b. Universidad Intercultural de Baja California (UIBC), San Quintín, Baja California, C.P. 22930, Mexico;

c. Instituto de Silvicultura e Industria de la Madera, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Constitución 404 sur. Zona Centro, C.P. 34000, Durango, Mexico;

d. Departamento de Ecología Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 04510, CDMX, Mexico;

e. Departamento de Botánica, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 3er. Circuito Exterior, Ciudad Universitaria, C.P. 04510, Coyoacán, CDMX, Mexico;

f. Postgrado en Ciencias Forestales, Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo, Texcoco, 56264, Estado de México, Mexico;

g. Institute for System and Integrated Biology (IBIS), Université Laval, Charles-Eugène-Marchand Pavilion, 1030 Avenue de la Médecine, Quebec City, G1V 0A6, Québec, Canada;

h. Instituto Politécnico Nacional, CIIDIR Unidad Durango, Sigma 119 Fracc. 20 de Noviembre II, 34234, Durango, Durango, Mexico;

i. Thünen Institute of Forest Genetics, Sieker Landstr. 2, D-22927, Grosshansdorf, Germany;

j. Instituto de Investigaciones sobre los Recursos Naturales (INIRENA), Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo (UMSNH). Av. San Juanito Itzícuaro s/n, Col. Nueva Esperanza, Morelia Michoacán, 58337, Mexico;

k. Instituto de Ecología Aplicada, Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, División del Golfo 356, Col. Libertad, Ciudad Victoria, 87019, Mexico;

l. Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo (UMSNH). Av. J. Mújica s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Morelia, Michoacán, C.P. 58030, Mexico

The presence of heterozygous individuals in a population is crucial for maintaining genetic diversity, which can positively affect fitness and adaptability to environmental changes (Reed and Frankham, 2003; Kremer et al., 2012). Heterozygosity excess in a population leads to higher genetic diversity, which may improve the population's ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions due to the presence of a reservoir of different alleles that may prove favourable under different selection pressures. However, in essentially all naturally outbreeding species heterozygosity excess can also have negative effects if accompanied by inbreeding depression, in which deleterious recessive alleles are more likely to accumulate and be expressed in closely related individuals. This can lead to reduced fitness (Wright, 1977; Charlesworth and Charlesworth, 1987; Thornhill, 1993; Frankham, 1995a; Falconer and Mackay, 1996), lower reproductive success, a general population decline (Balloux et al., 2004) and an increased risk of extinction (Frankel and Soulé, 1981; Frankham, 1995b; Newman and Pilson, 1997).

Inbreeding usually leads to a reduction in the proportion of heterozygous individuals in a population, as it increases the probability that two alleles in an individual come from the same ancestor and are thus identical by descent, which is referred to as the inbreeding coefficient (F) (Wright, 1969; Crow and Kimura, 1970). Therefore, the inbreeding coefficient of a population (FIS) is a useful parameter for analyzing various aspects of the evolution of plant mating systems, e.g., the relationship between inbreeding history and certain traits, such as self-fertilization capacity or probability (Schultz and Willis, 1995). FIS is highly dependent on the rate of asexual reproduction within a population (Stoeckel et al., 2006). For instance, asexuality limits the segregation of alleles, conserves ancestral heterozygosity through generations, and increases heterozygosity, since alleles of the same gene locus may independently accumulate mutations over generations, in a phenomenon also known as the Meselson effect (Judson and Normark, 1996; Stoeckel and Masson, 2014). The mutations only accumulate if they are (almost) neutral and there is no overdominance (i.e., there is an additive effect of the mutations on the phenotype). In addition, progressive or balanced selection can promote the overlapping of heterogeneous strains/clones (Haigh and Smith, 1974; Pavlidis and Alachiotis, 2017).

In general, polyploid individuals and populations retain a higher degree of heterozygosity and exhibit less inbreeding depression than their diploid ancestors and can therefore tolerate a higher degree of self-fertilization (Soltis and Soltis, 2000). Polyploidy is frequent in angiosperms, occurring in more than 50% of species (Weiss-Schneeweiss et al., 2013). Indeed, it is believed that environmental fluctuations can lead to adaptive responses via the formation of polyploids (Van de Peer et al., 2017), especially in connection with stress (Van de Peer et al., 2021). Polyploidy can improve tolerance to abiotic and biotic stress factors and boost disease resistance, which can have positive effects on plant growth and net production (Greer et al., 2018; Blonder et al., 2020; Tossi et al., 2022). The high levels of genetic diversity in polyploids can help individuals and populations to colonize regions and persist under strong climate variation (Dynesius and Jansson, 2000).

Populus tremuloides Michx. (quaking aspen) is one of the most widely distributed and ecologically important tree species in the Northern Hemisphere (Wang et al., 2016). The species distribution ranges from Alaska through Canada and the United States to central Mexico, covering a wide range of ecosystems and elevations (Little, 1971; Perala, 1990). Quaking aspen is an early successional tree that is adapted to natural disturbances (e.g., fire and disease); it is highly tolerant of environmental stress and is capable of colonizing new areas and rejuvenating existing stands (Swift and Ran, 2012; Goessen et al., 2022). These capacities are due to the reproductive flexibility of the species, which can reproduce sexually (through seeds and pollen suitable for wide-ranging wind dispersal) and asexually (through root suckers) (Barnes, 1966; Mitton and Grant, 1996), and to ploidy-level variation (Mock et al., 2012; Goessen et al., 2022). The quaking aspen, together with the European aspen, has the highest level of intraspecific genetic diversity ever recorded in a plant species (Cole, 2005; Callahan et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2016), which also contributes to its great adaptability.

However, the genetic diversity and structure of Mexican populations of Populus tremuloides, including the genetic signatures of their adaptation to a variety of environments, remain largely uncharacterized (Ouborg et al., 2010; Callahan et al., 2013). Previous studies used AFLP markers to identify significant large-scale spatial genetic structure in P. tremuloides (Quiñones-Pérez et al., 2014) and found that P. tremuloides had lower AFLP diversity than other Mexican tree species, as well as significantly positive associations between neighbor tree species diversity and genetic diversity (Simental-Rodríguez et al., 2014). In addition, one study reported that almost all P. tremuloides individuals in each of seven forest sample plots in the Mexican Sierra Madre Occidental were genetically different concluding that vegetative reproduction probably only plays a secondary role in quaking aspen in this region (Wehenkel et al., 2014). These findings are partially in accordance with those reported by Goessen et al. (2022), who investigated the entire Mexican genetic cluster by using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers. These researchers found that: (i) a large number of clonemates are located in Mexican aspen stands and (ii) several SNPs are under selection and impacted by temperature and precipitation variation across the four main genetic clusters in northeastern North America, northwestern North America, the western United States and Mexico.

The aim of this study was to analyze how inbreeding coefficient and ploidy level are associated with clonal richness, climate and soil traits in 91 marginal to small, isolated populations of Populus tremuloides throughout its entire distribution in Mexico (i.e., Baja California, Sierra Madre Oriental, Sierra Madre Occidental, and the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt), by using SNP markers derived from genotype by sequencing (GBS). We hypothesized that: (i) asexual reproduction will increase the expected allelic diversity within populations and will lead to more negative FIS, i.e., extreme heterozygote excess (Stoeckel and Masson, 2014), and (ii) progressive selection against deleterious recessive alleles will result in less negative FIS values in adaptive loci (Mitton (1989) in Stoeckel et al. (2006)). We also hypothesized that the rate of asexual propagation affects ploidy and that higher ploidy levels tend to occur in more extreme environmental conditions (Dynesius and Jansson, 2000; Goessen et al., 2022).

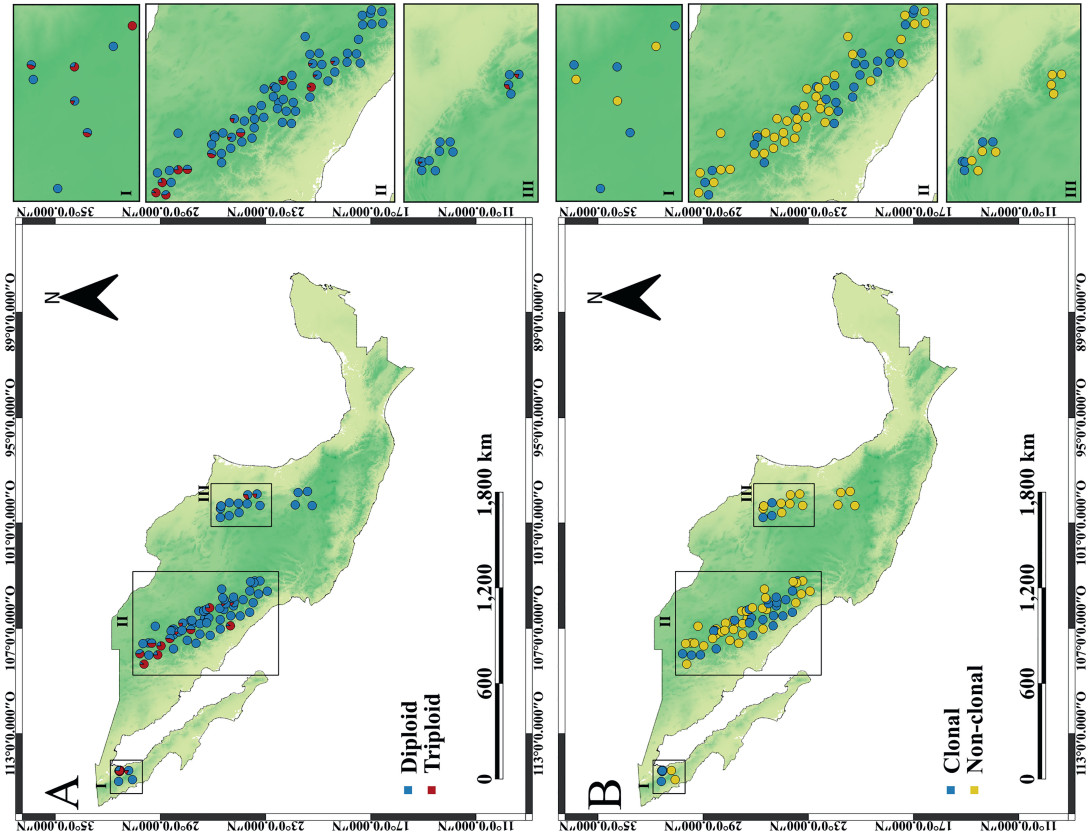

2. Materials and methods 2.1. Study area and samplingLeaf samples were collected from 809 spatially georeferenced Populus tremuloides trees in 91 natural populations in Mexico. These populations were distributed in the Sierra de San Pedro Mártir (SSPM; Baja California), Sierra Madre Occidental (SMO; Durango, Chihuahua and Sonora), Sierra Madre Oriental (SMOr; Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas) and the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (Hidalgo, Michoacán and Queretaro, in central Mexico) (Fig. 1). Detailed information about the location of the sampled stands is provided in Table S1. The population cover (in hectares) was determined using Google Earth Pro v.6 (http://www.google.com/earth/index.html [Accessed 10 November 2023]) (see Table S2 for further details).

