2. School of Geosciences, China University of Petroleum, Qingdao 266580, China

The elastic properties of the rock depend on the microscopic structure of pore system significantly. Most rocks usually have two or even more than two different pore types, such as pore, crack, cavity, etc.; the complex pore system makes the relationship between the velocity and porosity of the rock highly scattered(Baechle et al., 2008; Sayers, 2008). Therefore, it needs to establish more accurate multiple-porosity rock physical models to characterize the variations of elastic moduli with porosity for porous rock.

Effective medium theory, such as Kuster-Toksöz theory and differential effective medium theory, has been used to study the elastic properties of porous rock. Kuster and Toksöz(1974)derived expressions for bulk and shear moduli of multiple-porosity rock by using wave scattering theory, in which the effects of elasticity, volume content and pore shape of inclusions are taken into account. But Kuster-Toksöz theory does not consider the interaction between different pores, and requires that the ratio of porosity to pore aspect ratio has to be much smaller than 1. Kuster-Toksöz theory has been shown to violate the upper and lower Hashin-Shtrikman bounds in some cases(Berryman, 1980). The differential effective medium(DEM)theory models two-phase composites by incrementally adding inclusions to the matrix phase, and is applied to the determination of the effective elastic properties of porous rocks that are dry or saturated by fluid through the numerical solution of differential equations(Berryman, 1980; Norris, 1985; Zimmerman, 1985; Berryman, et al., 2002). The DEM has the property that it can never violate rigorous bounds compared with the Kuster and Toksöz theory(Berryman, 1980; Berryman and Berge, 1996; Berryman et al., 2002). However, since the ordinary differential equations for bulk and shear moduli are coupled, it is more difficult to integrate them to yield accurate analytical formulae for the bulk and shear moduli. Therefore, the behavior of the bulk and shear moduli can only be accurately simulated through the numerical solutions of differential equations. Moreover, the effective elasticities of porous medium depend on the adding order of the inclusions, i.e. the pores or cracks with different aspect ratios.

Xu and White(1995)developed a double-porosity(stiff and soft pores)model(now is called Xu-White model)for shaly s and stones based on Kuster-Toksöz theory, which assumed that the volume contents of different pores depend on the s and and clay content respectively. But the model inherited the problems existing in Kuster-Toksöz theory, and had the computational efficiency problem for its iterative algorithm. Keys and Xu(2002)simplified the Xu-White model and obtained an approximation for dry-rock bulk and shear moduli by assuming a constant dry-rock Poisson’s ratio in coupled equations, which improved the computational efficiency. However the Poisson’s ratio or modulus ratio derived from their dry-rock approximation is not constant as they presupposed. Xu and Payne(2009)promoted the Xu-White model for shaly s and stones to carbonates and established the Xu-Payne model, but the model also had the same problems as the Xu-White model.

To solve the problem that DEM theory lacks analytical formulae, many researchers have made some efforts and achieved a series of achievements. Zimmerman(1991)derived the implicit analytical results for the elastic moduli of dry rock with spherical pores from DEM theory. Berryman et al.(2002)obtained approximate analytical results for the elastic moduli of dry and fully saturated cracked rock based on DEM theory. Li and Zhang(2010, 2012)derived analytical solutions of the bulk and shear moduli for dry rock with the three specific pore shapes: spherical pores, needle-shaped pores and penny-shaped cracks in order to decouple the differential equations by applying an analytical approximation for dry-rock modulus ratio. Similarly, Li and Zhang(2011)obtained analytical formulae for the bulk and shear moduli of dry rocks with ellipsoidal pores based on DEM theory. Those DEM analytical formulae were proposed based on the single-porosity system, and were used for the effective pore aspect ratio inversion and shear wave velocity prediction(Li et al., 2013).

The purpose of this paper is to obtain analytical formulae for the bulk and shear moduli of multiple-porosity dry rocks with ellipsoidal pores based on effective medium theory and use them to characterize the dry-rock moduli dependency on porosity. We first derive the differential schemes for Kuster-Toksöz theory from the Kuster-Toksöz expressions for bulk and shear moduli. Next we derive analytical solutions of the bulk and shear moduli for multiple-porosity dry rock with ellipsoidal pores based on DEM theory by applying an analytical approximation for dry-rock modulus ratio, in order to decouple the equations for bulk and shear moduli. And then we use the theoretical model for checking these approximations by comparison with numerical computations for the differential equations of the DEM, and the agreement between the analytical approximations and the full DEM is discussed. Finally the analytical approximations are applied to predict the variations of the bulk and shear moduli with respect to porosity for dry s and stone data, which were measured by Han et al.(1986)in the laboratory.

