肌肉减少症简称肌少症(sarcopenia),源于希腊语,sarx意为肌肉,penia意为减少或丢失,于1989年由Rosenberg首次命名[1]。Morley等[2]和Evans[3-5]强调与增龄相关的肌肉丢失可以导致肌肉力量、人体代谢率、供氧能力衰退,至此,人们才开始重视这一疾病,其关注度也逐年增加。但目前仍无一个公认的诊断标准,调查得到的患病率也不尽相同。肌少症的患病率随年龄增加,据统计,60~70岁的人群患病率大致为5%~13%,而超过80岁的人群患病率为11%~50%[6]。研究显示,美国由肌少症直接引起的经济损失高达185亿美金[7]。此外,肌少症可导致患者肌力和灵活性减低,易疲劳,并且增加跌倒和骨折的风险,严重减低了患者的生活质量[8]。目前,60岁以上的老年人以每年2.6%的速率增加,据推测,到21世纪50年代,老年人口将超过20亿[9]。肌少症将是人类健康和社会发展的重大威胁之一,探寻防治肌少症方法的重要性不言而喻。

目前,对肌少症的认识仍处于起步阶段,其发病机制较为复杂,包括老年人身体活动量减少、蛋白合成能力减退、肌细胞内线粒体功能下降、肌细胞内蛋白分解反应增强等原因[8]。其中最重要的病因之一是机体活动量减少[10-11]。研究者将治疗肌少症的关键锁定在增加肌量和改善机体活动能力上,并已尝试很多方法针对肌少症进行防治,包括生长激素、雌激素、雄激素、药物、营养和运动疗法,而运动疗法被视为所有疗法的基础和关键之一[12-13]。本综述旨在说明运动疗法作为肌少症治疗手段的临床和理论依据, 为治疗肌少症提供新的思路和参考。

运动疗法防治肌少症的临床研究证据由于老年人身体机能逐步退化,故不适合参与剧烈的、高强度的训练,以免增加运动损伤发生的概率。而肌少症患者不仅会出现力量下降的情况,而后还会出现功能状态、移动、灵活性、平衡能力的下降,这些可导致患肌少症的老年人在运动过程中更易出现跌倒,最终导致肌少症患者病死率的升高[14-15]。对于肌少症患者来说,主要采取的运动干预方式是抗阻训练和有氧运动。

抗阻训练抗阻运动是肌肉在克服外来阻力时进行的主动运动,并且随着运动能力的提升对运动强度需求逐步加大。它主要是通过无氧代谢供能,常见的运动方式有举重、拉伸器训练、俯卧撑、引体向上、仰卧起坐等,均能较好地改善肌肉功能[16-17]。有研究报道,即使是过往匮乏锻炼的老年人经过短时间的抗阻训练,他们的蛋白合成率和神经肌肉适应性反应能达到和年轻人相似的水平[18]。这种训练方法可通过多种途径来延缓老年人肌少症的发展:增强肌肉的量和功能,减轻平衡和灵活性衰退的问题,从而能降低肌少症相关的并发症的发生、发展[19]。

观察性和干预性研究都表明抗阻运动对老年人的肌量、肌力和活动功能都有显著提升。一项横断面调查纳入平时主要进行抗阻训练的运动员(52人)、主要进行有氧训练的运动员(23人)和非运动员的老年人(149名),应用生物电阻抗分析法检测并比较受试者的肌量和小鱼际运动单位数量,结果表明运动员的肌量和运动单位数量较普通人丰富,亚组分析表明抗阻运动对肌量的提升较有氧运动更显著[20]。一项前瞻性队列研究发现经过近2年的抗阻训练干预,老年人的握力明显提高,并且体脂减少[21]。一项随机对照试验对纳入的老年人进行了为期52周(2~3次/周,每次60 min)的抗阻训练,结果显示,全身及上肢肌量都较对照组显著增加[22]。

有氧运动有氧运动是指人体在氧气充分供应的情况下进行的体育锻炼、并以大肌群节律性、重复性运动为特征[16]。常见的有氧运动包括快走、瑜伽、游泳、打乒乓球、跳舞、骑行等。以往认为有氧运动能通过增加肌细胞内线粒体密度和肌组织毛细血管密度提高机体在运动时的氧气供给能力[23];从而提高心肺功能、减少心血管疾病发生的危险,但对肌量和肌力影响较小。随着认识的加深,发现有氧运动对肌少症的防治也存在效果。

