2 上海交通大学海洋学院, 上海 200240)

痕量元素是指地球系统中以超低浓度水平存在的元素。痕量元素作为微量营养盐和生命必要元素,能维持各生态系统正常运行,而某些痕量元素通过富集作用,也可成为有毒元素,危害生态系统安全[1]。自工业革命以来,加强的人类活动极大改变了痕量元素在地球环境中的再分配作用[2~4]。因此,痕量元素的生物地球化学循环作用受到科学家的广泛关注。

保存在极地的雪冰化学记录,由于远离人类活动区,是研究现代和过去大气化学组成演化的有力工具,是在现代海陆分布、气候条件和人类活动影响下,综合评估大气污染物状况、大气环流传输过程的有利代用指标[5~7]。其中,每年通过大气沉降作用保存在雪冰中的痕量元素,可以重建过去区域和全球的气候环境变化,探讨过去人类和自然排放活动对大气环境的影响[7]。极地地区分布大量的冰川和冰盖,代表了地球上最原始的环境,是研究大气污染物传输和痕量元素浓度变化的理想场所[8]。

通过科学考察计划,研究人员最早在南极冰盖和格陵兰冰盖开展了表层雪中痕量元素记录研究[9]。随后,随着分析技术的成熟和科学考察活动的增多,南极内陆和格陵兰冰盖钻取的深冰芯也开展了雪冰中痕量元素研究[10~11]。本文主要综述了极地高纬度典型地区,包括南极冰盖、格陵兰冰盖和加拿大北部雪冰中痕量元素过去近50年以来的研究进展,并对未来极地雪冰中痕量元素研究提出了展望。

1 极地雪冰中痕量元素的研究方法 1.1 雪冰中痕量元素测试方法测定极地雪冰中的痕量元素是一项艰巨的挑战任务,主要因为极地雪冰中的痕量元素浓度极低,有时低于ng/g水平。先前的研究尝试过各种分析方法,以达到极地雪冰中痕量元素浓度的测试需求。最早测定雪冰中痕量元素的方法包括热电离质谱法(Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometry,简称TIMS)[9, 12]、石墨炉吸收光谱法(Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrometry,简称GFAAS)[13]、激光激发原子荧光光谱法(Laser-Excited Atomic Fluorescence Spectrometry,简称LEAFS)[14]、差分脉冲阳极溶出伏安法(Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetry,简称DPASV)[15]等。以上方法由于早期技术和实验条件的限制,存在一些缺陷,例如TIMS昂贵耗时,对样品需求量大[9];GFAAS需要复杂的物理和化学方法进行预富集,极易污染样品[16]。目前极地雪冰中痕量元素测定使用最多的是电感耦合等离子体质谱法(Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry,简称ICP-MS),具有灵敏度高、检出限低以及同时测定多种元素等特点[17~18]。该方法使得极地雪冰中痕量元素的研究得到了很大进步。

然而,目前极地雪冰中痕量元素的测定大多数以常规测试分析为主,缺乏更高分辨率的样品分析。考虑到冰芯底部年层减薄作用[19],常规的采样方法无法获得低积累率区和冰芯底部高度挤压层位的季节变化信息,这为恢复和重建古气候和环境记录带来了挑战。激光-剥蚀-电感耦合等离子体质谱(Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry,简称LA-ICP-MS)是新开发的一种能够高分辨测定样品中痕量元素浓度的技术[20]。早在2001年,研究人员率先尝试利用LA-ICP-MS测定冰芯中的痕量元素浓度变化,获得了约300μm分辨率的冰芯样品信息[21]。最近,美国缅因大学气候变化研究所的研究人员开发了一套激光剥蚀系统,在保证样品不融化的前提下,对冰芯样品进行高分辨率地采样分析,使冰芯样品的采集分辨率提高到了121μm[22]。因此,运用LA-ICP-MS技术测定极地冰芯中超高分辨率痕量元素的研究工作也是未来的发展方向。

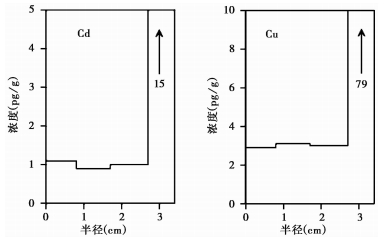

1.2 极地雪冰中痕量元素的采样方法相对于中低纬度雪冰中痕量元素样品的采集,极地地区由于雪冰中极低的痕量元素浓度,对采样要求更为严格。因此,早期极地雪冰中痕量元素的研究如果没有采用防污染措施,必定会造成结果的误差。根据研究目标的不同,采集的雪冰样品可以分析不同时间尺度的大气化学成分信息。例如,表层雪样品用于研究现代沉降的气溶胶组成;浅冰芯可以分析过去几十年或几百年的大气化学成分记录;深冰芯可以研究过去几万或者几十万年的大气化学成分记录[23]。表层雪的采集要求研究人员穿着洁净服、佩戴口罩和一次性低密度聚乙烯(LDPE)手套,在迎风坡且远离当地污染源处使用预先酸洗过的陶瓷刀将表层雪刮掉,然后将样品装入LDPE塑料袋,冷冻状态运输至实验室[24]。采集冰芯样品则需要在冰芯钻取过程中要求无污染或者在实验室内对冰芯进行去污染措施。Ng和Patterson[12]研究表明,使用热钻和带钻井液的钻机钻取的冰芯不适合进行痕量元素分析,这需要严格的去污染措施;而Boutron和Patterson[25]使用预先清洁的聚碳酸酯钻获得了污染较小的浅冰芯样品。在深冰芯钻取过程中,为了抵消在极深处遇到的巨大压力,防止井口闭合,需要用钻孔液填充井口,所以钻孔液对样品的污染不可避免[26~27]。冰芯被污染的外层,可以刮掉用来测定氢氧稳定同位素,但是对于痕量元素分析,必须去污染处理。从图 1中的EPICA冰芯横截面元素浓度分布可以看出冰芯外层的元素浓度已显著大于内层的原始值,因此在冰芯外围测量到的痕量元素浓度应该考虑到内部原始浓度的上限值,确保冰芯污染层已经处理。

