b. USDA Forest Service, Sustainable Forest Management Research, 201 14th Street SW, Washington, DC 20250, USA

A central goal of evolutionary biology is to understand how organisms adapt to the environment (Montejo-Kovacevich et al., 2022). Research on the mechanisms that drive plant adaptations to the environment is especially urgent as rapid climate change threatens plant species and crops with extinction (Lovell et al., 2021; Jesse et al., 2023). One potential driver of plant ecological adaptation is hybridization (Song et al., 2020a; Zhang et al., 2022; Qu et al., 2023; Geng et al., 2024a,b). Conventional theory has suggested that hybridization between species with different adaptations is widespread and harmful. However, the introgression generated by hybridization sometimes introduces positively selected adaptive variation that can rapidly spread in the receiving species, a process known as adaptive introgression (Griffiths et al., 2021).

Adaptive introgression has been shown to enhance genetic diversity in related species and improve fitness for local environments, e.g., copepods (Griffiths et al., 2021), humans (Sankararaman et al., 2016) and butterflies (Heliconius) (Montejo-Kovacevich et al., 2022). Importantly, adaptive introgression may improve the ability of closely related species to adapt to rapid climate changes (Griffiths et al., 2021; Martha et al., 2021), with warmer temperatures promoting gene flow from equatorial or low-latitude populations more readily. Although adaptive introgression appears to be an important genetic resource, it is unclear how genetic and evolutionary forces shape the evolution of introgressed blocks. It is also unclear what the relationship is between the introgressed region and deleterious mutation load in the genome (Liu et al., 2022; Xiao et al., 2023).

Adaptive hybridization has been documented in forest woodlands (Leroy et al., 2020; Martha et al., 2021). During glacial periods, ranges of temperate forest woodland species contracted. These contractions were followed by range expansions in which separated populations come into contact and hybridize. Most studies of this type of environmental adaptability has focused on European forest woodlands, although a small number of taxa in East Asia have also been examined, e.g., Euptelea (Cao et al., 2020), Pterocarya macroptera (Wang et al., 2023a), Davidia involucrata (Ren et al., 2024), Liquidambar (Wang et al., 2025). However, there is a lack of systematic studies on the interactions between genetic diversity, environmental adaptive genetic variation, and gene introgression of species with important ecological value and endangered species (Yang et al., 2013; Pu et al., 2014).

Pterocarya, a genus of Juglandaceae that includes eight extant species, is a useful model for studying environmental adaptation and adaptive introgression (Qian et al., 2019; Geng et al., 2024a,b; Zhang et al., 2024). The genus became widely distributed in temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere following the Oligocene. Due to global cooling, most taxa became extinct at high latitudes. Today, the extant species are only found in East Asia (seven species) and the southern Caucasus (one species) as a component of the Tertiary relict woodland (Song et al., 2020a; Yan et al., 2024). Pterocarya is monoecious, but male flowers (catkins) and female flowers (borne in terminal panicles) of the same individual mature at different times. In Pterocarya species, pollen is wind dispersed, landscape-level gene flow between populations is frequent, and opportunities for interspecific hybridization are frequent.

Previous studies showed that Pterocarya can be divided into two sections based on the presence or absence of bud scales; members of the section with bud scales grow at higher elevations than those without bud scales because bud scales wrap tender buds and retain heat (Song et al., 2020b; Zhang et al., 2020b). Pterocarya macroptera, with bud scales, is mainly distributed in the high mountain valleys of the Qinling-Daba Mountains (elevation: 1120–1830 m) (Wang et al., 2023a). Pterocarya stenoptera, without bud scales, is primarily found in the low-elevation areas along the coast and inland of China (elevation: 320–850 m) (Li et al., 2022). Pterocarya hupehensis, also without bud scales, is mainly distributed in the mountain valleys around the Sichuan Basin (elevation: 750–1310 m) (Lu et al., 2024). The elevational range of Pterocarya hupehensis is intermediate between those of P. macroptera and P. stenoptera. The three species are sympatrically distributed in the Qinling-Daba Mountain area across different elevations, providing excellent material for studying the genomic footprints of environmental adaptation.

In this study, we asked how three species of Pterocarya, which are sympatric but occupy different elevational niches, adapted to the heterogeneous environment of the Qinling-Daba Mountains, China. To answer this question, we analyzed population genetic structure, demographic history, adaptive genetic variation, and gene introgression in the three species. Our findings highlight the important role of gene introgression in environmental adaptation, and clarify signatures of introgression blocks in plant genomes.

2. Methods and materials 2.1. Whole genome re-sequencing and mappingFollowing Flora of China, we treated Pterocarya delavayi, P. insignis, and P. macroptera as distinct species. Whole genomes of 102 individuals from six species were re-sequenced, including three individuals of P. delavayi, one individual of P. insignis, three individuals of P. tonkinensis, twenty-eight individuals of P. macroptera, thirty-two individuals of P. hupehensis, thirty-five individuals of P. stenoptera. Information on samples is detailed in Tables S1 and S2. Genomic DNA was extracted from dried leaves using a Genomic DNA extraction kit (TIANGEN, BEIJING, China). The sequencing library was generated using NEBNext® UltraTM DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, USA). The qualified libraries were pooled and sequenced on Illumina platforms using the PE150 strategy in Novogene Bioinformatics Technology (Beijing, China).

Original fluorescence image files obtained from the Illumina platform were transformed to short reads (Raw data) by base calling and these short reads were recorded in fastq format. Fastp v.0.19.7 (Chen et al., 2018) was used to perform basic statistics on the quality of the raw reads. High-quality clean reads were obtained after adapter trimming, removal of any read containing more than 15 uncertain bases, and removal of any read with over 50% of bases having low quality (Phred quality < 5).

2.2. Phylogenetic relationships and population genetic structure of PterocaryaCoalescent-based method was used to create a phylogenetic tree based on single-copy nuclear genes. A total of 5449 single-copy nuclear genes were obtained from three genomes Juglans mandshurica (Yan et al., 2021), Cyclocarya paliurus (Zhang et al., 2022) and Pterocarya stenoptera (Geng et al., 2024a,b). We used orthofinder v.2.5.4 (Emms and Kelly, 2015) to obtain a suitable set of query sequences. The clean reads of 24 individuals (Table S1, including 3 Pterocarya delavayi, 1 P. insignis, 3 P. tonkinensis, 5 P. macroptera, 5 P. hupehensis, 5 P. stenoptera, 1 Cyslocarya paliurus, and 1 Juglans mandshurica) were aligned to query sequences by bwa v.0.7.17 and assembled to contigs by spades v.3.15.4 (Bankevich et al., 2012) with a coverage cutoff value of 5. Each gene sequence was retrieved using hybpiper v.2.1.6 (Johnson et al., 2016), aligned using mafft v.7.520 with the '-auto' option, and trimmed using trimal v.1.4.rev15 (Capella-Gutiérrez et al., 2009) with the command '-gt 0.2'. The best ML gene tree was estimated from the unpartitioned alignment for each gene in iqtree v.1.6.6 (Nguyen et al., 2015) using the best-fit models selected by modelfinder program. Newick utilities v.1.6 (Junier and Zdobnov, 2010) was used to splice out the nodes with bootstrap values of less than 10. After summarizing a set of gene trees, the species tree was estimated by astral-Ⅲ v.5.7.8 (Zhang et al., 2018). Trees were refined by the online tool itol v.5 (Letunic and Bork, 2021). Cyslocarya paliurus and Juglans mandshurica were used as outgroups.

Population genetic structure was inferred with ADMIXTURE based on SNP data from 16 chromosomes of the nuclear genome. High-quality clean reads were mapped to the Pterocarya stenoptera reference (Geng et al., 2024a,b, NCBI accession number: PRJNA992759) genome using bwa-mem v.0.7.15 with default options (Li and Durbin, 2009). After sorting with samtools v.1.9 (Li et al., 2009), duplicates were marked in sambamba v.1.0.0 (Tarasov et al., 2015) with the 'markdup' command. We utilized GATK v.4.0.5.1 (DePristo et al., 2011) HaplotypeCaller to detect per-sample variants and merged all individuals with the CombineGVCFs tool, resulting in a combined g.vcf file for 24 individuals. Joint genotyping was performed with the GenotypeGVCFs tool. To further retain high quality SNPs and minimize genotype calling bias, 1) SNPs with multi-alleles (> 2) were removed; 2) SNPs with quality by depth (QD) < 2.0, FS > 60, MQ < 40, SOR > 3.0, MQRankSum < −12.5 and ReadPosRankSum < −8.0 were filtered; 3) SNPs located within 5-bp distance from any indels were filtered; 4) read depth (DP) < 5 and genotype quality (GQ) < 10 mask as missing, SNPs with missing rate higher than 20% were filtered. We then used vcftools (Danecek et al., 2011) to convert the vcf file to the desired format, and plink v.1.9 (Purcell et al., 2007) with the command "--indep-pairwise 50 10 0.2" to filter the linked SNP sites. After filtering, 4,454,641 SNPs remained. The postulated number of ancestral populations, K, was set from 2 to 6, and performed 10-fold cross-validation (-cv = 10).

2.3. Phylogeny and population genetic structure analysis of Pterocarya stenoptera , P. hupehensis, and P. macropteraTo verify the phylogenetic relationship and population genetic structure of the three species distributed in the Qinling-Daba Mountains, we sampled 95 individuals (Table S2) from Pterocarya stenoptera, P. hupehensis, and P. macroptera. Joint genotyping was carried out with the GenotypeGVCFs tool. To ensure the accuracy of subsequent analyses, we generated "all sites" vcf files (including non-variant sites) and "variant sites" vcf files by using or not using the "all_sites" flag during SNP calling and genotyping. High quality SNPs and genotype calling bias were obtained as above, and resulted in a total of 42,708,265 SNPs from 16 chromosomes of the nuclear genome.

Nucleotide diversity (π) was calculated based on the "all sites" vcf files in 10 kb nonoverlapping windows using VCFtools v.0.1.17 (Danecek et al., 2011). Relative divergence (Fst) was calculated for the 42,708,265 SNPs in 10 kb nonoverlapping windows using VCFtools v.0.1.17 (Danecek et al., 2011). Absolute nucleotide divergence between species (Dxy) were calculated for the consensus sequences (including non-variant sites) using python scripts (https://github.com/yongshuai-sun/hhs-omei/) based on 42,708,265 SNPs in 10 kb nonoverlapping windows.

