2 Key Laboratory of Tectonics and Petroleum Resource of Ministry of Education, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430074, China;

3 Research Institute of Petroleum Exploration & Production, SINOPEC, Beijing 100083, China

The Paizhouwan region of the Jianghan plain, mid Yangtze area located in Jiayu County, Hubei Province, is a small structure unit belong to the Chenhu-Tuditang synclinorium situated in the central of the Mid Yangtze area.The preservation conditions of the marine petroleum and gas in the study area are relatively better, as the effect of the tectonic movements happened during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic period is comparatively weak and the stratigraphy here is still gently. Since 1990s, there are two most important deep/ultra-deep drilling Well PC1 and Well PS1 have been carried out in the central of the Paizhouwan region, which revealed all the strata that deposited during the Cenozoic, Mesozoic, Paleozoic and also Sinian stage in the study area, which also could show the importance of the study area in the marine petroleum and gas exploration for the whole South China. There are large amounts of asphalt appeared in the core of these two drillings, that show evidence that the study area has enormous potential for marine petroleum and gas exploration. In addition, these two deep/ultra-deep drillings provides the basement to study the marine hydrocarbon accumulation and redistribution in the study area and even the whole Yangtze plate.

However, the previous research focus on the tectonic and thermal history in the study area is relatively less, the methods used before are mainly the conventional technologies, such as fluid inclusion, vitrinite reflectance analysis and basin modeling, which could not give the exact information that could show the time of the tectonic or thermal events that the sediments experienced during their evolution. Fission Track and (U-Th)/He dating could record both temperature and time information of the tectonic and thermal events that the sediments experienced during their evolution, their analysis results are widely used in tectonic and thermal analysis in the sedimentary basin (Gleadow et al., 2002; Armstrong, 2005; Zheng et al., 2005; Tian et al., 2011). In order to understand the tectonic and thermal history of the study area deeply, we collected samples from these two deep/ultra-deep drillings systemically, and carried out amounts of apatite and zircon fission track and (UTh)/He analysis and the corresponding low-temperature thermal history inversion; combined with traditional vitrinite reflectance analysis and basin modelling, intensively discuss the dynamic process of the tectonic and thermal evolution in the study area, and also provide more evidences for the further research on the marine petroleum accumulation and reconstruction of the study area and even the whole Yangtze plate.

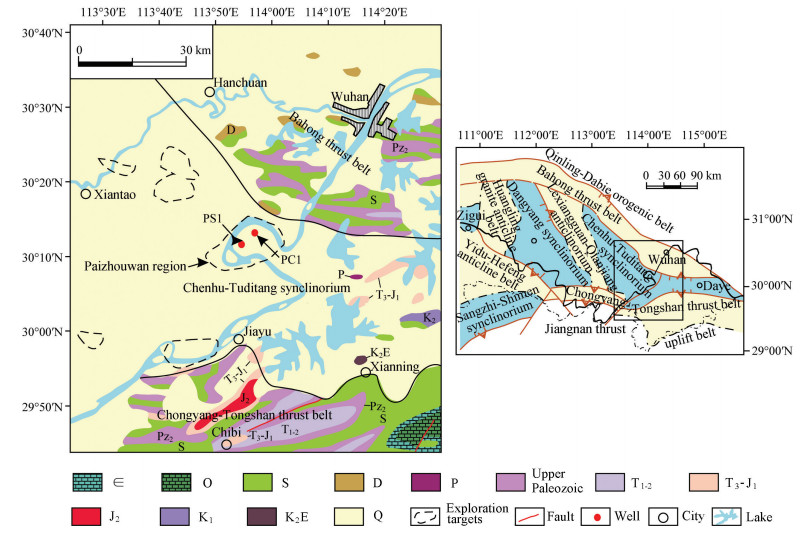

2 GEOLOGICAL BACKGROUNDThe Jianghan plain located in the central part of Yangtze plate and outlined by the Qinling-Dabie orogenic belt to the north and the Jiangnan thrust uplift belt to the south, is a middle-scale petroliferous basin developed on the late Proterozoic metamorphic basement.The main structure units developed in the Jianghan plain are the Huangling anticline belt, Dangyang synclinorium, Lexiangguan-Qianjiang anticlinorium, Chenhu-Tuditang synclinorium, Chongyang-Tongshan thrust belt and Bahong thrust belt (Guo et al., 2005) (Fig. 1). The basin has undergone series of tectonic evolution stages including the Caledonian, Hercynian, Indosinian, Yanshan and Himalayan.The type of the sedimentary basin varied from the craton basin during the Late Sinian-Middle Triassic to the foreland basin during the late Triassic-Jurassic, then to the depression rift basins during the late Cretaceous to Paleogene and finally to be the compressed basin during Neogene stage. The thickness of the marine strata formed in the study area during the Sinian to the Middle Triassic is over 8000 10000m.There are five sets of the marine source rocks developed including the Upper Sinian, the Lower Cambrian, the Upper Ordovician-Lower Silurian, the Permian and the Lower Triassic and Two independent petroleum system formed in the basin. Nowadays, most of the petroleum found in the basin is from the late Cretaceous to Neogene strata (Peters et al., 1996); However, the marine formation in the study area has also become one of the most important targets for exploring marine petroleum, especially gas in China in recent years (Liu, 2010, 2002; Ma et al., 2004; Ma, 2007), as there are enormous thickness of marine sediments deposited and nearly 1000 m of marine source rocks accumulated during the late Sinian to the middle Triassic stage and there are a huge number of oil and gas seepage found in the marine strata underneath or around the basin (Mei and Fei, 1992; Peters et al., 1996; Liu et al., 2008)

|

Fig. 1 The simply geological map of the east part of Jianghan basin and the location of the studied area |

The Paizhouwan region located in the east edge of Chenhu-Tuditang synclinorium, Jianghan plain, is surrounded by the Chongyang-Tongshan thrust belt in the south and the Bahong thrust belt in north (Fig. 1). It also experienced multiple stages of deep burial, uplift and erosion events and deposited enormous thickness of the marine sediments from the late Sinian to the middle Triassic period together with the Jianghan plain, although there were small-scale sedimentary hiatus or uplift and erosion. During the early Yanshanian period (~210 Ma), the Sino-Korean plate began to move towards southwest, collide with the Yangtze plate along the Qingling-Dabie orogenic belt (Ames et al., 1996). The type of Jianghan basin turned to foreland basin and the study area inflexed fiercely and received large number of Jurassic sediments because of the resistance of the Chongyang-Tongshan thrust belt and even the Jiangnan thrust uplift belt. During the second stage of Yanshan movement, as the collision became more intense, the study area began to uplift and be eroded seriously as the whole middle Yangtze area. In the late Yanshanian-early Himalayan stage, controlled by the Pacific plate subduction to the Eurasian plate or/and the upper crust extension, the study area began tension, and the study area began tension, and received the terrestrial sediments from the late Cretaceous to Paleogene, but the maximum thickness of the sediments accumulated in the study area is much thinner than the average thickness deposited in the Jianghan basin. During the late Cenozoic stage, the Jianghan plain began to depression and received the sediments under the nearly east-west direction extrusion but only several parts of the basin accumulated very thin Neogene strata. After that the study area began to uplift and erosion again for the influence of Himalayan movement. The main purpose of this paper deeply understands the tectonic and thermal evolution since Yanshanian stage in the study area, for its significant influence on the marine petroleum formation and reconstruction.

