2. 自然资源部第三海洋研究所,福建 厦门 361005

2. Third Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Xiamen 361005, China

1962年《寂静的春天》的发表将化学品污染对生态环境的影响正式引入公众视野。伴随世界各国社会经济发展的不断进步,以煤作为燃料的一代污染问题在大部分地区基本得到有效的治理,而汽车尾气造成的二代污染问题也正逐步得到有效的控制。得益于化学分析检测方法的不断完善,以及对传统污染物的深入研究,逐步出现一类确已存在,但目前没有环保法律法规予以规定或规定不完善的,危害生活和生态环境的环境雌激素类物质,这类物质被称为新型环境雌激素。新型环境雌激素(environmental estrogens,EEs)在环境中痕量且广泛分布逐步引起科研人员的关注,使其逐渐成为当前环境化学与毒理学领域的研究热点。环境雌激素作为新型有机污染物的重要组成部分,进入机体后会模拟或干扰正常分泌激素的生理功能,影响生物体的神经、生殖和内分泌系统,对人类健康和生态系统都具有潜在的威胁。环境雌激素类污染物通过人类活动进入水环境,经过河流、湖泊的传输以及大气沉降等途径最终汇入海洋。目前大部分新型雌激素缺乏监管,没有相应的环境标准。因此,了解海洋环境中雌激素化合物的来源、分布以及迁移转化规律,对于今后制定海洋环境雌激素类污染物的防控对策以保护海洋水生生态环境至关重要。

2 环境雌激素化合物的发现历史和主要类型环境雌激素属于环境内分泌干扰物(endocrine disrupting chemicals,EDCs),是指一类进入机体后,具有干扰体内正常内分泌物质的合成、释放、运输、结合、代谢等过程,激活或抑制内分泌系统的功能,从而破坏维持机体稳定性和调控作用的化合物,包括人工合成雌激素及植物天然雌激素,属于环境激素中的一类,其发现历史如表 1所示。在20世纪20~30年代,科研人员最初通过向家养动物喂食发霉谷物以及对啮齿动物体内植物提取物的雌激素生物测定而确认植物雌激素和霉菌雌激素的存在,由此展开了对植物雌激素的相关研究。至40年代末期,西澳大利亚地区食用某些种类苜蓿草的羊无法生育(“苜蓿病”),在观察到这一现象后研究人员开始逐步关注此类化合物的激素效应[1],至50年代后,研究人员开始注意到农药p'-二氯二苯-三氯乙烷(dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane,DDT)在鸟类及哺乳动物中存在特定的雌激素作用。从而意识到这些药物很有可能会导致癌症、不孕、发育缺陷等一系列疾病,由此,对环境雌激素的研究正式展开[2-4]。

|

|

表 1 雌激素的发现过程 Table 1 The history of estrogen discovery |

20世纪70年代早期,研究人员在相当比例的孕妇子宫内都发现了合成雌激素二乙芪(diethyl stilbene,DES),并且证实这类物质会增加人类阴道癌的发病率,该发现引起了公众的强烈担忧[5]。美国国家环境卫生科学研究所的约翰·麦克拉伦以及加州大学的霍华德·伯恩所在实验室利用合成的DES开展了动物模型暴露的开创性研究[6-7]。之后,在80年代开始的一些研究中表明,食品中某些植物雌激素可能对健康有益[8-9]。现今为止的研究不难看出,环境中的许多化学物质都能表现出雌激素活性或抗雌激素的活性,但是它们对于生态环境的实际影响仍有待确定。

在2002年美国环保局公布的《与在动物和人体中或在试管中的内分泌系统效应有关的化学物质初步清单》[10]中所确定的内分泌干扰物质有86种,其中有10种持久性有机卤化物、1种食品抗氧化剂、57种农药、4种邻苯二甲酸酯、10种其他化合物、以及砷、镉、铅、汞4种金属。2010年欧盟大部分新型雌激素内分泌干扰物清单第1类中确定了194种物质,这些物质并不一定属于一种内分泌干扰物,但在其活体动物中存在或多或少的内分泌干扰效应证据,其中增加了锡烷、氯化石蜡、对羟基苯甲酸酯等新兴污染物质。在2017年7月底联合国环境署国际化学污染小组对现存的内分泌干扰物清单中的物质进行进一步筛选、分类,确定出45种物质,其中加入了双酚A替代物双酚F和双酚S、二硫化碳、二苯硅烷等物质[11] (表 2)。

