扩展功能

文章信息

- 韩琳琳, 郭斌, 贾延劼

- 外泌体在阿尔茨海默病发病机制中的研究进展

- 国际神经病学神经外科学杂志, 2017, 44(3): 336-339

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2017-01-20

修回日期: 2017-04-05

阿尔茨海默病(Alzheimer disease, AD)是一种晚期起病,由于神经变性所致的进行性记忆力丧失和认知功能障碍的神经疾病。AD的发病机制至今还有争议,但是近年来外泌体在AD发病中的作用受到越来越多关注。

外泌体(exosomes)是一类直径约40~100 nm的胞外囊泡,由多泡体(multi-vesicle bodys, MVBs)与质膜融合后产生并释放到细胞外空间[1]。外泌体是细胞间通讯的重要载体,含有miRNA和mRNA,其可以被靶细胞翻译成蛋白质[2]。外泌体涉及各种细胞功能,从细胞骨架的改变和钙调节(通过Wnt信号转导)到髓鞘形成、神经元通信和免疫调节[3]。已经证实,脑内神经干细胞、神经元、胶质细胞和内皮细胞等几乎所有的脑细胞均可释放外泌体[4]。由于外泌体形态小,易透过血脑屏障[5],并随液体流至全身而不易被吞噬细胞吞噬,因此不同来源的外泌体可在血液、脑脊液等体液中检出。外泌体与AD的发生和发展密切相关,参与AD中的多种病理过程。

1 β-淀粉样蛋白外泌体参与β-淀粉样蛋白(Aβ)的生成、胞外分泌、聚集、被细胞摄取降解等多个过程,既有神经保护作用又有神经毒性。

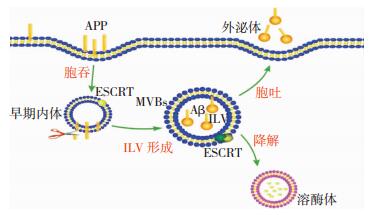

1.1 外泌体与胞内Aβ代谢Aβ多肽来自于淀粉样前体蛋白(amyloid precursor protein, APP)的水解,而APP的转运和加工与内体囊泡循环的调节密切相关。同时,内体的调节通路在外泌体的形成中也至关重要。早期内体到MVEs的成熟过程中生成装载有APP的腔内囊泡(intraluminal vesicles, ILVs),一旦与早期内体的酸性pH环境接触,ILVs就变成有利于将APP剪切形成Aβ的平台并且促进Aβ在MVEs中的积累[6]。当ILVs与质膜融合,Aβ多肽就以外泌体的形式被释放至胞外[7]。另一方面,MVEs可以通过与溶酶体融合来降解Aβ内容物而降低胞内Aβ水平[6]。由此可见,内体-溶酶体系统(endosomal/lysosomal system)可能处于Aβ生成和降解的交叉点上(图 1)。有趣的是,包含Aβ的自噬小体可以和MVBs融合而控制Aβ随外泌体释放进入细胞外空间[8],自噬也可以通过将具有潜在毒性Aβ聚集物传递到溶酶体来阻止其在神经元内的积累[9]。然而,积累的Aβ会损害MVEs功能[10],并诱导潜在毒性低聚物的形成[11],在各种AD相关小鼠模型中溶酶体降解的缺陷使Aβ代谢失衡[12]。类似的,自噬缺陷的APP小鼠影响Aβ向胞外分泌而细胞内Aβ累积增多从而导致神经变性及认知功能受损[13]。综上所述,内体-溶酶体系统及自噬功能失调可能是导致AD早期病理改变的原因[14]。

|

| 图 1 外泌体与胞内Aβ代谢。 注:质膜上的APP内吞入早期内体后在多泡体(MVBs)中包裹到腔内囊泡(ILV),在此生成Aβ。多个分子参与ILVs生成,如内体转运复合物ESCRT(endosomal sorting complexes required for transport)转运机制和脂质。MVBs有两个命运:MVBs和溶酶体融合降解其内Aβ,或者MVBs与质膜融合,导致载有Aβ的ILVs以外泌体的形式释放到胞外。 |

