耐药性[18]。肠道菌群在生理免疫应答的过程和功能中起着至关重要的作用。同时, 人体通过免疫应答机制调节肠道菌群的组成和功能[19]。在最近几年的研究中, 已经发现了大量肠道菌群在IBD免疫发病机理中有重要作用的证据, 因为肠道菌群可以通过与环境因素的相互作用或宿主的遗传易感性进行修饰[20]。上皮屏障功能障碍以及由于肠上皮细胞间连接而引起的上皮细胞通透性改变可能是IBD发病机制中的关键因素[21]。具体来说, 肠上皮细胞充当物理屏障, 阻止外来病原体的入侵[22]。在患有IBD的人体模型和实验模型上的研究表明, 长时间的炎症与TJs的破坏相结合, 会导致肠上皮细胞连接完整性丧失[23-24]。这个过程促进肠道内病原体通过上皮屏障的间隙以及固有层中Toll样受体(Toll-Like Receptor, TLR), 特异的葡聚糖受体Dectin-1和半胱氨酸蛋白酶补充结构域蛋白9(Caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 9, CARD9)的活化, 导致更严重的炎症反应[23-24]。

1.3 IBD患者肠道中菌群多样性降低目前有很多报道显示IBD患者的肠道菌群和健康人群的肠道菌群相比具有菌群功能失调, 多样性降低和菌群不稳定性升高的特征[25]。健康肠道中正常存在的微生物(例如, 拟杆菌和硬壁菌门的成员)在IBD患者肠道中严重减少, 同时有害菌群随之增加(例如, 放线菌和变形杆菌)[26]。除了菌群组成的变化外, 在IBD患者肠道中还观察到微生物多样性降低[27]。研究表明, 与健康人群相比患有CD的患者其肠道微生物群中含有大量的黏附浸润性大肠杆菌, 致病性耶尔森氏菌和艰难梭菌[28-30]。IBD患者肠道中细菌种类水平的改变与肠道微生物群关键功能的改变有关。也就是说, 这种改变是由于SCFA的代谢减少(特别是乙酸, 丙酸和丁酸的减少), 生物合成氨基酸减少, 营养缺陷, 氧化应激反应和毒素分泌增加导致的[31]。由于SCFA参与肠道上皮细胞生命过程的调控(基因表达、分化、增殖、趋化性和凋亡), 因此它们在IBD发病机理中的作用引起了大量关注[32]。肠道菌群组成的改变导致其对病原菌定殖的抗性和限制病原菌生长的作用降至最低。研究表明, 与IBD相关的微生物群富含致病菌[33-34]。然而, 目前还没有鉴定出哪些特定病原菌能引发IBD。由于环境或饮食的变化, 遗传易感个体中的某些自身携带的病原菌可能具有致病作用, 从而促进肠道炎症的发生[35]。

1.4 粪便菌群移植(FMT)粪便菌群移植(Fecal Microbiota Transplant, FMT)作为一种细菌转移的治疗方法已引起人们的注意。FMT是用健康个体的粪便制备悬浮液并将其转移到患病受体胃肠道中的过程。这种治疗方法已被确立为治疗复发性艰难梭菌感染(Clostridium Difficile Infection, CDI)的高效疗法。在CDI患者中使用FMT的目的是恢复患此病的人群的肠道菌群稳态, 其成功率超过90%[36-41]。这些非常有前景的治疗结果导致美国胃肠病学会, 欧洲临床微生物学会和欧洲传染病学会在CDI的治疗指南中引入了FMT[42-43]。而现在FMT也被认为是治疗UC的一种新方法, 因为它可以调节IBD患者胃肠道的微生物失调。虽然目前报道的FMT在实验动物模型中总体效果良好但其应用在IBD患者的治疗中的效果由于目前实验研究数据不足还无法确定。