Phylogenetic relationship and population genetic structure were analyzed for 10,742,868 SNPs with minor allele frequency (maf) < 0.05 filtered. We converted the vcf file into a fasta file using a perl script (Geng et al., 2022) and constructed the maximum likelihood tree using iqtree v.1.6.6 (Nguyen et al., 2015). The GTR + F + R7 model was selected based on modelfinder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017), with 1000 bootstrap replicates (Hoang et al., 2018). Different portions of the complete chloroplast genome data sets were used for maximum likelihood (ML) trees analysis: 1) the complete chloroplast genome sequences, 2) protein-coding genes extracted from the complete chloroplast genome sequences. Clean reads were selected for de novo assembly using getorganelle v.1.7.5.3 (Jin et al., 2020), where the range of k-mer was set to 21, 45, 65, 85, 105 and max-rounds to 15. The assembly results were checked for loops and followed by manual correction. Then, complete circular chloroplast genome sequences were annotated using the cpgavas2 (Shi et al., 2019) online tool with the default settings using Pterocarya stenoptera (NC_046428) as a reference. Protein coding genes were extracted from the complete chloroplast genome sequences using phylosuite v.1.2.2 (Zhang et al., 2020a). Two portions of the complete chloroplast genome data set were aligned by mafft program (Katoh and Standley, 2013) with default parameters. The best-fit model was obtained according to Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) score calculated with modelfinder program (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017). ML analysis was performed using the SH-like approximate likelihood ratio test (SH-aLRT) (Guindon et al., 2010) with 1000 replicates and iqtree v.1.6.6 (Nguyen et al., 2015) for 5000 ultrafast (Minh et al., 2013) bootstraps. The best-fit model of the complete chloroplast genome sequences was TVM + F + I, whereas that of protein coding genes was TVM + F + R2. Cyclocarya paliurus (NC_034315.1) and Juglans mandshurica (NC_033892) were used as outgroups. Annotations were manually adjusted according to the reference genome to assign the start and stop codon boundaries and the boundaries of exons and introns.

We inferred the population genetic structure using ADMIXTURE v.1.4.0 (Alexander et al., 2009). Linked SNP sites were filtered by plink v.1.9 (Purcell et al., 2007) with command "-indep-pairwise 50 10 0.2". The postulated number of ancestral populations, K, was set from 2 to 7, and performed with 10-fold cross-validation (-cv = 10) based on 713,627 SNPs. PCA was performed on 10,742,868 SNPs using the smartpca program from the eigensoft v.6.1.4 software package (Patterson et al., 2006) with default parameters.

2.4. Demographic history analysis and ecological niche modeling (ENM)Demographic history and effective population size were calculated using psmc v.0.6.4 (Li and Durbin, 2011) and smc++ v.1.15.2 (Terhorst et al., 2017). A mutation rate of 2.06E-9 per site per year and a generation time of 30 years (Geng et al., 2024a,b) were used to scale the population parameters.

MaxEnt was used to predict the potential distributions of Pterocarya stenoptera, P. hupehensis and P. macroptera across four time periods (Phillips and Dudík, 2008): Current, Mid-Holocene (MH), Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and Last Interglacial (LIG) periods. Global climate and weather data for these periods were downloaded from the World Bioclim (Worldclim, https://worldclim.org/) (Fick and Hijmans, 2017) online website. Latitude and longitude information on the distribution points of P. stenoptera, P. hupehensis and P. macroptera were downloaded from three major databases, Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae (http://www.cn-flora.ac.cn/), Chinese Virtual Herbarium (https://www.cvh.ac.cn/) and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, https://www.gbif.org/). Information on the distribution of all samples was de-redundantly processed. Climate data were extracted from collected specimen distribution point information using arcgis v.10.6.1 (ESRI). Because correlation between 19 climate factors can lead to inaccurate results, Pearson correlation coefficients between climate factors were calculated using the R package usdm (Dormann et al., 2013). Climate factors with strong correlations (Spearman correlation > 0.8) were excluded. Our ecological niche modeling was run times with the remaining climate factors: P. stenoptera, BIO2, BIO3, BIO7, BIO8, BIO9, BIO10, BIO14, BIO15 and BIO18; P. hupehensis, BIO2, BIO3, BIO4, BIO8, BIO13, BIO15 and BIO17; P. macroptera, BIO2, BIO4, BIO8, BIO9, BIO13, BIO14 and BIO15.

2.5. Selective sweep analysisPopulation selective sweep was analyzed by xp-clr (Chen et al., 2010) and xp-ehh (Browning and Browning, 2009), using both non-overlapping 10 Kb windows. The LD value for xp-clr analysis was 0.95, and the minimum number of SNPs in each window was set to 200. Outlier windows (top 5%) detected by both methods were considered as candidate regions. Genetic differentiation (Fst and Dxy) and genetic diversity in candidate selected regions were calculated with non-overlap 10 kb window size using the python script of Martin et al. (2015). We used bedtools (Quinlan and Hall, 2010) to extract genes of candidate regions. Functional annotation was performed using the eggNOG-mapper (http://eggnog-mapper.embl).

2.6. Identification of environment-associated genetic variantsThe contribution of the full range of environmental variables was assessed by entering the allele frequency file in the R package "gradientForest" (GF) (Ellis et al., 2012). The maxLevel parameter was calculated from allele frequencies and environmental variables, with ntree set to 500, and the correlation threshold set to 0.5. The correlation between the 19 climate factors on the redundancy analysis (RDA) axis was calculated. If the correlation between two climate factors was greater than 0.8, one of them was excluded. The combination of the two methods resulted in the retention of 7 environmental factors for subsequent analysis (BIO2, BIO4, BIO6, BIO8, BIO15, BIO7 and elevation). We performed redundancy analysis to detect the environment-associated genetic variants based on a data set of 10,742,868 SNPs (Capblancq and Forester, 2021) in the R package vegan. Candidate SNPs were based on the value of the standard deviation on the RDA axis with a cutoff of 3 (two-tailed p-value = 0.0027). We used bedtools (Quinlan and Hall, 2010) to further reveal the functions of candidate SNPs. Functional annotation was performed using the eggNOG-mapper (http://eggnog-mapper.embl), and GO enrichment analysis was conducted using the R package clusterProfilerr (Wu et al., 2021).

2.7. Inbreeding and genetic burden analysisPlink v.1.9 (Purcell et al., 2007) was used to calculate individual, genome-based coefficients of homozygosity or 'autozygosity' (in terms of FROH, based on g.vcf file) and heterozygosity (He). We calculated the deleterious genetic load carried by each species. First, we used snpeff v.5.00 (Cingolani et al., 2012) to classify SNP variants into three types: loss-of-function (LOF), missense, and synonymous variants. Deleterious variants were extracted based on the score calculated by the sift4g software (score ≤ 0.05) (Vaser et al., 2016). We used est-sfs v.2.03 (Keightley and Jackson, 2018) to infer the probability of the derived versus ancestral allelic state, with a probability cutoff set at 0.95 (Keightley and Jackson, 2018; Feng et al., 2024). P. stenoptera and P. hupehensis served as outgroups for P. macroptera, P. stenoptera and P. macroptera served as outgroups for P. hupehensis, while P. hupehensis and P. macroptera were utilized as outgroups for P. stenoptera. The numbers of homozygous and heterozygous alleles for the three variants in each individual were then calculated using plink v.1.9 (Purcell et al., 2007), where the relative proportions of deleterious, loss of function, and synonymous mutations were estimated for each individual.

2.8. Gene introgression test between speciesTo detect gene flow in the internal populations of Pterocarya, we used vcf files of 33,038,707 SNPs (Section 2.2) generated by 24 individuals (Table S1). To detect gene flow between the three species, the vcf files of 10,742,868 SNPs (Section 2.3) generated by 95 individuals (Table S2) from P. stenoptera, P. hupehensis, and P. macroptera were used. Treemix v.1.13 (Pickrell and Pritchard, 2012) was used to infer the direction and intensity of gene flow. The number of migration edges (m parameters) of the treemix algorithm was set between 1 and 5, and each m parameter was iterated five times. The default "Evanno" quadrat and the linear model in R package optm (Fitak, 2021) were used to determine the optimal m-value. To further confirm genetic introgression, ABBA-BABA analysis (Patterson's D) was performed using dsuite v.0.3 (Malinsky et al., 2021). Patterson's D (Durand et al., 2011) measures the excess of shared derived alleles between P3 and either P1 or P2 based on a tree model of four species as (((P1, P2), P3, O), where (P1, P2), P3 is Pterocarya species and O is the outgroup. We calculated D for all combinations of trios that are compatible with the species topology using Cyslocarya paliurus and Juglans mandshurica as outgroups. The Patterson's D is 0 when there is no gene introgression between P1, P2, and P3, and will be positive or negative if there is gene introgression between P2 and P3 or between P1 and P3.

To locate introgressed genomic regions for three Pterocarya species based on significant Patterson's D, we implemented two statistical analyses. First, we used twisst (Geng et al., 2022) to calculate the weightings of all possible tree topologies through 100,000 iterative samplings of subtrees along the genomes. In the second approach, we first calculated the f4 admixture ratio statistics in dsuite (Geng et al., 2022). By computing the fd and its extension fdM statistics for sliding windows of 10 kbp, we defined the putative introgressed regions as windows with highest X% of fdM values (Morales-Cruz et al., 2021), where X was determined by the f4 admixture ratio statistics. To determine adaptive introgression regions, we intersected the candidate gene introgression region and the outlier windows (top 5%) detected by xp-ehh. The overlap region was defined as the adaptive introgression region. To further analyze adaptive introgression genes, we used bedtools to extract gene IDs, and then performed functional annotation on these genes with R package clusterprofiler (Wu et al., 2021) to determine the biological function.

2.9. Comparative analysis of gene introgression regionsTo compare genomic signatures between adaptive introgressive regions and whole genomes, we used "bedtools shuffle" (Quinlan and Hall, 2010) to randomly generate 1000 genomic regions. Each of the genomic regions was the same size so that these genomic regions were representative of the genome-wide range. We compared the Fst, Dxy, π, recombination rate and deleterious mutation load between the introgression regions and 1000 randomly selected genomic regions. We used the fasteprr v.2.0 (Gao et al., 2016) to calculate the recombination rate using three functions "step 1, step 2, step 3" with a window of 100 kb based on 10,742,868 SNPs. To further compare the characteristics of adaptive and non-adaptive introgressive areas, we used R packages ggsignif and ggplot2 (Cao et al., 2023) to make box plots that compare Fst, Dxy, π and recombination rates of P. hupehensis and P. macroptera.