3 SAMPLES AND EXPERIMENT METHODSIn this study, eight samples are selected systemic with depth varying from 700m to 4100m of these two representative deep/ultra-deep marine drillings Well PS-1 and well PC-1 (Fig. 1), which located in the central of the study area (Fig 1). Because of there is no enough drilling core, only one sample from well PC1 is drilling core and all the other samples are drilling cuttings. Except two samples from Lower Silurian strata, all the other six samples are taken from middle-lower Jurassic and Upper Triassic and and the lithology of these samples are all detrital sediments include sandstone, siltstone and also grit stone (Table 1).

|

|

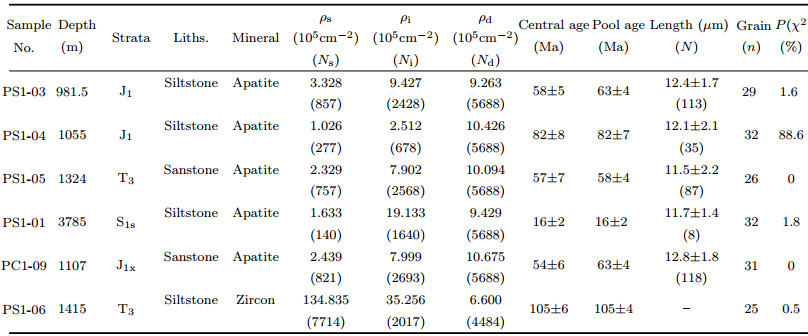

Table 1 The measured results of fission track dating by EDM of Well PS1 and PC1 |

The fission track experiments using external detector method (Gleadow, 1981 are finished at Institute of High Energy Physics of CAS (Chinese Academy of Sciences). The Spontaneous FT are revealed by 5.5 mol HNO3 for 20 s at 20 ℃ and by~25 h with NaOH/KOH (=1:1) eutectic etchant at 210 ℃ for apatite and for zircon, respectively; Muscovite used as an external detector after irradiation were etched in 40% HF for 20 min at 25 ℃. All samples were irradiated in a well-thermalized neutron flux in the 492 Swim Reactor at Beijing and Neutron fluence was monitored using the CN5 uranium dosimeter glass for apatite and CN2 for zircon samples (Bellemans et al., 1994). Fission track densities in both natural and induced fission track populations were measured at ×1000 magnification. Only those crystals with prismatic sections parallel to the c-crystallographic axis were accepted for analysis, these crystals being of a high etching efficiency. In this analysis, as many as possible confined fission track lengths (Gleadow, 1986) were measured (up to~100) for each apatite sample. Fission track ages were calculated using the IUGS-recommended Zeta calibration approach (Hurford and Green, 1982, 1983; Hurford, 1990). Errors were calculated using the techniques of Green (1986). The weighted mean zeta values for apatite used in this study are 389.4±19.2 and 85.4±4 for zircon.

Helium dating was carried out in the School of Earth Sciences at the University of Melbourne. Apatite and zircon grains were immersed in ethanol and examined under polarised light to detect possible mineral inclusions. Only clear euhedral grains with average grain radii in a restricted size range within each aliquot were selected. Criteria for grain quality, grain size and geometry followed the routine described by Farley (2002). Digitised photographs were taken of all grains for the calculation of the α-correction factor (Farley et al., 1996; Hourigan et al., 2005). Single grains were loaded into Pt capsules and thermally outgassed under vacuum at~910 ℃ for 5 minutes for apatites and at~1250 ℃ for 40 minutes for zircons using a fibre-optically coupled diode laser with 820 nm wavelengths. Following extraction 4He abundances were determined by isotope dilution using a pure 3He spike, calibrated against an independent 4He standard using a Balzers quadrupole mass spectrometer. A hot blank was run after each extraction, under the same outgassing conditions for apatite and zircon indicated above, to verify complete outgassing of crystals. The uncertainty in the sample 4He volume measurement is estimated as < 1%. With each batch of apatites analysed Durango apatite was also run as an internal standard and served as a check on sample accuracy. U-Th-Sm data for apatites were acquired via total dissolution in HNO3 of outgassed apatite and analysed using an Agilent 7700 series ICP-MS. For this procedure the reference material BHVO-1 was used as a calibration standard and Mud Tank apatite and international rock standard BCR-2 were used as check standards and run together with each batch of samples analysed. For zircons, following He extraction, grains were transferred from the laser chamber and removed from their Pt capsules. They were then placed in Parr bombs, spiked with 233U and 229Th and digested following a procedure described by Evans et al. (2005), followed by analysis for U and Th using an Agilent 7700 series ICP-MS. For single crystals digested in small volumes (0.3~0.5 mL), U and Th isotope ratios were measured to a precision of < 2%. Fish Canyon Tuff zircon was also run as an internal standard with each batch of samples analyzed and served as an additional check on analytical accuracy. Analytical precision for the University of Melbourne He facility is assessed conservatively to be±6.2% (±1σ) or less, which incorporates the α-correction-related constituent and takes into account an estimated 5 m uncertainty in grain size measurements (but does not consider uncertainties in overall grain geometry or possible heterogeneous U and Th distribution), gas analysis and ICP-MS uncertainties. Accuracy and precision of U, Th and Sm content ranges up to 2% (at±2σ), but is typically better than 1%.

Following measurement, fission track data and (U-Th)/He results were modeled using the annealing model of Laslett et al. (1987) and the HeFTy v 1.6.7 program (Ketcham, 2009; Ketcham et al., 2007) and the modeling result was tested used the method described by Gallagher (1995).

4 RESULTS 4.1 Apatite Fission Track ResultsIn recent years, with the development of research on apatite fission track annealing kinetics and controlling factors, the understanding of closure temperature or partial annealing temperature of apatite fission track is more clear. Generally, apatites with high F content, low Cl content, relatively small like Durango apatite are supposed to easy annealing and the maximum temperature that could be recorded is 110±10 ℃ (Gleadow et al., 1983; Gallagher et al., 1998). So far, the recognized maximum temperature that the apatite fission track (Dpar > 3.0 µm) could record exceeds 150 ℃ (Ketcham et al., 1999; Farley, 2002), whereas in this paper, the partial annealing temperature 60~120 ℃ is chosen as the kinetics parameters (Dpar) of the measured samples are all less than 2.0 µm.

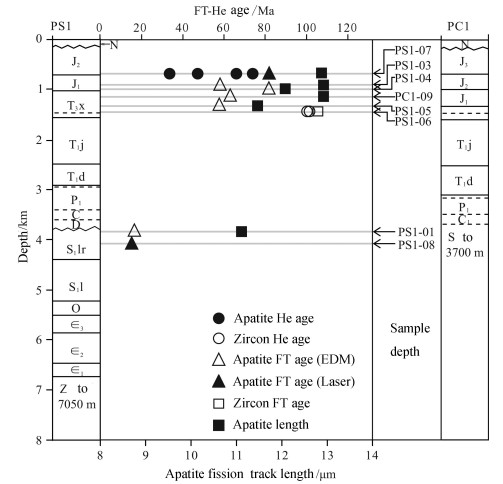

4.1.1 Apatite fission track results by external detector methodSix samples of apatite fission track from Well PS1 and PC1 were analyzed using external detector method and the results are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2. More than 25 grains have been detected for all of these five samples. Except for PS1-04, whose P (χ2) value is 88.6% and the pool age is used, the other four samples have the values of P (χ2) all less than 5%, indicating that the apparent ages of these samples are composed by two or more series of age compositions, and the central ages are chosen for analysis.

|

Fig. 2 The measured results of fission track dating by EDM of Well PS1 and PC1 |

The apparent apatite fission track ages of 4 samples from Upper Triassic-Mid Jurassic strata from Well PS1 and PC1 vary from 54±6 Ma to 82±7 Ma, all less or much less than the actual age of the formation, which indicated that the samples experienced apatite fission track partial annealing zone during the late Cretaceous to early Paleogene stage. The sample PS1-06, from depth 3785 m, is still in the apatite fission track partial annealing zone because of its deep burial.