|

|

表 2 典型环境雌激素污染物 Table 2 Typical environmental estrogens |

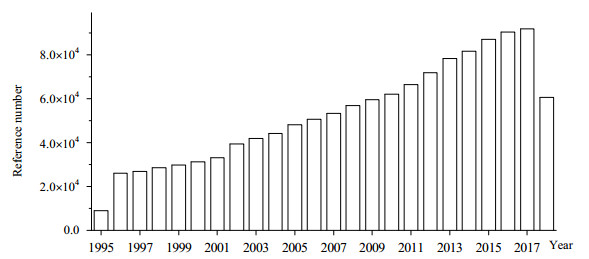

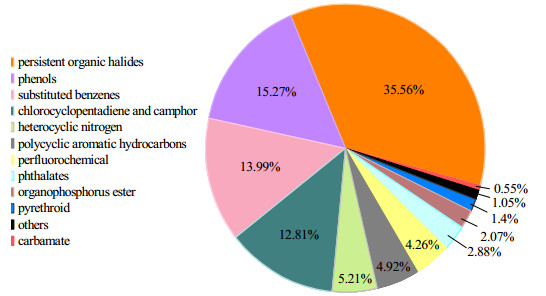

雌激素类污染物在淡水环境中的研究开展的相对较早,目前研究种类完全且相对完善,而对海洋环境中雌激素类物质的研究相对匮乏。但根据对海洋环境雌激素历年出版的文献数量的总结(图 1),可以明显地看出自海洋雌激素发现至今,无论是国内还是国外,对其研究热度都与日俱增。国内对于海洋雌激素的研究相对匮乏,目前的研究区域主要集中在黄海、渤海以及厦门海域的近海海域,而在物质层面上,主要集中在酚类以及二元醇类物质。在海洋环境中具有环境激素效应污染物主要分为以下几类,持久性有机卤化物、酚类、取代苯类、氯代环戊二烯和莰烯类、含氮杂环类、多环芳烃类、全氟化合物类、邻苯二甲酸脂类以及有机磷酸酯类。根据以上分类对不同海洋环境雌激素的文献发布数量进行分析(图 2),结果显示海洋中环境雌激素的研究主要集中在持久性有机卤化物、酚类、取代苯类以及氯代环戊二烯和莰烯类,其中持久性有机卤化物占较大比重,如多氯联苯、氯仿和六六六等都是海洋污染物研究中的热点物质。除了以上4类物质外,含氮杂环类、多环芳烃类、全氟化合物类、邻苯二甲酸脂类以及有机磷酸酯类相关的研究,也在海洋污染物研究中崭露头角。虽然目前对于这5类物质的研究相对较少,但它们在海洋中的污染程度以及将产生的生态影响也是不容小觑的。

|

图 1 海洋中雌激素研究历年出版的文献数量 Fig.1 Numbers of articles published on marine environmental estrogens Note: Search database (web of science); Query keywords (marine; ocean; sea; estrogen.) |

|

图 2 海洋中雌激素物质研究热点 Fig.2 Research hotspots in marine environmental estrogen studies Note: database (Web of Science), Query keywords (marine; ocean; sea; estrogen.) |

雌激素类物质在环境中往往是以μg·L-1或ng·L-1浓度级存在,但是即使在如此低的浓度下,也可能对生物体造成潜在的危害,因此对雌激素类污染物的分析监测应极为重视。在对雌激素类污染物进行检测时,应选择一些高灵敏性和高特异性的方法。通过有效的预处理方法,使环境样品中的痕量组分得到富集,基体干扰被消除,从而使灵敏度得到提高;与此同时,对于仪器和分析系统也可以起到一定的保护作用,使分析测定能长时间保持在稳定、可靠状态下运行[12]。因此,样品预处理在分析过程中显得十分关键。对于这类物质的检测主要分为两部分:样品预处理和浓度检测。

目前关于预处理的方法主要包括:固相萃取(solid phase extraction,SPE)、固相微萃取(solid phase microextraction,SPME)、液液萃取(liquid-liquid extraction,LLE)、基体固相分散萃取(solid phase dispersion extraction of matrix,MSPD)、搅拌子吸附萃取(agitator adsorption extraction,SBSE)和分子印记聚合物(molecularly imprinted polymer,MIPS)法等。其中以SPE法使用较多。

关于检测技术(表 3)主要有3种:气相色谱-质谱联用技术(GC-MS)、液相色谱-质谱联用技术(LC-MS)、酶联免疫吸附测定法(ELISA)。在测定雌激素时,最常用方法为GC-MS。气相色谱仪能够高效地分离样品中的各组分,而质谱主要是对物质进行定性,提高灵敏度。但是若化合物的极性很强,则在使用GC-MS分析之前,需对样品进行衍生化,使其极性降低后易于汽化,从而提高分析的敏感性和选择性,但这样会使分析过程复杂化。因此,针对极性化合物,LC-MS逐渐得到应用和发展,并且还被用作一些内分泌干扰化合物(如烷基酚类化合物)检测的常规方法。免疫分析方法(immunoassay,IA)是近几年来发展起来的新技术,其主要是应用免疫学技术来测定样本。它的作用原理是基于抗原和抗体的特异性结合的性质,优点是:预处理方法简便,检测速度快,高特异性,高灵敏度,无需昂贵的仪器设备,且当检测对象确定后,可以进行大批量的分析。在免疫分析法中,以酶联免疫吸附法(ELISA)最为常用。ELISA自20世纪70年代初问世以来,发展十分迅速,主要是以免疫学反应为基础,通过抗原、抗体的特异性反应以及酶对底物的高效催化作用而发展起来的一种新的技术,其敏感性很高,目前已被广泛用于医学、生物学及环境科学等诸多领域。

|

|

表 3 环境雌激素类物质的检测方法 Table 3 Common analysis methods for determination of environmental estrogens |

双酚A (bisphenol A,BPA),主要用于与人类生活密切相关的日用品中,在工业上被用来合成聚碳酸酯(PC)和环氧树脂等材料。60年代以来就被用于制造塑料(奶)瓶、幼儿用的吸口杯、食品和饮料(奶粉)罐内侧涂层。其是生产聚碳酸酯和环氧树脂的重要原料,也常被用作抗氧化剂或稳定剂用于聚氯乙烯生产。BPA具有细胞毒性和诱变作用,对动物和人类的免疫、内分泌、生殖、发育和神经系统产生各种不良影响,并通过各种途径显示毒性。人类的BPA代谢比啮齿动物要快得多,BPA促进肾脏雌激素代谢,通过类固醇生成上调细胞色素p-450芳香化酶活性。BPA具有肾毒性。BPA的毒性与人体接触水平和致癌性有关[13]。研究表明将斑马鱼胚胎暴露于环境相关水平的BPA (10 μg·L-1)中96 h,通过iTRAQ标记定量蛋白质组学,发现经过BPA处理的斑马鱼胚胎中出现26个差异表达蛋白,且显著上调了多个网络蛋白的表达水平,从而证明低浓度的BPA对斑马鱼胚胎有潜在的健康风险[14]。相关研究人员研究了BPA对黑斑蛙的急性毒性,发现BPA对黑斑蛙胚胎的96 h半致死浓度为7.68 mg·L-1,最小生长抑制浓度为4.47 mg·L-1,最大致畸率为33.33%;对蝌蚪的96 h半致死浓度为9.00 mg·L-1[15]。BPA与雌激素受体(ER)结合而改变内分泌功能,对人体健康产生不良影响,如乳腺癌、子宫内膜异位症、不孕不育等[16-17]。将亲代斑马鱼暴露在环境相关浓度的BPA下,会削弱它们的免疫防御能力,这表明长期暴露在野外BPA下的鱼类可能容易受到病原体的侵害[18]。壬基酚碳侧链在对位的壬基酚(4-nonylphenol,4-NP),是造成自然水体污染的主要污染物。其主要用于烷基酚聚氧乙烯醚的合成,从而生产非离子表面活性剂,造纸助剂、农药乳化剂、作洗涤剂、润滑油添加剂、织印染等。2019年LIU等人的研究表明单独和联合暴露于NP和辛基酚(OP)可能对大鼠的中枢5-HT系统和相关的学习和记忆产生毒性作用[19]。2019年WANG研究了NP对小鼠过敏性鼻炎(AR)模型的影响,并且得出了NP可能触发AR的结论[20]。

