2. 江大学 工程师学院 动力工程中心, 浙江 杭州 310015;

3. 浙江新安江集团股份有限公司, 浙江 杭州 311600;

4. 杭州博盛环保科技有限公司, 浙江 杭州 310014;

5. 杭州澳赛诺生物科技有限公司, 浙江 杭州 311604

2. Technology Innovation and Training Center, Polytechnic Institute, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310015, China;

3. Zhejiang Xinan Chemical Industrial Group CO. Ltd., Hangzhou 311600, China;

4. Hangzhou BoSheng Environmental Technology Co. Ltd., Hangzhou 310014, China;

5. Hangzhou Allsino Chemicals Company, Hangzhou 311604, China

石油化工行业排放的挥发性有机化合物(volatile organic compounds, VOCs)是臭氧和pM2.5污染的前体物之一,其自身的毒性也严重危及大气环境和大众健康[1]。石化行业排放的废气往往是一种复杂的混合物,包括恶臭的含硫化合物和苯、甲苯、乙苯和二甲苯(benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene and xylenen, BTEX)等。生物技术在VOCs去除方面拥有良好的成本效益和环境友好性而受到广泛应用[2-5]。其中,生物滴滤(biotrickling filter,BTF)系统至今仍具有最高的VOC生物降解运行成本比[6-9]。然而,目前的研究仅报道了BTF系统中去除含硫VOCs或BTEX化合物。CÁCERES等10]报道了利用接种了Thiobacillus thioparus纯菌的BTF去除H2S、二甲基硫醚,二甲基二硫醚和甲硫醇[。HU等[11]利用接种了Zoogloea resiniphila HJ1和Rhodesianum H13的BTF进行甲苯、邻二甲苯和二氯甲烷的处理。而接种特定的VOCs降解菌种同时去除石油化工行业排放的含硫VOCs和BTEX的研究鲜有报道。此外,许多报道表明微生物与生物反应器中VOCs的宏观生物降解有着密切但不明确的关系:LI等[12]通过聚合酶链反应-变性梯度凝胶电泳(PCR-DGGE),发现Marinobacter,Prolixibacter,Balneola,Zunongwangia,Halobacillus是BTEX降解的主要菌属。WAN等[13]利用16S rRNA基因测序和系统发育分析来证实Lysinibacillus sphaericus RG-1的乙硫醇(ethyl mercaptan,EM)生物降解性。然而,关于BTF体系中含硫VOCs和BTEX降解过程的微生物群落的动态变化研究仍然空缺。

作者之前的研究中,Pandoraea sp. WL1和Pseudomonas sp. WL2被证明分别具有高效降解对二甲苯和EM的能力[14-15]。在本研究中,将上述菌株的混合培养物接种入BTF中,用于同时去除恶臭硫醇和BTEX。通过构建16S rRNA基因克隆文库,分析从初始阶段到稳态运行的微生物群落结构和多样性变化,为生物技术处理含硫VOCs和BTEX提供相关的理论参考。

2 实验材料和方法 2.1 实验药剂与培养基本研究中,EM和丙硫醇(propyl mercaptan,PM)作为恶臭硫醇类模拟污染物,购自阿拉丁试剂(上海)有限公司。甲苯和对二甲苯作为BTEX类模拟污染物,购自上海国药集团化学试剂有限公司。所用药品均为分析纯。

用于BTF系统中微生物富集和液体循环的矿物盐培养基(mineral salts medium,MSM)每升无菌去离子水含有:2.5 g (NH4)2SO4,0.1 g MgCl2·6H2O,0.01 g EDTA,0.002 g ZnSO4·7H2O,0.001 g CaCl2·2H2O,0.005 g FeSO4·7H2O,0.000 2 g Na2MoO4·2H2O,0.000 2 g CuSO4·5H2O,0.000 4 g CoCl2·6H2O,0.001 g MnCl2·4H2O,1.6 g K2HPO4和0.8 g NaH2PO4·2H2O[16]。配制好的培养基近似中性(pH = 6.6)。上述所有化学试剂均为分析纯,购自上海国药集团化学试剂有限公司。

2.2 接种菌将近似浓度的50 mL BTEX降解细菌溶液(Pandoraea sp.WL1)和EM降解细菌溶液(Pseudomonas sp. WL2)与100 mL新鲜MSM在630 mL无菌血清瓶中混合并密封,在30℃下以180 r·min-1转速恒温震荡,并连续供应50 mg·L-1的EM和对二甲苯进行驯化。当生物质浓度增加至50 mg干细胞重量(DCW)L-1时,将菌液接种至BTF中。

