2. Research Center for Basin and Reservoir, China University of Petroleum, Beijing 102249, China;

3. Wuxi Research Institute of Petroleum Geology, SINOPEC, Wuxi Jiangsu 214151, China

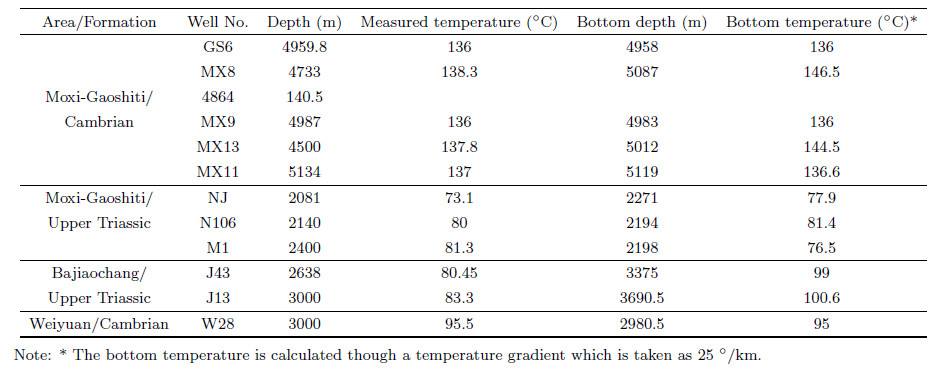

The Sichuan Basin, which was developed on a pre-Sinian basement, has experienced complicated tectonic and sedimentary evolution history. The evolution of Sichuan Basin can be mainly divided into two periods, a craton basin stage and a forel and basin stage. Marine carbonate rocks were deposited dominantly in the basin during the craton period and thick terrestrial clastic rocks were deposited during the forel and basin stage. Because of multi-period tectonic movements, some strata are absent and correspondingly several unconformities were developed in the basin. Especially, Jurassic and even underlying formations have been exposed on the surface due to the tectonic uplift since the Cretaceous(Deng et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2012). The Central Paleo-Uplift, located in the middle of the Sichuan Basin(Fig. 1), is a part of the Leshan-Longn¨usi nose structure. This area was a rise region during the Caledonian epoch and became a north-dipping slope from the Indosinian to the Yanshan movements(Wang et al., 1989; Xu et al., 2012). Nowadays, the structure is higher in the eastern part and plunging to the west successively. As a large ancient successively developing positive structure, the Central Paleo-Uplift of the Sichuan Basin has great prospective for oil and gas exploration(Yao et al., 2003; Wei et al., 2010). Many commercial oil and gas reservoirs so far have been proved in the Sinian, Cambrian, Triassic and Jurassic formations.

|

Fig.1 (a) Gas fields distribution and locations of the section and wells; (b) A seismic section in the study area (Xu et al., 2012) |

Many researches on pore pressures in the Sichuan Basin have been carried out and overpressures have been detected in many formations from the Lower Cambrian Formation to the Upper Triassic Formation(Yang et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2008; Xie et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2009; Hao et al., 2010). Based on the measurements from drilling holes, the pressure coefficient of the Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation in the Central Paleo-Uplift is in the range of 1.0 to 2.0 and decreases gradually from the northwest to the south(Xie et al., 2009; Hao et al., 2010). The pressure coefficient of Lower Triassic Jialingjiang Formation in Moxi-Longn¨usi tectonic belt is over 2.0(Xu et al., 2009). Sinian Formation in the central part of Sichuan Basin is mainly manifested as normal pressure or low overpressure characteristics, but Cambrian-Ordovician formations are significantly overpressured with pressure coefficient ranging from 1.0 to 1.82(Liu et al., 2008). Heat flow of this basin experienced multiphase evolution(Qiu et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011; He et al., 2014). Combining the heat flow with burial history, the temperature of formations in the Sichuan Basin has experienced a complex and great change. Geothermal field has significant impact on generation and preservation of overpressures, but such research is relatively absent in China. Temperature increase as a potential mechanism for overpressure has been realized for years(Barker, 1972). However, some authors suggest that aquathermal is not a main mechanism for overpressure because absolutely zero permeability seals may not exist and only small volume expansion can be caused by temperature increase(Luo and Vasseur, 1992; Osborne and Swarbrick, 1997). General mechanisms for overpressure, such as disequilibrium compaction, hydrocarbon generation and smectite, kaolinite or gypsum diagenesis, could be ceased during tectonic uplift. The existence of abnormal pressures in old basins which have undergone uplift and erosion for millions of years could demonstrate the effectiveness of seals. In this case, the influence of temperature on the pressure cannot be ignored. For instance, underpressures in the Ordos Basin are closely related to fall of temperature caused by tectonic uplift(Xu et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013). The Sichuan Basin has experienced a basin scale great uplift since the Cretaceous and the maximum denudation thickness is more than 4000 m(Deng et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2012). The relative research on the impacts of temperature decrease on the overpressure in the basin is short and dem and s to supplement. In this paper, the relationship between temperature and pressure for overpressured formations is clarified according to the measurements from drill holes. The role of temperature on controlling the pore pressure is studied based on physical simulation experiment. Combining with the temperature history, the effects of temperature on overpressures generation and distribution in the Central Paleo-Uplift in the Sichuan Basin are analyzed.

