2 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049;

3 中国科学院海洋大科学研究中心, 山东 青岛 266071;

4 青岛海洋科学与技术试点国家实验室, 海洋地质过程与环境功能实验室, 山东 青岛 266237;

5 自然资源部第一海洋研究所, 海洋沉积与环境地质重点实验室, 山东 青岛 266061)

海表温度(Sea Surface Temperature, 简称SST)高于28 ℃的热带西太平洋暖池(Western Pacific Warm Pool, 简称WPWP), 是全球海气相互作用最活跃的地区, 也是驱动全球大气环流最大的热源[1]。作为中低纬度地区热量和水汽的一个主要来源, WPWP的变异与亚洲季风和ENSO等活动密切相关[2], 相当程度上影响着亚太地区的气候变化和自然灾害的形成。而ENSO作为现代最强的年际异常信号, 对全球气候都有着显著的影响[3~4]。El Niño发生时, 西太平洋的暖水中心增强且向东移动[5], 热带降雨带东移导致大气低层风场改变, 并通过大气遥相关影响到全球广泛地区。由于ENSO在全球气候系统发挥的重要作用, 其已成为长期天气预报和气候预测中考虑的首要因素, 是现代物理海洋学和气候学的重点研究领域之一。

在年际和年代际尺度上, 热带太平洋通过ENSO过程对全球短期气候异常的影响十分显著[6]。但在轨道尺度的古气候变化研究中, 前人多强调北半球高纬地区的主导作用, 而近年来一系列古海洋学证据发现冰消期热带海区的表层海水变暖要领先于北半球高纬地区[7~10], 显示了低纬度海区可能对全球气候变化有驱动作用[11]。且越来越多的研究表明, 在更长时间尺度的冰期-间冰期旋回中, 热带太平洋的海气系统同样存在着类似现代ENSO过程的变化[8, 12~18]。更重要的是热带海区的这种类ENSO式变化与古气候的波动存在一定的联系, 被看作热带大洋影响全球气候演变的重要途径之一[8, 19]。然而ENSO对全球古气候的影响可能不仅仅是通过改变热量和水汽的传输及其纬向交换那么简单[20~21], 有关低纬海区类ENSO过程在全球气候演化中所起作用的认识还存在着许多分歧, 且其是全球气候变化的“动因”还是“结果”也有待深入研究。

目前, 在全球变暖的背景下, 存在着“热带太平洋将更趋于El Niño态还是La Niña态的争论”[22], 解决该问题对于理解热带太平洋和相关地区的气候变化机制有十分重要的意义。上述争论的产生源于对两种状态形成机制的解释差异, 认为全球变暖状态下热带太平洋将更类似La Niña的依据是“海洋动态恒温器”理论[23], 而得出更类似El Niño状态的结论主要依据全球气候模型(GCMs)中“大气环流”模式的变化[24]。与此类似, 尽管古气候记录已经基本确定了ENSO在全新世的演化过程[25~28], 但在冰期旋回中, 热带海区温盐演变更类似“ El Niño ”还是“ La Niña ”状态也存在着截然不同的观点。从更长时间尺度上进一步探讨WPWP这一关键区域与现代ENSO相关的水文条件的变化至关重要。本文在分析已有的冰期旋回中热带太平洋古ENSO状态研究结果差异的基础上, 利用大洋钻探获取的高分辨率岩芯重建了近5次冰期旋回中WPWP核心区的SST演化历史, 计算了450 ka以来赤道东-西太平洋的温度梯度变化, 并结合热带西太平洋其他SST重建结果与东太平洋的记录对比, 试图揭示冰期旋回中冷暖期与类ENSO状态的对应关系。

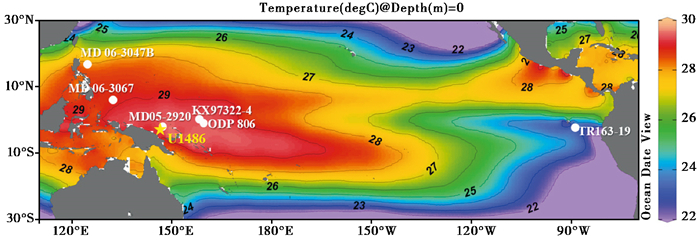

1 材料和方法IODP363航次U1486站位位于西太平洋马努斯海盆(02°22.34′S, 144°36.08′E;水深1332 m;图 1), 距巴布亚新几内亚塞皮克河河口约150 km。构造上该区属于澳洲板块北移之后与太平洋板块的汇聚区域, 澳洲和太平洋板块的碰撞造成了复杂的板块边界和内部微板块的旋转[29]。U1486站位处于该复杂构造体系中较为稳定的北俾斯麦微陆块的东南部[30], 该区域处于WPWP核心区, 年均SST约为28 ℃[31], 年际盐度变化范围为34.0~34.5 psu[32~34], 混合层深度大约位于50~100 m[33]。U1486站位共钻孔4次, 长211.2 m, 本研究选取U1486B、U1486C和U1486D这3个钻孔整合而成的岩芯上部0~31 m的沉积物为研究材料。所取得的沉积物岩性均一, 主要为灰白色富含有孔虫的超微化石软泥, 未见火山灰层和生物扰动痕迹。以10 cm间隔取样, 共获得样品335份, 用以浮游有孔虫氧同位素和Mg/Ca比分析, 样品的时间分辨率约为1.2 ka。另外, 对岩芯顶部0~11 m以5 cm间隔加密取样进行了Mg/Ca分析。

|

图 1

热带太平洋年均SST及U1486和文中涉及的其他岩芯站位

(KX97322-4[10]、ODP806[15]、MD05-2920[35]、MD06-3067[36]、TR163-19[15, 37]和MD06-3047B[38]) SST及底图数据来源于海洋数据视图软件(Ocean Data View, 简称ODV)(http://odv.awi.de), 图中等温线单位为摄氏度(℃) Fig. 1 Mean annual SST distribution in the tropical Pacific Ocean and sites of core U1486 and other cores in context(KX97322-4[10], ODP806[15], MD05-2920[35], MD06-3067[36], TR163-19[15, 37] and MD06-3047B[38]). The base map and SST data are from Ocean Data View(ODV, http://odv.awi.de), unit of the isotherm in this figure is Celsius(℃) |

样品前处理及氧同位素和Mg/Ca比值的测试工作均在中国科学院海洋地质与环境重点实验室进行。采用传统的浮游有孔虫样品处理方法, 每个层位取适量样品, 在50 ℃条件下烘干、称重后, 加入适量蒸馏水和3 %的双氧水(H2O2)溶液浸泡1~2 d, 待样品充分分散后用孔径63 μm标准筛冲洗样品, 收集大于63 μm的组分置于烘箱中在50 ℃的温度下烘干24 h后称重、保存以供分析。从每份样品的250~355 μm粒径范围中挑选完整洁净的浮游有孔虫Trilobatus sacculifer壳体40枚, 其中15枚用于氧同位素分析, 25枚用于Mg/Ca分析。