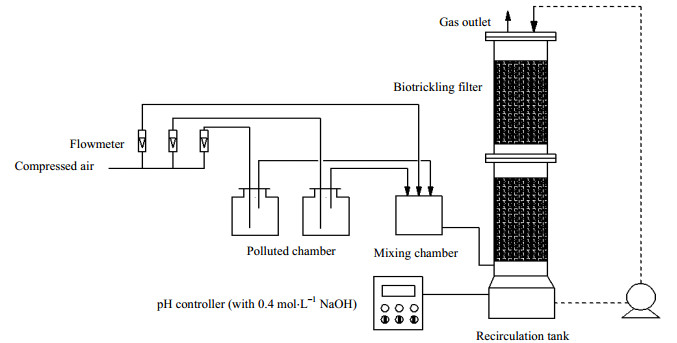

2.3 实验装置实验所用的BTF系统如图 1所示。滴滤塔身总高度为0.65 m,添加共计3.5 L的组合生物填料(授权专利号:ZL201210146421.6)。BTF拥有两层填料层(记为上层和下层),以研究BTF不同填料高度微生物群落的变化和分布。模拟废气从挥发瓶中鼓吹出来,与新鲜空气在混合室中混合后调节浓度,从BTF的底部进入。模拟废气经过填料层,与从塔顶喷淋的MSM形成对流。MSM循环液流速为12.0 L·h-1。进气量恒定为0.4 m3·h-1,对应的停留时间(empty bed residence time,EBRT)为28.3 s。BTF系统的温度保持在(29±1) ℃。利用pH自动调节装置,体系pH值维持在7.0±0.2。

|

图 1 各实验阶段BTF的运行参数 Fig.1 Operation conditions of each experimental procedures in the BTF |

实验过程中BTF系统共运行94 d,其中初始阶段23 d,稳态运行71 d。稳态运行分为6个阶段(阶段I~VI),分别研究处理EM(阶段I)、PM(阶段II)、对二甲苯(阶段III)和甲苯(阶段IV)、EM和对二甲苯混合VOCs(阶段V),以及EM、PM、对二甲苯和甲苯4组分混合VOCs(阶段VI)的去除情况。在整个实验过程中,每天测量3次BTF的进气口和出气口VOCs浓度,每次测量间隔为4 h。每次测量至少注入气相色谱仪3次,结果取算术平均值。各实验阶段VOCs的进气浓度和总进气负荷如表 1所示。

|

|

表 1 各实验阶段BTF的运行参数 Table 1 Operation conditions of each experimental procedures in the BTF |

VOCs浓度使用气相色谱测量。使用1 000 μL玻璃注射器从进气口和出气口对气体样品进行取样。然后使用气相色谱仪(GC9790,浙江福立仪器股份有限公司)用熔融石英毛细管柱(30 m×0.32 mm×0.33 μm)和火焰离子化检测器(FID)定量分析样品。使用氮气作为载气,流量为30 mL·min-1。进样口、烘箱和检测器的温度分别设定为180,180和200 ℃。

2.6 动力学模型BTF的宏观动力学通常使用如下所示的改进的Michaelis-Menten模型表述[17]:

| $ {\rm{EC = }}\frac{{{\rm{E}}{{\rm{C}}_{\max }}{C_{\ln }}}}{{{K_{\rm{S}}} + {C_{\ln }}}} $ | (1) |

其中Cln=[(Cin-Cout)/ln(Cin/Cout)]。当底物抑制微生物时,宏观动力学可以通过添加抑制常数Ki(g·m-3)的Haldane-Andrews方程来表示[18]:

| $ {\rm{EC = }}\frac{{{\rm{E}}{{\rm{C}}_{\max }}{C_{\ln }}}}{{{K_{\rm{S}}} + {C_{\ln }} + C_{\ln }^2/{K_{\rm{i}}}}} $ | (2) |

为研究对二甲苯和EM的降解菌Pandoraea sp. WL1和Pseudomonas sp. WL2的微生物群落变化情况。在接种初期和BTF稳定运行时(第64 d),从生物反应器填料上层和下层中收集微生物样品。用通用引物27F和1492R提取总DNA,构建16S rRNA基因克隆文库[19]。

同时,利用香农指数表示微生物群落多样性,计算如下:

| $ H = - \sum\limits_{i = 1}^S {{P_i}\ln ({P_i})} $ | (3) |

其中Pi是菌种i的比例丰度,S是体系中的菌种数。

使用GenBank数据库中的BLAST程序对16S rRNA基因序列进行识别,并获取其菌属、菌种的分类学位置,置信水平为99%。Clustal X(V 1.83)用于多组16S rRNA序列比对。利用MEGA软件(V 5.0)构建从初始接种到稳定运行阶段的BTF体系生物膜的系统发育树。

在本研究中提取克隆的16S rRNA序列在GenBank数据库中的登记序号为KY082011-KY082038。

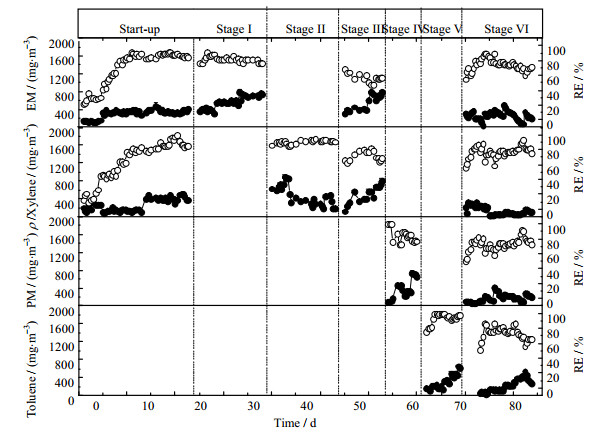

3 结果与讨论 3.1 BTF的去除效果接种驯化后的BTEX和硫醇降解菌后,BTF进入初始阶段,VOCs去除情况如图 2所示。初始阶段的前4 d,当EM和对二甲苯的进气浓度为116~168 mg·m-3的和99~308 mg·m-3时,BTF对EM和对二甲苯的去除效率(removal efficiency, RE)较低,分别在40%和30%以下。第5 d开始,EM和二氯甲烷的去除效率开始明显上升,到第10 d为止去除效率均逐渐增加到80%并且在后续的第10~23 d保持在80%~90%,表明BTF系统已经进入稳定运行状态。

|

图 2 BTF对EM、PM、对二甲苯和甲苯的去除性能 Fig.2 Time courses of removal performance for EM, PM, p-xylene and toluene by the BTF ● inlet concentration, mg·m-1 ○ removal efficiency, % |

