b. Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision Liangzhou Branch, Wuwei, Gansu, P.R. China;

c. Sunan Yugu Autonomous County Deer Farm, Zhangye, Gansu, P.R. China

Grasslands cover 40% of the global land area and account for nearly 30% of the global carbon stock (Briske, 2017). Grazing is the most common use of grasslands, many of which have a long grazing history (Yu et al., 2019). Disturbances caused by climate factors and livestock activities have a complex and profound impact on both plant growth and soil carbon distribution (Vidaller et al., 2022; Shen et al., 2023). Although some studies have simulated how grazing and climate affect soil carbon sequestration, such as productivity (Mitchell et al., 2021), diversity (Lange et al., 2023), litter (Cheng et al., 2023), warming (Yan et al., 2022), there is a lack of direct practical evidence to demonstrate the synergistic effects of long-term grazing and climate factors on soil carbon. Therefore, it is necessary to elucidate the response of plant community traits under coordinated control of climate and long-term grazing and the regulatory mechanisms of soil carbon distribution based on the traits.

Climate change contributes to a net carbon sink in soil organic matter, which may result from increased productivity of grasslands (Chang et al., 2021). Climate conditions have been shown to affect plant distribution. For example, slow and sustained temperature increases broaden the spatial distribution of plant communities (Becker-Scarpitta et al., 2019), while rapid and visible increases in precipitation increase the niche complementarity of communities (Carmona et al., 2015; Du et al., 2021). In grasslands, plant community traits and carbon storage have also been affected by an increase in the number of livestock and accelerated conversion of natural land to pasture (Chang et al., 2021). Seasonal grazing is considered an effective management approach to alleviate grazing pressure and reverse the negative effects of overgrazing and is commonly used for the restoration and sustainability of alpine grasslands (Sun et al., 2020). In the non-growing season, withered vegetation diminishes selective feeding from livestock; consequently, diverse plant species are exposed to relatively consistent grazing pressure (Pauler et al., 2020). This, in turn, may affect soil carbon sequestration by influencing climate adaptation and soil nutrient acquisition strategies that determine green and growth (Zhao et al., 2019; Rawlik and Jagodziński, 2020).

Plant diversity and high litter biomass can promote soil carbon stock (Cheng et al., 2023; Lange et al., 2023), but livestock activities may reshape their effects, e.g., feeding may directly alter the dominance of grass and the biomass of litter (Yan et al., 2022); trampling and excreta return may alter soil physicochemical properties (Shen et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). Thus, changes in soil carbon may be better understood though an examination of the combined effects of plant distribution, growth and soil properties. Research has shown that grass groundcover substantially increases root biomass and significantly increases soil organic carbon (SOC), and the input of live roots is primary relative to root or stem litter in the formation of SOC (Sokol et al., 2019; Fleishman et al., 2021). Meanwhile, root morphology, rather than quality, controls the fate of root and rhizodeposition of carbon into distinct soil carbon pools (Engedal et al., 2023). Differential growth dynamics between primary and lateral roots, which comprise root systems, are crucial for plants to adapt to ever-changing environmental conditions, such as salinity, gravity and nutrient availability (Tian et al., 2014). In addition, mechanical constraints limit the elongation of roots in dry soil, which may be related to the water supply to the roots, as the root water status can affect growth pressure and root stiffness and may also be related to the asymmetric auxin in the roots during obstacle avoidance (Jin et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2020). When the growing root encounters a pore structure consisting of small pores, it makes greater contact with the surrounding soil, which results in strong rhizodeposition, which is beneficial to SOC accumulation (Lucas et al., 2023). Therefore, long-term grazing combined with climate may affect SOC distribution by influencing the growth of different root types of grass in the community.

Long-term free grazing within the paddock will form distinct gradient features for vegetation and soil properties (Manthey and Peper, 2010; Aarons et al., 2015). Specifically, the grazing pressure of livestock on vegetation varies under different gradients, the compaction effect of trampling on soil varies, and the distribution of soil nutrients varies due to excretion (Loke et al., 2021; Riesch et al., 2022). In addition, the migration of livestock between different gradients has a dispersal effect on seeds (Loke et al., 2021). Together, these factors may comprehensively affect the distribution and growth of vegetation under different gradients.

Ecosystems at high elevations are sensitive to climate change (Zhu et al., 2020). The Qilian Mountains, located in the northern part of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, are characterized by high elevation and intense climate variability (Du et al., 2021). Grazing is a common way of utilizing grassland in the Tibetan Plateau and also the most important way for herdsmen to maintain their livelihoods (Sun et al., 2024). Generally, local nomadic herders use mesh fences to divide the pasture into several parts for grazing activities in different seasons to sustainably utilize grassland resources. In this study, we selected non-growing season grazing pasture (grazing from November to April) to assess the potential regulatory effects of various root-type grasses on grassland soil carbon distribution. Our work aims to address three hypotheses: 1) Long-term grazing management practices shape vegetation structure and SOC distribution. This may be caused by variations in local environmental conditions due to grazing activities such as feeding, trampling and excreta return (Vidaller et al., 2022); 2) Changes in community biomass result from differences in the characteristics of different functional groups as well as their adaptability to climate conditions and grazing pressures. This could be caused by the overall trade-off that plants face in terms of environmental pressure, resource utilization, survival strategies, and so on (Freschet et al., 2018); 3) Climate, grazing and vegetation all influence the distribution of SOC, with vegetation being the most important factor. This prediction is based on the understanding that changes in SOC are primarily influenced by root growth and rhizosphere dynamics. The ultimate goal of our work is to elucidate the response of vegetation structure change to long-term grazing and the regulatory mechanisms underlying SOC, providing direct practical knowledge for farmers and herdsmen to jointly cope with future grazing pressures and climate disturbances.

