Major earthquakes with the characteristics of strong suddenness, severe destructivity and unpredictability often cause significant human life and property losses. For example, the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake killed nearly 70000 people and brought direct economic losses of 692 billion Yuan (RMB) (Yuan, 2008). Understanding the physical mechanism of major earthquakes is very important for earthquake prediction and its disaster reduction. Although many scholars have made great efforts on earthquake prediction, the understanding about physical mechanisms still remains unclear and controversial (Kanamori and Brodsky, 2004; Chen, 2007; Lu et al., 2014).

According to focal depth (Brudzinski and Chen, 2005), earthquakes can be classified as “shallow earthquakes” with a depth less than 70 km, “intermediate earthquakes” with a depth 70~300 km, and “deep earthquakes” with a depth more than 300 km. Considering that high temperature and high pressure in the deep mantle may cause a difference of the physical mechanism of major earthquakes, scholars have put forward a series of hypotheses for different types of earthquakes, trying to explain the cause of earthquakes.

1.1 Research Status of the Physical Mechanism of Shallow EarthquakesA range of mechanisms has been proposed for earthquakes, including elastic rebound hypothesis (Reid, 1910), stick-slip hypothesis (Brace and Byerlee, 1966; Scholz, 1998) and rock failure hypothesis (Das and Aki, 1977; Wyss et al., 1981; Mei, 1995).

(1) Elastic rebound hypothesis

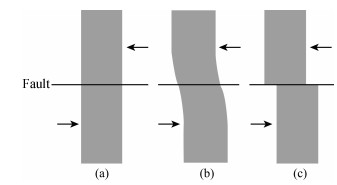

The hypothesis was proposed based on the horizontal movement of San Andreas Fault by Reid (1910) when studying the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. The hypothesis assumed that rock stratum undergoes elastic deformation under stress. When the stress exceeds the elastic strength of rock, the two sides of the fault rebound to its original state, leading to occurrence of a major earthquake (Fig. 1). It is easy to know that this hypothesis is only applicable to explain the occurrence of shallow earthquakes, but not intermediate and deep earthquakes, because major or great earthquakes will release huge energy and hence need enough room for bounce when they occur. However, no evidence at present indicates there is such a space in the deep earth (Griggs and Handin, 1960; Orowan, 1960). This hypothesis is contrary to the following observations. 1) If this hypothesis is established, the two sides of the fault will inevitably undergo large deformation to accumulate large elastic strain energy before a major earthquake. Otherwise, the major earthquake would not happen. However, this is not consistent with the observed fact. Modern GPS and high precision displacement measurement show that such a large deformation is not observed before the occurrence of some major earthquakes (Wu et al., 2013; Lei et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015). By contrary, when some major earthquakes occur, the dislocation of the fault can be observed due to rapid fault sliding, such as the surface rupture zone formed in the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake (Xu et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008). This fact shows that this hypothesis may reverse the causal relationship. In other words, the fault sliding can lead to dislocation, rather than this dislocation leads to fault instability (earthquake). 2) The hypothesis assumes that the seismic energy carriers (seismic source body) are the rocks on the two sides of the fault, and their load-bearing capacity is in the elastic range. Therefore, it cannot explain the preshock or foreshock events prior to the major earthquake.

|

Fig. 1 Schematic illustration of elastic rebound hypothesis (Reid, 1910; Jiang and Wu, 2012) (a) No elastic strain accumulation; (b) Strain accumulation (fault locking); (c) Elastic strain release. |

(2) Stick-slip hypothesis

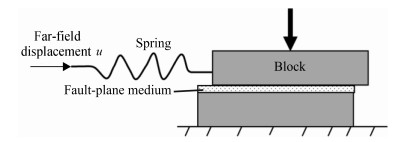

To explain the contradiction between the elastic rebound hypothesis and observations, Brace and Byerlee (1966) proposed that the physical mechanism of elastic rebound can be explained by the unsteady slip (stickslip) in the process of friction sliding. Obviously, the fault deformation in the elastic rebound hypothesis is transformed to the friction between two rock sliders by introducing the stick-slip concept (Liu, 2014), or the deformation of the slider is transformed to the slip along the fault. The currently widely accepted spring-block model (Fig. 2) presented by Byerlee (1978) is used to explain the stick-slip hypothesis. The fault displacement in this model is set as the friction movement of rigid blocks and deformation is set as expansion or contraction of spring. The reason why spring is introduced in the model is that an earthquake requires the release of elastic energy and elastic deformation is still necessary (Liu, 2014). It should be noted that the model could be used to describe the observed stick-slip phenomenon, but not be used to explain the occurrence of a major earthquake. It is easy to know that when explaining the mechanism of major earthquakes by the spring-block model, the sliders represent the rocks on the two sides of the fault, and the spring (testing machine in the laboratory experiment) represents the far-field loading displacement (u), i.e., the loading of the adjacent region (adjacent seismic zone) to the slider (seismic source body). When the source body is suddenly sliding beyond the friction strength, its entire energy will be converted into kinetic energy, friction work and friction heat energy because the seismic source body is rigid. Thus, the source body itself will not release elastic strain energy, implying that an earthquake does not occur. We can conclude from the above analysis that stick-slip hypothesis is not a development of the elastic rebound hypothesis but is a retrogression.

|

Fig. 2 Schematic illustration of spring-block model (modified after Byerlee (1978)) |

In addition, the stick-slip hypothesis exhibits certain inherent weaknesses. 1) Studies (Brace and Byerlee, 1966, 1970) have shown that temperature could significantly affect the stick-slip behavior. when the temperature in rocks exceeds 500 ℃, peristalsis or creep is much easier to occur than stick-slip. because the temperature of crust at the depth of more than 25 km is close to 500 ℃ (Collier et al., 2001; An and shi, 2007), the stick-slip hypothesis can be only used to explain the shallow tectonic earthquake within 25 km depth. 2) because the sliders are “bonded” before the earthquake, it is difficult for this hypothesis to interpret the observed preshock or foreshock events.

(3) Rock failure hypothesis

Earthquakes result from rock failures due to fault movement. Therefore, we should understand the earthquake mechanism from the angle of rock failure and clarify the energy accumulating carriers. For this reason, many scholars have proposed the barrier (Das and Aki, 1977), asperity (Wyss et al., 1981) and inclusion models including soft inclusion (Brady, 1974, 1975) and hard inclusion (Mei, 1995). Because the soft inclusion cannot accumulate high energy, this model cannot reasonably explain the occurrence of major earthquakes. Qin et al., (2010) developed the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system and suggested that the high energy accumulating carrier is the lock patch in the fault or plate subduction zone, i.e., the structural area on the fault plane with high strength that could release large seismic moment, such as hard inclusion, barrier, rock bridge and asperity (Fig. 3). This theory points out the possibility of coexisting of several lock patches with different strength and scales, emphasizes their successive and progressive failures, and reveals their accelerated failure rule, which is supported by many earthquake cases.

|

Fig. 3 Schematic illustration of locked patches in faults or subduction zones (modified after Toshihiro et al., (2003) and Ohnaka (2013)) |

Intermediate and deep earthquakes often occur near the convergence plate boundary and are closely related to plate movement and volcanic activity. Thus, it is important to study their physical mechanism for understanding the plate movement characteristics.

Sibson (1977, 1982) believed that the lower limit of the intraplate shallow earthquake hypocenter depth is consistent with the brittle-ductile transition zone. Thus, it is easy to understand that the shallow earthquake belongs to the brittle failure behavior. Because both intermediate and deep earthquakes occur at high pressure and temperature environment where ordinary brittle failures are thought to be impossible, it is now universally recognized that they may be attributed to different mechanisms, including the dehydration embrittlement, phase transition instability, shear melting and anticrack-associated faulting.

