肌肉骨骼系统在保持体位、完成运动、保护重要内脏器官及机体内环境稳态等方面发挥着重要作用。肌肉与骨骼不仅位置毗邻、功能相辅,并受到神经、内分泌、免疫、营养、力学刺激的系统性调节,以及两者间内分泌、旁分泌和机械力学的局部相互调节。此外,骨骼和肌肉间还存在某些相似的分子信号调节通路,有望成为干预的共同靶点。随着社会人口老龄化,肌肉骨骼疾病已经成为重要的公共健康问题。肌肉减少症(sarcopenia,简称肌少症)、骨质疏松症(osteoporosis)和骨折的发生均随增龄而增加,肌少症和骨质疏松症相伴出现被统称为“活动障碍综合征”(dysmobility syndrome),致使老年人易于跌倒和骨折,继而成为老年人群致残、致死的主要原因之一[1-2]。与骨质疏松症相比,肌少症近10年来才逐渐受到重视,并在基础和临床研究方面取得了重要进展,国外相关学会相继颁布了肌少症的临床指南。为了提高医务工作者对肌少症的认识、规范我国肌少症的临床诊疗工作,中华医学会骨质疏松和骨矿盐疾病分会组织并编撰此共识。本共识主要涵盖肌少症的定义、流行病学特点、发病机制、肌肉与骨骼的相互作用、肌少症与骨折的关系、肌少症的诊断及肌少症的防治等内容。

肌少症的定义肌少症(sarcopenia)或称“肌肉减少症”,源于希腊语,“sarx”意为肌肉,“penia”意为减少或丢失,这是个新名词,于1989年由Rosenberg首次命名[3]。2010年欧洲老年肌少症工作组(European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People,EWGSOP)发表了肌少症共识[4]。此后,国际肌少症工作组(International Working Group on Sarcopenia,IWGS)也公布了新共识[5],将肌少症定义为:“与增龄相关的进行性、全身肌量减少和/或肌强度下降或肌肉生理功能减退”。

肌少症与活动障碍、跌倒、低骨密度及代谢紊乱密切相关,是老年人生理功能逐渐减退的重要原因和表现之一。肌少症会增加老年人的住院率及医疗花费,严重影响老年人的生活质量,甚至缩短老年人的寿命[6-8]。

老年人肌少症的流行病学及发病机制 肌少症的流行病学目前报道的肌少症患病率存在较大差异,可能受到研究人群和参考人群的影响。所使用评价肌肉质量、肌肉强度和肌力状态的方法和阈值不同,导致肌少症的患病率各异,但不同人群间肌少症患病率确实存在差异[9]。

采用生物电阻抗方法对14 818名年龄大于18岁的美国人群(30%年龄>60岁),测算骨骼肌质量指数(skeletal muscle mass index,SMI)显示肌少症患病率,结果SMI较峰值小于1个标准差的男女性分别为45%及59%;SMI较峰值小于2个标准差的男女性别分别为7%及10%[10]。应用双能X线吸收仪(dual X ray absorptiometry,DXA)的检测方法,对465 名加拿大老年男女性的研究显示,男性肌少症患病率为38.9%,女性为17.8%[11]。澳大利亚一项对平均年龄86岁的63名女性的研究示:Ⅰ°肌少症患病率为25.4%,Ⅱ°肌少症患病率为3.2%[12]。对平均年龄为72.5岁英国社区老年人的调查显示,男女性肌少症患病率分别为4.6%和7.9%[13],而比利时社区老人调查结果显示肌少症患病率为3.7%[14]。

在亚洲,老年人肌少症的估计患病率为4.1%~11.5%[15-18]。上海地区对18~96岁健康男女性别的调查结果提示:>70岁男女性肌少症的患病率分别为12.3%及4.8%;而高龄农村男女性肌少症患病率为6.4%及11.5%,相关危险因素包括性别、年龄、乙醇消耗量、消化性溃疡[15]。香港社区老年男性的肌少症患病率为9.4%,与高龄、认知功能低下、蛋白质或维生素摄入低有关[16]。中国台湾地区老年男女性肌少症患病率分别为9.3%和4.1%,与语言表达能力障碍有关[18];日本老年男、女性肌少症患病率分别为9.6%和7.7%[17];韩国 50岁以上女性肌少症患病率为12.1%[19]。

采用不同肌少症评估方法和诊断标准,以及调查不同人群,肌少症的患病率差异较大,具体如下[20-37]:老年男性肌少症患病率为0~85.4%,老年女性为0.1%~33.6%;应用DXA测量肌肉量,男性肌少症患病率为0~56.7%,女性患病率为0.1%~33.9%;应用生物电阻抗法测量肌肉量,男女性肌少症患病率分别为6.2%~85.4%及2.8%~23.6%;社区老年居民肌少症患病率为1%~29%,长期居住于护理院人群的肌少症患病率为14%~33%,急诊老年人肌少症患病率为10%;肌少症患病率随增龄而增加,与性别相关,男性似乎更容易罹患肌少症。

据推测,全球目前约有5千万人罹患肌少症,预计到2050年患此症的人数将高达5亿。亚洲老年人肌少症患病率低于欧美人群,可能因为亚洲人群的RASM临界值低于美国人群(男性分别为5.72 kg/m2∶7.26 kg/m2,女性分别为4.82 kg/m2∶5.45 kg/m2),即使采用身高校正之后,亚洲年轻人群平均峰值RASM仍然较高加索人群约低15%[38]。总之,肌少症将是未来面临的主要健康问题之一。

肌少症的发病机制肌少症是增龄相关疾病,是环境和遗传因素共同作用的复杂疾病,多种风险因素和机制参与其发生[39-40],肌少症的发病机制涉及如下多个方面:

运动减少:增龄相关的运动能力下降是老年人肌肉量和强度丢失的主要因素[39, 41]。长期卧床者肌肉强度的下降要早于肌肉量的丢失,活动强度不足导致肌力下降,而肌肉无力又使活动能力进一步降低,最终肌肉量和肌肉强度均下降[42]。较多研究提示老年人进行阻抗运动能显著增加肌肉量、肌肉强度和肌肉质量[43]。

神经-肌肉功能减弱:运动神经元的正常功能对肌纤维的存活是必需的,在肌少症发病机制中α运动神经元的丢失是关键因素,研究发现老年人70岁以后运动神经元数量显著减少,α运动神经元丢失达50%,显著影响下肢功能[44-45]。老年时期α运动神经元和运动单元数量的显著减少直接导致肌肉协调性下降和肌肉强度的减弱。在肌肉纤维数量上,对成人肌肉的研究发现,90岁时肌肉中Ⅰ型和Ⅱ型纤维含量仅为年轻人的一半[46-47]。老年时期,由于星状细胞数量和募集能力下降,导致Ⅱ型纤维比Ⅰ型纤维下降更显著。星状细胞是肌源性干细胞,可在再生过程中被激活,分化为新肌纤维和新星状细胞,但是这种再生过程在应对损伤时将导致Ⅱ型纤维不平衡和数量减少,且老年人肌肉更易损和难修复。