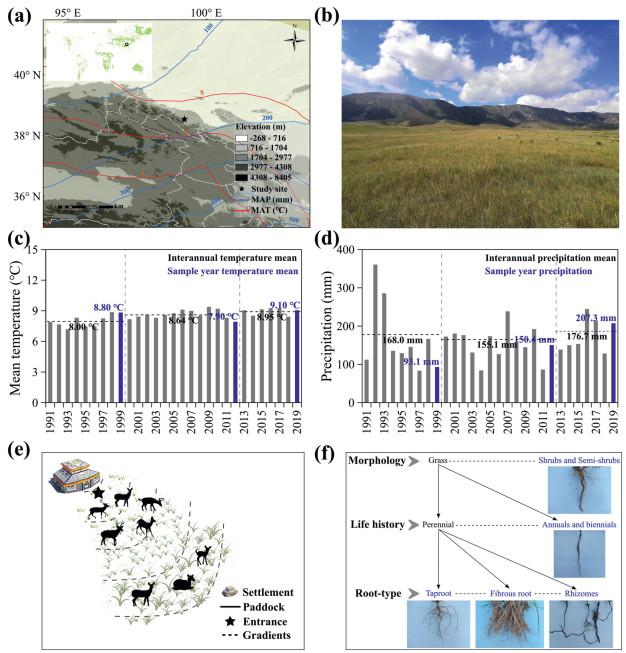

2. Materials and methods 2.1. Study siteThe study site is located in Sunan County, Gansu Province, in the Qilian Mountains, on the northeastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (99°32′ E, 38°54′ N) (Fig. 1). The elevation ranges from 2720 to 2814 m above sea level, with an average annual temperature range of 8.2 ℃ and precipitation of 170 mm (https://en.tutiempo.net/climate). The grasslands are alpine typical steppe, classified as cold temperate and slightly dry mountain grassland according to the Comprehensive and Sequential Classification system (CSCs) (Ren et al., 2008). The soil is primarily made up of gelic leptosols, according to Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD) data. Grasslands typically go through three stages: turning green in late April, peak growth in early August, and withering in early September.

|

| Fig. 1 (a) The graph depicts the distribution of total annual precipitation, mean annual temperature and elevation in the study site. (b) Photographs of the study site. (c) Mean annual temperature and (d) annual precipitation. Data are interannual mean values from 1991 to 1999, 2000–2012 and 2013–2019, respectively. (e) Experimental design. (f) Five plant classifications (annuals and biennials, perennial taproot, perennial fibrous root, perennial rhizome, shrubs and semi-shrub). Corresponding representative species are Artemisia scoparia, Torularia humilis, Stipa bungeana Trin., Potentilla bifurca Linn. and Artemisia capillaris Thunb. |

All plants in the community were classified according to their morphology, life forms and root types (https://www.zhiwutong.com/). Firstly, herbaceous plants were differentiated from shrubs (semi-shrubs) based on morphology. Herbaceous plants were then classified into annuals, biennials and perennials based on their plant life forms. Finally, perennial herbaceous plants were divided into taproot, fibrous root and rhizome plants based on root morphology. The above classification applies to all plants in the community (Fig. 1f).

2.3. Grazing experimental designThe pasture was founded in 1958, beginning with the capture of 11 wild Gansu wapiti (Cervus elaphus kansuensis) for artificial domestication, followed by self-breeding. A small number of wapiti have since been captured to supplement the herd. In 1991, the pasture was fenced off for large-scale grazing. There are approximately 200 Gansu wapiti, all of which are male. The Gansu wapiti range in age from 1 to 14 years old, although most livestock are young. Female and weak livestock have independent pastures. The same batch of Gansu wapiti is used for grazing in a seasonal rotation. The growing-season pasture is grazed from May to August each year, whereas the non-growing-season pasture is grazed from November to April. Gansu wapiti are penned at night and released during the day. Livestock graze freely in the pasture and return to their pens at night.

The number of livestock and the time of their activity is greater at the entrance of a pasture than at distances further from the entrance. Previous studies have shown that long-term grazing may have a long-term and profound impact on vegetation and soil at various distances (gradients) from the pasture entrances (Loke et al., 2021). To test whether grasslands farther away from the entrance are relatively less affected by livestock, we collected samples at the entrance (gradient 0) and every 0.3 km thereafter, i.e., 0.3, 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 km from the entrance. In 1999, our team conducted the first sampling, which was marked with stones. The marked points were rediscovered and sampled in 2012 and 2019, allowing us to assess the impact of long-term grazing without interference from pasture heterogeneity.

2.4. Vegetation and soil samplingAt each gradient marker (i.e., entrance, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 km), the number of plant species were noted in each of three representative quadrats (100 cm × 100 cm). All quadrats were established in gradients representative of the vegetation and microtopography found, allowing the effects of grazing pressure to be assessed at gradients without confounding factors caused by differences in soil type or vegetation (Eldridge et al., 2024). Above-ground biomass was harvested, separated into species and oven-dried at 65 ℃ to a constant weight. After the vegetation was harvested, two soil core samples were collected in each quadrat and sampled to a depth of 40 cm in 10 cm increments before being combined into a single sample for each layer of soil to measure soil chemical properties. The samples were air-dried, sieved through a 2-mm mesh to ensure uniformity, and stored at room temperature until analysis (Zhang et al., 2022, 2023b). The organic carbon content in the soil (SOCc) was determined by the potassium dichromate oxidation spectrophotometric method (Nelson and Sommer, 1983). We used a shovel to dig a pit inside the quadrat, repaired one side to make it flat, and measured soil bulk density (SBD, g·cm−3) with a stainless-steel cutting ring.

2.5. Calculations and statistical analysisSoil organic carbon stock (SOCs) was calculated as follows:

| \begin{aligned} S O C s=S O C c \times S B D \times H \times 10^{-2} \end{aligned} | (1) |

where H is the soil sampling depth (cm).

To assess the effects of grazing gradients on plant species and root-type grass biomass under different years, two-factor analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted in SPSS software (v.17.0). The correlation and random forest models were used to investigate the effect and magnitude of climate and grazing factors on species richness and root-type grass biomass, which were performed using the R packages ‘psych’ and ‘randomForest’, respectively (Revelle, 2023; Liaw and Wiener, 2002). The linear mixed-effects model (LMM) was used to investigate the effects of species richness and root-type grass biomass on SOCc and SOCs over varying grazing times. LMM were performed using the R package ‘nlme’ (Pinheiro et al., 2016). The effect size of each tested variable was determined as marginal R2 using the R package “MuMIn” (Bartoń, 2013). To quantify the pure and shared contributions of climate factors, grazing years, grazing gradients, species distribution and root-type grass biomass on SOCc and SOCs, variation partitioning analysis was performed using the R package ‘rdacca.hp’ (Lai et al., 2022). Partial least squares path modeling (PLSPM) was used to investigate the regulatory pathways of soil carbon content and stock in response to climate factors, grazing years, grazing gradients, species richness and community biomass. When the sample size is small, PLSPM outperforms other structural equation modeling methods; typically, 30–100 samples are sufficient. PLSPM was performed using the R package ‘plspm’ (Tenenhaus et al., 2005). Random forest modeling was used to rank the effect of all variables on the SOC distribution, including climate, grazing, and vegetation factors, using the R package ‘rfPermute’ (Archer, 2023), and establish the optimal prediction model for SOC distribution using stepwise linear regression in SPSS software. All data were tested for normality and variance homogeneity. Logarithmic transformation was used as needed. We used R v.4.3.2.

