The article information

- Fa-Da Zhang, Yi Liu, Jing-Cheng Xu, Sheng-Juan Li, Xiu-Nan Wang, Yue Sun, Xin-Luo Zhao

- Binding and conformation of dendrimer-based drug delivery systems: a molecular dynamics study

- Advances in Manufacturing, 2015, 3(3): 221-231

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40436-015-0120-7

-

Article history

- Received: 2015-05-15

- Accepted: 2015-08-16

- Published online: 2015-09-22

2 School of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai 200093, P. R. China;

3 School of Energy & Power Engineering, University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai 200093, P. R. China

Dendrimers are dendritic polymers consisting of core, branch,and terminal groups where each branch layer is called ‘‘generation (G)’’ [1, 2, 3]. The architecture of dendrimers with hollow interior spaces allows their applications as potential nanoplatforms for drug delivery [4, 5]. Dendrimers help to improve solubility and pharmaceutical kinetics. Furthermore,dendrimer nanoplatform can be decorated with targeted functional groups and/or imaging agents for targeted therapy and molecular diagnosis [6, 7, 8, 9].

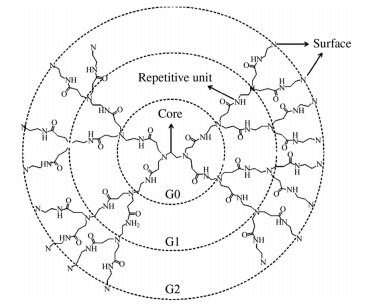

Poly (amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers are the first commercialized dendrimer family synthesized by Esfand and Tomalia [10]. PAMAM consists of a series of highly dendritic macromolecules with typical molecular weights 657-935 kg/mol (G0-G10). PAMAM consists of three basic parts with various functions. Firstly,the internal core leads to the differences in symmetry and has the electrostatic interactions with the dendritic repeated layers [11]. Secondly,the middle repetitive units can provide hollow spaces to encapsulate drug molecules. The middle parts are distinguished by the same concentric circles determined by the repetitive units as ‘‘generation’’ [12] (see Fig. 1),e.g.,G0, G1,G2,...,Gn are defined from the central core to the peripheral surface. The diameters of PAMAM dendrimers have approximately linear correlation with the generation of the dendrimers [13, 14]. Thirdly,the external surface terminated with amine groups can compound with various guest molecules,such as drugs,genetic materials,fluorescent molecules,and HBVc (FA,etc.) [15, 16, 17, 18]. The primary amino groups on the surfaces of PAMAM can be modified by different functional groups to be used as a multifunctional vector molecule in drug delivery systems [19, 20, 21, 22]. However, the charged surface groups may destroy the structures of cell membranes and induce the hemolysis of human red blood cells. Wang et al. [23] modified the surface of dendrimers with poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) to reduce the cytotoxicity of dendrimers significantly. The PEGylation of the denrimer can also improve the aqueous solubility and circulation time in blood system of human body [24, 25, 26].

|

| Fig. 1 Schematic molecular structure of PAMAM G2 dendrimer |

Many anticancer drugs (such as CE6,DOX,MTX,and SN38) are limited in clinical use due to their poor solubility and biocompatibility [27, 28]. It is shown that the dendrimer-based drug-delivery systems can improve drug’s solubility and biocompatibility,realizing the targeted delivery and the controlled release of drugs [13, 29]. The influence of pH environment of human body can release the drugs carried in dendrimers in a controlled manner [30, 31].

In dendrimer-based drug delivery systems,drug molecules can either bind covalently with dendrimers to form dendrimer-drug conjugates or incorporate non-covalently into dendrimers to form complexes [32]. In drug@dendrimer complex,drug molecules can be released more readily than conjugated system. On the other hand,it is not desirable if dendrimers release drugs too soon before reaching targeted cells [33]. Therefore,it is critical to understand the binding mechanisms of drug@dendrimer complex including binding strength and binding sites as well as the effects of surface functionalization. This work focuses on how binding strength and conformation vary with the number of loaded drug molecules.

In order to understand the mechanism of the interaction between the drug molecules and dendrimers at an atomic level,we carried out all-atom classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to study the dendrimers with and without the PEGylation. We load four types of anticancer drugs, including CE6,DOX,MTX,and SN38,respectively, gradually to saturated doses. In this work we address the issues of the binding strength and locations of the drug molecules as well as the sizes of complexes via the analyses of the binding energy (Eb) of drug molecules incorporated into dendrimers,the distribution of drug molecules, and the radius of gyration (Rg). 2 Computation methods 2.1 Computation models and simulation procedures

To study the influences of PEGylation of dendrimers as well as the types and numbers of drug molecules,we built full atomic models of non-covalently bound drug-dendrimer complexes,denoted as DN@PAMAM (or DN@GN) and DN@PAMAM-PEG (or DN@GN-PEG),respectively, for the dendrimers of generations G0-G3 with and without surface PEGylation. In the case of PEGylation,each terminal group binds covalently with a single PEG chain with atomic weight*2 000. DN represents drug molecules among one of the four types: CE6,DOX,MTX,and SN38, where N(0,1,2,4,...) is the number of drug molecules that compound with PAMAM. The drug@dendrimer complexes were first relaxed by geometry optimization (GO), followed by MD at the NVT ensemble at 298 K in vacuum. To examine the solvent effects,some systems,e.g., D36@G3G3 and D42@G3G3-PEG,were simulated in water solutions using MD at the NPT and NVT ensembles after geometry optimization.