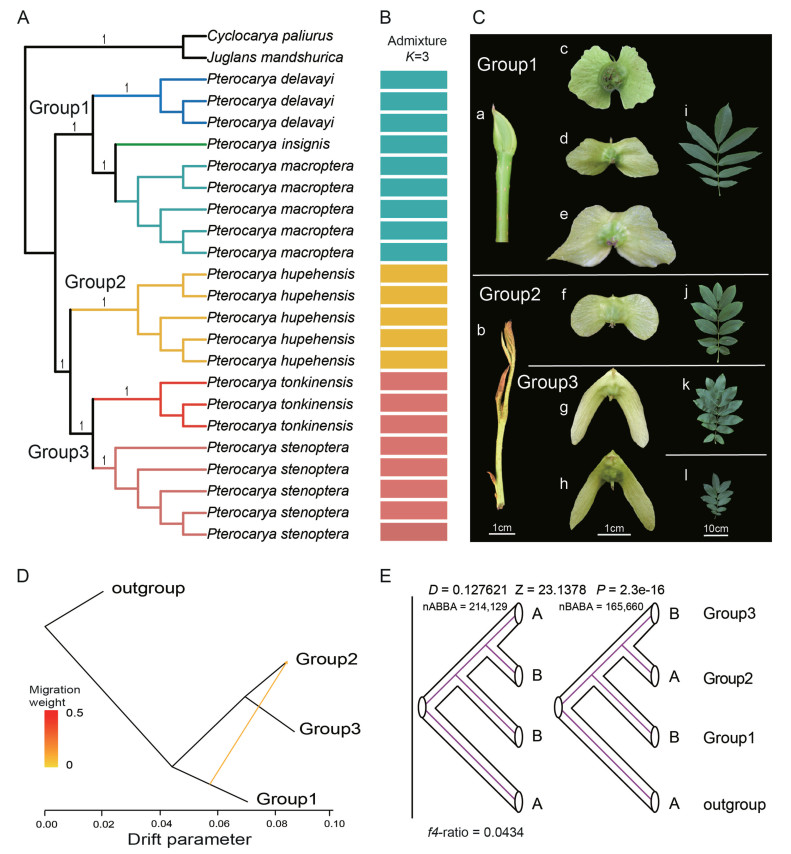

3. Results 3.1. Phylogeny of the genus Pterocarya in ChinaCoalescent-based phylogenetic analysis based on single-copy nuclear gene showed that the six Chinese species of Pterocarya are each monophyletic (Fig. 1A; sample information is detailed in Table S1). P. insignis was sister to P. macroptera and formed a fully supported (LPPs = 100) monophyletic branch with P. delavayi, while P. tonkinensis was sister to the P. stenoptera and formed a fully supported (LPPs = 100) monophyletic branch with P. hupehensis (Sample information is detailed in Table S2). The population genetic structure of the six species was analyzed using the admixture, the optimal K value with the lowest CV error was 3 (Figs. S1 and S2). When K = 3, P. insignis, P. macroptera and P. delavayi were joined as a single genetic unit, Pterocarya tonkinensis and P. stenoptera were joined, and P. hupehensis was genetically distinct. We accordingly defined P. insignis, P. macroptera and P. delavayi as group1, P. hupehensis as group2, and P. tonkinensis and P. stenoptera as group3 (Fig. 1B). Group1 is distributed at higher altitudes (1120–2300 m) than the members of the other groups and has bud scales.

|

| Fig. 1 Phylogenetic relationships and gene introgression of the genus Pterocarya in China. (A). Single-copy nuclear gene data were used to construct the phylogenetic tree of Pterocarya distributed in China, with Cyclocarya paliurus and Juglans mandshurica as outgroups. Numbers on nodes represent local posterior probabilities (LPPs). (B) Population genetic structure of six species. Optimal K value was 3. Different colors indicate different groups. (C) Photos of bud, fruit, and leaves of six species. a. Buds of Group1 are enclosed by scales; b. Buds of Group1 and Group2 are not enclosed by scales. c–h. Fruit of P. delavayi, P. insignis, P. macroptera, P. hupehensis, P. tonkinensis and P. stenoptera. i. Leaves of Group1; j. Leaves of Group2; k. Leaves of P. tonkinensis; l. Leaves of P. stenoptera. (D) Treemix Analysis. Arrow indicates the direction of gene flow. (E) ABBA-BABA analysis of the three groups. D-statistic was used to assess the imbalance of the pattern of ABBA and BABA loci, and the non-zero D-statistic implies gene flow. Z-value is used to measure the significance of statistics. P value indicates the level of significance that deviates from zero. f4-ratio indicates the proportion of gene introgression. |

Pterocarya insignis, P. macroptera, and P. delavayi are distributed at high elevations (1120–2300 m). These plants have bud scales and can be distinguished from one other by the shape of the embryo wings (Fig. 1C). P. hupehensis is distributed between 600 and 1300 m. P. hupehensis has bare buds and its reproductive organs are similar to those of plants in the P. insignis-P. macroptera-P. delavayi group. P. tonkinensis and P. stenoptera plants grow at low elevations (300–880 m). These plants also have bare buds and can be distinguished from one another the most obvious by the presence/absence of wings on their leaves. Our analysis indicates that gene introgression (introgression ratio = 4.34%) occurred from the P. insignis-P. macroptera-P. delavayi group into P. hupehensis (Fig. 1D and E).

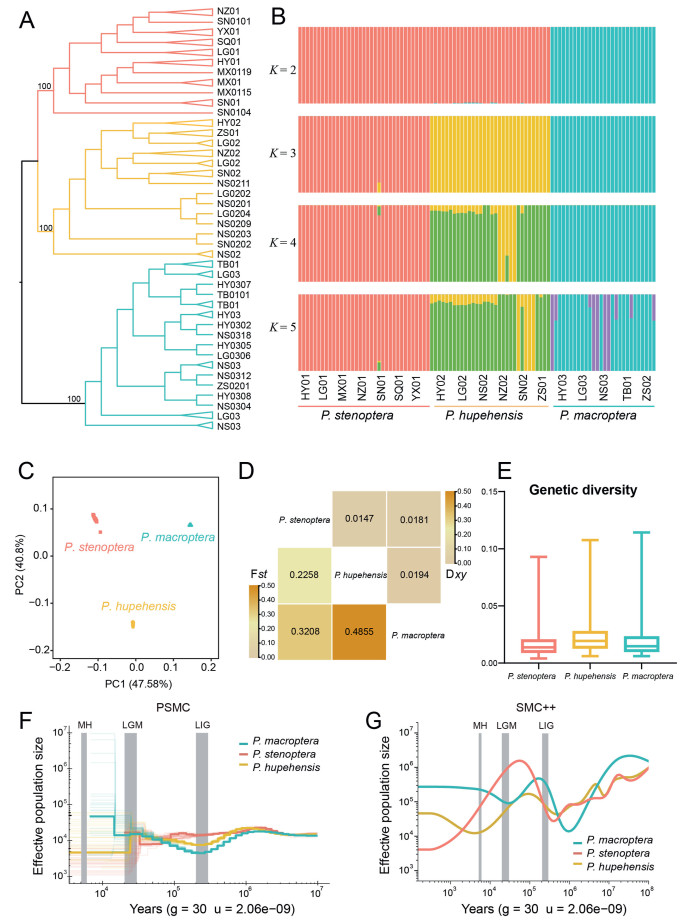

3.2. Population genetic structure and demographic history of the three speciesTo determine the role genome evolution in environmental adaptation, we analyzed the phylogenetic relationships, population genetic structure, genetic differentiation and diversity of three species of Pterocarya that are endemic to China (Song et al., 2020b) and distributed in the Qinling-Daba Mountains at different elevations: P. stenoptera (35 individuals), P. hupehensis (32 individuals) and P. macroptera (28 individuals) (Table S2 and Fig. S3). Phylogenetic analysis based on nuclear genome data showed that each of the three species formed a monophyletic branch with full bootstrap support (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly, phylogenetic analysis based on chloroplast genome data showed that none of the three species form a monophyletic lineage, indicating a history of hybridization and genetic introgression among the three species (Figs. S4 and S5).

|

| Fig. 2 Phylogeny, population genetic structure and demographic history analysis. (A) Phylogenetic relationships of Pterocarya stenoptera, P. hupehensis and P. macroptera based on SNPs. P. stenoptera represented by pink lines, P. hupehensis represented by yellow lines, and P. macroptera represented by blue lines. (B) Population genetic structure of three species based on ADMIXTURE analysis. (C) PCA analysis of three species. (D) Heatmap of population divergence (Fst and Dxy) among three Pterocarya species. (E) Box plot of genetic diversity for each of the three Pterocarya species. (F) PSMC estimates of the effective population size (Ne) changes for three Pterocarya species. Mutation rate (μ) = 2.06e-9 and generation time (g) = 30 years. (G) SMC++ estimates of the effective population size (Ne) changes for three species. Mutation rate (μ) = 2.06e-9 and generation time (g) = 30 years. |

The population genetic structure of the three species was analyzed using ADMIXTURE; the lowest CV error was obtained when K = 3 (Fig. S6). When K = 2, Pterocarya stenoptera and P. hupehensis shared ancestral genetic components. At K = 3 (CV = 0.32846), each of the three species showed a distinct genetic composition. At K = 4, P. hupehensis contained two sub-populations, while the remaining two species remained unique and singular (Fig. 2B). A high proportion of the SNP variance could be explained using only two principal components (PC1, variance explained = 47.58%; PC2, variance explained = 40.8%), clearly separating the three species (Fig. 2C). Genetic differentiation was greatest between P. hupehensis and P. macroptera (Fst = 0.4855, Dxy = 0.0194); there was less genetic differentiation between P. stenoptera and P. hupehensis (Fst = 0.2258, Dxy = 0.0181) (Fig. 2D). Genetic diversity was highest in P. hupehensis (π = 0.0265), and lowest in P. stenoptera (π = 0.0169) (Fig. 2E).

Pairwise sequentially Markovian coalescent (PSMC) and SMC++ analyses revealed that the demographic histories of the three endemic Pterocarya species were similar until ~1 million years ago (Mya), when effective population sizes for all three species began to fluctuate (Fig. 2F and G). SMC++ analysis indicated that the effective population size of P. macroptera expanded first at ~1 Mya, followed by that of P. hupehensis and P. stenoptera. From approximately 0.2 Mya to 0.001 Mya, P. macroptera and P. hupehensis experienced a second significant population contraction and expansion, while P. stenoptera continued to contract (Fig. 2F and G). The two contraction and expansion events of P. macroptera and P. hupehensis populations corresponded to glacial and interglacial periods; notably, P. stenoptera populations only experienced one contraction and expansion event.