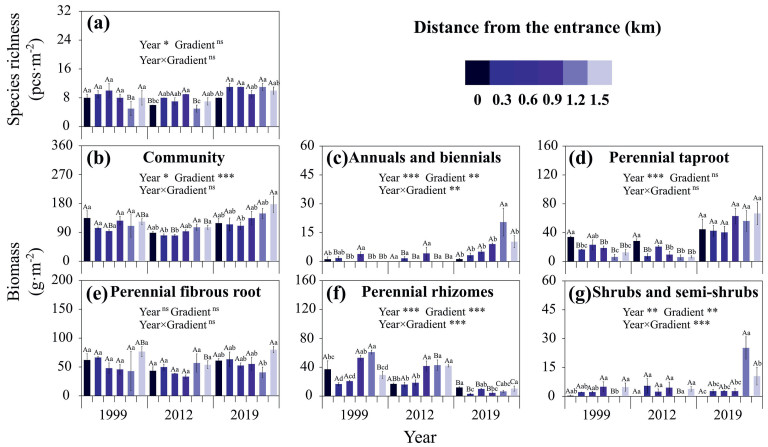

3. Results 3.1. The effect of climate and grazing on vegetationGrazing significantly affects species richness and grass biomass in different years, except for perennial fibrous root grass (Fig. 2). The biomass of annual and biennial grass and perennial taproot grass increased, whereas perennial rhizome grass biomass decreased (Fig. 2c, d and f).

|

| Fig. 2 Species richness (a) and biomass of root-type grasses (b, c, d, e, f and g) varied with grazing gradients and years. Lowercase and capital letters show significant differences across grazing gradients and years, according to Duncan's test at P < 0.05. Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed significant effects of year and gradient on vegetation structure (∗∗∗, P < 0.001; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗, P < 0.05; ns, P > 0.05). |

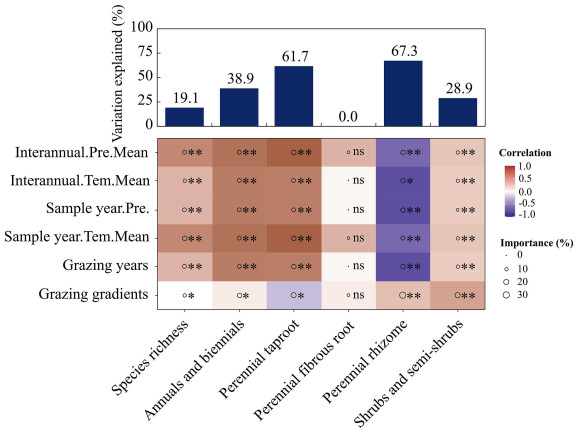

Climate and grazing factors significantly impacted species richness, the biomass of annual and biennial grasses, perennial rhizome grasses, shrubs and semi-shrubs; the effect of these factors on perennial fibrous root grass was minimal (Fig. 3). Climate factors and grazing years are strongly, positively correlated with species richness as well as the biomass of annual, biennial, and perennial taproot grasses. These factors were weakly correlated with the biomass of perennial fibrous root grasses, shrubs and semi-shrubs. Climate factors and grazing years were also strongly, negatively correlated with the biomass of perennial rhizome grasses. Grazing gradients were weakly correlated with species richness, as well as the biomass of annual, biennial and perennial fibrous root grass, but strongly correlated with the biomass of perennial taproots, perennial rhizome grass, shrub and semi-shrubs.

|

| Fig. 3 Correlation analysis and a random forest model demonstrate correlation and interpretability between plant traits and environmental factors. The heat map represents the Spearman correlation, with darker colors indicating a stronger correlation. The hollow circle represents the importance of each variable to the dependent variable, while the ∗ indicates a significant effect (∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ns, P > 0.05). The bar chart depicts the variation in species richness and root-type grass biomass caused by climate and grazing. Interannual.Pre.Mean (Interannual precipitation mean), Interannual.Tem.Mean (Interannual temperature mean), Sample year.Pre (Sample year precipitation) and Sample year.Tem.Mean (Sample year temperature mean). The grazing year denotes the length of continuous grazing, which is 8 years (1991–1999), 21 years (1991–2012) and 28 years (1991–2019), respectively. |

Species richness, as well as annual, biennial, and perennial fibrous root grasses, has positive effects on SOCc and SOCs, whereas shrubs and semi-shrubs have negative effects. Increased grazing time increased species richness, as well as the effect of annual, biennial, shrub and semi-shrubs on SOCc and SOCs, whereas the overall impact of perennial grass remained stable. Overall, root-type grass has a greater effect on SOC on the surface than on the bottom layer (Fig. 4).

|

| Fig. 4 Linear mixed-effects models explain variation in soil organic carbon (SOC) content and stock based on species richness and root-type grass biomass. The effect of variables on SOC was calculated over three grazing periods: 7 years (2013–2019), 13 years (2000–2012) and 20 years (2000–2019). The circle size indicates the R2 of significant plant effects (plant species richness and biomass of annuals and biennials, perennial taproot, perennial fibrous root grass, perennial rhizome, shrubs and semi-shrubs; α = 0.05) on SOC. Positive effects are shown in red, while negative effects are shown in blue. |