Four types of anticancer drug molecules were studied in this work: Chlorin e6 (CE6,C34H36N4O6,M=596),Doxorubicin (DOX,C27H29NO11,M=543),Methotrexate (MTX,C20H22N8O5,M=454) and 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycampothecin (SN38,C226H20N2O5,M=392). The dendrimers G0(C22H28N10O4,M=516),G1(C62H128N26O12 , M=1 428),G2(C142H288N56O28,M=3 252) and G3(C302H608N122O60,M=6 900) were built using dendrimer module in materials studio (MS) software package. The charges of the dendrimers and drugs were assigned by Gasteiger method. And they were electrically neutral as a whole. The PEG (C90H182O45,M=1 982) chain was covalently bonded with the primary amine groups on the surface of dendrimer to build G0-PEG,G1-PEG,G2-PEG and G3-PEG. Then we added drug molecules to the hollow spaces of PAMAM to form the DN@PAMAM complex. To study the influence of solvation,we built the periodic cubic cell structure with a number of drug molecules carried in various generations of dendrimer where the distances between the adjacent complexes are 1 nm. H2O molecules were added by amorphous cell module of MS. The density of H2O was 1.0 g/cm3 . The CE616@G2-PEG,DOX16@G2-PEG,CE642@G3-PEG and DOX42@G2-PEG complex systems have 7 870,8 704,15 097 and 14 385 H2O molecules,respectively.

In this work we used the classical MD simulation software (forcite module implemented in MS [34]) to execute the GO and MD calculations. We used the Dreiding force field in both GO and MD computations [35]. The convergence tolerance of the energy and force in GO is 0.836 J/mol and 41.8 J/(mol·nm),respectively. The NPT MD was executed at 298 K and 1.013×105 Pa,followed by NVT MD runs at 298 K for 1 ns. The other details of the MD simulation conditions are set as follows. (1) Dynamics parameters: in the NPT and NVT ensemble we use the thermostat (nose) to keep the target temperature equal to 298 K. The time step is 1.0 fs and the total simulation time is 1 ns. (2) Energy parameters: we use Dreiding force field to calculate the electrostatic,van der Waals and Hydrogen bond force. For these three long-range force terms,the cut-off of the distances are 1.55 nm,1.55 nm and 0.45 nm,spline widths are 0.1 nm,0.1 nm and 0.05 nm,respectively. The buffer widths are 0.05 nm and truncation methods are cubic spline. After equilibrium is reached,the last 0.5 ns in the MD trajectories was used for statistical analyses. 2.2 Definitions of binding energy and its associated components

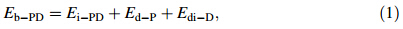

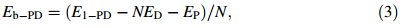

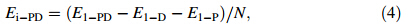

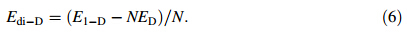

To evaluate binding strength quantitatively,we calculated binding energy and its associated components including interaction energy and deformation energy. The relationships among these energies can be written

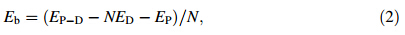

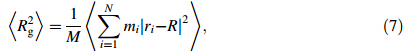

Rg represents the size of DN@PAMAM complex,defined as follows

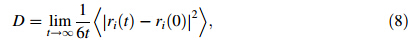

Binding energy (Eb),defined in Eq. (2),measures the binding strength of dendrimer-drug complex including the interaction energies of drug-dendrimer and drug-drug (if any) as well as the deformation energies of drug and dendrimers. SmallerEbwith larger absolute value means stronger binding. When a single drug molecule is loaded into PAMAM or PAMAM-PEG,theEbscatters at various binding positions (see Figs. 2 and 3). The average Eb of the studied drug molecules decreases as DOX ((-16.23±3.09)×104 J/mol)≈CE6 ((-15.94±3.17)×104 J/mol)[MTX ((-13.49±2.16)×104 J/mol)≈SN38 ((-13.44±3.16) ×104 J/mol) in the D1@G3 complexes. The negativeEb indicates that it is energetically favorable to incorporate these drug molecules into PAMAM. The standard deviations ofEbare*20% around their averaged value indicating the large site dependence of binding energy. Considering both interaction energy and deformation energy (confirmed later in Fig. 5 when N is small),we find that the interaction energy between PAMAM and drug is larger than the deformation energy of PAMAM leading to overall attractive PAMAMdrug interactions. This indicates that PAMAM-drug interactions are stronger than the intramolecular interactions among PAMAM branches.

