The article information

- Uddin M.S., Pham Binh, Sarhan Ahmed, Basak Animesh, Pramanik Alokesh

- Comparative study between wear of uncoated and TiAlN-coated carbide tools in milling of Ti6Al4V

- Advances in Manufacturing, 2017, 5(1): 83-91.

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40436-016-0166-1

-

Article history

- Received: 20 July, 2016

- Accepted: 19 December, 2016

- Published online: 18 February, 2017

2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

3 Adelaide Microscopy Unit, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia

4 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Curtin University of Technology, Bently, WA 6845, Australia

Due to their excellent strength to weight ratio, toughness at high temperature, and corrosion resistance, titanium alloys (e.g., Ti6Al4V) have attracted tremendous attention and been extensively applied as structural components in aerospace and biomedical industries [1, 2]. Machining as a mechanical processing technique has been one of fast and effective operations in manufacturing to provide the final shape of such components with required geometric accuracy and finish. However, the key challenge is the difficulty to cut or shape titanium alloy materials due to their very low thermal conductivity [3]. As a result, a high temperature is generated at the cutting zone, which affects the cutting tool life (i.e., wear performance) and surface integrity of the final product. In the past, different types of cutting tool materials along with combinations of various cutting parameters and environments have been investigated in cutting of titanium alloys. The cutting tools studied are made of carbide, high-speed steel (HSS), diamond, while cutting speed and feed rate have been the dominating parameters influencing the machinability of titanium alloys [4, 5]. A common consensus in evaluating the machinability is that the cutting tool wear is the major factor, affecting the manufacturing productivity as a result of the underlying interaction and mechanics between the tool and the workpiece. Among many tools, tungsten carbide has been a good choice and widely used cutting tool in the machining industries due to its high strength and wear resistance [6]. The carbide tools are made of tungsten carbide (WC) with cobalt (Co) binders via compacting and sintering, making the material hard and resilient to heat and wear [7]. The composition of WC-Co is often varied to produce the tool with required mechanical and tribological properties. While diamond tools (e.g., polycrystalline diamond (PCD)) offer relatively improved machining performance in terms of tool life, they are quite expensive and may not be affordable for mass manufacturing [8, 9]. As a result, tungsten carbide has shown tremendous potential in high speed cutting of titanium alloys. Over the years, carbide tools have been studied in cutting of titanium alloys with a focus on understanding of wear and the associated wear mechanisms [10, 11]. In the cutting of non-ferrous metals, abrasion, adhesion, attrition and diffusion are shown to be typical wear mechanisms, of which adhesion and diffusion are often cited as the dominating effects, particularly, when machining of titanium. Ghani et al. [12] studied the effects of various high cutting speeds (120-135 m/min) on carbide tool wear in the cutting of titanium and reported that higher speed caused brittle fracture and cracking of the tool edge due to high temperature induced stress concentration and intermittent fast thermal loading. They recommended suitable conservative cutting parameters to minimize tool wear effects. Hartung et al. [13] showed that crater wear due to adhesive layers on the rake face was more dominant at lower cutting speeds (61-122 m/min), while the tool failed due to plastic deformation at high cutting speeds (122-610 m/min). Adhesive layers are formed due to the chemical reaction between titanium and carbide particles via diffusion, which essentially decreases the toughness of the tool edge. Generally, different tool materials behave differently according to different wear mechanisms. In this regard, hard and wear resistant coatings, e.g., TiN, TiCN, are applied to the tool edge to improve the performance. Surprisingly, Ezugwu and Wang [14] found that the uncoated tool outperformed the coated tool in cutting of titanium. This finding was contradictory to the findings of other researchers [15]. Wear due to the elemental diffusion-dissolution through the tool-chip of carbide tools at high cutting speeds was further emphasized in Ref. [16]. In a dry cutting of titanium alloy, Gerez et al. [17] observed that an adhesive layer or built up edge generated at low cutting speeds often acted as a lubricant, minimizing abrasion. However, the layers were momentarily removed at high cutting speeds, hence accelerating abrasion at the tool-rake interface.

Therefore, it is clear that insightful understanding of the wear development and mechanisms is becoming more important to determine the limit of the tool capability, enabling one to predict the onset of generation of degraded surface due to a worn-out/failed cutting edge of the tool. This understanding also allows one to design and develop better cutting tool materials. The importance of the effect of tool wear on the machinability is stressed by a wider community of machining researchers [4, 18].