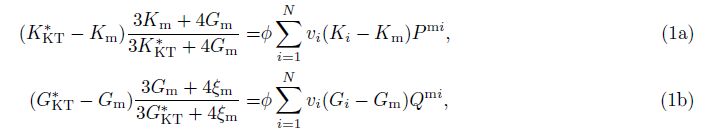

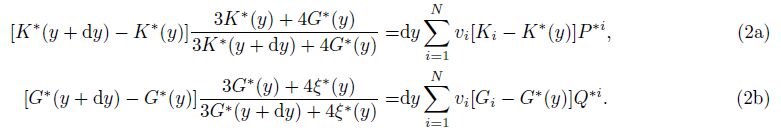

2 DIFFERENTIAL SCHEMES FOR KUSTER-TOKSÖZ THEORY AND THEIR NUMERICAL SOLUTIONBy using a long-wavelength first-order scattering theory, Kuster and Toksöz(1974)derived the expressions for the effective bulk modulus, KKT*, and shear modulus, GKT* of rock with N inclusions

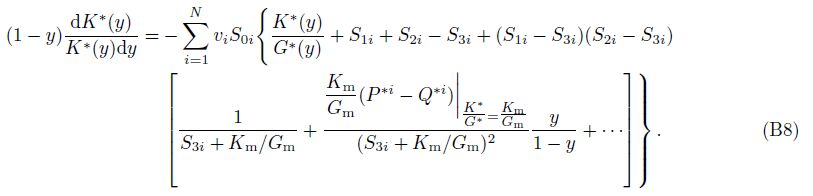

Kuster-Toksöz theory and differential effective medium theory can be combined to calculate the elastic properties of multiple-porosity rock(Xu and White, 1995; Keys and Xu, 2002). Differential effective medium theory takes the point of view that a composite material may be constructed by making infinitesimal changes in an already existing composite(Norris, 1985; Berryman et al., 2002; Mavko et al., 1998). Therefore, when a tiny porosity dy is added into the composite material whose porosity is y, Km and Gm become K*(y) and G*(y) before adding, respectively, KKT* and GKT* become K*(y + dy) and G*(y + dy) after adding, respectively, P*i and Q*i become P*i and Q*i which describe the effect of the ith inclusion in an effective medium *, in Eq.(1). So Eq.(1)can be rewritten as

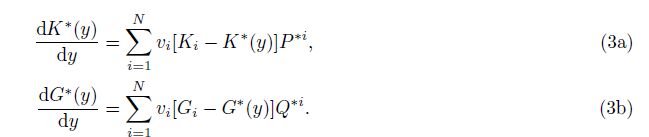

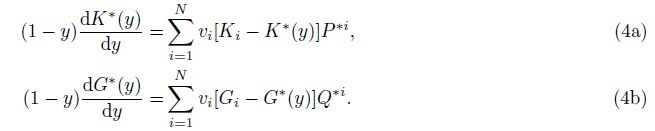

Because dy [ \ll \] 1 in Eq.(2), we have $\frac{{3{K^*}(y)+ 4{G^*}(y)}}{{3{K^*}(y + dy)+ 4{G^*}(y)}} \approx 1$, $\frac{{3{G^*}(y)+ 4{\xi ^*}(y)}}{{3{G^*}(y + dy)+ 4{\xi ^*}(y)}} \approx 1$ Letting dK*(y) = K*(y + dy)- K*(y), dG*(y)= G*(y + dy)- G*(y) and dividing both sides of Eq.(2)by the dy, we obtain

In general the effective differential Eqs.(4a) and (4b)are also coupled, as these two equations depend on both the bulk and shear moduli of the composite. Therefore, it is difficult to obtain the analytical formulae of the bulk and shear moduli for dry rock by integrating the DEM equations.

