2 中国科学院地质与地球物理研究所, 中国科学院新生代地质与环境重点实验室, 北京 100029)

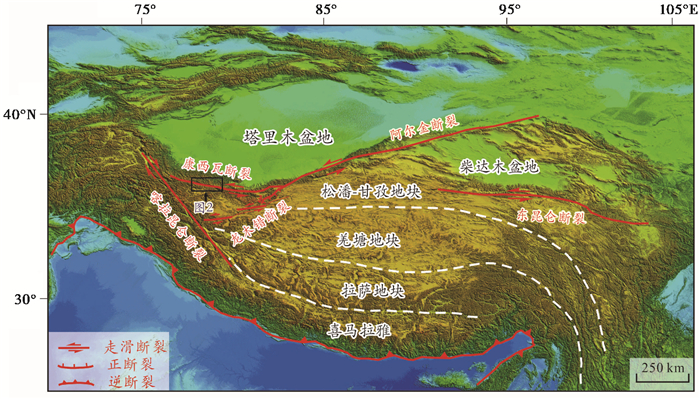

青藏高原作为世界上面积最大、最年轻、最活跃的高原,其目前的主要构造地貌特征是新生代以来印度板块和亚洲板块碰撞及其随后的陆陆汇聚作用的结果[1]。在空间上,青藏高原周缘发育延伸规模达数百公里乃至上千公里的大型走滑断裂。这些断裂的发育是青藏高原活动构造的最显著特征之一,同时也吸引了许多地质工作者的关注[2~4]。此次研究对象康西瓦断裂是青藏高原西北缘的一条大型左旋走滑断裂(图 1)。也有学者称该断裂为喀拉喀什断裂[5~6],或阿尔金断裂带喀拉喀什河谷段[7~8]。该断裂在卫星遥感影像上呈现非常显著的线性构造,东段呈近EW向,西段呈WNW-ESE向,总体延伸近700 km[9]。康西瓦断裂和位于其东边的阿尔金断裂构成了青藏高原北部和塔里木盆地的重要地质边界。

|

图 1 青藏高原主要活动断裂构造纲要图 Fig. 1 The major active strike-slip and reverse faults around the Tibetan Plateau |

目前,对康西瓦断裂走滑速率的研究程度仍相对较低,Shen等[10]根据GPS观测数据,认为康西瓦断裂走滑速率为7±3 mm/a; Wright等[8]根据卫星雷达干涉测量的结果,认为康西瓦断裂走滑速率为5±5 mm/a。由于这些大地测量学结果只记录了最近几年或十几年短周期康西瓦断裂带的活动,因此,以上观测结果不能反映更长时间尺度的走滑速率。对于康西瓦断裂地质时期的走滑速率,不同学者之间仍存在较大争议[1, 7, 11~12]。产生争议的原因可能与不同研究方法以及与错断地质体错距、年代测定的可靠性有关。Peltzer等[7]根据沿康西瓦断裂错断冲积扇或阶地的位错量200±20 m,并假设这些发育在海拔4000~5000 m附近的错断冲积扇或阶地形成年代为10±2 ka B.P.,估算出康西瓦断裂左旋走滑速率为大约20~30 mm/a; Avouac和Tapponnier[13]根据刚性地块模型估算康西瓦断裂左旋走滑速率为24~25 mm/a。然而,其他学者认为康西瓦断裂地质时期的左旋走滑速率要慢得多,其速率大小为8~12 mm/a[9]和6.5~10.0 mm/a[11]。李海兵等[12]在喀拉喀什河谷段三十里营房东侧地区,通过应用10Be和14C定年技术对不同错断河流阶地形成时代进行测定,结合相应阶地的位错量,估算康西瓦断裂晚第四纪的左旋走滑速率为2~18 mm/a;Li等[14]认为康西瓦断裂晚全新世的左旋走滑速率为6~7 mm/a。目前,对康西瓦断裂晚第四纪左旋走滑速率进行准确估计的主要瓶颈之一是缺少相应错断地质体可靠的年代学约束。对康西瓦断裂晚第四纪走滑速率的准确厘定,有助于进一步理解青藏高原西北缘晚第四纪的构造变形,并对评估相关区域的构造活动和地质灾害具有非常重要的意义。