Keeping this spirit in mind, this paper focuses on further investigation and analysis of the wear and wear mechanisms of uncoated and TiAlN-coated tungsten carbide tools in cutting of Ti6Al4V alloys in dry conditions. To follow up and measure consistent wear development, a series of side milling operations with the same cutting parameters were performed. Cutting edge wear, surface roughness and chips were observed and measured at a certain interval of cutting distance (often noted as cutting time). The results are discussed and analyzed with respect to the findings available in the literature.

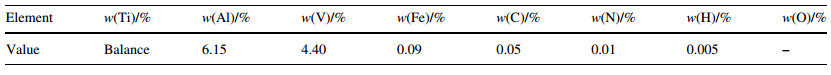

2 Experimental details 2.1 WorkpiecesThe machining was conducted on the workpieces made of Ti6Al4V alloys. The chemical compositions and mechanical properties of the material are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The as-received material block was cut into a size of 100 mm × 100 mm × 80 mm (L × W × H). The top and bottom surfaces of the specimen were further rough machined with a very shallow cut to clean and even out the surfaces. This process used a 60 mm diameter solid carbide indexed cutter running with a feed rate of 500 mm/min and a spindle speed of 1 200 r/min.

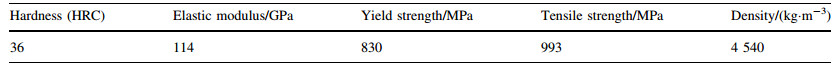

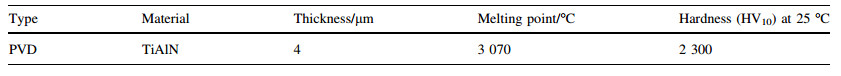

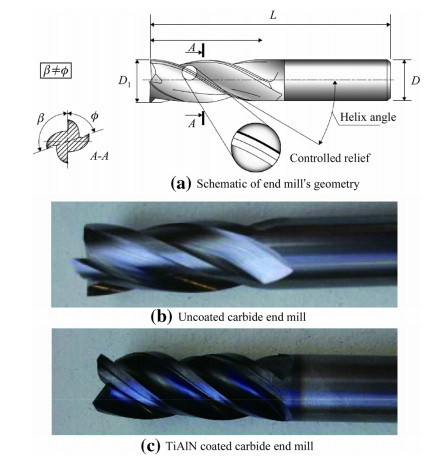

As cutters, two types of tungsten carbide end mills are used. One is uncoated (Hanita D014 supplied by Wahida Inc., Japan) and the other is coated with TiAlN via physical vapor deposition (PVD) method (KCPM 15 is supplied by Kennametal Inc., USA). The geometric dimension of both cutters is as follows: diameter D1=12 mm, number of flutes=4, total length L=83 mm, working length l=26 mm, helix angle=30°, axial rake angle=6° and secondary clearance angle=15°. Figure 1 shows photographs of both the coated and uncoated carbide cutters used. The physical and mechanical properties of the tungsten carbide and TiAlN-coated tools are summarized in Tables 3 and 4. Before actual cutting tests, the edges of the cutters are observed to be sharp and clean without any dirt.

