文章信息

- 张依航, 蔡珊, 陈子玥, 张奕, 蒋家诺, 刘云飞, 党佳佳, 钟盼亮, 师嫡, 董彦会, 胡佩瑾, 朱广荣, 马军, 宋逸.

- Zhang Yihang, Cai Shan, Chen Ziyue, Zhang Yi, Jiang Jianuo, Liu Yunfei, Dang Jiajia, Zhong Panliang, Shi Di, Dong Yanhui, Hu Peijin, Zhu Guangrong, Ma Jun, Song Yi

- 中国9~18岁儿童青少年首次遗精/月经初潮与心理困扰的关联研究

- Research on the association between the occurrence of spermarche and menarche and psychological distress among Chinese children and adolescents aged 9-18 years

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(10): 1545-1551

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(10): 1545-1551

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20230514-00298

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2023-05-14

青春期是童年期至成年期的过渡阶段,面临着荷尔蒙和身体、社会环境、脑和精神的多重变化[1]。这一时期容易出现心理健康问题,其中一些会持续至成年[2-4],导致长期的发病率和巨大的社会负担。WHO数据显示,全球10~19岁人群中有1/7患有精神障碍[5],中国《2022年青少年心理健康状况调查报告》表明,约14.8%的青少年存在不同程度的抑郁风险[6]。首次遗精/月经初潮是男性与女性青春期发育的关键指标[7],标志着个体的生殖等各项功能走向成熟。尤其是月经初潮,作为女性性成熟的里程碑事件,其发生年龄常被认为是成年期生活健康状况的关键[8]。19世纪中叶以来,在世界范围内观察到月经初潮和乳房发育年龄提前的长期趋势,中国研究数据亦显示,男性首次遗精与女性月经初潮年龄均呈提前趋势[9-12]。首次遗精/月经初潮的提前与多种不良健康结局有关,如男性成年期身高不足[13]、女性卵巢癌[14]、代谢性疾病[15]、心血管疾病[16]、性行为提前[17]等。既往研究表明,遗传、营养、环境内分泌干扰物[18]以及睡眠模式[19]等与青春期发育提前有关,但在青少年心理健康问题高患病率的背景下,对心理健康与青春期发育提前的关联研究还较少。因此,本研究拟使用2019年全国学生体质与健康调研数据分析心理困扰对发生首次遗精/月经初潮的影响,为青少年青春期发育与心理健康促进提供科学依据。

对象与方法1. 研究对象:来自2019年全国学生体质与健康调研数据,该调研采用多阶段分层整群抽样的方法,具体方法参见文献[20]。本研究对全国30个省(自治区、直辖市)(未包括西藏自治区)9~18岁儿童青少年进行分析,在剔除首次遗精/月经初潮数据不全以及心理困扰等信息不完整个体后,共纳入54 438名11~18岁男生和76 376名9~18岁女生。

2. 分析指标:首次遗精/月经初潮状况分别由内科男、女医生询问,只询问“已或未”出现遗精或月经现象,不询问具体日期。调查前对医生进行培训,帮助女生区分月经来潮和其他出血(如会阴部损伤出血),帮助男生识别首次遗精的出现。

采用凯斯勒心理困扰量表(K10)对心理困扰程度进行判定,要求受试者填写与正常情绪波动相关的精神和身体症状方面的10个条目,各条目的回答结果采用Likert 5点计分,对10个条目的得分进行求和,K10总分≤19、20~、25~、≥30分别表示无、轻度、中度、重度心理困扰,中度和重度心理困扰合称高心理困扰[21]。

使用问卷收集年龄、性别、城乡、省份等指标[22],其中省份按照国家统计局划分标准划分为东部、中部、西部和东北部地区[23]。经济发展水平综合考虑地级市的区域生产总值、人均年总收入、人均食物消费量、人口自然增长率和区域社会福利指数共5项指标,在每个省内将各地级市的社会经济水平按照从高到低的顺序分为3段,每段内随机抽取1个地级市,分别定义为选择高、中、低片区。