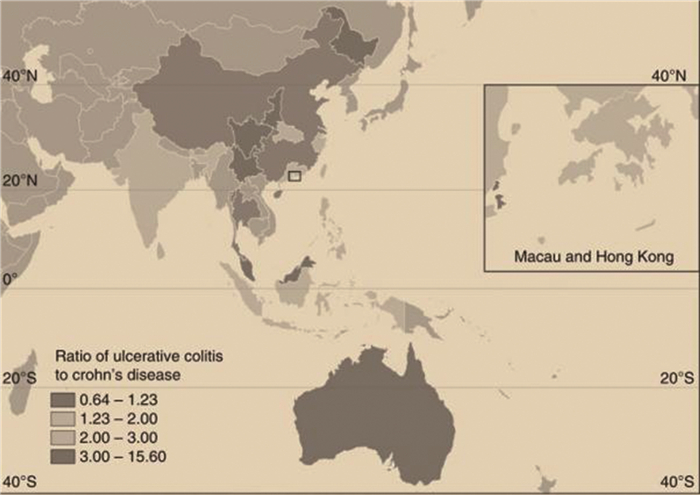

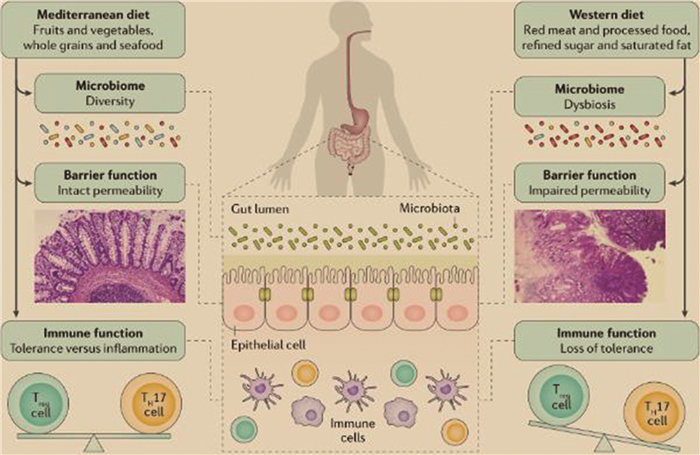

2 饮食对炎症性肠炎的影响环境因素的变化, 如卫生状况的改善, 疫苗接种, 抗生素使用频率的增加, 城市化进程加快以及口服避孕药使用的增多等被认为是导致西方国家炎症性肠炎患病率上升的重要因素, 其中饮食习惯的变化是最主要的推动力之一(图 2)。环境因素对IBD发展的最大影响可能是由于人们饮食习惯转向了以蛋白质和多不饱和脂肪酸含量高, 蔬菜, 纤维和水果占比低为特征的西方饮食。此外, 这种饮食习惯的“西化”可能会通过改变肠道微生物组成和削弱肠道上皮屏障功能从而在易感人群肠道中引发促炎环境(图 3)。发展中国家饮食习惯的“西化”使IBD在世界范围内的患病率上升。因此, 遗传因素, 环境因素尤其是饮食, 在IBD的发展中起着极其重要作用。饮食的重要性还体现在饮食对肠道菌群的组成具有深远的影响, 任何时期不论是在儿童早期甚至是生命后期, 营养成分的变化都可以促进抗炎或促炎成分的形成。除能够影响菌群组成的改变外, 饮食还可以通过许多不同的机制影响宿主的免疫力, 如增加肠道通透性, 降低结肠调节性T细胞(Regulatory T Cell, Treg)的细胞水平和促炎性标志物的增加[44-55]。

