2 Laboratory for Marine Mineral Resources, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266071, China;

3 State Key Laboratory of Marine Geology, School of Ocean and Earth Science, Tongji University, Shanghai 200092, China;

4 Key Laboratory of Marine Mineral Resources, Ministry of Land and Resources, Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey, Guangzhou 510760, China;

5 Third Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration, Xiamen Fujian 361005, China

Seismic oceanography method is a new marine investigative method using conventional seismic reflection method to image the water column for oceanographic research. Initially, Holbrook et al.(2003) published a paper applying seismic reflection method to study the thermohaline structures within the seawater column, revealing the ability of the application for oceanographic research. Then more and more related research results indicate that this method can be used to study many ocean processes quantitatively and qualitatively, including water mass boundary (Nandi et al., 2004 ), oceanographic front (Holbrook et al., 2003 ; Nakamura et al., 2006 ), mesoscale eddy (Ménesguen et al., 2009 ; Song et al., 2009 ; Biescas et al., 2008 ; Quentel et al., 2010 ; Mikiya et al., 2011 ; Tang et al., 2013 ; Tang et al., 2014a ), Meddy spiral arms (Song et al., 2011 ), large horizontal vortex (Sheen et al., 2012 ), internal wave (Holbrook and Fer, 2005 ; Krahmann et al., 2008 ; Song et al., 2009, 2010 ), internal tides (Holbrook et al., 2009 ), internal solitary waves (Tang et al., 2014b ; Bai et al., 2015 ), Lee waves (Eakin et al., 2011 ), the Kuroshio Current (Tsuji et al., 2005 ; Nakamura et al., 2006 ), currents in different seawater environments (Buffett et al., 2009 ; Mirshak et al., 2010 ; Pinheiro et al., 2010 ), various thermohaline structures (Holbrook et al., 2003 ; Tang and Zheng, 2011 ; Blacic and Holbrook, 2010 ) and the thermohaline staircase (Fer et al., 2010 ; Biescas et al., 2010 ). Compared with traditional methods of probing the ocean, seismic oceanography method can image large sections of the ocean and has better lateral resolution (Song et al., 2008 ). In addition, inversion results and quantitative analysis can be further obtained from the seismic sections (Ruddick et al., 2009 ; Papenberg et al., 2010 ; Song et al., 2010 ; Huang et al., 2011 ; Chen et al., 2013 ; Dong et al., 2013 ).

So far, oceanographic processes have caused more attention on seismic oceanography research. Actually, processes of marine sediment dynamics, cold seep, hydrothermal activity, marine biogeochemistry and so on can be studied by seismic oceanography, as long as the conditions of causing seismic reflection characteristics could be reached. However, very few studies have cared about these. Xu et al.(2012) found two obvious reflection cylinders with enhanced amplitude and inferred that they could be caused by seep plumes of methane and water disturbance, which was resulted from gas hydrate decomposition. Using a combination of seismic oceanographic and physical oceanographic data acquired across the Faroe-Shetland Channel, Vsemirnova et al.(2012) presented evidence of a turbidity layer that transports suspended sediment along the western boundary of the Channel. Hildebrand et al.(2012) provided seismic image of the water-column deep layer associated with the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Bai et al.(2014) speculated that bottom current developed and active pockmarks might exist in the Zhongjiannan Basin (ZB). In this paper, we put emphasis on these processes near the seafloor and try to analyze their seismic reflection characteristics.

The Benthic Boundary Layer/Bottom Boundary Layer (BBL) comprises the top layer of shallow sediment and the near-bottom layer of water, and is directly influenced by the properties, distribution, and the processes of the overlying water and sediments. The BBL is regarded as an interdisciplinary endeavour between physical oceanography and sedimentology. In the physical oceanography, the BBL is mainly determined by the height of the friction effect, top-down mainly including the logarithmic layer (turbulent boundary layer), viscous sublayer and diffusive sublayer, and to a large extent controlled by the hydrodynamic conditions, being an important interface for material exchange and energy transfer between the water column and sediments.(McCave, 1976 ; Boudreau and Jorgensen, 2001 ; Thomsen 2003a, 2003b ; Lorke and MacIntyre, 2009 ). Actually, there are many different definitions of the BBL depending on the scale, property and phenomenon researchers are concerned with (Boudreau and Jorgensen, 2001 ). Its research field is not just limited to the fluid dynamics processes, but includes biological processes, radiochemistry, biogeochemical processes and sediment dynamics (Richardson and Bryant, 1996 ). In this paper, the BBL refers to the water column near the seafloor, and we call all the processes of this region “seafloor processes”.

Unlike the seismic reflection characteristics in the water column, a large quantity of abnormal seismic reflection characteristics near the seafloor is found through analysis of many seismic sections in the South China Sea (SCS), which may reveal some complex ocean processes near the seafloor. Here, by using the seismic oceanography method to image the water column in the BBL, conventional analysis of seismic facies is applied to analyze, classify and summarize these abnormal seismic reflection characteristics, revealing possible ocean processes integrated with previous research results. Seismic oceanography can provide a new investigative method and research perspective of the BBL research, and further develop many new research fields for seismic oceanography. More research work in this field helps to know the water movements and various ocean processes near the seafloor, thus revealing the nature of the interaction between the solids and fluids of the earth system (Song, 2012 ).