(1) Dehydration embrittlement

Raleigh and Paterson (1965) found by the high temperature experiments that under the action of smaller shear stress, serpentine dehydration causes reduction of the effective stress and strength, easily leading to brittle failure. More recently, Okazaki and Hirth (2016) observed that the lawsonite can also undergo dehydrationinduced brittle failure. During the subduction process, the temperature and pressure increase with the depth. When some temperature and pressure levels are satisfied, the dehydration reaction of minerals will occur (Mishra and Zhao, 2004; Gan et al., 2012). This hypothesis is mainly used to explain the origination of the intermediate earthquakes (Yu and Jin, 2006). Within the allowable error range, the antigorite’s dehydration boundary is consistent with the double-layered structure (Green et al., 2010). Thus, the hypothesis can well explain the distribution of the double-layered structure of intermediate earthquakes (Yamasaki and Seno, 2003). However, Chernak and Hirth (2010) found by the undrained experiments that the antigorite dehydration reaction apparently promotes more homogeneous and distributed deformation rather than the localized brittle failure. Thus, whether the dehydration effect is the mechanism of intermediate earthquake is still questionable.

(2) Phase transition instability

Bridgman (1945) proposed that the deep earthquakes are caused by the instability of the phase transition and believed that the volume of the main mineral olivine in mantle will drastically change when the phase transition occurs, resulting in an implosion giving rise to the deep earthquakes. Later, Kirby et al., (1991) and Silner et al., (1995) subsequently pointed out that the earth within the depth of 410~660 km is the highfrequency area of deep earthquakes, which coincides with the earth’s internal phase transition. However, this hypothesis has obvious drawbacks. 1) The seismic waves generated by implosion are isotropic and without S-wave, while the seismic waves generated by deep earthquakes have a strong double-couple source or shear component and strong S-wave (Dziewonski and Gilbert, 1974; Kawakatsu, 1991; Houston, 1993; Estabrook and Kind, 1996; Okal, 1996; Zhao, 2012). 2) The seismic wave pattern of deep earthquakes is contrary to the hypothesis that the volume shrinks sharply when the phase transition occurs (Kirby et al., 1991). 3) The phase transition of minerals requires certain temperature and pressure conditions, but the deep earthquakes occur inside the plates, where the temperature and pressure may not meet the phase transition requirements (described in Chapter 4). 4) The hypothesis cannot explain the phenomenon of repeated earthquakes (Wiens and Snider, 2001). 5) A sudden implosive change at phase transition can lead to earthquakes, which requires a certain dislocation space, but no evidence at present indicates the presence of such a space in the deep earth (Griggs and Handin, 1960; Orowan, 1960; Kirby et al., 1996). Up to now, a major number of M≥8.0 deep earthquakes have been recorded. Thus, this hypothesis can hardly explain the process of such major amount of energy accumulation and instantaneous release. 6) Two global phase transition discontinuities at the depths of 410 km and 660 km are observed (Flanagan and Shearer, 1998), but deep earthquakes occur mainly near the Pacific Rim convergence plate boundaries, not behave as a global distribution.

(3) Shear melting

Bridgman (1936) first found the occurrence of ruptures in the shear test with the confining pressure at 5 GPa and Orowan (1960) believed that these ruptures are caused by creep. On this basis, Griggs and Handin (1960) officially put forward the shear melting hypothesis and believed that after accelerating creep, deformation of the shear band will gradually be confined in a thin layer, where heat production leads to shear melting and subsequent destabilization (deep earthquakes). Although the hypothesis, as an interpretation of the intermediate and deep earthquakes mechanism, can reasonably explain the repeated earthquake and fault plane widths of Bolivia and Fiji earthquakes (Gan et al., 2012), it is still controversial. For instance, Ye et al., (2013) suggested that the 2013 Okhotsk earthquake with a depth of about 609 km may related to shear rupture and little or no melting occurred.

(4) Anticrack-associated faulting

Kirty (1987) observed a new type of high-pressure shear instability in experiments on ordinary polycrystalline ice and polycrystalline tremolite. Green and Burnley (1989) and Green et al., (1990) found by observing microstructures of the experimental samples that when the pressure reached 15 GPa, anticrack began to appear in Olivine-Wadsleyite. As the pressure increases, the fractures connect together and eventually form anticrackassociated faulting. This hypothesis is in agreement with the characteristics of double-couple source and shear component of deep earthquakes and able to establish the relation between phase transition boundary phenomenon and deep earthquake distribution. Also, it is supported by experiments as well as related mechanical mechanism explanation (Gan et al., 2012). Nevertheless, the hypothesis has the following shortcomings. 1) Phase transition is expected only within the metastable region (Geller, 1990; Kirby et al., 1996), but seismological studies have failed to find some evidence for the existence of metastable olivine in slabs (Karato et al., 2001; Mosenfelder et al., 2001; Wiens, 2001). 2) Other scholars (Dupas-Bruzek et al., 1998; Karato et al., 2001) did not observe the production of anticrack at almost identical conditions. 3) The predicted width of the deep seismic fault plane is 10~20 km (Karato et al., 2001), which is significantly smaller than the width of some deep seismic fault plane by actual geophysical observations (Kikuchi and Kanamori, 1994; Wiens et al., 1994; Tibi et al., 1999; Ye et al., 2013).

In summary, the current mainstream hypotheses on the mechanism of shallow, intermediate and deep earthquakes have many controversial issues. Thus, it is necessary to seek a new hypothesis or theory for explaining the earthquake mechanism. Since 1970s, many scholars have gradually recognized that the formation process of major earthquakes is closely related to the stress change and rock deformation in the crust, and have successively proposed various fracture models (Das and Aki, 1977; Brune, 1979; Jones and Molnar, 1979; Wyss et al., 1981; Geng et al., 1986; Mei, 1995). Starting from this understanding, Qin et al., (2010) put forward the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system.

This paper first introduces the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system, then clarifies whether the theory can explain the mechanism of shallow, intermediate and deep earthquakes by typical earthquake cases, and last discusses some of the hot and difficult issues in academia.

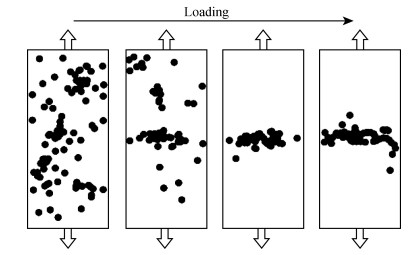

2 INTRODUCTION TO THE BRITTLE FAILURE THEORY OF MULTIPLE LOCKED PATCHES IN A SEISMOGENIC FAULT SYSTEMRock mechanical experiments indicated that the deformation and failure process of rock specimens can be divided into 5 stages (Fig. 4) (Brace et al., 1966; Bieniawski, 1967a, b; Martin and Chandler, 1994). Rock failures result in acoustic emission events (microcracks or microquakes) with the increase of load. During the initial stage of loading, micro-failures behave as a uniform spatial distribution (Fig. 5). When the loading stress reaches to the volume expansion point of a rock specimen, the micro-failures cluster and earthquake swarm events begin to occur. The earthquake swarm events are the only precursor of seismic activity identified by the monitoring technique. Taking a single locked patch as an example, when the loading stress reaches its peak strength point, macroscopic rupture or the mainshock event occurs. A series of failure events within a certain time after the mainshock event is called aftershock. A series of failure events before the peak strength point indicate that the rock specimen is located at the stage of energy accumulation, and a series of failure events at and after the peak strength point indicate that the rock specimen is located at the energy release stage. A series of failure events occurred between its volume expansion and peak strength points are referred to as preshock events, and the preshock events quite close to the peak strength point are referred to as foreshock ones.

|

Fig. 4 Schematic illustration of deformation and failure process of rock (locked patch) under triaxial compression |

|

Fig. 5 Spatial distribution of micro failures during rock deformation (modified after Mogi (1985)) |

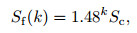

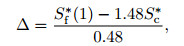

Based on the new understanding of the fault movement pattern and its related seismicity controlled by one or more locked patches on the fault plane, Qin et al., (2010a) originally put forward the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system. Its mechanical expression derived by using the re-normalization group theory and the damage constitutive model is

|

(1) |

where Sc is the CBS (Cumulative Benioff Strain) value corresponding to the volume expansion point of the first locked patch and Sf(k) is the CBS value corresponding to the peak stress point of the k-th locked patch.

Based on Eq.(1) and the real-time monitoring information, the critical CBS value corresponding to the macroscopic rupture of locked patch can be given in advance according to CBS value at it expansion point.