|

| 图 2 亚洲和澳大利亚19个地区溃疡性结肠炎与克罗恩病发病率的比值[47] |

|

| 图 3 饮食与IBD之间关系的潜在机制[49] |

2.1 饮食与患IBD的风险

目前还不清楚特定营养元素在IBD发展中的作用, 但是现在已经明确的是西方饮食特别是食用omega-3/omega-6(n-3/n-6)脂肪酸含量高的食物患IBD的风险更高, 在日常饮食中提高水果和蔬菜的占比可以降低患IBD的风险。这些研究在最新的《欧洲临床营养和代谢学会指南》(The European Society of Clinical Nutrition and metabolism, ESPEN)中得到支持。Llewellyn等人提出, 轻度至中度IBD患者选择低蛋白和有益纤维含量高的饮食可以改善肠屏障功能并降低微生物负荷。在实验动物模型中富含脂肪和糖的西方饮食降低了易感小鼠的肠道粘液层厚度和肠通透性, 并增加了肿瘤坏死因子α的分泌。在Shoda等人的流行病学分析中, 高动物蛋白摄入量是增加CD发生率的最强独立风险因素。这个发现最近已被针对于法国中年妇女的一项前瞻性队列研究(E3N prospective study)证实[56-62]。

2.2 IBD与营养不良患有IBD的患者患有营养不良的风险增加, IBD患者中患有营养不良的几率在6%至16%之间; 而与健康人群对照组相比, 患营养不良的风险增加了5倍。IBD引起的手术治疗史使患者营养不良的风险增加了一倍, 而在持续的临床治疗和在IBD炎症爆发期间避免食用某些种类食物的做法使患者患有营养不良风险分别增加了4倍甚至10倍。最常见的微量元素缺乏症由高到低依次是铁、维生素D、维生素B12、锌和叶酸缺乏症。微量元素缺乏的原因是多方面的, 包括进食受限, 维生素的肠溶损失, 吸收不良以及某些药物的不良作用等[63-66]。

2.3 饮食治疗方法及其在IBD中的作用目前饮食治疗IBD的主要疗法可分为消除/排除饮食和食用膳食补充剂。其中消除/排除饮食包括全胃肠外营养(Total Parenteral Nutrition, TPN), 部分肠外营养(Partial parenteral nutruition, PPN), 独家肠内营养(Exclusive Enteral Nutrition, EEN), 部分肠内营养(Partial Enteral Nutrition, PEN), 克罗恩病治疗饮食(Crohn’s Disease TREAT Diet, CD-TREAT), 克罗恩病排除饮食(Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet, CDED), 自身免疫协议饮食, IBD抗炎饮食(IBD Anti-Inflammatory Diet, IBD-AID), 特殊碳水化合物饮食(Specific Carbohydrate Diet, SCD), 半素食饮食(Semi-vegetarian diet, SVD), 低微粒饮食(Low microparticle diet), 过敏饮食, 低短链碳水化合物饮食和无乳糖饮食等。但由于缺乏有力的证据, 欧洲克罗恩病和结肠炎组织(European Crohn’s disease and colitis organization, ECCO), 美国胃肠病学协会(American Gastroenterological Association, AGA)和ESPEN指南均未建议IBD患者在缓解或活动性疾病期间食用任何特定饮食。最近发表的考科蓝(Cochrane)分析得出的结论是, 目前任何饮食干预措施对CD或UC的影响还无法确定。

尽管饮食在IBD发生中的作用机制尚不清楚, 但现有文献表明其对肠道菌群和肠道屏障功能的影响可能使某些人更易患IBD, 但没有一种食物会直接引起IBD。目前尚未有研究数据表明特定食物可以增加IBD的炎症, 但某些食物会加剧胃肠道炎症症状, 这很可能反映出肠胃过敏是慢性炎症的后遗症。现有数据表明患者最忌食的食物包括辛辣食品, 乳制品, 高脂肪食品和高纤维蔬菜等。但是, 这个结论并不适合于所有患者, 医生必须辨别可能引发或缓解症状的食物, 并因此区分出影响疾病治疗的饮食和仅缓解IBD患者症状的饮食。患者的个性化饮食必须在不牺牲足够维持人体运行的营养的情况下进行, 可以避免食用某些食物(消除饮食或排除饮食)或在饮食中添加特定营养元素[67]。