增龄相关激素变化:胰岛素、雌激素、雄激素、生长激素和糖皮质激素等的变化参与肌少症的发病。肌少症时,身体和肌细胞内脂肪增加,这与胰岛素抵抗有关[48-50]。实验已证实老化肌细胞接受胰岛素作用后,蛋白生成能力明显降低[51]。雌激素对肌少症的发病作用存在不一致的证据,一些流行病学和干预研究提示雌激素可以预防肌肉量的丢失。对5项随机对照临床试验进行的系统分析,3项研究表明雌激素替代治疗后肌肉强度增加,但不影响身体成分分布,一项研究表明替勃龙增加股四头肌和膝伸直肌强度,且增加瘦组织量、降低体脂量[52]。一项对健康、老化和身体成分的研究,发现雌激素替代治疗后,股四头肌横断面面积更高,但与膝伸直肌强度无关[53]。可见,雌激素主要影响肌肉强度,在肌少症发病中可能不是最重要的因素。而男性睾酮水平随增龄每年下降1%,这在男性肌少症发病中起重要作用[54]。很多研究显示老年男性低睾酮水平与肌肉量、强度和功能的下降均相关,体外实验也证实睾酮可剂量依赖地促进星状细胞数量增加,且是其功能的主要调控因子[55]。此外,老年人维生素D缺乏非常普遍,多项研究证实维生素D缺乏是肌少症的风险因素,并且1,25双羟维生素D水平降低与肌肉量、肌肉强度、平衡力下降和跌倒风险增加相关[56-57]。

促炎性反应细胞因子:促炎性反应细胞因子参与老年人肌少症的发病,研究发现血IL-6、TNF-α和C反应蛋白水平与肌肉量、肌肉强度有关[58]。荷兰老年人群的研究提示高水平IL-6和C反应蛋白使肌肉量和肌肉强度丢失风险增加[59]。这些炎性反应细胞因子增高引起肌肉组织合成代谢失衡,蛋白分解代谢增加。老年人炎性反应细胞因子长期增高是肌少症的重要危险因素。

肌细胞凋亡:肌肉活检显示老年人肌细胞凋亡显著高于年轻人,这是肌少症的基本发病机制[60],肌细胞凋亡与线粒体功能失常和肌肉量丢失有关。研究证实肌少症主要累及的Ⅱ型肌纤维更容易通过凋亡途径而死亡[61]。增龄、氧化应激、低生长因子以及完全制动等可触发Caspase依赖或非依赖的凋亡信号通路。

遗传因素:遗传因素可以分别解释个体间肌肉强度、下肢功能和日常生活能力变异的36%~65%、57%和34%[62-64]。肌少症的全基因组关联分析(genome-wide association studies,GWAS)数据较少,2009年对1 000例无亲缘关系美国白人进行的GWAS与瘦组织(lean mass)分析,发现甲状腺释放激素受体(thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor,TRHR)单核苷酸多态性(single nucleotide polymorphism,SNP)rs16892496 和rs7832552与瘦组织变异有关[65]。最近一项1 550例英国孪生子全基因DNA甲基化研究,发现一些基因DNA甲基化与肌肉量变异相关[66]。目前遗传学研究主要集中在一些候选基因SNP与肌少症的表型,包括身体肌肉量、脂肪量和肌肉强度等关联研究,涉及的基因有GDF-8、CDKN1A、MYOD1、CDK2、RB1、IGF1、IGF2、CNTF、ACTN3、ACE、PRDM16、METTL21C和VDR等[66-70]。尽管发现了一些与肌少症相关的风险基因,但是未得到不同种族、更多人群一致的证实。

营养因素:已证实老年人合成代谢率降低30%,其降低究竟与老年人营养、疾病、活动少有关,还是仅与增龄有关,仍有争议[39, 71]。老年人营养不良和蛋白质摄入不足可致肌肉合成降低,已有研究证实氨基酸和蛋白补充可直接促进肌肉蛋白合成,预防肌少症,推荐合适的饮食蛋白摄入量为每天每千克体质量1.0~1.2 g[71]。

肌肉与骨骼的相互作用 全身因素共同调节肌肉和骨骼肌肉和骨骼作为运动系统的两大重要组成部分,共同受机体多种因素的调节[72-74]。在生长发育过程中肌量与骨量密切相关[75],肌肉生长略快于骨骼,提示在成长期肌肉生长会促进骨量积累。老年期肌量和骨量也呈密切正相关。全身调节因素共同影响肌肉和骨骼的主要证据:由于成肌细胞和成骨细胞同源于多能间充质干细胞,因此肌肉和骨骼会受到某些相同的遗传因素的调控。GWAS研究提示myostatin、α-actinin 3、 proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-α (PGC-1α)、myocyte enhancer factor 2 C (MEF-2C)、GLYAT 和METTL21C等的编码基因同时与肌少症和骨质疏松症密切相关[76]。

重要的内分泌因子会同时影响肌肉和骨骼。老年人群中维生素D缺乏与肌少症和骨质疏松症的发生有关;GH/IGF-1轴对骨骼和肌肉产生共同调节,运动后IGF-1 水平升高可能是运动对肌肉和骨骼正性作用的纽带。男性雄激素剥夺治疗和女性绝经后均引起肌量丢失和骨量减少,表明性激素对肌肉骨骼具有重要调节作用。

某些疾病状态同时累及肌肉和骨骼。皮质醇增多症患者同时发生肌少症和骨质疏松症;糖尿病患者的代谢异常,特别是糖基化终末产物的堆积,导致肌少症和骨折风险增加;慢性炎性反应,如类风湿关节炎和炎性肠病,会同时引起肌少症和骨质疏松症。

老年人营养缺乏普遍存在,营养不良时肌少症和骨质疏松症可同时出现。力学刺激同时影响肌肉和骨骼,既直接刺激成肌细胞和成骨细胞的分化,又分别诱发肌肉和骨骼释放多种生物活性因子而相互调节。

肌肉与骨骼的相互调节肌肉和骨骼位置毗邻、相互调节、密不可分。二者任何一方的结构、功能改变均会对另一方造成显著影响,其机制包括力学作用和可能的化学作用两个方面。力学作用一方面指肌肉收缩产生的应力对骨骼的影响,另一方面指骨骼供肌肉附着作为肌肉运动的杠杆,支持肌肉;而化学作用是指肌肉与骨骼产生的活性物质通过内分泌或旁分泌的方式作用于对方。因此,维持肌肉健康不仅仅能增加肌强度,还能减少骨丢失,进一步改善骨强度;反之,维持骨骼健康也能进一步提高肌量和强度,降低跌倒风险。