用于氧同位素测试的有孔虫壳体在显微镜下压碎后经3 %的过氧化氢溶液浸泡0.5 h, 然后加入少量丙酮超声30 s, 去除上清液后烘干。测试所用仪器为GV Iso Prime质谱仪, 分析精度高于0.06 ‰ (1σ), 通过NBS18标准校正为PDB标准。

由于镜检发现该岩芯中浮游有孔虫壳体较为洁净, 因此采用不含还原步骤的清洗方案处理用于Mg/Ca分析的浮游有孔虫壳体[39], 包括去粘土、去有机质、去杂质、转移、淋洗和溶样6个步骤, 测试在Thermo iCAP 6300 Radial型电感耦合等离子发射光谱仪上进行, 标样和重复样测量结果显示分析相对标准偏差为0.49 %。Hollstein等[40]在热带西太平洋海区利用沉积物样品和现代温盐深(conductivity, temperature, and depth, 简称CTD)数据对已有的Mg/Ca-SST经验公式进行了修正, 针对浮游有孔虫T.sacculifer建立了经验公式Mg/Ca=0.24exp0.097×T, 本文采用此公式将Mg/Ca比值换算为表层海水温度。

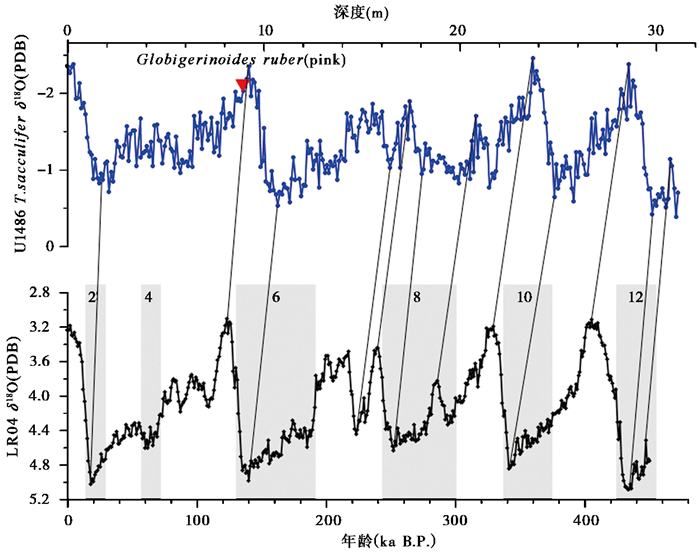

2 结果 2.1 年龄模式U1486岩芯上部31 m的年龄模式主要基于浮游有孔虫T.sacculifer的δ18O与LR04标准氧同位素曲线对比[41], 利用12个年龄控制点(表 1)并以粉红色Globigerinoides ruber末现面(120 ka)作为参照点[42~43]建立(图 2), U1486岩芯中粉红色G.ruber末现面(Last Appearance Datum, 简称LAD)的整合深度为8.834~8.934 m。

| 表 1 IODP363 U1486年龄控制点 Table 1 Age control points of IODP363 U1486 |

|

图 2 U1486岩芯年龄模式 LR04标准氧同位素曲线据Lisiecki和Raymo(2005)[43], 红色三角为粉红色G.ruber末现面(LAD), 数字代表海洋氧同位素阶段(MIS) Fig. 2 The age model of core U1486. The benthic stack LR04 is based on Lisiecki and Raymo(2005)[43], red triangle is the last appearance datum(LAD)of G.ruber(pink), and numbers represent Marine Isotope Stage(MIS) |

采用线性插值的方法得到其余层位的年龄, 结果显示U1486岩芯上部31 m保存了海洋氧同位素(Marine Isotope Stage, 简称MIS)12期以来的沉积记录, 时间跨度约450 ka。过去450 ka以来T.sacculifer的δ18O变化显示了明显的冰期-间冰期旋回, 其值变化幅度在-2.46 ‰到-0.39 ‰之间, 最高值出现在MIS 12, 最低值出现在MIS 9。

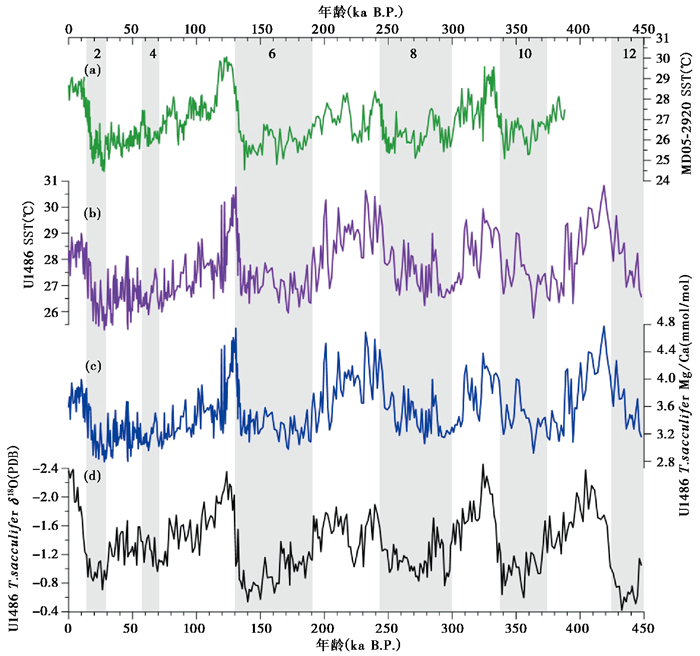

2.2 T.sacculifer Mg/Ca比和表层海水温度450 ka以来该海区浮游有孔虫T.sacculifer的Mg/Ca值在2.79~4.77 mmol/mol之间变化(图 3c)。岩芯顶部重建的SST为27.9 ℃, 与现代热带西太平洋T.sacculifer生活水深0~50 m[44]处的平均温度28.67±0.24 ℃较接近[31]。T.sacculifer的Mg/Ca温度波动范围为25.3~30.8 ℃, 与其δ18O基本呈现同步变化(图 3b和3d), 也显示了明显的冰期-间冰期旋回特征。其中, 温度最小值25.3 ℃出现在MIS 2(约27.8 ka)。末次冰盛期(Last Glacial Maximum, 简称LGM, 23~19 ka)时温度最低值为26.1 ℃, 比晚全新世(2~0 ka)低近2 ℃, 与邻近MD05-2920站位(图 3a)的记录相当[35]。U1486岩芯记录中SST最高值约30.8 ℃出现在MIS 11期的418.7 ka左右。前人的研究表明MIS 11是较强的一个暖期, 副极地地区和北大西洋的研究均发现了这一高温现象[45~46]。MIS 5e期SST比全新世高约1 ℃, 与南海ODP1145岩芯浮游有孔虫Mg/Ca-SST记录的温差幅度相当[47]。

|

图 3 MD05-2920岩芯Mg/Ca-SST[35] (a)及U1486岩芯T.sacculifer SST (b)、Mg/Ca (c)和δ18O (d)记录 数字代表氧同位素分期(MIS) Fig. 3 SST records of Core MD05-2920[35](a)and the SST (b), Mg/Ca (c), δ18O(d)records of core U1486(T.sacculifer). Numbers represent MIS |