As many confined fission tracks are detected, the mean track length (MTL) distributions range from 11.5 µm to 12.8 µm, with standard deviation between 1.1 µm and 2.4 µm (Table 1 and Fig. 2). The mean track lengths from the upper four samples are bimodal according to Gealdow et al. (1986), there are short length tracks especially for sample PS1-04 and PS1-05. For sample PS1-01, only 8 confined fission tracks are found.

4.1.2 Apatite fission track results by LA-ICP-MS methodThe analysis results of sample PS1-07 and PS1-08 using laser ICP-MS method in School of Earth Sciences, the University of Melbourne are shown in Fig. 3. The apparent fission track age of these two samples is 82.2 Ma and 13.6 Ma, respectively, which could correspond to the results of the sample from almost the same depth by external detector method. Samples PS1-07 also confirmed that this sample experienced apatite fission track partial annealing zone in Late Cretaceous period. Whilst the sample PS1-08, due to its deep burial, is still in the apatite fission track partial annealing zone.

|

Fig. 3 The measured results of fission track dating by Laser-ICPMS of Well PS1 |

The three dimension confined fission track length revealed by 252Cf irradiation at the School of Earth Science, the University of Melbourne is 12.86±1.4 µm and the standard deviation is 1.4 µm (Fig. 3). The mean track length distribution is also bimodal. Whilst for sample PS1-01, also revealed by 252Cf irradiation, no enough confined fission track is found for analysis.

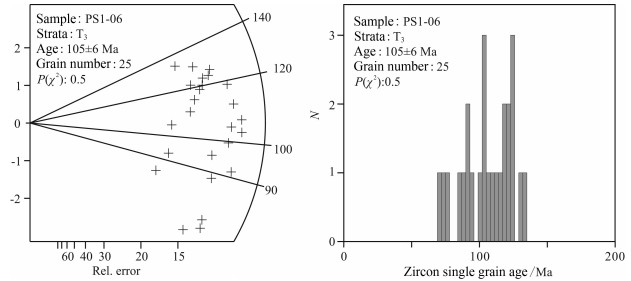

4.1.3 Zircon fission track analysisLots of research work have been done on the boundaries of the temperature of partial annealing zone or closure temperature for zircon (Hurford 1986; Yamada et al., 1995; Tagami and Shimada 1996; Brandon et al., 1998; Garver and Bartholomew 2001; Bernet et al., 2002; Riley, 2002). The annealing of fission track in zircon is mainly determined by temperature, time, cooling rate, α-radiation damage and/or pressure (Bernet and Garver, 2005) and the value of α-radiation damage increases with time, uranium and thorium concentrations. At the same time, the lower boundary might decrease down to~200 ℃ with the increasing of the accumulation of α-radiation damage (Garver and Bartholomew, 2001; Riley, 2002). By recent research of Tagami and Shimada (1996), the temperature of zircon annealing for a heating duration of about 106 years is between 210 and 320 ℃. This range is also supported by the results of laboratory annealing experiments (Yamada et al., 1995; Tagami et al., 1998). The borehole data shows that a relatively stable temperature of at least 200 ℃ for one million year-long is required for zircon fission track annealing (Hasebe et al., 2003). By analyzing the field in Olympic Mountains, an effective closure temperature of 240±30 ℃ is given (Brandon et al., 1998). By comparison with the above results, in this essay, a value of 205±18 ℃ is chosen as the temperature range of zircon fission track partial annealing (ernet et al., 2002).

The zircon fission track results of sample PS1-06 from Well PS1 are showed in Table 1 and Fig. 4; 25 grains have been measured for this sample. The apparent zircon fission track age of this Mesozoic sample is 105±6 Ma, which is much less than the depositional age, with the P (χ2)-value of 0.5%, which indicate that this sample has experienced zircon partial annealing zone during the end of the earlier Cretaceous stage.

|

Fig. 4 The measured results of zircon fission track dating the sample PS1-06 of Well PS1 |

The uncertainty of the chemistry characters of the dated zircon grains gives large room for speculation on their thermal properties. The relationship between uranium contents and single grain zircon fission track ages of these three samples is shown in Fig. 4. The samples show a narrow range of uranium content varying from 139.64 ppm to 296.34 ppm and the high uranium contents always have a correlation with young zircon fission track ages.

4.2 (U-Th)/He Results(U-Th)/He chronology of high precision and low human factor is a new hot-point and frontier field for low temperature thermochronology and even for geochronology in recent years. Now (U-Th)/He dating has been widely used in tectonic evolution reconstruction and thermal history study of sedimentary basins, as their analysis results also can record both temperature and time information that the geological body experienced during its evolution (Qiu et al., 2009). Apatite and zircon is the most popular mineral for (U-Th)/He dating, the previous study based on large amounts of helium diffusion experiments and field research show that the helium partial retain temperature zone is 45~80 ℃ and 160~200 ℃ for these two kind mineral, and the closure temperature is 60 ℃ and 180 ℃, respectively.

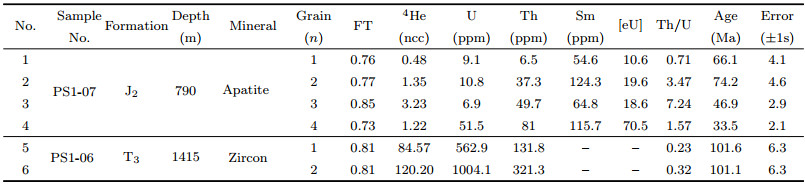

Only two samples PS1-07 and PS1-06 from Well PS1 are used for (U-Th)/He test in this research, and the results are shown in Table 2. For sample PS1-07, the value of FT correction for four apatite particles analyzed is from 0.73 to 0.85 (Farley et al., 1996) the 4He contents vary from 0.48 nnc to 3.23 nnc, and the effective uranium content is 10.6~70.5 ppm, with the value of Th/U between 0.71 and 7.24 (Table 2). The apparent (U-Th)/He age of these four apatite grains is between 33.5–74.2 Ma, with an average age of 55.2 Ma, and the error is 2.1–4.6 Ma. These results give evidence that the strata of Well PS1 in the study area has been cooled to the temperature zone of apatite He closure (60 ℃) in the late Paleogene, which also indicates that the thickness of the Paleogene sedimentation in the study area should not be too large and the Mesozoic strata achieving the maximum temperature should be during the Yanshan period.

|

|

Table 2 The Apatite and zircon (U-Th)/He dating results of Well PS1 in the study area |

The value of FT correction of two zircon grains of sample PS1-06 is both 0.81. The 4He contents of these two grain are 84.6 nnc and 120.2 nnc, the uranium contents are 1562.9 ppm and 1004.1 ppm, with the value of Th/U 0.23 and 0.32 (Table 2), respectively. These two zircon grains get very close zircon (U-Th)/He age which is 101.6 Ma and 101.1 Ma, respectively, and the error is 6.3 Ma. The analysis results of this sample are also consistent with the zircon fission track age of the same sample. The experiment results proved that the study area experienced a rapid uplift and the sample cooled to zircon helium closure (~180 ℃) at the end of the early Cretaceous stage. Assuming the paleo-temperature gradient during the Mesozoic period is 30~35 ℃·km−1, the burial depth of the sample at this point should be around 4700~5500 m, the Mesozoic sedimentation thickness should be~6000 m and the total erosion thickness of the Mesozoic formation is about 3500~4000 m.