随着塑料的广泛应用,BPA的污染也越来越严重,其普遍存在于各环境介质中。不同地点的大气、水、底泥、土壤及生物相中BPA的浓度水平不同。其可在环境介质中进行生物降解、光降解。地表水中广泛存在着能够降解BPA的细菌,细菌数量、温度均会对生物降解产生影响。目前国内对BPA类污染物的调查多集中于湖泊和河流等淡水水体中,河口及近岸海域还较少(表 4)。李正炎等(2006)研究了冬季青岛胶州湾及临近河流中BPA污染特征,说明湾内污染与沿岸工业分布和河流输入密切相关[21]。ZHANG等(2009)对厦门湾沉积物中的NP、OP、BPA等的污染现状进行了调查,其中BPA浓度为1.66~122 ng·g-1·dw-1,BPA浓度最高值出现在距厦门市区较近的礁湖,研究推断厦门湾BPA的主要来源是工业废水排放[22]。董军等(2009)调查了珠江口地区河流及入海口表层水,相关分析表明水体中BPA残留量与pH值显著相关,BPA的分布呈现出沿河口方向降低的趋势[23]。

|

|

表 4 海洋环境中双酚A、壬基酚的环境浓度 Table 4 Environmental concentrations of bisphenol A and nonylphenol in marine environment |

自上世纪30年代问世以来,NP已经有近80年的生产使用历程,因此普遍存在于各种环境介质中。欧美等工业发达国家从上世纪80年代开始对NP的浓度分布和环境行为进行研究,从目前所发表的文献看,NP在河口和海水中典型的最高浓度为1 μg·L-1,其主要来源是城市污水和工业废水的排放,并可对珠江口上覆水、底泥和水生动物均造成明显污染[29]。相关科研人员研究了NP在法国塞纳河河口区的污染程度,结果显示NP在所有的样品中都能检测到,表层水中溶解态NP的浓度15~386 ng·L-1[30]。同时,研究发现悬浮物中NP的浓度由于春秋季微生物活动剧烈,导致在春季和秋季显著降低,而在冬季显著上升。水体中NP也呈现出明显的季节变化,夏季 > 春季 > 冬季。NP在周围河流中的浓度远高于海湾内部,科研人员研究了酚类内分泌干扰物在上覆水和底泥中的含量关系,及酚类内分泌干扰物在底泥中的含量与底泥中有机碳的关系,判断出酚类内分泌干扰物来源于城市污水处理厂的污水排放。

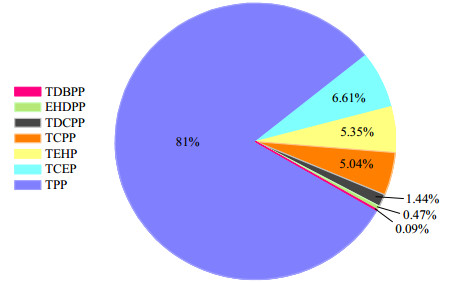

3.3 有机磷阻燃剂在海洋环境中的分布在过去几十年间溴化阻燃剂(brominated flame retardant,BFR)一直是占主导地位的阻燃剂类型。然而,因其具有生物毒性、生物蓄积性、环境持久性及长距离迁移性的特点,在国际上逐步被淘汰[37]。有机磷化合物(organophosphorus,OP)阻燃机理主要以凝聚相阻燃机理为主,当含有磷系阻燃剂的高聚物被引燃时,阻燃剂受热分解生成磷的含氧酸,这类酸能催化含羟基化合物的脱水成炭,降低材料质量,损失速度和可燃物生成量,而磷则大部分残留于碳层中。其生烟量,毒性以及腐蚀气体的释放量都少于BFR,相对来说更为高效,在某些含氧塑料中1%的磷可达到与10%的溴等效[38],故OP成为BFR的合适替代品,并且已在全世界范围内广泛使用。OP广泛用作各种工业中的阻燃剂,增塑剂和消泡剂,包括塑料,家具,纺织,电子,建筑,车辆和石油工业[39]。许多OP经常作为添加剂而不是化学键结合到各种材料上,例如家具、纺织涂料、室内装潢、电子产品、油漆、聚氯乙烯(polyvinyl chloride,PVC)塑料、聚氨酯泡沫(polyurethane foam,PUF)、润滑剂和液压油,导致了有机磷阻燃剂类污染物通过挥发,浸出或磨损更易于释放到不同的环境隔室[40]。不难看出OP已存在于各种环境基质中,深入人类的日常生活。OP在大气颗粒物、水、悬浮颗粒物、沉积物、土壤和生物群样本等各种环境介质中都有相继报道。在OP中,TCIPP (tris(2-chloroisopropyl) phosphate)、TDCPP (tris(1, 3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate)和TBOEP (tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate)这3类物质可能具有致癌性[41-43],而TCEP (tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate)、TNBP (tri-n-butyl phosphate)和TPHP (tris(phenyl) phosphate)具有神经毒性作用[44]。TPHP具有接触性过敏反应并会对生育能力产生不利影响,TDCPP则与激素水平的相关变化和男性精液质量下降有关系[45]。CRISTALE等考察了10种OPFRs及其混合物对大型溞的急性毒性,结果表明OPFRs的毒性相差很大,辛醇水分配系数(KOW)低的OPFRs其急性毒性并不明显,而KOW高的OPFRs对大型溞毒性较高[46]。牛青盟等对70例食入含三邻甲苯磷酸酯(triorthocresyl phosphate, TOCP)面粉的患者进行调查发现,TOCP对人体有急性毒性作用食用者首发症状为腓肠肌疼痛,3~7 d后出现站立不稳行走困难等迟缓性麻痹症状,1个月后出现上运动神经元麻痹的表现[47]。从总体上来看,环境中普遍存在的OP可以通过皮肤接触、吸入粉尘、吸入和饮食摄入等多种途径进去人体,从而对人类健康构成威胁。其日益增长的消耗量,以及其可知的潜在不利影响,使有机磷酸酯阻燃剂和增塑剂得到社会各界的广泛关注。同时,不同地域不同国家对于有机磷阻燃剂类污染物的监测活动也在不断进行,为编制关于排放源、环境发生、命运和影响的综合报告提供了数据依托。