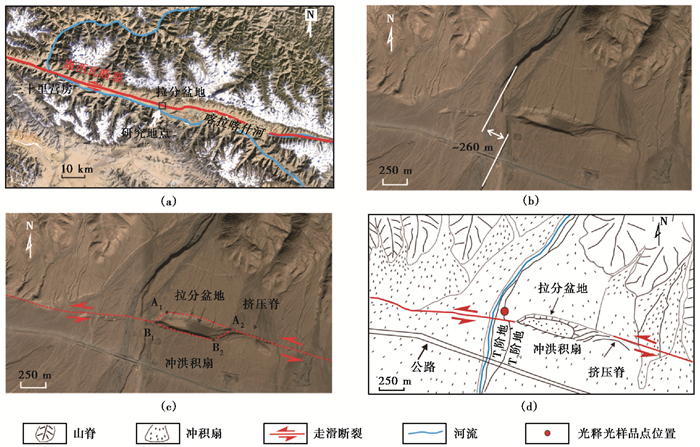

此次研究地点为康西瓦断裂在青藏高原西北缘沿喀拉喀什河谷一处冲洪积扇(图 2a)。它位于新藏公路里程碑415 km附近。该洪积扇上发育了一个小型拉分盆地和错断河流阶地(图 2b~2d)。前人对该拉分盆地的地貌特征、规模大小进行了相关报道[1, 9, 12, 15]。该拉分盆地长边B1-B2的长度为约450 m[15](图 2c),而拉分盆地整体长度B1-A2约为650 m[9](图 2c)。但是由于缺少年代数据,利用该拉分盆地的水平位错来估算康西瓦断裂晚第四纪的平均左旋走滑速率还未见报道。本文基于该拉分盆地演化与冲洪积扇的关系,分别利用拉分盆地的长边和斜边限定该冲洪积扇的水平位错量,并利用光释光定年技术约束该冲洪积扇的形成年代,进而定量评估康西瓦断裂晚第四纪的平均左旋走滑速率。与此同时,利用冲洪积扇上河流阶地陡坎T2/T1的水平位错来估计河流阶地T2的水平位错(图 2b),并利用光释光定年技术约束T2阶地的放弃年龄。最后结合T2水平位错和放弃年代,定量估算康西瓦断裂晚第四纪的平均左旋走滑速率。

|

图 2 Google Earth图像显示在喀拉喀什河谷沿康西瓦断裂发育一个小型拉分盆地和错断河流阶地 (a)研究地点在喀拉喀什河谷所在位置;(b)研究对象错断河流阶地及错距;(c)研究对象拉分盆地形态;(d)研究地点拉分盆地、错断河流阶地和光释光采样地点示意图 Fig. 2 Google Earth map showing a small pull-apart basin and offset river terrace in the Karakax valley. (a)The location of the studied site in the Karakax valley; (b)The studied river terrace and its offset; (c)The size of pull-apart basin; (d)Schematic map showing the pull-apart basin, offset river terrace and the location of optically stimulated luminescence(OSL)dating samples |

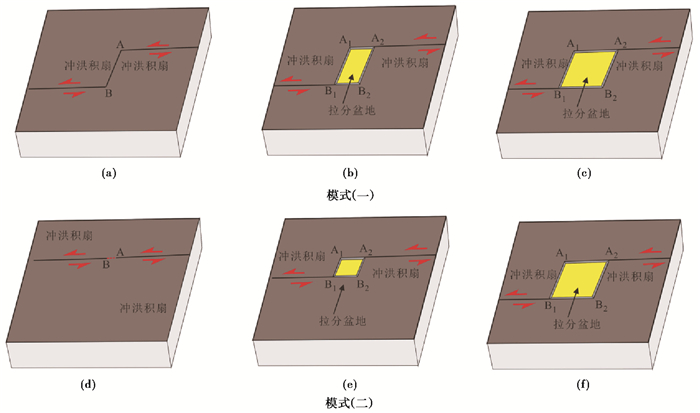

本文研究的拉分盆地为康西瓦断裂局部拉伸形成的小型断陷盆地,盆地的两条长边(图 2c的A1-A2和B1-B2)为走滑断层,而两条短边(图 2c的A1-B1和A2-B2)为正断层,拉分盆地整体形状(图 2c的A1B1B2A2)似平行四边形。由于该拉分盆地发育在冲洪积扇上,因此该拉分盆地与该冲洪积扇存在一定的演化关系(图 3):即该拉分盆地是由该冲洪积扇左旋错断而形成。在本文中,假定了两种拉分盆地的演化简单模式。第一种模式中(图 3a、3b和3c),该拉分盆地的发育过程中,随着南北两条走滑断裂断距的逐渐累积,拉分盆地的整体宽度保持相对固定[16],即拉分盆地A1B1B2A2(图 3b和3c)形成初期,A1与A2点重合为图 3a中的A点;而B1与B2重合为图 3a中的B点。对于这种情况,冲洪积扇在错动之前,冲洪积扇的A1应该与A2重合,B1点应该与B2重合。所以,拉分盆地长度A1-A2或B1-B2也记录了该冲洪积扇被康西瓦断裂错动的水平距离。因此,有了拉分盆地长度A1-A2或B1-B2,相当于就知道了该冲洪积扇被康西瓦断裂错动的水平距离,只要通过相关年代技术对该冲洪积扇的年代进行测定,就可以有效评估康西瓦断裂在该冲洪积扇形成之后的平均左旋走滑速率。第二种拉分盆地的演化模式中(图 3d、3e和3f),随着南北两条走滑断裂断距的逐渐累积,盆地长度和宽度同时增加[16~17]。即最开始初期,拉分盆地南北的两条走滑断裂A1-A2和B1-B2可能有部分重叠。在这种情况,冲洪积扇在错动之前,冲洪积扇上的B1可能与A2重合。此时,笔者利用拉分盆地的斜边长度B1-A2来限定拉分盆地的最大位移量,即位移量小于650 m[9]。

|

图 3 冲洪积扇与拉分盆地的演化关系 Fig. 3 The evolution of pull-apart basin and its relationship with alluvial fan |