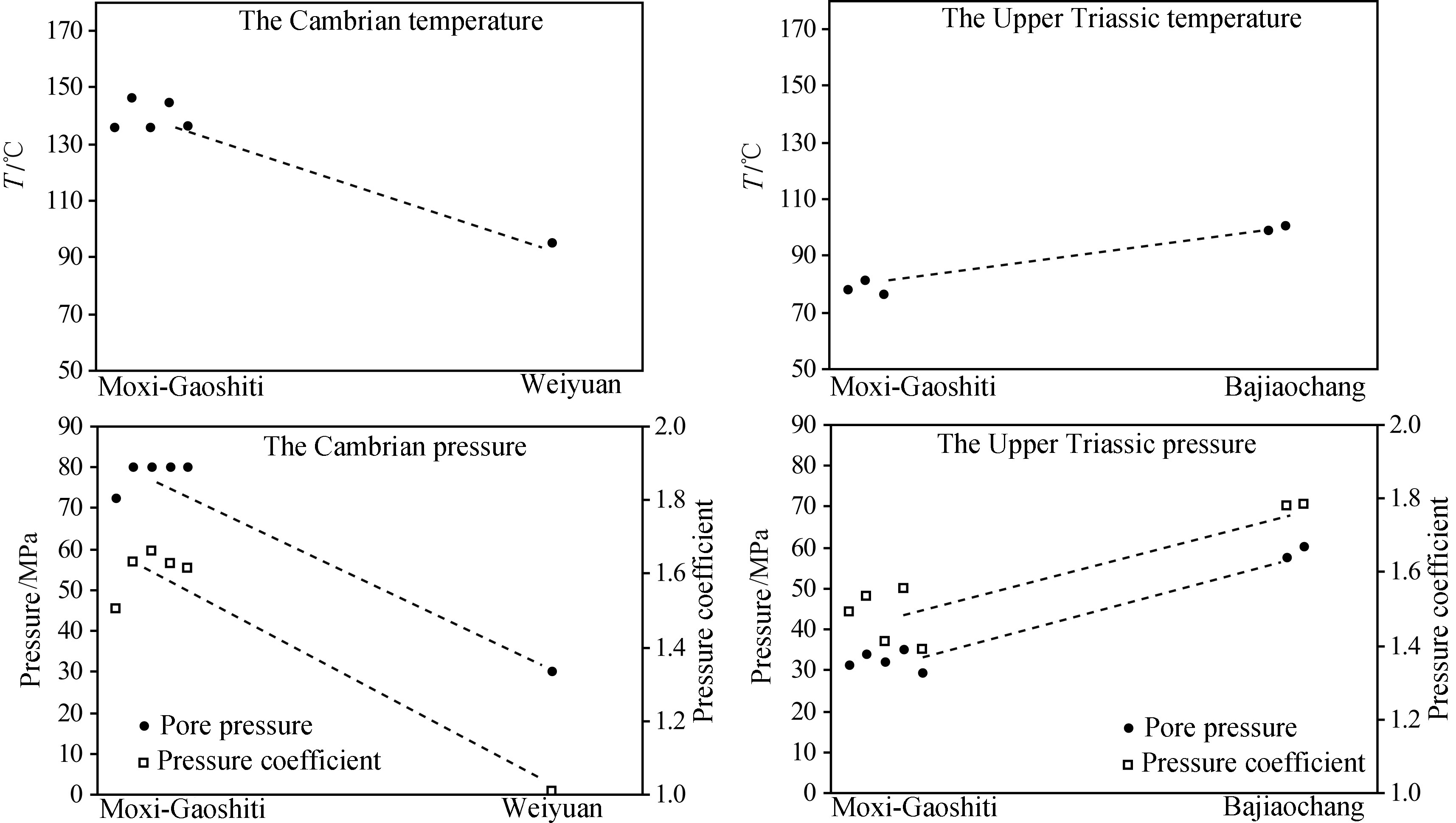

2 PRESENT FORMATION TEMPERATURE AND PRESSURE 2.1 Characteristics of Present Temperature FieldBased on bore holes temperature data, a lot of measured rock thermal conductivity and heat generation rate, a general knowledge on present temperature distribution characteristics of Sichuan Basin has been obtained(Xie and Yu, 1998; Han and Wu, 1993; Lu et al. 2005; Xu et al., 2011). The average heat flow of the Sichuan Basin is 53.2 mW·m-2 which is lower than the average value on l and of China(63 mW·m-2), but slightly higher than the average heat flows in Tarim Basin and Junggar Basin. Present geothermal gradient of Sichuan Basin is 17.7~33.4 ℃/km. Due to relatively shallow depth of basement, the heat flow(60~70 mW·m-2) and geothermal gradient(24~30 ℃/km)in the central and southern parts of Sichuan Basin are significantly higher than those in northeastern and northwestern parts(Xu et al., 2011). Temperature data is further enriched with more deep wells drilled in the Central Paleo-Uplift of Sichuan Basin. We collected temperatures in typical wells from Weiyuan, Moxi-Gaoshiti, and Bajiaochang areas(Table 1). The temperature data are distributed in the Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation, Cambrian Longwangmiao and Xixiangchi formations, which are main gas production layers. In order to remove the difference of measuring depths, all temperatures were corrected to the bottom interface of formations. In the lateral direction, temperatures for the same formation are quite different, as they are controlled by burial depth. Temperature for the bottom interface of Cambrian Formation is 136~146.5 ℃ in Moxi-Gaoshiti area, but is just about 95 ℃ in Weiyuan area. Temperature of the Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation bottom is 76.5~81.4 ℃ in Moxi-Gaoshiti area, gradually increasing to the northwest, and the temperature is about 100 ℃ in Bajiaochang area.

| Table 1 Temperature data from bore holes in different position of the Central Paleo-Uplift in the Sichuan Basin |