For a defined seismic zone, accurate Benioff strain calculation relies on complete and accurate earthquake catalog in a seismogenic period. Because historic earthquake catalog is often incomplete or contains some errors, the initial strain error must be considered. Hence, Qin et al. (2010a) proposed a formula to calculate the error, i.e.:

|

(2) |

where “∆” represents the strain error, and Sc * and Sf*are the CBS values at the volume expansion point and the peak stress point of the first locked patch, respectively.

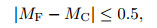

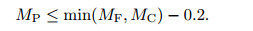

The progressive failures of locked patch result in the occurrence of earthquakes due to fault movement. Hereafter, the significant earthquakes occurred at its volume expansion and peak strength points are referred to as characteristic ones. Assuming that MC and MF are characteristic earthquake magnitude values corresponding to the volume expansion point and the peak stress point of the locked patch, respectively, and MPis the preshock or foreshock event magnitude during this process, their magnitude relation in the condition of unified magnitude scale is generally constrained by

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

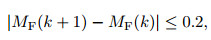

Before mainshock, the magnitude values of adjacent characteristic earthquakes corresponding to the peak stress point of the k-th and k + 1-th locked patch usually follow such relation as

|

(5) |

we found by earthquake cases the equation MF(k + 1)=MF(k) -0.2 is fairly common.

For a defined seismic zone, we suggest from the principle of conservation of energy that the accumulated elastic strain energy prior to mainshock (Ea) should be equivalent to the sum of elastic strain energy released by the mainshock (Em) and aftershocks (Er) in a seismogenic period, i.e.:

|

(6) |

For the seismic zones without the occurrence of mainshock, we can judge whether the characteristic event is a mainshock or not by Eq.(6).

3 CASE ANALYSISWe think that seismic zone can be defined as a faulted or uplifted block constrained by regional large faults. The fault activities (earthquakes) within the block are closely related to each other, while the adjacent blocks affect its loading mode or rate by shearing or compression, but do not alter their respective seismogenic laws of characteristic earthquakes. According to the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system, Qin et al., (2016a, b, c) quantitatively divide into 62 seismic zones in the world (Fig. 6), and the seismogenic processes of characteristic earthquakes can be well explained by the theory. So far, 8 prospective prediction events have been confirmed including 7 preshock and 1 characteristic events (Qin and Xue, 2011; Qin et al., 2012, 2013, 2014a, b, c). Taking 5 typical seismic zones as examples, we will state the applicability of the physical mechanism of shallow, intermediate and deep characteristic earthquakes explained by the theory.

|

Fig. 6 Division map of main seismic zones in the world (Version 2.0) (Qin et al., 2016d) |

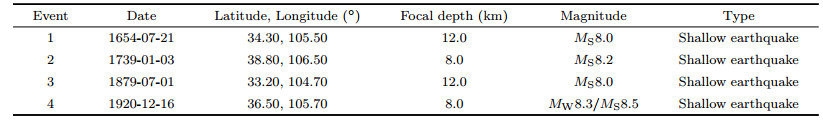

The Haiyuan seismic zone (No.23 in Fig. 6) is a shallow one and has experienced 4 earthquake events with M≥8.0 (Table 1).

|

|

Table 1 The earthquake events with M≥8.0 in the Haiyuan seismic zone |

Figure 7 shows the mechanical correlation among characteristic earthquake events occurred in the current seismogenic period of this seismic zone after error correction (Qin et al., 2016c). Using the CBS value prior to the 1561-08-04 east of Zhongyu, Ningxia MS7.5 earthquake we can more accurately and continuously forecast the critical CBS values of the 1654-07-21 south of Tianshui, Gansu MS8.0, 1739-01-03 Pingluo, Ningxia MS8.2 and 1920-12-16 Haiyuan, Ningxia MW8.3 earthquakes. Applying the Eq.(6), we deduce that the forth locked patch exists in this seismic zone in the current period. When the damage to it accumulates to the peak stress point, a large characteristic earthquake event will occur.

|

Fig. 7 Temporal distribution of CBS in the period from B.C. February 193 to 21 November 2015 for the Haiyuan seismic zone The 1920 Haiyuan earthquake is considered as MW8.3 (Qin et al., 2016c). The earthquake events with MS≥5.5 are selected for data analysis. The error correction is also considered. |

The earthquake cases indicate that the seismogenic processes of characteristic earthquakes can be well explained by the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system and the physical mechanism of major shallow earthquake is attributed to the brittle failure of locked patches.

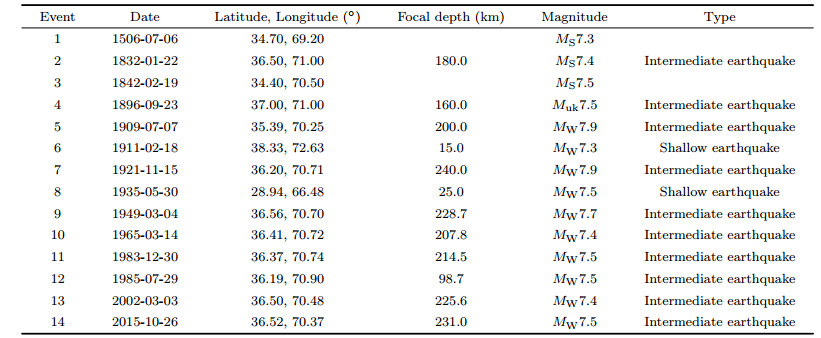

3.2 Seismic Zone of Intermediate EarthquakesThe Hindu Kush seismic zone (No.58 in Fig. 6), located near the boundary of Indian and Eurasian plates, is an intermediate events-prone one. It has experienced 14 earthquake events with M≥7.3, including 10 intermediate earthquakes (Table 2).

|

|

Table 2 the earthquake events with M≥7.3 in the Hindu Kush seismic zone |

Figure 8 shows the mechanical correlation among characteristic earthquake events occurred in the current seismogenic period of this seismic zone after error correction (Qin et al., 2016c). Using the CBS value prior to the 1909-07-07 Badakhshan, Afghanistan MW7.9 earthquake we can more accurately and continuously forecast the critical CBS values of 1921-11-15 Badakhshan MW7.9, 1949-03-04 Fayzabad MW7.7 and Badakhshan 1983-12-30-1985-07-29 MW7.5 double earthquakes. Applying the Eq.(6), we deduce that the forth locked patch exists in this seismic zone in the current period. When the damage to it accumulates to the peak stress point, a large characteristic earthquake event will occur.

|

Fig. 8 Temporal distribution of CBS in the period from 6 July 1505 to 24 February 2016 for the Hindu Kush seismic zone The earthquake events with ML≥6.5 are selected for data analysis. The error correction is also considered. |

The earthquake cases indicate that the seismogenic processes of characteristic earthquakes can be well explained by the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system and the physical mechanism of major intermediate earthquake is attributed to the brittle failure of locked patches.