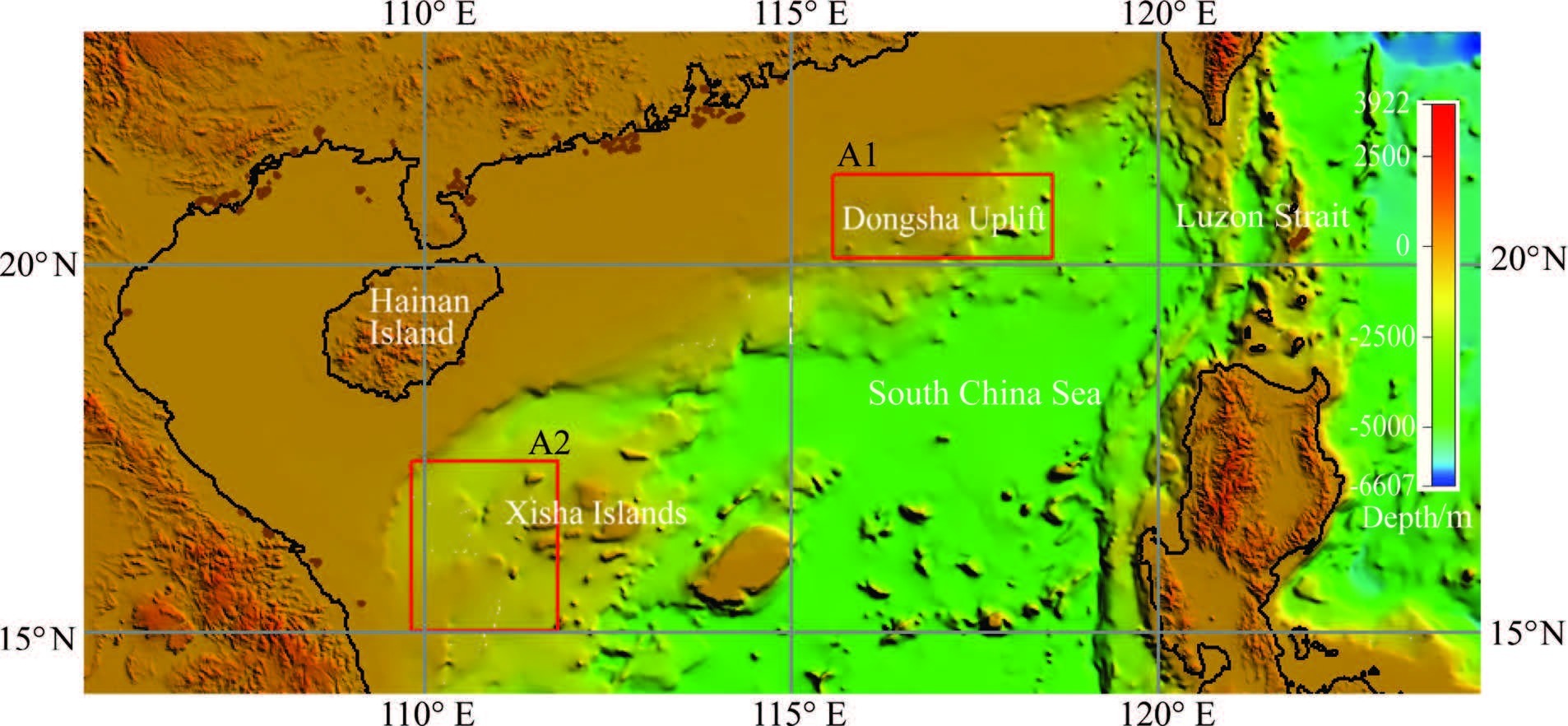

2 DATA AND METHODSIn recent years, the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey has acquired a large amount of multichannel seismic reflection sections in the northern and western SCS. The study areas are mainly concentrated on the northern ZB and the Dongsha Uplift (DU). The DU (Fig. 1, A1) is located in the southeast of the Pearl River estuary and belongs to a secondary tectonic unit of the eastern central uplift belt of the Pearl River Mouth basin, which is the most prominent topography on the continental shelf/slope of the northern SCS. The water depth is 0∼1000 m deep. This area is mainly composed of two submarine plateaus. One is circular and located at the outer edge continental shelf break, and the atoll developed in its central area dozens of meters above the sea level is the Dongsha Island (DI). The other one is diamond-shaped, 100 km northwest of DI, mainly made of three underwater shoals. This area is mainly influenced by currents of a branch of Kuroshio Current from the Luzon strait, tides and the Pearl River, the seabed is seriously eroded and a lot of sand dunes and erosional valleys develop (Luan et al., 2010, 2011 ). The northern ZB is located at a terrace topography in the west of the Xisha Islands at depth of 400∼1000 meters. Compared with the Southern ZB, the Cenozoic sedimentary strata of this region is thin, and a variety of circular, elliptical, elongated, crescent and irregular pockmarks of 1000∼2000 meters in diameter and deep water channels develop. This area remains at a low exploration degree (Sun et al., 2011 ; Chen et al., 2015 ).

Many seismic sections are reprocessed to image the BBL. The processing sequence of multichannel seismic reflection data for imaging water column and the shallow sediment layer is as follows:(1) geometry definition, direct wave suppression, amplitude compensation, high-pass frequency filtering, CMP sorting, constant velocity stacking (seawater velocity) and FK filtering in some water column sections. Some seismic sections imaging the strata are processed by the following sequence:(2) data quality control, amplitude compensation, bandpass frequency filtering between 6 Hz and 100 Hz, multiple attenuation, deconvolution, velocity analysis, normal moveout correction, stacking of CMP-sorted traces, post-stack noise attenuation, bandpass frequency filtering between 4 Hz and 70 Hz and FX migration. The swath bathymetry data was acquired with a Seabeam2112 system by the vessel “Ocean IV” and the processing sequence mainly consists of: navigation filtering, parameters calibration, correction for transducer draft, correction for sound velocity and data filtering. The cell size of raster grids used here is ca. 100 m×100 m and the vertical resolution is ca. 3% of the water depth.

A seismic facies unit is a mappable three-dimensional unit of reflections whose characteristics differ from that of the adjacent facies, which is the foundation of the seismic stratigraphy and sequence stratigraphy. These units consist of areas where specific reflection characteristics are detected and distinguished mainly based on the internal reflection organization, continuity, amplitude and frequency contents, showing seismic responses from the sedimentary facies (Sangree and Widmier, 1977 ; Brown and Fisher, 1980 ; Veeken, 2007, 2013 ). Seismic profiles of the water layer near the bottom reflect the features of fluid flow near the seabed, and seismic reflection characteristics are diverse and complex. Since their origin may involve different types of seafloor processes, the analysis and interpretation rely on no existing seismic model of fluid dynamics. Therefore, this paper tries to establish a preliminary seismic facies classification of the abnormal seismic reflection characteristics and analyze some possible seafloor processes.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONSWe classify a large number of seismic sections in the northern and western SCS, analyze and summarize some seafloor processes and its characteristics in seismic reflection profiles. Among them, the Turbulent Bottom Boundary Layer (TBBL) is widespread near the seafloor; the complex interactions between water currents and the rugged seafloor especially develop in areas with complex submarine topography and active bottom current. Their seismic reflection characteristics vary with different seawater flowing speed, which may be caused by sediment resuspension and moving; Internal solitary waves develop widely in the northern SCS, especially in the DU; Lee waves can be imaged behind ridges and rugged terrain; Widely distributed among the SCS, mesoscale eddies are not only the important ocean dynamic process, but also part of the sediment dynamic processes. They may collide with slope's seafloor, resulting in sediment suspension and mixing. Besides, seafloor leakage from sedimentary basins will form plumes, causing the resuspension of sediments and leading to formation of mini geomorphologies associated with fluid escape activities, such as pockmarks.

|

Fig. 1 The main study areas, A1(Dongsha Uplift) and A2(the northern Zhongjiannan Basin) |