|

| Fig. 1 Tungsten carbide end mills used in the tests |

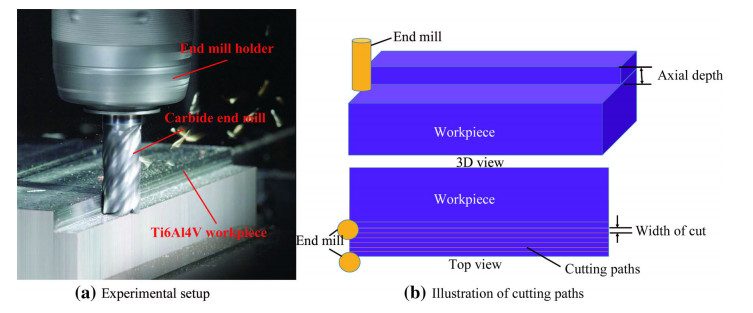

Using a CNC 4-axis vertical milling machine (Bridgeport's VMC 480PS, USA), a series of side milling operations were performed on the workpiece. Figure 2 depicts experimental setup and illustration of cutting paths considered during tests. As titanium alloy is hard and difficult to machine, higher cutting speed and feed rate are considered. The cutting parameters used are as follows: cutting speed v=80 m/min, feed rate f=0.2 mm/r, width of cut d=1 mm. During machining, the cutter was engaged with the workpiece at 10 mm depth along the tool axis direction, i.e., axial depth was 10 mm (see Fig. 2). The cutting conditions were kept constant for machining with both types of cutters. In order to understand the tool wear performance, the cutter was observed at a certain interval of the cutting length. To do this, the cutter was taken out of the spindle head and the tool holder, and examined under microscopes. A cutting length interval of 1 m was considered for the uncoated cutter while a cutting length of 2 m was used for the coated cutter. As it is expected that the coated one will experience less wear as the cutting progresses. The flank wear and wear mechanism were observed, measured and recorded by an optical microscope equipped with high resolution camera (Wild Heedbrugg's Wild M20, V=1.4X, Switzerland). Cutting chips were collected to understand and observe the effect of tool wear on the change of temperature in cutting zone. The topology of the tool, machined surface and chips were further observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (FEI's Quanta 450 equipped with EDX capability, Netherlands). The process was repeated until the cutters reached closer to failure (i.e., average VB=0.3 mm) according to the failure criterion [19]. Note that the notation VB was generally defined as the height of the flank wear region of the cutting tool. All the machining was performed in dry environment without using any external coolant or lubricant. In addition to wear, the arithmetic average roughness (Ra) of the machined surface was measured by a roughness tester (Mitutoyo's Surftest SJ-210, cut-off length 2.5 mm, contact mode, stylus tip radius 5 μm, JIS-B0601 standard, Japan). The roughness values on five locations of the surface were measured and their average was considered. The same experimental procedure was followed for the cutting tests with both uncoated and TiAlN-coated tungsten carbide cutters.

|

| Fig. 2 Experimental setup and cutting paths used in milling tests |

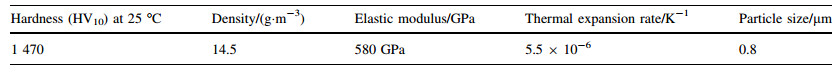

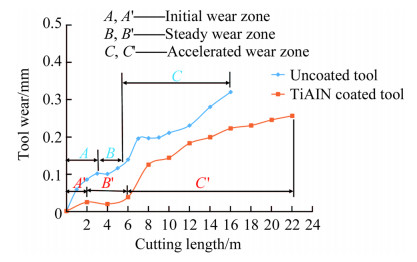

The main focus is to investigate the tool wear and wear mechanism associated with machining titanium alloy. In general, the cutting tests continue until the tool reaches a standard failure criterion, i.e., average flank wear is 0.3 mm for carbide tool. Figure 3 depicts a comparison of the tool flank wear progression with respect to the cutting length for the uncoated and coated tools. It can be seen from Fig. 3 that, as the cutting length increases, TiAlN-coated carbide tool exhibits a lower wear than the uncoated tool. For instance, after a cutting of 10 m, the coated tool reaches a wear value of 0.143 6 mm, which is about 32% smaller than that of the uncoated tool wear (0.21 mm). The coated tool can cut up to 22 m in length with wear progression of about 0.23 mm, while the uncoated tool reaches wear of about 0.321 mm (i.e., failure criterion) at a shorter cutting distance of 16 m. Overall, the coated tool, generally after a cutting of 16 m, shows an enhancement of tool life by about 44% over that of its counterpart. Further, a cutting tool generally follows a three region wear characteristics: initial wear zone with relatively high wear, steady state wear region and accelerated wear region leading to failure [20]. As shown in Fig. 3, both the uncoated and coated tools show approximately three wear zones as indicated by the A-B-C and A'-B'-C' areas, respectively. The initial wear rate of the uncoated tool is larger than that of the coated tool as the slope of the curve in A zone is shown to be relatively high. Further, the steady state wear region for the uncoated tool starts after about a cutting distance of 3.5 m, while for the coated tool it starts after cutting of 2 m. The stability of the region is longer than that of the uncoated one. This comparison indicates that the TiAlN-coated tool exhibits a better tool life or wear resistance and can be safely used for a greater cutting length in machining of titanium alloys. Moreover, the findings are consistent with those of other researchers [21, 22].

|

| Fig. 3 Comparison of the uncoated and TiAlN-coated tool wear progress as a function of cutting length |

