2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

Geographically, the western region of China mainl and refers to a vast region encompassing Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai and the western of Gansu and Sichuan. The Tibetan plateau in south has a higher elevation than the basins and mountains in north. Its tectonic pattern was resulted from the collision of India plate and Eurasia(Wan, 2004). This effect not only created the Tibet plateau known as the “roof of the world”, but also impacted the tectonic movement of adjacent areas, leading to the rejuvenation of the old orogenic belts such as Tian Shan. At present, the western region has become a hot area to study lithosphere structure, material flow in the crust and mantle, and mechanism of intraplate major quakes(Liu, 2007; Luo et al., 2008; Teng et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2007; Zhang and Chen, 2013). This paper used gravity and seismic tomography inversion results, in combination with other geological and geophysical data, to analyze the characteristics of crustal structure and their relation with major earthquakes in this western region of 70°E-100°E, 30°N-50°N, and attempted to provide reference for the relevant research.

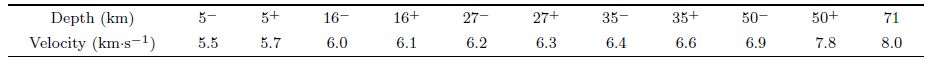

2 TECTONIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY AREATectonic characteristics in western China are complex and unique(Fig. 1)(Xu et al., 2000a; Yin, 2001; Wan, 2004). In the northern region, two basins separate three mountains: the Tarim Basin and Junggar basin are located between Altay, Tianshan, and Kunlun mountains, respectively. The Tianshan mountains run through Xinjiang, and extend westward to Kazakhstan and Kirghizstan, as a complex orogenic system consisting of many l and blocks and a series of orogenic belts. West Kunlun, Altun, Qilian mountains and other orogenic belts constitute the northwestern edge of the Tibetan plateau. West Kunlun is the tectonic boundary between the Qiangtang block and Tarim basin, Altun is the tectonic boundary between the Tarim basin and Qaidam terrane, and East Kunlun is the tectonic boundary between the Qaidam terrane and Qiangtang terrane. In the south region, the Himalaya, Lhasa terrane, Qiangtang, the Hoh Xil-Songpan-Garzê terrane, East Kunlun-Qaidam basin terrane, Qilian mountain terrane, West Kunlun and Karakorum mountains make up of the main body of the Tibetan plateau(Yin, 2001)