研究结果表明, 在近5次冰期旋回中, 每一个冰消期均对应了一次SST的快速升高, 其中以Termination Ⅱ(MIS 6/5)升温最为迅速, 其在约3.8 ka的时间里升高了约3.9 ℃, 平均约1 ℃/ka;Terminatioin Ⅰ(MIS 2/1)、Ⅲ(MIS 8/7)和Ⅴ(MIS 12/11)升温幅度和速度大致相近, 为约4 ℃, 速度均为约0.2 ℃/ka;Termination Ⅳ(MIS 10/9)温度变化幅度最小, 为约3 ℃。此外每个冰消期在升温过程中都存在不同程度的温度波动(图 3b)。

3 讨论 3.1 热带太平洋冰期的ENSO状态针对近几十万年来的冰期, 特别是LGM时期热带太平洋的ENSO状态已有大量研究[17, 48~51], 然而该问题目前仍然没有明确的结论, 存在两种矛盾的认识。西太平洋MD06-3067岩芯中海水剩余氧同位素(δ18Osw)和颗石藻(Coccolithophore)种属组成反演的过去160 ka棉兰老流(Mindanao Current)的变化显示末次冰期呈现类La Niña态[36]。同时, 颗石藻丰度重建的初级生产力变化也显示, 过去250 ka期间, 印-太海区在冰期呈现出高生产力的特征, 其气候更类似于La Niña状态[52]。用浮游有孔虫转换函数重建了热带太平洋的温跃层深度的结果显示[53] LGM期间东-西太平洋温跃层斜率、纬向风力以及温度梯度都变大, Walker环流加强, 热带太平洋处于类似La Niña的状态。此外, 赤道东-西太平洋ODP806和TR163-19岩芯中, 浮游有孔虫G.ruber的Mg/Ca温度记录显示, 过去400 ka来东-西太平洋温度差在冰期(MIS 2、MIS 6和MIS 8)要比现在平均高约1 ℃, 在温暖的间冰期则低约1 ℃(MIS 5.5、MIS 7.5和MIS 9.3), 指示冰期热带太平洋更类似于La Niña状态[15]。且东太平洋冷舌(Eastern Pacific Cold Tongue, 简称EPCT)区ODP 1239和MD02-2529岩芯中U37K′反演的温度也指示, 过去500 ka的冰期, 东-西太平洋温度差较大且热带东太平洋南北温度梯度增加, 表明冷舌的活动性增强, 冰期呈现出类似La Niña的状态[54]。

与上述主要依据热带东-西太平洋纬向和EPCT区经向温度梯度得出的近几十万年来冰期或LGM时期热带太平洋更多的偏向于La Niña状态完全相反, 处于WPWP西部边缘MD98-2181岩芯中浮游有孔虫δ18O和Mg/Ca温度重建的末次冰期时的盐度要显著高于现代, 指示区域处于类El Niño的状态[17]。同时, WPWP北部3cBx岩芯中不同深度7个浮游有孔虫种的Mg/Ca温度变化指示, 约25 ka时温跃层比表层海水多降温1~2 ℃, 说明LGM时期温跃层变浅;且该时期表层海水盐度降低, 说明海水蒸发变弱, Walker环流减弱, 与温跃层变浅相吻合, 处于类El Niño状态[49]。与西太平洋相对应, 在EPCT处V21-30岩芯中浮游有孔虫Mg/Ca温度显示, LGM时东太冷舌区的降温只有1.2 ℃, 南北温度梯度变小, 此时Hadley环流和Walker环流减弱、ITCZ南移, 呈现出类El Niño状态[48, 51], 这也与婆罗洲石笋氧同位素指示的LGM时婆罗洲降水较少记录[21]吻合。除此之外, 热带东太平洋其余8个岩芯(RC13-140、TR163-19、V19-27、V21-29、V21-30、RC8-102、RC11-238和V19-28)中游有孔虫Mg/Ca温度显示LGM时其经向梯度降低, 表明冷舌区ITCZ锋面的活动性变弱, ITCZ南移, 热带东太平洋东南信风减弱, 与现代El Niño状态类似[55]。

分析上述已有工作可以发现, 大多数针对末次冰期和LGM时期的研究中, 依据西太平洋盐度(降水)的研究都得出了末次冰期或LGM时期热带太平洋处于类El Niño的状态[17, 48, 51]。所有通过赤道东-西太平洋温度梯度变化指示ENSO状态的工作都显示近几十万年的冰期更类似于La Niña态[10, 15, 54]。而基于EPCT经向温度梯度变化[54~55]的研究却同时得到了两种相左的认识。依据浮游有孔虫转换函数反演的古温度[50, 53]得出的末次冰期和LGM更类似于La Niña状态的结论, 可能由于转换函数方法存在问题可信度不高。而热带太平洋的海温也很可能超过U37K′反演古温度有效适用范围[51]。通过浮游有孔虫δ18O, 结合其Mg/Ca温度重建的表层海水剩余氧同位素, 在指示区域盐度继而反演区域降水时也可能存在较大的不确定性。但导致上述研究出现显著差异的原因可能更多的是在于ENSO现象对热带东-西太平洋和相邻大陆影响的复杂性, 单个站位的结果可能无法代表整个热带区域的变化[56], 且某些站位处的海洋气候条件很可能受ENSO变化的影响较小[57]。但更主要的因素可能在于, 用温跃层深度、局地降水、东-西太平洋纬向和EPCT经向温度梯度这些指标来表征ENSO状态时存在时间上的不同步性, 即这些表征参数在一次ENSO事件中可能并不是同步变异的。

从上述已有研究的时间尺度来看, 大多数都限于末次冰期, 跨越几个冰期旋回的记录较少, 而更长时间尺度下ENSO演化的气候背景可能存在差异[56]。另外, 已有记录大都是集中于对单点或单个区域的研究[17, 48~49, 54], 对热带东-西太平洋的对比研究相对较少。因此, 要准确评价近几十万年来冰期旋回中热带太平洋海洋大气过程的状态有必要利用高分辨的钻孔进行更长时间跨度上热带东-西太平洋的对比分析。

3.2 冰期旋回中冷暖期的东-西太平洋温度梯度从现代ENSO过程来看, 暖相位(El Niño)期间, 西太平洋暖水在赤道西风和东亚季风的作用下向东运移[14], 抑制了太平洋中、东部海盆的冷水上涌[2], 从而导致热带东-西太平洋的温度梯度减小, 并伴有东太平洋上升流和东向信风的减弱以及西太平洋降水的增加[58], 而冷相位(La Niña)时则刚好相反。因此, 东-西太平洋纬向温度梯度是ENSO状态的一个良好指标[15, 59]。