First we give a comparison between the analytical formulae and numerical results of the differential Eqs.(3) and (4). We take quartz as the host medium, let Km = 37 GPa and Gm = 44 GPa. There are three pore shapes in the rock, and their pore aspect ratios α are 1.0, 0.5 and 0.01 respectively, and their volume percentages are 98.99%, 1% and 0.01% respectively, in order to meet the requirement that the ratio of porosity to aspect ratio has to be much smaller than 1 for each inclusion in Kuster and Toksöz theory(Kuster and Toks&vouml;z, 1974). We use the fourth-order Runge-Kutta scheme to get numerical solutions of the differential Eqs.(3) and (4), the step size used in numerical integration is set to △y = 0.1. We assume that there are two different materials in the cavities, one is solid inclusions and the other is dry void. The elastic moduli of solid inclusions are Ki = 14 GPa and Gi = 10 GPa, while those of dry voids are set to 0. We show comparisons of the analytical and numerical results for two versions of differential equations in Fig. 1, and pink points represent the numerical results of Eq.(3), blue points represent the numerical results of Eq.(4). Furthermore, we give the theoretical estimation of Kuster-Toksöz theory which is displayed in black points and the Hashin-Shtrikman bounds which are displayed in red lines. Figs. 1a and 1b show the comparisons of the bulk and shear moduli for solid inclusions, and Figs. 1c and 1d show the comparisons of the bulk and shear moduli for dry voids. The results show that the theoretical estimation of Kuster-Toksöz theory and the upper Hashin-Shtrikman bound are identical, the numerical results of Eq.(3)are close to Kuster-Toksöz theory when the porosity is low, but as the porosity increases the difference between them increases and the numerical results of Eq.(3)violate the Hashin-Shtrikman upper bound and have no physical meaning. Thus Eq.(3)can only be used to simulate the elastic properties of multiple-porosity rock when the porosity is low, while Eq.(4)is always within the Hashin-Shtrikman bounds. As Eq.(3)is in conflict with the Hashin-Shtrikman bounds when the porosity is high, we only use Eq.(4)to calculate the effective moduli of multiple-porosity rock.

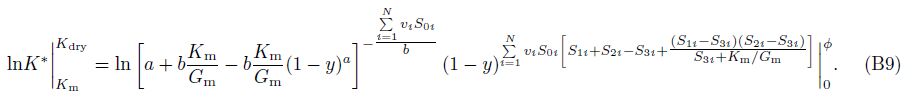

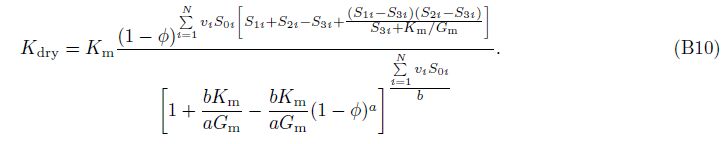

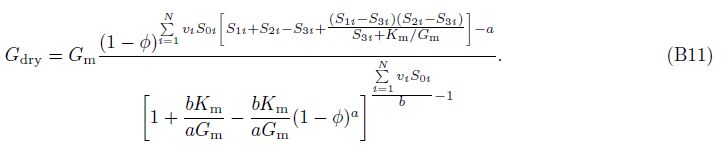

3 DEM ANALYTICAL FORMULAE FOR DRY MULTIPLE-POROSITY ROCKFor dry rock, the elastic moduli of the ith inclusion Ki = 0 and Gi = 0(1 ≤ i ≤ N), Eq.(4)becomes

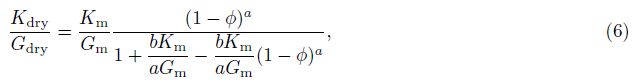

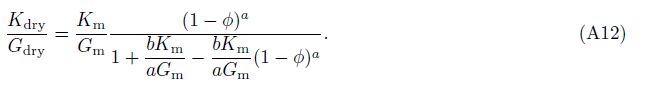

In order to decouple the equations for bulk and shear moduli, substituting Eq.(6)into(5a), and then, integrating it from y = 0 to φ gives directly the analytical results for Kdry, and then, dividing the Kdry by Eq.(6)gives the corresponding analytical results for Gdry, we have(see Appendix B)

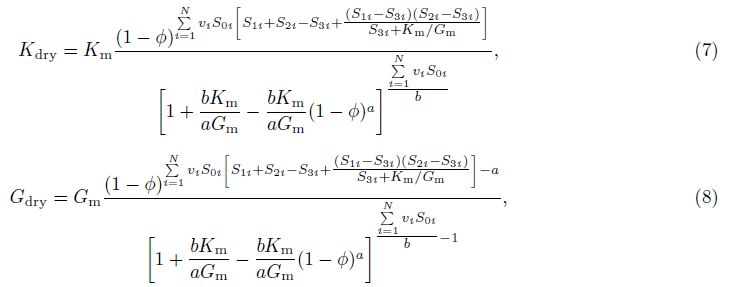

αi is the pore aspect ratio of the ith ellipsoidal inclusion.