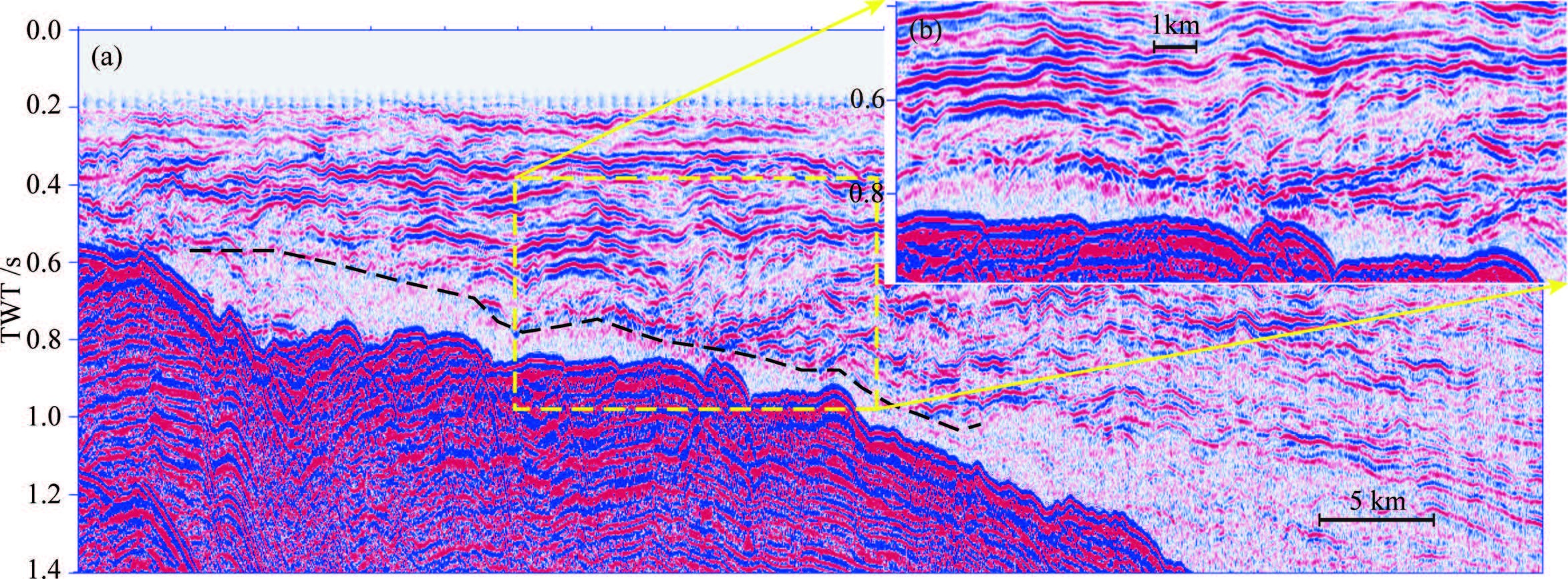

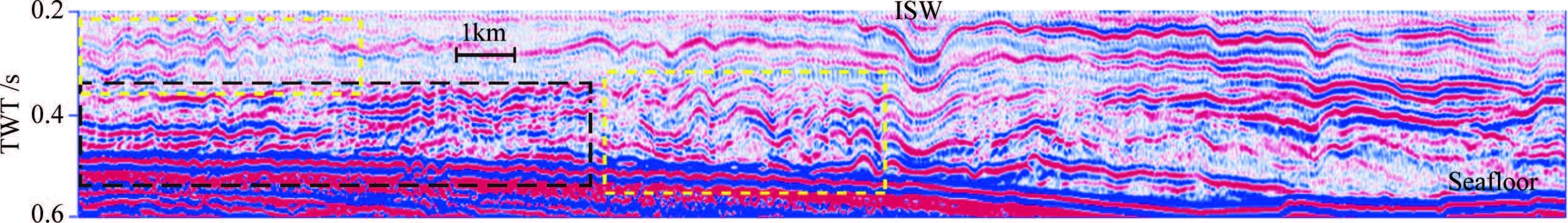

A large number of seismic reflection profiles in the northern SCS show vertical water-column structures similar to that in Fig. 2. This near-seafloor water layer lies on the continental slope of the northern SCS (Fig. 1, A1), and is separated from the overlying water by an obvious boundary (black dotted line in Fig. 1 ), presenting sheet drape with horizontally continuous distribution and almost parallel to the seafloor. Above the boundary, internal waves of the layered water develop, whose amplitude is higher than that below the boundary. This near-seafloor water layer shows weak chaotic seismic reflections and reduced apparent frequency.

|

Fig. 2 (a) The sheet drape seismic facies unit between seafloor and black dotted line may reflect the turbulent bottom boundary layer;(b) A larger version of the yellow dashed rectangle in Fig. 2a. Note that the upper boundary of turbulent bottom boundary layer shows burr shape and cut off many events. Seismic section was processed by sequence (1) |

Its overall characteristics show that the emergence of this water layer is in a close relationship to the seafloor, and we infer that it reflects the seismic reflection characteristics of the TBBL. Within the TBBL turbulent flow is characterized by eddies that are carried downstream in the direction of the general flow. As turbulence is an irregular rotational motion, eddies are formed and their energy is dissipated by transferring to smaller and smaller eddies (Thomsen, 2003b ). This suggests that the mixing effect of the TBBL is strong, and the internal components tend to be more uniform, causing weaker seismic reflection than that above the boundary. Toward the boundary, the TBBL comes up with shape of burr, and seismic events are terminated, indicating the TBBL is transforming into Ekman layer greatly influenced by the geostrophic effect. Thomsen (2003b) indicates that the TBBL at continental margins is in the order of 5 m to 50 m thick. However, this water layer is ca. 150 m thick on the left, mostly below 100 m thick and several meters thick in the thinnest region (Fig. 2b ). Since the viscous sublayer and diffusive sublayer is very thin near the sea bottom, the resolution of seismic reflection profile is not enough to image them. The water flow in this water layer may be associated with ocean current, tide or upwelling.

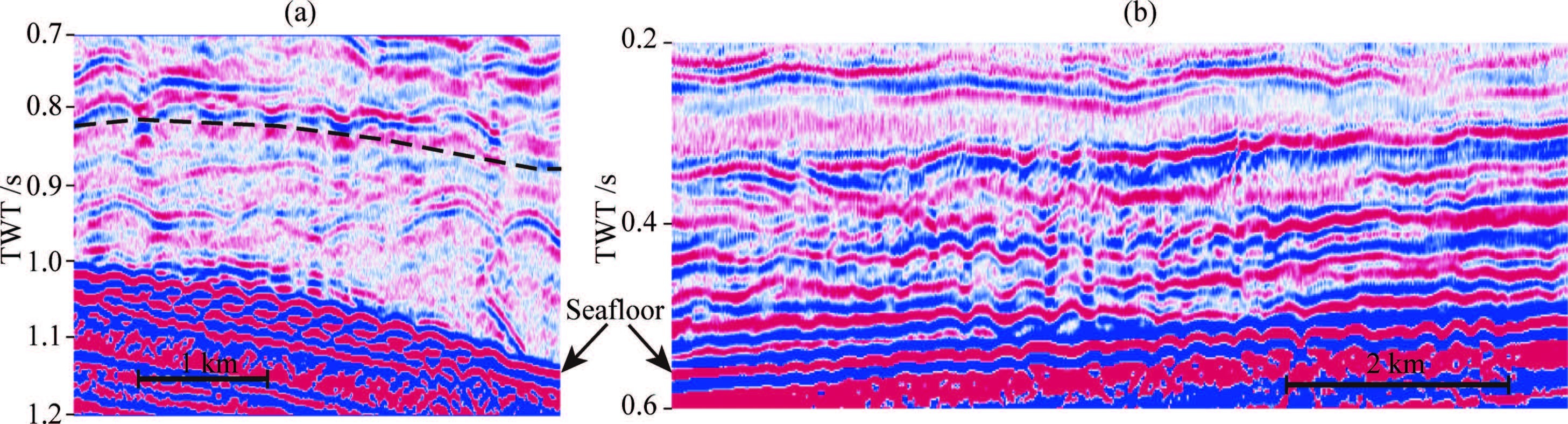

3.2 Suspended Sediment Caused by Interaction Between Rough Seafloor and the Bottom CurrentThe seismic section shown in Fig. 3 is located in the DU (Fig. 1, A1). Water flow near the seafloor is largely influenced by submarine topography. The water layer indicating the TBBL shows again (Fig. 3a ) similar to that in Fig. 2, and the black dotted line marks its top boundary. Seismic reflection presents weak amplitude, chaotic reflection characteristic on the left of the yellow dotted rectangle, and weak amplitude, turbid reflection characteristic in the middle and to the right part. Sand dunes ca. 200 m in wavelength develop in the zone of ca. 5 km long along the seafloor (Fig. 3b ). In addition, at an angle with the seafloor seismic events above the sand dunes show abnormal seismic reflection characteristic of low continuity and “wearing-hair” style with ca. 30 m in height. This seismic reflection configuration is in excellent agreement with the sand dunes, presenting blanket drape, higher amplitude than the surrounding seawater, medium-high apparent frequency, but weaker amplitude with higher height. We call it “hair-like” seismic reflection configuration.

