2. 200025 上海,上海交通大学医学院附属瑞金医院北院老年病科

2. Department of Geriatrics, Ruijin Hospital North, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200025, China

随着人类寿命延长,社会老龄化日益严重,骨质疏松症(osteoporosis, OP)已经成为人类健康所面临的重大问题。该疾病的发病机制并不明确,随年龄增长出现的雌激素水平下降是发生该病的关键因素,也可能会导致多种疾病同时发生[1]。老年人是OP高发人群,同时也发现老年人多患有肌少症,这两种疾病互为影响[2]。肌肉减少症(以下简称肌少症)最初定义由Irwin Rosenberg在1989年提出,2011年国际肌少症会议工作组将肌少症定义为一类进行性、广泛性的骨骼肌量和肌力减少的疾病[3]。肌少症诊断包括三个要素,即肌量减少、肌力减少和肌肉功能减退,肌少症是导致机体功能和生活质量下降甚至死亡的综合征。肌肉作为一个巨大的能量器官,影响着包括骨骼在内的多个系统[3-4]。一项两年日本随访的研究表明,肌少症是独居老人跌倒的危险因素[5]。肌少症患者更易发生桡骨远端骨折[6]。在老年男性中,因缺乏锻炼导致肌肉减少会增加髋关节骨折的风险[7]。握力作为一种简单、便捷、经济的检测方式能够客观反映局部肌力状况。评估肌力时,下肢肌力比上肢肌力更具有意义[8]。握力测定与下肢肌力相关性良好,一般男性握力小于30 kg,女性握力小于20 kg为肌力减少[9]。有研究表明,握力下降不仅可以反映骨量丢失[10-11],而且能预测骨折风险[12]。但握力测定用于骨量减少/OP诊断的阈值尚无定论。

骨量评估方法以双能X线吸收检测法(dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, DXA)为公认的方法。DXA虽作为诊断OP的金标准,但该方法在实际使用中仍有一定的局限性。仪器设备体积大、移动性差、放射性等均限制了其在大规模流行病学研究中对OP及其骨折高危人群的筛查。鉴于目前建议采用无创、经济、简便的手段,筛查OP及其骨折高危人群既往研究曾证实一项简单有效的手段:亚洲人骨质疏松自我筛查工具(osteoporosis self-assessment tool for Asians, OSTA)指数能较好地区分OP和非OP人群[13-14],且在人群中证实该指数预报OP性骨折的能力。本研究旨在探讨人群中采用握力测定并结合OSTA指数筛查OP的能力及其阈值。

对象与方法 对象选取上海瑞金医院体检人群中313名女性受检者;年龄20~85岁。排除标准:患有原发性闭经者;风湿性关节炎、系统性红斑狼疮等免疫性疾病;患有恶性肿瘤史;患有心肺、肝、肾等慢性内脏器官疾病;患有甲状旁腺功能亢进、甲状旁腺功能减退、甲状腺功能亢进、糖尿病等代谢性疾病;患有类风湿关节炎、Paget's病等骨骼疾病;曾经服用或正在服用抗抑郁药、类固醇激素类等药物;严重营养状况不良如溃疡性结肠炎等。

一般资料采集对研究对象进行标准化问卷调查,每名受检者均在一位研究者的帮助下完成问卷调查,内容包括既往病史、吸烟饮酒史、骨折史,月经史、绝经定义为连续自然停经12个月以上。每位研究对象均接受常规体格检查包括身高、体质量、腰围、臀围、血压和体脂的测定。

相关指标测量身高(cm)测量:受检者去鞋赤脚,立于身高计的底板上,脚跟、骶骨部及两肩胛间紧靠身高计的立柱上,躯干自然挺直,头部正直水平。将其头部调整到耳屏上缘与眼眶下缘的最低点齐平,再移动身高计的水平板下滑轻压于受检者的头顶,使其松紧度适当,测试人员双眼与压板水平面等高进行读数,测量出身高(cm)精确到个位。

体质量(kg)测量:测量前校正体质量计,受检者去除衣物,去鞋赤脚,立正姿势站立于体质量机底板上,待读数稳定后,测试人员读取测量数值,记录体质量(kg),精确到小数点后一位。