3. 统计学分析:采用概率单位回归法计算男女生出现首次遗精/月经初潮的中位数年龄,以1岁为间隔,男生11~18岁共8个年龄组,女生9~18岁共10个年龄组,将年龄组组中值换算为对数值,各年龄组月经初潮发生率换算成概率单位,拟合曲线后50%出现首次遗精/月经初潮的年龄即为中位数年龄。使用χ2检验比较各年龄组心理困扰情况及首次遗精/月经初潮发生率的差异,采用多因素logistic回归模型分层分析城乡、东部、中部、西部及东北部地区、经济发展水平高、中、低片区11~、13~、16~18岁年龄组男生和9~、13~、16~18岁年龄组女生高心理困扰与发生首次遗精/月经初潮的关联。使用SPSS 26.0以及R 4.0.5软件进行分析,双侧检验,检验水准α=0.05。

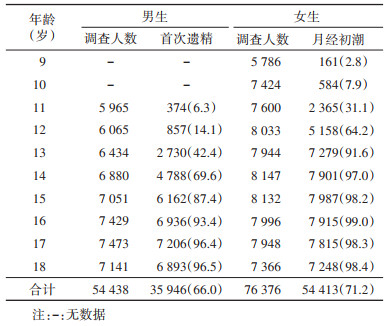

结果1. 基本情况:2019年中国男生8个年龄组首次遗精发生率为6.3%~96.5%,女生10个年龄组月经初潮发生率为2.8%~99.0%。见表 1。男女生发生首次遗精/月经初潮的年龄M(Q1,Q3)分别为13.8(13.0,14.6)和12.0(11.4,12.7)岁。男生高心理困扰率为32.5%,女生高心理困扰率为32.7%。

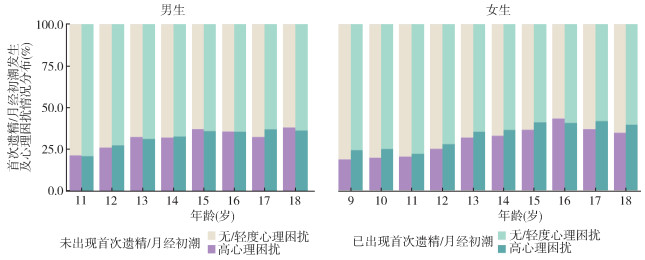

2. 各年龄组心理困扰及发生首次遗精/月经初潮的情况:11~18岁男生中,高心理困扰率随年龄增加而升高(趋势检验χ2=520.06,P < 0.001),各年龄段已出现与未出现首次遗精者高心理困扰率差异无统计学意义。9~18岁女生中,高心理困扰率随年龄增加而升高(趋势检验χ2=2 299.20,P < 0.001),10岁及12岁女生已出现月经初潮组高心理困扰率高于未出现月经初潮组,差异有统计学意义(χ2=9.81、8.19,均P < 0.05)。见图 1。