肌肉对骨骼的调节: 肌肉可通过力学作用和可能的化学作用对骨骼产生影响。力学作用主要是通过肌肉收缩,对骨骼产生应力刺激,使骨密度和骨强度增加。有研究显示,刺激肌肉收缩能预防肢体悬吊失重动物的骨丢失,说明肌肉收缩在一定程度上能减少骨丢失。化学作用主要是指肌肉产生的化学物质可能通过旁分泌或内分泌机制作用于成骨(前体)细胞、破骨细胞或骨细胞,促进成骨和/或抑制破骨。MyoD和Myf5基因敲除小鼠由于缺乏骨骼肌,小鼠胚胎在母体子宫内无自主活动能力,出生后不能存活,骨骼表现为矿化不良,且新生骨中的破骨细胞数量增多,提示肌肉可促进骨骼发育[77]。由肌肉产生的骨诱导因子(osteoglycin,OGC)和FAM5C (family with sequence similarity 5,member C) 是重要的分泌型骨形成因子[78-79]。肌肉产生的其他内分泌因子包括IGF-1、白介素-15、白介素-7、白介素-15、骨连素、MMP-2和成纤维细胞生长因子等均可能影响骨代谢[79]。肌肉运动后产生的鸢尾素则可能通过Wnt-β-catenin 通路促进成骨细胞分化和RANKL/RANK途径抑制破骨细胞形成[80]。肌肉收缩的机械刺激能直接作用于骨细胞,影响其分泌硬骨素(sclerostin)等调节骨形成。肌肉生长抑制素(myostatin)主要在骨骼肌表达,肌肉生长抑制素功能缺失会引起肌肉肥厚、肌肉功能和骨量增加。肌肉生长抑制素敲除能抑制破骨细胞分化,说明骨骼肌的肌肉生长抑制素可能对破骨细胞的分化有促进作用[81]。可见,肌肉不仅通过力学作用,还可能通过生物活性因子的内分泌、旁分泌机制,影响骨骼发育及骨转换。但肌肉产生的化学因子对骨骼的作用究竟是直接作用还是通过影响肌力产生的间接作用,还有待进一步研究。

骨骼对肌肉的调节:骨骼也通过力学和化学作用对肌肉产生影响。成骨细胞或骨细胞分泌的因子,如骨钙素、硬骨素和成纤维细胞生长因子-23 等,均可能对肌肉有调节作用。骨钙素对肌肉会产生同化作用,骨骼中产生的骨钙素可能通过GPRC6A/AMPK/mTOR/S6 激酶途径调节肌量和功能[82-83]。骨钙素还可能影响糖脂和能量代谢进而影响肌肉功能。骨特异性因子羧基化骨钙素(Glu-OC)可部分修复功能受损的肌肉[83]。经典的Wnt信号通路的激活是肌肉分化所必需,骨细胞分泌的硬骨素和Indian Hedgehog (Ihh)等对Wnt信号通路有调控作用,表明骨细胞可能远程调节肌细胞的分化[84]。骨细胞和成骨细胞分泌的成纤维细胞因子-23 具有抑制肾小管重吸收磷和降低1α羟化酶活性的作用,可导致低磷血症和活性维生素D水平过低,由此会影响肌肉的代谢和功能,当然FGF-23对肌肉是否有直接调控作用还有待阐明[85]。此外,骨骼细胞中的特异性间隙连接蛋白Connexin43可直接参与肌肉生长和功能的调控[86]。但究竟骨骼对肌肉的影响是如何通过机械应力和生物因子共同协调发挥作用的,仍有待深入研究。

肌少症与骨质疏松及骨折如前所述,肌少症和骨质疏松症可统称为“活动障碍综合征”,因此,老年人群的骨折可视为两者的共同后果[1]。大量研究表明,老年人群骨折与肌量减少、肌力下降、跌倒增加、骨量减低密切关联。

多数大样本横断面研究显示,肌肉含量与骨密度呈正相关,肌肉含量下降是骨质疏松症的重要危险因素。一项对非洲裔美国人、高加索人及中国人的研究结果表明瘦肉含量及握力与骨密度呈正相关,四肢肌肉含量每增加一个标准差,骨量减少/骨质疏松的风险下降37%。肌少症者较正常人罹患骨量减少/骨质疏松的风险增加1.8倍[87]。韩国健康及营养调查结果显示,肌少症合并维生素D 缺乏组男女性全髋及股骨颈骨密度均显著降低[88]。我国上海研究结果显示,肌少症在70岁以上女性的患病率为4.8%,男性为13.2%,与日本及韩国患病率接近,但低于高加索人,受试者下肢及躯干肌肉含量分别是股骨与脊柱骨密度的强预测因子[89]。

肌少症不仅与低骨密度密切关联,也是髋部骨折的重要危险因素。有研究显示肌少症女性罹患骨质疏松症、骨折及1年内至少跌倒1次的风险显著升高,比值比分别为12.9、2.7及2.1[90]。日本横断面研究结果表明老龄、低骨密度及肌少症是髋部骨折的主要危险因素[91]。由此可见,肌少症是跌到及骨折的重要危险因素。

一项前瞻性随访10.7年的研究结果表明肌少症男性具有较低脊柱与全身骨密度,以及较高的非椎体骨折率;肌少症女性具有较低的全髋骨密度[92]。一项前瞻性研究表明降低的骨密度、肌肉量、肌肉强度、肌功能,以及增加的肌间脂肪含量,均与髋部骨折风险增高相关[93]。香港一项前瞻性研究随访11.3年结果表明,肌少症是低骨密度及其他骨折危险因素以外的骨折独立危险因素[94]。前瞻性研究更加有力地证实了肌少症、骨质疏松症是导致骨折的重要危险因素。

肌少症与骨质疏松症相互影响、紧密关联的机制较为复杂,包括肌肉收缩力学负荷对骨骼的影响,以及肌肉与骨骼间复杂精密内分泌调控的生物学机制[95-97]。肌肉力学刺激影响骨骼的生长、骨骼几何形状和骨密度[98]。骨骼与肌肉均起源于间充质祖细胞,它们受重叠基因及体液因子的调控。骨骼与肌肉之间相互交织的内分泌信号网络,决定了骨骼与肌肉的相互影响。许多共同信号通路参与调节肌细胞与骨骼细胞的代谢过程,包括Wnt/β-catenin信号通路、PI3K/Akt通路等[99-100]。在治疗方面,肌少症与骨质疏松症也有相通之处。

肌少症的诊断肌少症缺乏特异的临床表现,患者可表现为虚弱、容易跌倒、行走困难、步态缓慢、四肢纤细和无力等,其诊断有赖于肌力、肌强度和肌量的评估等方面。

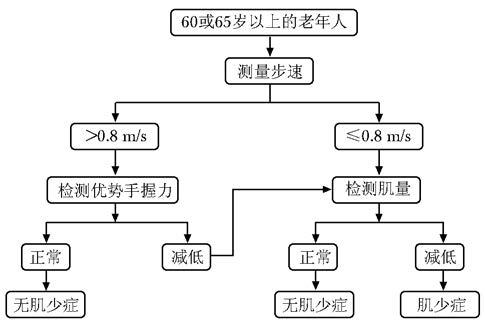

肌少症判定标准应综合肌量和肌肉功能的评估,主要评估指标有肌量(mass)减少、肌强度(strength)下降、日常活动功能(physical performance)失调等。1998年Baumgartner等[101]基于DXA肌肉量测量,提出了肌量减少的诊断标准。该标准以身高校正后的四肢肌量为参照指标[四肢肌量(kg)/身高2(m2)],如低于青年健康人峰值的-2SD可诊断肌量减少,具体诊断阈值为:男性<7.26 kg/m2、女性<5.45 kg/m2。亚洲肌少症工作组的建议:以日常步速和握力作为筛查指标,该标准简便易行[102]。欧洲老年人群肌少症工作组建议用DXA或生物电阻抗法测定肌量,用手握力测定肌力,用步速或简易体能状况量表(short physical performance battery,SPPB)测定功能,每项评分与健康年轻人比较,分为前肌少症、肌少症及严重肌少症。鉴于肌少症的研究刚刚起步,国内相关数据及工作经验有限,因此参考国外的有关标准及我国现有的研究[101-104],建议筛查与评估步骤如下:(1)先行步速测试,若步速≤0.8 m/s,则进一步测评肌量;步速>0.8 m/s时,则进一步测评手部握力。(2)若静息情况下,优势手握力正常 (男性握力>25 kg,女性握力>18 kg),则排除肌少症;若肌力低于正常,则要进一步测评肌量。(3)若肌量正常,则排除肌少症;若肌量减低,则诊为肌少症(图 1)。

|

| 图 1 肌少症筛查与评估流程图 Figure 1 Flow chart of of sarcopenia screening and assessment |