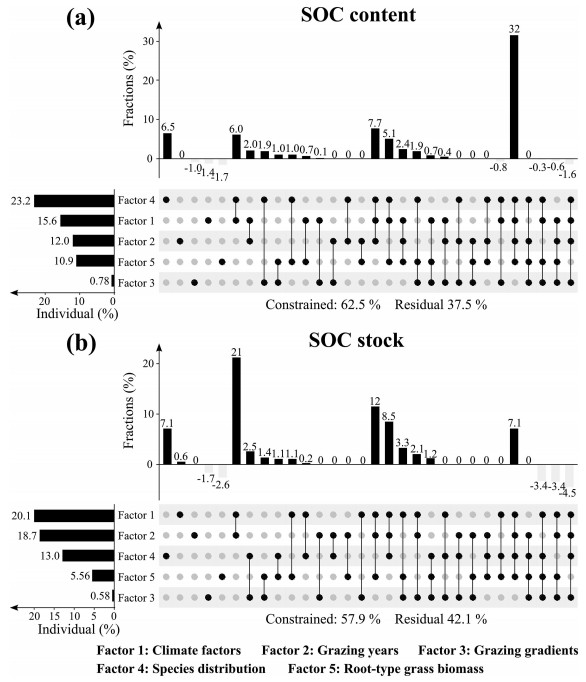

SOC content variation can best be explained by the interaction of climate factors, grazing years, species distribution and root-type grass biomass (32%) (Fig. 5a), with species distribution (23.2%) individually explaining the greatest amount of variation in SOC content. SOC stock variation is best explained by the interaction between climate factors and grazing years (21%) (Fig. 5b), with climate factors (20.1%) and grazing years (18.7%) having roughly the same explanatory power individually.

|

| Fig. 5 Variation partitioning shows the individual and shared contributions of climate factors, grazing years, grazing gradients, species distribution and root-type grass biomass on soil organic carbon (SOC) content (a) and SOC stock (b). Climate factors include temperature and precipitation mean values of interannual and sampled years; the grazing year denotes the length of continuous grazing, which is 8 years (1991–1999), 21 years (1991–2012) and 28 years (1991–2019), respectively. The species distribution is a matrix representing the number of species in the sample plot. The root-type grass biomass represents the biomass of the various classified plants in the sample plot. The numbers in the graphs are the percentage of variance explained by the corresponding factors. The dot matrix and the corresponding bar above it show the values of shared and individual contributions. Negative values due to the adjustment of R2 mean negligible contributions and are not shown in the graph, but they are included in the computation of the total contribution of each variable category which is shown on the edge of the dot matrix. Residuals represent the percentage unexplained by these variables. |

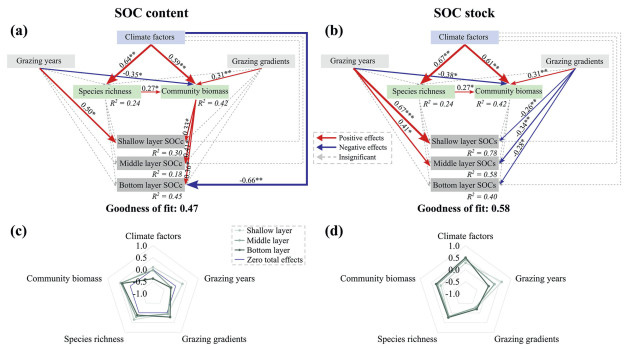

Partial least squares path modeling indicates that climate factors have a direct negative effect on SOCc in the bottom layer but a direct positive effect on species richness and community biomass. Our analysis also indicates that community biomass has a positive effect on SOCc throughout the soil layer (Fig. 6a). Climate factors only have a direct positive impact on species richness and community biomass (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, in both models, grazing years have a direct positive effect on SOCc and SOCs in the shallow layer but a direct negative effect on community biomass (Fig. 6a and b). These models also indicate that grazing gradients have a direct positive effect on community biomass and a direct negative effect on the whole layer's SOCs. According to our models, the total effect of climate factors and grazing years on SOCc and SOCs is relatively high, respectively. The total effect of species richness and community biomass on the shallow layer's SOCc is significant (Fig. 6c and d).

|

| Fig. 6 Partial least squares path modeling (PLSPM) for the impact path of climate factors, grazing years, grazing gradients, species richness and community biomass on soil organic carbon (SOC) content and stock (a and b). Climate factors include temperature and precipitation mean values of interannual and sampled years; the grazing year denotes the length of continuous grazing, which is 8 years (1991–1999), 21 years (1991–2012) and 28 years (1991–2019), respectively; community biomass represents the biomass of the various classified plants in the sample plot; the shallow, middle and bottom layers of SOC content or stock are 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm and 20–40 cm (a collection of 20–30 cm and 30–40 cm), respectively. Red arrows indicate positive effects, blue arrows indicate negative effects, gray arrows indicate no significant effect, and numbers on the arrows indicate the direct effect size and significance levels (∗∗∗, P < 0.001; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗, P < 0.05). The radar chart depicts the total effect of variables on SOC content and stock (c and d) in various soil layers. |

Our random forest model indicates that climate factors have little effect on SOCc and SOCs, whereas grazing gradients and root-type grass biomass have a significant effect. The grazing gradient has the greatest effect on SOCs in the 0–10 cm soil layer, and the grazing year has the smallest effect on SOCc (Fig. 7).

|

| Fig. 7 The random forest model estimates the contribution of all environmental factors to soil organic carbon (SOC) content (a, b, c and d) and stock (e, f, g and h) in various soil layers. The dark color bars indicate significance (∗, P < 0.05), and the light color bars indicate no significant difference (ns, P > 0.05). Interannual.Pre.Mean (Interannual precipitation mean), Interannual.Tem.Mean (Interannual temperature mean), Sample year.Pre (Sample year precipitation) and Sample year.Tem.Mean (Sample year temperature mean). The grazing year denotes the length of continuous grazing, which is 8 years (1991–1999), 21 years (1991–2012) and 28 years (1991–2019), respectively. |

A stepwise linear regression model was run on SOCc and SOCs using all variables. These models indicate that perennial fibrous grass has a high predictive ability for SOCc in the 0–30 cm soil layer. Perennial rhizome grass and perennial taproot grass are good predictors of SOCs (Table 1).