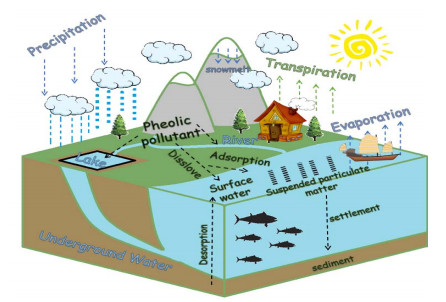

相较于其他环境雌激素物质而言,有机磷阻燃剂仍属于新兴的一类污染物质,对其含量以及分布规律方面的相关研究仍不全面,特别是与海洋环境相关的研究更为稀少,并且有机磷酸酯阻燃剂类污染物,参与地球生态系统循环,其在各种介质中的含量,都可能会对海洋环境造成影响(图 3)。常见的有机磷阻燃剂物质如TPP (triphenyl phosphate)、TCPP (tris(1-chloro-2-propyl) phosphate)、TDCPP、EHDPP (2-ethylhexyl diphenyl phosphate)等均能在各种环境中被检测到。表 5列出了公开发表的文献中检测到的世界各地环境中甚至动物体内有机磷酸酯阻燃剂的含量,显示有机磷酸酯类物质浓度在ng·L-1~μg·L-1。TCPP作为一种典型的有机磷酸酯类物质,被世界各个国家作为研究重点,其在英国、奥地利、德国、西班牙和中国的水体中浓度依次为113~26 050、3.5~43、24.3~570、0.008 3~47和5~1 150 ng·L-1,其中在英国Aire河检测出来的浓度高达26 050 ng·L-1。TDCPP在英国、西班牙、德国和中国的水体中的浓度依次为62~149、0.006~0.20、5.3~110.5和24.0~377.9 ng·L-1,在中国水体中检测到的浓度最高,为377.9 ng·L-1。TCEP也是典型有机磷酸酯阻燃剂中的一员,与TDCPP相同,TCEP同样在中国珠海检测出的浓度最高,高达1 166 ng·L-1,其在英国、西班牙、德国、奥地利和中国的水体中的浓度依次为119~316、0.002~5、3.29~118、13~23和1~1 166 ng·L-1。

|

图 3 典型有机磷酸酯阻燃剂的研究重点 Fig.3 Research topics on organophosphate flame retardants Note: Search database (web of science); Query keywords (TDBPP; EHDPP; TDCPP; TCPP; TEHP; TCEP; TPP; OPFRs.) |

|

|

表 5 环境中有机磷酸酯阻燃剂的浓度分布 Table 5 Detected concentrations of OPFRs in the environment |

从地区分布的特点而言,从表 5的数据中不难看出关于有机磷酸酯阻燃剂的研究主要集中在欧美发达国家,TCPP是其中最为主要的贡献者,主要归因于TCPP产量高且作为有机磷阻燃剂得到了广泛使用。此外,欧洲国家水环境中检测到的有机磷酸酯阻燃剂浓度普遍高于亚洲地区,表明城市化和工业污染是导致其浓度颇高的主因。如西班牙的Besos河中有机磷阻燃剂含量高于平均水平,分析可知在Besos河附近工业和生活区较为密集,在Nalon河和Arga河的数据也呈现出类似行为。

3.4 雌激素物质在生态系统中的迁移雌激素类污染物主要通过大气沉积和废水处理中的浸出进入水生生态环境,通过江、河、湖泊各种水生生态环境最终进入海洋生态环境,其在水体中的转移过程主要有吸附/解吸和生物富集(图 4)。除了溶解在上覆水中,该类污染物还可以被悬浮颗粒或胶体吸附,进而沉降在沉积物中。同时沉积物中的污染物也可通过解吸再次回到上覆水中。雌激素类污染物在上覆水和沉积物之间的分配情况,通常可以用分配系数Kd (distribution coefficient)表示。此外,雌激素类污染物能够在生物体内进行富集。其进入生物体内的方式主要有摄食、接触上覆水、悬浮颗粒和底泥等介质。