3 总结一方面, 肠道菌群失衡的副作用以及先天和适应性免疫缺陷的存在都与肠道炎症的发展有关。包括FMT在内的针对细菌的靶向疗法被认为是IBD患者治疗的最有力和最有希望的方法。另一方面, 在过去的十年中, 人们已经认识到营养不良在人类病理学中起着重要作用, 但到目前为止, 尚不清楚哪些营养因素是近期IBD患者增加的主要原因。尽管关于营养和IBD的书籍和网站不计其数, 但很少有证据支持通过限制饮食的方法干预IBD患者的治疗, 因此, 目前对IBD患者饮食的建议应围绕并鼓励以未加工食物为基础的营养均衡饮食或者补充特定营养成分。目前还存在的问题主要有细菌靶向疗法的缺乏和已有疗法可靠性的数据支撑, 以及饮食疗法的有效性评估, 研究这些问题的未来试验将大大有助于理解潜在的IBD病理机制, 并有望开发新的治疗IBD的方法。

| [1] |

ZHANG Y.Z., LI Y.Y.. Inflammatory bowel disease:pathogenesis[J]. World journal of gastroenterology, 2014, 20(1): 91-99. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.91 |

| [2] |

UNGAR B., Kopylov U. Advances in the development of new biologics in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Annals of Gastroenterology, 2016, 29(3): 243-248. |

| [3] |

MARION-LETELLIER, SAVOYE R.G., GHOSH S. IBD:In food we grust[J]. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, 2016, 10(11): 1351-1361. DOI:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw106 |

| [4] |

SCHIRBEL A., FIOCCHI C. Inflammatory bowel disease:Established and evolving considerations on its etiopathogenesis and therapy[J]. Journal of Digestive Diseases, 2010, 11(5): 266-276. DOI:10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00449.x |

| [5] |

于健春. 炎性肠病的营养支持治疗[J]. 外科理论与实践, 2014(1): 1-5. |

| [6] |

YOSHIMURA N., KAWAGUCHI T., SAKO M., et al. Su1126 in patients with crohn's disease, concomitant enteral nutrition reduces the loss of response to adalimumab maintenance therapy[J]. Gastroenterology, 2014, 146(5): 382. |

| [7] |

SOMMER., BACKHED F. The gut microbiota-masters of host development and physiology[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2013, 11(4): 227. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2974 |

| [8] |

THURSBY E., JUGE N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota[J]. Biochemical Journal, 2017, 474(11): 1823-1836. DOI:10.1042/BCJ20160510 |

| [9] |

QIN J., LI R., RAES J., et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing[J]. Nature, 2010, 464(7285): 59-65. DOI:10.1038/nature08821 |

| [10] |

LEY R.E., HAMADY M., LOZUPONE C., et al. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes[J]. Science, 2008, 320(5883): 1647-1651. DOI:10.1126/science.1155725 |

| [11] |

JANDHYALS S.M., TALUKDAR R., SUBRAMANYAM C., et al. Role of the normal gut microbiota[J]. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2015, 21(29): 8787-8803. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v21.i29.8787 |

| [12] |

MOTOWITZ M.J., CARLISLE E., ALVERDY J.C.. Contributions of intestinal bacteria to nutrition and metabolism in the critically Ill[J]. Surgical Clinics of North America, 2011, 91(4): 771-785. DOI:10.1016/j.suc.2011.05.001 |

| [13] |

BECATTINI S., TAUR Y., PAMET E.G.. Antibiotic-induced changes in the intestinal microbiota and disease[J]. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 2016, 22(6): 458-478. DOI:10.1016/j.molmed.2016.04.003 |

| [14] |

SHIRKEY T.W., SIGGETS R.H., GOLDADE B.G., et al. Effects of commensal bacteria on intestinal morphology and expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the gnotobiotic pig[J]. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 2006, 231(8): 33-45. |