|

| 图 1 2019年中国9~18岁汉族儿童青少年首次遗精/月经初潮发生及心理困扰情况分布 |

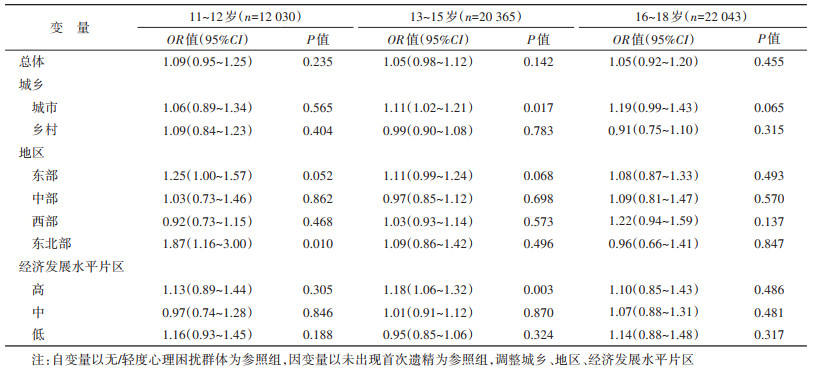

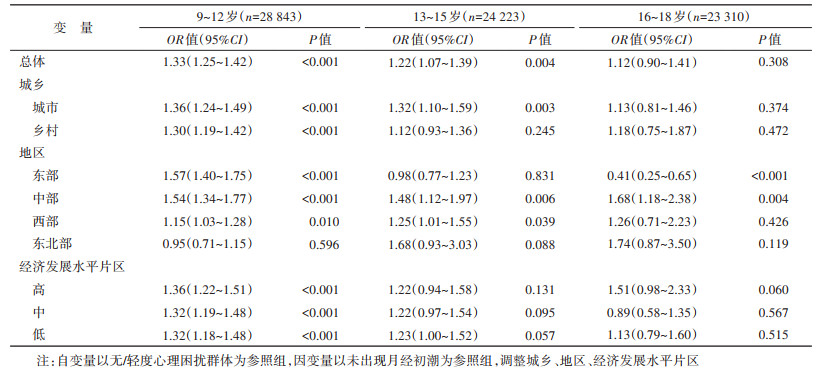

3. 高心理困扰与首次遗精/月经初潮发生的关联:以是否发生首次遗精/月经初潮为因变量,是否存在高心理困扰为自变量,分层分析结果显示,高心理困扰与居住在东北部地区11~12岁男生首次遗精发生呈正相关(OR=1.87,95%CI:1.16~3.00);高心理困扰与居住在城市及经济发展水平高片区的13~15岁男生首次遗精发生呈正相关(OR=1.11,95%CI:1.02~1.21;OR=1.18,95%CI:1.06~1.32)。见表 2。总体上,9~12岁、13~15岁女生高心理困扰与月经初潮发生呈正相关(OR=1.33,95%CI:1.25~1.42;OR=1.22,95%CI:1.07~1.39)。居住在除东北部地区外不同地区、经济发展水平片区及城乡的9~12岁女生,居住在城市、中部地区、西部地区的13~15岁女生以及居住在中部地区的16~18岁女生高心理困扰与月经初潮的发生呈正相关,而居住在东部地区的16~18岁女生高心理困扰与月经初潮的发生则呈负相关。见表 3。

心理健康是青少年当前及未来健康的一个重要指标[24]。在全球范围内,心理健康问题是导致10~19岁青少年残疾和死亡的主要原因之一[25]。中国青少年心理健康现状也不容乐观[6]。本研究结果显示超过半数的中国9~18岁汉族儿童青少年存在心理困扰,高心理困扰率超过30%,提示亟需重视青少年心理健康状况,在学校开展有效的心理健康教育。

在男女生中均有随年龄增加而高心理困扰率升高的趋势,这与既往研究结果相似[26],青春期认知控制和奖赏敏感性这两个系统的不同成熟曲线[27]以及随年龄升高面临学业、社会适应等方面压力增加[28]是可能的原因。此外,本研究结果显示,低年龄段女生中已出现月经初潮组高心理困扰率更高,尤其是10岁已出现月经初潮的女生高心理困扰率显著高于同年龄段未出现组,且同时高于11岁已出现月经初潮组。由于月经初潮已经是青春期发育晚期事件,提示10岁出现月经初潮的女生在更早期已经有乳房、阴毛发育等青春期发育事件,心理困扰的产生也更早,显示提前的青春期发育给低年龄段女生带来的不良应激。Sontag等[29]的研究显示,发育提前女童和发育延迟男童同伴应激更为显著,容易产生更多的适应不良并导致情绪症状的发生,Joinson等[30]的研究也显示,月经初潮提前的女童在13岁和14岁时抑郁症状的水平高于月经初潮适时和推迟的女童。而男生中未出现相似结果,原因可能在于女生更多的反刍思维加剧了情绪症状的出现[31],且女生进入青春期的时间更早,在青春期早中期的研究中易被观测到,此外,由于研究方法、测量指标和样本特征的差异,关于男生青春期的研究相对女生较少且结果并不一致[32],因而后续对于男生心理健康与青春期发育的关联需要更进一步的研究。