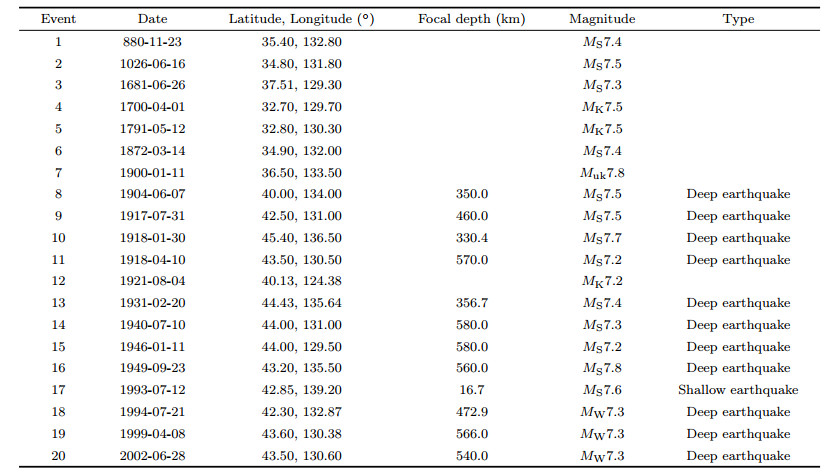

3.3 Seismic Zone of Deep EarthquakesThe Hunchun seismic zone (No.31 in Fig. 6), located near the boundary of Eurasian and Okhotsk plates, is a deep events-prone one. It has experienced 20 earthquake events with M≥7.2, including 11 deep earthquakes (Table 3).

|

|

Table 3 The earthquake events with M≥7.2 in the Hunchun seismic zone |

Figure 9 shows the mechanical correlation among characteristic earthquake events occurred in the current seismogenic period of this seismic zone after error correction (Qin et al., 2016b). Using the CBS value prior to the 1900-01-11 Japan Sea Muk7.8 earthquake we can more accurately and continuously forecast the critical CBS values of both 1918-01-30 Russia’s Primorskiy Kray MS7.7 and 1949-09-23 Japan Sea MS7.8 earthquake. Applying the Eq.(6), we deduce that the third locked patch exists in this seismic zone in the current period. When the damage to it accumulates to the peak stress point, a large characteristic earthquake event will occur.

|

Fig. 9 Temporal distribution of CBS in the period from February 19 to 3 January 2016 for the Hunchun seismic zone The earthquake events with MS≥6.5 are selected for data analysis. The error correction is also considered. |

The earthquake cases indicate that the seismogenic processes of characteristic earthquakes can be well explained by the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system and the physical mechanism of major deep earthquakes is attributed to the brittle failure of locked patches.

3.4 Mixed-Type Seismic ZoneThe Jakarta and Hokkaido seismic zones where shallow, intermediate and deep events all occurred, are referred to as the mixed-type ones.

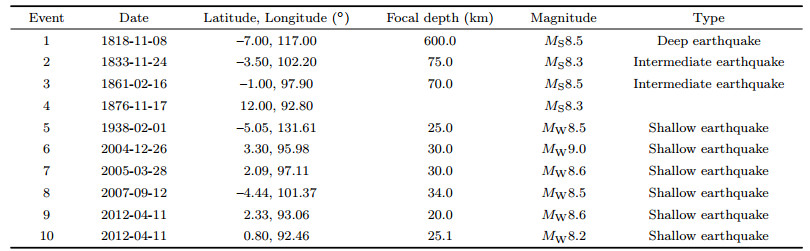

3.4.1 Jakarta seismic zoneThe seismic zone (No.34 in Fig. 6), located near the boundary of Australia, India, Burma and Eurasia plates, has experienced 10 earthquake events with M≥8.2 (Table 4). By the end of 24 February 2016, 55 earthquake events with M≥7.5, including 47 shallow, 5 intermediate and 3 deep events, occurred within this zone.

|

|

Table 4 The earthquake events with M≥8.2 in the Jakarta seismic zone |

Figure 10 shows the mechanical correlation among characteristic earthquake events occurred in the current seismogenic period of this seismic zone after error correction (Qin et al., 2016a). Using the CBS value prior to the 1818-11-08 Indonesia Bali sea MS8.5 earthquake we can more accurately and continuously forecast the critical CBS values of the 1861-02-16 Lagundi MS 8.5, 1938-02-01 Banda Sea MW8.5 and 2004-12-26 Sumatra’s western coast MW9.0 earthquake. Applying the Eq.(6), we deduce that the forth locked patch exists in this seismic zone in the current period. When the damage to it accumulates to the peak stress point, a larger characteristic earthquake event will occur.

|

Fig. 10 Temporal distribution of CBS in the period from 1 August 1629 to 24 February 2016 for the Jakarta seismic zone (modified after Qin et al. (2016a)) The earthquake events with ML≥7.0 are selected for data analysis. The error correction is also considered. |

The seismic zone (No.38 in Fig. 6), located near the boundary of Okhotsk, Eurasia, North American, Pacific and Philippines plates, has experienced 19 earthquake events with M≥8.3 (Table 5). By the end of 24 February 2016, 83 earthquake events with M≥7.5, including 75 shallow, 3 intermediate and 5 deep events, occurred within this zone.

|

|

Table 5 The earthquake events with M≥8.3 in the Hokkaido seismic zone |

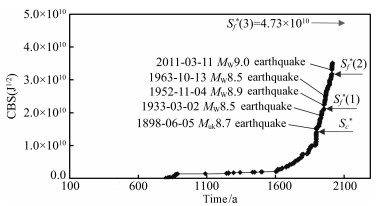

Figure 11 shows the mechanical correlation among characteristic earthquake events occurred in the current seismogenic period of this seismic zone after error correction (Qin et al., 2016a). Using the CBS value prior to the 1898-06-05 Japan Trench Muk8.7 earthquake we can more accurately and continuously forecast the critical CBS values of both 1952-11-04 Kamchatka near east coast MS8.5 and 2011-03-11 Miyagi near east coast, Japan MW 9.0 earthquake. Applying the Eq.(6), we deduce that the third locked patch exists in this seismic zone in the current period. When the damage to it accumulates to the peak stress point, a larger characteristic earthquake event will occur.

|

Fig. 11 Temporal distribution of CBS in the period from 15 February 144 to 24 February 2016 for the Hokkaido seismic zone The earthquake events with MW≥7.0 are selected for data analysis. The error correction is also considered. |

The earthquake cases of these two seismic zones indicate that the seismogenic processes of characteristic earthquakes can be well explained by the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system.

4 THE ENVIRONMENT CONDITIONS OF SOURCE BODY OF DEEP EARTHQUAKESIt is generally believed (Kirby et al., 1991; Frohlich, 1994) that at higher pressures and temperatures shear stress should deform rocks by ductile flow. Thus, the ordinary brittle failures similar to shallow earthquakes are not expected. Is that true?

Wiens and Gilbert (1996) recognized that deep earthquakes are affected and controlled by the thermal structure of tectonic plates, and are highly sensitive to the temperature of the plate (Stein, 1995; Wiens, 2001). The relatively cooler subducting plate subducts into the upper mantle. The research results (Thompson, 1992) show that the temperature of mantle discontinuities at the depths of 410 km and 660 km is close to 1450 ℃ and 1600 ℃, respectively. Deep earthquakes often occur in the low-temperature oceanic subduction zone, because the descending lithosphere is thick and a poor thermal conductor; it can remain anomalously cold for millions of years during active subduction; it may be as much as 1000 ℃ cooler than the surrounding mantle (Kirby et al., 1991).

Deep earthquakes occur mainly within the cold subduction plate, rather than its boundaries (McGuire et al., 1997; Wiens, 2001). Emmerson and Da (2007) recognized that the mechanical behavior of the oceanic and continental uppermost mantle depends on temperature alone. In spite of the high temperature of mantle, the inner zone of plates keeps relatively low temperature. McKenzie et al. (2005) believed that the temperature of the zones where deep earthquakes occurred is less than 600 ℃. Kirby et al., (1996) also considered that the deep events are restricted to downgoing slabs where the temperature is 500 ℃~700 ℃. The laboratory high-temperature and high-pressure experiments show that the serpentine can still undergo brittle failures at up to 40 GPa (Zhang, 2003), which is higher than 23 GPa of the pressure on the top of the lower mantle (Ishii et al., 2011). This demonstrates again that temperature is the key to the occurrence of brittle failures of rock. Moreover, the high-temperature and high-pressure tests show that brittle failures occur in granite when temperature is less than 800 ℃ (Zhai, 2013), in serpentine when temperature is less than 900 ℃ (Dobson et al., 2002) and in garnet when temperature is less than 1000 ℃ (Voegelé et al., 1998). Furthermore, mineral dehydration could reduce the effective stress of the original fault, which is conducive to the occurrence of brittle failure (Stein, 1995).

A great deal of research results demonstrate that the fracture characteristics of deep earthquakes are similar to that of the shallow events (Kirby et al., 1991; Green and Houston, 1995; Wiens, 2001), including radiation pattern, magnitude distribution, focus-time function, rupture velocity and stress drop (Gan et al., 2012). This means that the mechanism of deep earthquakes, just like the shallow ones, can be regarded as the shear failures of rock due to fault movement or plate subducting.