肌量测定应首选DXA,也可根据实际情况选择MRI、CT或BIA测量。肌量诊断阈值:低于参照青年健康人峰值的-2SD,优势手握力结果可能受上肢骨关节疾病(如类风湿关节炎)和测量体位或姿势等因素的影响。年轻继发肌少症患者也可参照该流程进行评估。

肌少症的防治肌少症的防治对象包括所有的肌少症人群,包括各种疾病、药物和废用等所致的肌少症和老年性肌少症。防治措施包括运动疗法、营养疗法和药物治疗。

运动疗法运动是获得和保持肌量和肌力最为有效的手段之一。应鼓励自青少年期加强运动,以获得足够的肌量、肌力和骨量。在中老年期坚持运动以保持肌量、肌力和骨量。老年人运动方式的选择需要因人而异。采用主动运动和被动活动,肌肉训练与康复相结合的手段,达到增加肌量和肌力,改善运动能力和平衡能力,进而减少骨折的目的[105-107]。

营养疗法和维生素D补充大多数老年人存在热量和蛋白质摄入不足,因此,建议老年人在日常生活中要保持平衡膳食和充足营养,必要时考虑蛋白质或氨基酸营养补充治疗[108-109]。

维生素D不足和缺乏在人群中普遍存在,在不能经常户外活动的老年人中更是如此,此类患者往往表现为肌肉无力,活动困难等。在老年人群中,筛查维生素D缺乏的个体,补充普通维生素D对增加肌肉强度、预防跌倒和骨折更有意义[110-111]。

药物治疗目前还没有以肌少症为适应证的药物,临床上治疗其他疾病的部分药物可能使肌肉获益,进而扩展用于肌少症。包括同化激素、活性维生素D、β肾上腺能受体兴奋剂、血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂、生长激素等。

同化激素/选择性雄激素受体调节剂(selective androgen receptor modulators,SARMs):前者包括睾酮及合成类固醇激素。睾酮不仅可增加骨密度和骨强度,还可增加老年人的肌强度,低剂量睾酮能增加肌量和减少脂肪量,而大剂量睾酮则可同时增加肌量和肌力,对男性和女性均有效[112-113]。安全性方面,Meta分析表明老年人使用睾酮并未增加病死率,但也有研究提示补充睾酮3个月内会增加心脏事件。诺龙(nandrolone)是注射用合成类固醇激素,可增加肌纤维面积和肌量,但对肌强度、机体功能状态并未发现有益的影响[114]。SARM类药物(MK-0773、LGD-4033、 BMS-564929、Enobosarm等)尚在进行临床研究,对瘦肉量、肌量可能有益,但整体而言并不优于睾酮[115-117]。

活性维生素D:常用于65岁以上的老年人,在中华医学会原发性骨质疏松诊疗指南中也有类似推荐[118]。1α,25-双羟维生素 D3和艾迪骨化醇(活性维生素D类似物)可诱导成肌细胞的分化[119]。活性维生素D使用可增加肌肉强度和减少跌倒风险。但是还缺少使用活性维生素D增加肌量的直接证据。Meta分析表明使用阿法骨化醇治疗1年的患者其外周SMI无显著变化,而下肢肌量明显增加;而对照组在1年后SMI显著降低,下肢肌量无显著变化[120]。

生长激素类药物:研究提示生长激素可增加老年人的瘦肉量和肌量,与睾酮联合应用可在8周内增加肌量,在17周达到最大肌肉强度。不良反应包括关节肌肉疼痛、水肿、腕管综合征和高血糖、心血管疾病风险、男性乳房发育等[121]。生长激素释放肽Ghrelin会增加摄食和生长激素分泌,研究显示其可使癌症患者、老年肌少症患者摄食增加和获得肌量,安全性方面还需要进一步观察[122-123]。

交感神经β2受体兴奋剂:克伦特罗(clenbuterol)在心力衰竭患者中能使肌量增加;然而,丹麦大规模的病例对照研究表明使用短效β-兴奋剂会增加骨质疏松性骨折的危险,其他类型的β-兴奋剂对骨质疏松性骨折患者没有影响[124-125]。Espindolol是一种吲哚洛尔的S-对映体,能使高龄动物的肌量增加、脂肪量减少,Ⅱ期临床研究提示其可以增加肌量、握力和降低脂肪量[126]。

血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂(angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,ACEI):有研究显示培哚普利可增加左室收缩功能障碍老年人的行走距离[127]。HYVET研究表明培哚普利会降低髋部骨折的风险[128]。但尚缺少ACEI对骨骼肌作用的直接证据。

其他药物:如肌肉生长抑制素(Myostatin)抗体、活化素 Ⅱ受体配体捕获剂(ACE-031)等,可能改善肌量及瘦肉量,后者的动物研究显示其可增加猴子的骨量和骨强度,这些以肌肉为靶点的新型药物尚在研发当中[129-130]。

康复治疗康复治疗主要包括运动疗法和物理因子治疗,有氧运动和抗阻训练均能减少随着年龄增加的肌肉质量和肌肉力量的下降。对缺乏运动或受身体条件制约不能运动的老年人,可使用水疗、全身振动和功能性电刺激(functional electrical stimulation,FES)等物理治疗[131]。此外,其他物理因子,如电磁场、超声等在肌肉减少的防治中也有一定作用,但具体作用机制和应用条件还有待进一步明确。

总之,肌肉与骨骼具有密切关联。临床工作中应扩宽思路,提高对老年人群常常共存的两种疾病即肌少症与骨质疏松症的认识,应该同步考虑这两种密切相关疾病的诊断,并对肌少症给予积极有效的防治。

| [1] | Binkley N, Krueger D, Buehring B. What's in a name revisited: should osteoporosis and sarcopenia be considered components of "dysmobility syndrome?"[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2013, 24 : 2955–2959. DOI:10.1007/s00198-013-2427-1 |

| [2] | Edwards MH, Gregson CL, Patel HP, et al. Muscle size,strength,and physical performance and their associations with bone structure in the Hertfordshire Cohort Study[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2013, 28 : 2295–2304. DOI:10.1002/jbmr.1972 |

| [3] | Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance[J]. J Nutr, 1997, 127 : 990S–991S. |

| [4] | Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People[J]. Age Ageing, 2010, 39 : 412–423. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afq034 |

| [5] | Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence,etiology,and consequences. Internationalworkinggroup on sarcopenia[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2011, 12 : 249–256. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.003 |

| [6] | Landi F, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Liperoti R, et al. Sarcopenia and mortality risk in frail older persons aged 80 years and older: results from ilSIRENTE study[J]. Age Ageing, 2013, 42 : 203–209. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afs194 |

| [7] | Landi F, Russo A, Liperoti R, et al. Midarm muscle circumference,physical performance and mortality: results from the aging and longevity study in the Sirente geographic area (ilSIRENTE study)[J]. Clin Nutr, 2010, 29 : 441–447. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2009.12.006 |