Aβ可以被包封到外泌体中释放到细胞外,避免其在胞内淤滞、调节胞内升高的Aβ水平,从而发挥神经保护作用[15]。但另一方面,外泌体将介导淀粉样蛋白像朊病毒样在细胞间传播[16],把其内容物传递给邻近细胞和远处的细胞。外泌体可以通过涉及硫酸肝素蛋白聚糖(HSPG)、凝集素、免疫球蛋白和四跨膜蛋白的多个途径被受体细胞摄取[17],胞外Aβ将在不同受体细胞中通过类似的途径被降解(如前所述),特别是在脂蛋白相关受体细胞(LRP1)[18]、神经元、神经母细胞瘤[11]、星形胶质细胞[18]和小胶质细胞中[19]。因此,与外泌体的相互作用可以作为淀粉样蛋白的捕获机制,促进Aβ的摄取及溶酶体对Aβ的降解[20]。经过外泌体摄取入胞的Aβ启动了引起受体细胞内内体-溶酶体系统及自噬功能失调的反应链,造成胞内细胞毒性寡聚物生成增加,淀粉样蛋白的胞外释放增加,以及一个形成淀粉样斑块的新循环[6]。这些机制可以解释淀粉样物质如何像朊病毒样在AD中扩散。

1.3 外泌体与Aβ聚集外泌体可以和Aβ螯合(sequester Aβ)[21, 22]促进其聚集。外泌体中存在的神经节苷脂1(GM1)[23]、神经酰胺(sphingolipid ceramide)[22]和PrPC[24]与此过程相关。这种结合甚至在外泌体分泌之前便促使与ILVs原位结合的Aβ单体装配成寡聚体[11]。在胞外,外泌体促进斑块的形成,尸检AD患者脑内淀粉样斑块中鉴定出外泌体相关蛋白Alix和flotillins[7, 25]。外泌体对淀粉样纤维形成的促进作用受到其他研究的挑战,有研究显示来自神经元和CSF的外泌体可抑制淀粉样斑块的形成[21, 26],并减轻Aβ对突触可塑性的破坏[24],从而发挥保护作用。这种矛盾性作用可能是因为研究中所用的试验试剂不同及外泌体的性质不同,也可能是由外泌体在Aβ聚集和Aβ清除中的双重作用产生。

1.4 外泌体与胞外Aβ清除外泌体可通过酶等内容物直接降解Aβ。来自BV-2小胶质细胞的外泌体被报道可通过外泌体相关的胰岛素降解酶(IDE)增强胞外Aβ的降解[27]。脂肪组织来源的间充质干细胞(mesenchymal stem cells, MSCs)产生降解Aβ的脑啡肽酶的外泌体, 降低细胞内外Aβ水平[28]。另有数据表明,外泌体表面蛋白如PrPC蛋白可以阻断Aβ介导的突触功能失调[29]。

此外,外泌体还可以作为淀粉样蛋白的捕获机制,促进Aβ被细胞尤其是小胶质细胞摄取进而引起溶酶体对Aβ的降解[20]。研究发现神经元衍生的外泌体促进Aβ快速转变为无毒性的淀粉样纤维而后被小胶质细胞内化降解[20]。值得注意的是,当降解途径饱和时,作为对Aβ过度吞噬作用的应答,斑块周围的小胶质细胞可能产生过多的神经毒性外泌体。体外试验中小胶质细胞释放的外泌体促进胞外聚集体形成可溶性Aβ物质,从而造成神经元损伤[30]。这些发现支持反应性小胶质细胞释放有害外泌体的假说,其将损害传播到周围少突神经胶质细胞和神经元。然而,仍然不清楚小胶质细胞外泌体的分泌增加是疾病病因还是对疾病的反应。除了外泌体内容物和溶酶体降解,另一个对淀粉样蛋白类物质的防御机制是通过血脑屏障(blood brain barrier, BBB)将其从大脑清除[31]。已经有研究表明含有Aβ聚集体的外泌体可以穿过BBB[31],但是外泌体在通过BBB清除Aβ中的作用机制尚未被阐明。