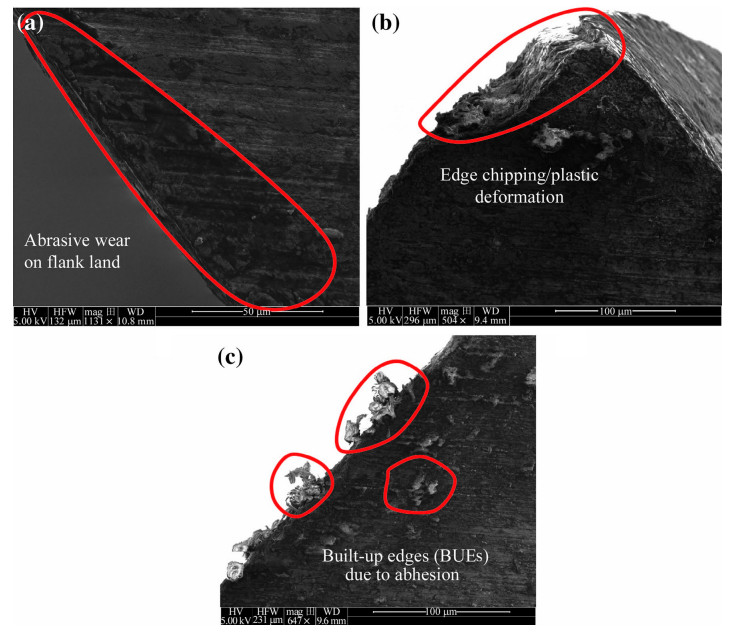

In order to evaluate the machining performance of the cutting tools, an understanding of the underlying wear mechanisms is essential. The wear and wear mechanism vary with the combination and interaction of the cutting tool and the workpiece, in addition to the cutting environment. As titanium is hard material, the wear mechanisms that influence the failure of carbide tools may be different from those when machining other materials. As a representative example, Fig. 4a shows SEM images of the flank wear land of the uncoated tool after a cutting of 16 m. A large abrasive wear region along the cutting edge is observed on the uncoated tool. As the wear increases, the onset of tool failure is initiated by small edge chipping and/ or plastic deformation as seen in Fig. 4b. This chipping is due to the increased friction because of wear causing thermal stress at the edge. Built up edges (BUEs) due to adhesion between the tool and the workpiece materials are noticed on the cutting edge and flank region (see Fig. 4c), which are expected to potentially further accelerate abrasion and friction between the tool and workpiece, and result in increased wear.

|

| Fig. 4 Wear in uncoated carbide tool at a cutting length of 16 m a abrasion on flank land b chipping/plastic deformation on cutting edge c BUEs |

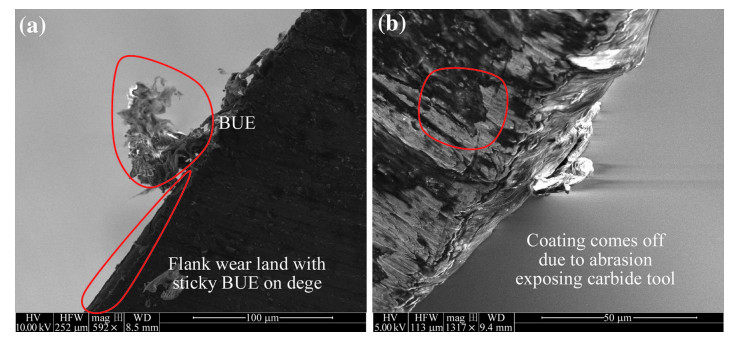

For the same cutting distance, the cutting edge of the coated tool appears to be very smooth with very small or minor wear marks on the flank land, as shown in Fig. 5a. The observed gradual flank wear can be due to the increased wear resistance of the TiAlN coating during continuous abrasion of the tool with the workpiece. Similar progressive wear on the flank region for the coated tool in cutting of titanium was reported by Dhar et al. [21]. No significant chipping and fracture on the cutting edge were observed. But, similar to uncoated one, sticky BUEs are noticed on the cutting edge. However, it is notable that the coating on the cutting edge appears to come off due to the continuous abrasion between the workpiece (including BUE) and the tool (see Fig. 5b). As reported by König et al. [23], accelerated adhesion took place after the coating had been removed due to prolonged cutting. In such a case, the adhered material was hit and squashed by the tool in the event of re-entry into the workpiece, resulting in chipping and eventually leading to the breakage of carbide at the cutting edge. The adhering metal was often noticed on the flank face rather than on the rake face. This finding clearly supports our observation and analysis on the wear and wear mechanism of the uncoated and coated carbide tools.