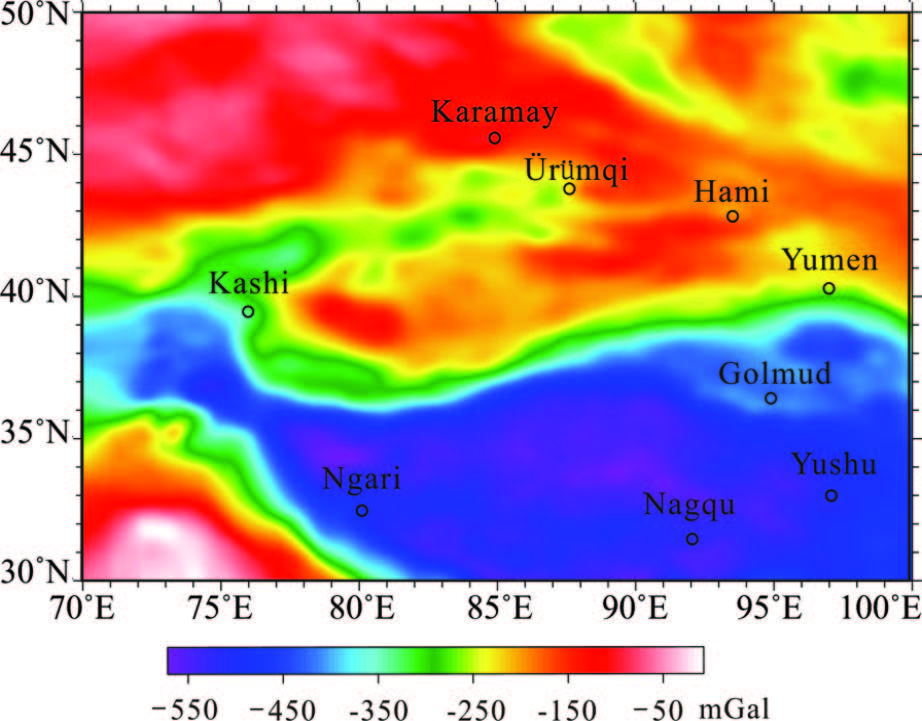

|

Fig.1 Tectonics of study area(modified from Yin, 2001) |

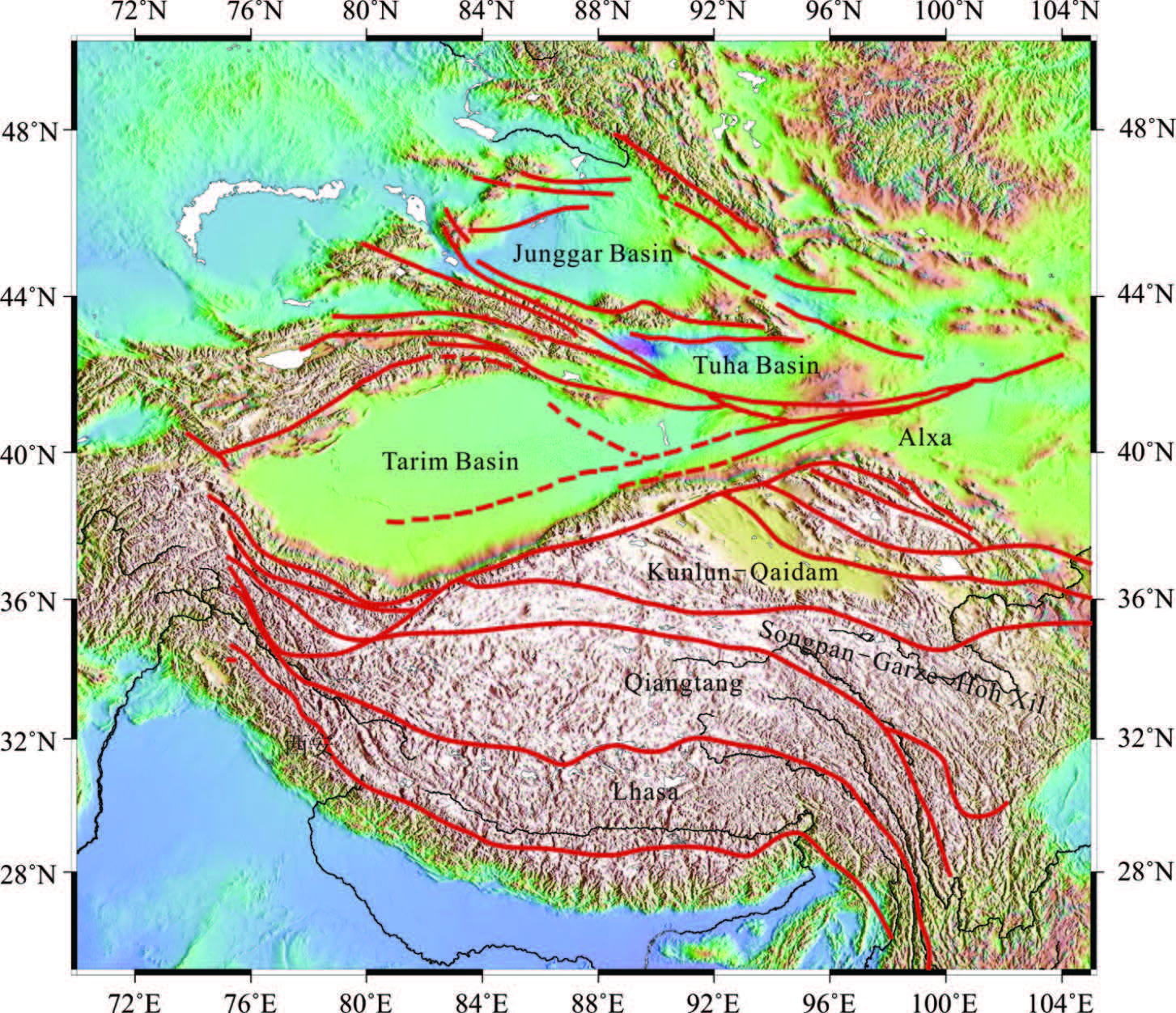

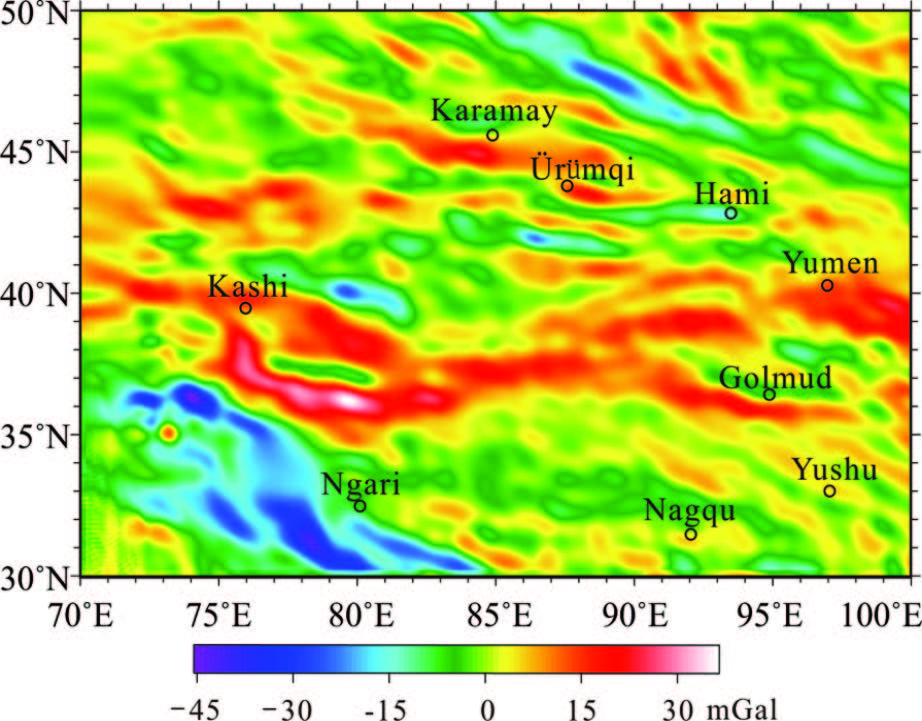

Based on the satellite gravity data provided by Scripps Institution of Oceanography(University of California, San Diego, UCSD)(Sandwell and Smith, 2009), this work prepared a free-air gravity anomaly map of western China(Fig. 2)with the grid accuracy 1' × 1'. Such gravity anomalies reflect the deviation of the earth shape and material distribution from the ellipsoid. As shown in Fig. 2, free air gravity anomalies of western China are large in EW direction, where the low-value areas correspond to low-lying basins, while higher ones corresponding with uplift blocks and mountains, such as the Tarim basin, Junggar basin and the Qaidam basin with values -200~100 mGal. In central and southern Tibet, they are 0~200 mGal. Obvious gradient zones are mainly distributed in Himalaya, Kunlun, Altun, Qilian and Tianshan Mountains with maximum 600 mGal. Undulating terrain and tectonic characteristics coincide well with distributions of free air gravity anomalies.