| [8] | Yalcin A,Aras S,Atmis V,et al. Sarcopenia and mortality in older people living in a nursing home in Turkey[J]. Geriatr Gerontol Int,2016[Epub ahead of print]. |

| [9] | Kim H, Hirano H, Edahiro A, et al. Sarcopenia: Prevalence and associated factors based on different suggested definitions in community-dwelling older adults[J]. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2016, 16 : 110–122. DOI:10.1111/ggi.2016.16.issue-s1 |

| [10] | Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Ross R, et al. Lowrelative skeletal mucle mass (sarcopenia) in older persons is associated with functional impairment and physical disability[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2002, 50 : 889–896. DOI:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50216.x |

| [11] | Bouchard D, Dionne I, Brochu M, et al. Sarcopenic/obesity and physical capacity in older men and women:data from the nutrition as a determinant of successful aging (NuAge)-the Quebec longitudinal study[J]. Obesity:Silver Spring, 2009, 17 : 2082–2088. DOI:10.1038/oby.2009.109 |

| [12] | Woods J, Iuliano S, King S, et al. Poor physical function in elderly women in low-level aged care is related to muscle strength rather than to measures of sarcopenia[J]. Clin Interv Aging, 2011, 6 : 67–76. |

| [13] | Patel HP, Syddall HE, Jameson K, et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older people in the UK using the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) definition: findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study (HCS)[J]. Age Ageing, 2013, 42 : 378–384. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afs197 |

| [14] | Verschueren S, Gielen E, O'Neill TW, et al. Sarcopenia and its relationship with bone mineral density in middle-aged and elderly European men[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2013, 24 : 87–98. |

| [15] | Han P, Kang L, Guo Q, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with sarcopenia in suburb-dwelling older Chinese using the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia definition[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2016, 71 : 529–535. DOI:10.1093/gerona/glv108 |

| [16] | Yu R, Leung J, Woo J. Incremental predictive value of sarcopenia for incident fracture in an elderly Chinese cohort: Results from the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOs) Study[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2014, 15 : 551–558. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2014.02.005 |

| [17] | Yuki A, Ando F, Otsuka R, et al. Epidemiology of sarcopenia in elderly Japanese[J]. J Phys Fitness Sports Med, 2015, 4 : 111–115. DOI:10.7600/jpfsm.4.111 |

| [18] | Huang CY, Hwang AC, Liu LK, et al. Association of dynapenia,sarcopenia,and cognitive impairment among community-dwelling older Taiwanese[J]. Rejuvenation Res, 2016, 19 : 71–78. DOI:10.1089/rej.2015.1710 |

| [19] | Ryu M, Jo J, Lee Y, et al. Association of physical activity with sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity in community-dwelling older adults: The Fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey[J]. Age Ageing, 2013, 42 : 734–740. DOI:10.1093/ageing/aft063 |

| [20] | Abellan van Kan G, Cesari M, Gillette-Guyonnet S, et al. Sarcopenia and cognitive impairment in elderly women: results from the EPIDOS cohort[J]. Age Ageing, 2013, 42 : 196–202. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afs173 |

| [21] | Landi F, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Liperoti R, et al. Sarcopenia and mortality risk in frail older persons aged 80 years and older: results from ilsirente study[J]. Age Ageing, 2013, 42 : 203–209. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afs194 |

| [22] | Landi F, Liperoti R, Russo A, et al. Association of anorexia with sarcopenia in a community-dwelling elderly population: results from the ilsirente study[J]. Eur J Nutr, 2013, 52 : 1261–1268. DOI:10.1007/s00394-012-0437-y |

| [23] | Lee WJ, Liu LK, Peng LN, et al. Comparisons of sarcopenia defined by IWGS and EWGSOP criteria among older people: results from the I-Lan longitudinal aging study[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2013, 14 : 528. |

| [24] | Legrand D, Vaes B, Mathei C, et al. The prevalence of sarcopenia in very old individuals according to the European consensus definition: insights from the BELFRAIL study[J]. Age Ageing, 2013, 42 : 727–734. DOI:10.1093/ageing/aft128 |

| [25] | Malmstrom TK, Miller DK, Herning MM, et al. Low appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM) with limited mobility and poor health outcomes in middle-aged African Americans[J]. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2013, 4 : 179–186. DOI:10.1007/13539.2190-6009 |

| [26] | Mclntosh EI, Smale KB, Vallis LA. Predicting fat-free mass index and sarcopenia: a pilot study in community-dwelling older adults[J]. Age(Dordr), 2013, 35 : 2423–2434. |

| [27] | Murphy RA, Ip EH, Zhang Q, et al. Transition to sarcopenia and determinants of transitions in older adults: a population-based study[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2014, 69 : 751–758. DOI:10.1093/gerona/glt131 |

| [28] | Patel HP, Syddall HE, Jameson K, et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older people in the UK using the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) definition: findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study (HCS)[J]. Age Ageing, 2013, 42 : 378–384. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afs197 |

| [29] | Patil R, Uusi-Rasi K, Pasanen M, et al. Sarcopenia and osteopenia among 70-80-year-old home-dwelling Finnish women: prevalence and association with functional performance[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2013, 24 : 787–96. DOI:10.1007/s00198-012-2046-2 |

| [30] | Sanada K, Iemitsu M, Murakami H, et al. Adverse effects of coexistence of sarcopenia and metabolic syndrome in Japanese women[J]. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2012, 66 : 1093–1098. DOI:10.1038/ejcn.2012.43 |

| [31] | Tanimoto Y, Watanabe M, Sun W, et al. Association between sarcopenia and higher-level functional capacity in daily living in community-dwelling elderly subjects in Japan[J]. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2012, 55 : e9–13. DOI:10.1016/j.archger.2012.06.015 |

| [32] | Verschueren S, Gielen E, O'Neill TW, et al. Sarcopenia and its relationship with bone mineral density in middle-aged and elderly European men[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2013, 24 : 87–98. |

| [33] | Volpato S, Bianchi L, Cherubini A, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older people: application of the EWGSOP definition and diagnostic algorithm[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2014, 69 : 438–446. DOI:10.1093/gerona/glt149 |

| [34] | Yamada M, Nishiguchi S, Fukutani N, et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling Japanese older adults[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2013, 14 : 911–915. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.08.015 |

| [35] | Bastiaanse LP, Hilgenkamp TI, Echteld MA, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of sarcopenia in older adults with intellectual disabilities[J]. Res Dev Disabil, 2012, 33 : 2004–2012. DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2012.06.002 |

| [36] | Landi F, Liperoti R, Fusco D, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of sarcopenia among nursing home older residents[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2012, 67 : 48–55. |

| [37] | Gariballa S, Alessa A. Sarcopenia: prevalence and prognostic significance in hospitalized patients[J]. Clin Nutr, 2013, 32 : 772–776. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2013.01.010 |

| [38] | Chen LK, Liu LK, Woo J, et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2014, 15 : 95–101. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025 |

| [39] | Rolland Y, Czerwinski S, Kan G, et al. Sarcopenia: Its assessment,etiology,pathogenesis,consequences and future perspectives[J]. J Nutr Health Aging, 2008, 12 : 433–450. DOI:10.1007/BF02982704 |