4 THEORETICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL EXAMPLES

αi is the pore aspect ratio of the ith ellipsoidal inclusion.

4 THEORETICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL EXAMPLESEqs.(7) and (8)can be used to study effective elastic properties of dry rocks with two or more kinds of pore shapes. Most current studies focus on the double-porosity rock(Xu and White, 1995). For convenience of comparison, we here also conduct the theoretical and laboratory data analysis by using the analytical formulae of bulk and shear moduli for dry double-porosity rock.

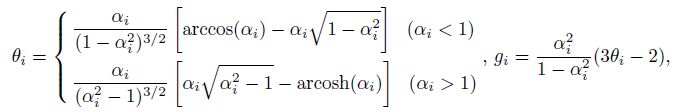

First we give a comparison between the analytical formulae and numerical results of the differential equations. We take quartz as the host medium, let Km = 37 GPa and Gm = 44 GPa respectively which is the same as Fig. 1. There are two kinds of pore types, one represents pore and the other represents crack, and their pore aspect ratios α are 0.15 and 0.005 respectively.

|

The bulk (a) and shear (b) moduli for solid inclusions. The bulk (c) and shear (d) moduli for dry-inclusions. Fig.1 Comparison of the numerical solutions of the DEM equations and Kuster-Toks¨oz estimates for porous rock |

To characterize the effect of different pores or cracks on the elastic properties of rock, we give three different volume percentages of pores and cracks, which are(90%, 10%), (50%, 50%) and (10%, 90%)respectively. We also use the fourth-order Runge-Kutta scheme to get numerical solutions of the differential Eq.(5). Fig. 2 shows the comparisons of the analytical and numerical results, in which points represent the numerical results, solid line represents the analytical results calculated by Eqs.(7) and (8)whose constant b is simply set to the first derivative of the difference between the polarization factors when K*/G* = Km/Gm = 1.1892 and constant a can be then calculated from P*i - Q*i = a + bK*(y)/G*(y)(see Appendix A). The results show that the analytical results of bulk and shear moduli are in sufficiently good agreement with the numerical results in three different volume percentages of pores and cracks. As the volume percentage of cracks increases, the effective elastic moduli of the rock decrease, and the decrease rate of the effective moduli as the volume percentage of cracks increases from 10% to 50% is substantially larger than that as the volume percentage of cracks increases from 50% to 90%.

|

Fig.2 Comparison of the numerical and analytical solutions of dry-rock bulk (a) and shear (b) moduli for dual-porosity rock with different pore volume percentages |