|

Fig.2 Free-air gravity anomalies of study area |

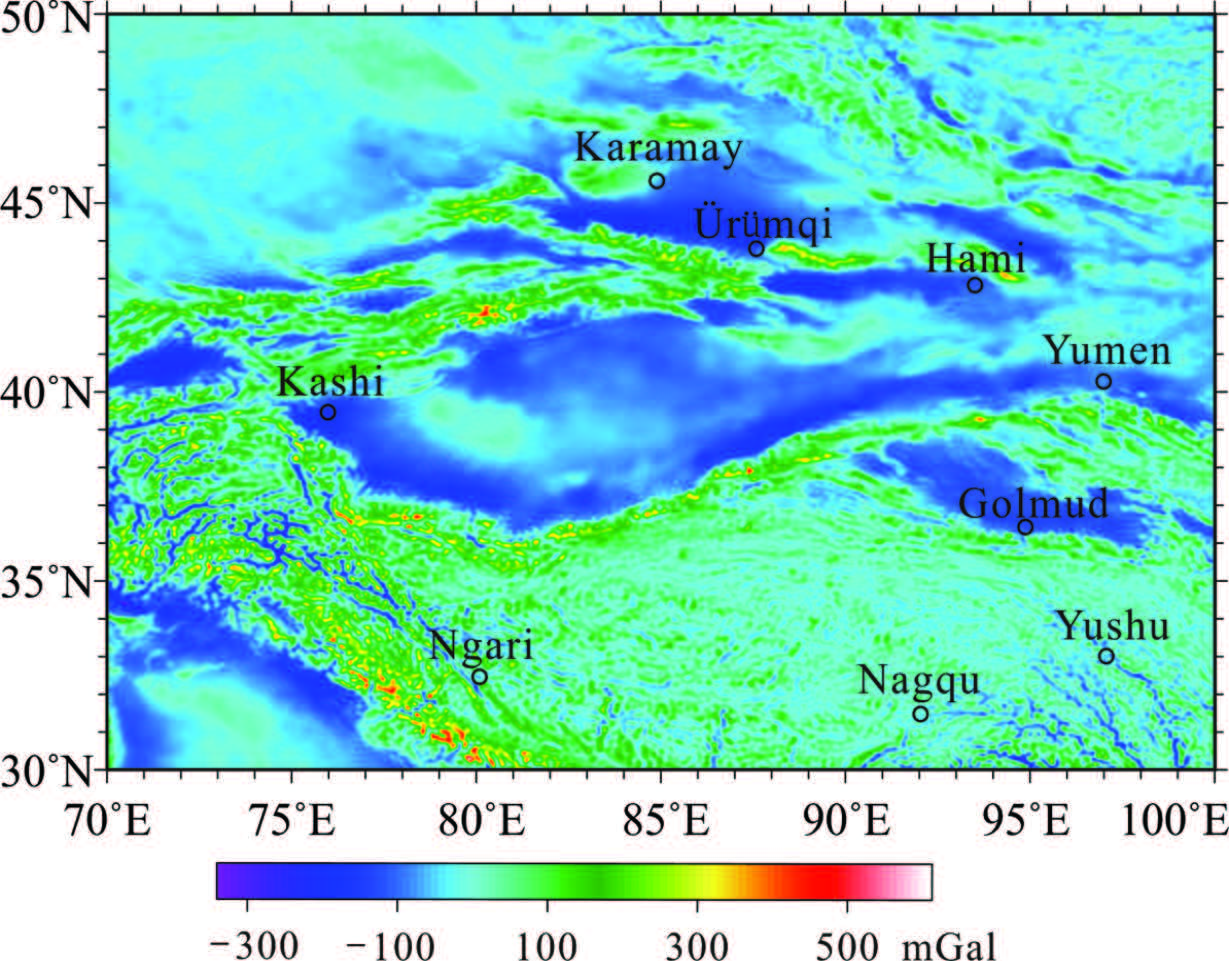

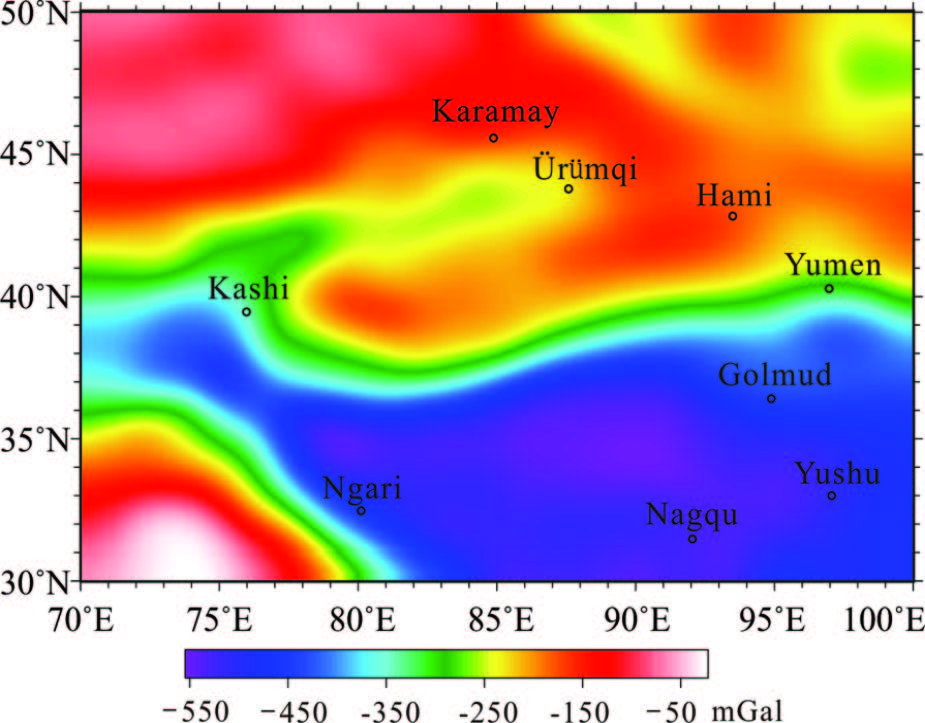

Bouguer gravity anomalies contain the effects of deviations of the crustal normal density distribution and structure, including the effect of crustal lower interface relief in the transverse direction relative to the mantle mass loss and earnings(Zeng, 2006). Bouguer gravity anomalies in western China, with higher values in south than the north(Fig. 3), range -571~-50 mGal.

|

Fig.3 Bouguer gravity anomalies of study area |

Bouguer gravity anomalies of Tibet plateau is low, where the Tanggula mountains, the central area of the plateau, can reach -550 mGal, as the lowest in whole China mainl and . In the north of the plateau, the Qaidam basin has smooth Bouguer gravity anomalies ranging from -425 to -375 mGal, which outline this basin on the map.

Three mountains and two basins in Xinjiang area are subparallel and intervening, corresponding well with the form of Bouguer gravity anomalies. The Junggar basin and Tarim Basin have relatively high anomalies, ranging between -225~-125 mGal, relatively gentle, with high-value closed contours in most portions. The Tianshan and Altay orogenic belts have low Bouguer anomalies between -275~-200 mGal.

On the gravity anomaly map parallel dense contours constitute gradient belts, several of which surround the Junggar basin, Tarim Basin, Qaidam Basin and Tibet plateau. They are(1)the Altay and Tianshan belt of a small scale;(2)the Kunlun-Qinling Mountains belt with a large scale, an arc-shaped distribution westward to Kunlun mountains, eastward to the Qaidam Basin and two branches; and (3)Himalaya-Hengduan mountains belt, meeting the central gradient belt in Sino-Burmese border, separates the Tibet plateau and other regions. These gradient belts and major tectonic faults in western China have a good correspondence.

In order to study the structural characteristics at different depths in western China, we separated the potential field with the wavelet transform method(Fig. 4, Fig. 5). Beaded high-frequency anomalies of the first-order detail wavelet reflect the shallow structure and lateral heterogeneity of the superficial substance. In Tianshan, West Kunlun, East Kunlun and Qilian Mountains, and Bachu uplift west of Tarim, shallow crustal gravity anomalies appear positive, and the Himalaya, Altay Mountains and the northern Tarim basin manifest as negative anomalies.

|

Fig.4 First-order detail wavelet of Bouguer gravity anomalies in study area |

|

Fig.5 Fourth-order approach wavelet of Bouguer gravity anomalies in study area |

Fourth-order approach wavelet mainly shows the trend of the regional field which can reflect the characteristics of deep substance. As can be seen from Fig. 5, there exist large stepped gradient values in the Tibetan plateau boundary, where transverse density of the deep materials begins to change largely, leading to an relative anomaly of 300 mGal.