一项横断面调查纳入74名志愿者,按照其平时的运动量分为有氧运动组和非运动组,发现运动组的握力、伸膝关节的力量较非运动组显著升高[24]。为调查有氧运动对老年绝经女性肌量减少的保护作用,另一项研究通过纳入117名老年绝经后女性进行为期12个月的有氧运动,结果显示有氧运动能有效改善绝经老年女性的肌量和骨骼肌指数(四肢肌量/身高2)[25]。

有氧-抗阻联合训练目前,不少研究者认为,有氧运动联合抗阻训练对肌少症的防治有积极意义[26-29]。一项临床随机对照实验调查了运动对长期卧床(60 d)女性下肢肌量和肌力的作用,结果表明,混合运动(有氧+抗阻运动)组女性伸膝的力量和耐力、踝关节的力量、下肢的肌量较空白对照组强[26]。一项纳入43名Ⅱ型糖尿病患者的随机对照实验,经过12周(3次/周,每次60 min)的有氧联合抗阻训练,与空白对照组相比,训练组的抗疲劳、膝关节屈伸力量和生活质量都得到改善[27]。一项为期12周(2次/周,每次约30 min)的随机对照研究表明,进行有氧联合抗阻运动训练对接受雄激素抑制剂治疗的前列腺癌患者的肌量、肌力、身体活动和平衡能力具有明显的改善作用[28]。另有研究表明,有氧训练和抗阻运动同步进行比单独进行其中一种训练对肌少症的防治更为有效[16, 29]。

运动训练结合营养补充疗法适当的营养补充,尤其是增加蛋白的摄入联合运动训练在肌少症的防治中起着不可忽视的作用。一项随机对照实验通过对比老年人进行抗阻训练时普通饮食和高乳蛋白补充的饮食(12周,3次/周,>1.2 g蛋白/kg·d,约27 g乳蛋白/d)对肌少症的影响,结果表明,实验组的肌量、身体功能状态以及肌力都较对照组有显著改善,而且伴随机体脂肪含量减少;受试者对乳制品的蛋白吸收率较豆制品的高,且对老年人的肌力改善的效果较好[30]。随后一项随机对照实验表明抗阻运动联合蛋白补充疗法(4个月,3次/周,约19 g蛋白/d)对肌少症患者的肌量和肌力均有明显的改善,但与摄取的蛋白种类(乳制品、豆制品)无关[31]。然而,不同身体情况对蛋白补充疗法和抗阻训练的敏感性可能不同。一项以患严重全身炎性反应综合征的老年人为研究对象的单盲随机对照试验,对比抗阻训练联合蛋白补充疗法(12周,3次/周,约18.8 g蛋白/d)和常规护理对老年人的影响,结果显示,干预组的体质量、肌量和握力较对照组并无增加,而且,对照组的身体机能甚至好于干预组[32]。

推荐的运动疗法方案尽管目前大部分临床研究证明,运动干预肌少症是有效的,但目前对防治肌少症所需运动的具体强度和时长尚无定论,笔者通过综合一些观点提出以下方案[33-38]。首先应对老年人的基础健康状况进行评估,将其分为以下3种情况:(1)日常活动正常且不伴有心血管疾病(包括心脏、外周血管、心脑血管方面的疾病)、代谢性疾病(比如Ⅰ型或Ⅱ型糖尿病)或肾脏疾病的老年人,推荐他们正常进行日常活动和运动训练;(2)伴有上述的一种或多种疾病,但经医师评估允许其参与运动,且在过去12个月内活动情况良好的老年人,推荐他们进行中等强度的训练;(3)若患有上述疾病且在活动时出现症状,建议先停止训练,并在纠正健康状态后,再行评估。