|

| Fig. 5 Wear in TiAlN coated carbide tool at a cutting length of 16 m a flank wear with BUEs b removal of coating due to abrasion |

In this study, we employed a single set of relatively conservative-medium cutting conditions (speed of 80 m/min, feed rate of 0.1 mm/r), and no severity of the tool damage or failure was noticed for the coated tool even after a cutting of 22 m. However, at a cutting speed of more than 100 m/min, cutting edge cracking and brittle fracture due to high stress concentration because of high temperature are often regarded as the major reasons for tool failure [15]. This phenomenon has been reiterated and observed by many researchers [10, 11, 24]. In particular, Ghani et al. [12] recently reported that cutting titanium at a speed of 120-135 m/min was likely to induce high temperature at the cutting edge, which weakened the micro-bonding between the carbide particles and their binders, thus resulting in early brittle fracture at the nose of the tool.

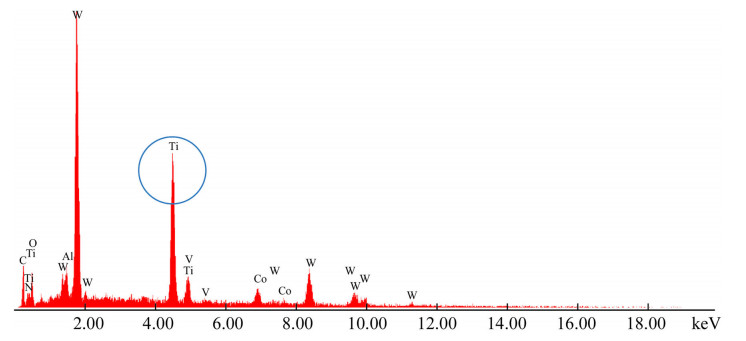

As seen in Fig. 5b, the TiAlN coating is expected to be diffused and removed from the cutting edge. Thus, the part of the tool which is engaged with the workpiece becomes uncoated causing the tungsten carbide to be exposed at the cutting zone. This suggestion can be further supported by the presence of fairly large amount of Ti on the tool edge detected by EDX and illustrated in Fig. 6. Diffusion of the coating materials into the workpiece/chips resulting in tool failure has been reported by researchers. In an extensive study by Odelros [25], EDX analysis revealed a high content of Ti in the particles that adhered to the cutting tool, indicating that the detected Ti content was due to the underlying chemical reaction between the coating material and titanium alloy. It is notable that these adhered layers of materials (often termed as BUE) cause furthur abrasion between the tool and cutting chips/workpiece, hence resulting in accelerated wear on the flank face of the tool. Similar wear mechanisms with an extensive EDX analysis of chemical compositions and their diffusions of BUE materials in the cutting of titanium alloys were reported in Ref. [26]. Note that, in this study, the crater wear region is not of interest as at low cutting speed, flank wear is often regarded as the dominant indicator of tool wear performance [10].

|

| Fig. 6 EDX analysis of the elements on the coated tool surface |

In a dry cutting, reduction of cutting induced temperature is essential to sustain tool life. While the use of cutting lubricants and coolants is found for certain extent, the design of heat and wear resistant tool material with low friction needs to be developed to minimize the cutting temperature. In addition, proper choice of cutting parameters including cutting speed and feed rate, which are shown to be the most dominating factors in influencing the tool failure, needs to be sought in order to improve the machinability of titanium alloys.