| [40] | Lang T, Streeper P, Cawthon P, et al. Sarcopenia: etiology,consequences,intervention,and assessment[J]. Osteopros Int, 2010, 21 : 543–559. DOI:10.1007/s00198-009-1059-y |

| [41] | Goodpaster BH, Carlson CL, Visser M, et al. Attenuation of skeletal muscle and strength in the elderly: The Health ABC Study[J]. J Appl Physiol, 2001, 90 : 2157–2165. |

| [42] | Kortebein P, Ferrando A, Lombeida J, et al. Effect of 10 days of bed rest on skeletal muscle in healthy older adults[J]. JAMA, 2007, 297 : 1772–1774. |

| [43] | Hasten DL, Pak-Loduca J, Obert KA, et al. Resistance exercise acutely increases MHC and mixed muscle protein synthesis rates in 78-84 and 23-32 yr olds[J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2000, 278 : E620–606. |

| [44] | McComas AJ. 1998 ISEK Congress keynote lecture: motor units: how many,how large,what kind?International Society of Electrophysiology and Kinesiology[J]. J Electromyogr Kinesiol, 1998, 8 : 391–402. DOI:10.1016/S1050-6411(98)00020-0 |

| [45] | Doherty TJ. Invited review: aging and sarcopenia[J]. J Appl Physiol, 2003, 95 : 1717–1727. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00347.2003 |

| [46] | Larsson L, Grimby G, Karlsson J. Muscle strength and speed of movement in relation to age and muscle morphology[J]. J Appl Physiol, 1979, 46 : 451–456. |

| [47] | Larsson L, Sjodin B, Karlsson J. Histochemical and biochemical changes in human skeletal muscle with age in sedentary males,age 22-65 years[J]. Acta Physiol Scand, 1978, 103 : 31–39. DOI:10.1111/apha.1978.103.issue-1 |

| [48] | Chung SM, Hyun MH, Lee E, et al. Novel effects of sarcopenic osteoarthritis on metabolic syndrome,insulin resistance,osteoporosis,and bone fracture: the national survey[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2016, 27 : 2447–2457. DOI:10.1007/s00198-016-3548-0 |

| [49] | Koo BK, Roh E, Yang YS, et al. Difference between old and young adults in contribution of β-cell function and sarcopenia in developing diabetes mellitus[J]. J Diabetes Investig, 2016, 7 : 233–240. DOI:10.1111/jdi.2016.7.issue-2 |

| [50] | Volpi E, Mittendorfer B, Rasmussen BB, et al. The response of muscle protein anabolism to combined hyperaminoacidemia and glucose-induced hyperinsulinemia is impaired in the elderly[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2000, 85 : 4481–4490. |

| [51] | Guillet C, Prod'homme M, Balage M, et al. Impaired anabolic response of muscle protein synthesis is associated with S6K1 dysregulation in elderly humans[J]. FASEB J, 2004, 18 : 1586–1587. |

| [52] | Jacobsen DE, Samson MM, Kezic S, et al. Postmenopausal HRT and tibolone in relation to muscle strength and bodycomposition[J]. Maturitas, 2007, 58 : 7–18. DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.04.012 |

| [53] | Taaffe DR, Newman AB, Haggerty CL, et al. Estrogen replacement,muscle composition,and physical function: The Health ABC Study[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2005, 37 : 1741–1747. DOI:10.1249/01.mss.0000181678.28092.31 |

| [54] | Morley JE, Newman AB, Haggerty CL, et al. Longitudinal changes in testosterone,luteinizing hormone,and folliclestimulating hormone in healthy older men[J]. Metabolism, 1997, 46 : 410–413. DOI:10.1016/S0026-0495(97)90057-3 |

| [55] | Chen Y, Zajac JD, MacLean HE. Androgen regulation of satellite cell function[J]. J Endocrinol, 2005, 186 : 21–31. DOI:10.1677/joe.1.05976 |

| [56] | Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Willett WC, et al. Effect of vitamin D on falls: a meta-analysis[J]. JAMA, 2004, 291 : 1999–2006. DOI:10.1001/jama.291.16.1999 |

| [57] | Visser M, Deeg DJ, Lips P. Low vitamin D and high parathyroid hormone levels as determinants of loss of muscle strength and muscle mass (sarcopenia): the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2003, 88 : 5766–5772. DOI:10.1210/jc.2003-030604 |

| [58] | Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Baumgartner RN, et al. Sarcopenia,obesity,and inflammation-results from the trial of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition and novel cardiovascular risk factors study[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2005, 82(2) : 428–434. |

| [59] | Visser M, Pahor M, Taaffe DR, et al. Relationship of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha with muscle mass and muscle strength in elderly men and women: the Health ABC Study[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2002, 57 : 326–332. DOI:10.1093/gerona/57.5.M326 |

| [60] | Giresi PG, Stevenson EJ, Theilhaber J, et al. Identification of a molecular signature of sarcopenia[J]. Physiol Genomics, 2005, 21 : 253–263. DOI:10.1152/physiolgenomics.00249.2004 |

| [61] | Solomon A, Bouloux P. Endocrine therapies for sarcopenia in older men[J]. Br J Hosp Med:Lond, 2006, 67 : 477–481. DOI:10.12968/hmed.2006.67.9.22000 |

| [62] | Reed T, Fabsitz RR, Selby JV, et al. Genetic influences and grip strength norms in the NHLBI twin study males aged 59-69[J]. Ann Hum Biol, 1991, 18 : 425–432. DOI:10.1080/03014469100001722 |

| [63] | Arden NK, Spector TD. Genetic influences on muscle strength,lean body mass,and bone mineral density: a twin study[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 1997, 12 : 2076–2081. DOI:10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.12.2076 |

| [64] | Frederiksen H, Gaist D, Petersen HC, et al. Hand grip strength: a phenotype suitable for identifying genetic variants affecting mid-and late-life physical functioning[J]. Genet Epidemiol, 2002, 23 : 110–122. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1098-2272 |

| [65] | Liu XG, Tan LJ, Lei SF, et al. Genome-wide association and replication studies identified TRHR as an important gene for lean body mass[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 2009, 84 : 418–423. DOI:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.02.004 |

| [66] | Livshits G, Gao F, Malkin I, et al. Contribution of heritability and epigenetic factors to skeletal muscle mass variation in United Kingdom twins[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2016, 101 : 2450–2459. DOI:10.1210/jc.2016-1219 |

| [67] | Huygens W, Thomis MA, Peeters MW, et al. Linkage of myostatin pathway genes with knee strength in humans[J]. Physiol Genomics, 2004, 17 : 264–270. DOI:10.1152/physiolgenomics.00224.2003 |

| [68] | Zhang ZL, He JW, Qin YJ, et al. Association between myostatin gene polymorphisms and peak BMD variation in Chinese nuclear families[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2008, 19 : 39–47. DOI:10.1007/s00198-007-0435-8 |

| [69] | Yue H, He JW, Zhang H, et al. Contribution of myostatin gene polymorphisms to normal variation in lean mass,fat mass and peak BMD in Chinese male offspring[J]. Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2012, 33 : 660–667. DOI:10.1038/aps.2012.12 |

| [70] | Huang J, Hsu YH, Mo C, et al. METTL21C is a potential pleiotropic gene for osteoporosis and sarcopenia acting through the modulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2014, 29 : 1531–1540. DOI:10.1002/jbmr.2200 |