|

| Fig. 1 Spatial distribution maps of (A) relative frequency of ploidy levels, and (B) clones in the 91 Mexican Populus tremuloides populations under study. |

|

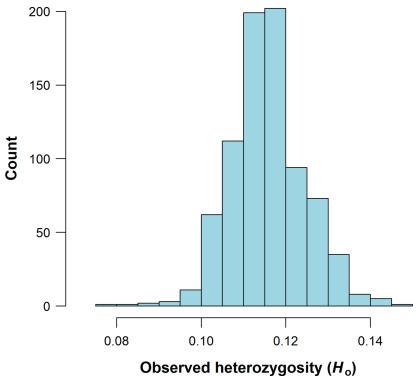

| Fig. 2 Histogram of observed heterozygosity in 809 individuals from the 91 Populus tremuloides populations under study using the "DartR"package in R v.4.2.1, with all filtered SNPs. |

DNA was extracted from dried leaves obtained in the field. The Nucleospin 96 Plant II kit (Macherey–Nagel, Bethlehem, PA) was used following the manufacturer's protocol for the centrifugation process, with modifications regarding the cell lysis step (PL2 buffer was heated at 65 ℃ for 2 h instead of 30 min). DNA concentrations were adjusted to 10 ng/μl before library preparation and randomization of samples.

2.3. Library preparation and sequencingLibraries were prepared at the «Plateforme d'analyses génomiques, Institut de Biologie Intégrative et des Systèmes» (IBIS, Université Laval, Québec, Canada). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 S4 (1 lane) sequencing system (Centre d'expertise et de services Génome Québec in Montréal, Canada), and 150-bp paired-end were obtained in the FastQ format (as described in Poland et al. (2012), with some modifications following Goessen et al. (2022).

2.4. Assembly, quality filtering and SNP callingDNA was digested using the restriction enzymes PstI, NsiI and MspI. Stacks v.2.4 was used to identify loci in the data and call genotypes (https://github.com/enormandeau; Catchen et al., 2013; Rochette et al., 2019). Cutadapt v.1.8.1 was used to remove adapters from raw sequences (Martin, 2011). The process_radtags module in R v.4.2.1 software (R Core Team, 2022) was used to demultiplex the libraries and perform quality trimming on reads of length 125 bp.

Sequenced reads were aligned to the P. tremuloides reference genome (v.1.1; "Potrs01b, " ~480 Mbp of sequence) available from the Populus Genome Integrative Explorer website (http://www.popgenie.org/; Sjödin et al., 2009; Sundell et al., 2015).

Chloroplast, mitochondrial and contaminant scaffolds were removed from the original reference genome. The unwanted scaffolds consisted of 214 sequences and 211, 552 nucleotides, which accounted for 0.06% of the genome. Reads were aligned to the reference genome on the basis of sequence similarity, determined using the Burrows-Wheeler alignment tool, BWA v.0.7.17 (Li and Durbin, 2009). SNPs were then called. The gstacks module was first used to assemble and merge paired-end contigs and call variant sites in the populations and genotypes in each sample (with the argument --max-clipped 0.1). The populations module was then run to filter the data (-p 200, -r 0.01, --vcf, --hwe, --smooth, --fasta-loci) and export it to variant call format (VCF).

For all subsequent analyses, VCFtools v.0.1.14 (Danecek et al., 2011) was used to generate a "final" SNP dataset, from which indels and problematic individuals with > 20% missing data were removed. In addition, SNPs that did not meet the following criteria were filtered out: (i) minimum allele count (MAC) of 2, (ii) minimal depth (minDP) of 10, and (iii) missing rate of higher than 15%.

2.5. Ploidy levels in samplesThe FastPloidy script was used to detect ploidy variation in individuals resulting from filtering. FastPloidy, developed by Goessen et al. (2022), is available at https://github.com/RGoess/Ploidy_detection/blob/main/FastPloidy.R. The correct identification of ploidy levels by the FastPloidy script has already been verified (see also fig. 3 in Goessen et al., 2022) using flow cytometry and microsatellites on 105 individuals provided by Mock et al., (2012). These individuals, along with our material, were part of the dataset used by Goessen et al. (2022).

FastPloidy reads of VCF in R v.4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022) allows: (i) extracting the allele depth for reference and alternative alleles (minimum depth of 18); (ii) dividing the depth of the reference allele by the total depth to obtain the allelic ratio of the reference allele and only retaining heterozygous SNPs (allelic ratio within 0.1–0.9); and (iii) assigning each SNP to a class depending on the value of the allelic ratio (A: 0.273–0.393, B: 0.44–0.56, C: 0.607–0.727, 'Other' would refer to a value anywhere outside the range). Triploids should have a higher allelic ratio, as most SNPs should be found within class A and C, while diploids should include most SNPs in class B, and thus, have a lower ratio. A comparison of FastPloidy and gbs2ploidy was performed to evaluate the efficiency of each (Gompert and Mock, 2017), and a slight advantage in accuracy for assigning ploidy by the FastPloidy package was observed (for more details see Goessen et al., 2022). The population cover (ha) and clonal richness, as well as the relative frequency of diploid and triploid individuals per population were then calculated in order to test the univariate association between polyploidy and bioclimatic and edaphic variables. Since there was probably only one tetraploid individual in the study (see also in Goessen et al., 2022), we merged it with the triploids for all analyses.

2.6. Assessment of clonal richnessThe pairwise Jaccard similarity index (across all SNPs) (Jaccard, 1908) was used to assign an individual to a clone (genotype), and a similarity matrix was constructed using the vcf2Jaccard.py script developed by Rowe (2019) (available at: https://github.com/carol-rowe666/vcf2Jaccard.git). Consequently, samples from the same population with similarities ≥ 0.99 were assigned as belonging to the same clone (Blonder et al., 2021). In subsequent analyses to determine clonal richness within each study site (genotype), the clonal values were multiplied by a correction term (N∕(N1)) (Gregorius, 1978), where N refers to sample size per population.

2.7. Linkage disequilibriumNatural selection, which supports adaptation to local environmental conditions, may increase the overall linkage disequilibrium (LD) caused by differences in allele frequencies between populations when alleles at different loci are favoured (Wright, 1940; Ohta, 1982a, 1982b; Agapow and Burt, 2001; Slatkin, 2008). LD analyses were computed with Tomahawk v.0.7.0 (Klarqvist, 2019; available from https://github.com/mklarqvist/tomahawk). The LD metrics (r2 and D′) were calculated across all pairwise combinations of variant sites by using the following criteria: (i) P (Fisher's exact test/Chi-squared cutoff p-value) = 0.0001 and, (ii) r2 (Pearson's R-squared minimum cut-off value = 0.0001).

2.8. Influence of putative adaptation on Ho, He and FISTo examine the influence of selection on FIS in the natural populations of Populus tremuloides, putative outlier loci in the populations under study were identified using the multivariate method implemented in the pcadapt v.4.1.0 package (Luu et al., 2017) and Latent Factor Mixed Models 2.0 (LFMM2) (Caye et al., 2019) from the LEA package (Gain and François, 2021) of R v.4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022).

Simulations showed that the pcadapt package compares favourably to other genome scanning software (BayeScan, hapflk, OutFLANK, sNMF), particularly in the presence of admixed individuals (data not shown). This method involves: (i) identification of outlier loci in admixed or continuous populations, (ii) determination of the population structure by principal component analysis (PCA) (rather than classifying individuals in admixed or continuous populations), and (iii) identification of SNPs under putative selection as those that are strongly correlated with population structure. The following criteria were applied: (i) exclusion of loci with global MAF < 0.05, (ii) an optimal K = 2 (according to a scree plot (Jackson, 1993; Fig. S1) and (iii) identification of outliers for different individuals by the significance of Mahalanobis distances for each SNP, using a Benjamini-Hochberg (HB) correction for a false discovery rate (FDR) of p < 0.05 (Thissen et al., 2002).

Since LFMM2 does not allow missing data, imputation was carried out with the impute (.) command of the R package "LEA" (Frichot and François, 2015). This imputation method replaces missing genotypes with predicted genotypes based on the population structure inference made in the snmf function of the package (Gain and François, 2021). We decided to run LFMM2 with two latent factors (according to a scree plot Fig. S1). The HB correction was used to adjust false-positive rates. SNPs with a corrected p value < 0.05 were retained.

The results of pcadapt and LFMM2 were processed using VCFtools to generate two VCF files, one for the putatively neutral SNPs and the other one for the putatively outlier SNPs. Only SNPs that were found to be putatively outlier SNPs by both methods and were also not identified as deleterious SNPs (more details in section 2.9.) were used further. Each dataset was analyzed separately to calculate values of observed heterozygosity (Ho), expected heterozygosity (He) and FIS in the R package hierfstat (Goudet and Jombart, 2022), and to test univariate associations with bioclimatic and edaphic variables, population cover and clonal richness. Given that FIS = 1 – Ho/He (Wright, 1969), FIS and He are positively correlated when Ho is constant.

