目前糖尿病已成为严重的公共健康问题,截至2017年全球有4.51亿糖尿病患者,预计到2045年,糖尿病患者将增加到6.93亿[1]。除了众所周知的肾和心血管并发症,脆性骨折的风险增加最近也被认为是1型和2型糖尿病的一个重要并发症[2]。但其发病机制目前尚不完全明确,大量研究发现1型糖尿病患者脆性骨折风险增加与骨密度(bone mineral density,BMD)降低有关,而2型糖尿病患者骨折风险增加与BMD无明确关联。关于2型糖尿病患者脆性骨折风险增加的机制仍在探索之中。

2型糖尿病与BMD1型糖尿病患者的BMD减低,是脆性骨折风险增加潜在机制之一。但2型糖尿病患者BMD的变化尚不十分确定。Oei等[3]对4 135名参与者进行一个长达12年的前瞻性研究,发现2型糖尿病患者血糖控制不佳者比血糖控制良好以及无糖尿病患者股骨颈的BMD高1.1%~5.6%。Hadzibegovic等[4]对130例绝经后2型糖尿病患者与166例非糖尿病患者行BMD测量,发现绝经后2型糖尿病妇女的BMD水平高于非糖尿病妇女。但是也有研究显示2型糖尿病患者BMD是降低或无差异的。Yaturu等[5]对3 458名非糖尿病男性和735名2型糖尿病男性行对照研究发现2型糖尿病患者髋部BMD是降低的。Majima等[6]对145名日本的2型糖尿病患者与95名非糖尿病患者行BMD测量时发现2型糖尿病患者桡骨远端的BMD和Z评分明显低于对照组。Liu等[7]对775例50岁以上男性患者进行了横断面研究发现2型糖尿病患者的BMD较对照组在脊柱和髋关节,骨股颈均没有明显差异。

BMD不同的检测部位结果也不统一。Sosa等[8]发现2型糖尿病患者腰椎BMD较非糖尿病患者高,而在前臂远端确没有明显异常。有研究显示2型糖尿病患者的BMD在股骨颈、髋部和脊柱分别升高4%、4%、6%,而在前臂部位并没有显著变化[9]。除此之外,Ho-Pham等[10]对2型糖尿病患者骨皮质及骨松质BMD分别进行测量发现,2型糖尿病患者骨松质的BMD较高而骨皮质较低。因此使用BMD来预测2型糖尿病患者脆性骨折风险似乎不可靠。

2型糖尿病与脆性骨折风险脆性骨折指受到轻微创伤或日常活动中即发生的骨折,是骨质疏松症的严重后果,常见部位是髋部、椎体、前臂远端、肱骨近端等。2型糖尿病患者的髋部骨折风险增加。1986年Nicodemus等[11]对居住在爱荷华州的3万余名绝经后妇女进行了一项前瞻性队列调查,随访11年后发现2型糖尿病女性患者发生髋部脆性骨折的风险比非糖尿病者高1.70倍,且病史持续时间越长,骨折率越高。同样Janghorbani等[12]发现女性2型糖尿病患者髋部脆性骨折风险是正常的2.2倍,且随糖尿病持续时间增加而增加。

多数研究也认为2型糖尿病患者脊柱骨折风险也是增高的。Kilpadi等[13]对拉丁美洲人行横断面研究发现2型糖尿病患者脊柱骨折风险是非糖尿病者的2倍。Melton等[14]报道2型糖尿病患者脊柱骨折风险为正常者的2.8倍,且男性患者骨折风险更高。但也有一些不同的研究报道,Gerdhem等[15]对1 132名随机招募的妇女研究发现2型糖尿病并不会增加骨折风险。Meta分析研究认为脊柱骨折风险还是增高的,Wang等[16]通过Meta分析认为2型糖尿病脊柱骨折风险为非糖尿病患者1.56倍。Wang等[17] Meta研究结果显示糖尿病患者椎体骨折是正常人的2.03倍。