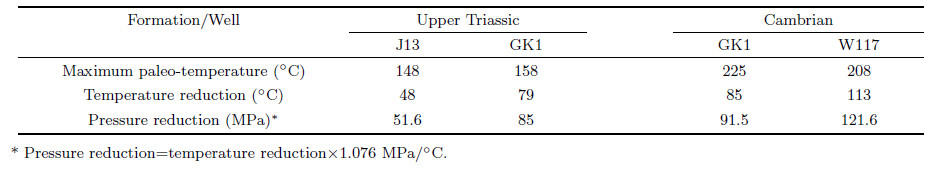

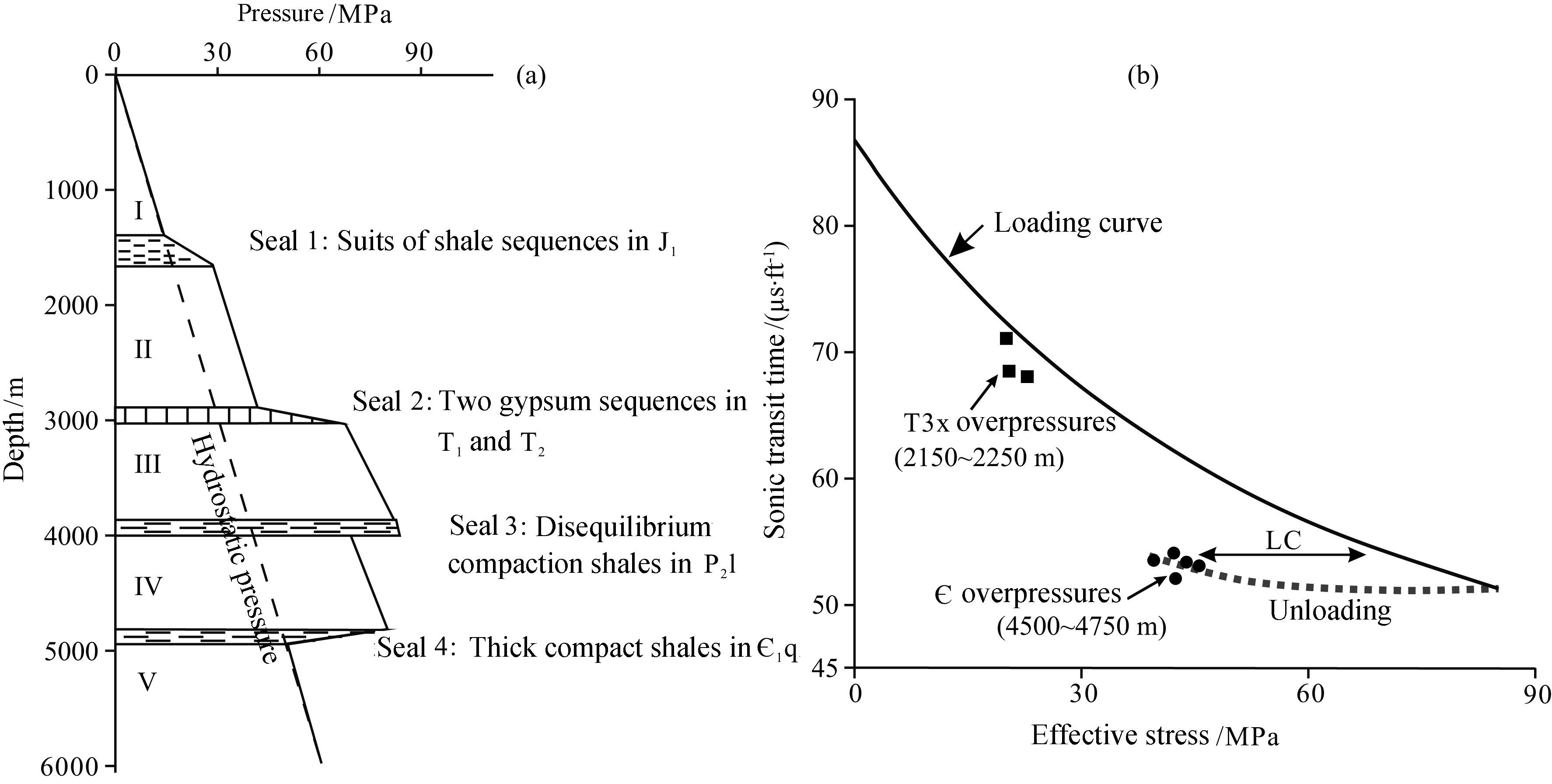

The Sichuan Basin is a typical overpressuring basin and many researches on the distribution and mechanisms for overpressures in this basin have been reported(Wang et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2008; Tian et al., 2008; Hao et al., 2010; Guo et al., 2012). Pore pressures for Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation, Lower Triassic Jialingjiang Formation, Cambrian Formation and residual Ordovician Formation are significantly higher than the hydrostatic pressure. Although there is no measured pressure in the Upper Permian Longtan Formation, obviously abnormal mudstone sonic transit time also implies the existence of overpressure. Combining the measurements, drilling mud weight and acoustic logging data with fluid characteristics and cap rocks distribution, several pressure systems can be identified in the Moxi-Gaoshiti area. Overpressures are developed in the depth of 2000 to 5000 m. Based on petrophysical properties, the Upper Triassic Xujiahe overpressure and the Upper Permian overpressure are primarily generated by disequilibrium compaction, and overpressures in the Lower Triassic and the Lower Paleozoic are recognized to be fluid expansion overpressures caused by gas generation(Fig. 2). Laterally, the Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation is normally pressured in the southwest of Guang’an- Tongliang, but overpressures gradually increase to the northwest and the pressure coefficient reaches 1.9 in the Bajiaochang area(Hao et al., 2010). In the Cambrian Formation, pore pressures are normal in the Weiyuan area and overpressures, with pressure coefficient ranging from 1.48 to 1.78, are detected in the Moxi-Gaoshiti area(Liu et al., 2008).

|

Fig.2 (a) Overpressure systems in the Moxi-Gaoshiti area; (b) Mechanisms for the Cambrian and Xujiahe overpressures: the Xujiahe Formation overpressure is caused by disequilibrium compaction and the Cambrian overpressure is mainly caused by fluid expansion |

Temperature and pore pressure are two important physical fields in sedimentary basins, and the relationship of these two parameters is the focus of academic attention. Temperature-pressure relationship for the Cambrian and the Upper Triassic Xujiahe overpressured formations are studied in this article. Measured temperature and pressure data of the Cambrian Formation are collected from the Moxi-Gaoshiti and Weiyuan areas and the data of the Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation are collected from Moxi-Gaoshiti and Bajiaochang areas, respectively(Fig. 3). In the Moxi-Gaoshiti area, the average temperature and pressure are respectively 140 ℃ and 78.5MPa, and 95 ℃ and 30.1 MPa for the Cambrian Formation in the Weiyuan area(Well W28). The change rate of pressure with respect to the temperature is 1.075 MPa/℃. Temperatures of the Xujiahe Formation are 78.5 ℃ in the Moxi-Gaoshiti area and 100 ℃ in the Bajiaochang area and corresponding pore pressures in these two areas are 32.3 MPa and 59 MPa. The slope of temperature-pressure for the Xujiahe Formation between the Moxi-Gaoshiti and Bajiaochang areas is 1.24 MPa/℃. In summary, pressure and pressure coefficient of the Cambrian and the Upper Triassic Xujiahe formations in the central part of Sichuan Basin have positive correlations with temperature. Pore pressure and pressure coefficient changes greater with temperature in the Xujiahe Formation than the relation in the Cambrian Formation.

|

Fig.3 Temperature and pressure characteristics of the bottom of the Cambrian Longwangmiao formation and the Upper Triassic Xujiahe formation in the Central Paleo-Uplift of the Sichuan Basin |