|

| Fig. 2 Binding energy Eb of a single drug molecule loaded into G3 at 36 different binding sites in a CE61 @G3,bDOX1 @G3,cMTX1 @G3, and d SN381@G |

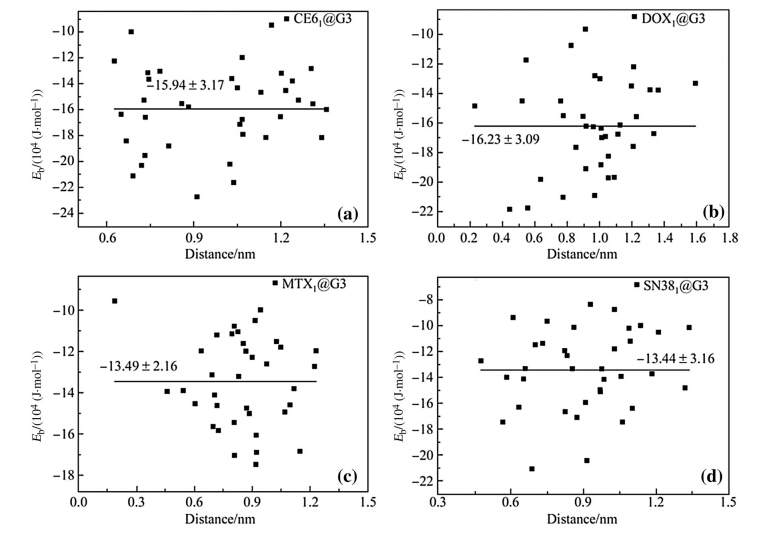

|

| Fig. 3 Binding energy Eb of a single drug molecule loaded into G3-PEG at 42 different binding sites in a CE61 @G3-PEG,bDOX1 @G3-PEG, cMTX1@G3-PEG,and d SN381@G3-PEG |

In the case of D1@G3-PEG (see Fig. 3),the averageEbof the studied drug molecules decreases as CE6 ((6.28±23.91) ×104 J/mol) >DOX ((8.60±21.30)×104 J/mol)> (MTX (11.06±17.76)×104 J/mol)[SN38 ((11.83±23.30) ×104 J/mol). The positive average Eb indicates that it is energetically unfavorable to incorporate drug molecules into PAMAM-PEG. Further analyses on deformation energies show thatEbbecomes positive mainly due to large deformation energy of PAMAM-PEG upon drug insertion. The drug molecules can bind with either PAMAM or PEG in D1@G3-PEG. The earlier results show thatEbof drug-PAMAM is negative. Therefore,we conclude that positiveEbof drugPEG dominates and drug-PEG interactions are weaker than the intramolecular interactions among PEG chains.

When multiple drug molecules are encapsulated into PAMAM,we calculatedEbas functions of the number of drug molecules (N) shown in Fig. 4.The Eb fluctuates whenNis small as they scatter depending on various possible binding sites. However,Eb tends to approach towards constant values between (10.87-15.05)×104 J/mol asNincreases beyond certain values,e.g.,~20 in DN@G3 or~30 in DN@G3-PEG. Both systems have similar trendsEb (CE6)≈Eb (DOX)>Eb(MTX)>Eb(SN38) when N is large.

|

| Fig. 4 Binding energy Eb as functions of the number of drug molecules in a D@G3 and b D@G3-PEG where D is CE6,DOX,MTX,and SN38 |

On the basis of analyses above,the drug-PAMAM binding is stronger than the intramolecular interactions of PAMAM,but the drug-PEG binding is weaker than the intramolecular interactions among PEG chains. Although drugs bind with PAMAM energetically more favorable, when the number of drug molecules increase,drug should bind with PEG chains that provide more hollow spaces. Even though the drug-PEG binding energy is thermodynamically unfavorable,the complexes remain stable in the MD simulations,suggesting that the complexes are kinetically metastable once they form. 3.2 Instantaneous binding energy,interaction energy,and deformation energy of DN@PAMAM complex