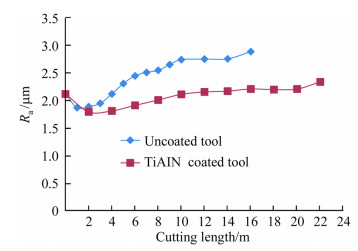

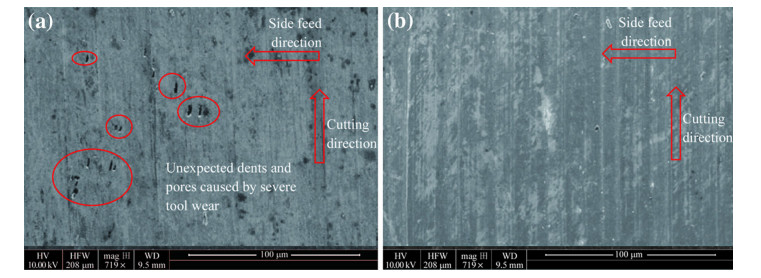

3.3 Surface roughness and cutting chipsThe surface roughness and cutting chips were investigated as a measure of the tool performance. Figure 7 illustrates roughness average of machined surface for uncoated and coated tools with respect to the cutting length. It can be seen that at a cutting distance of up to 2 m, the uncoated and coated tools exhibit almost the same roughness (Ra=1.88 μm). After this, the uncoated tool shows a drastic increase in roughness as compared to the coated tool as the cutting length increases. For instance, at a cutting length of 16 m, the roughness for the coated tool is about 31% lower than that for the uncoated tool. It is to be pointed that the larger roughness with the uncoated tool is due to severe flank wear on the cutting edge, as observed in Fig. 4. Wear further causes large cutting forces, hence accelerating development of micro fracture and chipping at the cutting edge, and as a result of this, an uneven machined surface is generated [27]. Figure 8 shows SEM images of machined surface topology for the uncoated and coated tools at a cutting distance of 16 m. The uncoated tool reveals some unexpected dents and dirt on the surface, causing a larger roughness (Ra=2.89 μm). On the other hand, the surface machined and the coated tool appears to be relatively smooth with fine cutting marks with a roughness of Ra=2.21 μm. The results clearly indicate that, in addition to prolonged tool life, the TiAlN-coated tool is able to generate improved surface quality.

|

| Fig. 7 Comparison of surface roughness between uncoated and TiAlN-coated tools |

|

| Fig. 8 SEM photos of machined surface topology at a cutting distance of 16 m for a uncoated tool and b TiAlN coated tool |

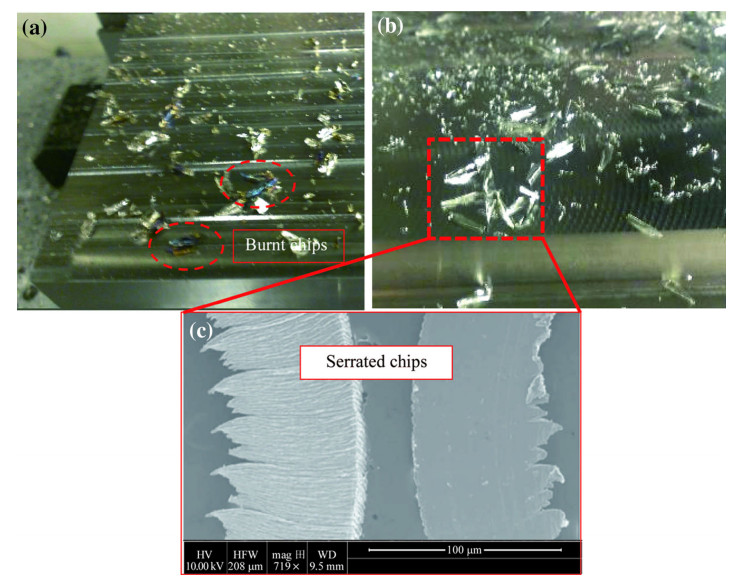

Further, cutting chips or swarf generated at the cutting zone were collected and observed by optical microscopy. Figure 9 shows the chips generated by uncoated and TiAlN-coated tools at a cutting distance of 16 m. More discontinuous and fracture chips are noticed for the uncoated tool (see Fig. 9a). Further, burnt chips with blue color are observed, which could be due to the heat generated at the cutting zone of the blunted tool due to wear. On the other hand, the coated tool generates fairly continuous and unbroken chips (see Fig. 9b). Interestingly, chips generated by both tools appear to be of the saw tooth or serrated type, as shown in Fig. 9c. Mechanisms and modelling of serrated chips generated during cutting of titanium alloys were widely reported and confirmed by many research works in Refs. [28-31]. It is shown that the small initial chip thickness and large rake angle affect the generation and geometry of regular serrated chips [32]. While the initial thickness is related to the feed rate to be chosen, the actual chip thickness during the cutting can be affected by the cutting edge of the associated tool. Therefore, it is possible that the severe tool wear at the cutting edge may influence the geometry of the serrated chips. Hence, in order to minimize the serrated chipping, the tool wear must be regulated to an acceptable level without sacrificing machining productivity. With this aim, one possible solution is to develop a predictive model of the energy efficient machining of titanium alloys by controlling inherent cutting temperature and vibration generated [33], which will allow the optimum machining conditions including cutting parameters to be chosen to enhance the tool life.

|

| Fig. 9 Optical microscopic photos of chips formed by a uncoated tool, b TiAlN coated tool at a cutting length of 16 m and c magnified SEM photo of the chips |

This paper has focused on an investigation and comparison of the wear progression and wear mechanism of uncoated and TiAlN coated tungsten carbide tools in high speed cutting of Ti6Al4V alloy. The followings are the key conclusions drawn from this study.

