b. Servicio de Vida Silvestre, Generalitat Valenciana, C./Castán Tobeñas, 77, 46018, Valencia, Spain;

c. Centro para la Experimentación e Investigación Forestal (CIEF), Generalitat Valenciana, Avda. Comarques del País Valencia, 114, 46930, Quart de Poblet, Valencia, Spain

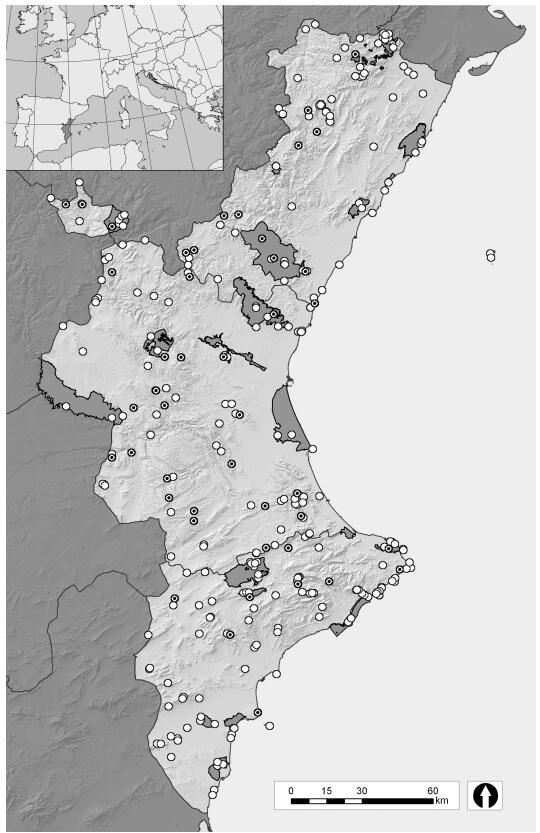

The Valencian Community is located at the eastern part of the Iberian Peninsula in the western Mediterranean (SW Europe) (Fig. 1). It covers a surface of 23, 255 km2 and occupies a long and narrow territory aligned on a north–south axis with 430 km of coastline. The region is characterized by a high diversity of geological substrates, soil and vegetation types with extensive plains, beaches and wetlands in the coastal zone and high mountains with elevations over 1800 m. Its climate is also much diversified, with annual mean temperature between 9 and 19.5 ℃ and rainfall ranging from (180) 240 to 750 (980) mm, which results in a high bioclimatic diversity (Costa, 1999; Aguilella et al., 2010). It has a population of approximately 5 million (2016 data) with 214 habitants/km2, although very irregularly distributed: the population concentrates in the coastal zones of the central and southern areas, whilst inland and northern areas are almost deserted.

|

| Fig. 1 Location of the Valencian Community and map of the region showing the distribution of the PMR (white circles) and NP (dark gray areas). 45 PMR selected for the study of the improvement of floristic knowledge are highlighted with a black dot inside the white circles. |

The Valencian Community is one of the richest botanical territories of Western Europe and a biodiversity hotspot of Mediterranean flora (Laguna et al., 2004; Médail and Quézel, 1999). At least 2696 species of native vascular plants grow here (Mateo and Crespo, 2014), including 399 endemic Spanish vascular plants, 70 of which can be considered strictly Valencian endemics. In addition, its flora has an outstanding concentration of relict plants, mainly from the Tertiary, as well as significant numbers of Eurosiberian and Saharo-Sindic species, due to the fact that the Valencian territory acted as a refuge for these taxa during glaciations.

Plant richness in Valencian region is not homogenously distributed. In fact, around 97% of endemics occur on rocky grounds or open shrublands, and, approximately, 65% of them grow in microhabitats (i.e., dunes, salt lagoons, coastal cliffs, petrifying springs, temporary ponds, relict forest, etc.), almost always as small patches. These facts make protection of this plant heritage with traditional schemes challenging, since the regional network of Natural Protected Areas was designed with much broader conservation goals (fauna, geology, landscape, ethnological peculiarities, etc.). Thus, to answer for the conservation needs of Valencian plants the Regional Wildlife Service developed a pioneering initiative for the in situ protection of plant diversity in the early 90's. It consisted of a network of small (< 20 ha) legally protected sites to ensure the conservation of selected populations of endemic, rare or endangered plants as well as natural habitats. They were named Plant Micro-Reserves (PMR) and conceived as a complement to large protected areas in their role to preserve biodiversity, rather than as an alternative or parallel scheme. In this respect, it is worth noting that a significant number of PMR are established within Natural Parks. The main legal and technical issues of Valencian PMRs have been summarized by Laguna et al.(2011, 2013a, b) and Laguna (2014) and also, an extensive analysis of the controversial debate regarding the optimal size for nature reserves (single large or several small) is developed in Laguna et al. (2016).