腰围(cm)测量:受检者穿单衣双手下垂站立,两脚分开,与肩同宽。用皮尺测量髂嵴上缘和第12肋下缘连线的中点水平线,读数。

臀围(cm)测量:受检者要求同前,测量环绕臀部的骨盆最大周径,读数。其精确度允许误差为0.1 cm,读数以cm为单位,取小数点后一位。取腰围与臀围两者比值可得腰臀比(waist to hip ratio,WHR)。

体脂(%)测量:测量前输入受检者身高、体质量、性别、年龄,受检者去鞋赤脚站立于体脂仪底板芯片上,双手自然握住测试把并覆盖于芯片上,双手向前平伸,双臂呈水平位,待读数稳定后,测试人员读取数据,单位为%,精确到小数后一位。

OSTA指数计算:OSTA=(体质量-年龄)×0.2,取整数[13]。

生化指标测定:本组研究对象均经过12 h以上过夜空腹,于次日清晨采集静脉血,离心处理将血清分离。其中1份血清通过全自动生化分析仪进行检查,肝、肾功能,电解质,血脂4项(总胆固醇、三酰甘油、高密度脂蛋白胆固醇、低密度脂蛋白胆固醇)、空腹血糖,口服75 g葡萄糖粉后2 h血糖、糖化血红蛋白(hemoglobin A1c, HbA1c)。剩余血清于-80 ℃下储存备用。血清骨钙素以化学发光法检测[罗氏诊断产品(上海)有限公司,批内差异5%,批间差异10%]。

骨密度(bone mineral density, BMD)测量:以双能X线吸收检测法(dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, DXA)检测受检者腰椎及股骨近端BMD。BMD测定由专业的BMD测定医师在同一台BMD仪(GE Lunar Prodigy)上完成(检测变异系数2.87%)。

握力测定:以CAMRY电子握力器测定每位受检者的握力,不同握力部位测定结果变异<10%。志愿者均采取坐位,肘关节屈曲90°。支撑住并测量,每只手测3组数据,取平均值。整个测量要求受检者用最大力量握紧测力仪,并最少持续3秒[15]。

OP状态评估及分组根据世界卫生组织(World Health Organiz-ation,WHO)有关正常骨量、骨量减少和OP诊断标准:(1)骨量正常:BMD较同性别正常成年人骨量峰值减低不超过1个标准差,即T值>-1;(2)骨量减少:BMD较同性别正常成年人骨量峰值减低1~2.5个标准差,即-2.5<T值≤ -1;(3)OP:BMD较正常成年人骨量峰值减低2.5个标准差以上,即T值≤ -2.5。

根据OSTA得分分组:OSTA<-4为OP高风险组;-4≤OSTA≤-1 OP中风险组;OSTA>-1为OP低风险组[10]。

统计学方法采用SPSS 17.0统计学软件包进行统计学处理。运用Kolmogorov-Smirnov统计学检验方法进行数据正态性检验。计量数据以均数±标准差(x±s)表示,正态分布的定量变量行独立样本t检验,单因素方差分析(One-way ANOVA);两两比较采用LSD检验。校正协变量因素对因变量的线性影响,采用协方差分析(ANCOVA)。使用Pearson多元相关分析BMD、骨钙素、Ⅰ型胶原交联羧基末端肽(cross-linked carboxy-terminal telopeptide of type1 collagen,CTX)、血糖、糖化血红蛋白、体脂、握力、OSTA各个指标之间的相关性,以及年龄、性别、人体测量学指标与BMD各参数之间相关性。以多元逐步回归法分析决定各部位BMD的主要影响因素。二分类变量判别效果的分析与评价采用受试者工作特征(receiver operating characteristic,ROC)曲线,分别计算敏感度,特异度和曲线下面积(area under the curve,AUC)。切点的判定方法:(敏感性+特异性-1)的最大值,以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结果 受检者基本资料及BMD测试结果绝经后女性握力水平较绝经前女性明显降低(23.28±5.29 kg vs. 25.88±5.12kg,P<0.01)(表 1)。骨量正常、骨量减少和OP妇女的握力依次明显下降(表 2)。

| 组别 | 例数 | 年龄(岁) | 身高(cm) | 体质量(kg) | BMI(kg/m2) | 腰臀比 | 体脂(%) | 握力(kg) | HbA1c(%) | 骨钙素(μg/L) | CTX(μg/L) | BMD(g/cm2) | ||||

