② 郑州市文物考古研究院, 郑州 450005)

1 引言

残留物分析是探讨动植物资源利用、先民食物结构、生业经济状况以及器物功能的重要途径之一[1]。20世纪80年代淀粉粒分析方法兴起之后,植物淀粉粒成为残留物分析的重要研究对象,特别是Barton等[2]的研究表明利用淀粉粒等植物性残留物进行石制品的功能研究是完全可行且可信的。石制品的残留淀粉粒分析,能使我们获得这些器物功能的直接证据,有力推动了石制品功能的研究[3, 4]; 同时也为探讨考古遗址植物资源利用、先民植物性食物来源以及生业经济状况提供了全新视角[5, 6, 7, 8]。

望京楼遗址位于河南省新郑市新村镇望京楼水库的东侧(34°26′42.6″N,113°43′25.4″E),海拔119m。北距郑州市区35km,因遗址西南角的一处夯土台基称为望京楼而得名。黄水河从遗址西侧流过折而向东,郑新公路从遗址中部南北穿过。该遗址发现于20世纪60年代,2010年9月-2011年6月,郑州市文物考古研究院对望京楼遗址进行了大规模的考古调查、勘探和发掘,发现了二里头文化城址和二里岗文化城址各一座。望京楼城址作为郑州地区新近发现的夏商时期重要城址,为研究中国古代早期城池建制以及夏商文化分界提供了重要资料[9]。

石杵和石臼自新石器时代以来就是重要的食物加工工具[10],本文运用淀粉粒分析方法,对望京楼遗址出土的二里头文化时期石臼和石杵开展残留物分析,了解这些器物的使用对象和具体功用,探讨该遗址二里头文化时期的植物资源利用状况。望京楼遗址作为近些年发掘的又一处包含二里头文化遗存的重要聚落,对该遗址开展包括淀粉粒分析在内的植物遗存研究,将有助于我们深入认识中原腹心地区二里头文化时期先民的生业方式和农业经济特点。

2 实验样品和方法 2.1 实验样品本研究选取了望京楼遗址出土的二里头文化石器3件,分别是石杵2件和石臼(残断)1件(图1)。

|

图1 望京楼遗址出土的石臼、石杵样品 1——2011xxwⅢT1902 H500出土石臼(残); 2——2011xxwⅢT2102 H454出土石杵; 3——T0602 H525出土石杵 Fig.1 Mortar and pestle samples for starch grain analysis from Wangjinglou site |

这批石器在发掘出来后均被清洗保存,在发掘过程中也未采集石器周围土壤样品作为对比样品。因此,我们选择对这批石器的使用部位和非使用部位分别进行取样,以进行比对分析。由于石臼本身较大,无法通过超声方法获取石臼使用部位的残留物,故石臼和石杵的取样方法存在差异,具体步骤分别如下。

|

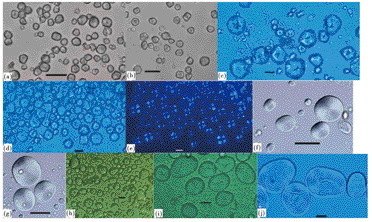

图2 部分现代植物淀粉粒图谱 (a)、(b)、(f)、(g)标尺为20μm; 其余为10μm; 薏苡数据来自参考文献[14] (a)黍(Panicum miliaceum),淀粉粒粒径范围5.96-10.99μm,平均粒径8.42μm(n=46);(b)粟(Setaria italica),淀粉粒粒径范围6.23-19.35μm,平均粒径9.32μm(n=55);(c)高粱(Sorghum bicolor),淀粉粒粒径范围9.37-29.52μm,平均粒径18.1μm(n=46);(d-e)薏苡(Coix lacryma-jobi),淀粉粒粒径范围5.48-25.44μm,平均粒径13.5μm(n=240);(f)小麦(Triticum aestivum),淀粉粒粒径范围5.77-31.24μm,平均粒径14.98μm(n=82);(g)大麦(Hordeum vulgare),淀粉粒粒径范围11.29-30.33μm,平均粒径21.82μm(n=49);(h)麻栎(Quercu sacutissima),淀粉粒粒径范围6.90-20.21μm,平均粒径11.13μm(n=62);(i)绿豆(Vigna radiata(L.)Wilczek),淀粉粒粒径范围11.9-52.0μm,平均粒径27.7μm(n=188);(j)红小豆(Vigna angularis(Willd)Ohwi et Ohashi),淀粉粒粒径范围24.6-71.0μm, 平均粒径48.03μm(n=114) Fig.2 Starch grains from some modern plants |

