2 自然资源部第一海洋研究所, 海洋沉积与环境地质国家海洋局重点实验室, 山东 青岛 266061;

3 青岛海洋科学与技术试点国家实验室, 山东 青岛 266237;

4 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049;

5 中国科学院海洋大科学中心, 山东 青岛 266071)

底栖有孔虫是海洋生态系统中的重要组成部分,具有种类多、分布广、生命周期短和对环境变化敏感的特征,且一般可以形成能够长期保存的外壳[1~2]。大量研究建立了底栖有孔虫群落与环境变化之间的关系,使其成为古环境反演中重要的研究载体[3~5],并广泛应用于古海洋研究中[6~10]。

相较于大陆架和大洋环境,潮间带区域位于陆地、海洋和大气三者的交汇处,受光照、潮汐、降水、陆源淡水输入及人类活动等因素的影响,其环境变化频繁且剧烈,因此演化出了独特群落结构[4, 11~12]。已有研究证明了包括水深、温度、盐度等环境变化对潮间带有孔虫群落结构和形态影响显著[13~14],使其成功应用于海平面变化[15~16]、海进海退[17~18]、水团[19]以及季风变化[20~22]等古气候的研究中。

对特定区域进行连续的长期调查是研究底栖有孔虫与环境变化间关系的重要途径,同时也是该区域利用有孔虫进行古环境重建的重要依据。已开展的潮间带和潮下带有孔虫的长期调查多集中于大西洋区域[23~25],中国海域的潮间带有孔虫研究较少[26~29]。有研究报道了2010年10月至2012年2月期间对青岛湾潮间带有孔虫群落连续17个月的调查,结果显示该区域含有丰富的底栖有孔虫,相较于高潮带,低潮带区域有孔虫多样性更高且季节性变化更明显,有孔虫丰度和多样性与温度和盐度的变化有一定的相关性[27]。

有孔虫群落具有很强的时间特异性[24, 27]。有研究指出,同一区域内的有孔虫没有可重复的生命周期[30],不同年份间的有孔虫变化趋势可能存在较大差异。有孔虫群落会随长时间尺度上环境的变化而变化,这在环境复杂多变、且受人类活动影响更大的潮间带区域更加明显[31~33]。与此同时,有孔虫的群落分布具有很强的斑块效应,在距离相近、环境因素相差无几的情况下,其丰度和物种组成仍旧可能存在很大差异[34]。青岛湾早期的调查并未设置重复,每月仅在低潮带和高潮带各采集一个样品[27],这大大增加了采样偶然性所带来的误差。本工作自2017年1月至2018年1月,对青岛湾低潮带进行了为期13个月的连续调查研究,每月进行一次样品采集,每次均采集3个重复样品,并分别对39个样品中活体和总体群落的有孔虫物种组成及壳体形态(包括群落丰度、物种多样性、群落组成、壳体大小与畸形)进行分析。这项工作的主要目的是:1)探讨该区域底栖有孔虫群落的季节性变化以及与早期调查结果是否一致;2)比较不同壳质类型和不同种类有孔虫含量及壳体形态季节性变化的异同及其与温度和盐度的关系,探索其应用于重建古环境的可能性;3)与该区域早期的调查结果进行对比,分析较长时间尺度上有孔虫群落的变化。本工作将探究潮间带区域底栖有孔虫群落和壳体形态的季节性和长时间尺度变化及其与温度和盐度变化之间的关系,为其在黄海潮间带区域古环境研究中的应用提供参考。

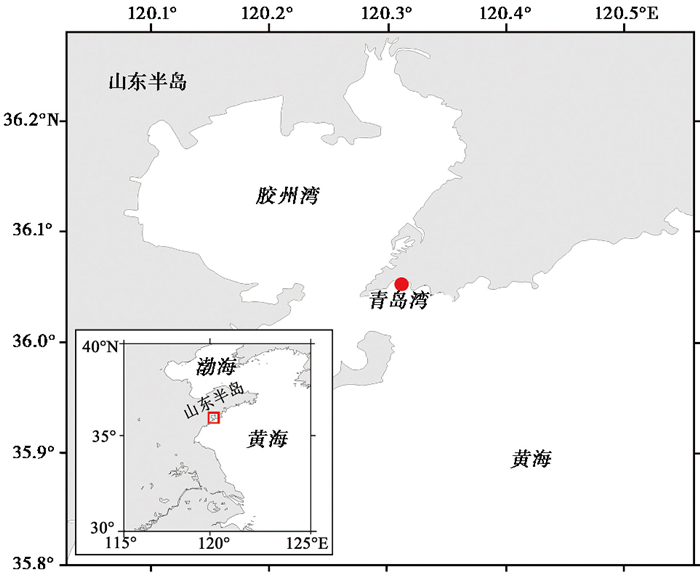

1 材料与方法 1.1 样品采集青岛湾(36.06°N,120.33°E)是位于黄海西海岸的一个开放式海湾,靠近胶州湾出口(图 1)。该区域气候具有明显的季节性变化,年平均气温12.7 ℃,月平均气温-0.5 ℃至25.3 ℃,最低温度和最高温度出现分别为1月和8月[27]。青岛湾潮间带东侧由海岸到海洋分别为砾石、泥沙质和沙质区。2017年1月至2018年1月共计13个月期间每月在泥沙质区域进行采样,采样时在该区域使用采样勺小心刮取表层1 cm内的沉积物,每次均采3个重复样品,并分别装入样品瓶中,共获得39个沉积物样品。立即加入1 g/L的虎红(rose-Bengal)酒精溶液进行固定和染色,用以区分存活和死亡的底栖有孔虫。采样时使用酒精温度计测量该区域的空气温度、海水温度和表层沉积物温度,同时使用便携式折光盐度计测量海水盐度。为了尽量减小退潮时小水体蒸发对盐度产生的影响,选取潮下带大水体区域进行测量以获得海水温度和盐度。

|

图 1 青岛湾潮间带采样位置 Fig. 1 Location of sampling site in intertidal area of Qingdao Bay |

调查获得的39个沉积物样品分别进行处理和分析,处理方法参照中华人民共和国《海洋沉积物间隙生物调查规范》国家标准GB/T 34656-2017[35]。经过48 h染色后将沉积物样品转移至玻璃结晶皿中,完全沉淀过后小心吸取出上层酒精溶液。此后将沉积物放置于50 ℃烘箱中至沉积物完全干燥,随后立即称取各样品干重。称量后沉积物加适量蒸馏水,待其完全浸透后用筛绢包裹,以缓慢流动的自来水清洗,去除沉积物中的有机质和粘土等成分。清洗后的样品再次放置于50 ℃烘箱中完全干燥,随后使用孔径150 μm和63 μm的铜筛筛选样品。由于小粒径(< 150 μm)沉积物中主要包含小个体标本或幼体,这部分有孔虫鉴定困难,所以不少研究中只针对粒径大于150 μm的有孔虫进行探讨[7, 36~37]。同时为了与该区域早期的调查研究和实验生态学研究结果进行比较[26~27, 38],本文只分析粒径>150 μm沉积物中的底栖有孔虫。参考相关区域的有孔虫分类学研究[27, 39~40],本文作者借助于体视显微镜,在中国科学院海洋生物标本馆对有孔虫个体进行鉴定和计数。该区域有孔虫密度高,因此借助二分器将处理后的样品等分,选择恰当的比例进行挑选,每个样品中均挑选200个以上有孔虫样本。

1.3 数据分析有孔虫丰度和群落参数的计算借助于PRIMER(Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research)Ver. 6.1.13软件完成。其中,有孔虫丰度表示为每克干重沉积物中的有孔虫个体数,简写为个/g;物种数(S)表示为各样品中的有孔虫物种数;复合分异度(Shannon-Wiener指数,H′)表示为H'=-∑(PilnPi),其中Pi代表第i种有孔虫在所有有孔虫个体数中的比例[41]。

多房室有孔虫一般有3种壳质类型,分别为玻璃质、瓷质和胶结质[1],本文分析不同壳质类型和各优势种有孔虫丰度和比例的季节性变化。我们测量了所有壳体较为完整的虫体的长径和短径,并以此计算其壳体长宽比。同时参考相关文献对有孔虫畸形壳体的描述和定义[18],对各物种畸形有孔虫进行了计数,以此计算各有孔虫的壳体畸形率。