|

Fig. 3 (a) The sheet drape seismic facies unit also develops between the seafloor and black dashed line, which is similar to Fig. 1 and indicates the turbulent bottom boundary layer.(b) A larger version of the yellow dashed rectangle in Fig. 3a. Sand dunes develop on the seafloor and hair-like reflection configuration grows above them. Flow patterns (c1, c3, c5) and distribution of suspended sediment (c2, c4, c6) at different phases during a wave cycle were calculated by Hansen et al.(1994) . The reflection pattern of hair-like reflection configuration is similar to c2, c6, referring to the reflection characteristic of suspended sediment above sand dunes;(b) Black arrow indicates the speculative direction of water flow. Seismic section was processed by sequence (1) |

The hair-like seismic reflection configuration generally develops above the sand dunes or high frequency rough seafloor and is similar to the flow patterns and distribution of suspended sediment at different phases (yellow rectangles in Fig. 3 (c1, c2, c5, c6) ) during a wave cycle over the ripples calculated by Hansen et al.(1994) . Hence, we speculate that it reflects the seismic response to the flow pattern and the distribution of suspended sediment caused by the interaction between rough seafloor and the bottom current. Besides, the low amplitude and frequency is generated by suspension sediment, but not the thermohaline difference, because the surrounding weak and chaotic seawater reflection characteristic indicates the thermohaline difference tends to be more uniform with the turbulent-mixing effect.

3.3 Interaction Between Bottom Current and the Rugged Submarine Topography Under Different Hydrodynamic ConditionsIn addition to hair-like reflection configuration, other two kinds of reflection configuration including high frequency small vertical offsets/“faults” and fluctuations also develop over the sand dunes as shown in Fig. 4, located in the DU. The TBBL in Fig. 4a shows internally weak amplitude, low continuity and medium frequency, and the mixing effect and hydrodynamic condition are relatively weak, compared with the TBBL in Fig. 3. The high frequency small vertical offsets consist of high amplitude and frequency and low continuity, as blanket drape over the sand dunes and distributed along the seafloor for ca. 3 km. In Fig. 4b, the high frequency fluctuations have the same properties within the layered seawater, but there is no much change in amplitude.

|

Fig. 4 (a) There is also high frequency small vertical offsets/“faults” reflection configuration above sand dunes. As similar to Fig. 2, seawater between the seafloor and the black dashed line refer to the reflection characteristic of turbulent bottom boundary layer;(b) High frequency fluctuations reflection configuration developing above the sand dunes. Seismic section was processed by sequence (1) |

According to the boundary layer theory, the laminar flow and turbulent flow will occur with the increase of flow velocity, alternating near the critical Reynolds number where the flow will be intermittent and oscillatory (Rott et al., 1990 ). Hence, we presume similar flow patterns will happen at sea bottom. As shown in Fig. 3, the two abnormal reflection characteristics are closely associated with seabed terrain fluctuation such as sand dunes, but show different properties. When the hydrodynamic environment is weak, the laminar flow will fluctuate with high frequency seabed terrain fluctuation, not enough to stir the seafloor sediments, but easy to promote internal seawater mixing. When the hydrodynamic environment is strong, the wavy flow starts to break to turbulence, causing resuspension of seafloor sediment and leading to enhanced reflection amplitude, high frequency and low continuity. When the hydrodynamic environment is further enhanced, the seawater will be more uniform due to strong turbulent mixing effect. Meanwhile, the resuspended sediment may drift in the flow direction, reflecting hair-like reflection configuration with high reflection amplitude and frequency. Therefore, the hydrodynamic environment may be from strong to weak as in order of Figs. 3b, 4a, 4b. High frequency small vertical offsets and fluctuations also develop in black and yellow dashed rectangles (Fig. 5 ) respectively.

3.4 Internal Solitary WaveA plenty of internal solitary waves develop near the DU, which are propagated from the Luzon strait where they are generated from the interaction between the strong tidal forcing and the abrupt topography (Ramp et al., 2004 ; Zhao et al., 2004 ). Traditional research approaches to study internal solitary waves mainly consist of remote sensing observation, mooring system, acoustic observation, numerical simulation and physical simulation method, yet Tang et al.(2014b) and Bai et al.(2015) indicate that compared with the above methods, the seismic oceanography method has important advantages in imaging the vertical structure of internal solitary wave, calculation of wave number spectrum and velocity estimation. As shown in Fig. 5, the internal solitary wave shows with the concave package, higher amplitude and longer wavelength compared with the internal waves nearby.

|

Fig. 5 High frequency small vertical offsets and fluctuations develop in black and yellow dashed rectangles respectively. Internal solitary wave (ISW) propagated along this section, with geometry of higher amplitude vertical solitary package. Seismic section was processed by sequence (1) |

Sand dunes, ridges and erosional valleys constitute the complex submarine topography near the DU (Fig. 1, A1). It's easy to form the Lee waves when ocean current flows over the ridges. Different from a lot of ocean observation and numerical simulation, Eakin et al.(2011) confirms that seismic oceanography method can image large-scale Lee wave, providing its vertical structure which can be used for further calculation and analysis. Seismic section as shown in Fig. 6 is acquired near the DU. Lee waves (LW1, 2, 3) form behind two high ridges (Ridge 1, 2) ca. 300 m and 200 m in height respectively, which have the typical geometry of large wave-height tilted solitary package with medium reflection amplitude and frequency.

|

Fig. 6 (a) Geometry of large amplitude tilted solitary package on sides of Ridges 1, 2 show the reflection characteristics of low-mode (LW1) and high-mode (LW2) Lee waves respectively. Lee Wave 3(LW3) probably indicates the energy dissipation of Lee wave, peeled away by ocean currents;(b) Schematic of form drag generated by stratified flow past a bump of height (Edwards et al., 2004 ), showing the low-mode Lee wave;(c) Displacement field of high-mode stationary wave simulated by Klymak et al.(2010) . Red arrow points the speculative direction of water flow along this section. Seismic section was processed by sequence (1) |

Reflection characteristic of LW1 is similar to the form drag simulated by Edwards et al.(2004) , indicating a low mode lee wave forming when stratified flow passed a bump of height (Fig. 6b ). LW2 is different from LW1 and is likely to reflect the characteristics of high mode Lee waves, like the displacement field of high mode waves simulated by Klymak et al.(2010) , as shown in the white dotted rectangle (Fig. 6c ). We also find another abnormal seismic reflection on the left side of the profile, that shows poor lateral continuity, high frequency fluctuations and low apparent frequency characteristics (LW3). We hypothesize that its causes are associated with Lee wave. When Lee wave breaks, it's drifting and mixing, forming the shape as shown in the white rectangle (Fig. 6c ). According to the consistency of the Lee waves (Figs. 6a, b, c), we infer that seawater flows from right to left in this section. LW3 originate around Ridge 2, drift from right to left after breaking and dissipate energy continuously, reflecting more complex internal reflection characteristics, like low continuity compared with LW2.