| L1-L4 | L2-L4 | 股骨颈 | 全髋 | |||||||||||||

| 绝经前女性 | 99 | 45.4±8.3 | 160.4±4.49 | 60.10±7.54 | 23.62±2.79 | 0.77±0.07 | 31.23±3.67 | 25.88±5.12 | 5.64±1.37 | 14.39±5.91 | 0.24±0.14 | 1.20±0.17 | 1.23±0.17 | 0.94±0.13 | 0.99±0.14 | |

| 绝经后女性 | 214 | 61.9±8.7** | 158.0±5.22 | 59.14±9.49 | 23.78±3.20 | 0.86±0.06 | 33.86±4.74 | 23.28±5.29 | 5.86±0.77 | 20.2±6.55 | 0.37±0.17 | 1.02±0.17 | 1.04±0.22 | 0.83±0.l3 | 0.87±0.19 | |

| 总人群 | 313 | 57.1±11.2 | 159.3±5.12 | 59.35±8.90 | 23.70±3.03 | 0.83±0.06 | 33.27±4.61 | 23.87±5.49 | 5.80±1.08 | 18.55±6.93 | ]0.33±0.16 | 1.17±0.19 | 1.09±0.23 | 0.86±0.15 | 0.91±0.19 | |

| P | 0.007 | 0.017 | - | - | - | 0.000 | 0.000 | - | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| BMD:骨密度;BMI:体质量指数:HbA1c:糖化血红蛋白; CTX:Ⅰ型胶原交联羧基末端肽 | ||||||||||||||||

| 组别 | 例数 | 年龄(岁) | 握力(kg) | 身高(cm) | BMI(kg/m2) | 腰臀比 | 体脂(%) | HbA1c(%) | 骨钙素(ng/mL) |

| 骨量正常组 | 173 | 52.65±10.18 | 25.50±5.27 | 160.39±4.65 | 24.43±2.98 | 0.83±0.05 | 33.21±3.81 | 5.82±1.39 | 16.25±5.61 |

| 骨量减少组 | 113 | 62.10±9.81 | 22.41±5.40 | 158.35±5.28 | 23.22±2.75 | 0.83±0.06 | 33.70±4.79 | 5.79±0.53 | 21.14±7.51 |

| 骨质疏松组 | 26 | 65.10±8.10 | 20.72±3.96 | 157.21±5.74 | 21.48±2.92 | 0.84±0.08 | 31.89±6.90 | 5.74±0.33 | 22.53±6.60 |

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | - | - | - | 0.000 | |

| BMD:骨密度;BMI:体质量指数:HbA1c:糖化血红蛋白 | |||||||||

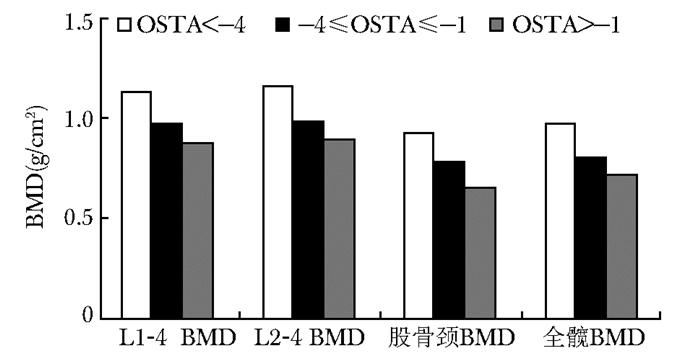

握力与各部位BMD均呈显著正相关,且在校正年龄后这一正相关关系依旧存在(表 3)。握力<20 kg与握力≥20 kg组比较,腰椎BMD及股骨颈BMD显著降低(表 4)。BMD随OSTA下降而下降(图 1),组间比较,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

| BMD | 握力(kg) | |||||

| r | P | ra | P | rb | P | |

| L1-L4 | 0.329 | 0.000 | 0.236 | 0.000 | 0.108 | - |

| L2-L4 | 0.329 | 0.000 | 0.248 | 0.000 | 0.136 | 0.05 |

| 股骨颈 | 0.313 | 0.000 | 0.157 | 0.009 | 0.032 | - |

| 全髋 | 0.343 | 0.000 | 0.13 | 0.031 | 0.20 | - |

| BMD:骨密度;ra:校正年龄后相关性r值;rb校正年龄、体质量后相关性r值 | ||||||

| BMD | 握力(kg) | P | |

| <20 | ≥20 | ||

| L1-L4 | 0.989±0.17 | 1.087±0.19 | 0.000 |

| L2-L4 | 0.986±0.29 | 1.117±0.20 | 0.000 |

| 股骨颈 | 0.818±0.14 | 0.871±0.15 | 0.050 |

| 全髋 | 0.862±0.15 | 0.914±0.21 | - |

|

| 图 1 BMD与OSTA相关性 Figure 1 Bone mineral density decreased with the decrease of OSTA value OSTA:亚洲人骨质疏松自我筛查工具;BMD:骨密度 |