借鉴Piperno等[11]和Perry[12]的实验方法,采用原位置取样法(in situ sampling)。具体步骤为:1)用超纯水彻底洗刷石臼,去除后期保存过程中可能存在的污染并阴干; 2)在臼窝和石臼口部等使用部位和断面(非使用部位)寻找表面较粗糙和有缝隙的地方以确定取样位置,每个位置选取6个取样点; 3)将40μL的超纯水滴到石器取样点,用吸液管的尖端进行搅动; 并用吸液管吸出悬浮的残留物,放到载玻片上,将上述步骤重复一次; 4)在载玻片上的残留物完全自然阴干之前,将一滴甘油和水的混合物(50:50比例)滴到载玻片上,再加盖片并用指甲油封片。

2.2.2 石杵取样方法包括:1)使用超纯水彻底洗刷石杵,去除可能存在的后期污染并阴干。2)石杵的使用部位和非使用部位分别超声,具体过程为: 将烧杯放入超声波清洗仪中; 实验者带上一次性无粉橡胶手套,将石杵的使用部位(研磨端)垂直放入烧杯中,加入超纯水浸没使用部位,超声10分钟,在超声阶段,实验者须手拿石杵避免石杵歪斜; 超声结束后,实验者换上新的一次性无粉橡胶手套,将石杵的非使用部位垂直放入新的烧杯中,加入超纯水浸没未使用端,超声10分钟,在超声阶段,实验者同样手拿石杵避免石杵倾倒。 3)将使用部位和未使用部位超声出的溶液分别转移至新离心管中,加超纯水并以3000rpm离心10分钟清洗,吸出上部浮液并丢弃,重复一次,保留底部残留。 4)用酒精再清洗1次,以3000rpm离心10分钟,吸出上部浮液,保留最底部残留,静置干燥; 用甘油和水的混合液(50:50比例)制片观察。

2.2.3 观察和形态分析使用Olympus X53偏光显微镜观察,首先在200倍下,使用偏光观察并确定淀粉粒的位置,再转至400倍下,分别在透射光和偏光下对淀粉粒的形态、大小、脐点、表面特征以及消光十字等进行观察、记录和拍照; 为了识别提取的淀粉粒,我们收集了来自禾本科、豆科、壳斗科等20多个属50多个种的现代植物种子或果实,对它们的淀粉粒形态开展分析[13],部分现代植物淀粉粒形态见图2。淀粉粒的种属鉴定主要依据我们采集的现代植物淀粉粒形态数据,同时还参考了国内、北美和澳洲的淀粉粒文献[14, 15, 16, 17]。

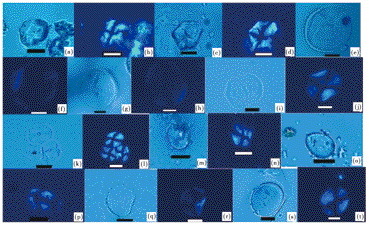

3 实验结果石杵和石臼上共发现淀粉粒90颗,68颗来自石臼,其中51颗来自使用部位,非使用部位(残断面)发现17颗淀粉粒; 2件石杵的使用部位共发现18颗淀粉粒,非使用部位共发现4颗淀粉粒。同一件器物上使用部位和非使用部位残留淀粉粒在数量上存在显著差异,这表明石器使用面上所提取到的淀粉粒应为石器使用过程中的残留。石杵和石臼使用部位共提取到69颗淀粉粒,除去2粒破坏的和14粒特征不明显的淀粉粒,余下53颗按照形态、大小、脐点位置和表面特征等形态学特征,可以分为5类(表1)。

| 表1 望京楼遗址石器使用部位提取到的可鉴定淀粉粒种类和数量 Table 1 The number and types of starch grains from used surfaces of stone tools from Wangjinglou site |