本研究中显示的男女生首次遗精/月经初潮中位年龄的提前与发展中国家青春期发育持续提前的趋势一致[33]。既往研究表明,经济增长带来的营养条件提升、生活方式改变、环境内分泌干扰物增多等均会对首次遗精/月经初潮年龄产生影响[34]。多因素logistic回归结果显示,在控制潜在影响因素后,9~12岁和13~15岁年龄组女生中高心理困扰与月经初潮的发生呈正相关。说明在关注青春期发育提前对青少年心理健康的影响之外,同样需要注意心理健康对青春期发育的作用,尤其在女生群体中。有证据表明,早期成长逆境与青春期发育提前有关,这种应激诱导的发育提前可能会导致日后的不良健康结局,对个体、家庭和社会造成沉重的精神压力和经济负担[35-36];“社会心理应激加速假说”也认为,社会心理应激会导致女性青春期发育、性行为和生育等整个生殖策略的提前[37],而心理困扰是心理应激水平升高的一种外在表现。下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺(HPA)轴和下丘脑-垂体-性腺(HPG)轴耦联是可能的潜在机制之一,研究表明HPA轴被抑制,导致皮质醇分泌减少,从而使女童青春期发育提前[38]。此外,分层分析结果显示,居住在城市和经济发展水平高片区的13~15岁男生中心理困扰与首次遗精的发生呈正相关,说明心理健康对于男生青春期发育的作用较先出现在社会经济水平较高的地区,原因可能在于这些地区由营养和卫生条件改善导致的年龄提前已逐渐得到控制,而精神压力的影响正在凸显。而在9~12岁年龄组女生中,与居住地区无关,均受到心理困扰对月经初潮的影响,提示这一青春期发育开始出现的年龄组女性的敏感性,既往也有研究表明,家庭关系[39-40]、虐待[37]、学习适应和同伴关系[41]等导致的心理应激是女生月经初潮提前的危险因素,且由于女性青春期发育提前引起的不安全性行为和少女妊娠等生殖健康问题的严重性[42],需要更早、更全面地开展青春期性教育,教授必要的知识和技能,以及加强心理健康教育以减少心理健康问题对月经初潮提前的影响。此外,居住在东部地区的16~18岁年龄组女生高心理困扰对月经初潮的发生的抑制作用,可用“儿童发展理论”做部分解释,即个体根据家庭环境的组成和质量有条件地改变童年期的长度,在高质量的社会环境中延长童年期(推迟青春期)以充分利用高质量的父母投资[43],但由于此现象在同年龄组城市、经济发展水平高片区女生的分层分析中并未观测到,且16~18岁年龄组还未出现月经初潮人数较少,统计结果存在一定偶然性,因此对于高年龄组未出现月经初潮群体还需要进一步的研究。