借助统计与绘图软件Origin(version 2016)将获得的39个样品中的有孔虫丰度、群落参数、物种组成、壳体畸形率等数据按月份进行合并分析,在图片中以平均值+标准误差(standard error)的形式表示。为了分析有孔虫群落和壳体形态与环境因子之间的关系,利用开源软件R语言(version 3.5.1,https://www.r-project.org/)进行了典型相关分析(Canonical Correlation Analysis,简称CCA),并利用SPSS软件(IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences statistics,version 20)进行相关性分析(Spearman correlation)。Spearman相关分析是科学研究中为了分析两个变量之间是否存在相关关系而常采用的非参数检验分析[42]。与回归分析不同,Spearman相关以相关系数r的正负表示变量间是正相关还是负相关,相关系数的绝对值反应变量之间线性关系的强弱程度,通常以p < 0.05作为确认变量间具有统计学意义上相关性的标准。在进行相关性分析前,各项参数指标均经过log10(x+1)标准化处理(x代表有孔虫丰度、物种数、复合分异度和优势种的壳体畸形率等参数)。

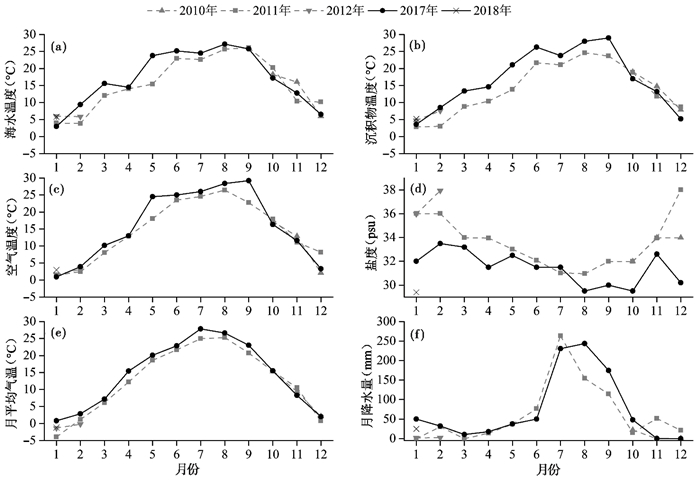

2 结果 2.1 温度和盐度变化整个调查周期中,空气温度、海水温度和表层沉积物温度呈现出较为一致的季节性变化:空气温度的变化范围为0.9 ℃至29.2 ℃、海水温度的变化范围为3.0 ℃至27.2 ℃、表层沉积物温度的变化范围为3.6 ℃至33.5 ℃。三者的最低值均出现在2017年1月,海水温度最高值(27.2 ℃)出现在2017年8月(图 2a),空气和沉积物温度最高值(分别为29.2 ℃和33.5 ℃)出现在2017年9月(图 2b和2c)。盐度的总体变化趋势与温度相反,基本呈冬季和春季高、夏季和秋季低的变化规律,但2017年12月至2018年1月期间盐度较低。调查期间盐度变化范围为29.4 psu至33.5 psu,最低盐度29.4 psu出现在2018年1月,其次出现在2017年8月、9月、10月和12月;最高盐度33.5 psu出现在2017年2月,其次出现在在2017年3月、5月和9月(图 2d)。

|

图 2 青岛湾潮间带温度、盐度和降水量的季节性变化 (a)海水温度(temperature of seawater);(b)表层沉积物温度(temperature of surface sediment);(c)空气温度(temperature of air);(d)盐度(salinity);(e)青岛月平均气温(monthly average temperature of Qingdao);(f)青岛月累积降水量(monthly total precipitation of Qingdao) Fig. 2 Seasonal variations of temperature, salinity and precipitation of intertidal area of Qingdao Bay |

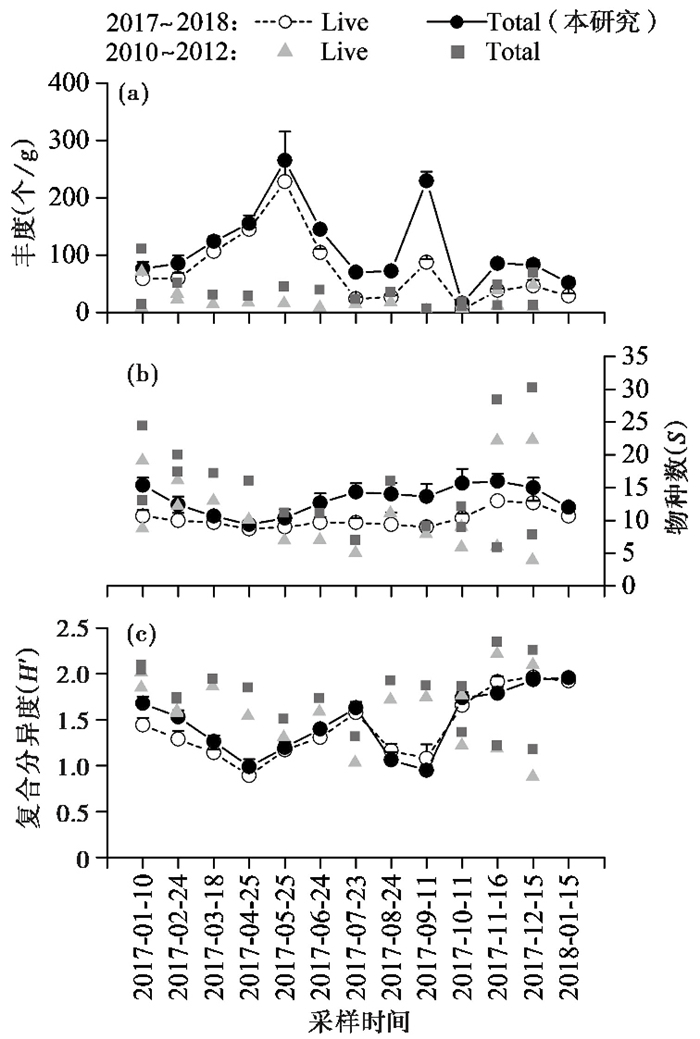

调查结果显示,有孔虫的群落丰度呈现极为明显的季节性变化,且相同采样时间的3个重复样品差异不大(误差线所表示的标准差较小)。活体和总体有孔虫群落丰度均在春季和秋季更高,其中峰值分别出现在2017年5月(活体群落228个/g,总体群落265个/g)和9月(活体群落87个/g,总体群落229个/g),而夏季和冬季丰度较低。活体群落有孔虫丰度平均74个/g,变化范围为5~228个/g;总体群落有孔虫平均丰度112个/g,变化范围为16~265个/g。最低丰度出现在2017年10月(16个/g),最高丰度(265个/g)出现在2017年5月。需要注意的是,2017年9月时有孔虫丰度出现了激增,并在次月迅速下降到调查期间的最低值(图 3a)。

|

图 3 有孔虫群落丰度(a)、物种数(b)和复合分异度(c)的季节性变化(表示为平均值+标准误差) 折线图数据为本研究获得,灰色散点图为2010年10月至2012年2月调查数据[27] Fig. 3 Seasonal variations of foraminiferal abundance (a), species number (b), and complex diversity (c). Data for line + symbol(mean + standard error)were from this study, and data for grey point were from Oct 2010 to Feb 2012 in early study[27] |

活体群落的有孔虫物种数冬季高,其他季节低,平均值为10,变化范围为9~13;而总体群落的物种数则是冬季最高、春季最低,平均值为13,变化范围为9~16。两者的最低值和最高值均分别出现在2017年4月和2017年12月(图 3b)。

复合分异度(Shannon-Wiener指数)在活体群落和总体群落中变化一致,均呈现春秋两季低、夏冬两季高的季节性变化(图 3c)。在有孔虫活体群落和总体群落中,复合分异度平均值分别为1.43和1.47,变化范围分别为0.89~1.96和0.99~1.95。

Spearman相关性分析结果表明(表 1),活体群落和总体群落中,有孔虫丰度均与盐度显著正相关(p < 0.05),Shannon-Wiener指数与温度显著负相关(p < 0.05)。活体群落中物种数与温度负相关(p < 0.05);总体群落中有孔虫丰度与温度正相关(p < 0.05)。

| 表 1 有孔虫群落参数与环境因子之间的Spearman相关性分析* Table 1 Spearman correlations between foraminiferal community parameters and environment factors |

| 表 2 优势种壳体畸形率与环境因子之间的Spearman相关性分析* Table 2 Spearman correlations between abnormal ratios of dominant foraminiferal species and environment factors |