| [15] |

WILLING B.P.. Enterocyte proliferation and apoptosis in the caudal small intestine is influenced by the composition of colonizing commensal bacteria in the neonatal gnotobiotic pig[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2007, 85(12): 56-66. |

| [16] |

LU L., WALKET W.A.. Pathologic and physiologic interactions of bacteria with the gastrointestinal epithelium[J]. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2001, 73(6): 1124-1130. |

| [17] |

MENNINGEN R., NOLTE K., RIJCKEN E., et al. Probiotic mixture VSL#3 protects the epithelial barrier by maintaining tight junction protein expression and preventing apoptosis in a murine model of colitis[J]. AJP Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 2009, 296(5): 40-49. |

| [18] |

PENGL., LI Z.R., GREEN R.S., et al. Butyrate enhances the intestinal barrier by facilitating tight junction assembly via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in Caco-2 cell monolayers[J]. Journal of Nutrition, 2009, 139(9): 19-25. |

| [19] |

AGGELETOPOULOU I., KONSTANTAKIS C., ASSIMAKOPOULOS S.F., et al. The role of the gut microbiota in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Microbial Pathogenesis, 2019, 137: 103774. DOI:10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103774 |

| [20] |

SHEEHAN D., MORAN C., SHANAHAN F. The microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Gastroenterol, 2015, 50(5): 495-507. |

| [21] |

LANDY J., RONDE E., ENGLISH N., et al. Tight junctions in inflammatory bowel diseases and inflammatory bowel disease associated colorectal cancer[J]. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2016, 22(11): 3117-3126. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v22.i11.3117 |

| [22] |

ZUO T., NG S.C.. The gut microbiota in the pathogenesis and therapeutics of inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9(9): 47. |

| [23] |

BTUN P., CASTAGLIUOLO I., LEO V.DI, et al. Increased intestinal permeability in obese mice:New evidence in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis[J]. AJP Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 2007, 292(2): 18-25. |

| [24] |

UNDERHILL D.M., ILIEV I.D.. The mycobiota:Interactions between commensal fungi and the host immune system[J]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2014, 14(6): 405-416. DOI:10.1038/nri3684 |

| [25] |

SARTOR R.B.. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Gastroenterology, 2008, 134(2): 577-594. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.059 |

| [26] |

KOSTIC A.D., XAVIET R.J., GEVERS D. The microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease:current status and the future ahead[J]. Gastroenterology, 2014, 146(6): 1489-1499. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.009 |

| [27] |

KNIGHTS D., LASSEN K.G., XAVIET R.J.. Advances in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis:linking host genetics and the microbiome[J]. Gut, 2013, 62(10): 1505-1510. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303954 |

| [28] |

ISSA M., ANANTHAKRISHNAN A.N., BINION D.G.. Clostridium difficile and inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 2008, 14(10): 1432-1442. DOI:10.1002/ibd.20500 |

| [29] |

LAMPS L.W., MADHUSUDHAN K.T., HAVENS J.M., et al. Pathogenic yersinia DNA is detected in bowel and mesenteric lymph nodes from patients with Crohn's disease[J]. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology, 2003, 27(2): 220-227. DOI:10.1097/00000478-200302000-00011 |

| [30] |

ROLHION N., DARFEUILLE-MICHAUD A. Adherent-invasive escherichia coli in inflammatory Bowel Disease[J]. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 2007, 13(10): 77-83. |

| [31] |

LEBLANC J.G., CHAIN F., MARTIN R., et al. Beneficial effects on host energy metabolism of short-chain fatty acids and vitamins produced by commensal and probiotic bacteria[J]. Microbial Cell Factories, 2017, 16(1): 79. |

| [32] |

CORREA-OLIVEIRA R., FACHI J.L., VIEIRA A., et al. Regulation of immune cell function by short-chain fatty acids[J]. Clinical & Translational Immunology, 2016, 5(4): 17. |