The first PMRs were declared in 1998 and since then the network has gradually increased to 300 sites by the end of 2016, widely scattered across the region (Fig. 1). The whole network covers now 22.9 km2, somewhat less than 0.1% of the regional surface. Despite the small surface covered, the Valencian PMR network includes populations of 1761 native vascular plants up to subspecies level (65.3% of total native flora). But, PMRs can also be an excellent tool for the conservation of other groups of species, like cryptogams. In fact, in the Valencian Community, PMR for bryophytes (Gimeno et al., 2001) or lichens (Atienza et al., 2001; Fos, 2005) have also been proposed and some declared PMR include some of these organisms among their priority species.

PMR philosophy has extended and its protection model is currently being adapted to other Spanish regions (Saldaña et al., 2013; Rubio, 2013; Fraga, 2005; Campos et al., 2013; Carrión et al., 2013) as well as by several European countries, such as Slovenia (Karst Regional Park; Sovinc and Lipej, 2013), Bulgaria (Natcheva et al., 2013), Cyprus (Kadis et al., 2013a), Greece (Thanos et al., 2013) and Italy (Aeolian Islands, Sicily; Troia, 2013), in most instances with economic support of the EU's LIFE-Nature program. Additionally, in its widest meaning of small nature reserves for plant conservation, the Valencian model has fostered initiatives in Mexico (Hernández & Gómez-Hinostrosa, 2011), Southern Brazil (Lenzi et al., 2015), Crete (Tsiftsis et al. 2011) and Turkey (Bulut and Yilmaz, 2010). Beijing Municipality has also drafted a project inspired by PMRs whose objective goal is to create small natural reserves for the protection of natural areas within megacities (Yuan et al., 2010).

On the other hand, a recent evaluation of the accomplishment of targets 2 (full species conservation assessment) and 7 (in situ and ex situ conservation of threatened plants) of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC) by Spain, highlights the role of PMRs as an effective means to achieve the 75% threshold of threatened flora preserved in situ (Muñoz-Rodríguez et al., 2016). Not in vain, the European Plant Conservation Strategy (Smart et al., 2002) specifically recommended PMRs as useful tool for site protection. However, their effectiveness regarding plant conservation still needs to be checked (Muñoz-Rodríguez et al., 2016).

During the nearly 25 years since the creation of protection figure and almost 20 years since the declaration of the first PMRs, a large amount of floristic data and abundant results on in situ conservation activities have been obtained. Thorough analysis of all this information will make it possible to establish the efficiency of the PMRs as a figure of territory protection for passive conservation of endemic and threatened plants. They also represent natural plots where the biological monitoring and active conservation management can be developed. However, this global analysis would be too lengthy and diverse for a unique paper.

On the other hand, the floristic knowledge of any region is a fundamental tool for plant conservation. Although the flora of the Valencian Community is well known, new populations of plant species are discovered periodically, and new species are even described. Therefore, any project, program or initiative that contributes to improving knowledge of regional flora should be valued positively.

Large protected areas attract researchers and naturalists, providing feedback on biodiversity values (Laird and Lisinge, 2002; Oldekop et al., 2016). Nevertheless, this relationship is less intuitive when the focus is placed on small protected areas, especially when they are poorly advertised and there is a lack of public use infrastructures (van Wilgen et al., 2016). Because of their small size, PMRs represent a unique opportunity to assess the role of small protected areas in improving knowledge of biodiversity.

Thus, as part of a larger evaluation effort, the aim of this paper is to present an assessment of this protection figure answering three main questions about passive conservation: (1) Does the PMR network shelter specially endemic or threatened species? (2) Are PMR better suited for plant conservation than Natural Parks? and (3) Is the PMR network useful to improve the knowledge of regional floras?. Solving these questions will help answer what is asked in the title about the utility of the PMR protection model to preserve threatened flora in China.

2. Materials and methodsIn order to assess if the PMR network provides enough passive protection to endemic or threatened plant species of the Valencian region and to compare its efficiency with that offered by Natural Parks (NP) in the Valencian Community, the number of vascular plants with at least one population in each network has been recorded using available floristic data from the Biodiversity Databank of the Valencian Region (BDBCV, http://bdb.cma.gva.es, updated October 2016). The Valencian Community has a network of 22 natural parks covering 164, 571 ha (Fig. 1) established since 1986 (Laguna et al., 2014). The characteristics of most of these protected areas have been described by Ballester et al. (2003).

The classification of endemism proposed by Laguna (1998) has been used: Type A: Strict endemic species of the Valencian region; Type B: Spanish endemics with global distribution centered in Valencian region, as well as extremely rare endemic plants shared with neighboring Spanish regions; Type C: Widely distributed Iberian endemics, but mostly only to be found in the Eastern part of the Iberian peninsula (Ibero-Levantine endemic plants).

Threatened species correspond to the legal categories of Decree 79/2009 (Anon., 2009), updated by Order 6/2013 (Anon., 2013): IDE, in danger of extinction; V, vulnerable; PNC, protected but non-cataloged; M, monitored species.