|

图 1 东南极Dome C EPICA冰芯横截面中Cd和Cu浓度变化[10] Fig. 1 Changes of Cd, Cu concentrations in the cross section of the EPICA ice core drilled at Dome C, East Antarctica[10] |

另外,储存冰芯的温度可能对污染物的渗透率产生重要影响,因此要确保冰芯在运输过程中始终保持冷冻状态。极地雪冰样品分析之前,大部分要预先酸化消解,这些步骤必须在超级实验室内(1000级),超净工作台(100级)上完成,而处理样品过程选用的试剂(例如超纯水、Optima级别纯硝酸)和酸洗过的实验器具都最大限度的避免极地雪冰样品遭受二次污染。

2 极地雪冰中痕量元素的研究进展 2.1 极地雪冰中表层雪痕量元素记录的探索及存在的问题利用雪冰中保存的痕量元素记录重建大气化学成分变化最早可以追溯至20世纪60年代末。1957~1958年国际地球物理年首次提出在格陵兰岛和南极洲要开展广泛的研究计划,其中包括过去几十万年储存在雪冰中的大气环境记录[28]。但由于极地地区雪冰中痕量元素浓度极低,仪器检测十分困难,从而限制了该项计划的发展。

最早在1967年,Jaworowski[29]发现山地冰川积雪中Pb浓度超过北半球中纬度部分城市的大气沉降值。随后,研究人员陆续在格陵兰岛和南极洲展开了雪冰中痕量元素研究。Murozumi等[9]首次通过对比分析了格陵兰岛北部和南极洲内陆冰盖中Pb浓度,发现格陵兰岛雪冰中Pb浓度比过去2800年里增加了至少200倍,而南极冰盖中Pb浓度则低于检测限,没有发现人为污染。后来,研究人员在格陵兰岛中部多次采集了表层雪样品,结果发现异常高的Zn、Pb富集,猜测可能是火山喷发活动产生,而Fe、Al、Mn等痕量元素主要来源于地壳粉尘贡献,没有发现人为活动影响[30~31]。同样,南极冰盖的表层雪痕量元素记录显示Al、Sc、Th、Sm、V、Mn、Eu、Fe、La、Ce、Co、Cr、Na、K、M、Ca等痕量元素来自地壳风化和海洋气溶胶,一些元素或化合物的再挥发过程也是一种重要来源[31~35]。后来Wolff和Peel[36]在1985年采用了严格的去污染措施,得到了南极半岛表层雪中Al、Cu、Cd、Cu、Pb、Zn等重金属元素的浓度,发现Pb浓度与来自东南极沿岸近期降雪的结果一致[25],而Cd、Cu和Zn的值比之前报道的低10倍,其中的原因可能是先前测定的雪冰样品已经受到污染,或者没有扣除空白值的影响。同样Murozumi等[37]认为在Mizuho站Hg浓度从小于1pg/g增加到最近一些样品中大于20pg/g的数据也是错误的。以上研究表明,由于仪器检测水平限制,早期研究认为南极地区人为污染的重金属元素浓度极低,难以被检测,而格陵兰冰盖测定的痕量元素浓度差异较大,可能原因是仪器测试的误差或者样品受到了人为污染。

2.2 极地雪冰中痕量元素的季节变化特征相对于1970s~1980s早期对极地地区雪冰中表层雪的研究[30~34],后来的研究强调要控制现场采样和分析样品过程中产生的污染问题,更多呈现了高分辨率的连续采样研究,从而获得一年或连续几年的痕量元素季节性变化记录[13, 38]。