By analyzing the relationship between fission track, (U-Th)/He ages and the depth (Fig. 5), the maximum depth of apatite fission track partial annealing zone of Well PS1 and PC1 is about 4600 m, the estimated present-day temperature gradient is~19.5~21.6 ℃·km−1, which consists well with the measured value~20.0 ℃·km−1 by well testing during drilling. Furthermore, the upper Triassic-Lower Jurassic strata in the study area cooled to the zircon fission track and (U-Th)/He closure temperature zone, with the paleo-temperature 160~210 ℃ at the end of the early Cretaceous stage; and then the strata cooled to apatite partial annealing zone, with the paleo-temperature 60~120 ℃ in late Cretaceous stage. And finally the temperature decreased to 45~80 ℃ and the strata reach the apatite partial He retain zone in the early Paleogene stage. The fission track and helium analysis results give evidences that the tectonic uplift erosion and cooling event happened in the study area since Yanshanian stage should be a continuous event. There may be some late Cretaceous-Paleogene sediments deposition when the Jianghan basin began extension and subsidence and receive large amounts of Paleogene sedimentation, but the total thickness of this formation in the study area and its effect on temperature increase could be ignored.

|

Fig. 5 The relationship between fission track, (U-Th)/He results and depth of Well PS1 and PC1 |

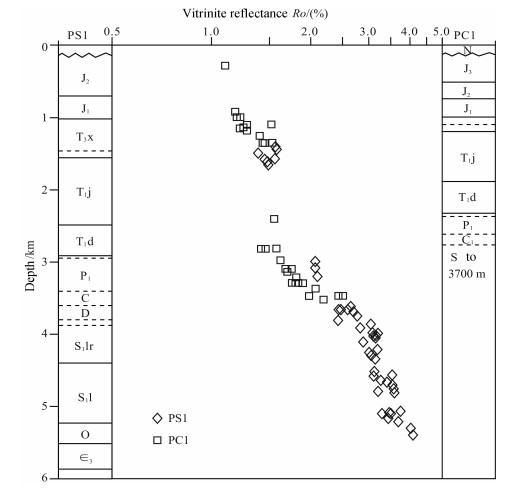

The vitrinite reflectance method is a very useful technique applied in petroleum geology and thermal analysis of sedimentary basin. It increases with temperature, and thus depth and can be regarded as a measurement of the highest temperature experienced by organic matter in a rock and does not undergo retrogression with uplift or cooling (Cope, 1986; Sweeney and Burnham, 1990; Taylor et al., 1998). The vitrinite reflectance data of 86 samples of these two wells are used in this study in attempt to analyze the thermal history, to compare with the results of apatite and zircon fission track data and also to give constraints to thermal modeling.

The vitrinite reflectance of Well PS1 and Well PC1 shows good logarithmic relationship with depth (Fig. 6). The vitrinite reflectance increases with increasing depth. The vitrinite reflectance from Permian to the Silurian section of Well PC1 is slightly lower than the normal trend built by these two wells, may be caused by the characteristic of kerogen, poor or rich hydrogen, the test condition or even related to human factors (Buiskool, 1983; Wilkins et al., 1992; Bensley and Crelling, 1994). By the analysis results, the vitrinite reflectance values from the upper Triassic-Lower Jurassic strata of these two wells range from 1.16% to 1.72%, which proved that the strata have experienced high paleogeothermal after its sedimentation and the source rocks have reached high maturity stage. Although the present-day burial depth is no more than 2000 m, the maximum burial depth of this section should be~6600 m and the missed thickness is about 4100~4600 m by vitrinite reflectance results. Unfortunately, only by vitrinite reflectance data we cannot distinguish when the strata reach the largest depth and experienced the maximum temperature.

|

Fig. 6 The relationship between vitrinite reflectance and depth of Well PS1 and PC1 in the study area |

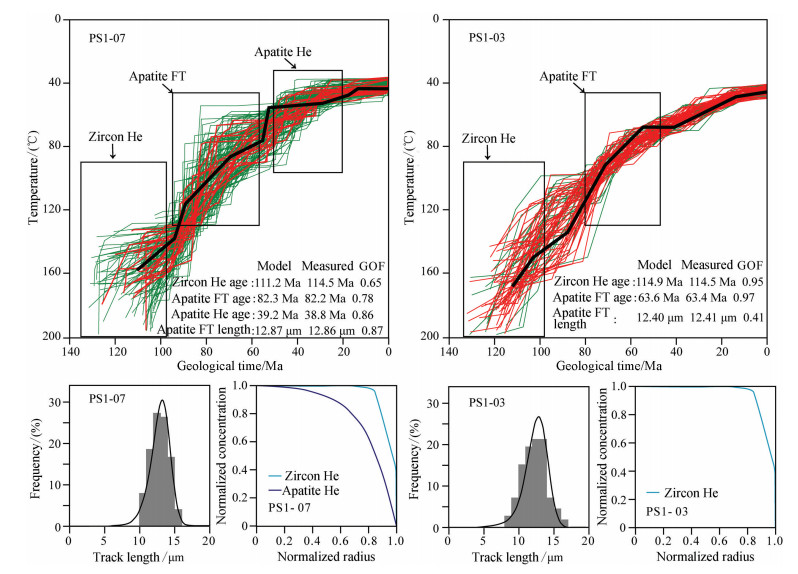

Modeling the thermal history using HeFTy 1.6.7 (Ketcham, 2009), fission track and (U-Th)/He data of the sedimentary basin requires some basic constraints on the time-temperature conditions of each sample. Actually, the sedimentation time, the maximum paleo-temperature and the present-day temperature are needed. The range of present-day temperature given is calculated by the sample depth and by DST temperature gradient, and the temperature range is derived by the temperature gradient of the whole Jianghan basin (27~33.5 ℃·km−1) (Yu and Hu, 1986; Guo et al., 2005; Yuan et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2010). The surface temperature at the time of deposition is speculated to be~10~25 ℃ and the average temperature today is~18 ℃.

In order to deeply understand the tectonic and thermal history of the study area, two samples PS1-07 and PS1-03 of the well PS, for which the number of confined fission track is more than 100, are used for thermal modeling. The zircon (U-Th)/He, apatite fission track and (U-Th)/He data are used as constraints for thermal modeling for sample PS1-07; and zircon (U-Th)/He and apatite fission track data used for sample PS1-03.

The model result of sample PS1-07 is showed in Fig. 7. The modeled zircon (U-Th)/He age, apatite fission track age and (U-Th)/He ages is 111.2 Ma, 82.3 Ma and 39.2 Ma, which is very close to the measured result 114.5 Ma (α corrected He ages), 84.6 Ma and 38.8 Ma (α corrected He ages), with the value of GOF 0.65, 0.46 and 0.86, respectively. Simulated confined fission track length is 12.86 µm which is also close to the measured result and the GOF is 0.87 (Fig. 7). Further, the characteristic of modeled track length distribution is also consistent with the measured result.

|

Fig. 7 The modeled time-temperature thermal history based on fission track and (U-Th)/He of Well PS1 |

For sample PS1-03, about 50 thermal evolution history paths were obtained from thermal modeling (Fig. 7). The modeled zircon (U-Th)/He age and apatite fission track age is 114.9 Ma and 63.6 Ma, which is consistent with the measured results 114.5 Ma (α corrected He ages), and 63.4 Ma, with the value of GOF 0.95 and 0.97, respectively. The modeled confined fission track length is 12.40 µm, which is also close to the measured result (12.41 µm).