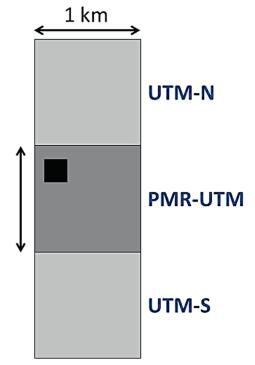

Finally, to evaluate if the PMR network improves floristic knowledge, both in the protected area itself and its surroundings, 45 PMR have been selected attending to the following criteria: (1) over 95% of its surface is included in a single 1 × 1 km UTM grid, (2) no PMR are present in the contiguous 1 × 1 km UTM grids to the North and South (Fig. 2), (3) the territory they cover is ecologically uniform and (4) the PMR is located in a floristically well-known territory (with over 500 species recorded in the 10 × 10 km UTM square according to the values of floristic richness provided by the BDBCV). For each selected PMR, the number of species present in the grid containing the PMR (UTM-PMR), in the adjoining grids with no PMR (UTM-no PMR) and in the 3 grids jointly were consulted in the BDBCV.

|

| Fig. 2 Graphic representation of the procedure used for the analysis of floristic richness in 3 adjacent UTM squares of 1 × 1 km. PMR is represented by the black square. |

Thesaurus for floristic richness (total number of species) of the Valencian Community follows Mateo and Crespo (2014). Nomenclature also follows that used by these authors, whom mostly utilized the nomenclature criteria of Flora iberica (Castroviejo, 1986–2014) and Flora Valentina (Mateo et al., 2011–2015).

3. Results and discussionThe original goal of PMRs was to incorporate populations of endemic plants. Accordingly, a high percentage (77%) of Spanish endemics present in the Valencian region has at least one population in the network (Table 1). However, the representation of each type of endemics shows important differences, with strict Valencian endemics (type A, 93%) being the best represented in the network, followed by those shared with neighboring regions (type B, 88%).

| VC | PMR | NP | |

| Number of areas | 300 | 22 | |

| Area (ha) | 2, 330, 500 | 2291 (0.1%) | 164, 571 (7.1%) |

| Total species | 3325 | 1949 (58.6%) | 2327 (70.0%) |

| Total native species | 2696 | 1761 (65.3%) | 2032 (75.4%) |

| Endemicity | |||

| Type A | 70 | 66 (94.3%) | 50 (71.4%) |

| Type B | 93 | 85 (91.4%) | 71 (76.3%) |

| Type C | 236 | 160 (67.8%) | 149 (63.1%) |

| Total Endemics | 399 | 311 (77.9%) | 270 (67.7%) |

| Protection categories | |||

| In danger of extinction | 35 | 21 (60.0%) | 17 (48.6%) |

| Vulnerable | 50 | 35 (70.0%) | 22 (44.0%) |

| Total VCTPS | 85 | 56 (65.9%) | 39 (45.6%) |

| Protected but not cataloged | 142 | 62 (43.7%) | 49 (34.5%) |

| Monitored | 163 | 106 (65.0%) | 101 (62.0%) |

| Total protection categories | 390 | 224 (57.4%) | 189 (48.5%) |

Representativeness of threatened species within the PMR network is lower than endemic. 66% of Cataloged taxa are represented by one or more populations. This proportion is slightly lower for all protected species (57%). The low success of the network regarding inclusion of endangered species could be put down to the initial focus on endemics (Fos et al., 2014) and because the rarest species grow in a very restricted range of sites, frequently on private grounds, where PMRs cannot be established against a landowner's will. In this respect, it is worth noting that forest lands under private management are larger (55%) than those under public steward (39%) or unknown ownership (6%).

Nevertheless, the ability of the PMR network to incorporate species in the most relevant categories for conservation (endemic and threatened plants) is clearly higher than that of Natural Parks (NP). In this respect, the percentage of species within each category found in the NP network as a whole is consistently lower for an area 70 times larger and despite the fact that its tally of species is higher (Table 1). Differences are particularly significant regarding endemics with restricted ranges (A and B types) and species protected by the Valencian Catalog of Threatened Plant Species (In danger of extinction and vulnerable). Therefore, PMR (small-scale reserve) in conjunction with NP (large-scale) allow the inclusion of relevant endemic and threatened species in a global network of protected natural areas, underlining the complementary role of these two schemes and its validity for plant conservation, but also for wild crop relatives, potentially important species from an economic perspective, etc. (Laguna et al., 2016).