3.6 Eddy and the Interaction with SeafloorEddy is an important small and meso scale ocean phenomenon, which can be imaged by the seismic oceanography method (Biescas et al., 2008 ; Pinheiro et al., 2010 ). Furthermore, physical properties such as temperature, salinity, density and sound velocity can also be inverted (Papenberg et al., 2010 ; Song et al., 2010 ; Huang et al., 2011 ; Kormann et al., 2011 ; Chen et al., 2013 ; Bornstein et al., 2013 ; Biescas et al., 2014 ). Previous research results confirm that eddies usually show geometry of “lens”, like Meddy (Biescas et al., 2008 ; Song et al., 2009 ; Chen et al., 2013 ), or bowl shape with no clear upper boundary (Mikiya et al., 2011 ; Tang et al., 2014a ) and some may own spiral arms (Song et al., 2011 ). The findings not only provide the vertical structure of eddies, but also to some extent change our traditional knowledge.

|

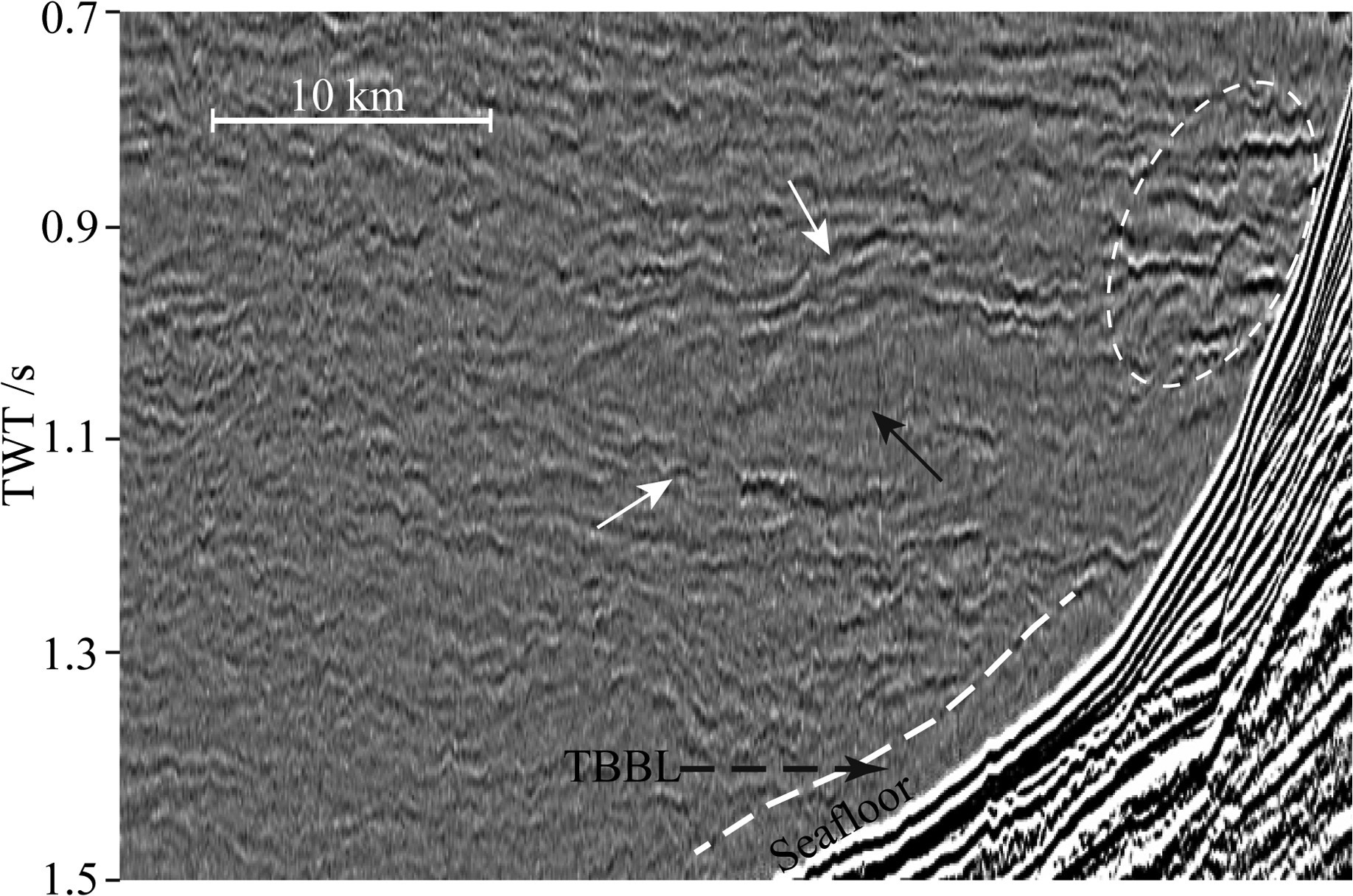

Fig. 7 As similar to Fig. 2, water column between the seafloor and the white dashed line indicates the turbulent bottom boundary layer. Lenticular reflection configuration reveals the characteristic of an eddy with structure of the eddy core water (black arrow) and the eddy mixed water (white arrow). High amplitude reflection characteristics in white dashed ellipse indicate the suspended sediment caused by intense mixing of turbulence resulted from the interaction of the seafloor and eddy. Seismic section was processed by sequence (1) |

Unlike previous studies, near the seabed we discover a large number of eddies on the northern continental slope of the SCS. At ca. 800 m depth near the seabed, there exists an eddy (Fig. 7 ), with lenticular geometry, ca. 20 km long and ca. 300 m thick. The seismic section located in the study area A2(Fig. 1 ) reveals that its vertical structure consists of the eddy core water with relatively homogeneous and weak amplitude seismic reflection characteristic (black arrow) and the eddy mixed layer with low continuity, high amplitude and low frequency seismic reflection characteristic (white arrow). It collides with the continental slope to the right, by which the eddy core water is even influenced. Above it in the white dashed ellipse, seismic reflection is chaotic, with relatively high amplitude, and the events come up along the slope, we speculate that eddy is confined by the slope, producing a plenty of turbulences and resuspended sediments upwelling. The TBBL develops between the seafloor and white dotted line, where seismic reflection is homogeneously chaotic with weak amplitude, apparently different from that above the line. Its characteristic below the eddy is in contrast with the seismic reflection above, indicating the TBBL inside and above the eddy is obviously influenced and the high amplitude is caused as a result of the sediment resuspension.

3.7 Seepage and (Bubble) PlumeAccording to the above analysis, all the ocean currents and eddies may cause the seafloor sediment resus pension, reflected in the seismic reflection profile. Many pockmarks may develop on the seafloor, resulted from eroded topography by fluid escape activity (Judd and Hovland, 2007 ). Previous research reports that a plenty of pockmarks are found in the northern and western continental shelf and slope of the SCS, and fluid escape activities are widely distributed (Chen et al., 2015 ).

Lots of seismic sections reveal abnormal seismic reflection characteristics in the overlying seawater above the pockmarks. Many circular and crescent pockmarks and soft sediment deformation are found in the western Xisha Islands, ca. 800 m deep (Fig. 8b ). Five pockmarks develop along the seismic line, labeled by 1-5 correspondingly (Figs. 8a, b). High frequency fluctuations present in the yellow dotted rectangle, and the hair-like reflection configuration with high amplitude exists on the sequential pockmarks (2-4). Beyond that, plume-like abnormal seismic reflection is homogeneously chaotic with low amplitude and frequency, developing above the 1st and 5th pockmarks. Since these always show above the pockmarks and its shape is similar to the hydroacoustic flares (Fig. 8c ) detected by the high frequency acoustic method (Rollet et al., 2006 ; Valdes et al., 2007 ; Logan et al., 2010 ; Jones et al., 2010 ; Etiope et al., 2013 ), we speculate these seismic reflection characteristics are closely associated with the pockmarks, revealing the fluid escape activities (water, natural gas, loose sediments and so on) of active pockmarks, fed by fluid escape features (like faults) with high amplitude reflections beneath them (Fig. 8a ).