目前关于2型糖尿病患者四肢脆性骨折风险的研究不太确定。Holmberg等[18]对约2万男性及1万名女性分析发现2型糖尿病患者肱骨近端和踝关节骨折的风险是对照组的1.21~1.33倍,但是前臂骨折的风险比对照组降低了12%。Liu等[19]的Meta分析研究显示2型糖尿病患者与下肢或踝关节骨折风险有显著相关性,为非糖尿病患者的2倍,但在手、足、前臂骨折风险无明显差异。Wang等[20]行Meta分析发现2型糖尿病患者上臂骨折风险增加1.47倍,踝关节骨折风险增加1.24倍,而在前臂远端无明显差异。

2型糖尿病患者脆性骨折风险增加的机制 跌倒风险增加跌倒风险增加是引起骨折风险增加最常见的因素之一,而2型糖尿病患者比非糖尿病患者更容易跌倒。Schwartz等[21]报道2型糖尿病女性患者1年1次跌倒率是非糖尿病女性患者的1.68倍。2型糖尿病患者跌倒风险增加可能与其并发症如周围和自主神经病变、视网膜病变、微血管并发症[22]以及并发症如肥胖[23]相关。

糖尿病周围神经病变患者的平衡控制不佳增加了跌倒风险。此外,Grewal等[24]研究认为,糖尿病周围神经病变患者的感觉和运动能力不足,动态平衡稳定性下降,同时本体感觉反馈不足、姿势平衡受损,导致跌倒风险较高。糖尿病视网膜病变是糖尿病患者视力下降的最常见原因视力受损可能是反复跌倒的内在危险因素。Klein等[25]进行了5年的随访发现跌倒风险的增加与视力受损相关。此外,研究报道视觉障碍对患者在坠落事件中起着关键作用,尤其是环境危害导致的绊倒、滑倒和坠落[26]。

肌少症肌少症指与增龄相关的进行性、全身肌量减少和或肌强度下降或肌肉生理功能减退。肌少症与活动障碍、跌倒、骨质疏松等密切相关。Kim等[27]报道2型糖尿病患者肌少症发生的风险比非糖尿病患者增加。Mori等[28]研究发现2型糖尿病是导致肌萎缩的独立危险因素,2型糖尿病患者肌萎缩风险较正常人高40%。而临床肌少症又与骨质疏松症密切相关,与非肌少症妇女相比,肌少症妇女患骨质疏松症的概率高12.9倍。Sjoblom等[29]发现肌少症者患骨质疏松症的风险是正常人的1.8倍。与此同时,大量研究报道肌少症亦会增加跌倒和骨折的风险。Ozturk等[30]报道肌萎缩能显著增加老年患者跌倒事件的发生。Landi等[31]评估了高龄人群中肌萎缩和2年跌倒风险之间的关系,排除年龄、性别和其他混杂因素外发现肌萎缩患者跌倒的风险比非肌萎缩者相比高出3倍以上。

骨强度变化目前很多研究发现2型糖尿病患者BMD较正常人增加或者正常,因此BMD不能评估2型糖尿病与脆性骨折风险。但骨强度降低应该是2型糖尿病引起脆性骨折风险增加的机制之一。