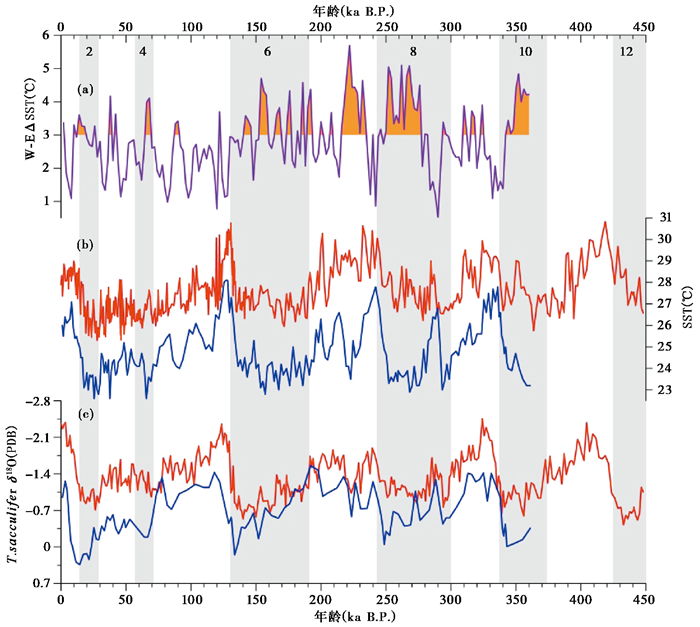

U1486岩芯中T.sacculifer Mg/Ca重建的SST与邻近的MD05-2920岩芯中G.ruber Mg/Ca的表层海水温度记录[35]相当一致, 都显示了系统的冰期-间冰期旋回(图 3a和3b)。TR163-19站位位于东太平洋的科科斯海岭, 该区温跃层较浅, 混合层深度仅为约20 m, 为典型的东太平洋冷舌水文条件[15]。对比U1486和TR163-19岩芯的δ18O记录可以发现, 近350 ka以来WPWP的浮游有孔虫δ18O始终较EPCT处偏负, 且在MIS 2、MIS 4、MIS 8和MIS 10等冰期二者间的差值远大于相邻的间冰期(图 4c), 表明相较于间冰期, 冰期时东-西太平洋的水文条件差异更大。同时, 两者的SST变化也显示了类似的特征, 近几个冰期旋回中WPWP的SST始终高于EPCT(图 4b), 冰期东-西太平洋温差明显大于间冰期;其中, 冰期两站位处的平均温度差为约3.1 ℃, 而间冰期为约2.5 ℃, MIS 2、MIS 6、MIS 8和MIS 10在这两个站位间的温差均大于现代两处的平均温度差(约3 ℃)[31](图 4a), 这说明冰期赤道信风强度加强, 热带太平洋的水文类似于现在气候条件下的La Niña状态, 这也与已有的部分古气候重建及模拟结果一致[15, 50, 53~54, 60]。

|

图 4

WPWP区U1486岩芯与EPCT处TR163-19岩芯[15, 37]的δ18O和SST记录对比

(a)U1486与TR163-19岩芯的SST差值(ΔSST), 计算时2 ka为步长进行线性插值;(b)两岩芯的SST记录;(c)两岩芯的T.sacculiferδ18O记录 红色线条为U1486岩芯数据, 蓝色线条为TR163-19岩芯数据;数字代表氧同位素分期(MIS) Fig. 4 Comparison of the records of δ18O and SST from core U1486 in WPWP and core TR163-19[15, 37] in EPCT. (a)SST gradient of U1486 and TR163-19(ΔSST), the difference is calculated by linear interpolation with a window of 2 ka; (b)SST records of core U1486(red)and TR163-19(blue); (c) T.sacculiferδ18O records of core U1486(red)and TR163-19(blue). Numbers represent MIS |

太平洋表层和温跃层海水温度的变化受控于ENSO过程以及Walker环流的相关变化[61], 而其温度的差值能够反映温跃层深度的变化。当表层与温跃层温度差变大时, 意味着温跃层深度变浅, 差值变小时则指示温跃层深度变深[62~63]。El Niño发生期间WPWP温跃层变浅, 而La Niña态时温跃层变深[49], 赤道西太平洋温跃层深度也是ENSO状态的一个良好指标。热带西太平洋MD06-3067站位(图 1)处的表层和温跃层温度显示MIS 2、MIS 4期间表层与温跃层温度差减小[36], 位于暖池核心区表层和温跃层的温度反演研究也显示出类似特征[61], 表明冰期温跃层深度变深, 这一时段西太平洋类La Niña气候态占主导地位。虽然有一些研究认为冰期时WPWP温跃层出现变浅的现象[49, 64~65], 但替代指标重建和模拟结果表明LGM时WPWP温跃层呈现出北浅南深的“跷跷板模式”[61], 且冰期WPWP的位置和范围的不确定性[10], 都可能导致不同指标重建结果的差异。

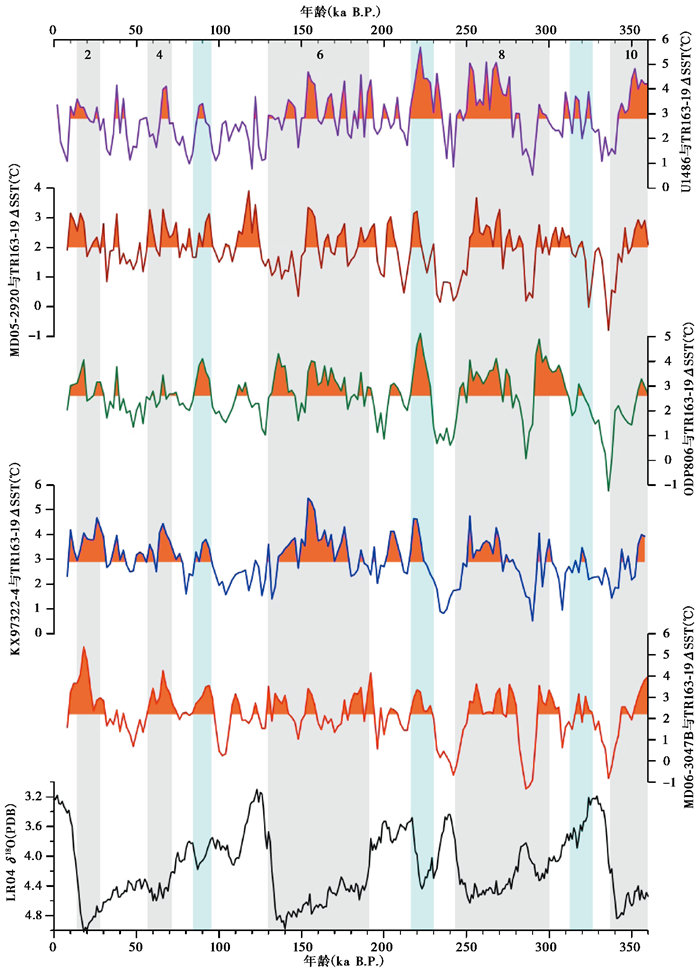

为了进一步分析冰期-间冰期热带东-西太平洋的表层海水温度梯度, 本文搜集整理了WPWP核心区ODP806[15]、KX97322-4[10]、核心区边缘MD05-2920[35]以及暖池边缘区MD06-3047B[38]岩芯的SST记录, 并分别与EPCT区TR163-19岩芯的记录[15]进行对比(图 5)。结果显示350 ka以来热带西太平洋不同区域与EPCT上层海水温度差值都呈现大致相同的变化模式, 即冰期温差大于间冰期, 从东-西太平洋温度梯度的角度指示冰期更类似于La Niña状态。然而几乎在每次冰期内部, 该温度梯度都存在着显著波动, 说明在较长时间尺度上热带太平洋的类ENSO状态是不稳定的。