3.2 Moho DepthThis paper inverts the depth of Moho interface(Fig. 6)by the Parker-Oldenburg method(Parker, 1973; Oldenburg, 1974)with gravity data and seismic profiles(Cui et al., 1995; Xu et al., 1996; Chen and Chen, 2003; Wang et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2005)with reference to the inversion results of Hao et al.(2014). In Fig. 6, the Moho depth features in western China have roughly mirroring relationship with undulating terrain, and strong link with the distribution of basins and orogenic belts. Overall, the Moho depths of basins are small, and those of mountains and plateaus are large. Seen from the Moho, orogenic belts in western regions such as the Tianshan, West Kunlun-East Kunlun, the Qilian orogenic belt, etc., are orogenic belts with mountain roots(Xiong, 2010). On the other h and , changes in the depth of the Moho also reflect the results of crustal movement. The Tibetan plateau is the region with the largest depth of the Moho in mainl and China. Since 50 Ma years ago, Indian continent moved northward to squeeze the Tibet plateau, causing crustal shortening and thickening, which has been confirmed by deep seismic sounding(Hauck et al., 1998, Chen et al., 2000).

|

Fig.6 Moho depth map of study area Seismic profiles: 1 Altun-Longmen Mountains(Wang et al., 2005); 2 Altay-Altun(Wang et al., 2004); 3 Golmud-Ejin Qi(Cui et al., 1995); 4 Ruoqiang-Altay(Chen and Chen, 2003); 5 Four profiles in Tianshan region(Xu et al., 1996) |

Moho depth of Chinese mainl and becomes deeper from east to west, and the overall trend of the Moho depth in the western region is deep in south and shallow in north. The Tibetan plateau has deeper Moho interface with average depth more than 60 km. The Moho in the central plateau region is as deep as 70 km, like a sunken concave. Complex multi-stage evolution of the Tibet plateau caused the particularity of the Moho depth distribution, but the concrete formation of the plateau is still controversial. A Moho depth gradient belt is present on in Tibetan plateau margin, corresponding to the height mutation on topography and deep faults; Himalaya, the southwest boundary, and Kunlun-Altun-Qilian mountains belt in the north, both have large gradient zones, particularly the biggest change in the Himalaya. The Himalaya collision zone is a very prominent extrusion strain b and , whose direction of movement is to the north and a bit more to the east by GPS. The rate of movement is between 35~42 mm·a-1(Wang et al., 2001), a high crustal shrinkage. Feng(1985)think this is where the density of the upper mantle changes abruptly.

Compared with the Tibetan plateau, the crustal thickness is relatively small in Xinjiang. The Tarim basin and other stable blocks such as Junggar and Turpan-Hami are Moho uplift regions with depth 41~48 km. Moho depth of the Bachu uplift in the western Tarim basin is less than the depression area of the basin. Moho depth of the Junggar basin is shallowest to about 41 km. Changes of crustal thickness, from west to east Tianshan, can be seen on the Moho depth map of the study area(Fig. 6), with maximum crustal thickness of east Tianshan 50 km, and west Tianshan 50~52 km; while in middle Tianshan a little shallower than the west and Tianshan Mountains, which reflects the complexity and segmentation of the tectonic movements of Tianshan. By analysis of the Moho depth, combined with other geological and geophysical data, Xiong(2010)suggested that there may be different uplift mechanisms or in different stages of orogeny in East and West Tianshan. As East Tianshan is located at the eastern margin of Junggar basin, it surfers less effect of collision than west Tianshan, but likely accompanied by mantle upwelling, which led to the extension of East Tianshan.

3.3 Seismic TomographyFigure 7 shows the results of seismic tomography in western China(Xu et al., 2000a). On images of different depths, the positive disturbance means velocity is higher than the initial model, negative perturbation represents the velocity is lower than the reference value of the initial model. The interface depths and the velocity model of the layers are selected as shown in Table 1. In this paper only relevant depths are selected to discuss.

|

Fig.7 Seismic tomography of study area(a)Velocity image of 5+ km;(b)Velocity image of 27+ km;(c)Velocity image of 35+ km;(d)Velocity image of 50+ km;(e)Velocity image of 71 km. |

| Table 1 Interface depths and initial velocity values |

The 5+ km depth velocity image(Fig. 7a)reflects the basic characteristics of the shallow geological structure. Altay, Tianshan and western boundary mountain of Junggar are high velocity zones; basins and major depressions as the Junggar basin, Kuqa depression of South Tianshan, western and southwestern Tarim basin, and Qaidam basin are low velocity zones. The difference of velocity at this depth mainly relates to lithological composition. Orogenic belts are mainly Paleozoic, even Achaean strata, usually with higher velocity; and the velocity of relatively loose, less consolidated Cenozoic sediments in basins and depressions is generally low.

On the 27+ km depth velocity image(Fig. 7b), Altay mountain, Tianshan, and west of Junggar, central Tarim and other places are still high speed areas; the Junggar basin, Kuche depression, Qaidam basin, and West Kunlun, Pamir etc. are still low velocity zones. The 27+ km depth velocity distribution is similar to that of 5+ km, which shows that the structure of the crust is still associated with geologic structure in the shallow subsurface. There is an obvious low velocity zone trend of north and south between East and West Tianshan. It is connected with the low velocity zone at the southern margin of the Junggar basin, and East and West Tianshan mountains may be discontinuous in deep structure.

The 35+ km depth velocity image(Fig. 7c)reflects the velocity distribution in lower crust. Altay, Tianshan, and northern, eastern and western Junggar basin are high speed areas, the low velocity zone south of the southern Junggar basin extends into the middle of the Tianshan Mountains, separating the East and West Tianshan highspeed zone, inherits the properties of East and West Tianshan tectonic boundary. Bachu uplift in southwest of Tarim basin is a high-speed area, the northeast side of the Pamirs to the southwestern Tarim basin, southern margin of Tarim basin to the West Kunlun piedmont, these two areas are still low velocity zones. The Bei Shan in Gansu is a high-speed area, Qaidam Basin is a low-velocity zone, and the velocity distribution of the upper crust extends to the lower crust, where the change is very stable.

The 50+ km depth velocity image(Fig. 7d)shows the variation of crustal thickness and shape of the Moho roughly. The negative disturbance usually corresponds to the Moho depression, positive perturbations correspond to the Moho uplift, which can qualitatively estimate the Moho depth. The central part and the eastern Beita mountain of the Junggar basin, Santanghu area, southeast of Kazakhstan, Turpan-Hami basin to the Bei Shan-Dunhuang of Gansu, the northern part and southwest edge of the Tarim basin are high-speed areas, where the top of upper mantle of these areas are uplifted, and Moho depth should be less than 50 km. According to the calculation results of gravity data, the crustal thicknesses of most parts are between 42~48 km. In an artificial seismic sounding profile across the Junggar basin, Altay-Altun profile(Wang et al., 2004), the Moho interface of the Junggar basin is warped upward, with a depth of about 46 km; and in the southern Junggar basin, Moho surface increases to around 50 km. These phenomena and the results of this study are basically the same.

According to the results of deep seismic sounding(Shao and Zhang, 1994; Ding et al., 1996; Jiang, 1997; Zhang et al., 1998; Li et al., 2002), the Moho depth in most parts of the Tarim basin are between 40~50 km. Because the top of the upper mantle is uplifted, seismic tomography shows high speed characteristics in this basin, but its southern portion has larger differences. Wide angle reflection seismic data(Li et al., 2002)show the low-angle underthrust of Tarim crust to West Kunlun Mountains, thus Moho depth gradually deepens from north to south, which is 42±2 km below the central uplift of Tarim, 47~57 km in the southwest depression, and reaches the maximum 62 km below the West Kunlun Mountains. The results of this paper provide a favorable basis for the explanation of the above phenomena. Although the rest of the Moho uplift areas is difficult to compare due to the lack of data, these uplift areas, mostly lying in the basin and the stable block, has the Moho depth about 45 km as analyzed previously. Altay, Tianshan(including part in Kyrgyz territory), Pamirs, and Qaidam basin are low velocity zones, which indicate that the average crustal thickness of the orogenic belts and the Tibetan plateau is more than 50 km, which is basically consistent with the existing knowledge. The Shaya-Buerjin artificial seismic profile(Zhao et al., 2001)across the West Tianshan shows Moho depth 55 km; seismic converted wave sounding(Shao et al., 1996)also indicated that the Moho of the Tianshan Mountains changes gradually from 42 km on both sides of the edge of the piedmont basin to 56 km in the mountain center. Therefore, the Moho depth of Tianshan is about 55 km. The velocity distribution from seismic tomography delineates Moho depression across the entire Tianshan(including part in Kyrgyz territory).