2.9. Gene annotation and association of deleterious mutations with heterozygous excess and clonal reproductionGene annotation was performed to categorize non-synonymous, synonymous and deleterious SNPs based on their location and impact using SnpEff v.5.2c and Sequences Ontology (SO) (http://www.sequenceontology.org/) for accurately annotating genetic sequences. The deleterious SNPs included the SO categories, in particular: (i) missense mutations with moderate impact, (ii) SNPs that cause the loss or disruption of the start codon of a gene (start_lost), (iii) SNPs that lead to the formation of a premature stop codon (stop_gained), (iv) SNPs that have both stop-gained and splice region effects (stop_gained & splice_region_variants), (v) SNPs that cause the loss of a stop codon (stop_lost), and finally (vi) SNPs that have both stop-loss and splice region effects (stop_lost & splice_region_variants). The SNP categories (ii) to (vi) are classified as high impact (Cingolani et al., 2012). To construct the input database for this gene annotation, we used the reference genome of Populus tremuloides, available at https://plantgenie.org/FTP?dir=Data%2FPlantGenIE%2FPopulus_tremuloides%2Fv1.1.

By comparing the accumulation of heterozygous deleterious SNPs due to heterozygous excess and clonal reproduction, these findings helped to decipher not only the causes but also the consequences of excessive heterozygosity.

2.10. Estimation of edaphic variablesFor determination of 25 soil variables, four subsamples of 500 g of soil at a depth of 0–15 cm were randomly collected in each population. The subsamples were then mixed to produce a sample of 2 kg for each population. The techniques used to estimate the variables are described below. The concentrations of K+ (ppm), Ca2+ (ppm), Mg2+ (ppm), Na+ (ppm), Cu2+ (ppm), Fe3+ (ppm), Mn+2 (ppm), Zn2+ (ppm), texture (relative proportion of sand, silt, and clay) and pH (CaCl2 0.01 M) in each soil sample were determined using the methods described by Castellanos et al. (1999). The concentration of P (kg/ha) was determined using the method detailed by Olsen et al. (1954). The relative organic matter content (%OM) was obtained by the León and Aguilar (1987) method, and that of nitrates (NO3-) (kg/ha) by the Baker (1967) method. Electrical conductivity (CE) (dS/m) was determined according to Vázquez-Alarcón and Aguilar-Noh (2020). The hydraulic conductivity (HC) (cm/h) and saturation percentage (Sat%) were determined as described by Mualem (1976) and Herbert (1992), respectively. Finally, the relative proportions (%) of H+, Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, Na+ and other bases (%OB) were obtained by calculating the cation exchange capacity (meq 100 g soil) (CEC) using the ammonium acetate method (pH 8.5).

2.11. Estimation of bioclimatic variablesThe Rehfeldt's (2006) climate model was used to estimate 22 bioclimatic variables in each sampling site. The model is based on the Thin Plate Spline (TPS) method (Hutchinson, 1991) and has previously been used for climate-change research in Mexico (Sáenz-Romero et al., 2010). The estimations of this model are based on the reports from more than 1700 Mexican weather stations for the period 1961–1990, estimating the standardized monthly mean values of minimum and maximum temperatures and precipitation (Table S1). The geographic coordinates (latitude, longitude and elevation) of each site were uploaded to a public database (available at http://forest.moscowfsl.wsu.edu/climate/[accessed 22 October 2023]) to obtain point estimates of the bioclimatic variables.

2.12. Statistical analysisThe non-parametric post-hoc Kruskal Wallis test (Tukey and Kramer method) (Kruskal and Wallis, 1952; Sachs, 2013) was used to test for any statistically significant differences in the medians of Ho, He and FIS between SNP datasets (Table S3). The tests were performed in R v.4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022), using the PMCMR package (Pohlert, 2014).

Once the population cover, relative frequency of diploids and triploids, clonal richness, number of heterozygous deleterious SNPs, bioclimatic and edaphic variables and Ho, He and FIS were calculated for each sampling site, the degrees of association (measured by the Spearman's rs) and the corresponding p-values were determined with the fuzzySim package (Barbosa, 2015).

To test the potential multivariate associations between both FIS and ploidy level and the bioclimatic and edaphic variables, population cover and clonal richness, only the non-collinear variables and with an absolute value of the nonparametric Spearman correlation coefficient lower than 0.7 were selected for modelling eight machine learning algorithms (MLM), all including cross-validation (CV). The modelling methods used were: (i) Random Forest (rf), (ii) Regularized Random Forest (RRF), (iii) Tree Models from Genetic Algorithms (evtree), (iv) Multi-Layer Perceptron (mlpWeightDecay), (v) Bayesian Regularized Neural Networks (brnn), (vi) Model Averaged Neural Network (avNNet), (vii) Linear Regression (lm), and (viii) Neural Network (nnet). These methods were applied using the caret package together with the train function (Venables and Ripley, 1999; Williams et al., 2015; http://topepo.github.io/caret/index.html) in R software. The models were tested by 10-fold cross-validation, with 30 repetitions. The goodness-of-fit of the regression models was determined by the mean square error (MSE), root mean square error (RMSE) and the (pseudo) coefficient of determination (R2). Analysis was performed using the FIS values separately for neutral, outlier and all SNPs.

Bioclimatic and edaphic variables, population cover, and clonal richness were tested regarding their conditional importance (i.e., considering all other variables studied) in predicting FIS (all SNPs, outlier SNPs and neutral SNPs) and ploidy levels, considering the following criteria: (i) the multivariate association between FIS and ploidy levels and the bioclimatic and edaphic variables, population cover and clonal richness; and (ii) the multivariate association between FIS and ploidy levels and the bioclimatic and edaphic variables and the population cover. This procedure was performed using the cforest algorithm in the random forest implementation in the party package (Strobl et al., 2009) in R v.4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022). The packages "ggpubr" (Kassambara, 2023) and "ggplot 2" (Wickham, 2016) were used in R v.4.2.1 to display associations graphically.

3. Results 3.1. SNP filtering, ploidy levels, clonal richness and pattern of linkage disequilibriumAfter sequencing, SNP calling and filtering for quality using Stacks v.2.4, and script available in Stacks workflow, the raw VCF file contained 1, 556, 064 singleton SNPs with an average depth of 16.7 per SNP and 932 individuals. After SNP filtering, 36, 810 SNPs and 809 individuals from 91 populations were retained for subsequent analyses. The histogram of Ho is shown in Fig. 2.

FastPloidy script identified 718 diploids and 91 triploids. A total of 293 unique genotypes were identified from among the 809 individuals (Table S2).

The distribution pattern of linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2) values between pairs of SNPs (in a total of 36, 810 SNPs) ranged from 0.0 to 1.0. The pairwise mean values of r2 decreased rapidly with increasing physical distance ≥10 kbp. The overall mean LD value across the genome, 0.46, supports the occurrence of selection (Fig. S2).

3.2. Influence of putative adaptation on Ho, He and FISPcadapt and LFMM2 analyses identified 183 potential adaptive outlier SNPs (optimal K = 2 according to a skew plot; Fig. S1), excluding 37 of those outliers that were found to be deleterious (Fig. S4). The potential adaptive outlier SNPs without the detected deleterious SNPs (146 SNPs) were treated separately from the remaining (neutral) 36, 627 SNPs for estimating genetic diversity and performing correlations with the environment and with individual clonality (Tables S5, S6 and S7). Significance of the associations between SNPs and environmental factors across the genome are shown in a Manhattan plot (Fig. S3).

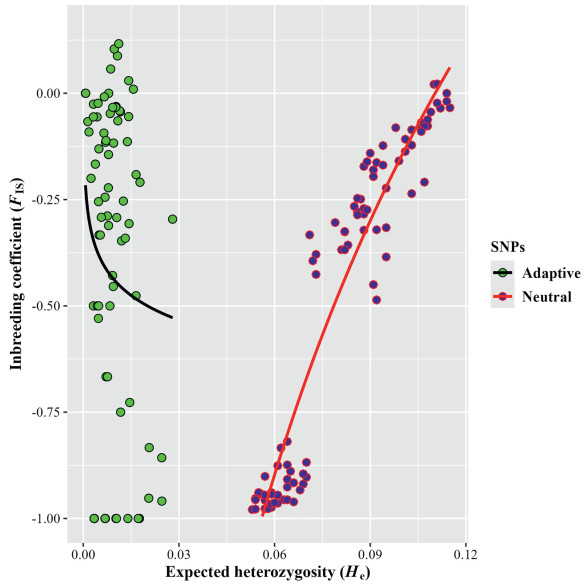

The non-parametric post-hoc Kruskal Wallis test (Tukey and Kramer method) revealed significant differences between the medians of the 36, 627 neutral SNPs and the 146 outlier SNPs for Ho (p < 0.0000001), He (p < 0.0000001), except for FIS (p = 0.54). All He values using the outlier SNPs were much smaller than those using the neutral SNPs (Fig. 3).

|

| Fig. 3 Comparison of expected heterozygosity (He) vs. inbreeding coefficient (FIS) with neutral vs. 146 outlier SNPs (excluding deleterious SNPs within outlier SNPs). |

Spearman's correlation showed that although Ho and He were not significantly correlated for neutral SNPs (rs = 0.02, p = 0.83), a strong positive correlation was observed between Ho and He for the 146 outlier SNPs (rs = 0.89, p < 0.0000001). There was also a positive, significant association between FIS (both for all neutral SNPs and the 146 outlier SNPs) and clonal richness in the 91 populations of P. tremuloides (rs = 0.88 and 0.79, p < 0.0000001). By contrast, ploidy level was negatively correlated (not significantly) with clonal richness (rs = −0.10, p = 0.36). When all neutral SNPs were considered, clonal richness was negatively correlated with Ho (rs = −0.23, p = 0.03) but positively correlated with He (rs = 0.87, p < 0.000001). When we analysed only the outlier SNPs, clonal richness again was negatively correlated with Ho (rs = −0.29, p = 0.01) and positively correlated with He, however, this positive correlation was not significant (rs = 0.05, p = 0.65).

3.3. Associations of deleterious mutations with heterozygous excess and clonal reproductionOut of the total 36, 810 filtered SNPs, 28, 998 were detected in gene regions, 3926 in intron regions, and 3886 in intergenic regions according to the gene annotation. In total, 5697 SNPs were classified as deleterious mutations (Fig. S4).