| [71] | Rizzoli R. Nutrition and sarcopenia[J]. J Clin Densitom, 2015, 18 : 483–487. DOI:10.1016/j.jocd.2015.04.014 |

| [72] | Dallas SL, Prideaux M, Bonewald LF. The osteocyte: an endocrine cell and more[J]. Endocr Rev, 2013, 34 : 658–690. DOI:10.1210/er.2012-1026 |

| [73] | DiGirolamo DJ, Clemens TL, Kousteni S. The skeleton as an endocrine organ[J]. Nat Rev Rheumatol, 2012, 8 : 674–683. DOI:10.1038/nrrheum.2012.157 |

| [74] | Pedersen BK. Muscles and their myokines[J]. J Exp Biol, 2011, 214 : 337–346. DOI:10.1242/jeb.048074 |

| [75] | Bonewald LF, Kiel DP, Clemens TL, et al. Forum on bone and skeletal muscle interactions: summary of the proceedings of an ASBMR workshop[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2013, 28 : 1857–1865. DOI:10.1002/jbmr.1980 |

| [76] | Urano T, Inoue S. Recent genetic discoveries in osteoporosis,sarcopenia and obesity[J]. Endocr J, 2015, 62 : 475–484. DOI:10.1507/endocrj.EJ15-0154 |

| [77] | Gomez C, David V, Peet NM, et al. 2007 Absence of mechanical loading in utero influences bone mass and architecture but not innervation in Myod-Myf5-deficient mice[J]. J Anat, 2007, 210 : 259–271. DOI:10.1111/joa.2007.210.issue-3 |

| [78] | Tagliaferri C, Wittrant Y, Davicco MJ, et al. Muscle and bone,two interconnected tissues[J]. Ageing Res Rev, 2015, 21 : 55–70. DOI:10.1016/j.arr.2015.03.002 |

| [79] | Kawao N, Kaji H. Interactions between muscle tissues and bone metabolism[J]. J Cell Biochem, 2015, 116 : 687–695. DOI:10.1002/jcb.v116.5 |

| [80] | Colaianni G,Cuscito C,Mongelli T,et al. The myokine irisin increases cortical bone mass[J]. Proc Natl AcadSci U S A,2015,29,112:12157-12162. |

| [81] | Dankbar B, Fennen M, Brunert D, et al. Myostatin is a direct regulator of osteoclast differentiation and its inhibition reduces inflammatory joint destruction in mice[J]. Nat Med, 2015, 21 : 1085–1090. DOI:10.1038/nm.3917 |

| [82] | Lin X,Hanson E,Betik AC,et al. Hindlimb immobilization,but not castration,induces reduction of undercarboxylated osteocalcin associated with muscle atrophy in rats[J]. J Bone Miner Res,2016,Epub ahead of print. |

| [83] | Karsenty G,Olson EN. Bone and muscle endocrine functions: unexpected paradigms of inter-organ communication[J]. Cell,2016,10,164:1248-1456. http://cn.bing.com/academic/profile?id=2294986745&encoded=0&v=paper_preview&mkt=zh-cn |

| [84] | Bren-Mattison Y, Hausburg M, Olwin BB. Growth of limb muscle is dependent on skeletal-derived Indian hedgehog[J]. Dev Biol, 2011, 356 : 486–495. DOI:10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.002 |

| [85] | Sato C,Iso Y,Mizukami T,et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 induces cellular senescence in human mesenchymal stem cells from skeletal muscle[J].Biochem Biophys Res Commun,2016,12,470:657-662. |

| [86] | Borsheim E, Herndon DN, Hawkins HK, et al. Pamidronate attenuates muscle loss after pediatric burn injury[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2014, 29 : 1369–1372. DOI:10.1002/jbmr.2162 |

| [87] | He H, Liu Y, Tian Q, et al. Relationship of sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2016, 27 : 473–482. DOI:10.1007/s00198-015-3241-8 |

| [88] | Lee SG, Lee Y, Kim KJ, et al. Additive association of vitamin D insufficiency and sarcopenia with low femoral bone mineral density in noninstitutionalized elderly population: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2009-2010[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2013, 24 : 2789–2799. DOI:10.1007/s00198-013-2378-6 |

| [89] | Cheng Q, Zhu X, Zhang X, et al. A cross-sectional study of loss of muscle mass corresponding to sarcopenia in healthy Chinese men and women: reference values,prevalence,and association with bone mass[J]. J Bone Miner Metab, 2014, 32 : 78–88. DOI:10.1007/s00774-013-0468-3 |

| [90] | Sjoblom S, Suuronen J, Rikkonen T, et al. Relationship between postmenopausal osteoporosis and the components of clinical sarcopenia[J]. Maturitas, 2013, 75 : 175–180. DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.03.016 |

| [91] | Hida T, Ishiguro N, Shimokata H, et al. High prevalence of sarcopenia and reduced leg muscle mass in Japanese patients immediately after a hip fracture[J]. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2013, 13 : 413–420. DOI:10.1111/ggi.2013.13.issue-2 |

| [92] | Scott D, Chandrasekara SD, Laslett LL, et al. Associations of sarcopenic obesity and dynapenic obesity with bone mineral density and incident fractures over 5-10 years in community-dwelling older adults[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2016, 99 : 30–42. DOI:10.1007/s00223-016-0123-9 |

| [93] | Lang T, Cauley JA, Tylavsky F, et al. Computed tomographic measurements of thigh muscle cross-sectional area and attenuation coefficient predict hip fracture:the health,aging,and body composition study[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2010, 25 : 513–519. DOI:10.1359/jbmr.090807 |

| [94] | Yu R, Leung J, Woo J. Incremental predictive value of sarcopenia for incident fracture in an elderly Chinese cohort: results from the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOs) Study[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2014, 15 : 551–558. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2014.02.005 |

| [95] | Janalee I, Marco B. Physiology of mechanotransduction: how do muscle and bone "talk" to one another?[J]. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab, 2014, 12 : 77–85. DOI:10.1007/s12018-013-9152-3 |

| [96] | Yu HS, Kim JJ, Kim HW, et al. Impact of mechanical stretch on the cell behaviors of bone and surrounding tissues[J]. J Tissue Eng, 2016, 13 : 2041731415618342. |

| [97] | DiGirolamo DJ, Clemens TL, Kousteni S. The skeleton as an endocrine organ[J]. Nat Rev Rheumatol, 2012, 8 : 674–683. DOI:10.1038/nrrheum.2012.157 |

| [98] | Lebrasseur NK, Achenbach SJ, Melton LJ, et al. Skeletal muscle mass is associated with bone geometry and microstructure and serum insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 levels in adult women and men[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2012, 27 : 2159–2169. DOI:10.1002/jbmr.1666 |

| [99] | Wannenes F, Papa V, Greco EA, et al. abdominal fat and sarcopenia in women significantly alter osteoblasts homeostasis in vitro by a wnt/ β -catenin dependent mechanism[J]. Int J Endocrinol, 2014, 2014 : 278316. |

| [100] | Yang SY, Hoy M, Fuller B, et al. Pretreatment with insulin-like growth factor I protects skeletal muscle cells against oxidative damage via PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 MAPK pathways[J]. Lab Invest, 2010, 90 : 391–401. DOI:10.1038/labinvest.2009.139 |