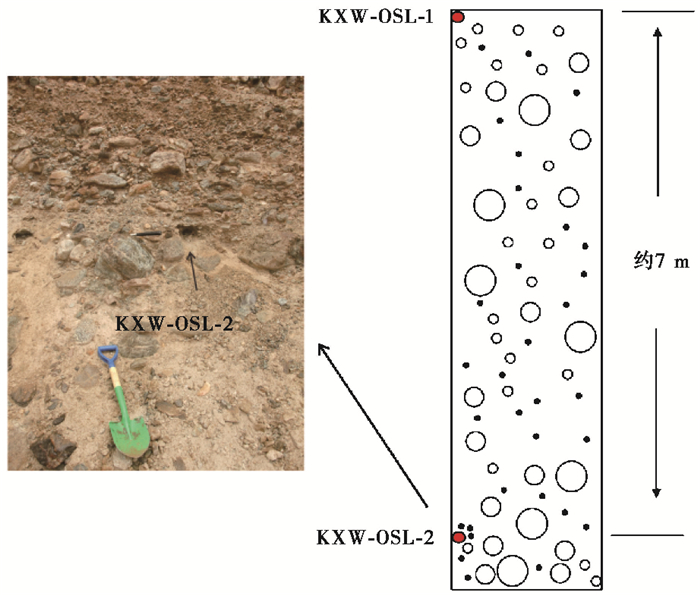

本次研究利用释光测年技术对该冲洪积扇和河流阶地(T2)进行限定。该技术是直接测量沉积物中的石英和长石碎屑颗粒最后一次曝光到现在的埋藏年龄,其范围可以从几年到几十万年[18]。目前为止,该技术在晚第四纪风成或沙漠、湖滨相和河流相沉积物的年代测定中得到了广泛的应用和认可,并已应用于晚第四纪断层活动的年代学测定当中[19~33]。笔者在研究地点(图 2d)(36°14′ 20.0″N,78°32′ 37.2″E)沿河流阶地陡坎T2/T1约7 m厚的剖面采集了2个光释光样品(图 4)。样品(KXW-OSL-1)在陡坎T2/T1剖面顶部,此样品的光释光年龄代表了T2河流阶地的放弃年龄;样品(KXW-OSL-2)在陡坎T2/T1剖面靠近底部。从野外观察来看,陡坎T2/T1剖面上靠近底部由冲洪积物组成,包括有直径大于10 cm、小于10 cm的砾石和砂粒,分选差(图 4)。笔者在陡坎T2/T1剖面尽量靠近底部的一夹砂处采集样品(KXW-OSL-2),该样品应该代表了T2阶地开始形成的年龄,同时也代表了该洪积扇的发育的最小年龄,即理论上该冲洪积扇的年龄大于或等于KXW-OSL-2的光释光年龄。

|

图 4 研究地点光释光野外采样图 Fig. 4 The OSL dating sampling at the studied site |

光释光样品的前处理、含水量和等效剂量的测试在中国科学院地质与地球物理研究所光释光测年实验室测量。在实验室暗室的弱红光灯下,从样品管的中心部位取出部分样品。前处理步骤如下:1)用10 %的盐酸和10 %的双氧水去除碳酸盐胶结物和有机质;2)烘干样品后,利用干筛法筛选90~125 μm的样品;3)利用多钨酸钠重液(2.62 g/cm3和2.75 g/cm3)分离出石英颗粒;4)40 %氢氟酸反应1.5~2.0小时去除残余长石并分离出纯净石英。

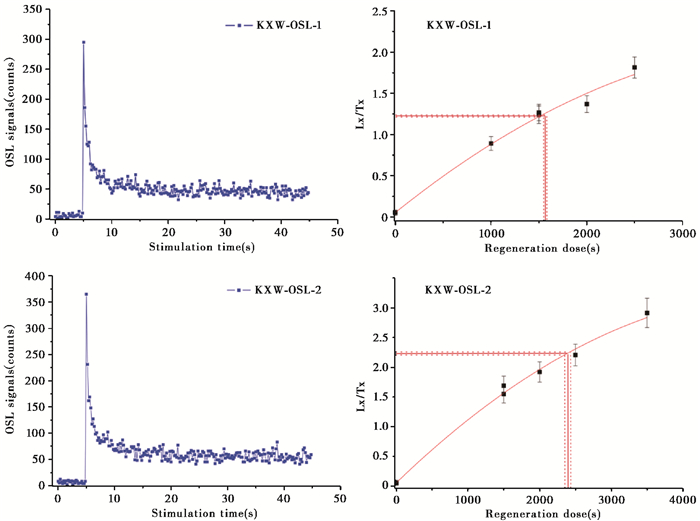

光释光测量在丹麦Risø TL/OSL-DA-15全自动释光仪上完成。激发光源为蓝光二极管(波长为470±30 nm),检验长石组分所用的红外光源为红外二极管(波长为870 ± 40 nm)[34]。接受释光信号的光电倍增管前放置7.5 mm的U340滤光片。仪器β辐射源为90 Sr/90Y beta,剂量大小为0.081 Gy/s。样品等效剂量采用单片再生剂量法(SAR)[35]。在样品测试过程,发现样品天然光释光信号快速衰减,并具有良好的剂量再生曲线(图 5),表明石英单片再生剂量测试方法对该区域的样品具有很好的适用性。