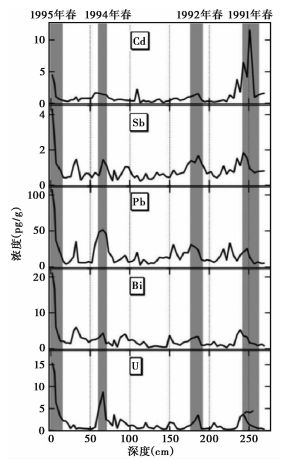

在南极地区,Suttie和Wolff[13]采用了无污染的样品采集和分析技术,得到了南极半岛东海岸积雪样品中Cd、Cu、Pb、Zn等痕量元素的季节性变化记录,结果显示Pb在秋冬季存在极大值,而其他痕量元素没有观察到明显的季节性变化信号;Hong等[38]使用超净无污染措施分析了Law Dome两根冰芯中部分痕量元素记录,包括Pb、Cd、Cu、Zn,结果显示Pb和Cd浓度也存在较强的季节性变化,即冬季的值比春夏季高出2~4倍。在格陵兰冰盖,Wolff和Peel[39]在1988年采用防污染的采样和分析方法,得到格陵兰岛Dye 3雪冰中Cd、Cu、Pb和Zn等痕量元素一年的浓度变化记录,发现这些痕量元素浓度变化具有明显的冬春季最大值特征。Savarino等[40]在1994年评估了格陵兰岛中部积雪中Pb、Cd、Cu、Zn浓度的季节性变化,发现这4种痕量元素存在秋冬季浓度低,春夏季浓度高的特征。同样,Candelone等[41]在1996年采用超净分析技术分析了格陵兰岛中部1.6m雪坑中Pb、Cd、Zn、Cu的变化,发现了这些痕量元素的显著季节变化特征,即冬季值较低,春夏季值高。图 2呈现了Barbante等[42]在2003年测定的格陵兰中部雪坑中部分重金属季节性沉降变化,可以看出这些痕量元素存在显著的春季最大值特征。

|

图 2 格陵兰中部雪坑中部分重金属浓度变化[42]灰色阴影分别代表1995年、1994年、1992年、1991年冬春季浓度最大值 Fig. 2 Changes in the concentration of heavy metals in the snow pits in central Greenland[42]; The gray shades represent the maximum concentrations in the spring of 1995, 1994, 1992, and 1991, respectively |

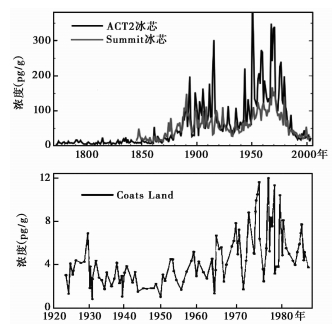

南半球由于密集的人类排放活动起始于20世纪50年代[43~44],因而南极雪冰中痕量元素的年际变化研究时间尺度较短。北极地区由于更靠近人类活动区,人类活动对极地雪冰中痕量元素的影响可以延伸至工业革命以前[45~46],因此利用冰芯记录重建过去百年间人类排放活动变化引起了科学家的广泛关注。从表 1统计的南极冰盖和北极高纬度部分地区重金属元素记录对比可知,近几十年间以来北极地区大部分雪冰中痕量元素的平均浓度显著大于南极地区,反映了北极地区遭受了更严重的人类活动污染。通过以极地雪冰中研究最多的痕量元素Pb为参照(图 3),南极Coats Land地区雪冰中Pb浓度峰值出现在20世纪70~80年代[43],而相似的Pb浓度峰值也在东南极Dome A[47]、Dome F[44]雪坑中出现,其原因很大程度受到南美洲国家化石燃料燃烧和有色金属冶炼活动的影响,然而在近几十年部分重金属浓度下降与环境监管部门的控制有关,这也凸显了制定环境法规对降低有毒重金属排放的重要性[43~44, 47~50]。通过图 3格陵兰ACT2冰芯和Summit冰芯呈现的大气沉降Pb浓度发现,Pb在工业革命后1880~1910年和1950~1980年期间显著上升,其中20世纪初Pb浓度的增加与北美和欧洲的燃煤活动有关,而20世纪中后期Pb浓度的显著增加除了与北美和欧洲的人为活动有关之外,亚洲经济体的兴起也是重要原因[51~52]。同样,在位于加拿大北部的Devon Island冰帽上,研究人员利用63.7m的冰芯,得到1842~1996年间Sb浓度趋势,结果发现北半球工业化后增多的人类排放活动影响了大气沉降Sb浓度,而近期Sb浓度的下降则归因于北美洲国家使用了烟气过滤技术和减排工作的实施[17]。

| 表 1 极地典型地区雪坑中部分痕量元素平均值(pg/g) Table 1 Mean values of partial trace elements in snow pits in typical polar regions(pg/g) |

|

图 3 格陵兰ACT2冰芯[52](黑色)、Summit冰芯[51](灰色)Pb浓度与东南极Coats Land[43]地区雪坑中Pb浓度趋势对比 Fig. 3 Comparison of Pb concentration trends in ACT2 ice core[52](black) and Summit ice core[51](gray) in Greenland with that in Coats Land[43], East Antarctica |

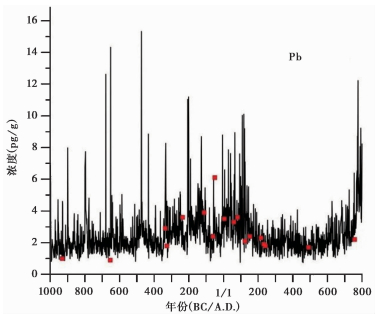

对于北半球工业革命以前人类排放活动的评估,Rosman等[45]利用了格陵兰GRIP冰芯发现600BC~300A.D.期间大规模的Pb排放活动。该冰芯记录发现在中世纪和文艺复兴时期大气Pb、Cu污染与希腊和罗马的Pb-Ag开采和冶炼活动以及Cu生产活动有关[58~60]。后来NGRIP2冰芯高分辨率的采样分析也证实在1100 BC~800A.D.之间的Pb-Ag开采和冶炼活动对中纬度Pb排放量的影响[46](图 4)。

|

图 4 格陵兰NGRIP2冰芯1100 BC~800A.D.的Pb浓度趋势变化红点代表先前报道的GRIP冰芯18个离散点Pb浓度[46] Fig. 4 The Pb concentration trends of NGRIP2 ice core in Greenland for the period 1100 BC~800A.D. The red dots represent the previously reported Pb concentrations at 18 discrete points in the GRIP ice core[46] |