第1类: 25粒,多边形或近圆形,脐点居中,无层纹,部分较大淀粉粒的脐点处有裂隙,多呈Y型或横向线性,粒径分布在6.6-18.2μm(图3a-3d)。多边形的淀粉粒大多来自于禾本科植物种子,如: 粟(Setaria italica)、黍(Panicum miliaceum)、稻(Oryza sativa)、高粱(Sorghum bicolor)、玉米(Zea mays)、薏苡(Coix lacryma-jobi L.)等[18]。其中黍的淀粉粒,平均粒径为8.42μm,粒径范围为5.96-10.99μm,大多表面没有裂隙,只有少数淀粉粒具有穿过脐点的微弱裂隙[13](图2a); 粟的淀粉粒粒径范围为6.23-19.35μm,平均粒径为9.32μm,脐点居中,其中粒径较大的颗粒有穿过脐点的裂隙[13](图2b); 高粱淀粉粒与粟、黍的淀粉粒在粒径和形态上有部分重合,但高粱淀粉粒表面裂隙多呈放射状,且部分有层纹[18](图2c)。第1类淀粉粒表面光滑或有Y型裂隙,因而不应来自高粱,很可能来自粟、黍或者薏苡。这3种植物种子的淀粉粒形态较为接近,但黍的淀粉粒粒径一般不大于12μm,粟以多边形为主,裂隙大多呈Y型,而薏苡淀粉粒部分消光臂弯曲,层纹在透射光下不明显,在偏光下则较为明显(图2d和2e)。综合上述特征,可以确定本类型淀粉粒应主要来自粟,但不排除粒径小于12μm的13粒淀粉粒有可能来自黍。

第2类: 17粒,近圆形或椭圆形,部分淀粉粒透射光下层纹明显,粒径分布在14.8-29.9μm(图3e-3h)。结合我们对小麦族19种植物淀粉粒的分析[13](图2f和图2g),并参照Yang和Perry[19]有关小麦族淀粉粒形态的研究结果,此类淀粉粒符合小麦族淀粉粒的形态特点,应来自小麦族。

|

图3 望京楼遗址石臼、石杵的使用部位提取到的残留淀粉粒(标尺: 10μm) (a-d)第1类,粟黍类淀粉粒(Type 1,Setaria italica and Panicum miliaceum); (e-h)第2类,小麦族淀粉粒(Type 2,Triticeae); (i-l)第3类,薏苡属淀粉粒(Type 3,Coix sp);(m-p)第4类,栎属淀粉粒(Type 4,Quercus sp);(q-t)第5类,豆科淀粉粒(Type 5,Fabaceae) Fig.3 Starch grains from the used surfaces of the mortar and pestles from Wangjinglou site. Scale bar: 10μm |

第3类: 7粒,多边形,透射光下无层纹,个别脐点处有横向线性裂隙,偏光下层纹较为明显,消光臂弯曲,粒径分布范围为13.4-25.1μm(图3i-3l)。此类特征的淀粉粒粒径较大,不应来自粟、黍、水稻,而可能来自薏苡属或者高粱属。但高粱淀粉粒中粒径较大者在透射光下层纹明显(图2c),且薏苡属的淀粉粒多数消光臂呈弯曲状[20](图2d和2e),故本类型淀粉粒应该来自薏苡属。

第4类: 2粒,卵形,消光呈Ⅹ形状,脐点处或有纵向裂隙,粒径分别为14.0μm和14.4μm(图3m-3p)。此类淀粉粒和坚果类淀粉粒形态特征较为一致[21](图2h),很可能来自栎属植物。

第5类:2粒,肾形或椭圆形,肾形淀粉粒的层纹较明显,椭圆形淀粉粒有裂隙,偏光下层纹较明显,粒径均较大,分别为20.1μm和26.2μm(图3q-3t)。豆科很多属植物种子淀粉粒呈椭圆形和肾形,层纹明显,淀粉粒表面有明显裂隙(多数纵向)[13, 22](图2i和图2j)。本类型淀粉粒和豆科植物淀粉粒形态较为一致,应来自豆科植物。

4 讨论粟和黍自新石器时代以来一直是北方农作物体系中最为重要的两种作物,这种状况一直持续到商周时期[23]。二里头遗址[24]、王城岗遗址[25]、南洼遗址[26]和古城寨遗址[27]均发现了二里头文化时期的炭化粟和黍,其绝对数量和出土概率均远高于同遗址出土的小麦和大豆等农作物。此次分析的石杵和石臼上发现有相当数量的粟黍类淀粉粒,表明粟和黍仍是望京楼先民加工的重要农作物。