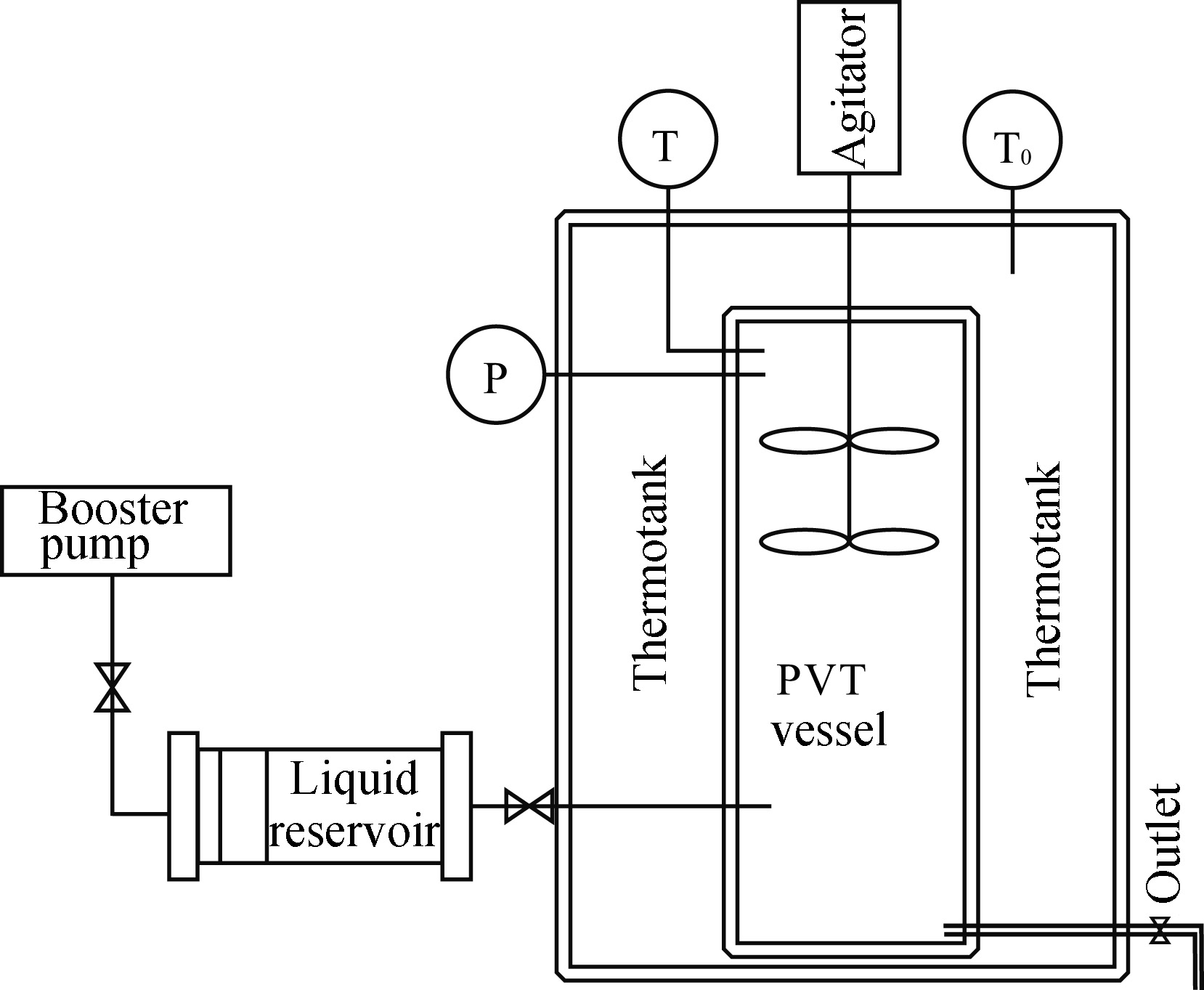

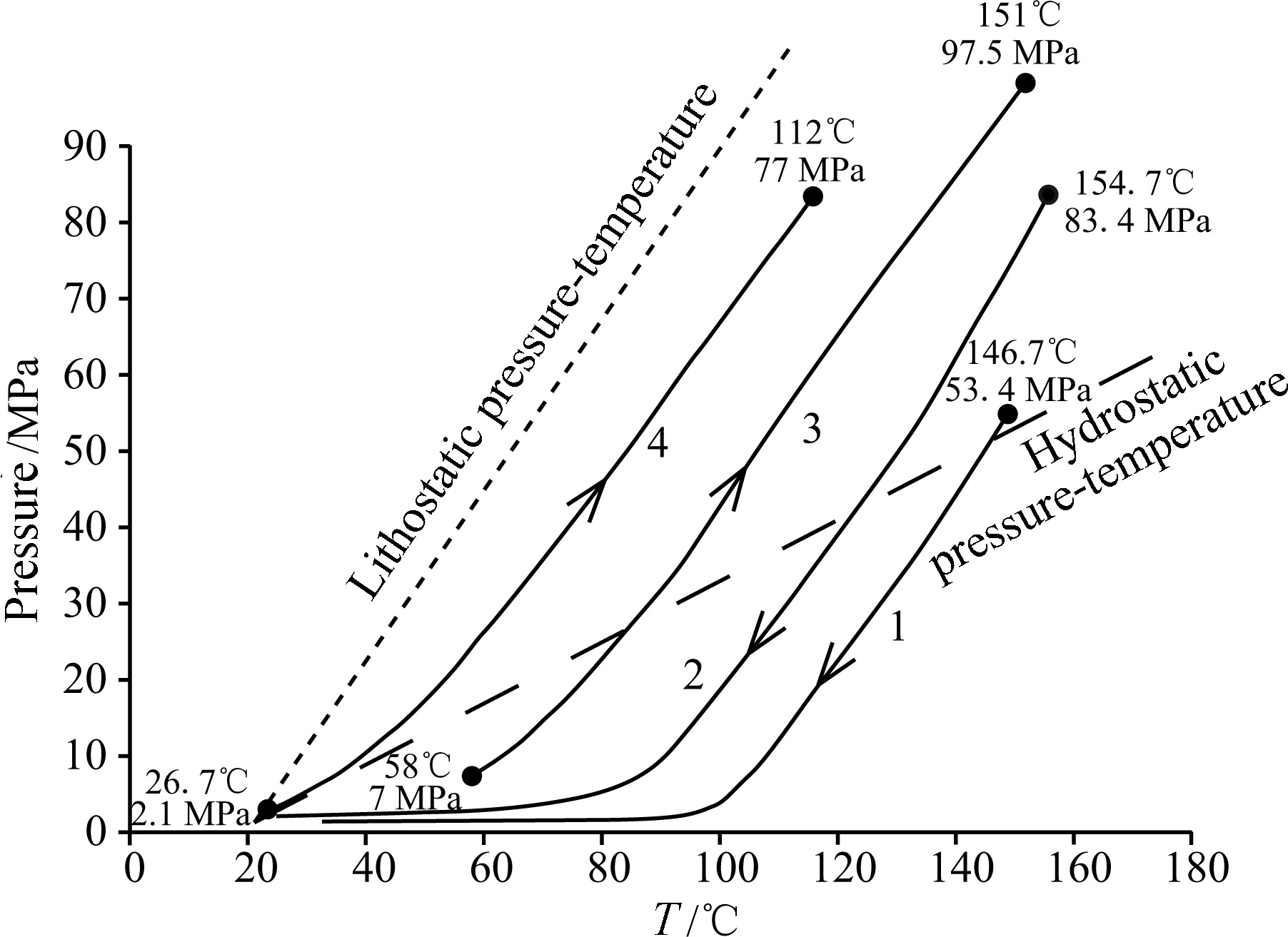

High-quality seal is the precondition for abnormal pressure generation in basins. Physical simulation experiments were carried out to study the temperature-pressure relationship in absolutely sealed condition. Experiment instrument is shown in Fig. 4. The “PVT Vessel”, which is a high temperature and pressure resistant container with a volume of about 250 mL, is the main structure of the instrument. Temperature in the “PVT Vessel” can be altered by the heater installed in the thermostat. Temperature and pressure are monitored by thermometer and pressure meter and recorded automatically through computer software. The constant pressure booster pump is used to inject water into the vessel, but also control the initial pressure in the “PVT Vessel”. The agitator could shorten the equilibrium time. To ensure temperatures and pressures are measured in equilibrium state which represent the real values in the vessel, temperatures were changed slowly with a rate of 5 ℃/hour. Formation water from the Eocene Shahejie Formation in the Sinopec Shengli Oilfield was selected to be the inject fluid and four groups of experiments with different initial temperatures and pressures were completed(Fig. 5). Firstly, groups 1 and 2 were processed by cooling from high temperatures and groups 3 and 4 were heated from low temperatures. When temperatures in the vessel reached the expected values, temperatures for all groups were changed reversely and returned to the initial values ultimately. With the reverse temperature change process, pressures as well returned to the initial state along the change tracks in previous phase.

|

Fig.4 Schematic diagram of the instrument for the temperature-pressure physical simulation experiment. Temperatures in the “PVT Vessel” and the thermotank are monitored by thermometers T and T0; pressure in the “PVT Vessel” is monitored by the pressure meter (P) |

|

Fig.5 Results of the temperature-pressure relationship physic simulation experiment. Two dashed lines represent temperature-lithostatic pressure and temperature-hydrostatic pressure relations respectively |

Experiment results show that relations of temperature-pressure in a sealing system are almost linearity with a slope of 1.076 MPa/℃ when pressures are higher than 15 MPa. In lower pressure state(< 15 MPa), pressures change more slowly with temperature changing(Fig. 5). The thermal expansion difference of water is the main reason for the different temperature-pressure relationships. In an absolutely sealing system, the change of pressure caused by temperature changing with burial or uplift is much larger than change of hydrostatic pressure with the same depth and just slightly smaller than the lithostatic change(Fig. 5).