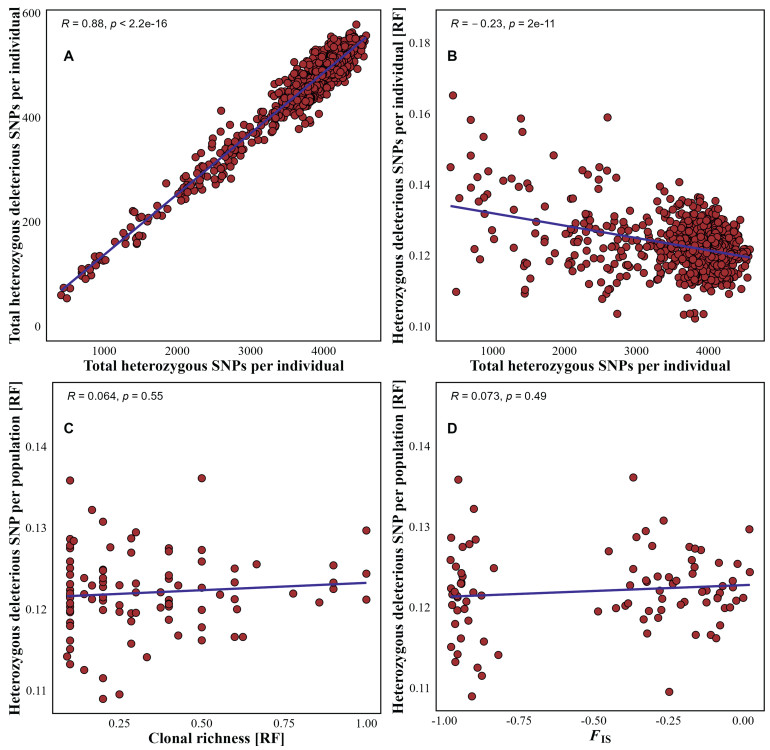

As the total heterozygous SNPs per individual increased, the total heterozygous deleterious SNPs per individual also increased (rs = 0.88, p < 0.00000001), but the relative proportion of total heterozygous SNPs per individual significantly decreased (rs = −0.23, p < 0.00000001). At the population level (with Ho per population remaining almost constant), there were no significant correlations between the relative proportion of total heterozygous deleterious SNPs and either clonal richness or FIS. At the population level, the relative proportion of heterozygous deleterious SNPs in the total number of heterozygotic SNPs in clones varied from 0.11 to 0.14. This variation was slightly greater than in populations with higher clonal richness (Fig. 4).

|

| Fig. 4 Relationships between: (A) total heterozygous SNPs and total heterozygous deleterious SNPs per Populus tremuloides individual, (B) total heterozygous SNPs and relative proportion of total heterozygous deleterious SNPs per P. tremuloides individual, (C) relative clonal richness (clonal richness per sample) and relative proportion of total heterozygous deleterious SNPs per P. tremuloides population, and (D) inbreeding coefficient of a population (FIS) and relative proportion of total heterozygous deleterious SNPs per P. tremuloides population; RF = relative frequency. |

By selecting variables classified as non-collinear, according to the absolute value of the nonparametric Spearman correlation coefficient (ǀrsǀ) < 0.7, population cover (Table S1), clonal richness (Table S2), five bioclimatic variables (Table S3) and eighteen edaphic variables (Table S4) were retained.

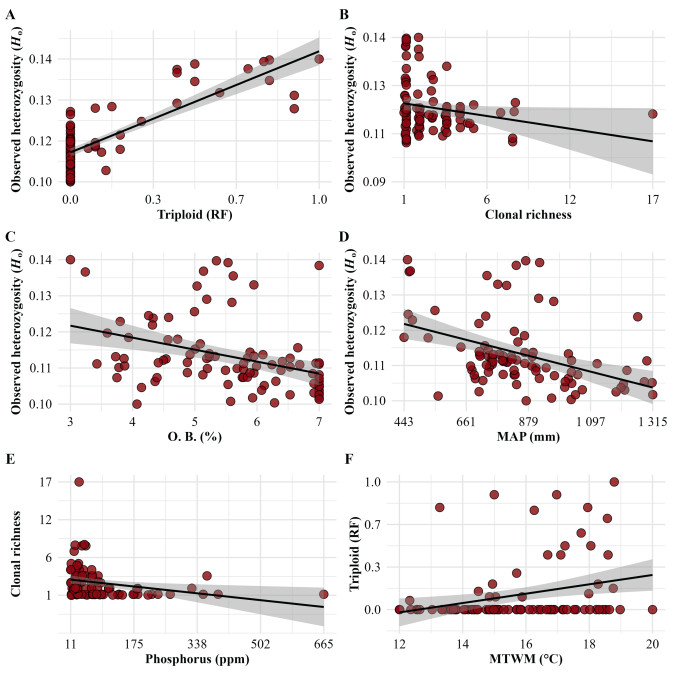

Using all filtered SNPs, Spearman's correlation showed statistically significant associations of Ho with relative proportion of other bases in cation exchange capacity (%) in the soil (rs = −0.45, p = 0.000008), mean annual precipitation (mm) (rs = −0.45, p = 0.000008), mean temperature in the warmest month (℃) (rs = +0.41, p = 0.0001), degree-days below 0 ℃ (DD0) (rs = +0.29, p = 0.0046) and relative frequency of triploids (rs = +0.60, p < 0.000000001) at the population level (91 populations). Using the outlier SNPs, significant associations were also found between Ho and the above-mentioned variables (p < 0.05), except for Ho vs. DD0 (p = 0.44). There were also significant correlations of clonal richness with phosphorus concentration in the soil (ppm) (rs = −0.35, p = 0.0006), clay proportion in the soil (%) (rs = +0.31, p = 0.0032) and winter precipitation (mm) (rs = −0.27, p = 0.0087) (Fig. 5). The relative frequency of triploids was significantly associated with mean temperature in the warmest month (rs = +0.29, p = 0.0046), DD0 (rs = +0.27, p = 0.0098) (Fig. 5) and winter precipitation (rs = +0.26, p = 0.01). However, statistical associations of Ho, clonal richness or the relative proportion of triploids with geographic longitude or latitude were not observed (Fig. 1).

|

| Fig. 5 Relationship between: (A) relative proportion of triploid individuals and observed heterozygosity (Ho) (rs = +0.60, p < 0.000000001), (B) clonal richness and Ho (rs = −0.23, p = 0.028), (C) relative proportion of other bases in cation exchange capacity (O.B., %) in the soil and Ho (rs = −0.45, p = 0.000008), (D) mean annual precipitation (MAP, mm) and Ho (rs = −0.45, p = 0.000008), (E) phosphorus concentration in the soil (ppm) and clonal richness (rs = −0.35, p = 0.0006), and (F) mean temperature in the warmest month (MTWM, ℃) and relative proportion of triploid individuals (rs = +0.29, p = 0.005) in 91 Mexican Populus tremuloides populations under study; mean values (black lines) and the 95% confidence level intervals for predictions (grey area) are based on linear models (LM), using all filtered SNPs. |

Using the non-collinear bioclimatic and edaphic variables, population cover and clonal richness, the Regularized Random Forest (RRF) algorithm proved to be the best for estimating the spatial pattern of FIS (from the dataset with neutral SNPs) in Populus tremuloides populations, producing a pseudo R2 of 0.95 and a RMSE of 0.08 (Table 1). The results obtained with the cforest random forest algorithm showed that clonal richness was strongly associated with FIS (with 70.6% of all included variables), population cover (with 11.4%) and phosphorus concentration in the soil (with 7.7%). Using the 146 outlier SNPs, RRF was the best for estimating FIS, with a pseudo R2 of 0.65 and RMSE of 0.23) (Table 2). In this case, the cforest results obtained indicated that the variables most closely associated with FIS were mean temperature of the warmest month (with 34.6%), relative proportion of Mg in the cation exchange capacity (11.1%), and Julian date of the first freezing date of autumn (8.4%). However, including the 37 deleterious SNPs together with the outlier SNPs resulted in an R2 of 0.76 and RMSE of 0.19. Here, the cforest results were very similar to the findings using the neutral SNPs.

| FIS vs Bioclimatic, edaphic, Population size and clonal richness variables | Algorithm | RMSE | R2 | MAE |

| ~ map + mtwm + fday + dd0 + winp + pH + CE + CaCO3 + OM + Density + Silt + Clay + P + Fe + Mn + Zn + Cu + meq_Mg + meq_Na + CIC + per_Mg + per_K + per_ob + Pop_cover + R_clonal | RRF | 0.084 | 0.945 | 0.055 |

| evtree | 0.089 | 0.938 | 0.062 | |

| rf | 0.090 | 0.937 | 0.059 | |

| avNNet | 0.170 | 0.804 | 0.121 | |

| mlpWeightDecay | 0.183 | 0.771 | 0.132 | |

| brnn | 0.260 | 0.548 | 0.213 | |

| lm | 0.347 | 0.413 | 0.263 | |

| nnet | 0.617 | 0.069 | 0.495 | |

| Note: map = Mean annual precipitation (mm); mtwm = Mean temperature in the warmest month (℃); fday = Julian date of the first freezing date of Autumn; dd0 = Degreedays below 0 ℃ (based on mean monthly temperature); winp = Winter precipitation (Nov + Dec + Jan + Feb) (mm); pH = pH; CE = Electric conductivity (dSmol); CaCO3 = Calcium carbonate (%); OM = Organic material (%); Density = Density (gr/cm3); Silt = Silt (%); Clay = Clay (%); P = Phosphorus (ppm); Fe = Iron (ppm); Mn = Manganese (ppm); Zn = Zinc (ppm); Cu = Copper (ppm); meq_Mg = Magnesium milliequivalent; meq_Na = Sodium milliequivalent; CIC = Cation exchange capacity (meq/100 g soil); per_Mg = Relative proportion of Mg in the cation exchange capacity (%); per_K = Relative proportion of K in the cation exchange capacity (%); per_ob = Rel. Proportion of other bases in the cation exchange capacity (CEC; meq/100g soil) (%); Pop_cover = Population cover (ha); R_clonal = Clonal richness. | ||||