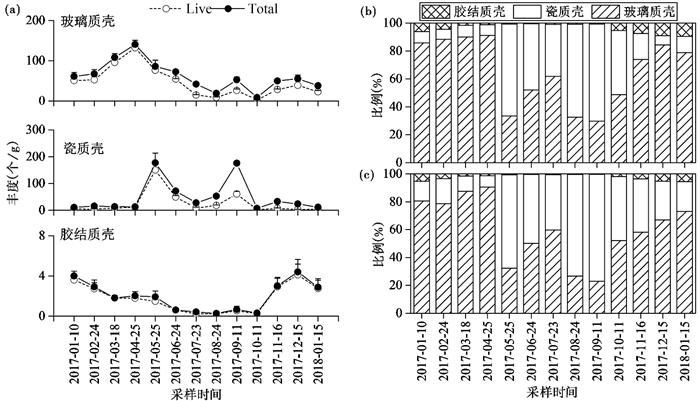

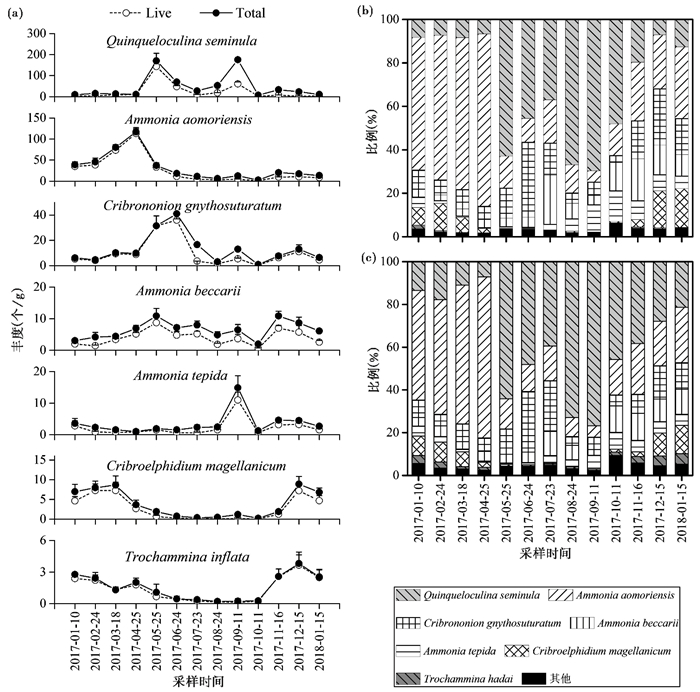

该部分实验中共计挑选14939个有孔虫壳体(其中活体7986个,死亡个体6953个),经鉴定共计16属36种。其中玻璃质有孔虫类群种数(25种)和含量(活体和总体群落中分别占65.53 %和60.05 %)最高,其次为瓷质壳类群(6种,活体和总体群落中含量分别为30.73 %和37.63 %),胶结质类群共5种且含量极低(图 4b和图 4c),相同采样时间的3个重复样品中各壳质类型有孔虫的丰度和比例差异不大。

|

图 4 有孔虫壳质类型丰度和比例的季节性差异 (a)不同壳质类型有孔虫丰度(平均值+标准误差)变化;活体群落(b)和总体群落(c)中不同壳质类型有孔虫平均比例变化 Fig. 4 Seasonal distinction of the abundance and proportion of foraminiferal shell types. (a)Variations of abundance of foraminiferal shell types(mean+standard error); variations of average proportion of foraminiferal shell types in live (b) and total (c) assemblages |

玻璃质壳有孔虫的丰度和比例呈现出了极强的季节性变化。无论是活体群落还是总体群落,玻璃质壳有孔虫的丰度春季最高,秋季最低(图 4a),且在冬春季节时占比超过一半(图 4b和4c),在2017年4月的活体群落中比例更是高达91 % (图 4b)。瓷质壳类群有孔虫丰度表现出明显的双峰变化趋势,在2017年5月和9月的总体群落中(图 4a),出现了彼此接近且远高于其他月份的高丰度。与玻璃质壳类群的比例变化趋势相反,瓷质壳有孔虫在夏秋两季时有着更高的比例(图 4b和图 4c)。其中在2017年9月份活体和总体有孔虫群落中瓷质壳类群的含量高达70 %和77 %,而冬季和春季时通常不足10 %。

在本研究中,任何一个月份的样品平均占比超过5 %的优势种有孔虫共有7种,平均含量由高到低分别为Quinqueloculina seminula、Ammonia aomoriensis、Cribrononion gnythosuturatum、Ammonia beccarii、Ammonia tepida、Cribroelphidium magellanicum和Triloculina inflata。由于某月份采样的3个重复中平均占比超过5 %的物种即定义为优势种,因此可能会出现个别优势种在整个调查周期中的比例不足5 %的情况发生。总体群落与活体群落中有孔虫的属种组成非常类似,且相同采样时间的3个重复样品差异不大(图 5)。总体有孔虫群落中这7种优势种的平均含量分别为37. 10 %、30. 02 %、11. 05 %、7. 26 %、4. 25 %、3. 68 %、1. 91 % (图 5c),而在活体群落中分别为32. 77 %、30. 19 %、12.63 %、8.16 %、5.04 %、4.96 %、3.12 % (图 5b)。

|

图 5 优势种有孔虫丰度和比例的季节性变化 (a)优势种有孔虫丰度(平均值+标准误差)变化;(b)活体群落中物种组成变化;(c)总体群落中物种组成变化 Fig. 5 Seasonal variations of the abundance and proportion of dominant foraminifera (a)Abundance of dominant species(mean+standard error); (b)Species composition of live foraminiferal assemblages; (c)Species composition of total (live+dead)foraminiferal assemblages |

Quinqueloculina seminula作为瓷质壳类群中的绝对优势物种,其丰度和含量的变化趋势与瓷质壳类群近乎一致。玻璃质壳A.aomoriensis的丰度和含量在春季和冬季时更高,2017年4月期间其丰度和比例达到最高,在活体群落和总体群落中分别高达113个/g(79 %)和117个/g(75 %),其他季节较低。尤其是2017年5月至10月期间,有孔虫群落中A.aomoriensis的含量均未超过20 % (图 5b和5c)。C.gnythosuturatum在有孔虫群落中的平均含量超过10 %,仅次于Q.seminula和A. aomoriensis。其含量在2017年5~7月份期间较高,在此期间活体群落和总体群落中含量均为21 %,其他季节相对较低。A.beccarii在群落中的平均含量略低于C.gnythosuturatum,其丰度在2017年5月(活体群落9个/g,总体群落11个/g)和11月(活体群落7个/g,总体群落11个/g)有两个峰值(图 5a)。A.tepida的丰度在大部分月份中较低且没有明显变化,只在2017年9月时出现了急剧升高,而在次月立即下降。C.magellanicum丰度和含量在冬季时较高,而在夏季和秋季时极低。T.inflata作为胶结质类群中唯一的优势种,其丰度和占比也是在冬季时更高(图 5)。

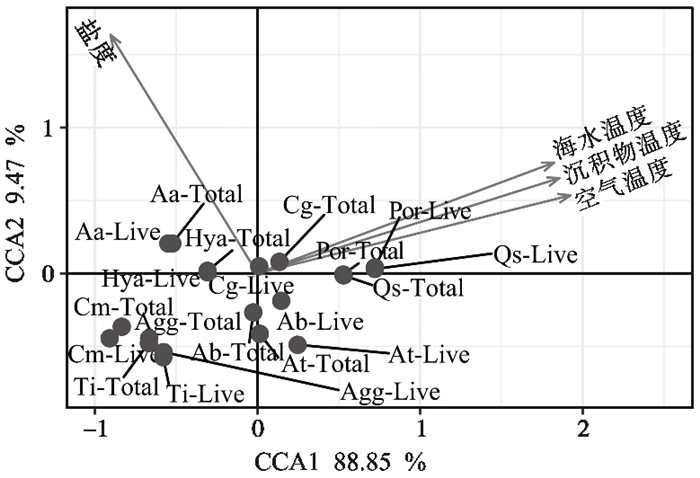

典型相关分析(CCA)结果表明(图 6),温度和盐度变化影响青岛湾潮间带有孔虫的组成。优势种中Q.seminula显示出对高温环境的偏好性,A.aomoriensis则更偏好温度较低的环境,C.gnythosuturatum的含量与温度和盐度变化之间没有明显关系,A.beccarii和A. tepida在低盐度环境下含量略高,C.magellanicum和T. inflata在低温环境下含量更高。

|

图 6 不同壳质类型和优势种有孔虫与温度和盐度的CCA分析(canonical correspondence analysis) Fig. 6 The results of the canonical correspondence analysis(CCA)were shown as dominant species and foraminiferal shell types plotted against the measured temperature and salinity |