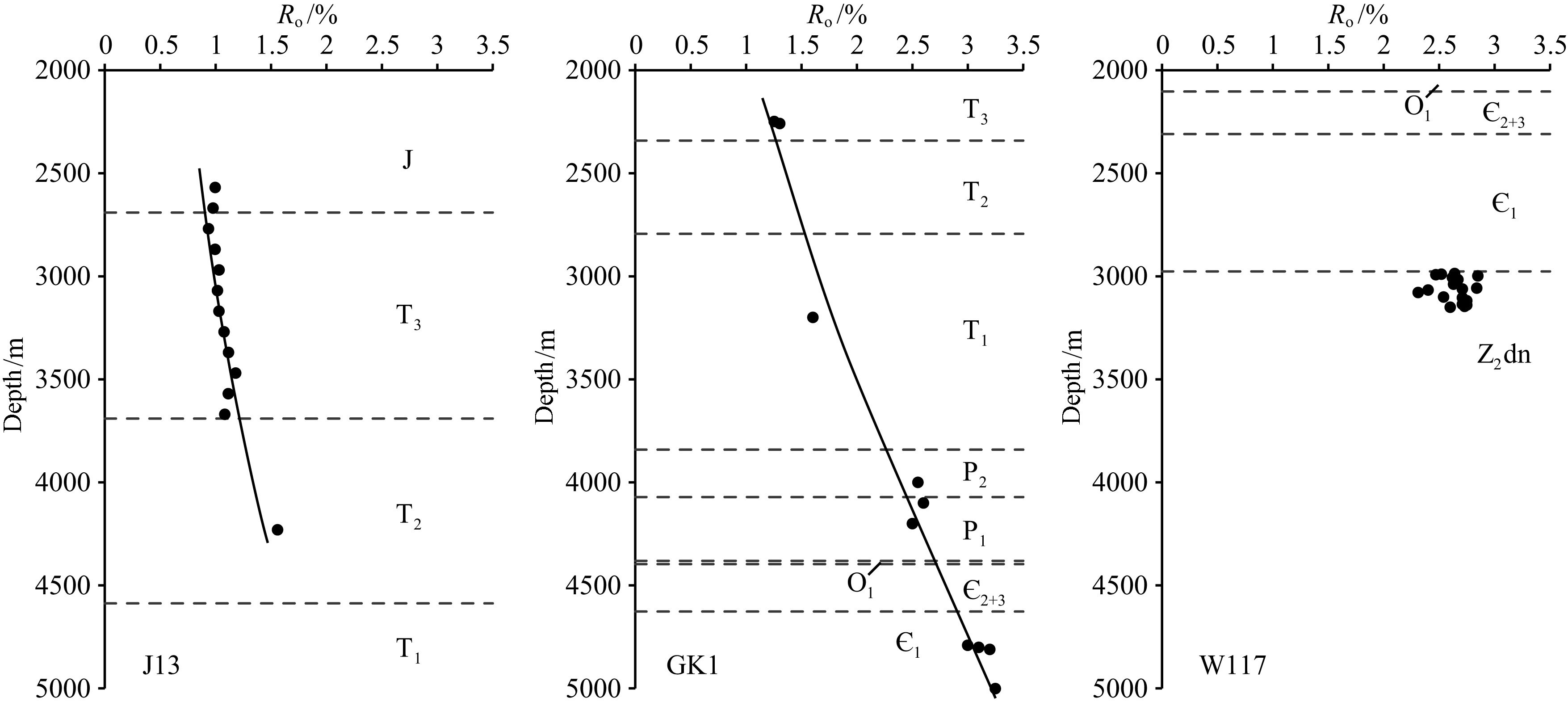

4 THE EFFECT OF TEMPERATURE ON OVERPRESSURE DISTRIBUTION IN THE CENTRAL PALEO-UPLIFT 4.1 The Effect of Late Cooling on the Overpressure DistributionTemperatures of formations in the Sichuan Basin reached the maximum before the uplift since the Late Cretaceous. Equivalent vitrinite reflectance(Requ), which is measured directly through vitrinite or converted from bitumen or vitrinite like maceral reflectance, is a commonly used indicator for thermal history reconstruction in sedimentary basins(Qiu et al., 2004). Maturity of organic matter has advantages to reconstruct the maximum temperature of strata experienced in the geological history. The Requ cross-sections of three typical wells in different regions in the Central Paleo-Uplift of the Sichuan Basin are shown in Fig. 6. Burial depths of formations are deepest in the Bajiaochang area, middle in the Moxi-Gaoshiti area, and shallowest in the Weiyuan area where the depth of the Cambrian Formation is just less than 3000 m. Formations fluctuation in the Central Paleo-Uplift is mainly caused by the differences of uplift and erosion in this area since the Late Cretaceous. Measured Requ in the Mesozoic and Paleozoic formations is in the range of 0.99%~3.25%.

|

Fig.6 Ro vs. depth plot for three wells in the Central Paleo-Uplift of the Sichuan Basin (well locations are shown in Fig. 1) |

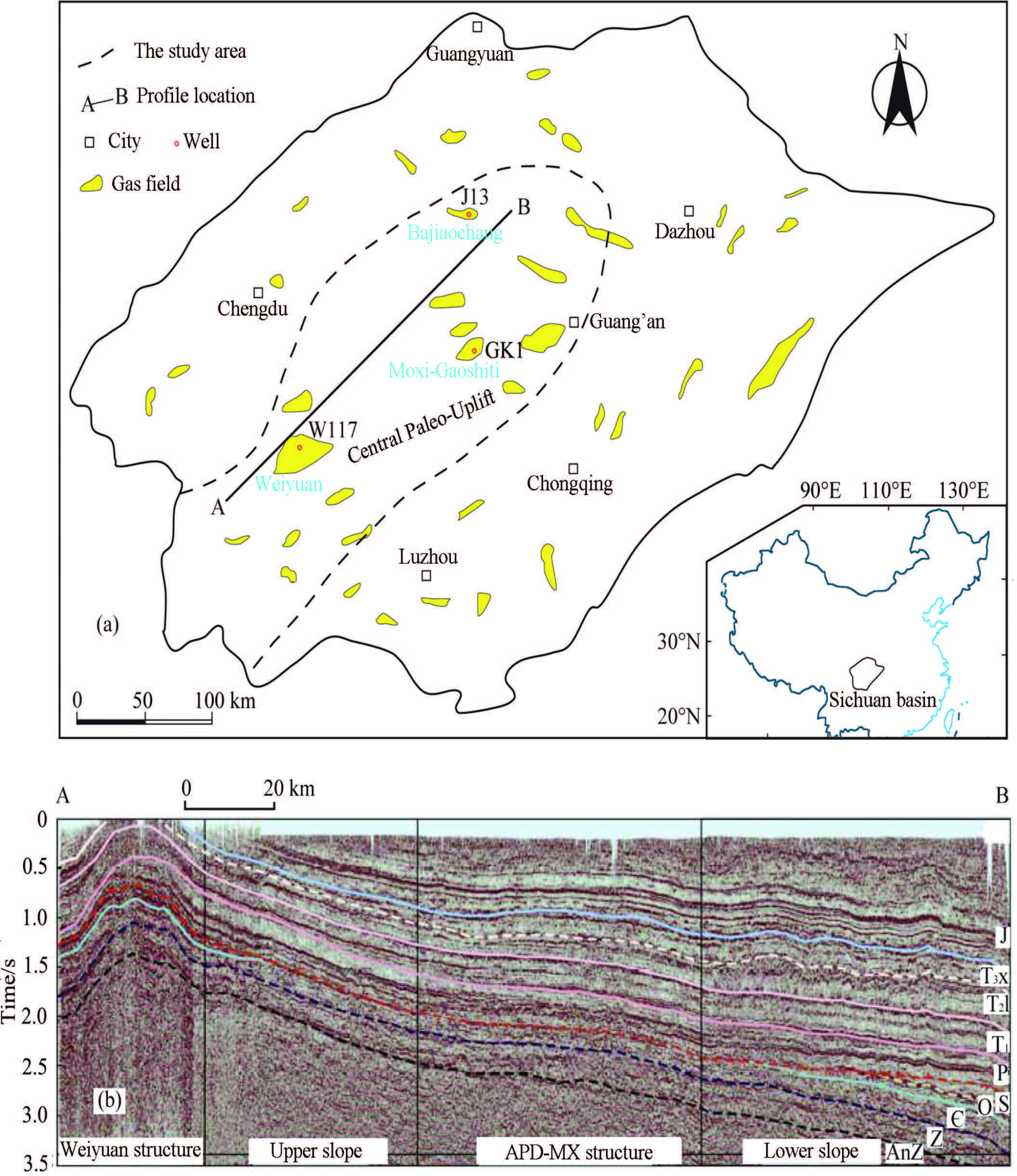

Based on parallel chemical reaction model(Easy%Ro), the maximum paleo-temperatures were reconstructed from Requ(see Table 2). The maximum paleo-temperature of the Triassic Formation is higher in the Moxi-Gaoshiti area than that in the Bajiaochang area; and the maximum paleo-temperature of the Cambrian Formation is higher in the Moxi-Gaoshiti area than that in the Weiyuan area. Compared with the present temperature, the temperature reduction caused by the Later Cretaceous uplift was calculated. And then, we could obtain the magnitude of pressure decrease caused by temperature reduction, according to the physical simulation experiment results(Table 2). The pressure reduction of the Xujiahe Formation, caused by temperature decrease, is 33.4 MPa greater in the Moxi-Gaoshiti area than that in the Bajiaochang area. And 30.1 MPa greater reduction of the Cambrian Formation overpressure in the Moxi-Gaoshiti area than that in the Weiyuan area. Hence, temperature decrease could be the main reason for distribution distinction of each pressure systems in the Central Paleo-Uplift.

| Table 2 Temperature reduction and the corresponding pressure decrease for T3 and ∈ in different wells in the Central Paleo-Uplift of the Sichuan Basin |

It is noteworthy that the pressure difference caused by temperature decrease(33.4 MPa)is higher than the real value in present(~27 MPa)for the Xujiahe Formation between the Bajiaochang area and Moxi-Gaoshiti area; and that(30.1 MPa)is relatively lower than the real value(~48 MPa)for the Cambrian Formation between the Weiyuan area and Moxi-Gaoshiti area. Because burial depths before the uplift are almost same, with just some little temperature difference for each formation, the pressures in each system should be approximately equal in various regions by that time. The smaller practical pressure difference in the Xujiahe Formation indicates that fluid or overpressure has transferred laterally within the clastic strata. Intensive denudation occurred in the Weiyuan area, where the Cambrian Formation is lower than 3000 m, and leakage of overpressure may occur because of seals damage. Pressures of Cambrian Formation in the Weiyuan area are hydrostatic in present. Between the Weiyuan area and the Moxi-Gaoshiti area, the actual difference of Cambrian pressures is greater than the difference that just considered with temperature change.