|

图 4 环境雌激素在生态系统中的迁移 Fig.4 Migration of environmental estrogens in the ecosystem |

近几年国际上对于海洋雌激素类污染物的研究逐步增多,越来越多的物质被证明或者被怀疑具有雌激素干扰效应,虽然有禁令和各种法律的限制,但是新兴的雌激素类物质仍然处于增加的状态,关于海洋环境的雌激素类物质仍然存在许多知识空白需要填补,故完善相关信息对于此类物质的进一步研究迫在眉睫。目前关于海洋雌激素类物质研究存在一些缺陷和不足,主要如下:(1)海洋雌激素类物质含量随着制造工厂和城市化地区分布的密度的增加而增加,工厂和城市化是雌激素类污染物的主要来源。(2)对海洋中雌激素类污染物检测的情况分析,其需要一种更加稳定、灵敏,并且能够根据其性质、产量、环境行为和可能对环境造成的影响来决定需要监测的具有代表性的海洋雌激素类物质的检测方法。(3)在海洋雌激素类物质的含量研究需要更多的相关数据,从而解释海洋雌激素类物质的点和扩散源在海洋环境中的贡献。(4)目前对于海洋雌激素类物质远距离运输的性质仍不明确,需要对此进行重点的研究以了解区域以及全球分布。(5)雌激素类物质在海洋环境中水、悬浮物和沉积物之间的分布,以及它们在水生生物体中的积累和可能的转化过程研究需要日后进行补充。(6)目前我国国内主要研究区域集中在黄海、渤海以及厦门海域的近海海域,缺少整体海岸线的全面检测以及分析;其次在物质种类上,国内主要集中在二元醇以及酚类物质的研究,而对于一些近期发现具有雌激素效应的物质,例如邻苯二甲酸酯类、有机磷酸酯类物质等物质的研究相对较少,需要日后相关数据的完善。

总而言之,目前对于海洋雌激素的研究仍然处于初期探索阶段,鉴定海洋中雌激素类污染物的种类及其残留水平,深入研究海洋中雌激素类污染物的迁移转化规律,阐明海洋雌激素类物质的增加和最终可能对水生环境造成的环境风险,对于保护海洋水资源环境和全球水资源健康发展具有十分重要的现实意义。

| [1] |

BENNETTS H W, UUDERWOOD E J, SHIER F L. A specific breeding problem of sheep on subterranean clover pastures in western Australia[J]. Australian Veterinary Journal, 1946, 22(1): 2-12. DOI:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1946.tb15473.x |

| [2] |

BITMAN J, CECIL H C, HARRIS S J, et al. Estrogenic activity of o, p'-DDT in the mammalian uterus and avian oviduct[J]. Science, 1968, 162(3851): 371-372. DOI:10.1126/science.162.3851.371 |

| [3] |

WELCH R M, LEVIN W, CONNEY A H. Estrogenic action of DDT and its analogs[J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 1969, 14(2): 358-367. DOI:10.1016/0041-008X(69)90117-3 |

| [4] |

BURLINGTON H, LINDEMAN V F. Effect of DDT on testes and secondary sex characters of white leghorn cockerels[J]. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine, 1950, 74(1): 48-51. |

| [5] |

HERBST A L, BERN H A. Developmental effects of diethylstilbestrol (DES) in pregnancy[M]. New York: Thieme-Stratton, 1981.

|

| [6] |

BERN H A, TALAMANTES F J. Neonatal mouse models and their relation to disease in the human female[J]. Developmental Effects of Diethylstilbestrol (DES) in Pregnancy, 1981, 129-147. |

| [7] |

NEWBOLD R R. Diethylstilboestrol-associated defects in murine genital tract development[J]. Estrogens in the Environment: Influences on Development, 1985, 288-318. |

| [8] |

KURZER M S, XU X. Dietary phytoestrogens[J]. Annual Review of Nutrition, 1997, 17(1): 353-381. DOI:10.1146/annurev.nutr.17.1.353 |

| [9] |

ADLERCREUTZ H, MAZUR W. Phyto-oestrogens and western diseases[J]. Annals of Medicine, 1997, 29(2): 95-120. DOI:10.3109/07853899709113696 |

| [10] |

任仁, 黄俊. 哪些物质属于内分泌干扰物(EDCs)[J]. 安全与环境工程, 2004, 11(3): 7-10. REN R, HUANG J. Which are endocrine disruptors (estrogen)[J]. Safety and Environmental Engineering, 2004, 11(3): 7-10. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-1556.2004.03.003 |

| [11] |

UN List of Identified Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals[EB/OL]. https://www.chemsafetypro.com/Topics/Restriction/UN list identified endocrine disrupting chemicals EDCs.html, 2017-10-17/2019-03-08.

|

| [12] |

龚诚, 刁悦, 沈卫阳, 等. 环境内分泌干扰物的检测分析研究近况[J]. 药学进展, 2008, 32(12): 548-555. GONG C, DIAO Y, SHEN W Y, et al. Recent advances in determination and analysis of endocrine disrupting chemicals[J]. Progress in Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2008, 32(12): 548-555. |

| [13] |

GOWDER S. Nephrotoxicity of bisphenol A (BPA) - An updated review[J]. Current Molecular Pharmacology, 2013, 6(3): 163-172. |

| [14] |

DONG X, QIU X, MENG S, et al. Proteomic profile and toxicity pathway analysis in zebrafish embryos exposed to bisphenol A and di-n-butyl phthalate at environmentally relevant levels[J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 193: 313-320. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.11.042 |

| [15] |

李圆圆, 付旭锋, 赵亚娴, 等. 双酚A与其替代品对黑斑蛙急性毒性的比较[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2015, 10(2): 251-257. LI Y Y, FU X F, ZHAO Y X, et al. Comparison on acute toxicity of bisphenol A with its substitutes to pelophylax nigromaculatus[J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2015, 10(2): 251-257. |

| [16] |

STOLZ A, SCHÖNFELDER G, SCHNEIDER M R. Endocrine disruptors: Adverse health effects mediated by EGFR?[J]. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2018, 29(2): 69-71. |

| [17] |

SIMONELLI A, GUADAGNI R, DE F P, et al. Environmental and occupational exposure to bisphenol A and endometriosis: Urinary and peritoneal fluid concentration levels[J]. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 2017, 90(1): 49-61. DOI:10.1007/s00420-016-1171-1 |

| [18] |

DONG X, ZHANG Z, MENG S, et al. Parental exposure to bisphenol A and its analogs influences zebrafish offspring immunity[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 610: 291-297. |

| [19] |

LIU H, HUANG Q, SUN H, et al. Effects of separate or combined exposure of nonylphenol and octylphenol on central 5-HT system and related learning and memory in the rats[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019, 172: 523-529. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.02.007 |

| [20] |

WANG Y, GU Z, CAO Z, et al. Nonylphenol can aggravate allergic rhinitis in a murine model by regulating important Th cell subtypes and their associated cytokines[J]. International Immunopharmacology, 2019, 70: 260-267. DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2019.02.030 |