The 71 km depth velocity image(Fig. 7e)reflects the structure of upper mantle structure of the Xinjiang area and nearby Moho below the Tibetan plateau. The western part of West Kunlun, Tarim basin, Tianshan, most of Junggar basin, Altun, Beishan, and East Altay are high speed areas, which have relatively sTable lithospheric structure. Altay, Kyrgyz Tianshan, and South Tianshan to Pamirs are low-speed zones, indicating abnormal state in the top of upper mantle. Taking the Altun fault and West Kunlun as the boundary, low seismic velocity characterizes the northern Tibetan plateau. The crustal thickness may be a little larger than 71 km in most areas of the West Kunlun, Songpan-Garzê-Hoh Xil terrane, Qiangtang terrane and other parts of the Tibetan plateau.

There are two possible explanations for the low velocity of the Tibet plateau. One is to reflect the current tectonic activity of the Tibetan plateau due to constant intrusion of the hot material from depth, resulting in the low velocity zone in upper mantle. Zhao and Xie(1993)found an abnormal zone in the top of upper mantle of the Tibet plateau. Song et al.(1991)thought that the depth of part of the low velocity layer in upper mantle of the Tibet plateau is about 80~100 km. The other is that it may be caused by the large thickness of the crust of the Tibetan plateau. In Tarim, depth 71 km reaches the upper mantle, while it is only near the bottom of the crust in the Tibetan plateau. This difference can cause the low speed of the Tibetan plateau. The low velocity in top of the mantle of Altay is more meaningful. It is known that Altay is famous for precious metal mineral in China. Low velocity in the top of mantle may imply thermal activity of upper mantle material to a certain degree, which may become the source of magma upwelling. At this depth of the Tianshan mountains and boundary mountains of west Junggar, low velocity zones are not found. This may be one of the deep tectonic backgrounds of rich metal deposits in the Altay mountains. In summary, the orogenic belts in western China are generally the areas of Moho interface depression, basins are Moho interface uplifts. Although Moho of northern Tarim basin is relatively shallow, it is deep from the southern Tarim basin to the West Kunlun piedmont. Along the south and north sides of the Qilian mountains, crustal velocities of the Dunhuang block and the Qaidam basin are very different, with Moho uplift in north and the Moho depression in south.

3.4 Result AnalysisComparison of seismic tomography inversion and gravity inversion yields the following results. The central part of Junggar basin is a high speed region, with crustal thickness less than 50 km, while 42~45 km from gravity inversion, which is consistent with 45 km from artificial seismic sounding. The northern and southwestern margin of the Tarim Basin are high velocity zones, top of the upper mantle of these areas are upward warped, with Moho depth less than 50 km; while gravity inversion gave crustal thickness 46~49 km, and seismic sounding data show Moho depth in most Tarim between 40~50 km. The Qaidam basin is mainly of low velocity, with crustal thickness more than 50 km or 59~64 km from the gravity inversion. In these areas the gravity inversion results are in very good agreement with the results of seismic tomography. There are also different results by these two kinds of method in other areas. The Tianshan mountains are low-speed zones, seismic tomography crustal thickness more than 50 km, while gravity inversion provides 49~52 km. But the artificial seismic sounding profile and the seismic conversion sounding results suggest that Moho depth of Tianshan is about 55 km. The low velocity zone of Altay indicates that the crustal thickness is more than 50 km, while the gravity inversion result is 46~50 km. In the 71 km depth velocity image, the central area of the Tibetan plateau is the low velocity zone, suggesting that the crust thickness is more than 71 km, while the gravity inversion result is 60~70 km. We infer that the large difference between the two inversion results may be caused by differences of the measurement surfaces in high-elevation areas.

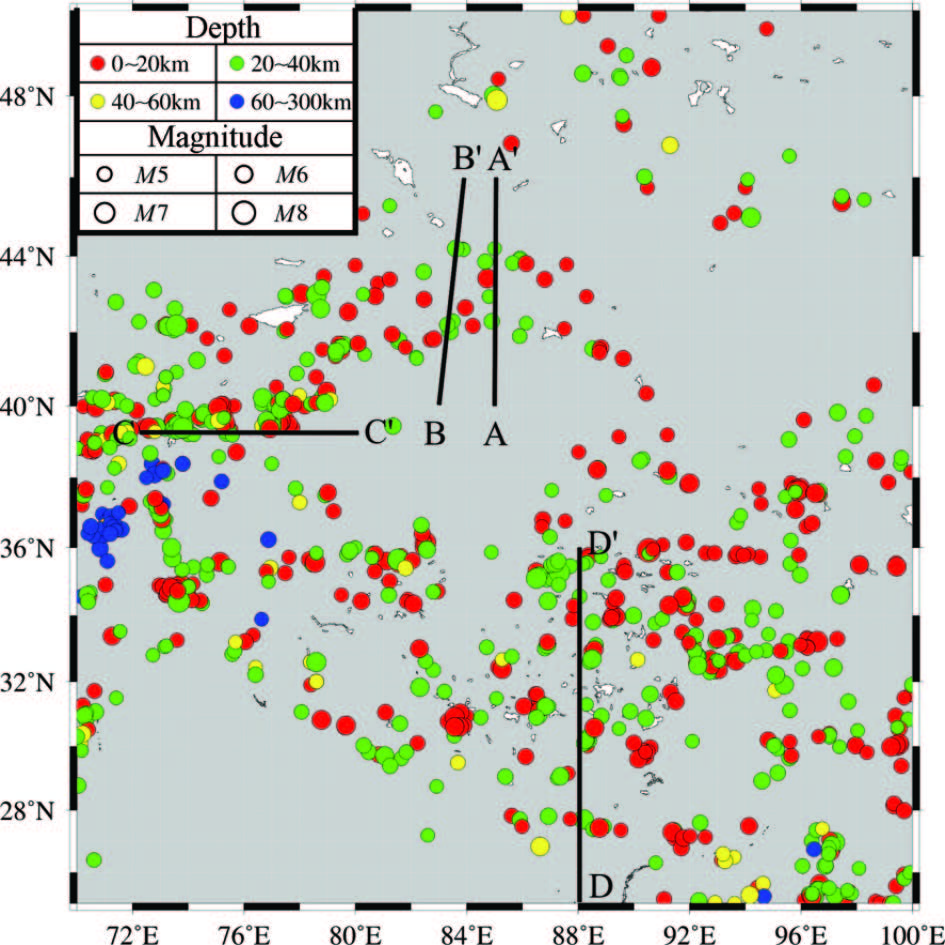

4 MAJOR EARTHQUAKES AND THEIR RELATION WITH CRUSTAL STRUCTUREMajor and /or great earthquakes frequently occur in western China, such as Tianshan, Altay, Pamirs and Kunlun as well known seismotectonic zones. These regions not only documented many major earthquakes in the history, but also recorded high seismicity in recent time. According to the earthquake catalogue of the China seismic network(CSN), from January 1, 1970 to February 28, 2014, a total of 1059 earthquakes above magnitude 5 occurred in this region(Fig. 8).