3.8 Upwelling Currents in Pockmarks and Sediment ResuspensionUnlike features in Fig. 8a, broom geometric feature presents in PM1(Fig. 9a ), with chaotic reflections, relatively weak amplitude and low frequency inside. Numerical simulation and acoustic measurements indicate that currents may be deflected by the pockmark in a way that produces a positive vertical current component from the pockmark, leading to reduced sedimentation rate, winnowing of the fine fraction inside the pockmark and even make it deepen over time (Hammer et al. 2009). Geometry of the abnormal seismic reflection on PM1(Fig. 9a ) shows similar shape of the simulation result (Fig. 9c ), but PM2 and PM3 don't show. It means this phenomenon still needs the participation of fluid escape activity, that is to say, fluids migrate through fluid escape features (like small fractures or faults), escape from PM1 and are taken away with the suspended sediment by the upwelling (Fig. 9a ). PM2 and PM3 don't have obvious feeding pathways as PM1. Thus, fluid flow makes an important contribution to the formation of broom seismic reflection configuration.

|

Fig. 8 (a) Seismic section above and below the seafloor were processed in sequence (1) and jointed together along the seafloor. There are many pockmarks (white arrows) on the seafloor, which locations are pointed out by white arrows in the multi-beam topographic map (b). The black line shows the location of seismic line. The multi-beam topographic data was processed in sequence (3). High frequency fluctuations and hair-like reflection configuration develop in yellow and black dashed rectangles respectively. The geometry of plume seismic facies unit is similar to hydroacoustic flares (Jones et al., 2010 ), probably indicating the activity of methane seepage in pockmarks |

|

Fig. 9 (a) Seismic sections above and below the seafloor were processed in sequence (1) and (2) respectively and jointed together along the seafloor;(b) Slope map shows that there are many pockmarks (PM) and mud volcanoes (MV) on the seafloor. Red line indicates the location of seismic line;(c) Vertical component of current velocity resulted from numerical modeling, showing upwelling in a pockmark (Hammer et al., 2009 ), which we call the broom seismic facies unit. Red arrow (Fig. 9a ) indicates the speculative direction of water flow along this section. The multi-beam topographic data was processed in sequence (3) |

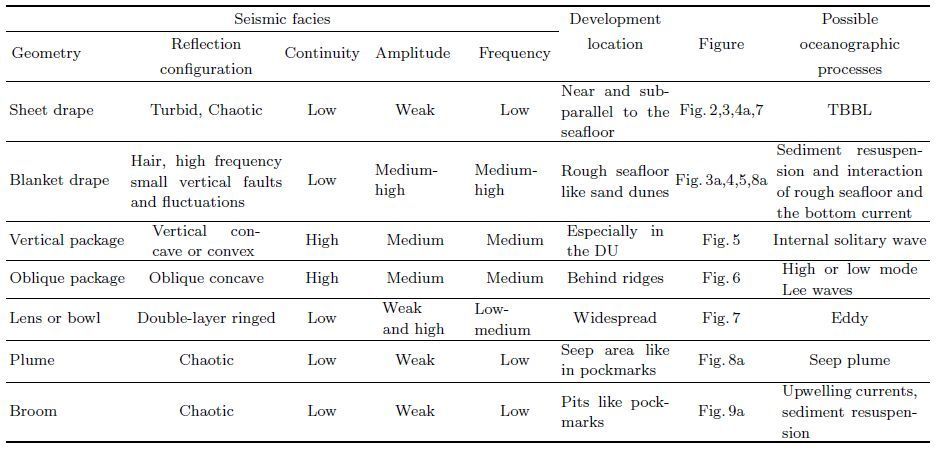

Compared with seismic profiles imaging internal seawater, seismic reflection characteristics of the seawater near the seafloor are more complicated, with various abnormal geometries and seismic attributes, which reflect a variety of ocean processes near the seafloor. Combined with previous research results, possible oceanographic processes are classified and summarized in Table 1.

|

|

Table 1 Possible oceanographic processes and associated seismic facies, revealed by various abnormal reflection seismic characteristics |

By reprocessing a large number of seismic data, we focus on the abnormal seismic reflection characteristics near the seabed, and analyze, classify and summarize their properties by using conventional seismic facies analysis method, including the geometry, reflection configuration, continuity, amplitude and frequency.

Seismic reflections near the seabed present more complex geometries and reflection configurations, probably revealing various complex oceanographic processes. Sheet seismic facies unit may reflect turbulent bottom boundary layer; hair-like reflection configuration can be caused by the sediment resuspension, resulted from the interaction of bottom current and high frequency undulating seafloor, such as sand dunes; owning the typical geometry of large amplitude tilted solitary package, Lee waves usually show behind the ridges; plume seismic facies unit indicate the characteristic of seepage plume; and broom seismic facies unit are closely associated with the upwelling currents, sediment resuspension and fluid escape activities in pockmarks. Besides, internal wave and eddy have already been confirmed by the seismic oceanography method. All the properties are summarized in Table 1.

Results indicate that seismic oceanography can image not only processes of the ocean water column, such as internal wave and eddy, but also some complex processes near the seabed. Actually, more complex and still remaining invisible oceanographic processes, such as gravity flows, contour current, hydrothermal activity, underwater landslides, various marine biological activities and so on, may also be studied by using the seismic oceanography method. However, considering features of suddenness, different scales and so on for different research subjects, this research field requires the combination of diverse detection methods.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThe seismic data presented here were collected by the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey. We are grateful to Zhenyu Feng, director of the data processing institute, Dr. Baojin Zhang and other colleagues for their kind help and support. This research work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41576047), and the State Key Program of the Major Research plan of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91128205).

| [] | Bai Y, Song H B, Guan Y X, et al. 2014. Structural characteristics and genesis of pockmarks in the northwest of the South China Sea derived from reflective seismic and multibeam data. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 57 (7) : 2208-2222. DOI:10.6038/cjg20140716 |

| [] | Bai Y, Song H B, Guan Y X, et al. 2015. Nonlinear internal solitary waves in the northeast South China Sea near Dongsha Atoll using seismic oceanography. Chin. Sci. Bull. (in Chinese) , 60 (10) : 944-951. DOI:10.1360/N972014-00911 |

| [] | Biescas B, Armi L, Sallarès V, et al. 2010. Seismic imaging of staircase layers below the Mediterranean Undercurrent. Deep Sea Research Part I:Oceanographic Research Papers , 57 (10) : 1345-1353. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr.2010.07.001 |

| [] | Biescas B, Ruddick B R, Nedimovic M R, et al. 2014. Recovery of temperature, salinity, and potential density from ocean reflectivity. Journal of Geophysical Research:Oceans , 119 (5) : 3171-3184. DOI:10.1002/2013JC009662 |

| [] | Biescas B, Sallarès V, PelegrÍ J L, et al. 2008. Imaging meddy finestructure using multichannel seismic reflection data. Geophysical Research Letters , 35 (11) : 213-226. |