不同性别及年龄其适宜的运动强度不尽相同,通过应用Borg量表进行自我评估(6~20级),从而决定训练强度。一般情况下,推荐进行的有氧运动是强度适中的健步走训练(Borg量表自我评估的11~15级),抗阻运动需运用哑铃[39]。方案中健步走的前5 min作为热身速度稍慢,哑铃训练做两组,组间间隔1 min。前4周作为适应期,每周进行两次训练(隔3天1次),健步走30 min,各个大肌群的哑铃辅助训练, 重量以15~20的最大重复次数(repetition maximum,RM)为宜;4~8周,每周进行3次训练(隔天1次),运动强度不变;8~12周,健步走时间提升至40 min,哑铃重量调整至12~15 RM;12周以后,健步走时间大致为50~60 min,哑铃训练调整至8~10 RM。此外,老年人参与运动训练的自主性和依从性较差,在无人监督的情况下并不能规范且完整地完成训练,因此在训练的时候应该相应地进行监督,以保证能完成训练任务和目的并保证安全性[40]。

治疗肌少症应该尽早开始,保持处于正氮平衡的状态[12]。研究表明,肌肉量在儿童及青春期逐渐增加,在20~30岁的时候就会以1%的速度逐年降低,30~50岁的时候肌量和肌力都会进一步衰减,而在50岁以后下降速度加快[13]。此外,肌肉横截面积在60岁以后每年下降1%~2%[41]。因此,最好的预防老年人肌少症的发生、发展的方法可能是在年轻时就通过规范的运动训练增加肌量和肌力。

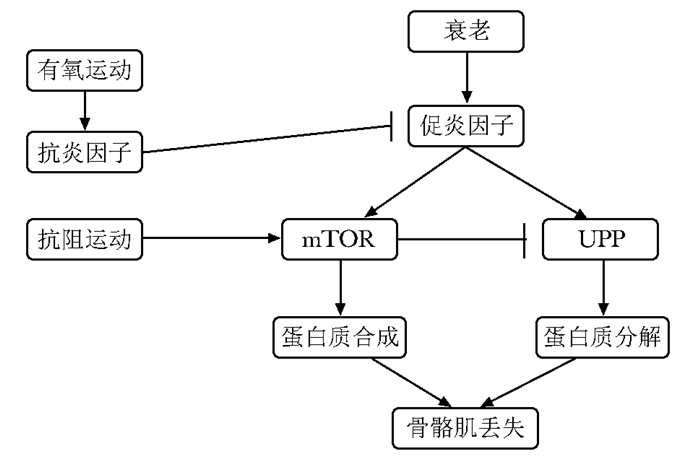

运动疗法防治肌少症的潜在机制运动对骨骼肌保护效应的分子机制和信号通路尚不完全明确,但总体上,都使得肌肉蛋白的合成或肌纤维蛋白的合成量多于其分解量。运动对肌肉健康的促进机制是复杂的(表 1)。肌卫星细胞的募集和激活是其中重要的机制之一,研究表明,运动能导致肌肉超微结构的损伤,引起炎性反应因子和生长因子(包括胰岛素样生长因子-1,成纤维细胞生长因子,力生长因子等)的释放,进而促进卫星细胞的增生分化[42-43]。此外,规律的体育锻炼被证明能减轻体内的炎性反应因子水平,而老年人体内炎性反应因子水平的提高被认为是肌少症的发病机制之一(图 1)[44]。衰老和mTORC1信号通路相关,而mTORC1信号通路对负责控制肌纤维蛋白合成的mRNA翻译的起始发挥重要作用。研究表明,肌肉本身收缩可直接通过磷脂酸或间接通过ERK1/2激活mTORC1信号通路;一旦此通路被激活,它会激活下游的两个靶点4E-BP1和S6K1,继而介导mRNA翻译的启动和延长,最终合成肌肉蛋白[45](图 1)。泛素蛋白酶体系统是肌肉蛋白降解最主要的途径,从而产生肌肉萎缩。磷酸化的叉头框蛋白(FOXO)能阻碍泛素蛋白酶体途径不被活化, 而运动能通过IGF-1/PI3K/Akt通路阻碍FOXO的活化,从而防止肌肉蛋白降解[44, 46](图 1)。随着年龄增加,各组肌肉间及肌束间脂肪细胞增加,由于脂肪细胞释放细胞因子,导致肌肉损伤,脂肪细胞越多,肌肉力量下降越明显[47-48]。而运动能减少体脂含量包括肌间的脂肪,因此这将有助于改善肌肉的功能[49-50]。