| [101] | Baumgartner RN, Koehler KM, Gallagher D, et al. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 1998, 147 : 755–763. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009520 |

| [102] | Chen LK, Liu LK, Woo J, et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2014, 15 : 95–101. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025 |

| [103] | Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People[J]. Age Ageing, 2010, 39 : 412–423. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afq034 |

| [104] | Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence,etiology,and consequences. Internationalworkinggroup on sarcopenia[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2011, 12 : 249–256. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.003 |

| [105] | Nelson ME, Fiatarone MA, Morgami CM, et al. Effects of high-intensity strength training on multiple risk factors for osteoporotic fractures. A randomized controlled trial[J]. JAMA, 1994, 272 : 1909–1914. DOI:10.1001/jama.1994.03520240037038 |

| [106] | Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ambrosius WT, et al. Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: the LIFE study randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA, 2014, 311 : 2387–2396. DOI:10.1001/jama.2014.5616 |

| [107] | Bann D,Chen H,Bonell C,et al. Life Study investigators.Socioeconomic differences in the benefits of structured physical activity compared with health education on the prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: the LIFE study[J]. J Epidemiol Commun, 2016, Epub ahead of print. |

| [108] | Tieland M, Dirks ML, van der Zwaluw N, et al. Protein supplementation increases muscle mass gain during prolonged resistancetype exercise training in frail elderly people: a randomized,double-blind,placebo-controlled trial[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2012, 13 : 713–719. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2012.05.020 |

| [109] | Cermak NM, de Groot LC, van Loon LJ. Perspective: Protein supplementation during prolonged resistance type exercise training augments skeletal muscle mass and strength gains[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2013, 14 : 71–72. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.003 |

| [110] | Zhao J, Xia WB, Nie M, et al. The levels of bone turnover markers in Chinese postmenopausal women: Peking Vertebral Fracture Study[J]. Menopause, 2012, 18 : 1237–1243. |

| [111] | Beaudart C, Buckinx F, Rabenda V, et al. The effects of vitamin D on skeletal muscle strength,muscle mass,and muscle power: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2012, 99 : 4336–4345. |

| [112] | Stout M, Tew GA, Doll H, Zwierska I, et al. Testosterone therapy during exercise rehabilitation in male patients with chronic heart failure who have low testosterone status: a double-blind randomized controlled feasibility study[J]. Am Heart J, 2012, 164 : 893–901. DOI:10.1016/j.ahj.2012.09.016 |

| [113] | Kovacheva EL, Hikim AP, Shen R, et al. Testosterone supplementation reverses sarcopenia in aging through regulation of myostatin,c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase,Notch,and Akt signaling pathways[J]. Endocrniology, 2010, 151 : 628–638. DOI:10.1210/en.2009-1177 |

| [114] | Papanicolaou DA, Ather SN, Zhu H, et al. A phase ⅡA randomized,placebocontrolled clinical trial to study the efficacy and safety of the selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM),MK-0773 in female participants with sarcopenia[J]. J Nutr Health Aging, 2013, 17 : 533–543. DOI:10.1007/s12603-013-0335-x |

| [115] | Basario S, Collins L, Dillon EL, et al. The safety,pharmacokinetics,and effects of LGD-4033,a novel nonsteroidal oral,selective androgen receptor modulator,in healthy young men[J]. J Gerontol A, 2013, 68 : 87–95. DOI:10.1093/gerona/gls078 |

| [116] | Dobs AS, Boccia RV, Croot CC, et al. Effects of enobosarm on muscle wasting and physical function in patients with cancer: a double-blind,randomized controlled phase 2 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2013, 14 : 335–345. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70055-X |

| [117] | Steiner MS. Enobosarm,a selective androgen receptor modulator,increases lean body mass in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients in two pivotal,international phase 3 trials[J]. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2013, 4 : 69. |

| [118] | 中华医学会骨质疏松和骨矿盐疾病分会. 原发性骨质疏松诊疗指南[J]. 中华骨质疏松和骨矿盐疾病杂志, 2011, 4 : 2–17. |

| [119] | Liao RX, Yu M, Jiang Y. Management of osteoporosis with calcitriol in elderly Chinese patients: a systematic review[J]. Clin Interv Aging, 2014, 9 : 515–26. |

| [120] | Ito S, Harada A, Kasai T, et al. Use of alfacalcidol in osteoporotic patients with low muscle mass might increase muscle mass: an investigation using a patient database[J]. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2014(Suppl 1) : 122–128. |

| [121] | Blackman MR, Sorkin JD, Munzer T, et al. Growth hormone and sex steroid administration in healthy aged women and men: a randomized controlled trial[J]. JAMA, 2002, 288 : 2282–2292. DOI:10.1001/jama.288.18.2282 |

| [122] | Gaskin FS, Farr SA, Banks WA, et al. Ghrelin-induced feeding is dependent on nitric oxide[J]. Peptides, 2008, 24 : 913–918. |

| [123] | Adunsky A, Chandler J, Heyden N, et al. MK-0677(ibutamoren mesylate) for the treatment of patients recovering from hip fractures: a multicenter,randomized,placebo-controlled phase Ⅱb study[J]. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2011, 53 : 183–189. DOI:10.1016/j.archger.2010.10.004 |

| [124] | Kamalakkannan G, Petrilli CM, George I, et al. Clenbuterol increases lean muscle mass but not endurance in patients with chronic heart failure[J]. J Heart Lung Transpl, 2008, 27 : 457–461. DOI:10.1016/j.healun.2008.01.013 |

| [125] | Estergaard P. Fracture risk in patients with chronic lung diseases treated with bronchodilator drugs and inhaled and oral corticosteroids[J]. Chest, 2007, 132 : 1599. DOI:10.1378/chest.07-1092 |

| [126] | Potsch MS, Tschirner A, Palus S, et al. The anabolic catabolic transforming agenda (ACTA) espindolol increases muscle mass and decreases fat mass in old rats[J]. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2014, 5 : 149–158. DOI:10.1007/13539.2190-6009 |

| [127] | Schellenbaum GD, Smith NL, Heckbert SR, et al. Weight loss,muscle strength,and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in older adults with congestive heart failure or hypertension[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2005, 53 : 1996–2000. DOI:10.1111/(ISSN)1532-5415 |

| [128] | Peters R, Beckett N, Burch L, et al. The effect of treatment based on diuretic (indapamide)±ACE inhibitor (perindopril) on fractures in the hypertension in the very elderly trial (HYVET)[J]. Age Ageing, 39 : 609–616. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afq071 |

| [129] | Wagner KR, Fleckenstein JL, Amato AA, et al. A phase Ⅰ/ Ⅱ Trial of MYO-029 in adult subjects with muscular dystrophy[J]. Ann Neurol, 2008, 63 : 561–571. DOI:10.1002/ana.v63:5 |

| [130] | Attie KM, Brogstein NG, Yang Y, et al. A single scending-dose study of muscle regulator ACE-031 in healthy volunteers[J]. Muscle Nerve, 2013, 47 : 416–423. DOI:10.1002/mus.23539 |

| [131] | Wakabayashi H, Sakuma K. Rehabilitation nutrition for sarcopenia with disability: a combination of both rehabilitation and nutrition care management[J]. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2014, 5 : 269–277. DOI:10.1007/13539.2190-6009 |

| (收稿日期:2016-08-20) |