According to present focal mechanism solutions, deep earthquakes have shear fracture characteristics. For instance, Ye et al., (2013) suggests that a MW8.3 earthquake of 24 May 2013 ruptured a 180 km-long fault within the subducting Pacific plate about 609 km below the Sea of Okhotsk and the peak slip is about 10 m; Seismic radiation from deep earthquakes indicates that they likely involve shear faulting basically indistinguishable from shallow earthquakes despite the extreme pressure conditions. Compared with the shallow events, both this great event and 1994 Bolivia MW7.6 deep earthquake have similar faulting geometries with very shallow-dipping normal fault mechanisms and only minor deviations from shear double-couple solutions. A series of aftershocks occurred after the 9 March 1994 MW7.6 deep earthquake (depth, 564 km). Analysis of the data from 8 nearby temporary broadband seismic stations showed that the rupture velocity, stress drop, number, power-law decay with time of these aftershocks was similar to that of aftershocks after typical shallow earthquakes (Wiens et al., 1994). Jiao et al., (2000) statistically analyzed the deep earthquakes in Tonga from February 1976 to March 1999 and pointed out that the existence of highly non-uniform stress fields or the existing faults in the subduction zone could lead to occurrence of some deep earthquakes.

The above analysis shows that the source body of deep earthquakes has the appropriate environment conditions leading to brittle failures and the physical mechanism of deep earthquakes may be similar to the shallow ones.

5 THE PHYSICAL MECHANISM OF MAJOR EARTHQUAKESThe brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system can uniformly describe the seismogenic law of shallow, intermediate and deep earthquakes by the above-mentioned earthquake cases. Moreover, it is deduced that the elastic rebound and stick-slip hypotheses, in fact, imply the hypothesis that lock patches exist in the fault or subduction zone.

For the elastic rebound hypothesis, if the fault zone is only composed of soft materials, that is, the strength of the two walls of a fault (quasi-rigid-body) is much higher than that of the fault-plane medium, they must behave as a steady-state creep along the fault, and can hardly realize large elastic deformation. When the fault zone contains a high strength medium (locked patch), deformation of the rock mass is blocked, implying that large elastic deformation can be accumulated. This means that the elastic rebound hypothesis actually implies the assumption that the locked patch exists in some parts of the fault zone.

For the stick-slip hypothesis, only when the fault movement is blocked, i.e., there is a high-strength obstacle or rock bridge in some parts of the fault zone, stick-slip behavior can appear. When it is loaded to its peak strength point, the two sides of the fault will suddenly slide. When there are multiple high-strength segments of the fault, alternating behaviors of bonding and sliding could occur along the fault plane. This means that the stick-slip hypothesis also implies the existence of locked patches in some parts of the fault zone. In this way, the spring-block model described above can be slightly modified to provide a reasonable explanation of the major earthquake mechanism. If a fault contains a locked patch, fault movement will lead to accumulation of strain energy. Small ruptures result in small earthquakes, while large ruptures lead to large earthquakes. However, as long as the locked patch is not fully fractured, sliding is still relatively small even if a large earthquake occurs. At this stage, there occurs bonding behavior. Only when the locked patch is loaded to its peak strength point, a sudden sliding will occur along the fault. Furthermore, if there are multiple locked patches, persistent seismic activity can occur.

For the shear melting hypothesis, if the sheared band contains a locked patch, the deformation localization after initiation of accelerated creep is regarded as rupture cluster. This mechanism can also be explained rationally according to the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system.

The above analysis shows that the elastic rebound, stick-slip and shear melting hypotheses can be unified to the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system, demonstrating that the theory is universal and can reasonably explain the following academia-concerned hot and difficult issues.

5.1 Why is Seismic Stress Drop Much Less Than That of Rock Failure in the Laboratory Test?When a major earthquake occurs, the observed stress drop is about 1~10 MPa (Kanamori and Anderson, 1975; Chen, 2010), mainly in the range of 2~6 MPa (Zang, 1984). However, the results of high-temperature and high-pressure experiments show (Brace and Byerlee, 1966; Ismail and Murrell, 1990) that the rock failure stress drop can reach 100~700 MPa, much higher than the earthquake stress drop. For this problem, other seismic mechanism hypotheses cannot give a satisfactory explanation. Based on the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system, it is considered that when the mainshock occurs in a seismic zone, that is, when the last locked patch reaches its macroscopic fracture point corresponding to its peak strength in the current seismogenic period, the stress can be fully released because there is no restraint by the next locked patch. Therefore, the predicted stress drop should be consistent with that observed in laboratory tests. For the characteristic earthquake event before the mainshock, the locked patch will be restrained by the next locked patch, thus, the stress drop will not be too large. For a significant preshock between the characteristic events, because it is an intermediate process event caused by local rupture of locked patch, the stress drop should be small.

Our analysis on 62 seismic zones in the world shows (Qin et al., 2016a, b, c) that the mainshock events in these seismic zones have not yet occurred. Thus, it is concluded that the stress drop of some earthquakes estimated in the past should be much lower than that of laboratory experiments.

5.2 Heat Flow ParadoxThe question that “is the seismic fault strength high or low?” is a scientific issue that has puzzled seismologists for decades (Miller, 2002; Chen, 2010). If the fault strength is low, it is impossible to accumulate high enough energy to generate major or great earthquakes. If the fault strength is high, the fault sliding friction will produce obvious heat flow paradox (Mckenzie and Brune, 1972). However, this paradox has not been observed in the San Andreas fault (Brune et al., 1969; Henyey and Wasserburg, 1971; Lachenbruch and Sass, 1988; Scholz, 2002), indicating that the maximum shear stress withstood by the San Andreas fault is not high and hence the fault strength is weak. The above paradox is referred to as heat flow paradox, also known as fault strength paradox or San Andreas paradox.

We believe that there are one or more locked patches in a seismogenic fault, i.e., some parts of the fault are with high strength but the other parts are with relatively low strength. The locked patches with high strength are subjected to concentrated stress and are high-energy carriers while the other part of fault with low strength is responsible for stress transmission or adjustment. Once a locked patch undergoes macro-rapture, the stress is hifted down to the next locked patch, causing this locked patch to undergo stress concentration, and so on. If the heat flow paradox does reflect higher stress condition, one can observe the obvious heat flow paradox at the site where a locked patch undergoes large raptures in a short period. However, after the occurrence of a major earthquake, the heat generated by friction is unable to be directly measured, but only by the measurement of shallow crustal geothermy (Yan, 2011). Thus, the heat flow measured near the earth’s surface may hardly reflect the actual situation of the deep earth. This provides a rational explanation to the San Andreas paradox.

5.3 Self-Organized Criticality (SOC)The SOC concept was first proposed by Bak et al. (1987). For a system composed of many basic units with continuous energy supply, it will spontaneously evolve to a critical state when the units interact in nonlinear way. At present, the international debates on earthquake prediction are largely related to the SOC model of earthquakes. Geller et al. (1997) believed that earth is in a SOC state where any small earthquakes are likely to cascade into a major earthquake, and concluded that the earthquake could not be predicted. The relationship between Self-Organization and Criticality can be answered based on the brittle failure theory of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system. The mechanics experiments show that the failure process of rock specimens is stable and does not appear to be Self-Organized before being loaded into the volume expansion point. When the rock is loaded into its volume expansion point, not only the existing crack propagates but also new cracks are produced and micro-ruptures begin to cluster. At this time, even if the loading is stopped, the equilibrium state cannot be maintained, implying that the system will spontaneously evolve toward the macroscopic rupture point of the rock-the critical point. Thus, the volume expansion point is the starting point of Self-Organization behavior. When the damage accumulates to the peak strength point, the macroscopic rupture occurs, and the rock is suddenly unstable. In other words, the Self-Organization process must occur prior to instability, i.e., Self-Organization is the cause while the critical instability is the result. It is not a transient process from the Self-Organization to the critical failure. The seismogenesis of a major earthquake is a long-term process. Our analysis on the seismogenic process of characteristic events occurred in 62 seismic zones suggests (Qin et al., 2016a, b, c) that this process can take anywhere from a few decades to hundreds or even thousands of years.