| 肌少症发病机制 | 运动效应 |

| 运动单位减少 | 增加运动单位 |

| 慢性炎性反应 | 下调炎性反应因子(主要是白介素-6、肿瘤坏死因子-α、C反应蛋白)的表达 |

| 氧化压增加 | 调节氧化压 |

| 卫星细胞减少 | 增加卫星细胞的修复和补充 |

| 脂肪浸润(肌纤维内部或肌纤维间隙) | 减少脂肪的浸润 |

| 减少的mTOR | 增加mTOR |

| 胰岛素抵抗 | 防止胰岛素抵抗的出现 |

| DNA损伤增多/凋亡 | 减少DNA损伤 |

| 减少线粒体间隔 | 线粒体间隔增多 |

|

| 图 1 有氧和抗阻运动对肌少症的对抗作用 Figure 1 Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise training on sarcopenia |

此外,骨骼肌作为一个重要的内分泌器官,其在收缩时能释放许多肌肉因子,这些因子可能对人类健康有重要的作用[51]。而且,运动过程中细胞因子的产生也受运动方式、强度、持续时长等因素的影响。IL-6可由肌肉在进行剧烈运动时产生,肌肉收缩从而释放的IL-6触发了抗炎的级联反应,即通过促进减少抗炎因子IL-10、IL-1受体拮抗剂的生成,从而抑制了促炎性因子IL-1β和TNF-α的产生[51]。而且IL-6在骨骼肌肥厚的过程中起重要作用[52]。另一个IL-6超家族成员白血病抑制因子(leukemia inhibitory factor,LIF)不仅对骨骼肌的肥厚有影响,而且可促进肌肉损伤后的再生[53]。运动后,肌肉分泌LIF增多,有氧运动可使其mRNA表达水平升高4.5倍,而在抗阻训练时增加更为明显,达到了基础表达量的9倍[53-54]。IL-7也可由肌肉分泌,其血清水平在抗阻训练后升高[55]。有研究表明IL-7在肌肉干细胞的迁移过程中起重要作用,从而对肌细胞的再生进行调控[56]。肌生成抑制蛋白(myostatin)是转化生长因子-β超家族的成员之一,对肌肉的生长具有负性调控作用,其在中等强度的有氧运动及剧烈的抗阻运动后分泌量减少[57]。据报道,肌生成抑制蛋白对肌肉的作用可被核心蛋白聚糖(decorin)和卵泡抑素(follistatin)所抑制,而这两种物质都可由肌肉分泌[57-59]。几丁质酶-3-样蛋白1(chitinase-3-like protein 1,CHI3L1)作为近期新发现的肌肉因子,由促炎因子(如TNF-α和IL-6)刺激而产生,它可通过抑制NKkB的激活从而阻断由TNF-α引起的胰岛素抵抗和炎性反应反应,最终起到保护肌小管的作用[60]。研究表明,高强度的耐力和力量训练能增加循环CHI3L1的水平,而CHI3L1/PAR-2通路可对肌肉的生长和修复起作用[61]。

目前,对于原发性老年肌少症的形成机制仍在探寻,且无标准有效的防治方案。运动疗法作为目前认可较高的防治手段,应该进一步优化治疗方案,继续探索其他运动训练方式是否对肌少症有保护作用,并针对不同健康状况、性别以及年龄等情况明确运动参数并提出个体化方案。尽管原发性肌少症机制和防治研究取得了一定进展,但是仍然需要进一步的研究以阐明多因子和多信号通路的交互作用以及是否存在其他发病机制。此外,基因水平的分析也有待进一步展开。

| [1] | Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia:origins and clinical relevance[J]. J Nutr, 1997, 127: 990–991. |

| [2] | Morley JE, Anker SD, von Haehling S. Prevalence, incidence, and clinical impact of sarcopenia:facts, numbers, and epidemiology-update 2014[J]. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2014, 5: 253–259. DOI:10.1007/13539.2190-6009 |

| [3] | Evans WJ, Campbell WW. Sarcopenia and age-related changes in body composition and functional capacity[J]. J Nutr, 1993, 123: 465–468. |

| [4] | Evans WJ. What is sarcopenia?[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 1995, 50: 5–8. |

| [5] | Evans WJ. Skeletal muscle loss:cachexia, sarcopenia, and inactivity[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2010, 91: 1123s–1127s. DOI:10.3945/ajcn.2010.28608A |

| [6] | von Haehling S, Morley JE, Anker SD. An overview of sarcopenia:facts and numbers on prevalence and clinical impact[J]. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2010, 1: 129–133. DOI:10.1007/13539.2190-6009 |