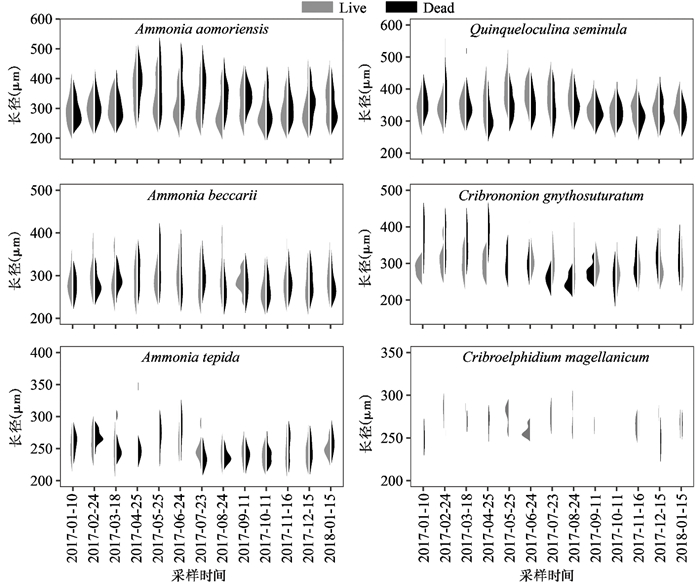

我们测量了个体较为完整的有孔虫壳体的长径,并依据不同采样时间和物种进行分析。结果显示(图 7),优势种Q.seminula和A. aomoriensis长径的变化趋势类似,春季时壳体偏大。2017年4月至8月期间体长超过400 μm的Q.seminula和A.aomoriensis壳体比例明显更高,且活体群落中Q.seminula的最大壳体出现在2017年5月,A.aomoriensis的最大壳体出现在2017年4月。其他优势种壳体大小的分布和季节性变化未发现有明显规律(图 7)。

|

图 7 优势种壳体长径分布的季节性变化 Fig. 7 Seasonal variations of the length of dominant foraminifera |

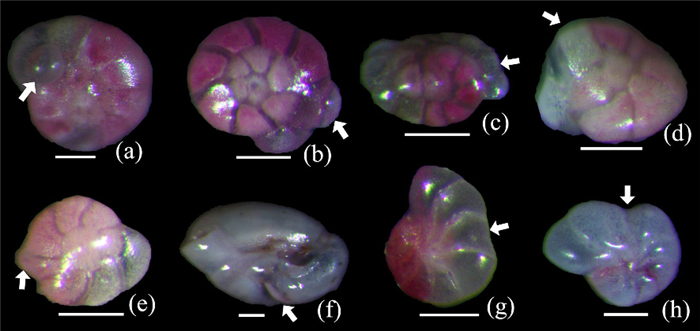

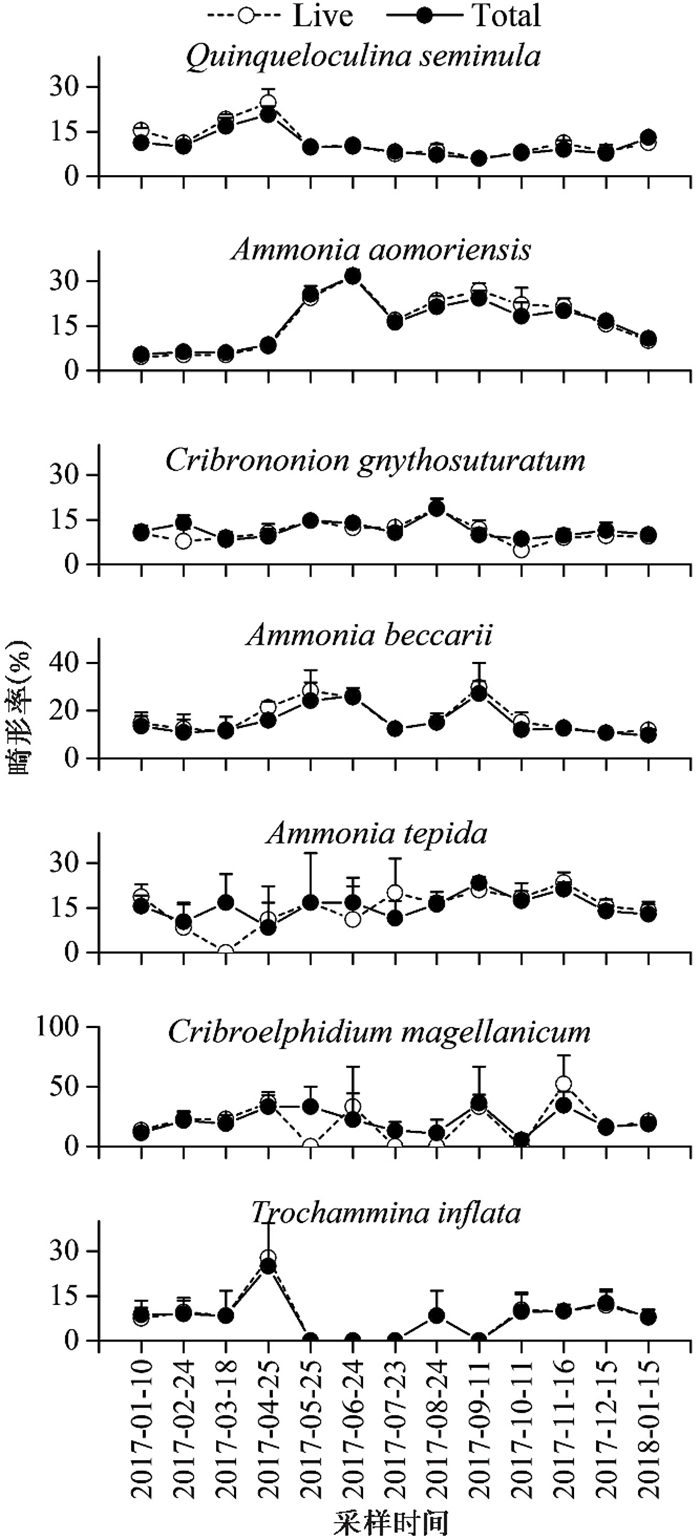

各个样品中均发现有数量不等的有孔虫畸形壳体(图 8),活体群落和总体群落中所有有孔虫壳体的平均畸形率均约为11 %,不同优势种壳体畸形率的季节性变化规律存在差异(图 9)。在活体群落和总体群落中:Q.seminula的壳体畸形率平均值分别为12 %和11 %,变化范围分别为6 % ~25 %和6 % ~21 %,春季时壳体畸形率明显高于其他季节,最低值均出现在2017年9月,最高值均出现在2017年4月;A.aomoriensis的壳体畸形率平均值分别为17 %和16 %,变化范围均为5 % ~32 %,冬季时壳体畸形率明显低于其他季节,最低值均出现在2017年1月,最高值均出现在2017年6月;其他优势种有孔虫的平均丰度较低且多个月份个体数较少,并未呈现明显的变化规律。对优势种壳体畸形率与温度和盐度进行相关性分析,结果显示:Q.seminula壳体畸形率与温度显著负相关;A.aomoriensis壳体畸形率与温度正相关,与盐度负相关(表 2)。

|

图 8 青岛湾潮间带有孔虫常见的壳体畸形 (a)额外房室(additional chambers);(b)房室过量发育(over-developed chambers);(c~d)壳体扭曲(distorted chamber arrangement or change in coiling);(e~f)房室形状异常(aberrant chambers size and shape);(g~h)房室发育不良(reduced chambers) Fig. 8 Micrographs of common abnormal test of foraminifera in Qingdao intertidal flat |

|

图 9 优势种壳体畸形率(平均值+标准误差)的季节性变化 Fig. 9 Seasonal variations of the abnormal ratio of dominant foraminifera(mean+standard error) |