初始阶段的结果表明接种了特定降解菌后,BTF体系可以在10 d内达到稳定状态。YANG等报道,装填有聚氨酯海绵规整填料或立方堆积填料的BTF可有效去除甲苯,但启动时间较长(规整填料为19 d,立方堆积为27 d)[20]。SERCU等使用Hyphomicrobium VS接种菌来提高BTF对二甲基硫醚的去除效果,经过16 d的驯化期后,获得了超过90%的去除效率[21]。由于高效降解接种菌的使用,本研究中BTF的初始驯化阶段大大缩短。

初始阶段后,考察了该BTF体系对EM和对二甲苯的去除性能。在阶段I,EM进气浓度为304~802 mg·m-3,去除效率达到75%~90%,对应的去除能力(elimination capacity, EC)为34.1~79.3 g·m-3·h-1。在阶段II,当对二甲苯浓度在181~900 mg·m-3之间变化时,其去除能力均保持在90%左右,对应的去除能力为20.8~104.1 g·m-3·h-1。在阶段III,对二甲苯和EM混合通入BTF中,总VOCs浓度为430~1598 mg·m-3。此时EM和对二甲苯的去除效率分别降至47%~67%和77%~89%。相对地,EM和对二甲苯的最大去除能力分别为57.0 g·m-3·h-1和71.0 g·m-3·h-1。

经过PM和甲苯的适应过程(IV,V阶段)后,在第VI阶段(第80~94 d)考察了该BTF体系对EM、PM、对二甲苯和甲苯VOCs混合去除的表现。对于总进气浓度为425~1321 mg·m-3的混合VOCs (EM 41~509 mg·m-3,PM 41~509 mg·m-3,甲苯37~529 mg·m-3,对二甲苯42~326 mg·m-3),BTF系统能够稳定去除且4种污染物的去除效率分别为EM (77±8)%,PM (73±8)%,甲苯(74±9)%,对二甲苯(74±8)%。

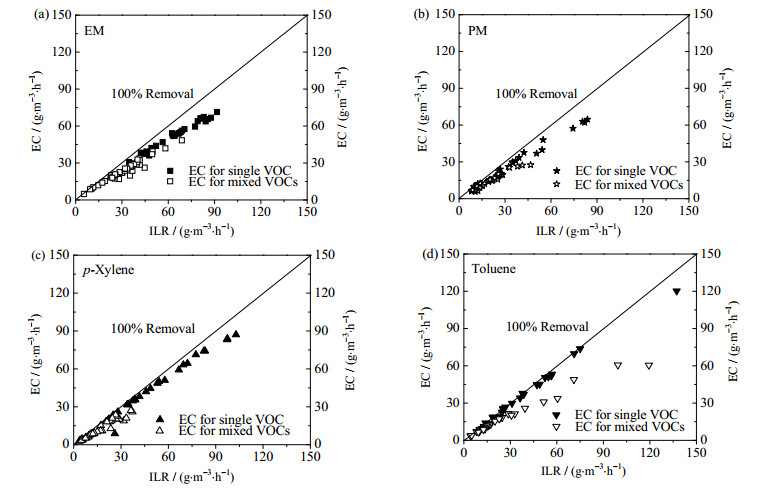

3.2 单一和混合组分VOCs去除能力考虑到石油化工行业废气排放中广泛存在的PM、甲苯及其他多种有机污染物,研究多种混合组分VOCs的去除能力极为重要。如图 3所示,当去除单一底物时,EM、PM、甲苯和对二甲苯的去除能力分别为30.7~71.3,9.6~64.6,8.7~87.0和10.4~120.3 g·m-3·h-1,对应的进气负荷(inlet loading rate, ILR)分别为34.7~91.6,9.6~83.8,12.9~102.8和13.0~137.3 g·m-3·h-1。单一底物的去除效率接近100%的去除线。当处理多种VOCs时,在进气负荷达到30.0 g·m-3·h-1前,两种硫醇的去除能力与单一底物的去除差别不大。而当进气负荷达到25.0 g·m-3·h-1时,混合VOCs中的对二甲苯和甲苯的去除能力就开始明显偏离单一底物时的去除能力。混合组分去除时,EM、PM、对二甲苯和甲苯的最大去除能力分别为48.4,27.5,27.1和60.7 g·m-3·h-1。然而,随着进气负荷的增加,混合VOCs的去除能力曲线并未完全平坦。这表明在进气浓度0~500 g·m-3·h-1,这些底物的进气负荷较低,未能使该BTF体系达到理论的最大去除能力,其去除能力还存在进一步提高的空间。

|

图 3 单一VOC与混合VOCs的去除能力比较 Fig.3 Comparison of EC for single VOC and mixed VOCs of EM, PM, p-xylene and toluene |