目前国内最早的小麦遗存发现于龙山文化时期的黄河流域若干遗址,包括上游的甘肃天水西山坪[28]、民乐东灰山[29],中游的河南博爱西金城[30]、禹州瓦店[31]以及洛阳盆地若干中小遗址[32],下游的山东茌平教场铺、胶州赵家庄和日照两城镇等[33]。此时黄河下游的山东地区,小麦的种植已经出现,并且很可能已较为普遍,在农作物中的地位可能已仅次于水稻或粟和黍,重要性应高于大豆类[33]。而黄河中游的中原地区却呈现另一种状况,出土炭化小麦遗存的遗址中,小麦无论是从绝对数量还是出土概率来说,均远低于同遗址出土的大豆遗存[30, 31, 32],而且在其他一些未见小麦遗存的遗址中仍出土有大豆遗存[25],表明龙山文化时期,小麦并不是黄河中游农作物体系中的稳定构成,其重要性远应低于大豆类遗存。但到了二里头文化时期,在南洼[26]、王城岗[25]、洛阳皂角树[34]和二里头遗址[24]中均发现了数量不等的炭化小麦遗存,说明在二里头文化时期小麦已经传入到中原地区的核心地带[35]。望京楼遗址二里头文化石杵和石臼的使用部位发现有来自小麦族的淀粉粒,考虑到二里头文化时期中原腹心地区已普遍发现有炭化小麦遗存,这些淀粉粒来自小麦的可能性很大。这表明在二里头文化时期,小麦也已是望京楼先民重要的利用和加工对象。

橡子在世界上很多地区都曾作为重要的食物资源[36]。我国先民早在旧石器时代晚期即使用磨盘磨棒来加工橡子[37],至全新世早期已经成为人们食物的重要来源,跨湖桥遗址的许多灰坑中就还保存有大量形态完整的栎属果实(橡子)[38]。中原地区属于裴李岗文化的贾湖[39]、班村[40]、莪沟[41]、水泉[42]等遗址中就发现有橡子的炭化遗存。随着原始农业的产生和不断发展,橡子等采集植物在先民食物中的重要性不断降低,但仍然是先民采集食用的重要对象。到了二里头文化时期,五谷农业体系虽已完备,但二里头遗址仍发现有包括蒙古栎在内的坚果以及其他植物果实遗存[24],可见这些植物资源在当时仍被利用。望京楼遗址二里头文化石杵使用部位发现有来自栎属的淀粉粒,表明当时先民确实使用杵和臼等工具加工橡子等坚果以食用。

薏苡在我国有悠久的利用历史,浙江河姆渡遗址就出土过大量的薏苡种子[43],跨湖桥遗址陶器内部就发现有薏米的淀粉粒残留[44]; 裴李岗[45]、孟津寨根和班沟[46]等裴李岗文化遗址的磨盘上都发现有薏苡属淀粉粒。由此可见,史前时期薏苡就已被加工食用。文献中记载的薏苡食用方法是使用舂脱壳取仁煮食[43],此次在望京楼遗址二里头文化时期石臼的使用部位发现有薏苡属的淀粉粒,可以说进一步佐证了文献中对于薏苡食用方法的记载。

豆科植物早至旧石器时代晚期就被加工利用[47],郑州大河村遗址仰韶文化陶罐内就发现有大量炭化的豆科植物种子(野大豆)[48],表明距今6000多年前人类已经开始有意识的储存此类植物种子以食用。二里头文化时期,二里头[24]、皂角树[34]、南洼[26]等遗址均发现有炭化的栽培大豆和其他豆科植物种子。望京楼遗址石臼上发现的豆科淀粉粒并非来自大豆,应来自其他豆科植物。这表明二里头文化时期,豆科植物也是望京楼先民加工的对象之一。

需要指出的是,淀粉粒分析方法作为一种新兴的研究手段[49],还面临诸多问题,如在鉴别区分栽培作物和其野生种方面,淀粉粒分析方法明显不如其他植物考古学研究手段[18]。因此,目前无法判别望京楼石器上发现的薏苡和豆科植物淀粉粒究竟是野生还是栽培,也即无法获知它们究竟来自采集还是种植,这些淀粉粒的发现只能说明望京楼先民确实利用了这两类植物。

5 结论综合以上,可以得出以下结论:

(1)望京楼遗址出土石杵和石臼的淀粉粒分析表明,这批石杵和石臼被用来处理各类植物,包括粟、黍、小麦等农作物以及薏苡、橡子、豆科植物等;