总之,本研究发现2019年中国9~18岁汉族儿童青少年首次遗精/月经初潮的发生与心理困扰情况存在关联,在9~12岁女生和生活在社会经济发展水平较高地区的13~15岁男生中尤为显著。本研究为进一步探究青少年心理健康对青春期发育的影响提供支持,也为心理健康干预及青春期性教育的开展时间和重点关注人群提供了依据。本研究的局限性在于横断面研究无法验证因果关系,自填式K10存在回忆偏倚,用首次遗精作为男生青春期发育的观察指标不够客观准确,此外,受问卷内容限制,本研究的回归模型未能对生活方式、家庭关系、环境因素等其他混杂因素做出调整,需要在今后的研究中进一步探索。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 张依航:分析/解释数据、论文撰写、统计分析;蔡珊、陈子玥、张奕、蒋家诺、刘云飞、党佳佳、钟盼亮、师嫡、董彦会:文章审阅;胡佩瑾、朱广荣:采集数据、文章审阅;马军:文章审阅、行政/技术或材料支持;宋逸:文章审阅、获取研究经费

| [1] |

Blakemore SJ. Adolescence and mental health[J]. Lancet, 2019, 393(10185): 2030-2031. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31013-X |

| [2] |

Belfer ML. Child and adolescent mental disorders: the magnitude of the problem across the globe[J]. J Child Psychol Psychiat, 2008, 49(3): 226-236. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01855.x |

| [3] |

Call KT, Riedel AA, Hein K, et al. Adolescent health and well-being in the twenty-first century: a global perspective[J]. J Res Adolesc, 2002, 12(1): 69-98. DOI:10.1111/1532-7795.00025 |

| [4] |

Roza SJ, Hofstra MB, van der Ende J, et al. Stable prediction of mood and anxiety disorders based on behavioral and emotional problems in childhood: a 14-year follow-up during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood[J]. Am J Psychiat, 2003, 160(12): 2116-2121. DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2116 |

| [5] |

世界卫生组织. 青少年精神卫生[EB/OL]. (2021-11-17)[2023-06-08]. https://www.who.int/zh/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health.

|

| [6] |

中国科学院心理研究所. 心理健康蓝皮书(2022版)发布: 青少年群体抑郁风险高于成年群体[EB/OL]. (2023-02-23)[2023-07-06]. https://www.psych.cas.cn/news/cmsm/202303/t20230301_6687013.html.

|

| [7] |

陶芳标. 青春发动时相提前与青少年卫生系列述评(1): 早期生长模式与青春发动时相提前[J]. 中国学校卫生, 2008, 29(3): 193-195, 199. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-9817.2008.03.001 Tao FB. Early onset of puberty and adolescent health series (1): early growth patterns and early onset of puberty[J]. Chin J Sch Health, 2008, 29(3): 193-195, 199. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-9817.2008.03.001 |

| [8] |

Leone T, Brown LJ. Timing and determinants of age at menarche in low-income and middle-income countries[J]. BMJ Global Health, 2020, 5(12): e003689. DOI:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003689 |

| [9] |

Song Y, Ma J, Wang HJ, et al. Age at spermarche: 15-year trend and its association with body mass index in Chinese school-aged boys[J]. Pediatr Obes, 2016, 11(5): 369-374. DOI:10.1111/ijpo.12073 |

| [10] |

Lei YT, Luo DM, Yan XJ, et al. The mean age of menarche among Chinese schoolgirls declined by 6 months from 2005 to 2014[J]. Acta Paediatr, 2021, 110(2): 549-555. DOI:10.1111/apa.15441 |

| [11] |

马宁, 师嫡, 蔡珊, 等. 2010-2019年中国9~18岁汉族女生月经初潮年龄的变化趋势[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2023, 57(4): 486-491. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20220805-00872 Ma N, Shi D, Cai S, et al. Trend of age of menarche among Chinese Han girls aged 9 to 18 years from 2010 to 2019[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2023, 57(4): 486-491. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20220805-00872 |

| [12] |

师嫡, 马宁, 刘云飞, 等. 2010-2019年中国11~18岁汉族男生首次遗精年龄长期趋势及其与营养状况关联的研究[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2023, 57(4): 492-498. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20220905-00870 Shi D, Ma N, Liu YF, et al. Long-term trend of the age of spermarche and its association with nutritional status among Chinese Han boys aged 11-18 years from 2010 to 2019[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2023, 57(4): 492-498. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20220905-00870 |