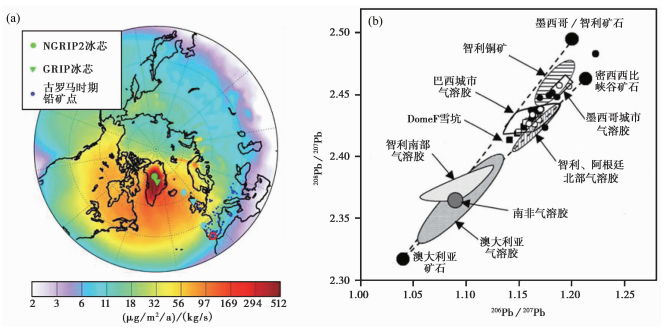

极地雪冰中的痕量元素记录除了重建过去大气化学成分变化,反映人类和自然排放活动历史以外,利用雪冰中痕量元素的同位素组成则可以追踪痕量元素来源,找出雪冰中痕量元素的潜在源区[44]。另外,结合大气传输模型(例如HYSPLIT、FLEXPART)能定量评估潜在源区痕量元素的排放贡献,分析痕量元素大气传输路径[46, 49]。在南极地区,Chang等[44]利用东南极Dome F雪坑中Pb同位素组成与南美洲国家(巴西、智利等)气溶胶、矿石中Pb同位素组成对比(图 5),发现该地雪冰中Pb浓度变化极大可能受南美洲人类排放活动影响;利用1950~2016年每天每6h运行一次的前15天HYSPLIT轨迹,Liu等[49]揭示了东南极冰盖大气颗粒物主要来自大西洋扇区和印度洋扇区,根据气团轨迹频率分布,推测东南极Dome A的重金属主要来自南美洲人类排放活动;Tuohy等[61]分析利用HYSPLIT模型,分析了Fe、Al、Mn、Pb、Tl、As等痕量元素在南极罗斯福岛的路径来源,发现西南极海洋气溶胶以及局地来源贡献占比最大,还有一部分来源于南极内陆贡献。在北极地区,McConnel等[46]利用大气颗粒物传输沉降模型FLEXPART,演算了大气颗粒物沉积通量对格陵兰NGRIP2冰芯中Pb的贡献,如图 5所示,工业革命以前格陵兰岛人类活动影响的大气沉降Pb浓度主要受南欧罗马帝国时期采矿和冶炼排放影响[44, 46]。此外,北极地区也有关于冰芯中Pb同位素组成分析的报道,例如格陵兰ACT2冰芯和Devon Island冰芯,结果一致表明在工业革命以后北极地区大气沉降Pb主要与北美和欧洲的煤炭燃烧活动有关[45, 57]。

|

图 5 (a) 基于FLEXPART模型计算的格陵兰NGRIP2冰芯和GRIP冰芯点大气颗粒物沉积通量[46]和(b)东南极Dome F Pb同位素组成与潜在源区不同介质中Pb同位素组成对比[44] Fig. 5 The deposition flux of atmospheric particulate matter to the Greenland NGRIP2 ice core and GRIP ice core calculated by the FLEXPART model[46]; (b)Comparison of the Pb isotopic composition in Dome F with that in different media in the potential source area[44] |

相比于表层雪和浅冰芯反映的短时间序列的痕量元素变化,极地地区的深冰芯能反映冰期-间冰期气候旋回下的痕量元素浓度变化,最长记录了过去800ka大气环境信息,包括8个冰期-间冰期旋回[10~11],这为古气候和古环境重建提供了一种新的思路。

在南极地区,先后Vostok深冰芯和Dome C获取的EPICA深冰芯分别呈现了过去近400ka和近200ka大气沉降痕量元素记录,结果发现大多数元素具有冰期高值、间冰期低值的特征,其中主要痕量元素浓度变化与不溶性粉尘浓度分布有较好的相关性,表明在冰期粉尘是东南极大气沉降痕量元素的主要来源[10, 62]。同样,Hur等[11]利用EPICA冰芯分析得到过去800ka的Sb和Tl浓度分布记录,结果表明Sb和Tl浓度在冰期浓度较高,主要来源于粉尘和海冰贡献;在间冰期浓度较低,主要来源于火山喷发和海盐飞溅贡献。

在北极地区,格陵兰岛Summit钻取GRIP深冰芯呈现了最后一个气候周期中Pb、Cu、Zn、Cd的浓度变化,研究结果显示[60],气候变化是导致北半球高纬度地区大气沉降Pb、Cu、Zn、Cd浓度变化的主要原因,其中Pb和Cu主要来源于冰期和间冰期的土壤和岩石粉尘排放,而在艾木间冰期到全新世过渡期间,陆地生物排放是Cd的主要来源。