|

Fig.8 Epicenter and focal depth distribution of study area(AA', BB', and CC' are locations of three profiles in Fig. 9, DD' in Fig. 10) |

Comparison of inversion results of gravity and seismic tomography, and the distributions of earthquake epicenters and focal depth in the study area(Fig. 8), we can see that most earthquakes greater than magnitude 5 in western China are distributed within 40 km depth, a small amount deeper than 60 km which mostly located in the Pamir plateau and Himalayas. Under the stress field, the orogenic belts of upper crust have large rigidity, prone to brittle fracture. In contrast, the lower crust is easy to generate plastic deformation due to effects of pressure and temperature, which is not favorable to the occurrence of strong earthquakes. Recent studies have shown that tectonic environment for strong earthquakes is related closely to the lateral heterogeneity of media. Most strong earthquakes of western China occur in the boundary between rigid blocks and fold belts studded with compressive reverse faults that accommodate rapid vertical movement, such as Tianshan, Kunlun, Longmenshan mountains and the Xianshuihe seismic belt(Xu et al., 2000b, 2006; Tian et al., 2007).

In the northern Xinjiang area, the crustal thickness is less than 50 km in general. Earthquakes are almost distributed throughout the crust in Tianshan and Pamir plateau. In the West Kunlun, locations of the earthquake sources have also reached the Moho depth, consistent with Priestley et al.(2008)who made the analysis of the relationship between lithosphere structure and earthquakes in India, Himalaya and south Tibet. They suggest that in some regions, the whole crust, even to the Moho is seismogenic, mostly in the internal or margin of the Precambrian shield. Having analyzed the relationship between the temperature structure and velocity structure of the lithosphere, they also thought the earthquakes generally occurred in three cases: the “wet” upper crust with temperature at 350°C, the lower crust with high temperature and dry granulite facies, or the mantle with temperature lower than 600°C. These have very important significance. The following section of this paper focuses on relationship between crustal structure and seismic activity in western China.

The velocity structure of crust is important to know the crustal media properties; it can provide important information of earthquake hypocenters and medium structure. Combined with the distribution of seismic activity, it can also supply important evidence for the underst and ing of the causes of earthquakes and seismotectonic mechanism. For the environment of earthquakes in the Tianshan mountains, this article carries out the analysis by 3 seismic tomography profiles through Tianshan and Pamir plateau regions to study the earthquake mechanism from crustal velocity structure.

Comparing the result of seismic tomography with the three seismic tomography profiles in Tianshan(Fig. 9)we can see that most earthquakes occurred in the transition region from low velocity zone to the adjacent highspeed block. Earthquakes of northern Tianshan are mainly distributed between Tianshan and Junggar basin. From profile AA0 and BB0, great crustal velocity changes can be seen in the North Tianshan and Junggar basin. Southern Junggar basin has a double crust structure, of which crust velocities are different between upper crust and lower crust: upper crust is high velocity layer, and the horizontal low velocity layer in the middle crust is the ductile decollement belt. The upper crust thrusts to the both sides of the basin by the compression in NS direction along the ductile decollement belt, leading to the frequent earthquakes in the transition region.

|

Fig.9 Crustal velocity profiles(unit: km·s-1)(a)AA0 North Tianshan crustal velocity profile;(b)BB0 Kuqa-Usu crustal velocity profile;(c)CC0 Wuqia-Jiashi earthquake zone crustal velocity profile. |

From the profile BB', depth of the basement of Kuche depression is 15 km, and a low-velocity layer appears in depth 20~30 km which extends northward to the middle crust of Tianshan. The low velocity of the upper crust of the Kuche depression reflects the characteristics of the sediment layer, and the low velocity of the middle and lower crust may be related with the properties of the deep faults. Those deep faults in the south edge of Tianshan are mostly lithospheric fractures, with Variscan period granite on the surface. We infer that hot upper mantle material may have invaded along the fracture channel, forming a low velocity layer in the middle crust, and the change of crustal thermal state affected the rheological properties of the crust, then local crustal deformation and earthquakes occurred.

From profile CC' we can see in the Tianshan-Pamir conjunctive zone, seismic activity is also intrinsically linked to the crustal structure. Most earthquakes occurred near the western edge of the high-speed blocks in the Tarim basin. The latest GPS measurements along the 76°E across Pamir-Tianshan indicate that crustal shortening rate is 20~24 mm·a-1, accounting for almost half of the northward motion rate of the India plate(Li, 2012). The relative motion of the two rigid blocks, the Pamir and Tarim, produces larger stress near the tectonic boundary. The deformation is mainly adjusted by the slip of the boundary fault, Kashi-Yecheng transform zone, between Pamir and Tarim. The low velocity zones around Jiashi and Kashi play a role of the ductile shear belt. Therefore, one of the deep causes for Jiashi earthquakes is the relative movement of the Pamir block and Tarim block in the east and west sides of the Kashi ductile shear zone.