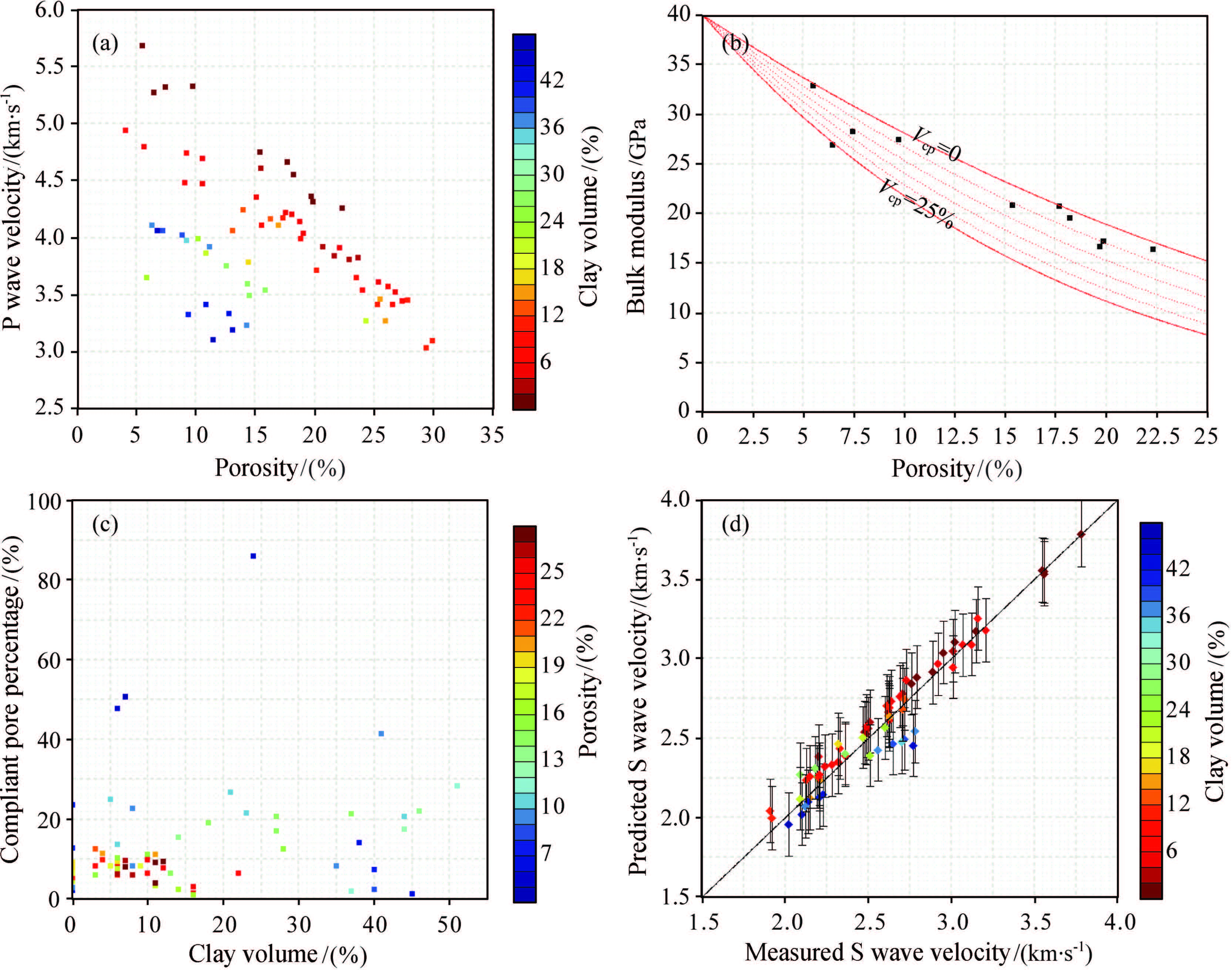

We use 69 dry s and stone data of Han(1986)to analyze the predictions of the analytical formulae. The data were obtained by measuring wave velocities in dry-rock samples at confining pressure 40 MPa and ultrasonic frequency 1 MHz and 0.6 MHz respectively. The porosity of these samples ranges from 5% to 30%, and the clay content range in these samples is between 0 and 50%. Fig. 3a shows the relation between porosity and P-wave velocities of Han’s dry s and stone data. The measured results indicate that P-wave velocities of dry s and stone decrease as porosity or clay content increases. The bulk and shear moduli of quartz used in the analysis were taken to be 40 GPa and 43.7 GPa, respectively. The bulk and shear moduli of clay were taken to be 20.9 GPa and 6.85 GPa, respectively. We use the double-porosity DEM analytical formulae to calculate the elastic properties of s and stone data, in which the pore aspect ratios of stiff pores and soft pores are 0.18 and 0.04, respectively. It needs the volume percentages of two different kinds of pores to predict the elastic moduli with porosity using Eqs.(7) and (8). Fig. 3b shows the variations of the bulk moduli of 10 dry clay-free s and stones with porosity in different pore volume percentages. We can see that when the volume percentages of soft pores Vcp = 0 there are only two points on the predicted line. And the point(porosity is 6%)is far away from the predicted line, when the volume percentage of soft pores increases to Vcp = 25%, the predicted line is in agreement with that point. It shows that there is only two points having no soft pores, while the other eight points having both stiff and soft pores to varying growth levels.

|

(a) P wave versus porosity for experimental data; (b) Bulk modulus versus porosity for 10 samples of clean sandstone and the theoretical predictions; (c) The estimated compliant pore volume percentage versus clay volume; (d) Comparison of S wave velocities between the experimental result and the theoretical calculation from the estimated pore volume percentage. Fig.3 Result analysis of the experimental sandstone data measured by Han (1986) and theoretical estimations of the DEM analytical formulae for dual-porosity rock |