|

图 5 研究地点样品代表性光释光信号衰减曲线(a,c)和剂量生长曲线(b,d) Fig. 5 Representative OSL decay curves(a, c)and dose response curves(b, d)of the samples at the studied site |

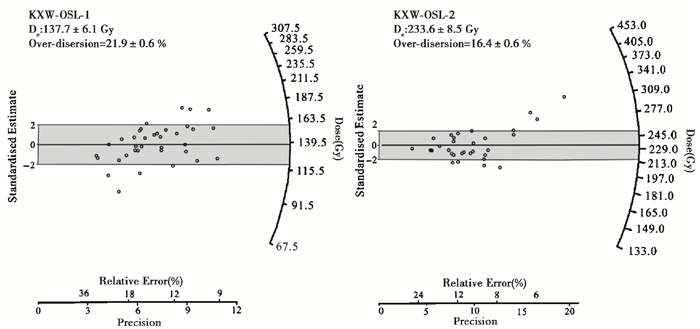

在此次测量中,为了提高年代测试结果的可靠性,每个样品测量30~40片左右(准备测片时,用硅油将粗石英颗粒粘至铝片中心的2~3 mm处)。相关测试结果如图 6所示。结果表明对于样品KXW-OSL-1,不同测片的等效剂量在样品中值周围对称分布,而且大部分测片在中值误差范围2 σ之内。对于样品KXW-OSL-2,有类似的现象。利用中值年龄模型[36]计算结果表明阶地顶部KXW-OSL-1样品的等效剂量为137.7±6.1 Gy,而靠近阶地底部KXW-OSL-2的等效剂量为233.6±8.5 Gy。

|

图 6 河流阶地样品KXW-OSL-1和KXW-OSL-2的等效剂量(De)雷达图 Fig. 6 Radial plot results for De distributions of samples(KXW-OSL-1 and KXW-OSL-2) |

为了获得样品的光释光年龄,需要测量样品的年剂量率。沉积物样品的铀、钍和钾元素含量分析在核工业北京地质研究所分析测试中心完成。宇宙射线剂量率的贡献根据采样点的深度、经纬度和海拔高度计算[37]。样品的年剂量率的相关数据见表 1。计算结果表明样品KXW-OSL-1的年剂量率为4.46±0.23 Gy/ka,而KXW-OSL-2的年剂量率为4.46±0.24 Gy/ka。经过计算,KXW-OSL-1的年代测试结果为30.9±2.1 ka,而KXW-OSL-2的年代测试结果为52.4±3.4 ka。相关测年结果表明该冲洪积扇至少在约52 ka已经开始发育,而河流阶地T2的放弃年龄在约31 ka左右。

| 表 1 河流阶地样品KXW-OSL-1和KXW-OSL-2年剂量率测试结果 Table 1 Annual dose rate results for the samples(KXW-OSL-1 and KXW-OSL-2) |

要有效评估康西瓦断裂的左旋走滑速率,需要准确厘定错断地质体的水平位错和对应形成年代。在此次研究当中,我们利用Google Earth软件对研究区域的拉分盆地的长边(B1-B2)以及斜边长度(B1-A2)分别进行了测量,测量结果与何哲峰等[15]、付碧宏等[9]的结果较为一致。在计算走滑速率时,考虑了拉分盆地两种不同的简单演化模式。在拉分盆地的演化模式一(图 3a、3b和3c)中,笔者利用拉分盆地的长边(B1-B2,约450 m)[15]来计算洪冲积扇的水平位错,而非拉分盆地的斜边(B1-A2,约650 m)[9]。原因是根据图 3a、3b和3c中拉分盆地与洪冲积扇的演化关系中,可以知道洪冲积扇被康西瓦断裂错动形成拉分盆地之前,B1应该与B2重合,而不是与A2点重合(图 3a)。所以,利用该拉分盆地长边B1-B2来估算对应洪冲积扇的水平位错更为合适。考虑到Google Earth软件和野外测量的误差,此次计算走滑速率的时候,笔者赋予该水平位错10 %的误差,即洪冲积扇的水平错动距离为450±45 m。对于冲洪积扇的形成年代,本文利用阶地陡坎剖面T2/T1靠近底部夹砂样品(KXW-OSL-2,52.4±3.4 ka)来约束,计算出康西瓦断裂的晚四纪平均左旋走滑速率为8.6±1.0 mm/a。由于样品KXW-OSL-2的年代应为冲洪积扇的最小年龄,因此实际的走滑速率应小于等于该计算值。在拉分盆地的演化模式二(图 3e、3f和3g)中,笔者利用拉分盆地的斜边(B1-A2,约650±65 m)[9]来限定洪冲积扇的最大水平位错(即位错量小于650 m)。同时,本文利用阶地陡坎剖面T2/T1靠近底部夹砂样品(KXW-OSL-2,52.4±3.4 ka)来约束冲洪积扇最小年龄。因此,洪冲积扇的最大水平位错和其最小年龄计算出的走滑速率(12.4±1.5 mm/a)应该为康西瓦断裂的晚四纪平均左旋走滑速率的上限值。