| FIS vs Bioclimatic, edaphic, Population size and clonal richness variables | Algorithm | RMSE | R2 | MAE |

| ~ map + mtwm + fday + dd0 + winp + pH + CE + CaCO3 + OM + Density + Silt + Clay + P + Fe + Mn + Zn + Cu + meq_Mg + meq_Na + CIC + per_Mg + per_K + per_ob + Pop_cover + R_clonal | RRF | 0.234 | 0.652 | 0.164 |

| rf | 0.236 | 0.653 | 0.166 | |

| evtree | 0.263 | 0.569 | 0.201 | |

| mlpWeightDecay | 0.361 | 0.259 | 0.300 | |

| brnn | 0.368 | 0.235 | 0.299 | |

| avNNet | 0.382 | 0.282 | 0.277 | |

| lm | 0.476 | 0.153 | 0.354 | |

| nnet | 0.572 | 0.130 | 0.426 | |

| Note: Abbreviations used for variables are given in Table 1. | ||||

When using the bioclimatic and soil variables and population cover (i.e., excluding clonal richness), RRF proved to be the best model for estimating FIS (from the dataset with neutral SNPs) in the populations, producing a pseudo R2 of 0.35 and RMSE of 0.30 (Table S7). In this case, the cforest results obtained showed that the variables most closely associated with FIS were population cover (40.6%), soil phosphorus content (18.5%), and winter precipitation (12.7%). Using the 146 outlier SNPs, RRF was found to be the best model for estimating FIS, with a pseudo R2 of 0.28 and RMSE of 0.34) (Table S8). Here, the cforest results obtained indicated that the variables most closely correlated with FIS were mean temperature of the warmest month (with 27.6%), relative proportion of Mg in the cation exchange capacity (14.6%), and Julian date of the first freezing date of autumn (8.4%). Including the deleterious with the neutral outlier SNPs together gave an R2 of 0.38 and RMSE of 0.30.

The Tree Models algorithm in Genetic Algorithms (evtree) was the best model for estimating the associations between ploidy level and bioclimatic and edaphic variables, population cover and clonal richness, yielding a pseudo R2 of 0.26 and RMSE of 0.24 (Table 3). Using the outlier SNPs, Regularized Random Forest (RRF) had the best model for estimating FIS, with a pseudo R2 of 0.30 and RMSE of 0.33. The results obtained with cforest showed that the variables most closely (and positively) associated with ploidy level were winter precipitation (39.6%), soil phosphorus content (18.4%) and relative proportion of Mg2+ in CEC (16.8%).

| Ploidy level vs bioclimatic and edaphic variables, population cover and clonal richness | Algorithm | RMSE | R2 | MAE |

| ~ map + mtwm + fday + dd0 + winp + pH + CE + CaCO3 + OM + Density + Silt + Clay + P + Fe + Mn + Zn + Cu + meq_Mg + meq_Na + CIC + per_Mg + per_K + per_ob + Pop_cover + R_clonal | evtree | 0.224 | 0.258 | 0.150 |

| RRF | 0.233 | 0.161 | 0.164 | |

| rf | 0.234 | 0.137 | 0.166 | |

| nnet | 0.235 | 0.209 | 0.174 | |

| mlpWeightDecay | 0.241 | 0.181 | 0.156 | |

| brnn | 0.243 | 0.217 | 0.155 | |

| lm | 0.255 | 0.153 | 0.182 | |

| avNNet | 0.265 | 0.136 | 0.181 | |

| Note: Abbreviations used for variables are given in Table 1. | ||||

This study found that the values of the inbreeding coefficient (FIS) in Mexican populations of Populus tremuloides were mostly negative (Table S2). Comparing FIS levels between neutral and outlier SNPs in 91 populations of P. tremuloides showed that the median of putative outlier SNPs was not significantly larger (Fig. 3). It can be assumed that: (i) the negative FIS can at first be attributed to a bottleneck effect in the populations studied, with a single allele retained for most loci, while the less common alleles represent more recent mutations (Cole, 2005); (ii) later processes of genetic drift led to accumulation of almost always recessive alleles derived from mutation and absence of recombination in small populations of trees with no gene flow between individuals of the same population or between populations; and (iii) natural selection forces subsequently acted to eliminate these recessive alleles and preserve rare beneficial alleles (Fig. 3), resulting in highly heterozygous populations and maintaining negative FIS values (see the Meselson effect; Judson and Normark, 1996; Stoeckel and Masson, 2014). Genetic drift processes (claim (ii)) are supported by the strong positive correlation found between the total number of heterozygous SNPs per individual and heterozygous deleterious SNPs per individual. The negative relationship between the relative proportion of heterozygous deleterious SNPs per individual and the total number of heterozygous SNPs per individual (Fig. 4) are consistent with the action of natural selection forces (claim (iii)). Both conclusions correspond with the findings of low variation of the minor relative proportion of heterozygous deleterious SNPs independent of FIS and clonal richness at the population level. These two results are in agreement if it is assumed that only a certain upper proportion of deleterious SNPs ensures the fitness of the populations and that only the fittest individuals could be found.

After constructing a population genetics model based on genotypic states in a finite population (less than 400 individuals) with mutations, Stoeckel and Masson (2014) concluded that reproduction by asexuality increased the expected allelic diversity within populations, as indicated by a more negative FIS index, compared to similar, fully sexual populations. Asexuality fixes heritability and genetic drift at the genotypic level and preserves ancestral genetic states against drift, ultimately reducing allelic identities within individuals.

There is a lack of a significant correlation between Ho and He for neutral SNPs, in contrast to the strong positive and significant correlation between Ho and He for outlier SNPs. Moreover, Ho was nearly always larger than He for neutral and also for outlier SNPs, and He for outlier SNPs was much smaller than He for neutral SNPs (Fig. 3). The FIS association of the outlier SNPs with the environmental variables studied was higher than those of the neutral SNPs with these variables. These findings suggest that these outlier SNPs found in Mexican populations of Populus tremuloides may be primarily subject to balancing selection, in which heterozygous genotypes have a fitness advantage over homozygous genotypes, resulting in multiple alleles being maintained in the population due to their adaptive advantages in different environments (Delph and Kelly, 2014). This contrasts with a whole-genome resequencing study from Canada and the USA by Wang et al. (2016), in which purifying and positive selection strongly affected the patterns of nucleotide polymorphism at linked neutral sites in P. tremuloides, P. tremula and P. trichocarpa.

By analyzing polymorphic enzyme loci, Jelinski and Cheliak (1992) also observed a substantial excess of heterozygotes in Populus tremuloides (FIS of −0.10), attributing this result to the rather dry climate in the western range of the species, which limits seed germination, and results in predominantly asexual reproduction through the formation of adventitious shoots on the roots. Cheliak and Dancik (1982) also obtained a FIS of −0.24 for seven locations in Alberta, Canada, indicating that asexual propagation could increase genetic diversity by facilitating the accumulation of mutations in offspring. By contrast, Latutrie et al. (2016) detected recent bottlenecks with an excess of heterozygotes in six populations distributed in the northwestern range of aspen distribution between Manitoba and Alaska.

Negative FIS values have also recently been reported in other species of the genus Populus, e.g., Populus yunnanensis (FIS = −0.65; Zhou et al., 2020) and Populus laurifolia (FIS = −0.11; Wiehle et al., 2016), according to results based on the presence of high-frequency gene flow. On the other hand, after performing a mutation drift equilibrium test, Wu et al. (2020) reported significant heterozygosity excess (FIS = −0.50) in Populus wulianensis, probably because of recently experienced bottleneck effects in the study populations. Similar results were observed in other forest tree species, e.g., Prunus avium L. (Stoeckel et al., 2006) and Tilia cordata Mill. (Erichsen et al., 2019).

While polyploidy is frequently observed in Populus tremuloides (Zhu et al., 1998; Mock et al., 2008), we reject the hypothesis that the ploidy level affected FIS (rs = −0.07, p = 0.53), which contradicts the claims made by Krieger and Keller (1998) and Ridout (2000). This level of ploidy has no significant effect on the ratio between Ho and He, which is crucial for FIS (Wright, 1969). Although triploids are thought to reproduce almost exclusively by asexual methods (Mable, 2004; Baldwin and Husband, 2013; Chinone et al., 2014) clonal richness was not significantly lower (rs = −0.10, p = 0.36).

A large number of clones was detected in this study (36% of the individuals). Similar results were reported by Goessen et al. (2022) for the entire Mexican aspen cluster (not at the population level) using a large part of our dataset. Our results provide evidence that asexual (clonal) reproduction is an indicator of extremely negative FIS occurring within the study populations based on the strong association between these variables (rs = 0.79–0.88, p < 0.0000001), as also discussed by Cheliak and Dancik (1982) and Jelinski and Cheliak (1992). Therefore, it can be inferred that clonal growth maintains or even increases the levels of heterozygosity and adaptive capacity by mutation over generations (Judson and Normark, 1996; Welch and Meselson, 2000; Delmotte et al., 2002).

In addition, we detected a clear influence of bioclimatic and edaphic variables on the prediction of FIS and ploidy level of putatively neutral and outlier SNPs (Table 1, Table 2, S7 and S8). We can confirm that FIS (from the dataset with all SNPs) was higher in populations with lower soil phosphorus content and less winter precipitation, but that triploids occurred in locations with higher winter precipitation. Therefore, our study, which only included 23 environmental variables, did not support the general expectation that polyploids should display a greater capacity than diploids to adapt to a wide range of conditions (Černá and Münzbergová, 2015). Our results contradict our hypothesis and the findings reported by Goessen et al. (2022), who analyzed Mexican populations as a single cluster. Thus, our results seem to be more consistent with those reported by Benson and Einspahr (1967) and Greer et al. (2018) as triploid individuals have more resource-oriented life histories, and may have a higher risk of induced mortality in drier environments (Dixon and De Wald, 2015; Blonder et al., 2021, 2022). Hence, the wide geographic range of the quaking aspen (Wang et al., 2016) implies that natural populations grow in diverse environmental conditions. This, in turn, leads to local adaptation (Savolainen et al., 2007; Neale and Kremer, 2011; Aitken and Whitlock, 2013). Thus, genotypes that originate from a particular habitat exhibit greater fitness in that specific habitat than genotypes from other habitats (Kawecki and Ebert, 2004), which indicates strong local adaptation. This highlights that adaptation processes rely on the emergence of advantageous mutations, which are then either fixed or maintained at an intermediate frequency through natural selection (Peischl and Kirkpatrick, 2012). This has also been observed in P. tremula, in which Wang et al. (2018) detected a locus (PtFT2) associated with an adaptive mutation from the post-glacial recolonization of northern Scandinavia and suggested that strong genetic drift at the front of the expansion range caused surfing of the adaptive allele in the newly colonized regions (Klopfstein et al., 2006; Excoffier and Ray, 2008).