|

图 5 U1486及WPWP其他站位(MD05-2920[35]、ODP806[15]、KX97322-4[10]和MD06-3047B[38])与EPCT处TR163-19站位[15]的ΔSST记录对比 黑色曲线为LR04标准曲线[43];浅蓝色条带代表间冰期冰阶, 数字代表氧同位素分期(MIS), 计算ΔSST时以2 ka为步长进行线性插值 Fig. 5 Comparison of ΔSST between other sites(MD05-2920[35], ODP806[15], KX97322-4[10]and MD06-3047B[38])in WPWP and site TR163-19[15]. The black curve is benthic stack LR04[43]; The light blue bars represent stadials, numbers represent MIS, ΔSST is calculated by linear interpolation with a window of 2 ka |

不仅冰期如此, 几次典型的间冰期中的冰阶也都显示了东-西太平洋温度差较大的特征。MIS 5b时期, ODP806、KX97322-4、U1486、MD05-2920、MD06-3047B与TR163-19站位处的最大温度差范围为3~4 ℃;MIS 7d时期, 其最大温度差范围为3~5 ℃(图 5)。这两次冰阶时期均明显显示出了类似La Niña的状态, 而这种特征在MIS 9b期也有表现, 说明在间冰期中气候偏冷的冰阶热带太平洋海洋条件也更趋于La Niña状态。此外, 过去360 ka以来暖池核心区ODP806、KX97322-4站位与东太平洋TR163-19站位处的平均温差分别为约2.6 ℃和约2.9 ℃(图 5), 而以MD06-3047B岩芯为代表的暖池边缘区与东太的温度梯度仅为约2.2 ℃(图 5), 这种从暖池核心区向边缘区东-西太平洋温度差逐渐变小的特征, 很好地指示了暖池温度从核心区向外逐渐降低的特征(图 1)。而暖池核心区边缘MD05-2920岩芯与东太平洋的温度差(约2 ℃)却低于暖池边缘(图 5), 其原因可能是该记录采用的Mg/Ca温度经验公式[66]造成的其反演的温度偏低。而在几次冰消期(MIS 6/5、MIS 8/7、MIS 10/9)东-西太平洋温度差减小(图 5), 说明此时纬向Walker环流减弱, 快速变暖时期更偏向于El Niño状态。

由此可见, 从赤道东-西太平洋温度梯度来看, 近几十万年来的冰期旋回中不论是冰期还是间冰期中偏冷的冰阶热带太平洋都处于一种更类似于La Niña的状态, 而气候变暖的冰消期更偏向于El Niño状态。现代模拟研究显示当地表温度上升1 ℃时, 对流层下层的水蒸气含量增加约7 % [67~68], 而降水的增加却较缓慢, 大约为2 % [69~70]。这种差异导致边界层与对流层中层之间的质量交换减少, 同时对流的质量通量下降[24]。受这种大气水文循环变化的驱使, 热带大气环流在全球变暖时减弱[24, 71], 特别表现为太平洋Walker环流和赤道东风带的减弱, 从而导致了东-西太平洋SST梯度减小[22], 热带太平洋的水文条件趋向于El Niño状态, 这也得到了南方涛动指数和热带太平洋近2000年来的水文记录支持[72]。该机制可能是近几十万年来偏冷的冰期和冰阶热带太平洋表现为更类似于La Niña状态的原因。

4 结论已有的对冰期旋回中热带太平洋古ENSO状态的研究大多数局限于末次冰期和LGM时期, 其中基于WPWP温跃层深度和EPCT经向温度梯度变化获得的结果存在明显的差异。而据热带西太平洋盐度和东-西太平洋温度梯度表征古ENSO状态的工作都得到了冰期时热带太平洋更类似La Niña状态的结论。WPWP核心区U1486与EPCT区TR163-19岩芯的古温度记录对比显示, 过去450 ka来冰期时两站位间表层海水的平均温度差明显大于间冰期, 其中冰期约为3.1 ℃, 而间冰期约为2.5 ℃, 冰期(MIS 2、MIS 6、MIS 8和MIS 10)东-西太平洋的ΔSST均大于现代两处的平均温度差值;同时, 热带西太平洋其他温度重建结果与EPCT区域SST记录的对比也呈现了相同变化特征;且间冰期中的典型冰阶(MIS 5b、MIS 7d)东-西太平洋的温度梯度也要大于间冰阶。而几次快速变暖的冰消期(MIS 6/5、MIS 8/7和MIS 10/9)东-西太平洋温度梯度则明显减小。赤道东-西太平洋温度梯度的变化指示, 近几十万年来的冰期旋回中偏冷的冰期和间冰期的冰阶热带太平洋表现为更类似于La Niña状态, 冰消期则更偏向于El Niño状态, 但几乎在每次冰期内部, 热带东-西太平洋的温度梯度都存在明显的波动, 显示了较长时间尺度上热带太平洋类ENSO状态的不稳定性。气候变暖时, 对流层下层水汽含量的增加快于降雨量的增加, 使得边界层与对流层中层之间的质量交换减少、热带太平洋Walker环流减弱, 从而导致了东-西太平洋SST梯度减小, 热带太平洋的水文条件趋向于El Niño状态。

致谢: IODP 363航次的所有船上工作人员为本研究提供了宝贵样品;中国科学院海洋研究所海洋地质与环境实验室丁亚梅和姜明玉两位老师在本文样品测试过程中提供了大量指导和帮助;审稿专家和编辑老师在文章修改过程中对本文提出了富有建设性的修改意见, 在此表示衷心感谢。

| [1] |

Yan Xiaohai, Ho Chungru, Zheng Quanan, et al. Temperature and size variabilities of the Western Pacific Warm Pool[J]. Science, 1992, 258(5088): 1643-1645. DOI:10.1126/science.258.5088.1643 |

| [2] |

Webster P J. The role of hydrological processes in ocean-atmosphere interactions[J]. Reviews of Geophysics, 1994, 32(4): 427-476. DOI:10.1029/94RG01873 |

| [3] |

Rasmusson E M. El Niño and variations in climate:Large-scale interactions between the ocean and the atmosphere over the tropical Pacific can dramatically affect weather patterns around the world[J]. American Scientist, 1985, 73(2): 168-177. |

| [4] |

Ropelewski C F, Halpert M S. Global and regional scale precipitation patterns associated with the El Niño/Southern Oscillation[J]. Monthly Weather Review, 1987, 115(8): 1606-1626. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1987)115<1606:GARSPP>2.0.CO;2 |