另外,极地深冰芯也呈现了关于大洋初级生产力限制性元素Fe的研究报道[63~65]。Dome C深冰芯重建过去740ka以来Fe变化趋势,覆盖了8个冰期气候循环,结果显示Fe浓度趋势存在明显的周期变化,且基本与粉尘代用指Ca2+的趋势一致,说明在冰期-间冰期尺度上,Dome C地区受到粉尘传输的影响,另外,该结果显示Fe浓度趋势与大气CO2浓度之间表现出明显的反相关关系[63~64]。值得注意的是在格陵兰NEEM深冰芯的Fe研究中,研究人员同样发现Fe元素变化趋势在过去110ka与粉尘浓度变化一致,证实了中亚粉尘对格陵兰冰盖中Fe沉积的贡献[65]。以上基于深冰芯中Fe元素的研究也间接验证了“铁假说”理论[66]。

3 结语和展望极地雪冰中痕量元素的研究经历近50年的发展历程。由于采样手段和分析技术的限制,早期极地地区表层雪中痕量元素研究基本上反映了大气化学成分的变化,而检测到的一些重金属元素的富集可能与采样和分析过程中的人为污染有关[34, 43]。随后雪冰中痕量元素研究强调了采样和分析处理过程中防污染措施,从而测定的一些重金属元素(Pb、Cd、Cu、Zn)富集更倾向于认为受到的人类活动污染,同时也发现这些痕量元素浓度存在季节性变化特征[40~41]。南极雪冰中人类活动影响的痕量元素主要来源于南半球国家化石燃料燃烧、矿物冶炼和开采活动,而近些年的南极科学考察活动和旅游业的兴起也是一部分重要人为污染来源[44]。北极地区雪冰中痕量元素的人类活动来源主要与欧洲和北美过去的化石燃料燃烧、矿物冶炼和开采活动有关,而亚洲随着经济的发展也成为了新兴的排放源[17, 57]。随着分析技术和采样手段的发展,加强的国际间合作使得雪冰中痕量元素研究可以扩展到更长时间尺度(百-千年,冰期-间冰期)以及获得更高分辨率的分析结果[10~11, 46, 52, 57]。这为我们进一步认识过去长时间尺度大气化学成分变化提供了宝贵的资料。

基于以上目前极地雪冰中痕量元素的研究结果,笔者认为未来极地雪冰中痕量元素的研究还需要加强以下两个方面的工作:

(1) 利用LA-ICP-MS技术高分辨率连续测定极地冰芯中关键部分痕量元素记录,为重建古气候和古环境记录提供更多信息。

(2) 加强极地雪冰中新型痕量元素同位素及新元素的研究工作,例如铼锇(Re-Os)同位素组成、Hg同位素组成以及Pb同位素组成等,利用同位素记录结合大气传输模式(例如HYSPLIT、FLEXPART、WRF-Chem等)加强中低纬度向高纬度区域痕量元素输送过程和机制的研究。另外,随着分析技术的发展,未来要进一步加强极地雪冰中新型痕量元素的研究,如碘元素。

| [1] |

Swaine D J. Why trace elements are important[J]. Fuel Processing Technology, 2000, 65-66: 21-33. DOI:10.1016/S0378-3820(99)00073-9 |

| [2] |

Nriagu J O, Pacyna J M. Quantitative assessment of worldwide contamination of air, water and soils by trace metals[J]. Nature, 1988, 333(6169): 134. DOI:10.1038/333134a0 |

| [3] |

Nriagu J O. A global assessment of natural sources of atmospheric trace metals[J]. Nature, 1989, 338(6210): 47. DOI:10.1038/338047a0 |

| [4] |

Pacyna J M, Pacyna E G. An assessment of global and regional emissions of trace metals to the atmosphere from anthropogenic sources worldwide[J]. Environmental Reviews, 2001, 9(4): 269-298. DOI:10.1139/a01-012 |

| [5] |

Wake C P, Dibb J E, Mayewski P A, et al. The chemical composition of aerosols over the eastern Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau during low dust periods[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 1994, 28(4): 695-704. DOI:10.1016/1352-2310(94)90046-9 |

| [6] |

Wake C P, Mayewski P A, Li Z, et al. Modern eolian dust deposition in Central Asia[J]. Tellus B:Chemical and Physical Meteorology, 1994, 46(3): 220-233. DOI:10.3402/tellusb.v46i3.15793 |

| [7] |

Telmer K, Bonham-Carter G F, Kliza D A, et al. The atmospheric transport and deposition of smelter emissions:Evidence from the multi-element geochemistry of snow, Quebec, Canada[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2004, 68(14): 2961-2980. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2003.12.022 |

| [8] |

Boutron C F, Candelone J-P, Hong S. Past and recent changes in the large-scale tropospheric cycles of lead and other heavy metals as documented in Antarctic and Greenland snow and ice:A review[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1994, 58(15): 3217-3225. DOI:10.1016/0016-7037(94)90049-3 |

| [9] |

Murozumi M, Chow T J, Patterson C. Chemical concentrations of pollutant lead aerosols, terrestrial dusts and sea salts in Greenland and Antarctic snow strata[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1969, 33(10): 1247-1294. DOI:10.1016/0016-7037(69)90045-3 |