如果以冲洪积扇发育的阶地陡坎T2/T1为错断标志,其水平位错为260±26 m(图 2b)(考虑到Google Earth软件误差,笔者赋予该水平位错10 %的误差),并利用阶地陡坎剖面T2/T1靠近顶部夹砂样品(KXW-OSL-1,30.9±2.1 ka)代表的T2阶地的放弃年龄。计算出康西瓦断裂的晚四纪平均左旋走滑速率为8.4±1.0 mm/a。因此,本次研究中得出的晚第四纪平均左旋走滑速率和现代全球定位系统的观测结果(7±3 mm/a)[10],以及根据卫星雷达干涉测量的结果(5±5 mm/a)[8]较为一致,并非Peltzer等[7]、Avouac和Tapponnier[13]认为的大于20 mm/a。

4 讨论本次研究具有一定的局限性。在利用拉分盆地的规模大小来评估对应冲洪积扇的水平位错时,假定了两种较为简单的演化模式。而该拉分盆地实际的演化过程可能更为复杂。并且在本文拉分盆地的演化模式的第二种,也只是利用斜边B1-A2来估算水平位错的上限值,而对真实的水平位错并未加以详细分析。在图 2标出的断裂外,附近还有不少断层陡坎。这些断层陡坎吸收了多少位移量,这些断层陡坎的发育对评估康西瓦断裂活动速率有多少影响也尚不清楚。因此,本文得出的康西瓦断裂晚第四纪平均左旋走滑速率仍具有一定不确定性。

另外,本次研究地点仅是康西瓦走滑断裂带内一个很小的区域。康西瓦断裂为青藏高原西北缘的大型左旋走滑断裂,整体长度较长,总体延伸近700 km[9]。本文得出的走滑速率不一定能完全限定整个断裂的走滑速率。为了准确厘定康西瓦走滑断裂晚第四纪平均左旋走滑速率,在之后的研究,还需要进一步对该断裂带内不同地点、不同地质体开展综合研究,例如在康西瓦走滑断裂西段,在三十里营房东侧约5 km处,Gong等[39]通过河流阶地的研究,估算出该地点康西瓦断裂晚第四纪平均左旋走滑速率为7.8±1.6 mm/a。

高分辨率和多数量的测年结果的缺乏,也影响了本文的研究结果,这是我们以后加强本地区研究的重点。

5 结论在青藏高原西北缘喀拉喀什河谷段,利用卫星遥感影像分析,结合构造地貌观测和光释光定年分析,对沿康西瓦断裂发育的一个小型拉分盆地、错断阶地和冲洪积扇开展研究,对康西瓦断裂晚第四纪构造活动及晚第四纪平均左旋走滑速率得到如下认识:

(1) 康西瓦断裂为青藏高原西北缘晚第四纪活动断裂,该断裂在喀拉喀什河谷段发育一系列以左旋错断为特征的地貌,如错断河流阶地和拉分盆地等。

(2) 青藏高原西北缘沿喀拉喀什河谷,位于新藏公路里程碑415 km附近处,发育一冲洪积扇。该冲洪积扇由于左旋错断而形成拉分盆地。与此同时,该冲洪积扇发育有两级河流阶地。

(3) 光释光技术在该地区石英样品具有良好的实用性。释光测年表明该冲洪积扇至少约52.4±3.4 ka开始形成。

(4) 由于该拉分盆地与对应的冲洪积扇存在演化关系:即冲洪积扇错动而形成拉分盆地。

因此,基于拉分盆地演化的两种简单模式,分别利用拉分盆地长边和斜边估算对应冲洪积扇的水平位错量和水平位错量的上限值。第一种模式:当随着拉分盆地的发育过程中,拉分盆地的整体宽度保持相对固定,南北两条走滑断裂断距逐渐累积,因此拉分盆地的长边记录了对应冲洪积扇的水平位错量(450±45 m),结合冲洪积扇的形成年代,估算出康西瓦断裂的晚四纪平均左旋走滑速率为小于等于8.6±1.0 mm/a。第二种模式:当随着拉分盆地的发育过程中,南北两条走滑断裂断距的逐渐累积,盆地长度和宽度同时增加。此时,该拉分盆地的斜边(B1-A2,650±65 m)为该洪冲积扇的最大水平位错。利用冲洪积扇的形成年代估算出康西瓦断裂的晚四纪平均左旋走滑速率为小于约12.4 mm/a。