By the thermal modeling (Fig. 7), the paleo-temperature of the mid-Jurassic strata increased rapidly after its deposition, reached its maximum temperature during the middle of the early Cretaceous and made the zircon helium age reset. We can’t get more detail for heating process as there is no other more effective thermal indicator or more strata information. The study area begun to uplift and cool in the early Cretaceous (>~116 Ma), the corresponding paleo-temperature is >~160 ℃. The tectonic uplift and erosion cooling event continued until to the early Paleogene (~55 Ma), and the temperature of these two samples decreased to 59 ℃ and 71 ℃, respectively. The variation of the paleo-temperature during the Paleogene stage is relatively small, only~10 ℃ and~18 ℃ for these two samples.

There are some differences between the thermal evolution histories in Paleogene stage of these two samples, which may be caused by the apatite constraint for the thermal modeling. For sample PS1-07, there is a rapid cooling at the beginning of the Paleogene stage, the sample PS1-03 is not as obvious as sample PS1-07. Conversely, the cooling rate of sample PS1-03 in the late Paleogene is significantly greater than sample PS1-07. The thermal model results show that the Jurassic strata of Well PS1 should achieve its maximum paleo-temperature in the early Cretaceous stage, experienced a large-scale rapid uplift cooling event during the end of early Cretaceous to the late Cretaceous period.

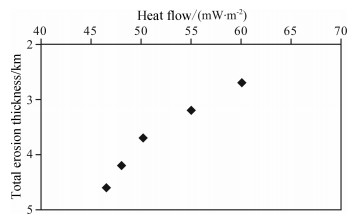

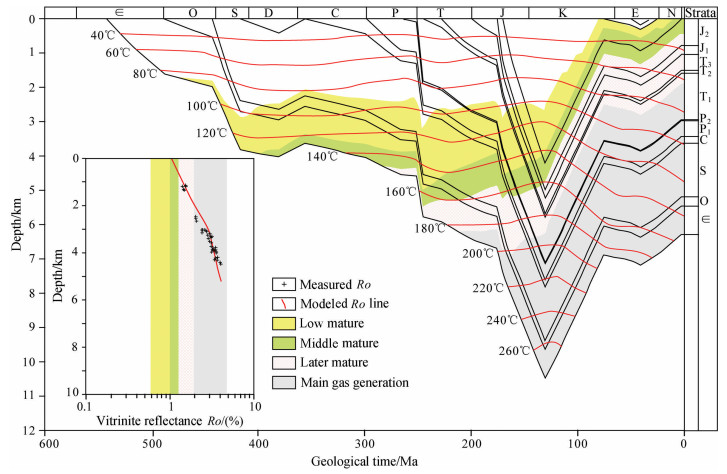

5.2 Basin ModelingBasin modeling is one of the most critical method for thermal analysis and paleo-temperature evolution for basin analysis and petroleum geology research, previous researchers have finished lots of work on its effectiveness and sensitivity (Ungerer et al., 1990; Waples et al., 1992, 1992; Sweeney et al., 1995). In this essay, Well JY1 in the study area was chosen for burial and thermal history analysis; the stratigraphic and lithologic data required for the simulation is based on actual drilling mud logging lithology and stratification, the thermal conductivity and the heat flow are also from the actual measured results of drilling cores in the Jianghan basin (Guo et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2010; Qiu et al., 2002), the present temperature is measured directly during well drilling.

The relationship between the paleo-heat flow and the total erosion thickness before the erosion obtained by basin modeling is showed in Fig. 8. The paleo-heat flow is~47.06 mW·m−2~60.07 mW·m−2 when the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic strata achieved its maximum depth in the early Cretaceous, the corresponding total erosion thickness varies from 2700~4800 m. By combined analysis of zircon fission track and (U-Th)/He, vitrinite reflectance analysis and basin model results, the paleoheat flow~48.38 mW·m−2 and the total erosion thickness 4300 m is the most reasonable.

|

Fig. 8 The relationship between erosion thickness and paleo-heat flow of the Well PS1 in the study area |

The thermal analysis results show that the paleo-heat flow is stable, with an average value of~53.64 mW·m−2. The paleo-heat flow began to decrease at the end of early Jurassic, and decreased to~48.38 mW·m−2 before the huge tectonic uplift and erosion happened in the early Cretaceous stage. During the middle and late Jurassic, the Yangtze plate began to depress as the Huabei plate collided with the Yangtze plate, the Paizhouwan area may be located in the subsidence center and received large a mounts of Jurassic sediments, the heat flow moved toward the surrounding of the sediment basin and the upper low temperature fluid penetrated deeper strata, which maybe caused the decrease of heat flow in the study area. Since the late Cretaceous, the heat flow decreased gradually to the current value~42 mW·m−2.

The paleo-temperature increase of the upper Triassic-Lower Jurassic strata of PS1 is relatively slow since its sedimentation, and the maximum temperature of the bottom of the upper Triassic reached~60~65 ℃ at the end of the early Jurassic (Fig. 9). Since the middle and late Jurassic deposition, the temperature increased rapidly as the sedimentary rate increased obviously. Before the regional tectonic uplift and cooling event happened during the early Cretaceous, the upper Triassic and lower Jurassic strata achieved its maximum temperature 170~190 ℃ and 155~165 ℃, respectively, which caused zircon fission track partial annealing, apatite fission track and (U-Th)/He total reset. In the middle of early Cretaceous, the study area began to tectonic uplift and cool, and the bottom of the upper Triassic strata cooled to~100 ℃, the apatite fission track began to record the thermal history again. Although there may be temperature increase caused by the late Cretaceous-Paleogene sedimentaion and the strata re-bury again, its effect on temperature is negligible.

|

Fig. 9 The burial history and geothermal evolution process of the Well PS1 in the study area |

The paleo-temperature gradient is stable, with an average value of~35~39 ℃·km−1 during Ordovician to Carboniferous. Since the late Triassic to the early Cretaceous, the temperature gradient decreased to~33.4~35.7 ℃·km−1 gradually and was about 34.7 ℃·km−1 during the late Cretaceous to Paleogene period; and the present day value is 22 ℃·km−1 which is basically consistent with the measured result.

The source rock of the Permian formation reached low mature stage in the early Triassic stage, the vitrinite reflectance value (Ro) is~0.6%~1.0% and the temperature is about 100 ℃; it reached middle mature stage during the early Jurassic period, the Ro is about 1.0%~1.3%, and the temperature is about 140~160 ℃; and reached later mature stage in mid-late Jurassic stage, the Ro is about 1.3%~2.6%, and the temperature is~160~180 ℃. Before the tectonic uplift and erosion happened in the early Cretaceous, the source rock reached main gas stage, and achieved its maximum temperature 208~245 ℃. The paleo-temperature reduced to~155~175 ℃ at the end of early Cretaceous because of the regional tectonic uplift and cooling, and the current temperature is~120~135 ℃. Thus, the Paleozoic marine source rock reached maturity, and there is no large scale secondary re-burial and re-heat events, there could not be large scale secondary hydrocarbon event happened. So, the future petroleum exploration in the study area should focus on preservation condition and hydrocarbon redistribution which may be affected by tectonic event.