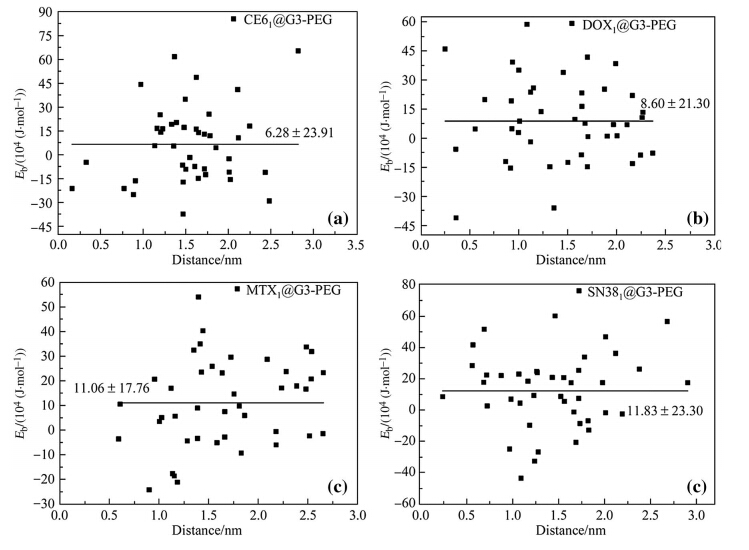

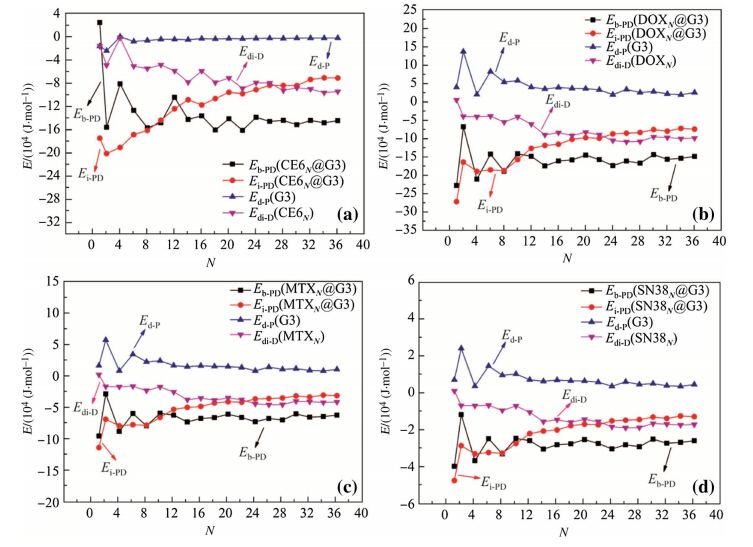

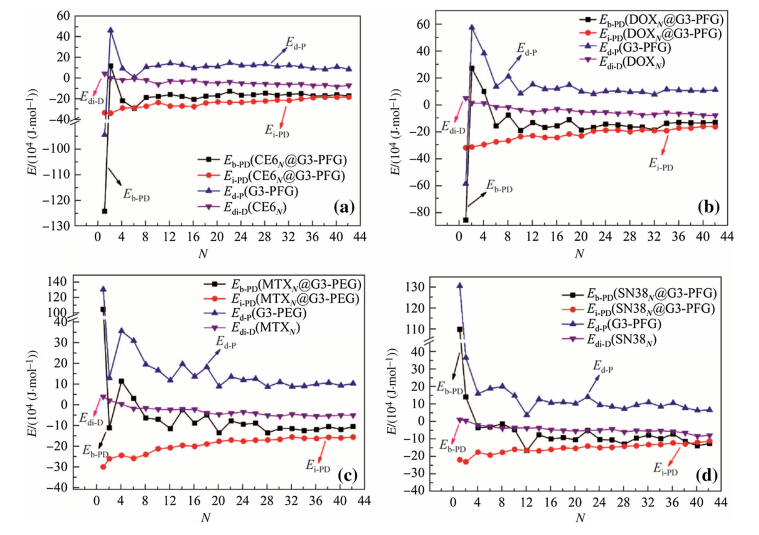

In order to better understand the relationship among the four types of energies (see Eq. (1)),Eb-PD,Ei-PD,Ed-P,and Edi-D,we calculated and plotted theses energies for the DN@PAMAM in Fig. 5 and DN@PAMAM-PEG complexes in Fig. 6. The studied systems correspond independently to different numbers and types of drug molecules,so the trends obtained from these results are statistically meaningful.

|

| Fig. 5 Instantaneous Eb-PD,Ei-PD,Ed-P,and Edi-Dvs.Nof the DN@G3 complexes where D is a CE6,b DOX,c MTX,and d SN38 |

|

| Fig. 6 Instantaneous Eb-PD,Ei-PD,Ed-P,and Edi-Dvs.Nof the DN@G3 complexes where D is a CE6,b DOX,c MTX,and d SN38 |

As the number of drug moleculesNincreases,the instantaneous binding energies approach to constant values quickly after initial fluctuations at smallN(\12). We find that the trends of deformation energies of dendrimers coincide well with those of instantaneous binding energies,indicating that the conformations of dendrimers within the complexes are critical to determine the binding strength of drug-dendrimer. As the number of loaded drug moleculesNincreases,the deformation energies of drug molecules decrease and the interaction energies become weaker until both level off. The trends discussed above are qualitatively similar in both DN@G3 and DN@G3-PEG complexes. Quantitatively,the interaction energies of drug-(G3-PEG) are stronger than those of drug-G3,but the deformation energies of G3-PEG are larger than those of G3. 3.3 Rg