(5) 以冲洪积扇发育的阶地陡坎T2/T1为错断标志,其水平位错为260±26 m,而对应阶地的放弃年龄为30.9±2.1 ka,估算出康西瓦断裂晚第四纪以来的平均左旋走滑速率在8.4±1.0 mm/a。因此,康西瓦断裂在青藏高原西北缘为调节印度-欧亚板块的碰撞起着非常重要的作用。

致谢: 感谢孙继敏研究员野外采样提供了帮助;感谢审稿人和编辑部老师提出的宝贵修改建议。

| [1] |

付碧宏, 时丕龙, 贾营营. 青藏高原大型走滑断裂带晚新生代构造地貌生长及水系响应. 地质科学, 2009, 44(4): 1343-1363. Fu Bihong, Shi Pilong, Jia Yingying. Late Cenozoic tectono-geomorphic growth and drainage response along the large-scale strike-slip fault system, Tibetan Plateau. Chinese Journal of Geology, 2009, 44(4): 1343-1363. |

| [2] |

薛灵文, 王刚, 李正友等. 东昆仑西大滩盆地晚新生代构造地貌简析. 第四纪研究, 2016, 36(2): 420-432. Xue Lingwen, Wang Gang, Li Zhengyou et al. Late Cenozoic tectonic landform analysis of Xidatan basin, eastern Kunlun. Quaternary Sciences, 2016, 36(2): 420-432. |

| [3] |

郑文俊, 袁道阳, 张培震等. 青藏高原东北缘活动构造几何图像、运动转换与高原扩展. 第四纪研究, 2016, 36(4): 775-788. Zheng Wenjun, Yuan Daoyang, Zhang Peizhen et al. Tectonic geometry and kinematic dissipation of the active faults in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau and their implications for understanding northeastward growth of the plateau. Quaternary Sciences, 2016, 36(4): 775-788. |

| [4] |

秦翔, 施炜, 李恒强等. 基于DEM地形特征因子的青藏高原东北缘宁南弧形断裂带活动性分析. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(2): 213-223. Qin Xiang, Shi Wei, Li Hengqiang et al. Tectonic differences of the Southern Ningxia arc-shape faults in the northeast Tibetan Plateau based on Digital Elevation Model. Quaternary Sciences, 2017, 37(2): 213-223. |

| [5] |

Yin A, Rumelhart P E, Butler R et al. Tectonic history of the Altyn Tagh fault system in northern Tibet inferred from Cenozoic sedimentation. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 2002, 114(10): 1257-1295. DOI:10.1130/0016-7606(2002)114<1257:THOTAT>2.0.CO;2 |

| [6] |

Lin A, Kano K-I, Guo J et al. Late Quaternary activity and dextral strike-slip movement on the Karakax Fault Zone, northwest Tibet. Tectonophysics, 2008, 453(1): 44-62. |

| [7] |

Peltzer G, Tapponnier P, Armijo R. Magnitude of Late Quaternary left-lateral displacements along the north edge of Tibet. Science, 1989, 246(4935): 1285-1289. DOI:10.1126/science.246.4935.1285 |

| [8] |

Wright T J, Parsons B, England P C et al. InSAR observations of low slip rates on the major faults of western Tibet. Science, 2004, 305(5681): 236-239. DOI:10.1126/science.1096388 |

| [9] |

付碧宏, 张松林, 谢小平等. 阿尔金断裂系西段——康西瓦断裂的晚第四纪构造地貌特征研究. 第四纪研究, 2006, 26(2): 228-235. Fu Bihong, Zhang Songlin, Xie Xiaoping et al. Late Quaternary tectono-geomorphic features along the Kangxiwar Fault, Altyn Tagh fault system, northern Tibet. Quaternary Sciences, 2006, 26(2): 228-235. |

| [10] |

Shen Z K, Wang M, Li Y et al. Crustal deformation along the Altyn Tagh fault system, Western China, from GPS. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 2001, 106(B12): 30607-30621. DOI:10.1029/2001JB000349 |

| [11] |

Ding G, Chen J, Tian Q et al. Active faults and magnitudes of left-lateral displacement along the northern margin of the Tibetan Plateau. Tectonophysics, 2004, 380(3-4): 243-260. DOI:10.1016/j.tecto.2003.09.022 |

| [12] |

李海兵, Van der Woerd J, 孙知明等. 阿尔金断裂带康西瓦段晚第四纪以来的左旋滑移速率及其大地震复发周期的探讨. 第四纪研究, 2008, 28(2): 198-213. Li Haibing, Van der Woerd J, Sun Zhiming et al. Late Quaternary left-slip rate and large earthquake recurrence time along the Kangxiwar(or Karakax) segment of the Altyn Tagh Fault, northern Tibet. Quaternary Sciences, 2008, 28(2): 198-213. |

| [13] |

Avouac J P, Tapponnier P. Kinematic model of active deformation in Central Asia. Geophysical Research Letters, 1993, 20(10): 895-898. DOI:10.1029/93GL00128 |