(2)望京楼遗址二里头时期出土石杵和石臼上残留有粟、黍、小麦等农作物淀粉粒,表明二里头文化时期,该遗址农作物品种已经实现多元化; 结合二里头、南洼、皂角树等二里头文化遗址的植物浮选结果,二里头文化时期中原腹心地区确已普遍存在多品种的农作物种植,这种农业经济特点在夏商周文明形成过程中发挥了重要作用[23]。

致谢 诚挚感谢匿名审稿专家和编辑部老师提出的宝贵修改意见。

| [1] | 杨益民. 古代残留物分析在考古中的应用. 南方文物, 2008,(2):20~25 Yang Yimin. Ancient residue analysis and its application in archaeology. Cultural Relics in South China, 2008,(2):20~25 |

| [2] | Barton H, Torrence R, Fullagar R. Clues to stone tool function re-examined:Comparing starch grain frequencies on used and unused obsidian artifacts. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1998, 25:1231~1238 |

| [3] | Briuer F L. New clues to stone tool function:Plant and animal residues. American Antiquity, 1976, 41:478~484 |

| [4] | 马志坤, 杨晓燕, 李泉等. 石器功能研究的现代模拟实验:石刀表面残留物中淀粉粒来源分析. 第四纪研究, 2012, 32(2):247~255 Ma Zhikun, Yang Xiaoyan, Li Quan et al. Stone knife's function:Simulation experiment via starch grain analysis. Quaternary Sciences, 2012, 32(2):247~255 |

| [5] | Torrence R, Barton H. Ancient Starch Research. Walnut Creek:Left Coast Press, 2006. 1~256 |

| [6] | 杨玉璋, 李为亚, 姚凌等. 淀粉粒分析揭示的河南唐户遗址裴李岗文化古人类植物性食物资源利用. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(1):229~239 Yang Yuzhang, Li Weiya, Yao Ling et al. Plant resources utilization at the Tanghu site during the Peiligang culture period based on starch grain analysis, Henan Province. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(1):229~239 |

| [7] | 董珍, 张居中, 杨玉璋等. 安徽濉溪石子山遗址古人类植物性食物资源利用情况的淀粉粒分析. 第四纪研究, 2014, 34(1):114~125 Dong Zhen, Zhang Juzhong, Yang Yuzhang et al. Starch grain analysis reveals the utilization of plant food resources at Shizishan site, Suixi County, Anhui Province. Quaternary Sciences, 2014, 31(1):114~125 |

| [8] | 杨晓燕, 郁金城, 吕厚远等. 北京平谷上宅遗址磨盘、磨棒功能分析:来自植物淀粉粒的证据. 中国科学(D辑), 2009, 39(9):1266~1237 Yang Xiaoyan, Yu Jincheng, Lü Houyuan et al. Starch grain analysis reveals function of grinding stone tools at Shangzhai site, Beijing. Science in China(Series D), 2009, 39(9):1266~1237 |

| [9] | 郑州市文物考古研究院. 河南新郑望京楼二里岗文化城址东一城门发掘简报. 文物, 2012,(9):4~15 Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology of Zhengzhou City. First eastern gate at Erligang cultural site of Wangjinglou, Henan. Cultural Relics, 2012,(9):4~15 |

| [10] | 宋兆麟. 史前食物的加工技术——论磨具与杵臼的起源. 农业考古, 1997,(3):187~195 Song Zhaolin. The technology of food production in Chinese prehistoric period. Agricultural Archaeology, 1997,(3):187~195 |

| [11] | Piperno D R, Ranere A J, Holst I et al. Starch granules reveal early root crop horticulture in the Panamanian tropical forest. Nature, 2000, 407:894~897 |

| [12] | Perry L. Starch analyses reveal the relationship between tool type and function:An example from the Orinoco Valley of Venezuela. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2004, 31:1069~1081 |

| [13] | 陶大卫. 淀粉粒的鉴别和分析及在考古学中的应用. 北京:中国科学院研究生院博士学位论文, 2012. 26~36 Tao Dawei. Identification and Analysis of Starch Grains and Their Applications in Archaeology. Beijing:The Ph.D Thesis of Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Science, 2012. 26~36 |

| [14] | 葛威. 淀粉粒分析在考古学中的应用. 合肥:中国科技大学博士学位论文, 2010. 1~138 Ge Wei. Starch Grain Analysis and Its Application in Archaeology. Hefei:The Ph.D Thesis of University of Science and Technology of China, 2010. 1~138 |