| Index | Soil layer (cm) | Model | R2 | P |

| SOC content (g·kg−1) | 0–10 | y = Annuals and biennials × 0.221 + Perennial fibrous root × 0.049 + 23.7 | 0.24 | 0.001 |

| 10–20 | y = Perennial fibrous root × 0.057 + 20.5 | 0.11 | 0.014 | |

| 20–30 | y = Perennial fibrous root × 0.059 - Sample year.Pre. × 0.027 + 21.4 | 0.25 | 0.001 | |

| 30–40 | y = Grazing gradients × 1.846 - Sample year.Pre. × 0.053 + 24.0 | 0.43 | 0.000 | |

| SOC stock (kg·m−2) | 0–10 | y = Sample year.Pre. × 0.015 - Perennial rhizome × 0.014 - Grazing gradients × 0.340 + 1.61 | 0.78 | 0.000 |

| 10–20 | y = Sample year.Pre. × 0.007 + Perennial taproot × 0.012 - Grazing gradients × 0.392 + 1.73 | 0.56 | 0.000 | |

| 20–30 | y = Community biomass × 0.006 - Perennial rhizome × 0.021 + 2.31 | 0.47 | 0.000 | |

| 30–40 | y = Perennial taproot × 0.009 + 1.82 | 0.15 | 0.005 |

Grazing had a significant effect on species richness and biomass of root-type grass in different years, with the exception of perennial fibrous root grass. Specifically, grazing increased annual and biennial grass, and perennial taproot grass, but decreased the biomass of perennial rhizome grass (Fig. 2). This may be related to differences in adaptability of root-type grasses to the same external environment (Herben et al., 2022; Engedal et al., 2023). Annual and biennial grasses typically have strong phenotypic plasticity to cope with environmental changes (Dovrat et al., 2019; Rudak et al., 2019). In recent years (2013–2019) and sampling years (2019), the average annual temperature and total annual precipitation have been relatively high (Fig. 1), resulting in a less stressful living environment, which promotes growth and reproduction of annual and biennial grasses. Perennial fibrous root grass typically reproduces asexually through tillering and sexually through seeds. At the same time, higher root density in the surface soil ensures that they have stronger soil nutrient and water acquisition capabilities (Zhao et al., 2019; Pérez-Ramos et al., 2019), strengthening their adaptability in high-elevation grassland ecosystems with limited resources and long-term grazing pressure (Jäschke et al., 2020), which may enable them to steadily endure long-term grazing pressure. Perennial taproot grasses typically have one or more thick and straight main roots. Each year many new lateral roots grow on these main roots, reducing the overall investment in the root system and improving the root system's ability to absorb nutrients and water. Furthermore, perennial taproot grasses typically produce a large number of seeds, which promotes their reproduction and spread (Benard and Toft, 2007). Perennial rhizome grasses, in contrast, may respond to environmental changes differently due to dynamic bud bank changes (Ott et al., 2019). Long-term grazing leads to soil compaction from livestock trampling, increased soil bulk density, and decreased macropores (Romero-Ruiz et al., 2023; Döbert et al., 2021). Changes in soil physical structure may directly inhibit the growth of rhizomatous grasses (Jin et al., 2013), resulting in a decrease in community biomass.

Annual and biennial grass, perennial taproot grass and perennial rhizome grass are more sensitive to climate and grazing time, making them more easily manipulated by environmental variables in vegetation communities, whereas perennial fibrous root grass may be primarily determined by species-specific architectural blueprints (Herben et al., 2022). Grazing gradient is weakly correlated with the biomass of perennial fibrous grasses. Unsurprisingly, grazing gradient provides little explanation for variation in the biomass of these grasses. However, grazing gradient is strongly correlated with, and can explain much of the variance in, the biomass of annual, biennial, perennial taproots, perennial rhizome grass shrubs, and semi-shrubs. This finding indicates that grazing gradients within a pasture have a small effect on species that rely on tillering for reproduction but a large effect on species that rely on seeds, nutrients absorbed by root systems for growth or rhizome reproduction. This could be due to differences in how different species adapt to environmental stress (Zhao et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022b).

4.2. The effect of vegetation composition on SOC distributionHigher plant diversity under grazing conditions typically leads to increased community productivity, moreover, plants have been shown to withstand grazing pressure by increasing root investment (Wilson et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2023b). Root growth allows for an increase in SOC. Annual and biennial plants have strong resource acquisition capabilities and can rapidly form aboveground and underground carbon pools, which have greater potential benefits for SOC (Dovrat et al., 2019). Shrubs and semi-shrubs rely on deep and extensive root systems to absorb the nutrients required for reproduction (Wang et al., 2022a). Our finding that species richness, annual and biennial grasses and semi-shrubs all have a significant impact on SOC is consistent with these studies.

We found that the effect of species richness and vegetation composition on SOC gradually increases with grazing time, which could be due to the accelerated material cycling process of annual and biennial plants during the growing season, which speeds up the flow of photosynthetic products to soil carbon. Shrubs and semi-shrubs produce a significant amount of dry matter each year, which affects soil carbon via withered branches and fallen leaves (Sokol et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023a). Notably, we found that the overall effect of annual and biennial grasses on SOC was positive, whereas that of shrubs and semi-shrubs was negative. One explanation for this is that long-term cold-season grazing significantly reduces litter return and cannot increase soil carbon. We also found that perennial herbaceous plants have a relatively stable effect on SOC, likely because these plants must constantly balance their growth and reproduction while maintaining a certain level of resource acquisition ability and dry matter accumulation.

4.3. Mechanisms that regulate the distribution of SOCSOCc is typically associated with the type and growth of plant roots (Engedal et al., 2023; Sokol et al., 2019). Our analysis indicated that the interaction of multiple variables explains the greatest change in SOCc (Fig. 5). This is consistent with the fact that plant roots and SOCc are directly influenced by climate factors such as precipitation and temperature, livestock activities such as grazing and trampling and species distribution. The SOCs is determined by the SOCc and density. Long-term grazing can have a significant effect on soil physical and chemical properties via excreta return and trampling, affecting SOCs (Wilson et al., 2018).

Higher temperatures and precipitation can allow more species to survive, increasing species richness, niche complementarity and biomass (Carmona et al., 2015), as well as contributing to an increase in SOCc. We found that grazing years and near-gradient grazing have a significant negative effect on community biomass, whereas they have a significant positive effect on the shallow layer's SOC (Fig. 6a and b). This may be because livestock grazing reduces aboveground biomass, whereas plants invest more photosynthetic products into their roots to deal with grazing disturbances (Larreguy et al., 2014). In addition, research has shown that livestock excrement is returned and trampled on, and bedding compaction contributes to an increase in SOCs (Wilson et al., 2018). This bedding compaction may explain why we found that community biomass and species richness had a higher total effect on the SOCc of the shallow layer and why grazing years had a higher total effect on SOCs.