握力是腰椎BMD的独立影响因素(L1-4 BMD: β=0.040,P=0.016;L2-4 BMD: β=0.070,P=0.005),OSTA是股骨颈(β=0.003,P=0.000)及全髋BMD (β=0.035,P=0.000)的独立影响因素。

握力单独及联合OSTA指数筛查OP的价值ROC曲线提示握力具有区分骨量正常、骨量异常(包括骨量下降和OP)的能力(AUC=0.674,P<0.01)。当诊断骨量减少和OP的握力阈值为22.8 kg时,其敏感度为70.7%,特异度为56.1%。联合OSTA<-1和握力≤20.45 kg时筛查骨量减少和OP的敏感度为81%,特异度为31%,比单独使用握力敏感性有显著提高(AUC=0.810,95% CI:0.76~0.86,P<0.01)(表 5)。

| 指标 | AUC | 95% CI | P |

| 握力≤22.8 kg | 0.674 | 0.61~0.72 | 0.001 |

| OSTA≤-1 | 0.790 | 0.71~0.87 | 0.000 |

| OSTA≤-1和握力≤20.45 kg | 0.810 | 0.76~0.86 | 0.000 |

| ROC:受试者工作特征;AUC:ROC曲线下面积 | |||

肌力可通过骨应变影响骨细胞代谢活动,骨细胞可探测周围应变力的大小,并根据应变力的不同即肌肉的主动收缩不同,调整破骨和成骨活动,以改变骨局部的强度及骨量[16]。握力、单腿站立实验、大腿拉伸实验等都可反映BMD[17]。肌力下降是骨量降低的主要危险因素之一[18]。

握力是衡量肌肉力量的有效方法,是临床上最简单的肌肉功能评定方法[19],握力测定对肌少症的诊断也有一定的价值[20-22]。同时也是监测老龄化如跌倒等一系列表现的指标[22-24]。大量临床及基础实验证实握力与衰老的发生、发展密切相关[25-27]。本研究分析发现绝经后女性握力水平较绝经前女性明显降低。握力的大小受年龄影响,有研究表明人在20~30岁时握力达到峰值,40岁时保持峰值状态,随后男女握力均逐渐下降[28-30];25~50岁肌肉力量已逐渐减少,60岁以后肌肉力量下降40%[31]。这种变化除了与年龄相关外,还可能与体力活动减少,营养状况下降,以及体内如激素水平,生长因子和炎性反应因子的变化有关[32]。本研究发现握力独立于年龄这一因素,与各点BMD均呈正相关。BMD除受年龄影响,握力作为骨量独立的影响因素在本研究中也得到证实。既往研究报道也验证了肌力与骨量或骨折风险的密切关联[30]。有研究发现,握力检测的最大肌力可以作为评判骨骼机械特性的重要因素[12]。握力的大小与骨量流失及未来骨折的发生风险有关[33]。而绝经后妇女骨量的减少和肌力的减低同步发生并且与年龄相关[34],BMD和肌肉力量随着雌激素水平的下降而下降[35]。对于女性而言,围绝经期是骨量丢失最严重的时期,而围绝经期女性如有较好的握力会大大降低未来OP及骨折的发生风险[33]。Dixon等[36]研究发现握力低是BMD低的标志之一,同时在女性中握力低与脊椎骨折风险增加有关。芬兰的一项研究证实OP妇女比无OP妇女握力降低19%,如握力较高可以延缓腰椎及股骨颈骨量的流失[37]。另外,肌力与BMD间的关系还可能是因为肌肉的活动可以强化骨骼的负荷能力。所以,肌力的增加可以促进BMD的提升[38]。握力在脊柱及髋关节等远端部位与BMD的相关性均有报道[39]。一项土耳其研究表明手握力与绝经年限及年龄呈负相关,而与腰椎及股骨BMD呈正相关[40]。也有研究表明在女性人群中股骨BMD与髋关节外展肌力相关[41]。本研究握力高低不同人群存在明显的BMD差异,握力越高则各点BMD越高。有研究表明负荷骨的强度与全身脂肪组织以及肌肉力量有关[38]。还有研究认为机械力施加于骨骼可促进成骨并抑制骨吸收,而肌肉及肌肉功能的减少,会使其产生的作用力减少而导致机械刺激减少,而使骨骼被力量加载的时间减少从而导致成骨效应的减少[42-44]。而全身脂肪组织主要通过增加肌肉的脂肪浸润导致胰岛素信号通路损害而影响成骨细胞的骨形成[45]。因此老年所致的活动减少,或者不良的生活习惯如久坐、缺乏锻炼等都可能导致肌肉数量及力量的减少,最终影响BMD。因此,有些研究认为握力是筛查女性OP的工具之一[46]。Madsen等[47]发现股四头肌的强度与胫骨近端及前臂远端BMD有明显的相关性,所以有研究提出握力是作为绝经后妇女桡骨远端BMD的一个强有力的预测因子[46]。之前的一些研究也认为握力大小可以反映BMD[48-49],握力下降可以预测骨量减少和流失[50-52]。本研究分析了影响BMD的影响因素,发现握力是中轴骨的主要影响因素而非股骨颈及髋关节BMD的影响因素。Sirola等[37]发现中轴骨对肌力大小改变的反应与股骨颈对肌力改变的反应速度不一,这可能是因为结构不同即小梁(腰椎)与皮质(股骨颈)对肌力大小改变的反应速度不同所致。