值得注意的是,当进气负荷控制在53.6~168.1 g·m-3·h-1时,多组分混合VOCs的总去除能力为33.1 ~110.1 g·m-3·h-1,维持在相对较高的水平并。WAN等利用接种Lysinibacillus sphaericus RG-1的BTF去除1.05 mg·L-1单一EM,最大去除能力为56.2 g·m-3·h-1[22]。JIMÉNEZ等报道,在BTF中停留时间为30 s时,甲苯的最大去除能力为99 g·m-3·h-1[23]。由于接种时使用的BTEX降解菌株和硫醇降解菌株对各种VOCs均具有良好的底物降解范围[14-15],因此与其他研究相比,本研究的BTF中硫醇、BTEX和总去除能力均具有相对较好的表现。

3.3 动力学分析Haldane-Andrews模型使用非线性曲线拟合求解,相应的拟合结果总结在表 2中。在拟合的过程中,4种底物的抑制常数Ki的大小在1014~1025数量级,表明在本研究的进气负荷内,EM、PM、对二甲苯和甲苯的降解过程几乎不受竞争性抑制。在这种情况下,该模型的方程与无抑制常数的Michaelis-Menten模型近似[17],因此表 2中的饱和elis-Menten模型列出。

|

|

表 2 硫醇和BTEX生物降解过程宏观动力学参数 Table 2 Macro-kinetics parameters for mercaptans and BTEX biodegradation in the BTF |

模型拟合和结果表明,单一底物去除时,BETX的ECmax值(对二甲苯为304.5 g·m-3·h-1,甲苯为331.4 g·m-3·h-1)高于硫醇(EM为174.6 g g·m-3·h-1,PM为161.0 g·m-3·h-1)。这是由于含硫VOCs比芳香烃更难生物降解。在多组分混合VOCs去除中,对二甲苯的ECmax显著低于甲苯(对二甲苯为65.0 g·m-3·h-1,甲苯为122.2 g·m-3·h-1)。这同样是由于相比于对二甲苯,甲苯更容易被微生物利用,因此在降解混合底物时反应器中的微生物倾向于优先利用甲苯。这与GALLASTEGUI等[24]的研究结果一致。

同时,单一EM、PM、对二甲苯和甲苯去除的饱和常数KS值分别为0.560,0.550,0.870和0.768 g·m-3·h-1,而混合VOCs去除时上述底物的KS值分别为0.378,0.337,0.286和0.633 g·m-3·h-1,单一VOC去除的饱和常数KS略高于混合VOCs中的饱和常数。如先前研究中所述,KS表示当达到最大去除速率的一半时底物的浓度,因此KS值越低,相对应的目标底物和细菌酶之间的亲和力越高,并且有利于降解过程[17]。混合VOCs进样过程中的KS值低于单一VOC进样,表明在硫醇和BTEX中可能一定的共降解机制,这一机制还有待进一步证实。