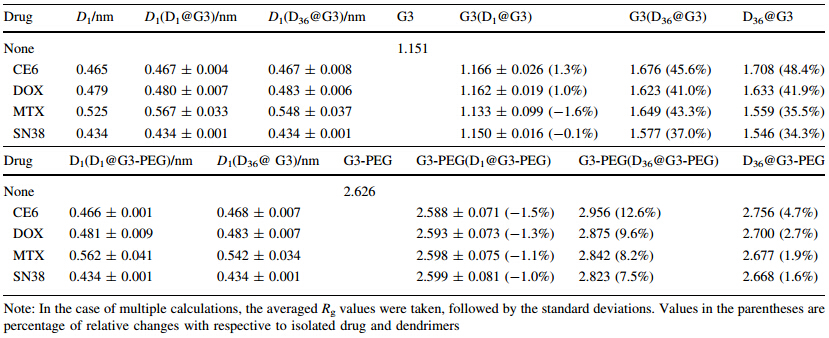

To examine the size changes,the radii of gyration of the drug molecules,dendrimers,and DN@G3 complexes are calculated and averaged over the equilibrium MD trajectories at 298 K (see Table 1). The Rg of isolated drug molecules (D) studied in this work is Rg (CE6)= 0.465 nm,Rg (DOX)=0.479 nm,Rg (MTX)=0.525 nm, and Rg (SN38)=0.434 nm,respectively. The Rg values of these drug molecules change littlewhen they are incorporated into PAMAM regardless of the number of molecules and PEGylation except that the largest floppy MTX molecules expand slightly 3%-8%. The whole D36@G3G3 complexes expand 34%-48% relative to the pristine G3. The Rg of D36@G3G3 is slightly larger or smaller than that of G3 embedded within the complex [G3(D36@G3G3)] indicating that some drug molecules reside on the periphery of PAMAM. These results show that pristine PAMAM expands significantly when drug molecules are inserted while the drug molecules themselves are relatively rigid withoutlarge deformation.

|

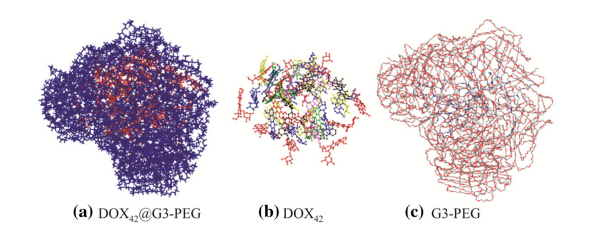

When PAMAM is PEGylated,the Rg of D36@G3G3-PEG increases only 2%-5% after 36 drug molecules are inserted. These results imply that PEG chains have more empty interior spaces to accommodate drugs than pristine PAMAM. The Rg values of D36@G3G3-PEG are always smaller than those of G3-PEG within D36@G3G3-PEG complexes,indicating that the drug molecules are encapsulated deeply inside G3-PEG.

When a single molecule is inserted,most G3 and G3-PEG shrink slightly (<2%). When many molecules are inserted (e.g.,N=36),the Rg of G3 increases 37%-46%, while that of G3-PEG increases only 8%-13%. These results indicate that small number of drug molecules shrink PAMAM as glue while many drug molecules expand PAMAM.

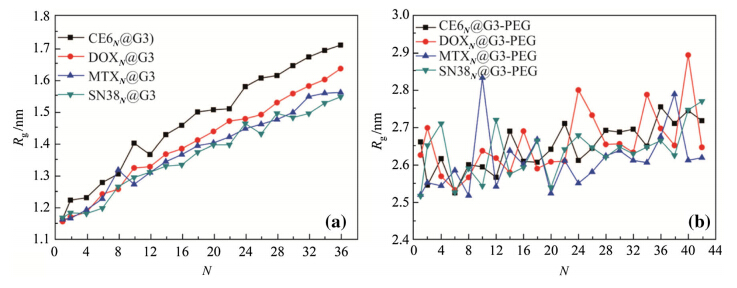

Rg values as functions of the number of drug molecules are plotted in Fig. 7 for DN@G3 and DN@G3-PEG. The Rg of DN@G3 is linearly proportional to the number of the drug molecules. The Rg of DN@G3-PEG fluctuates and has weaker dependence on the number of drugs. When the drugs are encapsulated into the G3,the Rg increases 34.3%-48.4% specifically from 1.151 nm (N=0) to 1.546-1.708 nm (N=36). The Rg of G3-PEG complexes increase 1.6%-5.0% specifically from 2.626 nm (N=0) to 2.668-2.756 nm (N=36). The Rg of G2(G2-PEG) is 0.896 nm (1.996 nm). The other results of G2(G2-PEG) system are similar to G3(G3-PEG) system.