OSTA指数是从亚洲人群中获得的仅有年龄和体质量组成的用来区分OP和非OP人群的指标[14]。OP正影响着全球2亿多人口,它所带来的是高昂的费用,显著的发病率及病死率[53-54]。DXA是诊断OP的金标准,但其本身存在诸多限制,如仪器昂贵、场地受限、检测费用高等问题。Koh等[13]在2001年提出了一项OP风险筛选公式名为OSTA,此公式以年龄及体质量两项变量进行计算,具体公式为(体质量-年龄)×0.2[13]。此公式根据所得结果将OP风险高低分为3组,OSTA<-4为OP高风险组,-4≤OSTA≤-1为OP中等风险组,OSTA>-1为OP低风险组。许多研究已经证实了OSTA指数对OP风险评估的价值[55-56]。这些研究提出对比DXA结果,当OSTA指数敏感度在80%~88%及特异度在54%~67%时对OP有较好的分类价值。OSTA指数计算简单,仅以年龄及体质量双变量进行计算,但是得到的结果却较为精确,其可能的原因有二:第一,年龄及体质量均是范围较为广泛的变量,相较其他变化较小的变量而言,其在模型中的贡献较大;第二,年龄的增长及较低的体质量与增加OP风险相关[57-58]。本研究选取了该项工具,评价OSTA单独或联合握力在发现骨量下降绝经后女性中的效力。发现BMD随OSTA指数下降而下降,此结果符合OSTA指数对OP的判断。同时,本研究还发现握力是腰椎BMD的独立影响因素,而OSTA指数是股骨颈及全髋BMD的独立危险因素,本研究提出握力联合OSTA指数用于预测骨量下降/OP患病的作用。通过ROC曲线,本研究发现握力联合OSTA指数优于单独使用握力敏感性和特异性都显著提高,AUC为0.810,说明两指标联合使用具有较好的筛查价值。作为两项简便易行、经济高效的手段,握力联合OSTA指数在临床上对OP筛查的前景值得期待。

本研究也存在一定局限性:(1)因为设备限制,仅仅进行了上肢肌力的检测,未测量反映其他肌群的指标。但已有研究指出肌力对不同部位、结构的BMD影响大小及速率均不相同[37],也有研究发现股四头肌与胫骨BMD及前臂BMD存在相关性以此支持肌力与BMD的关系可能存在位置特异性[47];(2)未录入骨折数据,对OP骨折的判断能力没有观察;(3)未进行肌肉量及脂肪量的检测,无法评估身体组成成分对握力及BMD的影响。