| [7] | Peterson SJ, Braunschweig CA. Prevalence of sarco-penia and associated outcomes in the clinical setting[J]. Nutr Clin Pract, 2016, 31: 40–48. DOI:10.1177/0884533615622537 |

| [8] | Tarantino U, Piccirilli E, Fantini M, et al. Sarcopenia and fragility fractures:molecular and clinical evidence of the bone-muscle interaction[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2015, 97: 429–437. DOI:10.2106/JBJS.N.00648 |

| [9] | Nikolich-Zugich J. The aging immune system:challenges for the 21st century[J]. Semin Immunol, 2012, 24: 301–302. DOI:10.1016/j.smim.2012.09.001 |

| [10] | Montero-Fernandez N, Serra-Rexach JA. Role of exercise on sarcopenia in the elderly[J]. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med, 2013, 49: 131–143. |

| [11] | Daly RM, O'Connell SL, Mundell NL, et al. Protein-enriched diet, with the use of lean red meat, combined with progressive resistance training enhances lean tissue mass and muscle strength and reduces circulating IL-6 concentrations in elderly women:a cluster randomized controlled trial[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2014, 99: 899–910. DOI:10.3945/ajcn.113.064154 |

| [12] | Kim H, Suzuki T, Saito K, et al. Effects of exercise and tea catechins on muscle mass, strength and walking ability in community-dwelling elderly Japanese sarcopenic women:A randomized controlled trial[J]. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2013, 13: 458–465. DOI:10.1111/ggi.2013.13.issue-2 |

| [13] | Naseeb MA, Volpe SL. Protein and exercise in the prevention of sarcopenia and aging[J]. Nut Res, 2017, 40: 1–20. DOI:10.1016/j.nutres.2017.01.001 |

| [14] | Woo N, Kim SH. Sarcopenia influences fall-related injuries in community-dwelling older adults[J]. Geriatr Nurs, 2014, 35: 279–282. DOI:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2014.03.001 |

| [15] | Waters DL, Hale L, Grant AM, et al. Osteoporosis and gait and balance disturbances in older sarcopenic obese New Zealanders[J]. Osteoporos Int, 2010, 21: 351–357. DOI:10.1007/s00198-009-0947-5 |

| [16] | Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Fiatarone Singhb MA, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2009, 41: 1510–1530. DOI:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a0c95c |

| [17] | Zampieri S, Pietrangelo L, Loefler S, et al. Lifelong physical exercise delays age-associated skeletal muscle decline[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2015, 70: 163–173. DOI:10.1093/gerona/glu006 |

| [18] | Newton RU, Hakkinen K, Hakkinen A, et al. Mixed-methods resistance training increases power and strength of young and older men[J]. Med Sci Sports Exer, 2002, 34: 1367. DOI:10.1097/00005768-200208000-00020 |

| [19] | Orr R, Raymond J, Fiatarone SM. Efficacy of progressive resistance training on balance performance in older adults:a systematic review of randomized controlled trials[J]. Sports Med, 2008, 38: 317–343. DOI:10.2165/00007256-200838040-00004 |

| [20] | Drey M, Sieber CC, Degens H, et al. Relation between muscle mass, motor units and type of training in master athletes[J]. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging, 2016, 36: 70–76. DOI:10.1111/cpf.12195 |

| [21] | Hassan BH, Hewitt J, Keogh JW, et al. Impact of resistance training on sarcopenia in nursing care facilities:A pilot study[J]. Geriatr Nurs, 2016, 37: 116–121. DOI:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.11.001 |

| [22] | Andersen TR, Schmidt JF, Pedersen MT, et al. The Effects of 52 weeks of soccer or resistance training on body composition and muscle function in +65-year-old healthy males-A Randomized Controlled Trial[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11: e0148236. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0148236 |

| [23] | Marzetti E, Lawler JM, Hiona A, et al. Modulation of age-induced apoptotic signaling and cellular remodeling by exercise and calorie restriction in skeletal muscle[J]. Free Radical Biol Med, 2008, 44: 160–168. DOI:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.028 |

| [24] | Crane JD, Macneil LG, Tarnopolsky MA. Long-term aerobic exercise is associated with greater muscle strength throughout the life span[J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2013, 68: 631–638. DOI:10.1093/gerona/gls237 |