In our study, the Ho for putative neutral and outlier SNPs, was positively and significantly correlated with clonal proliferation. This finding supports the claim of the possible presence of a Meselson effect, because accumulation of heterozygous loci was observed in populations with fewer genotypes and in which asexual reproduction was more common and, therefore, counteracted the inbreeding effect in small and isolated populations. However, the simultaneous reduction in genetic diversity (He) overwhelmed this positive effect and could probably have an overall negative impact on the survival of the species in Mexico from a genetic point of view (Leimu et al., 2006; Aitken and Whitlock, 2013). The Meselson effect is generally considered a strong indicator of long-term evolution under strict asexuality (Hartfield, 2016; Brandt et al., 2021); however, this phenomenon has also been shown to occur in relatively recent lineages, of less than 100, 000 years of age (Pellino et al., 2013). Some researchers have suggested that quaking aspen clones may be millions of years old and have survived several glacial cycles (Barnes, 1966; Kemperman and Barnes, 1976; Mitton and Grant, 1996).

Asexual reproduction in Mexican Populus tremuloides may play a contributing role in the ability of this species to survive under extreme ecological conditions (Goessen et al., 2022). For example, quaking aspen has developed physiological and ecological adaptations to survive and proliferate in diverse ecological environments, sometimes even extreme environments, such as the mountainous regions of the Sierra Madre Occidental in Mexico and areas experiencing severe drought (Ding et al., 2017; Rogers et al., 2020). Ding et al. (2017) considered the Sierra Madre mountain range in northeastern Mexico one of the few locations where quaking aspen populations show a moderate to high probability of surviving multiple glaciations.

5. ConclusionsThis study contributes to a better understanding of the survival and adaptation to changing environmental conditions of natural clonal plant populations, especially of Populus tremuloides, one of the most widespread and ecologically important tree species in the Northern Hemisphere.

However, further research on the Mexican populations of Populus tremuloides is required, given the importance of obtaining information from natural populations located at the border of the general climatic niche of the species, where projections are not at all encouraging: (i) because global climate change is expected to transform the distribution of large numbers of forest trees (Noss, 2001), and (ii) it is estimated that about 26% of the current geographical distribution will no longer be suitable for quaking aspen by 2060, and that the loss of habitat will be particularly marked in the southern distribution range of the species, where the Mexican populations are distributed (Worrall et al., 2013). It has been suggested that these Mexican populations have developed strategies for surviving adverse conditions that are unique in the plant kingdom, in contrast to findings on populations of the same species in the southwestern USA (Crouch et al., 2023). It is important to continue exploring these adaptive mechanisms, as this would enable prediction of the impacts of climate change, which could be helpful for designing effective mitigation strategies.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank the Mexican Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT) for the financial support provided to the first author to carry out his training in the Institutional Doctoral Program in Agricultural and Forestry Sciences (PIDCAF-UJED) with Scholarship No. 334852 and financial support with agreement number CONACYT-FRQ-2016: 279459 for the project "Genome-wide scans for detecting adaptation to climate and soil in Populus tremuloides as the most widely distributed tree species in North América". Dr. Jesús M. Olivas-García assisted in the sampling in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, and Katrin Groppe, Thünen Institute of Forest Genetics, Germany, provided excellent lab work. The Emerging Leaders of the Americas Program (ELAP) of the Government of Canada awarded a scholarship and the Institute of Integrative and Systems Biology (IBIS) of Laval University allowed the use of its campus and contributed to the training of the first author.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Javier Hernández-Velasco: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. José Ciro Hernández-Díaz: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Sergio Leonel Simental-Rodríguez: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Juan P. Jaramillo-Correa: Writing – review & editing, Resources. David S. Gernandt: Writing – review & editing, Resources. José Jesús Vargas-Hernández: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Ilga Porth: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. Roos Goessen: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. M. Socorro González-Elizondo: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Matthias Fladung: Writing – review & editing. Cuauhtémoc Sáenz-Romero: Writing – review & editing, Resources. José Guadalupe Martínez-Ávalos: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Artemio Carrillo-Parra: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Eduardo Mendoza-Maya: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Arnulfo Blanco-García: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Christian Wehenkel: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Data availability

A filtered variant of the SNP file used for the population genomic analyses has been deposited in the Dryad repository under the accession doi: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.ttdz08m82. Scripts used for the analyses are available at https://github.com/JavierHdz88/Causes-of-heterozygosity-excess.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no competing interest to declare.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2024.12.006.

Agapow, P.M., Burt, A., 2001. Indices of multilocus linkage disequilibrium. Mol. Ecol. Notes, 1: 101-102. DOI:10.1046/j.1471-8278.2000.00014.x |

Aitken, S.N., Whitlock, M.C., 2013. Assisted gene flow to facilitate local adaptation to climate change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst., 44: 367-388. DOI:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110512-135747 |

Baker, A.S., 1967. Colorimetric determination of nitrate in soil and plant extracts with brucine. J. Agric. Food Chem., 15: 802-806. DOI:10.1021/jf60153a004 |

Baldwin, S.J., Husband, B.C., 2013. The association between polyploidy and clonal reproduction in diploid and tetraploid Chamerion angustifolium. Mol. Ecol., 22: 1806-1819. DOI:10.1111/mec.12217 |

Balloux, F., Amos, W., Coulson, T., 2004. Does heterozygosity estimate inbreeding in real populations?. Mol. Ecol., 13: 3021-3031. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02318.x |

Barbosa, A.M., 2015. fuzzySim: applying fuzzy logic to binary similarity indices in ecology. Methods Ecol. Evol., 6: 853-858. DOI:10.1111/2041-210X.12372 |

Barnes, B.V., 1966. The clonal growth habit of American aspens. Ecology, 47: 439-447. DOI:10.2307/1932983 |

Benson, M.K., Einspahr, D.W., 1967. Early growth of diploid, triploid and triploid hybrid aspen. For. Sci., 13: 150-155. DOI:10.1093/forestscience/13.2.150 |

Blonder, B., Graae, B.J., Greer, B., et al., 2020. Remote sensing of ploidy level in quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx. ). J. Ecol., 108: 175-188. DOI:10.1111/1365-2745.13296 |

Blonder, B., Ray, C.A., Walton, J.A., et al., 2021. Cytotype and genotype predict mortality and recruitment in Colorado quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). Ecol. Appl., 31: e02438. DOI:10.1002/eap.2438 |

Blonder, B., Brodrick, P.G., Walton, J.A., 2022. Remote sensing of cytotype and its consequences for canopy damage in quaking aspen. Global Change Biol., 28: 2491-2504. DOI:10.1111/gcb.16064 |

Brandt, A., Van, P.T., Bluhm, C., et al., 2021. Haplotype divergence supports long-term asexuality in the oribatid mite Oppiella nova. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 118: e2101485118. DOI:10.1073/pnas.2101485118 |

Callahan, C.M., Rowe, C.A., Ryel, R.J., et al., 2013. Continental-scale assessment of genetic diversity and population structure in quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). J. Biogeogr., 40: 1780-1791. DOI:10.1111/jbi.12115 |

Castellanos, J.Z., Uvalle-Bueno, J.X., Aguilar-Santelises, A., 1999. Memoria del curso sobre interpretación de análisis de suelos, aguas agrícolas, plantas y ECP. Mexico: Instituto para la Innovación Tecnológica en la Agricultura: 188. |

Catchen, J., Hohenlohe, P.A., Bassham, S., et al., 2013. Stacks: an analysis tool set for population genomics. Mol. Ecol., 22: 3124-3140. DOI:10.1111/mec.12354 |

Caye, K., Jumentier, B., Lepeule, J., et al., 2019. LFMM 2: fast and accurate inference of gene-environment associations in genome-wide studies. Mol. Biol. Evol., 36: 852-860. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msz008 |

Černá, L., Münzbergová, Z., 2015. Conditions in home and transplant soils have differential effects on the performance of diploid and allotetraploid Anthericum species. PLoS One, 10: e0116992. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0116992 |

Charlesworth, D., Charlesworth, B., 1987. Inbreeding depression and its evolutionary consequences. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst., 18: 237-268. DOI:10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.001321 |

Cheliak, W.M., Dancik, B.P., 1982. Genic diversity of natural populations of a clone-forming tree Populus tremuloides. Can. J. Genet. Cytol., 24: 611-616. DOI:10.1139/g82-065 |

Chinone, A., Nodono, H., Matsumoto, M., 2014. Triploid planarian reproduces truly bisexually with euploid gametes produced through a different meiotic system between sex. Chromosoma, 123: 265-272. DOI:10.1007/s00412-013-0449-2 |

Cingolani, P., Platts, A., Wang, L.L., et al., 2012. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly, 6: 80-92. DOI:10.4161/fly.19695 |

Cole, C.T., 2005. Allelic and population variation of microsatellite loci in aspen (Populus tremuloides). New Phytol., 167: 155-164. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01423.x |

Crouch, C.D., Rogers, P.C., Moore, M.M., et al., 2023. Building ecosystem resilience and adaptive capacity: a systematic review of aspen ecology and management in the Southwest. For. Sci., 69: 334-354. DOI:10.1093/forsci/fxad004 |

Crow, J., Kimura, M., 1970. An Introduction to Population Genetics Theory, Blackburn Press, Caldwell. Blackburn Press, Caldwell. pp. 656. https://doi.org/10.2307/1529706.