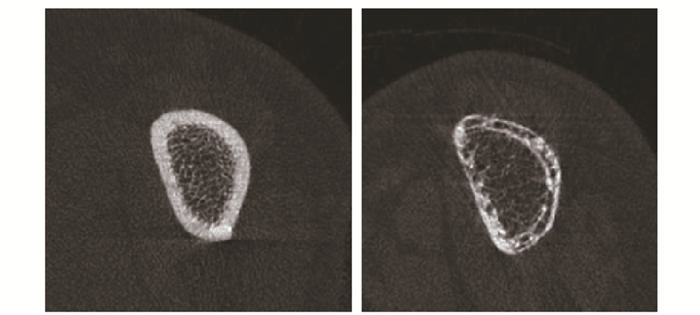

Farr等[32]对26例2型糖尿病患者及20名正常对照组的髂嵴骨样本进行定量组织学评估,发现糖尿病组的骨容量、类骨质容量、类骨质厚度、皮质骨厚度和成骨细胞表面积均显著降低。但在临床中,有创性操作实施起来比较困难,目前常使用高分辨率外围定量计算机断层扫描(high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography,HR-pQCT)进行骨微结构的测量及评估骨强度。Burghardt等[33]对19位老年女性糖尿病患者行对照研究,通过HR-pQCT测量其胫骨和桡骨皮质和小梁微结构,发现与对照组相比,2型糖尿病患者松质骨骨小梁增加,而皮质骨密度降低。此外,Patsch等[34]使用HR-pQCT测量发现2型糖尿病女性患者胫骨远端及桡骨远端骨皮质密度降低,骨皮质呈多孔性变化,严重的皮质骨质量缺陷是导致绝经后糖尿病妇女脆性骨折的原因。不仅如此,Heilmeier等[35]和Yu等[36]通过HR-pQCT评估2型糖尿病患者胫骨及腓骨皮质骨多孔性证实皮质骨质量缺陷可导致脆性骨折风险增加。2型糖尿病骨折患者桡骨远端及胫骨远端HR-pQCT(图 1,2)。

高血糖可直接影响成骨细胞和破骨细胞。体外研究表明,2型糖尿病患者的血清能抑制骨髓间充质干细胞向成骨细胞分化[38]。破骨细胞的体外研究表明,高血糖可降低破骨细胞数量、破骨细胞生成和破骨细胞活性[39]。高血糖对成骨细胞和破骨细胞的影响导致骨吸收和骨形成受损,从而导致糖尿病性骨疾病。

高血糖浓度导致骨基质中产生更多的糖基化终末产物(advanced glycation end products,AGEs)。在2型糖尿病动物模型中,一些研究显示骨组织中的AGEs含量增加[40]。AGEs与2型糖尿病患者骨质脆性增加密切相关。AGEs可改变蛋白质的特性,如胶原蛋白和层黏连蛋白,在骨骼中,这导致原本弹性的胶原蛋白纤维的脆性增加,并降低组织韧性[41]。此外,AGEs增加成骨细胞及其前体细胞的凋亡率[42],干扰成骨细胞和破骨细胞功能,并可能损害骨细胞应答。

细胞因子对骨代谢的影响胰岛素和胰岛素样生长因子1(Insulin like growth factor 1,IGF-1)分泌减少是糖尿病导致骨质疏松的主要原因。胰岛素对骨合成代谢起重要作用。胰岛素缺乏导致骨组织内糖蛋白和骨胶原合成不足、骨矿化不良。研究证实成骨细胞表面有胰岛素受体,胰岛素缺乏会降低成骨细胞活性,致骨吸收增强及骨量丢失,同时骨钙素合成减少。在胰岛素缺乏的糖尿病大鼠模型中,研究发现骨流失明显增多[43]。

IGF-1是一种多肽生长因子,多种组织均可产生。IGF-l可增加成骨细胞数目和活性,促进骨胶原基质形成,抑制骨胶原降解,调节骨吸收[44]。高血糖抑制IGF-1的合成和释放,使IGF-1减少,致成骨细胞功能减退,成骨细胞增生和分化受抑制。动物实验表明,成骨细胞表面IGF-1受体缺失的大鼠明显出现了骨矿化的不足[45]。

治疗糖尿病的药物多项研究调查了抗糖尿病药物对骨折风险的影响。其中噻唑烷二酮类和磺脲类被报道能增加骨折风险,其他降糖药如二甲双胍类、胰高血糖素样肽-1(glucagon-likepeptide 1, GLP-1)受体激动剂、二肽基肽酶4(dipeptidyl peptidase 4, DPP-4)抑制剂、钠/葡萄糖协同转运蛋白2(sodium/glucose co-transporter 2,SGLT-2)抑制剂等均未见文献报道能增加骨折风险。