| [25] | Mason C, Xiao L, Imayama I, et al. Influence of diet, exercise, and serum vitamin d on sarcopenia in postmenopausal women[J]. Med Sci Sports Exercise, 2013, 45: 607. DOI:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31827aa3fa |

| [26] | Lee SM, Schneider SM, Feiveson AH, et al. WISE-2005:Countermeasures to prevent muscle decond-itioning during bed rest in women[J]. J Appl Physiol, 2014, 116: 654. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00590.2013 |

| [27] | Tomas-Carus P, Ortega-Alonso A, Pietilainen KH, et al. A randomized controlled trial on the effects of combined aerobic-resistance exercise on muscle strength and fatigue, glycemic control and health-related quality of life of type 2 diabetes patients[J]. J Sports Med Phys Fitness, 2016, 56: 572–578. |

| [28] | Galvao DA, Drspry T. Combined resistance and aerobic exercise program reverses muscle loss in men undergoing androgen suppression therapy for prostate cancer without bone metastases:a randomized controlled trial[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2010, 28: 340. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2488 |

| [29] | Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Singh MAF, et al. American College of Sport Medicine Position Stand.Exercise and physical activity for older adults[J]. Med Sci Sports Exer, 2009, 41: 1510–1530. DOI:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a0c95c |

| [30] | Thomson RL, Brinkworth GD, Noakes M, et al. Muscle strength gains during resistance exercise training are attenuated with soy compared with dairy or usual protein intake in older adults:A randomized controlled trial[J]. Clin Nutr, 2016, 35: 27–33. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2015.01.018 |

| [31] | Maltais ML, Ladouceur JP, Dionne IJ. The effect of resistance training and different sources of postexercise protein supplementation on muscle mass and physical capacity in sarcopenic elderly men[J]. J Strength Cond Res, 2016, 30: 1680–1687. DOI:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001255 |

| [32] | Buhl SF, Andersen AL, Andersen JR, et al. The effect of protein intake and resistance training on muscle mass in acutely ill old medical patients-A randomized controlled trial[J]. Clin Nutr, 2016, 35: 59–66. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2015.02.015 |

| [33] | Miyazaki R, Takeshima T, Kotani K. Exercise intervention for anti-sarcopenia in community-dwelling older people[J]. J Clin Med Res, 2016, 8: 848–853. DOI:10.14740/jocmr2767w |

| [34] | Riebe D, Franklin BA, Thompson PD, et al. Updating ACSM's recommendations for exercise preparticipation health screening[J]. Med Sci Sports Exer, 2015, 47: 2473. DOI:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000664 |

| [35] | Marzetti E, Calvani R, Tosato M, et al. Physical activity and exercise as countermeasures to physical frailty and sarcopenia[J]. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2017, 29: 1–8. |

| [36] | Peterson MD, Sen A, Gordon PM. Influence of resistance exercise on lean body mass in aging adults:a Meta-analysis[J]. Med Sci Sports Exer, 2011, 43: 249. |

| [37] | Anonymous. Physical activity and public health in older adults:recommendation from the american College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association(ACSM/AHA)[J]. Geriatr Nurs, 2007, 28: 339–340. DOI:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.10.002 |

| [38] | Morley JE, Argiles JM, Evans WJ, et al. Nutritional recommendations for the management of sarcopenia[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2010, 11: 391. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2010.04.014 |

| [39] | Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion[J]. Med Sci Sports Exer, 1982, 14: 377–381. |

| [40] | Lacroix A, Kressig RW, Muehlbauer T, et al. Effects of a supervised versus an unsupervised combined balance and strength training program on balance and muscle power in healthy older adults:A Randomized Controlled Trial[J]. Gerontology, 2016, 62: 275–288. DOI:10.1159/000442087 |

| [41] | Russ DW, Kimberly GC, Conaway MJ, et al. Evolving concepts on the age-related changes in "muscle quality"[J]. J Cachexia Sarcopeni, 2012, 3: 95–109. DOI:10.1007/13539.2190-6009 |

| [42] | Thornell LE. Sarcopenic obesity:satellite cells in the aging muscle[J]. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 2011, 14: 22–27. DOI:10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283412260 |