| [5] |

李晓惠, 徐峰, 陈虹颖, 等. 1980-2016年西太平洋暖池与ENSO循环过程的相关分析[J]. 海洋气象学报, 2017, 37(3): 85-94. Li Xiaohui, Xu Feng, Chen Hongying, et al. Correlation analysis of the cycle process between the Western Pacific Warm Pool and ENSO during 1980-2016[J]. Journal of Marine Meteorology, 2017, 37(3): 85-94. |

| [6] |

Pierrehumbert R T. Climate change and the tropical Pacific:The sleeping dragon wakes[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2000, 97(4): 1355-1358. DOI:10.1073/pnas.97.4.1355 |

| [7] |

Rosenthal Y, Oppo D W, Linsley B K. The amplitude and phasing of climate change during the last deglaciation in the Sulu Sea, Western Equatorial Pacific[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2003, 30(8): 1428. |

| [8] |

Visser K, Thunell R, Stott L. Magnitude and timing of temperature change in the Indo-Pacific warm pool during deglaciation[J]. Nature, 2003, 421(6919): 152-155. DOI:10.1038/nature01297 |

| [9] |

Stott L, Timmermann A, Thunell R. Southern hemisphere and deep-sea warming led deglacial atmospheric CO2 rise and tropical warming[J]. Science, 2007, 318(5849): 435-438. DOI:10.1126/science.1143791 |

| [10] |

Zhang Shuai, Li Tiegang, Chang Fengming, et al. Correspondence between the ENSO-like state and glacial-interglacial condition during the past 360 kyr[J]. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 2017, 35(5): 1018-1031. DOI:10.1007/s00343-017-6082-9 |

| [11] |

汪品先. 低纬过程的轨道驱动[J]. 第四纪研究, 2006, 26(5): 694-701. Wang Pinxian. Orbital forcing of the low-latitude processes[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2006, 26(5): 694-701. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7410.2006.05.003 |

| [12] |

张帅, 李铁刚, 常凤鸣, 等. MIS 6期以来热带西太平洋降雨与ITCZ的关系[J]. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(2): 390-400. Zhang Shuai, Li Tiegang, Chang Fengming, et al. The relationship between the tropical Pacific precipitaton and the ITCZ variation since MIS 6[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(5): 390-400. |

| [13] |

贾奇, 李铁刚, 熊志方, 等. 70万年来西太平洋暖池北缘有孔虫氧碳同位素特征及其古海洋学意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(2): 401-410. Jia Qi, Li Tiegang, Xiong Zhifang, et al. Foraminiferal carbon and oxygen isotope composition characteristics and their paleoceanographic implications in the north margin of the Western Pacific Warm Pool[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(2): 401-410. |

| [14] |

Cane M A. A role for the Tropical Pacific[J]. Science, 1998, 282(5386): 59-61. DOI:10.1126/science.282.5386.59 |

| [15] |

Lea D W, Pak D K, Spero H J. Climate impact of Late Quaternary equatorial Pacific sea surface temperature variations[J]. Science, 2000, 289(5485): 1719-1724. DOI:10.1126/science.289.5485.1719 |

| [16] |

Tudhope A W, Chilcott C P, Mcculloch M T, et al. Variability in the El Niño-Southern Oscillation through a glacial-interglacial cycle[J]. Science, 2001, 291(5508): 1511-1517. DOI:10.1126/science.1057969 |

| [17] |

Stott L, Poulsen C, Lund S, et al. Super ENSO and global climate oscillations at millennial time scales[J]. Science, 2002, 297(5579): 222-226. DOI:10.1126/science.1071627 |

| [18] |

李铁刚, 赵京涛, 孙荣涛, 等. 250 ka B. P.以来西太平洋暖池中心区Ontong Java海台古生产力演化[J]. 第四纪研究, 2008, 28(3): 447-457. Li Tiegang, Zhao Jingtao, Sun Rongtao, et al. Paleoproductivity evolution in the Ontong Java Plateau-Center of the Western Pacific Warm Pool during the last 250 ka[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2008, 28(3): 447-457. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7410.2008.03.009 |

| [19] |

Sarnthein M, Grootes P M, Holbourn A, et al. Tropical warming in the Timor Sea led deglacial Antarctic warming and atmospheric CO2 rise by more than 500 yr[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2011, 302(3-4): 337-348. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2010.12.021 |

| [20] |

Schmittner A, Appenzeller C, Stocker T F. Enhanced Atlantic freshwater export during El Niño[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2000, 27(8): 1163-1166. DOI:10.1029/1999GL011048 |

| [21] |

Partin J W, Cobb K M, Adkins J F, et al. Millennial-scale trends in West Pacific Warm Pool hydrology since the Last Glacial Maximum[J]. Nature, 2007, 449(7161): 452-455. DOI:10.1038/nature06164 |

| [22] |

Vecchi G A, Clement A, Soden B J. Examining the tropical Pacific's response to global warming[J]. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 2008, 89(9): 81-83. |

| [23] |

Clement A C, Seager R, Cane M A, et al. An ocean dynamical thermostat[J]. Journal of Climate, 1996, 9(9): 2190-2196. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(1996)009<2190:AODT>2.0.CO;2 |

| [24] |

Held I M, Soden B J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming[J]. Journal of Climate, 2006, 19(21): 5686-5699. DOI:10.1175/JCLI3990.1 |

| [25] |

Gagan M K, Hendy E J, Haberle S G, et al. Post-glacial evolution of the Indo-Pacific Warm Pool and El Niño-Southern Oscillation[J]. Quaternary International, 2004, 118-119: 127-143. DOI:10.1016/S1040-6182(03)00134-4 |

| [26] |

Driscoll R, Elliot M, Russon T, et al. ENSO reconstructions over the past 60 ka using giant clams(Tridacna sp.) from Papua New Guinea[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2014, 41(19): 6819-6825. DOI:10.1002/2014GL061446 |

| [27] |

王玥铭, 窦衍光, 徐景平, 等. 16 ka以来冲绳海槽中南部有机质来源及其对上升流演变的指示[J]. 第四纪研究, 2018, 38(3): 769-781. Wang Yueming, Dou Yanguang, Xu Jingping, et al. Organic matter source in the middle Southern Okinawa Trough and its indication to upwelling evolution since 16 ka[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2018, 38(3): 769-781. |

| [28] |

黄冉, 陈朝军, 李廷勇, 等. 基于石笋记录的晚全新世太平洋东西两岸季风区气候事件对比研究[J]. 第四纪研究, 2019, 39(3): 742-754. Huang Ran, Chen Chaojun, Li Tingyong, et al. Comparison of climatic events in the Late Holocene, based on stalagmite records from monsoon regions near by the east and west Pacific[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2019, 39(3): 742-754. |

| [29] |

Baldwin S L, Fitzgerald P G, Webb L E. Tectonics of the New Guinea region[J]. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 2012, 40(1): 495-520. DOI:10.1146/annurev-earth-040809-152540 |

| [30] |

Taylor B. Bismarck Sea:Evolution of a back-arc basin[J]. Geology, 1979, 7(4): 171-174. DOI:10.1130/0091-7613(1979)7<171:BSEOAB>2.0.CO;2 |

| [31] |

Schlitzer R. Ocean Data View 4[DB]. 2015. http://odv.awi.de.