|

Danecek, P., Auton, A., Abecasis, G., et al., 2011. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics, 27: 2156-2158. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330 |

Delmotte, F., Leterme, N., Gauthier, J.P., et al., 2002. Genetic architecture of sexual and asexual populations of the aphid Rhopalosiphum padi based on allozyme and microsatellite markers. Mol. Ecol., 11: 711-723. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01478.x |

Delph, L.F., Kelly, J.K., 2014. On the importance of balancing selection in plants. New Phytol., 201: 45-56. DOI:10.1111/nph.12441 |

Ding, C., Schreiber, S.G., Roberts, D.R., et al., 2017. Post-glacial biogeography of trembling aspen inferred from habitat models and genetic variance in quantitative traits. Sci. Rep., 7: 4672. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-04871-7 |

Dixon, G.B., De Wald, L.E., 2015. Microsatellite survey reveals possible link between triploidy and mortality of quaking aspen in Kaibab National Forest, Arizona. Can. J. For. Res., 45: 1369-1375. DOI:10.1139/cjfr-2014-0566 |

Dynesius, M., Jansson, R., 2000. Evolutionary consequences of changes in species' geographical distributions driven by Milankovitch climate oscillations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 97: 9115-9120. DOI:10.1073/pnas.97.16.9115 |

Erichsen, E.O., Wolff, K., Hansen, O.K., 2019. Genetic and clonal structures of the tree species Tilia cordata Mill. in remnants of ancient forests in Denmark. Popul. Ecol., 61: 243-255. DOI:10.1002/1438-390X.12002 |

Excoffier, L., Ray, N., 2008. Surfing during population expansions promotes genetic revolutions and structuration. Trends Ecol. Evol., 23: 347-351. DOI:10.1016/j.tree.2008.04.004 |

Falconer, D.S., Mackay, T. F.C., 1996. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics. (4th ed. ). Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK. pp. 464.

|

Frankel, O.H., Soulé, M.E., 1981. Conservation and evolution. Cambridge University Press. pp. 327.

|

Frankham, R., 1995a. Effective population size/adult population size ratios in wildlife: a review. Genet. Res., 66: 95-107. DOI:10.1017/S0016672300034455 |

Frankham, R., 1995b. Conservation genetics. Annu. Rev. Genet., 29: 305-327. DOI:10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.001513 |

Frichot, E., François, O., 2015. LEA: an R package for landscape and ecological association studies. Methods Ecol. Evol., 6: 925-929. DOI:10.1111/2041-210X.12382 |

Gain, C., François, O., 2021. LEA 3: Factor models in population genetics and ecological genomics with R. Mol. Ecol. Resour, 21: 2738-2748. DOI:10.1111/1755-0998.13366 |

Goessen, R., Isabel, N., Wehenkel, C., et al., 2022. Coping with environmental constraints: geographically divergent adaptive evolution and germination plasticity in the transcontinental Populus tremuloides. Plants People Planet, 4: 638-654. DOI:10.1002/ppp3.10297 |

Gompert, Z., Mock, K.E., 2017. Detection of individual ploidy levels with genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) analysis. Mol. Ecol. Resour., 17: 1156-1167. DOI:10.1111/1755-0998.12657 |

Goudet, J., Jombart, T., 2022. hierfstat: Estimation and Tests of Hierarchical F-Statistics. R package version 0.5-11. R Core Team. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=hierfstat.

|

Greer, B.T., Still, C., Cullinan, G.L., et al., 2018. Polyploidy influences plant–environment interactions in quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx. ). Tree Physiol., 38: 630-640. DOI:10.1093/treephys/tpx120 |

Gregorius, H. -R., 1978. The concept of genetic diversity and its formal relationship to heterozygosity and genetic distance. Math. Biosci., 41: 253-271. DOI:10.1016/0025-5564(78)90040-8 |

Haigh, J., Smith, J.M., 1974. The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genet. Res., 23: 23-35. DOI:10.1017/S0016672300014634 |

Hartfield, M., 2016. On the origin of asexual species by means of hybridization and drift. Mol. Ecol., 25: 3264-3265. DOI:10.1111/mec.13713 |

Herbert, V.F., 1992. Prácticas de relaciones agua-suelo-planta-atmósfera. Chapingo, Texcoco, Mexico: Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo, Chapingo, Texcoco, México, p. 169.

|

Hutchinson, M.F., 1991. Continent-wide data assimilation using thin plate smoothing splines. Data assimilation systems. In: Jasper, J.D. (Ed. ), Data Assimilation Systems; BMRC Research Report No. 27. Bureau of Meteorology Research Centre, Melbourne, Australia, pp. 104-113, 1991.

|

Jaccard, P., 1908. Nouvelles Recherches Sur la Distribution Florale. Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat., 44: 223-270. DOI:10.5169/seals-268384 |

Jackson, D.A., 1993. Stopping rules in Principal Components Analysis: a comparison of heuristical and statistical approaches. Ecology, 74: 2204-2214. DOI:10.2307/1939574 |

Jelinski, D.E., Cheliak, W.M., 1992. Genetic diversity and spatial subdivision of Populus tremuloides (Salicaceae) in a heterogeneous landscape. Am. J. Bot., 79: 728-736. DOI:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1992.tb13647.x |

Judson, O.P., Normark, B.B., 1996. Ancient asexual scandals. Trends Ecol. Evol., 11: 41-46. DOI:10.1016/0169-5347(96)81040-8 |

Kassambara, A., 2023. ggpubr: "ggplot2" based publication ready plots. https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/ggpubr/.

|

Kawecki, T.J., Ebert, D., 2004. Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecol. Lett., 7: 1225-1241. DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00684.x |

Kemperman, J.A., Barnes, B.V., 1976. Clone size in American aspens. Can. J. Bot., 54: 2603-2607. DOI:10.1139/b76-280 |

Klarqvist, M.D.R., 2019. Tomahawk: Fast calculation of LD in large-scale cohorts. https://github.com/mklarqvist/tomahawk.

|

Klopfstein, S., Currat, M., Excoffier, L., 2006. The fate of mutations surfing on the wave of a range expansion. Mol. Biol. Evol., 23: 482-490. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msj057 |

Kremer, A., Ronce, O., Robledo-Arnuncio, J.J., et al., 2012. Long-distance gene flow and adaptation of forest trees to rapid climate change. Ecol. Lett., 15: 378-392. DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01746.x |

Krieger, M.J.B., Keller, L., 1998. Estimation of the proportion of triploids in populations with diploid and triploid individuals. J. Hered., 89: 275-279. DOI:10.1093/jhered/89.3.275 |

Kruskal, W.H., Wallis, W.A., 1952. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 47: 583-621. DOI:10.1080/01621459.1952.10483441 |

Latutrie, M., Bergeron, Y., Tremblay, F., 2016. Fine-scale assessment of genetic diversity of trembling aspen in northwestern North America. BMC Evol. Biol., 16: 231. DOI:10.1186/s12862-016-0810-1 |

Leimu, R., Mutikainen, P., Koricheva, J., et al., 2006. How general are positive relationships between plant population size, fitness and genetic variation?. J. Ecol., 94: 942-952. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2006.01150.x |

León, A.R., Aguilar, A.S., 1987. Materia orgánica. Análisis químico para evaluar la fertilidad del suelo. SMCS. Publicación especial, 1: 217. |

Li, H., Durbin, R., 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics, 25: 1754-1760. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 |

Little Jr., E.L., 1971. Atlas of United States Trees. Conifers and Important Hardwoods. Misc. Pub. 1146, 1. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington,

DC, p. 400.

|

Luu, K., Bazin, E., Blum, M.G.B., 2017. pcadapt: an R package to perform genome scans for selection based on principal component analysis. Mol. Ecol. Resour., 17: 67-77. DOI:10.1111/1755-0998.12592 |

Mable, B.K., 2004. "Why polyploidy is rarer in animals than in plants": Myths and mechanisms. Biol. J. Linn. Soc., 82: 453-466. DOI:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2004.00332.x |

Martin, M., 2011. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J., 17: 10-12. DOI:10.14806/ej.17.1.200 |

Mitton, J.B., 1989. Physiological and demographic variation associated with allozyme variation. In: Soltis, D.E., Soltis, P.S., Dudley, T.R. (Eds. ), Isozymes in Plant Biology. Springer, Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp. 127-145. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-1840-5_7.

|

Mitton, J.B., Grant, M.C., 1996. Genetic variation and the natural history of quaking aspen. Bioscience, 46: 25-31. DOI:10.2307/1312652 |

Mock, K.E., Rowe, C.A., Hooten, M.B., et al., 2008. Clonal dynamics in western North American aspen (Populus tremuloides). Mol. Ecol., 17: 4827-4844. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03963.x |

Mock, K.E., Callahan, C.M., Islam-Faridi, M.N., et al., 2012. Widespread triploidy in western North American aspen (Populus tremuloides). PLoS One, 7: e48406. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0048406 |

Mualem, Y., 1976. A new model for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated porous media. Water Resour. Res., 12: 513-522. DOI:10.1029/WR012i003p00513 |

Neale, D.B., Kremer, A., 2011. Forest tree genomics: growing resources and applications. Nat. Rev. Genet., 12: 111-122. DOI:10.1038/nrg2931 |

Newman, D., Pilson, D., 1997. Increased probability of extinction due to decreased genetic effective population size: experimental populations of Clarkia pulchella. Evolution, 51: 354-362. DOI:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb02422.x |

Noss, R.F., 2001. Beyond kyoto: forest management in a time of rapid climate change. Conserv. Biol., 15: 578-590. DOI:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2001.015003578.x |

Ohta, T., 1982a. Linkage disequilibrium due to random genetic drift in finite subdivided populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 79: 1940-1944. DOI:10.1073/pnas.79.6.1940 |

Ohta, T., 1982b. Linkage disequilibrium with the island model. Genetics, 101: 139-155. DOI:10.1093/genetics/101.1.139 |

Olsen, S.R., Cole, C.V., Watanabe, F.S., et al., 1954. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Washington, D.C.