5.3 DiscussionThe maximum temperature that the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic strata experienced during the Mesozoic constrained by zircon fission track and helium, vitrinite reflectance data and basin modeling is~145~190 ℃, and the corresponding total erosion thickness is~4300 m. The collision and suturing of the Huabei plate and Yangtze plate happened in the mid-late Triassic (240–210 Ma). Since then, the Huabei plate compressed in the direction of southwest and the main stress field in the mid Yangtze turned to southwest direction. Blocked by the Jiangnan-Xuefeng orogenic belts, the main stress field in the mid Yangtze turned to south-southwest or south direction. Because of the compression, the study area, even the whole Jianghan plain of the mid Yangtze area received the early Jurassic sedimentation, which is preserved very well in the basin today. However, the thickness of the early Jurassic sedimentation is thin and changes little in the whole Jianghan plain. In the Paizhouwan area, the thickness of the lower Jurassic revealed by Well PS1 and Well PC1 is 353 m and 343 m; the total thickness of the lower Jurassic including Jianshandian formation, Dawangchong formation and Chengchao formation controlled by outcrops in southeast Hubei province is only~396 m. The thickness of the lower Jurassic controlled by all the other drillings in the whole Jianghan plain is 283~542 m. The thickness in Zigui area and Dangyang area controlled by outcrops is~200 m and~250~380 m, respectively. The reason for the early Jurassic sedimentation in the study area being thin and stable may be attributed to the fact that the scale of the depression during this period is relatively weak and the lack of sufficient sediments source supply.

During the middle and late Jurassic, the collision of the Huabei plate with the Yangtze plate became further exacerbated and the study area underwent intense compression and depression. Meanwhile, the weather of the mid Yangtze area became dry and the orogenic belts around the Jianghan plain were uplifted and eroded quickly, which provided enough sediments source. The thickness from outcrops of Luojiahu formation of the middle Jurassic and Majiashan formation of the upper Jurassic in the Daye-Echeng area in southeast Hubei province is >1053 m. Although the residual thickness of the middle and upper Jurassic in Dangyang area revealed by well drilling and outcrops is 148~377 m and~427 m, that in southeast Hubei province is only~396 m. The thickness of the lower Jurassic controlled by all the other drilling in the whole Jianghan plain is 283~542 m. The thickness in Zigui area and Dangyang area controlled by outcrops is~200 m and~250~380 m, the deposition thickness may exceed 5000 m. The thickness of the middle Jurassic and the upper Jurassic in the Zigui basin controlled by outcrops is >2810 m and >3000 m. Combined with some early Cretaceous strata remaining in the east of the study area, there should be large scale middle and late Jurassic, and even early Cretaceous sediments deposition, and the thickness should be around 5000 m; the current thickness of the Jurassic in the study area is thin, which could be ascribed to the large scale tectonic uplift and erosion during Yanshanian and Himalayan period.

The zircon fission track age and (U-Th)/He age of the Well PS1 is~110–100 Ma, the thermal modeling results show that the timing of the tectonic uplift and erosion in the study area is earlier than 116 Ma, which together give the evidences that the regional tectonic uplift and erosion event began in the early Cretaceous. The previous analysis results show that the tectonic uplift and erosion, the orogenic activity, the emplacement of igneous rocks and lithology changes, and even Tan-Lu fault slip surrounding the study area happened during~140–110 Ma. Combined with the fact that there are still some early Cretaceous strata remaining in the east of the study area, the timing for the tectonic uplift-erosion and cooling should be in the early stage of the early Cretaceous (140–130 Ma) rather than the end of the late Jurassic; the corresponding huge regional tectonic uplift and erosion process took place during the middle of the early Cretaceous to the late Cretaceous.

In addition, the basin began extension and subsidence since the late Cretaceous, which may be affected by Pacific plate subduction down to the Eurasia plate or/and the upwelling of the upper mantle. Although there was large scale deposition during the late Cretaceous to the beginning of the Paleogene, the deposition is controlled by the NW and NNW-trending faults and the sedimentary center was in Jiangling sag of Dangyang area; and during the late Paleogene, the large scale deposition is controlled by the NNE and NE trending faults and the sedimentary center was located in Qianjiang sag which received large amounts of Paleogene sediments. Moreover, the study area is always located in uplift zone of the Jianghan fault basin during this period and there is no chance for large scale deposition and reheat event to happen from the late Cretaceous to the Paleogene stage.

If we assume that the Lower Jurassic strata has been eroded to the present condition during the Yanshanian tectonic period, the maximum thickness of the late Cretaceous-Paleocene sediments could be estimated by thermal modeling based on apatite fission track and (U-Th)/He. The analysis results show that when the thickness of the late Cretaceous-Paleogene sediments exceeds~1000 m, the temperature of the middle Jurassic would reheat to~80 ℃, causing all of the helium diffuse out from the crystal and the apatite (U-Th)/He age would all be reset. Meanwhile, the temperature of the upper Jurassic to the bottom of lower Jurassic would reheat to~100~120 ℃, the apatite fission track would be totally annealed and the age also be reset. So the conclusion that the maximum thickness of the late Cretaceous-Paleocene sediments deposited in the Paizhouwan area could not exceed~1000 m seems to be reasonable.

6 CONCLUSIONIn order to more clearly understand the tectonic and thermal history during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic stage of the Paizhouwan area in eastern Jianghan basin, fission track analysis, (U-Th)/He dating, vitrinite reflectance, thermal modeling and basin modeling are carried out, the conclusions are as follows:

(1) The apparent age from zircon fission track and (U-Th)/He age at the bottom of the upper Triassic of Well PS1 concentrate in 110–100 Ma, corresponding to the regional huge tectonic uplift cooling events happened during the early Cretaceous. The apparent apatite fission track ages of the upper Triassic to the Jurassic strata vary from 85 Ma to 54 Ma, with the confined fission track length ranging from 12.8 µm to 11.5 µm, and the apatite (U-Th)/He age is 74.2–33.5 Ma, which give evidence that the study area experienced tectonic uplift and cooling events since the late Cretaceous.

(2) The analysis results show that there should be enormous thickness of the middle-late Jurassic, even the early Cretaceous sediments deposition in the study area, and the thickness is~5000 m. The current thickness of these strata is thin, which is caused by the successive intense tectonic uplift and erosion events during the middle-late stage of the early Cretaceous to the late Cretaceous, with the total erosion thickness about 4300 m. The enormous tectonic uplift erosion and cooling event during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic stage began at the early Cretaceous (140–130 Ma); and the intense tectonic uplift-cooling process mainly occurred during the middle-late stage of the early Cretaceous to the late Cretaceous. While there may be some sedimentation of the late Cretaceous-Paleogene stage, the overall deposition thickness is relatively small.

(3) The Mesozoic strata in the study area reached the maximum paleo-temperature in the early Cretaceous, rather than at the end of Paleogene sedimentation, the maximum temperature of the bottom of the Upper Triassic is about 170~190 ℃, which reset the zircon fission track and (U-Th)/He age. The paleo-temperature gradient is 33.4~35.7 ℃·km−1 and 34.7 ℃·km−1 during the late Triassic to the early Cretaceous and in the late Cretaceous-Paleogene period. The thermal history results also show that the ancient heat flow is relatively stable during the Paleozoic stage, the average value is~53.64 mW·m−2; the heat flow began to decrease in the early Jurassic, and the lowest is about 48.38 mW·m−2 during the beginning of the early Cretaceous approximately.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThe authors are most grateful to Prof. A. Gleadow and Prof. B. Kohn in the Melbourne University, Prof. Yuan Wanming, China University of Geosciences (Beijing) for the help in experiments. We also thank Assistant Professor Fang Shi in Jilin University, Dr. Tian Yuntao, Zhong Ling, L. Raul and S. Himansu for their help. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (40739904, 41072093 and 41302117), the National Special Foundation of China (2011ZX05005-002), and the International Cooperation Project, Sinopec (Study on the standard sample of new method for fission track dating).