(ⅰ) The TiAlN coated tool exhibits improved tool life with approximately 44% lower flank wear than the uncoated tool at a cutting distance of 16 m.

(ⅱ) A more regular progressive abrasion between the flank face of the tool and workpiece is found. The underlying wear mechanism and small edge chipping and/or plastic deformation for prolonged cutting are noticed for the uncoated tool.

(ⅲ) Diffusion as a form of BUEs due to the chemical reaction between the coating and the workpiece materials at high cutting temperature is shown to cause the removal of coating from the tool, and weakez the cutting edge, which may result in further acceleration of potential failures.

(ⅳ) The TiAlN coated tool generates smooth machined surface with 31% lower roughness over the uncoated tool. As is expected, both tools generate the serrated chips. However, burnt chips with blue colour are noticed for the uncoated tool as the cutting continues further.

Acknowledgements The authors like to thank Adelaide Microscopy Unit of University of Adelaide for their support in using SEM and EDX for observation of cutting tools and machined surfaces.| 1. | Arrazola PJ, Garay A, Iriarte LM, et al(2009) Machinability of titanium alloys (Ti6Al4V and Ti555.3). J Mater Process Technol 209(5), 2223-2230 doi:10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2008.06.020 |

| 2. | Niknam SA, Khettabi R, Songmene V (2014) Machinability and machining of titanium alloys:a review. In:Davim JP (ed) Machining of titanium alloys. Springer, Berlin, pp 1-30 |

| 3. | Nouari M, Makich H(2014) On the physics of machining titanium alloys:interactions between cutting parameters, microstructure and tool wear. Metals 4(3), 335-358 doi:10.3390/met4030335 |

| 4. | Arsecularatne JA, Zhang LC, Montross C(2006) Wear and tool life of tungsten carbide, PCBN and PCD cutting tools. Int J Mach Tools Manuf 46(5), 482-491 doi:10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2005.07.015 |

| 5. | Zareena AR, Veldhuis SC(2012) Tool wear mechanisms and tool life enhancement in ultra-precision machining of titanium. J Mater Process Technol 212(3), 560-570 doi:10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2011.10.014 |

| 6. | Santhanam T, Tierney P, Hunt JL (1990) Properties and selection:nonferrous alloys and special-purpose materials, vol 2, 10th edn. Kennametal Inc, Latrobe |

| 7. | Egashira K, Hosono S, Takemoto S, et al(2011) Fabrication and cutting performance of cemented tungsten carbide micro-cutting tools. Precis Eng 35(4), 547-553 doi:10.1016/j.precisioneng.2011.06.002 |

| 8. | Su HH, Liu P, Fu Y, et al(2012) Tool life and surface integrity in high-speed milling of titanium alloy TA15 with PCD/PCBN tools. Chin J Aeronaut 25(5), 784-790 doi:10.1016/S1000-9361(11)60445-7 |

| 9. | Li A, Zhao J, Wang D, et al(2012) Failure mechanisms of a PCD tool in high-speed face milling of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 67(9-12), 1959-1966 |

| 10. | Jawaid A, Sharif S, Koksal S(2000) Evaluation of wear mechanisms of coated carbide tools when face milling titanium alloy. J Mater Process Technol 99(1-3), 266-274 doi:10.1016/S0924-0136(99)00438-0 |

| 11. | Bhatt A, Attia H, Vargas R, et al(2010) Wear mechanisms of WC coated and uncoated tools in finish turning of Inconel 718. Tribol Int 43(5-6), 1113-1121 doi:10.1016/j.triboint.2009.12.053 |

| 12. | Ghani J, Che HCH, Hamdan SH, et al(2013) Failure mode analysis of carbide cutting tools used for machining titanium alloy. Ceram Int 39(4), 4449-4456 doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2012.11.038 |

| 13. | Hartung PD, Kramer BM, von Turkovich BF(1982) Tool wear in titanium machining. CIRP Ann Manuf Technol 31(1), 75-80 doi:10.1016/S0007-8506(07)63272-7 |