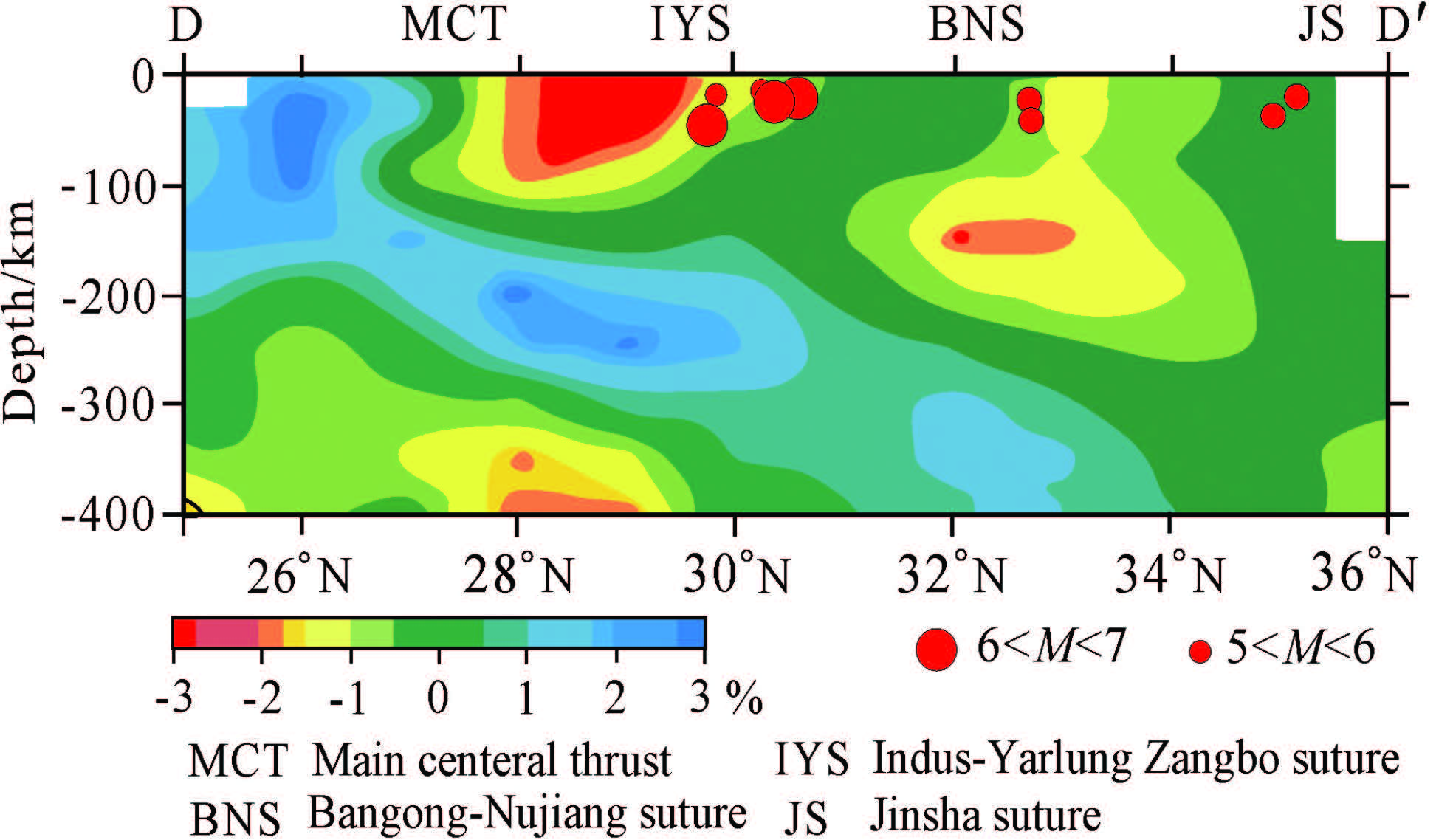

According to the profile of tomography along the 88°E in Tibet plateau(profile DD0, in Fig. 10)(Zheng, 2006), south of the MCT(the main central thrust)is a high-speed belt, which extends from the crust to upper mantle. There exists a low velocity body between MCT and IYS(India River-Yarlung Zangbo suture zone), the Himalaya low velocity zone, that may be the reflection of high temperature and partial melting. Qiangtang terrane, in the north of the Bangong-Nujiang suture zone, shows the low velocity, being explained as the upwelling of mantle material due to the northward subduction of the India plate, which formed a lowvelocity layer in the crust. From Fig. 10 we can see there are some relationships between the distribution of earthquakes in the Tibetan plateau and the crustal velocity structure. Earthquakes occur frequently between the southern high-speed India plate and lowspeed Himalaya collision zone, also between the lowspeed Himalaya collision zone and the northern suture zone. We speculate that partial melting generated by ductile shear structure, and tectonic stress generated by subduction of the plate, gave birth to a large number of earthquakes in the northern and the southern edge of Himalaya, especially in the place where this low velocity zone connects with the south high-speed zone. In addition, the upwelling of mantle generated crustal laterally heterogeneity between Qiangtang terrane and its edge, which made the edge of the Qiangtang terrane, the Bangong-Nujiang suture zone and the Jinsha River suture zone, become the strong earthquake prone zone.

|

Fig.10 Profile of major earthquakes and seismic tomography along 88°E in Tibetan plateau(modified from Zheng, 2006) |

Combined with previous studies and the 4 profiles, we can see the strong earthquakes are mainly distributed in the regions with great crustal velocity differences. The geological evolution, such as fault formation, crustal composition and thermal state, plate movement and deformation can generate the inhomogeneous distribution of crustal velocity. No matter the upwelling of hot material, or the strong non-uniformity caused by the crust fracture, under the action of tectonic stress, these regions with inhomogeneous media are prone to major earthquakes. This is one of the reasons for frequent major earthquakes in orogenic belts and basin-mountain boundaries in western China.

5 CONCLUSIONSBy analyzing the relation between the crustal structure and major earthquakes in western China, we have made the following underst and ings:

(1)Moho depth of China mainl and tend to be deeper from east to west. The Tibetan plateau has larger Moho depths more than 60 km on average, maximum 70 km at its central portion, like a sunken concave. Compared with the Tibetan plateau, the crustal thickness is relatively smaller in Xinjiang, especially in basins. Overall, the undulation of Moho interface corresponds with characteristics of gravity anomalies.

(2)Uneven characteristics of the crustal structure are obvious. Upper crust of main orogenic belts is highspeed, while low speed in basins and the depressions. Structure of the middle crust is associated with the surface geology. There is a low-velocity zone of north-south direction between the East and West Tianshan mountains, which connects with the low-speed belt in the southern margin of the Junggar basin. This phenomenon indicates that it is a discontinuity of East and West Tianshan mountains in the deep structure. The Qaidam Basin north of the Tibetan plateau is a low velocity zone, keeping stable from upper crust to the lower crust. The crustal thickness of Western China changes greatly, and Moho interface is complex. Orogenic belts lie generally in Moho depression areas, while Moho of basins is usually upward warped. The gravity inversion results are mostly in good agreement with the results of seismic tomography, but there are also some differences of crustal structure in some areas derived from these two methods.

(3)The seismic activity is closely related with crustal structure in western China. Major earthquakes occur in regions with large different crustal velocities, such as the connecting sites of basins and orogenic belts, like Tianshan, Pamir and West Kunlun. The geological evolution, such as fault formation, crustal composition and thermal state, plate movement and deformation can lead to the inhomogeneous distribution of crustal velocity. No matter the upwelling of hot material or the strong non-uniformity caused by the crust fracture, under the action of tectonic stress, these regions with inhomogeneous media are prone to major earthquakes. This is one of the reasons for frequent major earthquakes in orogenic belts and basin-mountain boundaries in western China.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThe authors wish to thank Liu Guangding of IGGCAS for his guidance. This work was supported by the program from China Geological Survey(GZH200900504).