综上,此研究证明了握力可以成为筛查骨量异常的指标,且当其与OSTA指数联用时效果更为显著,可作为一个简单易行,价格低廉,方便操作的检测方法为OP的一级预防提供依据。

| [1] | Horstman AM, Dillon EL, Urban RJ, et al. The role of androgens and estrogens on healthy aging and longevity[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2012, 67: 1140–1152. DOI:10.1093/gerona/gls068 |

| [2] | Miyakoshi N, Hongo M, Mizutani Y, et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in Japanese women with osteopenia and osteoporosis[J]. J Bone Miner Metab, 2013, 31: 556–561. DOI:10.1007/s00774-013-0443-z |

| [3] | Otaka Y. Muscle and bone health as a risk factor of fall among the elderly. Sarcopenia and falls in older people[J]. Clin Calcium, 2008, 18: 761–766. |

| [4] | Woo N, Kim SH. Sarcopenia influences fall-related injuries in community-dwelling older adults[J]. Geriatr Nurs, 2014, 35: 279–282. DOI:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2014.03.001 |

| [5] | Matsumoto H, Tanimura C, Tanishima S, et al. Sarcopenia is a risk factor for falling in independently living Japanese older adults:A 2-year prospective cohort study of the GAINA study[J]. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2017, 17: 2124–2130. DOI:10.1111/ggi.2017.17.issue-11 |

| [6] | Roh YH, Koh YD, Noh JH, et al. Evaluation of sarcopenia in patients with distal radius fractures[J]. Arch Osteoporos, 2017, 12: 5. DOI:10.1007/s11657-016-0303-2 |

| [7] | Cawthon PM, Fullman RL, Marshall L, et al. Physical performance and risk of hip fractures in older men[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2008, 23: 1037–1044. DOI:10.1359/jbmr.080227 |

| [8] | Newman AB, Kupelian V, Visser M, et al. Sarcopenia:alternative definitions and associations with lower extremity function[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2003, 51: 1602–1609. DOI:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51534.x |

| [9] | Lauretani F, Russo CR, Bandinelli S, et al. Age-associated changes in skeletal muscles and their effect on mobility:an operational diagnosis of sarcopenia[J]. J Appl Physiol (1985), 2003, 95: 1851–1860. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00246.2003 |

| [10] | Marin RV, Pedrosa MA, Moreira-Pfrimer LD, et al. Association between lean mass and handgrip strength with bone mineral density in physically active postmenopausal women[J]. J Clin Densitom, 2010, 13: 96–101. DOI:10.1016/j.jocd.2009.12.001 |

| [11] | Rikkonen T, Sirola J, Salovaara K, et al. Muscle strength and body composition are clinical indicators of osteoporosis[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2012, 91: 131–138. DOI:10.1007/s00223-012-9618-1 |

| [12] | Hasegawa Y, Schneider P, Reiners C. Age, sex, and grip strength determine architectural bone parameters assessed by peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) at the human radius[J]. J Biomech, 2001, 34: 497–503. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9290(00)00211-6 |

| [13] | Koh LK, Sedrine WB, Torralba TP, et al. A simple tool to identify asian women at increased risk of osteoporosis[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2001, 12: 699–705. DOI:10.1007/s001980170070 |

| [14] | Richy F, Gourlay M, Ross PD, et al. Validation and comparative evaluation of the osteoporosis self-assessment tool (OST) in a Caucasian population from Belgium[J]. QJM, 2004, 97: 39–46. DOI:10.1093/qjmed/hch002 |

| [15] | Montalcini T, Migliaccio V, Yvelise F, et al. Reference values for handgrip strength in young people of both sexes[J]. Endocrine, 2013, 43: 342–345. DOI:10.1007/s12020-012-9733-9 |

| [16] | Frost HM. Defining osteopenias and osteoporoses:another view (with insights from a new paradigm)[J]. Bone, 1997, 20: 385–391. DOI:10.1016/S8756-3282(97)00019-7 |

| [17] | Karkkainen M, Rikkonen T, Kroger H, et al. Physical tests for patient selection for bone mineral density measurements in postmenopausal women[J]. Bone, 2009, 44: 660–665. DOI:10.1016/j.bone.2008.12.010 |

| [18] | Ferrucci L, Russo CR, Lauretani F, et al. A role for sarcopenia in late-life osteoporosis[J]. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2002, 14: 1–4. DOI:10.1007/BF03324410 |