Our analysis predicted habitat for Pterocarya stenoptera, P. hupehensis, and P. macroptera across four distinct periods (Current, Mid-Holocene, Last Glacial Maximum and Last Interglacial). The best predictors of habitat were determined by MaxEnt (Table S3). The CCSM4 model indicated that the area of the potential distribution of P. stenoptera expanded from the Last Interglacial to the Mid-Holocene period, with a slight contraction resulting in the present pattern (Table S4 and Fig. S7). The potential distribution area of P. hupehensis and P. macroptera decreased from the Last Interglacial to Mid-Holocene periods, with slight expansions resulting in the present pattern.

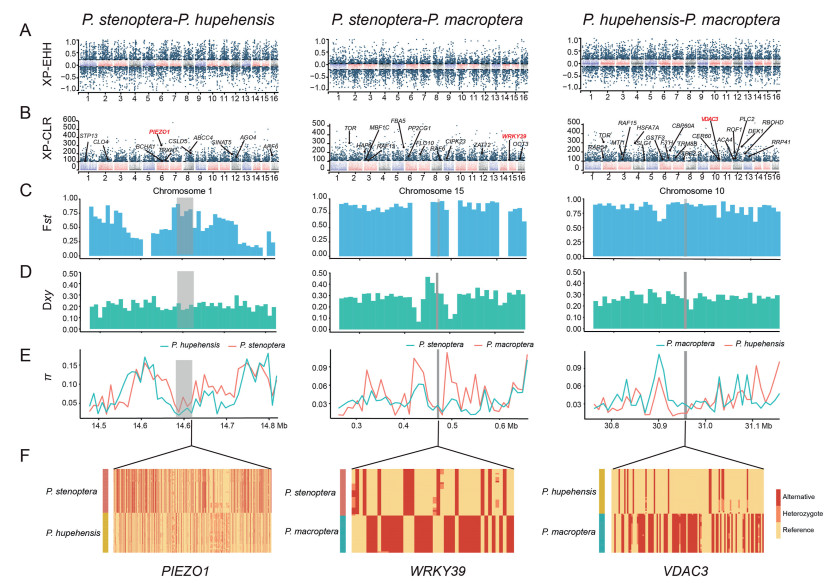

3.3. Genes under positive selection for environmental adaptationTo further elucidate the underlying genetic mechanisms by which each of the three species is adapted to their environments, we identified genes under positive selection by using cross-population extended haplotype homozygosity (XP-EHH) and cross-population composite likelihood ratio (XP-CLR) (Fig. 3). We identified 335 genes that may be under positive selection in P. stenoptera, 272 in P. hupehensis, and 111 in P. macroptera. Functional annotation indicated that 10 these genes are related to differences in environmental adaptation between P. stenoptera and P. hupehensis. Specifically, the functions of these genes include response to water deprivation (ABCC4, CSLD5, SINAT5, CLO4, STP13), response to light stimulus (ARF6), cellular response to radiation (ARF6), cellular response to oxidative stress (TRXH1), response to environmental stimulus (ARF6, PIEZO1, BCHA1), and response to virus (AGO4) (Fig. 3B and Table S5). In addition, 12 environment-related genes were identified that differ between P. stenoptera and P. macroptera. These genes function in response to cold (FLO10, WRKY39, OCT3, HAP6), response to water deprivation (PP2CG1, CIPK23, MBF1C, OCT3), response to heat (MBF1C, Z12), response to UV-B (ZAT12), response to oxygen levels (RAF6, ATFBA5), response to environmental stimulus (OCT3), and response to viruses (TOR) (Fig. 3B and Table S5). Another 20 genes differed between P. hupehensis and P. macroptera. These positively selected genes function in response to cold (TRM8B, PLC2, ACA4, VDAC1, GSTF3, CER60), response to water deprivation (PLC2, ACA4, SLG1), response to heat (RBOHD, ROF1, HSFA7A), response to UV-B (F3′H, CBP60A), response to oxygen levels (RAF15, CBP60A, HSFA7A), response to high light intensity (HSFA7A, SBE2.2), cellular response to oxidative stress (MTI1), response to environmental stimulus (DEK1, ATRAD54), and response to viruses (TOR, RRP41) (Fig. 3B and Table S5).

|

| Fig. 3 Positively selected genes related to the environment from three Pterocarya species. (A) Manhattan plot of the proportion of SNPs with |XP-EHH| > 2 distribution among two species. (B) Distribution of candidate genes in XP-CLR Manhattan plot, with black dashed lines representing the top 5% of XP-CLR scores. (C and D) Blue and green bars represent the distribution of Fst and Dxy at 2 kb upstream and downstream of genes differentiating two species, respectively. Grey shade represents candidate genes. (E) Line chart showing nucleotide diversity distribution of candidate genes 2 kb upstream and downstream. (F) Haplotype heatmap of candidate genes in two-species comparisons. Yellow represents homozygous genotype of alternative alleles, orange represents heterozygous, and red represents homozygous genotypes of reference alleles. Each row represents an individual and each column represents a SNP locus. PIEZO1 gene contains 833 SNPs, WRKY39 contains 44 SNPs, and VDAC3 contains 108 SNPs. |

To infer the effect of environmental adaptation on species differentiation, we identified genes apparently under environmental selection in each species that also appeared in regions of high differentiation (top 5% Fst windows). Regions of high differentiation between Pterocarya stenoptera and P. hupehensis contained PIEZO1 (response to environmental stimulus) genes. Regions of high differentiation between P. stenoptera and P. macroptera contained several genes that appear to be under environmental selection, including WRKY39 (response to cold), TOR (defense response to virus), FLO10 (respond to cold), and RAF6 (response to decreased oxygen levels). Regions of high differentiation between P. hupehensis versus P. macroptera contained potential environmentally selected genes as well, including TOR (defense response to virus), VDAC1 (respond to cold), RAF15 (respond to oxygen levels), ROF1 (thermotolerance) and DEK1 (response to environmental stimulus).

When we overlapped positively selected genes with candidate present in highly differentiated regions, we identified seven positively selected genes (i.e., PIEZO1, WRKY39, VDAC3, RAF6, WRKY41, RAF15 and ROF1) that may also be under environmental selection (Figs. 3C–E, S8 and S9). This finding suggests these genes play an important role in the environmental adaptation and divergence of the three species.

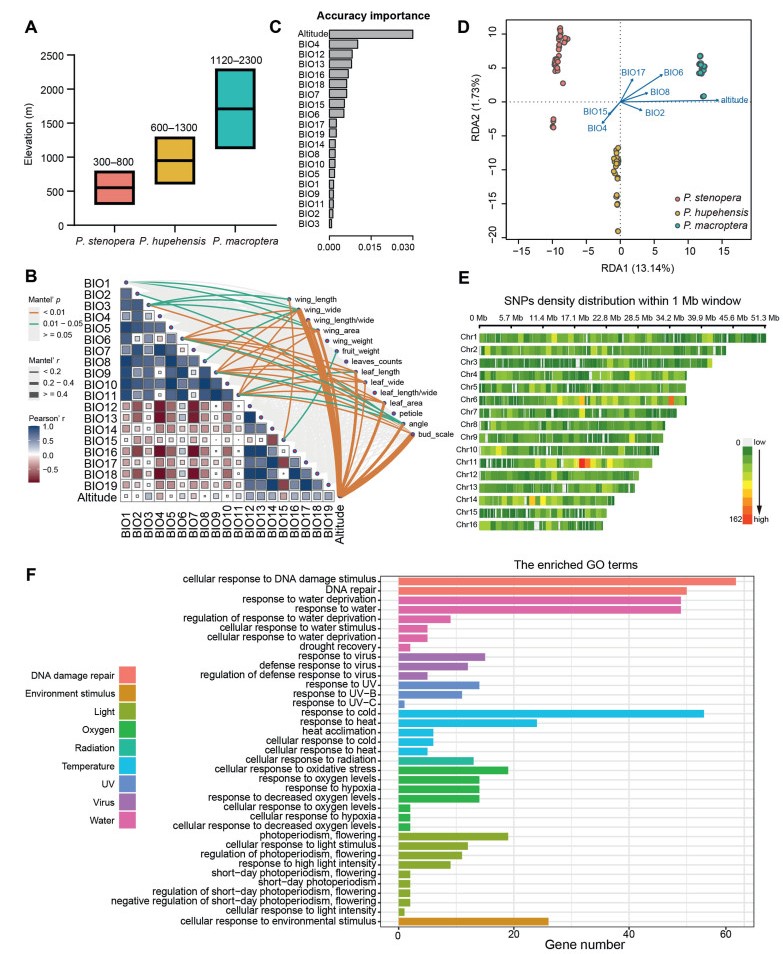

3.4. Environmental associations with phenotype and genetic variationWe identified 12 phenotypes that differ significantly among species (Fig. S10). In addition, phenotypic data was placed into three clusters corresponding to species (Figs. S11 and S12), indicating a high degree of variation in phenotypic traits among the species. Climatic factors and elevation also differed significantly for the three species, indicating that the three species occupy different ecological niches (Fig. S13). To infer associations between phenotypes and adaptation to the environment, we looked for correlations between environmental factors and phenotypic traits. We found that eight phenotypes (wing width, wing length/width, wing area, leaf length, leaf wide, leaf area, leaf angle, bud scale +/−) were significantly correlated with nine environmental factors. Elevation was strongly correlated with all eight phenotypes (Fig. 4A and B), indicating that elevation may be the overriding factor that drives adaptation in these three species.

|

| Fig. 4 Environmental associations with phenotype and genetic variation. (A) Elevational distribution of three Pterocarya species. (B) Correlation between phenotype and environmental variables. (C) Environmental variables used in the gradient forest modeling. Variables were ordered by ranked importance. (D) RDA biplot for P. stenoptera, P. huphensis and P. macroptera showing RDA axes 1 and 2. (E) Heatmap of SNPs density distribution within 1 Mb window size. (F) Functional annotation analysis of candidate genes. |

Gradient forest analysis showed that the environmental factor that contributed most to the genetic variation of the three species was elevation (Fig. 4C). RDA analysis of environmental traits (elevation, BIO2, BIO4, BIO6, BIO8, BIO15 and BIO17) showed that seven environmental variables can explain 23% of the genetic variation, with 13.14% for RDA1 axis and 1.73% for the RDA2 axis (Fig. 4D). The factors that contributed most were elevation and BIO6 (Minimum temperature of the coldest month).