| [1] | Chen J X, Chen J L. 2003. The crustal structure and velocity feature from Ruoqiang-Altai seismic profile in Xinjiang region. Xinjiang Petroleum Geology (in Chinese), 24(6):498-501. |

| [2] | Chen Z, Bruchfiel B C, Liu Y, et al. 2000. Global positioning system measurements from eastern Tibet and their implications for India/Eurasia intercontinental deformation. J. Geophys. Res.:Solid Earth (1978-2012), 105(B7):16215-16227. |

| [3] | Cui Z Z, Li Q S, Wu C D, et al. 1995. The crustal and deep structures in GOLMUD-EJIN QI GGT. Chinese J. Geophys.(in Chinese), 38(S2):15-28. |

| [4] | Ding D G, Wang G X, Liu W X, et al. 1996. West Kunlunorogenic Belt and Basin (in Chinese). Beijing:Geological Publishing House. |

| [5] | Feng R. 1985. The crustal thickness and distribution of upper mantle density of China. Acta Seismologica Sinica (in Chinese), 31(7):529-536. |

| [6] | Hao T Y, Hu W J, Xing J, et al. 2014. The Moho depth map (1:5000000) in the land and seas of China and adjacent areas and its geological implications. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese), 57(12):3869-3883, doi:10.6038/cjg20141202. |

| [7] | Hauck M L, Nelson K D, Brown L D, et al. 1998. Crustal structure of the Himalayan orogen at -90° east longitude from Project INDEPTH deep reflection profiles. Tectonics, 17(4):481-500. |

| [8] | Jiang C F. 1997. Opening-closing tectonics of Tarim Platform. Xinjiang Geology (in Chinese), 15(3):193-202. |

| [9] | Li Q S, Gao R, Lu D Y, et al. 2002. Tarim crustal subduction in the West Kunlun Mountainsthe evidence of wide-angle seismic survey. Acta Geoscientica Sinica (in Chinese), 23(5):442. |

| [10] | Li T. 2012. Active thrusting and folding along the Pamir Frontal Thrust System (in Chinese)[Ph. D. thesis]. Beijing:Institute of Geology, China Earthquake Administration. |

| [11] | Liu G D. 2007. Geodynamical evolution and tectonic framework of China. Earth Science Frontiers (in Chinese), 14(3):39-46. |

| [12] | Luo W X, Li D W, Wang X F. Focal depth and mechanism of intraplate earthquakes in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau.Earth Science (Journal of China University of Geosciences) (in Chinese), 33(5):618-626. |

| [13] | Oldenburg D W. 1974. The inversion and interpretation of gravity anomalies. Geophysics, 39(4):526-536. |

| [14] | Parker R L. 1973. The rapid calculation of potential anomalies. Geophys. J. Int., 31(4):447-455. |

| [15] | Priestley K, Jackson J, McKenzie D. 2008. Lithospheric structure and deep earthquakes beneath India, the Himalaya and southern Tibet. Geophys. J. Int., 172(1):345-362. |

| [16] | Sandwell D T, Smith W H F. 2009. Global marine gravity from retrackedGeosat and ERS-1 altimetry:Ridge segmentation versus spreading rate. J. Geophys. Res.:Solid Earth (1978-2012), 114(B1):B01411, doi:10.1029/2008JB006008. |

| [17] | Shao X Z, Zhang J R. 1994. Preliminary results of study of deep structures in Tarim Basin by the method of converted waves of earthquakes. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese),37(6):836. |

| [18] | Shao X Z, Zhang J R, Fan H J, et al. 1996. The crust structures of Tianshanorogenic belt:A deep sounding work by converted waves of earthquakes along Ürümqi-Korla profile.Acta Geophysica Sinica (in Chinese), 39(3):336-346. |

| [19] | Song Z H, An C Q, Chen G Y, et al. 1991. Study on 3D velocity structure and anisotropy beneath the west China from the Love wave dispersion. Acta Geophysica Sinica (in Chinese), 34(6):694-707. |

| [20] | Teng J W, Yuan X M, Zhang Y Q, et al. 2012. The stratificational velocity structure of crust and covering strata of upper mantle and the orbit of deep interaquifer substance locus of movement for Tibetan Plateau. Acta Petrologica Sinica (in Chinese), 28(12):4077-4100. |

| [21] | Tian Y, Zhao D P, Sun R M, et al. 2007. The 1992 Landers earthquake:Effect of crustal heterogeneity on earthquake generation. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese), 50(5):1488-1496. |

| [22] | Wan T F. 2004. Tectonics of China (in Chinese). Beijing:Geological Publishing House. |

| [23] | Wang Q, Zhang P Z, Niu Z J, et al. 2001. Chinese contemporary crustal movement and tectonic deformation. Science in China (in Chinese), 31(7):529-536. |

| [24] | Wang Y X, Han G H, Jiang M, et al. 2004. Crustal structure along the geosciences transect from Altay to AltunTagh.Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese), 47(2):240-249. |

| [25] | Wang Y X, Mooney W D, Han G H, et al. 2005. Crustal P-wave velocity structure from AltynTagh to Longmen mountains along the Taiwan-Altay geoscience transect. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese), 48(1):98-106. |

| [26] | Xiong X S. 2010. Moho depth and variation of the continent in China and its geodynamic implications(in Chinese)[Ph.D. thesis]. Beijing:China Academy of Geological Sciences. |

| [27] | Xu G M, Yao H J, Zhu L B, et al.2007. Shear wave velocity structure of the crust and upper mantle in western China and its adjacent area. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese), 50(1):193-208. |

| [28] | Xu Y, Feng X Y, Shstsilov V I. 1996. Deep velocity structure in the Tianshan region. Seismology and Geology (in Chinese), 18(4):375-381. |

| [29] | Xu Y, Liu F T, Liu J H, et al. 2000a. Crustal structure and tectonic environment of strong earthquakes in the Tianshan Earthquake Belt. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese), 43(2):184-193. |

| [30] | Xu Y, Liu F T, Liu J H, et al. 2000b. Seismic tomography on northwest orogenic belt and adjacent basins of Chinese Mianland. Science in China (Series D) (in Chinese), 30(2):113-122. |

| [31] | Xu Y, Liu J H, Liu F T, et al. 2006. Crustal velocity structure and seismic activity in the Tianshan-Pamir conjunctive zone. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese), 49(2):469-476. |

| [32] | Yin A. 2001. Geologic evolution of the Himalayan-Tibetan orogen Phanerozoic growth of Aisacontinetal. Acta Geoscientia Sinica (in Chinese), 22(3):193-230. |

| [33] | Zhang J R, Shao X Z, Fan H J. 1998. Deep sounding survey by converted waves of earthquakes in central part of the Tarim Basin and its interpretation. Seismology and Geology (in Chinese), 20(1):34-42. |

| [34] | Zhang J, Chen S. 2013. Gravity field analysis for crust and mantle structure of the Tibetan Plateau. Earthquake (in Chinese), 33(4):11-18. |

| [35] | Zhao J M, Liu G D, Lu Z X, et al. 2001. The crust-mantle transition zone beneath the Tianshanorogenic belt and the JunggarBasin and their geodynamic implications. Science in China (Series D) (in Chinese), 31(4):272-282. |

| [36] | Zhao L S, Xie J k. 1993. Lateral variations in compressional velocities beneath the Tibetan Plateau from Pn traveltime tomography. Geophys. J. Int., 115(3):1070-1084. |

| [37] | Zeng H L. 2006. Gravity Field and Gravity Exploration (in Chinese). Beijing:Geological Publishing House. |

| [38] | Zheng H W. 2006. 3-D velocity structure of the crust and upper mantle in Tibet and its geodynamic effect (in Chinese)[Ph. D. thesis]. Beijing:China Academy of Geological Sciences. |

2015, Vol. 58

2015, Vol. 58