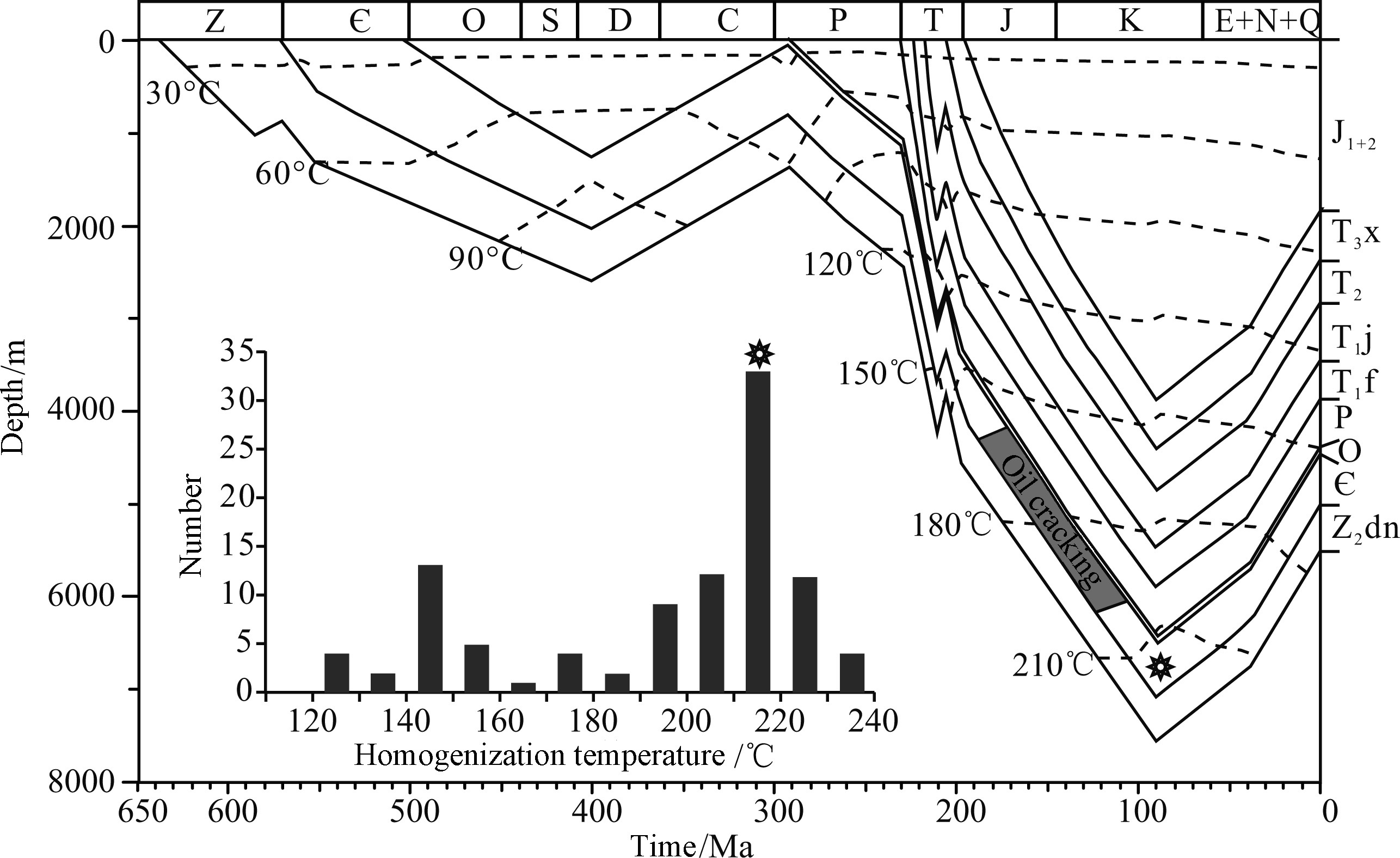

4.2 Effect of Temperature on Pressuring Caused by Hydrocarbon GenerationTemperature controls unloading of overpressure during uplift, but also has significant influences on overpressure generation. Hydrocarbon generation, especially oil cracking, is regarded as an important mechanism for the Lower Paleozoic overpressure system in the Sichuan Basin, which mainly consists of marine carbonate rocks. Temperature is the key factor for hydrocarbon generation and controls the maturity evolution of organic matters. Based on the reconstructed thermal history, the period of hydrocarbon generation could be determined and then the overpressure caused by gas generation can be dated as well. Various geothermometers(Qiu et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2010; Tian et al., 2011; Wang Wei et al., 2011) and tectonic-thermal modeling method(He et al., 2011, 2014; Huang et al., 2012)have been used to reconstruct the thermal history of the Sichuan Basin. The basin was in a stable thermal state with heat flow of basement ranging from 52 to 59 mW·m-2 during the early Paleozoic(He et al., 2014). Influenced by the regional lithosphere extension and Emeishan basalt mantle plume activity, the heat flow in the Central Paleo-Uplift increased to 60~80 mW·m-2 during then Permian, and then decreased to 50~60 mW·m-2 in the Late Triassic(Zhu et al., 2010; He et al., 2011). The heat flow was stable or slightly decreased since the Triassic. The oil cracking temperature is mainly in the range of 160~200 ℃(Jack′son et al., 1995; Waples, 2000). According to the Cambrian temperature history(Fig. 7), it can be determined that the early oil in the Cambrian reservoirs cracked to gas from the Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous(180~110 Ma)in Moxi-Gaoshiti area. Abundant gaseous inclusions and associated aqueous inclusions were observed within the calcite filled fractures in the Lower Paleozoic reservoirs of the Moxi-Gaoshiti area. Microthermometry of the associated aqueous inclusions reveals that gas migration and accumulation occurred when temperature was 210~230 ℃(Fig. 7), which is later than the time of oil cracking. In summary, the Cambrian overpressure began to generate in 180~110 Ma, and adjusted with gas accumulation before the uplift since the early Cretaceous(~90 Ma).

|

Fig.7 Burial history and the time of oil cracking for Well GK1 and the homogenization temperature of aqueous inclusions associated with hydrocarbon inclusions from the Lower Paleozoic in the Moxi-Gaoshiti area |

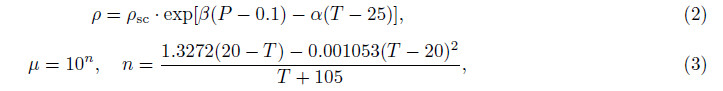

Disequilibrium compaction is another important mechanism for overpressure generation. Porosity of shales decreases rapidly during burial and overpressure could be generated by restriction of fluid expulsion and transfer of overburden to the fluid pressure. The overpressure caused by disequilibrium compaction increases with burial depth increasing. Fluid flow in the subsurface follows Darcy Law:

and

where v is fluid velocity in m/s, K is permeability in m2, μ is viscosity in MPa·s, dh/dl is pressure gradient inMPa/m, ρ and ρsc are density of underground water and surface water respectively in kg·m-3, T is temperaturein ℃, α = 5 × 10-4℃-1, β = 4.3 × 10-4 MPa-1.