2 tau与AD中淀粉样斑块的形成不同,由高度磷酸化的变异tau蛋白(p-tau)组成的神经原纤维缠结(neurofibrillary tangles, NFTs)与AD进行性认知功能下降及神经元丢失相关。并且,AD中tau蛋白与Aβ呈现出协同作用——Aβ可促进NFTs[32],tau蛋白增加Aβ对突触的毒性[32]。目前研究已经清楚表明,外泌体与tau病理过程有关。

2.1 tau蛋白的胞外转运tau蛋白的分泌和传播机制较Aβ关注少,这可能是因为一开始的假说认为tau是神经元死亡后释放到胞外的。用tau过表达的细胞株的体外研究证实tau可被外泌体介导和被动分泌[33]。现在发现早期AD患者脑脊液、血浆中外泌体介导的p-tau水平升高,并且有种植活性[34, 35]。然而,Polanco等证明这种分泌及种植是阈值相关的——只有胞内tau聚集时才会以外泌体形式分泌至胞外,聚集体及寡聚体形式的tau才有种植活性[36]。

2.2 外泌体与tau蛋白传播在海马及颞叶中首先发现了Aβ淀粉斑块沉积后的tau蛋白传播,随后向各脑区传播,病人出现认知功能的丧失[16]。已经证实小胶质细胞可以通过外泌体来促进tau蛋白向神经元的传播及tau在脑内各区域的扩散[37]。Asai等[38]使用nSMase2抑制剂抑制外泌体的生成可限制tau病理改变在脑内的传播。作者指出,小胶质细胞可以吞噬胞内含有tau的神经元,随后通过外泌体释放出tau来传播病理改变,然而,神经元内释放的外泌体tau也可以在经外泌体扩散前就被小胶质细胞内化。

3 总结外泌体可以介导细胞间物质运输及信号传递因而在AD发病的多种病理过程中发挥作用。大量研究已经证明外泌体像“特洛伊木马”一样促进AD相关蛋白在脑内的累积和传播[39]。

总体而言,AD患者较正常人外泌体有所改变,AD中不同来源的外泌体因其含物质不同发挥的作用也不尽相同。研究外泌体让我们用全新的视角探究AD的发病机制,同时脑脊液中外泌体的水平增加及可溶性蛋白的改变可能成为诊断AD的潜在性生物标志物和治疗靶标。

| [1] |

Booth AM, Fang Y, Fallon JK, et al. Exosomes and HIV Gag bud from endosome-like domains of the T cell plasma membrane[J]. J Cell Biol, 2006, 172(6): 923-935. DOI:10.1083/jcb.200508014 |

| [2] |

Coleman BM, Hill AF. Extracellular vesicles——Their role in the packaging and spread of misfielded proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases[J]. Semin Cell Dev Biol, 2015, 40: 89-96. DOI:10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.02.007 |

| [3] |

Harding CV, Heuser JE, Stahl PD. Exosomes:looking back three decades and into the future[J]. J Cell Biol, 2013, 200(4): 367-371. DOI:10.1083/jcb.201212113 |

| [4] |

Wang S, Cesca F, Loers G, et al. Synapsin I is an oligomannose-carrying glycoprotein, acts as an oligomannose-binding lectin, and promotes neurite outgrowth and neuronal survival when released via glia-derived exosomes[J]. J Neurosci, 2011, 31(20): 7275-7290. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6476-10.2011 |

| [5] |

Squadrito ML, Baer C, Burdet F, et al. Endogenous RNAs modulate microRNA sorting to exosomes and transfer to acceptor cells[J]. Cell Rep, 2014, 8(5): 1432-1446. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.035 |

| [6] |

van Niel G. Study of Exosomes Shed New Light on Physiology of Amyloidogenesis[J]. Cell Mol Neurobiol, 2016, 36(3): 327-342. DOI:10.1007/s10571-016-0357-0 |

| [7] |

Rajendran L, Honsho M, Zahn TR, et al. Alzheimer's disease beta-amyloid peptides are released in association with exosomes[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2006, 103(30): 11172-11177. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0603838103 |