6 CONCLUSION(1) The mainstream hypotheses on the earthquake mechanism are reviewed in this paper. We emphasize that both the elastic rebound and stick-slip hypotheses contain the same implicit assumption that there exist locked patches in seismogenic faults, and that the source body of deep-focus earthquakes is with appropriate environment conditions leading to brittle failures.

(2) The earthquake cases indicate that the seismogenic processes of characteristic earthquakes in each seismic zone can be well explained by the theory and the shallow, intermediate and deep earthquakes are all caused by the brittle failures of locked patches.

(3) Some controversial issues, such as seismic stress drop much less than that of rock failure in the laboratory test, heat flow paradox and SOC, are discussed and can be reasonably explained by the theory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41572311, 41302233).

| [] | An M J, Shi Y L. 2007. Three-dimensional thermal structure of the Chinese continental crust and upper mantle. Science in China (Series D):Earth Science (in Chinese) , 37 (6) : 736-745. |

| [] | Bak P, Tang C, Wiesenfeld K. 1987. Self-organized criticality:An explanation of the 1/f noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. , 59 (4) : 381-384. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.381 |

| [] | Brace W F, Byerlee J D. 1966. Stick-slip as a mechanism for earthquakes. Science , 153 (3739) : 990-992. DOI:10.1126/science.153.3739.990 |

| [] | Brace W F, Byerlee J D. 1970. California earthquakes:why only shallow focus?. Science , 168 (3939) : 1573-1575. DOI:10.1126/science.168.3939.1573 |

| [] | Brady B T. 1974. Theory of earthquake. Pure Appl. Geophys. , 112 (4) : 701-725. DOI:10.1007/BF00876809 |

| [] | Brady B T. 1975. Theory of earthquakes. Part Ⅲ:Inclusion collapse theory of deep earthquakes. Pure Appl. Geophys. , 114 (1) : 119-139. |

| [] | Bridgman P W. 1936. Shearing phenomena at high pressure of possible importance for geology. J. Geol. , 44 (6) : 653-669. DOI:10.1086/624468 |

| [] | Bridgman P W. 1945. Polymorphic transitions and geological phenomena. Am. J. Sci. , 43A : 90-97. |

| [] | Brune J N. 1979. Implications of earthquake triggering and rupture propagation for earthquake prediction based on premonitory phenomena. J. Geophys. Res. , 84 (B5) : 2195-2198. DOI:10.1029/JB084iB05p02195 |

| [] | Brune J N, Henyey T L, Roy R F. 1969. Heat flow, stress, and rate of slip along the San Andreas Fault, California. J. Geophys. Res. , 74 (15) : 3821-3827. DOI:10.1029/JB074i015p03821 |

| [] | Byerlee J. 1978. Friction of rocks. Pure Appl. Geophys. , 116 (4) : 615-626. |

| [] | Byerlee J D. 1970. The mechanics of stick-slip. Tectonophysics , 9 (5) : 475-486. DOI:10.1016/0040-1951(70)90059-4 |

| [] | Chen Y T. 2007. Earthquake prediction:progress, difficulties and prospects. Seismological and Geomagnetic Observation and Research (in Chinese) , 28 (2) : 1-24. |

| [] | Chen Y T. 2010. Heat flow paradox. 10000 Selected Problems in Sciences·Earth Science (in Chinese)[M]. Beijing: Science Press: 546 -548. |

| [] | Chernak L J, Hirth G. 2010. Deformation of antigorite serpentinite at high temperature and pressure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. , 296 : 23-33. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2010.04.035 |

| [] | Collier J D, Helffrich G R, Wood B J. 2001. Seismic discontinuities and subduction zones. Phys. Earth Planet. In. , 127 : 35-49. DOI:10.1016/S0031-9201(01)00220-5 |

| [] | Das S, Aki K. 1977. Fault plane with barriers:A versatile earthquake model. J. Geophys. Res. , 82 (36) : 5658-5670. DOI:10.1029/JB082i036p05658 |

| [] | Dobson D P, Meredith P G, Boon S A. 2002. Simulation of subduction zone seismicity by dehydration of serpentine. Science , 298 : 1407-1410. DOI:10.1126/science.1075390 |

| [] | Dupas-Bruzek C, Sharp T G, Rubie D C, et al. 1998. Mechanisms of transformation and deformation in Mg1.8Fe0.2SiO4, olivine and wadsleyite under non-hydrostatic stress. Phys. Earth Planet. In. , 108 : 33-48. DOI:10.1016/S0031-9201(98)00086-7 |

| [] | Dziewonski A M, Gilbert F. 1974. Temporal Variation of the Seismic Moment Tensor and the Evidence of Precursive Compression for Two Deep Earthquakes. Nature , 252 : 28-29. DOI:10.1038/252028a0 |

| [] | Emmerson B, Dan M K. 2007. Thermal structure and seismicity of subducting lithosphere. Phys. Earth Planet. In. , 163 : 191-208. DOI:10.1016/j.pepi.2007.05.007 |

| [] | Estabrook C H, Kind R. 1996. The nature of the 660-kilometer upper-mantle seismic discontinuity from precursors to the PP phase. Science , 274 (5290) : 1179-1182. DOI:10.1126/science.274.5290.1179 |

| [] | Flanagan M P, Shearer P M. 1998. Global mapping of topography on transition zone velocity discontinuities by stacking SS precursors. J. Geophys. Res. , 103 (B2) : 2673-2692. DOI:10.1029/97JB03212 |

| [] | Frohlich C. 1994. A break in the deep. Nature , 368 : 100-101. DOI:10.1038/368100a0 |

| [] | Gan W, Jin Z M, Wu Y, et al. 2012. A review of the mechanism of deep earthquakes:current situation and problems. Earth Science Frontiers (in Chinese) , 19 (4) : 15-29. |

| [] | Geller R J. 1990. Metastable phases confirmed. Nature , 347 : 620-621. DOI:10.1038/347620a0 |

| [] | Geller R J, Jackson D D, Kagan Y Y, et al. 1997. Earthquakes cannot be predicted. Science , 275 : 1616-1617. DOI:10.1126/science.275.5306.1616 |

| [] | Geng N G, Li J H, Hao J S, et al. 1986. Precursory deformation and stress drop in rupture experiments of brittle rocks. Earthquake (in Chinese) , 1 : 9-12. |

| [] | Green H W Ⅱ, Chen W P, Brudzinski M R. 2010. Seismic evidence of negligible water carried below 400 km depth in subducting lithosphere. Nature , 467 : 828-831. DOI:10.1038/nature09401 |

| [] | Green H W Ⅱ, Houston H. 1995. The mechanics of deep earthquakes. Annu. Rev. Earth Pl. Sci. , 23 : 169-214. DOI:10.1146/annurev.ea.23.050195.001125 |

| [] | Green H W, Young T E, Walker D, et al. 1990. Anticrack-associated faulting at very high pressure in natural olivine. Nature , 348 : 720-722. DOI:10.1038/348720a0 |

| [] | Griggs D T, Baker D W. 1969. The Origin of Deep-Focus Earthquakes in Properties of Matter Under Unusual Conditions. John Wiley, New York, 23-42. |

| [] | Griggs D T, Handin J. 1960. Observations on fracture and a hypothesis of earthquake. In:Rock deformation. Geol. Soc. Am. Mem., 79:347-364. |

| [] | Henyey T L, Wasserburg G J. 1971. Heat flow near major strike-slip faults in California. J. Geophys. Res. , 76 (32) : 7924-7946. DOI:10.1029/JB076i032p07924 |

| [] | Houston H. 1993. The non-double-couple component of deep earthquakes and the width of the seismogenic zone. Geophys. Res. Lett. , 20 (16) : 1687-1690. DOI:10.1029/93GL01301 |

| [] | Ishii T, Kojitani H, Akaogi M. 2011. Post-spinel transitions in pyrolite and Mg2SiO4 and akimotoite-perovskite transition in MgSiO3:Precise comparison by high-pressure high-temperature experiments with multi-sample cell technique. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. , 309 : 185-197. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2011.06.023 |