大量文献报道了世界不同海域底栖有孔虫的分布与季节性变化及其与环境间的关系[24, 30],其中不乏有调查研究仅对温度和盐度两个重要环境进行探索分析[23, 43~44]。浙江舟山岛礁潮间带周年调查的结果显示,该区域内有孔虫丰度的季节性变化显著,秋冬季节的有孔虫丰度仅为春季和夏季时的38 % [28];本研究结果显示,2017年1月至2018年1月期间青岛湾潮间带区域的有孔虫含量丰富,其群落丰度、多样性和物种组成同样呈显著的季节性变化,但与2010年至2012年期间存在差异:本研究期间内2月至6月和9月的有孔虫丰度明显更高,但复合分异度更低。认真分析青岛湾早期的调查研究,我们发现有孔虫丰度和多样性在2011年12月至2012年2月期间最高(该时期活体群落和总体群落中有孔虫丰度分别为33~71个/ g和52~113个/ g,Shannon-Wiener指数分别为1.09~2.59和1.72~2.25),且明显高于同为冬季的2010年12月至2011年2月(该时期活体群落和总体群落中有孔虫丰度分别为9~23个/g和13~52个/g,Shannon-Wiener指数分别为0.88~1.84和1.17~2.03)[27]。虽然该区域两次调查期间温度均呈夏高冬低,盐度变化趋势与温度相反,但温度和盐度条件存在一定差异:早期调查期间的沉积物温度变化范围为3.0 ℃至24.9 ℃,盐度变化范围为31 psu至38 psu,沉积物温度高于20 ℃的为2011年6月至9月期间共计4个月;而本研究中沉积物温度明显更高,调查周期内变化范围为3.6 ℃至29.0 ℃,高于20 ℃的共有5个月(2017年5月至9月),且其中3个月温度高于25 ℃;盐度明显更低,变化范围为29.5 psu至33.5 psu,13个月的调查周期内有5个月(2017年8~10月、2017年12月和2018年1月)的盐度低于早期调查的最低值(31 psu)。为了避免海水退潮时由于蒸发等原因造成潮间带区域残余水坑中海水盐度的偏差,我们选取潮下带大水体区域进行海水盐度的测量。青岛地区的气象观测数据(https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cdo-web/datasets#GSOM)也表明,在两次调查时间段内的月平均气温和月累积降水量存在区别(图 2e和2f)。相较于早期调查[27],2017年2月至9月期间的月平均气温更高,月平均气温分别高1.67 ℃、1.08 ℃、3.16 ℃、1.50 ℃、1.16 ℃、2.87 ℃、1.34 ℃和2.29 ℃。且2017年的年平均气温(14.38 ℃)和年累积降水量(895.11 mm)均高于2011年(12.80 ℃和775.72 mm)。近岸海水盐度还受到蒸发量、陆源淡水汇入和人类活动等因素影响。该调查区域附近存在排水口[45],不同年份排水量的差异对此区域海水的盐度也会有一定影响。有文献报道,以色列北部一处潮间带和潮下带区域内的有孔虫受临近电厂高温冷却水影响,靠近排水口附近丰度和多样性降低,且推断30 ℃是显著降低的阈值温度[46]。相较于2010年至2012年期间的调查,本研究中有孔虫群落的丰度明显更高且多样性较低(图 3),物种组成也发生了较为明显的改变(如Quinqueloculina seminula和Cribrononion gnythosuturatum含量的升高),我们推测与2017年较高的温度和较低的盐度环境有关。一般认为,除温度和盐度外,有孔虫季节性丰度的变化还与生产力、pH、粒度等环境变化有关[1],本次调查中受限于样品采集量和分配的问题,我们暂时无法测定包括叶绿素、营养盐和粒度等环境参数,我们将在今后进行更加深入的研究。有孔虫物种组成的季节性变化结果显示(图 5),2017年春季和秋季时部分优势种有孔虫(Ammonia aomoriensis和Q.seminula)爆发,在有孔虫群落中的占比升高,使其物稀有种含量降低甚至消失,造成有孔虫总体数量有限情况下复合分异度(Shannon-Wiener指数)这个综合考虑物种数和各物种比例的多样性参数下降。

3.2 有孔虫属种组成与季节性变化特征底栖有孔虫群落组成的季节性差异广泛存在于世界各地滨海区域的调查研究中[47~48],如巴西里约热内卢附近最大的潟湖系统内,冬季时优势种含量由低到高分别为Ammonia tepida、Ammonia parkinsoniana、Cribroelphidium excavatum和Q.seminula,而夏季时则变为A.tepida、Miliolinella subrotunda、C.excavatum和A.parkinsoniana[47]。青岛湾早期的调查结果显示,低潮带有孔虫群落在2010年10月至2012年2月期间群落组成有较为明显的季节性变化,Ammonia aomoriensis的丰度和比例在冬季和春季时更高;2011年5月时Quinqueloculina seminula丰度较高,占活体群落的一半左右,占比远高于其他月份[27]。本研究结果显示,该区域有孔虫的物种组成在调查期间具有明显的季节性变化,玻璃质壳和瓷质壳有孔虫的比例呈现出非常明显的此消彼长式的季节性变化。玻璃质壳类群在冬季(活体群落和总体群落中平均占比分别为84.33 %和74.82 %)和春季(活体群落和总体群落中平均占比分别为71.53 %和70.16 %)时含量高,其他季节相对较低(活体群落和总体群落中平均含量均不足50 %);而瓷质壳类群在夏季和秋季更占优势(活体群落和总体群落中平均占比分别为47.56 %和53.92 %),冬季和春季时含量非常低(活体群落和总体群落中平均占比分别为16.47 %和23.89 %)。实验生态学研究的结果显示,随着温度的升高,青岛湾有孔虫群落中瓷质壳类群比例升高、玻璃质壳类群比例下降,且温度变化对此产生的影响要远高于盐度及温度和盐度的交互作用[38, 49]。综合本调查和实验生态学的研究结果,我们认为瓷质壳类群更喜好高温环境,而玻璃质壳类群则对温度变化具有更高的耐受性,而这很可能与两种类型有孔虫的壳体组成和钙化途径的不同有关[50]。

潮间带区域是海洋环境中较为极端的环境之一[13, 16],因此在该区域生存的有孔虫属种较少且多数能够适应环境的剧烈变化。本研究中优势种多为潮间带区域常见的物种,在其他海域潮间带调查研究中多有记录。Ammonia属是世界上分布最常见的底栖有孔虫类群之一,广泛分布于潮间带和浅海陆架[1]。优势种中A.aomoriensis和A. beccarii均是黄海浅海陆架及潮间带区域常见物种,且两者生态习性相似,在温度范围约为3~25 ℃、盐度范围约31~38 psu的环境中均有发现[51]。同时有研究结果说明,A.aomoriensis对盐度的耐受范围较高,可以生存在盐度低至2 psu的环境中[52],是典型的广盐性物种。实验室培养研究结果表明A.tepida可以在盐度6~67 psu范围内存活[53]。Q.seminula多分布于水深50 m以浅、正常海水盐度的环境中,对高盐度和低盐度环境也有较强的适应能力[1]。在温度6~18 ℃、盐度15~30 psu的环境下培养青岛湾有孔虫群落的结果显示,相较于盐度,温度对有孔虫物种组成的影响更为显著,温度升高时伴随着玻璃质壳类群向瓷质壳类群(代表种Q.seminula)的转变[38],Ammonia属不同种有孔虫对温度变化的响应不同:A.aomoriensis对温度变化的耐受性高且更喜好温度较低的环境(6~12 ℃),A.beccarii更喜好中等温度(12~18 ℃),A.tepida更喜好较高的温度(12~30 ℃)[49]。本研究结果显示,有孔虫优势种含量呈明显的季节性变化,且不同优势种之间存在差异:2017年5月至9月期间表层沉积物温度明显高于其他月份,此时Q.seminula含量明显更高,A. tepida在2017年9月份期间丰度和比例呈明显高于其他月份的峰值,A.aomoriensis则是在春季丰度更高。结合本研究期间内青岛湾潮间带区域的盐度接近正常海水盐度且变化幅度较小(29.4~33.5 psu),而温度变化范围广(表层沉积物温度3.6~33.5 ℃),推断温度变化是该区域有孔虫物种组成季节性变化的重要影响因素。

青岛湾早期的调查结果显示,该区域有孔虫群落中玻璃质类群最多,其次为瓷质类群,胶结质类群最少,优势种主要包括A.aomoriensis、A. beccarii和Q.seminula[27]。此次调查结果显示该区域有孔虫群落中仍以玻璃质壳类群占优势,优势种中A.aomoriensis仍旧保持着较高的比例,不同的地方在于瓷质壳类群的比例有了较为明显的升高,优势种中Q.seminula和C. gnythosuturatum的比例明显升高,A.beccarii的含量明显降低。同时,两次调查周期内,A.aomoriensis含量均呈现单峰模式,Q.seminula含量呈双峰模式;不同之处在于Q.seminula含量的双峰在2017年出现在5月和9月,早期的调查则出现在春季和冬季。有孔虫群落数年的时间尺度上发生变化并非孤例[54],例如对日本海Alekseev Bight的调查研究表明,该海域有孔虫组合在1985年至1995年间发生了较为明显的变化,Cribroelphidium frigidum和Elphidium advenum分布区域逐渐减小,Trochammina inflata和Eggerella advena成为新的优势种,分布区域逐渐扩张[55]。2001年至2003年期间对法国Bourgneuf海湾南部潮间带的调查研究结果显示,不同年间潮间带有孔虫不具有可重复的生命周期[30]。前文曾提到,相较于2010年至2012年期间[27],本研究调查周期内青岛湾潮间带区域的温度和盐度均有较为明显的差别,夏季时温度更高且高温时间更长,全年盐度较低,这些因素都可能对有孔虫的群落组成及其季节性变化产生影响。