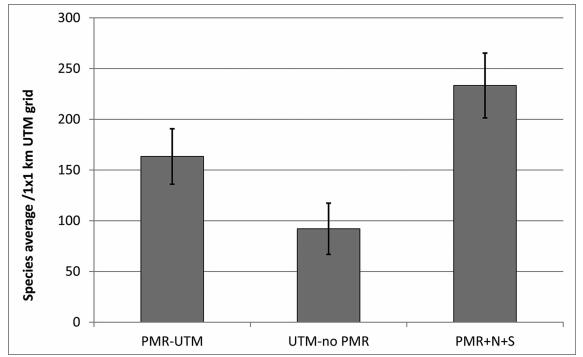

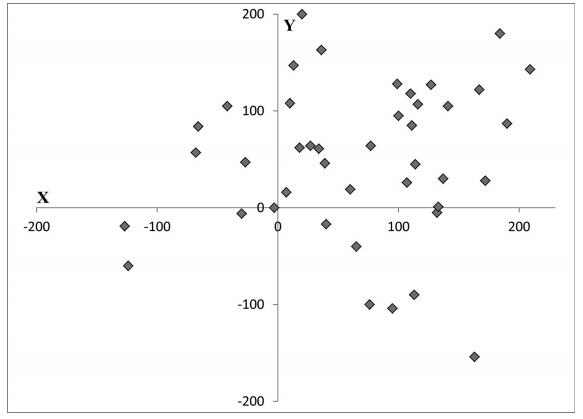

With regard to improvement of floristic knowledge, comparison in contiguous 1 × 1 km UTM squares proves that more species are recorded in the UTM-PMR grid than in the adjacent ones. The species average count in UTM-PMR is significantly higher than that of UTM-no PMR, but significantly lower than the average richness for the 3 grids altogether (3 km2) (Fig. 3). In fact, most PMR-UTM grids show the highest floristic richness and, consequently, contribute most significantly to the total flora count of the 3 grids. In order to confirm that PMR-UTMs are better studied from a floristic perspective, with a greater number of species recorded, than the two adjacent grids, PMRs have been plotted according the difference between the number of species recorded in the PMR-UTM and in each of the other 2 grids (UTM-N and UTM-S). The PMR concentration in the positive quadrant for both axes (67%) confirms that grids containing PMRs are better studied from a floristic point of view than any of the adjacent two (Fig. 4). In some cases, the differences exceed one and even two hundred species. On the contrary, only 5 PMRs show floristic differences of this magnitude in the negative part of both axes. Thus, this analysis highlights the fact that PMRs act as focal point for floristic studies and contributes in a very significant way to the floristic knowledge of a more extensive territory.

|

| Fig. 3 Average species richness for PMR-UTM, UTM-no PMR (considering N and S UTM grids independently) and of the 3 grids combined (PMR + N + S). Error bars represent confidence interval at 95% level. |

|

| Fig. 4 Scatter plot of PMR according to the differences between the number of species cited in the PMR-UTM and each of the 2 adjacent grids (X = PMR-S UTMs; Y = PMR-N UTMs). |

Progress in the quantitative knowledge of vascular flora in PMRs and their surroundings also allows to discover new populations of species not previously recorded when they were declared. Since the passing of Decree 70/2009, intensive search of potential habitats has been carried out to locate new populations of threatened species. As a result, 223 new populations of Cataloged and other priority endangered species have been found. Given the differences in the territorial extent between both samples (inside and outside of the PMR network), the results are as expected: more new populations have been located outside the PMR network; however, the percentage within of this network is much higher than its area representation (Table 2). When this variable is considered, 0.02 populations/km2 have been discovered outside the PMR network, whereas inside this network this figure rises to 3.49 populations/km2.

| New populations | Outside PMR | Inside PMR | |

| In danger of extinction | 54 | 52 | 2 (4%) |

| Vulnerable | 169 | 152 | 17 (10%) |

| Protected but not catalogued | 336 | 275 | 61 (18%) |

| Total | 559 | 479 | 80 (14%) |

As indicated by Kadis et al. (2013b), the Valencian model of PMRs can be successfully exported to other territories, adapting their main characteristics to the legal framework of each region or country. Despite the enormous differences in size and diversity between the Valencian Community and China or its different regions, this model could help solve some problems found in the protection of Chinese endangered plants. On one hand, China shows significant gaps in the protection of wild flora (Xu et al., 2012; López-Pujol et al., 2006; López-Pujol and Zhang, 2009), particularly regarding species affected by recent anthropogenic developments (Zhang et al., 2015; Feng et al., 2017). On the other hand, the Chinese system of protected areas cannot afford enough protection to a significant amount of narrow area endemics as well as to species occurring in restricted and scattered sites (López-Pujol and Zhang, 2009; Ma et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015). Although a project on Conservation of Plant Species with Extremely Small Populations (PSESP) is being developed by the Chinese State Forestry Administration, it could be unable to provide enough protection for these species (Ren et al., 2012). The results have shown that PMRs are highly effective in protecting narrow species in Valencian Community. In fact, Volis (2016) has recently proposed the PMR as a tool to conserve PSESPs. The protection of the endemic Chinese flora, with around 17, 000 species (over 50% of the estimated species of vascular plants), including a large part of narrow endemics (Huang et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015) is of paramount importance. So, the strategy of setting up PMR for plant and habitat protection could be highly recommendable.