| [] | Armstrong P A. 2005. Thermochronometers in the sedimentary basins. Reviews in Mineralogy & Geochemistry , 58 (1) : 499-525. |

| [] | Bensley D F, Crelling J C. 1994. The inherent heterogeneity within the vitrinite naceral group. Fuel , 73 (8) : 1306-1316. DOI:10.1016/0016-2361(94)90306-9 |

| [] | Bernet M. 2009. A field-based estimate of the zircon fission-track closure temperature. Chemical Geology , 259 (3-4) : 181-189. DOI:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2008.10.043 |

| [] | Brandon M T, Roden-Tice M K, Garver J I. 1998. Late Cenozoic exhumation of the Cascadia accretionary wedge in the Olympic Mountains, northwest Washington State. GSA Bull. , 110 (8) : 985-1009. DOI:10.1130/0016-7606(1998)110<0985:LCEOTC>2.3.CO;2 |

| [] | Buiskool T J M A. 1983. Selection criteria for the use of vitrinite reflectance as a maturity tool.//Brooks J ed. Petroleum Geochemistry and Exploration of Europe. Oxford:Blackwell Scientific Publications. |

| [] | Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources of Hubei Province. 1990. Regional Geology of Hubei Province (in Chinese)[M]. Beijing: Geological Publishing House . |

| [] | Chen L, Ma C Q, Zhang J Y, et al. 2012. The first geological map of intrusive rocks in Dabie orogenic belt and its adjacent areas and its explanatory notes. Geological Bulletin of China (in Chinese) , 31 (1) : 13-19. |

| [] | Donelick R A, O'Sullivan P B, Ketcham R A. 2005. Apatite fission-track analysis. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. , 58 : 49-94. DOI:10.2138/rmg.2005.58.3 |

| [] | Editing Group of Ultrahigh-Pressure Metamorphism and Collisional Orogenic Dynamics. 2005. Ultrahigh-pressure metamorphism and collisional orogenic dynamics of Dabie Mountain (in Chinese)[M]. Beijing: Science Press . |

| [] | Farley K A, Wolf R A, Silver L T. 1996. The effects of long alpha-stopping distances on (U-Th)/He ages. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta , 60 (21) : 4223-4229. DOI:10.1016/S0016-7037(96)00193-7 |

| [] | Farley K A. 2000. Helium diffusion from apatite:General behavior as illustrated by Durango fluorapatite. J. Geophys. Res. , 105 (B2) : 2903-2914. DOI:10.1029/1999JB900348 |

| [] | Farley K A. 2002. (U-Th)/He dating:techniques, calibrations and applications.//Porcelli D, Ballentine C J, Wieler R. Noble Gases in Geochemistry and Cosmochemistry:Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 47(1):819-844. |

| [] | Faure M, Sun Y, Shu L, et al. 1996. Extensional tectonics within a subduction-type orogen, the case study of the Wugongshan dome (Jiangxi Province, southeastern China). Tectonophysics , 263 (1-4) : 77-106. DOI:10.1016/S0040-1951(97)81487-4 |

| [] | Gallagher K, Brown R, Johnson C. 1998. Fission track analysis and its application to geological problems. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. , 26 : 519-572. DOI:10.1146/annurev.earth.26.1.519 |

| [] | Garver J I, Bartholomew A. 2001. Partial resetting of fission tracks in detrital zircon:dating low temperature events in the Hudson Valley (NY). GSA Spec. Pap. , 33 (1) : 82. |

| [] | Gleadow A J W, Duddy I R, Lovering J F. 1983. Fission track analysis:A new tool for the evaluation of thermal histories and hydrocarbon potential. Austral. Petrol. Explor. Assoc. J. , 23 : 93-102. |

| [] | Gleadow A J W, Belton D X, Kohn B P, et al. 2002. Fission track dating of phosphate minerals and the thermochronology of apatite. Reviews in Mineralogy Geochemistry , 48 (1) : 579-630. DOI:10.2138/rmg.2002.48.16 |

| [] | Gleadow A J W, Duddy I R, Green P F, et al. 1986. Confined fission track length in apatite:a diagnostic tool for thermal history analysis. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology , 94 (4) : 405-415. DOI:10.1007/BF00376334 |

| [] | Gleadow A J W. 2010. Fission track dating:principles and techniques. Melbourne:School of Earth Sciences, the University of Melbourne. |

| [] | Green P F, Duddy I R, Gleadow A J W, et al. 1986. Thermal annealing of fission tracks in apatite:A qualitative description. Chem. Geol. , 59 : 237-253. DOI:10.1016/0168-9622(86)90074-6 |

| [] | Grimmer J C, Jonckheere R, Enkelmann E, et al. 2002. Cretaceous-Cenozoic history of the southern Tan-Lu fault zone:apatite fission-track and structural constraints from the Dabie Shan (eastern China). Tectonophysics , 359 : 225-253. DOI:10.1016/S0040-1951(02)00513-9 |

| [] | Guo T L, Li G X, Zeng Q L. 2005. Thermal history reconstruction for well Dangshen 3 in the Dangyang synclinorium, Jianghan basin and its exploration implications. Chinese Journal of Geology (in Chinese) , 40 (4) : 570-578. |

| [] | Hasebe N, Mori S, Tagami T, et al. 2003. Geological partial annealing zone of zircon fission-track system:additional constraints from the deep drilling MITI-Nishikubiki and MITI-Mishima. Chemical Geology , 199 : 45-52. DOI:10.1016/S0009-2541(03)00053-6 |

| [] | Hasebe N, Barbarand J, Jarvis K, et al. 2004. Apatite fission-track chronometry using laser ablation ICP-MS. Chemical Geology , 207 (3-4) : 135-145. DOI:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2004.01.007 |

| [] | He S, Wang Q L. 1989. The eroded thickness reconstructed by vitrinite reflectance. Geological Review (in Chinese) , 35 (2) : 119-126. |

| [] | He S, Middleton M. 2002. Heat flow and thermal maturity modelling in the Northern Carnarvon Basin, North West Shelf, Australia. Marine and Petroleum Geology , 19 (9) : 1073-1088. DOI:10.1016/S0264-8172(03)00003-5 |

| [] | Hu S B, Raza A, Min K, et al. 2006a. Late Mesozoic and Cenozoic thermotectonic evolution along a transect from the north China craton through the Qinling orogeny into the Yangtze craton, central China. Tectonics , 25 (6) : TC6009. DOI:10.1029/2006TC001985 |

| [] | Hu S B, Kohn B P, Raza A, et al. 2006b. Cretaceous and Cenozoic cooling history across the ultrahigh pressure Tongbai-Dabie belt, central China, from apatite fission-track thermochronology. Tectonophysics , 420 (3-4) : 409-429. DOI:10.1016/j.tecto.2006.03.027 |

| [] | Hunt J M. 1979. Petroleum Geochemistry and Geology. San Francisco:Freeman W M. |

| [] | Hurford A J, Green P F. 1982. A users' guide to fission-track dating calibration. Earth and Planetary Science Letters , 59 (2) : 343-354. DOI:10.1016/0012-821X(82)90136-4 |

| [] | Hurford A J, Green P F. 1983. The zeta age calibration of fission track dating. Chemical Geology , 41 : 285-317. DOI:10.1016/S0009-2541(83)80026-6 |

| [] | Ketcham R A, Donelick R A, CarlsonWD. 1999. Variability of apatite fission-track annealing kinetics:Ⅲ. Extrapolation to geological time scales. Am Mineral , 84 (9) : 1235-1255. |

| [] | Ketcham R A, Carter A, Donelick R A, et al. 2007. Improved modeling of fission-track annealing in apatite. American Mineralogist , 92 (5-6) : 799-810. DOI:10.2138/am.2007.2281 |