| [14] |

Li H, Van der Woerd J, Sun Z et al. Co-seismic and cumulative offsets of the recent earthquakes along the Karakax left-lateral strike-slip fault in western Tibet. Gondwana Research, 2012, 21(1): 64-87. DOI:10.1016/j.gr.2011.07.025 |

| [15] |

何哲峰, 黎敦朋, 刘健等. 康西瓦断裂带晚新生代构造地貌特征及其构造意义. 第四纪研究, 2009, 29(3): 616-624. He Zhefeng, Li Dunpeng, Liu Jian et al. Late Cenozoic tectono-geomorphic features of the Kangxiwar fault zone, northwestern Tibetan Plateau, and its tectonic implication. Quaternary Sciences, 2009, 29(3): 616-624. |

| [16] |

Gürbüz A. Geometric characteristics of pull-apart basins. Lithosphere, 2010, 2(3): 199-206. DOI:10.1130/L36.1 |

| [17] |

Aydin A, Nur A. Evolution of pull apart basins and their scale independence. Tectonics, 1982, 1(1): 91-105. DOI:10.1029/TC001i001p00091 |

| [18] |

Aitken M J. An Introduction to Optical Dating. London: Oxford Unversity Press, 1998: 1-90.

|

| [19] |

邱思静, 陈一凡, 王振等. 天山北麓乌鲁木齐河阶地晚更新世黄土磁学特征及古气候意义. 第四纪研究, 2016, 36(5): 1319-1330. Qiu Sijing, Chen Yifan, Wang Zhen et al. Rock magnethic properties and paleoclimatic implications of Late Pleistocene loess in the range front of the Vrümqi River, Xinjiang, NW China. Quaternary Sciences, 2016, 36(5): 1319-1330. |

| [20] |

贾广菊, 徐树建, 孔凡彪等. 山东大黑山岛北庄黄土沉积特征及其环境演变. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(3): 522-534. Jia Guangju, Xu Shujian, Kong Fanbiao et al. The sedimentary characterisitics and environmental evolution of the Beizhuang loess in the Daheishan Island, Shandong Province. Quaternary Sciences, 2017, 37(3): 522-534. |

| [21] |

毛沛妮, 庞奖励, 黄春长等. 汉江上游黄土记录的MIS 3晚期气候变化特征. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(3): 535-547. Mao Peini, Pang Jiangli, Huang Chunchang et al. Climate change during the late stages of MIS 3 period inferred from the loess record in the upper Hanjinag River valley. Quaternary Sciences, 2017, 37(3): 535-547. |

| [22] |

耿建伟, 赵晖, 王兴繁等. 历史时期额济纳盆地水系与绿洲演变过程及其机制研究. 第四纪研究, 2016, 36(5): 1204-1215. Geng Jianwei, Zhao Hui, Wang Xingfan et al. Oasis and drainage network evolution processes and mechanisms of Ejina Basin during historical period. Quaternary Sciences, 2016, 36(5): 1204-1215. |

| [23] |

Cheong C S, Hong D G, Lee K S et al. Determination of slip rate by optical dating of fluvial deposits from the Wangsan Fault, SE Korea. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2003, 22(10-13): 1207-1211. DOI:10.1016/S0277-3791(03)00020-9 |

| [24] |

Chen Y G, Chen Y W, Chen W S et al. Optical dating of a sedimentary sequence in a trenching site on the source fault of the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake, Taiwan. Quaternary International, 2009, 199(1): 25-33. |

| [25] |

Nogueira F C, Bezerra F H R, Fuck R A. Quaternary fault kinematics and chronology in intraplate northeastern Brazil. Journal of Geodynamics, 2010, 49(2): 79-91. DOI:10.1016/j.jog.2009.11.002 |

| [26] |

Chen Y, Li S H, Li B. Slip rate of the Aksay segment of Altyn Tagh Fault revealed by OSL dating of river terraces. Quaternary Geochronology, 2012, 10(7): 291-299. |

| [27] |

Chen Y, Li S H, Sun J et al. OSL dating of offset streams across the Altyn Tagh Fault:Channel deflection, loess deposition and implication for the slip rate. Tectonophysics, 2013, 594(3): 182-194. |

| [28] |

杨会丽, 陈杰, 冉勇康等. 汶川8.0级地震小鱼洞地表破裂带古地震事件的光释光测年. 地震地质, 2011, 33(2): 402-412. Yang Huili, Chen Jie, Ran Yongkang et al. Optical dating of paleoearthquake similar to the 12 May Wenchuan earthquake, at Xiaoyudong surface ruptures zone. Seismology and Geology, 2011, 33(2): 402-412. |

| [29] |

孙高元, 龚志军. 乌兰巴托以西断裂活动时代的光释光年代学研究. 地震地质, 2013, 35(2): 322-327. Sun Gaoyuan, Gong Zhijun. OSL dating of fault activity in the west of Ulaanbaatar. Seismology and Geology, 2013, 35(2): 322-327. |