Meier等[46]发现2型糖尿病患者长期使用噻唑烷二酮类药物脆性骨折风险比未使用者高,特别是髋部和手腕。Habib等[47]通过对19 070人进行回顾性队列研究发现使用噻唑烷二酮类药物的女性骨折风险是未使用者的1.35倍,而在男性患者中无明显区别。此外,Bazelier等[48]的Meta分析发现使用噻唑烷二酮类药物的女性骨折风险增加了1.2~1.5倍,而在男性中无区别。其作用机制可能是噻唑烷二酮类药物通过骨髓细胞中过氧化物酶体增生物激活受体γ(peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor γ, PPAR-γ)的激活增加骨丢失和骨折风险,并通过降低Runx2转录因子、IGF-1和Wnt信号通路阻碍成骨细胞的形成[49-51]。此外,有研究报道罗格列酮通过将成骨细胞募集转化为脂肪细胞而降低BMD[52]。该研究发现,罗格列酮组股骨颈BMD降低了1.34%±0.60%,而安慰剂组增加了0.28%±0.56%。罗格列酮组腰椎BMD下降1.03%±0.34%,安慰剂组下降0.42%±0.35%。

目前关于磺脲类药能否增加2型糖尿病患者脆性骨折风险还存在争议。Rajpathak等[53]对13 195名使用磺脲类药的患者与相同数量的未使用者进行平均长达4年的随访发现使用磺脲类药的患者髋部骨折风险是未使用者1.46倍。Lapane等[54]也曾报道过磺脲类药使用者骨折风险增加。但是,也有研究认为磺脲类药使用者骨折风险并不会增加[49]。Monami等[55]对1 945例糖尿病门诊患者行对照研究发现,接受磺脲类药物治疗的患者骨折风险较对照组降低。关于磺脲类药能否增加2型糖尿病患者脆性骨折风险还需进一步研究。

综上所述,目前普遍认为2型糖尿病患者脆性骨折风险增高。脆性骨折危害巨大,尤其是老年人群致残和致死的主要原因之一,给社会带来极大的负担。对于糖尿病患者医生不仅要关注其常见的心脑血管、肾脏、周围神经等并发症,还需要关注脆性骨折的风险。通过对骨折风险机制的不断深入研究,预防和降低脆性骨折的发生,对减轻患者及社会负担具有深远的意义。

| [1] | Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2018, 138: 271–281. DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.023 |

| [2] | Fukui T, Takahashi Y. Bone fragility in type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes[J]. Clin Calcium, 2019, 29: 51–56. |

| [3] | Oei L, Zillikens MC, Dehghan A, et al. High bone mineral density and fracture risk in type 2 diabetes as skeletal complications of inadequate glucose control: the Rotterdam Study[J]. Diabetes Care, 2013, 36: 1619–1628. DOI:10.2337/dc12-1188 |

| [4] | Hadzibegovic I, Miskic B, Cosic V, et al. Increased bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Ann Saudi Med, 2008, 28: 102–104. DOI:10.5144/0256-4947.2008.102 |

| [5] | Yaturu S, Humphrey S, Landry C, et al. Decreased bone mineral density in men with metabolic syndrome alone and with type 2 diabetes[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2009, 15: R5–R9. |

| [6] | Majima T, Komatsu Y, Yamada T, et al. Decreased bone mineral density at the distal radius, but not at the lumbar spine or the femoral neck, in Japanese type 2 diabetic patients[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2005, 16: 907–913. DOI:10.1007/s00198-004-1786-z |