| [21] |

李正炎, 傅明珠, 王馨平, 等. 冬季胶州湾及其周边河流中酚类环境激素的分布特征[J]. 中国海洋大学学报(自然科学版), 2006, 36(3): 451-455. LI Z Y, FU M Z, WANG X P, et al. Distribution of phenolic environmental hormones in Jiaozhou Bay and its adjacent rivers in winter[J]. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 2006, 36(3): 451-455. |

| [22] |

ZHANG X, LI Q, LI G, et al. Levels of estrogenic compounds in Xiamen Bay sediment, China[J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2009, 58(8): 1210-1216. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.03.011 |

| [23] |

董军, 李向丽, 梁锐杰. 珠江口地区水体中双酚A污染及其与环境因子的关系[J]. 生态与农村环境学报, 2009, 25(2): 94-97. DONG J, LI X L, LIANG R J. Bisphenol A pollution in the pearl river estuary and its relationship with environmental factors[J]. Journal of Ecology and Rural Environment, 2009, 25(2): 94-97. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-4831.2009.02.019 |

| [24] |

POJANA G, GOMIERO A, JONKERS N, et al. Natural and synthetic endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) in water, sediment and biota of a coastal lagoon[J]. Environment International, 2007, 33(7): 929-936. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2007.05.003 |

| [25] |

龚剑, 冉勇, 陈迪云, 等. 珠江三角洲两条主要河流沉积物中的典型内分泌干扰物污染状况[J]. 生态环境学报, 2011, 8(30): 1-37. GONG J, RAN Y, CHEN D, et al. Contamination of typical endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the sediment of two main rivers from the Pearl River Delta[J]. Ecology & Environmental Sciences, 2011, 8(30): 1-37. |

| [26] |

ROCHA M J, CRUZEIRO C, REIS M, et al. Spatial and seasonal distribution of 17 endocrine disruptor compounds in an urban estuary (Mondego River, Portugal): Evaluation of the estrogenic load of the area[J]. Environmental Monitoring & Assessment, 2014, 186(6): 3337-3350. |

| [27] |

SELVARAJ K K, SHANMUGAM G, SAMPATH S, et al. GC-MS determination of bisphenol A and alkylphenol ethoxylates in river water from India and their ecotoxicological risk assessment[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2014, 99: 13-20. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.09.006 |

| [28] |

ZHANG Z, REN N, KANNAN K, et al. Occurrence of endocrine-disrupting phenols and estrogens in water and sediment of the Songhua River, Northeastern China[J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination & Toxicology, 2014, 66(3): 361-369. |

| [29] |

刁盼盼.酚类内分泌干扰物对珠江口水体和水产动物的污染及风险评价[D].广州: 暨南大学, 2017. DIAO P P. Pollution and risk assessment of phenolic endocrine disruptors in pearl river estuary water and aquatic animals[D]. Guangzhou: Ji'nan University, 2017. |

| [30] |

CAILLEAUD K, FORGET L J, SOUISSI S, et al. Seasonal variation of hydrophobic organic contaminant concentrations in the water-column of the Seine Estuary and their transfer to a planktonic species Eurytemora affinis (Calanoid, copepod). Part 2: Alkylphenol-polyethoxylates[J]. Chemosphere, 2007, 70(2): 281-287. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.06.012 |

| [31] |

孙培艳, 李正炎, 王鑫平, 等. 黄河入海口壬基酚污染分布特征[J]. 海岸工程, 2007, 26(3): 17-22. SUN P Y, LI Z Y, WANG X P, et al. Distribution characteristics of nonylphenol pollutant in the Yellow River mouth area[J]. Coastal Engineering, 2007, 26(3): 17-22. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-3682.2007.03.003 |

| [32] |

FU M, LI Z, GAO H. Distribution characteristics of nonylphenol in Jiaozhou Bay of Qingdao and its adjacent rivers[J]. Chemosphere, 2007, 69(7): 1009-1016. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.04.061 |

| [33] |

LI D, DONG M, SHIM W J, et al. Distribution characteristics of nonylphenolic chemicals in Masan Bay environments, Korea[J]. Chemosphere, 2008, 71(6): 1162-1172. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.10.023 |

| [34] |

刘文萍, 石晓勇, 王晓波, 等. 北黄海辽宁近岸水环境中壬基酚污染状况调查及生态风险评估[J]. 海洋环境科学, 2009, 28(6): 664-667. LIU W P, SHI X Y, WANG X B, et al. Investigation and ecological risk assessment of nonylphenol pollution in Liaoning coastal waters in the north yellow sea[J]. Marine Environmental Science, 2009, 28(6): 664-667. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-6336.2009.06.016 |

| [35] |

DIEHL J, JOHNSON S E, XIA K, et al. The distribution of 4-nonylphenol in marine organisms of North American Pacific Coast estuaries[J]. Chemosphere, 2012, 87(5): 490-497. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.12.040 |

| [36] |

CHEN R, YIN P, ZHAO L, et al. Spatial-temporal distribution and potential ecological risk assessment of nonylphenol and octylphenol in riverine outlets of Pearl River Delta, China[J]. Journal of environmental sciences, 2014, 26(11): 2340-2347. DOI:10.1016/j.jes.2014.09.019 |

| [37] |

季麟, 高宇, 田英. 有机磷阻燃剂生产使用及我国相关环境污染研究现况[J]. 环境与职业医学, 2017, 34(3): 271-279. JI L, GAO Y, TIAN Y. Production and application of organophosphorus flame retardants and research status of related environmental pollution in China[J]. Journal of Environmental and Occupational Medicine, 2017, 34(3): 271-279. |

| [38] |

欧育湘. 我国有机磷阻燃剂产业的分析与展望[J]. 化工进展, 2011, 30(1): 210-215. OU Y X. Developments of organic phosphorus flame retardant industry in China[J]. Chemical Industry & Engineering Progress, 2011, 30(1): 210-215. |