Both density and viscosity of formation water calculated from Eqs.(2) and (3)would decrease with temperatureincreasing, and which is more significant for viscosity. Hence, if permeability and hydraulic gradientdo not change, the fluid velocity would be increased by temperature increasing and disequilibrium compactionoverpressure would be weakened. However, the permeability, which is extremely low during disequilibrium compaction, is the decisive factor for velocity and overpressure generation. By contrast, the impacts of density and viscosity, which are changed with temperature, are negligible for the fluid velocity and overpressure generation.According to basin modeling results, even if the temperature changed 50 ℃, the change of the Upper Triassicoverpressure caused by disequilibrium compaction is very small(less than 1%).

5 DISCUSSION 5.1 Present Temperature-Pressure Relationship in Sedimentary BasinsThe relationship of temperature-pressure in present sedimentary basins is the result of complicated interactionafter geological scale evolution. Taking the basin tectonic setting and evolution into consideration isnecessary when analyzing the present temperature-pressure relationship. It is hypothesized that basins consistof several “closed” systems(Liu et al., 2012). In each system, temperature and pressure keep linear:

where P is pressure in MPa, T is temperature in ℃, K and L are constants in MPa/℃ and MPa, respectively.Then we can obtain the temperature-pressure slope of the system in the following form:

where △P is pressure gradient in MPa/100 m, △T is geothermal gradient in ℃/100 m.

For the shallow hydrostatic system, the slope K of temperature-pressure is mainly controlled by the geothermal gradient because △P remains constant about 1 MPa/100 m. The geothermal gradient, which is changeable for different basins with a common range of 1.5 ℃/100 m~4.5 ℃/100 m, has a great effect on K. Taking China as an example, the geothermal gradient is higher for the basins in the east(△T >3.5 ℃/100 m)than that for the basins in the middle and west(△T < 2.5 ℃/100 m). Therefore, the K of the shallow systems in eastern China is higher than that in middle and western China as a whole. The K of overpressure systems in the deep is controlled by the pressure gradient(0.8 MPa/100 m~2.2 MPa/100 m) and geothermal gradient together. The present pressure gradient is the result of complex interaction with the geological evolution and the present geothermal gradient is decided by the thermal background of the basin and the thermal properties of sediments.

5.2 Other Effects on the Pressure During Tectonic UpliftElastic or inelastic deformation may occur by the overlying lithostatic pressure unloading with tectonic uplift. Based on physical simulation experiments, Jiang et al.(2007)demonstrated that the amount of volume increasing caused by pressure unloading for natural s and stone is usually less than 1% and 80% of the increasing occurred within the pressure of 5 to 0 MPa. Folds, faults and fractures are commonly inelastic deformations with tectonic uplift. The Central Paleo-Uplift is far away from the margin of the basin and experienced a regional integral uplift since the Himalayan movement. Fold and fault deformations are not intense in this period. Fractures, the potential leakage pathways for fluid, have great destruction effect on the sealing of reservoirs and overpressure systems. Several high-quality seals exist in the Sichuan Basin(shown in Fig. 2 left). Seals in the Central Paleo-Uplift are well-preserved and that is the key for the overpressures and gas reservoirs preserved in this area. The change of porosity caused by fractures is very small. Even in a fractured formation, the fracturerelated porosity is only 0.01% to 0.04%(Chang et al., 2014), which has very limited effects on overpressure. However, fracture could increase the permeability of compact rocks and increase the fluid velocity and pressure adjusting in the overpressure system. In conclusion, the effect of the deformation caused by tectonic uplift is not primary for the deep buried overpressure systems in the Sichuan Basin, which are mainly composed of tight s and stone and carbonate.

It should be noted that the thermal expansion is significantly different between formation water and hydrocarbon, especially for gases. For gas-bearing strata, the temperature-pressure relationship differs to the relations shown in Fig. 5 and even pressures of gas-bearing strata may be overpressured with uplift and erosion(Katahara and Corrigan, 2002). Formation water is the dominant pore fluid in the basin. Even in the gas production layers in the Xujiahe Formation, the water saturation is 45%~96%(Zeng et al., 2009). Hence, we suggest that overpressures in the Central Paleo-Uplift decreased roughly in accordance with the relation demonstrated in Fig. 5 during the tectonic uplift.

6 CONCLUSIONBased on the analysis of the physical fields of temperature and pressure in the Central Paleo-Uplift in theSichuan Basin, we can obtain the following conclusions:

(1)Multiple overpressure systems exist in the Central Paleo-Uplift in the Sichuan Basin. The pressure ofthe same overpressure system varies in lateral direction, such as the Cambrian pressure is normal in the Weiyuanarea and overpressured in Moxi-Gaoshiti; the pressure coefficient of the Xujiahe Formation in the Moxi-Gaoshitiarea is less than that in the Bajiaochang area. Combining with the present distribution characteristics of thegeothermal field, we found that positive correlations between pressure and temperature exist in each pressuresystems.

(2)The relation of temperature and pressure in absolutely sealing condition is revealed through physicalsimulation. Temperature-pressure is almost linear when pressure is greater than 15 MPa, with a slope of about1.076 MPa/℃. The difference in temperature reduction can be regarded as the primary reason for variousintensity of pressure in the Central Paleo-Uplift. Besides that, some extent of lateral transfer and leakage ofpressure occurred in this area.

(3)Temperature plays an important role in hydrocarbon generation from source rocks and gas generationfrom oil cracking. Combining the reconstructed thermal history and microthermometry of fluid inclusions, the Lower Paleozoic overpressure caused by oil cracking was formed during 180~110 Ma and redistributedat the beginning of the uplift(~90 Ma). The effect of temperature on the generation of the Upper Triassicdisequilibrium compaction overpressure is negligible.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSWe would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and valuable commentson the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars(41125010), National 973 Project(2011CB201101) and National Science and Technology Major Project(2011ZX05007-002).

| [1] | Barker C. 1972. Aquathermal pressuring-role of temperature in development of abnormal-pressure zones. AAPG Bulletin, 56(10): 2068-2071. |

| [2] | Bethke C M. 1985. A numerical model of compaction-driven groundwater flow and heat transfer and its application to the paleohydrology of intracratonic sedimentary basins. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 90(B8): 6817-6828. |

| [3] | Chang L J, Zhao L B, Yang X J, et al. 2014. Application of industrial computed tomography (ICT) to research of fractured tight sandstone gas reservoirs. Xinjiang Petroleum Geology (in Chinese), 35(4): 471-475. |

| [4] | Deng B, Liu S G, Liu S, et al. 2009. Restoration of exhumation thickness and its significance in Sichuan Basin, China. Journal of Chengdu University of Technology (Science & Technology Edition) (in Chinese), 36(6): 675-686. |

| [5] | Guo Y C, Pang X Q, Chen D X, et al. 2012. Evolution of continental formation pressure in the middle part of the Western Sichuan Depression and its significance for hydrocarbon accumulation. Petroleum Exploration and Development (in Chinese), 39(4): 426-433. |

| [6] | Han Y H, Wu C S. 1993. Geothermal gradient and heat flow values of some deep wells in Sichuan Basin. Oil and Gas Geology (in Chinese), 14(1): 80-84. |

| [7] | Hao F, Guo T L, Zhu Y M, et al. 2008. Evidence for multiple stages of oil cracking and thermochemical sulfate reduction in the Puguang gas field, Sichuan Basin, China. AAPG Bulletin, 92(5): 611-637. |

| [8] | Hao G L, Liu G D, XieZ Y, et al. 2010. Distribution and origin of abnormal pressure in Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation reservoir in central and southern Sichuan. Global Geology (in Chinese), 29(2): 298-304. |

| [9] | He L J, Xu H H, Wang J Y. 2011. Thermal evolution and dynamic mechanism of the Sichuan Basin during the Early Permian-Middle Triassic. Science China: Earth Sciences, 54(12): 1948-1954. |

| [10] | He L J, Huang F, Liu Q Y, et al. 2014. Tectono-thermal evolution of Sichuan Basin in Early Paleozoic. Journal of Earth Sciences and Environment (in Chinese), 36(2): 10-17. |