3.3 有孔虫壳体形态有孔虫壳体平均大小和不同大小壳体组成比例同时受生长速度和繁殖周期的共同影响[56]。调查和实验室生态学研究表明,有孔虫在条件适宜的情况下生长速度更快[57]。2017年4月和5月期间,活体群落中A.aomoriensis和Q. seminula分别含有更高比例的较大壳体,这与其各自最高丰度出现的时间相一致,表明此时的潮间带环境分别更适宜A.aomoriensis和Q. seminula。其他优势种的壳体大小分布并未表现出明显的季节性变化,原因主要是该两种之外的优势种有孔虫比例较低,且多个月份时丰度极低,壳体数量少导致偏差严重,不具有统计意义。

有孔虫壳体畸形受多种因素共同影响,其中温度和盐度等外界条件向不适宜环境变化时,有孔虫壳体畸形率升高[18, 58]。例如死海附近水域中活体Ammonia有孔虫个体的高畸形率与季节性高温度(最高达35 ℃)和高盐度(最高达54.5 psu)有关[59];沙特阿拉伯萨尔瓦湾(Salwa Bay)区域高温高盐的环境特征使得该地区有孔虫壳体畸形率高达43 % [60]。本研究结果表明,不同有孔虫优势种的壳体畸形率的季节性变化存在差异,且这些变化与温度有关:Q.seminula在冬季时畸形率更高,且畸形率与温度呈负相关;A.aomoriensis的壳体畸形率则是在冬季时更低,且与温度呈正相关。

3.4 潮间带有孔虫与古环境本文的研究结果表明,青岛湾潮间带表层沉积物中有孔虫活体群落与总体群落属种组成及其季节性变化规律相似性高,说明该研究区域潮流搬运作用不强,埋葬群主要为本地属种,其季节性变化和长时间尺度的变化特征更能反映本地环境(包括温度和盐度等)的变化[28]。有孔虫丰度、多样性、属种组成和壳体形态均呈现明显的季节性变化。A.aomoriensis最高丰度(活体群落和总体群落中分别为113个/g和117个/g)和最大壳体(图 7)出现在2017年4月,春季时含量(活体群落和总体群落中春季平均比例分别为54.52 %和51.40 %)高,冬季时畸形率低(活体群落和总体群落中冬季平均畸形率分别为8.85 %和9.78 %),推测其更喜好中低温度环境;Q.seminula最高丰度(活体群落和总体群落中分别为143个/g和170个/g)和最大壳体(图 7)出现在2017年5月,夏季时比例高(活体群落和总体群落中夏季平均比例分别为49.83 %和53.48 %)、畸形率低(活体群落和总体群落中夏季平均畸形率分别为8.83 %和8.47 %),推测其更耐受高温环境。相较于2010年至2012年期间的调查结果,较长时间尺度上有孔虫群落丰度明显升高、多样性降低、有孔虫的属种组成也发生了较为明显的变化:优势种Q.seminula和C. gnythosuturatum的比例升高,A.beccarii的含量降低,这些变化与2017年较高的温度和较低的盐度有关。影响有孔虫群落变化的潮间带环境复杂,本次调查研究中除温度和盐度变化外,由于样品数量和分配的原因现在未能获得的包括营养盐、有机质、初级生产力、沉积物粒度等环境因子也可能对其产生影响,这需要我们在今后进行更加细致全面和更长时间尺度的调查研究。

4 结论本研究对2017年1月至2018年1月期间青岛湾低潮带表层1 cm沉积物中的有孔虫进行了连续13个月的调查,每月采集一次样品,每次采集3个重复样品。通过对活体和总体底栖有孔虫群落丰度、多样性参数、物种组成、壳体大小和畸形率,探究底栖有孔虫群落结构和壳体形态的季节性变化及其与温度和盐度变化之间的关系。同时与同区域在2010年10月至2012年2月期间的研究结果进行对比,探究长时间尺度下该区域有孔虫群落的变化及其与环境变化之间的关系。结果表明:

(1) 青岛湾潮间带活体和总体有孔虫群落组成相似度高,以本地埋藏为主,优势种主要为Quinqueloculina seminula、Ammonia aomoriensis、Cribrononion gnythosuturatum和Ammonia beccarii。有孔虫群落丰度和多样性呈现显著的季节性变化,其中有孔虫丰度在春季和秋季时高,复合分异度(Shannon-Wiener指数)则在夏季和冬季时高。

(2) 相较于2010至2012年期间的调查结果,该区域的有孔虫丰度升高、多样性降低,属种组成具有较为明显的差异,A.aomoriensis仍然保持着较高含量,但Q.seminula和C. gnythosuturatum的丰度和比例均有明显升高。这些变化与2017年2月至9月期间较高的温度和全年较低的盐度有关。

(3) 底栖有孔虫优势种含量与壳体形态呈现明显的季节性变化,且不同优势种之间存在明显差异,表现为:A.aomoriensis最高丰度和最大壳体出现在2017年4月,春季时含量高,冬季时畸形率低,推测其更喜好中低温度环境;Q.seminula最高丰度和最大壳体出现在2017年5月,夏季时比例高、畸形率低,推测其更耐受高温环境。

本研究结果预示应用潮间带有孔虫群落重建古环境时,有孔虫丰度、种类组成、壳体形态都存在明显的季节性因素,需综合考虑群落与食物环境的关系以及沉积速率等因素长时间尺度下属种组成与环境变化之间的关系。

致谢: 感谢胶州湾生态站在野外采样中提供的帮助,感谢审稿专家的修改意见!

| [1] |

Murray J W. Ecology and Palaeoecology of Benthic Foraminifera[M]. Harlow, Essex, England: Longman Scientific and Technical, 1991: 1-397.

|

| [2] |

Lei Y L, Stumm K, Wickham S A, et al. Distributions and biomass of benthic ciliates, foraminifera and amoeboid protists in marine, brackish, and freshwater sediments[J]. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 2014, 61(5): 493-508. |

| [3] |

Annin V K. Benthic foraminifera assemblages as bottom environmental indicators, Posiet Bay, Sea of Japan[J]. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 2001, 20(1): 9-29. |

| [4] |

Hawkes A D, Horton B P, Nelson A R, et al. The application of intertidal foraminifera to reconstruct coastal subsidence during the giant Cascadia earthquake of AD 1700 in Oregon, USA[J]. Quaternary International, 2010, 221(1-2): 116-140. |

| [5] |

汪品先. 微体化石在海侵研究中的应用与错用[J]. 第四纪研究, 1992(4): 321-331. Wang Pinxian. The use and misuse of microfossils in marine transgression studies[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 1992(4): 321-331. |

| [6] |

Hallock P, Lidz B H, Cockey-Burkhard E M, et al. Foraminifera as bioindicators in coral reef assessment and monitoring:The FORAM Index[J]. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2003, 81(1): 221-238. |

| [7] |

Jian Z, Wang L, Kienast M, et al. Benthic foraminiferal paleoceanography of the South China Sea over the last 40, 000 years[J]. Marine Geology, 1999, 156(1-4): 159-186. |

| [8] |

Alve E, Murray J W. Marginal marine environments of the Skagerrak and Kattegat:A baseline study of living(stained) benthic foraminiferal ecology[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 1999, 146(1-4): 171-193. |

| [9] |

翦知盡, 王律江, Kienast M. 南海晚第四纪表层古生产力与东亚季风变迁[J]. 第四纪研究, 1999(1): 32-40. Jian Zhimin, Wang Lüjiang, Kienast M. Late Quaternary surface paleoproductivity and variations of the East Asian monsoon in the South China Sea[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 1999(1): 32-40. |