As mentioned above, the protection model named PMR has been adapted to other regions and countries and nowadays cannot be considered as a homogeneous concept, but a family of types of protected areas in active growth and diversification (Laguna, 2014). The procedure of legislation in Valencian model is based in Decree 218/1994 of the Valencian Government (Anon., 1994). It confers PMRs a permanent status and provides a high level of legal protection to plants and substrates, while allowing traditional activities compatible with plant conservation. In fact, some of them, such as cattle raising, grassland harvesting or vegetation clearing, etc., are even favored when species of conservation concern require open ground to survive. However, each PMR is independently declared by Order of the regional Department of Environment, including its geographical delimitation, a description of features generating the interest of the area (plant species and habitats), the specific management plan (main actions for the investigation and conservation of target element), the special limitations, etc. PMRs are declared on government-owned or public land, but also on private land at the request of their respective owners (private, NGOs or city councils). This entire legal frame guarantees the protection of natural plots to ensure the biological monitoring and conservation management. It is important to expose that the main aim of PMR network is not to preserve the species, but to protect their study and active conservation. More information on the procedures to select, landmark and management can be found in several books and articles published by Laguna (Laguna, 2001, 2014; Laguna and Deltoro, 2013; Laguna et al., 2004, 2013a, b).

The Chinese network of natural protected areas (see Jianming, 1997; Xu et al., 2012; Guo and Cui, 2015) is complex and made up of 3078 Chinese Nature Reserves and National Nature Reserves. However, only 155 are mainly devoted to plant protection (Guo and Cui, 2015). These authors —who set a threshold for small reserves at 50 km2— show that only 91 small Nature Reserves and 4 small National Nature Reserves are devoted to plant protection, totaling 1328.97 km2 (average size 13.98 km2 per reserve). In this respect, the average size of Valencian PMRs is 7.63 ha, and the maximum size of a PMR is 20 ha (=0.2 km2) by law. Considering the size scale of Guo and Cui (2015), Valencian PMRs could be considered 'extremely small nature reserves'. Comparing the size of the Valencian region (23, 305 km2) with that of China (9, 596, 960 km2), a similar model of plant protection would consist of 120 × 103 PMRs. Obviously, such an intense effort to protect wild plant populations cannot be afforded by the national administration, but regional and local governments could develop ad hoc figures, able to be managed at local scale. In addition, the fast economic development of China make difficult to set up large reserves, especially in eastern China where the population in concentrated. The network of roads and train and the urbanization processes have been expanded at an impressive rate. Thus, a strategy of setting small reserves seems to be specially suited for the Chinese case. And its combination with the Nature Reserves, which cover a relative large percentage of China, approximately 15% of its total land area (Wu et al., 2011), may produce good results like those obtained in Valencian Community.

Finally, as shown in this paper, the declaration of PMRs can foster knowledge of plant diversity and the discovery of new populations of endangered species. This is especially important for China, where it is estimated that at least 2000 species are awaiting to be described (Raven, 2011). In addition, the floristic knowledge is still very poor in many areas, especially in the mountainous western parts of China. Therefore, the establishment of the Valencian model could significantly improve Chinese plant knowledge while providing effective protection to its rich plant heritage.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge the collaboration of the plant technicians working for the Valencian Wildlife Service (Servicio de Vida Silvestre, Generalitat Valenciana), for providing updated information on the plant species richness for each PMR. Additionally, we wish to thank Dr. V.I. Deltoro (Vaersa-Servicio de Vida Silvestre, Generalitat Valenciana) for his language revision, to C. Andrés (Vaersa-Servicio de Vida Silvestre, Generalitat Valenciana) for his support in the preparation of the geographical map and also to N. Fabuel (CETECK) for the management of the floristic data from the Biodiversity Databank of the Valencian Region. We are also grateful to Dr Jordi López-Pujol and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments and useful provided which enhanced significantly the manuscript. Finally, we are very grateful to Dr. Vernon H. Heywood for presenting this communication during the IABG International Conference, in Shanghai. No grants have funded specifically this study. However, the establishment and development of the PMR network has received financial support from EU funds, including 2 LIFE-Nature projects and the EAFRD.

Aguilella, A., Fos, S., Laguna, E. (Eds. ), 2010. Catálogo Valenciano de Especies de Flora Amenazadas. Generalitat Valenciana, Valencia.

|

||

Anonymous, 1994. Decreto 218/1994 de 17 de octubre, por el que se crea la figura de protección de especies silvestres denominada microrreserva vegetal. D. of. la Comunitat Valencia, 2379, 12948-12951.

|

||

Anonymous, 2009. Decreto 70/2009, de 22 de mayo, del Consell, por el que se crea y regula el Catálogo Valenciano de Especies de Flora Amenazadas y se regulan medidas adicionales para su conservación. D. of. la Comunitat Valencia, 6021, 20143-20162.

|

||

Anonymous, 2013. Orden 6/2013, de 25 de marzo, de la Conselleria de Infraestructuras, Territorio y Medio Ambiente, por la que se modifican los listados valencianos de especies protegidas de flora y fauna. D. Of. la Comunitat Valencia, 6996, 8682-8690.