|

| Fig. 7 Rg vs.N of the a DN@G3 and b DN@G3-PEG complexes where D is CE6,DOX,MTX,and SN38 |

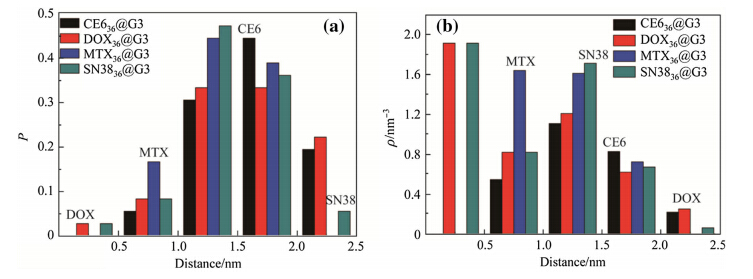

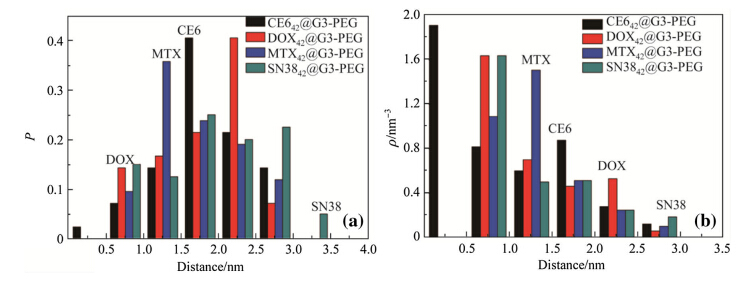

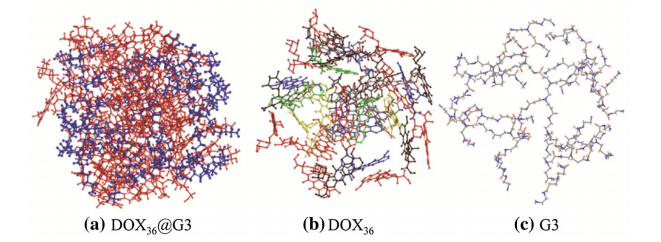

It is crucial to understand the binding sites of drug molecules embedded in dendrimers. The probability and density distributions of the distances between the centers of masses (COM) of the dendrimers and drug molecules are calculated based on the averaged equilibrium MD trajectories of D36@G3G3 and D42@G3G3-PEG complexes (see Figs.8 and 9). The results show that most drug molecules stay 1.5 nm away from the COM of G3. These distances are close to the Rg of complex 1.6 nm,indicating that the positions of drug molecules determine the Rg of the complexes and many of drug molecules expose on the surface of D36@G3G3. On the other hand,most drug molecules are located 2.0 nm away from the COM of G3-PEG. These distances are smaller than theRg of complexes 2.7 nm, implying that drug molecules are encompassed by the PEG chains and deeply embedded. Indeed,visual inspection of MD snapshots shown in Figs.10 and 11 supports the results of Rg. The information about the binding sites suggests that PEGlyation not only can reduce the cytotoxicity and improve the aqueous solubility of the dendrimers but also can directly interact with drug molecules. Therefore,designing functional groups of PEG chains is critical to develop efficient drug-delivery system.

|

| Fig. 8 a Probability and b density distributions of the distances between the COM of the dendrimers and drug molecules in the D36@G3 complexes |

|

| Fig. 9 a Probability and b density distributions of the distances between the COM of the dendrimers and drug molecules in the D43@G3-PEG complexes |

|

| Fig. 10 Atomic structures ofaDOX36@G3 snapshot where G3 is in blue and DOX36 is in red.b and care the structures of the DOX36 and G3 separated from the DOX36@G3,respectively. For sake of clarity H atoms are not shown |

|

| Fig. 11 Atomic structures of a DOX42@G3-PEG snapshot where G3-PEG is in blue and DOX42 is in red. b and c are the structures of the DOX42and G3-PEG separated from the DOX42@G3-PEG,respectively. For sake of clarity H atoms are not shown |

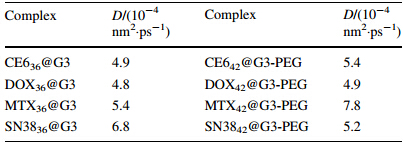

To examine the diffusion behaviors of dendrimer-based drug-delivery system (DDS),we calculated the diffusion coefficients Dof DN@G3 in water (see Table 2). The calculations are converged as shown in Figs. S1 and S2 in Supporting Information. The diffusion coefficients of DN@G3 and DN@G3-PEG complexes are 5.0×10-4 -8.0×10-4 ,which are smaller than the diffusion coefficient of water 2.0×10-2 . Therefore,the dendrimer-based DDS diffuse slowly in solvents,which elongates the retention time of DDS in human body.