| [43] | Kang JS, Krauss RS. Muscle stem cells in developmental and regenerative myogenesis[J]. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 2010, 13: 243–248. DOI:10.1097/MCO.0b013e328336ea98 |

| [44] | Xia Z, Cholewa J, Zhao Y, et al. Targeting inflammation and downstream protein metabolism in sarcopenia:a brief up-dated description of concurrent exercise and leucine-based multimodal intervention[J]. Front Physiol, 2017, 8: 434. DOI:10.3389/fphys.2017.00434 |

| [45] | Makanae Y, Fujita S. Role of exercise and nutrition in the prevention of sarcopenia[J]. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo), 2015, 61: 125–127. DOI:10.3177/jnsv.61.S125 |

| [46] | Karin M. Role for IKK2 in muscle:waste not, want not[J]. J Clin Invest, 2006, 116: 2866–2868. DOI:10.1172/JCI30268 |

| [47] | Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE, Thaete FL, et al. Skeletal muscle attenuation determined by computed tomography is associated with skeletal muscle lipid content[J]. J Appl Physiol, 2000, 89: 104. DOI:10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.104 |

| [48] | Christie A, Kamen G. Short-term training adaptations in maximal motor unit firing rates and afterhyperpolarization duration[J]. Muscle Nerve, 2010, 41: 651–660. |

| [49] | Short KR, Vittone JL, Bigelow ML, et al. Age and aerobic exercise training effects on whole body and muscle protein metabolism[J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2004, 286: E92. DOI:10.1152/ajpendo.00366.2003 |

| [50] | Misic MM, Rosengren KS, Woods JA, et al. Muscle quality, aerobic fitness and fat mass predict lower-extremity physical function in community-dwelling older adults[J]. Gerontology, 2007, 53: 260–266. DOI:10.1159/000101826 |

| [51] | Eckardt K, Gorgens SW, Raschke S, et al. Myokines in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetologia, 2014, 57: 1087–1099. DOI:10.1007/s00125-014-3224-x |

| [52] | Serrano AL, Baezaraja B, Perdiguero E, et al. Interleukin-6 is an essential regulator of satellite cell-mediated skeletal muscle hypertrophy[J]. Cell Metab, 2008, 7: 33–44. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.011 |

| [53] | Broholm C, Laye MJ, Brandt C, et al. LIF is a contraction-induced myokine stimulating human myocyte proliferation[J]. J Appl Physiol, 2011, 111: 251–259. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.01399.2010 |

| [54] | Broholm C, Mortensen OH, Nielsen S, et al. Exercise induces expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor in human skeletal muscle[J]. J Physiol, 2008, 586: 2195. DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.2007.149781 |

| [55] | Kraemer WJ, Hatfield DL, Comstock BA, et al. Influence of HMB supplementation and resistance training on cytokine responses to resistance exercise[J]. J Am College Nutr, 2014, 33: 247–255. DOI:10.1080/07315724.2014.911669 |

| [56] | Haugen F, Norheim F, Lian H, et al. IL-7 is expressed and secreted by human skeletal muscle cells[J]. AJP Cell Physiology, 2010, 298: C807. DOI:10.1152/ajpcell.00094.2009 |

| [57] | Görgens SW, Eckardt K, Jensen J, et al. Exercise and regulation of adipokine and myokine production[J]. Prog Mol Biol Translat Sci, 2015, 135: 313–336. DOI:10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.07.002 |

| [58] | Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscles, exercise and obesity:skeletal muscle as a secretory organ[J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 2012, 8: 457–465. DOI:10.1038/nrendo.2012.49 |

| [59] | Kanzleiter T, Rath M, Gorgens SW, et al. The myokine decorin is regulated by contraction and involved in muscle hypertrophy[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2014, 450: 1089–1094. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.123 |

| [60] | Görgens SW, Eckardt K, Elsen M, et al. Chitinase-3-like protein 1 protects skeletal muscle from TNFα-induced inflammation and insulin resistance[J]. Biochem J, 2014, 459: 479. DOI:10.1042/BJ20131151 |

| [61] | Görgens SW, Hjorth M, Eckardt K, et al. The exercise-regulated myokine chitinase-3-like protein 1 stimulates human myocyte proliferation[J]. Acta Physiol (Oxf), 2016, 216: 330–345. DOI:10.1111/apha.12579 |

| (收稿日期:2017-05-18) |