| [7] | Liu M, Lu Y, Cheng X, et al. Relationship between abnormal glucose metabolism and osteoporosis in Han Chinese men over the age of 50 years[J]. Clin Interv Aging, 2019, 14: 445–451. DOI:10.2147/CIA.S164021 |

| [8] | Sosa M, Saavedra P, Jodar E, et al. Bone mineral density and risk of fractures in aging, obese post-menopausal women with type 2 diabetes. The GIUMO Study[J]. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2009, 21: 27–32. DOI:10.1007/BF03324895 |

| [9] | Ma L, Oei L, Jiang L, et al. Association between bone mineral density and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. Eur J Epidemiol, 2012, 27: 319–332. DOI:10.1007/s10654-012-9674-x |

| [10] | Ho-Pham LT, Chau P, Do AT, et al. Type 2 diabetes is associated with higher trabecular bone density but lower cortical bone density: the Vietnam Osteoporosis Study[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2018, 29: 2059–2067. DOI:10.1007/s00198-018-4579-5 |

| [11] | Nicodemus KK, Folsom AR. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes and incident hip fractures in postmenopausal women[J]. Diabetes Care, 2001, 24: 1192–1197. DOI:10.2337/diacare.24.7.1192 |

| [12] | Janghorbani M, Feskanich D, Willett WC, et al. Prospective study of diabetes and risk of hip fracture: the Nurses' Health Study[J]. Diabetes Care, 2006, 29: 1573–1578. DOI:10.2337/dc06-0440 |

| [13] | Kilpadi KL, Eldabaje R, Schmitz JE, et al. Type 2 diabetes is associated with vertebral fractures in a sample of clinic- and hospital-based Latinos[J]. J Immigr Minor Health, 2014, 16: 440–449. DOI:10.1007/s10903-013-9833-5 |

| [14] | Melton LR, Leibson CL, Achenbach SJ, et al. Fracture risk in type 2 diabetes: update of a population-based study[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2008, 23: 1334–1342. DOI:10.1359/jbmr.080323 |

| [15] | Gerdhem P, Isaksson A, Akesson K, et al. Increa-sed bone density and decreased bone turnover, but no evident alteration of fracture susceptibility in elderly women with diabetes mellitus[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2005, 16: 1506–1512. DOI:10.1007/s00198-005-1877-5 |

| [16] | Wang H, Ba Y, Xing Q, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of fractures at specific sites: a meta-analysis[J]. BMJ Open, 2019, 9: e24067. |

| [17] | Wang J, You W, Jing Z, et al. Increased risk of vertebral fracture in patients with diabetes: a meta-analysis of cohort studies[J]. Int Orthop, 2016, 40: 1299–1307. DOI:10.1007/s00264-016-3146-y |

| [18] | Holmberg AH, Johnell O, Nilsson PM, et al. Risk factors for fragility fracture in middle age. A prospective population-based study of 33, 000 men and women[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2006, 17: 1065–1077. DOI:10.1007/s00198-006-0137-7 |

| [19] | Liu J, Cao L, Qian Y W, et al. The association between risk of limb fracture and type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Oncotarget, 2018, 9: 31302–31310. |

| [20] | Wang H, Ba Y, Xing Q, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of fractures at specific sites: a meta-analysis[J]. BMJ Open, 2019, 9: e24067. |

| [21] | Schwartz AV, Hillier TA, Sellmeyer DE, et al. Older women with diabetes have a higher risk of falls: a prospective study[J]. Diabetes Care, 2002, 25: 1749–1754. DOI:10.2337/diacare.25.10.1749 |

| [22] | Sarodnik C, Bours S, Schaper NC, et al. The risks of sarcopenia, falls and fractures in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Maturitas, 2018, 109: 70–77. DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.12.011 |

| [23] | Walsh JS, Vilaca T. Obesity, type 2 diabetes and bone in adults[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2017, 100: 528–535. DOI:10.1007/s00223-016-0229-0 |