We estimate the volume percentage of soft pores by minimizing the error between theoretical predictions by Eqs.(7) and (8) and experimental measurements. Fig. 3c shows the relationship between the inverted volume percentages of soft pores and clay content. In general, the porosity of the rock is larger, the volume percentage of soft pores is smaller, but the volume percentage of soft pores is not significantly correlated with clay content. We obtain the shear wave velocity from the inverted volume percentages of soft pores by Eqs.(7) and (8). Fig. 3c shows the comparison between the predicted and measured shear wave velocities, and the error bars with 95% confidence interval are shown. Observe that for the majority of samples the analytical formulae are in good agreement with the measured data, and it shows that the pore structure of s and stone can be characterized by the double-porosity DEM analytical model.

5 CONCLUSIONSBy applying the Kuster-Toksöz theory this paper established the differential equations of both Zimmermann’s and Norris’s versions for multiple-porosity rock, and derived analytical solutions of the bulk and shear moduli for dry rock from the differential equations of Norris’s version. The analytical formulae are functions of the bulk and shear moduli of the mineral grain, porosity, pore volume percentage and pore geometry. The pore geometry is characterized by a linear relation whose intercept a and gradient b might be approximately calculated from the difference between the effective polarization factors and its first derivative where the effective modulus ratio is equal to the mineral grain modulus ratio.

The differential effective medium model of multiple-porosity rock avoids the problem that the estimated elastic properties depend on the adding order of different pore-type inclusions when the classical DEM equations are used for multiple-porosity rock. When the porosity type is single, the multiple-porosity DEM equations become the classical DEM equations.

Numerical results show that the elastic moduli predicted by the DEM equations of Norris’s version never violate Hashin-Shtrikman bounds while those predicted by the DEM equations of Zimmermann’s version violate bounds in some cases, so the latter can only be used to predict the elastic moduli for the porous rock with very low porosity.

Theoretical models and laboratory data tests show that the predictions of the analytical formulae are in good agreement with the numerical solutions of the full DEM equation. The DEM analytical formulae for multiple-porosity rock can accurately predict the variations of elastic moduli with porosity. The dual-porosity DEM analytical model can be used to invert for the pore volume percentages of both cracks and pores by minimizing the error between theoretical predictions and experimental measurements. The inversion results for the s and stone experimental data show that there is no direct correlation between the crack volume percentage and clay volume.

6 Appendix A Derivation of the Dry Rock Modulus Ratio of Multiple-Porosity RockHere we first define the effective polarization factor, which is the sum of the polarization factors weighted by their volumes of the pores contained in the medium, i.e.

Subtracting Eq.(A4)from Eq.(A3)yields

Substituting Eq.(A7)into Eq.(A5)yields

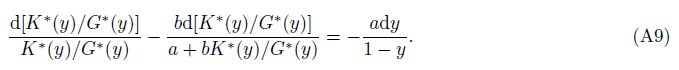

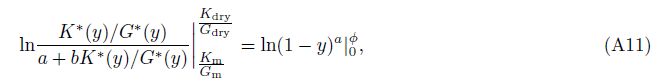

Furthermore, Eq.(A8)is decomposed into

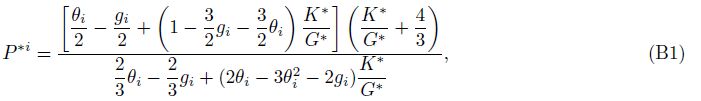

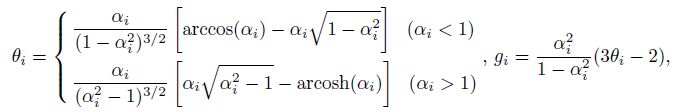

According to the appendix A shown in Li and Zhang’spaper(2011), for dry spheroidal void the polarization factor of the ith pore of multiple-porosity rock is

αi is the pore aspect ratio of the ith spheroidal void.

αi is the pore aspect ratio of the ith spheroidal void.