| [] | Ismail I A H, Murrell S A F. 1990. The effect of confining pressure on stress-drop in compressive rock fracture. Tectonophysics , 175 (1-3) : 237-248. DOI:10.1016/0040-1951(90)90140-4 |

| [] | Jiang Z S, Wu Y Q. 2012. Crustal Deformation and Location Forecast of Strong Earthquakes:Understandings and Questions. Earthquake (in Chinese) , 32 (2) : 8-21. |

| [] | Jiao W, Silver P G, Fei Y, et al. 2000. Do intermediate-and deep-focus earthquakes occur on preexisting weak zones? An examination of the Tonga subduction zone. J. Geophys. Res. , 105 (B12) : 28125-28138. DOI:10.1029/2000JB900314 |

| [] | Jones L M, Molnar P. 1979. Some characteristics of foreshocks and their possible relationship to earthquake prediction and premonitory slip on faults[M]. : 3596 -3608. |

| [] | Kanamori H, Anderson D L. 1975. Theoretical basis of some empirical relations in seismology. B. Seismol. Soc. Am. , 65 (5) : 1073-1095. |

| [] | Kanamori H, Brodsky E E. 2004. The physics of earthquakes. Rep. Prog. Phys. , 67 : 1429-1496. DOI:10.1088/0034-4885/67/8/R03 |

| [] | Karato S, Riedel M R, Yuen D A. 2001. Rheological structure and deformation of subducted slabs in the mantle transition zone:implications for mantle circulation and deep earthquakes. Phys. Earth Planet. In. , 127 : 83-108. DOI:10.1016/S0031-9201(01)00223-0 |

| [] | Kawakatsu H. 1991. Insignificant isotropic component in the moment tensor of deep earthquakes. Nature , 351 : 50-53. DOI:10.1038/351050a0 |

| [] | Kikuchi M, Kanamori H. 1994. The mechanism of the deep Bolivia earthquake of June 9, 1994. Geophys. Res. Lett. , 21 (22) : 2341-2344. DOI:10.1029/94GL02483 |

| [] | Kirby S H. 1987. Localized polymorphic phase transformations in high-pressure faults and applications to the physical mechanism of deep earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. , 92 (B13) : 13789-13800. DOI:10.1029/JB092iB13p13789 |

| [] | Kirby S H, Durham W B, Stern L A. 1991. Mantle phase change and deep-earthquake faulting in subducting lithosphere. Science , 252 : 216-225. DOI:10.1126/science.252.5003.216 |

| [] | Kirby S H, Stein S, Okal E A, et al. 1996. Metastable mantle phase transformations and deep earthquakes in subducting oceanic lithosphere. Rev. Geophys. , 34 (2) : 261-306. DOI:10.1029/96RG01050 |

| [] | Lachenbruch A H, Sass J H. 1988. The stress heat-flow paradox and thermal results from Cajon Pass. Geophys. Res. Lett. , 15 (9) : 981-984. DOI:10.1029/GL015i009p00981 |

| [] | Lei Q Y, Chai C Z, Du P, et al. 2015. The seismogenic structure of the M8.0 Pingluo earthquake in 1739. Seismology and Geology (in Chinese) , 37 (2) : 413-429. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0253-4967.2015.02.006 |

| [] | Liu G, Wang Q, Qiao X J, et al. 2015. The 25 April 2015 Nepal MS8.1 earthquake slip distribution from joint inversion of teleseismic, static and high-rate GPS data. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 58 (11) : 4287-4297. DOI:10.6038/cjg20151133 |

| [] | Liu L Q. 2014. Elastic rebound model:From the classic to the future. Seismology and Geology (in Chinese) , 36 (3) : 825-832. |

| [] | Lu K Q, Cao Z X, Hou M Y, et al. 2014. On the mechanism of earthquake. Acta Physica Sinica (in Chinese) , 63 (21) : 444-466. |

| [] | McGuire J J, Wiens D A, Shore P J, et al. 1997. The March 9, 1994 (MW7.6), deep Tonga earthquake:Rupture outside the seismically active slab. J. Geophys. Res. , 102 (B7) : 15163-15182. DOI:10.1029/96JB03185 |

| [] | McKenzie D, Brune J N. 1972. Melting on fault planes during large earthquakes. Geophys. J. R. astr. Soc. , 29 : 65-78. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1972.tb06152.x |

| [] | McKenzie D, Jackson J, Priestley K. 2005. Thermal structure of oceanic and continental lithosphere. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. , 233 (3) : 337-349. |

| [] | Mei S R. 1995. On the physical model of earthquake precursor fields and the mechanism of precursors' time and space distribution (Ⅰ)-origin and evidences of the strong body earthquake-generating model. Acta Seismologica Sinica (in Chinese) , 8 (3) : 337-349. DOI:10.1007/BF02650562 |

| [] | Miller S A. 2002. Earthquake scaling and the strength of seismogenic faults. Geophys. Res. Lett. , 29 (10) : 27-1-27-4. DOI:10.1029/2001GL014181 |

| [] | Mishra O P, Zhao D. 2004. Seismic evidence for dehydration embrittlement of the subducting Pacific slab. Geophys. Res. Lett. , 31 (9) : 165-198. |

| [] | Mogi K. 1985. Earthquake Prediction[M]. Tokyo: Academic Press . |

| [] | Mosenfelder J L, Marton F C, Ross C R, et al. 2001. Experimental constraints on the depth of olivine metastability in subducting lithosphere. Phys. Earth Planet. In. , 127 : 165-180. DOI:10.1016/S0031-9201(01)00226-6 |

| [] | Ohnaka M. 2013. The Physics of Rock Failure and Earthquakes. Cambridge Unive. Press. |

| [] | Okal E A. 1996. Radial modes from the great 1994 Bolivian earthquakes:no evidence for an isotropic component to the source. Geophys. Res. Lett. , 23 (5) : 431-434. DOI:10.1029/96GL00375 |

| [] | Okazaki K, Hirth G. 2016. Dehydration of lawsonite could directly trigger earthquakes in subducting oceanic crust. Nature , 530 : 81-84. DOI:10.1038/nature16501 |

| [] | Orowan E. 1960. Mechanism of seismic faulting in rock deformation:A symposium. Geol. Soc. Am. Mem. , 79 : 323-346. DOI:10.1130/MEM79 |

| [] | Qin S Q, Li P, Xue L, et al. 2014a. The definition of seismogenic period of strong earthquakes for some seismic zones in southwest China. Progress in Geophys. (in Chinese) , 29 (4) : 1526-1540. DOI:10.6038/pg20140407 |

| [] | Qin S Q, Li P, Yang B C, et al. 2016a. The identification of mainshock events for main seismic zones in seismic belts of the Circum-Pacific, ocean ridge and continental rift. Progress in Geophys. (in Chinese) , 30 (2) : 574-588. DOI:10.6038/pg20160209 |

| [] | Qin S Q, Xu X W, Hu P, et al. 2010. Brittle failure mechanism of multiple locked patches in a seismogenic fault system and exploration on a new way for earthquake prediction. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 53 (4) : 1001-1014. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0001-5733.2010.04.025 |

| [] | Qin S Q, Xue L. 2011. A summary of prediction for the Yingjiang MS5.8 earthquake in Yunnan and the Burma MS7.2 earthquake as well as the analysis on the earthquake situation after the earthquake. Progress in Geophys. (in Chinese) , 26 (2) : 462-468. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1004-2903.2011.02.010 |

| [] | Qin S Q, Xue L, Li G L, et al. 2012. The verification of prospective prediction for the Zhaotong earthquakes on 7 September 2012. Progress in Geophys. (in Chinese) , 27 (5) : 1837-1840. DOI:10.6038/j.issn.1004-2903.2012.05.001 |

| [] | Qin S Q, Xue L, Li G L, et al. 2013. The verification of prospective prediction for the Minxian-Zhangxian MS6.6 earthquake in Gansu province and an analysis on the future earthquake situation. Progress in Geophys. (in Chinese) , 28 (4) : 1860-1868. DOI:10.6038/pg20130427 |