| [] | Blacic T M, Holbrook W S. 2010. First images and orientation of fine structure from a 3-D seismic oceanography data set. Ocean Science Discussions , 6 (2) : 431-439. DOI:10.5194/os-6-431-2010 |

| [] | Bornstein G, Biescas B, Sallarès V, et al. 2013. Direct temperature and salinity acoustic full waveform inversion. Geophysical Research Letters , 40 (16) : 4344-4348. DOI:10.1002/grl.50844 |

| [] | Boudreau B P, Jorgensen B B. 2001. The Benthic Boundary Layer:Transport Processes and Biogeochemistry[M]. Oxford: Oxford University Press . |

| [] | Brown L F, FisherWL. 1980. Seismic Stratigraphic Interpretation and Petroleum Exploration. Tulsa:AAPG Department of Education. |

| [] | Buffett G G, Biescas B, PelegrÍ J L, et al. 2009. Seismic reflection along the path of the Mediterranean Undercurrent. Continental Shelf Research , 29 (15) : 1848-1860. DOI:10.1016/j.csr.2009.05.017 |

| [] | Chen J X, Guan Y X, Song H B, et al. 2015. Distribution characteristics and geological implications of pockmarks and mud volcanoes in the northern and western continental margins of the South China Sea. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 58 (3) : 919-938. DOI:10.6038/cjg20150319 |

| [] | Chen J X, Song H B, Bai Y, et al. 2013. The vertical structure and physical properties of the Mediterranean eddy. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 56 (3) : 943-952. DOI:10.6038/cjg20130322 |

| [] | Dong C Z, Song H B, Wang D X, et al. 2013. Relative contribution of seawater physical property to seismic reflection coefficient. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 56 (6) : 2123-2132. DOI:10.6038/cjg20130632 |

| [] | Eakin D, Holbrook W S, Fer I. 2011. Seismic reflection imaging of large-amplitude Lee waves in the Caribbean Sea. Geophysical Research Letters , 38 (21) : 1991-2014. |

| [] | Edwards K A, MacCready P, Moum J N, et al. 2004. Form drag and mixing due to tidal flow past a sharp point. Journal of Physical Oceanography , 34 (6) : 1297-1312. DOI:10.1175/1520-0485(2004)034<1297:FDAMDT>2.0.CO;2 |

| [] | Etiope G, Christodoulou D, Kordella S, et al. 2013. Offshore and onshore seepage of thermogenic gas at Katakolo Bay(Western Greece). Chemical Geology , 339 : 115-126. DOI:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.08.011 |

| [] | Fer I, Nandi P, Holbrook W S, et al. 2010. Seismic imaging of a thermohaline staircase in the western tropical North Atlantic. Ocean Science , 6 (3) : 621-631. DOI:10.5194/os-6-621-2010 |

| [] | Hammer Ø, Webb K E, Depreiter D. 2009. Numerical simulation of upwelling currents in pockmarks, and data from the Inner Oslofjord, Norway. Geo-Marine Letters , 29 (4) : 269-275. DOI:10.1007/s00367-009-0140-z |

| [] | Hansen E A, Fredsøe J, Deigaard R. 1994. Distribution of suspended sediment over wave-generated ripples. Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal, and Ocean Engineering , 120 (1) : 37-55. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-950X(1994)120:1(37) |

| [] | Hildebrand J A, Armi L, Henkart P C. 2012. Seismic imaging of the water-column deep layer associated with the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Geophysics , 77 (2) : EN11-EN16. DOI:10.1190/geo2011-0347.1 |

| [] | Holbrook W S, Fer I. 2005. Ocean internal wave spectra inferred from seismic reflection transects. Geophysical Research Letters , 32 (15) : 297-318. |

| [] | Holbrook W S, Páramo P, Pearse S, et al. 2003. Thermohaline fine structure in an oceanographic front from seismic reflection profiling. Science , 301 (5634) : 821-824. DOI:10.1126/science.1085116 |

| [] | Holbrook W S, Fer I, Schmitt R W. 2009. Images of internal tides near the Norwegian continental slope. Geophysical Research Letters , 36 (24) : L00D10. |

| [] | Huang X H, Song H B, Pinheiro L M, et al. 2011. Ocean temperature and salinity distributions inverted from combined reflection seismic and XBT data. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 54 (5) : 1293-1300. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0001-5733.2011.05.018 |

| [] | Jones A T, Greinert J, Bowden D A, et al. 2010. Acoustic and visual characterisation of methane-rich seabed seeps at Omakere Ridge on the Hikurangi Margin, New Zealand. Marine Geology , 272 (1-4) : 154-169. DOI:10.1016/j.margeo.2009.03.008 |

| [] | Judd A G, Hovland M. 2007. Seabed Fluid Flow:the Impact on Geology, Biology and the Marine Environment[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press . |

| [] | Klymak J M, Legg S M, Pinkel R. 2010. High-mode stationary waves in stratified flow over large obstacles. Journal of Fluid Mechanics , 644 : 321-336. DOI:10.1017/S0022112009992503 |

| [] | Kormann J, Biescas B, Korta N, et al. 2011. Application of acoustic full waveform inversion to retrieve high-resolution temperature and salinity profiles from synthetic seismic data. Journal of Geophysical Research:Oceans (1978-2012) , 116 (C11) : 476-487. |

| [] | Krahmann G, Brandt P, Klaeschen D, et al. 2008. Mid-depth internal wave energy off the Iberian Peninsula estimated from seismic reflection data. Journal of Geophysical Research:Oceans (1978-2012) , 113 (C12) : 101-106. |

| [] | Logan G A, Jones A T, Kennard J M, et al. 2010. Australian offshore natural hydrocarbon seepage studies, a review and re-evaluation. Marine and Petroleum Geology , 27 (1) : 26-45. DOI:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.07.002 |

| [] | Lorke A, MacIntyre S. 2009. The benthic boundary layer (in Rivers, Lakes, and Reservoirs).//Encyclopedia of Inland Waters. Oxford:Academic Press, 505-514. |

| [] | Luan X W, Peng X C, Wang Y M, et al. 2010. Characteristics of sand waves on the Northern South China Sea shelf and its formation. Acta Geologica Sinica (in Chinese) , 84 (2) : 233-245. |

| [] | Luan X W, Zhang L, Peng X C. 2012. Dongsha erosive channel on northern South China Sea Shelf and its induced Kuroshio South China Sea Branch. Sci. China Earth Sci. , 55 (1) : 149-158. DOI:10.1007/s11430-011-4322-y |

| [] | McCave I N. 1976. The Benthic Boundary Layer[M]. US: Plenum Press . |

| [] | Ménesguen C, Hua B L, Papenberg C, et al. 2009. Effect of bandwidth on seismic imaging of rotating stratified turbulence surrounding an anticyclonic eddy from field data and numerical simulations. Geophysical Research Letters , 36 (24) : 146-158. |

| [] | Mikiya Y, Kanako Y, Yoshio F, et al. 2011. Seismic reflection imaging of aWarm Core Ring south of Hokkaido. Exploration Geophysics , 42 (1) : 18-24. DOI:10.1071/EG11004 |

| [] | Mirshak R, Nedimović M R, Greenan B J W, et al. 2010. Coincident reflection images of the Gulf Stream from seismic and hydrographic data. Geophysical Research Letters , 37 (5) : 137-147. |