| [15] | Yang X Y, Zhang J P, Perry L et al. From the modern to the archaeological:Starch grains from millets and their wild relatives in China. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2012, 39:247~254 |

| [16] | Henry A G, Brooks A S, Piperno D R et al. Microfossils in calculus demonstrate consumption of plants and cooked foods in Neanderthal diets(Shanidar Ⅲ, Iraq; Spy Ⅰ and Ⅱ, Belgium). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(2):486~491 |

| [17] | Reichert E T. The Differentiation and Specificity of Starches in Relation to Genera, Species, etc. Washington D.C:Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1913. 165~195 |

| [18] | 杨晓燕, 孔昭宸, 刘长江等. 中国北方现代粟、黍及其野生近缘种的淀粉粒形态数据分析. 第四纪研究, 2010, 30(2):364~371 Yang Xiaoyan, Kong Zhaochen, Liu Changjiang et al. Morphological characteristics of starch grains of millets and their wild relatives in North China. Quaternary Sciences, 2010, 30(2):364~371 |

| [19] | Yang X Y, Perry L. Identification of ancient starch grains from the tribe Triticeae in the North China Plain. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2013, 40:3170~3177. |

| [20] | Liu L, Ma S, Cui J X. Identification of starch granules using a two-step identification method. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2014, 52:421~427 |

| [21] | 杨晓燕, 孔昭宸, 刘长江等. 中国北方主要坚果类淀粉粒形态对比. 第四纪研究, 2009, 29(1):153~158 Yang Xiaoyan, Kong Zhaochen, Liu Changjiang et al. Characteristics of starch grains from main nuts in North China. Quaternary Sciences, 2009, 29(1):153~158 |

| [22] | 王强, 贾鑫, 李明启等. 中国常见食用豆类淀粉粒形态分析及其在农业考古中的应用. 文物春秋, 2013,(3):3~11 Wang Qiang, Jia Xin, Li Mingqi et al. Morphological analyses of common edible beans and its application in agricultural archaeology. Stories of Cultural Relics, 2013,(2):3~11 |

| [23] | 赵志军. 关于夏商周文明形成时期农业经济特点的一些思考. 华夏考古, 2005,(1):75~101 Zhao Zhijun. Discussions on the agricultural characteristics of Xia-Shang-Zhou Civilization. Huaxia Archaeology, 2005,(1):75~101 |

| [24] | 中国社会科学院考古研究所. 中国田野考古报告集——二里头(1999-2006). 北京:文物出版社, 2014. 1295~1316 The Institute of Archaeology of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Chinese Field Archaeological Reports——Erlitou:1999-2006. Beijing:Cultural Relics Publishing House, 2014. 1295~1316 |

| [25] | 赵志军, 方燕明. 登封王城岗遗址浮选结果及分析. 华夏考古, 2007,(2):75~89 Zhao Zhijun, Fang Yanming. The results and analysis of the flotation at Wangchenggang site in Dengfeng. Huaxia Archaeology, 2007,(2):75~89 |

| [26] | 吴文婉, 张继华, 靳桂云. 河南登封南洼遗址二里头到汉代聚落农业的植物考古证据. 中原文物, 2014,(1):109~117 Wu Wenwan, Zhang Jihua, Jin Guiyun. Archaeobotanical evidence of the agriculture at Nanwa site from Erlitou to Han Dynasty in Dengfeng, Henan Province. Cultural Relics in Central China, 2014,(1):109~117 |

| [27] | 陈微微, 张居中, 蔡全法. 河南新密古城寨城址出土植物遗存分析. 华夏考古, 2012,(1):54~62 Chen Weiwei, Zhang Juzhong, Cai Quanfa. The analysis of plant remains at Guchengzhai site in Xinmi, Henan Province. Huaxia Archaeology, 2012,(1):54~62 |

| [28] | Li X Q, Dodson J, Zhou X et al. Early cultivated wheat and the broadening of agriculture in Neolithic China. The Holocene, 2007, 17(5):555~560 |

| [29] | Rowan F, Li S C, Wu X H et al. Early wheat in China:Results from new studies at Donghuishan in the Hexi Corridor. The Holocene, 2010, 20(6):955~965 |

| [30] | 陈雪香, 王良智, 王青. 河南博爱县西金城遗址2006-2007年浮选结果分析. 华夏考古, 2010,(3):67~76 Chen Xuexiang, Wang Liangzhi, Wang Qing. The analysis of the flotation at Xijincheng site from 2006 to 2007 in Bo-ai, Henan Province. Huaxia Archaeology, 2010,(3):67~76 |