To determine the relationship between candidate SNPs and environmental variables, we used RDA analysis of re-sequenced data from 95 individuals (Fig. S14A–C). A total of 18,056 candidate SNPs distributed on all sixteen chromosomes were significantly associated with seven ecological factors (Fig. 4E). The number of genes associated with each climatic factor varied (Fig. S14D), with a total of 2987 candidate genes after de-duplication. GO analysis indicated that 199 genes located in the candidate regions were enriched for environmental adaptations, i.e., response to cold, response to heat, heat acclimation, response to water deprivation, response to UV, heat shock protein binding, cellular response to environmental stimulus, cellular response to light stimulus, regulation of photoperiodism and flowering, and response to hypoxia (Table S6 and Fig. 4F). Furthermore, 64 genes were significantly enriched in cellular response to DNA damage stimulus and DNA repair (Table S7; Figs. 4F and S15).

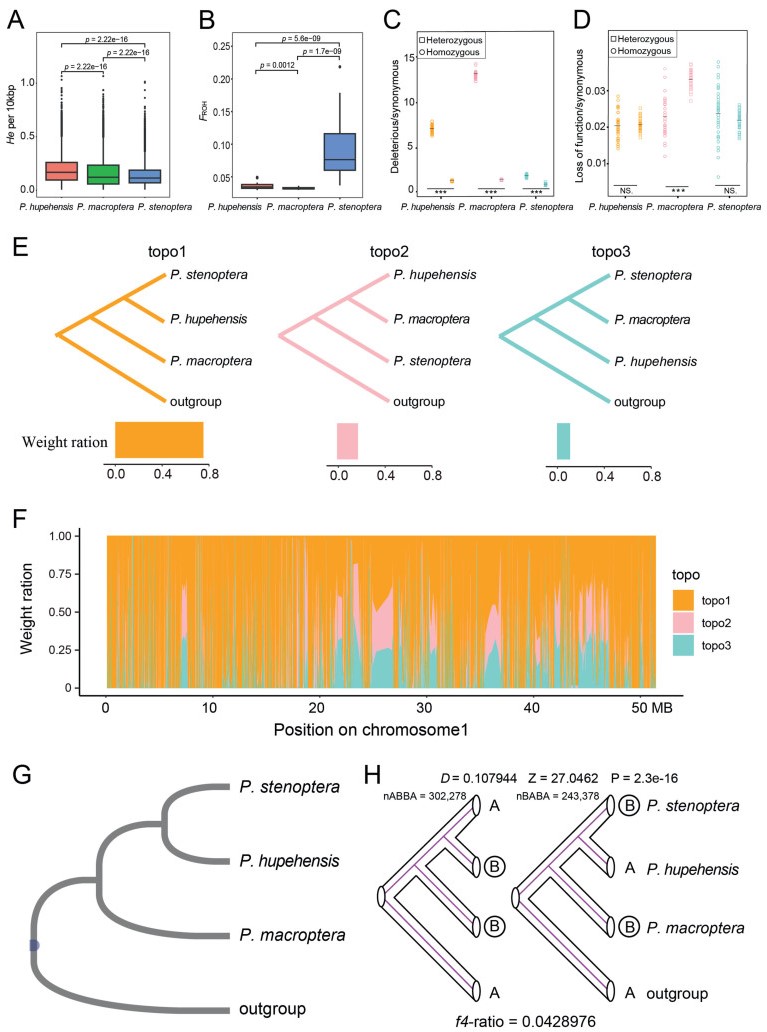

3.5. Inbreeding and accumulation putatively deleterious mutationsGenome-scale heterozygosity was lower (He = 0.12 per 10 kb) and inbreeding levels were higher (FROH = 0.16) in individuals of Pterocarya stenoptera than in individuals of P. hupehensis or P. macroptera. The highest levels of genome-scale heterozygosity were found in P. hupehensis (He = 0.17 per 10 kb; FROH = 0.09); the lowest levels of inbreeding were found in P. macroptera (He = 0.14 per 10 kb; FROH = 0.02) (Fig. 5A and B).

|

| Fig. 5 Gene introgression and genetic load in three species. (A) Comparisons of genome heterozygosity (He). (B) Estimates of individual genome-based inbreeding (FROH). (C–D) Ratio of derived deleterious (C) and loss of function (D) variants to synonymous variants in homozygous (circle) and heterozygous (square) tracts per individual. Horizontal bars denote average values. P values between homozygotes and heterozygotes for each species were obtained by Student's t test, asterisks indicate degree of significance (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (E) Three possible topologies. Histogram below represents the average weights of the three possible topologies across the genome. (F) Topology weightings for 10 KB windows plotted across Chromosome1, with loess smoothing. (G) Hypothetical species tree. (H) ABBA-BABA analysis between three species. D-statistic was used to assess the imbalance of the pattern of ABBA and BABA loci. Non-zero D-statistic implies gene flow. Z-value was used to measure the significance of statistics. P value indicates the level of significance that deviates from zero. f4-ratio indicates the proportion of gene introgression. |

Patterns of mutation load were examined by classifying coding sequence variants as synonymous, deleterious, and loss-of-function (LoF). Our analyses predicted that SNPs 261,914 (Pterocarya stenoptera), 276,602 (P. hupehensis), and 265,490 (P. macroptera) were potentially mildly deleterious (deleterious) mutations. In addition, our analyses predicted that SNPs 5317 (P. stenoptera), 7257 (P. hupehensis) and 6548 (P. macroptera) were putatively strongly deleterious (LoF). We found that the ratios of deleterious to synonymous variants were much higher in P. macroptera than in P. hupehensis or P. stenoptera (Fig. 5C and D). In all species, the ratio of deleterious/synonymous variants was higher at homozygous versus heterozygous sites. At heterozygous sites, the ratio of LoF to synonymous variants was significantly higher than that of homozygous sites in P. macroptera, with no significant differences in the other two species.

3.6. Evidence for past introgressionWe tested whether the speciation process for each species was accompanied by past introgression due to hybridization. First, we explored the phylogenetic relationships of the three species using TWISST (Martin and Van Belleghem, 2017). Among three possible species topologies, the most common topology (Topo1) had a genome-wide frequency of 75% (Figs. 5E and F, S16), which shared the same topology as the ML tree constructed over the entire nuclear genome. Topo2 indicates that P. hupehensis and P. macroptera are sister taxa with a genome-wide frequency of 20%, whereas Topo3 indicates that P. stenoptera and P. macroptera are sister taxa with a genome-wide frequency of 5%.

To assess whether the extensive discordances among local topologies were mainly due to incomplete lineage sorting and/or interspecific gene flow, we systematically tested for signatures of introgression by calculating Patterson's D and f4 admixture ratio (f4-ratio) statistics (Patterson et al., 2012). We calculated D and f4-ratio for all combinations of the three species using Juglans mandshurica as the outgroup. After performing standard block-jackknife procedures, our analysis indicated that the (((P. stenoptera, P. hupehensis), P. macroptera, O) trio had a significant D value at P < 0.001 (Fig. 5G and H). After ordering P1 and P2 to let nABBA > nBABA, D and f4-ratio statistics were always positive, showing introgression between P. hupehensis and P. macroptera. The extent of genome-wide introgression and the admixture proportion estimated by D and f4-ratio was 4.29%.

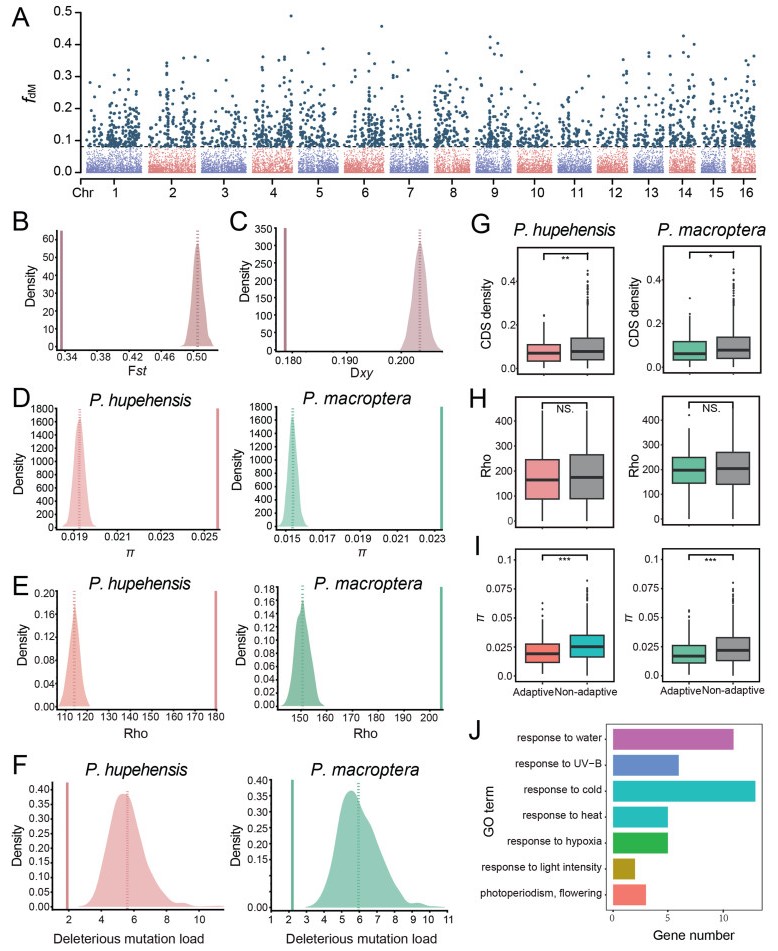

3.7. Identification of introgressed regions and inferring their functional significanceFor species pairs with significant D statistic comparisons, we further localized introgressed regions by calculating both fd and fdM statistics (Malinsky et al., 2015; Martin et al., 2015), which are more useful for locating introgressed loci in small genomic regions compared with D statistics. To identify regions of introgression, we used the results of fdM statistic (a modified version of fd that is symmetrically distributed around zero under the null hypothesis of no introgression). Introgressed regions were defined as the windows of highest fdM that summed to the genomic proportion estimated from the f4-ratio. We identified 1832 introgressed windows (Fig. 6A). Next, we assessed genomic characteristics and patterns of selection acting on these regions. Contrary to expectations for the occurrence of interspecific introgression, the introgressed regions, showed significantly lower interspecific genetic divergence (Fst and Dxy, between P. hupehensis and P. macroptera) and higher intraspecific nucleotide diversity in P. hupehensis and P. macroptera species than expected at random (Fig. 6D). We also found that the introgressed regions were significantly concentrated in genomic regions with higher recombination (Fig. 6E). In addition, we assessed the deleterious mutation load by calculating the ratio of deleterious (including LoF) to synonymous variants. We found a reduced burden of deleterious mutations in introgressed regions in both P2 and P3 species than expected at random (Fig. 6F).