| [24] | Grewal GS, Schwenk M, Lee-Eng J, et al. Sensor-based interactive balance training with visual joint movement feedback for improving postural stability in diabetics with peripheral neuropathy: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Gerontology, 2015, 61: 567–574. DOI:10.1159/000371846 |

| [25] | Klein BE, Moss SE, Klein R, et al. Associations of visual function with physical outcomes and limitations 5 years later in an older population: the Beaver Dam eye study[J]. Ophthalmology, 2003, 110: 644–650. DOI:10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01935-8 |

| [26] | Reed-Jones RJ, Solis GR, Lawson KA, et al. Vision and falls: a multidisciplinary review of the contribu-tions of visual impairment to falls among older adults[J]. Maturitas, 2013, 75: 22–28. DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.01.019 |

| [27] | Kim TN, Park MS, Yang SJ, et al. Prevalence and determinant factors of sarcopenia in patients with type 2 diabetes: the Korean Sarcopenic Obesity Study (KSOS)[J]. Diabetes Care, 2010, 33: 1497–1499. DOI:10.2337/dc09-2310 |

| [28] | Mori K, Nishide K, Okuno S, et al. Impact of diabetes on sarcopenia and mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis[J]. BMC Nephrol, 2019, 20: 105. DOI:10.1186/s12882-019-1271-8 |

| [29] | Sjoblom S, Suuronen J, Rikkonen T, et al. Relationship between postmenopausal osteoporosis and the components of clinical sarcopenia[J]. Maturitas, 2013, 75: 175–180. DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.03.016 |

| [30] | Ozturk ZA, Turkbeyler IH, Abiyev A, et al. Health-related quality of life and fall risk associated with age-related body composition changes; sarcopenia, obesity and sarcopenic obesity[J]. Intern Med J, 2018, 48: 973–981. DOI:10.1111/imj.13935 |

| [31] | Landi F, Liperoti R, Russo A, et al. Sarcopenia as a risk factor for falls in elderly individuals: results from the iisirente study[J]. Clin Nutr, 2012, 31: 652–658. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2012.02.007 |

| [32] | Farr JN, Drake MT, Amin S, et al. In vivo assessment of bone quality in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2014, 29: 787–795. DOI:10.1002/jbmr.2106 |

| [33] | Burghardt AJ, Issever AS, Schwartz AV, et al. High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomographic imaging of cortical and trabecular bone microarchitecture in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2010, 95: 5045–5055. DOI:10.1210/jc.2010-0226 |

| [34] | Patsch JM, Burghardt AJ, Yap SP, et al. Increased cortical porosity in type 2 diabetic postmenopausal women with fragility fractures[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2013, 28: 313–324. |

| [35] | Heilmeier U, Cheng K, Pasco C, et al. Cortical bone laminar analysis reveals increased midcortical and periosteal porosity in type 2 diabetic postmenopausal women with history of fragility fractures compared to fracture-free diabetics[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2016, 27: 2791–2802. DOI:10.1007/s00198-016-3614-7 |

| [36] | Yu EW, Putman MS, Derrico N, et al. Defects in cortical microarchitecture among African-American women with type 2 diabetes[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2015, 26: 673–679. DOI:10.1007/s00198-014-2927-7 |

| [37] | Patsch JM, Burghardt AJ, Yap SP, et al. Increased cortical porosity in type 2 diabetic postmenopausal women with fragility fractures[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2013, 28: 313–324. DOI:10.1002/jbmr.1763 |

| [38] | Deng X, Xu M, Shen M, et al. Effects of type 2 diabetic serum on proliferation and osteogenic differentia-tion of mesenchymal stem cells[J]. J Diabetes Res, 2018, 2018: 5765478. |

| [39] | Xu J, Yue F, Wang J, et al. High glucose inhibits receptor activator of nuclear factorkappaB ligand-induced osteoclast differentiation via downregulation of vATPase V0 subunit d2 and dendritic cell specific transmembrane protein[J]. Mol Med Rep, 2015, 11: 865–870. DOI:10.3892/mmr.2014.2807 |