| [10] |

Gabrielli P, Barbante C, Boutron C, et al. Variations in atmospheric trace elements in Dome C (East Antarctica) ice over the last two climatic cycles[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2005, 39(34): 6420-6429. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.07.025 |

| [11] |

Hur S D, Soyol-Erdene T O, Hwang H J, et al. Climate-related variations in atmospheric Sb and Tl in the EPICA Dome C ice (East Antarctica) during the past 800, 000 years[J]. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 2013, 27(3): 930-940. DOI:10.1002/gbc.20079 |

| [12] |

Ng A, Patterson C. Natural concentrations of lead in ancient Arctic and Antarctic ice[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1981, 45(11): 2109-2121. DOI:10.1016/0016-7037(81)90064-8 |

| [13] |

Suttie E, Wolff E W. Seasonal input of heavy metals to Antarctic snow[J]. Tellus B, 1992, 44(4): 351-357. DOI:10.3402/tellusb.v44i4.15462 |

| [14] |

Bolshov M A, Boutron C F, Ducroz F M, et al. Direct ultratrace determination of cadmium in Antarctic and Greenland snow and ice by laser atomic fluorescence spectrometry[J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 1991, 251(1-2): 169-175. DOI:10.1016/0003-2670(91)87131-P |

| [15] |

Barbante C, Turetta C, Capodaglio G, et al. Recent decrease in the lead concentration of Antarctic snow[J]. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry, 1997, 68(4): 457-477. DOI:10.1080/03067319708030847 |

| [16] |

Boutron C F, Candelone J-P, Hong S. Greenland snow and ice cores:Unique archives of large-scale pollution of the troposphere of the Northern Hemisphere by lead and other heavy metals[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 1995, 160: 233-241. DOI:10.1016/0048-9697(95)04359-9 |

| [17] |

Krachler M, Zheng J, Koerner R, et al. Increasing atmospheric antimony contamination in the Northern Hemisphere:Snow and ice evidence from Devon Island, Arctic Canada[J]. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 2005, 7(12): 1169-1176. DOI:10.1039/b509373b |

| [18] |

Matoba S, Nishikawa M, Watanabe O, et al. Determination of trace elements in an Arctic ice core by ICP/MS with a desolvated micro-concentric nebulizer[J]. Journal of Environmental Chemistry, 1998, 8(3): 421-427. DOI:10.5985/jec.8.421 |

| [19] |

Parrenin F, Barnola J-M, Beer J, et al. The EDC 3 chronology for the EPICA Dome C ice core[J]. Climate of the Past, 2007, 3(3): 485-497. DOI:10.5194/cp-3-485-2007 |

| [20] |

Spaulding N E, Sneed S B, Handley M J, et al. A new multielement method for LA-ICP-MS data acquisition from glacier ice cores[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51(22): 13282-13287. |

| [21] |

Reinhardt H, Kriews M, Miller H, et al. Application of LA-ICP-MS in polar ice core studies[J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2003, 375(8): 1265-1275. DOI:10.1007/s00216-003-1793-5 |

| [22] |

Sneed S B, Mayewski P A, Sayre W, et al. New LA-ICP-MS cryocell and calibration technique for sub-millimeter analysis of ice cores[J]. Journal of Glaciology, 2015, 61(226): 233-242. DOI:10.3189/2015JoG14J139 |

| [23] |

Brown R J, Milton M J. Analytical techniques for trace element analysis:An overview[J]. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2005, 24(3): 266-274. DOI:10.1016/j.trac.2004.11.010 |

| [24] |

Hong S, Lluberas A, Rodriguez F. A clean protocol for determining ultralow heavy metal concentrations:Its application to the analysis of Pb, Cd, Cu, Zn and Mn in Antarctic snow[J]. Korean Journal of Polar Research, 2000, 11(1): 35-47. |

| [25] |

Boutron C F, Patterson C C. The occurrence of lead in Antarctic recent snow, firn deposited over the last two centuries and prehistoric ice[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1983, 47(8): 1355-1368. DOI:10.1016/0016-7037(83)90294-6 |

| [26] |

Vasiliev N I, Talalay P G, Vostok Deep ICE Core Drilling Parties. Twenty years of drilling the deepest hole in ice[J]. Scientific Drilling, 2011, 11: 41-45. DOI:10.5194/sd-11-41-2011 |

| [27] |

Talalay P G. Perspectives for development of ice-core drilling technology:A discussion[J]. Annals of Glaciology, 2014, 55(68): 339-350. DOI:10.3189/2014AoG68A007 |

| [28] |

Langway Jr C, Oeschger H, Dansgaard W. The Greenland ice sheet program in perspective[J]. Greenland Ice Cores:Geophysics, Geochemimistry and Environment, AGU Monograph, 1985, 33: 1-8. DOI:10.1029/GM033p0001 |

| [29] |

Jaworowski Z. Stable and radioactive lead in environment and huamn body[R]. Warsaw (Poland): Institute of Nuclear Research, Report no. NEIC-RR-29.1967: 181.