| [33] |

CHOW J., TANG H., MAZMANIAN S.K.. Pathobionts of the gastrointestinal microbiota and inflammatory disease[J]. Current Opinion in Immunology, 2011, 23(4): 473-480. DOI:10.1016/j.coi.2011.07.010 |

| [34] |

GOMES-NETO J.C., KITTANA H., MANTZ S., et al. A gut pathobiont synergizes with the microbiota to instigate inflammatory disease marked by immunoreactivity against other symbionts but not itself[J]. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7(1): 17707. |

| [35] |

KAMADA N., SEO S.U., CHEN G.Y., et al. Role of the gut microbiota in immunity and inflammatory disease[J]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2013, 13(5): 321-335. DOI:10.1038/nri3430 |

| [36] |

SOOD A., MAHAJAN R., SINGH A., et al. Role of fecal microbiota transplantation for maintenance of remission in patients with ulcerative colitis:a pilot Study[J]. Journal of Crohns & Colitis, 2019, 13(10): 11-17. |

| [37] |

GREHAN M.J., BOTODY T.J., LEIS S.M., et al. Durable alteration of the colonic microbiota by the administration of donor fecal flora[J]. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 2010, 44(8): 551-561. |

| [38] |

NOOD E., VAN VRIEZE A., NIEUWDORP M., et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent clostridium difficile[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2013, 368(5): 407-415. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1205037 |

| [39] |

MOAYYEDI P., YUAN Y., BAHARITH H., et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea:A systematic review of randomised controlled trials[J]. The Medical Journal of Australia, 2017, 207(4): 166-172. DOI:10.5694/mja17.00295 |

| [40] |

DREKONJA D., REICH J., GEZAHEGN S., et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for clostridium difficile infection:A systematic review[J]. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2015, 162(9): 630-638. DOI:10.7326/M14-2693 |

| [41] |

KHORUTS A., SADOWSKY M.J.. Understanding the mechanisms of faecal microbiota transplantation[J]. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2016, 13(9): 508-516. |

| [42] |

SURAWICZ C.M., BRANDT L.J., BINION D.G., et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of clostridium difficile infections[J]. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 2013, 108(4): 478-498. DOI:10.1038/ajg.2013.4 |

| [43] |

DEBAST S.B., BAUET M.P., KUIJPER E.J.. European society of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases:update of the treatment guidance document for clostridium difficile infection[J]. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 2014(S2): 1-26. |

| [44] |

SHAW SY, BLANCHARD JF, BERNSTEIN CN. Association between the use of antibiotics and new diagnoses of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis[J]. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 2011, 106(12): 33-42. |

| [45] |

KHALILI H, HIGUCHI LM, ANANTHAKRISHNAN AN, et al. Oral contraceptives, reproductive factors and risk of inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Gut, 2013, 62(8): 53-59. |

| [46] |

SOON IS, MOLODECKY NA, RABI DM, et al. The relationship between urban environment and the inflammatory bowel diseases:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2012, 12(1): 51. DOI:10.1186/1471-230X-12-51 |

| [47] |

NG SC, KAPLAN GG, TANG W, et al. Population density and risk of inflammatory bowel disease:A prospective population-based study in 13 countries or regions in asiapacific[J]. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 2019, 114(1): 7-15. DOI:10.1038/s41395-018-0242-1 |

| [48] |

NG SC, BERNSTEIN CN, VATN MH, et al. Geographical variability and environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Gut, 2013, 62(4): 30-49. |

| [49] |

ROGLER G, VAVRICKA S. Exposome in IBD:Recent insights in environmental factors that influence the onset and course of IBD[J]. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 2015, 21(2): 400-408. |

| [50] |

KHALILI H, CHAN SS, LOCHHEAD P, et al. The role of diet in the aetiopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2018, 15(9): 25-35. |