| [11] | Huang F, Liu Q Y, He L J. 2012. Tectono-thermal modeling of the Sichuan Basin since the Late Himalayan Period. Chinese Journal of Geophysics (in Chinese), 55(11): 3742-3753, doi: 10.6038/j.issn.0001-5733.2012.11.021. |

| [12] | Jackśon K J, Burnham A K, Braun R L, et al. 1995. Temperature and pressure dependence of n-hexadecane cracking. Organic Geochemistry, 23(10): 941-953. |

| [13] | Jiang Z X, Tian F H, Xia S H. 2007. Physical simulation experiments of sandstone rebounding. Acta Geologica Sinica (in Chinese), 81(2): 244-249. |

| [14] | Katahara K W, Corrigan J D. 2002. Effect of gas on poroelastic response to burial or erosion. //Huffman A R, Bowers G L, eds. Pressure Regimesin Sedimentary Basins and Their Prediction.AAPG Memoir 76, 73-78. |

| [15] | Li S X, Shi Z J, Liu X Y,et al. 2013. Quantitative analysis of the Mesozoic abnormal low pressure in Ordos Basin. Petroleum Exploration and Development (in Chinese), 40(5): 528-533. |

| [16] | Liu Z, Zhu W Q, Sun Q, et al. 2012. Characteristics of geotemperature-geopressure systems in petroliferous basins of China. Acta Petrolei Sinica (in Chinese), 33(1): 1-17. |

| [17] | Liu S G,Wang H, Sun W, et al. 2008. Energy field adjustment and hydrocarbon phase evolution in Sinian-Lower Paleozoic Sichuan Basin. Journal of China University of Geosciences, 19(6): 700-706. |

| [18] | Liu S G, Deng B, Li Z W, et al. 2012. Architecture of basin-mountain systems and their influences on gas distribution: A case study from the Sichuan basin, South China. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 47(2): 204-215. |

| [19] | Lu Q Z, Hu S B, GuoT L, et al. 2005. The background of the geothermal field for formation of abnormal high pressure in the northeastern Sichuan basin. Chinese Journal of Geophysics (in Chinese), 48(5): 1110-1116, doi:10.3321/j.issn:0001-5733.2005.05.019. |

| [20] | Luo X R, Vasseur G. 1992. Contributions of compaction and aquathermal pressuring to geopressure and the influence of environmental conditions. AAPG Bulletin, 76(10): 1550-1559. |

| [21] | Osborne M J, Swarbrick R E. 1997. Mechanisms for generating overpressure in sedimentary basins: a reevaluation. AAPG Bulletin, 81(6): 1023-1041. |

| [22] | Qiu N S, Hu S B, He L J. 2004. Theory and Application of Thermal Regime Study in Sedimentary Basins (in Chinese). Beijing: Petroleum Industry Press, 240. |

| [23] | Qiu N S, Qin J Z, McInnes B I A, et al. 2008. Tectonothermal evolution of the Northeastern Sichuan Basin: Constraints from apatite and zircon (U-Th)/He ages and vitrinite reflectance data. Geological Journal of China Universities (in Chinese), 14(2): 223-230. |

| [24] | Tian H, Xiao X M, Wilkins R W T, et al. 2008. New insights into the volume and pressure changes during the thermal cracking of oil to gas in reservoirs: Implications for the in-situ accumulation of gas cracked from oils. AAPG Bulletin, 92(2): 181-200. |

| [25] | Tian Y T, Zhu C Q, Xu M, et al. 2011. Post-Early Cretaceous denudation history of the northeastern Sichuan Basin: constraints from low-temperature thermochronology profiles. Chinese Journal of Geophysics (in Chinese), 54(3): 807-816, doi:10.3969/j.issn.0001-5733.2011.03.021. |

| [26] | Wang M J, Bao C, Li M J. 1989. Petroleum geology of Sichuan Basin (in Chinese). //ZhaiG M ed. Petroleum Geology of China, Volume 10. Beijing: Petroleum Industry Press, 516. |

| [27] | Wang W, Zhou Z Y, Guo T L, et al. 2011. Early Cretaceous-Paleocene Geothermal Gradients and Cenozoic Tectonothermal History of Sichuan Basin. Journal of Tongji University (Natural Science) (in Chinese), 39(4): 606-613. |

| [28] | Wang Z L, Sun M L, Zhang L K, et al. 2004. Evolution of abnormal pressure and model of gas accumulation in Xujiahe Formation, western Sichuan Basin. Earth Science-Journal of China University of Geosciences (in Chinese), 29(4): 433-439. |

| [29] | Waples D W. 2000. The kinetics of in-reservoir oil destruction and gas formation: constraints from experimental and empirical data, and from thermodynamics. Organic Geochemistry, 31(6): 553-575. |

| [30] | Wei G Q, Jiao G H, Yang W, et al. 2010. Hydrocarbon pooling conditions and exploration potential of Sinian-Lower Paleozoic gas reservoirs in the Sichuan Basin. Natural Gas Industry (in Chinese), 30(12): 5-9. |

| [31] | Xie X L, Yu H J. 1988. The characteristics of the regional geothermal field in Sichuan Basin. Journal of Chengdu College of Geology (in Chinese), 15(4): 110-117. |

| [32] | Xie Z Y, Yang W, Gao J Y, et al. 2009. The characteristics of fluid inclusion of Xujiahe Formation reservoirs in centralsouth Sichuan Basin and its pool-forming significance. Bulletin of Mineralogy, Petrology and Geochemistry (in Chinese), 28(1): 48-52. |

| [33] | Xu G S, Meng Y Z, Zhao Y H, et al. 2009. The study of accumulation mechanism of natural gas in Jialingjiang Formation, Moxi-Longnsi area in the middle of Sichuan Basin. Petroleum Geology & Experiment (in Chinese), 31(6): 576-582. |

| [34] | Xu H L, Wei G Q, Jia C Z, et al. 2012. Tectonic evolution of the Leshan-Longnüsi paleo-uplift and its control on gas accumulation in the Sinian strata, Sichuan Basin. Petroleum Exploration and Development (in Chinese), 39(4): 406-416. |

| [35] | Xu H, Zhang J F, Tang D Z, et al. 2012. Controlling factors of underpressure reservoirs in the Sulige gas field, Ordos Basin. Petroleum Exploration and Development (in Chinese), 39(1): 64-68. |

| [36] | Xu M, Zhu C Q, Tian Y T, et al. 2011. Borehole temperature logging and characteristics of subsurface temperature in the Sichuan Basin. Chinese Journal of Geophysics (in Chinese), 54(4): 1052-1060, doi:10.3969/j.issn.0001-5733.2011.04.020. |

| [37] | Yang J X, Gao S L, Wang Z L. 2003. Pore pressure characteristics and petroleum migration in the Upper Triassic Formation in the central-southern of the Sichuan Basin. Gas Exploration and Development (in Chinese), 26(2): 6-11. |

| [38] | Yao J J, Chen M J, Hua A G, et al. 2003. Formation of the gas reservoirs of the Leshan-Longnüsi Sinianpaleo-uplift in central Sichuan. Petroleum Exploration and Development (in Chinese), 30(4): 7-9. |

| [39] | Zeng Q G, Gong C M, Li J L, et al. 2009. Exploration achievements and potential analysis of gas reservoirs in the Xujiahe formation, central Sichuan Basin. Natural Gas Industry (in Chinese), 29(6): 13-18. |

| [40] | Zhu C Q, Xu M, Shan J N, et al. 2009. Quantifying the denudations of major tectonic events in Sichuan basin: Constrained by the paleothermal records. Geology in China (in Chinese), 36(6): 1268-1277. |

| [41] | Zhu C Q, Xu M, Yuan Y S, et al. 2010. Palaeogeothermal response and record of the effusing of Emeishan basalts in the Sichuan basin. Chinese Science Bulletin, 55(10): 949-956. |

2015, Vol. 58

2015, Vol. 58