|

| [30] |

Herron M M, Langway Jr C C, Weiss H V, et al. Atmospheric trace metals and sulfate in the Greenland ice sheet[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1977, 41(7): 915-920. DOI:10.1016/0016-7037(77)90151-X |

| [31] |

Boutron C, Lorius C. Trace metals in Antarctic snows since 1914[J]. Nature, 1979, 277(5697): 551. DOI:10.1038/277551a0 |

| [32] |

Zoller W H, Gladney E, Duce R A. Atmospheric concentrations and sources of trace metals at the South Pole[J]. Science, 1974, 183(4121): 198-200. DOI:10.1126/science.183.4121.198 |

| [33] |

Boutron C. Alkali and alkaline earth enrichments in aerosols deposited in Antarctic snows[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 1979, 13(7): 919-924. DOI:10.1016/0004-6981(79)90002-7 |

| [34] |

Boutron C. Respective influence of global pollution and volcanic eruptions on the past variations of the trace metals content of Antarctic snows since 1880's[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research:Oceans, 1980, 85(C12): 7426-7432. DOI:10.1029/JC085iC12p07426 |

| [35] |

Maenhaut W, Zoller W H, Duce R A, et al. Concentration and size distribution of particulate trace elements in the South Polar atmosphere[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research:Oceans, 1979, 84(C5): 2421-2431. DOI:10.1029/JC084iC05p02421 |

| [36] |

Wolff E W, Peel D. Closer to a true value for heavy metal concentrations in recent Antarctic snow by improved contamination control[J]. Annals of Glaciology, 1985, 7: 61-69. DOI:10.3189/S0260305500005929 |

| [37] |

Murozumi M, Nakamura S, Yoshida Y. Chemical constituents in the surface snow in Mizuho Plateau[J]. Memoirs of National Institute of Polar Research, 1978, 7(Special issue): 255-263. |

| [38] |

Hong S, Boutron C F, Edwards R, et al. Heavy metals in Antarctic ice from Law Dome:Initial results[J]. Environmental Research, 1998, 78(2): 94-103. DOI:10.1006/enrs.1998.3849 |

| [39] |

Wolff E W, Peel D A. Concentrations of cadmium, copper, lead and zinc in snow from near Dye 3 in South Greenland[J]. Annals of Glaciology, 1988, 10: 193-197. DOI:10.1017/S0260305500004420 |

| [40] |

Savarino J, Boutron C F, Jaffrezo J-L. Short-term variations of Pb, Cd, Zn and Cu in recent Greenland snow[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 1994, 28(10): 1731-1737. DOI:10.1016/1352-2310(94)90183-X |

| [41] |

Candelone J-P, Hong S, Boutron C F. An improved method for decontaminating polar snow or ice cores for heavy metal analysis[J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 1994, 299(1): 9-16. DOI:10.1016/0003-2670(94)00327-0 |

| [42] |

Barbante C, Boutron C, Morel C, et al. Seasonal variations of heavy metals in central Greenland snow deposited from 1991 to 1995[J]. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 2003, 5(2): 328-335. DOI:10.1039/b210460a |

| [43] |

Wolff E W, Suttie E D. Antarctic snow record of Southern Hemisphere lead pollution[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 1994, 21(9): 781-784. DOI:10.1029/94GL00656 |

| [44] |

Chang C, Han C, Han Y, et al. Persistent Pb pollution in central East Antarctic snow:A retrospective assessment of sources and control policy implications[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50(22): 12138-12145. |

| [45] |

Rosman K J, Chisholm W, Hong S, et al. Lead from Carthaginian and Roman Spanish mines isotopically identified in Greenland ice dated from 600 BC to 300 AD[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 1997, 31(12): 3413-3416. |

| [46] |

McConnell J R, Wilson A I, Stohl A, et al. Lead pollution recorded in Greenland ice indicates European emissions tracked plagues, wars, and imperial expansion during antiquity[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2018, 115(22): 5726-5731. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1721818115 |

| [47] |

Hua R, Hou S, Li Y, et al. Arsenic record from a 3 m snow pit at Dome Argus, Antarctica[J]. Antarctic Science, 2016, 28(4): 305-312. DOI:10.1017/S0954102016000092 |

| [48] |

Hong S, Soyol-Erdene T-O, Hwang H J, et al. Evidence of global-scale As, Mo, Sb, and Tl atmospheric pollution in the Antarctic snow[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012, 46(21): 11550-11557. |

| [49] |

Liu K, Hou S, Wu S, et al. Assessment of heavy metal contamination in the atmospheric deposition during 1950-2016 AD from a snow pit at Dome A, East Antarctica[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 268: 115848. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115848 |

| [50] |

Zou X, Hou S, Liu K, et al. Uranium record from a 3 m snow pit at Dome Argus, East Antarctica[J]. PloS One, 2018, 13(10): e0206598. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0206598 |

| [51] |

McConnell J R, Lamorey G W, Hutterli M A. A 250-year high-resolution record of Pb flux and crustal enrichment in central Greenland[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2002, 29(23): 1-4. |

| [52] |

McConnell J R, Edwards R. Coal burning leaves toxic heavy metal legacy in the Arctic[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(34): 12140-12144. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0803564105 |

| [53] |

Hur S D, Xiao C, Hong S, et al. Seasonal patterns of heavy metal deposition to the snow on Lambert Glacier basin, East Antarctica[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2007, 41(38): 8567-8578. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.07.012 |