| 14. | Ezugwu EO, Wang ZM(1997) Titanium alloys and their machinability-a review. J Mater Process Technol 68(3), 262-274 doi:10.1016/S0924-0136(96)00030-1 |

| 15. | Ginting A, Nouari M(2006) Experimental and numerical studies on the performance of alloyed carbide tool in dry milling of aerospace material. Int J Mach Tools Manuf 46(7-8), 758-768 doi:10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2005.07.035 |

| 16. | Deng JX, Li YS, Song WL(2008) Diffusion wear in dry cutting of Ti-6Al-4V with WC/Co carbide tools. Wear 265(11-12), 1776-1783 doi:10.1016/j.wear.2008.04.024 |

| 17. | Gerez JM, Sanchez-Carrilero M, Salguero J, et al(2009) A SEM and EDS based study of the microstructural modifications of turning inserts in the dry machining of Ti6Al4V alloy. AIP Conf Proc 1181, 567-574 |

| 18. | Pramanik A, Islam MN, Basak A, et al(2013) Machining and tool wear mechanisms during machining titanium alloys. Adv Mater Res 651, 338-343 doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.651 |

| 19. | Zhang S, Li JF, Sun J, et al(2009) Tool wear and cutting forces variation in high-speed end-milling Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 46(1-4), 69-78 |

| 20. | Astakhov VP, Davim JP (2008) Tools (geometry and material) and tool wear-Springer. In:machining:fundamentals and recent advances. Springer, Berlin, pp 25-57 |

| 21. | Dhar NR, Islam S, Kamruzzaman M, et al(2006) Wear behavior of uncoated carbide inserts under dry, wet and cryogenic cooling conditions in turning C-60 steel. J Braz Soc Mech Sci Eng 28(2), 146-152 doi:10.1590/S1678-58782006000200003 |

| 22. | Sharif S, Abd E, Sasahar H (2012) Machinability of titanium alloys in drilling. In:Amin AKMN (ed) Titanium alloys-towards achieving enhanced properties for diversified applications. InTech, Osaka |

| 23. | König W, Fritsch R, Kammermeier D (1991) Physically vapor deposited coatings on tools:performance and wear phenomena. In:metallurgical coatings and thin films. Elsevier, Oxford, pp 316-324 |

| 24. | Zhang Y, Zhou Z, Wang J, et al(2013) Diamond tool wear in precision turning of titanium alloy. Mater Manuf Process 28(10), 1061-1064 doi:10.1080/10426914.2013.773018 |

| 25. | Odelros S (2012) Tool wear in titanium machinin. Dissertation, Uppasla University, Uppasla |

| 26. | Bai Q (2014) Interactions between wear mechanisms in a WCCo/Ti-6Al-4V machining tribosystem. Dissertation, Texas A&M University, USA |

| 27. | Che-Haron CH, Jawaid A(2005) The effect of machining on surface integrity of titanium alloy Ti-6% Al-4% V. J Mater Process Technol 166(2), 188-192 doi:10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2004.08.012 |

| 28. | Bermingham MJ, Palanisamy S, Dargusch MS(2012) Understanding the tool wear mechanism during thermally assisted machining Ti-6Al-4V. Int J Mach Tools Manuf 62, 76-87 doi:10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2012.07.001 |

| 29. | Cotterell M, Byrne G(2008) Dynamics of chip formation during orthogonal cutting of titanium alloy Ti-6Al-4V. CIRP Ann Manuf Technol 57(1), 93-96 doi:10.1016/j.cirp.2008.03.007 |

| 30. | Li H, He G, Qin X, et al(2014) Tool wear and hole quality investigation in dry helical milling of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 71(5-8), 1511-1523 doi:10.1007/s00170-013-5570-0 |

| 31. | Sutter G, List G(2013) Very high speed cutting of Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy-change in morphology and mechanism of chip formation. Int J Mach Tools Manuf 66, 37-43 doi:10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2012.11.004 |

| 32. | Gao C, Zhang L(2013) Effect of cutting conditions on the serrated chip formation in high-speed cutting. Mach Sci Technol 17(1), 26-40 doi:10.1080/10910344.2012.747887 |

| 33. | Wang Z, Nakashima S, Larson M(2014) Energy efficient machining of titanium alloys by controlling cutting temperature and vibration. Procedia CIRP 17, 523-528 doi:10.1016/j.procir.2014.01.134 |

2017, Vol. 5

2017, Vol. 5