|

| [32] |

Carton J A, Giese B S. A reanalysis of ocean climate using Simple Ocean Data Assimilation(SODA)[J]. Monthly Weather Review, 2008, 136(8): 2999-3017. DOI:10.1175/2007MWR1978.1 |

| [33] |

Locarnini R A, Mishonov A V, Antonov J I, et al. World Ocean Atlas 2013. Volume 1, Temperature, 2013[DB]. https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/indprod.html.

|

| [34] |

Zweng M M, Reagan J R, Antonov J I, et al. World Ocean Atlas 2013. Volume 2, Salinity, 2013[DB]. https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/indprod.html.

|

| [35] |

Tachikawa K, Timmermann A, Vidal L, et al. CO2 radiative forcing and Intertropical Convergence Zone influences on Western Pacific Warm Pool climate over the past 400 ka[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2014, 86: 24-34. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.12.018 |

| [36] |

Bolliet T, Holbourn A, Kuhnt W, et al. Mindanao Dome variability over the last 160 kyr:Episodic glacial cooling of the West Pacific Warm Pool[J]. Paleoceanography, 2011, 26(1): PA1208. |

| [37] |

Spero H J, Mielke K M, Kalve E M, et al. Multispecies approach to reconstructing eastern equatorial Pacific thermocline hydrography during the past 360 kyr[J]. Paleoceanography, 2003, 18(1): 1022. |

| [38] |

Jia Qi, Li Tiegang, Xiong Zhifang, et al. Hydrological variability in the western tropical Pacific over the past 700 kyr and its linkage to Northern Hemisphere climatic change[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2017, 493: 44-54. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.12.039 |

| [39] |

Barker S, Greaves M, Elderfield H. A study of cleaning procedures used for foraminiferal Mg/Ca paleothermometry[J]. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 2003, 4(9): 8407. |

| [40] |

Hollstein M, Mohtadi M, Rosenthal Y, et al. Stable oxygen isotopes and Mg/Ca in planktic foraminifera from modern surface sediments of the Western Pacific Warm Pool:Implications for thermocline reconstructions[J]. Paleoceanography, 2017, 32(11): 1174-1194. DOI:10.1002/2017PA003122 |

| [41] |

Lisiecki L E, Raymo M E, Curry W B. Atlantic overturning responses to Late Pleistocene climate forcings[J]. Nature, 2008, 456(7218): 85. DOI:10.1038/nature07425 |

| [42] |

Thompson P R, Bé A W H, Duplessy J-C, et al. Disappearance of pink-pigmented Globigerinoides ruber at 120, 000 yr BP in the Indian and Pacific Oceans[J]. Nature, 1979, 280(5723): 554-558. DOI:10.1038/280554a0 |

| [43] |

Lisiecki L E, Raymo M E. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records[J]. Paleoceanography, 2005, 20(1): PA1003. |

| [44] |

万随, 翦知湣, 成鑫荣. 赤道西太平洋冬季浮游有孔虫分布与壳体同位素特征[J]. 第四纪研究, 2011, 31(2): 284-291. Wan Sui, Jian Zhimin, Cheng Xinrong. Distribution of winter living planktonic foraminifers and characteristics to their shell's stable isotopic in the western equatorial Pacific[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2011, 31(2): 284-291. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-7410.2011.02.10 |

| [45] |

Hays J D, Imbrie J, Shackleton N J. Variations in the Earth's orbit:Pacemaker of the ice ages[J]. Science, 1976, 194(4270): 1121-1132. DOI:10.1126/science.194.4270.1121 |

| [46] |

Mcmanus J F, Oppo D W, Cullen J L. A 0.5-million-year record of millennial-scale climate variability in the North Atlantic[J]. Science, 1999, 283(5404): 971-975. DOI:10.1126/science.283.5404.971 |

| [47] |

Oppo D W, Sun Y. Amplitude and timing of sea-surface temperature change in the northern South China Sea:Dynamic link to the East Asian monsoon[J]. Geology, 2005, 33(10): 785-788. DOI:10.1130/G21867.1 |

| [48] |

Koutavas A, Lynch-Stieglitz J, Marchitto T M Jr, et al. El Niño-like pattern in ice age tropical Pacific sea surface temperature[J]. Science, 2002, 297(5579): 226-230. DOI:10.1126/science.1072376 |

| [49] |

Sagawa T, Yokoyama Y, Ikehara M, et al. Shoaling of the western equatorial Pacific thermocline during the Last Glacial Maximum inferred from multispecies temperature reconstruction of planktonic foraminifera[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2012, 346-347: 120-129. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.06.002 |

| [50] |

Martínez I, Keigwin L, Barrows T T, et al. La Niña-like conditions in the eastern equatorial Pacific and a stronger Choco jet in the northern Andes during the last glaciation[J]. Paleoceanography, 2003, 18(2): 1003. |

| [51] |

Koutavas A, Joanides S. El Niño-Southern Oscillation extrema in the Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum[J]. Paleoceanography, 2012, 27: PA4208. DOI:10.1029/2012PA002378 |

| [52] |

Beaufort L, Garidel-Thoron T D, Mix A C, et al. ENSO-like forcing on oceanic primary production during the Late Pleistocene[J]. Science, 2001, 293(5539): 2440-2444. DOI:10.1126/science.293.5539.2440 |

| [53] |

Andreasen D J, Ravelo A C. Tropical Pacific Ocean thermocline depth reconstructions for the Last Glacial Maximum[J]. Paleoceanography, 1997, 12(3): 395-413. DOI:10.1029/97PA00822 |

| [54] |

Rincón-Martínez D, Lamy F, Contreras S, et al. More humid interglacials in Ecuador during the past 500 kyr linked to latitudinal shifts of the equatorial front and the Intertropical Convergence Zone in the eastern tropical Pacific[J]. Paleoceanography, 2010, 25(2): PA2210. |

| [55] |

Koutavas A, Lynch-Stieglitz J. Glacial-interglacial dynamics of the eastern equatorial Pacific Cold Tongue-Intertropical Convergence Zone system reconstructed from oxygen isotope records[J]. Paleoceanography, 2003, 18(4): 1089. |

| [56] |

Rosenthal Y, Broccoli A J. In search of paleo-ENSO[J]. Science, 2004, 304(5668): 219-221. DOI:10.1126/science.1095435 |

| [57] |

Dannenmann S, Linsley B K, Oppo D W, et al. East Asian monsoon forcing of suborbital variability in the Sulu Sea during Marine Isotope Stage 3:Link to Northern Hemisphere climate[J]. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 2003, 4(1): 1-13. |

| [58] |

Brijker J M, Jung S J A, Ganssen G M, et al. ENSO related decadal scale climate variability from the Indo-Pacific Warm Pool[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2007, 253(1): 67-82. |

| [59] |

Jin F-F. Tropical Ocean-atmosphere interaction, the Pacific Cold Tongue, and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation[J]. Science, 1996, 274(5284): 76-78. DOI:10.1126/science.274.5284.76 |