|

| Fig. 6 Genomic characteristics of the putative introgressed regions between Pterocarya hupehensis and P. macroptera. (A) Manhattan plot showing the fdM values across genome. (B–C) Diagram showing the genetic differences. Fst (B) and Dxy (C) between introgressed regions (solid line) and the distribution resulting from the 1000 randomizations (dashed line: average across randomizations). (D–F) Diagrams show the nucleotide diversity (D), recombination rate (E) and deleterious mutation load (F) between the introgressive regions and 1000 random replicates for P. hupehensis and P. macroptera, respectively. The dotted line represents the average of the distribution of 1000 replicates, and the straight line represents the average of the results of the introgressed area. (G–I) Comparison of coding density (G) recombination rate (H) and nucleotide diversity (I) in the adaptive and non-adaptive introgressive regions of P. hupehensis and P. macroptera, respectively. Significance between adaptive and nonadaptive introgressed regions within each species was appraised using Student's t test and the significance is indicated by asterisks: ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, nsP > 0.05. (J) Functional annotation of environment-related genes in adaptive introgressive regions. |

To detect which candidate introgressed regions were affected by positive selection, we overlapped the regions of positive selection in P. hupehensis and P. macroptera according to XP-EHH and the previously identified introgressed regions. We identified 269 candidate introgressed windows (182 genes) in P. hupehensis and 199 candidate introgressed windows (158 genes) in P. macroptera affected by positive selection (Fig. S17). We suggest these introgressed regions are adaptive. A comparison of adaptive and nonadaptive introgressed regions in P2 and P3 species revealed significantly lower coding density and nucleotide diversity in adaptive introgressed regions (Fig. 6G and I). These results further support strong signatures of positive selection in these candidate regions and that they are likely to be genuinely adaptive. Lastly, we investigated whether genes located in the candidate regions of adaptive introgression were related to environmental adaptations. We identified a set of adaptive, introgressed genes for which orthologs have been shown to be involved in responses to water deprivation (TPLC2, CYCH; 1, LUH, bHLH112), cold (TPLC2, GLX1), UV-B (TLP-3), decreased oxygen levels (LUH), environmental stimuli (ABC1, bHLH112), response to blue light (CYCH; 1), cellular responses to light stimulus (ABC1), and DNA damage (LUH). These results indicate that gene flow does indeed promote the environmental adaptation of woody plants (Fig. 6J and Table S8). Furthermore, we overlapped the introgressed genes according to environmentally associated genes (RDA analysis) and identified 168 candidate genes (Fig. S17). Among these, the homologs of 12 genes have been shown to participate in responses to UV-B (RPA1D), cold (MED18, MEKK1), water deprivation (BAM1), hypoxia (NLM2), heat (KU70), light stimulus (ABC1), oxidative stress (MTK), photoperiodism (GAS41), cellular response to DNA damage stimulus (RPA1D, KU70, PARP3, ICA1, ATRAD21.3) and DNA repair (RPA1D, KU70, PARP3, ATRAD21.3) (Table S9).

4. Discussion 4.1. Genomic basis of ecological divergence and climatic adaptationEast Asian flora is not only the most diverse temperate flora in the world, but also the most important glacial refuge for Tertiary relict woody plants (Qiu et al., 2011), providing a unique opportunity for studying the evolutionary history and environmental adaptation of extant woody plants (Song et al., 2020a). In this study, we selected Pterocarya stenoptera, P. hupehensis and P. macroptera, which grow at different elevations in the Qinling-Daba Mountains, occupy significantly different niches, and display obvious differences in morphological characters. To analyze the responses of the three species to the climate and environmental changes in East Asia, we analyzed the population dynamic history. These three species, with sympatric distribution, showed different population dynamic changes. P. macroptera showed more intense population contraction and expansion events during glacial and interglacial periods, which may be attributed to its higher elevational distribution. P. stenoptera was less affected by the glacial and interglacial, which may be attributed to its lower elevational distribution (Zhang et al., 2024). P. hupehensis also showed certain population contraction and expansion, but was less affected than P. macroptera. These findings indicate that the three species occupied different ecological niches in the past and adapted to different ecological environments.

To explore the adaptive basis of the three species to heterogeneous environments, genetic differentiation analysis was performed. We identified genes involved in species divergence that contribute to environmental adaptation, including PIEZO1 (Waadt et al., 2022), WRKY39 (Chen et al., 2012), TOR (Inaba and Nagy, 2018), FLO10 (Singh et al., 2015), RAF6 (Wang et al., 2023a), VDAC3 (Li et al., 2013), RAF15 (Virk et al., 2015), ROF1 (Lefa et al., 2024) and DEK1 (Demko et al., 2024). WRKY39, which differed between Pterocarya stenoptera and P. macroptera, is related to cold stress (Chen et al., 2012), whereas VDAC3, which also responds to cold stress (Li et al., 2013), differed between P. hupehensis and P. macroptera. These gene differences correspond exactly to environmental and phenotypic differences. RAF6, which differed between P. stenoptera and P. macroptera, responds to changes in oxygen (Wang et al., 2023b). Similarly, RAF15, which differed between P. hupehensis and P. macroptera, regulates stomates and is responsive to oxygen concentration (Virk et al., 2015), possibly reflecting differences in adaptation to elevation among the species. The WRKY gene family plays important roles in transcriptional reprogramming associated with plant stress responses. WRKY proteins often respond to several stress factors, and may participate in the regulation of several seemingly disparate processes, e.g., as a negative or positive regulator (Ling et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012; Li et al., 2017). VDAC3 negatively regulates plant cold responses during germination and seedling development in Arabidopsis and interacts with the calcium sensor CBL1 (Li et al., 2013). The RAF family has been reported to be involved in oxygen level stress response, but it has also been found to be involved in a variety of non-biotic stress responses (Gao et al., 2008; Ning et al., 2010; Virk et al., 2015). Our data indicates these three genes influence species-specific adaptation and divergence in Pterocarya.

We also used environmental association analysis to identify candidate genes associated with environmental adaptation. Genetic differentiation analysis indicated that in Pterocarya stenoptera PIEZO1, which is reported to transduce mechanical signals (Waadt et al., 2022), is associated with environmental factors. In P. hupehensis, ACA4 (Yu et al., 2018), XDH1 (Watanabe et al., 2010), PPR40 (Kant et al., 2024), and LEUNIG (Wang et al., 2022) are reported to participate in responding to cold or drought stress, while SBE2.2 and PHOT2 participate in light signal response (Bossi et al., 2009; Krzeszowiec et al., 2023), SSADH1 is reported to respond to heat and light stimulation (Balfagón et al., 2022). In P. macroptera, RECQI1 (Vandepoele et al., 2005), CYCH; 1 (Zhou et al., 2013) participate in response to cold and drought stress, RBOHB responds to heat (Wang et al., 2014), MED17 participates in DNA damage response (Giustozzi et al., 2022), GCN2 responds to light stimulation (Lu, 2016), and DEG7 participates in photosystem repair (Sun et al., 2010). The candidate genes identified in this study provide a better theoretical basis for the study of ecological adaptability and conservation of quaternary relict woody plants in East Asia.

Enrichment analysis showed that the 64 candidate genes identified by RDA are significantly enriched in cellular response to DNA damage stimulus and DNA repair (Table S7; Figs. 4F and S15). Environmental stresses such as high temperature, drought, and ultraviolet radiation increase the risk of DNA damage (Li et al., 2021a, 2021b; Ye et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2023). Through effective DNA repair mechanisms, plants can better cope with these stresses, reducing the interference of DNA damage with cellular functions, thereby enhancing stress resistance (Williams and Schumacher, 2017; Zhao et al., 2024). Pterocarya stenoptera grows in low-elevation, high-temperature areas, while P. macroptera grows in high-elevation areas with drought and strong ultraviolet radiation (Wang et al., 2023a; Zhang et al., 2020a, 2023). Effective DNA repair is an important pathway for both species to adapt to their respective environmental stresses (Spampinato, 2017). The DNA damage response pathway can activate a series of downstream signaling pathways, regulate gene expression, and help plants adapt to environmental stresses. These signaling pathways can regulate the expression of antioxidant enzymes, the progression of the cell cycle, and apoptosis, thereby enhancing the adaptive capacity of plants (Huang and Zhou, 2021). However, while our work provides putative genomic basis of ecological-adaptive divergence, none of these genes have been experimentally validated on the ontology (Qian et al., 2019; Ye et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2023). Hence, further experimental work is needed to better understand the genomic basis and mechanisms underlying ecological divergence and climatic adaptation (Li et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020a; Geng et al., 2024a,b).

4.2. Genomic characteristics and patterns in regions of gene introgressionGene introgression plays an important role in the environmental adaptation of organisms (Bellucci et al., 2023; Xiao et al., 2023), but how genetic and evolutionary forces shape genome evolution after introgression occurs is an unsolved problem. After hybridization, an introgressed block embedded in the genome is broken by recombination in subsequent generations. It is expected that regions of the genome with low recombination will also contain less evidence of introgression because sites affected by introgression should also contain favorable variants showing signs of selection (Schumer et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2022). Next, if introgression introduces new beneficial variation and plays an important role in adaptation, then the introgressed regions would be marked by selective sweeps (Suarez-Gonzalez et al., 2018; Leroy et al., 2020). Finally, regions of adaptive introgression would be expected to contain lower gene density because genomic region with higher gene density also tend to have more deleterious mutations (Morales-Cruz et al., 2021; Feng et al., 2023). Assessing these issues is critical to our understanding of the consequences of evolution and the potential of hybridization to generate new adaptive variation.