| [39] |

MARKLUND A, ANDERSSON B, HAGLUND P. Traffic as a source of organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in snow[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2005, 39(10): 3555-3562. |

| [40] |

STAPLETON H M, KLOSTERHAUS S, EAGLE S, et al. Detection of organophosphate flame retardants in furniture foam and US house dust[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2009, 43(19): 7490-7495. |

| [41] |

VAN D E N, DIRTU A C, NEELS H, et al. Analytical developments and preliminary assessment of human exposure to organophosphate flame retardants from indoor dust[J]. Environment International, 2011, 37(2): 454-461. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2010.11.010 |

| [42] |

World Health Organization. Flame retardants: Tris(chloropropyl) phosphate and tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate[J]. Environmental Health Criteria, 1998. |

| [43] |

VAN E G J. World Health Organization. Flame retardants: Tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate, tris(2-ethylhexyl) phosphate, tetrakis (hydroxymethyl) phosphonium salts[J]. Environmental Health Criteria, 2000. |

| [44] |

World Health Organization. Tricresyl phosphate[J]. Environmental Health Criteria, 1990(110): 112. |

| [45] |

徐怀洲, 王智志, 张圣虎, 等. 有机磷酸酯类阻燃剂毒性效应研究进展[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2018, 13(3): 19-30. XU H Z, WANG Z Z, ZHANG S H, et al. Research progress on toxic effects of organic phosphate flame retardants[J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2018, 13(3): 19-30. |

| [46] |

PANG L, LIU J, YIN Y, et al. Evaluating the sorption of organophosphate esters to different sourced humic acids and its effects on the toxicity to Daphnia magna[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2013, 32(12): 2755-2761. DOI:10.1002/etc.2360 |

| [47] |

牛青盟, 杨家琳, 杨长安. 三邻甲苯磷酸脂暴发中毒70例临床分析[J]. 陕西医学杂志, 2006, 35(3): 369-371. NIU Q M, YANG J L, YANG C A. Clinical analysis of 70 cases of trio-toluene phosphoric acid poisoning[J]. Shanxi Medical Journal, 2006, 35(3): 369-371. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-7377.2006.03.055 |

| [48] |

BROMMER S, HARRAD S. Sources and human exposure implications of concentrations of organophosphate flame retardants in dust from UK cars, classrooms, living rooms, and offices[J]. Environment International, 2015, 83: 202-207. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2015.07.002 |

| [49] |

VAN D E N, DIRTU A C, NEELS H, et al. Analytical developments and preliminary assessment of human exposure to organophosphate flame retardants from indoor dust[J]. Environment International, 2011, 37(2): 454-461. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2010.11.010 |

| [50] |

FAN X, KUBWABO C, RASMUSSEN P E, et al. Simultaneous determination of thirteen organophosphate esters in settled indoor house dust and a comparison between two sampling techniques[J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2014, 491: 80-86. |

| [51] |

ABDALLAH M A E, COVACI A. Organophosphate flame retardants in indoor dust from Egypt: Implications for human exposure[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(9): 4782-4789. |

| [52] |

ARAKI A, SAITO I, KANAZAWA A, et al. Phosphorus flame retardants in indoor dust and their relation to asthma and allergies of inhabitants[J]. Indoor Air, 2014, 24(1): 3-15. DOI:10.1111/ina.12054 |

| [53] |

TAJIMA S, ARAKI A, KAWAI T, et al. Detection and intake assessment of organophosphate flame retardants in house dust in Japanese dwellings[J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2014, 478: 190-199. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.12.121 |

| [54] |

KANAZAWA A, SAITO I, ARAKI A, et al. Association between indoor exposure to semi-volatile organic compounds and building-related symptoms among the occupants of residential dwellings[J]. Indoor Air, 2010, 20(1): 72-84. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0668.2009.00629.x |

| [55] |

BRANDSMA S H, DE B J, VAN V M J, et al. Organophosphorus flame retardants (PFRs) and plasticizers in house and car dust and the influence of electronic equipment[J]. Chemosphere, 2014, 116: 3-9. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.02.036 |

| [56] |

ALI N, DIRTU A C, VAN D E N, et al. Occurrence of alternative flame retardants in indoor dust from New Zealand: Indoor sources and human exposure assessment[J]. Chemosphere, 2012, 88(11): 1276-1282. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.03.100 |

| [57] |

CEQUIER E, IONAS A C, COVACI A, et al. Occurrence of a broad range of legacy and emerging flame retardants in indoor environments in Norway[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(12): 6827-6835. |

| [58] |

DIRTU A C, ALI N, VAN D E N, et al. Country specific comparison for profile of chlorinated, brominated and phosphate organic contaminants in indoor dust. Case study for Eastern Romania, 2010[J]. Environment International, 2012, 49: 1-8. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2012.08.002 |

| [59] |

DODSON R E, PEROVICH L J, COVACI A, et al. After the PBDE phase-out: A broad suite of flame retardants in repeat house dust samples from California[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012, 46(24): 13056-13066. |

| [60] |

STAPLETON H M, KLOSTERHAUS S, EAGLE S, et al. Detection of organophosphate flame retardants in furniture foam and US house dust[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2009, 43(19): 7490-7495. |

| [61] |

CARIGNAN C C, Mcclean M D, COOPER E M, et al. Predictors of tris(1, 3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate metabolite in the urine of office workers[J]. Environment International, 2013, 55: 56-61. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2013.02.004 |

| [62] |

BROMMER S, HARRAD S, VAN D E N, et al. Concentrations of organophosphate esters and brominated flame retardants in German indoor dust samples[J]. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 2012, 14(9): 2482-2487. DOI:10.1039/c2em30303e |

| [63] |

ALI N, ALI L, MEHDI T, et al. Levels and profiles of organochlorines and flame retardants in car and house dust from Kuwait and Pakistan: Implication for human exposure via dust ingestion[J]. Environment International, 2013, 55: 62-70. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2013.02.001 |