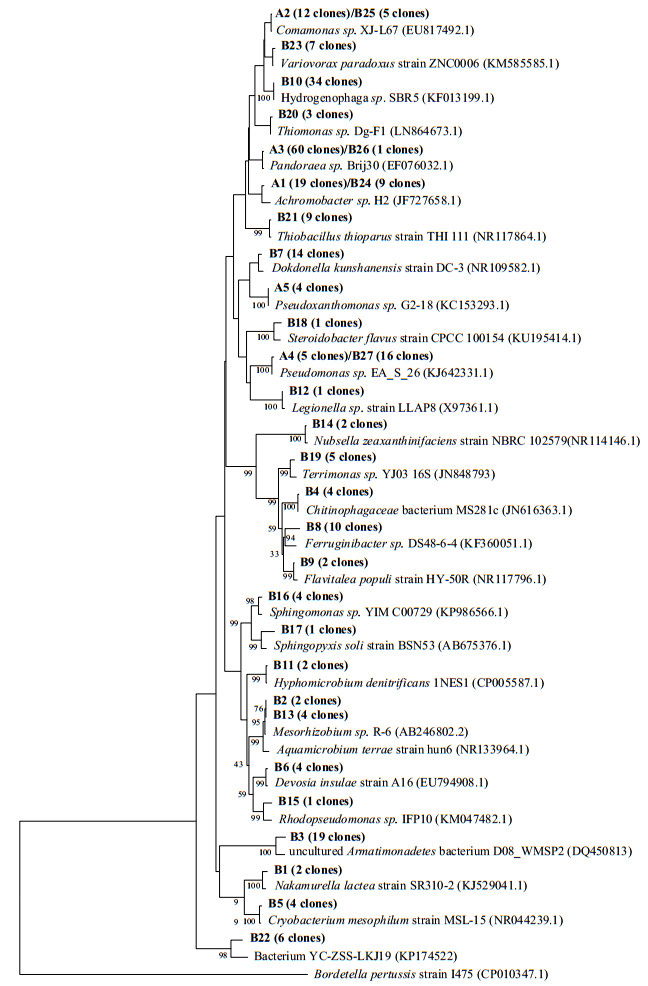

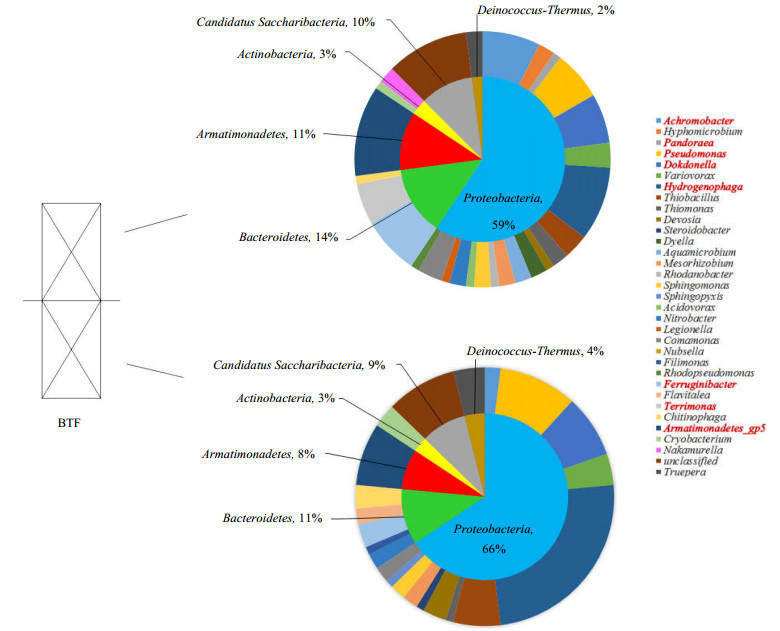

3.4 微生物群落分析在长时间运行后,分别从BTF上层和下层填料层取下生物膜,获得约96和102条16S rRNA克隆基因,并从初始接种的菌种样品中取得100条16S rRNA克隆基因,在GenBank数据库中将其与其他报道的16S rRNA序列比对,构建系统发育树,如图 4所示。香农指数的大小反应了微生物的多样性的高低,上层、下层和初始接种的香农指数分别为3.02,2.67和1.16。结果表明,填料层上层的微生物群落的多样性最高,下层较低,而初始接种最低。

|

图 4 初始接种菌的系统发育树 Fig.4 Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree from the pre-isolated strains 16S rRNA clone gene for inoculum and biofilm samples were named as A1-A5 and B1-B23, respectively. The scale bar represents 0.1 substitutions per nucleotide position. Bordetella pertussis strain I475 (CP010347.1) was used as outgroup |

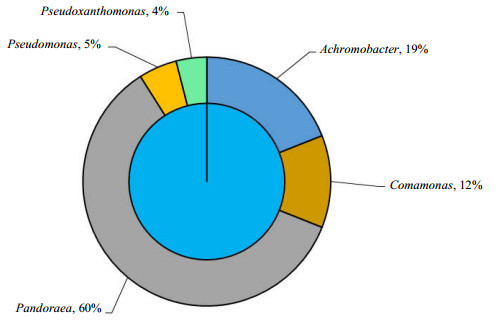

初始接种的菌株中检测到5个菌属,包括19.0% (19条克隆)的Achromobacter(A1),12.0% (12条克隆)的Comamonas(A2),60.0% (60条克隆)的Pandoraea(A3),5.0% (5条克隆)的Pseudomonas (A4),4.0% (4条克隆)的Pseudoxanthomonas (A5),如图 5所示。这表明Pandoraea sp. WL1和Pseudomonas sp. WL2菌株在混合并经过一段时间混合底物环境的驯化后,已经演化出了不同的菌属。属于Betaproteobacteria纲的Pandoraea,Achromobacter和Comamonas菌属在接种物中占91%,而Gammaproteobacteria纲(Pseudomonas和Pseudoxanthomonas菌属)仅占9%。这一结果表明Pandoraea sp.能够适应高EM和对二甲苯浓度的环境,并以悬浮态形式存在,而Pseudomonas sp.在这种环境中逐渐减少。

|

图 5 初始接种菌属的16S rRNA基因序列相对丰度 Fig.5 Relative abundance of the cloned 16S rRNA gene sequences from bacterial strains for the inoculum |

将初始菌株接种入BTF中并运行64d后,在BTF的填料层上层和下层分别分离出了27种和21种菌属,如图 6所示。其中,Achromobacter (9条克隆),Armatimonadetes_gp5 (19条克隆),Dokdonella (14条克隆),Ferruginibacter (10个克隆),Hydrogenophaga (34条克隆),Pseudomonas (16条克隆),Thiobacillus (9条克隆),Truepera (6条克隆)和Variovorax (7条克隆)为主要菌属,占198条克隆序列的62.6%。在填料层上层生物膜中,Achromobacter,Hydrogenophaga,Pseudomonas,Dokdonella,Ferruginibacter和Armatimonadetes_gp5占相对较高的比例(5.9%~10.9%)。在填料层下层生物膜中,Hydrogenophaga成为优势属,占24.04%。Pseudomonas和Armatimonadetes_gp5的下层相对丰度也较高,分别为9.6%和7.7%。然而,在初始菌种中的优势菌属Pandoraea在BTF的上层和下层占0.5%和0.0%,失去了其优势地位。