| [31] | 刘昶, 方燕明. 河南禹州瓦店遗址出土植物遗存分析. 南方文物, 2010,(4):55~64 Liu Chang, Fang Yanming. The analysis of plant remains at the Wadian site in Yuzhou, Henan. Cultural Relics in South China, 2010,(4):55~64 |

| [32] | 张俊娜, 夏正楷, 张小虎. 洛阳盆地新石器-青铜时期的炭化植物遗存. 科学通报, 2014, 59(34):3388~3397 Zhang Junna, Xia Zhengkai, Zhang Xiaohu. Research on charred plant remains from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age in Luoyang basin. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2014, 59(34):3388~3397 |

| [33] | 靳桂云. 中国早期小麦的发现与研究. 农业考古, 2007,(4):11~20 Jin Guiyun. The discoveries and researches of the wheat in China. Agricultural Archaeology, 2007,(4):11~20 |

| [34] | 洛阳市文物工作队编. 洛阳皂角树——1992-1993年洛阳皂角树二里头文化聚落遗址发掘报告. 北京:科学出版社, 2002. 1~166 Luoyang Cultural Relics Work Team. Luoyang Zaojiaoshu——The Excavation Report of the Erlitou Cultural Settlement Site in Luoyang from 1992 to 1993. Beijing:Science Press, 2002. 1~166 |

| [35] | 赵志军. 中国古代农业的形成过程——浮选出土植物遗存证据. 第四纪研究, 2014, 34(1):74~84 Zhao Zhijun. The process of origin of agriculture in China:Archaeological evidence from flotation results. Quaternary Sciences, 2014, 34(1):74~84 |

| [36] | Mason S R. Acorns in Human Subsistence. London:The Ph.D Thesis of University College London, 1992. 61~99 |

| [37] | Liu L, Ge W, Bestel S et al. Plant exploitation of the last foragers at Shizitan in the middle Yellow River Valley China:Evidence from grinding stones. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38(12):3524~3532 |

| [38] | 浙江省文物考古研究所, 萧山博物馆. 跨湖桥. 北京:文物出版社, 2004年. 271~272 Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Xiaoshan Museum. Zhejiang Kuahuqiao. Beijing:Cultural Relics Publishing House, 2004. 271~272 |

| [39] | 赵志军, 张居中. 贾湖遗址2001年度浮选结果分析报告. 考古, 2009,(8):84~93 Zhao Zhijun, Zhang Juzhong. The analysis report of the floatation at Jiahu site. Archaeology, 2009,(8):84~93 |

| [40] | 孔昭宸, 刘长江, 张居中. 渑池班村新石器遗址植物遗存及其在人类环境学上的意义. 人类学学报, 1999, 18(4):291~295 Kong Zhaochen, Liu Changjiang, Zhang Juzhong. Plant remains in the Neolithic site of Bancun and their significance for the human environment. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 1999, 18(4):291~295 |

| [41] | 河南省博物馆, 密县文化馆. 河南密县莪沟北岗新石器时代遗址发掘报告. 河南文博通讯, 1979,(3):30~41 Henan Provincial Museum, House of Culture of Mi County. The excavation report of the Neolithic site of E'gou Beigang in Mi County, Henan Province. Bulletin of Cultural Relics and Museums in Henan Province, 1979,(3):30~41 |

| [42] | 中国社会科学院考古研究所河南一队. 河南郏县水泉裴李岗文化遗址. 考古学报, 1995,(1):39~77 Institute of Archaeology of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The Peiligang culture site of Shuiquan in Xia County, Henan Province. Acta Archaeologica Sinica, 1995,(1):39~77 |

| [43] | 俞为洁, 徐耀良. 河姆渡文化植物遗存的研究. 东南文化, 2000,(7):24~32 Yu Weijie, Xu Yaoliang. Research on the plant remains of Hemudu Culture. Culture in Southeast China, 2000,(7):24~32 |

| [44] | 杨晓燕, 蒋乐平. 淀粉粒分析揭示浙江跨湖桥遗址人类的食物构成. 科学通报, 2010, 55(7):596~602 Yang Xiaoyan, Jiang Leping. Starch grain analysis reveals ancient diet at Kuahuqiao site, Zhejiang Province. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2010, 55(7):596~602 |