| [13] |

Fan HY, Lee YL, Hsieh RH, et al. Body mass index growth trajectories, early pubertal maturation, and short stature[J]. Pediatr Res, 2020, 88(1): 117-124. DOI:10.1038/s41390-019-0690-3 |

| [14] |

Gong TT, Wu QJ, Vogtmann E, et al. Age at menarche and risk of ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies[J]. Int J Cancer, 2013, 132(12): 2894-2900. DOI:10.1002/ijc.27952 |

| [15] |

Ohlsson C, Bygdell M, Nethander M, et al. Early puberty and risk for type 2 diabetes in men[J]. Diabetologia, 2020, 63(6): 1141-1150. DOI:10.1007/s00125-020-05121-8 |

| [16] |

Prentice P, Viner RM. Pubertal timing and adult obesity and cardiometabolic risk in women and men: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Int J Obes, 2013, 37(8): 1036-1043. DOI:10.1038/ijo.2012.177 |

| [17] |

Downing J, Bellis MA. Early pubertal onset and its relationship with sexual risk taking, substance use and anti-social behaviour: a preliminary cross-sectional study[J]. BMC Public Health, 2009, 9(1): 446. DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-9-446 |

| [18] |

韩晓洁, 郁琦. 女性青春期启动及相关影响因素[J]. 实用妇产科杂志, 2022, 38(10): 721-724. Han XJ, Yu Q. Female puberty initiation and related influencing factors[J]. J Pract Obstet Gynecol, 2022, 38(10): 721-724. |

| [19] |

Diao H, Wang H, Yang LJ, et al. The association between sleep duration, bedtimes, and early pubertal timing among Chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional study[J]. Environ Health Prev Med, 2020, 25(1): 21. DOI:10.1186/s12199-020-00861-w |

| [20] |

陈子玥, 蔡珊, 马宁, 等. 中国9~18岁儿童青少年心理困扰流行现状[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(10): 1537-1544. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20230517-00304 Chen ZY, Cai S, Ma N, et al. Prevalence of psychological distress among Chinese children and adolescents aged 9-18 years[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2023, 44(10): 1537-1544. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20230517-00304 |

| [21] |

Gray NS, O'Connor C, Knowles J, et al. The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental well-being and psychological distress: impact upon a single country[J]. Front Psychiatry, 2020, 11: 594115. DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.594115 |

| [22] |

中国学生体质与健康研究组. 2014年中国学生体质与健康调研报告[M]. 北京: 高等教育出版社, 2016. China Student Physical Fitness and Health Research Group. Reports on the physical fitness and health research of Chinese school students[M]. Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2016. |

| [23] |

中华人民共和国国家统计局. 统计制度及分类标准(17)[EB/OL]. (2022-02-21)[2023-02-17]. http://www.stats.gov.cn/zs/tjws/cjwtjd/202302/t20230217_1912798.html.

|

| [24] |

McKay MT, Andretta JR. Evidence for the psychometric validity, internal consistency and measurement Invariance of Warwick Edinburgh mental well-being scale scores in Scottish and Irish adolescents[J]. Psychiat Res, 2017, 255: 382-386. DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.071 |

| [25] |

World Health Organization. Global health estimates for 2019[EB/OL]. [2023-05-13]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2020.https://www.who.int/data/global-health-estimates.