在BTF中,与初始接种相比,Pseudomonas sp.的比例显著增加,在填料层上层和下层的生物膜中相对丰度分别为5.9%和9.6%。在作者以前的研究中曾报道过Pseudomonas sp. WL2具有高效降解EM和二乙基二硫醚能力[15]。同时,Pseudomonas属也是BTEX最常见的生物降解菌之一,在BTEX降解群落中,均能保持一定比例的存在[25-26]。广泛的适应性可能使其在一定程度上兼顾了硫醇及BTEX的降解。在初始接种中,Hydrogenophaga尚不存在,而在运行一段时间后,该属的序列在总微生物群落中占17.2%,它被证实具有降解芳香烃的能力和氧化硫元素的能力[27-29]。从图 4可知,Hydrogenophaga离初始接种菌属中的Pandoraea距离最为接近,在反应器稳定运行后,伴随着Pandoraea sp.在微生物群落中优势地位的丧失,Hydrogenophaga成为了优势菌属,其可能是由Pandoraea演化而来[29]。此外,Hydrogenophaga能与Pseudomonas共同存在并一同降解苯、甲苯、二甲苯[30]。相比于Pandoraea对Pseudomonas的抑制作用,Hydrogenophaga的存在更有利于微生物群落结构的稳定性。因此在菌种接种时,除了其降解能力的高效性,不同菌种间的群落稳定性也需考虑。

表 3列举了其他研究中用于去除含硫VOCs和BTEX的降解菌。在本研究的BTF体系中,BTEX降解菌在微生物群落中占主导地位,而硫醇降解菌比例较少,这可以解释同时去除对二甲苯和EM二组分混合VOCs时,EM去除效率的迅速下降的情况(图 2)。

|

|

表 3 其他研究中的含硫VOCs和BTEX降解菌 Table 3 Bacterial strains for degrading sulfur-containing VOCs and BTEX in literature |

具有BTEX降解能力的菌株(Hydrogenophaga和Pseudomonas)在下层填料层具有更高的相对丰度(图 6)。同时,下层填料层中的Thiobacillus属的相对丰度(5.9%)也比上层(3.1%)高得多。这种菌属在生物过滤处理含硫VOCs,例如甲硫醇、二甲基硫醚、二甲基二硫醚等较为常见[31]。这是由于在进气过程中,底物先经过下层填料层,更高的底物浓度提高了微生物的专一性而限制了其多样性的发展。之后,下层的微生物将高浓度的底物转化为有机中间产物。由香农指数可以看出,上层的微生物群落多样性高于下层,这是由于底物浓度的降低也同时降低了对其他菌株生长的毒性抑制,而更为丰富的有机中间产物使上层微生物群落的多样性高于下层。CHUNG等[32]也报道了类似的结果。

|

图 6 上层和下层填料层中16S rRNA序列相对丰度 Fig.6 Relative abundance of the cloned 16S rRNA gene sequences for the top and bottom layers |

生物膜样品中Armatimonadetes_gp5属的高相对丰度(9.6%)表明它可能在硫醇和BTEX的生物降解过程中起重要作用。然而,目前研究中关于该菌属的VOCs降解功能的信息很少。此外,Dokdonella属被报道能降低含有葡萄糖和常见金属盐类废水COD的微生物之一[37]。KUNDU等也报道了Achromobacter属具有降低COD的能力。该菌属是一种活性硝化剂,可以稳定铵态氮和COD水平。因此,在上层该属相对丰度较高主要是因为富含大量铵根离子的营养液首先被喷洒到上层填料层,填料上生物膜中的菌株首先与铵氮接触并利用它,有利于这类菌属的繁殖。

此外,本研究还检测到一些其他菌属,如Terrimonas和Ferruginibacter等。SU等[19]报道Terrimonas在CH4和甲苯降解中起重要作用。一些报道还揭示了Terrimonas在多环芳烃、六氢-1, 3, 5-三硝基-1, 3, 5-三嗪和甲基叔丁基醚的降解菌中占主导地位[38-40]。Ferruginibacter是一种异养淡水细菌,当温度升高并且环境中存在一些有机物质与之共存时,这种细菌的数量显著增加[41]。然而,这几种菌属在BTF微生物群落体系中的作用尚不明确,还需要在未来进一步研究。

4 结论利用预先分离、驯化的混合BTEX和硫醇降解菌接种入BTF中,经过长时间运行并结合宏观动力学模型分析,考察了该体系对BTEX和硫醇混合VOCs的去除能力;通过16S rRNA测序研究了微生物群落变化情况,得到以下结论:

(1) 接种了特定的BTEX和硫醇降解菌后,BTF体系可以在10 d内达到稳定状态。优选菌的接种能大大缩短BTF的启动时间。

(2) 在该BTF体系中,单一底物进气时的最大去除能力要高于混合VOCs进气时同种底物的最大去除能力,宏观动力学分析表明,该体系多种VOCs混合物的最大去除能力为210.7 g·m-3·h-1。

(3) 微生物群落分析表明经过长时间运行后,微生物群落的组成发生了很大变化。Pandoraea sp.失去了其在初始接种菌种的主导地位,而Hydrogenophaga和Pseudomonas成为优势属。填料层生物膜中还检测到相对高含量的Achromobacter,Armatimonadetes_gp5,Dokdonella,Ferruginibacter和Thiobacillus菌属。这些结果为进一步深入了解了微生物群落与生物反应器中含硫VOCs和BTEX的宏观生物降解之间的关系提供了参考。