| [19] | Visser M, Deeg DJ, Lips P, et al. Skeletal muscle mass and muscle strength in relation to lower-extremity performance in older men and women[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2000, 48: 381–386. DOI:10.1111/jgs.2000.48.issue-4 |

| [20] | Sayer AA, Robinson SM, Patel HP, et al. New horizons in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of sarcopenia[J]. Age Ageing, 2013, 42: 145–150. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afs191 |

| [21] | Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults:evidence for a phenotype[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2001, 56: M146–156. DOI:10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 |

| [22] | Cooper C, Fielding R, Visser M, et al. Tools in the assessment of sarcopenia[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2013, 93: 201–210. DOI:10.1007/s00223-013-9757-z |

| [23] | Garcia-Pena C, Garcia-Fabela LC, Gutierrez-Robledo LM, et al. Handgrip strength predicts functional decline at discharge in hospitalized male elderly:a hospital cohort study[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8: e69849. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0069849 |

| [24] | Sallinen J, Stenholm S, Rantanen T, et al. Hand-grip strength cut points to screen older persons at risk for mobility limitation[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2010, 58: 1721–1726. DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03035.x |

| [25] | Rantanen T, Guralnik JM, Foley D, et al. Midlife hand grip strength as a predictor of old age disability[J]. JAMA, 1999, 281: 558–560. DOI:10.1001/jama.281.6.558 |

| [26] | Cooper R, Kuh D, Cooper C, et al. Objective measures of physical capability and subsequent health:a systematic review[J]. Age Ageing, 2011, 40: 14–23. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afq117 |

| [27] | Cooper R, Kuh D, Hardy R, et al. Objectively measured physical capability levels and mortality:systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. BMJ, 2010, 341: c4467. DOI:10.1136/bmj.c4467 |

| [28] | Angst F, Drerup S, Werle S, et al. Prediction of grip and key pinch strength in 978 healthy subjects[J]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2010, 11: 94. DOI:10.1186/1471-2474-11-94 |

| [29] | Bassey EJ, Harries UJ. Normal values for handgrip strength in 920 men and women aged over 65 years, and longitudinal changes over 4 years in 620 survivors[J]. Clin Sci (Lond), 1993, 84: 331–337. DOI:10.1042/cs0840331 |

| [30] | Bohannon RW. Hand-grip dynamometry predicts future outcomes in aging adults[J]. J Geriatr Phys Ther, 2008, 31: 3–10. DOI:10.1519/00139143-200831010-00002 |

| [31] | Hakkinen K, Kraemer WJ, Kallinen M, et al. Bilateral and unilateral neuromuscular function and muscle cross-sectional area in middle-aged and elderly men and women[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 1996, 51: B21–29. |

| [32] | Clark BC, Manini TM. Sarcopenia=/=dynapenia[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2008, 63: 829–834. DOI:10.1093/gerona/63.8.829 |

| [33] | Sirola J, Rikkonen T, Tuppurainen M, et al. Association of grip strength change with menopausal bone loss and related fractures:a population-based follow-up study[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2006, 78: 218–226. DOI:10.1007/s00223-005-0298-y |

| [34] | Blain H, Vuillemin A, Teissier A, et al. Influence of muscle strength and body weight and composition on regional bone mineral density in healthy women aged 60 years and over[J]. Gerontology, 2001, 47: 207–212. DOI:10.1159/000052800 |

| [35] | Phillips SK, Rook KM, Siddle NC, et al. Muscle weakness in women occurs at an earlier age than in men, but strength is preserved by hormone replace-ment therapy[J]. Clin Sci (Lond), 1993, 84: 95–98. DOI:10.1042/cs0840095 |

| [36] | Dixon WG, Lunt M, Pye SR, et al. Low grip strength is associated with bone mineral density and vertebral fracture in women[J]. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2005, 44: 642–646. DOI:10.1093/rheumatology/keh569 |

| [37] | Sirola J, Tuppurainen M, Honkanen R, et al. Associations between grip strength change and axial postmenopausal bone loss-a 10-year population-based follow-up study[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2005, 16: 1841–1848. DOI:10.1007/s00198-005-1944-y |

| [38] | Frost HM. A 2003 update of bone physiology and Wolff's Law for clinicians[J]. Angle Orthod, 2004, 74: 3–15. |

| [39] | Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett-Connor E. Grip strength and bone mineral density in older women[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 1994, 9: 45–51. |