This work carried out molecular dynamics study on the dendrimer-based drug delivery systems focusing on the binding strength and conformation of DDS as functions of the numbers and types of drug molecules. The studied DDSs are PAMAM dendrimers loaded with the anticancer drug molecules DOX,MTX,SN38,and CE6,respectively. The PEGylated PAMAM was also studied to examine the effects of functionalization. On the basis of analyses of binding energies and their associated components including interaction energies and deformation energies,we find that the drugs bind with PAMAM more strongly than the intramolecular bindings of PAMAM,while the drugs bind with PEG chains more weakly than the intramolecular bindings among PEG chains. The deformed conformations of dendrimers embedded in the complexes are crucial to determine the binding strength of the drug-dendrimer complex. These results indicate that weakening the intramolecular interactions among functionalization groups of PAMAM can facilitate the incorporation of drug molecules.

Loading multiple drug molecules enlarges PAMAM dendrimers significantly but has much weaker effects on the PEGylated PAMAM. The drug molecules themselves remain similar sizes even after loaded into dendrimers. The PAMAM-PEG can accommodate more drug molecules and encompass drugs more deeply and strongly than pristine PAMAM. Our studies show that the drug molecules directly bind with PEG chains suggesting that designing the functionalization groups of PAMAM is critical to improve its drug bindings. The information extracted from this work provides helpful theoretical evidence to develop more effective dendrimer-based drug delivery systems.

Acknowledgments The authors are grateful for financial supports from ‘‘Shanghai Pujiang Talent’’ program (Grant No. 12PJ1406500), ‘‘Shanghai High-tech Area of Innovative Science and Technology (Grant No. 14521100602)’’,STCSM; ‘‘Key Program of Innovative Scientific Research’’ (Grant No. 14ZZ130) and ‘‘Key Laboratory of Advanced Metal-based Electrical Power Materials’’,the Education Commission of Shanghai Municipality; State Key Laboratory of Heavy Oil Processing,China University of Petroleum (Grant No. SKLOP201402001); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51202137,61240054,and 11274222). Computations were carried out at Hujiang HPC facilities at USST,Shanghai Supercomputer Center,and National Supercomputing Center in Shenzhen,P.R. China.| 1. | Menjoge AR, Kannan RM, Tomalia DA (2010) Dendrimer-based drug and imaging conjugates: design considerations for nanomedical applications. Drug Discov Today 15(5):171-185 |

| 2. | Tomalia DA, Baker H, Dewald J et al (1985) A new class of polymers: starburst-dendritic macromolecules. Polym J 17(1):117-132 |

| 3. | Kolhe P, Misra E, Kannan RM et al (2003) Drug complexation, in vitro release and cellular entry of dendrimers and hyperbranched polymers. Int J Pharm 259(1):143-160 |

| 4. | Zhang YH, Thomas TP, Lee KH et al (2011) Polyvalent saccharide- functionalized generation 3 poly(amidoamine) dendrimer- methotrexate conjugate as a potential anticancer agent. Bioorgan Med Chem 19(8):2557-2564 |

| 5. | Kurtoglu YE, Mishra MK, Kannan S et al (2010) Drug release characteristics of PAMAM dendrimer-drug conjugates with different linkers. Int J Pharm 384(1):189-194 |

| 6. | Wiener EC, Brechbiel MW, Brothers H et al (1994) Dendrimerbased metal-chelates: a new class of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Magn Reson Med 31(1):1-8 |

| 7. | Kobayashi H, Saga T, Kawamoto S et al (2001) Dynamic micromagnetic resonance imaging of liver micrometastasis in mice with a novel liver macromolecular magnetic resonance contrast agent DAB-Am64-(1B4M-Gd) 64. Cancer Res 61(13):4966-4970 |

| 8. | Majoros IJ, Williams CR, Baker JR (2008) Current dendrimer applications in cancer diagnosis and therapy. Curr Top Med Chem 8(14):1165-1179 |

| 9. | Lee CC, MacKay JA, Frechet JMJ et al (2005) Designing dendrimers for biological applications. Nat Biotechnol 23(12): 1517-1526 |

| 10. | Esfand R, Tomalia DA (2001) Poly (amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers: from biomimicry to drug delivery and biomedical applications. Drug Discov Today 6(8):427-436 |

| 11. | Kavyani S, Amjad-Iranagh S, Modarress H (2014) Aqueous poly(amidoamine) dendrimer G3 and G4 generations with several interior cores at pHs 5 and 7: a molecular dynamics simulation study. J Phys Chem B 118(12):3257-3266 |

| 12. | Mignani S, El Kazzouli S, Bousmina M et al (2013) Expand classical drug administration ways by emerging routes using dendrimer drug delivery systems: a concise overview. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 65(10):1316-1330 |

| 13. | Svenson S, Tomalia DA (2012) Dendrimers in biomedical applications—reflections on the field. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 64(1):102-105 |