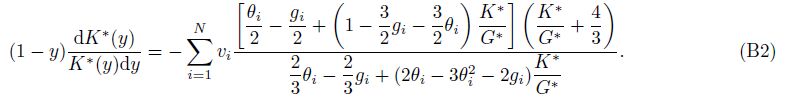

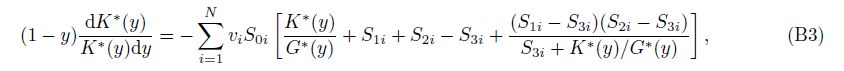

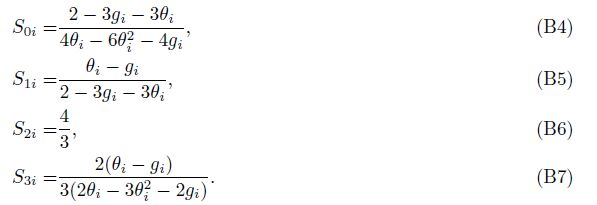

From Eqs.(5a) and (B1)we obtain

Thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for many insightful comments and suggestions that improve this paper. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(41404088) and the Important National Science and Technology Specific Projects of China(2011ZX05001).

| [1] | Baechle G T, Colpaert A, Eberli G P, et al. 2008. Effects of microporosity on sonic velocity in carbonate rocks. The Leading Edge, 27(8):1012-1018. |

| [2] | Berryman J G. 1980. Long-wavelength propagation in composite elastic media Ⅱ. Ellipsoidal inclusions. J. Acoust. Soc.Am., 68(6):1820-1831. |

| [3] | Berryman J G, Berge P A. 1996. Critique of two explicit schemes for estimating elastic properties of multiphase composites.Mech. Materials, 22(2):149-164. |

| [4] | Berryman J G, Pride S R, Wang H F. 2002. A differential scheme for elastic properties of rocks with dry or saturated cracks. Geophys. J. Int., 151(2):597-611. |

| [5] | Han D H, Nur A, Morgan D. 1986. Effects of porosity and Clay content on wave velocities in sandstones. Geophysics, 51(11):2093-2107. |

| [6] | Keys R G, Xu S Y. 2002. An approximation for the Xu-White velocity model. Geophysics, 67(5):1406-1414. |

| [7] | Kuster G T, Toksöz M N. 1974. Velocity and attenuation of seismic waves in two media, Part I. Theoretical considerations.Geophysics, 39(5):587-606. |

| [8] | Li H B, Zhang J J. 2010. Modulus ratio of dry rock based on differential effective-medium theory. Geophysics, 75(2):N43-N50. |

| [9] | Li H B, Zhang J J. 2011. Elastic moduli of dry rocks containing spheroidal pores based on differential effective medium theory. J. Appl. Geophys., 75(4):671-678. |

| [10] | Li H B, Zhang J J. 2012. Analytical approximations of bulk and shear moduli for dry rock based on the differential effective medium theory. Geophys. Prospect., 60(2):281-292. |

| [11] | Li H B, Zhang J J, Yao F C. 2013. Inversion of effective pore aspect ratios for porous rocks and its applications. Chinese J. Geophys. (in Chinese), 56(2):608-615. |

| [12] | Mavko G, Mukerji T, Dvorkin J. 1998. The Rock Physics Handbook:Tools for Seismic Analysis in Porous Media. New York:Cambridge University Press. |

| [13] | Norris A N. 1985. A differential scheme for the effective moduli of composites. Mech. Materials, 4(1):1-16. |

| [14] | Sayers C M. 2008. The elastic properties of carbonates. The Leading Edge, 27(8):1020-1024. |

| [15] | Xu S Y, Payne M A. 2009. Modeling elastic properties in carbonate rocks. The Leading Edge, 28(1):66-74. |

| [16] | Xu S Y, White R E. 1995. A new velocity model for clay-sand mixtures. Geophys. Prospect., 43(1):91-118. |

| [17] | Zimmerman R W. 1984. Elastic moduli of a solid with spherical pores:new self-consistent method. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences & Geomechanics Abstracts, 21(6):339-343. |

| [18] | Zimmerman R W. 1985. The effect of microcracks on the elastic moduli of brittle materials. J. Mater. Sci. Lett., 4(12):1457-1460. |

| [19] | Zimmerman R W. 1991. Elastic moduli of a solid containing spherical inclusions. Mech. Materials, 12(1):17-24. |

2014, Vol. 57

2014, Vol. 57