|

| [26] |

Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Prevalence and associated factors of psychological distress among a national sample of in-school adolescents in Morocco[J]. BMC Psychiatry, 2020, 20(1): 475. DOI:10.1186/s12888-020-02888-3 |

| [27] |

Davey CG, Yücel M, Allen NB. The emergence of depression in adolescence: development of the prefrontal cortex and the representation of reward[J]. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2008, 32(1): 1-19. DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.016 |

| [28] |

Bluth K, Campo RA, Futch WS, et al. Age and gender differences in the associations of self-compassion and emotional well-being in a large adolescent sample[J]. J Youth Adolescence, 2017, 46(4): 840-853. DOI:10.1007/s10964-016-0567-2 |

| [29] |

Sontag LM, Graber JA, Clemans KH. The role of peer stress and pubertal timing on symptoms of psychopathology during early adolescence[J]. J Youth Adolescence, 2011, 40(10): 1371-1382. DOI:10.1007/s10964-010-9620-8 |

| [30] |

Joinson C, Heron J, Lewis G, et al. Timing of menarche and depressive symptoms in adolescent girls from a UK cohort[J]. Br J Psychiatry, 2011, 198(1): 17-23. DOI:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080861 |

| [31] |

Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes[J]. J Abnorm Psychol, 1991, 100(4): 569-582. DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569 |

| [32] |

Reardon LE, Leen-Feldner EW, Hayward C. A critical review of the empirical literature on the relation between anxiety and puberty[J]. Clin Psychol Rev, 2009, 29(1): 1-23. DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.005 |

| [33] |

Ma HM, Du ML, Luo XP, et al. Onset of breast and pubic hair development and menses in urban Chinese girls[J]. Pediatrics, 2009, 124(2): e269-277. DOI:10.1542/peds.2008-2638 |

| [34] |

Abreu AP, Kaiser UB. Pubertal development and regulation[J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2016, 4(3): 254-264. DOI:10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00418-0 |

| [35] |

Sørensen K, Mouritsen A, Aksglaede L, et al. Recent secular trends in pubertal timing: implications for evaluation and diagnosis of precocious puberty[J]. Horm Res Paediatr, 2012, 77(3): 137-145. DOI:10.1159/000336325 |

| [36] |

Perry JRB, Murray A, Day FR, et al. Molecular insights into the aetiology of female reproductive ageing[J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 2015, 11(12): 725-734. DOI:10.1038/nrendo.2015.167 |

| [37] |

Boynton-Jarrett R, Harville EW. A prospective study of childhood social hardships and age at menarche[J]. Ann Epidemiol, 2012, 22(10): 731-737. DOI:10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.08.005 |

| [38] |

Le-Ha C, Herbison CE, Beilin LJ, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity under resting conditions and cardiovascular risk factors in adolescents[J]. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2016, 66: 118-124. DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.01.002 |

| [39] |

Semiz S, Kurt F, Kurt DT, et al. Factors affecting onset of puberty in Denizli province in Turkey[J]. Turk J Pediatr, 2009, 51(1): 49-55. |

| [40] |

Jean RT, Wilkinson AV, Spitz MR, et al. Psychosocial risk and correlates of early menarche in Mexican-American girls[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2011, 173(10): 1203-1210. DOI:10.1093/aje/kwq498 |

| [41] |

张敏婕, 朱丁, 徐勇, 等. 女生月经初潮早发与负性生活事件的关系[J]. 中国学校卫生, 2011, 32(9): 1027-1028. DOI:34-1092/R.20110920.1229.009. Zhang MJ, Zhu D, Xu Y, et al. Association of negative life events with early menarche[J]. Chin J School Health, 2011, 32(9): 1027-1028. DOI:34-1092/R.20110920.1229.009. |

| [42] |

陶芳标, 孙莹, 郝加虎. 青春发动时相提前与青少年性及生殖健康服务[J]. 国际生殖健康/计划生育杂志, 2010, 29(6): 406-409. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-1889.2010.06.010 Tao FB, Sun Y, Hao JH. Early puberty and adolescent sexual and reproductive health services[J]. J Int Reprod Health/Fam Plan, 2010, 29(6): 406-409. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-1889.2010.06.010 |

| [43] |

Brown J, Cohen P, Chen HN, et al. Sexual trajectories of abused and neglected youths[J]. J Dev Behav Pediatr, 2004, 25(2): 77-82. DOI:10.1097/00004703-200404000-00001 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44