This study found significant gene introgression between Pterocarya hupehensis and P. macroptera. Furthermore, the introgressed regions were located in areas of the genome with high recombination, confirming the positive correlation between introgression and genomic recombination, a result reported in other taxa as well (Martin et al., 2019; Christmas et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022). These findings are consistent with the theoretical expectation that in subsequent repeated backcrosses after the initial hybridization, the infused alleles (mainly harmful mutations) in the genome will be retained by rapidly decomposing due to selection against harmful foreign alleles in a high recombination region (Feng et al., 2023). Genetic differentiation of introgressed regions is lower than that of other regions of the genome and introgressed regions will exhibit higher genetic diversity. Typically, many genes in introgressed regions are involved in environmental adaptation, increasing the likelihood that introgression introduces beneficial adaptive variation. Introgressed regions also increase genetic variance and genetic diversity, thereby alleviating the bottleneck effect arising from speciation (Stubbs et al., 2024). Genetic diversity in an adaptive introgressed region is expected to be lower than that in a non-adaptive introgressed region because adaptive regions are subject to higher frequency selective sweeps. We found a reduced burden of deleterious mutations in introgressed regions, which further confirms that introgression can introduce adaptive variants and reduces the genetic load in the recipient population. We also found that in Pterocarya, gene density in regions of adaptive introgression was significantly lower than the density in introgressed regions that were non-adaptive, supporting the importance of gene density in genome evolution, and the current model that gene-rich introgressed regions that contain many deleterious mutations and are unlikely to be subject to strong positive selection. However, there are still many unresolved questions regarding gene introgression, especially whether the distribution of introgressed regions along the genome and the extent and patterns of introgression are influenced by ecological factors. Fu et al. (2023) found that in two closely related species, Quercus acutissima and Q. variabilis, introgressed regions are widely distributed across the entire genome. Introgression is influenced by genetic differences between paired populations and the environmental similarities in which they live. Moreover, introgression may confer adaptation to populations by introducing allelic variation in cis-regulatory elements (Chen et al., 2024), particularly through the insertion of transposable elements (Fu et al., 2023), thereby altering the regulation of stress-related genes. However, research on this topic is still very limited, and there are too many uncertainties in our understanding of the process of gene introgression.

4.3. The important role of gene introgression in environmental adaptationQuaternary relict woodlands in East Asia have important ecological and economic value, yet most of these species are at risk of extinction (Xu et al., 2024). Pterocarya macroptera has scales that protect its buds in high-elevation environments. P. hupehensis has no bud scales and is distributed at elevations considerably higher than P. stenoptera, which also has no bud scales. How has P. hupehensis adapted to a harsher ecological environment? This study used population genomics to confirm significant gene flow between P. macroptera and P. hupehensis, with 4.29% of the genome of P. hupehensis originating from introgression. ABBA-BABA analysis and functional annotation revealed that the introgressed regions contained many genes related to environmental responses. Further, selective sweep analysis identified seven candidate adaptive genes. One candidate adaptive gene, LUH, can induce the expression of genes for tolerance of abiotic stress. Its protein forms a complex with SLK1/SLK2 to negatively regulate the expression of genes that reduce abiotic stress tolerance (Shrestha et al., 2014); The PLC2 gene is transcriptionally induced by stresses such as salt, cold, and dehydration (Kanehara et al., 2015). CYCH; 1 regulates drought stress responses and blue light-induced stomatal opening by inhibiting reactive oxygen species accumulation in Arabidopsis (Zhou et al., 2013). The expression of GLX1 gene in Arabidopsis thaliana is moderately induced under salt, drought, cold, and strong light stress, and the expression of GLX1 in rice is also upregulated under salt stress (Dorion et al., 2021); TLP-3 is involved in both the intermediate and high-level UV-B pathway (Ulm et al., 2004). bHLH112 is a transcriptional activator that regulates the expression of genes via binding to their GCG- or E-boxes to mediate physiological responses, including proline biosynthesis and ROS scavenging pathways, to enhance stress tolerance (Liu et al., 2015). ABC1 encodes a chloroplast protein that participates in the photorespiratory stress response (Yang et al., 2012).

We identified nine key adaptive introgressive genes by integrating introgressive genes with environment-related genes, including those involved in responses to UV-B (RPA1D, Aklilu et al., 2014), cold (MED18, Zhang et al., 2021; MEKK1, Furuya et al., 2013), water deprivation (BAM1, Jahan et al., 2024), hypoxia (NLM2, Shukla et al., 2020), heat (KU70, Li et al., 2003), light stimulus (ABC1, Yang et al., 2016), oxidative stress (MTK, Matsushita et al., 2020), photoperiodism (GAS41, Zacharaki et al., 2012). We concluded that Pterocarya hupehensis received genetic resources from P. macroptera, including many positive selection genes in response to abiotic stress. Previous studies have also shown that adaptive introgression occurs between species or populations with altered environmental gradients, e.g., white oaks (Leroy et al., 2020; Oney-Birol et al., 2018) and rainbowfish (Brauer et al., 2023).

The three species of this study are distributed at different elevational gradients. Pterocarya macroptera grows at the highest elevation and lives in an extremely harsh environments (Wang et al., 2023a), with a relatively limited growth range. P. stenoptera has a lower elevation and a broader distribution range (Li et al., 2022). P. hupehensis is mainly distributed in the intermediate regions between the other two species. Our research provides evidence that introgression has promoted the adaptive response of P. hupehensis to drought, cold, UV-B, oxygen depletion, light stimulation, and DNA damage. Therefore, we hypothesize that the adaptation of P. hupehensis to higher elevations and different ecological niches may be attributed in part to introgression from P. macroptera.

Pterocarya macroptera was found to have the lowest FROH, whereas P. stenoptera has the highest FROH, indicating that P. macroptera has the lowest degree of inbreeding. P. hupehensis, distributed between the other two species, has the potential to receive gene introgression from P. macroptera. This may be one reason why P. hupehensis can receive gene introgression from P. macroptera. P. hupehensis has the highest genetic diversity and the highest genome-scale He compared to the other two species, which may be attributed to gene introgression from P. macroptera. Numerous previous studies have confirmed that gene introgression can significantly increase species genetic diversity, thereby promoting adaptation to more diverse environments (Abbott et al., 2016; Leroy et al., 2020; Martha et al., 2021). This also adds new evidence that gene introgression has facilitated the environmental adaptation of P. hupehensis. In addition, we found that the burden of deleterious mutations in introgressed regions of P. hupehensis was lower than expected at random, indicating that gene introgression from P. macroptera has indeed reduced the deleterious mutations in P. hupehensis. Previous studies have shown that gene introgression from populations with larger effective population sizes tends to reduce genetic load, while gene introgression from populations with smaller effective population sizes tends to increase genetic load (Harris and Nielsen 2016; Juric et al., 2016). The results of SMC++ showed that the effective population size of P. macroptera was always larger than that of P. hupehensis in most of the past history (except for the more influential glacial periods), especially in the population expansion stage of interglacial periods, where the species were more prone to overlapping distribution areas and gene exchange. PSMC analysis of recent effective population sizes also supports this conclusion. Similarly, other studies on Pterocarya hupehensis have revealed strikingly similar population dynamic histories (Lu et al., 2024). Therefore, gene introgression reducing genetic load is also an important piece of evidence for enhancing the environmental adaptability of P. hupehensis. However, because this study did not obtain population materials from a sufficiently wide range for each species, the comparative analysis of genetic load at the species level remains inadequate. Thus, the relationship between genetic load, inbreeding levels, and the intensity of selective sweeps requires further verification in future research. Nevertheless, based on the above analysis, we can infer that gene introgression from P. macroptera has, to some extent, facilitated the environmental adaptation of P. hupehensis.

AcknowledgementsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32370386, 32070372, and 32200295), Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of Shaanxi Province (2023-JC-JQ-22), Basic Research Project of Shaanxi Academy of Fundamental Science (22JHZ005), Shaanxi Key Research and Development Program (2024NC-YBXM-064), Science and Technology Program of Shaanxi Academy of Science (2023K-49, 2023K-26, and 2019K-06), Shaanxi Forestry Science and Technology Innovation Key Project (SXLK2023-02-20), Qinling Hundred Talents Project of Shaanxi Academy of Science (Y23Z619F17).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Fangdong Geng: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Miaoqing Liu: Software, Methodology, Investigation. Luzhen Wang: Software, Methodology, Formal analysis. Xuedong Zhang: Software, Methodology, Investigation. Jiayu Ma: Software, Formal analysis. Hang Ye: Resources, Investigation, Formal analysis. Keith Woeste: Writing – original draft, Resources, Formal analysis. Peng Zhao: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Data availability statement

Genome data of Pterocarya stenoptera have been deposited in the NCBI accession number: PRJNA992759. All raw sequence in this study have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under BioProject: PRJNA1086683. All morphological data have been deposited in https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/_i_Pterocarya_stenoptera_i_phenotype_data/26233322?file=47543078.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2025.04.002.

Abbott, R.J., Barton, N.H., Good, J.M., 2016. Genomics of hybridization and its evolutionary consequences. Mol. Ecol., 25: 2325-2332. DOI:10.1111/mec.13685 |

Aklilu, B.B., Soderquist, R.S., Culligan, K.M., 2014. Genetic analysis of the replication protein a large subunit family in Arabidopsis reveals unique and overlap roles in DNA repair, meiosis and DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res., 42: 3104-3118. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkt1292 |

Alexander, D.H., Novembre, J., Lange, K., 2009. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res., 19: 1655-1664. DOI:10.1101/gr.094052.109 |

Balfagón, D., Gómez-Cadenas, A., Rambla, J.L., et al., 2022. γ-Aminobutyric acid plays a key role in plant acclimation to a combination of high light and heat stress. Plant Physiol., 188: 2026-2038. DOI:10.1093/plphys/kiac010 |

Bankevich, A., Nurk, S., Antipov, D., et al., 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol., 19: 455-477. DOI:10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 |

Bellucci, E., Benazzo, A., Xu, C., et al., 2023. Selection and adaptive introgression guided the complex evolutionary history of the European common bean. Nat. Commun., 14: 1908. DOI:10.1038/s41467-023-37332-z |

Bossi, F., Cordoba, E., Dupré, P., et al., 2009. The Arabidopsis ABA-INSENSITIVE (ABI) 4 factor acts as a central transcription activator of the expression of its own gene, and for the induction of ABI5 and SBE2.2 genes during sugar signaling. Plant J., 59: 359-374. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03877.x |

Brauer, C.J., Sandoval-Castillo, J., Gates, K., et al., 2023. Natural hybridization reduces vulnerability to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change, 13: 282-289. http://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/aafd40eaf02fa60863096095fe9ab2241dfc7df2. |

Browning, B.L., Browning, S.R., 2009. A unified approach to genotype imputation and haplotype-phase inference for large data sets of trios and unrelated individuals. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 84: 210-223. DOI:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.005 |

Cao, T., Li, Q., Huang, Y., et al., 2023. plotnineSeqSuite: a Python package for visualizing sequence data using ggplot2 style. BMC Genomics, 24: 585. DOI:10.1186/s12864-023-09677-8 |