| [10] |

常凤鸣, 李铁刚, 庄丽华, 等. 近3000 cal.a B. P.以来东海东北部环境异常及其与全新世El Niño活动的可能联系[J]. 第四纪研究, 2008, 28(3): 472-481. Chang Fengming, Li Tiegang, Zhuang Lihua, et al. The environmental anomalies in the Northeastern East China Sea science about 3000 cal.a B. P. and its possible relation to El Niño activity in the Holocene[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2008, 28(3): 472-481. |

| [11] |

Doo S, Hamylton S, Byrne M. Reef-scale assessment of intertidal large benthic foraminifera populations on one tree Island, great barrier reef and their future carbonate production potential in a warming ocean[J]. Zoological Studies, 2012, 51(8): 1298-1307. |

| [12] |

Berkeley A, Perry C T, Smithers S G, et al. A review of the ecological and taphonomic controls on foraminiferal assemblage development in intertidal environments[J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 2007, 83(3-4): 205-230. |

| [13] |

Papaspyrou S, Diz P, García-Robledo E, et al. Benthic foraminiferal community changes and their relationship to environmental dynamics in intertidal muddy sediments (Bay of Cádiz, SW Spain)[J]. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2013, 490: 121-135. DOI:10.3354/meps10447 |

| [14] |

Allison N, Austin W, Paterson D, et al. Culture studies of the benthic foraminifera Elphidium williamsoni:Evaluating pH, Δ[J]. Chemical Geology, 2010, 274(1-2): 87-93. |

| [15] |

Horton B P, Edwards R J, Lloyd J M. UK intertidal foraminiferal distributions:Implications for sea-level studies[J]. Marine Micropaleontology, 1999, 36(4): 205-223. |

| [16] |

Williams H F L. Intertidal benthic foraminiferal biofacies on the central Gulf Coast of Texas; modern distribution and application to sea level reconstruction[J]. Micropaleontology, 1994, 40(2): 169-183. |

| [17] |

Leorri E, Martin R, Mclaughlin P. Holocene environmental and parasequence development of the St. Jones Estuary, Delaware (USA):Foraminiferal proxies of natural climatic and anthropogenic change[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2006, 241(3-4): 590-607. |

| [18] |

Martin R E. Environmental Micropaleontology:The Application of Microfossils to Environmental Geology[M]. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, 2000: 191-215.

|

| [19] |

叶翔, 徐勇航, 王爱军, 等. 海南岛东南部陆架晚全新世以来海洋沉积物来源与环境变化特征[J]. 第四纪研究, 2016, 36(1): 18-30. Ye Xiang, Xu Yonghang, Wang Aijun, et al. Variations in sediment source and marine environment characteristics during the Late Holocene on the continental shelf off southeastern Hainan Island[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2016, 36(1): 18-30. |

| [20] |

Nigam R, Khare N, Borole D V. Can benthic foraminiferal morpho-groups be used as indicators of paleomonsoonal precipitation?[J]. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 1992, 34(6): 533-542. |

| [21] |

Khare N, Nigam R, Hashimi N H. Revealing monsoonal variability of the last 2, 500 years over India using sedimentological and foraminiferal proxies[J]. Facies, 2008, 54(2): 167-173. |

| [22] |

黄宝琦, 成鑫荣, 翦知盡, 等. 晚上新世以来南海北部上部水体结构变化及东亚季风演化[J]. 第四纪研究, 2004, 24(1): 110-115. Huang Baoqi, Cheng Xinrong, Jian Zhimin, et al. Variations in upper ocean structure in the South China Sea and the evolution of the East Asian monsoons since Late Pliocene[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2004, 24(1): 110-115. |

| [23] |

Korsun S, Hald M, Golikova E, et al. Intertidal foraminiferal fauna and the distribution of Elphidiidae at Chupa Inlet, western White Sea[J]. Marine Biology Research, 2014, 10(2): 153-166. |

| [24] |

Berkeley A, Perry C T, Smithers S G, et al. The spatial and vertical distribution of living(stained) benthic foraminifera from a tropical, intertidal environment, north Queensland, Australia[J]. Marine Micropaleontology, 2008, 69(2): 240-261. |

| [25] |

Patterson R T. Intertidal benthic foraminiferal biofacies on the Fraser River Delta, British Columbia; modern distribution and paleoecological importance[J]. Micropaleontology, 1990, 36(3): 229-244. |

| [26] |

Lei Y, Li T, Nigam R, et al. Environmental significance of morphological variations in the foraminifer Ammonia aomoriensis (Asano, 1951) and its molecular identification:A study from the Yellow Sea and East China Sea, PR China[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2017, 483: 49-57. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.05.010 |

| [27] |

Lei Y, Li T, Jian Z, et al. Taxonomy and distribution of benthic foraminifera in an intertidal zone of the Yellow Sea, PR China:Correlations with sediment temperature and salinity[J]. Marine Micropaleontology, 2017, 133: 1-20. DOI:10.1016/j.marmicro.2017.04.005 |

| [28] |

桂峰, 朱望远, 赵晟, 等. 浙江舟山岛礁潮间带有孔虫种群季节性生态特征研究[J]. 微体古生物学报, 2016, 33(2): 162-169. Gui Feng, Zhu Wangyuan, Zhao Sheng, et al. Study of intertidal foraminifera seasonal ecological characteristics of the Zhoushan Islands, Zhejiang Province, East China[J]. Acta Micropalaeontologica Sinica, 2016, 33(2): 162-169. |

| [29] |

俞宙菲, 类彦立, 李铁刚. 青岛湾潮间带活体底栖有孔虫Ammonia aomoriensis(Asano, 1951)壳体δ18O值的季节变化[J]. 海洋科学, 2016, 40(7): 132-139. Yu Zhoufei, Lei Yanli, Li Tiegang. Seasonal oxygen isotope variation of a living benthic foraminifera Ammonia aomoriensis (Asano, 1951) in the intertidal area of Qingdao Bay, Yellow Sea, China[J]. Marine Sciences, 2016, 40(7): 132-139. |

| [30] |

Morvan J, Debenay J-P, Jorissen F, et al. Patchiness and life cycle of intertidal foraminifera:Implication for environmental and paleoenvironmental interpretation[J]. Marine Micropaleontology, 2006, 61(1-3): 131-154. |

| [31] |

Payne J L, Jost A B, Wang S C, et al. A shift in the long-term mode of foraminiferan size evolution caused by the end-permian mass extinction[J]. Evolution, 2013, 67(3): 816-827. |

| [32] |

Tiwari R K, Rao K N N. A statistically significant long term characteristic time-scale of test size variation of Calcareous Trochospiral Benthic Foraminifera(CTBF) during the past 120 m.y.[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2003, 30(5): 211-214. |

| [33] |

Gouleau D, Jouanneau J M, Weber O, et al. Short-and long-term sedimentation on Montportail-Brouage intertidal mudflat, Marennes-Oléron Bay(France)[J]. Continental Shelf Research, 2000, 20(12-13): 1513-1530. |

| [34] |

Buzas M A, Hayek L-A C, Jett J A, et al. Pulsating Patches History and Analyses of Spatial, Seasonal, and Yearly Distribution of Living Benthic Foraminifera[M]. Washington D C: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2015: 1-91.

|

| [35] |

GB/T 34656-2017, 中华人民共和国国家标准: 海洋沉积物间隙生物调查规范[S].北京: 中国标准出版社, 2017: 1-106. GB/T 34656-2017, Specification for Marine Sediment Interstitial Biota Survey. National Standard of the People's Republic of China[S]. Beijing: China Standard Press, 2017: 1-106. |

| [36] |

Goineau A, Fontanier C, Jorissen F J, et al. Live (stained) benthic foraminifera from the RhØne prodelta(Gulf of Lion, NW Mediterranean):Environmental controls on a river-dominated shelf[J]. Journal of Sea Research, 2011, 65(1): 58-75. |

| [37] |

Fontanier C, Jorissen F J, Licari L, et al. Live benthic foraminiferal faunas from the Bay of Biscay:Faunal density, composition, and microhabitats[J]. Deep-Sea Research Part Ⅰ:Oceanographic Research Papers, 2002, 49(4): 751-785. |

| [38] |

Dong S, Lei Y, Li T, et al. Responses of benthic foraminifera to changes of temperature and salinity:Results from a laboratory culture experiment[J]. Science China:Earth Sciences, 2019, 62(2): 459-472. |

| [39] |

汪品先, 章纪军, 赵泉鸿, 等. 东海底质中的有孔虫和介形虫[M]. 北京: 海洋出版社, 1988: 1-438. Wang Pinxian, Zhang Jijun, Zhao Quanhong, et al. Foraminifera and Ostracodes in Surface Sediment of the East China Sea[M]. Beijing: China Ocean Press, 1988: 1-438. |

| [40] |

Lei Y, Li T. Atlas of Benthic Foraminifera from China Seas:The Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea[M]. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2016: 1-399.