It is worth noting that temperature can increase SOCc by encouraging root growth into deeper layers (Wu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024). Long-term grazing may result in shallow root growth, whereas deep soil lacks more carbon input and microbial activity continuously consumes carbon, lowering SOC (Zhu et al., 2021). As a result, the mechanisms underlying changes in SOC may involve a trade-off between climate and grazing effects. However, our models show that climate factors have a direct negative effect on the bottom layer's SOCc (Fig. 6a), implying that grazing-induced SOCc changes have a greater impact than climate. Plants have been shown to adapt to long-term grazing pressure by increasing the root-to-shoot ratio, which increases SOC (Guo et al., 2021). Livestock trampling and resting cause soil compaction, which increases soil density and thus SOCs (Wilson et al., 2018). Thus, the mechanisms that regulate SOCs fluctuations may involve a trade-off between root investment and livestock activity. However, our models show that the vegetation layer has no effect on SOCs, and the grazing gradient has a negative effect (Fig. 6b), implying that the effect of grazing-induced SOC changes is greater than that of the vegetation layer.

4.4. Ranking and predicting the effect of all variables on SOCOur results indicate that the effect of climate factors on SOCc is relatively small, whereas the effect of the vegetation layer is significant. The biomass of annual and biennial grass, community, and perennial rhizome grass has the greatest effect on SOCc in the 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm and 20–40 cm soil layers, respectively (Fig. 7). This is because annual and biennial grasses require complete lifecycles with limited resources, and the most direct strategy is to increase investment in the root system, resulting in shallower root distribution, higher root density, smaller root diameter, increased contact area with soil, promoting root carbon deposition and increased SOC (Dovrat et al., 2019; Lucas et al., 2023). The community's root system is mostly concentrated within 20 cm; consequently, community biomass has the greatest influence on the 10–20 cm SOC. The perennial rhizome grass spreads via underground rhizome structures, and the large number of active roots retained in the soil can directly reduce soil density and SOCs (Wang et al., 2022b). Furthermore, the influence of plant roots on soil particle and pore arrangement has a direct effect on vertical water flow and carbon migration, changing the vertical distribution of carbon in the soil layer (Souza et al., 2023). As the rhizome grows, root carbon deposition promotes an increase in SOCc, while a large amount of root exudates promotes microorganism growth and reproduction, increasing soil organic matter consumption (Min et al., 2021). Thus, their interaction may eventually lead to changes in SOCc.

We found that grazing gradients have the greatest effect on SOCs, followed by perennial taproots and rhizome grasses (Fig. 7). This is primarily because long-term specific grazing activities shape vegetation landscapes along different gradients. At the same time, taproot grass and rhizome grass can affect soil density by compressing soil space and SOCc by interacting with microorganisms, resulting in a significant effect on SOCs (Min et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022b).

5. ConclusionsThis study used multiple datasets from different sampling years under long-term grazing conditions to create a new comprehensive plant classification system based on plant morphology, life forms and root type. We examined how grazing management affects vegetation community composition and the mechanisms that drive SOC distribution based on vegetation. We discovered that different types of population biomass respond differently to long-term grazing and have different effects on SOC distribution, which may be due to differences in nutrient acquisition abilities and reproductive pathways. Our analysis reveals that the interaction of multiple factors accounts for the greatest change in SOC content, whereas the interaction of climate factors and grazing years accounts for the greatest change in SOC stock. Further investigation revealed that climate and grazing can further affect SOC content through vegetation layers, while SOC stock is dominated by grazing. A thorough comparison revealed that grazing gradients and root-type grass biomass have a significant effect on SOC content and stock, with little effect from climate factors. Finally, the results clearly indicate that it is possible to achieve more precise regulation of SOC distribution managing root types, especially in the restoration, maintenance and enhancement of grassland diversity and productivity through grazing management, grassland replanting, fertilization and other operations. This may also further enhance the soil carbon sequestration potential of natural grasslands, which has important theoretical and practical value.

AcknowledgementsThis research was funded by the China National Natural Science Foundation (32161143028), National Science and Technology Assistance (KY202002011) and the Innovative Research Team of the Ministry of Education (IRT_17R50).

Data availability

Data are available from corresponding author upon request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yu-Wen Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ze-Chen Peng: Investigation. Sheng-Hua Chang: Investigation. Zhao-Feng Wang: Investigation. Lan Li: Investigation. Duo-Cai Li: Investigation. Yu-Feng An: Investigation. Fu-Jiang Hou: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ji-Zhou Ren: Methodology, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Archer, E., 2023. rfPermute: estimate permutation p-values for random forest ImportanceMetrics. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rfPermute.

|

Aarons, S.R., Gourley, C.J.P., Hannah, M.C., et al., 2015. Between and within paddock soil chemical variability and forage production gradients in grazed dairy pastures. Nutr. Cycling Agroecosyst., 102: 411-430. DOI:10.1007/s10705-015-9714-5 |

Bartoń, K., 2013. MuMIn: multi-model inference. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn.

|

Becker-Scarpitta, A., Vissault, S., Vellend, M., et al., 2019. Four decades of plant community change along a continental gradient of warming. Global Change Biol., 25: 1629-1641. DOI:10.1111/gcb.14568 |

Benard, R.B., Toft, C.A., 2007. Effect of seed size on seedling performance in a long-lived desert perennial shrub (Ericameria nauseosa: Asteraceae). Int. J. Plant Sci., 168: 1027-1033. DOI:10.1086/518942 |

Briske, D.D., 2017. Rangeland systems: Foundation for a conceptual framework. In: Briske, D. (Ed.), Rangeland Systems: Processes, Management, and Challenges. Springer International Publishing, pp. 131-168.

|

Carmona, C.P., Mason, N.W.H., Azcárate, F.M., et al., 2015. Inter-annual fluctuations in rainfall shift the functional structure of Mediterranean grasslands across gradients of productivity and disturbance. J. Veg. Sci., 26: 538-551. DOI:10.1111/jvs.12260 |

Chang, J.F., Ciais, P., Gasser, T., et al., 2021. Climate warming from managed grasslands cancels the cooling effect of carbon sinks in sparsely grazed and natural grasslands. Nat. Commun., 12: 118. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-20406-7 |

Cheng, X.R., Xing, W.L., Liu, J.W., 2023. Litter chemical traits, microbial and soil stoichiometry regulate organic carbon accrual of particulate and mineral-associated organic matter. Biol. Fertil. Soils, 59: 777-790. DOI:10.1007/s00374-023-01746-0 |