| [] | Qin S Q, Xue L, Li G L, et al. 2014b. The verification of prospective prediction for the Lushan MS7.0 earthquake on 20 April 2013 and an analysis on future earthquake situation. Progress in Geophys. (in Chinese) , 29 (1) : 141-147. DOI:10.6038/pg20140118 |

| [] | Qin S Q, Xue L, Li P, et al. 2014c. A review of prospective prediction for the Jinggu MS6.6 earthquake in Yunnan province and an analysis on future earthquake situation. Progress in Geophys. (in Chinese) , 29 (5) : 2479-2482. DOI:10.6038/pg20140574 |

| [] | Qin S Q, Xue L, Li P, et al. 2014d. A review of prospective prediction for the Yutian 7.3 earthquake in Xinjiang province and an analysis on future earthquake situation. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 57 (2) : 679-684. DOI:10.6038/cjg20140231 |

| [] | Qin S Q, Yang B C, Wu X W, et al. 2016b. The identification of mainshock events for some seismic zones in mainland China (Ⅱ). Progress in Geophys. (in Chinese) , 31 (1) : 115-142. DOI:10.6038/pg20160114 |

| [] | Qin S Q, Yang B C, Xue L, et al. 2016c. The identification of mainshock events for main seismic zones in the Eurasian seismic belt. Progress in Geophys. (in Chinese) , 31 (2) : 559-573. DOI:10.6038/pg20160208 |

| [] | Qin S Q, Yang B C, Xue L, et al. 2016d. Revision method of earthquake magnitude. Progress in Geophys. (in Chinese) , 31 (3) : 965-972. DOI:10.6038/pg20160305 |

| [] | Raleigh C B, Paterson M S. 1965. Experimental deformation of serpentinite and its tectonic implications. J. Geophys. Res. , 70 (16) : 3965-3985. DOI:10.1029/JZ070i016p03965 |

| [] | Reid H F. 1910. The California earthquake of April 18, 1906, the mechanics of the earthquake.//The State Earthquake Investigation Committee Report, Carnegie Institution of Washington. |

| [] | Scholz C H. 1998. Earthquakes and friction laws. Nature , 391 : 37-42. DOI:10.1038/34097 |

| [] | Scholz C H. 2002. The debate on the strength of crustal fault zones.//The Mechanics of Earthquakes and Faulting, Cambridge Unive. Press, New York, 158-167. |

| [] | Sibson R H. 1977. Fault rocks and fault mechanisms. J. Geol. Soc. London , 133 (3) : 191-213. DOI:10.1144/gsjgs.133.3.0191 |

| [] | Sibson R H. 1982. Fault zone models, heat flow, and the depth distribution of earthquakes in the continental crust of the United States. B. Seismol. Soc. Am. , 72 (1) : 151-163. |

| [] | Silver P G, Beck S L, Wallace T C, et al. 1995. Rupture characteristics of the deep Bolivian earthquake of 9 June 1994 and the mechanism of deep focus earthquakes. Science , 268 : 69-73. DOI:10.1126/science.268.5207.69 |

| [] | Stein S. 1995. Deep earthquakes:a fault too big?. Science , 268 : 49-50. DOI:10.1126/science.268.5207.49 |

| [] | Thompson A B. 1992. Water in the earth's upper mantle. Nature , 358 : 295-302. DOI:10.1038/358295a0 |

| [] | Tibi R, Estabrook C H, Bock G. 1999. The 1996 June 17 Flores Sea and 1994 March 9 Fiji-Tonga earthquakes:source processes and deep earthquake mechanisms. Geophys. J. Int. , 138 (3) : 625-642. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-246x.1999.00879.x |

| [] | Toshihiro I, Toru M, Akira H. 2003. Repeating earthquakes and interplate aseismic slip in the northeastern Japan subduction zone. J. Geophys. Res. , 108 (B5) : 365-381. |

| [] | Voegelé V, Cordier P, Sautter V, et al. 1998. Plastic deformation of silicate garnets:Ⅱ. Deformation microstructures in natural samples. Phys. Earth Planet. In. , 108 (4) : 319-338. DOI:10.1016/S0031-9201(98)00111-3 |

| [] | Wiens D A. 2001. Seismological constraints on the mechanism of deep earthquakes:temperature dependence of deep earthquake source properties. Phys. Earth Planet. In. , 127 : 145-163. DOI:10.1016/S0031-9201(01)00225-4 |

| [] | Wiens D A, Gilbert H J. 1996. Effect of slab temperature on deep-earthquake aftershock productivity and magnitudefrequency relations. Nature , 384 : 153-156. DOI:10.1038/384153a0 |

| [] | Wiens D A, McGuire J J, Shore P J, et al. 1994. A deep earthquake aftershock sequence and implications for the rupture mechanism of deep earthquakes. Nature , 372 : 540-543. DOI:10.1038/372540a0 |

| [] | Wiens D A, Snider N O. 2001. Repeating deep earthquakes:evidence for fault reactivation at great depth. Science , 293 : 1463-1467. DOI:10.1126/science.1063042 |

| [] | Wu Y Q, Jiang Z S, Wang M, et al. 2013. Preliminary results of the co-seismic displacement and pre-seismic strain accumulation of the Lushan MS7.0 earthquake reflected by the GPS surveying. Chinese Sci. Bull. (in Chinese) , 58 (20) : 1910-1916. |

| [] | Wyss M, Johnston A C, Klein F W. 1981. Multiple asperity model for earthquake prediction. Nature , 289 : 231-234. DOI:10.1038/289231a0 |

| [] | Xu X W, Wen X Z, Ye J Q, et al. 2008. The MS8.0 Wenchuan Earthquake surface rupture and its seismogenic structure. Seismology and Geology (in Chinese) , 30 (3) : 597-629. |

| [] | Yamasaki T, Seno T. 2003. Double seismic zone and dehydration embrittlement of the subducting slab. J. Geophys. Res. , 108 (B4) : 283-299. |

| [] | Yan R, Jiang C S, Shao Z G, et al. 2011. Research progress on the problem of fluid, heat and energy distribution near earthquake source area. Earthquake research in China (in Chinese) , 27 (1) : 14-28. |

| [] | Ye L L, Lay T, Kanamori H, et al. 2013. Energy release of the 2013 MW8.3 Sea of Okhotsk earthquake and deep slab stress heterogeneity. Science , 341 : 1380-1384. DOI:10.1126/science.1242032 |

| [] | Yu R D, Jin Z M. 2006. Relationship between dehydration of serpentine and intermediate-focus earthquakes in oceanic subduction zones. Earth Science Frontiers (in Chinese) , 13 (2) : 191-204. |

| [] | Yuan Y F. 2008. Loss assessment ofWenchuan Earthquake. Journal of Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Vibration (in Chinese) , 28 (5) : 10-19. |

| [] | Zang S X. 1984. Earthquake stress drop and the stress drops of rock fracture. Acta Seismologica Sinica (in Chinese) , 6 (2) : 182-194. |

| [] | Zhang J F. 2003. Experimental investigation on the deformation of eclogite at high temperature and high pressure[Ph. D. thesis] (in Chinese). Wuhan:China University of Geosciences. |

| [] | Zhai S T, Wu G, Zhang Y, et al. 2013. Research on acoustic emission characteristics of granite under high temperature. Chinese Journal of Rock Mechanics and Engineering (in Chinese) , 36 (1) : 351-356. |

| [] | Zhang J F. 2003. Experimental investigation on the deformation of eclogite at high temperature and high pressure[Ph. D. thesis] (in Chinese). Wuhan:China University of Geosciences. |

| [] | Zhang Y, Feng W P, Xu L S, et al. 2008. Spatio-temporal rupture process of the 2008 great Wenchuan earthquake. Science in China (Series D):Earth Science (in Chinese) , 38 (10) : 1186-1194. |

| [] | Zhao S T. 2012. Experimental investigation on the strength of the material near the 660 km discontinuity at high pressures and temperatures and its implications for geodynamics[Ph. D. thesis] (in Chinese). Wuhan:China University of Geosciences. |

| [] | Zhou Y. 1994. A new mechanism of deep-focus earthquakes:anticrack faulting. Geological Science and Technology Information (in Chinese) , 13 (4) : 5-12. |

2016, Vol. 59

2016, Vol. 59