| [30] |

Gong Z, Li S H, Li B. Late Quaternary faulting on the Manas and Hutubi reverse faults in the northern foreland basin of Tian Shan, China. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2015, 424: 212-225. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2015.05.030 |

| [31] |

Fu X, Li S H, Li B et al. A fluvial terrace record of Late Quaternary folding rate of the Anjihai anticline in the northern piedmont of Tian Shan, China. Geomorphology, 2017, 278: 91-104. DOI:10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.10.034 |

| [32] |

隆浩, 张静然. 晚第四纪湖泊演化光释光测年. 第四纪研究, 2016, 36(5): 1191-1203. Long Hao, Zhang Jingran. Luminescence dating of Late Quaternary lake-levels in Northern China. Quaternary Sciences, 2016, 36(5): 1191-1203. |

| [33] |

张威, 刘亮, 柴乐等. 基于年代学证据的螺髻山第四纪冰川作用研究. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(2): 281-292. Zhang Wei, Liu Liang, Chai Le et al. Characteristics of Quaternary glaciations using ESR dating method in the Luoji Mountain, Sichuan Province. Quaternary Sciences, 2017, 37(2): 281-292. |

| [34] |

Bøtter-Jensen L, Andersen C E, Duller G A T et al. Developments in radiation, stimulation and observation facilities in luminescence measurements. Radiation Measurements, 2003, 37(4-5): 535-541. DOI:10.1016/S1350-4487(03)00020-9 |

| [35] |

Murray A S, Wintle A G. Luminescence dating of quartz using an improved single-aliquot regenerative-dose protocol. Radiation Measurements, 2000, 32(1): 57-73. DOI:10.1016/S1350-4487(99)00253-X |

| [36] |

Galbraith R F, Roberts R G, Laslett G M et al. Optical dating of single and multiple grains of quartz from jinmium rock shelter, Northern Australia, part 1, Experimental design and statistical models. Archaeometry, 1999, 41(2): 339-364. DOI:10.1111/arch.1999.41.issue-2 |

| [37] |

Prescott J R, Hutton J T. Cosmic-ray contributions to dose-rates for luminescence and ESR dating-large depths and long-term time variations. Radiation Measurements, 1994, 23(2-3): 497-500. DOI:10.1016/1350-4487(94)90086-8 |

| [38] |

Aitken M J. Thermoluminescence Dating. London: Academic Press, 1985: 289-296.

|

| [39] |

Gong Z, Sun J, Zhang Z et al. Optical dating of an offset river terrace sequence across the Karakax fault and its implication for the Late Quaternary left-lateral slip rate. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 2017, 147: 415-423. DOI:10.1016/j.jseaes.2017.07.013 |

2 Key Laboratory of Cenozoic Geology and Environment, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029)

Abstract

The Kangxiwar Fault is one of the largest left-lateral strike-slip faults at the rim of northwestern Tibetan Plateau. However, the Late Quaternary slip rate of the Kangxiwar Fault is still in debates. In this study, a small pull-apart basin and an offset river terrace across the Kangxiwar Fault were identified near the Xinjiang-Tibet highway milepost 415 km. Both the small pull-apart basin and offset river terrace were formed within an alluvial fan in the Karakax valley due to the Late Quaternary faulting along the Kangxiwar Fault. For the pull-apart basin, two models were assumed. In the first model of the pull-apart basin, the width of the pull-apart basin did not increase significantly and remained constant during its evolution. Thus, the long side of the pull-apart basin(450±45 m) can be used as the offset of the alluvial fan. An optically stimulated luminescence(OSL) sample(KXW-OSL-2) was collected at the bottom of terrace riser(T2/T1) (36°14' 20.0″N, 78°32' 37.2″E), and the corresponding age was used to constrain the youngest age of the alluvial fan. The OSL dating results show that the alluvial fan formed at or before 52.4±3.4 ka. Thus, the average left-lateral slip rate of the Kangxiwar Fault was estimated at less or equal to 8.6±1.0 mm/a. In the second model of the pull-apart basin, both the width and length increased during the evolution of the pull-apart basin. In this case, the hypotenuse(650±65 m) was used to estimate the maximum offset of the alluvial fan. Correspondingly, together with the OSL age of the alluvial fan, the average left-lateral slip rate of the Kangxiwar Fault was estimated at less than ca. 12.4 mm/a. For the older terrace within the alluvial fan, another OSL sample(KXW-OSL-1) was collected at the terrace tread of T2, and the results show that the terrace was abandoned at 30.9±2.1 ka. If the terrace riser was used as the offset marker, the horizontal displacement of the terrace was estimated at 260±26 m. Together with the abandoned age of the river terrace within the alluvial fan, the average left-lateral slip rate of the Kangxiwar Fault was estimated at 8.4±1.0 mm/a. The estimated slip rates of Kangxiwar Fault are consistent with the results from satellite observations, suggesting that the Kangxiwar Fault plays an important role in accommodating eastward movement of the Tibetan Plateau at the northwest during the Late Quaternary. 2018, Vol.38

2018, Vol.38