| [8] |

Nilsson P, Sekiguchi M, Akagi T, et al. Autophagy-related protein 7 deficiency in amyloid β (Aβ) precursor protein transgenic mice decreases Aβ in the multivesicular bodies and induces Aβ accumulation in the Golgi[J]. Am J Pathol, 2015, 185(2): 305-313. DOI:10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.10.011 |

| [9] |

Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy:renovation of cells and tissues[J]. Cell, 2011, 147(4): 728-741. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026 |

| [10] |

Almeida CG, Takahashi RH, Gouras GK. Beta-amyloid accumulation impairs multivesicular body sorting by inhibiting the ubiquitin-proteasome system[J]. J Neurosci, 2006, 26(16): 4277-4288. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5078-05.2006 |

| [11] |

Hu X, Crick SL, Bu G, et al. Amyloid seeds formed by cellular uptake, concentration, and aggregation of the amyloid-beta peptide[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009, 106(48): 20324-20329. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0911281106 |

| [12] |

Gowrishankar S, Yuan P, Wu Y, et al. Massive accumulation of luminal protease-deficient axonal lysosomes at Alzheimer's disease amyloid plaques[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2015, 112(28): E3699-E3708. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1510329112 |

| [13] |

Nilsson P, Loganathan K, Sekiguchi M, et al. Aβ secretion and plaque formation depend on autophagy[J]. Cell Rep, 2013, 5(1): 61-69. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.042 |

| [14] |

Peric A, Annaert W. Early etiology of Alzheimer's disease:tipping the balance toward autophagy or endosomal dysfunction[J]. Acta Neuropathol, 2015, 129(3): 363-381. DOI:10.1007/s00401-014-1379-7 |

| [15] |

Alvarez-Erviti L, Seow Y, Schapira AH, et al. Lysosomal dysfunction increases exosome-mediated alpha-synuclein release and transmission[J]. Neurobiol Dis, 2011, 42(3): 360-367. DOI:10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.029 |

| [16] |

Vingtdeux V, Sergeant N, Buée L. Potential contribution of exosomes to the prion-like propagation of lesions in Alzheimer's disease[J]. Front Physiol, 2012, 3: 229. |

| [17] |

Mulcahy LA, Pink RC, Carter DR. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake[J]. J Extracell Vesicles, 2014, 3: 24641. DOI:10.3402/jev.v3.24641 |

| [18] |

Xiao Q, Yan P, Ma X, et al. Enhancing astrocytic lysosome biogenesis facilitates Aβ clearance and attenuates amyloid plaque pathogenesis[J]. J Neurosci, 2014, 34(29): 9607-9620. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3788-13.2014 |

| [19] |

Doens D, Fernández PL. Microglia receptors and their implications in the response to amyloid β for Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis[J]. J Neuroinflammation, 2014, 11: 48. DOI:10.1186/1742-2094-11-48 |

| [20] |

Yuyama K, Sun H, Mitsutake S, et al. Sphingolipid-modulated exosome secretion promotes clearance of amyloid-β by microglia[J]. J Biol Chem, 2012, 287(14): 10977-10989. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M111.324616 |

| [21] |

Yuyama K, Sun H, Sakai S, et al. Decreased amyloid-β pathologies by intracerebral loading of glycosphingolipid-enriched exosomes in Alzheimer model mice[J]. J Biol Chem, 2014, 289(35): 24488-24498. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M114.577213 |

| [22] |

Dinkins MB, Dasgupta S, Wang G, et al. Exosome reduction in vivo is associated with lower amyloid plaque load in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease[J]. Neurobiol Aging, 2014, 35(8): 1792-1800. DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.02.012 |

| [23] |

Yuyama K, Yamamoto N, Yanagisawa K. Accelerated release of exosome-associated GM1 ganglioside (GM1) by endocytic pathway abnormality:another putative pathway for GM1-induced amyloid fibril formation[J]. J Neurochem, 2008, 105(1): 217-224. DOI:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05128.x |