| [40] | Park JH, Park KH, Cho S, et al. Concomitant increase in muscle strength and bone mineral density with decreasing IL-6 levels after combination therapy with alendronate and calcitriol in postmenopausal women[J]. Menopause, 2013, 20: 747–753. DOI:10.1097/GME.0b013e31827cabca |

| [41] | Bayramoglu M, Sozay S, Karatas M, et al. Relation-ships between muscle strength and bone mineral density of three body regions in sedentary postmenopausal women[J]. Rheumatol Int, 2005, 25: 513–517. DOI:10.1007/s00296-004-0475-8 |

| [42] | Verschueren S, Gielen E, O'Neill TW, et al. Sarcopenia and its relationship with bone mineral density in middle-aged and elderly European men[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2013, 24: 87–98. |

| [43] | Rochefort GY, Pallu S, Benhamou CL. Osteocyte:the unrecognized side of bone tissue[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2010, 21: 1457–1469. DOI:10.1007/s00198-010-1194-5 |

| [44] | Marcell TJ. Sarcopenia:causes, consequences, and preventions[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2003, 58: M911–916. DOI:10.1093/gerona/58.10.M911 |

| [45] | Fulzele K, Riddle RC, DiGirolamo DJ, et al. Insulin receptor signaling in osteoblasts regulates postnatal bone acquisition and body composition[J]. Cell, 2010, 142: 309–319. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.002 |

| [46] | Di Monaco M, Di Monaco R, Manca M, et al. Handgrip strength is an independent predictor of distal radius bone mineral density in postmenopausal women[J]. Clin Rheumatol, 2000, 19: 473–476. DOI:10.1007/s100670070009 |

| [47] | Madsen OR, Schaadt O, Bliddal H, et al. Relationship between quadriceps strength and bone mineral density of the proximal tibia and distal forearm in women[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 1993, 8: 1439–1444. |

| [48] | Karkkainen M, Rikkonen T, Kroger H, et al. Association between functional capacity tests and fractures:an eight-year prospective population-based cohort study[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2008, 19: 1203–1210. DOI:10.1007/s00198-008-0561-y |

| [49] | Sirola J, Rikkonen T, Tuppurainen M, et al. Grip strength may facilitate fracture prediction in perimenopausal women with normal BMD:a 15-year population-based study[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2008, 83: 93–100. DOI:10.1007/s00223-008-9155-0 |

| [50] | Kroger H, Tuppurainen M, Honkanen R, et al. Bone mineral density and risk factors for osteoporosis-a population-based study of 1600 perimenopausal women[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 1994, 55: 1–7. DOI:10.1007/BF00310160 |

| [51] | Nguyen TV, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA. Bone loss, physical activity, and weight change in elderly women:the Dubbo osteoporosis epidemiology study[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 1998, 13: 1458–1467. DOI:10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.9.1458 |

| [52] | Wallace BA, Cumming RG. Systematic review of randomized trials of the effect of exercise on bone mass in pre-and postmenopausal women[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2000, 67: 10–18. DOI:10.1007/s00223001089 |

| [53] | Lin JT, Lane JM. Osteoporosis:a review[J]. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2004, 425: 126–134. DOI:10.1097/01.blo.0000132404.30139.f2 |

| [54] | Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, et al. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2007, 22: 465–475. DOI:10.1359/jbmr.061113 |

| [55] | Park HM, Sedrine WB, Reginster JY, et al. Korean experience with the OSTA risk index for osteoporosis:a validation study[J]. J Clin Densitom, 2003, 6: 247–250. DOI:10.1385/JCD:6:3:247 |

| [56] | Kung AW, Ho AY, Sedrine WB, et al. Comparison of a simple clinical risk index and quantitative bone ultrasound for identifying women at increased risk of osteoporosis[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2003, 14: 716–721. DOI:10.1007/s00198-003-1428-x |

| [57] | Margolis KL, Ensrud KE, Schreiner PJ, et al. Body size and risk for clinical fractures in older women. Study of osteoporotic fractures research group[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2000, 133: 123–127. |

| [58] | Dargent-Molina P, Poitiers F, Breart G, et al. In elderly women weight is the best predictor of a very low bone mineral density:evidence from the EPIDOS study[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2000, 11: 881–888. DOI:10.1007/s001980070048 |

| (收稿日期:2017-09-15) |