|

||

Atienza V., Segarra J.G., Laguna E., 2001. Propuesta de microrreservas vegetales.Una alternativa para la conservación de líquenes en la Comunidad Valenciana. Bot. Complut, 25, 115-128.

|

||

Ballester, J. A., Díes, B., Hernández-Muñoz, J. A., Laguna, E., Oltra, C., Palop, S., Urios, G., 2003. Natural Parks of the Valencian Community. Lunwerg and Generalitat Valenciana, Valencia.

|

||

Bulut Z., Yilmaz H., 2010. The current situation of threatened endemic flora in Turkey:Kemaliye Kerzincan case. Park. J. Bot, 42(2), 711-719.

|

||

Campos, J. A., Liendo, D., Prieto, A., Renobales, G., Herrera, M., 2013. Plant microreserves as a tool for the protection of endangered flora: the Bizkaia case(Basque country, Spain). In: Kadis, C., Thanos, C. A., Laguna, E. (Eds. ), Plant Micro-reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects. PlantNet CY Project Beneficiaries. Utopia Publishing, Athens, pp. 95-96.

|

||

Carrión, M. A., García, J., Guerra, J., Sánchez-Gómez, P., 2013. Plant micro-reserves in the region of Murcia. In: Kadis, C., et al. (Eds. ), Plant Micro-reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects. PlantNet CY Project Beneficiaries. Utopia Publishing, Athens, pp. 101-104.

|

||

Castroviejo, S. (Ed. ), 1986-2014. Flora iberica. Plantas vasculares de la Península Iberica-Islas Baleares, vol. 19. Real Jardín Botánico-CSIC, Madrid.

|

||

Costa, M., 1999. La vegetacion y el paisaje en las tierras valencianas. Editorial Rueda, Valencia.

|

||

Feng G., Mao L., Benito B.M., Swenson N.G., Svenning J.C., 2017. Historical anthropogenic footprints in the distribution of threatened plant in China. Biol. Conserv, 210(Part B), 3-8.

DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.038 |

||

Fos, S., 2005. La red de Microrreservas de la Comunidad Valenciana: una herramienta para la conservación de las cript ogamas. El caso de los líquenes. XV Simposio de Botánica Criptog ámica. Libro Resúmenes 96. Bilbao.

|

||

Fos S., Laguna E., Jiménez J., 2014. Plant micro-reserves in the Valencian region (E of Spain):are we achieving the expected results? passive conservation of relevant vascular plant species. Fl. Medit, 24, 153-162.

DOI:10.7320/FlMedit24.153 |

||

Fraga, P. (Coord. ), 2005. Proposta de microreserves de flora. Consell Insular de Menorca. Mahón. http://www.cime.es/lifeflora/descargas/microreservas.pdf.

|

||

Gimeno C., Puche F., Segarra J.G., Laguna E., 2001. Modelo de conservación de la flora briologica en la Comunidad Valenciana:microrreservas de flora criptogamica. Bot. Complut, 25, 221-231.

|

||

Guo Z., Cui G., 2015. Establishment of nature reserves in administrative regions of mainland China. PLoS One, 10(3), 30119650.

|

||

Hernández H.M., Gómez-Hinestrosa C., 2011. Areas of endemism of Cactaceae and the effectiveness of the protected area network in the Chihuahuan desert. Oryx, 45, 191-200.

DOI:10.1017/S0030605310001079 |

||

Huang J.-H., Chen J.-H., Ying J.-S., Ma K.-P., 2011. Features and distribution patterns of Chinese endemic seed plant species. J. Syst. Evol, 49, 81-94.

DOI:10.1111/j.1759-6831.2011.00119.x |

||

Jianming J., 1997. The construction and management of nature reserves in China. J. Environ. Sci, 9(2), 129-140.

|

||

Kadis, C., Andreou, M., Kouzali, I., Kounnamas, C., Constantinou, C., Eliades, N. G., 2013a. Establishment of a plant micro-reserve network in Cyprus for the conservation of priority species and habitats. In: Kadis, C., et al. (Eds. ), Plant Micro-reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects. PlantNet CY Project Beneficiaries. Utopia Publishing, Athens, pp. 37-50.

|

||

Kadis, C., Thanos, C. A., Laguna, E. (Eds. ), 2013b. Plant Micro-reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects. PlantNet CY Project Beneficiaries. Utopia Publishing, Athens.

|

||

Laguna, E., 2001. The micro-reserves as a tool for conservation of threatened plants in Europe. Nature and Environment 21. Council of Europe Publishing.

|

||

Laguna, E. (Coord. ), 1998. Flora endémica, rara o amenazada de la Comunidad Valenciana. Consellería de Medio Ambiente. Generalitat Valenciana. Valencia.

|

||

Laguna, E., 2014. Origin, concept and evolution of plant micro-reserves: the pilot network of the Valencian community (Spain). In: Vladimirov, V. (Ed. ), A Pilot Network of Small Protected Sites for Conservation of Rare Plants in Bulgaria. Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences) and Ministry of Environment and Water, Sofia, pp. 14-24.

|

||

Laguna, E., Deltoro, V. I., 2013. Legal framework for plant micro-reserves. In: Kadis, C., et al. (Eds. ), Plant Micro-reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects. PlantNet CY Project Beneficiaries. Utopia Publishing, Athens.

|

||

Laguna E., Deltoro V.I., Pérez-Botella J., Pérez-Rovira P., Serra L., Olivares A., Fabregat C., 2004. The role of small reserves in plant conservation in a region of high diversity in eastern Spain. Biol. Conserv, 119, 421-426.

DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2004.01.001 |

||

Laguna, E., Fos, S., Jiménez, J., 2014. Efectividad comparada de la protección pasiva de plantas singulares en las redes valencianas de microrreservas de flora y de espacios naturales protegidos. In: Camara, R., Rodríguez, B., Muriel, J. L. (Eds. ), Sistemas vegetales y fauna en medios litorales: Avances en su caracterizacion, dinamica y criterios para su conservaci on. Universidad de Sevilla & AEG, pp. 237-244.

|

||

Laguna E., Fos S., Jimenez J., Volis S., 2016. Role of micro-reserves in conser-vation of endemic, rare and endangered plants of the Valencian region(Eastern Spain). Israel J. Plant Sci, 63(4), 320-332.

DOI:10.1080/07929978.2016.1256131 |

||

Laguna, E., Ballester, G., Deltoro, V. I., Fabregat, C., Fos, S., Olivares, A., Oltra, J. E., Pérez Botella, J., Pérez Rovira, P., Serra, L., 2011. La red valenciana de microrreservas de flora: Síntesis de 20 años de experiencia. In: Giménez, P., Marco, J. A., Matarredona, E., Padilla, A., Sanchez, A. (Eds. ), Biogeografía. Una ciencia para la conservación del medio, pp. 265-272. Alicante.

|

||

Laguna, E., Ballester, G., Deltoro, V. I., Fos, S., Carchano, R., Oltra, J. E., Perez Botella, J., Perez Rovira, P., 2013a. A pioneer project: the Valencian plant micro-reserves network. In: Kadis, C., Thanos, C. A., Laguna, E. (Eds. ), Plant Micro-reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects, pp. 13-23. Athens.

|

||

Laguna, E., Fraga, P., Estaún, I., Cardona, E., Deltoro, V., 2013b. Landowner's engagement agreements and stewardship for micro-reserves conservation. In: Kadis, C., Thanos, C. A., Laguna, E. (Eds. ), Plant Micro-reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects. PlantNet CY Project Beneficiaries. Utopia Publishing, Athens, pp. 165-176.

|

||

Laird, S. A., Lisinge, E. E., 2002. Protected area research policies: developing a basis for equity and accountability. In: Laird, S. A. (Ed. ), Biodiversity and Traditional Knowledge: Equitable Partnerships in Practice. Earthscan, London, pp. 126-176.

|

||

Lenzi M., Zarur de Matos J., Fraga A.M., Crespo M.B., 2015. Orchids of the state park of Serra do Tabuleiro. South. Braz. An. Jard. Bot. Madr, 72(2), e020.

DOI:10.3989/ajbm.2345 |

||

Liu J.-Q., Ren M.-X., Susanna A., López-Pujol J., 2015. Special issue on Ecology evolution, and conservation of plants in China:introduction and some considerations. Collect. Bot, 34, e001.

DOI:10.3989/collectbot.2015.v34.001 |

||

López-Pujol J., Zhang F.M., Ge S., 2006. Plant biodiversity in China:rich varied, endangered and in need of conservation. Biodivers. Conserv, 15, 3983-4026.

DOI:10.1007/s10531-005-3015-2 |

||

López-Pujol J., Zhang Z.Y., 2009. An insight into the most threatened flora of China. Collect. Bot. Barc, 28, 95-110.

|

||

Ma Y., Chen G., Grumbine R.E., Dao Z.L., Sun W., Hiujun G., 2013. Conserving plant species with extremely small populations (PSESP) in China. Biodivers. Conserv, 22, 803-809.

DOI:10.1007/s10531-013-0434-3 |

||

Mateo, G., Crespo, M. B., 2014. Manual para la determinacion de la flora valenciana[Handbook for the identification of the Valencian flora]. Monografías de Flora Montiberica, 6. Jaca, Jolube Consultor Bot anico y Editor. Spanish.

|

||

Mateo, G., Crespo, M. B., Laguna, E. (Eds. ), 2011-2015. Flora Valentina: Flora vascular de la Comunidad Valenciana. 3 vols. Valencia: Fundacion de la Comunidad Valenciana para el Medio Ambiente.

|

||

Médail F., Quézel P., 1999. Biodiversity hotspots in the Mediterranean Basin:setting global conservation priorities. Conserv. Biol, 13, 1510-1513.

DOI:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.98467.x |

||

Muñoz-Rodríguez P., Draper D., Moreno J.C., 2016. Global strategy for plant con-servation:inadequate in situ conservation of threatened flora in Spain. Israel J. Plant Sci, 63(4), 297-308.