| [24] |

An K, Klyubin I, Kim Y, et al. Exosomes neutralize synaptic-plasticity-disrupting activity of Aβ assemblies in vivo[J]. Mol Brain, 2013, 6: 47. DOI:10.1186/1756-6606-6-47 |

| [25] |

Dinkins MB, Enasko J, Hernandez C, et al. Neutral Sphingomyelinase-2 Deficiency Ameliorates Alzheimer's Disease Pathology and Improves Cognition in the 5XFAD Mouse[J]. J Neurosci, 2016, 36(33): 8653-8667. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1429-16.2016 |

| [26] |

Yuyama K, Sun H, Usuki S, et al. A potential function for neuronal exosomes:sequestering intracerebral amyloid-β peptide[J]. FEBS Lett, 2015, 589(1): 84-88. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2014.11.027 |

| [27] |

Tamboli IY, Barth E, Christian L, et al. Statins promote the degradation of extracellular amyloid {beta}-peptide by microglia via stimulation of exosome-associated insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) secretion[J]. J Biol Chem, 2010, 285(48): 37405-37414. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M110.149468 |

| [28] |

Katsuda T, Tsuchiya R, Kosaka N, et al. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells secrete functional neprilysin-bound exosomes[J]. Sci Rep, 2013, 3: 1197. DOI:10.1038/srep01197 |

| [29] |

Falker C, Hartmann A, Guett I, et al. Exosomal cellular prion protein drives fibrillization of amyloid beta and counteracts amyloid beta-mediated neurotoxicity[J]. J Neurochem, 2016, 137(1): 88-100. DOI:10.1111/jnc.2016.137.issue-1 |

| [30] |

Joshi P, Turola E, Ruiz A, et al. Microglia convert aggregated amyloid-β into neurotoxic forms through the shedding of microvesicles[J]. Cell Death Differ, 2014, 21(4): 582-593. DOI:10.1038/cdd.2013.180 |

| [31] |

Yang T, Martin P, Fogarty B, et al. Exosome delivered anticancer drugs across the blood-brain barrier for brain cancer therapy in Danio rerio[J]. Pharm Res, 2015, 32(6): 2003-2014. DOI:10.1007/s11095-014-1593-y |

| [32] |

Ittner LM, Ke YD, Delerue F, et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer's disease mouse models[J]. Cell, 2010, 142(3): 387-397. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036 |

| [33] |

Simón D, García-García E, Royo F, et al. Proteostasis of tau. Tau overexpression results in its secretion via membrane vesicles[J]. FEBS Lett, 2012, 586(1): 47-54. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2011.11.022 |

| [34] |

Vandermeeren M, Mercken M, Vanmechelen E, et al. Detection of tau proteins in normal and Alzheimer's disease cerebrospinal fluid with a sensitive sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay[J]. J Neurochem, 1993, 61(5): 1828-1834. DOI:10.1111/jnc.1993.61.issue-5 |

| [35] |

Winston CN, Goetzl EJ, Akers JC, et al. Prediction of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia with neuronally derived blood exosome protein profile[J]. Alzheimers Dement (Amst), 2016, 3: 63-72. |

| [36] |

Polanco JC, Scicluna BJ, Hill AF, et al. Extracellular Vesicles Isolated from the Brains of rTg4510 Mice Seed Tau Protein Aggregation in a Threshold-dependent Manner[J]. J Biol Chem, 2016, 291(24): 12445-12466. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M115.709485 |

| [37] |

Carr F. Microglia:Tau distributors[J]. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2015, 16(12): 702. |

| [38] |

Asai H, Ikezu S, Tsunoda S, et al. Depletion of microglia and inhibition of exosome synthesis halt tau propagation[J]. Nat Neurosci, 2015, 18(11): 1584-1593. DOI:10.1038/nn.4132 |

| [39] |

Vella LJ, Hill AF, Cheng L. Focus on Extracellular Vesicles:Exosomes and Their Role in Protein Trafficking and Biomarker Potential in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's Disease[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2016, 17(2): 173. DOI:10.3390/ijms17020173 |

2017, Vol. 44

2017, Vol. 44