| 14. | Tomalia DA, Naylor AM, Goddard WA (1990) Starburst dendrimers: molecular-level control of size, shape, surface chemistry, topology and flexibility from atoms to macroscopic matter. Angew Chem Int Edit 29(2):138-175 |

| 15. | Yabbarov NG, Posypanova GA, Vorontsov EA et al (2013) Targeted delivery of doxorubicin: drug delivery system based on PAMAM dendrimers. Biochemistry (Moscow) 78(8):884-894 |

| 16. | Chang YL, Liu N, Chen L et al (2012) Synthesis and characterization of DOX-conjugated dendrimer-modified magnetic iron oxide conjugates for magnetic resonance imaging, targeting, and drug delivery. J Mater Chem 22(19):9594-9601 |

| 17. | Wang Y, Cao XY, Guo R et al (2011) Targeted delivery of doxorubicin into cancer cells using a folic acid-dendrimer conjugate. Polym Chem 2(8):1754-1760 |

| 18. | Chang YL, Li YP, Meng XL et al (2013) Dendrimer functionalized water soluble magnetic iron oxide conjugates as dual imaging probe for tumor targeting and drug delivery. Polym Chem 4(3):789-794 |

| 19. | Majoros IJ, Myc A, Thomas T et al (2006) PAMAM dendrimerbased multifunctional conjugate for cancer therapy: synthesis, characterization, and functionality. Biomacromolecules 7(2):572-579 |

| 20. | Rekas A, Lo V, Gadd GE et al (2009) PAMAM dendrimers as potential agents against fibrillation of alpha-synuclein, a Parkinson's disease-related protein. Macromol Biosci 9(3):230-238 |

| 21. | Kang H, DeLong R, Fisher MH et al (2005) Tat-conjugated PAMAM dendrimers as delivery agents for antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides. Pharm Res 22(12):2099-2106 |

| 22. | Majoros IJ, Thomas TP, Mehta CB et al (2005) Poly(amidoamine) dendrimer-based multifunctional engineered nanodevice for cancer therapy. J Med Chem 48(19):5892-5899 |

| 23. | Wang W, Xiong W, Zhu YH et al (2010) Protective effect of PEGylation against poly(amidoamine) dendrimer-induced hemolysis of human red blood cells. J Biomed Mater Res B 93B(1):59-64 |

| 24. | He H, Li Y, Jia XR et al (2011) PEGylated poly(amidoamine) dendrimer-based dual-targeting carrier for treating brain tumors. Biomaterials 32(2):478-487 |

| 25. | Sideratou Z, Kontoyianni C, Drossopoulou GI et al (2010) Synthesis of a folate functionalized PEGylated poly(propylene imine) dendrimer as prospective targeted drug delivery system. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 20(22):6513-6517 |

| 26. | Singh P, Gupta U, Asthana A et al (2008) Folate and folate-PEGPAMAM dendrimers: synthesis, characterization, and targeted anticancer drug delivery potential in tumor bearing mice. Bioconjug Chem 19(11):2239-2252 |

| 27. | Isakau HA, Parkhats MV, Knyukshto VN et al (2008) Toward understanding the high PDT efficacy of chlorine6- polyvinylpyrrolidone formulations: photophysical and molecular aspects of photosensitizer-polymer interaction in vitro. J Photochem Photobiol B 92(3):165-174 |

| 28. | Goldberg DS, Vijayalakshmi N, Swaan PW et al (2011) G3.5 PAMAM dendrimers enhance transepithelial transport of SN38 while minimizing gastrointestinal toxicity. J Control Release 150(3):318-325 |

| 29. | Allen TM, Cullis PR (2004) Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science 303(5665):1818-1822 |

| 30. | Tian WD, Ma YQ (2012) pH-responsive dendrimers interacting with lipid membranes. Soft Matter 8(9):2627-2632 |

| 31. | Maingi V, Kumar MVS, Maiti PK (2012) PAMAM dendrimer- drug interactions: effect of pH on the binding and release pattern. J Phys Chem B 116(14):4370-4376 |

| 32. | Crampton HL, Simanek EE (2007) Dendrmers as drug delivery vehicles: non-covalent interactions of bioactive compounds with dendrimers. Polym Int 56(4):489-496 |

| 33. | Kwon IK, Lee SC, Han B et al (2012) Analysis on the current status of targeted drug delivery to tumors. J Control Release 164(2):108-114 |

| 34. | Karatasos K, Krystallis M (2009) Dynamics of counterions in dendrimer polyelectrolyte solutions. J Chem Phys 130(11):1-11 |

| 35. | Zhong TP, Ai PF, Zhou J (2011) Structures and properties of PAMAM dendrimer: a multi-scale simulation study. Fluid Phase Equilib 302(1):43-47 |

| 36. | Liu Y, Bryantsev VS, Diallo MS et al (2009) PAMAM dendrimers undergo pH responsive conformational changes without swelling. J Am Chem Soc 131(8):2798-2799" |

2015, Vol. 3

2015, Vol. 3