| [51] |

NG SC, SHI HY, HAMIDI N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century:A systematic review of population-based studies[J]. Lancet, 2018, 390(14): 69-78. |

| [52] |

ANANTHAKRISHNAN AN, BETNSTEIN CN, ILIOPOULOS D, et al. Environmental triggers in IBD:A review of progress and evidence[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018, 15(1): 39-49. |

| [53] |

DAVID LA, MAURICE CF, CARMODY RN, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome[J]. Nature, 2014, 505(7484): 559-563. DOI:10.1038/nature12820 |

| [54] |

WU GD, CHEN J, HOFFMANN C, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes[J]. Science, 2011, 334(6052): 105-108. DOI:10.1126/science.1208344 |

| [55] |

LEVINE A, SIGALL BONEH R, WINE E. Evolving role of diet in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Gut, 2018, 67(9): 1726-1738. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315866 |

| [56] |

HO NT, LI F, LEE-SARWAR KA, et al. Meta-analysis of effects of exclusive breastfeeding on infant gut mi-crobiota across populations[J]. Nature Communications, 2018, 9(1): 41-69. DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-02454-8 |

| [57] |

FORBES A, ESCHET J, HEBUTERNE X, et al. Espen guideline:clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Clinical Nutrition, 2017, 36(2): 321-347. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2016.12.027 |

| [58] |

LLEELLYN SR, BRITTON GJ, CONTIJOCH EJ, et al. Interactions between diet and the intestinal microbiota alter intestinal permeability and colitis severity in mice[J]. Gastroenterology, 2017, 154(4): 1037-1046. |

| [59] |

CASANOVA MJ, CHAPARRO M, MOLINA B, et al. Prev-alence of malnutrition and nutritional charac-teristics of patients with inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Journal of Crohn's & Colitis, 2017, 11(12): 1430-1439. |

| [60] |

MARTINEZ-MEDINA M, DENIZOT J, DREUX N, et al. Western diet induces dysbiosis with increased E coli in CEABAC10 mice, alters host barrier function favouring AIEC colonisation[J]. Gut, 2014, 63(1): 116-124. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304119 |

| [61] |

SHODA R, MATSUEDA K, YAMATO S, et al. Epidemiologic analysis of Crohn disease in Japan:Increased dietary intake of n-6 polyunsat-urated fatty acids and animal protein relates to the increased incidence of Crohn disease in Japan[J]. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1996, 63(5): 741-745. |

| [62] |

JANCTHOU P, MOTOIS S, CLAVEL-CHAPELON F, et al. Animal protein intake and risk of inflammatory bowel disease:The E3N prospective study[J]. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 2010, 105(10): 2195-2201. DOI:10.1038/ajg.2010.192 |

| [63] |

BTOTHERTON CS, MARTIO CA, LONG MD, et al. Avoidance of fiberis associated with greater risk of Crohn's disease flare in a 6-month period[J]. Clin Gastro-enterol Hepatol, 2016, 14(8): 1130-1136. DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.029 |

| [64] |

NGUYEN GC, MUNSELL M, HARRIS ML. Nation-wide prevalence and prognostic significance of clinically diagnosable protein-caloriemalnutrition in hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients[J]. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 2008, 14(8): 1105-1111. DOI:10.1002/ibd.20429 |

| [65] |

VAVRICKA SR, ROGLET G. Intestinal absorption and vitamin levels:is a new focus needed[J]. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 2012, 30(S3): 73-80. DOI:10.1159/000342609 |

| [66] |

HOLD G.L., SMITH M., GRANGE C., et al. Role of the gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis:What have we learnt in the past 10 years[J]. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2014, 20(5): 1192-1210. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v20.i5.1192 |

| [67] |

PHILLIP GU, LINDA A, FEAGINS. Dining with inflammatory bowel disease:A review of the literature on diet in the pathogenesis and management of IBD[J]. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 2020, 26(2): 181-191. |

2020, Vol. 34

2020, Vol. 34