| [] | Nakamura Y, Noguchi T, Tsuji T, et al. 2006. Simultaneous seismic reflection and physical oceanographic observations of oceanic fine structure in the Kuroshio extension front. Geophysical Research Letters , 33 (23) : 265-288. |

| [] | Nandi P, Holbrook W S, Pearse S, et al. 2004. Seismic reflection imaging of water mass boundaries in the Norwegian Sea. Geophysical Research Letters , 31 (23) : 345-357. |

| [] | Papenberg C, Klaeschen D, Krahmann G, et al. 2010. Ocean temperature and salinity inverted from combined hydrographic and seismic data. Geophysical Research Letters , 37 (4) : 379-384. |

| [] | Pinheiro L M, Song H B, Ruddick B, et al. 2010. Detailed 2-D imaging of the Mediterranean outflow and meddies off W Iberia from multichannel seismic data. Journal of Marine Systems , 79 (1-2) : 89-100. DOI:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2009.07.004 |

| [] | Quentel E, Carton X, Gutscher M A, et al. 2010. Detecting and characterizing mesoscale and submesoscale structures of Mediterranean water from joint seismic and hydrographic measurements in the Gulf of Cadiz. Geophysical Research Letters , 37 (6) : 53-67. |

| [] | Ramp S R, Tang T Y, Duda T F, et al. 2004. Internal solitons in the northeastern South China Sea. Part I:Sources and deep water propagation. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering , 29 (4) : 1157-1181. |

| [] | Richardson M D, Bryant W R. 1996. Benthic boundary layer processes in coastal environments:An introduction. Geo-Marine Letters , 16 (3) : 133-139. DOI:10.1007/BF01204500 |

| [] | Rollet N, Logan G A, Kennard J M, et al. 2006. Characterisation and correlation of active hydrocarbon seepage using geophysical data sets:an example from the tropical, carbonate Yampi Shelf, Northwest Australia. Marine and Petroleum Geology , 23 (2) : 145-164. DOI:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2005.10.002 |

| [] | Rott N. 1990. Note on the history of the reynolds number. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics , 22 : 1-12. DOI:10.1146/annurev.fl.22.010190.000245 |

| [] | Ruddick B, Song H B, Dong C Z, et al. 2009. Water column seismic images as maps of temperature gradient. Oceanography , 22 (1) : 192-205. DOI:10.5670/oceanog |

| [] | Sangree J B, Widmier J M. 1977. Seismic stratigraphy and global changes of sea level, part 9:seismic interpretation of clastic depositional facies. AAPG Bulletin , 62 (5) : 752-771. |

| [] | Sheen K L, White N J, Caulfield C P, et al. 2012. Seismic imaging of a large horizontal vortex at abyssal depths beneath the Sub-Antarctic Front. Nature Geoscience , 5 (8) : 542-546. DOI:10.1038/ngeo1502 |

| [] | Song H B, Bai Y, Dong C Z, et al. 2010. A preliminary study of application of Empirical Mode Decomposition method in understanding the features of internal waves in the northeastern South China Sea. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 53 (2) : 393-400. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0001-5733.2010.02.017 |

| [] | Song H B, Dong C Z, Chen L, et al. 2008. Reflection seismic methods for studying physical oceanography:Introduction of seismic oceanography. Progress in Geophysics (in Chinese) , 23 (4) : 1156-1164. |

| [] | Song G B, Pinheiro L, Wang D X, et al. 2009. Seismic images of ocean meso-scale eddies and internal waves. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 52 (11) : 2775-2780. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0001-5733.2009.11.012 |

| [] | Song H B, Pinheiro L M, Ruddick B, et al. 2011. Meddy, spiral arms, and mixing mechanisms viewed by seismic imaging in the Tagus Abyssal Plain (SW Iberia). Journal of Marine Research , 69 (4-6) : 827-842. |

| [] | Song H B. 2012. On relationship between physical process and geological process in South China Sea Deep. Journal of Tropical Oceanography (in Chinese) , 31 (3) : 10-20. |

| [] | Song Y, Song H B, Chen L, et al. 2010. Sea water thermohaline structure inversion from seismic data. Chinese J. Geophys.(in Chinese) , 53 (11) : 2696-2702. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0001-5733.2010.11.017 |

| [] | Sun Q L, Wu S G, Hovland M, et al. 2011. The morphologies and genesis of mega-pockmarks near the Xisha Uplift, South China Sea. Marine & Petroleum Geology , 28 (6) : 1146-1156. |

| [] | Tang Q S, Zheng C. 2011. Thermohaline structures across the Luzon strait from seismic reflection data. Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans , 51 (3) : 94-108. DOI:10.1016/j.dynatmoce.2011.02.001 |

| [] | Tang Q S, Wang D X, Li J B, et al. 2013. Image of a subsurface current core in the southern South China Sea. Ocean Science Discussions , 9 (6) : 631-638. |

| [] | Tang Q S, Gulick S P S, Sun L T. 2014a. Seismic observations from a Yakutat eddy in the northern Gulf of Alaska. Journal of Geophysical Research:Oceans , 119 (6) : 3535-3547. DOI:10.1002/2014JC009938 |

| [] | Tang Q S, Wang C X, Wang D X, et al. 2014b. Seismic, satellite, and site observations of internal solitary waves in the NE South China Sea. Scientific Reports , 4 : 5374. |

| [] | Thomsen L, van Weering T, Blondel P, et al. 2003a. Margin buildingregulating processes.//Ocean Margin Systems. Berlin Heidelberg:Springer, 195-203. |

| [] | Thomsen L. 2003b. The Benthic Boundary Layer/Ocean Margin Systems[M]. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer: 143 -155. |

| [] | Tsuji T, Noguchi T, Niino H, et al. 2005. Two-dimensional mapping of fine structures in the Kuroshio Current using seismic reflection data. Geophysical Research Letters , 32 (14) : L14609. |

| [] | Valdes D, Dupont J P, Laignel B, et al. 2007. A spatial analysis of structural controls on Karst groundwater geochemistry at a regional scale. Journal of Hydrology , 340 (3-4) : 244-255. DOI:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2007.04.014 |

| [] | Veeken P C H. 2007. Seismic Stratigraphy, Basin Analysis and Reservoir Characterisation. Handbook of Geophysical Exploration. Oxford:Elsevier Science. http://cn.bing.com/academic/profile?id=632680023&encoded=0&v=paper_preview&mkt=zh-cn |

| [] | Veeken P C H. 2013. Seismic Stratigraphy and Depositional Facies Models[M]. Netherlands: Academic Press . |

| [] | Vsemirnova E A, Hobbs R W, Hosegood P. 2012. Mapping turbidity layers using seismic oceanography methods. Ocean Science , 8 (1) : 11-18. DOI:10.5194/os-8-11-2012 |

| [] | Xu H N, Xing T, Wang J S, et al. 2012. Detecting seepage hydrate reservoir using multi-channel seismic reflecting data in Shenhu area. Earth Science-Journal of China University of Geosciences (in Chinese) , 37 (S1) : 195-202. DOI:10.3799/dqkx.2012.S1.020 |

| [] | Zhao Z X, Klemas V, Zheng Q A, et al. 2004. Remote sensing evidence for baroclinic tide origin of internal solitary waves in the northeastern South China Sea. Geophysical Research Letters , 31 (6) : L06302. |

2016, Vol. 59

2016, Vol. 59