| [45] | 张永辉, 翁屹, 姚凌等. 裴李岗遗址出土石磨盘表面淀粉粒的鉴定与分析. 第四纪研究, 2011, 31(5):891~899 Zhang Yonghui, Weng Yi, Yao Ling et al. Identification and analysis of starch grains on the surfaces of the slabs from Peiligang site. Quaternary Sciences, 2011, 31(5):891~899 |

| [46] | 刘莉, 陈星灿, 赵昊. 河南孟津寨根、班沟出土裴李岗晚期石磨盘功能分析. 中原文物, 2013,(5):76~86 Liu Li, Chen Xingcan, Zhao Hao. Functional analysis of grinding stones at the late Peiligang cultural sites of Zhaigen and Bangou in Mengjin, Henan. Cultural Relics in Central China, 2013,(5):76~86 |

| [47] | Liu L, Bestel S, Shi J M et al. Paleolithic human exploitation of plant foods during the Last Glacial Maximum in North China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2010, 110(14):5380~5385 |

| [48] | 刘莉, 盖瑞克劳福德, 李炅娥等. 郑州大河村遗址仰韶文化高粱遗存的再研究. 考古, 2012,(1):91~96 Liu Li, Crawford G, Lee G et al. Re-analysis of the sorghum remains at the Yangshao Cultural site of Dahecun, Zhengzhou City. Archaeology, 2012,(1):91~96 |

| [49] | 郑齐, 王灿. 糯性植物用于北京古北口明长城建筑粘合剂的淀粉粒证据. 第四纪研究, 2013, 33(3):575~581 Zheng Qi, Wang Can. Starch evidence of glutinous plant content as the additive to Ming Great Wall mortar at Gubeikou, Beijing. Quaternary Sciences, 2013, 33(3):575~581 |

② Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology of Zhengzhou, Zhengzhou 450005)

Abstract

Wangjinglou site(34°26'42.6"N,113°43'25.4"E; 119m a.s.l.) is located in Xincun Town, Xinzheng City, Henan Province.Two city settlements were discovered at this site, one of which belonged to Erlitou Culture and the other belonging to Erligang Culture.The city remains which belonged to Erlitou Culture was an important finding in the core area of Central Plains.Ancient starch residue analysis of stone tools from Wangjinglou site can provide us the information of plant resources utilization and the tool function during the Erlitou Culture period.

In this paper, three stone tools including one damaged mortar and two intact pestles from Wangjinglou site which belonged to Erlitou Culture were selected for starch grain analysis.90 starch grains were extracted from these three tools and 69 of them were from the used surfaces of the tools, 51 of which were from the used surface of the mortar.2 of the starch grains from the used surfaces show the characteristics of damage and another 14 also cannot be identified due to absence of diagnostic features.The others were classified into 5 types.Type 1 starch grains(N=25) are polygonal and have centric hilum, no lamellae with clear extinction cross.These starch grains are consistent with the starch grains from foxtail millet or common millet in size and features, and therefore they were identified as millets.Type 2 starch grains(N=17) are lenticular/discoid or spherical in shape and have a bimodal distribution in size.The size range is wide, which is from 14.8μm to 29.9μm.A bimodal size distribution of large and small granules is characteristic of starch grain from Triticeae.Type 2 starch grains show best matches to the tribe Triticeae.Type 3 starch grains(N=7) are polygonal and have centric hilum with bigger sizes, which fall into the size range of Sorghum or Coix. These grains have Z-shaped arm on the extinction cross which was a diagnostic feature of Job's tears.So Type 3 was possibly from Coix sp.Type 4(N=2) are characterized by lenticular or oval shapes, one of which has a longitudinal fissure across the hilum with a plane view.These diagnostic features are consistent with Quercus. Type 5(N=2) are kidney or oval shape, which have lamellae or fissures on the surface.They show best matches to the starch grains from Fabaceae.

Diversity of starch grains in morphological characteristics extracted from the stone tools indicates that a variety of starchy plants, including millets, Triticeae grasses, Coix, acorns and Fabaceae, were processed by the inhabitants at Wangjinglou site.Meantime, combined with macro-botanical evidences from Erlitou, Nanwa, and Zaojiaoshu et al., starch grain analysis of the tools from Wangjinglou site indicates that the cultivation of different cereals were carried out in the core area of Central Plains during the Erlitou Culture period.

2016, Vol.36

2016, Vol.36