| [40] | Campbell GM, Tiwari S, Picke AK, et al. Effects of insulin therapy on porosity, non-enzymatic glycation and mechanical competence in the bone of rats with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Bone, 2016, 91: 186–193. DOI:10.1016/j.bone.2016.08.003 |

| [41] | Picke AK, Campbell G, Napoli N, et al. Update on the impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on bone metabolism and material properties[J]. Endocr Connect, 2019, 8: R55–R70. DOI:10.1530/EC-18-0456 |

| [42] | Alikhani M, Alikhani Z, Boyd C, et al. Advanced glycation end products stimulate osteoblast apoptosis via the MAP kinase and cytosolic apoptotic pathways[J]. Bone, 2007, 40: 345–353. DOI:10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.011 |

| [43] | Wei J, Ferron M, Clarke CJ, et al. Bone-specific insulin resistance disrupts whole-body glucose homeosta-sis via decreased osteocalcin activation[J]. J Clin Invest, 2014, 124: 1–13. |

| [44] | Xian L, Wu X, Pang L, et al. Matrix IGF-1 maintains bone mass by activation of mTOR in mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Nat Med, 2012, 18: 1095–1101. DOI:10.1038/nm.2793 |

| [45] | Kubota T, Elalieh HZ, Saless N, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor in mature osteoblasts is required for periosteal bone formation induced by reloading[J]. Acta Astronaut, 2013, 92: 73–78. DOI:10.1016/j.actaastro.2012.08.007 |

| [46] | Meier C, Kraenzlin ME, Bodmer M, et al. Use of thiazolidinediones and fracture risk[J]. Arch Intern Med, 2008, 168: 820–825. DOI:10.1001/archinte.168.8.820 |

| [47] | Habib ZA, Havstad SL, Wells K, et al. Thiazolidinedione use and the longitudinal risk of fractures in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2010, 95: 592–600. DOI:10.1210/jc.2009-1385 |

| [48] | Bazelier MT, de Vries F, Vestergaard P, et al. Risk of fracture with thiazolidinediones: an individual patient data meta-analysis[J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2013, 4: 11. |

| [49] | Meier C, Schwartz AV, Egger A, et al. Effects of diabetes drugs on the skeleton[J]. Bone, 2016, 82: 93–100. DOI:10.1016/j.bone.2015.04.026 |

| [50] | Palermo A, D'Onofrio L, Eastell R, et al. Oral anti-diabetic drugs and fracture risk, cut to the bone: safe or dangerous? A narrative review[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2015, 26: 2073–2089. DOI:10.1007/s00198-015-3123-0 |

| [51] | Chandran M. Diabetes drug effects on the skeleton[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2017, 100: 133–149. DOI:10.1007/s00223-016-0203-x |

| [52] | Harslof T, Wamberg L, Moller L, et al. Rosiglitaz-one decreases bone mass and bone marrow fat[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2011, 96: 1541–1548. DOI:10.1210/jc.2010-2077 |

| [53] | Rajpathak SN, Fu C, Brodovicz KG, et al. Sulfonylurea use and risk of hip fractures among elderly men and women with type 2 diabetes[J]. Drugs Aging, 2015, 32: 321–327. DOI:10.1007/s40266-015-0254-0 |

| [54] | Lapane KL, Yang S, Brown MJ, et al. Sulfonylureas and risk of falls and fractures: a systematic review[J]. Drugs Aging, 2013, 30: 527–547. DOI:10.1007/s40266-013-0081-0 |

| [55] | Monami M, Cresci B, Colombini A, et al. Bone fractures and hypoglycemic treatment in type 2 diabetic patients: a case-control study[J]. Diabetes Care, 2008, 31: 199–203. DOI:10.2337/dc07-1736 |

| (收稿日期:2019-04-18) |