DOI:10.1080/07929978.2016.1257105 |

||

Natcheva, R., Bancheva, S., Vladimirov, V., Goranova, V., 2013. A pilot network of small protected areas for plant species in Bulgaria using the plant micro-reserve model. In: Kadis, C., Thanos, C. A., Laguna, E. (Eds. ), Plant Micro-reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects. PlantNet CY Project Beneficiaries. Utopia Publishing, Athens, pp. 53-64.

|

||

Oldekop J.A., Holmes G., Harris W.E., Evans K.L., 2016. A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conserv. Biol, 30(1), 133-141.

DOI:10.1111/cobi.12568 |

||

Raven P.H., 2011. Plant conservation in the future:new challenges, new opportunities. Plant Divers. Resour, 33(1), 1-9.

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1143.2011.10255 |

||

Ren H., Zhang Q.M., Lu H.F., Liu H.X., Guo Q.F., Wang J., Jian S.G., Bao H.O., 2012. Wild plant species with extremely small populations require conservation and reintroduction in China. Ambio, 41, 913-917.

DOI:10.1007/s13280-012-0284-3 |

||

Rubio, M. A., 2013. Micro-reserves: a useful tool for the conservation strategy of the natural environment in Castilla-La Mancha (Spain). In: Kadis, C., Thanos, C. A., Laguna, E. (Eds. ), Plant Micro-reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects. PlantNet CY Project Beneficiaries. Utopia Publishing, Athens, pp. 79-82.

|

||

Saldaña, A., Amich, F., Fernández-Gonz alez, F., Puente, E., Rico, E., 2013. Plant microreserves in Castilla y León (Spain). In: Kadis, C., Thanos, C. A., Laguna, E. (Eds. ), Plant Micro-reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects. PlantNet CY Project Beneficiaries. Utopia Publishing, Athens, pp. 97-100.

|

||

Smart, J., Imboden, Ch, Harper, M., Radford, E. (Eds. ), 2002. Saving the Plants of Europe. European Plant Conservation Strategy. Planta Europa, Council of Europe & Plantlife International, London.

|

||

Sovinc, A., Lipej, B., 2013. The micro-reserve project in the regional park of the Slovenian Karst. In: Kadis, C., et al. (Eds. ), Plant Micro-Reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects. PlantNet CY Project Beneficiaries. Utopia Publishing, Athens, pp. 75-78.

|

||

Thanos, C. A., Fournaraki, Ch, Georghiou, K., Dimopoulos, P., 2013. PMRs in western Crete. In: Kadis, C., et al. (Eds. ), Plant Micro-Reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects. PlantNet CY Project Beneficiaries. Utopia Publishing, Athens, pp. 27-36.

|

||

Troia, A., 2013. Proposals of plant micro-reserves in Sicily (Italy). In: Kadis, C., Thanos, C. A., Laguna, E. (Eds. ), Plant Micro-reserves: from Theory to Practice. Experiences Gained from EU LIFE and Other Related Projects. PlantNet CY Project Beneficiaries. Utopia Publishing, Athens, pp. 83-85.

|

||

Tsiftsis S., Tsiripidis I., Trigas P., 2011. Identifying important areas for orchid conservation in Crete. Eur. J. Environ. Sci, 1(2), 28-37.

|

||

van Wilgen B.W., Boshoff N., Smit I.P., Solano-Fernandez S., van der Walt L., 2016. A bibliometric analysis to illustrate the role of an embedded research capability in South African National Parks. Scientometrics, 107(1), 185-212.

DOI:10.1007/s11192-016-1879-4 |

||

Volis S., 2016. How to conserve threatened Chinese plant species with extremely small populations?. Plant Divers, 38, 45-52.

DOI:10.1016/j.pld.2016.05.003 |

||

Wang L., Jia Y., Zhang X., Qin H., 2015. Overview of higher plant diversity in China. Biodivers. Sci, 23, 217-224.

DOI:10.17520/biods.2015049 |

||

Wu R., Zhang S., Yu D.W., Zhao P., Li X., Wang L., Yu Q., MA J., Chen A., Long Y., 2011. Effectiveness of China's nature reserves in representing ecological diversity. Front. Ecol. Environ, 9, 383-389.

DOI:10.1890/100093 |

||

Xu J., Zhang Z., Liu W., McGowan J.K., 2012. A review and assessment of nature policy in China:advances, challenges and opportunities. Oryx, 46, 554-562.

DOI:10.1017/S0030605311000810 |

||

Yuan X., Liu Y., Zhang L.L., Li J.W., Li J.Q., 2010. Construction scheme and management pattern of small nature reserves in Beijing. J. Beijing For. Univ. Soc. Sci, 9, 59-64.

|

||

Zhang Z., He J.S., Li J., Tang Z., 2015. Distribution and conservation of threatened plants in China. Biol. Conserv, 192, 454-460.

DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2015.10.019 |