|

Ouborg, N.J., Pertoldi, C., Loeschcke, V., et al., 2010. Conservation genetics in transition to conservation genomics. Trends Genet., 26: 177-187. DOI:10.1016/j.tig.2010.01.001 |

Pavlidis, P., Alachiotis, N., 2017. A survey of methods and tools to detect recent and strong positive selection. J. Biol. Res. -Thessalon., 24: 7. DOI:10.1186/s40709-017-0064-0 |

Peischl, S., Kirkpatrick, M., 2012. Establishment of new mutations in changing environments. Genetics, 191: 895-906. DOI:10.1534/genetics.112.140756 |

Pellino, M., Hojsgaard, D., Schmutzer, T., et al., 2013. Asexual genome evolution in the apomictic Ranunculus auricomus complex: examining the effects of hybridization and mutation accumulation. Mol. Ecol., 22: 5908-5921. DOI:10.1111/mec.12533 |

Perala, D.A., 1990. Populus tremuloides Michx. Quaking aspen. In: Burns, R., Honkala, B. (Eds. ), Silvics of North America: Hardwoods. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington DC, USA, pp. 555-569. http://dendro.

cnre.vt.edu/DENDROLOGY/USDAFSSilvics/160.pdf.

|

Pohlert, T., 2014. The pairwise multiple comparison of mean ranks package (PMCMR). R package. |

Poland, J.A., Brown, P.J., Sorrells, M.E., et al., 2012. Development of high-density genetic maps for barley and wheat using a novel two-enzyme genotyping-by-sequencing approach. PLoS One, 7: e32253. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0032253 |

Quiñones-Pérez, C.Z., Simental-Rodríguez, S.L., Sáenz-Romero, C., et al., 2014. Spatial genetic structure in the very rare and species-rich Picea chihuahuana tree community (Mexico). Silvae Genet., 63: 149-158. DOI:10.1515/sg-2014-0020 |

R Core Team, 2022. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, v. 4.2.1. R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.rproject.org.

|

Reed, D.H., Frankham, R., 2003. Correlation between fitness and genetic diversity. Conserv. Biol., 17: 230-237. DOI:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01236.x |

Rehfeldt, G.E., 2006. A spline model of climate for the western United States. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-165. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO, pp. 21-165.

|

Ridout, M.S., 2000. Improved estimation of the proportion of triploids in populations with diploid and triploid individuals. J. Hered., 91: 57-60. DOI:10.1093/jhered/91.1.57 |

Rochette, N.C., Rivera-Colón, A.G., Catchen, J.M., 2019. Stacks 2: analytical methods for paired-end sequencing improve RADseq-based population genomics. Mol. Ecol., 28: 4737-4754. DOI:10.1111/mec.15253 |

Rogers, P.C., Pinno, B.D., Šebesta, J., et al., 2020. A global view of aspen: conservation science for widespread keystone systems. Glob. Ecol. Conserv., 21: e00828. DOI:10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00828 |

Rowe, C., 2019. vcf2Jaccard. https://github.com/carol-rowe666/vcf2Jaccard.

|

Sachs, L., 2013. Angewandte Statistik: Anwendung Statistischer Methoden. Springer-Verlag, p. 553.

|

Sáenz-Romero, C., Rehfeldt, G.E., Crookston, N.L., et al., 2010. Spline models of contemporary, 2030, 2060 and 2090 climates for Mexico and their use in understanding climate-change impacts on the vegetation. Clim. Change, 102: 595-623. DOI:10.1007/s10584-009-9753-5 |

Savolainen, O., Pyhäjärvi, T., Knürr, T., 2007. Gene flow and local adaptation in trees. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst., 38: 595-619. DOI:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095646 |

Schultz, S.T., Willis, J.H., 1995. Individual variation in inbreeding depression: the roles of inbreeding history and mutation. Genetics, 141: 1209-1223. DOI:10.1093/genetics/141.3.1209 |

Simental-Rodríguez, S.L., Quiñones-Pérez, C.Z., Moya, D., et al., 2014. The relationship between species diversity and genetic structure in the rare Picea chihuahuana tree species community, Mexico. PLoS One, 9: e111623. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0111623 |

Sjödin, A., Street, N.R., Sandberg, G., et al., 2009. The Populus genome integrative explorer (PopGenIE): a new resource for exploring the Populus genome. New Phytol., 182: 1013-1025. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02807.x |

Slatkin, M., 2008. Linkage disequilibrium - understanding the evolutionary past and mapping the medical future. Nat. Rev. Genet., 9: 477-485. DOI:10.1038/nrg2361 |

Soltis, P.S., Soltis, D.E., 2000. The role of genetic and genomic attributes in the success of polyploids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 97: 7051-7057. DOI:10.1073/pnas.97.13.7051 |

Stoeckel, S., Masson, J.P., 2014. The exact distributions of FIS under partial asexuality in small finite populations with mutation. PLoS One, 9: e85228. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0085228 |

Stoeckel, S., Grange, J., Fernández-Manjarres, J.F., et al., 2006. Heterozygote excess in a self-incompatible and partially clonal forest tree species —Prunus avium L. Mol. Ecol., 15: 2109-2118. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02926.x |

Strobl, C., Hothorn, T., Zeileis, A., 2009. Party on! A new, conditional variable importance measure for random forests available in the party package. R J., 1: 14-17. DOI:10.32614/RJ-2009-013 |

Sundell, D., Mannapperuma, C., Netotea, S., et al., 2015. The plant genome integrative explorer resource: PlantGenIE. org. New Phytol., 208: 1149-1156. DOI:10.1111/nph.13557 |

Swift, K., Ran, S., 2012. Successional responses to natural disturbance, forest management and climate change in British Columbia forests. J. Environ. Manag., 13: 1-23. DOI:10.22230/jem.2012v13n1a171 |

Thissen, D., Steinberg, L., Kuang, D., 2002. Quick and easy implementation of the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for controlling the false positive rate in multiple comparisons. J. Educ. Behav. Stat., 27: 77-83. DOI:10.3102/10769986027001077 |

Thornhill, N.W., 1993. The Natural History of Inbreeding and Outbreeding: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

|

Tossi, V.E., Martínez Tosar, L.J., Laino, L.E., et al., 2022. Impact of polyploidy on plant tolerance to abiotic and biotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci., 13: 869423. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2022.869423 |

Van de Peer, Y., Mizrachi, E., Marchal, K., 2017. The evolutionary significance of polyploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet., 18: 411-424. DOI:10.1038/nrg.2017.26 |

Van de Peer, Y., Ashman, T. -L., Soltis, P.S., et al., 2021. Polyploidy: an evolutionary and ecological force in stressful times. Plant Cell, 33: 11-26. DOI:10.1093/plcell/koaa015 |

Vázquez-Alarcón, A., Aguilar-Noh, A., 2020. Prácticas del Curso Química de Suelos. Departamento de suelos. Universidad autónoma de Chapingo, México, p. 125.

|

Venables, W.N., Ripley, B.D., 1999. Tree-based Methods. In: Venables, W.N., Ripley, B.D. (Eds. ), Tree-based Methods BT - Modern Applied Statistics with SPLUS. Springer New York, NY, pp. 303-327. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-3121-7_10.

|

Wang, J., Street, N.R., Scofield, D.G., et al., 2016. Natural selection and recombination rate variation shape nucleotide polymorphism across the genomes of three related Populus species. Genetics, 202: 1185-1200. DOI:10.1534/genetics.115.183152 |

Wang, J., Ding, J., Tan, B., et al., 2018. A major locus controls local adaptation and adaptive life history variation in a perennial plant. Genome Biol., 19: 72. DOI:10.1186/s13059-018-1444-y |

Wehenkel, C., Quiñones-Pérez, C.Z., Simental-Rodríguez, S.L., et al., 2014. Proportion of vegetation reproduction in Mexican Populus tremuloides Michx. populations on the Sierra Madre Occidental. In: 2014 IUFRO Forest Tree Breeding Conference Prague, Czech Republic, 25-29 August 2014. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.2295.5202.

|

Weiss-Schneeweiss, H., Emadzade, K., Jang, T.S., et al., 2013. Evolutionary consequences, constraints and potential of polyploidy in plants. Cytogenet. Genome Res., 140: 137-150. DOI:10.1159/000351727 |

Welch, D.M., Meselson, M., 2000. Evidence for the evolution of bdelloid rotifers without sexual reproduction or genetic exchange. Science, 288: 1211-1215. DOI:10.1126/science.288.5469.1211 |

Wickham, H., 2016. ggplot 2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org.

|

Wiehle, M., Vornam, B., Wesche, K., et al., 2016. Population structure and genetic diversity of Populus laurifolia in fragmented riparian gallery forests of the Mongolian Altai Mountains. Flora, 224: 112-122. DOI:10.1016/j.flora.2016.07.004 |

Williams, C.K., Engelhardt, A., Cooper, T., et al., 2015. Package 'caret'. Available online: https://github.com/topepo/caret/.

|

Worrall, J.J., Rehfeldt, G.E., Hamann, A., et al., 2013. Recent declines of Populus tremuloides in North America linked to climate. For. Ecol. Manage., 299: 35-51. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2012.12.033 |

Wright, S., 1940. Breeding structure of populations in relation to speciation. Am. Nat., 74: 232-248. DOI:10.1086/280891 |

Wright, S., 1969. Evolution and the Genetics of Populations: Vol. 2. The Theory of Gene Frequencies, p. 511.

|

Wright, S., 1977. Evolution and the Genetics of Populations, 3. Experimental Results and Evolutionary Deductions, p. 613.

|

Wu, Q., Zang, F., Ma, Y., et al., 2020. Analysis of genetic diversity and population structure in endangered Populus wulianensis based on 18 newly developed EST-SSR markers. Glob. Ecol. Conserv., 24: e01329. DOI:10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01329 |

Zhou, A., Zong, D., Gan, P., et al., 2020. Genetic diversity and population structure of Populus yunnanensis revealed by SSR markers. Pakistan J. Bot., 52: 2147-2155. DOI:10.30848/PJB2020-6(21) |

Zhu, Z., Kang, X., Zhang, Z., et al., 1998. Studies on selection of natural triploids of Populus tomentosa. Sci. Silvae Sin., 34: 22-31. |