Cao, Y., Zhu, S.S., Chen, J., et al., 2020. Genomic insights into historical population dynamics, local adaptation, and climate change vulnerability of the East Asian Tertiary relict Euptelea (Eupteleaceae). Evol. Appl., 13: 2038-2055. DOI:10.1111/eva.12960 |

Capblancq, J., Forester, B., 2021. Redundancy analysis: a swiss army knife for landscape genomics. Methods Ecol. Evol., 12: 2298-2309. DOI:10.1111/2041-210x.13722 |

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J.M., Gabaldón, T., 2009. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics, 25: 1972-1973. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348 |

Chen, H., Patterson, N., Reich, D., 2010. Population differentiation as a test for selective sweeps. Genome Res., 20: 393-402. DOI:10.1101/gr.100545.109 |

Chen, L., Song, Y., Li, S., et al., 2012. The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant abiotic stresses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1819: 120-128. DOI:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.09.002 |

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y., et al., 2018. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics, 34: i884-i890. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 |

Chen, X., Hu, X., Li, G., et al., 2024. Genetic regulatory perturbation of gene expression impacted by genomic introgression in fiber development of allotetraploid cotton. Adv. Sci., 11: 2401549. DOI:10.1002/advs.202401549 |

Christmas, M.J., Jones, J.C., Olsson, A., et al., 2021. Genetic barriers to historical gene flow between cryptic species of alpine bumblebees revealed by comparative population genomics. Mol. Biol. Evol., 38: 3126-3143. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msab086 |

Cingolani, P., Platts, A., Wang, L., et al., 2012. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6, 80-92.

|

Danecek, P., Auton, A., Abecasis, G., et al., 2011. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics, 27: 2156-2158. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330 |

Demko, V., Belova, T., Messerer, M., et al., 2024. Regulation of developmental gatekeeping and cell fate transition by the calpain protease DEK1 in physcomitrium patens. Commun. Biol., 7: 261. DOI:10.1038/s42003-024-05933-z |

DePristo, M.A., Banks, E., Poplin, R., et al., 2011. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet., 43: 491-498. DOI:10.1038/ng.806 |

Dorion, S., Ouellet, J.C., Rivoal, J., 2021. Glutathione metabolism in plants under stress: beyond reactive oxygen species detoxification. Metabolites, 11: 641. DOI:10.3390/metabo11090641 |

Dormann, C.F., Elith, J., Bacher, S., et al., 2013. Collinearity: a review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography, 36: 27-46. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2012.07348.x |

Durand, E.Y., Patterson, N., Reich, D., et al., 2011. Testing for ancient admixture between closely related populations. Mol. Biol. Evol., 28: 2239-2252. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msr048 |

Ellis, N., Smith, S.J., Pitcher, C.R., 2012. Gradient forests: calculating importance gradients on physical predictors. Ecology, 93: 156-168. DOI:10.1890/11-0252.1 |

Emms, D.M., Kelly, S., 2015. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol., 16: 157. DOI:10.1186/s13059-015-0721-2 |

Feng, C., Wang, J., Liston, A., et al., 2023. Recombination variation shapes phylogeny and introgression in wild diploid strawberries. Mol. Biol. Evol., 40: msad049. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msad049 |

Feng, Y., Comes, H.P., Chen, J., et al., 2024. Genome sequences and population genomics provide insights into the demographic history, inbreeding, and mutation load of two 'living fossil' tree species of Dipteronia. Plant J., 117: 177-192. DOI:10.1111/tpj.16486 |

Fick, S.E., Hijmans, R.J., 2017. WorldClim 2: new 1km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol., 37: 4302-4315. DOI:10.1002/joc.5086 |

Fitak, R.R., 2021. OptM: estimating the optimal number of migration edges on population trees using Treemix. Biol. Methods Protoc., 6: bpab017. DOI:10.1093/biomethods/bpab017 |

Fu, R., Zhu, Y., Liu, Y., et al., 2023. Genome-wide analyses of introgression between two sympatric Asian oak species. Nat. Ecol. Evol., 6: 924-935. http://www.nstl.gov.cn/paper_detail.html?id=9357d93606bd52cabe241efc3fff818f. |

Furuya, T., Matsuoka, D., Nanmori, T., 2013. Phosphorylation of Arabidopsis thaliana MEKK1 via Ca2+ signaling as a part of the cold stress response. J. Plant Res., 126: 833-840. DOI:10.1007/s10265-013-0576-0 |

Gao, F., Ming, C., Hu, W.J., et al., 2016. New software for the fast estimation of population recombination rates (FastEPRR) in the genomic era. G3-Genes Genom. Genet., 6: 1563-1571. DOI:10.1534/g3.116.028233 |

Gao, M., Liu, J., Bi, D., et al., 2008. MEKK1, MKK1/MKK2 and MPK4 function together in a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to regulate innate immunity in plants. Cell Res., 18: 1190-1198. DOI:10.1038/cr.2008.300 |

Geng, F.D., Lei, M.F., Zhang, N.Y., et al., 2024a. Demographical complexity within walnut species provides insights into the heterogeneity of geological and climatic fluctuations in East Asia. J. Syst. Evol., 62: 1037-1053. DOI:10.1111/jse.13061 |

Geng, F.D., Xie, J.H., Xue, C., et al., 2022. Loss of innovative traits underlies multiple origins of Aquilegia ecalcarata. J. Syst. Evol., 60: 1291-1302. DOI:10.1111/jse.12808 |

Geng, F.D., Zhang, X.D., Ma, J.Y., et al., 2024b. Genome assembly and winged fruit gene regulation of Chinese wingnut: insights from genomic and transcriptomic analyses. Genom. Proteom. Bioinf.. DOI:10.1093/gpbjnl/qzae087 |

Giustozzi, M., Freytes, S.N., Jaskolowski, A., et al., 2022. Arabidopsis mediator subunit 17 connects transcription with DNA repair after UV-B exposure. Plant J., 110: 1047-1067. DOI:10.1111/tpj.15722 |

Griffiths, J.S., Kawji, Y., Kelly, M.W., 2021. An experimental test of adaptive introgression in locally adapted populations of splash pool copepods. Mol. Biol. Evol., 38: 1306-1316. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msaa289 |

Guindon, S., Dufayard, J.-F., Lefort, V., et al., 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol., 59: 307-321. DOI:10.1093/sysbio/syq010 |

Harris, K., Nielsen, R., 2016. The genetic cost of Neanderthal introgression. Genetics, 203: 881-891. DOI:10.1534/genetics.116.186890 |

Hoang, D.T., Chernomor, O., von Haeseler, A., et al., 2018. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol., 35: 518-522. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msx281 |

Huang, R., Zhou, P., 2021. DNA damage repair: historical perspectives, mechanistic pathways and clinical translation for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther., 6: 254. DOI:10.1038/s41392-021-00648-7 |

Inaba, J.I., Nagy, P.D., 2018. Tombusvirus RNA replication depends on the TOR pathway in yeast and plants. Virology, 519: 207-222. DOI:10.1016/j.virol.2018.04.010 |

Jahan, M.S., Yang, J.Y., Althaqafi, M.M., et al., 2024. Melatonin mitigates drought stress by increasing sucrose synthesis and suppressing abscisic acid biosynthesis in tomato seedlings. Physiol. Plantarum, 176: e14457. DOI:10.1111/ppl.14457 |

Jesse, R.L., Emily, B.J., Geoffrey, P.M., 2023. Genotype-environment associations to reveal the molecular basis of environmental adaptation. Plant Cell, 35: 125-138. DOI:10.1093/plcell/koac267 |

Jin, J.J., Yu, W.B., Yang, J.B., et al., 2020. GetOrganelle: A fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol., 21: 241. DOI:10.1186/s13059-020-02154-5 |

Johnson, M.G., Gardner, E.M., Liu, Y., et al., 2016. HybPiper: extracting coding sequence and introns for phylogenetics from high-throughput sequencing reads using target enrichment. Appl. Plant Sci., 4: apps.1600016. DOI:10.3732/apps.1600016 |

Junier, T., Zdobnov, E.M., 2010. The Newick utilities: high-throughput phylogenetic tree processing in the UNIX shell. Bioinformatics, 26: 1669-1670. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq243 |

Juric, I., Aeschbacher, S., Coop, G., 2016. The strength of selection against Neanderthal introgression. PLoS Genet., 12: e1006340. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006340 |

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B.Q., Wong, T.K.F., et al., 2017. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods, 14: 587-589. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.4285 |

Kanehara, K., Yu, C.Y., Cho, Y., et al., 2015. Arabidopsis AtPLC2 is a primary phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C in phosphoinositide metabolism and the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. PLoS Genet., 11: e1005511. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005511 |

Kant, K., Rigó, G., Faragó, D., et al., 2024. Mutation in Arabidopsis mitochondrial pentatricopeptide repeat 40 gene affects tolerance to water deficit. Planta, 259: 78. DOI:10.1007/s00425-024-04354-w |

Katoh, K., Standley, D.M., 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol., 30: 772-780. DOI:10.1093/molbev/mst010 |

Keightley, P.D., Jackson, B.C., 2018. Inferring the probability of the derived vs. the ancestral allelic state at a polymorphic site. Genetics, 209: 897-906. DOI:10.1534/genetics.118.301120 |

Krzeszowiec, W., Lewandowska, A., Lyczakowski, J.J., et al., 2023. Two types of GLR channels cooperate differently in light and dark growth of Arabidopsis seedlings. BMC Plant Biol., 23: 358. DOI:10.1186/s12870-023-04367-9 |

Lefa, P., Samiotaki, M., Farmaki, T., 2024. Proteome analysis of the ROF-FKBP mutants reveals functional relations among heat stress responses, plant development, and protein quality control during heat acclimation in Arabidopsis thaliana. ACS Omega, 9: 2391-2408. DOI:10.1021/acsomega.3c06773 |

Leroy, T., Louvet, J.M., Lalanne, C., et al., 2020. Adaptive introgression as a driver of local adaptation to climate in European white oaks. New Phytol., 226: 1171-1182. DOI:10.1111/nph.16095 |

Letunic, I., Bork, P., 2021. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res., 49: W293-W296. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkab301 |

Li, G.C., He, F., Shao, X., et al., 2003. Adenovirus-mediated heat-activated antisense Ku70 expression radiosensitizes tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res., 63: 3268-3274. http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Muneyasu_Urano2/publication/6963666_Adenovirus-mediated_heat-activated_antisense_Ku70_expression_radiosensitizes_tumor_cells_in_vitro_and_in_vivo/links/54c771eb0cf22d626a3675ed.pdf. |

Li, H., Durbin, R., 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics, 25: 1754-1760. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 |