| [] | Kohn B P, Gleadow A J W, Brown R W, et al. 2005. Visualising thermotectonic and denudation histories using apatite fission track thermochronology. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry , 58 (1) : 527-565. DOI:10.2138/rmg.2005.58.20 |

| [] | Li T Y, He S, He Z L, et al. 2012. Reconstruction of tectonic uplift and thermal history since Mesozoic in the Dangyang synclinorium of the central Yangtze area. Acta Petrolei Sinica (in Chinese) , 33 (2) : 213-224. |

| [] | Li S G, Xiao Y L, Liou D L, et al. 1993. Collision of the north China and Yangtze blocks and formation of coesite-bearing eclogites:Timing and processes. Chem. Geol. , 109 (1-4) : 89-111. DOI:10.1016/0009-2541(93)90063-O |

| [] | Liu S F, Steel R, Zhang G W. 2005. Mesozoic sedimentary basin development and tectonic implication, northern Yangtze Block, eastern China:record of continent-continent collision. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences , 25 (1) : 9-27. DOI:10.1016/j.jseaes.2004.01.010 |

| [] | Liu S F, Wang P, Hu M Q, et al. 2010. Evolution and geodynamic mechanism of basin-mountain systems in the northern margin of the Middle-Upper Yangtze. Earth Sciences Frontiers , 17 (3) : 14-26. |

| [] | Liu Y L, Shen Z M, Ding D G, et al. 2008. The characters of the old asphalt-oil pool in the Jiangnan-Xuefeng thrust nappe front and the correlation of oil sources. Journal of Chengdu University of Technology , 35 (1) : 34-40. |

| [] | Ma L, Chen H J, Lu K W. 2004. The Regional Structure and Marine Petroleum Geology in South China (in Chinese)[M]. Beijing: Geological Pubilishing House . |

| [] | Ma Y S. 2007. China Marine Petroleum Exploration (in Chinese)[M]. Beijing: Geological Pubilishing House . |

| [] | Mei L F, Fei Q. 1992. Oil-gas show of marine strata in Central Yangtze region and its significance in petroleum geology. Oil and Gas Geology (in Chinese) , 13 (2) : 155-166. |

| [] | Meng Q R, Zhang G W. 1999. Timing of collision of the north and south China blocks:Controversy and reconciliation. Geology , 27 (2) : 123-126. DOI:10.1130/0091-7613(1999)027<0123:TOCOTN>2.3.CO;2 |

| [] | Peters K E, Cunningham A E, Walters C C, et al. 1996. Petroleum systems in the Jiangling-Dangyang area, Jianghan Basin, China. Organic Geochemistry , 24 (10-11) : 1035-2060. DOI:10.1016/S0146-6380(96)00080-0 |

| [] | Qiu N S, Reiners P, Mei Q H, et al. 2009. Application of the (U-Th)/He thermochromometry to the tectonics-thermal evolution of sedimentary basin-A case history of well KQ1 in the Tarim Basin. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 52 (7) : 1825-1835. |

| [] | Qiu N S, Hu S B, He L J. 2004. Theory and Application of the Research on Heat State of the Sedmentary Basin (in Chinese)[M]. Beijing: Petroleum Industry Press . |

| [] | Reiners P W, Spell T L, Nicolescu S, et al. 2004. Zircon (U-Th)/He thermochronometry:He diffusion and comparisons with 40Ar/39Ar dating. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta , 68 (8) : 1857-1887. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2003.10.021 |

| [] | Suzuki N, Matsubayashi H, Waples D W. 1993. A simpler kinetic model of vitrinite reflectance. AAPG Bulletin , 77 (9) : 1502-1508. |

| [] | Tagami T, Shimada C. 1996. Natural long-term annealing of the zircon fission track system around a granitic pluton. J. Geophys. Res. , 101 (B4) : 8245-8255. DOI:10.1029/95JB02885 |

| [] | Tian Y T, Zhu C Q, Xu M, et al. 2011. Post-Early Cretaceous denudation history of the northeastern Sichuan Basin:constraints from low-temperature thermochronology profiles. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 54 (3) : 807-816. |

| [] | The Petroleum Geology Editor of Jianghan Oil Field. 1991. Petroleum Geology of China Vol[M]. Beijing: Petroleum Industry Press . |

| [] | Wang J A, Xiong L P, Yang S Z. 1985. Geothermal and Petroleum (in Chinese)[M]. Beijing: Science Press . |

| [] | Wang S H, Luo K P, Liu G X. 2009. Fission track records of tectonic uplift during the Cenozoic and Mesozoic in the periphery of the Jianghan Basin. Oil and Gas Geology (in Chinese) , 30 (3) : 255-259. |

| [] | Waples D W, Kamata H, Suizu M. 1992a. The art of maturity modeling. Part 1:finding a satisfactory geologic model. AAPG Bulletin , 76 (1) : 31-46. |

| [] | Waples D W, Suizu M, Kamata H. 1992b. The art of maturity modeling. Part 2:alternative models and sensitivity analysis. AAPG Bulletin , 76 (1) : 47-66. |

| [] | Wilkins R W T, Wilmshurst J R, Russel N J, et al. 1992. Fluorescence alteration and the suppression of vitrinite reflectance. Org. Geochem. , 18 (5) : 629-640. DOI:10.1016/0146-6380(92)90088-F |

| [] | Xu C H, Zhou Z Y, Ma C Q, et al. 2001. Thermal doming extension in 140~85 Ma of the Dabie Orogenic belt:constraints from chronology. Science in China (Series D) (in Chinese) , 31 (11) : 925-937. |

| [] | Xu M, Zhao P, Zhu C Q, et al. 2010. Borehole temperature logging and terrestrial heat flow distribution in Jianghan Basin. Chinese Journal of Geosciences (in Chinese) , 45 (1) : 317-323. |

| [] | Yamada R, Tagami T, Nishimura S, et al. 1995. Annealing kinetics of fission tracks in zircon:an experimental study. Chemical Geology , 122 (1-4) : 249-258. DOI:10.1016/0009-2541(95)00006-8 |

| [] | Yuan W M, Du Y S, Yang L Q, et al. 2007. Apatit fission track studies on the tectonics in Nanmulin area of Gangdese terrane, Tibet plateau. Acta Petrologica Sinica (in Chinese) , 23 (11) : 2911-2917. |

| [] | Zeitler P K, Herczig A L, McDougall I, et al. 1987. U-Th-He dating of apatite:a potential thermochronometer. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta , 51 (10) : 2865-2868. DOI:10.1016/0016-7037(87)90164-5 |

| [] | Zheng D W, Zhang P Z, Wan J L, et al. 2005. Apatite fission track evidence for the thermal history of the Liupanshan basin. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese) , 48 (1) : 157-164. |

| [] | Zhou Y, Hu C X. 1996. A study of structural character during early Yanshan period in Jianghan basin. Acta Geoscientia Sinica (in Chinese) , 20 (S1) : 92-96. |

| [] | Zhou Z Y, Xu C H, Reiners P W, et al. 2003. The exhumation history since the Late Cretaceous of Tiantangzhai area, Dabie Mountain:evidences from (U-Th)/He and fission track. Chinese Science Bulletin (in Chinese) , 48 (6) : 598-602. |

| [] | Zhu G, Niu M L, Liu G S, et al. 2005. 40Ar/39Ar dating for the strike-slip movement on the Feidong part of the Tan-Lu fault belt. Acta Geologica Sinica (in Chinese) , 79 (3) : 303-316. |

2015, Vol. 58

2015, Vol. 58