符号说明:

|

|

| [1] |

WANG Q L, LI S J, DONG M L, et al. Vocs emission characteristics and priority control analysis based on VOCs emission inventories and ozone formation potentials in Zhoushan[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2018, 182: 234-241. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.03.034 |

| [2] |

ESTRADA J M, KRAAKMAN N J R B, MU OZ R, et al. A comparative analysis of odour treatment technologies in wastewater treatment plants[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(3): 1100-1106. |

| [3] |

MUDLIAR S, GIRI B, PADOLEY K, et al. Bioreactors for treatment of VOCs and odours-A review[J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2010, 91(5): 1039-1054. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.01.006 |

| [4] |

PALAU J, IZQUIERDO M, MARZAL P, et al. Coupling adsorption and biological technologies for multicomponent and fluctuating volatile organic compounds emissions abatement:Laboratory-scale evaluation and full-scale implementation[J]. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2015, 54(6): 1713-1722. |

| [5] |

VAN GROENESTIJN J W, LAKE M E. Elimination of alkanes from off-gases using biotrickling filters containing two liquid phases[J]. Environmental Progress, 1999, 18(3): 151-155. DOI:10.1002/ep.670180310 |

| [6] |

GIRI B S, MUDLIAR S N, DESHMUKH S C, et al. Treatment of waste gas containing low concentration of dimethyl sulphide (DMS) in a bench-scale biofilter[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2010, 101(7): 2185-2190. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2009.11.033 |

| [7] |

KENNES C, RENE E R, VEIGA M C. Bioprocesses for air pollution control[J]. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology, 2009, 84(10): 1419-1436. DOI:10.1002/jctb.2216 |

| [8] |

MOON C, LEE E Y, PARK S. Biodegradation of gas-phase styrene in a high-performance biotrickling filter using porous polyurethane foam as a packing medium[J]. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering, 2010, 15(3): 512-519. DOI:10.1007/s12257-009-3014-3 |

| [9] |

P REZ M C, ÁLVAREZ-HORNOS F J, SAN-VALERO P, et al. Microbial community analysis in biotrickling filters treating isopropanol air emissions[J]. Environmental Technology, 2013, 34(19): 2789-2798. DOI:10.1080/09593330.2013.790067 |

| [10] |

CACERES M, MORALES M, MARTIN R S, et al. Oxidation of volatile reduced sulphur compounds in biotrickling filter inoculated with thiobacillus thioparus[J]. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, 2010, 13(5): 11-12. |

| [11] |

HU J, ZHANG L L, CHEN J M, et al. Performance and microbial analysis of a biotrickling filter inoculated by a specific bacteria consortium for removal of a simulated mixture of pharmaceutical volatile organic compounds[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2016, 304: 757-765. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2016.06.078 |

| [12] |

LI H, ZHANG Q, WANG X L, et al. Biodegradation of benzene homologues in contaminated sediment of the East China Sea[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2012, 124: 129-136. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.08.033 |

| [13] |

WAN S G, LI G Y, AN T C, et al. Biodegradation of ethanethiol in aqueous medium by a new lysinibacillus sphaericus strain rg-1 isolated from activated sludge[J]. Biodegradation, 2010, 21(6): 1057-1066. DOI:10.1007/s10532-010-9366-8 |

| [14] |

WANG X Q, WANG Q L, LI S J, et al. Degradation pathway and kinetic analysis for p-xylene removal by a novel pandoraea sp strain wl1 and its application in a biotrickling filter[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2015, 288: 17-24. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.02.019 |

| [15] |

WANG X Q, WU C, LIU N, et al. Degradation of ethyl mercaptan and its major intermediate diethyl disulfide by pseudomonas sp strain wl2[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2015, 99(7): 3211-3220. DOI:10.1007/s00253-014-6208-3 |

| [16] |

LITTLEJOHNS J V, DAUGULIS A J. Kinetics and interactions of btex compounds during degradation by a bacterial consortium[J]. Process Biochemistry, 2008, 43(10): 1068-1076. DOI:10.1016/j.procbio.2008.05.010 |

| [17] |

MATHUR A K, MAJUMDER C B. Biofiltration and kinetic aspects of a biotrickling filter for the removal of paint solvent mixture laden air stream[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2008, 152(3): 1027-1036. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.07.112 |

| [18] |

SOLOGAR V S, LU Z J, ALLEN D G. Biofiltration of concentrated mixtures of hydrogen sulfide and methanol[J]. Environmental Progress, 2003, 22(2): 129-136. DOI:10.1002/ep.670220215 |

| [19] |

SU Y, XIA F F, TIAN B H, et al. Microbial community and function of enrichment cultures with methane and toluene[J]. Applied Microbiology And Biotechnology, 2014, 98(7): 3121-3131. DOI:10.1007/s00253-013-5297-8 |

| [20] |

YANG C P, YU G L, ZENG G M, et al. Performance of biotrickling filters packed with structured or cubic polyurethane sponges for VOC removal[J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2011, 23(8): 1325-1333. DOI:10.1016/S1001-0742(10)60565-7 |