Döbert, T.F., Bork, E.W., Apfelbaum, S., et al., 2021. Adaptive multi-paddock grazing improves water infiltration in Canadian grassland soils. Geoderma, 401: 115314. DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115314 |

Dovrat, G., Meron, E., Shachak, M., et al., 2019. Plant size is related to biomass partitioning and stress resistance in water-limited annual plant communities. J. Arid Environ., 165: 1-9. DOI:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2019.04.006 |

Du, J., He, Z.B., Chen, L.F., et al., 2021. Impact of climate change on alpine plant community in Qilian Mountains of China. Int. J. Biometeorol., 65: 1849-1858. DOI:10.1007/s00484-021-02141-w |

Eldridge, D.J., Ding, J., Dorrough, J., et al., 2024. Hotspots of biogeochemical activity linked to aridity and plant traits across global drylands. Nat. Plants, 10: 760-770. DOI:10.1038/s41477-024-01670-7 |

Engedal, T., Magid, J., Hansen, V., et al., 2023. Cover crop root morphology rather than quality controls the fate of root and rhizodeposition C into distinct soil C pools. Global Change Biol., 29: 5677-5690. DOI:10.1111/gcb.16870 |

Fleishman, S.M., Bock, H.W., Eissenstat, D.M., et al., 2021. Undervine groundcover substantially increases shallow but not deep soil carbon in a temperate vineyard. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 313: 107362. DOI:10.1016/j.agee.2021.107362 |

Freschet, G.T., Violle, C., Bourget, M.Y., et al., 2018. Allocation, morphology, physiology, architecture: the multiple facets of plant above-and below-ground responses to resource stress. New Phytol., 219: 1338-1352. DOI:10.1111/nph.15225 |

Guo, F.H., Li, X.L., Yin, J.J., et al., 2021. Grazing-induced legacy effects enhance plant adaption to drought by larger root allocation plasticity. J. Plant Ecol., 14: 1024-1029. DOI:10.1093/jpe/rtab056 |

Herben, T., Šašek, J., Balšánková, T., et al., 2022. The shape of root systems in a mountain meadow: plastic responses or species-specific architectural blueprints?. New Phytol., 235: 2223-2236. DOI:10.1111/nph.18132 |

Jäschke, Y., Heberling, G., Wesche, K., 2020. Environmental controls override grazing effects on plant functional traits in Tibetan rangelands. Funct. Ecol., 34: 747-760. DOI:10.1111/1365-2435.13492 |

Jin, K.M., Shen, J.B., Ashton, R.W., et al., 2013. How do roots elongate in a structured soil?. J. Exp. Bot., 64: 4761-4777. DOI:10.1093/jxb/ert286 |

Lange, M., Eisenhauer, N., Chen, H.M., et al., 2023. Increased soil carbon storage through plant diversity strengthens with time and extends into the subsoil. Global Change Biol., 29: 2627-2639. DOI:10.1111/gcb.16641 |

Lai, J.S., Zou, Y., Zhang, J.L., et al., 2022. Generalizing hierarchical and variation partitioning in multiple regression and canonical analyses using the rdacca.hp R package. Methods Ecol. Evol., 13: 782-788. DOI:10.1111/2041-210x.13800 |

Larreguy, C., Carrera, A.L., Bertiller, M.B., 2014. Effects of long-term grazing disturbance on the belowground storage of organic carbon in the Patagonian Monte, Argentina. J. Environ. Manag., 134: 47-55. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.12.024 |

Lee, H.J., Kim, H.S., Park, J.M., et al., 2020. PIN-mediated polar auxin transport facilitates root−obstacle avoidance. New Phytol., 225: 1285-1296. DOI:10.1111/nph.16076 |

Liaw, A., Wiener, M., 2002. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News, 2: 18-22. http://CRAN.R-project.org/doc/Rnews/. |

Loke, P.F., Kotzé, E., Preez, C.C.D., et al., 2021. Cross-rangeland comparisons on soil carbon dynamics in the pedoderm of semi-arid and arid South African commercial farms. Geoderma, 381: 114689. DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2020.114689 |

Lucas, M., Gil, J., Robertson, G.P., et al., 2023. Changes in soil pore structure generated by the root systems of maize, sorghum and switchgrass affect in situ N2O emissions and bacterial denitrification. Biol. Fertil. Soils. DOI:10.1007/s00374-023-01761-1 |

Manthey, M., Peper, J., 2010. Estimation of grazing intensity along grazing gradients–the bias of nonlinearity. J. Arid Environ., 74: 1351-1354. DOI:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.05.007 |

Min, K., Slessarev, E., Kan, M., et al., 2021. Active microbial biomass decreases, but microbial growth potential remains similar across soil depth profiles under deeply-vs. shallow-rooted plants. Soil Biol. Biochem., 162: 108401. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108401 |

Mitchell, E., Scheer, C., Rowlings, D., et al., 2021. Important constraints on soil organic carbon formation efficiency in subtropical and tropical grasslands. Global Change Biol., 27: 5383-5391. DOI:10.1111/gcb.15807 |

Nelson, D.W., Sommer, L.E., 1983. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In: Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., Keeney, D.R. (Eds.), Methods of Soil Analysis. American Society of Agronomy and Soil Science Society of American, Madison, pp. 1-129.

|

Ott, J.P., Klimešová, J., Hartnett, D.C., 2019. The ecology and significance of below-ground bud banks in plants. Ann. Bot., 123: 1099-1118. DOI:10.1093/aob/mcz051 |

Pauler, C.M., Isselstein, J., Suter, M., et al., 2020. Choosy grazers: influence of plant traits on forage selection by three cattle breeds. Funct. Ecol., 34: 980-992. DOI:10.1111/1365-2435.13542 |

Pérez-Ramos, I.M., Matías, L., Gómez-Aparicio, L., et al., 2019. Functional traits and phenotypic plasticity modulate species coexistence across contrasting climatic conditions. Nat. Commun., 10: 2555. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-10453-0 |

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S., et al., 2016. Nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme.

|

Rawlik, M., Jagodziński, A.M., 2020. Seasonal dynamics of shoot biomass of dominant clonal herb species in an oak–hornbeam forest herb layer. Plant Ecol., 221: 1133-1142. DOI:10.1007/s11258-020-01067-4 |