| [54] |

Planchon F A, Boutron C F, Barbante C, et al. Changes in heavy metals in Antarctic snow from Coats Land since the mid -19th to the late -20th century[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2002, 200(1-2): 207-222. DOI:10.1016/S0012-821X(02)00612-X |

| [55] |

Planchon F A, Boutron C F, Barbante C, et al. Short-term variations in the occurrence of heavy metals in Antarctic snow from Coats Land since the 1920s[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2002, 300(1-3): 129-142. DOI:10.1016/S0048-9697(02)00277-2 |

| [56] |

Vallelonga P, Barbante C, Cozzi G, et al. Elemental indicators of natural and anthropogenic aerosol inputs to Law Dome, Antarctica[J]. Annals of Glaciology, 2004, 39: 169-174. DOI:10.3189/172756404781814483 |

| [57] |

Shotyk W, Zheng J, Krachler M, et al. Predominance of industrial Pb in recent snow(1994-2004) and ice(1842-1996) from Devon Island, Arctic Canada[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2005, 32(21). DOI:10.1029/2005GL023860 |

| [58] |

Hong S, Candelone J-P, Patterson C C, et al. Greenland ice evidence of hemispheric lead pollution two millennia ago by Greek and Roman civilizations[J]. Science, 1994, 265(5180): 1841-1843. DOI:10.1126/science.265.5180.1841 |

| [59] |

Hong S, Candelone J-P, Patterson C C, et al. History of ancient copper smelting pollution during Roman and medieval times recorded in Greenland ice[J]. Science, 1996, 272(5259): 246-249. DOI:10.1126/science.272.5259.246 |

| [60] |

Hong S, Candelone J-P, Turetta C, et al. Changes in natural lead, copper, zinc and cadmium concentrations in central Greenland ice from 8250 to 149, 100 years ago:Their association with climatic changes and resultant variations of dominant source contributions[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 1996, 143(1-4): 233-244. DOI:10.1016/0012-821X(96)00137-9 |

| [61] |

Tuohy A, Bertler N, Neff P, et al. Transport and deposition of heavy metals in the Ross Sea Region, Antarctica[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research:Atmospheres, 2015, 120(20): 10996-11011. DOI:10.1002/2015JD023293 |

| [62] |

Gabrielli P, Planchon F A, Hong S, et al. Trace elements in Vostok Antarctic ice during the last four climatic cycles[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2005, 234(1-2): 249-259. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.03.001 |

| [63] |

Gaspari V, Barbante C, Cozzi G, et al. Atmospheric iron fluxes over the last deglaciation:Climatic implications[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2006, 33(3). DOI:10.1029/2005GL024352 |

| [64] |

Wolff E W, Fischer H, Fundel F, et al. Southern Ocean sea-ice extent, productivity and iron flux over the past eight glacial cycles[J]. Nature, 2006, 440(7083): 491-496. DOI:10.1038/nature04614 |

| [65] |

Xiao C, Du Z, Handley M J, et al. Iron in the NEEM ice core relative to Asian loess records over the last glacial-interglacial cycle[J]. National Science Review, 2020, 8(7). DOI:10.1093/nsr/nwaa144 |

| [66] |

Martin J H. Glacial-interglacial CO2 change:The iron hypothesis[J]. Paleoceanography, 1990, 5(1): 1-13. DOI:10.1029/PA005i001p00001 |

2 School of Oceanography, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200240)

Abstract

Due to its unique geographical location and natural conditions, the polar regions have developed the most extensive and concentrated glaciers on the earth, which play a pivotal role in global climate and environmental changes. As a perennial low temperature environment, polar snow and ice can completely preserve the trace element records from the past atmospheric deposition, which are available for tracing sources and reconstructing the past history of human and natural activities. The earliest research on trace elements in polar snow and ice can be traced back to the late 1960s. Early surface snow studies show that trace element records in polar snow and ice basically reflect changes in atmospheric chemical composition, and the major sources of unusually high values of typical crustal elements are attributed to volcanic eruption and sea-salt spray. Trace element records in snow pits and shallow snow cores show that since the Industrial Revolution, enhanced human emission activities(such as fossil fuel combustion, non-ferrous metal smelting, and mineral mining operations) have been the main reason for the enrichment of heavy metal elements in polar snow and ice. The trace elements enriched in Antarctic ice and snow mainly come from South American countries, while the trace elements enriched in Arctic ice and snow mainly come from North America and European countries. In addition, emerging Asian economies have also been important sources of trace elements in Arctic ice and snow since the second half of the 20th century. The polar deep ice core records also found the influence of human activities in southern Europe on the atmospheric deposition of the Greenland ice sheet before the Industrial Revolution. In addition, the characteristics of trace element changes in atmospheric deposition at the glacial-interglacial scale are also presented by deep ice core records. However, these results provide valuable data for reconstructing the past history of anthropogenic and natural activities. Previous studies of trace elements in polar snow and ice mostly focused on conventional test methods and elements. Further work should focus on new isotope records and element studies in snow and ice, and explore new methods(such as laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, LA-ICP-MS) for obtaining ultrahigh-resolution and continuous trace element records in the ice core. 2021, Vol.41

2021, Vol.41