| [21] |

SERCU B, N EZ D, AROCA G, et al. Inoculation and start-up of a biotricking filter removing dimethyl sulfide[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2005, 113(2): 127-134. |

| [22] |

WAN S G, LI G Y, AN T C, et al. Co-treatment of single, binary and ternary mixture gas of ethanethiol, dimethyl disulfide and thioanisole in a biotrickling filter seeded with lysinibacillus sphaericus rg-1[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2011, 186(2/3): 1050-1057. |

| [23] |

JIME NEZ L, ARRIAGA S, AIZPURU A. Assessing biofiltration repeatability:Statistical comparison of two identical toluene removal systems[J]. Environmental Technology, 2016, 37(6): 681-693. DOI:10.1080/09593330.2015.1077894 |

| [24] |

GALLASTEGUI G, ÁVALOS RAMIREZ A, EL AS A, et al. Performance and macrokinetic analysis of biofiltration of toluene and p-xylene mixtures in a conventional biofilter packed with inert material[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2011, 102(17): 7657-7665. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2011.05.054 |

| [25] |

HAQUE F, DE VISSCHER A, SEN A. Biofiltration for btex removal[J]. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 2012, 42(24): 2648-2692. DOI:10.1080/10643389.2011.592764 |

| [26] |

ROY S, GENDRON J, DELHOM NIE M C, et al. Pseudomonas putida as the dominant toluene-degrading bacterial species during air decontamination by biofiltration[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2003, 61(4): 366-373. DOI:10.1007/s00253-003-1228-4 |

| [27] |

JECHALKE S, FRANCHINI A G, BASTIDA F, et al. Analysis of structure, function, and activity of a benzene-degrading microbial community[J]. Fems Microbiology Ecology, 2013, 85(1): 14-26. |

| [28] |

PORTUNE K J, P REZ M C, ÁLVAREZ-HORNOS F J, et al. Investigating bacterial populations in styrene-degrading biofilters by 16s rdna tag pyrosequencing[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2015, 99(1): 3-18. |

| [29] |

GRAFF A, STUBNER S. Isolation and molecular characterization of thiosulfate-oxidizing bacteria from an italian rice field soil[J]. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 2003, 26(3): 445-452. DOI:10.1078/072320203322497482 |

| [30] |

FAHY A, BALL A S, LETHBRIDGE G, et al. Isolation of alkali-tolerant benzene-degrading bacteria from a contaminated aquifer[J]. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2008, 47(1): 60-66. DOI:10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02386.x |

| [31] |

FERN NDEZ H T, RICO I R, DE LA PRIDA J J, et al. Dimethyl sulfide biofiltration using immobilized hyphomicrobium vs and thiobacillus thioparus tk-m in sugarcane bagasse[J]. Environmental Technology, 2013, 34(2): 257-262. DOI:10.1080/09593330.2012.692713 |

| [32] |

CHUNG Y C, CHENG C Y, CHEN T Y, et al. Structure of the bacterial community in a biofilter during dimethyl sulfide (DMS) removal processes[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2010, 101(18): 7165-7168. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2010.03.131 |

| [33] |

SEDIGHI M, VAHABZADEH F, ZAMIR S M, et al. Ethanethiol degradation by ralstonia eutropha[J]. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering, 2013, 18(4): 827-833. DOI:10.1007/s12257-013-0083-0 |

| [34] |

MOHAMMAD B T, VEIGA M C, KENNES C. Mesophilic and thermophilic biotreatment of btex-polluted air in reactors[J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2007, 97(6): 1423-1438. DOI:10.1002/bit.21350 |

| [35] |

RYU H W, KIM S J, CHO K S, et al. Toluene degradation in a polyurethane biofilter at high loading[J]. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering, 2008, 13(3): 360-365. DOI:10.1007/s12257-008-0025-4 |

| [36] |

LI G Y, HE Z, AN T C, et al. Comparative study of the elimination of toluene vapours in twin biotrickling filters using two microorganisms bacillus cereus s1 and s2[J]. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology, 2008, 83(7): 1019-1026. DOI:10.1002/jctb.1908 |

| [37] |

FU B, LIAO X Y, LIANG R, et al. Cod removal from expanded granular sludge bed effluent using a moving bed biofilm reactor and their microbial community analysis[J]. World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology, 2011, 27(4): 915-923. |

| [38] |

KHAN M I, YANG J, YOO B, et al. Improved rdx detoxification with starch addition using a novel nitrogen-fixing aerobic microbial consortium from soil contaminated with explosives[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2015, 287: 243-251. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.01.058 |

| [39] |

LIU H Z, YAN J P, WANG Q, et al. Biodegradation of methyl tert-butyl ether by enriched bacterial culture[J]. Current Microbiology, 2009, 59(1): 30-34. DOI:10.1007/s00284-009-9391-1 |

| [40] |

ZHANG S Y, WANG Q F, WAN R, et al. Changes in bacterial community of anthracene bioremediation in municipal solid waste composting soil[J]. Journal of Zhejiang University-Science B, 2011, 12(9): 760-768. DOI:10.1631/jzus.B1000440 |

| [41] |

LIU T, MAO Y J, SHI Y P, et al. Start-up and bacterial community compositions of partial nitrification in moving bed biofilm reactor[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2017, 101(6): 2563-2574. DOI:10.1007/s00253-016-8003-9 |