Ren, J.Z., Hu, Z.Z., Zhao, J., et al., 2008. A grassland classification system and its application in China. Rangel. J., 30: 199-209. DOI:10.1071/RJ08002 |

Revelle, W., 2023. Psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. https://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=psych.

|

Riesch, F., Wichelhaus, A., Tonn, B., et al., 2022. Grazing by wild red deer can mitigate nutrient enrichment in protected semi-natural open habitats. Oecologia, 199: 471-485. DOI:10.1007/s00442-022-05182-z |

Romero-Ruiz, A., Monaghan, R., Milne, A., et al., 2023. Modelling changes in soil structure caused by livestock treading. Geoderma, 431: 116331. DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116331 |

Rudak, A., Wódkiewicz, M., Znój, A., et al., 2019. Plastic biomass allocation as a trait increasing the invasiveness of annual bluegrass (Poa annua L.) in Antarctica. Polar Biol., 42: 149-157. DOI:10.1007/s00300-018-2409-z |

Shen, Y.Y., Fang, Y.Y., Chen, H., et al., 2023. New insights into the relationships between livestock grazing behaviors and soil organic carbon stock in an alpine grassland. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 355: 108602. DOI:10.1016/j.agee.2023.108602 |

Sokol, N.W., Kuebbing, S.E., Karlsen-Ayala, E., et al., 2019. Evidence for the primacy of living root inputs, not root or shoot litter, in forming soil organic carbon. New Phytol., 221: 233-246. DOI:10.1111/nph.15361 |

Souza, L.F., Hirmas, D.R., Sullivan, P.L., et al., 2023. Root distributions, precipitation, and soil structure converge to govern soil organic carbon depth distributions. Geoderma, 437: 116569. DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116569 |

Sun, J., Liu, M., Fu, B., et al., 2020. Reconsidering the efficiency of grazing exclusion using fences on the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Bull., 65: 1405-1414. DOI:10.1016/j.scib.2020.04.035 |

Sun, J., Wang, Y., Lee, T.M., et al., 2024. Nature-based Solutions can help restore degraded grasslands and increase carbon sequestration in the Tibetan Plateau. Commun. Earth Environ., 5: 154. DOI:10.1038/s43247-024-01330-w |

Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V.E., Chatelin, Y.M., et al., 2005. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal., 48: 159-205. DOI:10.1016/j.csda.2004.03.005 |

Tian, H.Y., De Smet, I.D., Ding, Z.J., 2014. Shaping a root system: regulating lateral versus primary root growth. Trends Plant Sci., 19: 426-431. DOI:10.1016/j.tplants.2014.01.007 |

Vidaller, C., Malik, C., Dutoit, T., et al., 2022. Grazing intensity gradient inherited from traditional herding still explains Mediterranean grassland characteristics despite current land-use changes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 338: 108085. DOI:10.1016/j.agee.2022.108085 |

Wang, D.B., Ding, W.Q., 2024. Grazing led to an increase in the root: shoot ratio and a shallow root system in an alpine meadow of the Tibetan Plateau. Front. Environ. Sci., 12: 1348220. DOI:10.3389/fenvs.2024.1348220 |

Wang, L., Jing, Y.Y., Xu, C.L., et al., 2022a. Effect of grazing treatments on phenotypic and reproductive plasticity of Kobresia humilis in alpine meadows of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Front. Environ. Sci., 10: 903763. DOI:10.3389/fenvs.2022.903763 |

Wang, J.Y., Xu, T.T., Feng, X.Y., et al., 2022b. Simulated grazing and nitrogen addition facilitate spatial expansion of Leymus chinensis clones into saline-alkali soil patches: implications for Songnen grassland restoration in northeast China. Land Degrad. Dev., 33: 710-722. DOI:10.1002/ldr.4169 |

Wang, Y., Sun, J., Chen, J., et al., 2023. Renewable energy relieves the negative effects of fences on animal feces utilization in Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Bull., 68: 2907-2909. DOI:10.1016/j.scib.2023.11.011 |

Wilson, C.H., Strickland, M.S., Hutchings, J.A., et al., 2018. Grazing enhances belowground carbon allocation, microbial biomass, and soil carbon in a subtropical grassland. Global Change Biol., 24: 2997-3009. DOI:10.1111/gcb.14070 |

Wu, Y.T., Guo, Z.W., Li, Z.Y., et al., 2022. The main driver of soil organic carbon differs greatly between topsoil and subsoil in a grazing steppe. Ecol. Evol., 12: 9182. DOI:10.1002/ece3.9182 |

Yan, Y.J., Niu, S.L., He, Y.C., et al., 2022. Changing plant species composition and richness benefit soil carbon sequestration under climate warming. Funct. Ecol., 36: 2906-2916. DOI:10.1111/1365-2435.14218 |

Yu, L.F., Chen, Y., Sun, W.J., et al., 2019. Effects of grazing exclusion on soil carbon dynamics in alpine grasslands of the Tibetan Plateau. Geoderma, 353: 133-143. DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.06.036 |

Zhang, Y.X., Tang, Z.X., You, Y.M., et al., 2023a. Differential effects of forest-floor litter and roots on soil organic carbon formation in a temperate oak forest. Soil Biol. Biochem., 180: 109017. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2023.109017 |

Zhang, Y.W., Peng, Z.C., Chang, S.H., et al., 2022. Growing season grazing promotes the shallow stratification of soil nutrients while non-growing season grazing sequesters the deep soil nutrients in a typical alpine meadow. Geoderma, 426: 116111. DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2022.116111 |

Zhang, Y.W., Peng, Z.C., Chang, S.H., et al., 2023b. Long-term grazing improved soil chemical properties and benefited community traits under climatic influence in an alpine typical steppe. J. Environ. Manag., 348: 119184. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119184 |

Zhao, L.P., Wang, D., Liang, F.H., et al., 2019. Grazing exclusion promotes grasses functional group dominance via increasing of bud banks in steppe community. J. Environ. Manag., 251: 109589. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109589 |

Zhu, E.X., Cao, Z.J., Jia, J., et al., 2021. Inactive and inefficient: warming and drought effect on microbial carbon processing in alpine grassland at depth. Global Change Biol., 27: 2241-2253. DOI:10.1111/gcb.15541 |

Zhu, J.T., Zhang, Y.J., Yang, X., et al., 2020. Warming alters plant phylogenetic and functional community structure. J. Ecol., 108: 2406-2415. DOI:10.1111/1365-2745.13448 |