| [60] |

Zhu J, Liu Z, Brady E, et al. Reduced ENSO variability at the LGM revealed by an isotope-enabled Earth system model[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2017, 44(13): 6984-6992. DOI:10.1002/2017GL073406 |

| [61] |

Hollstein M, Mohtadi M, Rosenthal Y, et al. Variations in Western Pacific Warm Pool surface and thermocline conditions over the past 110, 000 years:Forcing mechanisms and implications for the glacial Walker circulation[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2018, 201: 429-445. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.10.030 |

| [62] |

Xu J, Holbourn A, Kuhnt W, et al. Changes in the thermocline structure of the Indonesian outflow during Terminations Ⅰ and Ⅱ[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2008, 273(1-2): 152-162. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.06.029 |

| [63] |

Steinke S, Mohtadi M, Groeneveld J, et al. Reconstructing the southern South China Sea upper water column structure since the Last Glacial Maximum:Implications for the East Asian winter monsoon development[J]. Paleoceanography, 2010, 25(2): PA2219. |

| [64] |

Leech P J, Lynch-Stieglitz J, Zhang R. Western Pacific thermocline structure and the Pacific marine Intertropical Convergence Zone during the Last Glacial Maximum[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2013, 363: 133-143. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2012.12.026 |

| [65] |

Regoli F, De Garidel-Thoron T, Tachikawa K, et al. Progressive shoaling of the equatorial Pacific thermocline over the last eight glacial periods[J]. Paleoceanography, 2015, 30(5): 439-455. DOI:10.1002/2014PA002696 |

| [66] |

Anand P, Elderfield H, Conte M H. Calibration of Mg/Ca thermometry in planktonic foraminifera from a sediment trap time series[J]. Paleoceanography, 2003, 18(2): 1050. |

| [67] |

Soden B J, Jackson D L, Ramaswamy V, et al. The radiative signature of upper tropospheric moistening[J]. Science, 2005, 310(5749): 841-844. DOI:10.1126/science.1115602 |

| [68] |

Trenberth K E, Fasullo J, Smith L. Trends and variability in column-integrated atmospheric water vapor[J]. Climate Dynamics, 2005, 24(7-8): 741-758. DOI:10.1007/s00382-005-0017-4 |

| [69] |

Boer G J. Climate change and the regulation of the surface moisture and energy budgets[J]. Climate Dynamics, 1993, 8(5): 225-239. DOI:10.1007/BF00198617 |

| [70] |

Allen M R, Ingram W J. Constraints on future changes in climate and the hydrologic cycle[J]. Nature, 2002, 419(6903): 228-232. |

| [71] |

Vecchi G A, Soden B J, Wittenberg A T, et al. Weakening of tropical Pacific atmospheric circulation due to anthropogenic forcing[J]. Nature, 2006, 441(7089): 73-76. DOI:10.1038/nature04744 |

| [72] |

Yan Hong, Sun Liguang, Wang Yuhong, et al. A record of the Southern Oscillation Index for the past 2, 000 years from precipitation proxies[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2011, 4(9): 611-614. DOI:10.1038/ngeo1231 |

2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049;

3 Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, Shandong;

4 Laboratory for Marine Geology, Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology(Qingdao), Qingdao 266237, Shandong;

5 Key Laboratory of Marine Sedimentology and Environment Geology, First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Qingdao 266061, Shandong)

Abstract

As the strongest inter-annual climate anomaly in modern times, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation(ENSO)process has a significant impact on the global climate and marine hydrological conditions. On the long-term scale, the ENSO-like transition of thermal state in the tropical Pacific may also have played an important role in the paleoclimatic evolution. Most of the existing studies on the tropical ENSO-like state are, however, limited to the last glacial period, and there are many significant disagreements among these available results derived from different proxies.Site U1486, 211.2 m in length, was drilled within the Manus Basin, the central sector of the Western Pacific Warm Pool(WPWP), at 02°22.34'S, 144°36.08'E in 1332 m of water during the International Ocean Discovery Program(IODP)Expedition 363. The site is located ca. 150 km away from the Sepik River mouth in Papua New Guinea. The tectonic setting of this area was shaped by the oblique northward movement of the Australian plate as it rapidly converged with the Pacific plate. Site U1486 is situated in the North Bismarck microplate which is resulted from the tectonic movements.In this study, the upper 31 m core composite depth below seafloor(CCSF)of Site U1486, with lithology dominated by white foraminifera-rich nannofossil ooze, was used to reconstruct the sea surface temperature(SST)based on δ18O and Mg/Ca analyses of planktonic foraminifera Trilobatus sacculife, and thus to investigate the potential linkage between the warm/cold periods in the glacial/interglacial cycles and the tropical ENSO-like state in the WPWP since 450 ka. In more details, the age model was determined by 12 age tie points, derived from correlating the present δ18O curve with the standard LR04 stack as well as the last occurrence of Globigerinoides ruber(pink)with a well-known age(120 ka)in the west Pacific. In addition, the δ18O analysis was made on 335 subsamples, with sampling intervals of 10 cm and thus an average temporal resolution of 1.2 ka. Furthermore, a total of 455 subsamples were analyzed for the Mg/Ca ratio, with sampling intervals of 5-cm for the top 11 m and 10-cm for the rest section of the site.The results indicate that the SST in the WPWP since 450 ka ranged between 25.3 ℃ and 30.8 ℃, with minimum and maximum value occurred at ca. 27.8 ka and 418.7 ka, respectively. The minimum SST at the site during the Last Glacial Maximum(LGM, 23~19 ka)is nearly 2 ℃ lower than that during the Late Holocene(2~0 ka). By comparing the SST records derived from the cores located in the Western Pacific Warm Pool(WPWP)and the Eastern Pacific Cold Tongue(EPCT), it is found that the zonal temperature gradient of the tropical Pacific Ocean was more than 3 ℃, along with deeper thermocline in the WPWP, during the glacial periods. This is coincident with the SST records in other cores collected from the Eastern and Western Pacific Ocean. In addition, larger zonal temperature gradients were recorded in the major stadials of interglacial periods(MIS 5b and MIS 7d). In contrast, the temperature gradients between the West and East Pacific Ocean decreased significantly during the deglacial periods(MIS 6/ 5, MIS 8/ 7 and MIS 10/ 9).The patterns of the zonal temperature gradient across the tropical Pacific Ocean imply that the ocean conditions therein showed more La Niña-like states in the colder periods and more El Niño-like states during the warmer stages over the past few hundred thousand years. Nevertheless, the significant fluctuations in the zonal temperature gradient also indicate the instability of ENSO-like states in the tropical Pacific Ocean over a longer time-scale. When the earth-surface temperature rises, the rapid increase of water vapor concentration in the lower troposphere could weaken the mass exchange between the boundary layer and the troposphere, and thus slow down the zonal atmosphere circulation in the tropical Pacific Ocean that may result in a decreased zonal temperature gradient with a more El Niño-like state. 2020, Vol.40

2020, Vol.40