| [64] |

FROMME H, LAHRZ T, KRAFT M, et al. Organophosphate flame retardants and plasticizers in the air and dust in German daycare centers and human biomonitoring in visiting children (LUPE 3)[J]. Environment International, 2014, 71: 158-163. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2014.06.016 |

| [65] |

ZHANG W, WANG P, LI Y, et al. Spatial and temporal distribution of organophosphate esters in the atmosphere of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, China[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2019, 244: 182-189. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.09.131 |

| [66] |

BERGH C, TORGRIP R, EMENIUS G, et al. Organophosphate and phthalate esters in air and settled dust – A multi-location indoor study[J]. Indoor Air, 2011, 21(1): 67-76. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0668.2010.00684.x |

| [67] |

RODIL R, QUINTANA J B, CONCHA G E, et al. Emerging pollutants in sewage, surface and drinking water in Galicia (NW Spain)[J]. Chemosphere, 2012, 86(10): 1040-1049. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.11.053 |

| [68] |

KIM U J, WANG Y, LI W, et al. Occurrence of and human exposure to organophosphate flame retardants/plasticizers in indoor air and dust from various microenvironments in the United States[J]. Environment International, 2019, 125: 342-349. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.065 |

| [69] |

WOLSCHKE H, SUHRING R, XIE Z, et al. Organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in the aquatic environment: A case study of the Elbe River, Germany[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2015, 100: 488-493. |

| [70] |

RBC Elbe, RBC data information system (FIS). www.fgg-elbe.de.[accessed 10.02.15].

|

| [71] |

FRIES E, PUTTMANN W. Occurrence of organophosphate esters in surface water and ground water in Germany[J]. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 2001, 3(6): 621-626. DOI:10.1039/b105072a |

| [72] |

RODIL R, QUINTANA J B, CONCHA G E, et al. Emerging pollutants in sewage, surface and drinking water in Galicia (NW Spain)[J]. Chemosphere, 2012, 86(10): 1040-1049. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.11.053 |

| [73] |

QUEDNOW K, PUTTMANN W. Organophosphates and synthetic musk fragrances in freshwater streams in Hessen/Germany[J]. CLEAN – Soil, Air, Water, 2008, 36(1): 70-77. DOI:10.1002/clen.200700023 |

| [74] |

WANG R, TANG J, XIE Z, et al. Occurrence and spatial distribution of organophosphate ester flame retardants and plasticizers in 40 rivers draining into the Bohai Sea, North China[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2015, 100: 172-178. |

| [75] |

MARTÍNEZ C E, GONZÁLEZ B C, SITKA A, et al. Determination of selected organophosphate esters in the aquatic environment of Austria[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2007, 388(1/2/3): 290-299. |

| [76] |

MCDONOUGH C A, DE S A O, SUN C, et al. Dissolved organophosphate esters and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in remote marine environments: Arctic surface water distributions and net transport through Fram Strait[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(11): 6208-6216. |

| [77] |

AZNAR A Ò, SALA B, PLON S, et al. Halogenated and organophosphorus flame retardants in cetaceans from the southwestern Indian Ocean[J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 226: 791-799. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.165 |

| [78] |

MO L, ZHENG J, WANG T, et al. Legacy and emerging contaminants in coastal surface sediments around Hainan Island in South China[J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 215: 133-141. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.10.022 |

| [79] |

LIU Y E, LUO X J, HUANG L Q, et al. Organophosphorus flame retardants in fish from Rivers in the Pearl River Delta, South China[J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2019, 663: 125-132. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.344 |

| [80] |

SALA B, GIMÉNEZ J, De S R, et al. First determination of high levels of organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in dolphins from Southern European waters[J]. Environmental Research, 2019, 172: 289-295. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2019.02.027 |

| [81] |

REGNERY J, PÜTTMANN W. Occurrence and fate of organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in urban and remote surface waters in Germany[J]. Water Research, 2010, 44(14): 4097-4104. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2010.05.024 |

| [82] |

LEE S, CHO H J, CHOI W, et al. Organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs) in water and sediment: Occurrence, distribution, and hotspots of contamination of Lake Shihwa, Korea[J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2018, 130: 105-112. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.03.009 |

| [83] |

ZHONG M, WU H, MI W, et al. Occurrences and distribution characteristics of organophosphate ester flame retardants and plasticizers in the sediments of the Bohai and Yellow Seas, China[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 615: 1305-1311. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.272 |

| [84] |

CRISTALE J, VAZQUEZ A G, BARATA C, et al. Priority and emerging flame retardants in rivers: Occurrence in water and sediment, Daphnia magna toxicity and risk assessment[J]. Environment International, 2013, 59: 232-243. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2013.06.011 |

| [85] |

CRISTALE J, KATSOYIANNIS A, SWEETMAN A J, et al. Occurrence and risk assessment of organophosphorus and brominated flame retardants in the River Aire (UK)[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2013, 179: 194-200. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2013.04.001 |

| [86] |

BOLLMANN U E, MOLLER A, XIE Z, et al. Occurrence and fate of organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in coastal and marine surface waters[J]. Water Research, 2012, 46(2): 531-538. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2011.11.028 |

| [87] |

WANG X, HE Y, LIN L, et al. Application of fully automatic hollow fiber liquid phase microextraction to assess the distribution of organophosphate esters in the Pearl River Estuaries[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 470(471): 263-269. |

| [88] |

HU M, LI J, ZHANG B, et al. Regional distribution of halogenated organophosphate flame retardants in seawater samples from three coastal cities in China[J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2014, 86(1/2): 569-574. |

| [89] |

LAI N L S, KWOK K Y, WANG X, et al. Assessment of organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in aquatic environments of China (Pearl River Delta, South China Sea, Yellow River Estuary) and Japan (Tokyo Bay)[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2019, 371: 288-294. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.03.029 |

| [90] |

REGNERY J, PÜTTMANN W. Occurrence and fate of organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in urban and remote surface waters in Germany[J]. Water Research, 2010, 44(14): 4097-4104. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2010.05.024 |