|

| [41] |

Clarke K R, Gorley R N. Primer V6:User Manual/Tutorial[M]. Plymouth UK: Plymouth Marine Laboratory, 2006: 1-190.

|

| [42] |

Hauke J, Kossowski T. Comparison of values of Pearson's and Spearman's correlation coefficients on the same sets of data[J]. Quaestiones Geographicae, 2011, 30(2): 87-93. |

| [43] |

Horton B P, Murray J W. The roles of elevation and salinity as primary controls on living foraminiferal distributions:Cowpen Marsh, Tees Estuary, UK[J]. Marine Micropaleontology, 2007, 63(3): 169-186. |

| [44] |

Kaushik T, Murugan T, Dagar S S. Morphological variation in the porcelaneous benthic foraminifer Quinqueloculina seminula (Linnaeus, 1758):Genotypes or Morphotypes? A detailed morphotaxonomic, molecular and ecological investigation[J]. Marine Micropaleontology, 2019, 150: 101748. DOI:10.1016/j.marmico.2019.101748 |

| [45] |

杜永芬, 徐奎栋, 类彦立, 等. 青岛湾小型底栖生物周年数量分布与沉积环境[J]. 生态学报, 2011, 31(2): 431-440. Du Yongfen, Xu Kuidong, Lei Yanli, et al. Annual quantitative distribution of meiofauna in relation to sediment environment in Qingdao Bay[J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2011, 31(2): 431-440. |

| [46] |

Arieli R N, Almogi-Labin A, Abramovich S, et al. The effect of thermal pollution on benthic foraminiferal assemblages in the Mediterranean shoreface adjacent to Hadera Power Plant(Israel)[J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2011, 62(5): 1002-1012. |

| [47] |

Belart P, Habib R, Raposo D, et al. Seasonal dynamics of benthic foraminiferal biocoenosis in the tropical Saquarema Lagoonal System(Brazil)[J]. Estuaries and Coasts, 2019, 42(3): 822-841. |

| [48] |

Saad S A, Wade C M. Seasonal and spatial variations of saltmarsh benthic foraminiferal communities from North Norfolk, England[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2017, 73(3): 539-555. |

| [49] |

Li M, Lei Y, Li T, et al. Impact of temperature on intertidal foraminifera:Results from laboratory culture experiment[J]. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2019, 520: 151224. DOI:10.1016/j.jembe.2019.151224 |

| [50] |

de Nooijer L J, Toyofuku T, Kitazato H. Foraminifera promote calcification by elevating their intracellular pH[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(36): 15374-15378. |

| [51] |

类彦立, 李铁刚. 奥茅卷转虫Ammonia aomoriensis (Asano, 1951)与毕克卷转虫Ammonia beccarii(Linnaeus, 1758) (有孔虫)的分类学以及在黄东海分布的温盐深特征比较研究[J]. 微体古生物学报, 2015, 32(1): 1-19. Lei Yanli, Li Tiegang. Ammonia aomoriensis (Asano, 1951) and Ammonia beccarii(Linnaeus, 1758) (Foraminifera):Comparisons on their taxonomy and ecological distributions correlated to temperature, salinity and depth in the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea[J]. Acta Micropalaeontologica Sinica, 2015, 32(1): 1-19. |

| [52] |

Nikulina A, Polovodova I, Schønfeld J. Foraminiferal response to environmental changes in Kiel Fjord, SW Baltic Sea[J]. eEarth, 2008, 3: 37-49. DOI:10.5194/ee-3-37-2008 |

| [53] |

Bradshaw J S. Laboratory studies on the rate of growth of the foraminifer Streblus beccarii (Linné) var. tepida (Cushman)[J]. Journal of Paleontology, 1957, 31(6): 1138-1147. |

| [54] |

Buzas M A, Hayek L-A C. A case for long-term monitoring of the Indian River Lagoon, Florida:Foraminiferal densities, 1977-1996[J]. Bulletin of Marine Science, 2000, 67(2): 805-814. |

| [55] |

Pavlyuk O N, Preobrazhenskaya T V, Tarasova T S. Annual changes in meiobenthos community structure in Alekseev Bight, Sea of Japan[J]. Russian Journal of Marine Biology, 2001, 27(2): 105-110. |

| [56] |

Johann H. Foraminiferal growth and test development[J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 2018, 185: 140-162. DOI:10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.06.001 |

| [57] |

Phleger F B, Soutar A. Production of benthic foraminifera in three East Pacific oxygen minima[J]. Micropaleontology, 1973, 19(1): 110-115. |

| [58] |

Boltovskoy E, Scott D B, Medioli F S. Morphological variations of benthic foraminiferal tests in response to changes in ecological parameters:A review[J]. Journal of Paleontology, 1991, 65(2): 175-185. |

| [59] |

Almogi-Labin A, Perelis-Grossovicz L, Raab M. Living Ammonia from a hypersaline inland pool, Dead Sea area, Israel[J]. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 1992, 22(3): 257-266. |

| [60] |

Amao A O, Kaminski M A, Babalola L. Benthic foraminifera in hypersaline Salwa Bay (Saudi Arabia):An insight into future climate change in the gulf region?[J]. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 2018, 48(1): 29-40. |

2 Key Laboratory of Marine Sedimentology and Environmental Geology, First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Qingdao 266061, Shandong;

3 Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology(Qingdao), Qingdao 266237, Shandong;

4 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049;

5 Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, Shandong)

Abstract

The relationship between foraminifera and environmental changes was the base of its use in paleoenvironmental reconstruction. Long-term investigation was an important way to obtain these relationships. Qingdao intertidal zone was located in the west of the Yellow Sea, PR China which with an obvious seasonal environmental variation. The sediment in east part of this area were gravel, silt-sand, and sand respectively from shore to sea. Early study which undertook from 2010 to 2012 pointed the seasonal changes occurred in abundance, diversity and species composition of benthic foraminifera in this flat. This study was aimed to explore the relationship between the seasonal and long-term foraminiferal variations and environment changes in this region.In this study, benthic foraminifera from the surface 1 cm sediments in the silt-sand of Qingdao intertidal zone(36.06°N, 120.33°E) was investigated monthly(one sampling each month)from January 2017 to January 2018. Three samples were collected for each sampling and 39 samples were obtained. Samples of sediments were fixed with 95% ethanol with 1 g/L rose-Bengal immediately for distinguish the living and dead foraminifera. Temperature(for air, sea water, and surface sediment)and salinity(for sea water)were measured simultaneously. A total of 14939 foraminiferal specimens(7986 living specimens and 6953 dead specimens)belong to 36 species of 16 genera were obtained and analyzed respectively.The results showed that the foraminiferal abundance, diversity, species composition and test morphology of the intertidal foraminifera in Qingdao bay showed obvious seasonal changes. Benthic foraminifera from live and total assemblages showed similar species composition and seasonal changes. Therefore, most of foraminifera in this area were local species(dominant by Quinqueloculina seminula, Ammonia aomoriensis, Cribrononion gnythosuturatum and Ammonia beccarii)which means that the seasonal and long-term changes in foraminiferal abundance, diversity, species composition, test size and test abnormality reflect local environmental variations. Compared with the results of investigation from 2010 to 2012, the community parameters and species composition of benthic foraminifera in Qingdao Bay have changed significantly. In the aspect of community parameters, foraminifera abundance was higher in spring and autumn, while the Shannon-wiener index and evenness index were higher in summer and winter. And for species composition, the content of A.aomoriensis remained high as before, while the abundance and proportion of Q.seminula and C. gnythosuturatum increased significantly. These changes were presumed to be related to the higher temperature from February to September 2017 and lower salinity in the whole year of 2017 compared with environment in the same region in 2012. The seasonal changes of the content and test abnormality of dominant species were different from each other. The highest abundant and maximum test size in April 2017, the higher content in spring, and the lower abnormal ratio in winter showed the preference of A.aomoriensis for medium and low temperature. The highest abundant and maximum test size in May 2017, the higher content and lower abnormal ratio in summer showed the tolerance of Q.seminula for high temperature. These results suggested that there were obvious seasonal changes in the abundance, species composition, and shell morphology of foraminifera, and the relationship between the changes of foraminiferal species composition and environment from long-term investigation should be considered when reconstructing paleoenvironments with the intertidal foraminifera community. 2020, Vol.40

2020, Vol.40